1. Introduction

In recent years, unmanned surface vehicles (USVs), as marine unmanned equipment, have received widespread attention and applications in military and civilian fields, such as marine resource exploration [

1], maritime attack and defense [

2], water quality monitoring [

3], maritime rescue [

4], and maritime mapping [

5]. On the one hand, with the rapid development of wireless sensor network technology [

6], microelectronics technology [

7], internet of things technology [

8] and advanced control theory [

9], the functions of the USVs are greatly expanded and the level of automation is increasing day by day. On the other hand, the adoption of the aforementioned technologies in the USV industry, in particular the introduction of communication networks, brings new challenges to the design of the USV control system. Since the communication network serves as a bridge to integrate various control devices into a whole, control signals and feedback signals are transmitted via the network, so the USV control system represents a standard cyber-physical system (CPS). It is well known that time delay exists widely in CPS, which not only increases the difficulty of control design but also degrades the control performance of the system and even causes the control system to lose stability [

10]. Therefore, for a special CPS such as the USV, the trajectory tracking control issue associated with time-varying communication delays is worthwhile to pay attention to.

Trajectory tracking control plays an important role in the engineering application of the USV, which ensures that the USV sails along the desired trajectory in order to fulfill given tasks. Numerous control technologies have been introduced into USV trajectory tracking control, and fruitful results have been reported. Sliding mode variable structure control ( i.e., sliding mode control, SMC) [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15] is a frequently used strategy because it is insensitive to unknown disturbances and parameter disturbances and is very effective for USVs with nonlinear dynamic characteristics. However, the SMC can effectively handle trajectory tracking to a certain extent, its inherent switching characteristic will cause system chattering, which will further lead to excessive wear and shorten the life of the actuator. To overcome the negative effects of the SMC mentioned above, some improved schemes on the basis of SMC are proposed. For instance, the Super-Twisting SMC is proposed by Liu to solve the trajectory tracking control of USV in literature [

16], with the help of Super-Twisting technology, the chattering effect caused by SMC is reduced. The more studies of the Super-Twisting SMC for the USV tracking control can be found in [

17,

18,

19]. Another well-liked alternative is the adaptive control scheme [

20,

21], which is introduced into SMC and has good a ability to suppress chattering. In [

20], the authors design an adaptive sliding mode controller to achieve surge velocity and heading tracking, and thus finally achieve accurate trajectory tracking of the USV by combining a LOS guidance algorithm. From the above discussion, it is shown that the adaptive control approach introduced into the sliding mode controller simultaneously mitigates chattering and is robust to bounded uncertainties/disturbances. Additionally, the trajectory tracking control of the USV can also be realized through the other control strategies such as model-free control [

22], robust control [

23], fuzzy control [

24], reinforcement learning control [

25], model predictive control [

26] and backstepping control [

27]. It should be noted that the controller of the USV is usually digital, thus, a discrete-time controller is more attractive. Studies related to the application of discrete-time control design are given in the literature [

28,

29,

30]. Although the aforementioned control methods can effectively address the USV trajectory tracking control problem, the time-varying delay has yet to be taken into account, and there is rare study in this field.

In order to overcome the negative effects of time-varying delays, two major types of control strategies have been proposed, namely the passive compensation strategies and the active compensation strategies. The core idea of passive compensation is to use Lyapunov stability theory to construct the Lyapunov function of the control system [

31,

32]. since this approach focuses more on the stability of the control system, it inevitably makes a compromise between control performance and stability [

33]. From the above perspective, the control design of the system is naturally conservative, which means that control performance will be sacrificed to satisfy the stability of the system. For the active compensation strategy, the main study of that is predictive control technology. Predictive control technology is based on a model prediction scheme, which is an optimal control strategy determined by using current and past information of the controlled object to predict system performance in the future [

34,

35]. In other words, model predictive control technology possesses the inherent advantage of overcoming time delays. Thus, the active compensation strategy based on predictive control technology is particularly suitable for time-delay systems. In addition, for the purpose of actively compensating for the network delay of CPS, the network predictive control has been presented in literature [

36,

37]. At the same time, the analysis shows that the control performance of the delay system using networked predictive control is similar to that of the system without delay. It is worth noting that the research object of the active compensation strategy mentioned above is the fully actuated system, which cannot directly cope with the delay control problem of the underactuated USV in the network environment. Hence, the networked predictive control scheme needs to be redesigned to make it suitable for trajectory tracking control of underactuated USV with time-varying delays.

