Submitted:

25 December 2024

Posted:

26 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

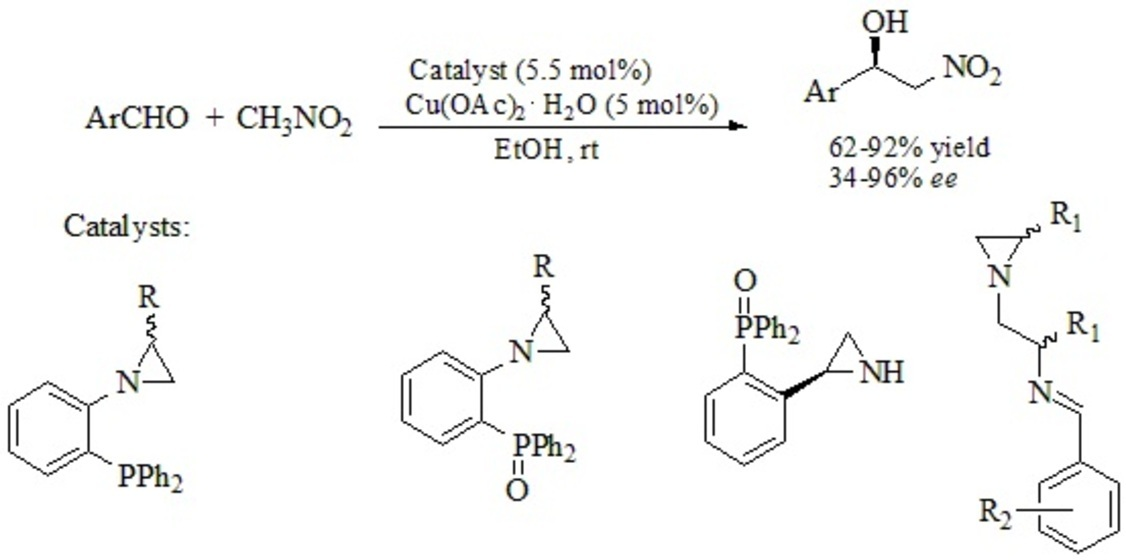

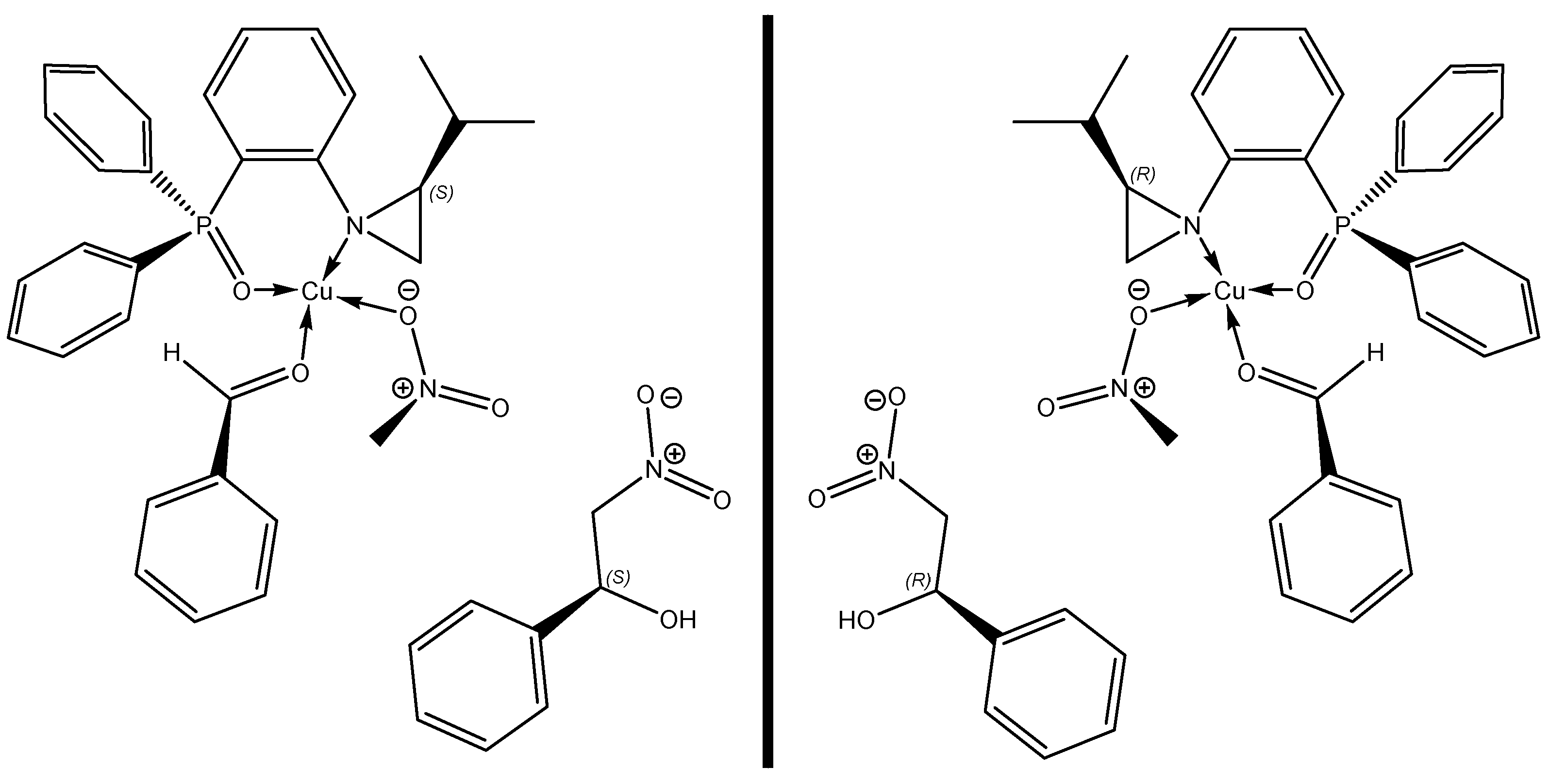

Remaining in the research topic related to the discovery of new catalytic abilities of chiral organophosphorus derivatives of aziridines, we decided to synthesize organophosphorus compounds containing an aziridine ring, previously described by our group, and to investigate their catalytic activity in the asymmetric nitroaldol (Henry) reaction between aromatic aldehydes and nitromethane in the presence of catalytic amounts of copper (II) acetate. In some cases, the chiral β-nitroalcohols obtained with high chemical yield were characterized by very high values of enantiomeric excess (over 95%). What is quite important, the use of two enantiomerically pure catalysts differing in the absolute configuration of the aziridine unit led to the formation of two enantiomeric products of the Henry reaction.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

