1. Introduction

The unification of quantum mechanics (QM) with the full set of fundamental interactions remains one of the most ambitious goals of modern theoretical physics. Tremendous progress has been made in describing electromagnetic, weak, and strong forces within the Standard Model (SM) framework [

1,

2], and early successes in quantum gravity research—such as loop quantum gravity [

3,

4] and string theory [

5,

6]—have offered valuable insights into the nature of space–time at the Planck scale. Nevertheless, a fully unified, experimentally testable theory that elegantly incorporates

all known interactions remains elusive.

A central difficulty lies in reconciling the apparent tension between quantum unitarity and the classical description of horizons and singularities in general relativity (GR). The black hole information paradox [

7,

8,

9,

10], in particular, epitomizes this conflict by suggesting that information about matter falling into a black hole might be irretrievably lost if Hawking radiation is purely thermal. Such a loss would violate unitarity, a cornerstone principle of quantum mechanics. Although various resolution proposals (firewalls [

11], fuzzballs [

12], holography [

13,

14], ER=EPR [

15],

etc.) have advanced our understanding of black holes, no consensus has emerged on a definitive solution that accommodates the entire Standard Model (including SU(3)

c for color and SU(2)

L×U(1)

Y for electroweak interactions) alongside quantum gravity.

1.1. Background and Motivation

In prior work, the

Quantum Memory Matrix (QMM) approach was proposed to address the black hole information paradox by interpreting space–time as a dynamic quantum information reservoir [

16]. This perspective treats each Planck-scale region of space–time as a finite-dimensional Hilbert space capable of “storing” local quantum data via

quantum imprints. By integrating QMM with gravitational degrees of freedom, it was shown that information from infalling matter could be preserved in and later retrieved from the structure of space–time, thus allowing black hole evaporation to remain unitary without necessitating exotic boundary conditions, wormhole-based nonlocality, or event horizon firewalls.

Subsequent extensions of the QMM framework to electromagnetism (U(1) gauge theory) demonstrated that local gauge invariance can be upheld in a discretized space–time by constructing suitable imprint operators from electromagnetic field strengths and currents. This development showed that QMM can embed quantum information about electric charge and photon modes at Planck-scale cells, opening the path to a more general inclusion of Standard Model interactions.

1.2. Aim and Scope of This Paper

The primary purpose of this work is to extend the QMM hypothesis further by incorporating:

The strong interaction, governed by non-Abelian SU(3)c gauge fields (QCD), including color confinement and gluon self-interactions.

The weak interaction, governed by SU(2)L×U(1)Y, encompassing chiral symmetry breaking, flavor mixing, and the Higgs mechanism.

In doing so, we aim to build on the local, discretized QMM structure to show how color and electroweak charges, along with their associated gauge bosons, can be imprinted in Planck-scale space–time quanta. Specifically, we will:

Outline how the strong force (quarks, gluons, color flux tubes) can be captured by imprint operators that remain locally gauge-invariant in a discretized SU(3) scenario.

Demonstrate how the weak isospin and hypercharge interactions (SU(2)L×U(1)Y) couple to QMM cells and how spontaneous symmetry breaking (including the Higgs field) fits into the QMM picture.

Present a unifying, QMM-based Hamiltonian that combines gravity (in discrete form), QCD, and the electroweak interactions under the same Planck-scale “memory” framework.

Discuss how colored and electroweak-charged matter falling into a black hole leaves quantum imprints that preserve unitarity in the Hawking evaporation process.

Propose potential observational consequences, including subtle effects on hadronic collisions, neutrino oscillations, rare decay processes, and astrophysical black hole evaporation.

1.3. Structure of This Paper

Following this introduction, we provide, in

Section 2, a brief overview of the Quantum Memory Matrix hypothesis and its previous applications to gravity and electromagnetism. In

Section 3, we incorporate SU(3)

c into QMM, focusing on how color confinement and quark/gluon degrees of freedom naturally fit into space–time quanta.

Section 4 discusses the extension to the weak sector, covering SU(2)

L×U(1)

Y, spontaneous symmetry breaking, and flavor transitions. In

Section 5, we synthesize these elements into a unified QMM Hamiltonian that includes gravitational, strong, and electroweak fields.

Section 6 explores implications for black hole evaporation, baryogenesis, and potential observational or experimental signatures.

Section 7 compares QMM with other unifying frameworks—such as AdS/CFT, ER=EPR, loop quantum gravity, and minimal length theories—highlighting QMM’s local and covariant advantages.

Section 8 then addresses open technical and conceptual issues, including precise non-Abelian imprint construction and the renormalization group flow at trans-Planckian scales. Finally, in

Section 9, we summarize our findings and outline future research directions aimed at achieving a fully discrete, information-centric model of the Standard Model plus gravity.

By solidifying how the strong and weak interactions can be encoded in a Planck-scale quantum memory structure, this paper aspires to move one step closer to a consistent theory of quantum gravity and gauge interactions in which no information is ever truly lost, even in the most extreme conditions found at black hole horizons.

2. Review of the QMM Framework

The QMM framework was originally introduced to address the longstanding tension between quantum unitarity and the classical description of horizons in general relativity [

16]. It interprets space–time not merely as a geometric background but as a quantum information

reservoir, discretized at the Planck scale. In this section, we summarize the key principles and mathematical underpinnings of the QMM. We begin by describing how space–time is discretized into Planck-scale cells, each equipped with a finite-dimensional Hilbert space. We then recapitulate the concept of

quantum imprints, which store local quantum information, ensuring that unitarity and locality are preserved. Finally, we highlight how the QMM has so far been successfully applied to reconciling black hole evaporation with unitarity in a purely gravitational setting, as well as in the presence of electromagnetic interactions.

2.1. Discretization of Space–Time and Finite Hilbert Spaces

A primary postulate of the QMM approach is that the continuum description of space–time ceases to be valid at the Planck scale,

. Instead, space–time is modeled as a

discrete set of fundamental cells, each with volume on the order of

(plus the Planck time

when considering temporal discretization). These

Planck cells, indexed by

x in a set

, collectively form the foundation of the QMM picture [

3,

4,

17].

Each cell

carries a finite-dimensional Hilbert space

whose dimension is large enough to encode local geometric and field-theoretic degrees of freedom, and yet remains bounded to impose a natural ultraviolet (UV) cutoff. The total QMM Hilbert space is a tensor product:

In such a discretized scheme, operators corresponding to geometric observables, e.g., quantized area or volume operators, gain discrete spectra, akin to loop quantum gravity approaches [

18,

19]. Unlike purely geometric formalisms, however, QMM interprets each cell

as an

active memory unit, capable of storing quantum-state data of matter or gauge fields that locally interact with it. A schematic depiction of these Planck-scale cells, each labeled by a local Hilbert space

, is shown in

Figure 1.

