Submitted:

24 December 2024

Posted:

25 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Epstein-Barr

2.1. Pathophysiology

2.2. Hit and Run Theory

3. HIV

4. Prevention

5. Diagnostic Approach

6. General Treatment Approaches for Lymphomas

Targeted Therapies for EBV-Associated Lymphomas

7. Prognosis

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EBV | Epstein-Barr Virus |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| ART | Antiretroviral treatment |

References

- Woolhouse, M.; Scott, F.; Hudson, Z.; Howey, R.; Chase-Topping, M. Human Viruses: Discovery and Emergence. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2012, 367, 2864–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesri, E.A.; Feitelson, M.A.; Munger, K. Human Viral Oncogenesis: A Cancer Hallmarks Analysis. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 15, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engels, E.A. Epidemiologic Perspectives on Immunosuppressed Populations and the Immunosurveillance and Immunocontainment of Cancer. Am. J. Transplant. Off. J. Am. Soc. Transplant. Am. Soc. Transpl. Surg. 2019, 19, 3223–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakkalci, D.; Jia, Y.; Winter, J.R.; Lewis, J.E.; Taylor, G.S.; Stagg, H.R. Risk Factors for Epstein Barr Virus-Associated Cancers: A Systematic Review, Critical Appraisal, and Mapping of the Epidemiological Evidence. J. Glob. Health 2020, 10, 010405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.A.; Achong, B.G.; Barr, Y.M. VIRUS PARTICLES IN CULTURED LYMPHOBLASTS FROM BURKITT’S LYMPHOMA. Lancet Lond. Engl. 1964, 1, 702–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.M.; Binnicker, M.J.; Campbell, S.; Carroll, K.C.; Chapin, K.C.; Gilligan, P.H.; Gonzalez, M.D.; Jerris, R.C.; Kehl, S.C.; Patel, R.; et al. A Guide to Utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases: 2018 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society for Microbiology. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2018, 67, e1–e94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loghavi, S. Quantitative PCR for Plasma Epstein-Barr Virus Loads in Cancer Diagnostics. Methods Mol. Biol. Clifton NJ 2016, 1392, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvester, J.E.; Buchanan, B.K.; Silva, T.W. Infectious Mononucleosis: Rapid Evidence Review. Am. Fam. Physician 2023, 107, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Dowd, J.B.; Palermo, T.; Brite, J.; McDade, T.W.; Aiello, A. Seroprevalence of Epstein-Barr Virus Infection in U. S. Children Ages 6-19, 2003-2010. PloS One 2013, 8, e64921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Robertson, E.S. Epstein-Barr Virus History and Pathogenesis. Viruses 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonoyan, L.; Vincent-Bugnas, S.; Olivieri, C.-V.; Doglio, A. New Viral Facets in Oral Diseases: The EBV Paradox. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.H.; Lee, Y.-H.; Myong, J.-P.; Kwon, M. The Impact of Infectious Mononucleosis History on the Risk of Developing Lymphoma and Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: A Retrospective Large-Scale Cohort Study Using National Health Insurance Data in South Korea. Cancer Res. Treat. 2024, 56, 1077–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hjalgrim, H.; Askling, J.; Rostgaard, K.; Hamilton-Dutoit, S.; Frisch, M.; Zhang, J.-S.; Madsen, M.; Rosdahl, N.; Konradsen, H.B.; Storm, H.H.; et al. Characteristics of Hodgkin’s Lymphoma after Infectious Mononucleosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 349, 1324–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henle, W.; Diehl, V.; Kohn, G.; Zur Hausen, H.; Henle, G. Herpes-Type Virus and Chromosome Marker in Normal Leukocytes after Growth with Irradiated Burkitt Cells. Science 1967, 157, 1064–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, V.; Henle, G.; Henle, W.; Kohn, G. Demonstration of a Herpes Group Virus in Cultures of Peripheral Leukocytes from Patients with Infectious Mononucleosis. J. Virol. 1968, 2, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimber, U.; Adldinger, H.K.; Lenoir, G.M.; Vuillaume, M.; Knebel-Doeberitz, M.V.; Laux, G.; Desgranges, C.; Wittmann, P.; Freese, U.K.; Schneider, U. Geographical Prevalence of Two Types of Epstein-Barr Virus. Virology 1986, 154, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fingeroth, J.D.; Weis, J.J.; Tedder, T.F.; Strominger, J.L.; Biro, P.A.; Fearon, D.T. Epstein-Barr Virus Receptor of Human B Lymphocytes Is the C3d Receptor CR2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1984, 81, 4510–4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, J.; Weis, J.; Fearon, D.; Whang, Y.; Kieff, E. Epstein-Barr Virus Gp350/220 Binding to the B Lymphocyte C3d Receptor Mediates Adsorption, Capping, and Endocytosis. Cell 1987, 50, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatano, Y.; Ideta, T.; Hirata, A.; Hatano, K.; Tomita, H.; Okada, H.; Shimizu, M.; Tanaka, T.; Hara, A. Virus-Driven Carcinogenesis. Cancers (Basel) Sato, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Suzuki, C.; Abe, Y.; Masud, H.M.A.A.; Inagaki, T.; Yoshida, M.; Suzuki, T.; Goshima, F.; Adachi, J.; et al. S-Like-Phase Cyclin-Dependent Kinases Stabilize the Epstein-Barr Virus BDLF4 Protein To Temporally Control Late Gene Transcription. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e01707-18, 10.1128/JVI.01707-18. 2021, 13, 2625. [CrossRef]