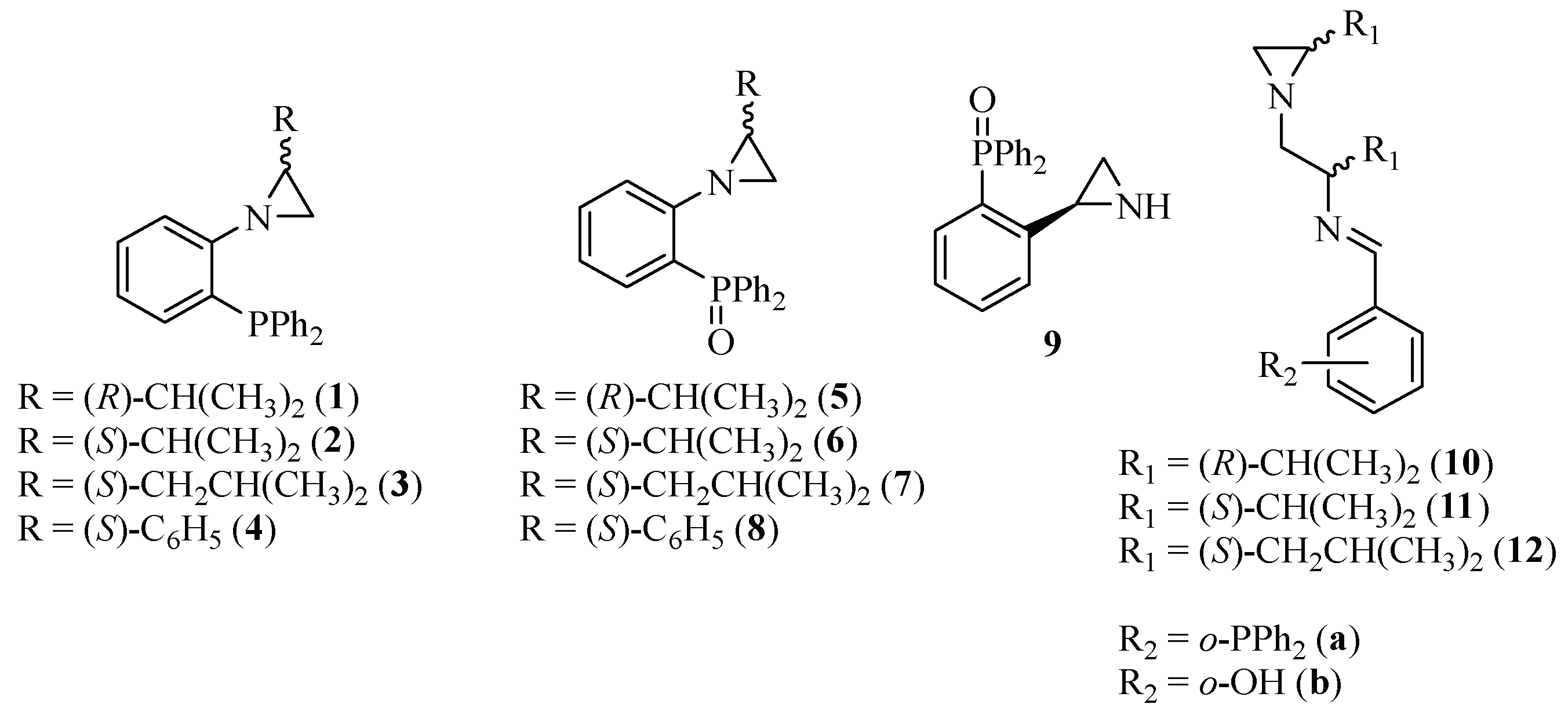

2.1. Synthesis of Chiral Catalysts 1-12

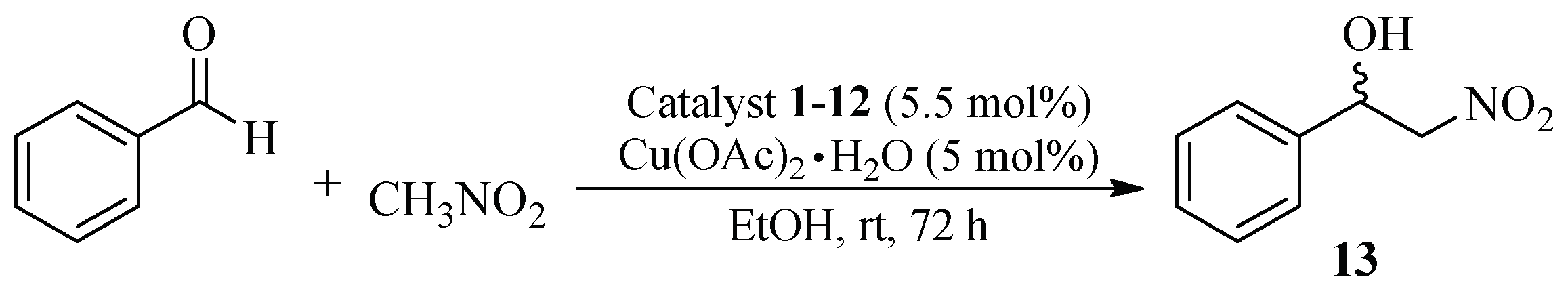

2.2. Asymmetric Nitroaldol (Henry) Reaction Catalyzed by Chiral Systems 1-12

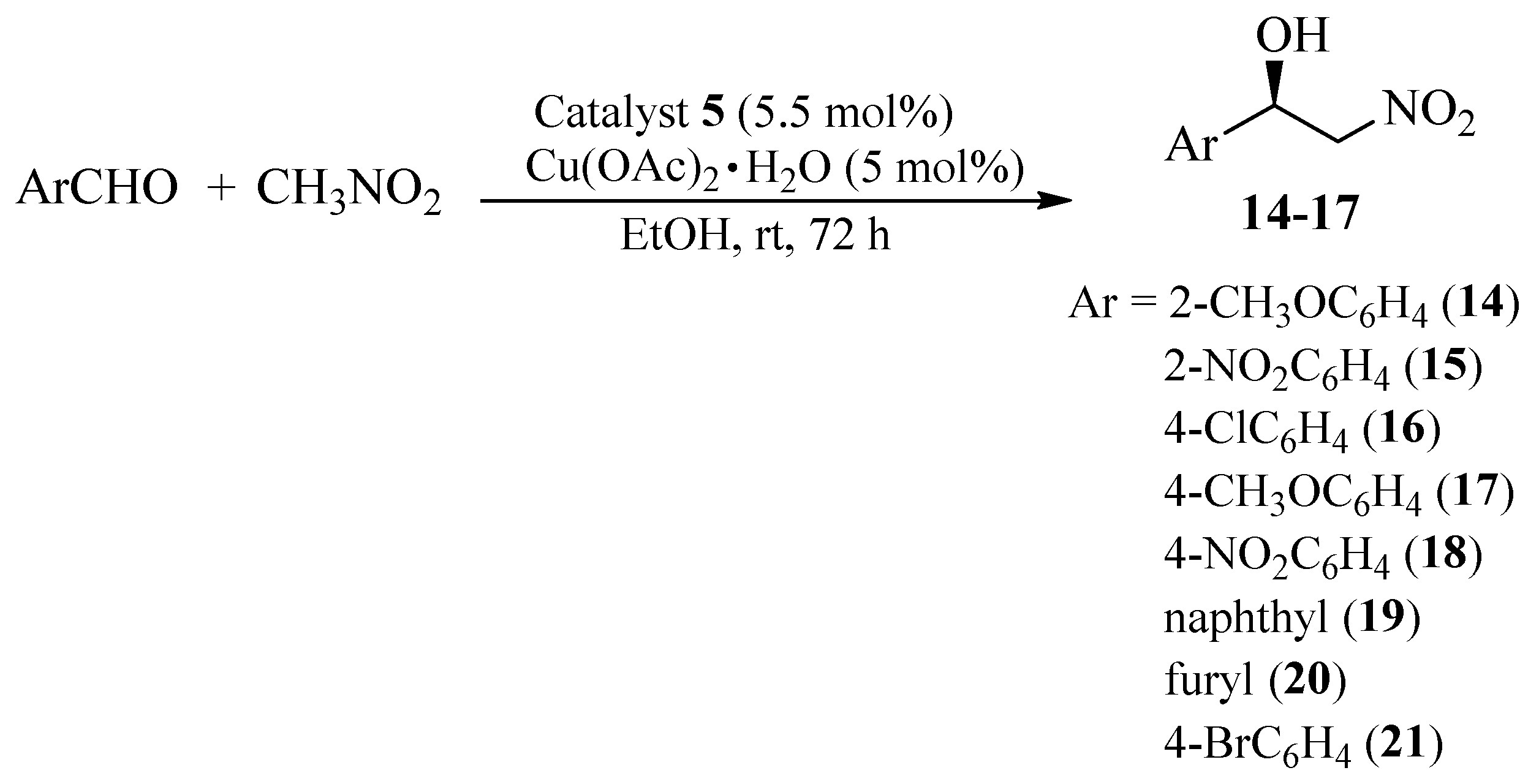

2.3. Asymmetric Henry Reaction Promoted by Aziridine-Phosphine 5 – Scope of the Starting Materials

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Asymmetric Nitroaldol (Henry) Reaction – General Procedure

- 1-Phenyl-2-nitroethanol 13

- 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 2.84 (s, 1H, OH), 4.55 (dd, J = 3.0, 13.2 Hz, 1H, CH2NO2), 4.62 (dd, J = 9.6, 13.2 Hz, 1H, CH2NO2), 5.49 (d, J = 9.6, 1H, CHOH), 7.39 – 7.44 (m, 5H, CHar);

- (R)-1-(2-Methoxyphenyl)-2-nitroethanol 14

- 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 3.13 (s, 1H, OH), 3.91 (s, 3H, OCH3), 4.60 (dd, J = 9.3, 13.0 Hz, 1H, CH2NO2), 4.68 (dd, J = 3.0, 13.0 Hz, 1H, CH2NO2), 5.66 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H, CHOH), 6.93 – 6.95 (m, 1H, CHar), 7.03 – 7.05 (m, 1H, CHar), 7.34 – 7.37 (m, 1H, CHar); 7.46 – 7.48 (m, 1H, CHar);

