6.2. Descriptive Statistics

According to sources [

11], descriptive statistics are brief coefficients that provide an overview of a given set of data, which may represent the entire population or only a sample of it. The two major descriptive statistics measures are central tendency and variability. Descriptive statistics describe the characteristics of the given data and provide essential information to understand the fundamental behavior of the data (or spread). Descriptive statistics define or summarize sample or data collection characteristics, such as the variance definition, standard deviation, or frequency. We can better grasp the characteristics of sample data pieces by using inferential statistics. Understanding sample meanings, variations, and variable distributions can make it much easier to understand data and determine whether our work in this paper is valid. Two uses for descriptive statistics include the following:

To offer basic knowledge regarding variables within a dataset and to identify possible correlations between variables.

The three most prevalent descriptive statistics that may represent graphically or visually are measurements of

• Graphical/Pictorial Techniques

• Central Tendency Measurements

• Dispersion Measurements

• Association Measurements

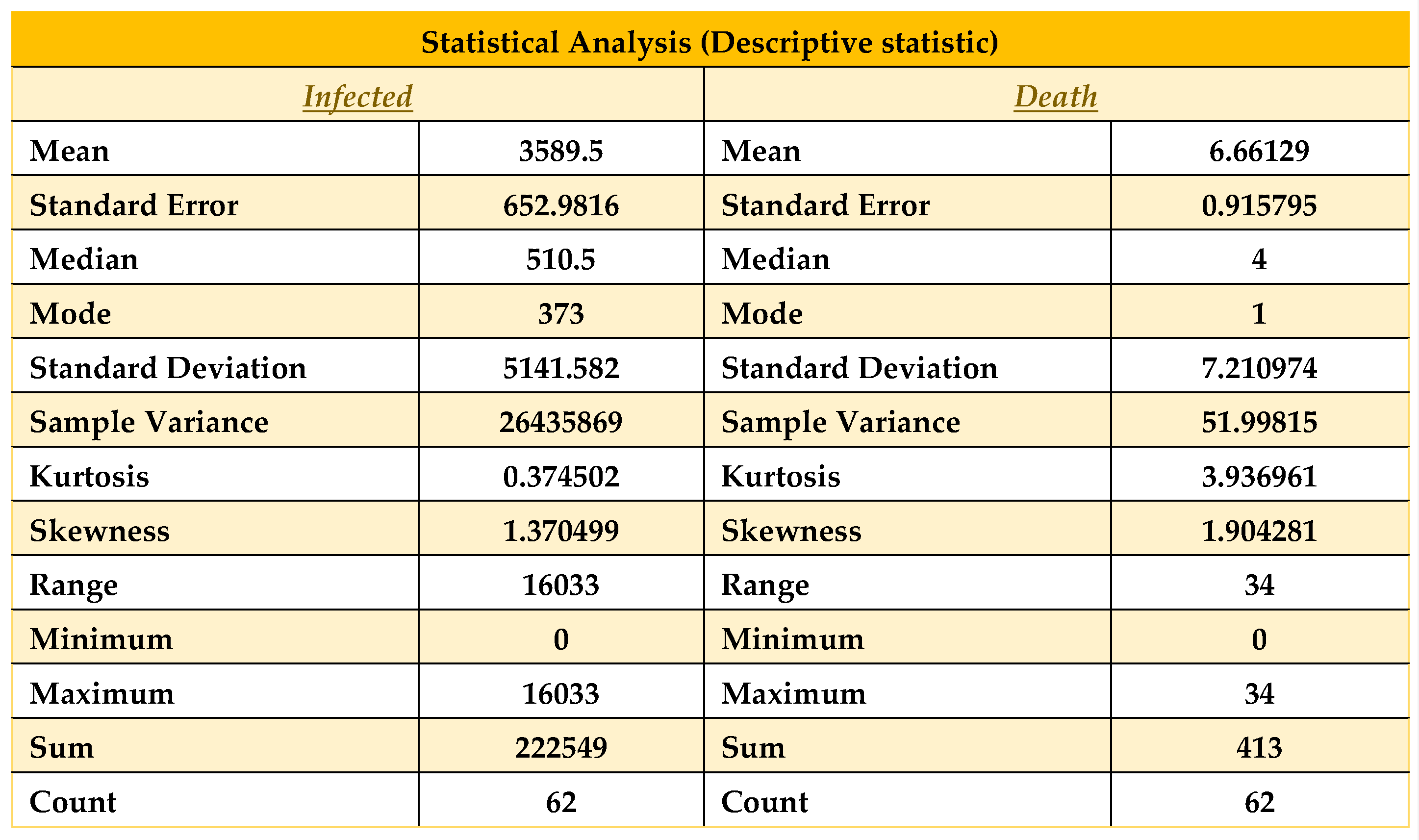

Now that we have taken the data from December 1, 2021, to January 31, 2022, to continue our work on COVID-19 in Bangladesh, we can apply descriptive statistics to the above data in

Table 2 and find all the necessary fields in Excel below.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics on data from 01/12/21 to 31/01/22.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics on data from 01/12/21 to 31/01/22.

