1. Introduction

This research is part of an ongoing project titled Moving Senseware. Slow sensors, widely employed in areas such as industrial automation, environmental monitoring, and smart agriculture, encounter notable challenges in real-time data processing. These challenges arise from limitations such as restricted bandwidth, delayed response times, and low sampling rates. Consequently, issues like data latency, sparsity, and noise can significantly undermine system performance and decision-making capabilities. The integration of adaptive learning techniques, including incremental and real-time learning algorithms, offers a promising solution to enhance the efficiency and reliability of slow sensor systems. Furthermore, the development of context-aware systems amplifies the effectiveness of adaptive learning in addressing these challenges. Recent advancements in sensor technology, driven by breakthroughs in machine learning and computational power, have enabled the creation of intelligent sensor designs that optimize data acquisition while reducing the associated data burden. Adaptive algorithms, such as Kalman filtering and reinforcement learning, allow for dynamic adjustments to system parameters. These capabilities effectively mitigate sensor lag, improve data accuracy, and enhance the performance of soft sensing applications and sensor networks. With the support of artificial intelligence, slow sensors are increasingly demonstrating their potential to excel in various domains, including well-being and beyond, paving the way for more innovative and responsive sensing solutions.

1.1. Adaptive Learning in Slow Sensor

Due to bandwidth constraints, response time delays, or low sampling rates during data capture, slow sensors present particular difficulties in real-time data processing and decision-making. Integrating adaptive learning technology can significantly increase the slow sensor system’s efficiency and dependability and resolve the issues of data latency, sparsity, and noise. The application of adaptive learning in slow sensor technology, especially in the use of soft sensor, is of great significance. The Soft sensor is a kind of virtual sensor that estimates process variables by combining existing measurement data and models, with the core advantage of adapting to new data patterns. To compensate for the limitations of physical sensors in real-time data acquisition, soft sensors often integrate machine learning algorithms. These algorithms enable the system to learn from historical data and adjust forecasts as new data arrives. For example, adaptive deep learning models have been applied to the prediction of PM2.5 concentration in subways, maintaining the accuracy and timidity of the prediction even when the data are discontinuous [

1]. In addition, the development of context awareness system further enhances the application value of adaptive learning in slow sensors. With adaptive learning models and ubiquitous devices, these systems are able to analyze environmental data and optimize resource management, especially in agriculture, by adapting agricultural practices to improve crop yields and sustainability. This integrated adaptive learning system is able to process slow sensor data more efficiently, providing valuable operational insights that significantly improve operational efficiency [

2]. Adaptive learning algorithms, such as incremental learning and real-time learning, further enhance the capabilities of slow sensors, particularly in the face of concept drift. By gradually updating the model, these algorithms ensure that the system maintains accurate predictions even as the data distribution evolves. This capability is crucial for slow sensor monitoring, as these sensors often experience infrequent or discontinuous data updates [

3]. Additionally, related studies have explored the collection of physical activity data through smart sensors, analyzing this data in conjunction with machine learning methods to identify early signs of physical frailty. This approach can facilitate personalized health interventions and improve predictive capabilities regarding individual health outcomes [

4].

1.2. Intelligent Adaptive in Slow Sensor

Recent advancements in sensor technology have been driven by machine learning and computational resources, enabling intelligent sensor design that optimizes data acquisition and reduces data burden [

5]. This approach has led to the development of adaptive learning models for time series sensor signal classification on edge devices, balancing performance with computational constraints [

6]. Self-learning embedded systems for object identification in intelligent infrastructure sensors have also emerged, utilizing dynamic decision trees and cooperative strategies to adapt to changing environments [

7]. In the context of smart cool chains, new wireless and intelligent sensors have been developed to monitor transportation environments, ensure product quality, and handle large-scale data processing and transmission [

8]. These innovations are paving the way for more efficient, autonomous, and widely distributed sensing networks across various fields, including biomedical diagnostics, environmental sensing, and global health.

Researchers have increasingly explored innovative approaches to enhancing well-being and optimizing design efficiency across various contexts. For instance, a slow happiness gardening system developed for radiation therapy patients employs sensors to track behavioral data during treatment and gardening therapy, leading to improved well-being [

9]. In the domain of collaborative manufacturing, the SENS+ system integrates Internet of Things (IoT) devices to monitor energy consumption and optimize manufacturing processes [

10]. Additionally, SENS, a behavior-based intelligent energy system for co-manufacturing spaces, utilizes sensor networks and IoT technologies to provide dynamic feedback on energy consumption patterns. These studies highlight the potential of integrated sensor technologies, user behavior analysis, and interaction design in creating more efficient, responsive, and user-centered environments across healthcare, manufacturing, and energy management sectors [

11].

The application of smart technology has also been explored in the context of improving the well-being of elderly individuals, particularly those living alone. For example, the HIGAME+ system connects elderly people with their children through an IoT-enabled pot, facilitating remote interaction and emotional support [

12]. Similarly, HiGame fosters intergenerational communication by incorporating horticultural activities into both physical and virtual games [

13]. Another study introduced Blindside, a board puzzle game designed to promote family interaction by emphasizing achievement, collaboration, and collecting as core elements of the gameplay [

14]. These studies suggest that combining gardening, gaming, and IoT technologies offers promising strategies to alleviate loneliness and improve the mental health of older adults, by fostering connection with family members and engaging them in meaningful, enjoyable activities.

1.3. Related Research on Slow Sensor

Slow sensors are widely used in many applications such as industrial automation, environmental monitoring and smart agriculture, but their slow response times can affect the performance of real-time data processing systems. To address this challenge, researchers have proposed a variety of adaptive learning and intelligence methods to improve the performance and integration of slow sensor systems. In terms of adaptive learning, by enhancing data processing technology and using machine learning models, especially time series analysis, to predict and compensate sensor delays, the response speed of the system can be significantly improved; Self-powered sensors optimize energy use, enhance network scalability, and potentially reduce response times [

15,

16]. Sensor fusion technology achieves a balance between accuracy and timeliness by integrating sensor data with different response times, and smart sensor design improves system performance by reducing the burden on the central processing unit through on-board data processing capabilities built into the sensor [

17].

At the same time, adaptive algorithms such as Kalman filtering and reinforcement learning can dynamically adjust system parameters to effectively deal with sensor lag [

18]. In terms of intelligent solutions, neuromorphic computing can improve system processing capacity even in the face of slow sensor inputs by simulating the neural structure of the human brain and utilizing parallel processing and low-power computing [

19]. Edge computing deploys computing resources close to sensor nodes, reducing latency and improving response speed [

20]. By integrating these technologies and methods, the system can effectively overcome the limitations of slow sensors and enable more efficient and responsive applications in areas such as industrial automation, environmental monitoring and intelligent infrastructure.

Recent research on adaptive learning for slow sensors focuses on improving soft sensing applications and optimizing sensor networks. A subspace ensemble regression model has been developed for soft sensing, utilizing slow feature directions and adaptive regression techniques [

21]. For wireless sensor networks, an adaptive learning automata algorithm has been proposed to efficiently schedule sensor nodes, balancing target coverage and power consumption [

22]. To address computational constraints in edge devices, an Instant Adaptive Learning approach has been introduced, employing linear adaptive filtering and derivative spectrum for fast model construction [

6]. Additionally, a transductive moving window learner has been designed for soft sensor applications, combining moving window and Just-In-Time-Learning methods to enhance prediction accuracy and adaptability to concept drifts in industrial processes [

23]. These advancements aim to improve the performance and efficiency of adaptive learning in various sensor-based applications.

2. Literature Review

Slow sensors often face limitations in processing power, storage, and energy, affecting their adaptability in complex environments. To enhance their performance, the integration of adaptive learning and intelligence capability is crucial. However, challenges remain, including the resource limitations that hinder adaptive learning, the need to balance model performance with efficiency, and addressing privacy and security concerns associated with handling user data. This study reviewed current difficulties of slow sensors, and the related TinyML applications. The main research methods used in this study are machine learning algorithm application, prototype experiment and evaluation.