- Hjalgrim, H.; Rostgaard, K.; Johnson, P.C.D.; Lake, A.; Shield, L.; Little, A.-M.; Ekstrom-Smedby, K.; Adami, H.-O.; Glimelius, B.; Hamilton-Dutoit, S.; et al. HLA-A Alleles and Infectious Mononucleosis Suggest a Critical Role for Cytotoxic T-Cell Response in EBV-Related Hodgkin Lymphoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 6400–6405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahnassy, A.A.; Zekri, A.-R.N.; Asaad, N.; El-Houssini, S.; Khalid, H.M.; Sedky, L.M.; Mokhtar, N.M. Epstein-Barr Viral Infection in Extranodal Lymphoma of the Head and Neck: Correlation with Prognosis and Response to Treatment. Histopathology 2006, 48, 516–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Münz, C. Latency and Lytic Replication in Epstein-Barr Virus-Associated Oncogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, J.R. Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) Reactivation and Therapeutic Inhibitors. J. Clin. Pathol. 2019, 72, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, B.J.H.; Schaal, D.L.; Nkadi, E.H.; Scott, R.S. EBV Association with Lymphomas and Carcinomas in the Oral Compartment. Viruses 2022, 14, 2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, J.; White, R.E.; Anderton, E.; Allday, M.J. Latent Epstein-Barr Virus Can Inhibit Apoptosis in B Cells by Blocking the Induction of NOXA Expression. PloS One 2011, 6, e28506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrecque, L.G.; Xue, S.A.; Kazembe, P.; Phillips, J.; Lampert, I.; Wedderburn, N.; Griffin, B.E. Expression of Epstein-Barr Virus Lytically Related Genes in African Burkitt’s Lymphoma: Correlation with Patient Response to Therapy. Int. J. Cancer 1999, 81, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, A.M.; Luftig, M.A. To Be or Not IIb: A Multi-Step Process for Epstein-Barr Virus Latency Establishment and Consequences for B Cell Tumorigenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfieri, C.; Birkenbach, M.; Kieff, E. Early Events in Epstein-Barr Virus Infection of Human B Lymphocytes. Virology 1991, 181, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikitin, P.A.; Yan, C.M.; Forte, E.; Bocedi, A.; Tourigny, J.P.; White, R.E.; Allday, M.J.; Patel, A.; Dave, S.S.; Kim, W.; et al. An ATM/Chk2-Mediated DNA Damage-Responsive Signaling Pathway Suppresses Epstein-Barr Virus Transformation of Primary Human B Cells. Cell Host Microbe 2010, 8, 510–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahir-McFarland, E.D.; Davidson, D.M.; Schauer, S.L.; Duong, J.; Kieff, E. NF-Kappa B Inhibition Causes Spontaneous Apoptosis in Epstein-Barr Virus-Transformed Lymphoblastoid Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000, 97, 6055–6060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesarman, E. Gammaherpesviruses and Lymphoproliferative Disorders. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2014, 9, 349–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorley-Lawson, D.A.; Gross, A. Persistence of the Epstein-Barr Virus and the Origins of Associated Lymphomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 1328–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kis, L.L.; Salamon, D.; Persson, E.K.; Nagy, N.; Scheeren, F.A.; Spits, H.; Klein, G.; Klein, E. IL-21 Imposes a Type II EBV Gene Expression on Type III and Type I B Cells by the Repression of C- and Activation of LMP-1-Promoter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 872–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babcock, G.J.; Decker, L.L.; Volk, M.; Thorley-Lawson, D.A. EBV Persistence in Memory B Cells in Vivo. Immunity 1998, 9, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruhne, B.; Sompallae, R.; Masucci, M.G. Three Epstein-Barr Virus Latency Proteins Independently Promote Genomic Instability by Inducing DNA Damage, Inhibiting DNA Repair and Inactivating Cell Cycle Checkpoints. Oncogene 2009, 28, 3997–4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yates, J.L.; Warren, N.; Sugden, B. Stable Replication of Plasmids Derived from Epstein-Barr Virus in Various Mammalian Cells. Nature 1985, 313, 812–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reisman, D.; Yates, J.; Sugden, B. A Putative Origin of Replication of Plasmids Derived from Epstein-Barr Virus Is Composed of Two Cis-Acting Components. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1985, 5, 1822–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.S.Z.; Abbasi, A.; Kim, D.H.; Lippman, S.M.; Alexandrov, L.B.; Cleveland, D.W. Chromosomal Fragile Site Breakage by EBV-Encoded EBNA1 at Clustered Repeats. Nature 2023, 616, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.I.; Wang, F.; Mannick, J.; Kieff, E. Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Protein 2 Is a Key Determinant of Lymphocyte Transformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1989, 86, 9558–9562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, S.R.; Johannsen, E.; Tong, X.; Yalamanchili, R.; Kieff, E. The Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Antigen 2 Transactivator Is Directed to Response Elements by the J Kappa Recombination Signal Binding Protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994, 91, 7568–7572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, S.; Kieff, E. Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Protein LP Stimulates EBNA-2 Acidic Domain-Mediated Transcriptional Activation. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 6611–6618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.-S.; Kieff, E. Epstein-Barr Virus Latent Genes. Exp. Mol. Med. 2015, 47, e131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancao, C.; Altmann, M.; Jungnickel, B.; Hammerschmidt, W. Rescue of “Crippled” Germinal Center B Cells from Apoptosis by Epstein-Barr Virus. Blood 2005, 106, 4339–4344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, S.; Rowe, M.; Gregory, C.; Croom-Carter, D.; Wang, F.; Longnecker, R.; Kieff, E.; Rickinson, A. Induction of Bcl-2 Expression by Epstein-Barr Virus Latent Membrane Protein 1 Protects Infected B Cells from Programmed Cell Death. Cell 1991, 65, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri-Broët, S.; Camparo, P.; Mokhtari, K.; Hoang-Xuan, K.H.; Martin, A.; Arborio, M.; Hauw, J.J.; Raphaël, M. Overexpression of BCL-2, BCL-X, and BAX in Primary Central Nervous System Lymphomas That Occur in Immunosuppressed Patients. Mod. Pathol. Off. J. U. S. Can. Acad. Pathol. Inc 2000, 13, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosialos, G.; Birkenbach, M.; Yalamanchili, R.; VanArsdale, T.; Ware, C.; Kieff, E. The Epstein-Barr Virus Transforming Protein LMP1 Engages Signaling Proteins for the Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor Family. Cell 1995, 80, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidry, J.; Birdwell, C.; Scott, R. Epstein–Barr Virus in the Pathogenesis of Oral Cancers. Oral Dis. 2018, 24, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliaro, M.; Massuh, D.; Infante, M.F.; Brahm, A.M.; San Martín, M.T.; Ortuño, D. Role of Epstein-Barr Virus and Human Papilloma Virus in the Development of Oropharyngeal Cancer: A Literature Review. Int. J. Dent. 2022, 2022, 3191569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, N.; Bagán, J.V.; Javier, K.; Zapater, E. Head and Neck Lymphomas in HIV Patients: A Clinical Perspective. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2017, 21, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, A. AIDS-Related Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphomas: From Pathology and Molecular Pathogenesis to Treatment. Hum. Pathol. 2002, 33, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, A.; Cattaneo, C.; Rossi, G. Hiv and Lymphoma: From Epidemiology to Clinical Management. Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 11, e2019004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirelli, U.; Spina, M.; Gaidano, G.; Vaccher, E.; Franceschi, S.; Carbone, A. Epidemiological, Biological and Clinical Features of HIV-Related Lymphomas in the Era of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy. AIDS Lond. Engl. 2000, 14, 1675–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 54. ENT Board Prep: High Yield Review for the Otolaryngology in-Service and Board Exams; Lin, F.Y., Patel, Z.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; ISBN 9783031260476. 55. Epeldegui, M.; Hussain, S.K. The Role of Microbial Translocation and Immune Activation in AIDS-Associated Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Pathogenesis: What Have We Learned? Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 40, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 56. Liang, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Guo, C.; Zhang, Y. Virus-Driven Dysregulation of the BCR Pathway: A Potential Mechanism for the High Prevalence of HIV Related B-Cell Lymphoma. Ann. Hematol. 2024. [CrossRef]

