Submitted:

25 December 2024

Posted:

26 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a class of non-coding RNA molecules with transcripts longer than 200bp, which were initially thought to be noise from genomic transcription without biological function. However, since the discovery of H19 in 1980 and Xist in 1990, increasing evidence has shown that lncRNAs regulate gene expression at epigenetic, transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels through specific regulatory actions, and are involved in the development of cancer and other diseases. Despite lower abundance of lncRNAs than that of protein-coding genes with less sequence conservation, lncRNAs have become an intense area of RNA research. They exert diverse biological functions such as inducing chromatin remodeling, recruiting the transcriptional machinery, acting as competitive endogenous RNAs for microRNAs, and modulating protein-protein interactions. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a developmental process, associated with embryonic development, wound healing, and cancer progression. In the context of oncogenesis, the EMT program is transiently activated and confers migratory/invasive and cancer stem cell (CSC) properties to tumor cells, which are crucial for malignant progression, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance. Accumulating evidence has revealed that lncRNAs play crucial roles in the regulation of tumor epithelial/mesenchymal plasticity (EMP) and cancer stemness. Here, we summarize the emerging roles and molecular mechanisms of lncRNAs in regulating tumor cell EMP and their effects on tumor initiation and progression through regulation of CSCs. We also discuss the potential of lncRNAs as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Major Functions of lncRNAs