Because each cell is associated with a

finite dimensional space, integrals over momenta or field configurations are replaced by the sums over discrete modes, naturally regularizing the high-energy regime. This discretization not only prevents the infinities commonly encountered in continuum quantum field theory but also provides a physically motivated cutoff at the Planck scale [

17].

2.2. Quantum Imprints and Local Encoding of Information

The key innovation of the QMM is the notion of

quantum imprints [

16], which are thelocal records that store quantum information about field interactions or particle states passing through a given Planck cell. Each cell

x thus becomes an interactive element in spacetime, contributing to the dynamical evolution of the entire system rather than a mere geometric backdrop.

Imprint Operators

Formally, the imprinting process is captured by

imprint operators , which act on the tensor product space

If a field operator

(e.g., a scalar, fermionic, or gauge field) interacts at cell

x, the local Hamiltonian takes the schematic form

reflecting a bidirectional flow of quantum information: the cell “records” data about the field, and the field may in turn be affected by the cell’s stored imprint state. Because these interactions appear in a global Hamiltonian that is Hermitian, the total evolution is unitary, and no net information is lost.

Locality and Causality

Interactions in QMM remain strictly local, confined to individual cells. This ensures that no superluminal signaling or acausal effects arise. Cells only exchange information with nearest neighbors, if at all, via carefully constrained interactions consistent with relativistic causality.

Information Retrieval Mechanism

Once an imprint is stored in a cell’s Hilbert space, it can be retrieved by future interactions at that cell. Notably, black hole horizons exemplify how inward-falling quantum states imprint on the horizon cells. As Hawking-like radiation emerges, it interacts again with these cells, gradually extracting the imprinted data in subtle (often non-thermal) correlations. Hence, QMM resolves the paradox of “information loss” by embedding the missing data in local degrees of freedom that rejoin outgoing radiation in a unitary process [

7,

8,

16].

2.3. Previous Results: QMM with Gravity and Electromagnetism

Gravity

The first major application of QMM was to pure gravitational systems, particularly black holes [

16]. By discretizing spacetime around the horizon, QMM showed how to store and retrieve information from the horizon cells, allowing for a globally unitary description of black hole formation and evaporation. The equivalence principle and smooth horizon structure remained intact because the QMM’s imprinting occurs at Planck scales, leaving semiclassical geometry unaltered at macroscopic distances.

Electromagnetism

Incorporating U(1) gauge fields into QMM introduced gauge-invariant imprint operators built from field strengths

and charged matter currents [

1,

16]. This extension demonstrated that local electromagnetic data (charge, photon states) could imprint into Planck cells without breaking gauge invariance. Charged black hole (Reissner–Nordström) evaporation was then modeled in QMM, preserving unitarity by correlating the U(1) field with the local memory of spacetime quanta.

Rationale for SU(3)c and SU(2)L×U(1)Y

While these initial successes established the viability of the QMM as a unitarity-preserving framework for gravity and Abelian gauge fields, the Standard Model also contains non-Abelian gauge sectors—namely SU(3)c for QCD and SU(2)L for weak interactions (combined with U(1)Y). Incorporating these into the QMM is essential for describing quarks, gluons, electroweak bosons, flavor transitions, and related phenomena, especially under extreme gravitational conditions such as black hole collapse or the early universe. The rest of this paper undertakes precisely that task, clarifying how color and weak isospin degrees of freedom can be embedded in Planck-scale space–time memory cells.

3. Incorporating the Strong Interaction, SU(3)c

Having established how the QMM framework accommodates quantum gravity and Abelian gauge fields [

16], we now extend QMM to the non-Abelian sector of the Standard Model: the

strong interaction governed by SU(3)

c. Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD) underlies hadron formation, color confinement, and gluon self-interactions [

1,

2], making it significantly more intricate than Abelian electromagnetism. Here, we demonstrate how the QCD color degrees of freedom—quarks, gluons, and their local color charges—can be embedded in the Planck-scale QMM cells via

color imprint operators that preserve the local SU(3) gauge invariance.

3.1. Gauge Fields and Color Charge in the QMM Framework

In the continuum QCD, the gluon fields

, where

mediate interactions among quarks, each carrying a color index (red, green, blue). The SU(3) gauge symmetry is manifested in the covariant derivative

where

is the strong coupling constant, and

are the SU(3) generators in the appropriate representation [

1,

20]. Implementing this structure in a discretized QMM setting requires:

Local SU(3) Invariance. Each Planck cell x must interact with quark and gluon fields in a way consistent with gauge transformations. The QMM imprint operators should either be strictly gauge-invariant or gauge-covariant such that physical observables remain invariant under local transformations.

Finite-Dimensional Hilbert Spaces. While continuum QCD allows infinitely many field modes, the QMM discretization at cell x is finite. We represent the color degrees of freedom using a dimension large enough to encode local color states (e.g., quark triplets and gluon octets) but finite at the Planck scale, thus imposing a UV cutoff.

One practical approach for including gluon fields is to employ link variables

connecting neighboring cells, akin to lattice QCD [

20], but endowed with QMM’s memory functionality. Alternatively, one may introduce

directly in each cell, provided the color imprint operators retain the required local invariance.

3.2. Confinement and the QMM Interpretation

A hallmark of the QCD is

color confinement: the empirical fact that color-charged particles, quarks and gluons, cannot be isolated at macroscopic distances, forming instead color-neutral hadrons. In the lattice QCD, this is often conceptualized via

flux tubes or Wilson loops [

20], which reveal a linearly growing potential between static color charges.

From the QMM standpoint, we propose that color confinement naturally arises as color flux lines become

imprinted in the Planck cells along the line connecting quarks. This notion of color flux tubes stored by QMM cells is conceptually illustrated in

Figure 2, showing two quarks connected by a flux tube with local imprint sites. As two color charges attempt to separate, more and more QMM cells between them store color imprint information, effectively creating a “string” of color flux. Breaking the flux tube costs energy to produce quark–antiquark pairs. Thus, color-neutral hadrons correspond to net cancellations of these local color imprints within finite volumes of QMM cells.

Because each cell only has a finite capacity for storing color imprint states, the framework suggests a discretized mechanism for flux tube formation. At distances well above the Planck scale, this reproduces standard continuum confinement, while near or beyond trans-Planckian energies, the QMM memory limit might saturate or modify the confining potential.

3.3. Quarks, Gluons, and Local Imprint Operators

Quark Field Coupling.

In continuum QCD, a quark field

carries both spinor (

) and color (

) indices. In QMM, for each cell

x, we maintain a local quark operator

which interacts with the QMM cell’s Hilbert space

via imprint operators

where

are the SU(3) generators in the fundamental representation, and

is the discrete gluon operator. The factor

acts on

, encoding the local color interaction at that cell.