2.1. Challenges Faced by Slow Sensors

The motivation behind exploring TinyML arises from the necessity to incorporate intelligent computation into slow sensors, which are often resource-constrained devices like microcontrollers and edge devices. TinyML is particularly suitable for running machine learning models in such environments, allowing these devices to leverage adaptive learning and function effectively in complex situations while maintaining low computational power, limited storage capacity, and energy efficiency. However, implementing TinyML presents several significant challenges. The foremost issue is the limitation of resources, which serves as the primary bottleneck for TinyML applications. Adaptive learning typically relies on computation-intensive algorithms, placing immense pressure on devices that have restricted storage and processing capabilities [

24]. Model optimization further complicates matters, as developers must balance performance requirements with efficiency. While models need to maintain real-time learning capabilities, overly large models can impede processing speed and escalate energy consumption [

25]. In addition, the adaptive learning process necessitates handling substantial amounts of user data, which raises crucial privacy and security concerns. Ensuring data integrity and preventing unauthorized access becomes an ethical priority that must be addressed [

26]. Real-time performance is also essential, as devices require the capacity to process new data with minimal latency, thus necessitating higher computational power [

27]. Finally, the scalability of adaptive learning models and the complexity of deployment across various hardware configurations present significant challenges for developers [

28].

2.2. TinyML Solutions for Slow Sensors

In light of the obstacles associated with TinyML, researchers have undertaken various initiatives to address these challenges. A critical focus is on developing efficient algorithms that foster TinyML advancement. Techniques such as model pruning, quantization, and knowledge distillation are particularly effective in reducing model size while preserving performance, making them well-suited for TinyML applications [

29]. These methods significantly decrease memory and computational demands, enabling models to fit better within the constraints of resource-limited devices. Moreover, implementing local learning on the device has emerged as a pivotal strategy to mitigate privacy concerns and reduce latency. For instance, optimization-based in-device update methods allow models to adjust in real time without reliance on cloud computing, which enhances privacy and decreases response times. Techniques such as federated learning are increasingly utilized to train models on local devices, sharing only parameters instead of raw data, thereby significantly lowering the risks of data leakage [

30]. The introduction of edge computing has also bolstered the real-time processing capabilities of adaptive learning, permitting tasks to be completed closer to data sources and minimizing network-related delays [

31]. Additionally, customized hardware development—such as designing accelerator chips optimized for specific tasks—has proven to be a promising direction that can enhance device performance within limited resource constraints, thus enabling more complex algorithms to operate effectively [

32].

2.3. Experimental Approaches to Validate TinyML Applications

When deploying TinyML on slow sensors, designing thorough evaluation methodologies is vital to determine the effectiveness of the integration. Simulation experiments can be set up to test the performance of TinyML-enabled slow sensors by creating controlled environments that mimic real-world applications, such as health monitoring or environmental sensing. This can involve using virtual tools to generate synthetic data that cover a wide range of scenarios. In field testing, evaluating user feedback during actual deployments is essential. Collecting data under real conditions helps assess the typical performance of the sensors and the TinyML algorithms in place. Monitoring their responsiveness, user satisfaction, and adaptability also provides critical insights that inform future improvements. Performance evaluation metrics such as precision, recall, energy consumption, and latency should be employed to provide a comprehensive overview of how well these sensors perform under different operational conditions and to optimize their configurations accordingly. By thoroughly investigating how TinyML can be effectively implemented in slow sensors, it is possible to unlock new capabilities for these devices, ultimately leading to enhanced functionality and wider applications in the rapidly evolving field of smart technology.

3. Experiment Design

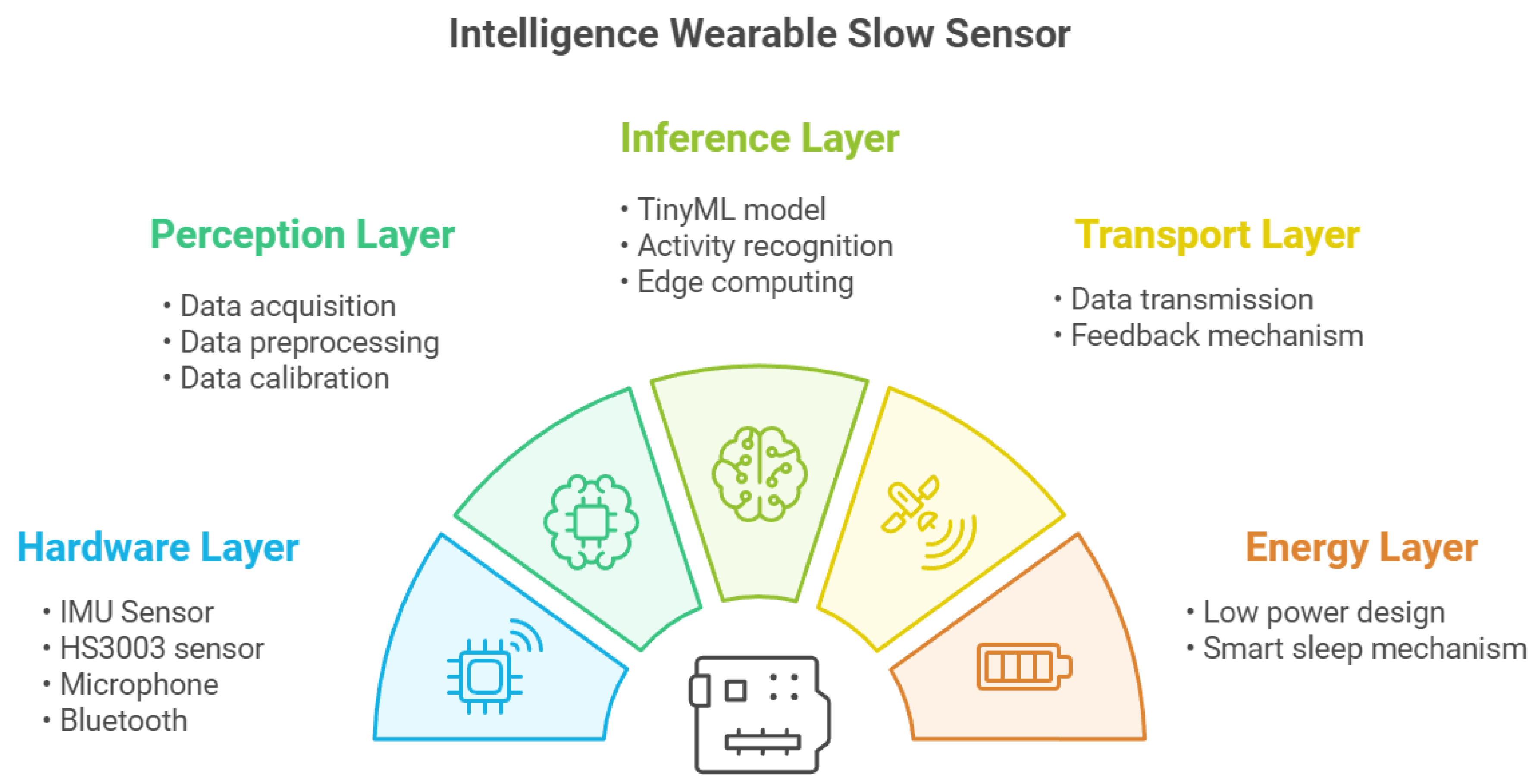

The core purpose of this experiment is to use deep learning techniques to achieve real-time and efficient behavior perception on resource-constrained devices. In order to achieve this goal, this study designed a hybrid slow sensor containing multiple layers, which can be mainly divided into hardware layer and senseware layer, where the hardware layer is mainly the physical part of the system and is responsible for the communication between the real space and the digital space. The senseware layer is a more abstract layer that uses machine learning and neural network techniques to compute and analyze the sensed data as

Figure 1.