- 57. Dolcetti, R.; Gloghini, A.; Caruso, A.; Carbone, A. A Lymphomagenic Role for HIV beyond Immune Suppression? Blood 2016, 127, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 58. Pantanowitz, L.; Carbone, A.; Dolcetti, R. Microenvironment and HIV-Related Lymphomagenesis. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2015, 34, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 59. Doshi, D.V.; Tripathi, U.; Dave, R.I.; Pandya, S.J.; Shukla, H.K.; Parikh, B.C. Rare Tumors of Sinonasal Track. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. Off. Publ. Assoc. Otolaryngol. India 2010, 62, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 60. Das, S.; Kirsch, C.F.E. Imaging of Lumps and Bumps in the Nose: A Review of Sinonasal Tumours. Cancer Imaging 2005, 5, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 61. Bernardo, P.S.; Hancio, T.; Vasconcelos, F. da C.; Nestal de Moraes, G.; de Sá Bigni, R.; Wernersbach Pinto, L.; Thuler, L.C.S.; Maia, R.C. Primary Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma of the Head and Neck in a Brazilian Single-Center Study. Oral Dis. 2023, 29, 968–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 63. Shmakova, A.; Germini, D.; Vassetzky, Y. HIV-1, HAART and Cancer: A Complex Relationship. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 146, 2666–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 64. Thorley-Lawson, D.A.; Poodry, C.A. Identification and Isolation of the Main Component (Gp350-Gp220) of Epstein-Barr Virus Responsible for Generating Neutralizing Antibodies in Vivo. J. Virol. 1982, 43, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 65. North, J.R.; Morgan, A.J.; Thompson, J.L.; Epstein, M.A. Purified Epstein-Barr Virus Mr 340,000 Glycoprotein Induces Potent Virus-Neutralizing Antibodies When Incorporated in Liposomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1982, 79, 7504–7508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 66. Lewis, W.D.; Lilly, S.; Jones, K.L. Lymphoma: Diagnosis and Treatment. Am. Fam. Physician 2020, 101, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Cheson, B.D.; Fisher, R.I.; Barrington, S.F.; Cavalli, F.; Schwartz, L.H.; Zucca, E.; Lister, T.A.; Alliance, Australasian Leukaemia and Lymphoma Group; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Consortium; et al. Recommendations for Initial Evaluation, Staging, and Response Assessment of Hodgkin and Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: The Lugano Classification. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 3059–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 68. Saatci, D.; Zhu, C.; Harnden, A.; Hippisley-Cox, J. Presentation of B-Cell Lymphoma in Childhood and Adolescence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 69. Sparano, J.A. Clinical Aspects and Management of AIDS-Related Lymphoma. Eur. J. Cancer Oxf. Engl. 1990 2001, 37, 1296–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 70. Mozas, P.; Sorigué, M.; López-Guillermo, A. Follicular Lymphoma: An Update on Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Management. Med. Clin. (Barc.) 2021, 157, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 71. de Oliveira, E.M.; de Cáceres, C.V.B.L.; Santos-Silva, A.R.; Vargas, P.A.; Lopes, M.A.; Pontes, H.A.R.; Pontes, F.S.C.; Mesquita, R.A.; de Sousa, S.F.; Abreu, L.G.; et al. Clinical Diagnostic Approach for Oral Lymphomas: A Multi-Institutional, Observational Study Based on 107 Cases. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2023, 136, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 72. Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma of the Head and Neck in Association with HIV Infection - PubMed Available online:. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8999746/ (accessed on 7 December 2024).