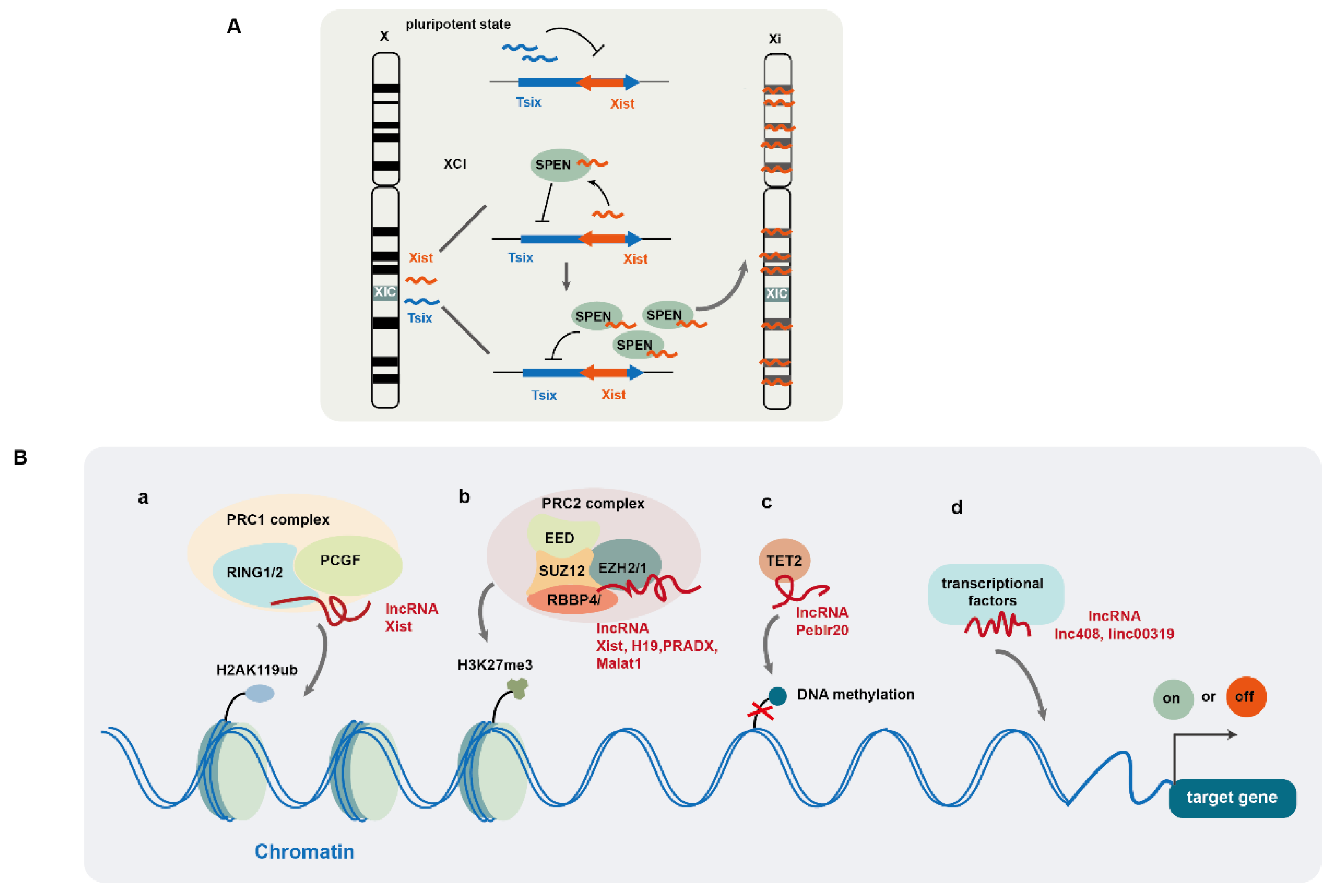

2.1. LncRNA-Mediated Regulation of Gene Expression at Epigenetic and Transcriptional Levels

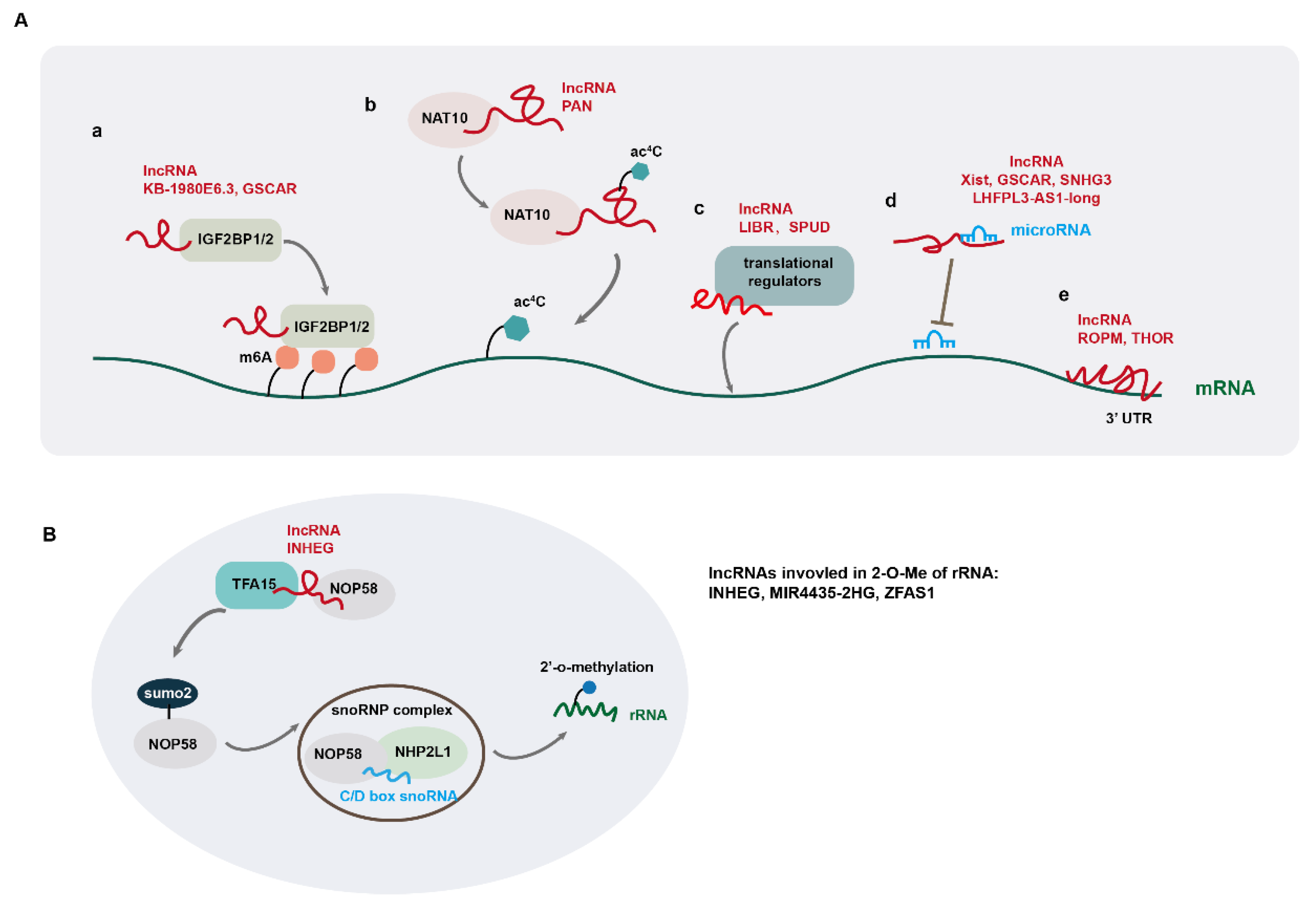

2.2. LncRNA-Mediated Regulation of Gene Expression at Post-Transcriptional Levels

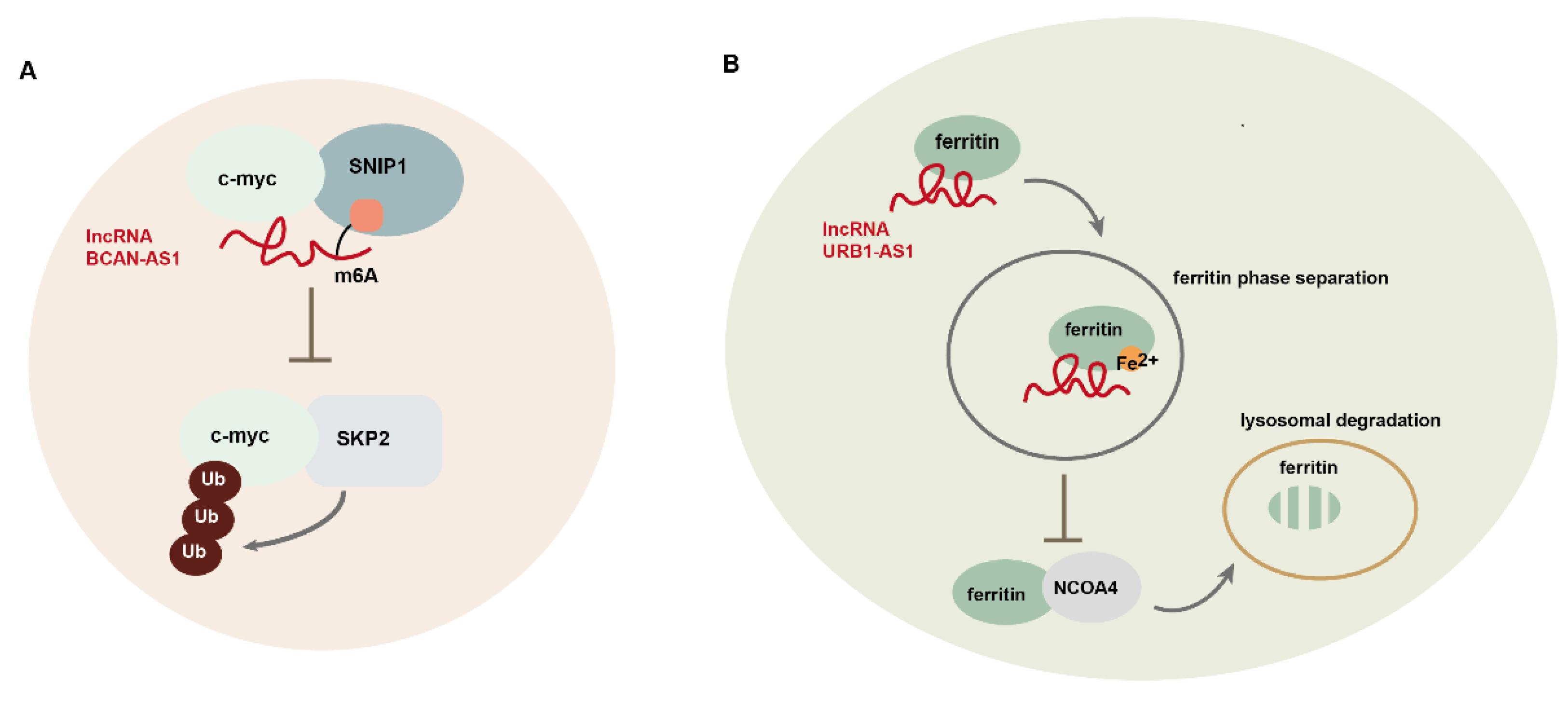

2.3. LncRNA-Mediated Regulation of Gene Expression at Post-Translational Level

3. The Regulatory Roles of lncRNAs in EMP and CSCs

4. LncRNAs in Regulation of EMP-Associated Signaling

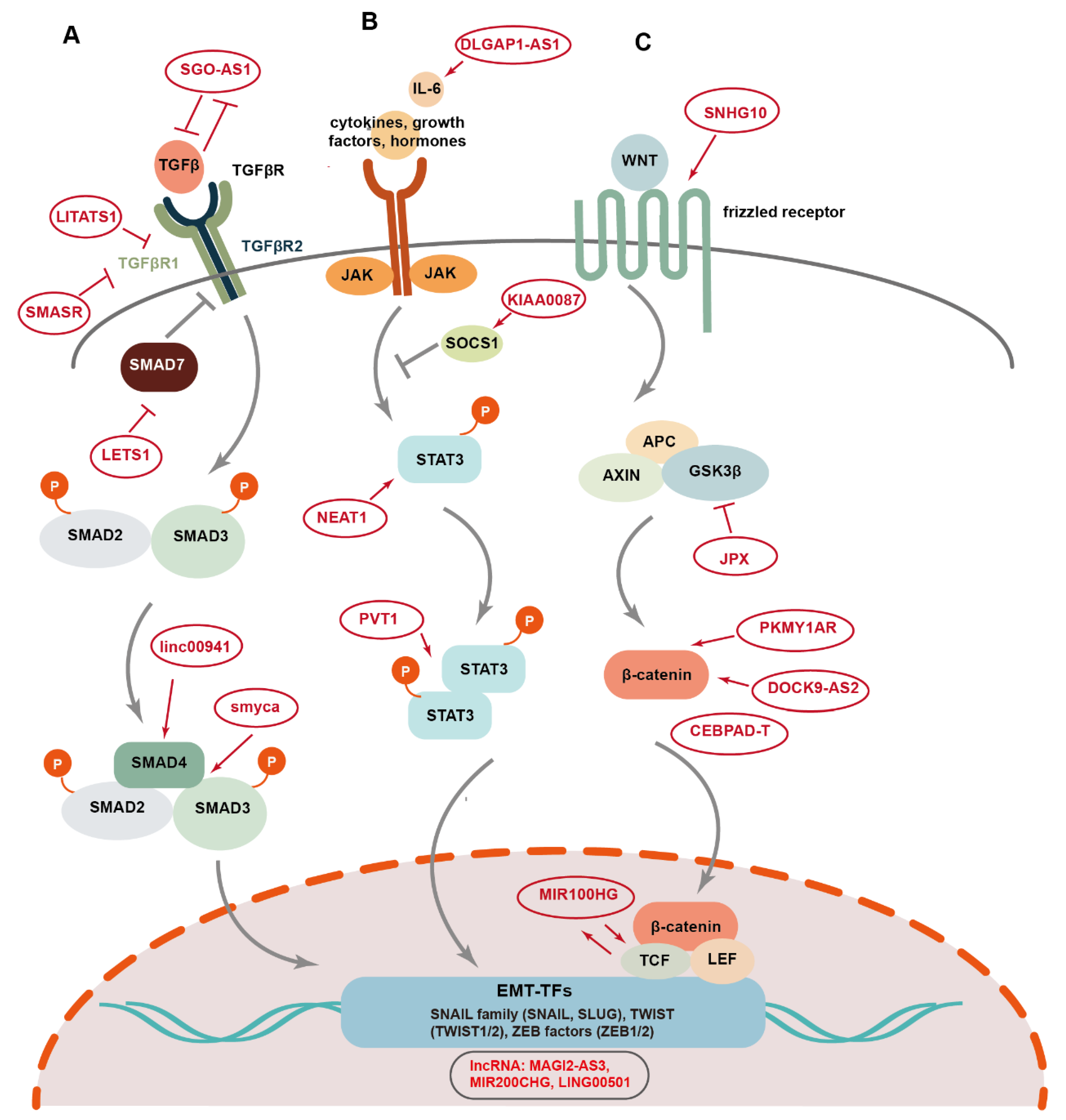

4.1. TGFβ /Smad Pathway

4.2. STAT3 Pathway

4.3. Wnt Pathway

4.4. Other Signaling Pathways

5. Clinical Implications of lncRNAs in Cancer

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iyer, M.K.; Niknafs, Y.S.; Malik, R.; Singhal, U.; Sahu, A.; Hosono, Y.; Barrette, T.R.; Prensner, J.R.; Evans, J.R.; Zhao, S.; et al. The landscape of long noncoding RNAs in the human transcriptome. Nat Genet 2015, 47, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, A.B.; Tsitsipatis, D.; Gorospe, M. Integrated lncRNA function upon genomic and epigenomic regulation. Mol Cell 2022, 82, 2252–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.; Zhang, N.; Wang, T.; Zeng, J.; Li, W.; Han, L.; Yang, M. Super Enhancer-Regulated LncRNA LINC01089 Induces Alternative Splicing of DIAPH3 to Drive Hepatocellular Carcinoma Metastasis. Cancer Res 2023, 83, 4080–4094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, S.; Qin, Y.; Wang, R.; Yang, L.; Zeng, H.; Zhu, P.; Li, Q.; Qiu, Y.; Chen, S.; Liu, Y.; et al. A novel Lnc408 maintains breast cancer stem cell stemness by recruiting SP3 to suppress CBY1 transcription and increasing nuclear beta-catenin levels. Cell Death Dis 2021, 12, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagorac, S.; de Giorgio, A.; Dabrowska, A.; Kalisz, M.; Casas-Vila, N.; Cathcart, P.; Yiu, A.; Ottaviani, S.; Degani, N.; Lombardo, Y.; et al. SCIRT lncRNA Restrains Tumorigenesis by Opposing Transcriptional Programs of Tumor-Initiating Cells. Cancer Res 2021, 81, 580–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Jiang, J.; Huang, Z.; Jin, P.; Peng, L.; Luo, M.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Xie, N.; Gao, W.; et al. Hypoxia-induced lncRNA STEAP3-AS1 activates Wnt/beta-catenin signaling to promote colorectal cancer progression by preventing m(6)A-mediated degradation of STEAP3 mRNA. Mol Cancer 2022, 21, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xiao, B.; Liu, M.; Chen, M.; Xia, N.; Guo, H.; Huang, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, F. N6-methyladenosine-modified oncofetal lncRNA MIR4435-2HG contributed to stemness features of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by regulating rRNA 2'-O methylation. Cell Mol Biol Lett 2023, 28, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wu, W.; Lin, P.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D.; Prager, B.C.; Gimple, R.C.; et al. LncRNA INHEG promotes glioma stem cell maintenance and tumorigenicity through regulating rRNA 2'-O-methylation. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 7526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, M.R.; Ramadei, A.; Doymaz, A.; Varriano, S.; Natelson, D.M.; Yu, A.; Aktas, S.; Mazzeo, M.; Mazzeo, M.; Zakusilo, G.; et al. Long non-coding RNA generated from CDKN1A gene by alternative polyadenylation regulates p21 expression during DNA damage response. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, 11911–11926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Su, J.; Zeng, L.; Deng, S.; Huang, X.; Ye, Y.; Li, R.; Bai, R.; Zhuang, L.; Li, M.; et al. LncRNA BCAN-AS1 stabilizes c-Myc via N(6)-methyladenosine-mediated binding with SNIP1 to promote pancreatic cancer. Cell Death Differ 2023, 30, 2213–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Jin, Z.; Zhai, H.; Liu, B.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chen, M.; Shi, Y.; et al. LncRNA GSCAR promotes glioma stem cell maintenance via stabilizing SOX2 expression. Int J Biol Sci 2023, 19, 1681–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, W.; Jiang, W.; Luo, H.; Tong, Q.; Niu, X.; Liu, X.; Miao, Y.; Wang, J.; Guo, Y.; Li, J.; et al. Long noncoding RNA lncMREF promotes myogenic differentiation and muscle regeneration by interacting with the Smarca5/p300 complex. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, 10733–10755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Sun, W.; Li, J.; Du, R.; Xing, W.; Yuan, X.; Zhong, G.; Zhao, D.; Liu, Z.; Jin, X.; et al. HuR-mediated nucleocytoplasmic translocation of HOTAIR relieves its inhibition of osteogenic differentiation and promotes bone formation. Bone Res 2023, 11, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Liu, N.; Shi, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ouyang, L.; Tam, S.; Xiao, D.; Liu, S.; Wen, F.; et al. A Nuclear Long Non-Coding RNA LINC00618 Accelerates Ferroptosis in a Manner Dependent upon Apoptosis. Mol Ther 2021, 29, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Su, L.; He, X.; Zhao, B.; Miao, J. Long noncoding RNA CA7-4 promotes autophagy and apoptosis via sponging MIR877-3P and MIR5680 in high glucose-induced vascular endothelial cells. Autophagy 2020, 16, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Z.; Lin, H.; Zhu, J.; Liu, L.; Wang, W.; Liu, S.; Liu, W.; Ma, Y.; et al. Self-Recognition of an Inducible Host lncRNA by RIG-I Feedback Restricts Innate Immune Response. Cell 2018, 173, 906–919 e913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Kuang, Z.; Dende, C.; Raj, P.; Quinn, G.; Hu, Z.; Srinivasan, T.; et al. The gut microbiota reprograms intestinal lipid metabolism through long noncoding RNA Snhg9. Science 2023, 381, 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasolo, F.; Jin, H.; Winski, G.; Chernogubova, E.; Pauli, J.; Winter, H.; Li, D.Y.; Glukha, N.; Bauer, S.; Metschl, S.; et al. Long Noncoding RNA MIAT Controls Advanced Atherosclerotic Lesion Formation and Plaque Destabilization. Circulation 2021, 144, 1567–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, P.; Gao, J.; Huang, S.; You, C.; Wang, H.; Chen, P.; Yao, T.; Gao, T.; Zhou, B.; Shen, S.; et al. LncRNA AC006064.4-201 serves as a novel molecular marker in alleviating cartilage senescence and protecting against osteoarthritis by destabilizing CDKN1B mRNA via interacting with PTBP1. Biomark Res 2023, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Niu, H.; Ma, J.; Yuan, B.Y.; Chen, Y.H.; Zhuang, Y.; Chen, G.W.; Zeng, Z.C.; Xiang, Z.L. The molecular mechanism of LncRNA34a-mediated regulation of bone metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cancer 2019, 18, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, E.M.; Rasmussen, T.P. lncRNA involvement in cancer stem cell function and epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. Semin Cancer Biol 2021, 75, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez-Cruz, J.A.; Maldonado, V.; Melendez-Zajgla, J. Regulation of the Cancer Stem Phenotype by Long Non-Coding RNAs. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonawala, K.; Ramalingam, S.; Sellamuthu, I. Influence of Long Non-Coding RNA in the Regulation of Cancer Stem Cell Signaling Pathways. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnet, D.; Dick, J.E. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med 1997, 3, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hajj, M.; Wicha, M.S.; Benito-Hernandez, A.; Morrison, S.J.; Clarke, M.F. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100, 3983–3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takaishi, S.; Okumura, T.; Tu, S.; Wang, S.S.; Shibata, W.; Vigneshwaran, R.; Gordon, S.A.; Shimada, Y.; Wang, T.C. Identification of gastric cancer stem cells using the cell surface marker CD44. Stem Cells 2009, 27, 1006–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, G.; Roz, L.; Perego, P.; Tortoreto, M.; Fontanella, E.; Gatti, L.; Pratesi, G.; Fabbri, A.; Andriani, F.; Tinelli, S.; et al. Highly tumorigenic lung cancer CD133+ cells display stem-like features and are spared by cisplatin treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 16281–16286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Heidt, D.G.; Dalerba, P.; Burant, C.F.; Zhang, L.; Adsay, V.; Wicha, M.; Clarke, M.F.; Simeone, D.M. Identification of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Cancer Res 2007, 67, 1030–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalerba, P.; Dylla, S.J.; Park, I.K.; Liu, R.; Wang, X.; Cho, R.W.; Hoey, T.; Gurney, A.; Huang, E.H.; Simeone, D.M.; et al. Phenotypic characterization of human colorectal cancer stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 10158–10163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cecilia, S.; Zhang, F.; Sancho, A.; Li, S.; Aguilo, F.; Sun, Y.; Rengasamy, M.; Zhang, W.; Del Vecchio, L.; Salvatore, F.; et al. RBM5-AS1 Is Critical for Self-Renewal of Colon Cancer Stem-like Cells. Cancer Res 2016, 76, 5615–5627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, P.; Wang, Y.; Huang, G.; Ye, B.; Liu, B.; Wu, J.; Du, Y.; He, L.; Fan, Z. lnc-beta-Catm elicits EZH2-dependent beta-catenin stabilization and sustains liver CSC self-renewal. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2016, 23, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richart, L.; Picod-Chedotel, M.L.; Wassef, M.; Macario, M.; Aflaki, S.; Salvador, M.A.; Hery, T.; Dauphin, A.; Wicinski, J.; Chevrier, V.; et al. XIST loss impairs mammary stem cell differentiation and increases tumorigenicity through Mediator hyperactivation. Cell 2022, 185, 2164–2183 e2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanojia, D.; Kirtonia, A.; Srujana, N.S.V.; Jeevanandan, S.P.; Shyamsunder, P.; Sampath, S.S.; Dakle, P.; Mayakonda, A.; Kaur, H.; Yanyi, J.; et al. Transcriptome analysis identifies TODL as a novel lncRNA associated with proliferation, differentiation, and tumorigenesis in liposarcoma through FOXM1. Pharmacol Res 2022, 185, 106462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.F.; Chang, C.T.; Hsu, K.W.; Peng, P.H.; Lai, J.C.; Hung, M.C.; Wu, K.J. Epigenetic regulation of asymmetric cell division by the LIBR-BRD4 axis. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, A.W.; Weinberg, R.A. Linking EMT programmes to normal and neoplastic epithelial stem cells. Nat Rev Cancer 2021, 21, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, S.A.; Guo, W.; Liao, M.J.; Eaton, E.N.; Ayyanan, A.; Zhou, A.Y.; Brooks, M.; Reinhard, F.; Zhang, C.C.; Shipitsin, M.; et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell 2008, 133, 704–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskarsson, T.; Batlle, E.; Massague, J. Metastatic stem cells: sources, niches, and vital pathways. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 306–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celia-Terrassa, T.; Kang, Y. Distinctive properties of metastasis-initiating cells. Genes Dev 2016, 30, 892–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, G.; Rath, B. Mesenchymal-Epithelial Transition and Circulating Tumor Cells in Small Cell Lung Cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol 2017, 994, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocana, O.H.; Corcoles, R.; Fabra, A.; Moreno-Bueno, G.; Acloque, H.; Vega, S.; Barrallo-Gimeno, A.; Cano, A.; Nieto, M.A. Metastatic colonization requires the repression of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition inducer Prrx1. Cancer Cell 2012, 22, 709–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaffer, C.L.; Brennan, J.P.; Slavin, J.L.; Blick, T.; Thompson, E.W.; Williams, E.D. Mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition facilitates bladder cancer metastasis: role of fibroblast growth factor receptor-2. Cancer Res 2006, 66, 11271–11278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitoh, M. Transcriptional regulation of EMT transcription factors in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol 2023, 97, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, N.; Jiang, M.; Liu, H.; Chu, Y.; Wang, D.; Cao, J.; Wang, Z.; Xie, X.; Han, Y.; Xu, B. LINC00941 promotes CRC metastasis through preventing SMAD4 protein degradation and activating the TGF-beta/SMAD2/3 signaling pathway. Cell Death Differ 2021, 28, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Fang, S.; Tian, H.; Zhou, C.; Zhao, X.; Tian, H.; He, J.; Shen, W.; Meng, X.; Jin, X.; et al. lncRNA JPX/miR-33a-5p/Twist1 axis regulates tumorigenesis and metastasis of lung cancer by activating Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Mol Cancer 2020, 19, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topel, H.; Bagirsakci, E.; Comez, D.; Bagci, G.; Cakan-Akdogan, G.; Atabey, N. lncRNA HOTAIR overexpression induced downregulation of c-Met signaling promotes hybrid epithelial/mesenchymal phenotype in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cell Commun Signal 2020, 18, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Lu, Y.X.; Liu, F.; Sang, L.; Shi, C.; Xie, S.; Bian, W.; Yang, J.C.; Yang, Z.; Qu, L.; et al. lncRNA BREA2 promotes metastasis by disrupting the WWP2-mediated ubiquitination of Notch1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2023, 120, e2206694120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.Y.; Chan, S.J.; Liu, X.; Wei, A.C.; Jian, R.I.; Huang, K.W.; Lang, Y.D.; Shih, J.H.; Liao, C.C.; Luan, C.L.; et al. Long noncoding RNA Smyca coactivates TGF-beta/Smad and Myc pathways to drive tumor progression. J Hematol Oncol 2022, 15, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Shang, L.; Qiu, Y.; Shen, N.; Wang, J.; Adam, T.; Wei, W.; Song, Q.; Li, J.; et al. LncRNA XIST regulates breast cancer stem cells by activating proinflammatory IL-6/STAT3 signaling. Oncogene 2023, 42, 1419–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wan, H.; Zhang, X. LncRNA LHFPL3-AS1 contributes to tumorigenesis of melanoma stem cells via the miR-181a-5p/BCL2 pathway. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, W.; He, D.; Shan, B.; Wang, J.; Shi, W.; Zhao, W.; Peng, Z.; Luo, Q.; Duan, M.; Li, B.; et al. LINC81507 act as a competing endogenous RNA of miR-199b-5p to facilitate NSCLC proliferation and metastasis via regulating the CAV1/STAT3 pathway. Cell Death Dis 2019, 10, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.T.; Xing, W.; Zhao, R.S.; Tan, Y.; Wu, X.F.; Ao, L.Q.; Li, Z.; Yao, M.W.; Yuan, M.; Guo, W.; et al. HDAC2 inhibits EMT-mediated cancer metastasis by downregulating the long noncoding RNA H19 in colorectal cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2020, 39, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Ramnarine, V.R.; Song, J.H.; Pandey, R.; Padi, S.K.R.; Nouri, M.; Olive, V.; Kobelev, M.; Okumura, K.; McCarthy, D.; et al. The long noncoding RNA H19 regulates tumor plasticity in neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 7349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Zhang, W.; Zhong, L.; Xiao, Y.; Sahoo, S.; Fassan, M.; Zeng, K.; Magee, P.; Garofalo, M.; Shi, L. Long non-coding RNA HIF1A-As2 and MYC form a double-positive feedback loop to promote cell proliferation and metastasis in KRAS-driven non-small cell lung cancer. Cell Death Differ 2023, 30, 1533–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.L.; Liu, Y.N.; Lin, Y.T.; Tsai, M.F.; Wu, S.G.; Chang, T.H.; Hsu, C.L.; Wu, H.D.; Shih, J.Y. LncRNA SLCO4A1-AS1 suppresses lung cancer progression by sequestering the TOX4-NTSR1 signaling axis. J Biomed Sci 2023, 30, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penny, G.D.; Kay, G.F.; Sheardown, S.A.; Rastan, S.; Brockdorff, N. Requirement for Xist in X chromosome inactivation. Nature 1996, 379, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.J.; Ballabio, A.; Rupert, J.L.; Lafreniere, R.G.; Grompe, M.; Tonlorenzi, R.; Willard, H.F. A gene from the region of the human X inactivation centre is expressed exclusively from the inactive X chromosome. Nature 1991, 349, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.T.; Davidow, L.S.; Warshawsky, D. Tsix, a gene antisense to Xist at the X-inactivation centre. Nat Genet 1999, 21, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert-Finestra, T.; Tan, B.F.; Mira-Bontenbal, H.; Timmers, E.; Gontan, C.; Merzouk, S.; Giaimo, B.D.; Dossin, F.; van, I.W.F.J.; Martens, J.W.M.; et al. SPEN is required for Xist upregulation during initiation of X chromosome inactivation. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 7000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerase, A.; Pintacuda, G.; Tattermusch, A.; Avner, P. Xist localization and function: new insights from multiple levels. Genome Biol 2015, 16, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossin, F.; Pinheiro, I.; Zylicz, J.J.; Roensch, J.; Collombet, S.; Le Saux, A.; Chelmicki, T.; Attia, M.; Kapoor, V.; Zhan, Y.; et al. SPEN integrates transcriptional and epigenetic control of X-inactivation. Nature 2020, 578, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvador, M.A.; Wicinski, J.; Cabaud, O.; Toiron, Y.; Finetti, P.; Josselin, E.; Lelievre, H.; Kraus-Berthier, L.; Depil, S.; Bertucci, F.; et al. The histone deacetylase inhibitor abexinostat induces cancer stem cells differentiation in breast cancer with low Xist expression. Clin Cancer Res 2013, 19, 6520–6531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackledge, N.P.; Klose, R.J. The molecular principles of gene regulation by Polycomb repressive complexes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2021, 22, 815–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laugesen, A.; Hojfeldt, J.W.; Helin, K. Molecular Mechanisms Directing PRC2 Recruitment and H3K27 Methylation. Mol Cell 2019, 74, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Zhao, S.; Wang, G.G. Polycomb Gene Silencing Mechanisms: PRC2 Chromatin Targeting, H3K27me3 'Readout', and Phase Separation-Based Compaction. Trends Genet 2021, 37, 547–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Cui, X.; Tan, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xu, C.; Fang, C.; Kang, C. LncRNA PRADX-mediated recruitment of PRC2/DDX5 complex suppresses UBXN1 expression and activates NF-kappaB activity, promoting tumorigenesis. Theranostics 2021, 11, 4516–4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Said, N.H.; Della Valle, F.; Liu, P.; Paytuvi-Gallart, A.; Adroub, S.; Gimenez, J.; Orlando, V. Malat-1-PRC2-EZH1 interaction supports adaptive oxidative stress dependent epigenome remodeling in skeletal myotubes. Cell Death Dis 2021, 12, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pintacuda, G.; Wei, G.; Roustan, C.; Kirmizitas, B.A.; Solcan, N.; Cerase, A.; Castello, A.; Mohammed, S.; Moindrot, B.; Nesterova, T.B.; et al. hnRNPK Recruits PCGF3/5-PRC1 to the Xist RNA B-Repeat to Establish Polycomb-Mediated Chromosomal Silencing. Mol Cell 2017, 68, 955–969 e910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Sun, B.K.; Erwin, J.A.; Song, J.J.; Lee, J.T. Polycomb proteins targeted by a short repeat RNA to the mouse X chromosome. Science 2008, 322, 750–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, R.; Zhao, L.; Ding, Y.; Su, Z.; Li, D.; Zhu, S.; Xu, L.; Zhao, W.; Zhou, W. JMJD6-BRD4 complex stimulates lncRNA HOTAIR transcription by binding to the promoter region of HOTAIR and induces radioresistance in liver cancer stem cells. J Transl Med 2023, 21, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Zhou, J.; Ye, X.; Chen, D.; Chen, W.; Lin, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, B.; Shang, J. A novel lncRNA SNHG29 regulates EP300- related histone acetylation modification and inhibits FLT3-ITD AML development. Leukemia 2023, 37, 1421–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Jia, L.; Wang, Y.; Du, Z.; Zhou, L.; Wen, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, S.; Chen, H.; Chen, N.; et al. Genome-wide interaction target profiling reveals a novel Peblr20-eRNA activation pathway to control stem cell pluripotency. Theranostics 2020, 10, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, C.; Jiang, W.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, X.; Liu, Z.; Ou, H.; Jiang, T.; Liang, W.; et al. LncRNA-AC006129.1 reactivates a SOCS3-mediated anti-inflammatory response through DNA methylation-mediated CIC downregulation in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26, 4511–4528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, L.; Tian, X.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, X.; Li, Q.; Li, W.; Li, S. LINC00319 promotes cancer stem cell-like properties in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma via E2F1-mediated upregulation of HMGB3. Exp Mol Med 2021, 53, 1218–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, P.; He, F.; Hou, Y.; Tu, G.; Li, Q.; Jin, T.; Zeng, H.; Qin, Y.; Wan, X.; Qiao, Y.; et al. A novel hypoxic long noncoding RNA KB-1980E6.3 maintains breast cancer stem cell stemness via interacting with IGF2BP1 to facilitate c-Myc mRNA stability. Oncogene 2021, 40, 1609–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Weng, H.; Sun, W.; Qin, X.; Shi, H.; Wu, H.; Zhao, B.S.; Mesquita, A.; Liu, C.; Yuan, C.L.; et al. Recognition of RNA N(6)-methyladenosine by IGF2BP proteins enhances mRNA stability and translation. Nat Cell Biol 2018, 20, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, B.S.; Zhou, A.; Lin, K.; Zheng, S.; Lu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Sulman, E.P.; Xie, K.; Bogler, O.; et al. m(6)A Demethylase ALKBH5 Maintains Tumorigenicity of Glioblastoma Stem-like Cells by Sustaining FOXM1 Expression and Cell Proliferation Program. Cancer Cell 2017, 31, 591–606 e596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Z.; Ding, X.; Ma, X.; Li, W.; Jia, X.; Gao, S.J.; Lu, C. NAT10-dependent N(4)-acetylcytidine modification mediates PAN RNA stability, KSHV reactivation, and IFI16-related inflammasome activation. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 6327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.M.; Li, S.J.; Yao, Z.T.; Xu, J.J.; Zheng, C.C.; Liu, Z.C.; Ding, P.B.; Jiang, Z.L.; Wei, X.; Zhao, L.P.; et al. N4-acetylcytidine modification of lncRNA CTC-490G23.2 promotes cancer metastasis through interacting with PTBP1 to increase CD44 alternative splicing. Oncogene 2023, 42, 1101–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Luo, R.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, S.; Zeng, X.; Liu, J.; Huang, D.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Luo, M.L.; et al. Long noncoding RNA DIO3OS induces glycolytic-dominant metabolic reprogramming to promote aromatase inhibitor resistance in breast cancer. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 7160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Han, Y.; Cai, H.; Huang, H.; Xuan, Y. Long non-coding RNA SNHG3, induced by IL-6/STAT3 transactivation, promotes stem cell-like properties of gastric cancer cells by regulating the miR-3619-5p/ARL2 axis. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2021, 44, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Jiang, X.; Duan, L.; Xiong, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, P.; Jiang, L.; Shen, Q.; Zhao, S.; Yang, C.; et al. LncRNA PKMYT1AR promotes cancer stem cell maintenance in non-small cell lung cancer via activating Wnt signaling pathway. Mol Cancer 2021, 20, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, W.; Jin, J.; Huang, D.; Fang, H.; Ji, W.; Shi, Y.; Tang, L.; Chen, W.; et al. An androgen receptor negatively induced long non-coding RNA ARNILA binding to miR-204 promotes the invasion and metastasis of triple-negative breast cancer. Cell Death Differ 2018, 25, 2209–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, X.; Wen, C.; Huo, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhan, Q.; Cheng, D.; Chen, H.; Deng, X.; Peng, C.; et al. Long noncoding RNA NORAD, a novel competing endogenous RNA, enhances the hypoxia-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition to promote metastasis in pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer 2017, 16, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wu, S.; Ma, J.; Yan, S.; Xiao, Z.; Wan, L.; Zhang, F.; Shang, M.; Mao, A. lncRNA GAS5 Reverses EMT and Tumor Stem Cell-Mediated Gemcitabine Resistance and Metastasis by Targeting miR-221/SOCS3 in Pancreatic Cancer. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2018, 13, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsushima, K.; Natsume, A.; Ohka, F.; Shinjo, K.; Hatanaka, A.; Ichimura, N.; Sato, S.; Takahashi, S.; Kimura, H.; Totoki, Y.; et al. Targeting the Notch-regulated non-coding RNA TUG1 for glioma treatment. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 13616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Sun, Y.; Hou, Y.; Yang, L.; Wan, X.; Qin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhu, P.; Teng, Y.; et al. A novel lncRNA ROPM-mediated lipid metabolism governs breast cancer stem cell properties. J Hematol Oncol 2021, 14, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.; Xu, Y.; Shi, L.; Xu, T.; Fan, R.; Cao, M.; Xu, W.; Song, J. LncRNA THOR increases the stemness of gastric cancer cells via enhancing SOX9 mRNA stability. Biomed Pharmacother 2018, 108, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Qin, W.; Lu, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Sun, T.; Hu, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; et al. Long noncoding RNA ZFAS1 promoting small nucleolar RNA-mediated 2'-O-methylation via NOP58 recruitment in colorectal cancer. Mol Cancer 2020, 19, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monaco, P.L.; Marcel, V.; Diaz, J.J.; Catez, F. 2'-O-Methylation of Ribosomal RNA: Towards an Epitranscriptomic Control of Translation? Biomolecules 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.P.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, L.M.; Chen, L.K.; Tao, E.X.; Zeng, E.M.; Xu, C.H. Induction of cancer cell stemness in glioma through glycolysis and the long noncoding RNA HULC-activated FOXM1/AGR2/HIF-1alpha axis. Lab Invest 2022, 102, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, S.V.; Rainusso, N.; Liu, M.; Nomura, M.; Patel, T.D.; Nakahata, K.; Kim, H.R.; Huang, S.; Rajapakshe, K.; Coarfa, C.; et al. LncRNA PVT-1 promotes osteosarcoma cancer stem-like properties through direct interaction with TRIM28 and TSC2 ubiquitination. Oncogene 2022, 41, 5373–5384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, L.; Lin, H.; Chen, J.; Song, E.; Luo, M.L. LncRNA NRON promotes tumorigenesis by enhancing MDM2 activity toward tumor suppressor substrates. EMBO J 2023, 42, e112414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Tong, M.; Wong, T.L.; Ng, K.Y.; Xie, Y.N.; Wang, Z.; Yu, H.; Loh, J.J.; Li, M.; Ma, S. Long Noncoding RNA URB1-Antisense RNA 1 (AS1) Suppresses Sorafenib-Induced Ferroptosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma by Driving Ferritin Phase Separation. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 22240–22258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, M.; Wang, Y.; Hou, J.; Zhang, P.; Lv, X.; Su, D.; Jiang, Y.; et al. Multiomics analyses reveal DARS1-AS1/YBX1-controlled posttranscriptional circuits promoting glioblastoma tumorigenesis/radioresistance. Sci Adv 2023, 9, eadf3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, P.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Huang, G.; Liu, B.; Ye, B.; Du, Y.; Gao, G.; Tian, Y.; He, L.; et al. LncBRM initiates YAP1 signalling activation to drive self-renewal of liver cancer stem cells. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 13608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, S.; Chen, Z.; Xu, R.; Li, S.R.; You, L.; Wu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, J.Y.; Xu, X.; et al. LncRNA FAISL Inhibits Calpain 2-Mediated Proteolysis of FAK to Promote Progression and Metastasis of Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2024, e2407493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalluri, R.; Weinberg, R.A. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest 2009, 119, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dongre, A.; Weinberg, R.A. New insights into the mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and implications for cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2019, 20, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.M.; Panzilius, E.; Bartsch, H.S.; Irmler, M.; Beckers, J.; Kari, V.; Linnemann, J.R.; Dragoi, D.; Hirschi, B.; Kloos, U.J.; et al. Stem-cell-like properties and epithelial plasticity arise as stable traits after transient Twist1 activation. Cell Rep 2015, 10, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celia-Terrassa, T.; Meca-Cortes, O.; Mateo, F.; Martinez de Paz, A.; Rubio, N.; Arnal-Estape, A.; Ell, B.J.; Bermudo, R.; Diaz, A.; Guerra-Rebollo, M.; et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition can suppress major attributes of human epithelial tumor-initiating cells. J Clin Invest 2012, 122, 1849–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroger, C.; Afeyan, A.; Mraz, J.; Eaton, E.N.; Reinhardt, F.; Khodor, Y.L.; Thiru, P.; Bierie, B.; Ye, X.; Burge, C.B.; et al. Acquisition of a hybrid E/M state is essential for tumorigenicity of basal breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 7353–7362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruscetti, M.; Quach, B.; Dadashian, E.L.; Mulholland, D.J.; Wu, H. Tracking and Functional Characterization of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Mesenchymal Tumor Cells during Prostate Cancer Metastasis. Cancer Res 2015, 75, 2749–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Ye, X.L.; Xu, J.; Cao, M.G.; Fang, Z.Y.; Li, L.Y.; Guan, G.H.; Liu, Q.; Qian, Y.H.; Xie, D. The lncRNA H19 mediates breast cancer cell plasticity during EMT and MET plasticity by differentially sponging miR-200b/c and let-7b. Sci Signal 2017, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Ye, H.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, J.; Song, Y.; Gao, W.; et al. The long non-coding RNA HOTTIP promotes progression and gemcitabine resistance by regulating HOXA13 in pancreatic cancer. J Transl Med 2015, 13, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Z.; Chen, C.