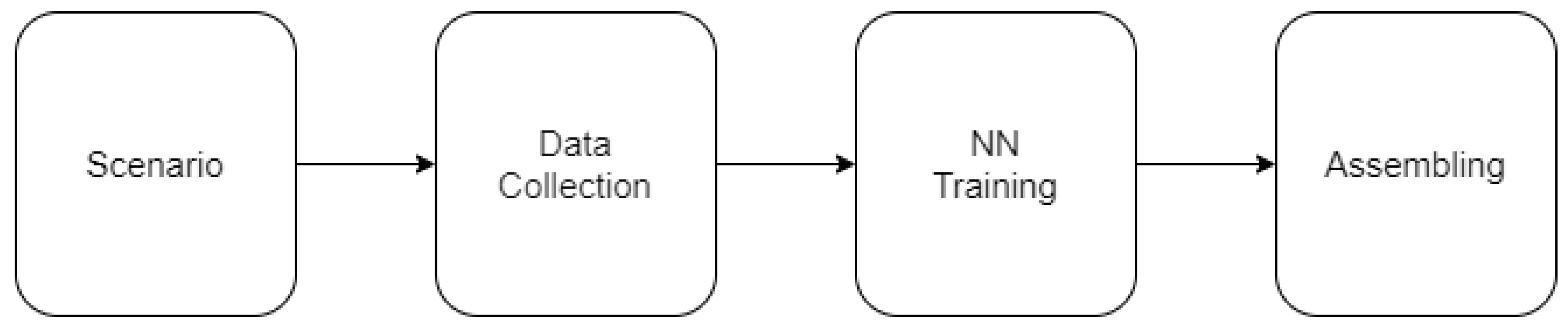

3.1. Experiment Flow

The experimental process of this study consists of four main stages, which are: context setting and hardware configuration, data collection and preprocessing, model training and fine-tuning, and model testing and feedback. The most difficult part lies in the training of the machine learning model, the most laborious part lies in the collection and preprocessing of the experimental data, and the most important part is the test of the trained model. The setting of the experimental situation and the hardware selection of the slow sensor are the cornerstones for the smooth development of the subsequent experiments. It may be necessary to go back to the previous step depending on the requirements of the actual experiment as

Figure 2.

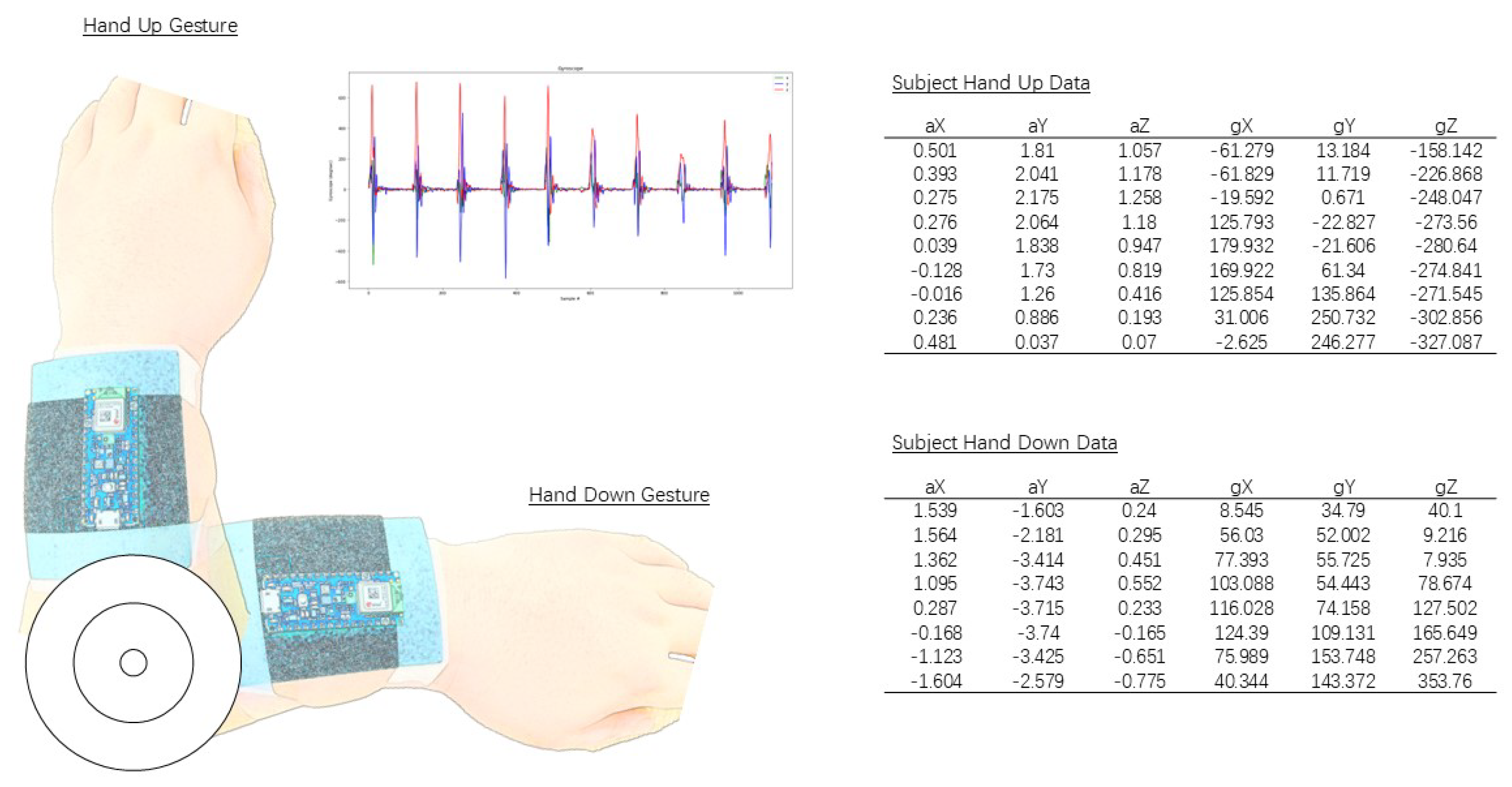

Firstly, the application scenario of this smart slow sensor needs to be clarified. In this study, the main focus is on the value of slow sensor to people, so more attention will be paid to dynamic information such as acceleration and angular velocity, which are the focus of traditional motion recognition research. Next, it is necessary to determine the target of intelligent cloud scattering function. In this study, the neural network is used to achieve similar pattern recognition function, so it is necessary to select the appropriate hardware platform to ensure that it has the required data collection ability in the target scene. At the same time, to achieve long operation time, special attention should be paid to the sensor power consumption to ensure that its working range conforms to the low power requirement of TinyML, which is met by the test hardware selected in this study.

Secondly, after the hardware configuration is completed, the next step is to collect raw data through sensors. These data usually contain noise and incomplete information, so it is necessary to perform preprocessing, including signal denoising and data normalization, to improve data quality. Once the data was cleaned, the data was split into training, validation, and test sets, following standard practice in machine learning. This split allows for more efficient evaluation of model performance in subsequent model development and avoids overfitting issues. In this study, the subjects were asked to perform the same action repeatedly to capture the original data, and more than one different action was added to the original data of an action after it was successfully captured.

Third, we need to select a machine learning model for the raw data that we collected in the previous step using slow sensor, which contains the actions of the subject. In this study, TensorFlow Lite and Keras were used to train the neural network. Due to the limited resources of edge devices, transfer learning techniques can be used to quickly adapt the pre-trained model to specific tasks by fine-tuning it during model training. In addition, model quantization and pruning can effectively reduce the model size and computational complexity, so that the model can run in a low-power manner. In this study, notebook and colab were used to train the same set of original data, and it was found that online tools can better complete this work, especially in the construction of software environment, and the workload of training platform based on notebook to build runtime environment is much greater than that of online platform.

Finally, the optimized model needs to be deployed to wearable devices for real-time data processing and computation. tinyml technology is used in this study, so before deploying the model, it needs to be converted into a small binary file, and then it can be successfully deployed to the Arduino development board. Through the test feedback, the shortcomings of the model in practical applications can be found, such as inaccurate prediction or too slow response in some scenarios. Based on the feedback, the developer can adjust and retrain the model to gradually improve the overall performance of the system.

