1. Introduction

The respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a globally prevalent pathogen and the leading cause of acute lower respiratory tract infections in infants and young children. In 2019, it was estimated that 33 million cases of RSV-associated acute lower respiratory tract infections occurred in children aged 0–60 months, causing a significant healthcare burden [

1]. In addition, the disease burden of RSV in older adults is underestimated. Older adults face an increased risk of RSV-related complications and mortality owing to immunosenescence and underlying diseases [

2]. In 2023, two pre-fusion (pre-F) subunit vaccines from GSK and Pfizer were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in adults or older people [

3,

4]. Currently, no RSV vaccines are approved for use in China.

RSV is a single-stranded, negative-strand RNA virus belonging to the

Pneumoviridae family and genus

Orthopneumovirus. The RSV genome is approximately 15 kb and encodes 11 distinct proteins [

2]. The RSV fusion (F) protein is the main antigen responsible for inducing neutralising antibodies [

5,

6], and it is relatively conserved across different strains, making it an ideal target for vaccine development. The F protein exists in two conformations: pre-F and post-fusion (post-F). Neutralising antibodies recognise epitopes on pre-F compared to those on post-F. Furthermore, neutralising antibodies found in human serum are predominantly induced by pre-F [

7,

8]. Therefore, the pre-F is an important target for developing RSV antiviral drugs a1d vaccines.

As a rapidly developing vaccine platform, mRNA vaccines can be quickly developed and mass-produced in cell-free environments, offering significant prospects for widespread application [

9]. These vaccines play an important role in controlling the spread of COVID-19 and have facilitated the development of vaccines targeting various respiratory pathogens. Owing to the inherently unstable nature of RNA, a safe and efficient delivery system is required to protect mRNA from degradation [

10]. The currently marketed mRNA-1345, which encodes the membrane-anchored RSV pre-F protein, achieved the primary efficacy endpoints in Phase 3 trials in older adults using the same lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) as the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine [

5]. However, after intramuscular injection, LNPs are not completely restricted to muscle tissue but are rapidly distributed throughout the body, accumulating in large quantities in the liver. Systemic exposure to mRNA-LNPs may lead to off-target transgene expression, leading to adverse effects such as inflammation, allergy reactions, and haemolysis. Additionally, overexpression in the liver may lead to potential adverse reactions [

11]. However, to avoid these problems, we used a lipopolyplex (LPP) platform with a core-shell structure to prepare mRNA vaccines. The LPP delivery platform contains polymer-coated mRNA molecules encapsulated within a bilayer phospholipid shell. LPP expresses mRNA predominantly at the site of intramuscular injection and preferentially in the spleen rather than in the liver after vascular leakage. This targeted expression may alleviate concerns regarding potential off-target effects and systemic toxicity. LPP, a key component of vaccine formulations, exhibits superior colloidal stability, high encapsulation efficiency, and optimal biodistribution pattern. LPP mRNA enhances the activation of the TLR7/8 signalling pathway in dendritic cells, leading to the secretion of type I interferons [

12]. IFN levels in nasal washes and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in adults and children negatively correlate with disease severity [

13]. Thus, LPP-mRNA vaccines may induce robust antiviral responses. COVID-19 mRNA vaccines based on the LPP platform have been previously reported [

12], but they remain unapplied in RSV vaccine development.

In this study, we prepared an LPP-based mRNA vaccine expressing the RSV pre-F protein with gene modification, then evaluated its humoral and cellular immune responses in mice. Furthermore, the long-lasting protective effects induced by two doses of the vaccine were compared in mice at 24 weeks post-vaccination.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells, viruses, and animals

The Hep-2 and HEK-293T cells used in this study were all cultured in Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium (Gibco™, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (PAN, Cat:P30-3302) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (PS, Cat:15140-122). The RSV A2 strain, B18537 strain, and the clinical strain hRSV/C-Tan/BJ 202301 were preserved at the Institute for Viral Disease Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Female Balb/c mice (6–8 weeks old, SPF grade) were purchased from Beijing Sibeifu Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China), and they were reared at the Animal Center of Beijing Kexing Vaccine Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). All animal experiments were conducted according to ethical regulations and were approved by the local ethics committee (Animal Ethics No. 20231128092).