At the present, networked predictive control technology is widely employed in trajectory tracking control under communication constraints due to its ability to actively compensate for system delays. Aiming at trajectory tracking control of unmanned vehicles in a network environment, in [

38], Zhang designs a tracking controller based on networked predictive control technology to achieve accurate trajectory tracking under time-varying communication delays. In this study, only fixed delays are considered, and time-varying delays are not considered. Chen et al. introduce networked predictive control into collaborative path tracking of unmanned vehicles [

39], and the time-varying delay of the system is accurately compensated with the help of the designed two data buffers and networked predictive control strategy. However, the control objects involved in the above studies are all fully actuated systems. To the best of our knowledge, for typical nonlinear underactuated systems such as USVs, there is no research on using networked predictive control strategy to solve the trajectory tracking control problem of USVs under time-varying delays. Motivated by the proposal in [

37] to design a networked predictive control architecture to compensate for the time delay actively, this work designs a networked predictive control scheme based on discrete-time SMC to suppress the negative impact of time-varying delays on the USV control system.

Inspired by the above discussion, this paper focuses on developing a solution based on networked predictive control to deal with the trajectory tracking control of the USV suffering from time-varying network delays. With the application of dual-loop technology, the controller design is divided into inner-loop controller design and outer-loop controller design. In specific, the outer-loop controller is composed of a discrete-time surge virtual velocity control law and a discrete-time sway virtual velocity control law. In line with that, the inner-loop controller consists of a surge thrust controller and a steering torque controller, both of which are discrete-time sliding mode controllers. Furthermore, a networked predictive control strategy is implemented based on the above-mentioned dual-loop controller to achieve accurate compensation for time-varying network delays, thereby ultimately realizing accurate tracking for the USV’s desired trajectory.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

An improved discrete-time virtual speed control law is proposed. Compared with the one proposed in literature [

30], the improved discrete-time virtual velocity control law is more simpler and requires less calculation. The purpose of introducing the discrete-time virtual velocity control law is to transform the trajectory tracking problem into speed tracking.

In the light of the USV’s discrete-time dynamic mathematical model and discrete-time sliding mode control theory, the surge thrust control law and steering torque control law are constructed to realize asymptotic tracking for the virtual velocities.

Networked predictive control is introduced to nonlinear underactuated USV for the first time. Benefiting from networked predictive control, the time-varying delays existing in the communication network are completely compensated.