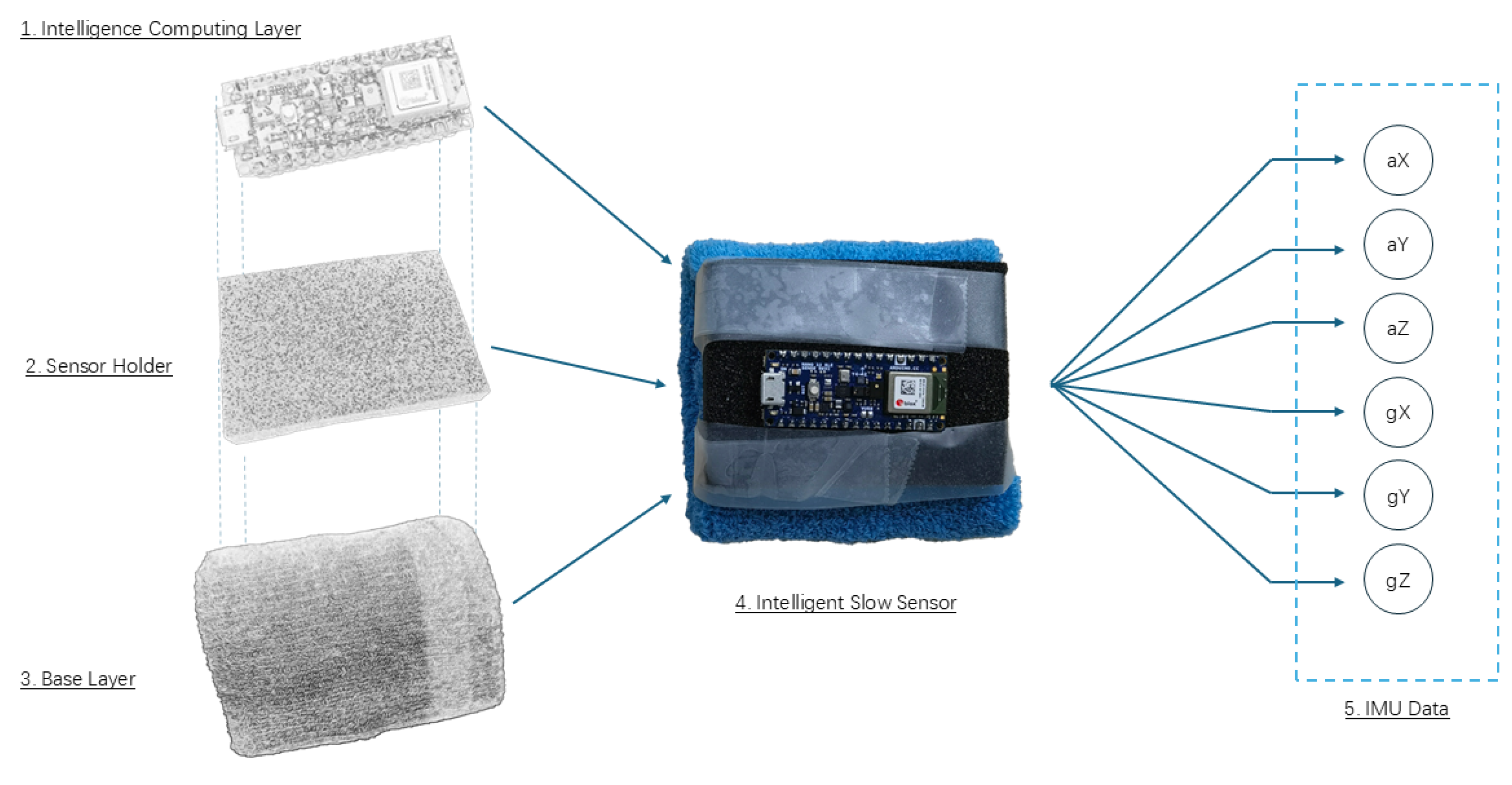

3.2. Hardware Design and Assembling

The system design based on Arduino Nano 33 BLE Sense includes hardware layer, sensing layer, reasoning layer, transport layer and energy consumption layer, and all layers work together to achieve a multifunctional and low-power wearable smart device. The hardware layer is the physical part of the system, and its core component Arduino Nano 33 BLE Sense integrates accelerometer, gyroscope, temperature and humidity sensor, microphone, light sensor, gas sensor and other sensors, which can collect motion data, environmental data and sound signals in real time. These sensors are used to capture the movement and posture of the wearer, monitor environmental conditions and collect sound signals, which significantly enhance the data acquisition ability of the system. In addition, the device supports Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) communication, which can be wirely-connected with devices such as mobile phones, cloud platforms or PCS to achieve convenient data transmission as

Figure 3.

The sensing layer is the core connection between the slow sensor and the outside world, and it is responsible for the collection and preliminary processing of sensing data. Arduino Nano 33 BLE Sense acquires multidimensional data in real time through its sensors and completes preprocessing on the hardware side, such as denoising, filtering, or data normalization, to ensure higher quality of data incoming to the neural network, thus providing clear input for subsequent reasoning. The reasoning layer is the intelligent core module of the system, which realizes a variety of task functions through the TinyML model deployed on the device. For example, activity recognition based on accelerometer and gyroscope data to determine the type of movement the wearer is doing (e.g., raising hands, putting down, or standing still). The introduction of edge computing enables these neural network models to perform inference directly on the device side, significantly reducing data transmission requirements, reducing latency, and improving response speed.

In the transport layer, through the Arduino Nano built-in BLE module can communicate wirelessly with another Arduino Nano, but in this way, its low-cost advantage will be destroyed. After repeated testing, the researchers decided to generate intelligent computing capabilities as the primary goal in the prototype stage. Under the premise of not harming the primary goal, it is changed to use a USB cable to connect the smart device with the built-in GPU notebook, which can not only transmit the sensing data to the host computer in real time, and draw a graph, but also provide the possibility for subsequent research by the powerful computing power of GPU.

The energy consumption layer benefits from the excellent energy-saving design of Arduino itself. Due to the support of low power mode and intelligent sleep mechanism, the Arduino development board can let the sensor go to sleep when there is no significant change, thereby reducing energy consumption. This design not only extends the battery life of the device, but also ensures the efficiency of the wearable device in daily use and the improvement of the user experience.