2.2. Construction and preparation of mRNA vaccine expressing RSV pre-F protein

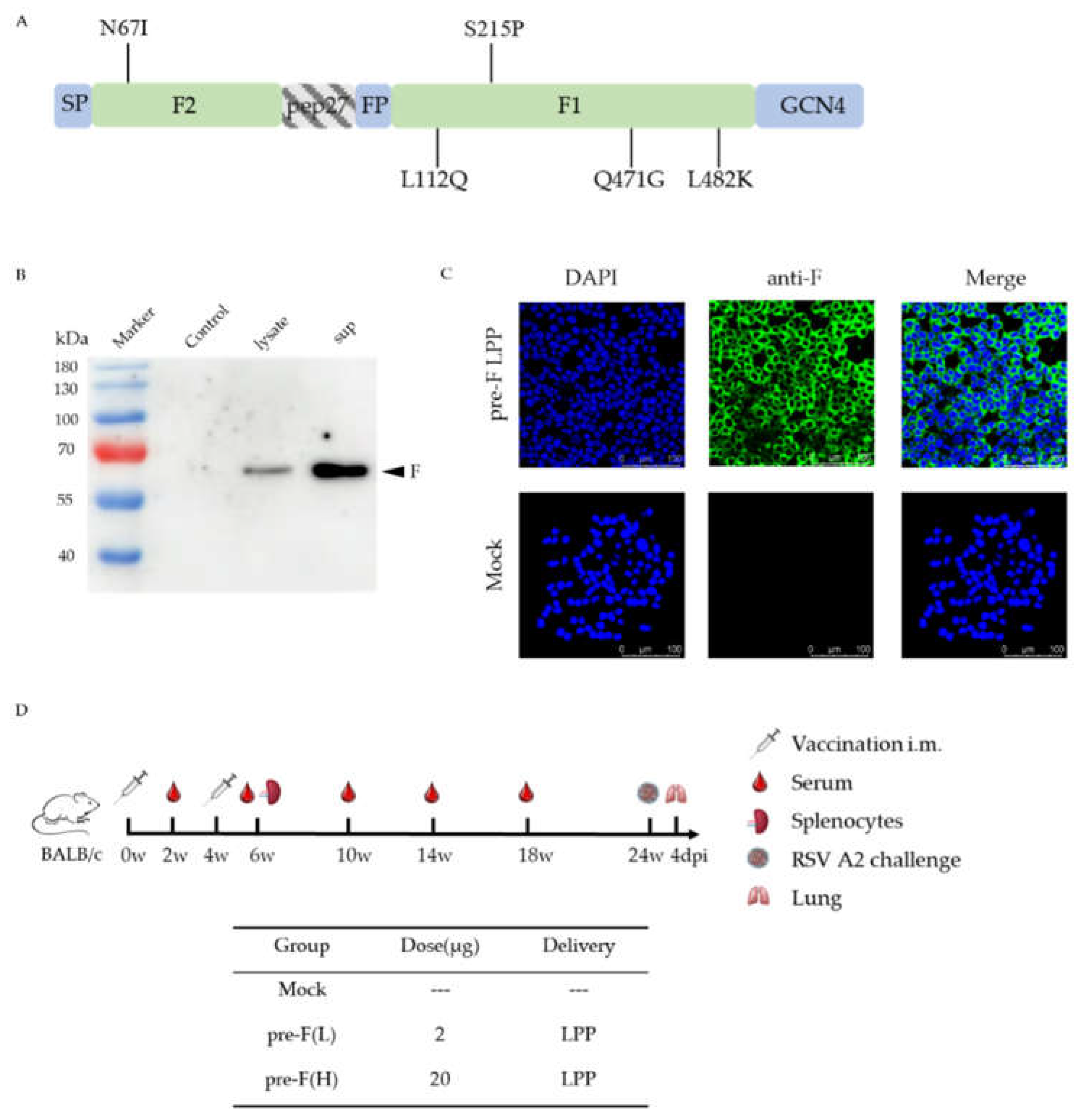

The recombinant RSV pre-F protein was designed with reference to the relevant literature [

14,

15]. Peptide 27 was deleted, while a Lys residue at one of the two furin sites was conserved. Mutations were introduced at L112Q, Q471G, and L482K to stabilise the F protein in the pre-F conformation and reduce protein hydrolysis. Additionally, mutations at N67I and S215P increased the protein expression levels. The transmembrane structural domain and cytoplasmic region at the C-terminal of the F protein were substituted with the GCN4 trimeric motif to stabilise the F protein as a trimer. The pre-F sequences were synthesised by codon optimisation and RSV pre-F -mRNA with LPP encapsulation in Shanghai Stemirna [

12], (

Figure 1A).

2.3. Western Blotting

To analyse the expression of RSV F protein, HEK-293T cells were transiently transfected with RSV pre-F-mRNA, and the resulting supernatant and cell lysate were collected 6 h post-transfection. The proteins were harvested by lysis buffer and then boiled for 10 min. Denatured samples were separated using 10% sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and subsequently transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. An anti-RSV polyclonal antibody (Abcam, USA) was used at a dilution of 1:1000, followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated (HRP) rabbit anti-goat IgG secondary antibody (ZSGB-BIO, China) at a dilution of 1:5000. The membranes were developed using a chemiluminescent substrate and analysed with a chemiluminescent imager (

Figure 1B).

2.4. Immunofluorescence Assay

HEK-293T cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Hyclone, South Logan, UT, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, NY, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) in a 5% CO

2 incubator at 37°C. HEK-293T cells were transiently transfected with RSV pre-F-mRNA, then cells were fixed in pre-cooled 4% paraformaldehyde, mobilised in 0.2% Triton X-100, and blocked by 10% goat serum in phosphate-buffered saline. Subsequently, anti-RSV F protein monoclonal antibody (Sino Bioligical, China) was used as the primary antibody. After incubation, cells were washed and incubated with secondary antibodies [fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labelled goat anti-rabbit IgG (ZSGB-BIO, China)] at room temperature for 1 h. Subsequently, the samples were washed and incubated with 4’,6-diamino-2-phenylindol (DAPI, Beyotime, China) for 10 min. Fluorescent images were acquired using a Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscope with LAS software (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany), (

Figure 1C).

2.5. Immunisations

Mice were divided randomly into three groups and immunised with 20 μg(H) of and 2 μg (L) of RSV pre-F-mRNA, respectively. The control group was injected with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The mice were immunised two times at 4-week intervals. Blood samples were collected 2 weeks after each immunisation to analyse the humoral immune response. Splenocytes were isolated 2 weeks after the boost immunisation to analyse the cellular immune response. Additional blood samples were collected at 10, 14, and 18 weeks post-prime to evaluate long-lasting immunity (

Figure 1D).

2.6. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

To detect humoral immune response, ELISA was performed as previously described [

16]. Briefly, plates (Corning, Shanghai, China, Asia) were coated with RSV F protein (Sino Biological, China) diluted in carbonate buffer (pH 9.6). They were then used to coat 96-well enzyme immunoassay/radioimmunoassay plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) overnight at 4°C. The plates were then blocked with 10% goat serum in PBS for 2 h at 37°C. After blocking, a serially diluted mouse serum was added, and plates were then incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Subsequently, a goat anti-mouse IgG horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody was added, and the plates were incubated for another 1 h at 37°C. The immune reaction was developed using a tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate-based assay. The reaction was stopped with 2M H

2SO

4 and measured at 450 nm using a plate reader (Multiskan MK3). Values that were 2.1-fold higher than those of the control group were considered positive. For IgG antibody subtyping, the antigen was coated overnight at 4°C as described above. After blocking, mouse serum was added in serial dilutions and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Secondary antibodies, biotinylated anti-mouse IgG1 (mAb MG1) and IgG2a (mAb MG2a) (MABTECH, Sweden), were applied 1 h. Streptavidin-HRP was then added, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Colour development, termination, and microplate reader measurement were performed as described above.

