Introduction

It would be fair to say that immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy has brought about a significant transformation in cancer treatment. ICIs are monoclonal antibodies that have been developed to target regulatory receptors on immune cells, such as programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1), programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1), and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4). It is thought that by binding to these inhibitory receptors, ICIs enable the immune system to recognize and attack cancer cells. There is growing evidence that ICIs may have potential in the treatment of a range of cancers. [

1]. It is possible that immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy may be associated with immune-related adverse events (irAEs). While rare ICIs-induced myocarditis is a serious irAE with a high mortality risk [

2].

While ICI myocarditis typically presents early in the course of immunotherapy, it would be beneficial to further investigate delayed-onset cases (>90 days), as they are linked to a higher risk of major adverse cardiac events [

3].

Despite the high prevalence of ICIs-induced myocarditis, there is currently a paucity of robust evidence to inform the optimal immunosuppressive therapy. The current guidelines are primarily based on expert consensus, and randomized controlled trials evaluating the efficacy of different immunosuppressive strategies are lacking [

4,

5].

This case series is dedicated to an in-depth examination of four cases of late-onset immune myocarditis associated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy and its treatment. Additionally, it presents a comprehensive literature review on the subject.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 56-year-old male patient diagnosed with clear cell renal cell carcinoma was initiated on pembrolizumab and axitinib therapy following the progression of his disease on pazopanib. He had a previous history of atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension.

Six months after the first dose of the combination therapy, the patient presented symptoms of chest tightness and shortness of breath. The physical examination was unremarkable. The electrocardiogram (ECG) showed sinus tachycardia with a heart rate of 150 bpm, and ST-segment depression in leads V4, V5, and V6. Echocardiography showed a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 25% (normal >50%), dilated left ventricle, and biatrial dilatation. Cardiac troponin T (cTnT) level was 7.4 ng/mL (normal <0.014), and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level was 2302 ng/L (normal <125). Coronary angiography showed no significant stenosis. Cardiac MRI was planned to rule out immune-related myocarditis.

Cardiac MRI showed edema and inflammation findings consistent with acute myocarditis, predominantly in the basal, septal, and inferior segments. There was a decrease in left ventricular systolic function (LVEF) 25%, dilated left ventricle, and dilatation in both atria. Secondary etiologies, including viral markers and autoimmune markers, were negative.

Based on the clinical symptoms, elevated biomarkers of myocardial injury, ECG and echocardiographic changes, and characteristic findings on cardiac MRI, a diagnosis of ICI-related myocarditis was made. This was classified as grade-3 according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0. The patient also developed grade 4 immune-related hepatitis. Elevated liver enzymes were noted, with AST at 200 U/L (normal range 0-30 U/L) and ALT at 240 U/L (normal range 0-40 U/L). Cholestatic markers and bilirubin levels were within normal limits. Based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0, this was classified as a grade 3 adverse event. The condition was successfully managed with corticosteroid therapy.

The immunotherapy treatment was permanently discontinued. The patient was treated with methylprednisolone at a dosage of 1mg/kg. Given the absence of a clinical response and the lack of regression in cardiac biomarkers on the third day, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy was initiated at a dose of 1 g/kg for five days, with methylprednisolone continued concurrently. Methylprednisolone was gradually discontinued after the fourth week. A reduction in cardiac biomarkers was noted. Corticosteroid therapy was discontinued at the three-month mark, and a control cardiac MRI demonstrated in LVEF 47%. The left ventricle exhibited hypokinetic segments. Additionally, there were findings suggestive of inflammation and potential fibrosis in the basal inferoseptal and anteroseptal walls, as well as in the mid-inferior segments of the left ventricle. In comparison to the previous examination, the findings demonstrated improvement. Seven months following the diagnosis of myocarditis, the patient succumbed to disease progression.

Case 2

A 78-year-old female patient diagnosed with clear cell renal cell carcinoma was initiated on nivolumab therapy following the progression of her disease interferon-alpha and pazopanib. She had a previous history of atrial fibrillation and hypertension.

At the 12th cycle of nivolumab therapy (corresponding to the sixth months of treatment), the patient exhibited symptoms of bradycardia and weakness. The physical examination yielded no noteworthy findings. The ECG demonstrated sinus bradycardia with a heart rate of 40 beats per minute (bpm) and ST-segment depression in leads D1, aVL, V4, V5, and V6. Echocardiography revealed a LVEF of 15%, moderate aortic regurgitation, and a dilated left ventricle. The level of cTnT was 500 ng/mL, and the level of NT-proBNP was 30000 ng/L. Coronary angiography did not reveal any significant stenosis, and thus, a cardiac MRI was planned.