- 73. Finn, D.G. Lymphoma of the Head and Neck and Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome: Clinical Investigation and Immunohistological Study. The Laryngoscope 1995, 105, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 74. Cheson, B.D.; Fisher, R.I.; Barrington, S.F.; Cavalli, F.; Schwartz, L.H.; Zucca, E.; Lister, T.A.; Alliance, Australasian Leukaemia and Lymphoma Group; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Consortium; et al. Recommendations for Initial Evaluation, Staging, and Response Assessment of Hodgkin and Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: The Lugano Classification. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 3059–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 75. Lewis, W.D.; Lilly, S.; Jones, K.L. Lymphoma: Diagnosis and Treatment. Am. Fam. Physician 2020, 101, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wilczynski, A.; Görg, C.; Timmesfeld, N.; Ramaswamy, A.; Neubauer, A.; Burchert, A.; Trenker, C. Value and Diagnostic Accuracy of Ultrasound-Guided Full Core Needle Biopsy in the Diagnosis of Lymphadenopathy: A Retrospective Evaluation of 793 Cases. J. Ultrasound Med. Off. J. Am. Inst. Ultrasound Med. 2020, 39, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 77. Cuenca-Jimenez, T.; Chia, Z.; Desai, A.; Moody, A.; Ramesar, K.; Grace, R.; Howlett, D.C. The Diagnostic Performance of Ultrasound-Guided Core Biopsy in the Diagnosis of Head and Neck Lymphoma: Results in 226 Patients. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 50, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 78. Groneck, L.; Quaas, A.; Hallek, M.; Zander, T.; Weihrauch, M.R. Ultrasound-Guided Core Needle Biopsies for Workup of Lymphadenopathy and Lymphoma. Eur. J. Haematol. 2016, 97, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 79. Ribeiro, A.; Pereira, D.; Escalón, M.P.; Goodman, M.; Byrne, G.E. EUS-Guided Biopsy for the Diagnosis and Classification of Lymphoma. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2010, 71, 851–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 80. Groneck, L.; Quaas, A.; Hallek, M.; Zander, T.; Weihrauch, M.R. Ultrasound-Guided Core Needle Biopsies for Workup of Lymphadenopathy and Lymphoma. Eur. J. Haematol. 2016, 97, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 81. Oluwasanmi, A.F.; Wood, S.J.; Baldwin, D.L.; Sipaul, F. Malignancy in Asymmetrical but Otherwise Normal Palatine Tonsils. Ear. Nose. Throat J. 2006, 85, 661–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 82. Edwards, D.; Sheehan, S.; Ingrams, D. Unilateral Tonsil Enlargement in Children and Adults: Is Routine Histology Tonsillectomy Warranted? A Multi-Centre Series of 323 Patients. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2023, 137, 1022–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 83. Kemp, S.; Gallagher, G.; Kabani, S.; Noonan, V.; O’Hara, C. Oral Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: Review of the Literature and World Health Organization Classification with Reference to 40 Cases. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2008, 105, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 84. Levine, A.M. Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome-Related Lymphoma. Blood 1992, 80, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 85. Corti, M.; Villafañe, M.; Bistmans, A.; Narbaitz, M.; Gilardi, L. Primary Extranodal Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma of the Head and Neck in Patients with Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome: A Clinicopathologic Study of 24 Patients in a Single Hospital of Infectious Diseases in Argentina. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2014, 18, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 86. Geser, A.; de Thé, G.; Lenoir, G.; Day, N.E.; Williams, E.H. Final Case Reporting from the Ugandan Prospective Study of the Relationship between EBV and Burkitt’s Lymphoma. Int. J. Cancer 1982, 29, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 87. Expression of Epstein-Barr Virus-Encoded Small RNA (by the EBER-1 Gene) in Liver Specimens from Transplant Recipients with Post-Transplantation Lymphoproliferative Disease - PubMed Available online:. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1331789/ (accessed on 7 December 2024).

- 88. Bruu, A.L.; Hjetland, R.; Holter, E.; Mortensen, L.; Natås, O.; Petterson, W.; Skar, A.G.; Skarpaas, T.; Tjade, T.; Asjø, B. Evaluation of 12 Commercial Tests for Detection of Epstein-Barr Virus-Specific and Heterophile Antibodies. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2000, 7, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 89. Mundo, L.; Ambrosio, M.R.; Picciolini, M.; Lo Bello, G.; Gazaneo, S.; Del Porro, L.; Lazzi, S.; Navari, M.; Onyango, N.; Granai, M.; et al. Unveiling Another Missing Piece in EBV-Driven Lymphomagenesis: EBV-Encoded MicroRNAs Expression in EBER-Negative Burkitt Lymphoma Cases. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 90. Qi, Z.-L.; Han, X.-Q.; Hu, J.; Wang, G.-H.; Gao, J.-W.; Wang, X.; Liang, D.-Y. Comparison of Three Methods for the Detection of Epstein-Barr Virus in Hodgkin’s Lymphoma in Paraffin-Embedded Tissues. Mol. Med. Rep. 2013, 7, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 91. Zapater, E.; Bagán, J.V.; Carbonell, F.; Basterra, J. Malignant Lymphoma of the Head and Neck. Oral Dis. 2010, 16, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 92. SH, S.; E, C.; NL, H.; ES, J.; SA, P.; H, S.; J, T. 92. SH, S.; E, C.; NL, H.; ES, J.; SA, P.; H, S.; J, T. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues; ISBN 978-92-832-4494-3.

- 93. Boué, F.; Gabarre, J.; Gisselbrecht, C.; Reynes, J.; Cheret, A.; Bonnet, F.; Billaud, E.; Raphael, M.; Lancar, R.; Costagliola, D. Phase II Trial of CHOP plus Rituximab in Patients with HIV-Associated Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 4123–4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 94. Ribera, J.-M.; Oriol, A.; Morgades, M.; González-Barca, E.; Miralles, P.; López-Guillermo, A.; Gardella, S.; López, A.; Abella, E.; García, M.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Cyclophosphamide, Adriamycin, Vincristine, Prednisone and Rituximab in Patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Associated Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: Results of a Phase II Trial. Br. J. Haematol. 2008, 140, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 95. Little, R.F.; Pittaluga, S.; Grant, N.; Steinberg, S.M.; Kavlick, M.F.; Mitsuya, H.; Franchini, G.; Gutierrez, M.; Raffeld, M.; Jaffe, E.S.; et al. Highly Effective Treatment of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome-Related Lymphoma with Dose-Adjusted EPOCH: Impact of Antiretroviral Therapy Suspension and Tumor Biology. Blood 2003, 101, 4653–4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 96. Barta, S.K.; Lee, J.Y.; Kaplan, L.D.; Noy, A.; Sparano, J.A. Pooled Analysis of AIDS Malignancy Consortium Trials Evaluating Rituximab plus CHOP or Infusional EPOCH Chemotherapy in HIV-Associated Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Cancer 2012, 118, 3977–3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 97. Wang, E.S.; Straus, D.J.; Teruya-Feldstein, J.; Qin, J.; Portlock, C.; Moskowitz, C.; Goy, A.; Hedrick, E.; Zelenetz, A.D.; Noy, A. Intensive Chemotherapy with Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, High-Dose Methotrexate/Ifosfamide, Etoposide, and High-Dose Cytarabine (CODOX-M/IVAC) for Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Associated Burkitt Lymphoma. Cancer 2003, 98, 1196–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 98. Barnes, J.A.; Lacasce, A.S.; Feng, Y.; Toomey, C.E.; Neuberg, D.; Michaelson, J.S.; Hochberg, E.P.; Abramson, J.S. Evaluation of the Addition of Rituximab to CODOX-M/IVAC for Burkitt’s Lymphoma: A Retrospective Analysis. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2011, 22, 1859–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 99. Noy, A.; Kaplan, L.; Lee, J.; Cesarman, E.; Tam, W. Modified Dose Intensive R- CODOX-M/IVAC for HIV-Associated Burkitt (BL) (AMC 048) Shows Efficacy and Tolerability, and Predictive Potential of IRF4/MUM1 Expression. Infect. Agent. Cancer 2012, 7, O14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 100. Cortes, J.; Thomas, D.; Rios, A.; Koller, C.; O’Brien, S.; Jeha, S.; Faderl, S.; Kantarjian, H. Hyperfractionated Cyclophosphamide, Vincristine, Doxorubicin, and Dexamethasone and Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy for Patients with Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome-Related Burkitt Lymphoma/Leukemia. Cancer 2002, 94, 1492–1499. [CrossRef]

