1. Introduction

Maxwell’s equations have long been the foundation for describing electromagnetic phenomena, providing a comprehensive framework for understanding the dynamics of electric and magnetic fields in the presence of charges and currents. These equations are traditionally written as:

In classical electromagnetism, the energy and momentum of fields are described without explicitly considering the quantum properties of light. However, photons, the quanta of the electromagnetic field, carry energy (

E) and momentum (

p) are inherently linked to their wave-like properties. From relativistic and quantum perspectives, these relationships can be expressed as follows:

where

is the wave vector,

ℏ is the reduced Planck’s constant, and

h is Planck’s constant.

These relationships highlight the dual nature of photons as both particles and waves. However, integrating photon effects into classical field equations requires a novel approach, particularly to address how the photon’s momentum (

p) interacts with the electric and magnetic fields. In this work, we propose an extension of Maxwell’s equations by incorporating an effective potential associated with photon momentum. This is achieved by redefining the electric field as:

which leads to a fourth-order differential equation when coupled with relativistic and quantum considerations. By bridging these ideas with the kinetic energy operator in the Hamiltonian, we derive a generalized framework for photon-field interactions. Furthermore, the boundary conditions for the system we re defined using the Lorenz system, enabling us to explore the quasi-stability and chaotic dynamics of these interactions.

The integration of relativistic, quantum, and chaotic perspectives offers new insights into the behavior of electromagnetic fields in the presence of photons, providing a unified approach to understanding photon-field coupling. This study not only extends the applicability of Maxwell’s equations but also contributes to the broader understanding of the interplay between quantum mechanics, relativity, and nonlinear dynamics.

2. Modified Maxwell Equations and Effective Potential

We introduce the concept of an effective potential to incorporate photon effects into an electromagnetic framework. This potential reflects the contribution of photons to the electric field, bridging the quantum nature of photons with the classical dynamics of fields.

2.1. Effective Potential and Field Definitions

In the traditional formulation, the electric field is derived from a scalar potential

as:

In the presence of photons, we redefine the scalar potential to include the photon’s energy-momentum relation. The effective potential is given by:

where

p is the photon momentum and

c is the speed of light. Substituting this into the electric field equation yields:

This modification integrates the photon’s energy directly into the field dynamics. For the magnetic field

, we retain its standard definition in terms of the vector potential

:

2.2. Modifications to Maxwell’s Equations

Using these definitions, Maxwell’s equations are reformulated to include photon effects:

1. Modified Gauss’s Law

Incorporating

, Gauss’s law becomes:

Substituting

, we obtain:

2. Faraday’s Law

The time-dependent magnetic field remains governed by Faraday’s law:

Substituting

:

4. Ampere’s Law with Maxwell’s Correction

Incorporating photon effects, Ampere’s law becomes:

2.3. Fourth-Order Field Equation

We begin with the modified Gauss’s law given by

where

is the charge density distribution. On the other hand, in the Hamiltonian framework the photon’s momentum operator is defined as

and upon squaring it, we obtain

This squared operator plays the role of the kinetic energy term in the Hamiltonian. Now, by incorporating this effective momentum into our modified Gauss’s law—as an effective potential—we write

Recall that the speed of light in vacuum is defined as

so that

, substituting this into the equation and rearranging—by moving factors associated with

and 1/c to maintain dimensional consistency—we obtain:

Notice that the factors of

cancel out, yielding

Defining the constant

the above expression can be written in a compact form as:

This fourth-order field equation encapsulates the combined effects of the modified Gauss’s law and the photon’s momentum operator. The higher-order derivative (

) naturally arises from the squaring of the momentum operator and indicates a more complex spatial behavior in the field

, which may be crucial for capturing finer details of the interaction between the electromagnetic field and the charge distribution.

3. Boundary Conditions and Stability Analysis

The dynamics of the modified fourth-order equation derived in

Section 2 necessitate the establishment of appropriate boundary conditions to ensure consistency and predictability. In this section, we introduce boundary conditions using the Lorenz system, highlighting its role in defining quasi-stable solutions.