- (R)-1-(2-Nitrophenyl)-2-nitroethanol 15

- 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 3.18 (s, 1H, OH), 4.58 (dd, J = 9.0, 13.9 Hz, 1H, CH2NO2), 4.90 (dd, J = 2.0, 13.9 Hz, 1H, CH2NO2), 6.08 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H, CHOH), 7.57 – 7.59 (m, 1H, CHar), 7.76 – 7.78 (m, 1H, CHar), 7.97 – 7.98 (m, 1H, CHar); 8.10 – 8.11 (m, 1H, CHar);

- (R)-1-(4-Chlorophenyl)-2-nitroethanol 16

- 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 3.02 (s, 1H, OH), 4.51 (dd, J = 3.1, 13.4 Hz, 1H, CH2NO2), 4.58 (dd, J = 9.3, 13.4 Hz, 1H, CH2NO2), 5.46 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H, CHOH), 7.36 – 7.41 (m, 4H, CHar);

- (R)-1-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-2-nitroethanol 17

- 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 2.85 (br.s, 1H, OH), 3.83 (s, 3H, OCH3), 4.49 (dd, J = 3.0, 13.1 Hz, 1H, CH2NO2), 4.61 (dd, J = 9.6, 13.1 Hz, 1H, CH2NO2), 5.42 (dd, J = 3.0, 9.6 Hz, 1H, CHOH), 6.93 – 6.95 (m, 2H, CHar), 7.33 – 7.34 (m, 2H, CHar);

- (R)-1-(4-Nitrophenyl)-2-nitroethanol 18

- 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 3.22 (s, 1H, OH), 4.57 – 4.65 (m, 2H, CH2NO2), 5.63 (dd, J = 3.3 Hz, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, CHOH), 7.64 – 7.66 (m, 2H, CHar), 8.28 – 8.30 (m, 2H, CHar);

- (R)-1-(naphthalen-1-yl)-2-nitroethanol 19

- 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 2.91 – 2.93 (m, 1H, OH), 4.66 – 4.74 (m, 2H, CH2NO2), 6.27–6.29 (m, 1H, CHOH), 7.53 – 7.59 (m, 2H, CHar), 7.61 – 7.64 (m, 1H, CHar), 7.78 – 7.79 (m, 1H, CHar), 7.88 – 7.95 (m, 2H, CHar), 8.06 – 8.08 (m, 1H, CHar);

- (R)-1-(4-bromophenyl)-2-nitroethanol 21

- 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 2.90 (s, 1H, OH), 4.52 (dd, J = 3.0, 13.5 Hz, 1H, CH2NO2), 4.60 (dd, J = 9.5, 13.5 Hz, 1H, CH2NO2), 5.46 (dd, J = 3.0, 9.5 Hz, 1H, CHOH), 7.31 – 7.33 (m, 2H, CHar), 7.55 – 7.57 (m, 2H, CHar);

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garg, A.; Rendina, D.; Bendale, H.; Akiyama, T.; Ojima, I. Recent advances in catalytic asymmetric synthesis. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1398397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.-M.; Cheng, Y.-Z.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, Y.-D.; Fan, Q.-H.; You, S.-L.; Luo, S.; Zhu, S.-F.; Fu, X.-F.; Zhou, Q.-L. Recent Progress of Asymmetric Catalysis from a Chinese Perspective. CCS Chem. 2023, 5, 2685–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamatam, R.; Shin, D. Asymmetric Synthesis of US-FDA Approved Drugs over Five Years (2016–2020): A Recapitulation of Chirality. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.K.; Paniraj, A.S.R.; Tambe, Y.B. Developments in the Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of Agrochemicals and Their Synthetic Importance. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 14761–14780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballini, R.; Palmieri, A. Nitroalkanes: Synthesis, Reactivity, and Applications, 1st ed; WILEY-VCH GmbH Weinheim, Germany, 2021, pp. 59–105.