Cardiac MRI revealed the presence of widespread myocardial edema, moderate aortic regurgitation, and severe impairment of left ventricular function. When viewed in conjunction with the patient's clinical, radiological, and laboratory parameters, these findings were consistent with a diagnosis of myocarditis. Secondary etiologies, including viral and autoimmune markers, were excluded.

A diagnosis of ICI-related myocarditis was made based on the patient’s clinical symptoms, elevated myocardial injury biomarkers, ECG and echocardiographic changes, and characteristic findings on cardiac MRI. The diagnosis was graded as grade-4 according to CTCAE version 5.0.

The immunotherapy was permanently discontinued. The patient was treated with methylprednisolone at a dose of 1mg/kg. A decrease in troponin levels was observed under corticosteroid therapy. However, within the first month of treatment, the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit due to cardiogenic shock and died shortly thereafter.

Case 3

A 64-year-old male patient diagnosed with nasopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma was initiated on nivolumab therapy after progression on carboplatin and gemcitabine. There was no known prior cardiac or non-cardiac comorbidity.

At the 36th cycle of nivolumab therapy (20th month of treatment), the patient exhibited symptoms of bradycardia, weakness, and hypotension. The physical examination yielded no noteworthy findings. An ECG revealed the presence of widespread ventricular extrasystoles (VES) and sinus bradycardia. Twenty-four-hour Holter monitoring revealed a total of 5,000 ventricular extrasystoles and an average heart rate of 45 beats per minute. No instances of ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation were observed, nor were there any pauses exceeding three seconds. Echocardiography demonstrated a LVEF of 60% and moderate aortic regurgitation. The level of cTnT was 0.5 ng/mL, while the level of NT-proBNP was 1200 ng/L. Secondary causes of hypotension (infection, pituitary and adrenal diseases, etc.) were excluded. Coronary angiography did not identify any significant stenosis. A cardiac MRI was scheduled.