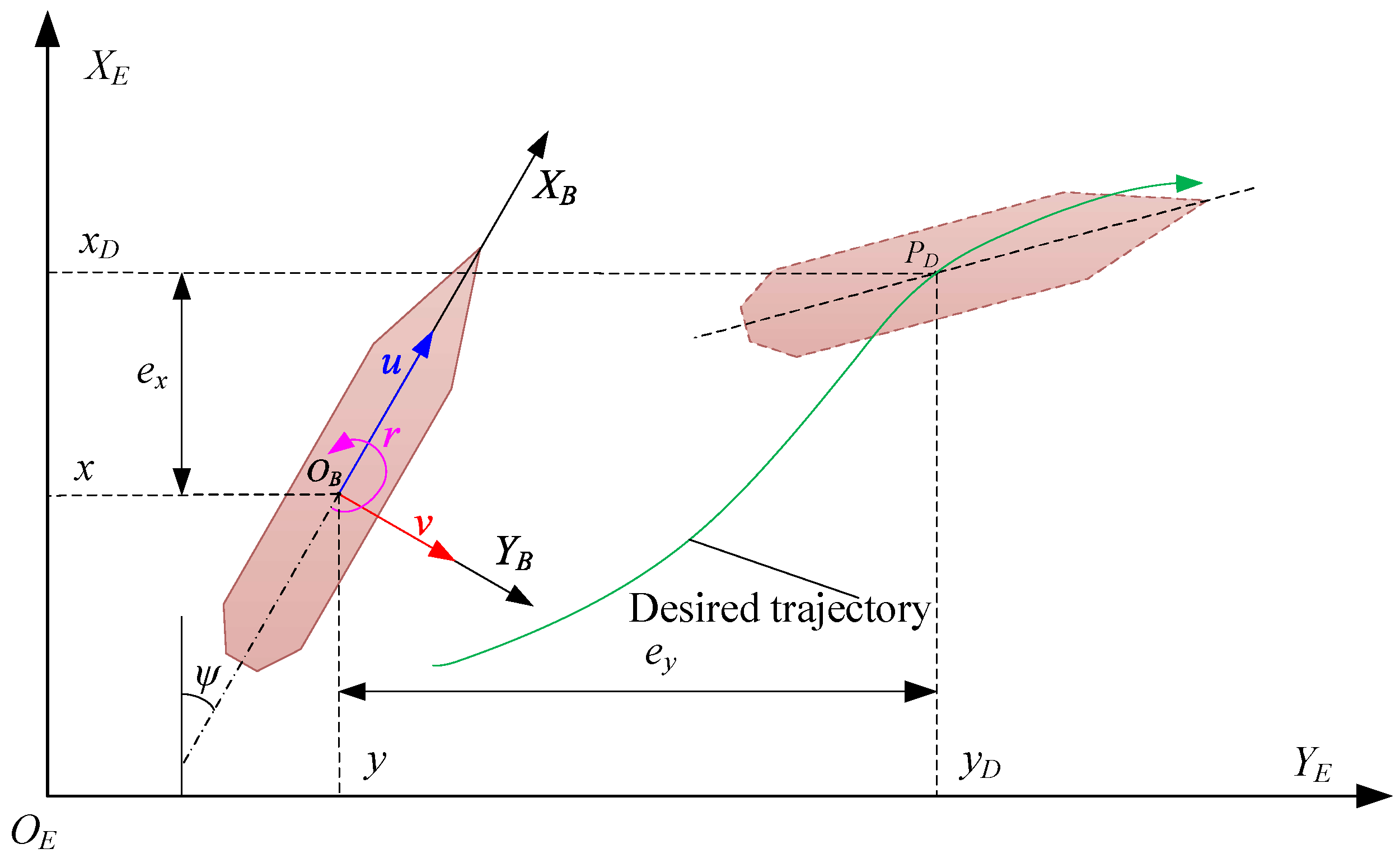

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. The problem construction including USV modeling, the influence of the network environment on USV control and the control objectives are stated in

Section 2.

Section 3 gives the detailed design process of the networked predictive sliding mode control strategy and the stability proof of the developed controller. Numerical simulation and result analysis for USV trajectory tracking are described in

Section 4. Finally, the conclusions of this study are drawn in

Section 5.

3. Networked Predictive Sliding Mode Controller Design

In this section, the main task is to design a networked predictive control strategy for the USV in a network environment. It is worth mentioning that the focus of this paper is the design of control strategies for the USV control system subjected to time-varying delays, so the control strategy design does not consider the external disturbance of the USV. This also means assuming that the external disturbances of the USV is known and can be fully compensated by the controller. Considering that the external disturbances can be quantitatively characterized by experiments and measurements, the above assumption is reasonable and feasible. As a result, the system disturbances () are not considered in the subsequent control strategy design. The detailed control scheme consists of three parts, i.e., the outer-loop discrete-time virtual velocity control law, the inner-loop sliding mode control strategy and the networked predictive control strategy. The controller design and its stability analysis are detailed in the following.

3.1. Networked Predictive Control Framework for the USV

The overall architecture of networked predictive control for the USV is illustrated in

Figure 3. As can be seen from

Figure 3, the networked predictive controller is comprised of three principal components, namely, the prediction controller, the communication compensator, and data buffers located on both sides of them. In accordance with the actual physical point of view, in order to prevent networked system from becoming open loop, it is reasonable to posit that only a finite number of consecutive data losses can be tolerated. In addition, the following assumptions are made.

