Submitted:

12 September 2025

Posted:

15 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Background

2.2. Previous Efforts with Tutorials

2.3. CCPS Testbed Data Collection

2.4. ElectricDot

2.5. Design Requirements

- Must use Python

- Must focus on time series/sensor data.

- Minimize coding

- Easy to use

- Must assist in training and testing

- Must include metrics

- visualization of data and results

- Must have an accompanying tutorial

- Must include digital signal processing, classification, clustering, regression, and anomaly detection.

- Must have a Graphical User Interface

- Core functionality must be directly accessible

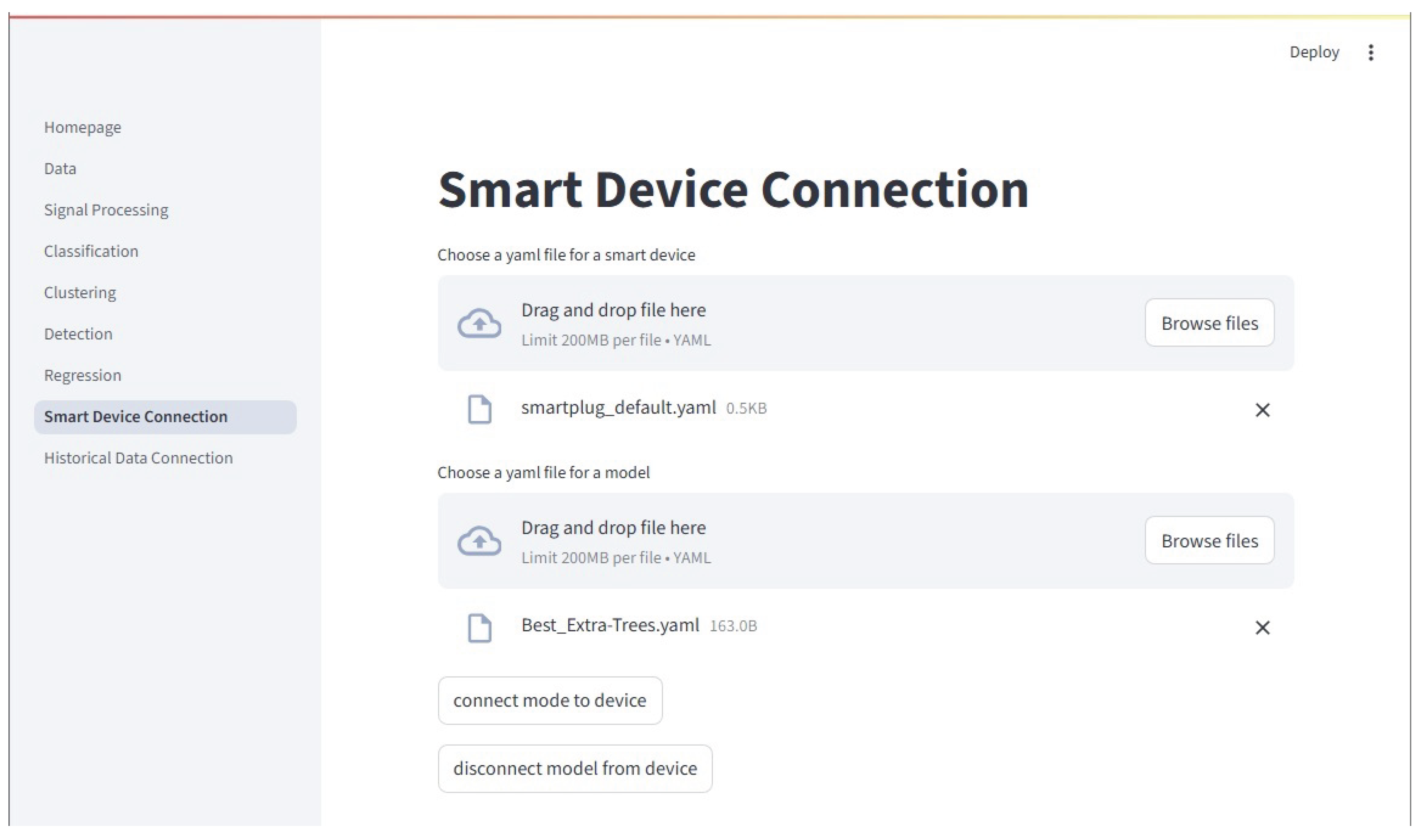

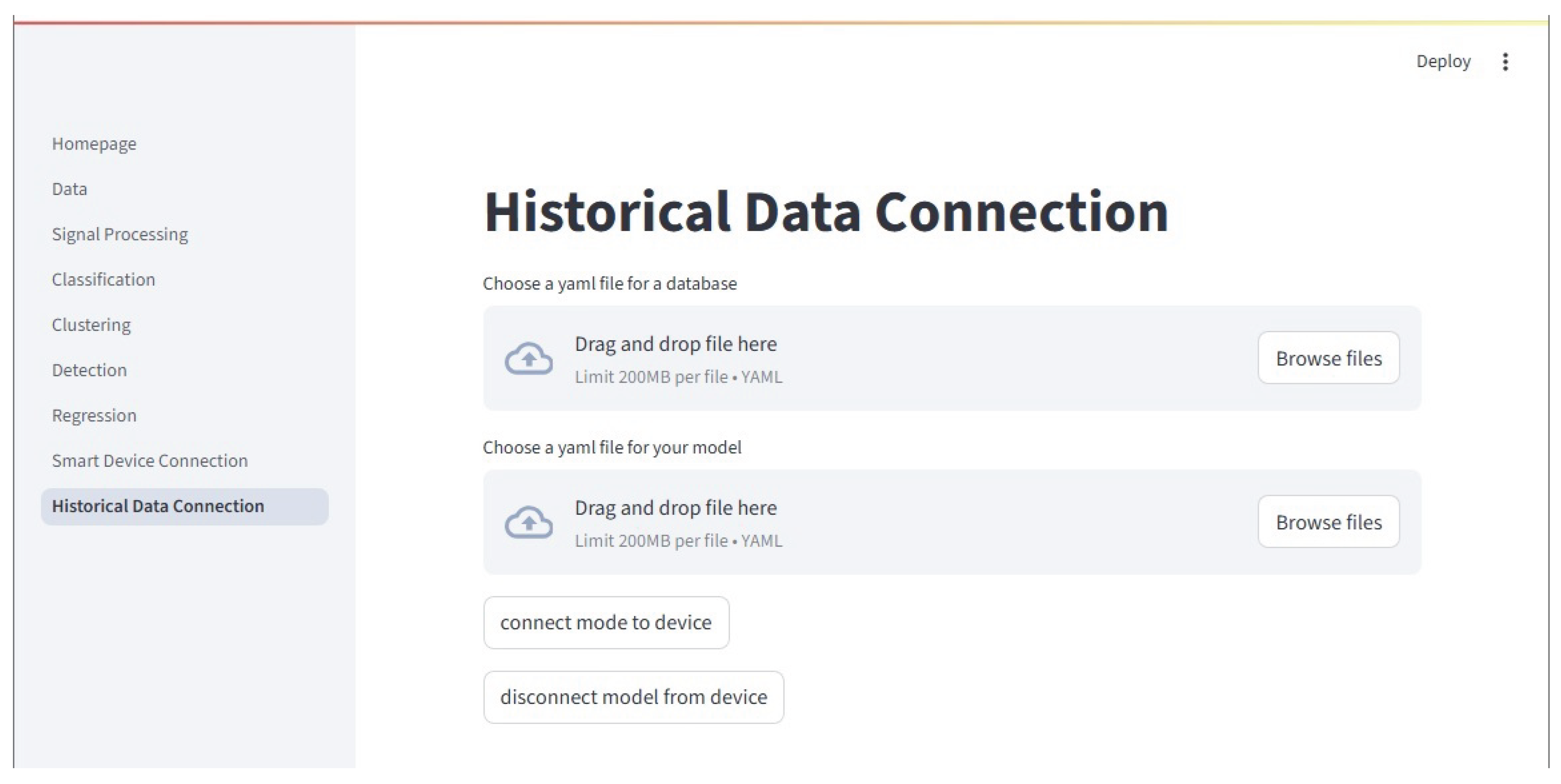