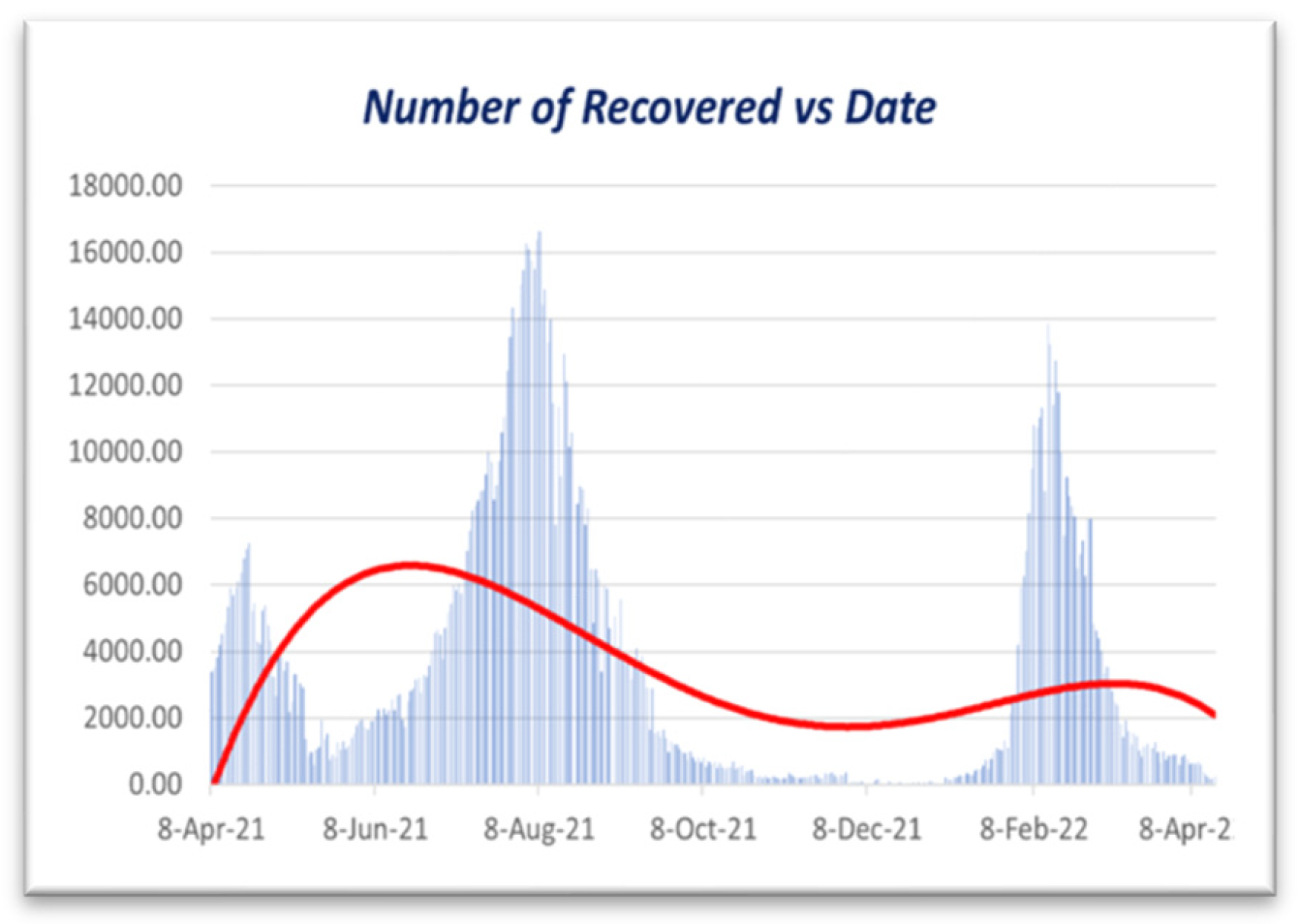

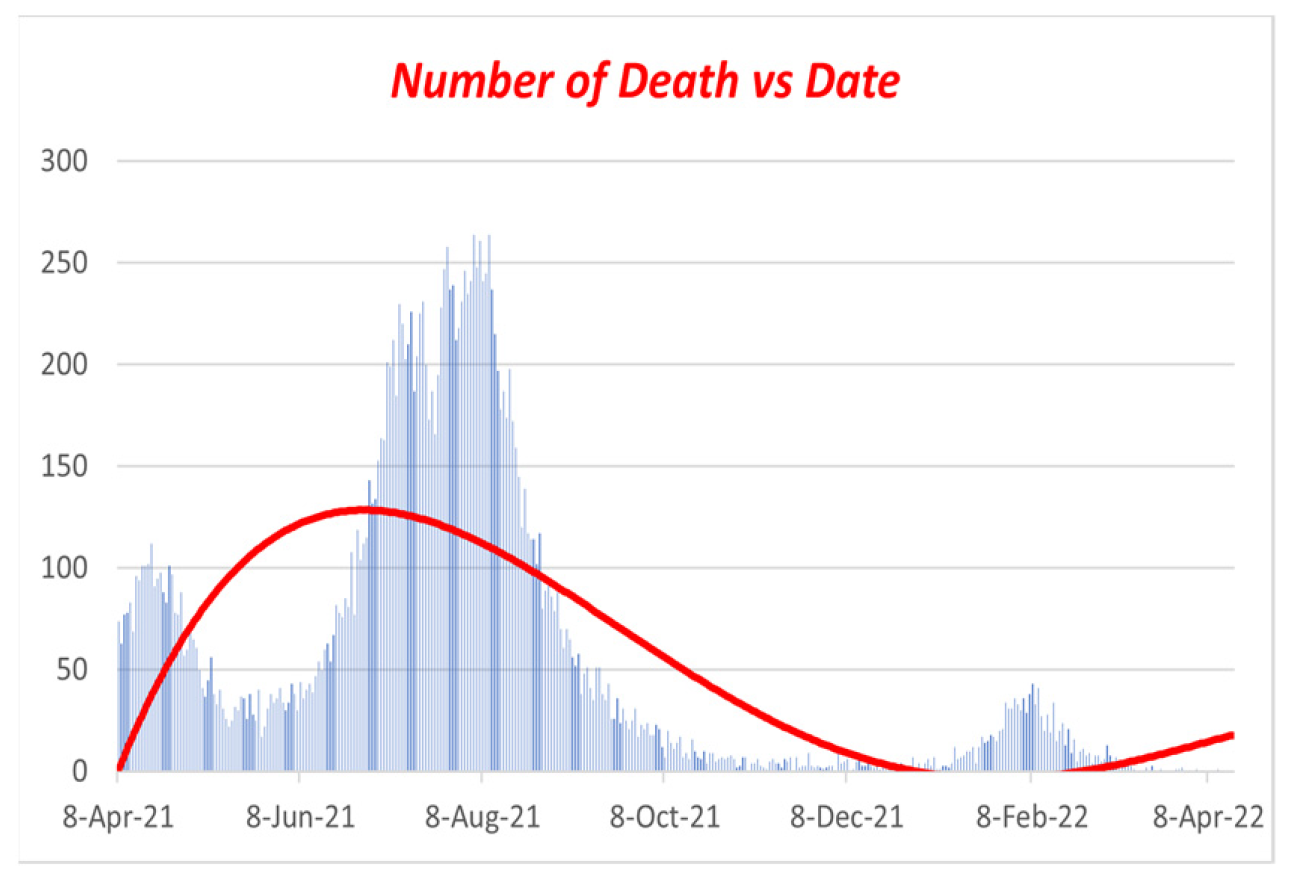

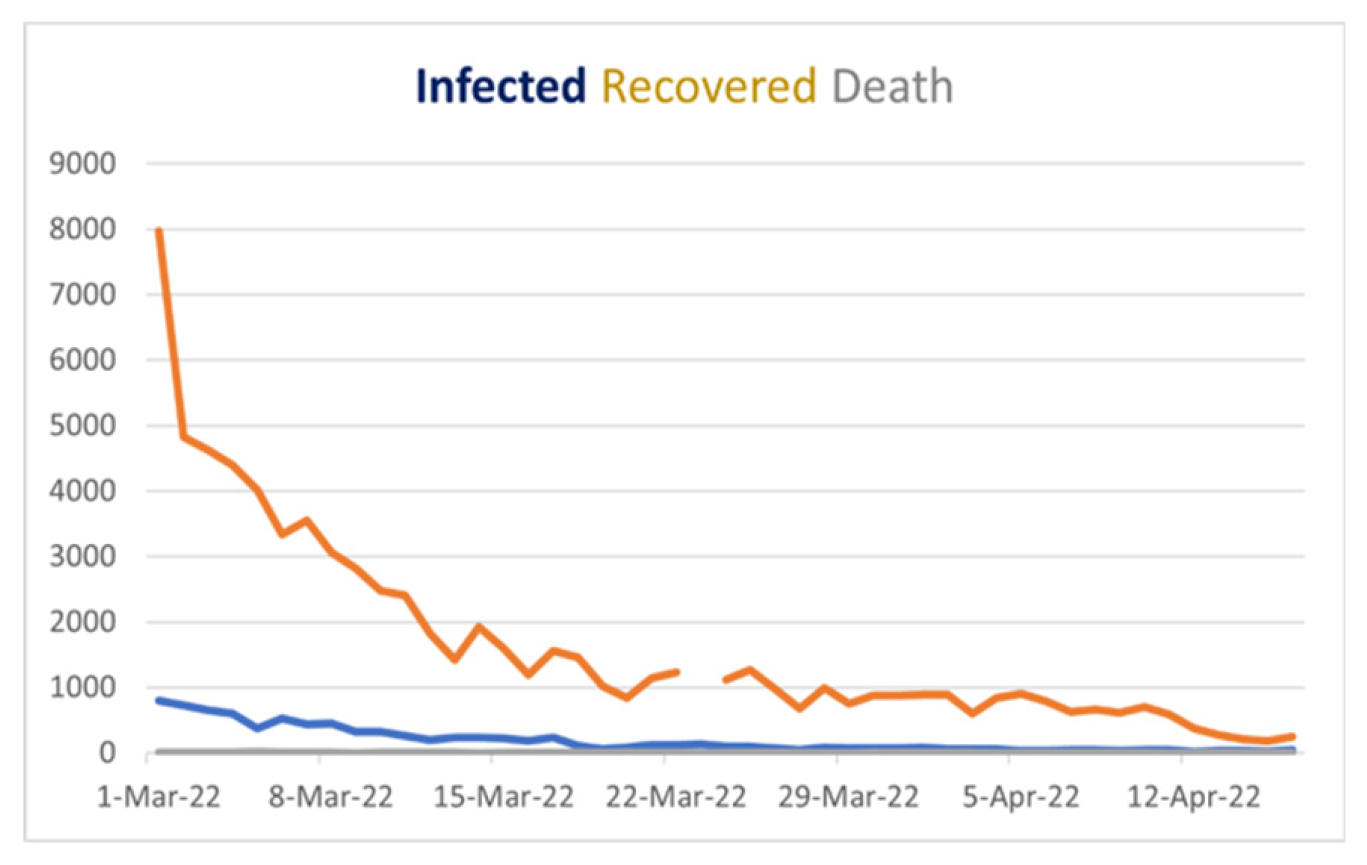

As we see in

Table 5, all statistical properties are normal for the death column. Nevertheless, the recovered and infected columns show a significantly high magnitude, where the number of recovered columns is good for us. Nevertheless, at the same time, the number of infected people is the problem here, which shows the number of infected.