- 101. Samra, B.; Khoury, J.D.; Morita, K.; Ravandi, F.; Richard-Carpentier, G.; Short, N.J.; El Hussein, S.; Thompson, P.; Jain, N.; Kantarjian, H.; et al. Long-Term Outcome of Hyper-CVAD-R for Burkitt Leukemia/Lymphoma and High-Grade B-Cell Lymphoma: Focus on CNS Relapse. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 3913–3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 102. Thomas, D.A.; Faderl, S.; O’Brien, S.; Bueso-Ramos, C.; Cortes, J.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Giles, F.J.; Verstovsek, S.; Wierda, W.G.; Pierce, S.A.; et al. Chemoimmunotherapy with Hyper-CVAD plus Rituximab for the Treatment of Adult Burkitt and Burkitt-Type Lymphoma or Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancer 2006, 106, 1569–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 103. Sparano, J.A.; Lee, S.; Chen, M.G.; Nazeer, T.; Einzig, A.; Ambinder, R.F.; Henry, D.H.; Manalo, J.; Li, T.; Von Roenn, J.H. Phase II Trial of Infusional Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, and Etoposide in Patients with HIV-Associated Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: An Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial (E1494). J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 1491–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 104. Spina, M.; Jaeger, U.; Sparano, J.A.; Talamini, R.; Simonelli, C.; Michieli, M.; Rossi, G.; Nigra, E.; Berretta, M.; Cattaneo, C.; et al. Rituximab plus Infusional Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, and Etoposide in HIV-Associated Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: Pooled Results from 3 Phase 2 Trials. Blood 2005, 105, 1891–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 105. Hentrich, M.; Berger, M.; Wyen, C.; Siehl, J.; Rockstroh, J.K.; Müller, M.; Fätkenheuer, G.; Seidel, E.; Nickelsen, M.; Wolf, T.; et al. Stage-Adapted Treatment of HIV-Associated Hodgkin Lymphoma: Results of a Prospective Multicenter Study. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 4117–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 106. Kim, W.S.; Song, S.Y.; Ahn, Y.C.; Ko, Y.H.; Baek, C.H.; Kim, D.Y.; Yoon, S.S.; Lee, H.G.; Kang, W.K.; Lee, H.J.; et al. CHOP Followed by Involved Field Radiation: Is It Optimal for Localized Nasal Natural Killer/T-Cell Lymphoma? Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2001, 12, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 107. Yamaguchi, M.; Tobinai, K.; Oguchi, M.; Ishizuka, N.; Kobayashi, Y.; Isobe, Y.; Ishizawa, K.; Maseki, N.; Itoh, K.; Usui, N.; et al. Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy for Localized Nasal Natural Killer/T-Cell Lymphoma: An Updated Analysis of the Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study JCOG0211. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 4044–4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 108. Jiang, M.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Xie, L.; Liu, W.; Zhang, W.; Ji, X.; Li, P.; Chen, N.; et al. Phase 2 Trial of “Sandwich” L-Asparaginase, Vincristine, and Prednisone Chemotherapy with Radiotherapy in Newly Diagnosed, Stage IE to IIE, Nasal Type, Extranodal Natural Killer/T-Cell Lymphoma. Cancer 2012, 118, 3294–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 109. Kim, S.J.; Kim, K.; Kim, B.S.; Kim, C.Y.; Suh, C.; Huh, J.; Lee, S.-W.; Kim, J.S.; Cho, J.; Lee, G.-W.; et al. Phase II Trial of Concurrent Radiation and Weekly Cisplatin Followed by VIPD Chemotherapy in Newly Diagnosed, Stage IE to IIE, Nasal, Extranodal NK/T-Cell Lymphoma: Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma Study. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 6027–6032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 110. Kim, S.J.; Yoon, S.E.; Kim, W.S. Treatment of Localized Extranodal NK/T Cell Lymphoma, Nasal Type: A Systematic Review. J. Hematol. Oncol.J Hematol Oncol 2018, 11, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 111. Torne, A.S.; Robertson, E.S. Epigenetic Mechanisms in Latent Epstein-Barr Virus Infection and Associated Cancers. Cancers 2024, 16, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 112. Pei, Y.; Banerjee, S.; Jha, H.C.; Sun, Z.; Robertson, E.S. An Essential EBV Latent Antigen 3C Binds Bcl6 for Targeted Degradation and Cell Proliferation. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 113. Souers, A.J.; Leverson, J.D.; Boghaert, E.R.; Ackler, S.L.; Catron, N.D.; Chen, J.; Dayton, B.D.; Ding, H.; Enschede, S.H.; Fairbrother, W.J.; et al. ABT-199, a Potent and Selective BCL-2 Inhibitor, Achieves Antitumor Activity While Sparing Platelets. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 114. Price, A.M.; Dai, J.; Bazot, Q.; Patel, L.; Nikitin, P.A.; Djavadian, R.; Winter, P.S.; Salinas, C.A.; Barry, A.P.; Wood, K.C.; et al. Epstein-Barr Virus Ensures B Cell Survival by Uniquely Modulating Apoptosis at Early and Late Times after Infection. eLife 2017, 6, e22509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 115. Desbien, A.L.; Kappler, J.W.; Marrack, P. The Epstein-Barr Virus Bcl-2 Homolog, BHRF1, Blocks Apoptosis by Binding to a Limited Amount of Bim. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009, 106, 5663–5668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 116. Procko, E.; Berguig, G.Y.; Shen, B.W.; Song, Y.; Frayo, S.; Convertine, A.J.; Margineantu, D.; Booth, G.; Correia, B.E.; Cheng, Y.; et al. A Computationally Designed Inhibitor of an Epstein-Barr Viral Bcl-2 Protein Induces Apoptosis in Infected Cells. Cell 2014, 157, 1644–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 117. Zidovudine-Based Lytic-Inducing Chemotherapy for Epstein-Barr Virus-Related Lymphomas - PubMed Available online:. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23837493/ (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- 118. Roychowdhury, S.; Peng, R.; Baiocchi, R.A.; Bhatt, D.; Vourganti, S.; Grecula, J.; Gupta, N.; Eisenbeis, C.F.; Nuovo, G.J.; Yang, W.; et al. Experimental Treatment of Epstein-Barr Virus-Associated Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 965–971. [Google Scholar]