Gluon Self-Interaction.

Unlike QED, gluons themselves carry color charge. The gluon field

thus has nontrivial self-couplings:

where

are the SU(3) structure constants [

1]. In QMM, each cell’s imprint operator

must be constructed to maintain gauge invariance under these non-Abelian self-interactions. One possible structure is

where

is the non-Abelian field strength at cell

x, and the ellipses represent higher-order terms. The imprint operator must transform covariantly (or be explicitly invariant) under local SU(3) transformations.

Unitarity and Local Gauge Invariance.

As in the electromagnetic case, the total Hamiltonian

must be Hermitian. This ensures unitarity of the entire system, including the QMM degrees of freedom. Local gauge transformations that rotate quark color indices or gluon fields at each cell do not alter physical observables, preserving the fundamental SU(3) symmetry of QCD.

3.4. Hadronization, Non-Perturbative Effects, and Planck-Scale Cutoff

When describing QCD at energies below the confinement scale , hadrons form as color-neutral bound states. Non-perturbative effects like chiral symmetry breaking and meson/baryon formation are notoriously difficult to handle in continuum field theory. However, in a QMM discretized scenario, two conceptual features arise:

Local Color Neutralization. As quarks and gluons propagate through a series of Planck cells, color flux lines become “recorded” in the imprint operators. Hadrons correspond to quark/gluon configurations whose net imprint in a finite region of QMM cells is color-singlet.

Ultraviolet Completion. The finite-dimensional Hilbert space of QMM cells imposes a natural cutoff near the Planck scale. In principle, this might unify non-perturbative QCD with quantum gravity without encountering the infinities typical in continuum quantum field theories.

Moreover, at extremely high energies (close to or beyond the Planck scale), the QMM memory limit could saturate, potentially altering hadronization or parton showering processes in ways standard QCD does not anticipate. While these scenarios lie well outside current experimental reach, they are essential for understanding black hole formation by QCD matter or early-universe processes where strong interaction and gravitational effects commingle [

2].

Having demonstrated how SU(3)c can be grafted onto the QMM’s discretized, local-memory framework, we now turn to the electroweak sector—SU(2)L×U(1)Y—to complete the Standard Model gauge structure. In the next chapter, we address how weak isospin, hypercharge, and spontaneous symmetry breaking likewise fit into QMM, paving the way for a unified treatment of black hole evaporation and beyond.

4. Extending QMM to the Weak Interaction (SU(2)L×U(1)Y)

The electroweak sector of the Standard Model (SM) is governed by the non-Abelian SU(2)

L gauge group and an additional U(1)

Y symmetry, later spontaneously broken down to the electromagnetic U(1)

em via the Higgs mechanism [

1,

2]. In the QMM framework, we must ensure that both

local SU(2)

L and

local U(1)

Y invariance are preserved at each Planck-scale cell and that the resulting massive gauge bosons (W and Z) and massless photon arise consistently after spontaneous symmetry breaking. Additionally, the QMM must handle flavor transitions, such as neutrino oscillations and quark mixing, which introduce subtle quantum phases. Below, we outline how SU(2)

L×U(1)

Y can be embedded in QMM, focusing on gauge fields, imprint operators, and the Higgs field.

4.1. Weak Isospin, Hypercharge, and the QMM Cell Structure

In continuum electroweak theory, the gauge fields are:

, for , associated with SU(2)L.

, associated with U(1)Y.

Left-handed fermions (quarks and leptons) transform as SU(2)L doublets with weak isospin , while their hypercharge Y determines how they interact with .

Discretized Gauge Fields.

In the QMM discretization, each Planck cell is extended with local operators and . Alternatively, one may adopt link variables and , similar to lattice formulations. Here, g and are the usual SU(2)L and U(1)Y coupling constants, while are the SU(2) generators (Pauli matrices up to a factor).

Local Imprint Operators.

To ensure gauge invariance, the QMM imprint operators

must transform covariantly (or be strictly invariant) under SU(2)

L×U(1)

Y. For example, one can build imprint operators from the non-Abelian field strength tensors

and from the Abelian-like hypercharge field strength

. Such combinations can be inserted into local operators (analogous to the QCD case [

1,

20]):

that act on the local QMM Hilbert space

. Here,

are constants specifying coupling strengths to the QMM, and “weak currents” can include lepton or quark doublet operators

in a gauge-invariant manner.

4.2. Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking and the Higgs Mechanism

A central feature of the electroweak theory is the Higgs mechanism: an SU(2)

L×U(1)

Y scalar doublet

acquires a nonzero vacuum expectation value (vev), spontaneously breaking the gauge symmetry down to U(1)

em. The gauge bosons

and

Z become massive, while the photon remains massless [

1,

2].

Higgs Field in QMM.

In the QMM framework, the Higgs field

becomes another operator at cell

x, storing or retrieving local quantum data via an interaction Hamiltonian term of the form:

where

is the electroweak covariant derivative (including

). The imprint operator

ensures local interactions remain unitary and gauge-invariant. Once

acquires a vev, the QMM discretization distinguishes “broken” from “unbroken” cells in the sense that the local vacuum state reflects a shifted Higgs field. The mass terms of

and

Z bosons arise naturally as excitations about this new vacuum configuration.

Massive Gauge Bosons and U(1)em.

Post-symmetry breaking, the combinations and yield the massless photon field and the massive . This rewriting extends straightforwardly into QMM, where each cell’s SU(2)×U(1) operators recast into “mixed” operators for and . The local imprint operators remain valid, merely reorganized to reflect the new basis in which one gauge boson is massless and the others carry mass. Hence, the QMM approach seamlessly accommodates the conventional Higgs mechanism without altering macroscale predictions.

4.3. Flavor Transitions, Neutrino Mixing, and QMM

Unlike QCD, which confines color charges, the electroweak sector enables quark flavor transitions (through charged-current interactions with ) and neutrino flavor oscillations (once neutrinos have tiny masses). The QMM framework offers an interpretation of these processes in terms of local flavor imprinting:

Charged Currents and CKM Matrix.

For quark doublets

, the QMM interaction Hamiltonian includes terms like

where

is the Cabibbo–Kobayashi–Maskawa matrix mixing different generations. In QMM, the local imprint operator

captures these flavor transitions at each cell, preserving overall unitarity while allowing quark flavor changes.

Neutrino Mixing and PMNS Matrix.

Similarly, the lepton doublets

can incorporate mixing among neutrino mass eigenstates via the Pontecorvo–Maki–Nakagawa–Sakata (PMNS) matrix [

1,

2]. Each cell thus records a local imprint of neutrino flavor transitions. Over long baselines, these imprint interactions accumulate into the oscillation patterns observed experimentally.

Unitarity Preservation in Flavor Processes.