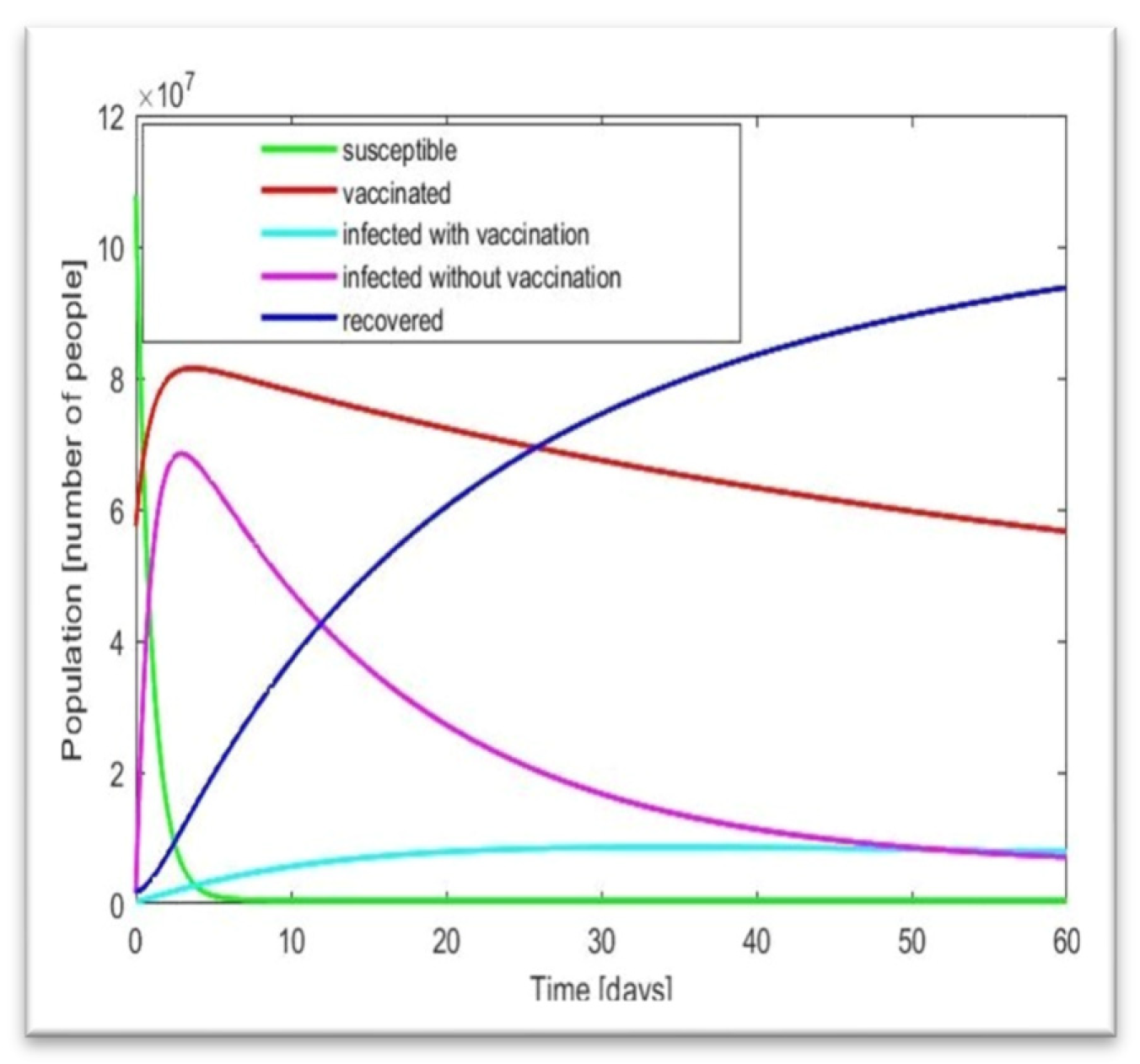

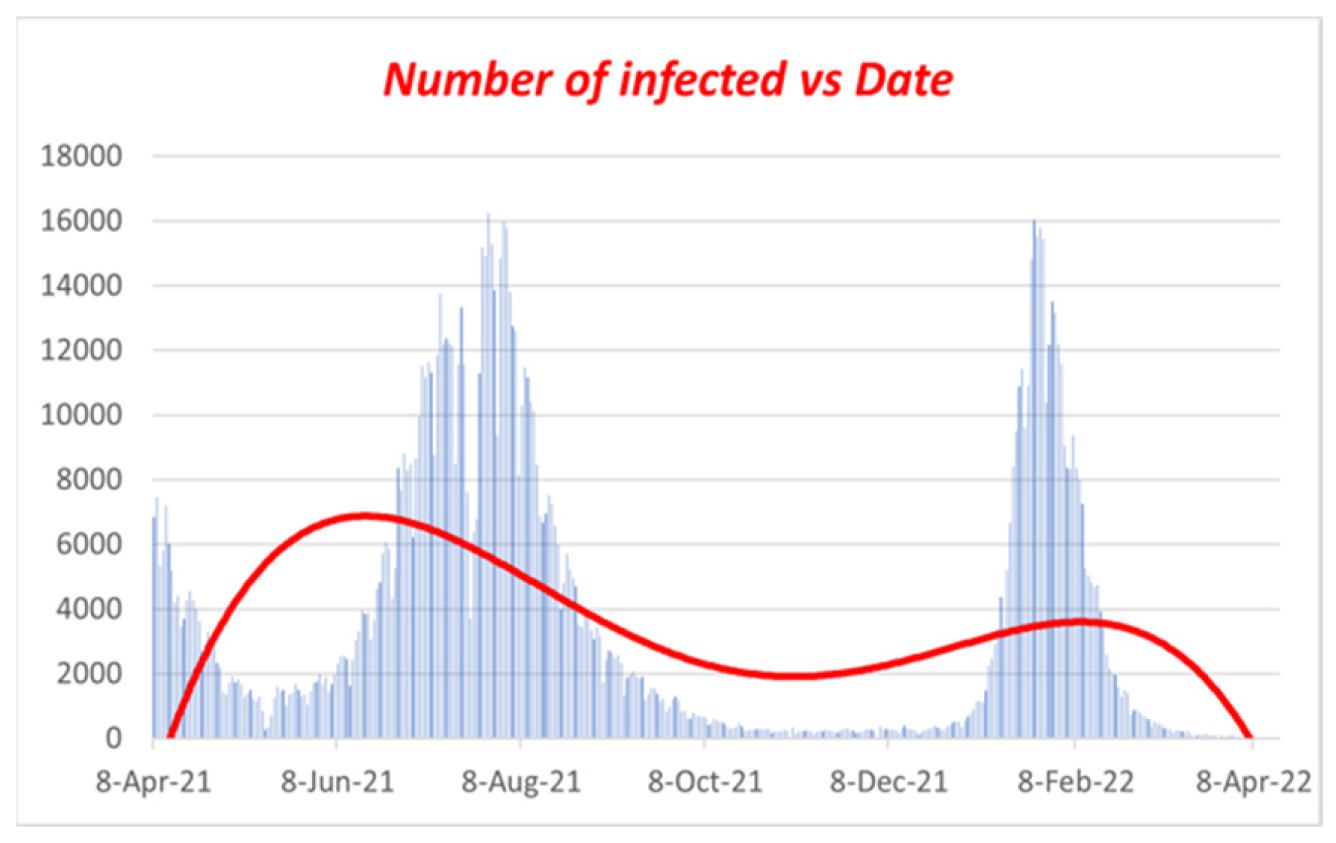

People are increasing, which is quite similar to our result in

Figure 7. Now here, the mode of infected people is 373, and the mean and median are 3589.5 and 510.5, respectively, so we can say that mean > median > mode, which shows that the graph will be positively skewed. On the other hand, in the death column, as it shows mean > median > mode, this graph will also be positively skewed. Therefore, in terms of our figure, we find similar patterns with our statistical analysis. Now, we will discuss these in brief. Here, another property called skewness also matters. As we know, few conditions exist in statistics for skewness, which are [

12]

• The distribution is significantly skewed if skewness is less than -1 or larger than 1.

• The distribution is substantially skewed if skewness falls between -1 and -0.5 or 0.5 and 1.

• The distribution is nearly symmetric if the skewness is between -0.5 and 0.5.

In our case, the skewness for death and infection are 1.90 and 1.374, respectively, so by satisfying the above conditions, we can say that the death and infection curves are highly skewed. From the relation of Mean and Median, the data skewed right. Now let us look at the data from October 1, 2021, to January 31, 2022, and we find the following:

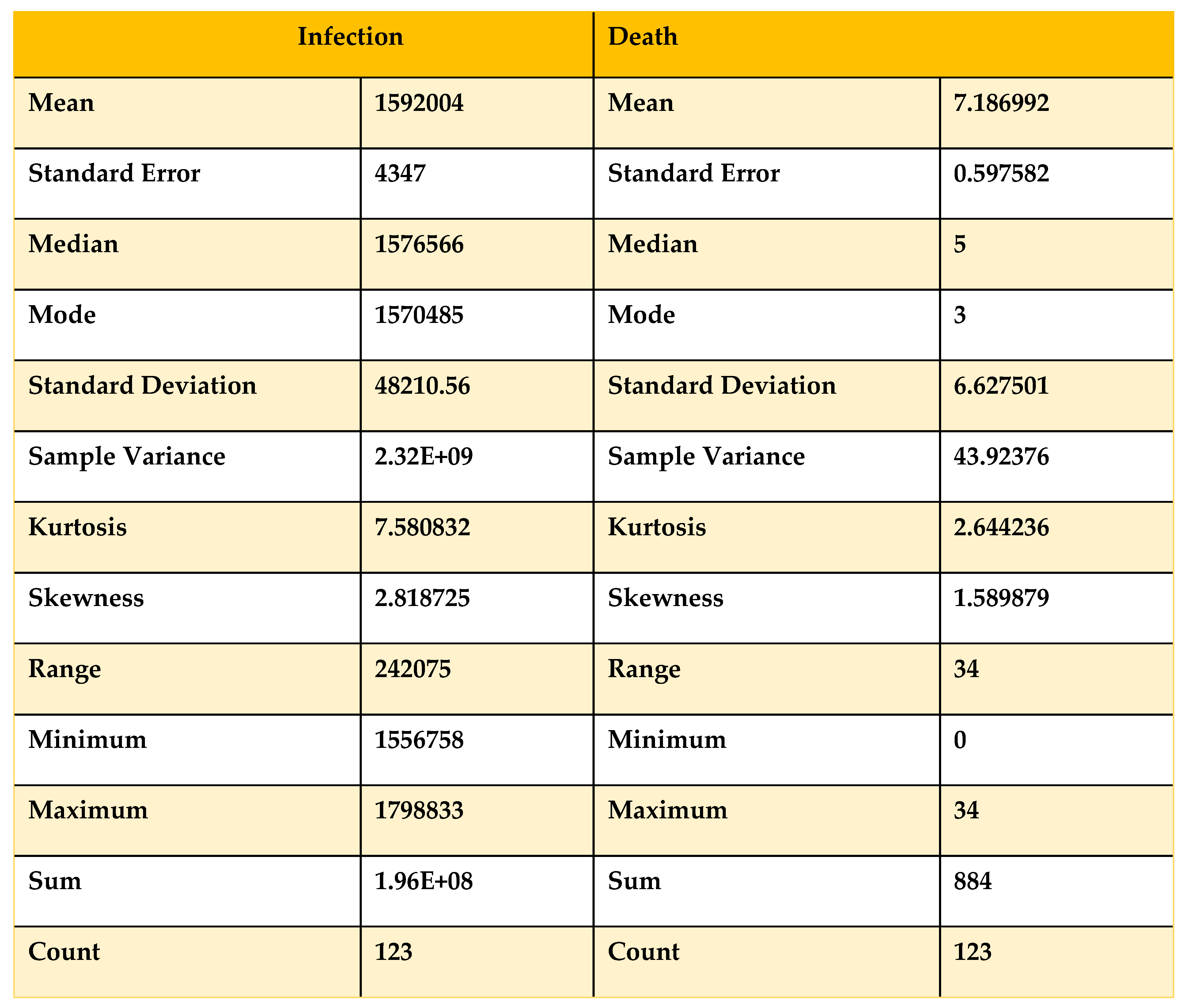

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics on Data from 01/10/21 to 31/01/22.