- Must enable smart device and historical data connectivity to models

2.6. Design Part 1: Core Functionality & Tutorial

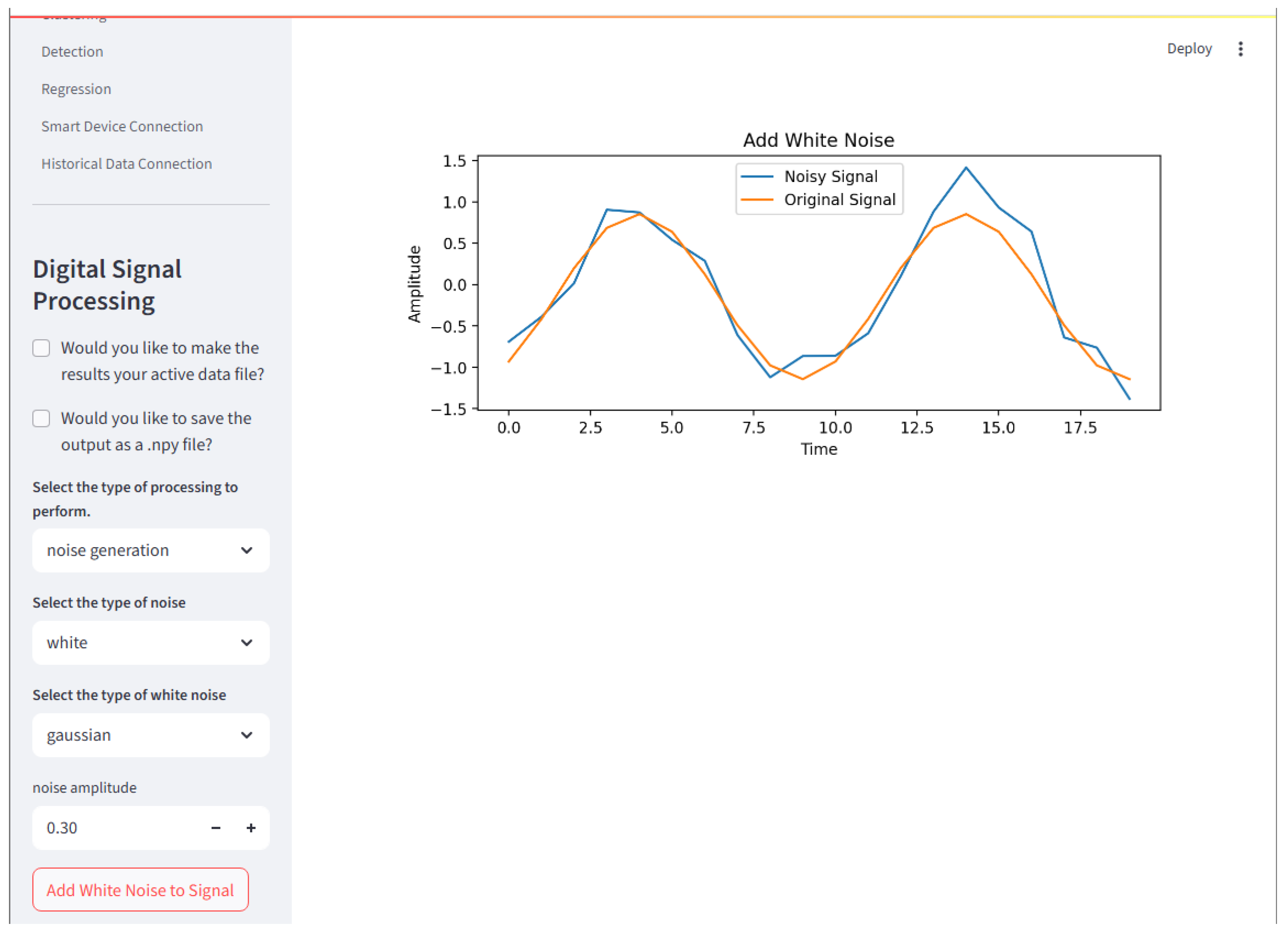

2.6.1. Digital Signal Processing

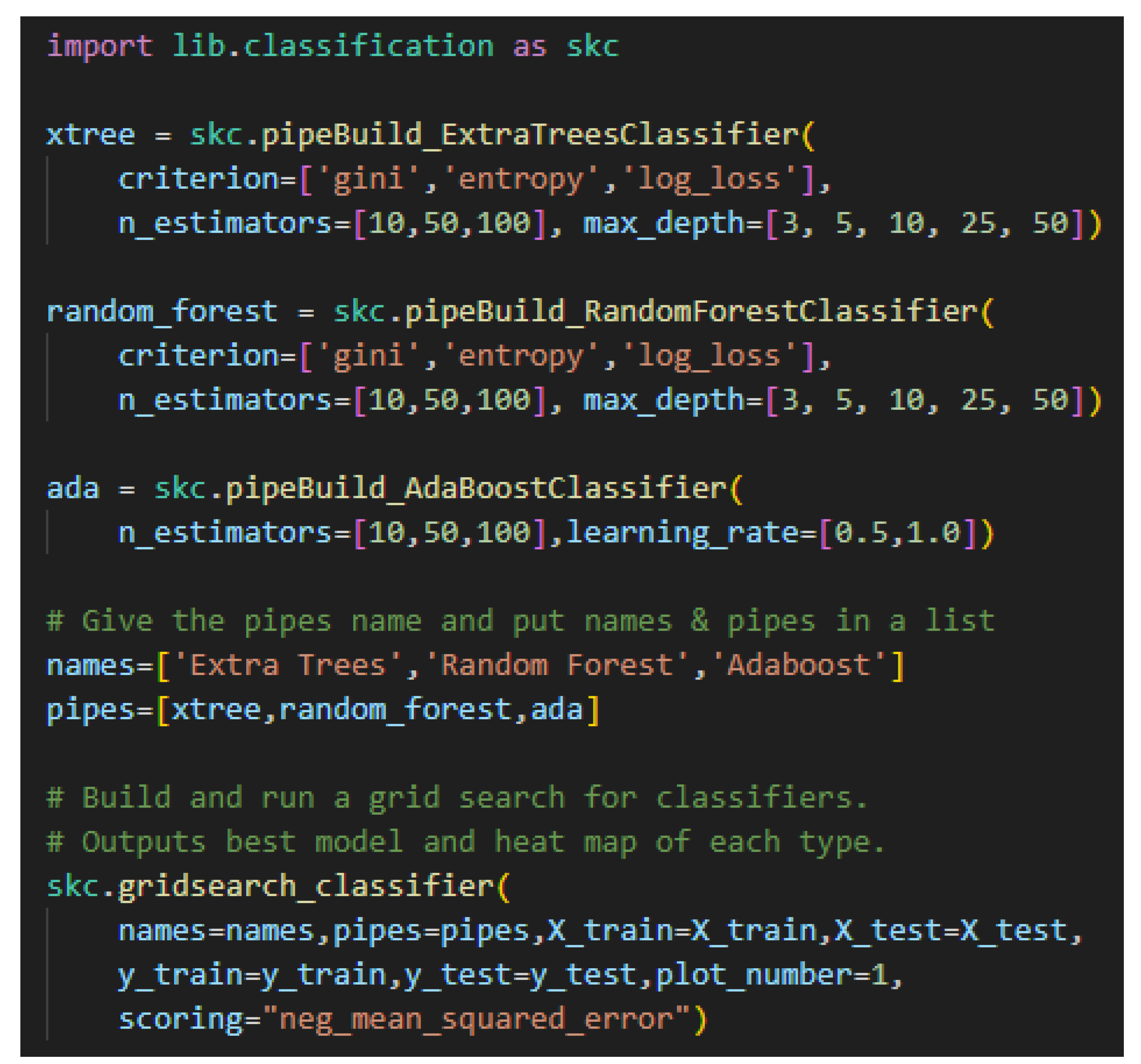

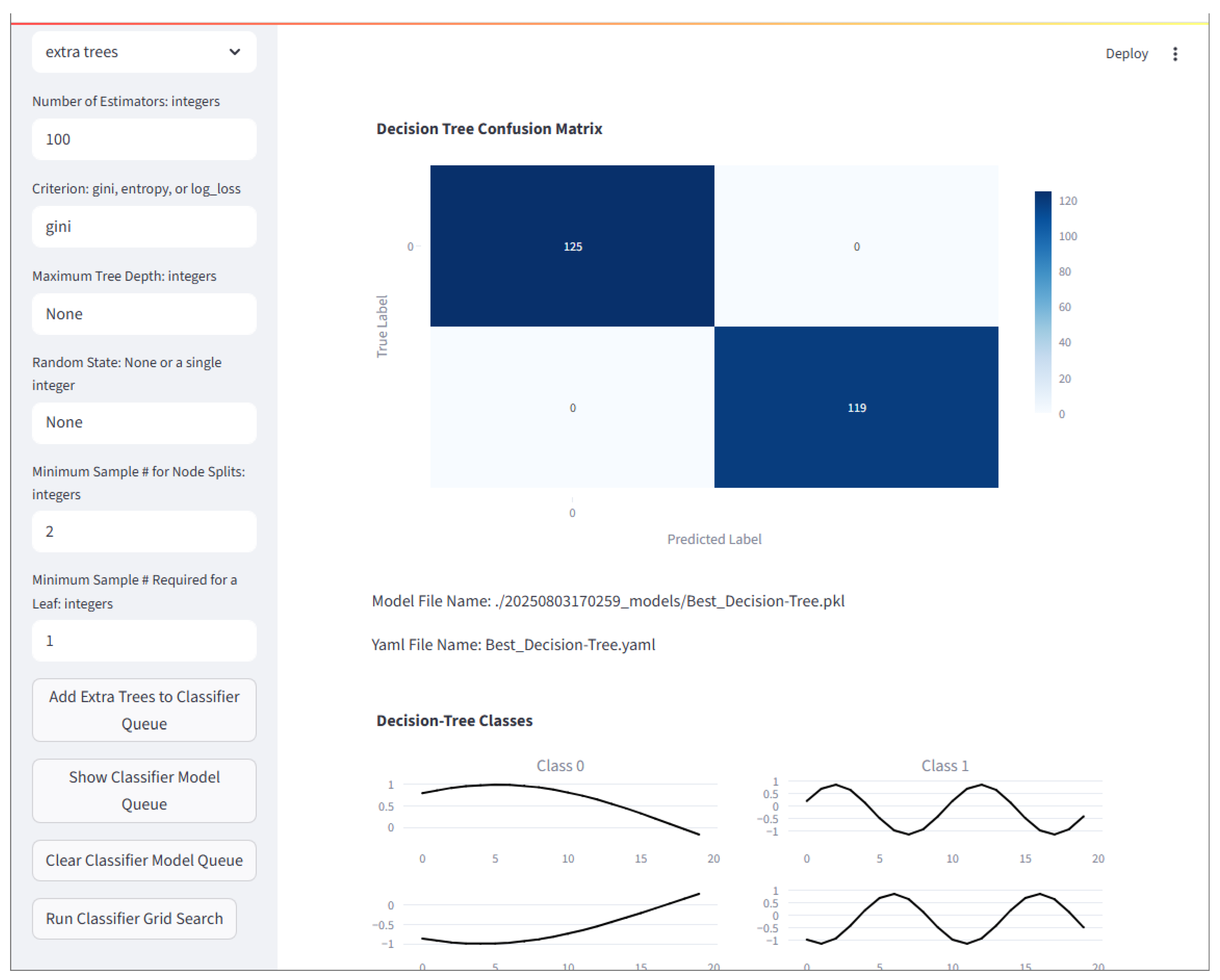

2.6.2. Classification

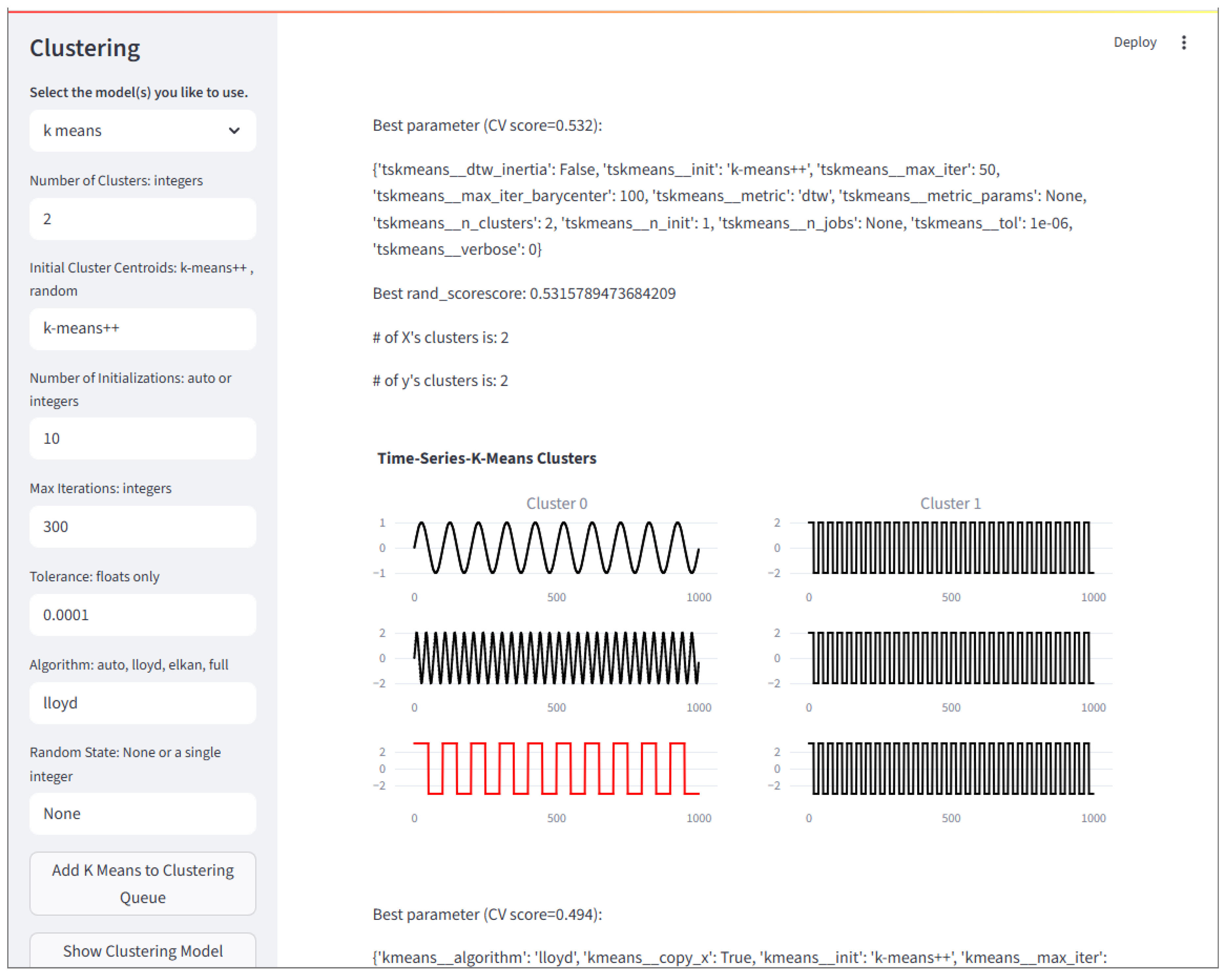

2.6.3. Clustering