Thanks to the QMM’s global Hermitian Hamiltonian, the net evolution of quark and lepton flavors across Planck cells is manifestly unitary, preventing any net loss of flavor information. The QMM memory effectively stores interim “snapshots” of flavor states, which are carried forward to future interactions.

4.4. Possible Experimental Signatures in Rare Decays

While direct tests of Planck-scale physics remain out of reach, the QMM modification of electroweak processes might introduce minuscule corrections to flavor observables or rare decay branching ratios:

Neutral Meson Oscillations: Processes like or mixing might carry tiny QMM-induced phase shifts if the local imprinting at each cell slightly modifies the effective Hamiltonian.

Lepton Flavor Violation: For instance, or . If QMM interactions provide small corrections to mixing angles or couplings, rare decays might be altered at a level below current experimental sensitivities but potentially observable in future precision experiments.

CP Violation: Local QMM imprint operators could shift CP phases in the CKM or PMNS frameworks. Although existing constraints are stringent, subtle CP-violating effects might be an indirect signature of QMM’s Planck-scale discretization.

Any such signals would be extremely small, as QMM influences are suppressed by at least the ratio , where is the Planck mass. Nevertheless, theoretical searches for tiny deviations in rare decay channels or flavor transitions remain an intriguing route to probing Planck-scale unitarity mechanisms.

By extending QMM imprint mechanisms to SU(2)

L×U(1)

Y, we have shown that the electroweak symmetry, Higgs mechanism, and flavor mixing can be embedded in Planck-scale space–time quanta without violating gauge invariance. The next step is to

unify these ideas with the strong-interaction QMM formalism (

Section 3) and with the gravitational sector to yield a

single QMM Hamiltonian describing all known interactions. This unified Hamiltonian is the subject of

Section 5.

5. Unified QMM Hamiltonian for Strong, Weak, and Gravitational Interactions

Up to this point, we have shown how

quantum imprints in discretized space–time cells can encode information about gravity [

16], electromagnetism, the strong interaction (SU(3)

c), and the weak interaction (SU(2)

L×U(1)

Y). We now combine these ingredients into a single QMM-based Hamiltonian that unifies

all known interactions under a local, Planck-scale discretized framework. The resulting theory aims to preserve unitarity and locality for processes ranging from low-energy hadron formation to black hole evaporation, potentially offering a coherent quantum gravity and Standard Model (SM) description.

5.1. Combining SU(3)×SU(2)×U(1)×{Gravity} in QMM

The SM gauge group is

and gravity is incorporated via a discrete geometric structure at the Planck scale [

3,

4]. Within QMM, each Planck cell

x in the set

thus contains operators for:

, the color gluon fields (with indices ),

, the weak isospin fields (with ),

, the hypercharge field,

or analogous geometric/gravitational variables for each cell (e.g., discrete tetrads or loop quantum gravity variables) [

3,

16],

matter fields (quarks, leptons, Higgs) that transform under these gauge and gravitational sectors,

QMM imprint operators that store and retrieve local quantum data.

Each cell’s Hilbert space thus factorizes in principle to include gravitational, color, electroweak, and QMM memory subspaces, though in practice these may be highly entangled.

5.2. Constructing the Total Hamiltonian

We write the

unified Hamiltonian schematically as:

A high-level flowchart of how each sector—Gravity, QCD, Electroweak, and QMM memory—combines into the total Hamiltonian

is shown in

Figure 3.

Gravitational Sector .

This part captures the dynamics of discrete geometry (e.g., spin network edges/nodes or discrete tetrads) [

3,

19]. In QMM, gravity’s imprint operators record local spacetime curvature or spin-connection data at each Planck cell. The Hamiltonian constraints that generate diffeomorphisms or local Lorentz transformations remain valid at the discrete level, ensuring general covariance in the continuum limit.

QCD Sector .

Here, we have the SU(3) gauge fields

, quark fields

, and possibly link variables

. Color imprint operators

preserve local SU(3) invariance, capturing flux tubes and confinement phenomena [

1,

20].

Electroweak Sector .

Includes the SU(2)

L×U(1)

Y fields, Higgs doublet, and leptons/quarks in the appropriate representations. After spontaneous symmetry breaking, the W, Z bosons, and the photon modes appear. QMM imprint operators

handle local isospin and hypercharge data, as well as flavor transitions [

2].

Intrinsic QMM Sector .

Each cell has an internal “memory” subspace that can evolve even in the absence of external fields. This Hamiltonian might include neighbor-cell interactions or self-interactions that reflect the discrete geometry’s internal quantum dynamics [

16]. Such terms ensure that space–time quanta do not remain static but can propagate or reorder internal states as needed for a globally consistent geometry and field structure.

Interaction Hamiltonian .

Finally, the

imprint couplings appear here:

where

stands for gravitational, color, or electroweak operators that locally imprint on the QMM cell. By construction,

is Hermitian, and the total evolution

remains unitary.

5.3. Ensuring Local Gauge Invariance and Unitarity

Gravitational Covariance.

Similarly, local Lorentz or diffeomorphism invariance is encoded in how the discrete gravitational variables and imprint operators transform. Although technical details can follow loop quantum gravity or spin foam approaches [

3,

19], the QMM viewpoint adds that each cell’s geometry is also a memory container for gravitational data (e.g., curvature or torsion).

Global Unitarity.

Because

in Eq. (

11) is Hermitian, the combined system of matter + gauge fields + QMM memory evolves unitarily. No external boundary conditions or nonlocal couplings are required to preserve information. The local imprinting at each cell ensures that

every quantum event is recorded and in principle retrievable, even under extreme conditions such as black hole collapse.

5.4. Natural UV Cutoff and Coupling Behaviors

A recurring theme in quantum field theory is the appearance of divergences at high energies. In continuum form, loop integrals can diverge unless renormalized; certain couplings may “run” to unphysical values (e.g., Landau poles). QMM posits a fundamental, physical

discretization at the Planck scale, setting a maximum momentum scale

. The dimension

of each cell’s Hilbert space effectively caps the number of local field modes [

16,

17].

Renormalization Flow to Planck Scale.

Below Planck energies, the usual perturbative renormalization group (RG) flows for QCD or electroweak couplings remain valid; near or above

, the discrete QMM structure preempts further divergences. In principle, one might unify the SM couplings with gravity under this picture, revealing how running couplings approach finite values (or saturate) rather than diverge [

23,

24].

Interplay of Gravity and Gauge Fields.

Because gravity becomes strong near the Planck scale, the QMM memory for geometric variables merges with the memory for gauge fields. This unified system can alter the naive RG flows of QCD or electroweak sectors, potentially modifying the GUT (Grand Unified Theory) scale or offering an alternative to grand unification altogether. Detailed numerical or analytical studies remain an open challenge but are facilitated by QMM’s built-in cutoff and local unitarity.