Assumption A2. 1) The delay of the feedback channel from the sensor to the predictive controller is and its upper bound is (i.e, ); 2) The delay of the forward channel from the predictive controller to the actuator is , and its upper bound is (i.e, ); 3) The upper bound of consecutive data loss in both the feedback channel and the forward channel is . 4) Each data is timestamped as it is sent via the network.

Moreover, clock synchronization of all nodes is also an issue in networked control systems, there are several ways to achieve clock synchronization for digital devices. Since the networked predictive control problem of the USV is the main focus of this study, it is naturally assumed that the clocks of each component in the networked control system has been synchronized.

In order to handle time-varying delays and data loss, the following data sending mechanism is employed.

-

The velocity and position information of the USV is measured by the sensors and transmitted in the following data packets.

Where and .

-

In the same way, to prevent data loss in the forward channel, the following control prediction sequence is transmitted from the predictive controller side to the communication compensator side at time

k.

are the control prediction sequence at the future instants, which are calculated by using the predictive control algorithm through the received motion information of the USV delayed by steps. Where .

In terms of the feedback signals and control prediction are sequences accompanied by timestamps, two data buffers need to be set up to reorder the received data on the basis of timestamps. One is that data buffer A is located on the predictive controller side, and the other is data buffer B located on the communication compensator side. Hence, under assumption 2, the output on the predictive controller side and the control input on the actuator side are always available for use.

The control prediction sequences required by the USV actuators are preserved in buffer B. In accordance with the timestamp technology and the measurement method round-trip delay, Communication delays can be identified. Then, the latest predictive control input from the control prediction sequence (

8) is selected by the communication compensator at the time

k. Assume that the time delays of the forward channel and feedback channel are

and

respectively. In this way, one can have:

3.2. Design of the networked predictive controller for the USV

The networked predictive controller of the USV is comprised of two parts, the prediction generator and the communication compensator. The specific design procedure of the above parts is detailed in the following.

3.2.1. Prediction generator

A. Design of the virtual velocity control law

From Figure (3), the actual velocity and position of the USV are received by the controller after a delay of

steps at the time

k. Therefore, the available feedback information on the controller side is

and

. On the basis of such feedback information, the control input

is derived by using a discrete sliding mode scheme. The specific design procedure will be given later. Using

,

and

, then perform the following multi-step output predictor based on the nominal model, one can yield the following:

where

and

respectively denote the predicted values for the velocity

and position

at time

using the velocity and position of the USV up to time

, and

.

is represented as

. The mark ’

^’ on a variable indicates that the variable is a predicted value.

Through the implementation of the above predictive procedure, the velocity and position information of the USV at time

k is available on the controller side. In what follows, the virtual velocity control law is designed. The trajectory tracking errors of the USV are defined as:

In accordance with the expansion of (

5) and (

11), this leads to

Let’s define

and

in (

12) as the virtual velocity control variable. For the purpose of realizing the trajectory error of the USV converging to zero, the virtual velocity control law is designed as:

where

and

are the virtual velocity control laws of the USV in the surge and sway directions respectively. Where

,

and

are the positive constants to be designed. The function of the term

in (

13) is to prevent the virtual velocity control law from being too large. If it is too large, the virtual velocity will exceed the USV’s normal sailing speed, resulting in trajectory tracking failure.

and

are provided by the desired trajectory stored in the controller.

Theorem 1. Under the designed the virtual velocity control law (13), if th virtual velocity control law in consistent with the USV’s actual velocity, then he trajectory tracking error (11) asymptotically converges to zero.

Proof Substituting (

13) into (

12) results in

From the above equality, it is obvious that if and

satisfy then (

14) is simplified as:

Where

.

Let’s construct the following Lyapunov function

In the light of (

15) and (

16), one can deduce

Owing to

and

, the following inequality is obtained

Hence, from (

18) we can deduce that if

and

hold, the trajectory tracking error of the USV converges to zero asymptotically. □

B. Predictive discrete-time sliding mode controller design

On the basis of the state prediction and the surge virtual velocity control law, the tracking error of the surge virtual velocity is defined as:

According to (

19), the discrete-time integral sliding mode surface is constructed

where

,

is the sampling time.