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, W.; Zheng, S.; Ye, H.; Wang, L.; et al. LncRNA HOTTIP modulates cancer stem cell properties in human pancreatic cancer by regulating HOXA9. Cancer Lett 2017, 410, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, K.; Gong, L.; Yang, Q.; Huang, X.; Hong, C.; Ding, M.; Yang, H. Linc-DYNC2H1-4 promotes EMT and CSC phenotypes by acting as a sponge of miR-145 in pancreatic cancer cells. Cell Death Dis 2017, 8, e2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Tillo, E.; Lazaro, A.; Torrent, R.; Cuatrecasas, M.; Vaquero, E.C.; Castells, A.; Engel, P.; Postigo, A. ZEB1 represses E-cadherin and induces an EMT by recruiting the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling protein BRG1. Oncogene 2010, 29, 3490–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyoshi, A.; Kitajima, Y.; Kido, S.; Shimonishi, T.; Matsuyama, S.; Kitahara, K.; Miyazaki, K. Snail accelerates cancer invasion by upregulating MMP expression and is associated with poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2005, 92, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, M.B.; Abel, E.V.; Mayberry, M.M.; Basile, K.J.; Berger, A.C.; Aplin, A.E. TWIST1 is an ERK1/2 effector that promotes invasion and regulates MMP-1 expression in human melanoma cells. Cancer Res 2012, 72, 6382–6392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Hu, X.; She, J.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, X.; Xu, L.; Liu, Y.; Qin, S. LncRNA MAGI2-AS3 Is Regulated by BRD4 and Promotes Gastric Cancer Progression via Maintaining ZEB1 Overexpression by Sponging miR-141/200a. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2020, 19, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Chen, Z.; He, S.; Gong, Y.; He, A.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Fang, D.; Li, X.; et al. Long non-coding RNA SOX2OT promotes the stemness phenotype of bladder cancer cells by modulating SOX2. Mol Cancer 2020, 19, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Huang, C.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, E.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, X.; Huang, H.; Liao, W.; Wang, X. LncRNA MIR200CHG inhibits EMT in gastric cancer by stabilizing miR-200c from target-directed miRNA degradation. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 8141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, R.; Han, L.; Yang, C.; Fang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Liang, C.; Song, J.; Wei, C.; Huang, G.; Zhong, P.; et al. Upregulation of LINC00501 by H3K27 acetylation facilitates gastric cancer metastasis through activating epithelial-mesenchymal transition and angiogenesis. Clin Transl Med 2023, 13, e1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Shao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Fang, F.; Li, P.; Wang, B. LncRNA PCAT1 promotes metastasis of endometrial carcinoma through epigenetical downregulation of E-cadherin associated with methyltransferase EZH2. Life Sci 2020, 243, 117295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Zhang, C.; Chen, G.; Shen, S. Loss of lncRNA SNHG8 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition by destabilizing CDH1 mRNA. Sci China Life Sci 2021, 64, 1858–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, C.; Wang, Q.; Kuipers, T.B.; Cats, D.; Iyengar, P.V.; Hagenaars, S.C.; Mesker, W.E.; Devilee, P.; Tollenaar, R.; Mei, H.; et al. LncRNA LITATS1 suppresses TGF-beta-induced EMT and cancer cell plasticity by potentiating TbetaRI degradation. EMBO J 2023, 42, e112806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Gonzalez-Prieto, R.; Kuipers, T.B.; Vertegaal, A.C.O.; van Veelen, P.A.; Mei, H.; Ten Dijke, P. The lncRNA LETS1 promotes TGF-beta-induced EMT and cancer cell migration by transcriptionally activating a TbetaR1-stabilizing mechanism. Sci Signal 2023, 16, eadf1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Hao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Teng, Y.; Yang, X. TGF-beta/SMAD4-Regulated LncRNA-LINP1 Inhibits Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Lung Cancer. Int J Biol Sci 2018, 14, 1715–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xu, M.; Wang, Z.; Huang, P.; Huang, C.; Chen, Z.; Tang, G.; Zhu, X.; Cai, M.; Qin, S. The EMT-induced lncRNA NR2F1-AS1 positively modulates NR2F1 expression and drives gastric cancer via miR-29a-3p/VAMP7 axis. Cell Death Dis 2022, 13, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zheng, H.; Hou, W.; Bao, H.; Xiong, J.; Che, W.; Gu, Y.; Sun, H.; Liang, P. Long non-coding RNA linc00645 promotes TGF-beta-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition by regulating miR-205-3p-ZEB1 axis in glioma. Cell Death Dis 2019, 10, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavsak, P.; Rasmussen, R.K.; Causing, C.G.; Bonni, S.; Zhu, H.; Thomsen, G.H.; Wrana, J.L. Smad7 binds to Smurf2 to form an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets the TGF beta receptor for degradation. Mol Cell 2000, 6, 1365–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Zhang, K.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, R.; Chen, J.; Du, N.; Xia, Y.; Long, Y.; Gu, Y.; Xu, J.; et al. Long noncoding RNA SGO1-AS1 inactivates TGFbeta signaling by facilitating TGFB1/2 mRNA decay and inhibits gastric carcinoma metastasis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2021, 40, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuong, J.K.; Lin, C.H.; Zhang, M.; Chen, L.; Black, D.L.; Zheng, S. PTBP1 and PTBP2 Serve Both Specific and Redundant Functions in Neuronal Pre-mRNA Splicing. Cell Rep 2016, 17, 2766–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Wang, D.; Li, J.; Wang, Q.; Wo, L.; Zhang, X.; Hu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhan, M.; He, M.; et al. TGFB2-AS1 inhibits triple-negative breast cancer progression via interaction with SMARCA4 and regulating its targets TGFB2 and SOX2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119, e2117988119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Liu, W.; Li, T.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Huang, L.; Wang, Y.; Shao, S.; Liu, X.; Zhan, Q. Long non-coding RNA SMASR inhibits the EMT by negatively regulating TGF-beta/Smad signaling pathway in lung cancer. Oncogene 2021, 40, 3578–3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadrkhanloo, M.; Entezari, M.; Orouei, S.; Ghollasi, M.; Fathi, N.; Rezaei, S.; Hejazi, E.S.; Kakavand, A.; Saebfar, H.; Hashemi, M.; et al. STAT3-EMT axis in tumors: Modulation of cancer metastasis, stemness and therapy response. Pharmacol Res 2022, 182, 106311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, W.; Yang, L.; Chen, C.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; Tian, Y.; Sun, R. Wnt/beta-catenin-driven EMT regulation in human cancers. Cell Mol Life Sci 2024, 81, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, Y.; He, L.; Lai, Z.; Wan, Z.; Chen, Q.; Pan, S.; Li, L.; Li, D.; Huang, J.; Xue, F.; et al. LINC01287/miR-298/STAT3 feedback loop regulates growth and the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition phenotype in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2018, 37, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Jian, Z.; Jin, H.; Wei, X.; Zou, X.; Guan, R.; Huang, J. Long non-coding RNA DLGAP1-AS1 facilitates tumorigenesis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma via the feedback loop of miR-26a/b-5p/IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 and Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, H.; Tao, Y.; Xiao, S.; Li, X.; Fang, K.; Wen, J.; He, P.; Zeng, M. LncRNA KIAA0087 suppresses the progression of osteosarcoma by mediating the SOCS1/JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. Exp Mol Med 2023, 55, 831–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Wu, J.