- 119. Slobod, K.S.; Taylor, G.H.; Sandlund, J.T.; Furth, P.; Helton, K.J.; Sixbey, J.W. Epstein-Barr Virus-Targeted Therapy for AIDS-Related Primary Lymphoma of the Central Nervous System. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2000, 356, 1493–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 120. Ganguly, S.; Kuravi, S.; Alleboina, S.; Mudduluru, G.; Jensen, R.A.; McGuirk, J.P.; Balusu, R. Targeted Therapy for EBV-Associated B-Cell Neoplasms. Mol. Cancer Res. MCR 2019, 17, 839–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 121. Spleen Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor TAK-659 Prevents Splenomegaly and Tumor Development in a Murine Model of Epstein-Barr Virus-Associated Lymphoma - PubMed Available online:. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30135222/ (accessed on 7 December 2024).

- 122. Lu, J.; Lin, W.-H.; Chen, S.-Y.; Longnecker, R.; Tsai, S.-C.; Chen, C.-L.; Tsai, C.-H. Syk Tyrosine Kinase Mediates Epstein-Barr Virus Latent Membrane Protein 2A-Induced Cell Migration in Epithelial Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 8806–8814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 123. Chang, L.-K.; Liu, S.-T. Activation of the BRLF1 Promoter and Lytic Cycle of Epstein–Barr Virus by Histone Acetylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 3918–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 124. zur Hausen, H.; O’Neill, F.J.; Freese, U.K.; Hecker, E. Persisting Oncogenic Herpesvirus Induced by the Tumour Promotor TPA. Nature 1978, 272, 373–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 125. Westphal, E.M.; Blackstock, W.; Feng, W.; Israel, B.; Kenney, S.C. Activation of Lytic Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) Infection by Radiation and Sodium Butyrate in Vitro and in Vivo: A Potential Method for Treating EBV-Positive Malignancies. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 5781–5788. [Google Scholar]