In the light of discrete-time sliding mode theory, under ideal sliding mode, one gets

Substituting (

19) and (

20) into (

21), the following equality is derived

Combining (

19) and (

22), and using the expansion of (

10), the following equivalent control in the surge direction is obtained.

For the purpose of stabilizing the system on the sliding surface, the switching control law

is selected, where

is a constant. Therefore, at the controller side, the overall control law in the surge direction for the time

k can be obtained by adding the equivalent control and the switching control law, and its specific expression is

Up to this point, the thrust control law in the surge direction is accomplished. Next, the details of the steering torque control law in the sway direction are given.

Considering the time delay and in the light of the state prediction, the tracking error of the sway virtual velocity is defined as:

The heading is controlled by the steering torque. For the sake of making the steering moment term

appear in the sliding mode surface, the differential discrete-time sliding mode surface is constructed as follows:

where

. In the light of

, the following equality is obtained

Using the expansion of (

10) and substituting it to (

27), it can conclude that

where

and

are the predictions of the virtual swaying velocities at the time

and

, respectively, are jointly determined by the prediction of position and the desired position at the time

and

.

Let’s Denote

as

, thus, the term in (

28)

can be rewritten as follows

To facilitate simplicity, let the last four terms on the left in (

28) be denoted

, i.e.,

Substituting (

29) and (

30) into (

28), it can be learned that

Let the term in "{ }" on the left side of the above equality be represented as

, and the term on the right side be expressed as

. Then, by using (

31), the following equivalent steering torque control law can be given by

Similar to the thrust control law,

is the switching control law, which is used to stabilize the sliding mode surface in the surge direction, where

is the constant to be designed. In this way, by adding

and

, the final overall steering torque control law is derived as follows

Hence, the predictive discrete-time sliding mode controller at the time

k is completed in the surge direction and heading direction. It can be seen from

and

that the delay of the feedback channel is compensated for. To compensate for the time-varying delay of the forward channel at the time

k,

steps control prediction is implemented according to (

10), (

11)-(

13), (

19)-(

24), and (

25)-(

33), and thus the following predictive control sequence is obtained on the controller side.

where

and

.

3.2.2. Communication Compensator

In the actuator of the USV, the communication compensator is set. The predictive control sequence (

34) on the controller side is packed with timestamps and transmitted to the buffer B on the communication compensator side. Then, the buffer is used to preserve the received control sequence and reorder them according to timestamp. Finally, the proper predictive control is selected in the light of the system delay and sent to the actuator of the USV. In specific, assume that the feedback channel and forward channel delays at time

k are

and

, respectively. Thence, the network communication compensator selects the following control signal to the USV at time

k.

3.3. Stability Analysis of the Controller

The closed-loop stability of the networked predictive controller is analyzed in this section. It should be pointed out that the analysis of the closed-loop system consists of two parts: one is the stability of discrete-time sliding mode control, and the other is the stability analysis of the closed-loop system after the implementation of the predictive control strategy.

First, the discrete-time sliding mode controller is analyzed.

Lemma 1.

(Ghabi et al., 2018) The necessary and sufficient conditions for the stability of the discrete sliding mode system are that the selected sliding mode surface satisfies the condition:

In the light of (

10), (

20), and (

24), the following equality is obtained.

Considering (

37), for the sliding surface

, it is noticed that the holding of the Lemma 1 can be ensured by the following inequality.

Substituting (

37) into (

38), then it yields

As a result, the surge thrust controller is stable if the above inequality holds. Further, the stability analysis of the steering torque controller is presented. For the purpose of that, a similar practice is implemented. By substitution of (

26) and (

33) into (

10), one obtains

In order to ensure that the sliding mode surface

holds with respect to Lemma 1, the following inequality must be satisfied.

Combining A and B, one can conclude that

From (

42), it can be learned that

Therefore, if the above condition (

43) is satisfied, the discrete-time steering torque controller is stable. In other words, the foregoing analysis demonstrates that the discrete-time sliding mode controller is stable in both directions and that the tracking errors for surge and sway velocities are uniformly bounded. That is,

and

are uniformly bounded.