- Dong, L.; Chen, F.-E. Asymmetric catalysis in direct nitromethane-free Henry reactions. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 2113–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.; Sun, Q.; Quan, Z.; Sun, W. Wang, X. The synthesis of chiral tridentate ligands from L-proline and their application in the copper(II)-catalyzed enantioselective Henry reaction. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2017, 28, 954–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska-Błajet, M.; Skarżewski, J. New chiral thiols and C2-symmetrical disulfides of Cinchona alkaloids: ligands for the asymmetric Henry reaction catalyzed by CuII complexes. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2009, 20, 1992–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; He, J.; Mu, Y. Synthesis of chiral salan ligands with bulky substituents and their application in Cu-catalyzed asymmetric Henry reaction. J. Organomet. Chem. 2020, 928, 121546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, K.; Kato, Y.; Takeuchi, N.; Hayashi, Y.; Hagiwara, Y.; Shibuya, S.; Natsume, T.; Matsugi, M. Asymmetric Henry Reaction Using Cobalt Complexes with Bisoxazoline Ligands Bearing Two Fluorous Tags. Molecules 2023, 28, 7632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rénio, M.R.R.; Sousa, F.J.P.M.; Tavares, N.C.T.; Valente, A.J.M.; da Silva Serra, M.E.; Murtinho, D. (3S,4S)-N-substituted-3,4-dihydroxypyrrolidines as ligands for the enantioselective Henry reaction. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2021, 35, e6175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alammari, A.S.; Al-Majid, A.M.; Barakat, A.; Alshahrani, S.; Ali, M.; Islam, M.S. ; Asymmetric Henry Reaction of Nitromethane with Substituted Aldehydes Catalyzed by Novel In Situ Generated Chiral Bis(β-Amino Alcohol-Cu(Oac)2·H2O Complex. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachwalski, M.; Leśniak, S.; Sznajder, E.; Kiełbasiński, P. Highly enantioselective Henry reaction catalyzed by chiral tridentate heterorganic ligands. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2009, 20, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiełbasiński, P.; Rachwalski, M.; Kaczmarczyk, S.; Leśniak, S. Polydentate chiral heteroorganic ligands/catalysts – impact of particular groups on their activity in selected reactions of asymmetric synthesis. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2013, 24, 1417–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, D.H.S.; Chatterjee, A.; Padhi, S.K. Biocatalytic approaches for enantio and diastereoselective synthesis of chirl β-nitroalcohols. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021, 19, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-H.; Wan, N.-W.; Da, X.-Y.; Mou, X.-Q.; Wang, Z.-X.; Chen, Y.-Z.; Liu, Z.-Q.; Zheng, Y.-G. Enantiocomplementary synthesis of β-adrenergic blocker precursors via biocatalytic nitration of phenyl glycidyl ethers. Bioorg. Chem. 2023, 138, 106640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tentori, F.; Brenna, E.; Colombo, D.; Crotti, M.; Gatti, F.G.; Ghezzi, M.C.; Pedrocchi-Fantoni, G. Biocatalytic Approach to Chiral β-Nitroalcohols by Enantioselective Alcohol Dehydrogenase-Mediated Reduction of α-Nitroketones. Catalysts 2018, 8, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jesús Cruz, P.; Johnson, J.S. Crystallization-Enabled Henry Reactions: Stereoconvergent Construction of Fully Substituted [N]-Asymmetric Centers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 15803–15811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doğan, Ö.; Çağli, E. PFAM catalyzed enantioselective diethylzinc addition to imines. Turk. J. Chem. 2015, 39, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wujkowska, Z.; Zawisza, A.; Leśniak, S.; Rachwalski, M. Phosphinoyl-aziridines as a new class of chiral catalysts for enantioselective Michael addition. Tetrahedron 2019, 75, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchcic, A.; Zawisza, A.; Leśniak, S.; Rachwalski, M. Asymmetric Friedel-Crafts Alkylation of Indoles Catalyzed by Chiral Aziridine-Phosphines. Catalysts 2020, 10, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchcic, A.; Zawisza, A.; Leśniak, S.; Adamczyk, J.; Pieczonka, A.M.; Rachwalski, M. Enantioselective Mannich Reaction Promoted by Chiral Phosphinoyl-Aziridines. Catalysts 2019, 9, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchcic-Szychowska, A.; Adamczyk, J.; Marciniak, L.; Pieczonka, A.M.; Zawisza, A.; Leśniak, S.; Rachwalski, M. Efficient Asymmetric Simmons-Smith Cyclopropanation and Diethylzinc Addition to Aldehydes Promoted by Enantiomeric Aziridine-Phosphines. Catalysts 2021, 11, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieczonka, A.M.; Marciniak, L.; Rachwalski, M.; Leśniak, S. Enantiodivergent aldol condensation in the presence of aziridine/acid/water systems. Symmetry 2020, 12, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymańska, J.; Rachwalski, M.; Pieczonka, A.M. Highly Efficient Asymmetric [3+2]-Cycloaddition Promoted by Chiral Aziridine-Functionalized Organophosphorus Compounds. Molecules 2024, 29, 3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomo, C.; Oiarbide, M.; Mielgo, A. Unveiling Reliable Catalysts for the Asymmetric Nitroaldol (Henry) Reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 5442–5444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Nayab, S.; Jeong, J.H. An efficient synthetic approach towards a single diastereomer of (2R,3R)-N2,N3-bis((S)-1-phenylethyl)butane-2,3-diamine via metalation and demetalation. Transit. Met. Chem. 2020, 45, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subba Reddy, B.V.; Madhusudana Reddy, S.; Manisha, S.; Madan, C. Asymmetric Henry reaction catalyzed by a chiral Cu(II) complex: a facile enantioselective synthesis of (S)-2-nitro-1-arylethanols. Tetraheron: Asymmetry 2011, 22, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.Q.; Qi, G.; Judeh, Z.M.A. Efficient Asymmetric Copper(I)-Catalyzed Henry Reaction Using Chiral N-Alkyl-C1-tetrahydro-1,1′-bisisoquinolines. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 4892–4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshisawa, A.; Feula, A.; Male, L.; Leach, A.G.; Fossey, J.S. Rigid and concave, 2,4-cis-substituted azetidine derivatives: A platform for asymmetric catalysis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yearick Spangler, K.; Wolf, C. Asymmetric Copper(I)-Catalyzed Henry Reaction with an Aminoindanol-Derived Bisoxazolidine Ligand. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 4724–4727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Entry | Catalyst | Yield [%] | ee [%]a | Abs. conf.b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 70 | 40 | (R) |