2.7. RSV neutralisation assays

Serial dilutions of heat-inactivated sera were mixed with cell culture medium containing RSV—strain A2, B18537, or clinical isolate hRSV/C-Tan/BJ 202301—and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The mixture was then transferred to a HEp-2 cell monolayer in a 96-well plate and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. After removing the mixture, methylcellulose overlay was added, and the plate was incubated at 37°C for 48 h. The plates were then treated with anti-RSV G protein monoclonal antibody (Vazyme, China). Fluorescent labelled viral foci were enumerated using a CTL Immunospot Analyser (Cellular Technology Ltd, USA). NT50 was calculated as the reciprocal serum dilution at which 50% of the virus was neutralised compared to those of the control wells without serum.

2.8. Enzyme-Linked Immunospot Assay (ELISPOT)

Two weeks after the booster immunisation, mice from each group were randomly selected and sacrificed. Spleens were harvested for IFN-γ ELISPOT analysis, as previously described [

17]. Briefly, 96-well ELISPOT plates were coated overnight at 4°C with purified anti-mouse IFN-γ capture antibody (BD ELISPOT Set, USA). The following day, splenocyte suspensions from each group were stimulated with RSV F peptides (KYKSAVTEL, TYMLTNSEL, and GWYTSVITIELSNIK) [

18,

19]or ConA (positive control) in the presence of a positive control. The plates were then incubated at 37°C in 5% CO

2 for 20–24 h. The subsequent steps were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A spot-forming unit (SFU) was used to represent IFN-γ-secreting T cells. The plates were analysed using an ELISpot plate reader (Biosys, So. Pasadena, CA).

2.9. Intracellular cytokine staining (ICS)

RSV F peptides and splenocyte suspensions were added to the flow tube, and cytokine production by memory T cells was evaluated through surface and intracellular cytokine staining using a Fixation/Permeabilisation Solution kit (BD Biosciences, USA). Fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies used for surface staining included PerCP-Cy™5.5 Hamster Anti-Mouse CD3e, BV510 Rat Anti-Mouse CD4, FITC Rat Anti-Mouse CD8a, BV421 Rat Anti-Mouse IFN-γ, PE-Cy™7 Rat Anti-Mouse TNF, PE Rat Anti-Mouse IL-2, and APC Rat Anti-Mouse IL-4. The frequency of F protein-specific T cells was determined using FACS II and analyzed using FlowJo software (version 10.8.1).

2.10. Challenge experiment

At 20 weeks after the booster immunisation, the mice were challenged with 2 × 10

6 a of RSV A2 in 50 μL via intranasal infection. Lung tissues were collected at 4 dpi (

Figure 1D). Half of the tissues were used to determine viral load and RNA copy number as previously described [

20]. The other half was fixed in a 4% formalin solution and sent to Beijing Zhongkewanbang Biotechnology Ltd. to prepare haematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections and subsequent pathological evaluation.

2.11. Statistical analysis

The Unpaired non-parametric Mann–Whitney test was used to compare values between the two groups. One-way ANOVA was used to compare values between more than two groups. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA). Asterisks in the figures indicate the level of statistical significance (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001).

3. Results

3.1. Characterisation of RSV pre-F LPP-mRNA vaccines

Figure 1A illustrates the structure of the RSV pre-F. HEK-293T cells were transfected with RSV pre-F-mRNA, and the expression of the F protein was verified via western blotting (

Figure 1B). The relative molecular weight of the F protein was approximately 56.7 kDa. Target bands were observed at the corresponding positions. Moreover, F protein expression in mRNA vaccines was detected by immunofluorescence in HEK-293T cells transfected with the RSV pre-F mRNA (

Figure 1C).