3.1. Lorenz System and Boundary Conditions

The Lorenz system, a classic model in chaotic dynamics, is utilized here to impose constraints on the modified Maxwell equations. The governing equations of the Lorenz system are:

where

,

and

are system parameters. To link these equations to the modified fourth-order equation, we redefine the parameters in terms of the physical variables of the field:

3.2. Stability Conditions for Quasi-Stable Solutions

For the fourth-order equation:

to exhibit quasi-stability, the following conditions must be satisfied:

1. ensuring no dynamic changes in the Lorenz variables.

2. Approximate equality of variables:

Under these conditions, the Lorenz system reduces to a steady-state configuration, providing consistent boundary constraints for the modified Maxwell equations.

4. Derivation of the Fourth-Order Equation from the Klein-Gordon Equation

In this section, we derive a fourth-order differential equation starting from the Klein-Gordon equation. The derivation extends the relativistic quantum framework by incorporating higher-order spatial derivatives and source terms, providing a consistent formulation for exploring advanced quantum and electromagnetic interactions. The derived equation is as follows:

where

represents the scalar field,

is the charge density, and

is the permeability of free space. The coefficients

,

,

, and

are defined as:

4.1. Starting from the Klein-Gordon Equation

The Klein-Gordon equation, which describes scalar fields in relativistic quantum mechanics, is given by:

Because the photon particle has no mass, the term

is eliminated from the Klein-Gordon equation, so:

To generalize this framework, we introduce a fourth-order spatial derivative term, given by:

which accounts for finer spatial variations in the field.

4.2. Inclusion of Temporal and Source Terms

To maintain dimensional consistency, the second temporal derivative term is scaled by

:

Additionally, a source term proportional to the charge density

is incorporated, scaled by

.

4.3. Assembling the Fourth-Order Equation

Combining these terms results in the proposed fourth-order equation:

The dimensional consistency of the equation is verified as follows:

The term has dimensions , which matches the dimensions of the source terms on the right-hand side.

The coefficient has dimensions , ensuring compatibility with the second temporal derivative term.

The coefficient has dimensions , aligning with the contribution from charge density.

4.4. Physical Significance

This fourth-order equation introduces the following key physical aspects:

1. Higher-Order Spatial Variations: The term captures additional spatial effects, relevant in high-energy or relativistic regimes.

2. Dynamic Temporal Response: The scaling of the second temporal derivative by reflects relativistic corrections and quantum effects.

3. Source Term Contribution: The term explicitly connects charge density to the scalar field, bridging quantum field theory and Maxwellian electrodynamics.

This derivation extends the Klein-Gordon framework by introducing fourth-order corrections, making it applicable to scenarios involving complex quantum-electromagnetic interactions. The equation remains consistent with dimensional analysis and offers insights into the interplay of higher-order quantum effects and classical electrodynamics.

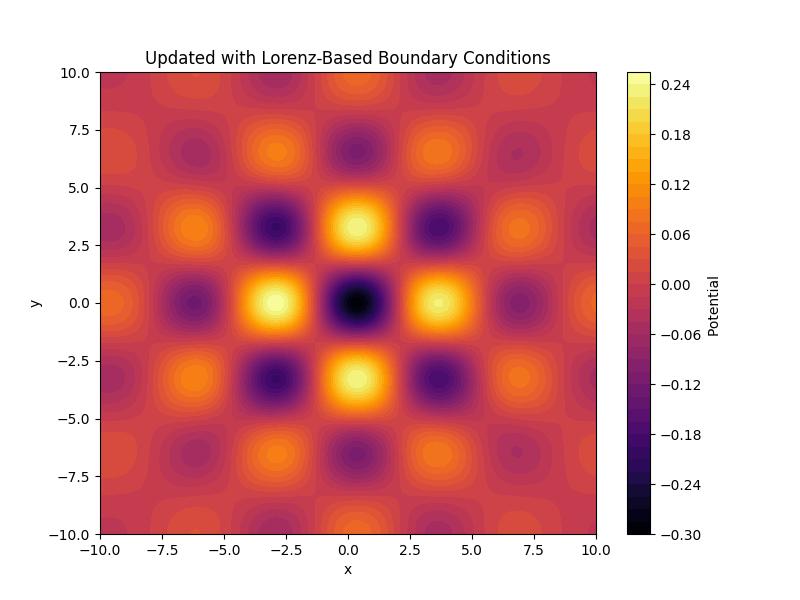

Figure 1.