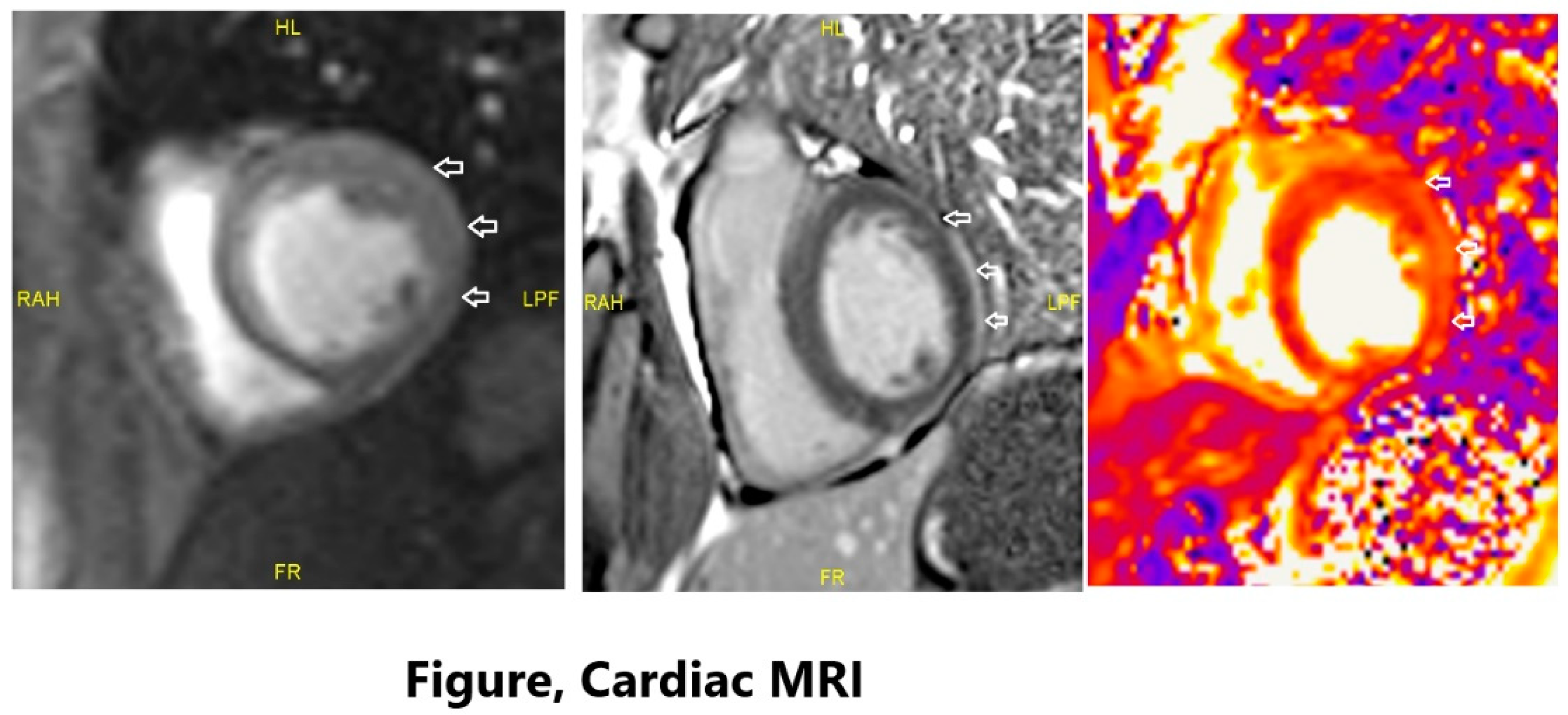

Cardiac MRI revealed subepicardial linear contrast enhancement in the lateral wall of the left ventricle. When evaluated with T2 mapping images, the findings were predominantly consistent with a diagnosis of myocarditis, particularly considering the clinical findings. Moderate aortic regurgitation was observed. Secondary etiologies, including viral markers and autoimmune markers, were excluded as a cause (

Figure 1).

A diagnosis of ICI-related myocarditis was made based on the patient’s clinical symptoms, elevated myocardial injury biomarkers, ECG and echocardiographic changes, and characteristic findings on cardiac MRI. The diagnosis was graded as grade-4 according to CTCAE version 5.0.

The immunotherapy treatment was permanently discontinued. The patient was treated with methylprednisolone 1000mg (pulse steroid) for a period of three days, followed by a dose of 1mg/kg/day. Due to the presence of hypotension, noradrenaline was introduced as an inotropic agent to provide support. Despite inotropic support, the patient's bradycardia and hypotension remained unimproved, thus prompting the initiation of mycophenolate mofetil treatment at a dosage of 2x1g, while corticosteroid therapy was maintained. In the second week of combined immunosuppressive therapy, a reduction in cardiac biomarkers and an improvement in hypotension and bradycardia were observed. Mycophenolate therapy was terminated after one month, and corticosteroid therapy was gradually discontinued and ultimately terminated after two months. A cardiac MRI performed in the second month of treatment yielded normal results. The findings observed in the previous MRI and considered indicative of myocarditis were absent in the current examination. The patient succumbed to the disease six months after the diagnosis of myocarditis.

Case 4

A 74-year-old male patient diagnosed with lung squamous cell carcinoma was initiated on first-line treatment with carboplatin, paclitaxel, and pembrolizumab. He had a known history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension.

At the 11th cycle of nivolumab therapy (6th month of treatment), the patient exhibited symptoms of tachycardia, weakness, and shortness of breath. The physical examination yielded no noteworthy findings. An ECG demonstrated sinus tachycardia and new onset of ventricular extrasystoles (VES). Twenty-four-hour holter monitoring revealed a total of 2,000 ventricular extrasystole and an average heart rate of 130 beats per minute. No instances of ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, or supraventricular tachycardia were not observed. Echocardiography demonstrated a LVEF of 60%. The level of cTnT level was 0.001 ng/mL. Similarly, the level of NT-proBNP was 800 ng/L. Cardiac MRI revealed the presence of late subepicardial linear contrast enhancement in the lateral wall of the basal segment of the left ventricle. Secondary etiologies, including viral markers and autoimmune markers, were excluded.