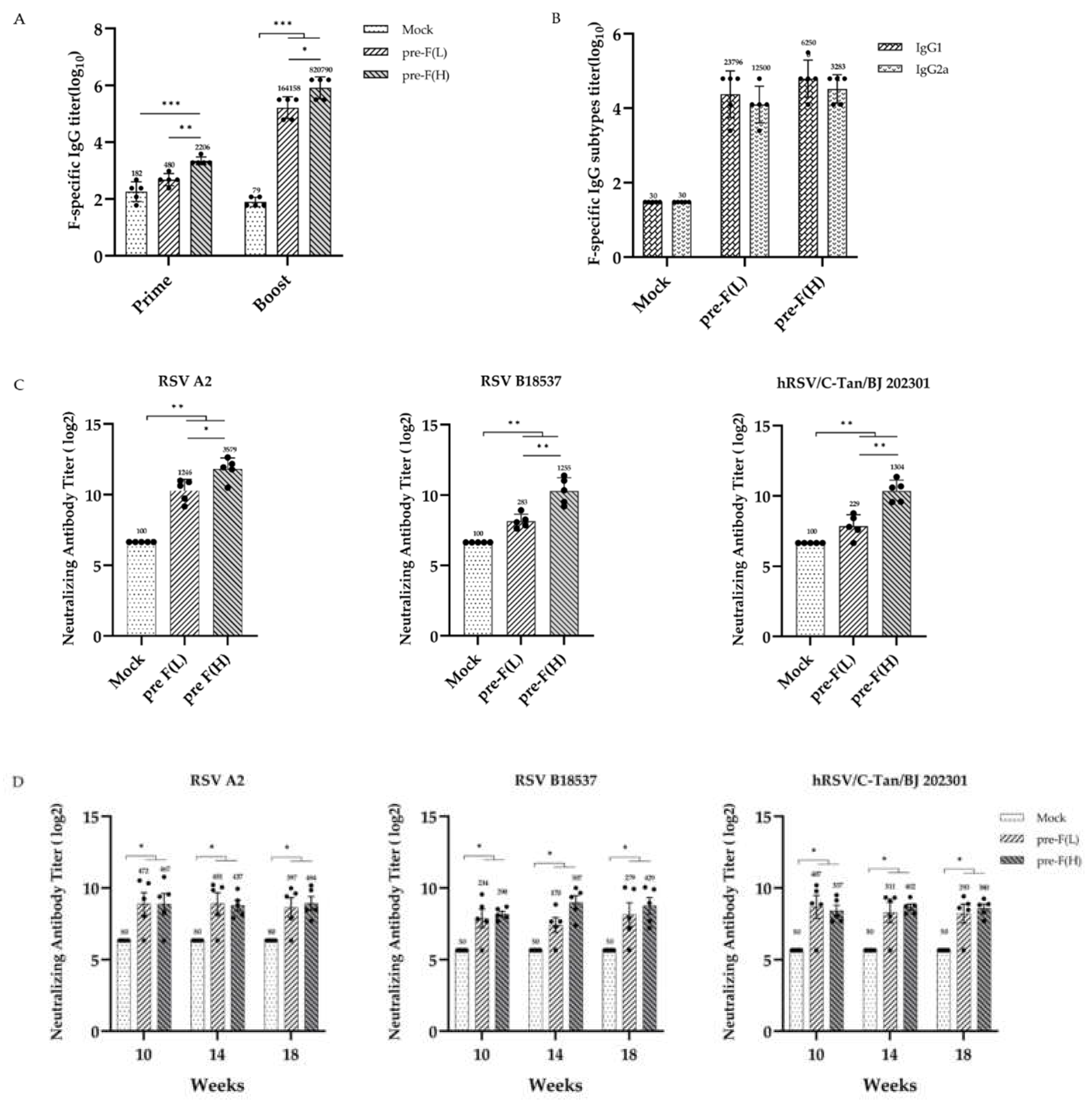

3.2. Significant and Sustained Humoral Immunity Responses Induced by RSV pre-F LPP-mRNA

Immunisation and challenge schema in mice for the RSV pre-F LPP-mRNA vaccines is illustrated in

Figure 1D. The serum of the mice was collected at 2, 6, 10, 14, and 18 weeks post-initial immunisation for humoral immune response detection. The results showed that certain levels of F-specific IgG antibodies were detected in the vaccinated group as early as 2 weeks after the initial immunisation. The IgG levels in the high-dose group were significantly higher than those in the control group. The booster immunisation significantly increased the IgG levels in all immune groups, with the levels significantly higher than those in the control group (

Figure 2A,left). Additionally, we measured the levels of specific IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies in the serum of mice 2 weeks after the booster immunisation. The IgG1 antibody titre induced by all immune groups was slightly lower than those of IgG2a; however, no significant difference was observed between the groups (

Figure 2B). These findings suggest that pre-F LPP-mRNA vaccines induce a more balanced Th1/Th2 immune response.

To evaluate the neutralisation activity in mice. Following booster immunisation, sera from mice were detected by neutralisation assays using different RSV strains. The data shown that both the high- and low-dose immunisation groups produced high levels of neutralising antibodies against two subgroups of RSV strains (A2, B18537 strains) (

p < 0.01). Furthermore, high levels of neutralising antibodies were also produced against the clinical isolates hRSV/C-Tan/BJ 202301, which belong to subgroup ON1 and currently prevalent in China, indicating that pre-F LPP-mRNA vaccine provides extensive protection against different RSV strains (

Figure 2C).

To further evaluate the long-lasting humoral response, serum neutralisation activity against different RSV strains was detected in mice at weeks 10,14 and 18 after the vaccination. Neutralising antibodies titres in each immunised group decreased but remained significantly higher than those in the control group (

p < 0.001) from weeks 10 to 18, with no significant difference observed between two different doses of immunisation groups (

Figure 2D). These findings indicate that the 2 μg dose of pre-F LPP-mRNA is sufficient to elicit a robust and long-lasting humoral immune response.

Moreover, we investigated the dose dependence of the vaccine. At 2 weeks following the prime and booster immunisations, The higher dose of mRNA induced significantly higher levels of IgG antibodies than lower dose, with a dose-dependent effect (

Figure 2A). The pre-F (H) also demonstrated significantly higher levels of neutralising antibodies against various strains 2 weeks after the boost (

Figure 2C). However, strong neutralising antibody levels were maintained in mice with pre-F LPP-mRNA at weeks 10–18 after the vaccination. Collectively, these findings suggest that pre-F LPP-mRNA induces a potent humoral immune response in mice.