The figure presents the 2D projections of the 3D trajectories shown in the

Figure 2, focusing on the

X−

Y plane for various boundary conditions in the Lorenz system. Each subplot corresponds to one of the cases depicted earlier.

Figure 1.

The figure presents the 2D projections of the 3D trajectories shown in the

Figure 2, focusing on the

X−

Y plane for various boundary conditions in the Lorenz system. Each subplot corresponds to one of the cases depicted earlier.

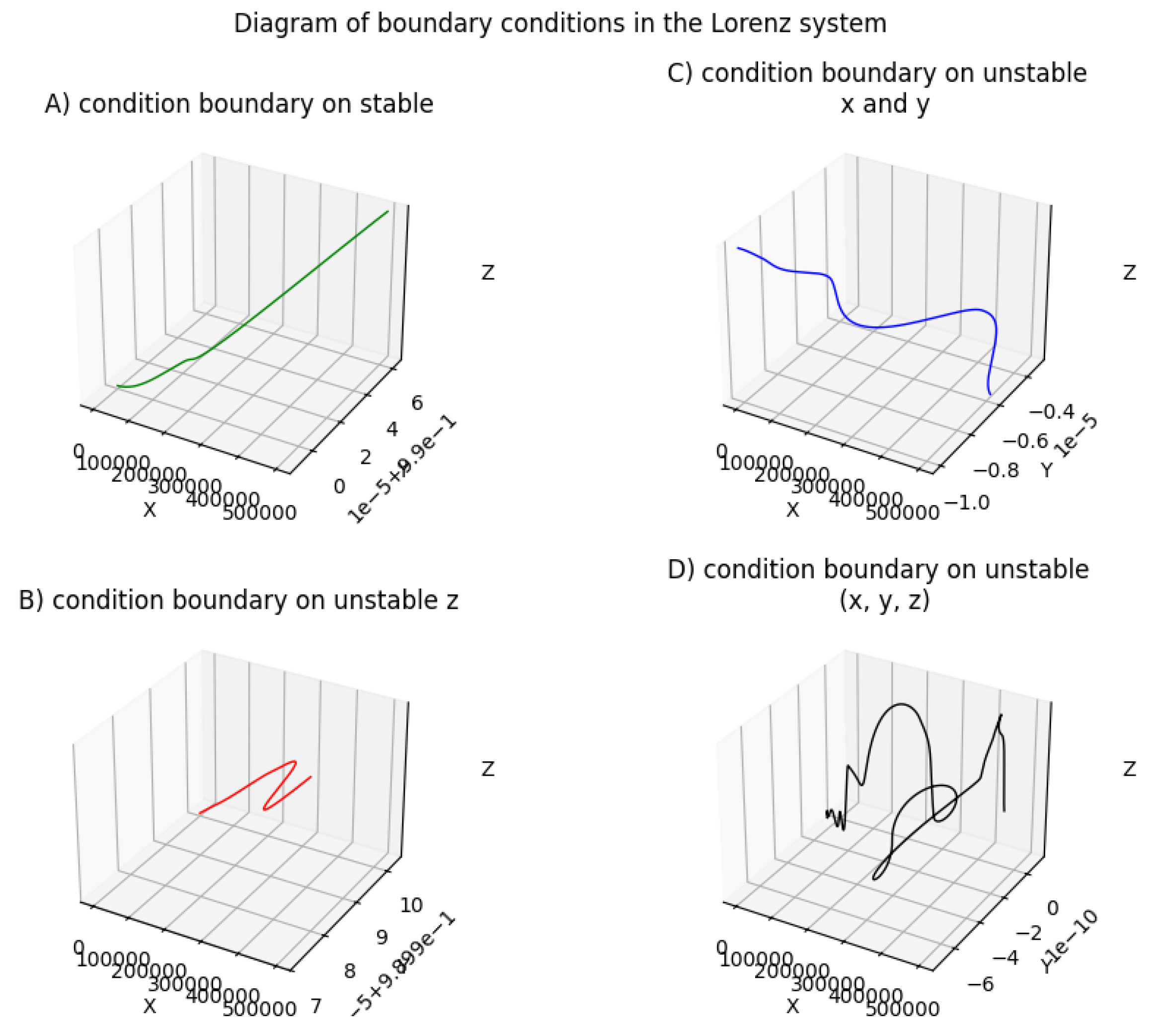

Figure 2.

Two-dimensional projections of the boundary conditions in the Lorenz system under various scenarios of stability and instability. Panel (A) shows the stable behavior, while panels (B), (C), and (D) highlight different forms of instability in the boundary conditions.

Figure 2.

Two-dimensional projections of the boundary conditions in the Lorenz system under various scenarios of stability and instability. Panel (A) shows the stable behavior, while panels (B), (C), and (D) highlight different forms of instability in the boundary conditions.

4.5. Implications of Boundary Conditions

The application of the Lorenz system as a basis for boundary conditions introduces a novel perspective on the interplay between chaotic dynamics and relativistic quantum fields. By linking chaotic variables to the behavior of the photon-field system, the analysis highlights the sensitivity of stability to parameter relationships and initial conditions. The resulting quasi-stable solutions offer a bridge between deterministic higher-order equations and the inherent unpredictability of chaotic systems, enriching our understanding of non-linear and relativistic effects in photon-field interactions.

5. Distinguishing Virtual and Real Photons in a Chaotic Framework

This section introduces a method for differentiating between virtual and real photons within the context of a chaotic electromagnetic system. By integrating the chaotic dynamics into the modified Maxwell framework, the model not only captures the interaction between photons and charge density but also reveals key signatures that help in distinguishing their natures.

5.1. Identification Criteria

-

Real Photons:

These are characterized as observable carriers of electromagnetic energy. They satisfy the on-shell condition, where energy and momentum adhere to the relation . In the modified equations, the effective potential naturally incorporates the dynamics of real photons, reflecting steady, quasi-stable field configurations. The system’s stability, as dictated by the Lorenz-based boundary conditions, further supports the persistence of real photon modes under suitable parameter regimes.

-

Virtual Photons:

In contrast, virtual photons appear as transient intermediates during photon-mediated interactions and do not strictly satisfy the on-shell condition. Their presence is inferred from rapid fluctuations and localized disturbances in the field, which are captured by the higher-order spatial derivatives of the fourth-order differential equation. The chaotic nature of the boundary conditions, particularly when the system deviates from quasi-stability, highlights the short-lived, off-shell contributions of virtual photons.

5.2. Role of Chaotic Dynamics

The integration of chaotic dynamics via the Lorenz system not only refines the boundary conditions but also creates a dynamic landscape where the stability of photon interactions can be assessed. In regions where the chaotic variables approach steady-state, the electromagnetic field predominantly exhibits characteristics of real photon propagation. Conversely, when the system experiences instability or rapid variations in the Lorenz parameters, the model indicates an enhanced contribution from virtual photon interactions.

6. Comparison with QED

The fourth-order differential equation developed in this study finds conceptual parallels with

Quantum Electrodynamics (QED), which rigorously describes the interaction of photons with charged particles. The foundation of QED lies in its

action, expressed as:

where the Lagrangian density is given by:

Here:

: Electromagnetic field strength tensor, describing the field’s dynamics.

: Electromagnetic four-potential.

: Dirac spinor for charged particles.

: Mass of the charged particle.

: Covariant derivative coupling the particle to the electromagnetic field.

-

: Gamma matrices used in relativistic quantum mechanics.

