1. Introduction

Globally, the epidemic with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) is ongoing, with an estimated of 39.9 million of people living with HIV (PLWH) [

1].

Nowadays, due to the huge scientific advances in the understanding of the viral pathways, as well as diagnosis, treatment and prevention, HIV has become a chronic, manageable disease, with long-life expectancy. However, there is no cure available strategy in the public health. The persistent viral inflammation in PLWH is related to frailty, in terms of precocious aging and frequent additional chronic conditions, as cardiovascular, kidney, bone diseases and various cancers [

2].

The HIV persistent viral complete suppression under the effective antiretroviral therapies decreased the opportunistic infections and neoplasms associated with severe acquired immunodepression syndrome (AIDS). As an AIDS indicator, the non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) continues to be the most common type of cancer and a leading cause of mortality in PLWH. Furthermore, the Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is AIDS independent, but it is reported increasing incidence in PLWH [

3].

NHL is the 12th most common cancer worldwide, with a global incidence of 5.6 cases per 100,000 people in 2022, while HL is ranking 26th and a much lower incidence, of 0.95 cases per 100,000 people [

4]. The incidence of NHL and HL in people living with HIV (PLWH) is 10 to 20-fold higher related to the general population, but the clinical features, and prognostic factors remain poorly differentiated from non-HIV lymphoma [

5,

6].

Some types of lymphomas, such as primary diffuse lymphoma or primary cerebral lymphoma, are opportunistic diseases indicators for classification in the AIDS stage [

7,

8]. More than 40% of HIV-infected patients are lastly diagnosed with AIDS-related lymphomas, and 28% of HIV-related deaths are attributed to malignancies [

9].

In developed countries, NHL is the most common cause of death associated with HIV infection, accounting for 23% to 30% of all AIDS-related deaths. HIV related NHLs occurs in patients with advanced HIV infection with T-lymphocytes (CD4+) count less than 100 cells/μL and a high HIV viral load [

10].

HL is the most common type of cancer in HIV-positive patients, not associated with AIDS. HL in non-HIV patients has a bimodal age distribution with an initial peak at 20–30 years and a second peak at 50–65 years, while the mean age of presentation of HL in HIV positive patients it is 41 years in European countries and 34 years in African countries [

11,

12]

. Globally, 0.4% of new cancer cases and 0.2% of cancer-related deaths were due to HL in 2020 [

13]. The incidence of HL varies by sex, age, and geographic location. People at higher risk for HL include men, adolescents and young adults, those with a history of Epstein-Barr virus infection, HIV/AIDS, autoimmune diseases, exposure to pollution, smoking and family history [

14,

15,

16].

The most common histologic types of HIV-associated lymphomas are diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL; 37%), HL (26%), and Burkitt lymphoma (BL; 20%). Low CD4+ T cell counts and HIV-1 viral replication (VL) are independent risk factors for DLBCL in people living with HIV [

17]. Other types, such as primary effusion lymphoma (PEL), primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) and plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) are less common [

18,

19]

The GLOBOCAN database, designed by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), contains projected national cancer estimates up to 2024 derived from the best available recorded data from national (or subnational) cancer registries and national centralized registry systems in 185 countries or territories of the world [

4,

20,

21].

There are few data on HIV-associated lymphomas in the population of Romania.

The two objectives of the present study are to evaluate the frequency and mortality of Lymphomas in HIV/AIDS patients in a single centre from Romania and to characterize the patients with co-morbid condition involving HIV/AIDS and lymphomas.

2. Materials and Methods

Our study has been retrospectively assessed the database of the patients with HIV/AIDS recorded in Infectious Diseases Clinic Hospital Galati, that is the single center for PLWH in Galati district. Our center is placed on the South-East border of Romania, providing health care for PLWH, related to an estimated general population of 600,000 people.