5.5. Summary of the Unified Hamiltonian Approach

By assigning each Planck cell a finite-dimensional Hilbert space holding gravitational and gauge-field imprint operators, we embed the entire SU(3)×SU(2)×U(1) sector plus gravity into a single quantum system. Key features of this unified QMM Hamiltonian include:

Local Interactions at Each Cell: No nonlocal or acausal processes are invoked; fields imprint only on the cell they pass through, preserving locality and gauge invariance.

Global Unitarity: Because is Hermitian, the complete matter–geometry–QMM system evolves unitarily, avoiding information loss.

Finite UV Cutoff: Each cell’s dimension imposes a Planck-scale limit on the number of field modes, naturally taming high-energy divergences.

Seamless Emergence of SM Physics at Low Energies: Below the discretization scale, standard quantum field theory and the well-tested SM interactions appear, matching phenomenology.

With this unified Hamiltonian in place, we can next explore how it applies to black hole evaporation, baryon asymmetry generation, and other extreme phenomena. We do so in

Section 6, where we focus on how QMM resolves information paradoxes for the full SM and suggests new observational windows into Planck-scale physics.

6. Applications and Implications

With the QMM framework extended to include the full Standard Model gauge group (plus gravity), we can explore a range of physical scenarios. Below, we discuss four major areas of interest: (1) black hole evaporation with colored and electroweak-charged matter, (2) baryogenesis and sphaleron processes in the early universe, (3) non-perturbative and high-energy implications for confinement and flavor physics, and (4) possible observational prospects in cosmic rays, gravitational waves, and beyond.

6.1. Black Hole Evaporation with Full Standard Model Content

6.1.1. Colored and Weakly Interacting Matter Infalling

When matter carrying color charge (quarks/gluons) or electroweak charge (leptons, W/Z bosons) collapses into a black hole, the local interactions near the event horizon are governed by the combined imprint operators for QCD and electroweak fields (

Section 3,

Section 4). As these particles cross the horizon,

quantum imprints are deposited into the QMM cells at or near the horizon, encoding information about color, flavor, hypercharge, and isospin. This record-keeping extends earlier QMM treatments of neutral or purely electromagnetic matter [

16] to the broader SM sector.

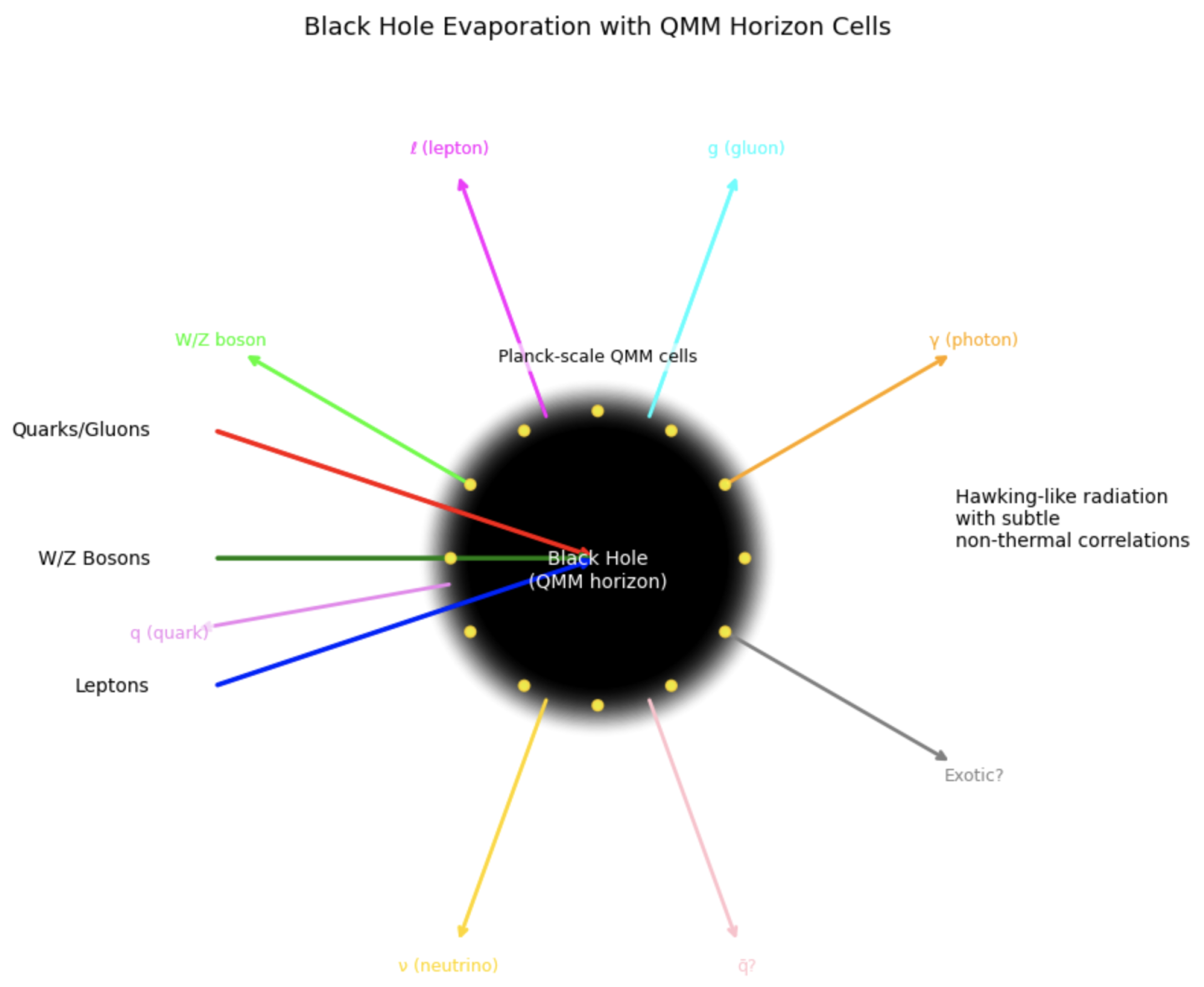

6.1.2. Non-Thermal Correlations in Hawking Radiation

Hawking’s semiclassical calculation indicates that black hole radiation is approximately thermal, revealing little about the black hole interior [

7,

8]. In QMM, however, the outgoing quanta — including gluons, quarks, photons, leptons — undergo further interactions with the horizon cells that store QCD and electroweak imprints. Over the course of evaporation, subtle

color and flavor correlations are imparted onto the radiation. Although small, these deviations from pure thermality ensure global unitarity (

Figure 4). In principle, the final radiation state after complete evaporation is entangled with the QMM degrees of freedom in such a way that no net information is lost [

9,

10].