The QED action combines the dynamics of electromagnetic fields with the quantum behavior of particles, illustrating how photons mediate interactions.

Photon-Field Interactions in Advanced Theoretical Contexts

1.

Enhanced Representation of Photon Dynamics In Quantum Electrodynamics (QED), photons are the mediators of electromagnetic interactions, encapsulating dual wave-particle characteristics. The fourth-order equation proposed in this study integrates photon dynamics into the electric field by introducing an effective framework based on photon momentum

p and its relationship with energy

E:

This approach extends traditional QED formulations by embedding spatial derivatives that capture high-intensity and non-local photon effects, without relying on assumptions tied to massive particles.

2. Refined Concept of Effective Potential

The effective potential introduced in this framework parallels interaction terms in the QED Lagrangian, such as

. For photons, this effective potential reflects their energy-momentum dynamics and interaction with electromagnetic fields through:

This formulation bridges photon-mediated interactions with nonlinear dynamics and localized field effects, emphasizing their unique role in high-intensity electromagnetic phenomena.

3. Exploration of Higher-Order Field Dynamics

Traditional QED relies on first-order differential equations derived from Maxwell’s framework. In contrast, the fourth-order equations derived in this study open avenues to explore advanced effects, including photon-photon interactions and complex nonlinearities in strong-field regimes. These equations act as higher-order corrections to the QED action, broadening the theoretical landscape for relativistic field interactions.

4. Integration of Chaotic Dynamics into Boundary Conditions

While QED often assumes linear boundary conditions dictated by charge distributions or external fields, this study introduces the Lorenz system to define dynamic and chaotic boundary constraints. By linking chaotic variables to the photon-field system, the framework accommodates non-equilibrium conditions and fluctuating charge distributions, providing deeper insights into the stability of relativistic quantum fields.

5. Unified Relativistic and Quantum Framework

The fourth-order framework integrates relativistic momentum p and quantum operators , while also incorporating time-dependent dielectric properties and chaotic systems. This holistic approach expands the understanding of photon-field interactions beyond QED by addressing nonlinear, relativistic, and chaotic influences, thereby offering a robust model for examining complex electromagnetic phenomena.

Summary of Comparison

The proposed framework aligns conceptually with QED’s principles by maintaining the photon-field coupling’s quantum and relativistic nature. However, it extends these principles by integrating chaotic systems and higher-order derivatives, which are not traditionally addressed in QED. This study serves as a complementary perspective, potentially useful in understanding non-linear, non-equilibrium, or intense-field phenomena. Further exploration of its implications within the QED action framework could enhance the theoretical underpinnings of both models.