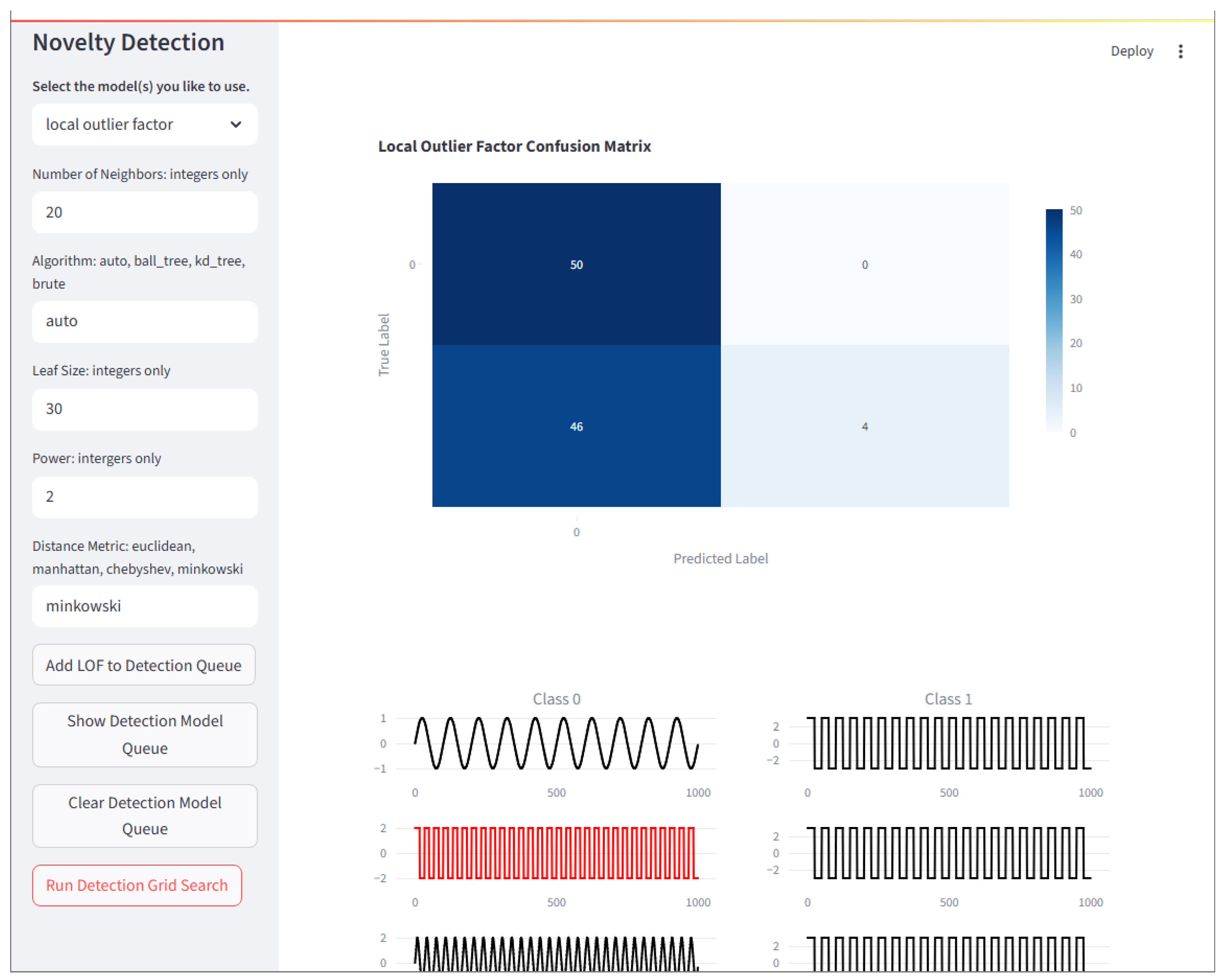

2.6.4. Detection

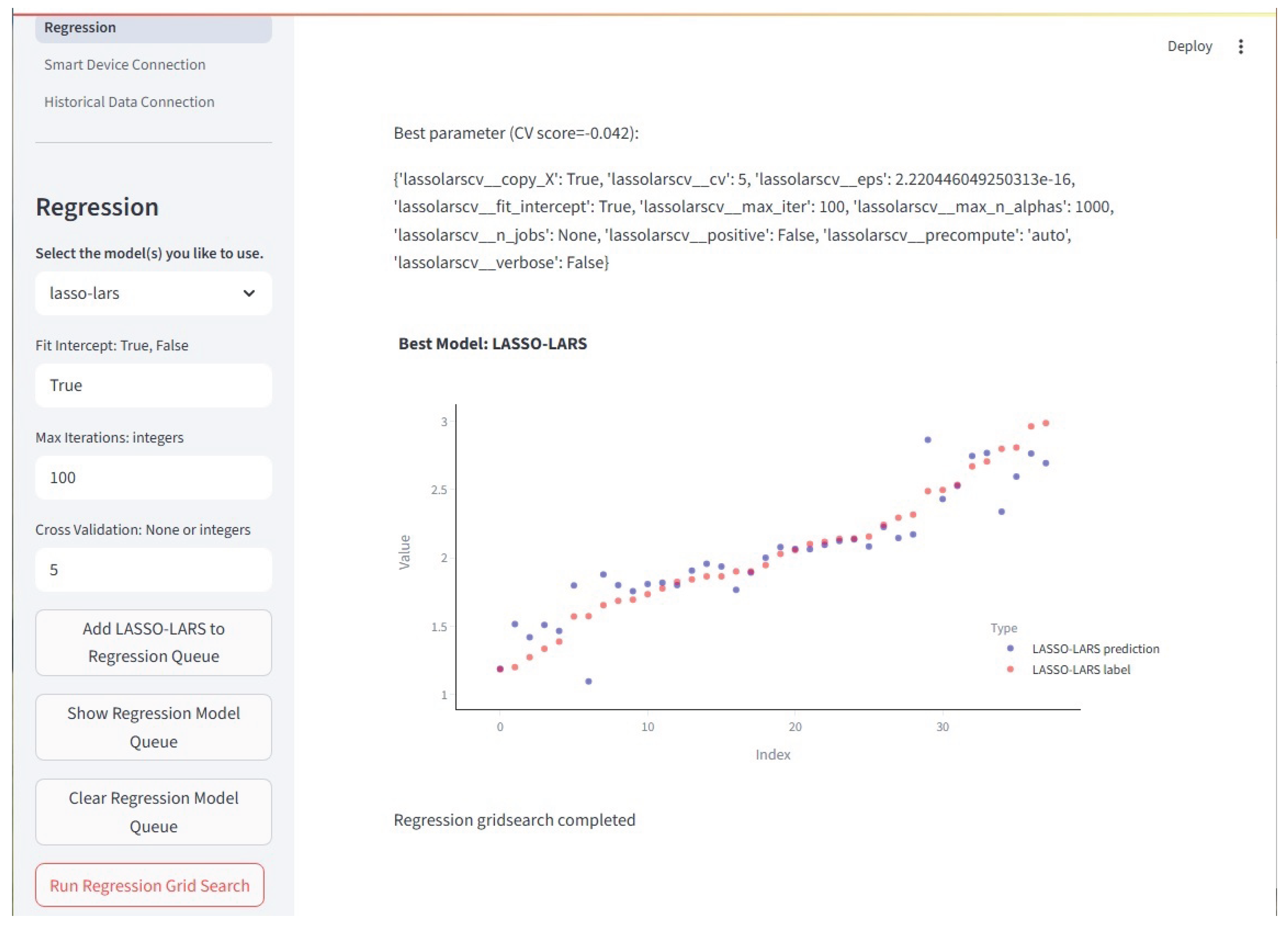

2.6.5. Regression

2.6.6. Utilities

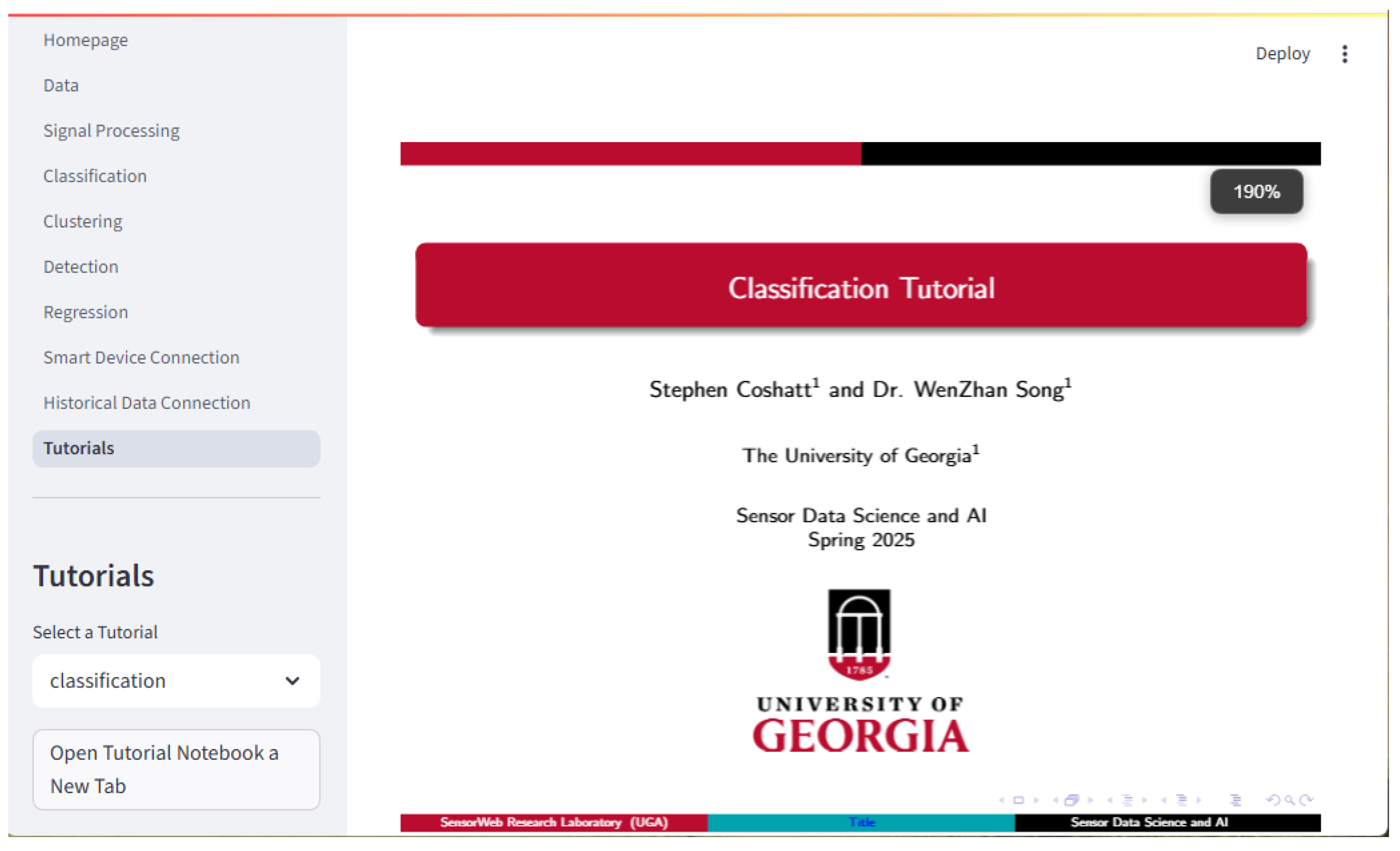

2.6.7. Framework Tutorial

- DSP: wave generation, noise, filters, transforms, decomposition, power spectral density, wavelet analysis & transforms

- Classification: decision trees, nearest neighbors, support vector machines, bagging, boosting, others

- Clustering: hierarchical, k-means, k-shape, density based, spectral, others

- Anomaly Detection: outlier vs novelty detection, isolation forests, local outlier factor, others

- Regression: generalized linear models, lars, lasso, ridge, elastic nets, nearest neighbors, support vector machines, others