| 2 | 2 | 68 | 55 | (S) |

| 3 | 3 | 67 | 44 | (S) |

| 4 | 4 | 62 | 34 | (S) |

| 5 | 5 | 90 | 96 | (R) |

| 6 | 6 | 88 | 74 | (S) |

| 7 | 7 | 85 | 56 | (S) |

| 8 | 8 | 82 | 55 | (S) |

| 9 | 9 | 65 | 56 | (S) |

| 10 | 10a | 89 | 80 | (R) |

| 11 | 11a | 70 | 74 | (S) |

| 12 | 11b | 78 | 62 | (S) |

| 13 | 12a | 64 | 50 | (S) |

| Entry | Metal additve | Yield [%] | ee [%]a | Abs. conf.b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cu(OTf)2 ‧ C6H6 | 19 | 1 | (R) |

| 2 | Zn(OTf)2 | 0 | ─ | (R) |

| 3 | CuCl2 ‧ 2 H2O | 0 | ─ | (R) |

| 4 | CuOAc | 47 | 4 | (R) |

| 5 | Cu(OAc)2 ‧ H2O | 90 | 96 | (R) |

| Entry | Ar | Product | Yield [%] | ee [%]a | Abs. conf.b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2-CH3OC6H4 | 14 | 92 | 90 | (R) |

| 2 | 2-NO2C6H4 | 15 | 90 | 82 | (R) |

| 3 | 4-ClC6H4 | 16 | 88 | 80 | (R) |

| 4 | 4-CH3OC6H4 | 17 | 91 | 84 | (R) |

| 5 | 4-NO2C6H4 | 18 | 78 | 94 | (R) |

| 6 | Naphthyl | 19 | 70 | 64 | (R) |

| 7 | Furyl | 20 | 0 | ─ | n.d. |

| 8 | 4-BrC6H4 | 21 | 85 | 86 | (R) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).