3.3. Deep Neural Network Design

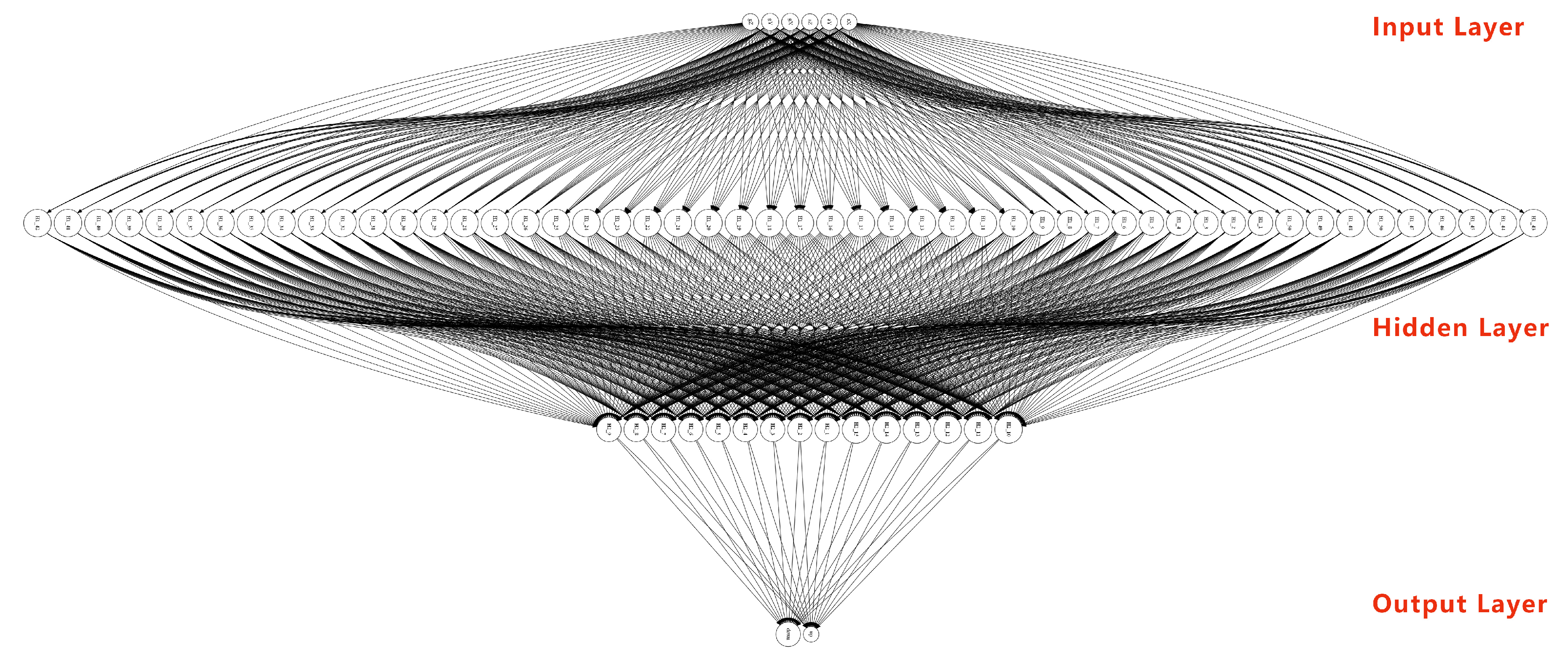

The trained neural network comprises three primary layers: the input layer, hidden layer, and output layer (

Figure 4). The input layer is responsible for receiving sensing data from the slow sensor, which, in this study, consists of IMU data. This data includes six values: three spatial coordinates (x, y, z) and three triaxial acceleration values (ax, ay, az). For the hidden layer, this study implements a two-stage filtering mechanism. Initially, 50 neurons are utilized for the preliminary screening of sensor data, followed by 15 neurons for secondary filtering. This approach offers the advantage of rapidly detecting user actions; however, it is less effective in identifying complex user behaviors. The design strategy not only reduces the initial training cost but also incorporates forward and reverse limb and hand movements to train the neural network. The inherent spatial coherence in the data further lowers training costs while enhancing the training success rate.