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics on Data from 01/10/21 to 31/01/22.

Now, if we compare

Table 5 and

Table 6 with the condition, we can see that the skewness for the death curve has increased from 1.58 to 1.90, which denotes that it is shifting from highly skewed to approximately symmetrical. On the other hand, the skewness of the infected has decreased from 2.8 to 1.37, showing that with time, the infected curve is skewed approximately symmetrically and remains right skewed. For more validity, we take data from August 1, 2021, to January 31, 2022, to obtain a clear view.

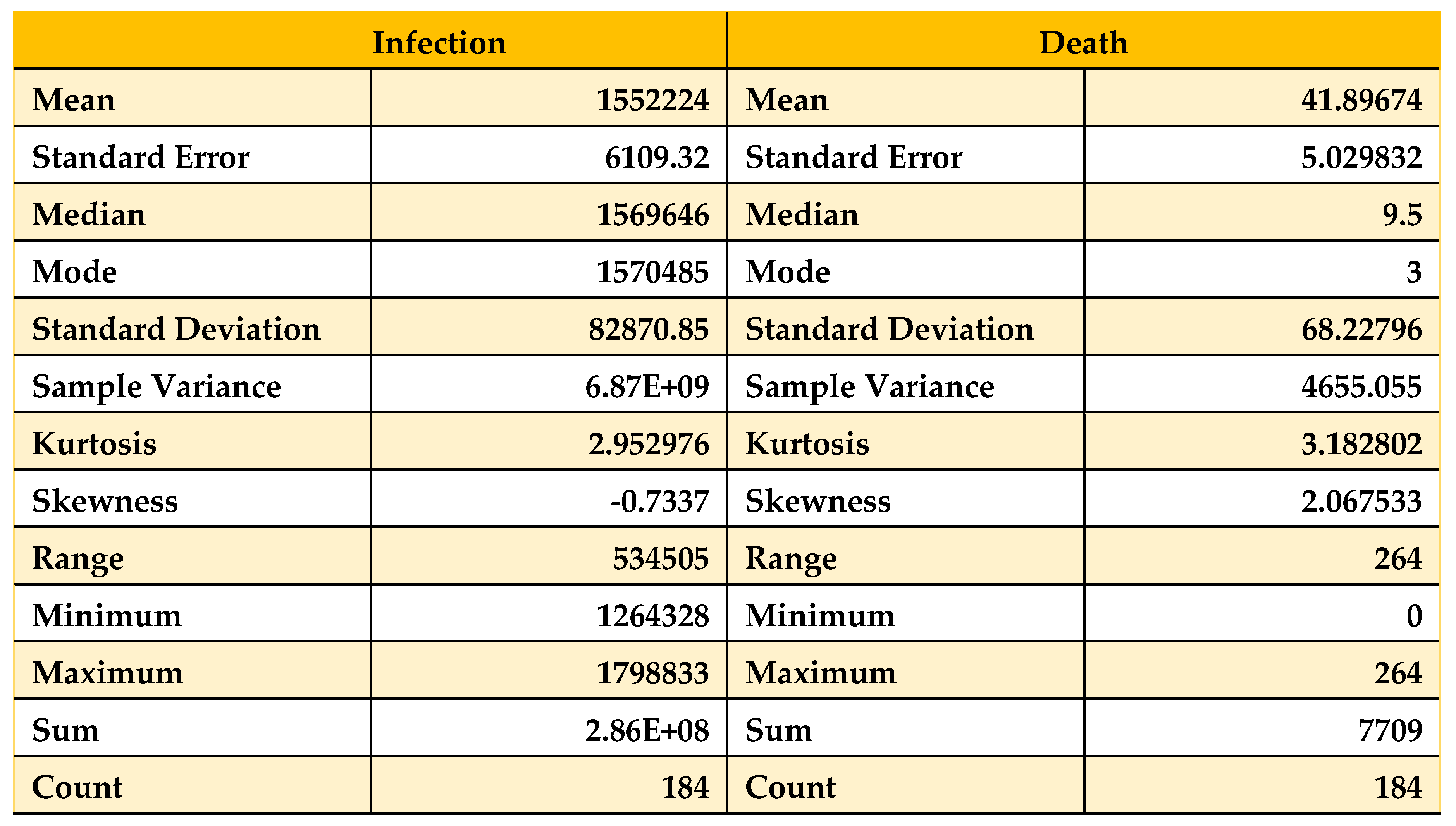

Table 7.

Descriptive statistics on Data from 01/08/21 to 31/01/22.

Table 7.

Descriptive statistics on Data from 01/08/21 to 31/01/22.

Now, if we compare

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7 with the condition, we can see that the skewness for the death curve has decreased from 2.06 to 1.90, which denotes that it is shifting downward. Then, after October 1, 2021, it changes from highly skewed to approximately symmetrical. On the other hand, the skewness of the infected population has increased from -0.73 to 1.37, which shows that with time, the infected population’s curve becomes highly skewed rapidly and remains left skewed. Now, we analyze

Table 5 with our work and find that with time, the death curve has become asymmetric, so we can say that the death curve became and will remain stable, but for the curve of infected people, the curve is skewed. If we take the month of February 2022, we will see that the curve of infected people will be skewed higher, which will be a sign of the next wave of COVID-19. Now we will take data from December 1, 2021, to February 28, 2022, and apply statistical analysis to that data to find the validity of our results.

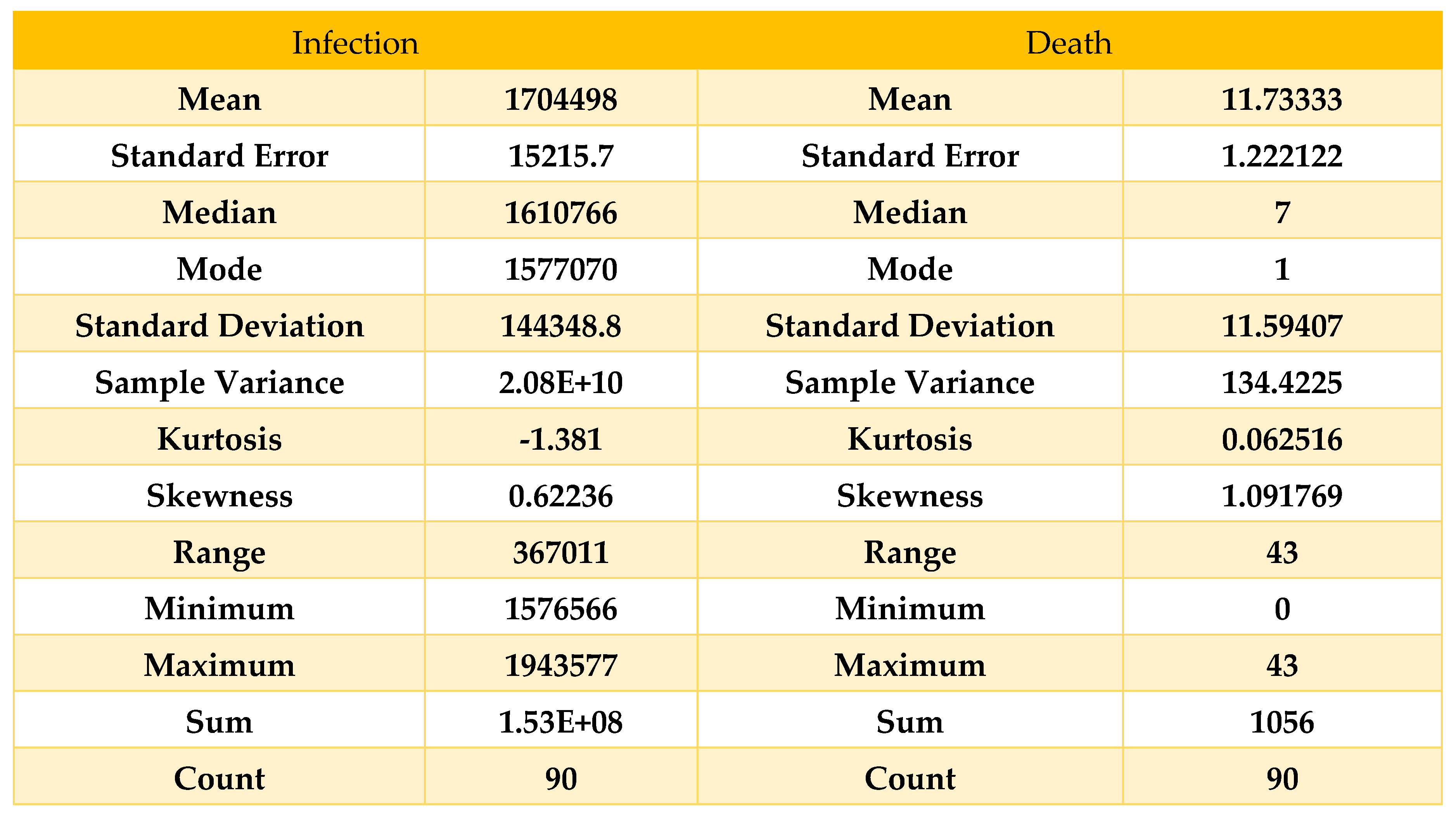

Table 8.