A diagnosis of ICI-related myocarditis was made based on the clinical symptoms, elevated myocardial injury biomarkers, ECG and echocardiographic changes, and characteristic findings on cardiac MRI. This was classified as grade-2 according to CTCAE version 5.0. Prior to the onset of immune myocarditis, the patient had also developed grade-2 immune pneumonitis and grade-1 immune thyroiditis. Once immune-related pneumonitis had been reduced to grade 1 with methylprednisolone and thyroiditis controlled with levothyroxine replacement, immunotherapy was started.

The immunotherapy treatment was permanently discontinued. The patient administered methylprednisolone at a dosage of 1mg/kg. The patient exhibited an improvement in tachycardia from the third day of methylprednisolone administration. Methylprednisolone was gradually discontinued after the fourth week. A reduction in cardiac biomarkers was noted. Corticosteroid therapy was discontinued after a two-month period, and a control cardiac MRI demonstrated stable T1 mapping values measured from the interventricular septum and late contrast enhancement patterns in the inferolateral wall. No progress was observed. The patient is currently under observation without the use of any medication and is undergoing active monitoring for any potential cancer developments. A summary of the cases is shown in the

Table 1 below.

Discussion

Although ICIs have revolutionized cancer therapy, the resulting hyperactivated immune response can trigger autoimmune disorders, such as fulminant ICI myocarditis. While rare, ICI myocarditis has a high mortality rate, estimated at 40-50% of cases. The prevalence of ICI myocarditis is approximately 1.14% of patients, but this number is increasing due to greater clinical awareness [

6,

7].

ICI myocarditis typically manifests during the early stages of treatment, frequently within the initial 90 days. The median onset time is around 34 days, typically occurring after the first or third infusion. While many cases manifest within this timeframe, the latest reported case occurred approximately 500 days following the initiation of treatment. The occurrence of delayed immune-related adverse events (irAEs) following the cessation of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy is becoming increasingly recognized in medical literature. In the case of cardiac irAEs, these delayed events have been linked to an increased incidence of left ventricular systolic dysfunction and heart failure, underscoring the necessity for prompt detection and diagnosis [

3,

8,

9].

A few hypotheses have been proposed to explain the pathophysiology of ICI myocarditis. One hypothesis posits that T cells may be targeting cardiac-specific antigens or shared antigens between tumors and the heart. The existence of shared antigens has been demonstrated through the sequencing of T-cell receptor CDR3 regions, which revealed similarities between tumor and cardiac/skeletal muscle sequences. While further mechanistic studies are required, it is plausible that neoantigens, which enhance tumor immunogenicity, may also cross-react with the myocardium, thereby stimulating a profound autoimmune response. The continuous creation of neoantigens due to defective DNA repair may sustain prolonged T-cell stimulation, potentially leading to late-onset autoimmunity. A comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms underlying ICI myocarditis is of paramount importance for the accurate long-term risk stratification of patients and the development of effective therapeutic strategies. In patients who achieve tumor control with immunotherapy, the recognition of late-onset ICI myocarditis is of paramount importance. Furthermore, the role of extended vigilance for irAEs requires further investigation [

10,

11].

The occurrence of subclinical myocarditis following immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy represents a novel phenomenon, and the natural history of this condition remains uncertain. There are similarities between this phenomenon and chronic viral myocarditis, which often involves lymphocytic inflammation and autoimmunity. An initial viral infection can trigger the recognition of self-antigens, leading to the development of persistent anti-cardiac antibodies and inflammation despite the clearance of the virus. Myocardial fibrosis, which frequently co-localizes with inflammation, contributes to the development of chronic dilated cardiomyopathy and ventricular arrhythmias [

12,

13,

14].

A diagnosis of immune myocarditis was made in three of our patients at the 6-month follow-up after treatment, and in one patient at the 20-month follow-up. What was most striking was that all four cases occurred late.

Patients with comorbidities, such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiac disease, have been shown in the literature to have an elevated risk of developing immune-mediated myocarditis. Moreover, the risk associated with combination immunotherapies has been found to be greater than that of monotherapy [

3]. Our case series did not involve the use of combination immunotherapy. Nevertheless, three patients exhibited one or more comorbidities, namely diabetes, hypertension, and cardiac disease. Considering the elevated risk of immune-mediated myocarditis in patients with severe comorbidities undergoing combination immunotherapy, close cardiac monitoring is crucial.

Immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI)-induced myocarditis is a serious adverse event that can present with a wide range of clinical manifestations. Common symptoms include shortness of breath, hypotension, palpitations, chest pain, heart failure, fatigue, weakness, and myalgia. This delayed presentation may reflect ongoing inflammation and cardiac remodelling. The predominant presenting symptoms are shortness of breath (prevalence: 55-68%), palpitations (5-33%), and chest pain (13-28%). A higher incidence of LV systolic dysfunction (37-74%) is observed in late-onset cases, which may account for the increased prevalence of heart failure symptoms. Patients may also experience non-specific symptoms such as fatigue or weakness [

3,

8,

15]. Myocarditis should be considered as a differential diagnosis, even in cases with non-specific symptoms. Moreover, it may be incidentally detected during routine troponin surveillance [

9]. In our patient’s cardiac troponin levels were elevated in three patients, while it was within the normal range in one patient.

The Society of Immunotherapy in Cancer (SITC), European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO), and the recent European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines recommend obtaining baseline basic cardiac biomarkers such as troponin I, BNP, ECG prior to ICI start to develop an accurate baseline for comparison, whereas American Society of Clinical oncology (ASCO) guidelines do not; stating “there is no clear evidence regarding the efficacy or value of routine ECGs or troponin measurements in patients receiving checkpoint inhibitor therapy [

16,

17,

18].

ICI-induced myocarditis can be challenging to diagnose due to its varying symptoms and lack of specific biomarkers. A combination of clinical, laboratory, and imaging tests is often necessary for accurate diagnosis.

Cardiac biomarkers like troponin and BNP can be elevated but are not always specific. ECG may show abnormalities, while echocardiography can reveal reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. Cardiac MRI is considered the gold standard for non-invasive diagnosis, with LGE(late gadolinium enhancement) and T1/T2 mapping providing valuable information. PET has a limited role, but 68Ga-DOTATOC PET shows promise. Endomyocardial biopsy is invasive and may be considered in severe cases or when non-invasive tests are inconclusive.

The ESC guidelines recommend a combination of clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings for diagnosis, and the Bonaca criteria can be used to assess the probability of ICI myocarditis [

19,

20,

21].

The initial step in managing suspected immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI)-induced myocarditis is to immediately halt ICI therapy while conducting diagnostic tests. This approach is endorsed by all major medical societies [

16].

Corticosteroids are the first-line treatment for immune-related adverse events, including myocarditis. Guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) recommend initiating high-dose corticosteroids (e.g., methylprednisolone) for the first few days, followed by a gradual reduction in dosage. The Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) also recommend high-dose corticosteroids for confirmed or highly suspected myocarditis.

In cases where corticosteroids are insufficient, additional therapies may be considered, including IVIG, tocilizumab, alemtuzumab, anti-thymocyte immunoglobulin, mycophenolate mofetil, and abatacept. Recent studies have shown promising results with a combination therapy involving low-dose steroids, abatacept, and ruxolitinib in severe cases of ICI-induced myocarditis [

17,

18,

22].

Our cases illustrate the significance of recognizing that ICI myocarditis can manifest as a delayed irAE. These cases underscore the importance of awareness, developing early clinical suspicion, and rapid detection of delayed-onset ICI myocarditis to prevent decompensation and the development of fulminant myocarditis. As the indications for immunotherapy continue to expand, the ability to recognize delayed-onset ICI myocarditis will become increasingly crucial as life expectancy after cancer treatment continues to improve.

In all cases methylprednisolone was administered, while one patient received IVIG, and another received mycophenolate mofetil in addition. Three patients were treated with methylprednisolone at a dosage of 1mg/kg. In one patient, the initial dose was 1000 mg of methylprednisolone for three days, followed by a maintenance dose of 1mg/kg. The high-dose methylprednisolone regimen was continued for a minimum of one month and was tapered based on the patient's response. Mycophenolate mofetil was initiated at a dose of 2x1000mg for one month in a patient who did not respond to three days of methylprednisolone. IVIG was administered at a dose of 5g/kg for five days in one patient. Considering the patient's rapidly deteriorating cardiac condition and the established role of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) in the management of similar cases, we opted for immediate IVIG administration. The patient exhibited a prompt clinical improvement following this intervention.