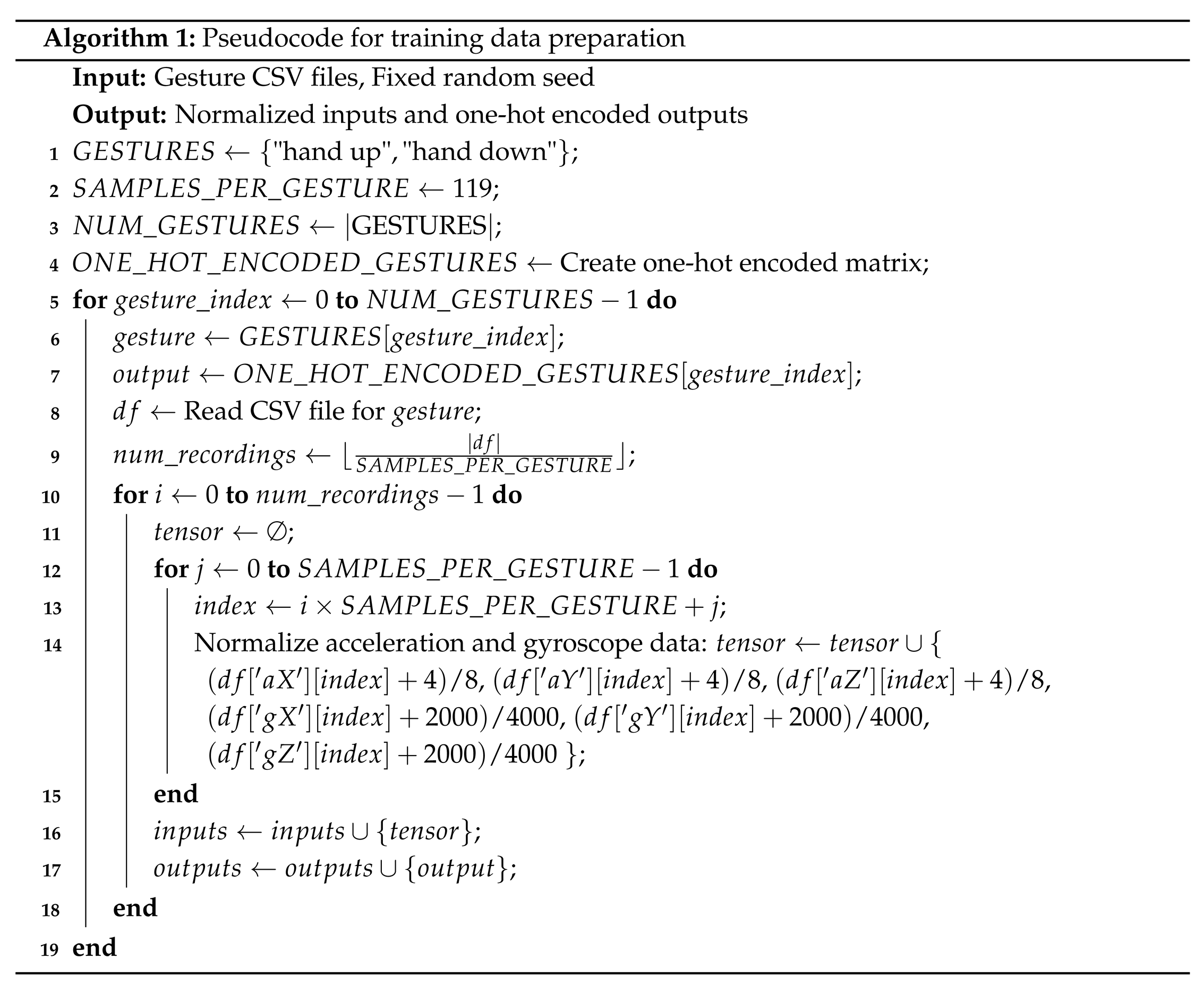

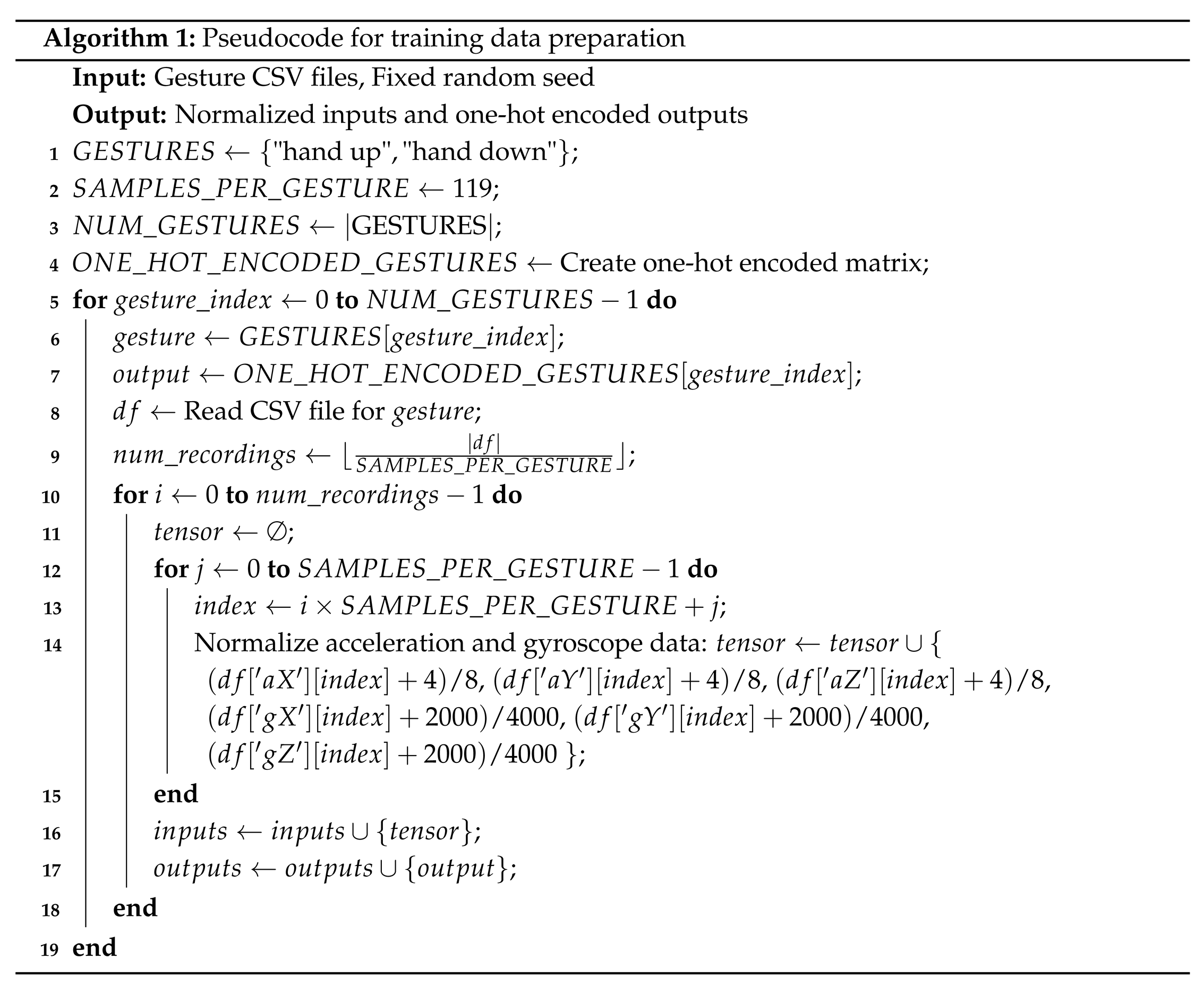

4. TinyML Algorithm Application

The researchers utilized TensorFlowLite to train the Deep Neural Network (DNN) for implementing TinyML on Arduino. The Python training process involves several critical steps, including data preparation, model design, training, and evaluation. Algorithm 1 outlines the pseudocode for data preparation, providing a detailed account of the experimental procedure. The training data was normalized using mathematical techniques and subsequently divided into three distinct sets: the training set, the test set, and the validation set. Following the design of the neural network model, the team constructed the DNN model, which ultimately converged smoothly after 600 training iterations. By analyzing the model’s loss performance and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) during the final validation phase, the researchers confirmed the effectiveness and usability of the model. This structured approach ensured that the model was not only robust but also adaptable for practical applications. Through meticulous training and validation, the researchers achieved a successful implementation of TinyML on Arduino using TensorFlowLite.

4.1. Training Data Preparation

We utilize an Arduino Nano board to sampling the IMU data from subjects left hand, with a sampling rate set at 119Hz. In this context, let

t denote time in seconds and

n represent the sample index.

The IMU acceleration data at time

t is denoted as

a(t), allowing us to express the sampled data accordingly.

To incorporate the normalization requirement, the IMU raw data is accurate to three decimal places, we need to explicitly include the rounding in the function formula. This can be done using a rounding function that ensures each sampled data point is rounded to three decimal places.

After extensive testing during the pilot phase, we established a sampling threshold of 2.5 for the IMU data. Only the data points exceeding this threshold, which represents the acceleration due to gravity, will be recorded by the Arduino. This decision ensures that we capture significant movements while filtering out noise.

Dataset Normalizing:

1. Normalizing acceleration data:

2. Normalizing gyroscope data:

4.2. DNN Training

The neural network training tool employed in this study is the Sequential class, a fundamental component in TensorFlow designed for building deep learning models. This class facilitates the construction of neural networks in a linear, stacked manner, enabling users to add layers sequentially, which simplifies the design and training process for deep learning applications. With the Sequential class, multiple layers of a neural network can be added in a systematic way, where the output of each layer serves as the input for the subsequent layer. Layers can be incorporated individually using the add method. Researchers can select various configurations such as the optimizer, loss function, and performance metrics, and subsequently utilize the compile method to set up the model. Once all essential parameters are configured, the neural network model is trained through the fit method. This streamlined approach makes the Sequential class particularly advantageous for users aiming to efficiently build and train neural networks.

4.2.1. DNN Architecture

The neural network model consists of three distinct layers, each fulfilling a specific role in the computation process. The first layer, known as the input layer, contains six nodes and is responsible for receiving the IMU data. Following the input layer are two dense, fully connected hidden layers, which are tasked with processing the data and extracting meaningful patterns. The first hidden layer contains 50 neurons, while the second hidden layer comprises 15 neurons. Both of these layers utilize the ReLU activation function to introduce non-linearity, significantly enhancing the model’s capacity to learn complex relationships within the data. Lastly, the output layer consists of two neurons and employs the softmax activation function to generate probabilistic predictions for two classes based on the processed input. This structure ensures that the model is well-equipped to perform classification tasks effectively. The mathematical representation is provided below.

Let:

x be the input vector.

w be the weight matrices for the first, second, and third layers.

b be the bias vectors for the first, second, and third layers.

ReLU activation function is

softmax activation function is

4.2.2. Loss Function setup

The loss function used is the mean squared error (MSE):

where:

is the true output for the i-th training example;

is the predicted output for the i-th training example;

N is the number of training examples.

4.2.3. Optimization Process

We use the RMSprop optimizer to minimize the loss function, RMSprop adjusts the learning rate for each parameter by dividing by a running average of the magnitudes of recent gradients.

4.3. Model Training and Validation

The training process involves iterating over the training data for a specified number of epochs, which is 600 in this case. During this process, the model parameters are updated through backpropagation and gradient descent. Throughout training, a validation set is employed to measure the model’s performance by calculating the mean absolute error (MAE) on the validation data.

In this instance, represents the number of validation examples. Upon completion of the training, the model’s performance is assessed on the test set using the parameters learned during training. The MAE is computed to evaluate the model’s generalization capability, determining how well it performs on unseen data.

5. Result

The experimental results indicate that the integration of artificial intelligence technology into slow sensors has led to significant enhancements in multiple areas. Firstly, hardware upgrades have made traditional slow sensors better suited for complex wearable environments, improving both device durability and the stability of data collection. Secondly, the addition of intelligent modules has considerably expanded the computational capacity of slow sensors, enabling them to process a wider array of data efficiently and allowing for partial real-time analysis and feedback. Finally, through continuous optimization of the neural network model, the prediction accuracy and responsiveness of slow sensors have improved markedly, providing robust technical support for their application in dynamic environments.

5.1. Slow Sensor Hardware Update

In this study, the researchers undertook various improvements to the hardware of the slow sensor to enhance its applicability and performance. Firstly, to minimize the size of the sensor, we selected the Nano board, the smallest specification in the Arduino family. This choice not only makes the sensor lighter and more compact but also allows for greater flexibility in its integration into wearable devices. Secondly, the researchers designed a substrate specifically tailored for wrist wear and conducted an in-depth exploration of its assembly. By optimizing both the structural design and material selection, we ensured that the sensor could be securely worn on the wrist, preventing it from falling off due to movement or friction during low to medium intensity activities. This design significantly enhances the sensor’s stability and reliability in practical applications as

Figure 5. Additionally, to lower the energy consumption of the device, the researchers developed low-power operating modes for the sensors. This mode effectively reduces energy consumption by optimizing experiment design, thereby extending the sensor’s operational lifespan. Overall, these hardware upgrades not only enhance the physical performance and user experience of the sensor but also establish a solid foundation for its practical application in the field of wearable devices.