Descriptive statistics on data from 01/12/21 to 28/02/22.

Table 8.

Descriptive statistics on data from 01/12/21 to 28/02/22.

Here, we can see that the skewness for the death curve has fallen compared to

Table 8 and been converted to approximately symmetric; on the other hand, the skewness for the infected curve has decreased from 1.37 to 0.62, which shows the deflection of our curve within February, which means our result from

Figure 7 is accurate because comparing

Table 5 and

Table 8, we can say that the curve of infection rose until February 2022, and then it started decreasing, which states our result to be accurate.

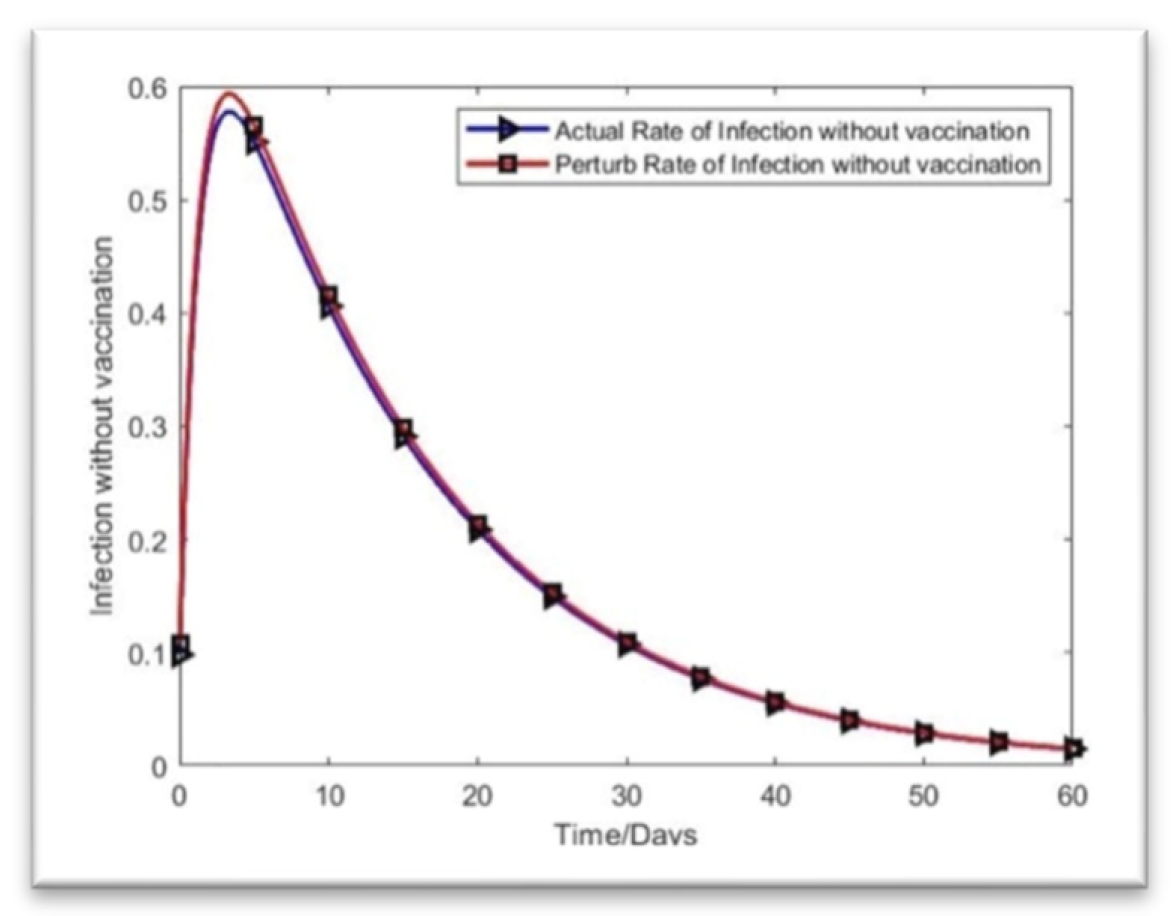

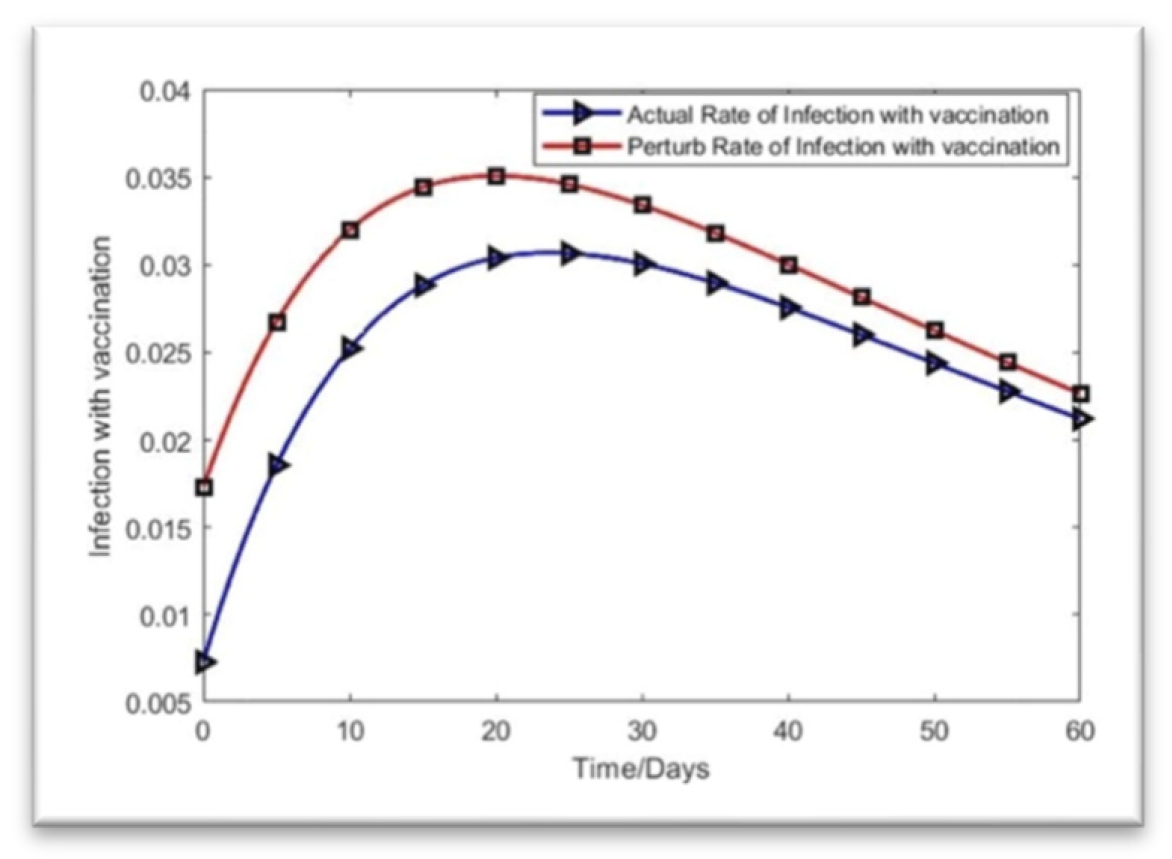