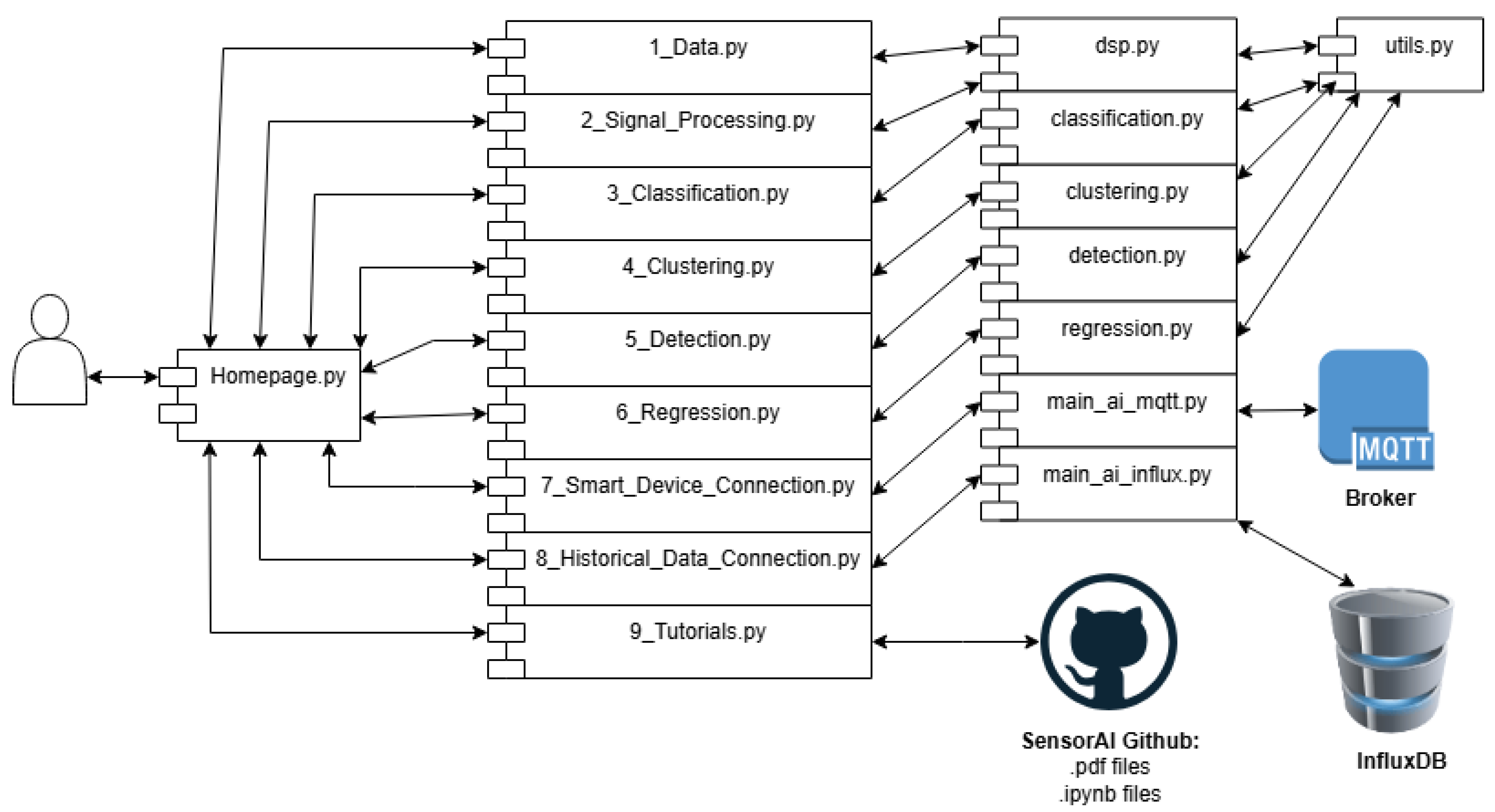

2.7. Design Part 2: Graphical User Interface & Testbed Integration

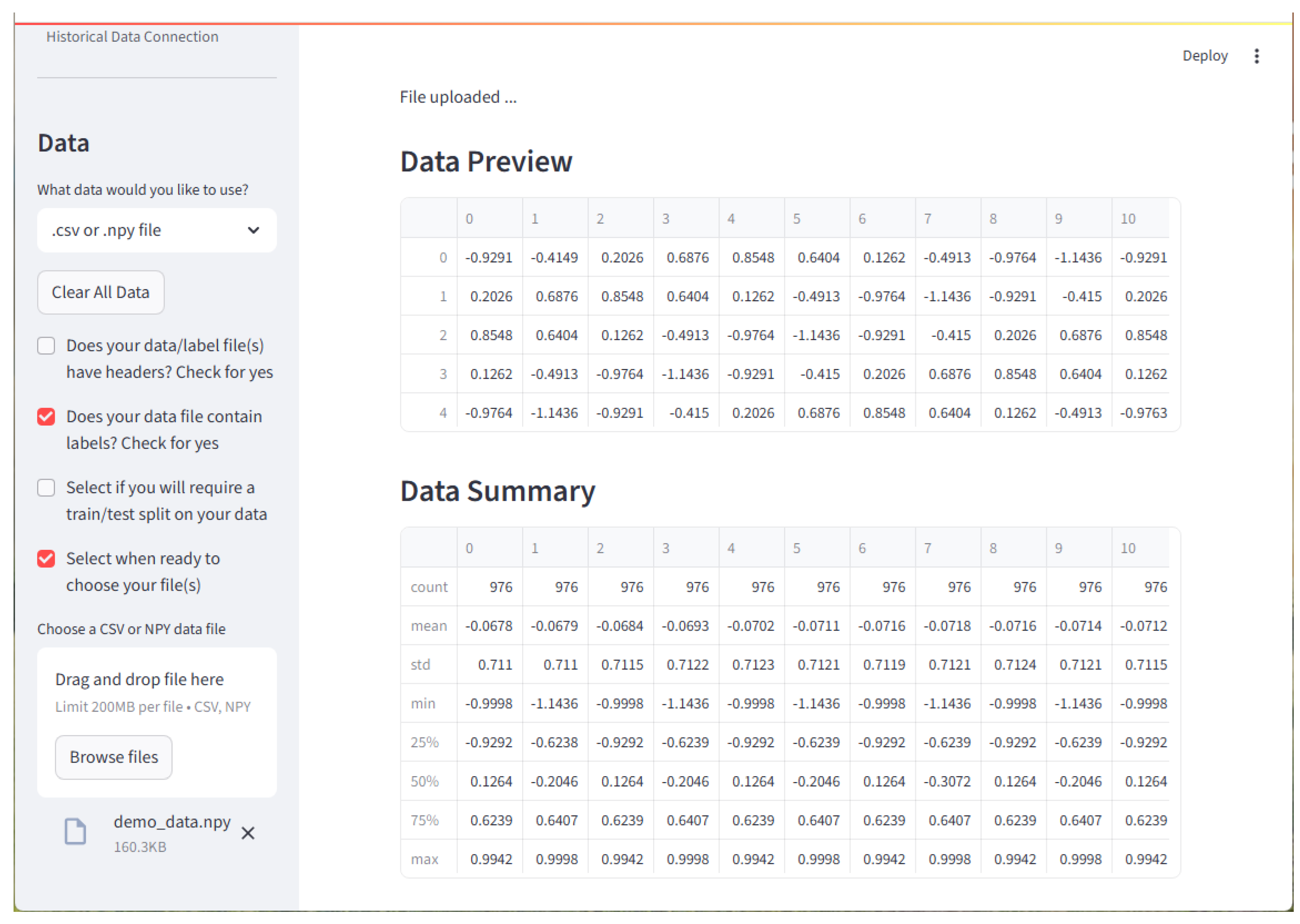

2.7.1. Data

2.7.2. Digital Signal Processing

2.7.3. Classification

2.7.4. Clustering

2.7.5. Detection

2.7.6. Regression

2.7.7. Device Connector

2.7.8. Historical Download

2.7.9. Tutorials

3. Results

3.1. Data

3.2. Framework Model Comparisons

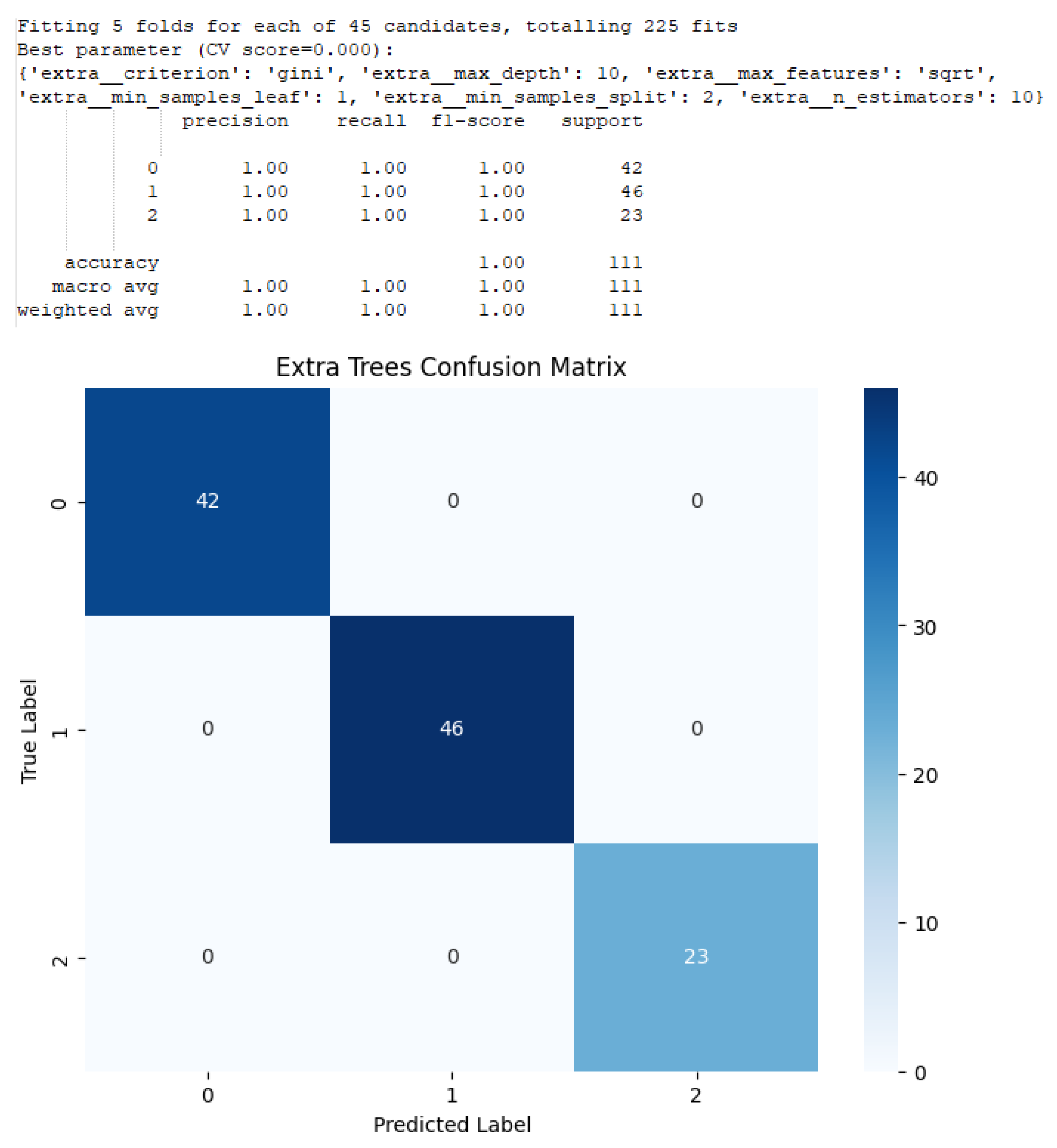

4. Discussion

4.1. Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CCPS | Center for Cyber-Physical Systems |

| CWT | Continuous Wavelet Transform |

| DBSCAN | Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise |

| DSP | Digital Signal Processing |

| ECU | Electronic Control Unit |

| eDOt | ElectricDot |

| Elastic-Net | Elastic-Net Regularization |

| EMD | Empirical Mode Decomposition |

| FDIA | False Data Injection |

| FFT | Fast-Fourier Transform |

| FOC | Field-Orient Control |

| GAK | Global Alignment Kernel |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| GUI | Graphical User Interface |

| IT | Information Technology |

| KNN | K Nearest Neighbors |

| LARS | Least Angle Regression Shrinkage |

| LASSO | d Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator |

| MQTT | Message Queuing Telemetry Transport |

| OPTICS | Ordering Points To Identify the Clustering Structure |

| OT | Operational Technology |

| PCC | Point of Common Coupling |

| PCT | Polynomial Chirplet Transform |

| RANSAC | Random Sample Consensus |

| SCG | Seismocardiography |

| SSA | Singular Spectrum Analysis |

| SST | SynchroSqueezing Transform |

| STFT | Short Time Fourier Transform |

| THD | Total Harmonic Distortion |

| TS KNN | Time Series K Nearest Neighbors |

| UGA | University of Georgia |

| WVD | Wigner-Ville Distribution |

References

- Weerts, H.J.P.; Pechenizkiy, M. Teaching responsible machine learning to engineers. In Proceedings of the The Second Teaching Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence Workshop. PMLR, 2022, pp. 40–45.