5.2. Intelligent Module Setup

The design and implementation of intelligent modules represent a primary objective of this research. By integrating these modules into the slow sensor, the researchers aim to endow it with three essential capabilities: computability, adaptability, and iterability. Firstly, "computability" enhances traditional data processing modes by incorporating autonomous computing capabilities into the sensors. By collecting a small amount of raw data from two actions performed by the subject using the slow sensor, the training of the neural network can be conducted, as illustrated in

Table 1.

Similar to edge computing, this approach allows sensors to locally process data or contextual information without human intervention, thereby facilitating real-time analysis and feedback. This capability not only reduces reliance on external computing resources but also improves the system’s response efficiency. Secondly, "adaptability" focuses on enabling sensors to utilize adaptive learning, significantly enhancing their ability to adjust to new contexts. With this feature, the sensors can serve a broader range of users rather than being confined to a specific individual, thereby improving their generalization ability to meet diverse needs without requiring hardware modifications or model retraining as different subject gestures recognizing results shown in

Table 2.

Finally, "iterability" is a characteristic inherent to the computational power of artificial intelligence. As research advances, optimization and iteration of neural networks become feasible, allowing sensors to continuously enhance their performance, including improved prediction accuracy, reduced computation time, and the introduction of new features. This comprehensive design of capabilities ensures that the slow sensor not only addresses current requirements but also has the potential for ongoing evolution and optimization across various applications, thereby opening up new opportunities in the field of smart wearable devices.

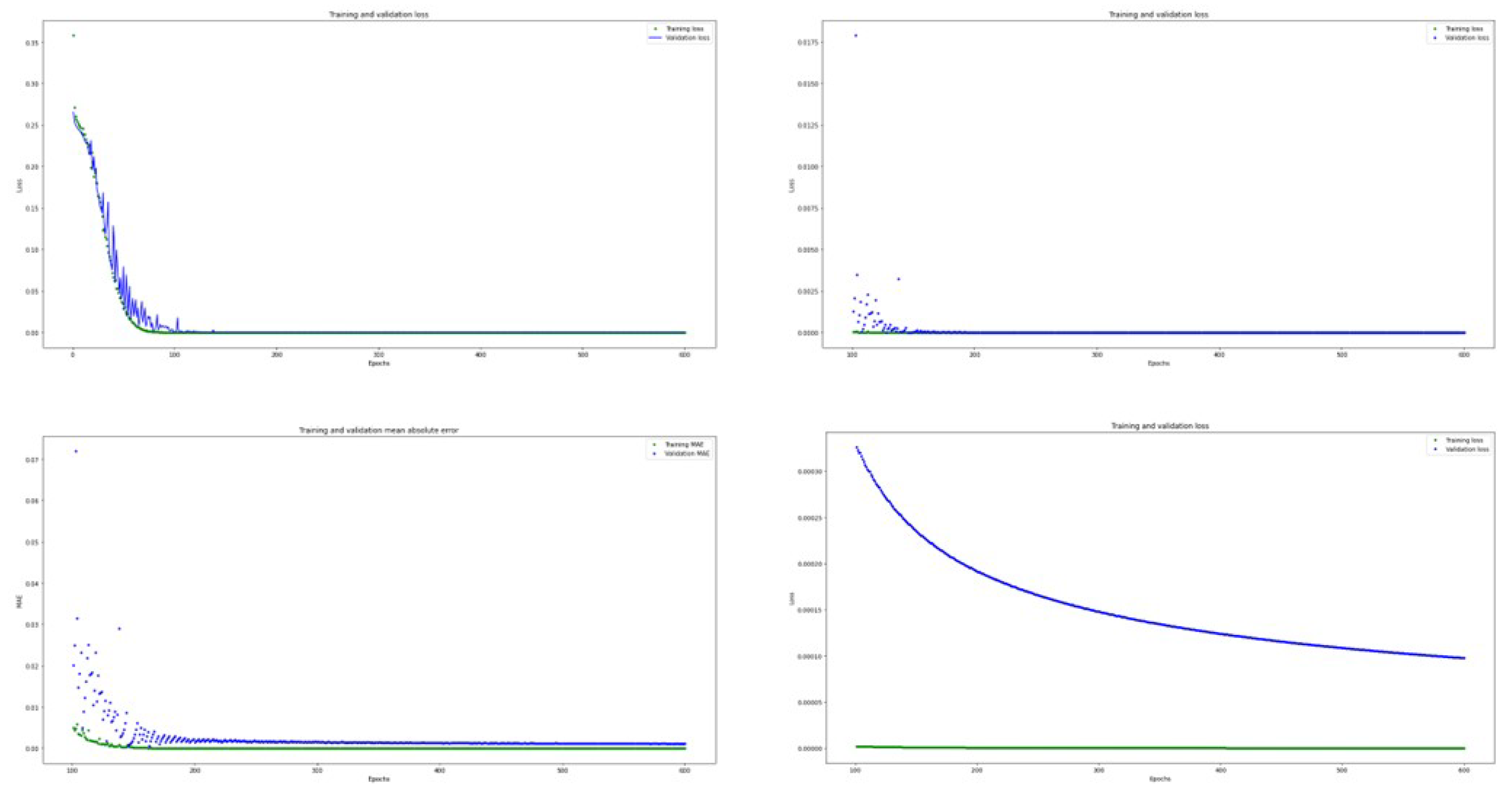

5.3. DNN Optimizing

Once the neural network is trained, the optimization process becomes crucial for further enhancing the performance and reliability of the model. During optimization, two primary metrics are typically examined: loss and Mean Absolute Error (MAE). As illustrated in

Figure 6, the top left image displays the results obtained using the twenty percent remaining data for validation. Notably, the figure shows that the loss begins to converge around the 100th epoch, indicating that the model achieves relatively stable performance at this point. To gain clearer insights into the convergence details, the researchers adjusted the code to skip the first 100 iterations, which exhibited large gradients and significant fluctuations (epochs 0-99), and instead focused on the optimization data from the 100th to the 600th epochs, as shown in the top right corner. The bottom left plot further illustrates how the MAE evolves from the 100th to the 600th iteration, visually confirming that the model’s error gradually decreases and eventually stabilizes. Following several iterations of training and optimization, the team successfully obtained a smoother loss curve, as depicted in the bottom right image. This smooth loss curve not only signifies that the model’s performance is more stable on the validation data but also demonstrates the effectiveness of the optimization process, thereby ensuring the model’s reliability in practical applications.

Hybrid Architecture of the Slow Sensor. A hybrid architecture is essential for developing the physical structure of smart slow sensors and integrating them into continuous components that necessitate multiple sensing capabilities at a longitudinal scale. The overall design of the sensor structure must be carefully considered to accommodate wearable, computable, and adaptive sensing performance. In this study, we accomplish this integration by leveraging TinyML in conjunction with Arduino Nano.

Physical Hardware to Digital Intelligence Transcendence. In wearable intelligent architecture, the selection of an appropriate intelligent carrier and the careful development of slow sensor characteristics are crucial. These elements form the foundation for bridging the gap between the physical and digital domains. By integrating innovative materials, advanced sensing technologies, and adaptable design principles, wearable architectures can facilitate seamless interaction between users and their environments.

Slow Sensor Agent Design. The capability of sensor intelligence is a crucial component in interaction design and represents a spectrum among various types of slow sensor and intelligent agents. The integration of slow sensors with neural networks necessitates careful consideration of wearable design, neural network architecture, hybrid structures, and advancements in digital technologies. As slow sensors mature, their potential for intelligence increases; however, this growth often introduces more complex design and operational challenges, resulting in a corresponding rise in time and resource costs. Balancing these aspects is vital to optimize the performance and efficiency of sensor systems in real-world applications.