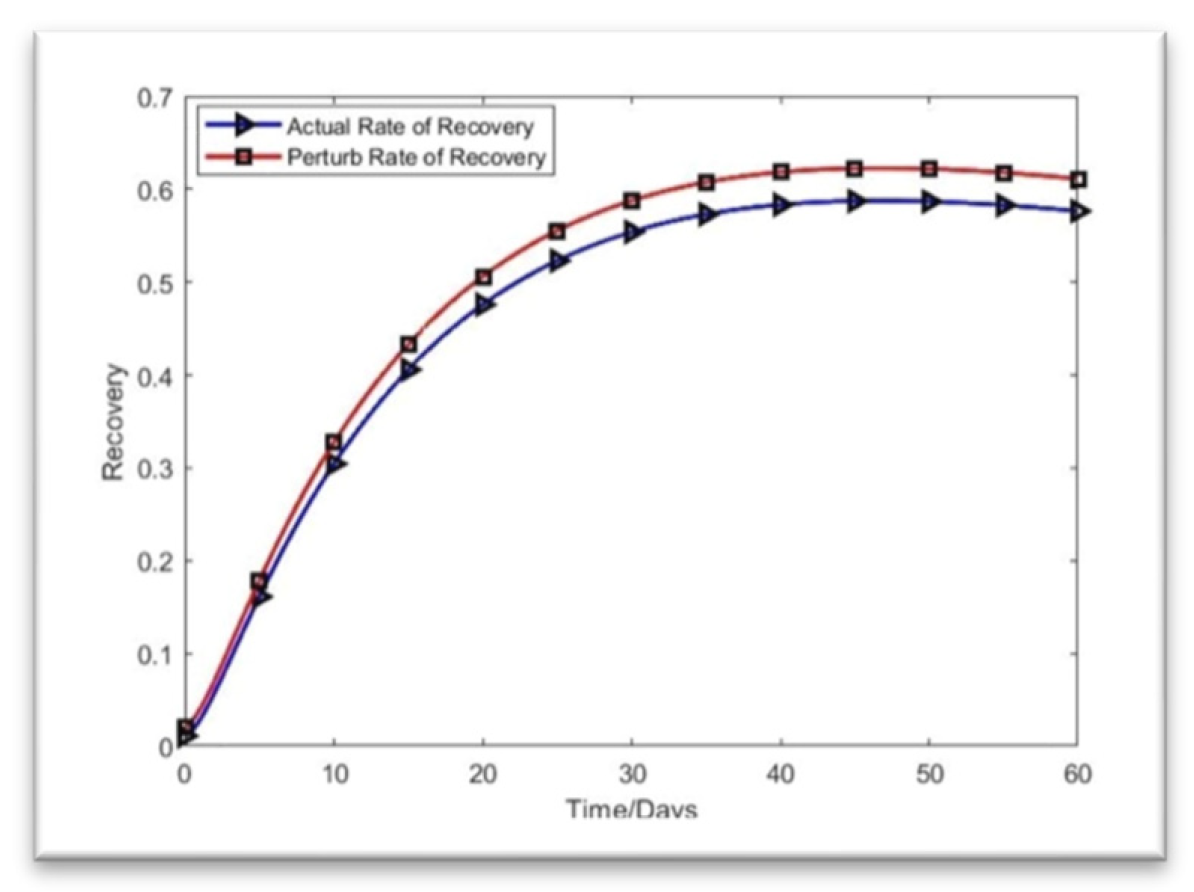

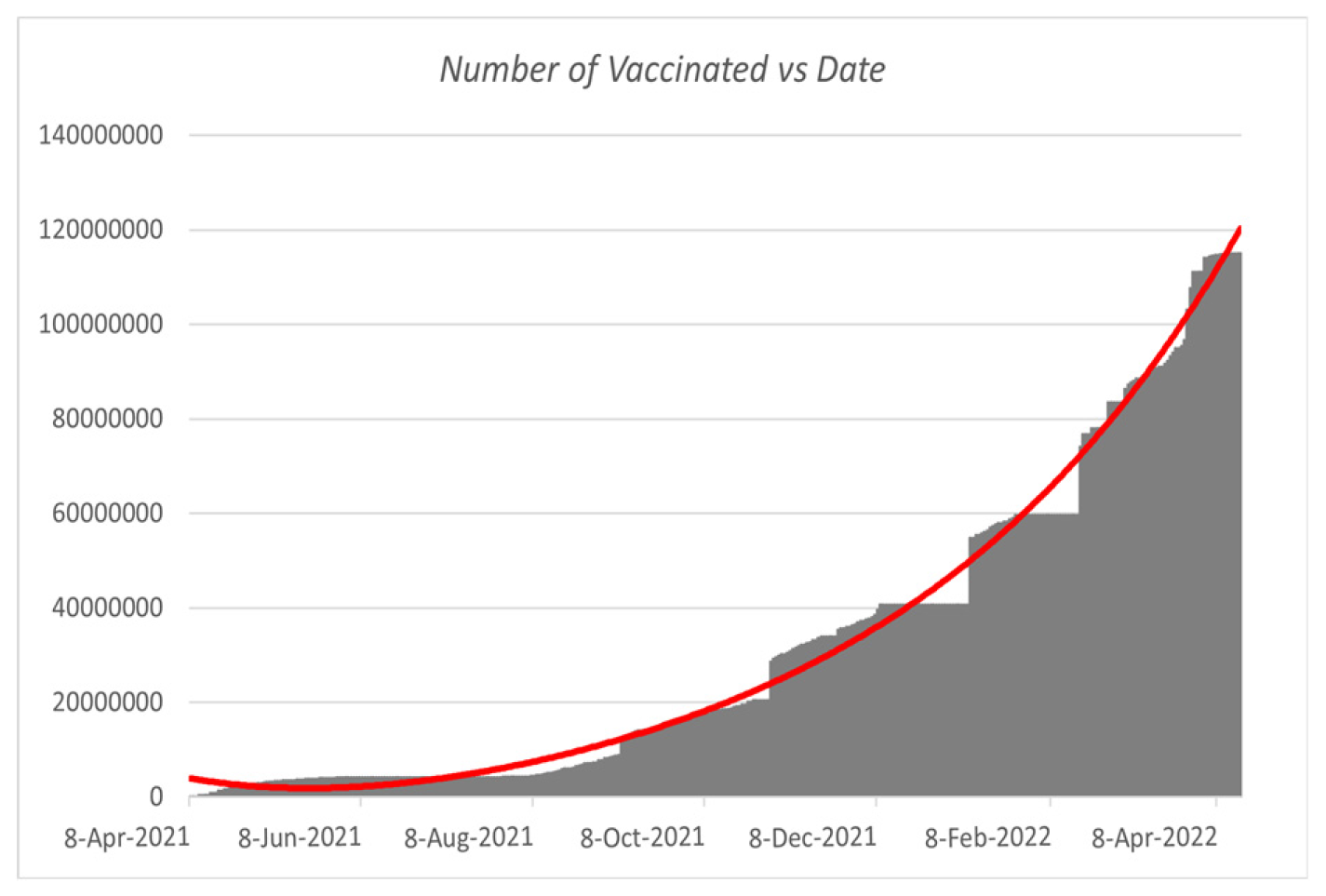

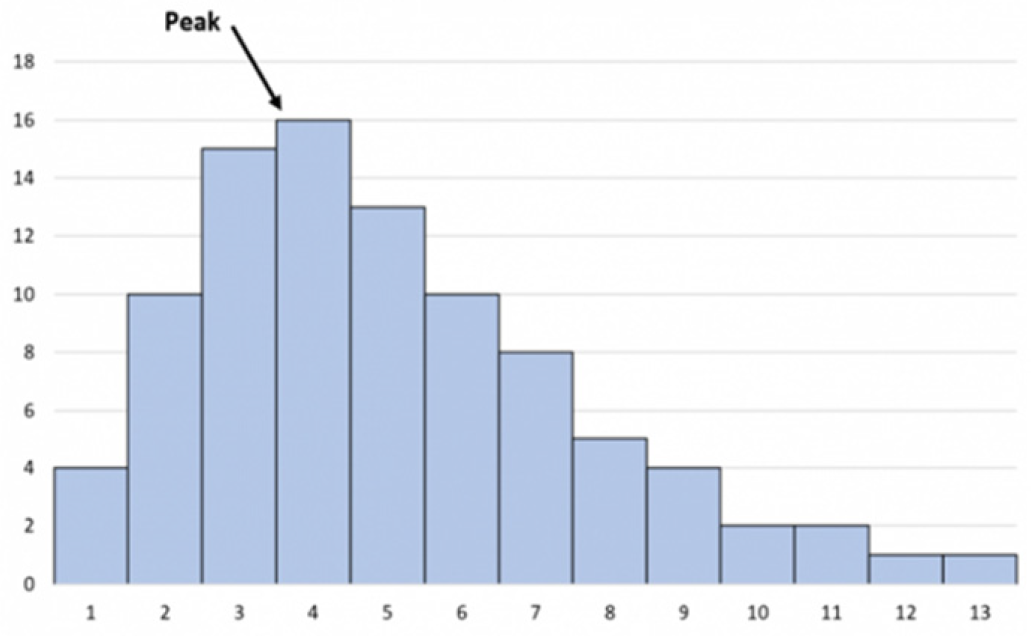

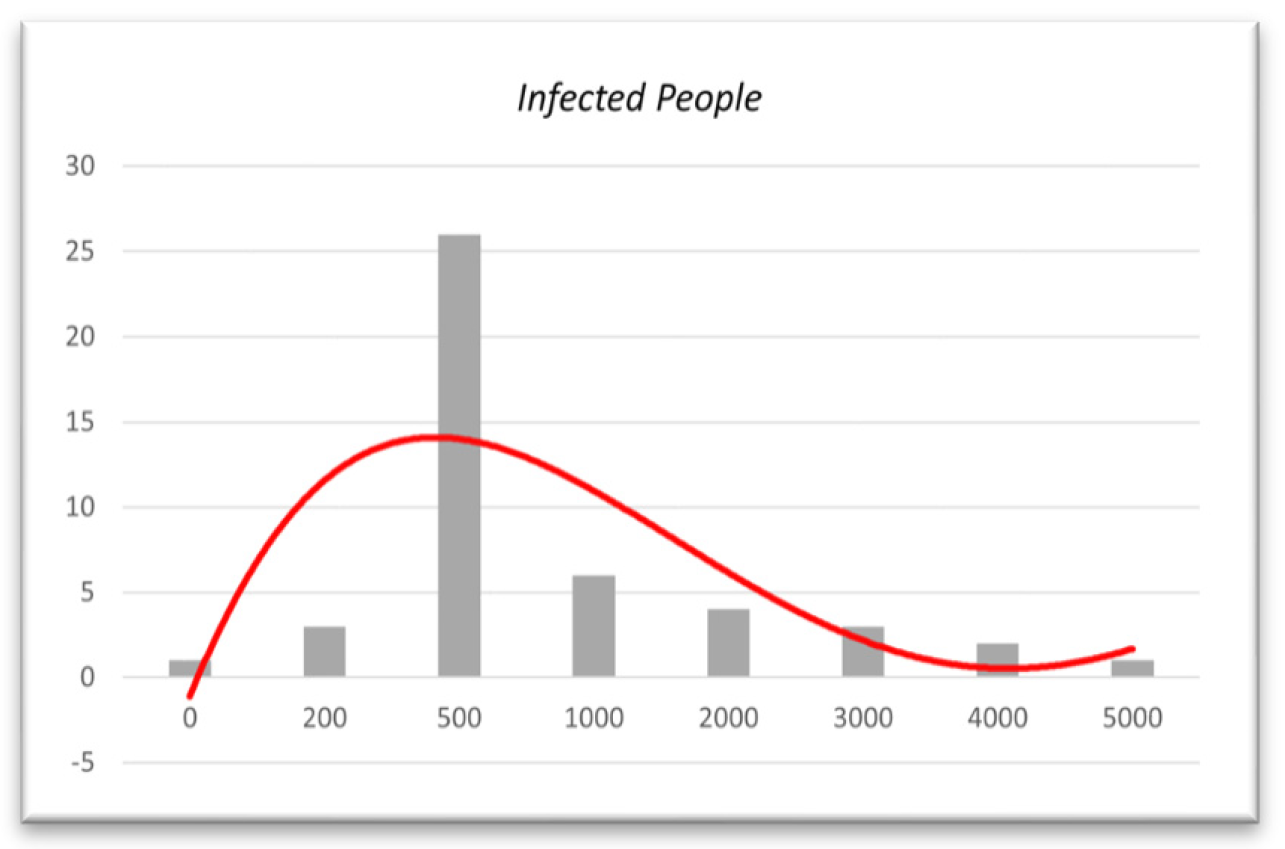

Now, if we look at

Figure 7, we will find that our curve is also showing the same behavior, as we find that after people are fully vaccinated, the curve of the infected is skewed high. Therefore, in

Figure 7, the curve is highly skewed and left-skewed. If we take any random example of a highly skewed curve, we can see some similarity with

Figure 7, as there is a basic example of a highly right-skewed graph.

Figure 12.

Highly skewed graph skewed right.

Figure 12.

Highly skewed graph skewed right.

6.3. Histogram