Color Singlet Retrieval and the End State.

In typical QCD processes, asymptotic color-neutral hadrons eventually form. In a black hole, any color “hair” is naively thought to be hidden behind the horizon. But QMM memory for color flux implies that evaporating partons retrieve color data in correlated jets, albeit in a highly redshifted and Planckian context. The late-stage black hole, when reaching near-Planckian mass, merges the gravitational imprint sector with QCD imprint states [

16,

18]. Ultimately, the process remains unitary: the black hole does not vanish leaving hidden color microstates behind; instead, the QMM degrees of freedom systematically release that color or flavor data to the external field.

6.2. Baryogenesis, Sphalerons, and Early-Universe Processes

6.2.1. Electroweak Sphalerons in the QMM Framework

Electroweak baryogenesis scenarios rely on

sphaleron transitions, which violate baryon-plus-lepton number (

) while preserving

. In continuum field theory, sphalerons are non-perturbative solutions to the SU(2)

L gauge equations at high temperatures [

2]. Within QMM, sphaleron configurations correspond to large changes in the local imprint operators for the

field. As the Higgs field evolves during phase transitions, the QMM memory of these transitions can alter the net baryon asymmetry. While this does not necessarily solve the matter–antimatter asymmetry puzzle on its own, it provides a discrete, finite framework for analyzing the real-time evolution of sphalerons near the Planck epoch, potentially with fewer ultraviolet ambiguities.

6.2.2. QCD Phase Transitions and Color Imprints

The QCD sector also undergoes phase transitions in the early universe (e.g., at temperatures around the QCD scale

). Within QMM, local color confinement emerges as flux tubes imprint themselves in the discrete cells (

Section 3). At high temperatures, confinement may be temporarily lost, but as the universe cools, hadronization sets in. Since each Planck cell can store color information up to its memory limit, one can, in principle, model how domain walls, topological defects, or other non-perturbative features might form in a discretized manner. While direct observational signatures may be subtle, these processes could leave faint imprints in relic gravitational waves or other cosmological signals.

6.3. Confinement Scale, Flavor Physics, and High-Energy Collisions

6.3.1. Hadronization in Extreme Energies

Relativistic heavy-ion collisions (e.g., at the Large Hadron Collider or future colliders) produce hot, dense quark–gluon plasmas. While these energies remain far below the Planck scale, certain final-state correlations might reflect how color flux lines imprint upon the local environment. If QMM discretization imposes subtle constraints on color flux tubes or topological configurations, one might in principle detect small anomalies in jet substructure or flavor composition at extremely high energies. Though likely minute compared to standard QCD signals, these channels are worth considering for potential glimpses of Planck-scale physics.

6.3.2. Rare Decays and Flavor-Changing Processes

As touched on in

Section 4 and

Section 4.4, QMM corrections can manifest as tiny perturbations in flavor transitions—e.g., in quark mixing or neutrino oscillations. Similarly, small shifts in CP violation phases could affect processes like

–

mixing or lepton-flavor-violating decays. While beyond current experimental sensitivity, future precision experiments might see footprints of QMM-induced operators if they systematically deviate from predictions by a factor

.

6.4. Observational Prospects: Cosmic Rays, Gravitational Waves, etc.

6.4.1. Cosmic Rays and Primordial Black Holes

Primordial black holes (PBHs), if they exist, may be evaporating in the present epoch, emitting Hawking-like radiation containing quarks, gluons, gauge bosons, and leptons [

10]. QMM correlations in that emission could lead to non-thermal spectral features. If advanced gamma-ray or cosmic-ray observatories detect anomalous emission patterns from hypothesized PBHs, these could indirectly support QMM’s unitarity-preserving mechanism [

7,

8]. Non-detections would set upper limits on PBH abundance or QMM effects.

6.4.2. Gravitational Waves from Black Hole Mergers

Recent gravitational wave detections have opened a new observational window on black holes [

22]. If QMM modifies the ringdown or late-time behavior of merging black holes—due to horizon-scale memory interactions—small anomalies in the waveforms may appear, especially at the very end of the inspiral or in post-merger echoes. Though extremely challenging to measure, next-generation detectors (Cosmic Explorer, Einstein Telescope) might conceivably detect tiny phase shifts or echoes linked to QMM horizon memory.

6.4.3. Analog Experiments and Quantum Simulators

Finally, as suggested in previous QMM studies [

16], analog experiments using tabletop “event horizon” systems (e.g., in fluid analogs, optical waveguides, or superconducting circuits) could mimic certain aspects of QMM’s local imprinting. Similarly, discrete lattice gauge theories on quantum computers or quantum simulators might approximate QMM’s Planck-cell structure and yield indirect tests of the imprint-and-retrieval cycle at smaller, controllable energy scales. While these experiments cannot fully replicate Planck-scale physics, they may reveal the feasibility or consistency of local memory-based unitarity solutions.

From black hole evaporation to early-universe baryogenesis and high-energy collisions, the QMM approach offers a unifying lens through which the Standard Model’s strongest puzzles (like color confinement, neutrino mixing, and unitarity at horizons) gain a local, discrete explanation. These phenomena underscore QMM’s potential to bridge quantum gravity and particle physics in a single consistent framework. Next, in

Section 7, we compare this approach with other popular unification attempts—holography, wormhole-based ER=EPR, loop quantum gravity, and minimal-length theories—highlighting the QMM’s distinctive advantages.

7. Comparison with Other Approaches

The QMM framework seeks to unify quantum mechanics and gravity, along with the full Standard Model gauge group, by positing that Planck-scale space–time cells act as local information reservoirs. This stands in contrast to many traditional approaches to the black hole information paradox and quantum gravity. Below, we briefly compare QMM with four well-established lines of research: (1) holography and AdS/CFT, (2) ER=EPR and wormhole-based nonlocality, (3) loop quantum gravity and spin foam models, and (4) minimal length or causal set theories. These comparisons highlight the local, discretized, and gauge-invariant perspective QMM brings, as well as open points of synergy or divergence.

7.1. Holography and the AdS/CFT Correspondence

7.1.1. Boundary vs. Bulk Encoding of Information

Holographic approaches, including the AdS/CFT correspondence, assert that the degrees of freedom in a

-dimensional bulk gravitational system are equivalent to those of a

d-dimensional boundary conformal field theory [

5,

13,

14]. Information about bulk black holes is “holographically” stored on the boundary, which can resolve the black hole information paradox by transforming it into a purely field-theoretic problem in lower dimensions.

QMM Contrast.

While holography relies on boundary degrees of freedom and often requires a specific asymptotic geometry (e.g., AdS), QMM encodes information locally throughout the four-dimensional bulk. Planck-scale cells store quantum imprints of matter and gauge fields at each point in space–time, rather than on a boundary. This local encoding remains valid in asymptotically de Sitter or other cosmological spacetimes, where standard AdS/CFT techniques may not directly apply.