- 126. Luka, J.; Kallin, B.; Klein, G. Induction of the Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) Cycle in Latently Infected Cells by n-Butyrate. Virology 1979, 94, 228–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 127. Tovey, M.G.; Lenoir, G.; Begon-Lours, J. Activation of Latent Epstein-Barr Virus by Antibody to Human IgM. Nature 1978, 276, 270–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 128. Shimizu, N.; Takada, K. Analysis of the BZLF1 Promoter of Epstein-Barr Virus: Identification of an Anti-Immunoglobulin Response Sequence. J. Virol. 1993, 67, 3240–3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 129. Perrine, S.P.; Hermine, O.; Small, T.; Suarez, F.; O’Reilly, R.; Boulad, F.; Fingeroth, J.; Askin, M.; Levy, A.; Mentzer, S.J.; et al. A Phase 1/2 Trial of Arginine Butyrate and Ganciclovir in Patients with Epstein-Barr Virus-Associated Lymphoid Malignancies. Blood 2007, 109, 2571–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 130. Faller, D.V.; Mentzer, S.J.; Perrine, S.P. Induction of the Epstein-Barr Virus Thymidine Kinase Gene with Concomitant Nucleoside Antivirals as a Therapeutic Strategy for Epstein-Barr Virus-Associated Malignancies. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2001, 13, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 131. Meng, Q.; Hagemeier, S.R.; Fingeroth, J.D.; Gershburg, E.; Pagano, J.S.; Kenney, S.C. The Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV)-Encoded Protein Kinase, EBV-PK, but Not the Thymidine Kinase (EBV-TK), Is Required for Ganciclovir and Acyclovir Inhibition of Lytic Viral Production. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 4534–4542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 132. Jiang, Z.; Li, W.; Hu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, T.; Cui, S.; Wang, S.; Ouyang, Q.; Yin, Y.; Geng, C.; et al. Tucidinostat plus Exemestane for Postmenopausal Patients with Advanced, Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer (ACE): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 806–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 133. Eckschlager, T.; Plch, J.; Stiborova, M.; Hrabeta, J. Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors as Anticancer Drugs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 134. Lai, J.; Tan, W.J.; Too, C.T.; Choo, J.A.L.; Wong, L.H.; Mustafa, F.B.; Srinivasan, N.; Lim, A.P.C.; Zhong, Y.; Gascoigne, N.R.J.; et al. Targeting Epstein-Barr Virus-Transformed B Lymphoblastoid Cells Using Antibodies with T-Cell Receptor-like Specificities. Blood 2016, 128, 1396–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 135. Lai, J.; Choo, J.A.L.; Tan, W.J.; Too, C.T.; Oo, M.Z.; Suter, M.A.; Mustafa, F.B.; Srinivasan, N.; Chan, C.E.Z.; Lim, A.G.X.; et al. TCR-like Antibodies Mediate Complement and Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity against Epstein-Barr Virus-Transformed B Lymphoblastoid Cells Expressing Different HLA-A*02 Microvariants. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 136. Bu, W.; Kumar, A.; Board, N.L.; Kim, J.; Dowdell, K.; Zhang, S.; Lei, Y.; Hostal, A.; Krogmann, T.; Wang, Y.; et al. Epstein-Barr Virus Gp42 Antibodies Reveal Sites of Vulnerability for Receptor Binding and Fusion to B Cells. Immunity 2024, 57, 559–573.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 137. Chen, W.-H.; Kim, J.; Bu, W.; Board, N.L.; Tsybovsky, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hostal, A.; Andrews, S.F.; Gillespie, R.A.; Choe, M.; et al. Epstein-Barr Virus gH/gL Has Multiple Sites of Vulnerability for Virus Neutralization and Fusion Inhibition. Immunity 2022, 55, 2135–2148.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 138. Snijder, J.; Ortego, M.S.; Weidle, C.; Stuart, A.B.; Gray, M.D.; McElrath, M.J.; Pancera, M.; Veesler, D.; McGuire, A.T. An Antibody Targeting the Fusion Machinery Neutralizes Dual-Tropic Infection and Defines a Site of Vulnerability on Epstein-Barr Virus. Immunity 2018, 48, 799–811.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 139. He, H.; Lei, F.; Huang, L.; Wang, K.; Yang, Y.; Chen, L.; Peng, Y.; Liang, Y.; Tan, H.; Wu, X.; et al. Immunotherapy of Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) Infection and EBV-Associated Hematological Diseases with Gp350/CD89-Targeted Bispecific Antibody. Biomed. Pharmacother. Biomedecine Pharmacother. 2023, 163, 114797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 140. Hermans, J.; Krol, A.D.; van Groningen, K.; Kluin, P.M.; Kluin-Nelemans, J.C.; Kramer, M.H.; Noordijk, E.M.; Ong, F.; Wijermans, P.W. International Prognostic Index for Aggressive Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Is Valid for All Malignancy Grades. Blood 1995, 86, 1460–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 141. Tirelli, U.; Spina, M.; Gaidano, G.; Vaccher, E.; Franceschi, S.; Carbone, A. Epidemiological, Biological and Clinical Features of HIV-Related Lymphomas in the Era of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy. AIDS Lond. Engl. 2000, 14, 1675–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 142. Aanaes, K.; Kristensen, E.; Ralfkiaer, E.M.; von Buchwald, C.; Specht, L. Improved Prognosis for Localized Malignant Lymphomas of the Head and Neck. Acta Otolaryngol. (Stockh.) 2010, 130, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 143. Kwak, Y.-K.; Choi, B.-O.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, J.H.; Kang, D.G.; Lee, J.H. Treatment Outcome of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Involving the Head and Neck: Two-Institutional Study for the Significance of Radiotherapy after R-CHOP Chemotherapy. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017, 96, e7268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 144. Lv, J.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, T.; Gao, S.; Yin, W. Clinical Characteristics and Prognostic Analysis of Primary Extranodal Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma of the Head and Neck. Aging 2024, 16, 6796–6808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 145. Zhou, C.; Duan, X.; Lan, B.; Liao, J.; Shen, J. Prognostic CT and MR Imaging Features in Patients with Untreated Extranodal Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma of the Head and Neck Region. Eur. Radiol. 2015, 25, 3035–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 146. Scully, C. Oral Cancer: New Insights into Pathogenesis. Dent. Update 1993, 20, 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- 147. Scully, C. Oncogenes, Tumor Suppressors and Viruses in Oral Squamous Carcinoma. J. Oral Pathol. Med. Off. Publ. Int. Assoc. Oral Pathol. Am. Acad. Oral Pathol. 1993, 22, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 148. Feigal, E.G. AIDS-Associated Malignancies: Research Perspectives. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1999, 1423, C1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 149. Goldenberg, D.; Golz, A.; Netzer, A.; Rosenblatt, E.; Rachmiel, A.; Goldenberg, R.F.; Joachims, H.Z. Epstein-Barr Virus and Cancers of the Head and Neck. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2001, 22, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 150. Tvedten, E.; Richardson, J.; Motaparthi, K. What Effect Does Epstein-Barr Virus Have on Extranodal Natural Killer/T-Cell Lymphoma Prognosis? A Review of 153 Reported Cases. Cureus 2021, 13, e17987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 151. Hu, J.; Zhang, X.; Tao, H.; Jia, Y. The Prognostic Value of Epstein-Barr Virus Infection in Hodgkin Lymphoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1034398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 152. Bower, M.; Gazzard, B.; Mandalia, S.; Newsom-Davis, T.; Thirlwell, C.; Dhillon, T.; Young, A.M.; Powles, T.; Gaya, A.; Nelson, M.; et al. A Prognostic Index for Systemic AIDS-Related Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Treated in the Era of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy. Ann. Intern. Med. 2005, 143, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 153. Barta, S.K.; Samuel, M.S.; Xue, X.; Wang, D.; Lee, J.Y.; Mounier, N.; Ribera, J.-M.; Spina, M.; Tirelli, U.; Weiss, R.; et al. Changes in the Influence of Lymphoma- and HIV-Specific Factors on Outcomes in AIDS-Related Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2015, 26, 958–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 154. Castillo, J.J.; Bower, M.; Brühlmann, J.; Novak, U.; Furrer, H.; Tanaka, P.Y.; Besson, C.; Montoto, S.; Cwynarski, K.; Abramson, J.S.; et al. Prognostic Factors for Advanced-Stage Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Associated Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma Treated with Doxorubicin, Bleomycin, Vinblastine, and Dacarbazine plus Combined Antiretroviral Therapy: A Multi-Institutional Retrospective Study. Cancer 2015, 121, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| EBNA1 | Replication and segregation, resistance to apoptosis by degrading p53, increases reactive oxygen species and causes genomic instability [30,33,34,35]. Li et al showed that EBNA 1 binds to a specific palindromic DNA sequence on chromosome 11 resulting in breaks and genome instability [36]. |