In general, a histogram is a visual representation that groups a set of data points into user-defined ranges. Our paper focuses on infection rates; thus, we picked the histogram because technical trading analysts employ the MACD histogram.

Using this characteristic of the histogram, we can discover variations in infection rates in our data from

Table 2 that analysts use to suggest changes in momentum. Now that we have attempted to determine the number of sick individuals in various ranges, we discover,

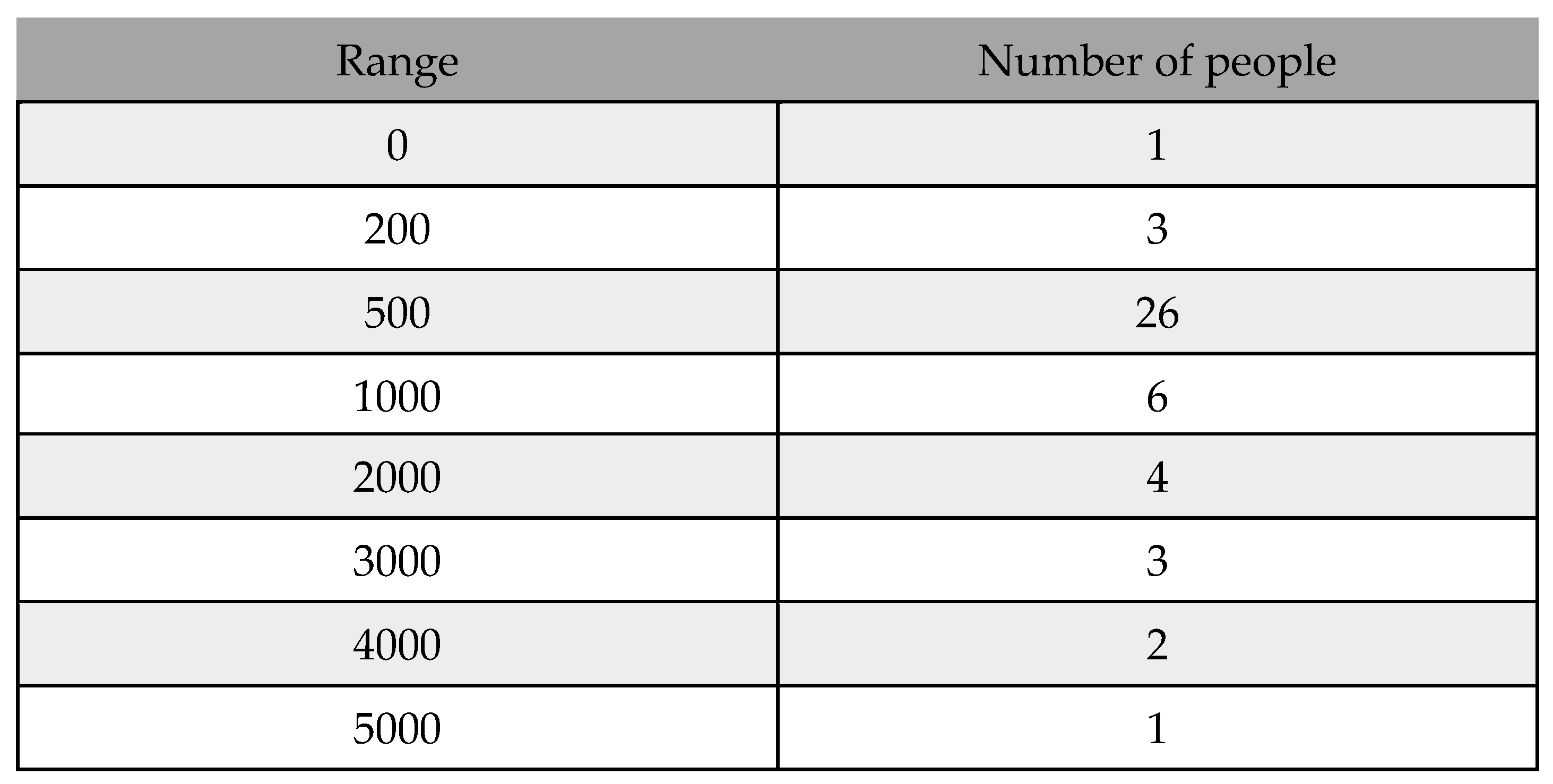

Table 9.

Frequency table from 01/12/21 to 31/01/22.

Table 9.

Frequency table from 01/12/21 to 31/01/22.

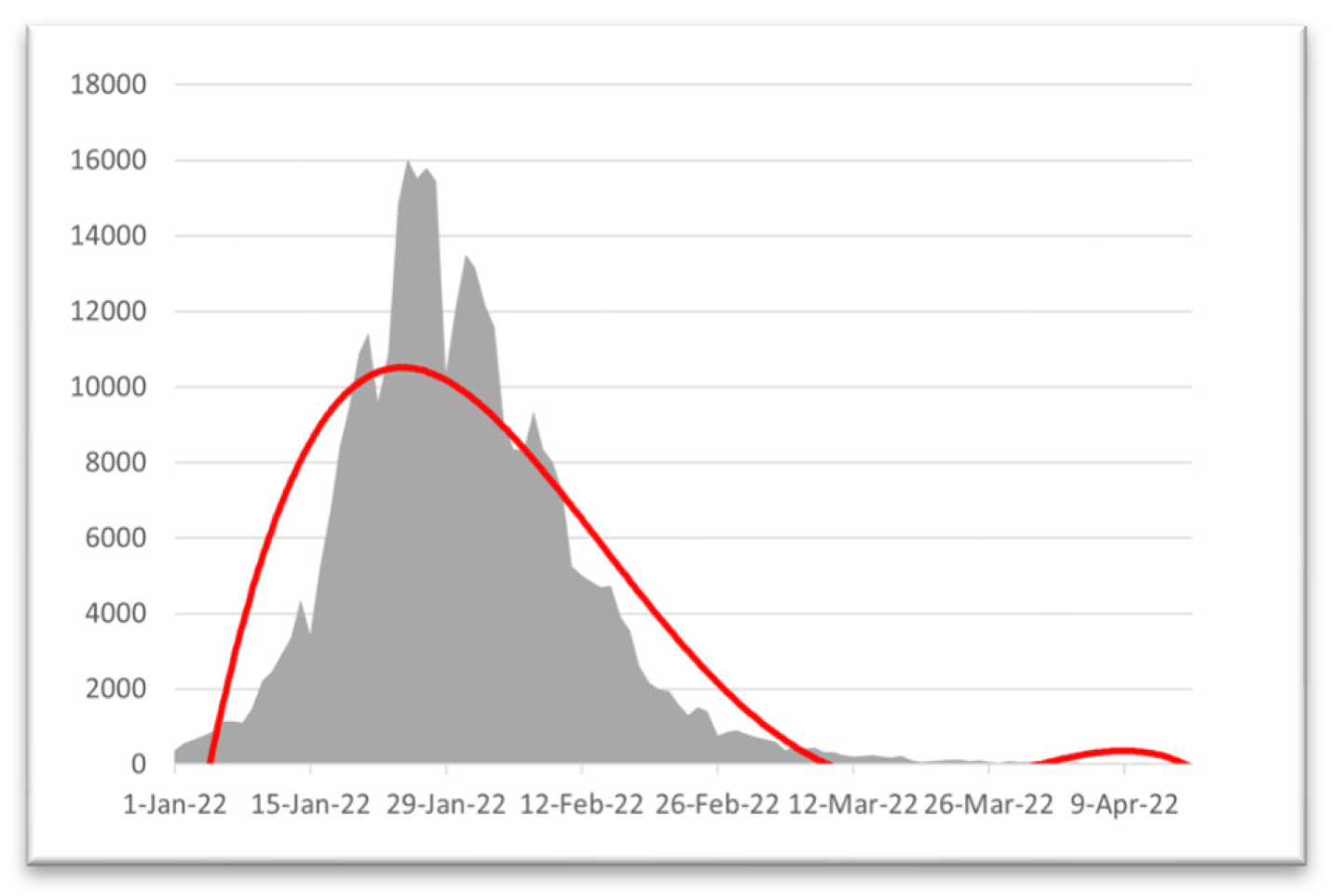

Figure 13.