The occurrence of immune myocarditis-related death was observed in only one of the four patients who developed ICI-induced myocarditis. Two patients died because of disease progression and one patient remains alive. To the best of our knowledge, the latest case of immune myocarditis was previously reported to have developed on the 500th day. One of our cases developed immune myocarditis on the 600th day after the initiation of immunotherapy, which we believe to be the latest case reported in the literature

Conclusion

The advent of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy has markedly enhanced the efficacy of cancer treatment. However, it is associated with a range of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), including myocarditis. Although early-onset ICI myocarditis is well-documented, late-onset cases have recently been reported, emphasizing the necessity for long-term surveillance.

Our case series highlights the necessity for enhanced awareness of late-onset ICI myocarditis, which can manifest with a range of clinical presentations, from subtle symptoms to life-threatening cardiac complications. An early diagnosis and prompt initiation of immunosuppressive therapy are of paramount importance for improving patient outcomes.

Previous studies have consistently demonstrated that cardiotoxicity associated with checkpoint inhibitors typically presents with an early onset, shortly following infusion [

10,

23,

24,

25]. However, our cohort of patients with immune myocarditis exhibited a late-onset phenotype, which deviates from the established literature [

26,

27].

As the use of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy continues to expand, it is imperative to recognize the risk of late-onset ICI myocarditis and to implement strategies for early detection and intervention. Doing so will improve the safety and efficacy of this transformative cancer treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.M., B.K, E.S.; methodology, H.M., B.K, E.S software, H.M., B.K, E.S.; validation, H.M., B.K, E.S formal analysis, O.F.O, A.B, F.S.; investigation, H.M.; resources, H.M.; data curation, H.M., B.K, E.S, D.T, C.E, O.F.O, A.B, F.S .; writing—original draft preparation, H.M.; writing—review and editing, H.M.; visualization, H.M.; supervision, O.F.O.; project administration, A.B, H.M.; funding acquisition:no funding. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Istanbul Medipol University Faculty of Medicine (Document no: E-10840098-202.3.02-7645, Decision No: 1210, Date: 28.11.2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hargadon, K.M., C.E. Johnson, and C.J. Williams, Immune checkpoint blockade therapy for cancer: an overview of FDA-approved immune checkpoint inhibitors. International immunopharmacology, 2018. 62: p. 29-39. [CrossRef]

- Salem, J.-E., et al., Cardiovascular toxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: an observational, retrospective, pharmacovigilance study. The Lancet Oncology, 2018. 19(12): p. 1579-1589. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, S.S., et al., Myocarditis in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 2018. 71(16): p. 1755-1764. [CrossRef]

- Brahmer, J.R., et al., Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2018. 36(17): p. 1714-1768. [CrossRef]

- Ponikowski, P., et al., 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Russian journal of cardiology, 2017(1): p. 7-81. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.Y., et al., Fatal toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA oncology, 2018. 4(12): p. 1721-1728. [CrossRef]

- Moslehi, J.J., et al., Increased reporting of fatal immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated myocarditis. The Lancet, 2018. 391(10124): p. 933. [CrossRef]

- Dolladille, C., et al., Late cardiac adverse events in patients with cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer, 2020. 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Waliany, S., et al., Myocarditis surveillance with high-sensitivity troponin I during cancer treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cardio Oncology, 2021. 3(1): p. 137-139. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.B., et al., Fulminant myocarditis with combination immune checkpoint blockade. New England Journal of Medicine, 2016. 375(18): p. 1749-1755. [CrossRef]

- Sahin, I.H., et al., Immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of MSI-H/MMR-D colorectal cancer and a perspective on resistance mechanisms. British journal of cancer, 2019. 121(10): p. 809-818. [CrossRef]

- Disertori, M., M. Masè, and F. Ravelli, Myocardial fibrosis predicts ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Trends in cardiovascular medicine, 2017. 27(5): p. 363-372. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, L.T., et al., others. 2007. The role of endomyocardial biopsy in the management of cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the European Society of Cardiology. Endorsed by the Heart Failure Society of America and the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 50(19): p. 1914-1931. [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, T., et al., Autoantibodies against cardiac troponin I are responsible for dilated cardiomyopathy in PD-1-deficient mice. Nature medicine, 2003. 9(12): p. 1477-1483. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., et al., Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated myocarditis. European heart journal, 2020. 41(18): p. 1733-1743. [CrossRef]

- Puzanov, I., et al., Managing toxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: consensus recommendations from the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) Toxicity Management Working Group. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer, 2017. 5: p. 1-28. [CrossRef]

- Haanen, J., et al., Management of toxicities from immunotherapy: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up☆. Annals of Oncology, 2022. 33(12): p. 1217-1238. [CrossRef]

- Lyon, A.R., et al., 2022 ESC Guidelines on cardio-oncology developed in collaboration with the European Hematology Association (EHA), the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ESTRO) and the International Cardio-Oncology Society (IC-OS) Developed by the task force on cardio-oncology of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European Heart Journal-Cardiovascular Imaging, 2022. 23(10): p. e333-e465.