| EBNA 2 | Essential for B immortalization[30,33] EBNA2 upregulates LMP1 expression [18,33,37,38] |

| EBNA 3A/C | Promotes bypasses cell cycle checkpoints that increase proliferation and genomic instability [30,33] |

| EBNA 3B | Tumor supressor activity [30,33] |

| EBNALP | Co-activator of EBNA 2[30,33,39,40] |

| LMP1 | Mimics CD40 receptor signaling, Activates NF-kB/MAPK/JAK-STAT/PI3K signaling, promotes proliferation and survival [30,33,40,41] LMP-1 viral oncogene has transforming ability in isolation and induces DNA synthesis in human B cells[42], also protects EBV infected cells from apoptosis through regulation of bcl-2 and related proteins [43]. Activates b lymphocytes by receptor CD40 [44]. |

| LMP2A/B | Mimics host B cell receptor signaling [30,33]. |

| EBER1 | Resistance to apoptosis [30,33]. |

| BART | MicroRNAs increase resistance to apoptosis [30,33]. |

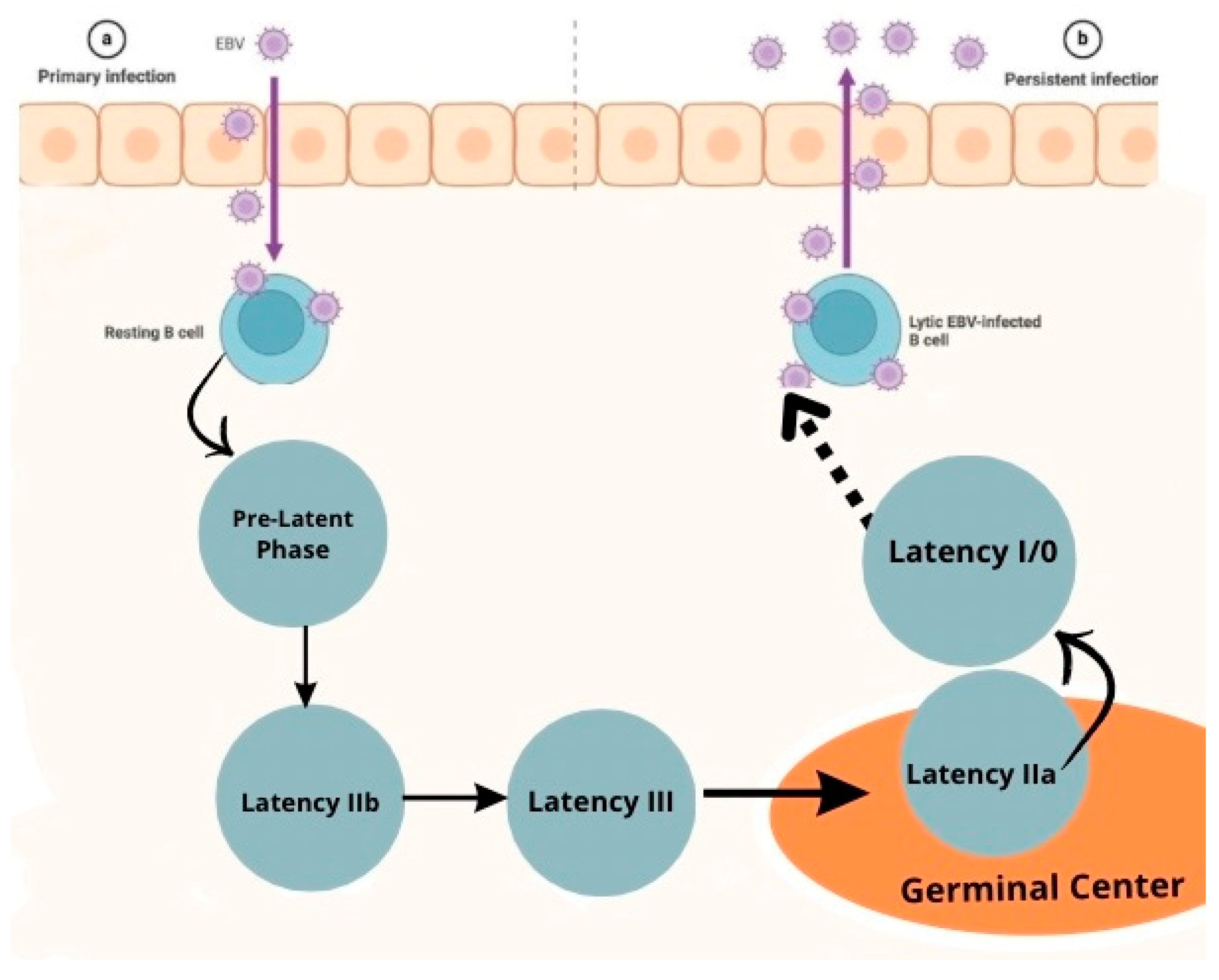

| Pre-Latency | Noncoding RNA: EBERs, BHRF1 mRNAs, BART mi RNAs mRNAS: EBNA-LP, EBNA2, Wp-BHRF1 (vBcl2) |

| Latency IIb | Noncoding RNA: EBERs, BHRF1 miRNAs, BART miRNAS mRNAS: EBNA-LP, EBNA2, EBNA3s, EBNA 1, Wp-BHRF1 (vBcl2) |

|

Latency III |

Noncodig RNA: EBERs, BHRF1 miRNAs, BART miRNAS mRNAs: EBNA-LP, EBNA2, EBNA3s, EBNA 1, LMP1, LMP2A, LMP2B, Wp-BHRF1 (vBcl2) |

| Latency IIa | Noncoding RNA: EBERs, BART miRNAs mRNAs: EBNA1, LMP1, LMP2A, LMP2B |

| Latency I | Noncoding RNA: EBERs, BART miRNAs mRNAs: EBNA1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).