The HIV/AIDS database was achieved from the Clinic Hospital for Infectious Diseases Galati electronic database, by selected the diagnostic related-group codes B.20-24, from the 1st of January 2008 to 31 December 2022 [

22]. Additionally, we have identified the HIV patients with lymphomas, by the diagnostic code B.21.1, B.21.2 or B.21.3. All the cases were revised in December 2023, covering at least one year HIV follow-up. The cases were categorized as following: retinted in care (patients continuing to be monitored and treated in the center), deaths and loosed from follow-up (patients with no updated information).

The endpoint of the study was death or 31 December 2023, if the patient was a survivor, retinted in care.

The frequency of lymphomas in PLWH was calculated by dividing the number of HIV and lymphoma cases by the total number of HIV diagnosed cases, during the study time. Mortality was calculated among patients with HIV and lymphomas and was compared with mortality among the cases with HIV only.

To achieve the second objective, we have selected from the previous report the cases with HIV and lymphoma, and we have studied their detailed medical files.

We have analyzed the demographic data, HIV history and lymphoma history. We looked if the lymphoma diagnostic was an indicator of immunosuppression conducting to HIV testing. The HIV history comprised the pattern of transmission, age and year of diagnostic, staging on HIV diagnostic, co-infections, nadir of CD4-count, antiretroviral treatment (ART) experience. The staging of HIV cases was according to CDC classification [

23]. Nadir of CD4-count means the lowest ever count in an individual with HIV. Antiretroviral therapy was used according to the timeline versions of European guidelines, combining nucleoside(tide) reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), protease inhibitor (PI) or integrase inhibitor class (II) [

24].

Characterization of lymphoma considered the year of diagnostic, concomitant CD4 count, staging of lymphoma, histopathology, oncologic treatment, major complications and co-morbidities. The diagnostic of lymphoma was based on the anatomo-pathological examination and immunohistochemistry.

The lymphomas were staged according to the Ann Arbor classification system. The Ann Arbor staging system classifies HL and NHL by disease extent: stage I (single lymph node region), stage II (multiple lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm), stage III (lymph nodes on both sides of the diaphragm), stage IV (diffuse or disseminated involvement of one or more extra lymphatic organs, or either involvement of liver, bone marrow or lungs). Each stage is subdivided into: A (no systemic symptoms), B (systemic symptoms - fever exceeding 38°C without a known cause, severe night sweats, or weight loss greater than 10% of body weight within the six months before diagnosis), E (Involvement outside the lymphatic system), S (spleen involvement), bulky disease (for HL definition of bulk is any single node or nodal mass with diameter

≥ 10 cm or mediastinal mass ratio (maximum width of mediastinal mass/maximum intrathoracic diameter) > 0.33; for DLBCL bulky disease means any nodal or extra nodal tumor mass with a diameter of ≥ 7.5 cm) [

19,

25].

Statistical analyze employed Kaplan Meier (K-M) survival analysis. To conduct univariate approach of K-M, we divided the patients into two groups: one group consisting of patients with HIV and lymphoma versus another group with HIV only. Incomplete observations of patients for any reason were censored. The log-rank test was used to compare the survival estimates between-group, considering a significant p value lower than 0.05. We used SPSS software package version 26 for Kaplan-Meier survival curve analysis of both groups. We have analyzed the characteristics of patients with HIV and HL or NHL by two-samples-test for small sample size.

3. Results

3.1. The Frequency and Mortality of HIV/AIDS Associated Lymphomas

During 2008-2023, a number of 476 PLWH were monitored in our centre. From them, 366 are alived, 65 were died and 45 were lost from followup. Thus, the overall death rate was 15,08 %.

Between all PLWH we have identified 9 cases with lymphomas, specified as 7 NHL and 2 HL, meaning 1,89 % prevalence of lymphomas co-morbidity. There were reported 7 died PLWH diagnosed with lymphomas, accounting 10.76 % of all deaths. The mortality rate of HIV-associated lymphomas was 77,7 %, compared with 13.74% deaths found in HIV-only group.