- Selmy, H.A.; Mohamed, H.K.; Medhat, W. A predictive analytics framework for sensor data using time series and deep learning techniques. Neural Computing and Applications 2024, 36, 6119–6132.

- Lasi, H.; Fettke, P.; Kemper, H.G.; Feld, T.; Hoffmann, M. Industry 4.0. Business & information systems engineering 2014, 6, 239–242.

- Lu, Y. The current status and developing trends of industry 4.0: A review. Information Systems Frontiers 2025, 27, 215–234.

- Ambadekar, P.K.; Ambadekar, S.; Choudhari, C.; Patil, S.A.; Gawande, S. Artificial intelligence and its relevance in mechanical engineering from Industry 4.0 perspective. Australian Journal of Mechanical Engineering 2025, 23, 110–130.

- Putnik, G.D.; Ferreira, L.; Lopes, N.; Putnik, Z. What is a Cyber-Physical System: Definitions and Models Spectrum. Fme Transactions 2019, 47.

- Chen, Y.; Tu, L. Density-based clustering for real-time stream data. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 13th ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining, 2007, pp. 133–142.

- Coshatt, S.J.; Li, Q.; Yang, B.; Wu, S.; Shrivastava, D.; Ye, J.; Song, W.; Zahiri, F. Design of cyber-physical security testbed for multi-stage manufacturing system. In Proceedings of the GLOBECOM 2022-2022 IEEE Global Communications Conference. IEEE, 2022, pp. 1978–1983.

- Yang, H.; Yang, B.; Coshatt, S.; Li, Q.; Hu, K.; Hammond, B.C.; Ye, J.; Parasuraman, R.; Song, W. Real-world Cyber Security Demonstration for Networked Electric Drives. IEEE Journal of Emerging and Selected Topics in Power Electronics 2025, pp. 1–1. https://doi.org/10.1109/JESTPE.2025.3550830.

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2011, 12, 2825–2830.

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nature Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-019-0686-2.

- Tavenard, R.; Faouzi, J.; Vandewiele, G.; Divo, F.; Androz, G.; Holtz, C.; Payne, M.; Yurchak, R.; Rußwurm, M.; Kolar, K.; et al. Tslearn, A Machine Learning Toolkit for Time Series Data. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2020, 21, 1–6.