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, W.; Huang, G.; Qin, L. LncRNA PVT1 induces aggressive vasculogenic mimicry formation through activating the STAT3/Slug axis and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in gastric cancer. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2020, 43, 863–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Xiao, J.K.; Xiao, L.; Xu, B.W.; Li, C. The lncRNA NEAT1 promotes the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis of osteosarcoma cells by sponging miR-483 to upregulate STAT3 expression. Cancer Cell Int 2021, 21, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Xi, G. lncRNA SNHG10 Promotes the Proliferation and Invasion of Osteosarcoma via Wnt/beta-Catenin Signaling. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2020, 22, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, W.; Jin, X.; Han, L.; Huang, H.; Ji, Z.; Xu, X.; Tang, M.; Jiang, B.; Chen, W. Exosomal lncRNA DOCK9-AS2 derived from cancer stem cell-like cells activated Wnt/beta-catenin pathway to aggravate stemness, proliferation, migration, and invasion in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Lyu, T.; Li, H.; Liu, C.; Xie, K.; Xu, L.; Li, W.; Liu, H.; Zhu, J.; Lyu, Y.; et al. LncRNA CEBPA-DT promotes liver cancer metastasis through DDR2/beta-catenin activation via interacting with hnRNPC. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2022, 41, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Li, D.; Sun, L.; Qin, H.; Fan, A.; Meng, L.; Graves-Deal, R.; Glass, S.E.; Franklin, J.L.; Liu, Q.; et al. Interaction of lncRNA MIR100HG with hnRNPA2B1 facilitates m(6)A-dependent stabilization of TCF7L2 mRNA and colorectal cancer progression. Mol Cancer 2022, 21, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Pei, M.; Xiao, W.; Liu, X.; Hong, L.; Yu, Z.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, P.; Lin, J.; et al. The HOXD9-mediated PAXIP1-AS1 regulates gastric cancer progression through PABPC1/PAK1 modulation. Cell Death Dis 2023, 14, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Li, C.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Wen, B.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, K.; Yao, J.; Ye, Y.; Hsiao, H.; et al. LncRNAs-directed PTEN enzymatic switch governs epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cell Res 2019, 29, 286–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Yin, Z.; Xu, L.; Liu, H.; Jiang, L.; Liu, S.; Sun, X. Upregulation of LINC01426 promotes the progression and stemness in lung adenocarcinoma by enhancing the level of SHH protein to activate the hedgehog pathway. Cell Death Dis 2021, 12, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, P.; Dasgupta, P.; Hashimoto, Y.; Shiina, M.; Shahryari, V.; Tabatabai, Z.L.; Yamamura, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Saini, S.; Dahiya, R.; et al. A lncRNA TCL6-miR-155 Interaction Regulates the Src-Akt-EMT Network to Mediate Kidney Cancer Progression and Metastasis. Cancer Res 2021, 81, 1500–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, L.; Xiang, Y.; Guo, X.; Lu, J.; Xia, W.; Yu, Y.; Peng, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, G.; Ye, Y.; et al. c-Src activation promotes nasopharyngeal carcinoma metastasis by inducing the epithelial-mesenchymal transition via PI3K/Akt signaling pathway: a new and promising target for NPC. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 28340–28355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Wu, Q.; Fang, H.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Cong, M.; Wang, T.; He, Y.; Ma, C.; et al. Long non-coding RNA NR2F1-AS1 induces breast cancer lung metastatic dormancy by regulating NR2F1 and DeltaNp63. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 5232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, M.; Qin, X.; Zhou, Y.; Li, G.; Liu, Z.; Geng, X.; Yue, H. Long non-coding RNA LINC00665 promotes gemcitabine resistance of Cholangiocarcinoma cells via regulating EMT and stemness properties through miR-424-5p/BCL9L axis. Cell Death Dis 2021, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, C.; Long, Z.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, J.; Qi, F.; Wu, S.; Huang, T. LncARSR sponges miR-129-5p to promote proliferation and metastasis of bladder cancer cells through increasing SOX4 expression. Int J Biol Sci 2020, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Q.; Lin, C.; Peng, M.; Ren, J.; Jing, Y.; Lei, L.; Tao, Y.; Huang, J.; Yang, J.; Sun, M.; et al. Circulating plasma exosomal long non-coding RNAs LINC00265, LINC00467, UCA1, and SNHG1 as biomarkers for diagnosis and treatment monitoring of acute myeloid leukemia. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 1033143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Ma, L.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Guo, Y.; Yu, T.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, L.; Shu, Y. Role of exosomal non-coding RNAs from tumor cells and tumor-associated macrophages in the tumor microenvironment. Mol Ther 2022, 30, 3133–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, F.; Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Yue, X.; Sun, Q. Serum exosomal lncRNA XIST is a potential non-invasive biomarker to diagnose recurrence of triple-negative breast cancer. J Cell Mol Med 2021, 25, 7602–7607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, X.R.; Wu, J.E.; Wu, Y.Y.; Hsiao, S.Y.; Liang, J.L.; Wu, Y.J.; Tung, C.H.; Huang, M.F.; Lin, M.S.; Yang, P.C.; et al. Exosomal long noncoding RNA MLETA1 promotes tumor progression and metastasis by regulating the miR-186-5p/EGFR and miR-497-5p/IGF1R axes in non-small cell lung cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2023, 42, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.B.; Chen, R.; Ren, S.C.; Shi, X.L.; Zhu, Y.S.; Zhang, W.; Jing, T.L.; Zhang, C.; Gao, X.; Hou, J.G.; et al. Prostate cancer antigen 3 moderately improves diagnostic accuracy in Chinese patients undergoing first prostate biopsy. Asian J Androl 2017, 19, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Ren, S.; Chen, R.; Lu, J.; Shi, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Jing, T.; Zhang, C.; Shen, J.; et al. Development and prospective multicenter evaluation of the long noncoding RNA MALAT-1 as a diagnostic urinary biomarker for prostate cancer. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 11091–11102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Ji, J.; Lyu, J.; Jin, X.; He, X.; Mo, S.; Xu, H.; He, J.; Cao, Z.; Chen, X.; et al. A Novel Urine Exosomal lncRNA Assay to Improve the Detection of Prostate Cancer at Initial Biopsy: A Retrospective Multicenter Diagnostic Feasibility Study. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, W.; Lian, J.; Zhang, H.; Yu, B.; Zhang, M.; Wei, F.; Wu, J.; Jiang, J.; Jia, Y.; et al. The lncRNA PVT1 regulates nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell proliferation via activating the KAT2A acetyltransferase and stabilizing HIF-1alpha. Cell Death Differ 2020, 27, 695–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, L.; Wu, Z.; Li, Y.; Xu, Z.; Liu, B.; Liu, F.; Bao, Y.; Wu, D.; Liu, J.; Wang, A.; et al. A feed-forward loop between lncARSR and YAP activity promotes expansion of renal tumour-initiating cells. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 12692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| lncRNA | Cancer type | Action mode | Targets/ interaction partners | Dysregulation in cancer/CSC (up/down) | Roles in tumor development | references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEBPA-DT | HCC | Stabilize mRNA | hnRNPC/DDR2/β-catenin | up | promote EMT and metastasis | 135 |