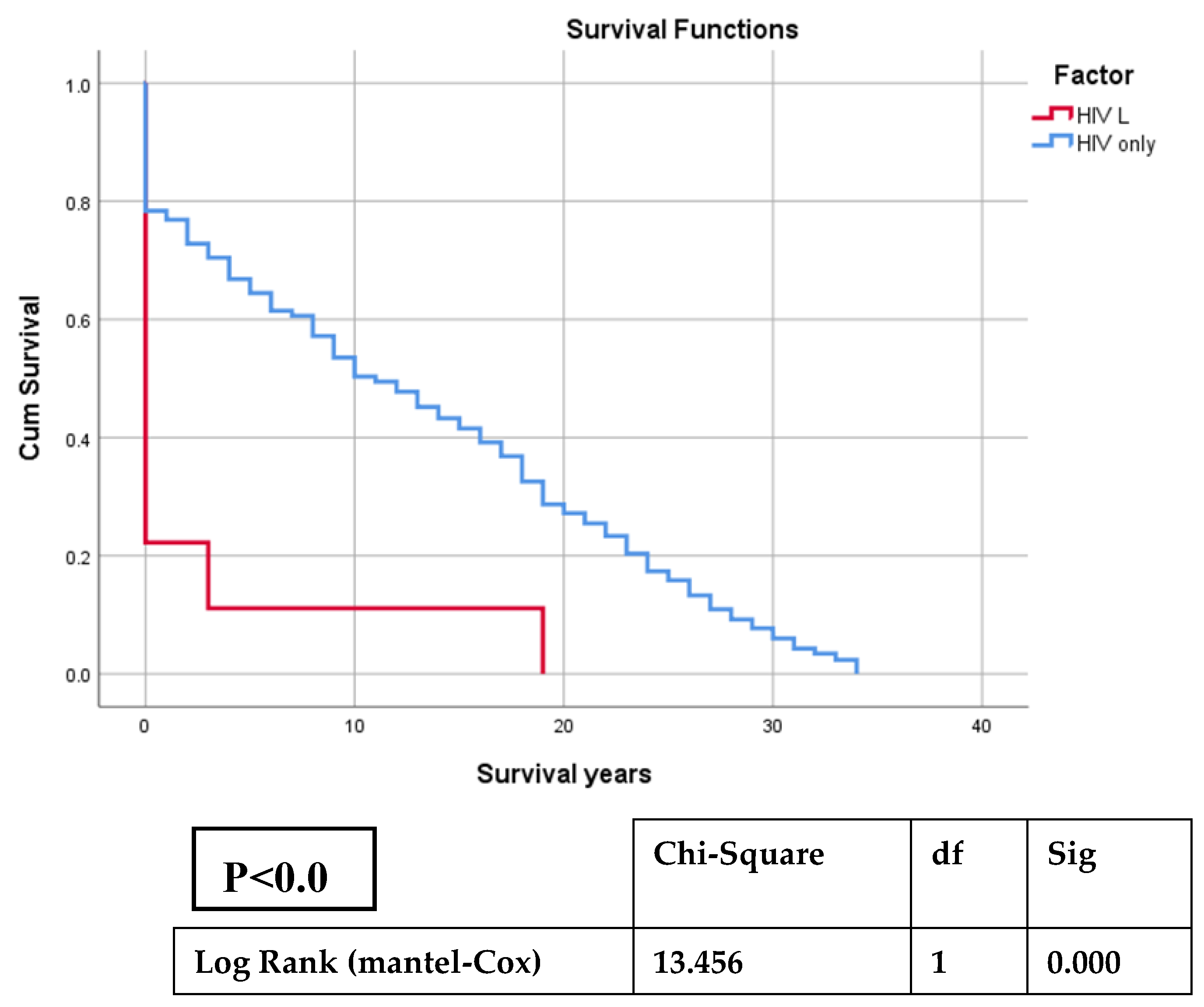

The analysis of K-M curves has identified a Chi-Square value of 13,456 (df=1), and associated p-value (Sig.) <0.001, that are statistically significant for the difference between the survival distributions of the groups, suggesting that the association of lymphoma and HIV patients has been influencing the duration of life expectancy (

Figure 1,

Table A1).