7.1.2. Applicability to Realistic Cosmologies

Since our universe appears to be close to de Sitter-like expansion (with a positive cosmological constant), AdS-based holography is not obviously the final word on real-world quantum gravity. QMM offers a geometrically local scenario that may be extended to various backgrounds, preserving unitarity while avoiding reliance on a conformal boundary.

7.2. ER=EPR Conjecture and Wormhole-Based Nonlocality

7.2.1. Einstein–Rosen Bridges as Entanglement

The ER=EPR proposal [

15] posits that the nonlocal entanglement of quantum mechanics (EPR pairs) can be interpreted geometrically via Einstein–Rosen bridges (wormholes). Some black hole information paradox resolutions lean on this topology-changing interpretation, suggesting that information retrieval is facilitated by hidden wormholes connecting interior and exterior degrees of freedom.

QMM Contrast.

QMM does not assume or require large-scale wormholes or topological changes to maintain unitarity. Instead, local interactions at the Planck scale encode and later retrieve quantum information from the horizon cells—no nonlocal bridging is necessary. This maintains classical large-scale space–time topology, respecting the equivalence principle and causality at macroscopic distances.

7.2.2. Observer Independence

Wormhole-based solutions often introduce subtleties about observer dependence and potential horizons merged by nontrivial topology. QMM, by contrast, implements an observer-independent local memory: each Planck cell’s Hilbert space evolves unitarily regardless of who observes it, sidestepping issues of observer-dependent complementarity or firewall paradoxes.

7.3. Loop Quantum Gravity, Spin Foams, and Causal Sets

7.3.1. Discrete Geometry Emphasis

Loop quantum gravity (LQG) and spin foam models propose that space–time itself is composed of discrete spin networks, where edges carry quantized areas and volumes [

3,

4]. Similarly, causal set theory posits that the fundamental structure is a partially ordered set of events consistent with relativistic causality [

27]. In each, the continuum emerges at large scales, but the geometry is fundamentally discrete.

QMM vs. LQG/Spin Foam.

QMM shares the discrete flavor of these approaches, but it enhances the notion of a discretized geometry with explicit information-storage capacity. Each Planck cell in QMM is not merely a geometric datum (area, spin), but also a finite-dimensional Hilbert space that can store local quantum states. Where LQG focuses on geometry quantization, QMM focuses on information quantization. The two ideas could be complementary: one might combine QMM’s local memory concept with LQG’s well-studied discrete geometry to ensure that matter, gauge, and gravitational interactions are all captured consistently.

7.3.2. Non-Abelian Gauge Fields and Lattice-Like Formulations

Although LQG and spin foam models typically focus on gravity, they can in principle incorporate gauge fields. QMM uses a lattice-like approach to embed gauge fields in Planck cells. Causal set theory does something analogous with partial orders. Thus, synergy may arise if one treats geometry with LQG/spin foams while letting QMM handle the “information imprint” aspect. The union could provide a robust discrete quantum gravity + gauge theory picture.

7.4. Minimal Length Theories and Causal Set Ideas

7.4.1. UV Regularization and Planck-Scale Cutoffs

Various scenarios suggest the existence of a minimal length or a fundamental UV cutoff at or near the Planck scale to tame divergences in quantum field theory [

17]. Causal set theory also postulates that spacetime is fundamentally discrete, with each event part of a partially ordered set respecting causality [

27].

QMM Perspective.

QMM indeed posits a minimal length scale—each cell has finite volume . Moreover, each cell is associated with a finite-dimensional Hilbert space, capping the number of local degrees of freedom. Hence, QMM can be viewed as a physical realization of minimal length ideas: beyond imposing a cutoff, QMM treats the cell as an active memory site. This helps unify the notion of discrete spacetime with a mechanism for storing quantum information, maintaining unitarity in processes like black hole evaporation.

7.4.2. Cause–Effect and Local Encoding

Causal set approaches ensure that no event has more than one immediate predecessor or successor outside its light cone. QMM ensures strict locality—imprinting interactions only occur within a single Planck cell or between neighboring cells. While not identical, both reflect the principle that fundamental causality is essential to quantum gravity.

7.5. Summary of Comparisons

Local vs. Nonlocal Mechanisms.

Holography and ER=EPR typically involve nonlocal mappings (bulk–boundary correspondences, wormhole entanglement) to preserve unitarity. QMM keeps all interactions local at the Planck scale: each cell is an autonomous memory site, storing and releasing data strictly within its boundaries.

Boundary vs. Bulk Encoding.

Whereas holography uses boundary degrees of freedom to encode bulk states, QMM organizes the bulk itself into discrete Planck cells. This may offer a more direct route to describing real cosmologies without specialized AdS boundaries.

7.6. Concluding Remarks on Comparisons

In essence, QMM shares many goals with these other frameworks—resolving the black hole information paradox, unifying quantum field theory and gravity, taming UV divergences—yet differs in its local, discretized, memory-based formalism. The next section addresses open challenges and technical issues in fully realizing QMM, from building precise non-Abelian imprint operators to integrating renormalization group flows and exploring experimental feasibility.

8. Challenges and Open Questions

Throughout this work, we have shown how the QMM framework can be extended to accommodate the full set of Standard Model interactions—namely SU(3)c for QCD and SU(2)L×U(1)Y for the electroweak sector—together with a discretized model of quantum gravity. Despite this progress, several conceptual and technical challenges remain to be addressed:

-

Exact Construction of Non-Abelian Imprint Operators.

While we have sketched how to incorporate local SU(3)c and SU(2)L gauge invariance, a fully rigorous definition of imprint operators for the full range of non-Abelian interactions remains an open problem. Ensuring these operators transform properly (covariantly or as singlets) under local gauge transformations in a discrete lattice-like setup requires further elaboration, especially if we wish to handle strong self-interactions (e.g., gluon self-couplings) and mixed flavor transitions.

-

Renormalization Group Analysis and Low-Energy Effective Theories.

In conventional quantum field theory, coupling constants run with energy scale. In QMM, the finite-dimensional nature of each cell imposes a natural Planck-scale cutoff, but how this meshes with the usual renormalization group flow is not yet fully elucidated. Analyses must clarify if—and how—the discrete QMM structure modifies coupling unification scenarios or prevents Landau poles in a manner consistent with low-energy observations.

-

Dynamical Quantum Geometry and Loop-Like Structures.

While QMM provides a discretized scheme for storing quantum information, one typically wishes to see how discrete geometric variables themselves evolve. This raises questions about linking QMM with loop quantum gravity, spin foam models, or other discrete gravitational formalisms, so that the geometry of each cell is not just an external label but a dynamic entity influencing (and being influenced by) the imprint operators.