Histogram based on infected people from 01/12/21 to 31/01/22.

Figure 13.

Histogram based on infected people from 01/12/21 to 31/01/22.

In

Figure 13, as the histogram shows, until January 31, 2022, almost 50% of daily infected people will be between 200 and 1000. Based on the histogram, in mid-December, people were much more infected. However, as the vaccination program simultaneously continued and more people were fully vaccinated, the number of infected people decreased. Additionally, if we look at the histogram from December 1, 2021, to February 28, 2022, we obtain,

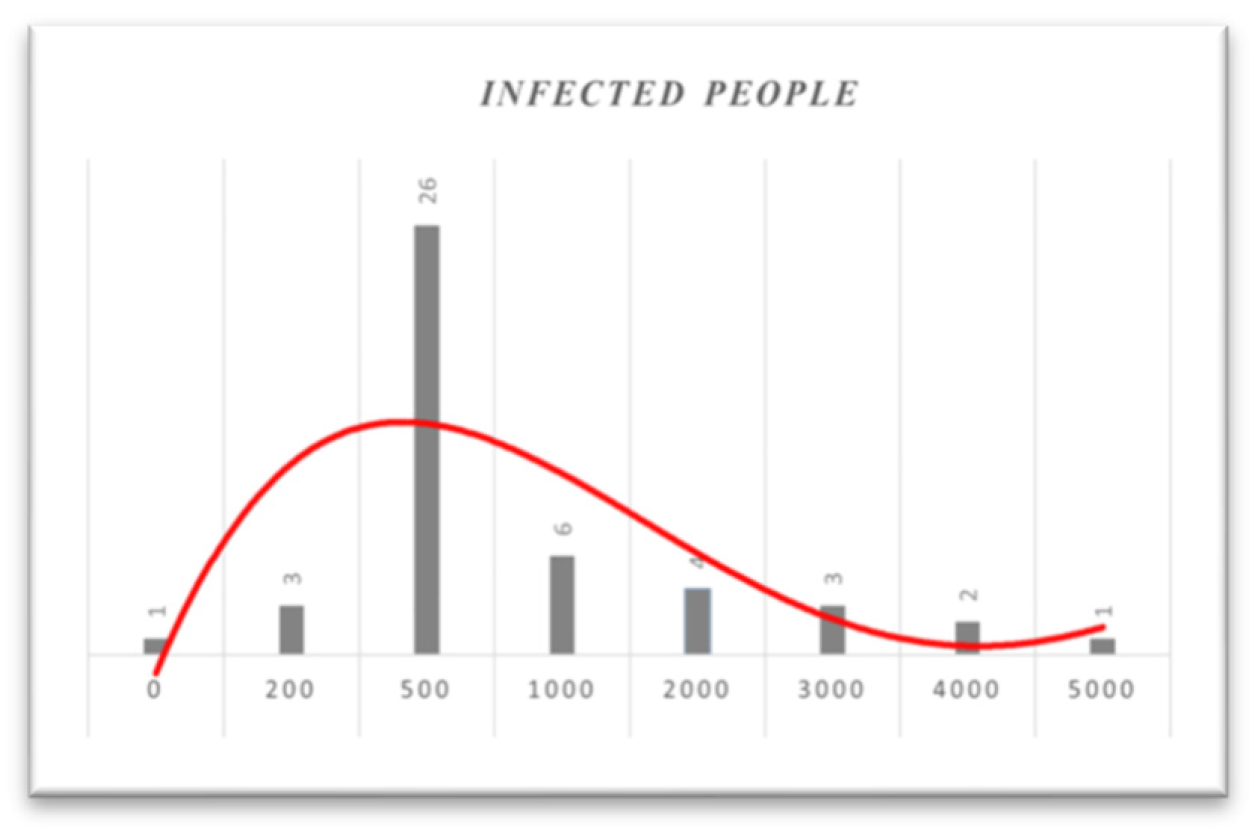

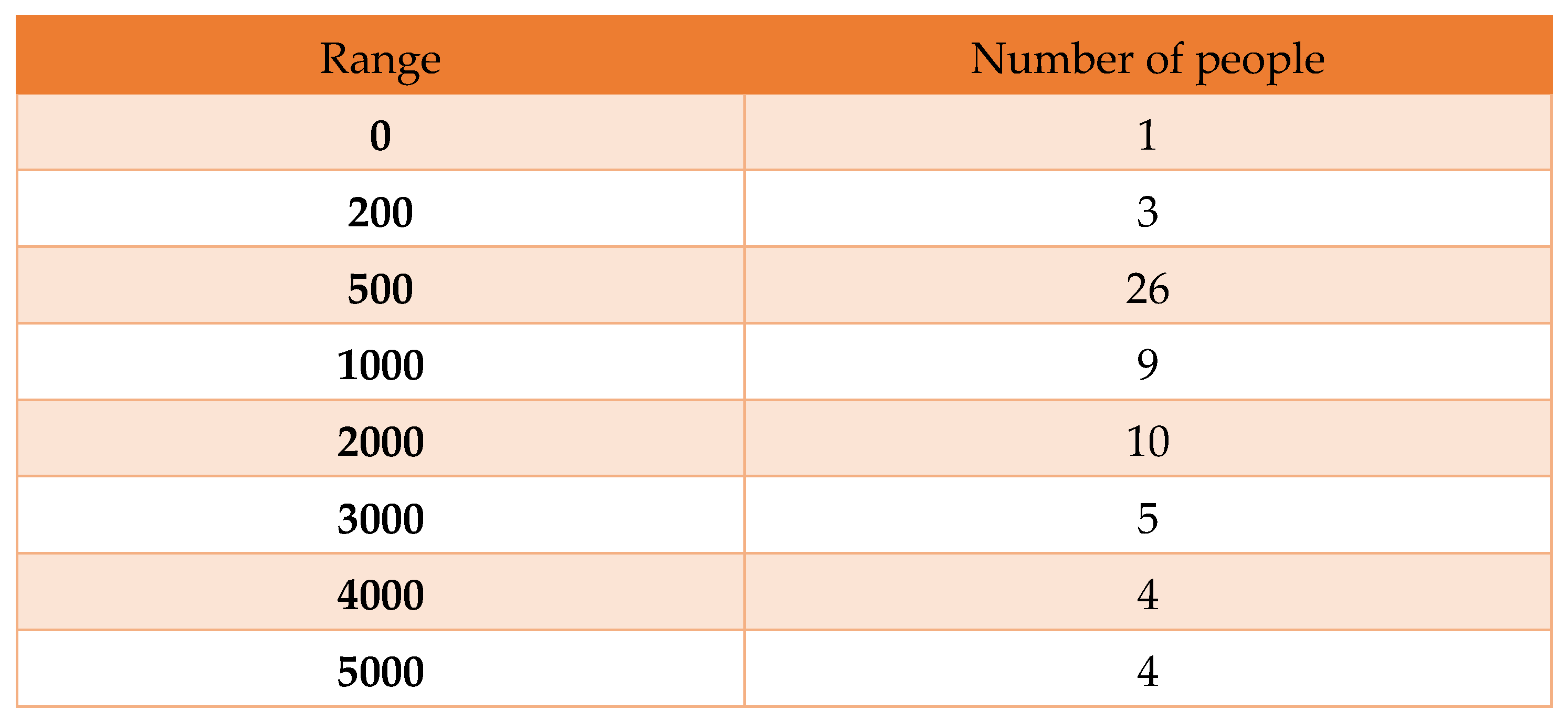

Table 10.

Frequency table from 01/12/21 to 28/02/22.

Table 10.

Frequency table from 01/12/21 to 28/02/22.

Here, we find a histogram that contains 10, 5, and 4 infected people whose daily numbers are greater than one thousand, as shown below:

Figure 14.

Histogram based on infected people from 01/12/21 to 28/02/22.

Figure 14.

Histogram based on infected people from 01/12/21 to 28/02/22.

Here, we can see that the curve goes higher for the daily infected people of 1000 or more in mid-December. In January, the number of infected people decreased by 1000+. Therefore, this histogram also shows the decrease in the infection rate in one month from January 31, 2022, which makes our model more valid.