3.2. Characteristics of PLWH Diagnosed with Lymphomas

We have found a number of 9 PLWH diagnosed with lymphoma, specified as 7 NHL, and 2 HL (

Table A2).

3.1.1. Demographic Characteristics

All patients were Caucasian, most of them were male (8/9), living in urban area (5/9), and all but one had completed secondary education. According to the marital status, most were single (6/9) and one case each was divorced, married and widower. The age on HIV diagnostic ranged between 2 and 59 years old, including four patients with pediatric pattern of HIV infection and five sexually transmitted cases. None of the patients was intravenous drugs user. The average age of lymphoma diagnostic was 35±16.18, varied between 18 and 60 years. The diagnostic age of lymphomas was lower on smokers, patients with pediatric pattern of transmission, history of tuberculosis and hepatitis B virus (HBV) co-infection (

Table A3).

3.2.2. HIV history Characteristics

When HIV diagnostic, 7/9 patients were late presenters (AIDS stage) and all of them experienced very low average of nadir of CD4-count of 32.22±20.65, ranging between 4 and 66/mm3. History of tuberculosis were found in 5/9 cases and HBV in 4/9 cases, but no hepatitis C virus (HCV) or syphillis co-infection. All patients have experienced at least one line of ART after HIV diagnostic, but 3 of them have been multiple experienced.

3.2.3. Lymphomas Features on HIV Infected Host

Lymphoma was an indicator of immunossupression and have been pointed to HIV testing in four of nine cases, all of them being „very late presenters” (P4, P6, P7, P9). The average CD4 count when lymphomas diagnostic was 95,22±50.61, ranging from 15 to 172/mm3. A small lymphocytic lymphoma was explained as an immune reconstruction syndrome after diagnostic and treatment of HIV-Tuberculosis co-infection (P3). In the other cases, the interval after HIV diagnostic to lymphoma occurance ranged between 2 and 24 years.

The diagnosis of lymphoma was confirmed in all cases by anatomopathological examinations of biopsy specimens of lymph node (4/9), skin or mucosa (4/9), and bone marrow (1/9). Immunohistochemistry was unavailable in one single case (P5).

The histological subtipe of NHL were mostly DLBCL (44.44%), while the Small lymphocytic lymphoma, BL and PBL, were found as one case for each. HL represented 22.22%. The staging of lymphomas revealed invasion of extralymphatic tissues in 6/9 patients, which means stage IV according to Ann Arbor staging. The signs of B category (Gobbi, 1985) were present in 4/9 patients: fever (P4, P5, P8, P9), over 10% of weight lost in the last 6 months (P4) and night sweats (P4).

Chemotherapy was provided to 5 patients (P1, P2, P6, P7, P8) and two of them have been survived (P6, P8). Other 3 patients (P1, P2, P6) were nonresponders to chemotherapy and the lymphomas have been extending to the fatal outcome (

Table A2).

Among our patients, five received chemotherapy (P1, P2, P6, P7, P8). P1 and P6 received Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, Prednisone treatment (CHOP), but P6 also received immunotherapy with Rituximab (R). After one year, they are the only two survivors, one case each of NHL and HL. The inability to administer chemotherapy in some cases was due to late presentation and the presence of active infections, such as COVID-19 (P9), as well as delays in obtaining immunohistochemical results.

A particular case was a female (P7) experienced of two types of cancer . The first one was an oral PBL as indicator of HIV testing and the second was a tumour of the left breast that was detected three months later, during the chemotherapy for lymphoma. The breast carcinoma diagnostic was supported by the anathomopathological exam, but the result was available after the patient was died.

4. Discussion

4.1. Pathophysiological Mechanisms of HIV-Associated Lymphoma

HIV-positive people have a higher risk of developing various diseases, including cancer. Progressive immunosuppression secondary to HIV infection is a risk factor for the development of a variety of malignancies [

26,

27].