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Computing in Science & Engineering 2007, 9, 90–95. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCSE.2007.55.

- Inc., P.T. Collaborative data science, 2015.

- Song, W.; Coshatt, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J. Sensor Data Science and AI Tutorial, 2024.

- Cuturi, M. Fast global alignment kernels. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 28th international conference on machine learning (ICML-11), 2011, pp. 929–936.

| Module File Name | Module Information |

|---|---|

| classification.py | Classification, Supervised Anomaly Detection |

| clustering.py | Clustering |

| detection.py | Unsupervised Anomaly Detection |

| dsp.py | Digital Signal Processing |

| regression.py | Regression |

| utils.py | Plotting and other Miscellaneous functions |

| Module | Slides and Notebooks |

|---|---|

| Classification | classification_slides.pdf, classification_tutorial.ipynb |

| Clustering | unsupervised_slides.pdf, unsupervised_tutorial.ipynb |

| DSP | dsp_slides.pdf, dsp_tutorial.ipynb |

| Regression | regression_slides.pdf, regression_tutorial.ipynb |

| Supervised | classification_slides.pdf, classification_tutorial.ipynb |

| Detection | |

| Unsupervised | unsupervised_slides.pdf, unsupervised_tutorial.ipynb |

| Detection |

| Model | Average Scores from 10 runs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 Score |

| AdaBoost (trees) | 0.995 | 0.995 | 0.995 | 0.995 |

| Bagging (trees) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Decision Tree | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Extra Trees | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Gradient Boosting | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Histogram Grad. Boost | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| KNN | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Random Forest | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| TS KNN | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).