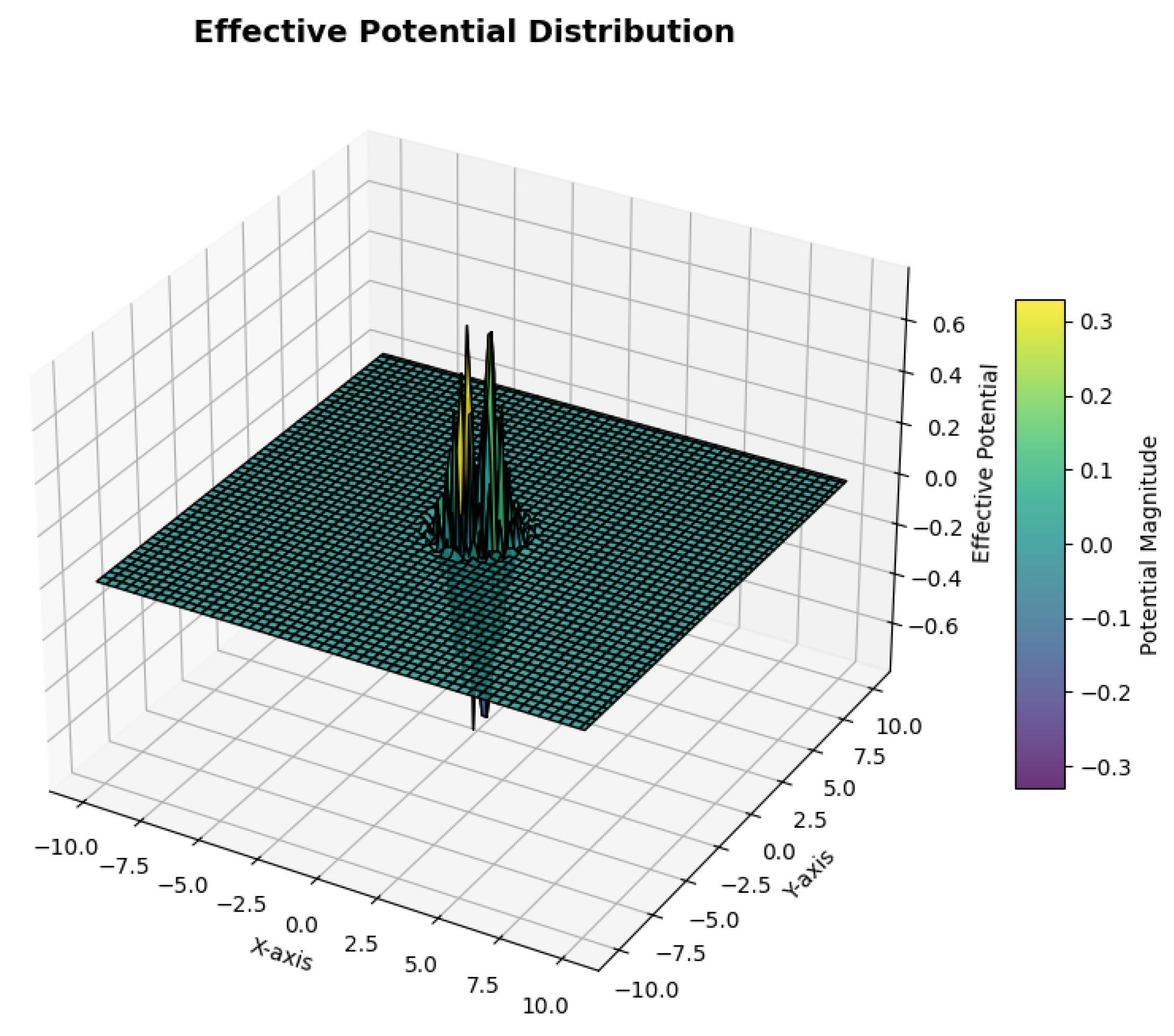

Figure 3.

Here is a 3D visualization of the effective potential distribution, modeled as a Gaussian function to reflect localized field interactions with radial symmetry. The spatial coordinates illustrate how the potential decays smoothly from the center, indicating diminishing interaction strength at larger distances. This representation highlights the interplay between localized field behavior and stability conditions under the imposed Lorenz-system-based boundary constraints.

Figure 3.

Here is a 3D visualization of the effective potential distribution, modeled as a Gaussian function to reflect localized field interactions with radial symmetry. The spatial coordinates illustrate how the potential decays smoothly from the center, indicating diminishing interaction strength at larger distances. This representation highlights the interplay between localized field behavior and stability conditions under the imposed Lorenz-system-based boundary constraints.

7. Conclusions and Applications

Based on the derived equations and simulations, it is evident that if a photon interacts with a charge density, it alters the stability of the system. This interaction highlights the coupling between photons and fields, offering a deeper understanding of photon-field dynamics. These insights pave the way for further exploration into the interplay of quantum effects and field behavior under relativistic and chaotic conditions. The implications of this study extend to various fields:

1. Quantum Optics:

Enhancing the understanding of photon interactions in complex media, contributing to advancements in light-matter interaction models.

2. Photonics and Nano-Technology:

Informing the design of highly sensitive photonic devices, such as quantum sensors and optical circuits, that leverage photon-field dynamics.

3. Astrophysics and Cosmology:

Providing theoretical frameworks for understanding radiation interactions in high-energy astrophysical phenomena, such as pulsars and black hole accretion disks.