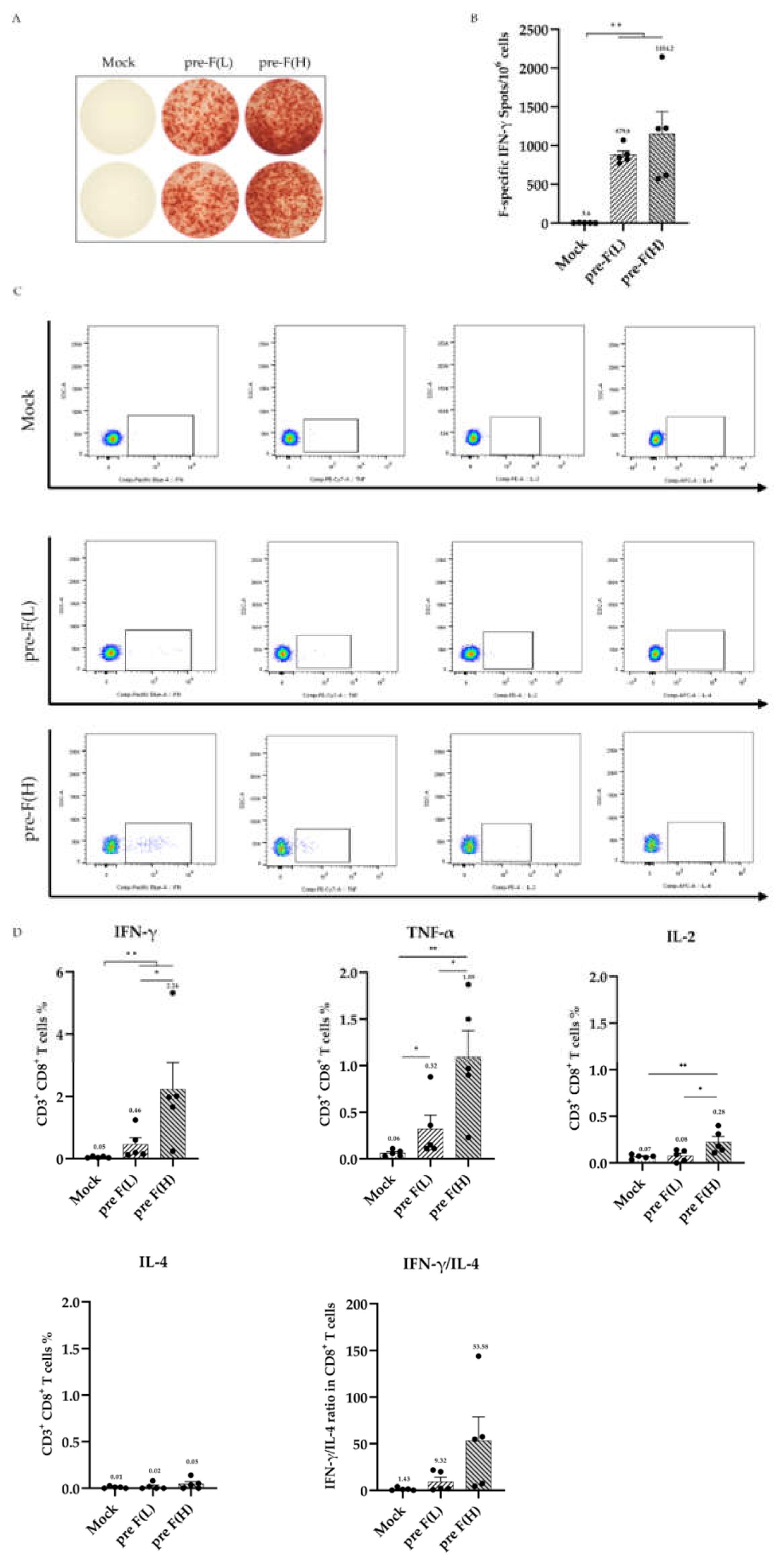

3.3. RSV pre-F LPP-mRNA Elicits Significant F-Specific T-Cell Responses

To evaluate the T-cell responses induced by pre-F LPP-mRNA vaccine in mice, splenocytes from vaccinated mice were stimulated with F-specific peptides, and an ELISpot assay was performed to quantify the number of F-specific T cells. Following the booster immunisation, high- and low-dose mRNA vaccine groups showed significantly higher levels of IFN-γ secretion than the control. While the number of IFN-γ secreting T cells in the RSV pre-F(L) was lower than that in the RSV pre-F (H), this difference was not significant (

Figure 3A, B). The 2 μg dose of pre-F LPP-mRNA is sufficient to induce high levels of F-specific T-cell immune responses in mice.

The T-cell response was further evaluated using an intracellular cytokine staining assay(ICS). The results showed that after the booster immunisation, all immune groups induced significantly higher levels of CD8

+ T cells that predominantly secreted Th1-type cytokines, including IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α, with no secretion of the Th2-type cytokine IL-4. The levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α secreted by CD8

+T cells in the RSV pre-F (H) were significantly higher than those in other groups. Additionally, high-dose immunity induced stronger cytokine secretion in CD8

+ T-cell, shown a dose dependence effect (

Figure 3C, D). However, none significant level of cytokine secretion was detected by ICS in CD4

+ T-cell from immunized mice(Supplemental

Figure 1). These findings suggest that pre-F LPP-mRNA vaccination induces a specific and effective CD8

+ T-cell immune response in mice.