The development of HIV/AIDS-associated lymphoma consists of a combination of factors, including immune system dysregulation, genetic mutations, viral infections, and chronic activation of B-lymphocytes. These lymphomas predominantly arise from B-cells and are characterized by clonal immunoglobulin rearrangements [

28].

The HIV related chronic inflammation is associated with disruption of cytokines and chemokines that play a role at the tumor microenvironment [

29].

The mechanisms of enhanced death in HIV-infected cells than uninfected ones are increased apoptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis. The HIV-related CD4 T-cell death involves about 95% a caspase-1-mediated pyroptosis pattern, while the proportion of cell apoptosis is less than 5% [

30]. Significant differences of microenvironments were found between sporadic DLBCL and HIV-associated DLBCL that is highly angiogenic with a higher density of micro-vessels [

31]. The type of lymphoma is significantly influenced by the degree of CD4 cell depletion and immune dysfunction [

32]. In patients with severe immunosuppression, there is an increased incidence of lymphoma subtypes such as DLBCL, PEL, or immunoblastic PBL, while patients with high CD4 counts are more likely to develop centroblastic DLBCL and BL [

17].

However, HIV could influence oncogenesis independent of immune suppression, by using a direct pro-oncogenic mechanism [

33]. The dysregulation of the cell cycle influences the non-immune microenvironment by increasing in the extracellular matrix, profibrogenic factors and aberrant lymph angiogenesis [

34].

Co-infections with HTLV-1, EBV, and HHV8 are oncogenic viruses that increase the susceptibility to HIV/AIDS-associated lymphomas [

28,

35,

36]. An elevated risk of lymphomas was reported in HIV-positive individuals with HBV and HCV co-infections [

37].

Chronic activation of B-lymphocyte during HIV immune dysfunction is following by hypergammaglobulinemia, impaired humoral immunity, and germinal center hyperplasia, which can ultimately result in lymphoma development [

38].

4.2. Epidemiology of Co-Morbid HIV and Lymphomas

The updates on HIV associated lymphoma during the antiretroviral therapy from US evidenced the increasing incidence trends, with the most common histologic type of the diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), followed by the Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), concordant with the results of our study [

39].

Some prospective cohort studies on different populations, conducted in Switzerland, US, or China, have reported the incidence of lymphomas in PLWH between 2% and 2,14% [

40,

41,

42]. We found an incidence of 1,89%, with a slightly difference explained possible by the younger age of HIV patients of our study.

Generally, the malignant neoplasms, including lymphomas, are more common in men [

43]. The gender differences in lymphoma incidence are still unclear, but there are considered extrinsic factors as exposure to environmental carcinogens, and intrinsic factors, comprising in different immune and hormonal prophyll, body size, and tumor biology in men and women [

44]. Our study confirms the predominance of lymphomas in men, most of them smokers, with sexual transmitted pattern and severe immunosuppression. These demographic factors are commonly observed in other cohorts, and several studies suggest that smoking and advanced immunosuppression may contribute to the higher incidence and poor prognosis of lymphoma in HIV-infected individuals [

39].

The lymphomas could be expected in all ages. Our study found the average age at lymphoma diagnosis 35 years, younger than by the other reports, specifying of 42 years in a Brazilian study or 48 years in a US study or 43,6 years in a Chinese Study [

17,

45,

46].

Studies from Europe and US supported the trend of lymphomas diagnoses in patients with advanced immunosuppression, often as a late-stage complication in individuals with poorly controlled HIV [

45]. Furthermore, all our patients had advanced lymphomas in stage III/IV and severe HIV immunosuppression with CD4 counts <200/mm³.

Mortality hangs on region. Studies in some European countries have identified a lower mortality rate of lymphoma among HIV patients. A French study for 10 years has reported a mortality rate of 8.8%, from a total of 82,000 HIV patients [

47]. Another study conducted in US found significantly higher mortality rate for HIV-associated lymphoma than for other HIV-related diseases [

48]. In Botswana, mortality in HIV HL was noninferior to that of non-HIV HL, due to equal increased access to oncologic care for PLWH and those without HIV [

49].