| linc01287 | HCC | ceRNA | miR-298/STAT3 | up | promote EMT, tumor growth and metastasis | 128 |

| Linc01089 | HCC | Regulate alternative splicing of mRNA | E2F1/LINC01089/hnRNPM/DIAPH3 | up | promote EMT and tumor metastasis | 3 |

| DLGAP1-AS1 | HCC | ceRNA for miR-26a-5p and miR-26b-5p | (miR-26a/b-5p)/IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 | up | facilitate EMT and HCC progression | 129 |

| HOTAIR | HCC | Interact with protein | HOTAIR/c-Met/HOTAIR | down | maintain E/M phenotype of cells to promote metastasis | 45 |

| SGO1-AS1 | GC | Facilitate mRNA degradation | TGFβ/ZEB1/SGO1-AS1/PTBP1/TGFβ | down | prevent EMT and metastasis | 122 |

| PAXIP1-AS1 | GC | Bind to and destabilise protein | HOXD9/PAXIP1-AS1/PABPC1/PAK1 | down | suppress EMT, cell growth and invasion | 137 |

| MAGI2-AS3 | GC | ceRNA | BRD4/MAGI2-AS3/(miR-141/200a)/ZEB1 | up | promote cell migration and invasion | 110 |

| LINC00501 | GC | recruit hnRNPR to slug promoter | hnRNPR/slug | up | promote EMT, metastasis and angiogenesis | 113 |

| mir200CHG | GC | Interact with miR-200c to stabilize it | miR-200c | down | inhibit EMT and lymph nodes metastasis | 112 |

| linc81507 | NSCLC | ceRNA for miR-199b-5p | miR-199b-5p/caveolin1/STAT3 pathway | down | suppress EMT, cell proliferation and migration | 50 |

| HIF1A-As2 | NSCLC | Recruit DHX9 to MYC promoter | KARS/MYC/HIF1A-As2/DHX9/MYC | up | promote EMT, cell proliferation, tumor metastasis and cisplatin-resistance | 53 |

| PKMYT1AR | NSCLC | ceRNA for miR-485-5p; stabilize β-catenin | miR-485-5p/PKMYT1; β-catenin | up | promote EMT, tumor cell migration and CSCs maintenance | 81 |

| NEAT1 | OS | ceRNA for miR-483 | miR-483/NEAT1 | - | promote EMT and metastasis | 132 |

| KIAA0087 | OS | ceRNA for miR-411-3p | miR-411-3p/SOCS1/JAK2/STAT3 pathway | down | suppress EMT, cell growth, migration and invasion, trigger cell apoptosis | 130 |

| SNHG10 | OS | ceRNA for miR-182-5p | miR-182-5p/FZD3 | up | promote the proliferation and invasion of OS cells | 133 |

| JPX | lung cancer | ceRNA for miR-33a-5p | miR-33a-5p/TWIST1 | up | facilitate EMT and tumor growth | 44 |

| SMASR | lung cancer | interact with Smad2/3 cBR1 expression | TGF-β/Smad2/3/SMASR/TGF-β/Smad pathway | down | suppress EMT, migration and invasion of lung cancer cells | 125 |

| MIR100HG | CRC | interact with hnRNPA2B1 to stabilize TCF7L2 mRNA | hnRNPA2B1/TCF7L2 | - | promote EMT, tumor metastasis and cetuximab resistance | 136 |

| H19 | CRC | ceRNA for miR-22-3p | miR-22-3p/MMP14 | - | promote EMT and cancer metastasis | 51 |

| LINC00941 | CRC | Stabilize SMAD4 protein | SMAD4 | up | activate EMT and promote CRC metastasis | 43 |

| SNHG8 | BC | stabilize CDH1 mRNA | ZEB1/SNHG8/CDH1 | down | suppress EMT | 115 |

| LINC00665 | CCA | ceRNA for miR-424-5p | miR-424-5p/BCL9L | up | promote EMT, stemness, migration, invasion and gemcitabine resistance | 143 |

| lncARSR | BCa | ceRNA for miR-129-5p | miR-129-5p/SOX4 | up | enhance EMT, proliferation, migration and invasion of Bca cells | 144 |

| ARNILA | TNBC | ceRNA for miR-204 | miR-204/SOX4 | - | enhance EMT and metastasis | 82 |

| LINC01426 | LUAD | interact with USP22 to stabilize SHH protein | USP22/SHH | up | enhance EMT, stemness and migration | 139 |

| NORAD | PC | ceRNA for hsa-miR-125a-3p | hsa-miR-125a-3p/RhoA | up | enhance the hypoxia-induced EMT and promote metastasis | 83 |

| GAS5 | PC | ceRNA for miR-221 | miR-221/SOCS3 | Down | suppress EMT, stemness, migration and gemcitabine resistance | 84 |

| DOCK9-AS2 | PTC | interact with SP1 and act as ceRNA for miR-1972 | miR-1972/CTNNB1/Wnt/β-catenin | up | promote EMT, stemness, proliferation, migration and invasion | 134 |

| HOTTIP | PDAC | Interact with WDR5 to promote HOXA9 expression | HOTTIP/WDR5/HOXA9/Wnt pathway | up | promote EMT, stemness and cancer progression | 105 |

| SOX2OT | Bladder cancer | ceRNA for miR-200c | miR-200c/SOX2 | up | promote EMT, migration, invasion and stemness phenotype of CSCs | 111 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).