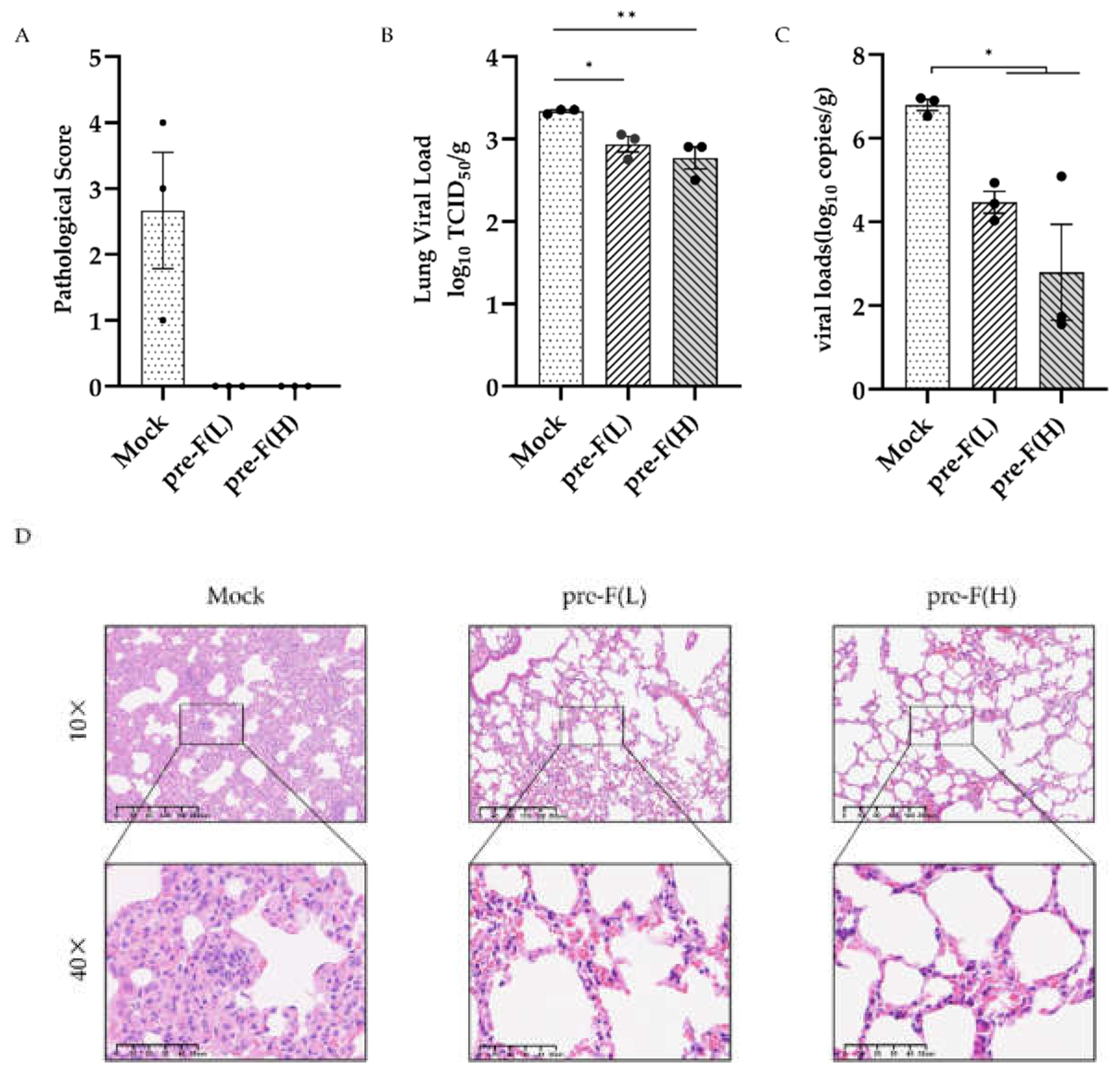

3.4. RSV Pre-F LPP-mRNA Induced Long-Lasting Protection Against RSV Infection in Mice

Given that vaccine immunisation induces a strong and long-lasting immune response in mice, we further explored the protective effect of the pre-F LPP-mRNA vaccine against RSV infection. At 24 weeks post-vaccination, the mice were challenged with (RSV A2, 2 × 10

6 PFU/piece), and their lungs were collected for analysis 4 days after RSV exposure. The pathological score of lung inury showed that the pre-F LPP-mRNA immunised group had significantly better lung pathology than those in the mock group (

Figure 4A). Additionally, mice in the control groups showed significantly higher viral loads in the lungs than those in pre-F LPP mRNA immunised groups (

Figure 4B). Viral copy numbers using real-time RT-PCR showed similar results, with higher levels of viral copies detected in the mock group (

Figure 4C).

Histopathology examination of the lung tissue from mice showed degeneration, necrosis, and detachment of alveolar epithelial cells, along with nuclear fragmentation (

Figure 4D). Additionally, many lymphocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, and other inflammatory cells infiltrated alveolar cavities and widened the interstitial space. The control group showed significant proliferation of type II alveolar epithelial cells. By contrast, the pre-F LPP-mRNA-immunised mice exhibited normal alveolar epithelial morphology, with intact connections between adjacent flat epithelial cells. The bronchiole intima was intact, with no exudates observed in the alveoli or bronchiole lumen.

4. Discussion

Recently, RSV mRNA vaccine based on LNP-delivered platform was also approved by the FDA for protecting adults aged ≥ 60 years [

5]. However, more safety and potent mRNA platform and candidates is still need to be explored. In this study, a novel LPP-mRNA vaccine expressing RSV pre-F protein (RSV pre-F LPP-mRNA) was constructed. This vaccine induced specific humoral immune responses and T-cell immune responses against RSV F protein in mice, as well as significantly enhanced cytokine secretion in CD8

+ T cells. The humoral immunity generated by this vaccine showed broad-spectrum neutralizing activity and high persistence, while mice remained protected against RSV A2 infection 24 weeks after the initial immunisation.

High levels of neutralising antibodies are associated with protection against severe RSV disease. Moreover, their levels are inversely correlated with the risk of RSV reinfection [

21,

22,

23]. Therefore, an ideal RSV vaccine should induce high levels of neutralising antibodies. The pre-F as the vaccine antigen can produce relatively higher levels of neutralising antibodies, which are expected to provide potent protection. In this study, high levels of protective neutralising antibodies against RSV laboratory-adapted strains (A2 and B18537) were induced in all immunised mice after the boost. However, since these laboratory strains were isolated before 1970 and cultured in successive laboratory passages, they may not accurately reflect the immune response and genetic composition of the current RSV epidemic strains [

24]. Therefore, we examined the neutralising effect of mouse serum post-boost immunisation against a clinical isolate of hRSV/C-Tan/BJ 202301. The results showed that the high- and low-dose vaccine immunisation groups produced neutralising antibodies against the clinical isolates, and the high-dose immunisation group produced more significant neutralising activity.

However, neutralising antibodies alone may not provide sufficient protection against RSV disease or reinfection in some individuals, nor do they offer universal durable immune protection [

25]. CD8

+ T cells play a crucial role in viral clearance by secreting cytokines, directly interacting with infected cells, and modulating immune responses to prevent excessive tissue damage [

26,

27,

28]. In mouse models, depletion of CD8

+ T cells in RSV-infected mice resulted in delays in viral clearance compared to that of control mice, while the transfer of CD8

+ T cells from previously RSV-infected mice to naïve mice reduced weight loss and viral load after RSV infection [

27]. The results of this study showed that the high-dose and low-dose vaccine groups induced the production of IFN-γ-secreting T cells, thereby significantly enhancing cellular immunity. Additionally, ICS were used to assess cytokine secretion by specific CD8

+ T cells in mouse lymphocytes following peptide stimulation. The results showed that CD8

+ T cells mainly secreted IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α, indicating that the vaccine induces a Th1-biased immune response. This Th1-shewed response reduces the possibility of a Th2-biased immune reaction, leading to more severe disease and immunopathology [

29].