- Boughdad, S., et al., 68Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT to detect immune checkpoint inhibitor-related myocarditis. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer, 2021. 9(10). [CrossRef]

- Seferović, P.M., et al., Heart failure association of the ESC, heart failure society of America and Japanese heart failure society position statement on endomyocardial biopsy. European Journal of Heart Failure, 2021. 23(6): p. 854-871. [CrossRef]

- Palaskas, N., et al., Immune checkpoint inhibitor myocarditis: pathophysiological characteristics, diagnosis, and treatment. Journal of the American Heart Association, 2020. 9(2): p. e013757. [CrossRef]

- Brahmer, J.R., et al., Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) clinical practice guideline on immune checkpoint inhibitor-related adverse events. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer, 2021. 9(6). [CrossRef]

- Heinzerling, L., et al., Cardiotoxicity associated with CTLA4 and PD1 blocking immunotherapy. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer, 2016. 4: p. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Nghiem, P.T., et al., PD-1 blockade with pembrolizumab in advanced Merkel-cell carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine, 2016. 374(26): p. 2542-2552. [CrossRef]

- Varricchi, G., et al., Cardiotoxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors. ESMO open, 2017. 2(4): p. e000247. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, S., et al., Late-onset fulminant myocarditis with immune checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab. Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 2018. 34(6): p. 812. e1-812. e3. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.T., et al., Late-onset immunotherapy-induced myocarditis 2 years after checkpoint inhibitor initiation. Cardio Oncology, 2022. 4(5): p. 727-730. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Summary of cases.

Table 1.

Summary of cases.

| |

Case-1 |

Case-2 |

Case-3 |

Case-4 |

| ICI-agent |

Pembrolizumab |

Nivolumab |

Nivolumab |

Pembrolizumab |

| Primary Diagnosis |

RCC |

RCC |

Nasopharynx |

Lung |

| ICI to onset myocarditis(month) |

6 |

6 |

20 |

6 |

| Age |

56 |

78 |

64 |

74 |

| Sex |

male |

male |

male |

male |

| CV risk factors |

AF, DM, HT |

AF, HT |

none |

DM,HT |

| Myocarditis presentation |

chest tightness and shortness of breath |

bradycardia and weakness |

bradycardia, weakness, and hypotension |

tachycardia, weakness, and shortness of breath, |

| cTnT(ng/mL) |

7.4 |

500 |

0.5 |

0.001 |

| NT-proBNP (ng/L) |

2302 |

30000 |

1200 |

800 |

| ECG |

sinus tachycardia, ST depression in leads V4, V5, V6 |

sinus bradycardia

ST depression in leads D1, aVL, V4, V5, and V6 |

ventricular extrasystoles and sinus bradycardia |

sinus tachycardia and new onset of ventricular extrasystoles |

| ECO |

LVEF: 25%, dilated left ventricle, and biatrial dilatation |

LVEF: 15%, moderate aortic regurgitation, and a dilated left ventricle |

LVEF of 60% and moderate aortic regurgitation |

LVEF of 60%. |

| cMRI |

Diffuse |

Diffuse |

subepicardial |

subepicardial |

| Metylprednizolon, dose mg/kg) and time(month) |

1mg/kg, 3 months |

1mg/kg, 3 weeks |

1000 mg 3 days and 1mg/kg 2 months |

1mg/kg, 2 months |

| Other IS-agent |

IVIG |

none |

mycophenolate mofetil |

none |

| Causes of death |

Disease progress |

cardiogenic shock |

Disease progress |

alive |

ICI: Immune checkpoint Inhibitor

CV: Cardiovascular

cTnT: Cardiac troponin T

NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide

ECG: electrocardiogram

ECO: Echocardiography

cMRI: Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging

IS: Immunosuppressive |

HT: Hypertension

DM: Diabetes mellitus

AF: Atrial fibrillation

IVIG: intravenous immunoglobulin

RCC: Renal cell carcinoma |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the contenst. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).