Next, the closed-loop stability of the aforementioned discrete-time sliding mode control after introducing the networked predictive control strategy will be analyzed. For the purpose of stability analysis, without considering the time delay, the closed-loop equation of the system is rewritten as

Where

. It is worth noting that the control input in (

44) is denoted as

due to it is a function of position, velocity and desired position. Similarly, the control input after implementing a predictive control strategy is also a function of the predicted position, predicted velocity and desired position. Accordingly, the closed-loop system considering time delay can be expressed as

To investigate such issue, Liu [

37] provides a detailed proof of the stability of nonlinear systems after implementing networked predictive control strategy. Its stability is demonstrated by converting the control input to the actuator side. In addition, the comprehensive analysis shows that the stability of the system implementing the predictive control strategy is equivalent to that of the ideal network system without time delays.

Theorem 2. Considering the system (45) with networked predictive sliding mode control strategy, its stability is equivalent to that of system (44) .

Proof. The specific proof can be found in [

37]. □

It can be seen from Theorem 2 that if system (

44) is stable, then system (

45) with networked predictive control is stable. Recalling (

39) and (

43), the stability of the discrete sliding mode controller has been demonstrated previous, so the networked predictive sliding mode control scheme considering the time delays for the USV is stable.

4. Simulation Results

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the developed control strategy, comparative numerical simulations are presented in this section. The model parameters of the USV used in the simulation are shown in

Table 1, which can be found in literature [

40]. The corresponding control parameters are selected as listed in

Table 2. The control parameters

and

are related to the sliding mode surfaces

and

, which are determined by (

39) and (

43). The sampling frequency of the control system is set to 100 Hz, which means the sampling period

is 10 ms.