The mortality rate of PLWH wit lymphoma in our study was 77.7%, notably higher than the mortality rate of 13.65% in HIV-only group, reinforcing the severe impact of lymphoma on survival expectancy of HIV Romanian patients.

4.3. Particularities of Romanian HIV Epidemic and Oncologic risk

Romania is a Central-Eastern European country with a number of 18,359 alive PLWH reported by the Ministry of Health on June, 2024. More than a half of cases are survivors of the „Romanian HIV pediatric cohort”, meaning patients born mainly between 1988 and 1989. Most of them, were HIV infected during the first years of life, by small amount of blood transfusions or inappropriate use of syringes and needles in health care communist poor institutions. Since December 1989, the communist regime was removed, HIV diagnostic tests become available and very soon we found that Romania had 60% of the total pediatric AIDS in Europe [

50].

The particularities of "HIV pediatric cohort" are the homogenous Caucasian race, many cases of long-term survival from the early infancy to the adult present age, pre-dominant F-HIV subtype of the infecting virus, high rate of co-infection with hepatitis B virus, multiple antiretroviral drugs experience. Growing-up with HIV is a complex individual burden, involving physical, functional, psychological and socio-behavioral development, going to high risk of increasing co-morbidities. Three subjects with NHL (P1, P4, P5) and one HL (P8) from our cases-series belonged to the pediatric HIV cohort. They were diagnosed with HIV on the age of 10 years, 19 years, 2 years, 14 years, respectively, and developed lymphoma diagnosed on the age of 18 years, 21 years, 26 years and 29 years, respectively. Beside the pediatric patients born in the ninety, the „adult” HIV epidemic, has progressed by increasing sexually transmission or by intravenous drugs users [

51].

4.4. Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome

The Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome (IRIS) is an over-inflammatory reaction that occurs when the immune system is recovering under antiretroviral drugs, mostly in PLWH with low CD4 counts and tuberculosis or cryptococcosis [

52,

53]. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) occurs in two forms: "paradoxical" IRIS refers to the worsening of a previously treated infection after ART is started and "unmasking" IRIS refers to the flare-up of an underlying, previously undiagnosed infection soon after antiretroviral therapy is started [

54].

The "unmasking" IRIS was applied to one of our case-series (P3). A study involving a cohort of 482 patients with HIV/AIDS-associated lymphoma from 1996 to 2011 found that 48 patients (10%) met the criteria for unmasking lymphoma. Among these cases 10 (21%) were classified as HL, 19 (40%) as DLBCL, 4 (8%) as BL, 9 (19%) as PCNSL, and 6 (12%) as other NHL [

55].

4.5. Real-Life Treatment, Available Options, and Future Perspectives

The treatment of HIV infection and lymphoma requires an integrated approach, considering the interaction between these two conditions. ARV is essential for suppression of HIV replication and recover the immune function, while chemotherapy is the usual treatment of lymphoma with immunosuppressive adverse event [

35].

Since 2018, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines included a dedication section for the treatment of HIV-associated B-cell lymphomas [

19,

56].

The current standard practice is to continue or to initiate antiretrovirals during chemotherapy [

51]. PLWH who have well-controlled onco-hematologic disease have a life expectancy comparable to the general population. This group remains underrepresented in clinical trials, as seropositive status continues to be an exclusion criterion for most lymphoma trials [

57,

58].

Therapeutic protocols such as R-CHOP (Rituximab, Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine and Prednisone), R-CDE (Rituximab, Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Etoposide), R-EPOCH, and (DA)-EPOCH-R (dose-adjusted Etoposide, Prednisone, Vincristine, Doxorubicin and Cyclophosphamide based on CD4 count plus Rituximab), achieved a complete response rate of 69%–91%, with a 2-year survival rate of 62%–75%, and low mortality from infectious causes. The addition of immunotherapy proved beneficial for patients with HIV-associated lymphomas [

59].

Autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) is provided equally for both HIV-negative and HIV-positive lymphoma patients from some European countries [

60]. In recent years, this therapeutic option has also been used in Romania for few patients with HIV and lymphoma. Notably, some studies have reported a surprisingly low relapse rate in PLWH who underwent ASCT for HIV-associated lymphoma [

60]. These findings suggest that highly myelotoxic chemotherapy may deplete the HIV reservoir, promoting immune recovery, and that restoring an efficient immune system could be more beneficial for lymphomas arising in the context of immune deficiency than for those in immunocompetent individuals [

61].

The first two cases of HIV-associated DLBCL treated with the chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (CAR-T) axicabtagene ciloleucel were reported in 2019. This report demonstrated that CAR-T cells can be successfully produced in HIV patients undergoing ART, even with CD4 counts as low as 52 cells/mm³ [

62]. In Romania, CAR T-cell therapy has been available since 2022 for adult patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and for acute lymphoblastic leukemia who have failed at least two lines of systemic chemotherapy. However, this revolutionary treatment has not yet been administered to HIV positive patients in our country.

Limits of the Study

The first limit of our study is the retrospective design and inconsequent available data. The evaluation and treatment decisions were not unitary, because the guidelines and protocols for both HIV and lymphomas have been changed, considering the longtime of the study. The small number of lymphomas in PLWH cases has not support a consistent statistical analyze. Immunohistochemistry and other investigations for the cancer diagnostic, are missing, because there are not included by the health insurance and the patients couldn’t afford them. Serological evaluation of EBV, HHV-8, with oncogenic potential, was not available.

5. Conclusions

Lymphoma is a rare co-morbidity in PLWH from the South-East of Romania, but has a serious impact on life-expectancy, due to the high mortality rate. The median age of lymphoma in PLWH was 35, ranging from 18 to 59 years old. The most frequent subtype of lymphoma was DLBCL. A low CD4 count is associated with more aggressive forms of lymphomas low survival on one year follow-up. Smoking, HBV co-infection and long-term living with HIV of patients from „the pediatric cohort” are predictors for the younger age of lymphomas diagnostic. Most of lymphomas occurred in HIV males. Delay of the onco-hematological diagnostic, the limited access to screening and treatment, the poor education for earlier medical visit are the main difficulties in the management of lymphomas in PLWH, requiring sustained heath strategies dedicated to this special population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A. and M-D.P-C.; methodology, E.N., A-A.A..; software, A-A.A.; validation, I.C., S.F. and E.N.; formal analysis, M-D.P-C..; investigation, M-D.P-C., I.C., S.F., A-A.A., E.N., M.A.; data curation, S.F.; writing—original draft preparation, M-D.P-C., I.C., S.F., E.N.; writing—review and editing, A-A.A., M.A.; visualization, I.C.; supervision, A,M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declara-341 tion of Helsinki, for studies involving humans, and approved by the Institutional Board of Clinic Hospital for Infectious Diseases Galati No.3/3 date 23.03.2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data regarding the findings are available within the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The paper was academically supported by “Dunărea de Jos” University, Galați, Romania.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

Abbreviations:

ABVD = Doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine

ART = antiretroviral treatment

BL = Burkitt Lymphoma

BM = bone marrow

CAR-T = chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy

CHOP = Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone

CVP = Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine.

dg = diagnostic

DLBCL = Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

EBV = Epstein Barr Virus

Education# = years of formal education

EPOCH = Etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin

GCB = germinal center B-cell

HBV = hepatitis B virus

HCV = hepatitis C virus

HHV8 = Human Herpesvirus-8

HL = Hodgkin Lymphoma

HPE = histology examination

HTLV1 = Human T-Lymphotropic Virus Type 1

IHC = immunohistochemistry

II = integrase inhibitor

L = Lymphoma

LN = lymph nodes

MCHL = Mixed Cellularity Hodgkin Lymphoma

MODS = Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome

NHL = Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

NNRTI = non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor

NRTIs = reverse transcriptase inhibitors

NSCHL = Nodular sclerosis classic Hodgkin lymphoma

PBL = Plasmablastic lymphoma

PCNSL = primary central nervous system lymphoma

PI = protease inhibitor

R-CHOP = Rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone

SLL = Small lymphocytic lymphoma

Survive (a) = survival years after the diagnostic of Lymphoma

Survive (b) = Survival years after HIV diagnostic

UGIB = Upper gastrointestinal bleeding

US = United States

Appendix A

Table A1.