-

Quantum States of Horizon Cells and Near-Horizon Physics.

Although black hole horizons offer the most striking application of QMM’s memory mechanism, a deeper treatment of the near-horizon degrees of freedom is needed. In particular, how exactly the horizon cells entangle with outgoing modes, and how one might observe non-thermal signatures in practice, remains a major challenge—both theoretically and experimentally.

-

Experimental Feasibility and Observational Strategies.

Direct tests of Planck-scale phenomena lie beyond current technology. Nevertheless, indirect signals—such as small deviations in rare decay processes, flavor transitions, or possible anomalies in gravitational wave ringdown—may provide windows into QMM effects. Identifying robust, model-specific predictions that could be probed by next-generation experiments is an ongoing task.

-

Computational and Numerical Simulations.

Simulating lattice gauge theories coupled with a discrete “memory matrix” is non-trivial, particularly if one aims to include dynamical geometry. Efforts to develop efficient classical or quantum algorithms to explore QMM’s predictions—e.g., for black hole microstates or baryogenesis processes—would help quantify the theory’s viability and link it to real-world data.

These challenges outline the terrain ahead for extending and testing the QMM approach. Their resolution will require coordinated efforts, combining methods from lattice gauge theory, loop quantum gravity, quantum information science, and high-energy phenomenology to bring QMM from a conceptual framework toward a more concrete and falsifiable theory.

9. Conclusion

By extending the Quantum Memory Matrix (QMM) framework—originally designed to reconcile quantum mechanics with gravity through discretized space–time cells—to encompass the entire Standard Model gauge sector, we have taken a crucial step toward a unified picture of quantum fields and geometry. In previous publications, QMM was successfully integrated with gravitational degrees of freedom and electromagnetism, demonstrating how local “quantum imprints” in Planck-scale cells could preserve unitarity and record field interactions without resorting to nonlocal mechanisms or exotic geometries. This work completes the triptych by embedding the strong (SU(3)c) and electroweak (SU(2)L×U(1)Y) sectors into the QMM, thereby tying together all four fundamental interactions under a single discrete, memory-based hypothesis. We have shown that each cell can store color and electroweak charges in gauge-invariant imprint operators, unifying them with gravitational and electromagnetic degrees of freedom via a single Hamiltonian construction. Such a framework enables local unitarity even under black hole formation and evaporation while simultaneously imposing a natural ultraviolet cutoff by limiting the dimension of each cell’s Hilbert space.

Although open questions persist—ranging from refining non-Abelian imprint operators to analyzing renormalization flows at trans-Planckian energies—our results highlight the versatility and consistency of QMM as a fully unified approach. In particular, we have identified possible connections to established quantum gravity programs (loop quantum gravity, causal sets) and provided toy simulation ideas that illustrate how local memory capacities might manifest in lattice or analog systems. These developments go beyond earlier achievements in QMM-plus-gravity or QMM-plus-electromagnetism, offering concrete pathways for future theoretical and numerical exploration.

By demonstrating how discretized Planck cells can serve as a universal storage mechanism for gravitational, strong, and electroweak fields alike, this paper underscores the promise of QMM to bridge high-energy physics and quantum gravity in a single, coherent framework. We, therefore, hope that numerical simulations, astrophysical signatures, and analog experiments continue to evolve around these principles, ultimately testing whether the QMM indeed paves a robust path toward a complete unification of fundamental physics.

Author Contributions

F.N. conceptualized the research and drafted the outline; E.M. and V.V. helped shape the formalism; All authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final version.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Peskin, M.E.; Schroeder, D.V. An Introduction to Quantum Field Theory; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, S. The Quantum Theory of Fields, Vol. 1: Foundations; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rovelli, C. Loop Quantum Gravity. Living Rev. Relativity 1998, 1, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashtekar, A.; Lewandowski, J. Background Independent Quantum Gravity: A Status Report. Class. Quantum Gravity 2004, 21, R53–R152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldacena, J. The Large-N Limit of Superconformal Field Theories and Supergravity. Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 1998, 2, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polchinski, J. String Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hawking, S.W. Breakdown of Predictability in Gravitational Collapse. Phys. Rev. D 1976, 14, 2460–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W. Particle Creation by Black Holes. Commun. Math. Phys. 1975, 43, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unruh, W.G. Notes on Black-Hole Evaporation. Phys. Rev. D 1976, 14, 870–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preskill, J. Do Black Holes Destroy Information? Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 1992, 1, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almheiri, A.; Marolf, D.; Polchinski, J.; Sully, J. Black Holes: Complementarity or Firewalls? J. High Energy Phys. 2013, 2013, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.D. The Fuzzball Proposal for Black Holes: An Elementary Review. Fortschr. Phys. 2005, 53, 793–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ’t Hooft, G. Dimensional Reduction in Quantum Gravity. Conf. Proc. C 1993, 930308, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susskind, L. The World as a Hologram. J. Math. Phys. 1995, 36, 6377–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldacena, J.; Susskind, L. Cool Horizons for Entangled Black Holes. Fortschr. Phys. 2013, 61, 781–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F.; Brasher, R.; Marx, E. The Quantum Memory Matrix: A Unified Framework for the Black Hole Information Paradox. Entropy 2024, 26, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossenfelder, S. Minimal Length Scale Scenarios for Quantum Gravity. Living Rev. Relativity 2013, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rovelli, C. Black Hole Entropy from Loop Quantum Gravity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3288–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashtekar, A.; Pawlowski, T.; Singh, P. Quantum Nature of the Big Bang: Improved Dynamics. Phys. Rev. D 2006, 74, 084003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.G. Confinement of Quarks. Physical Review D 1974, 10, 2445–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddings, S.B.; Lippert, M. The Information Paradox and the Black Hole Partition Function. Phys. Rev. D 2007, 76, 024006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, B.P.; Abbott, R.; Abbott, T.D.; Abernathy, M.R.; Acernese, F.; Ackley, K.; Adams, C.; Adams, T.; Addesso, P.; Adhikari, R.X.; et al. Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 061102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. Ultraviolet Divergences in Quantum Theories of Gravitation. In General Relativity: An Einstein Centenary Survey; Hawking, S.W., Israel, W., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1979; pp. 790–831. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter, M.; Saueressig, F. Renormalization Group Flow of Quantum Einstein Gravity in the Einstein-Hilbert Truncation. Phys. Rev. D 1998, 65, 065016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, J.J.; Napolitano, J. Modern Quantum Mechanics; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dyson, F.J. Divergent Series in Quantum Electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. 1952, 85, 631–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombelli, L.; Koul, R.K.; Lee, J.; Sorkin, R.D. A Quantum Source of Entropy for Black Holes. Phys. Rev. D 1987, 34, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).