RSV causes seasonal outbreaks globally, typically occurring from November to April in the Northern Hemisphere and from March to October in the Southern Hemisphere [

30]. By contrast, the antibody response generated by natural RSV infection is short-lived. Healthy adults can be repeatedly infected with the same RSV strain for 2 months, with a 25% risk of reinfection even among those with the highest antibody levels [

25]. Therefore, a vaccine that induces long-lasting immunity may provide effective protection throughout the RSV epidemic season. However, studies on the long-lasting protective effects of RSV vaccines remain limited. Therefore, we investigated the long-lasting immune effect of high- and low-dose LPP-mRNA vaccines. The results showed that the humoral immunity induced by the LPP-mRNA vaccine remained stable

in vivo for a long time, exhibiting strong neutralising activity against RSV strains A, B, and clinical isolates. Following the challenge, the immune group continued to effectively inhibit RSV replication in the lungs and reduce pathological injury to the lungs. Furthermore, the low-dose group also provided effective protection against RSV challenge at least 24 weeks after vaccination. This protection may be attributed to the high levels of neutralising antibodies induced in the low-dose group over the long-term immunisation process compared to those observed in the high-dose group.

This study had some limitations, including that only the RSV A strain was tested, and the protective effect of the vaccine can be more comprehensively evaluated by challenging with more RSV A and B strains in subsequent experiments; in addition, the vaccine effect was evaluated only in the mouse model, and further studies can be conducted with more sensitive animal models (cotton rats, African green monkeys, etc.).

In conclusion, the prepared LPP-mRNA vaccine expressing RSV pre-F protein induced robust and long-lasting immunity and protection in mice. Even at low doses, the vaccine effectively protected mice against the RSV A2 challenge, significantly inhibiting viral replication and reducing lung tissue pathological damage. The findings provide a scientific foundation for further development and application of this novel RSV mRNA vaccine.

Author Contributions

W.T., D.Z., and Y.D. conceived of the study. X.S., R.H., X.C., J.B., Z.Q., S.S., T.W., and Q.C. performed the experiment. X.S. analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. D.Z. and W.T. revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC2304101 to W.T.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal testing experiments and research were conducted with the relevant ethical regulations, and the study was approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC) (protocol code 20231128092, approved 28 November 2023).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Wei Zhang and Dr. Hangwen Li of Shanghai Stemirna Therapeutics for their help and guidance in the preparation of the LPP-mRNA vaccine.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, Y., X.; Wang, D.M.; Blau, M.T.; Caballero, D.R.; Feikin, C.J.; Gill, S.A.; Madhi, S.B.; Omer, E.A.F.; Simões, H.; et al. Zar, Network Respiratory Virus Global Epidemiology, H. Nair, and Resceu investigators. "Global, Regional, and National Disease Burden Estimates of Acute Lower Respiratory Infections Due to Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Children Younger Than 5 Years in 2019: A Systematic Analysis." Lancet 399, no. 10340 (2022): 2047-64.

- Ruckwardt, T.J., K.M. Morabito, and B. S. Graham. "Immunological Lessons from Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccine Development." Immunity 51, no. 3 (2019): 429-42.

- Awosika, A.O., and P. Patel. "Respiratory Syncytial Virus Prefusion F (Rsvpref3) Vaccine." In Statpearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Preeti Patel declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.: StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC., 2023.

- Fleming-Dutra, K.E., J.M. Jones, L.E. Roper, M.M. Prill, I.R. Ortega-Sanchez, D.L. Moulia, M. Wallace, M. Godfrey, K.R. Broder, N.K. ; et al. "Use of the Pfizer Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccine During Pregnancy for the Prevention of Respiratory Syncytial Virus-Associated Lower Respiratory Tract Disease in Infants: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices - United States, 2023." MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 72, no. 41 (2023): 1115-22.

- Mullard, A. "Fda Approves Mrna-Based Rsv Vaccine." Nat Rev Drug Discov (2024).

- Magro, M., V. Mas, K. Chappell, M. Vázquez, O. Cano, D. Luque, M.C. Terrón, J.A. Melero, and C. Palomo. "Neutralizing Antibodies against the Preactive Form of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Fusion Protein Offer Unique Possibilities for Clinical Intervention." Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, no. 8 (2012): 3089-94.

- Graham, B.S. "Vaccine Development for Respiratory Syncytial Virus." Curr Opin Virol 23 (2017): 107-12.

- Ngwuta, J.O., M. Chen, K. Modjarrad, M.G. Joyce, M. Kanekiyo, A. Kumar, H.M. Yassine, S.M. Moin, A.M. Killikelly, G.Y. ; et al. "Prefusion F-Specific Antibodies Determine the Magnitude of Rsv Neutralizing Activity in Human Sera." Sci Transl Med 7, no. 309 (2015): 309ra162.

- Chaudhary, N., D. Weissman, and K. A. Whitehead. "Mrna Vaccines for Infectious Diseases: Principles, Delivery and Clinical Translation." Nat Rev Drug Discov 20, no. 11 (2021): 817-38.

- Zhang, G., T. Tang, Y. Chen, X. Huang, and T. Liang. "Mrna Vaccines in Disease Prevention and Treatment." Signal Transduct Target Ther 8, no. 1 (2023): 365.

- Di, J., Z. Du, K. Wu, S. Jin, X. Wang, T. Li, and Y. Xu. "Biodistribution and Non-Linear Gene Expression of Mrna Lnps Affected by Delivery Route and Particle Size." Pharm Res 39, no. 1 (2022): 105-14.