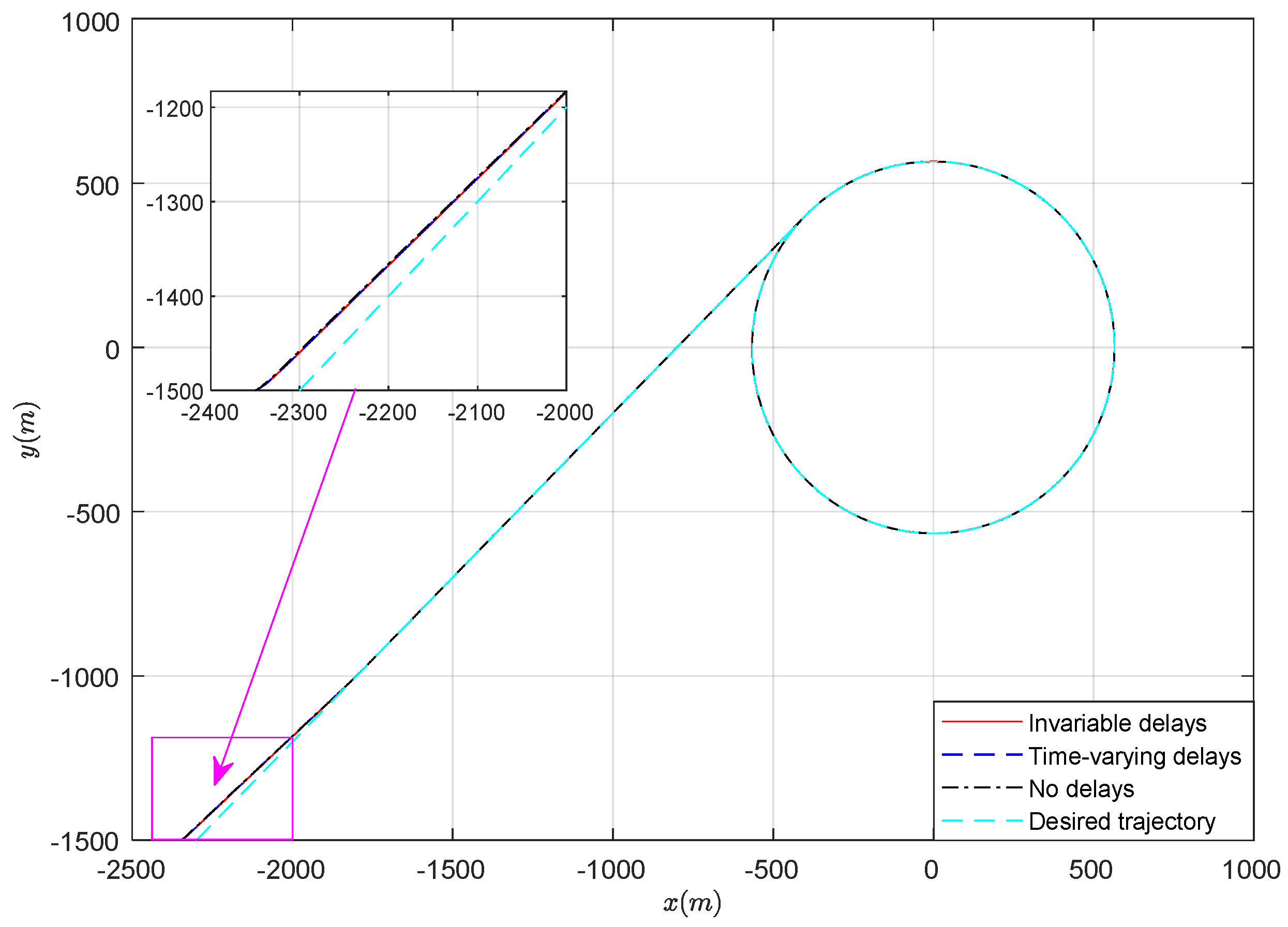

Considering that the complex desired trajectory can always be composed of straight lines and arcs, the desired trajectory is set as a curve consisting of straight line and circle. In specific, the desired trajectory of the USV is defined as follows.

Next, in this section, numerical simulations of three cases are implemented to better illustrate the effectiveness of the developed strategy. The three cases mentioned here are: without delays, invariable delays, and random delays.

Case 1: Without delays

For this case, the delays in the forward channel and feedback channel of the USV controller are both zero, i.e.,

,

. According to

Section 3.2.1, the following discrete-time sliding mode controller is designed using state information without delay.

Case 2: Invariable delays

In this case, invariable delays are assumed for both the forward and feedback channels of the control system. Here we assume

and

, respectively. Following (

24), (

33) and (

34), the networked predictive controller is given by:

Case 3: Random delays

In case 3, the delay

and

are time-varying, and their sum is assumed to be a random integer between 1 and 8. Similarly, the networked predictive controller is

In the above three cases, the initial positions of the USV are set as m, m and rad. Correspondingly, the USV’s initial velocities are set to m, m and , respectively.

For the sake of comparison and analysis, the corresponding result curves for the three cases mentioned above are drawn together.

The simulation results are depicted in

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11. From

Figure 4~

Figure 6, it can be seen that the developed networked predictive control strategy can effectively achieve trajectory tracking, whether it is dealing with fixed delays or time-varying delays.

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 depict the trajectory evolution in the x and y directions respectively. It can be seen from that the control performance of the system suffering from network delay is almost equivalent to that of the system without delay after being compensated by the network predictive strategy, except for a slight difference in position tracking error.

The position tracking errors in the

x and

y directions are drawn in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8. The mean absolute errors (

) are used to quantify the error characteristics of the three cases mentioned above, the mean absolute errors are presented in

Table 3.

It can be seen from

Table 3 that the mean absolute errors in the three cases are almost the same. In other words, the networked predictive control strategy can fully compensate for the delays in the latter two cases, which include invariable delays and time-varying delays.

Figure 9 depicts the evolution of the velocities in the three cases, which indicates that the velocity changes are exactly the same. In addition, the control inputs are presented in

Figure 10. From

Figure 10, it is obvious that the control inputs in the cases of delays are the exactly same as those without delays. In case 3, the random delay of

steps is represented in

Figure 11.

Therefore, the above analysis and discussion demonstrate the effectiveness of the control scheme developed in this paper for the USV trajectory tracking control problem in the network environment.