4. Fundamental Physics:

Offering a new perspective on stability and chaos in relativistic quantum systems, which could influence further developments in quantum electrodynamics (QED). This multifaceted approach underscores the importance of understanding photon-field interactions, opening new avenues for both theoretical research and practical applications.

The proposed modifications to Maxwell’s equations integrate selected elements of classical electromagnetic theory to derive a novel framework in quantum mechanics, specifically tailored to analyze photon-field interactions. By deriving a fourth-order differential equation, this study extends classical concepts to capture phenomena unique to quantum regimes. These higher-order derivatives encapsulate rapid and nonlinear variations in field behavior, enabling the examination of photon-field interactions under intense and non-equilibrium conditions. The chaotic boundary conditions based on the Lorenz system provide a robust mechanism to explore the stability and quasi-stability of these complex systems.

This extended framework reveals profound insights into photon-mediated interactions, such as photon-photon scattering, field instabilities, and high-frequency electromagnetic modes. It also addresses scenarios where conventional approaches fail to predict field behavior accurately, particularly under strong-field and relativistic regimes. Furthermore, by uniting quantum, relativistic, and chaotic perspectives, the study enriches the theoretical foundation of photon-field dynamics, offering new directions for investigating high-energy astrophysical phenomena, quantum optics, and advanced photonic technologies. Future research can leverage this approach to enhance both the fundamental understanding and practical applications of nonlinear, high-intensity electromagnetic fields.

References

- JP. C. Mbagwu1, Z. L. Abubakar, J. O. Ozuomba1.

- J. D. Jackson, Classical Electrodynamics, 3rd Edition, Wiley - 1998.

- R. P. Feynman, Quantum Electrodynamics, Addison-Wesley - 1961.

- W. Greiner, Relativistic Quantum Mechanics: Wave Equations, Springer - 2000.

- S. H. Strogatz, Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos: With Applications to Physics, Biology, Chemistry, and Engineering, Westview Press - 2014.

- E. N. Lorenz, Deterministic Nonperiodic Flow, Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences - 1963.

- H. Kleinert, Path Integrals in Quantum Mechanics, Statistics, Polymer Physics, and Financial Markets, World Scientific, 4th Edition - 2009.

- B. E. A. Saleh and M. C. Teich, Fundamentals of Photonics, Wiley, 2nd Edition - 2007.

- P. A. M. Dirac, The Principles of Quantum Mechanics, Oxford University Press, 4th Edition - 1958.

- L. D. Landau and E. M. Lifshitz, Quantum Electrodynamics, Pergamon Press - 1982.

- C. Itzykson and J.-B. Zuber, Quantum Field Theory, McGraw-Hill - 1980.

- J. A. Wheeler and R. P. Feynman, Interaction with the Absorber as the Mechanism of Radiation, Reviews of Modern Physics - 1945.

- E. Witten, Quantum Field Theory and the Jones Polynomial, Communications in Mathematical Physics - 1989.

- G. ’t Hooft, Dimensional Regularization and Renormalization, Nuclear Physics B - 1972.

- S. Weinberg, The Quantum Theory of Fields, Vol. 1, Cambridge University Press - 1995.

- V. B. Berestetskii, E. M. V. B. Berestetskii, E. M. Lifshitz, and L. P. Pitaevskii, Quantum Electrodynamics, Butterworth-Heinemann - 1982.

- K. Huang, Quantum Field Theory: From Operators to Path Integrals, Wiley - 2010.

- T. D. Lee, Particle Physics and Introduction to Field Theory, Harwood Academic Publishers - 1981.

- Wiseman, H. M., & Milburn, G. J. Quantum Measurement and Control Cambridge University Press - 2014.

- Kaplan, A. E. & Mehta, P. "Quantum chaos in photonic systems." Physical Review A, 88(3), 032104 - 2013.

- Gharibyan, H. , et al. "Distinguishing real and virtual photons in strongly coupled light–matter systems." Journal of Modern Optics, 61(12), 1058–1070 - 2014.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).