- Yang, R., Y. Deng, B. Huang, L. Huang, A. Lin, Y. Li, W. Wang, J. Liu, S. Lu, Z. ; et al. "A Core-Shell Structured Covid-19 Mrna Vaccine with Favorable Biodistribution Pattern and Promising Immunity." Signal Transduct Target Ther 6, no. 1 (2021): 213.

- Stephens, L.M., and S. M. Varga. "Function and Modulation of Type I Interferons During Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection." Vaccines (Basel) 8, no. 2 (2020).

- Blais, N., M. Gagné, Y. Hamuro, P. Rheault, M. Boyer, A.M. Steff, G. Baudoux, V. Dewar, J. Demers, J.L. Ruelle, and D. Martin. "Characterization of Pre-F-Gcn4t, a Modified Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus Fusion Protein Stabilized in a Noncleaved Prefusion Conformation." J Virol 91, no. 13 (2017).

- Krarup, A., D. Truan, P. Furmanova-Hollenstein, L. Bogaert, P. Bouchier, I.J.M. Bisschop, M.N. Widjojoatmodjo, R. Zahn, H. Schuitemaker, J.S. McLellan, and J. P. M. Langedijk. "A Highly Stable Prefusion Rsv F Vaccine Derived from Structural Analysis of the Fusion Mechanism." Nat Commun 6 (2015): 8143.

- Zhan, Y., Y. Deng, B. Huang, Q. Song, W. Wang, Y. Yang, L. Dai, W. Wang, J. Yan, G.F. Gao, and W. Tan. "Humoral and Cellular Immunity against Both Zikv and Poxvirus Is Elicited by a Two-Dose Regimen Using DNA and Non-Replicating Vaccinia Virus-Based Vaccine Candidates." Vaccine 37, no. 15 (2019): 2122-30.

- Zhao, Z., Y. Deng, P. Niu, J. Song, W. Wang, Y. Du, B. Huang, W. Wang, L. Zhang, P. Zhao, and W. Tan. "Co-Immunization with Chikv Vlp and DNA Vaccines Induces a Promising Humoral Response in Mice." Front Immunol 12 (2021): 655743.

- Huang, L., M.Q. Liu, C.Q. Wan, N.N. Cheng, Y.B. Su, Y.P. Zheng, X.L. Peng, J.M. Yu, Y.H. Fu, and J. S. He. "The Protective Immunity Induced by Intranasally Inoculated Serotype 63 Chimpanzee Adenovirus Vector Expressing Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus Prefusion Fusion Glycoprotein in Balb/C Mice." Front Microbiol 13 (2022): 1041338.

- Levely, M.E., C.A. Bannow, C.W. Smith, and J. A. Nicholas. "Immunodominant T-Cell Epitope on the F Protein of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Recognized by Human Lymphocytes." J Virol 65, no. 7 (1991): 3789-96.

- Han, R., T. Wang, X. Cheng, J. Bing, J. Li, Y. Deng, X. Shan, X. Zhang, D. Wang, S. Sun, and W. Tan. "Immune Responses and Protection Profiles in Mice Induced by Subunit Vaccine Candidates Based on the Extracellular Domain Antigen of Respiratory Syncytial Virus G Protein Combined with Different Adjuvants." Vaccines (Basel) 12, no. 6 (2024).

- Glezen, W.P., A. Paredes, J.E. Allison, L.H. Taber, and A. L. Frank. "Risk of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection for Infants from Low-Income Families in Relationship to Age, Sex, Ethnic Group, and Maternal Antibody Level." J Pediatr 98, no. 5 (1981): 708-15.

- Piedra, P.A., A.M. Jewell, S.G. Cron, R.L. Atmar, and W. P. Glezen. "Correlates of Immunity to Respiratory Syncytial Virus (Rsv) Associated-Hospitalization: Establishment of Minimum Protective Threshold Levels of Serum Neutralizing Antibodies." Vaccine 21, no. 24 (2003): 3479-82.

- Glezen, W.P., L.H. Taber, A.L. Frank, and J. A. Kasel. "Risk of Primary Infection and Reinfection with Respiratory Syncytial Virus." Am J Dis Child 140, no. 6 (1986): 543-6.

- Pandya, M.C., S.M. Callahan, K.G. Savchenko, and C. C. Stobart. "A Contemporary View of Respiratory Syncytial Virus (Rsv) Biology and Strain-Specific Differences." Pathogens 8, no. 2 (2019).

- Hall, C.B., E.E. Walsh, C.E. Long, and K. C. Schnabel. "Immunity to and Frequency of Reinfection with Respiratory Syncytial Virus." J Infect Dis 163, no. 4 (1991): 693-8.

- Cannon, M.J., P.J. Openshaw, and B. A. Askonas. "Cytotoxic T Cells Clear Virus but Augment Lung Pathology in Mice Infected with Respiratory Syncytial Virus." J Exp Med 168, no. 3 (1988): 1163-8.

- Ostler, T., W. Davidson, and S. Ehl. "Virus Clearance and Immunopathology by Cd8(+) T Cells During Infection with Respiratory Syncytial Virus Are Mediated by Ifn-Gamma." Eur J Immunol 32, no. 8 (2002): 2117-23.

- Beňová, K., M. Hancková, K. Koči, M. Kúdelová, and T. Betáková. "T Cells and Their Function in the Immune Response to Viruses." Acta Virol 64, no. 2 (2020): 131-43.

- Agac, A., S.M. Kolbe, M. Ludlow, Adme Osterhaus, R. Meineke, and G. F. Rimmelzwaan. "Host Responses to Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection." Viruses 15, no. 10 (2023).

- Hall, C.B., E.A. Simőes, and L. J. Anderson. "Clinical and Epidemiologic Features of Respiratory Syncytial Virus." Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 372 (2013): 39-57.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).