6. Conclusions

The development of smart slow sensors represents a highly promising research area with significant applications in future smart architectures. However, during the design and experimental phases, the research team encountered a series of complex challenges, including limitations in material properties, insufficient data processing capabilities, and high training costs. These issues have been effectively addressed through systematic research methods and design innovations, establishing a solid foundation for the sustainable advancement of the field.

The integration of neural networks injects computational power into traditional slow sensors, enhancing their capabilities in information processing and complex environmental perception. This technological breakthrough not only improves the functionality of sensors but also significantly expands their application scenarios from single sensing to multi-dimensional intelligent sensing. Additionally, the introduction of few-shot learning techniques has successfully reduced the training costs associated with DNN, making the development of slow sensors more cost-effective by decreasing reliance on large-scale data sets and providing more flexible research and development conditions for smaller teams.

Additionally, critical progress has been achieved in the purification and standardization of experimental procedures. By precisely manipulating experimental variables, the team optimized the specific sensing capabilities of the slow sensor. For instance, by focusing on the capture ability related to hand motion perception, researchers implemented targeted improvements based on specific needs, significantly enhancing the adaptability and reliability of the devices.

More importantly, the introduction of agents offers a new perspective on the evolutionary perception of slow sensors. The shift from discrete to continuous perception not only marks a technical breakthrough but also represents an innovation in cognitive processes. The adaptive learning and feedback mechanisms of the agents enable slow sensors to become more sensitive to subtle changes in dynamic environments, thereby facilitating the development of a more continuous and comprehensive perception system. In the future, this direction is expected to further advance the evolution of smart sensors, unlocking new possibilities in intelligent computing, information visualization, and human-computer interaction.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the School of Design and Art, Beijing Institute o Technology, Zhuhai in project ZX-2020-031 and National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan in project NSTC 112-2410-H-224-016-MY2.

References

- Wang, J.; Wang, D.; Zhang, F.; Yoo, C.; Liu, H. Soft sensor for predicting indoor PM2.5 concentration in subway with adaptive boosting deep learning model. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 465, 133074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Razman, M.R.; Syed Zakaria, S.Z.; Lee, K.E.; Khan, S.U.; Albanyan, A. Personalized context-aware systems for sustainable agriculture development using ubiquitous devices and adaptive learning. Computers in Human Behavior 2024, 160, 108375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urhan, A.; Alakent, B. Integrating adaptive moving window and just-in-time learning paradigms for soft-sensor design. Neurocomputing 2020, 392, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Mishra, R.; Golledge, J.; Najafi, B. Digital biomarkers of physical frailty and frailty phenotypes using sensor-based physical activity and machine learning. Sensors 2021, 21, 5289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, Z.; Brown, C.; Madni, A.M.; Ozcan, A. Machine learning and computation-enabled intelligent sensor design. Nature Machine Intelligence 2021, 3, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Ukil, A.; Deb, T.; Sahu, I.; Majumdar, A. Instant adaptive learning: An adaptive filter based fast learning model construction for sensor signal time series classification on edge devices. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2020-2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); IEEE, 2020; pp. 8339–8343. [Google Scholar]

- Villaverde, M.; Perez, D.; Moreno, F. Self-learning embedded system for object identification in intelligent infrastructure sensors. Sensors 2015, 15, 29056–29078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Jiang, S. The Research Process and Challengeof Logistic Sensors in Smart Cool Chain. Journal of Sensor Technology and Application 2016, 04, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.W.; Tsai, S.T.; Huang, H.Y.; Wu, Y.S.; Chang, C.C.; Datta, S. Slow Well-Being Gardening: Creating a Sensor Network for Radiation Therapy Patients via Horticultural Therapeutic Activity. Sensors 2024, 24, 3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.W.; Huang, H.Y.; Hong, C.C.; Datta, S.; Nakapan, W. SENS+: A Co-Existing Fabrication System for a Smart DFA Environment Based on Energy Fusion Information. Sensors 2023, 23, 2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.W.; Huang, H.Y.; Hung, C.W.; Datta, S.; McMinn, T. A network sensor fusion approach for a behaviour-based smart energy environment for Co-making spaces. Sensors 2020, 20, 5507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.R.; Chang, T.W.; Wu, Y.S. HIGAME+ - Planting as a medium to connect IOT objects in different environments to emotionally interact with elderly people alone. CAADRIA proceedings 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.S.; Chang, T.W.; Datta, S. HiGame: Improving elderly well-being through horticultural interaction. International Journal of Architectural Computing 2016, 14, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.S.; Chang, T.W.; Datta, S. Developing the Interaction for Family Reacting with Care to Elderly. In Proceedings of the Interacción; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Benfradj, A.; Thaljaoui, A.; Moulahi, T.; Khan, R.U.; Alabdulatif, A.; Lorenz, P.; et al. Integration of artificial intelligence (AI) with sensor networks: Trends, challenges, and future directions. Journal of King Saud University-Computer and Information Sciences 2024, 36, 101892. [Google Scholar]

- Holzinger, A.; Keiblinger, K.; Holub, P.; Zatloukal, K.; Müller, H. AI for life: Trends in artificial intelligence for biotechnology. New Biotechnology 2023, 74, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Rab, S.; Suman, R. Significance of sensors for industry 4.0: Roles, capabilities, and applications. Sensors International 2021, 2, 100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajak, P.; Ganguly, A.; Adhikary, S.; Bhattacharya, S. Internet of Things and smart sensors in agriculture: Scopes and challenges. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2023, 14, 100776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Kumar, R.R.; Ghosh, A.; Lin, S.P. Perspective of smart self-powered neuromorphic sensor and their challenges towards artificial intelligence for next-generation technology. Materials Letters 2022, 310, 131541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, A.; Larsson, S.; Götvall, P.L.; Bengtsson, K. Deliberative safety for industrial intelligent human–robot collaboration: Regulatory challenges and solutions for taking the next step towards industry 4.0. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing 2022, 78, 102386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Cai, J.; Jiang, X.; Li, S. A subspace ensemble regression model based slow feature for soft sensing application. Chinese Journal of Chemical Engineering 2020, 28, 3061–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, J.; Munawar, H.S.; Kouzani, A.Z.; Mahmud, M.P. Using adaptive sensors for optimised target coverage in wireless sensor networks. Sensors 2022, 22, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alakent, B. Soft sensor design using transductive moving window learner. Computers & Chemical Engineering 2020, 140, 106941. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikary, S.; Dutta, S.; Dwivedi, A.D. TinyWolf—Efficient on-device TinyML training for IoT using enhanced Grey Wolf Optimization. Internet of Things 2024, 28, 101365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, A. Navigating the Nexus of AI and IoT: A Comprehensive Review of Data Analytics and Privacy Paradigms. Internet of Things 2024, 101318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gookyi, D.A.N.; Wulnye, F.A.; Arthur, E.A.E.; Ahiadormey, R.K.; Agyemang, J.O.; Agyekum, K.O.B.O.; Gyaang, R. TinyML for Smart Agriculture: Comparative Analysis of TinyML Platforms and Practical Deployment for Maize Leaf Disease Identification. Smart Agricultural Technology 2024, 100490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragkou, E.; Koultouki, M.; Katsaros, D. Model reduction of feed forward neural networks for resource-constrained devices. Applied Intelligence 2023, 53, 14102–14127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Peng, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y. A cost-sensitive attention temporal convolutional network based on adaptive top-k differential evolution for imbalanced time-series classification. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 213, 119073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lê, M.T.; Wolinski, P.; Arbel, J. Efficient neural networks for tiny machine learning: A comprehensive review. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.11883 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tonga, P.A.; Ameen, Z.S.; Mubarak, A.S.; Al-Turjman, F. A review on on device privacy and machine learning training. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Everything (AIE). IEEE; 2022; pp. 679–684. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, P.; Deng, M.; Kang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Xu, L. Self-adaptive learning of task offloading in mobile edge computing systems. Entropy 2021, 23, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. The future of hardware development: a perspective from systems researchers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Workshop on Hot Topics in Operating Systems, 2021, pp.; pp. 236–237.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).