Means and Medians for Survival Time.

Table A1.

Means and Medians for Survival Time.

| Factor |

Meana

|

Median |

| Estimate |

Std. Error |

95% Confidence Interval |

Estimate |

Std. Error |

95% Confidence Interval |

| Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

| HIV L |

2.444 |

2.096 |

.000 |

6.552 |

.000 |

. |

. |

. |

| HIV only |

12.640 |

.495 |

11.670 |

13.611 |

11.000 |

.997 |

9.045 |

12.955 |

| Overall |

12.447 |

.491 |

11.484 |

13.411 |

10.000 |

.974 |

8.091 |

11.909 |

| a. Estimation is limited to the largest survival time if it is censored. |

Table A2.

Individual Characteristics of PLWH diagnosed with Lymphomas.

Table A2.

Individual Characteristics of PLWH diagnosed with Lymphomas.

| NHL |

HL |

| |

P1 |

P2 |

P3 |

P4 |

P5 |

P6 |

P7 |

P8 |

P9 |

| Gender |

Male |

Male |

Male |

Male |

Male |

Male |

Female |

Male |

Male |

| Age HIV dg |

10 |

48 |

20 |

21 |

2 |

59 |

35 |

16 |

57 |

| Age L dg |

18 |

50 |

21 |

21 |

26 |

59 |

35 |

28 |

57 |

| Living area |

Urban |

Urban |

Urban |

Rural |

Rural |

Urban |

Urban |

Rural |

Rural |

| Education* |

8 |

12+ |

4 |

8 |

8 |

12 |

12 |

12 |

8 |

| Marital status |

Single |

Married |

Single |

Single |

Single |

Divorced |

Single |

Single |

Widower |

| Smoking |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

| HIV related data |

| Year HIV dg |

1999 |

2006 |

2009 |

2013 |

1992 |

2020 |

2021 |

2002 |

2021 |

| Transmission pattern |

Pediatric |

Sexual |

Pediatric |

Sexual |

Pediatric |

Sexual |

Sexual |

Pediatric |

Sexual |

| HIV staging |

B2 |

C3 |

C3 |

C3 |

B2 |

C3 |

C3 |

B3 |

C3 |

| AIDS |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Nadir CD4 |

47 |

28 |

4 |

15 |

20 |

66 |

58 |

31 |

21 |

| No. ART lines |

5 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

6 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

| TB history |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

| Syphillis history |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| HBV-coinfection |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

| HCV |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Lymphoma related data |

| Year L dg |

2008 |

2008 |

2010 |

2013 |

2017 |

2020 |

2021 |

2017 |

2021 |

| CD4 on L dg |

165 |

172 |

74 |

15 |

85 |

66 |

58 |

110 |

112 |

| B symptoms |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

| L staging |

III |

IV |

IV |

IV |

III |

IV |

IV |

IV |

III |

| Biopsy-HPE |

LN |

Skin |

Skin |

LN |

LN |

Parotid |

Maxillary |

BM |

LN |

| IHC |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| L subtype |

DLBCL |

SLL |

BL |

DLBCL |

DLBCL |

DLBCL GCB |

PBL |

NSCHL |

MCHL |

| Major Complications |

Miastenia gravis |

Nephrolithiasis Seizures

Retinal detachment in the right eye |

Liver failure UGIB |

Tetra-paresis

UGIB |

Liver failure

UGIB |

|

Sepsis

Left breast carcinoma |

Sepsis

|

MSOF

|

| COVID-19 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

No |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

| Other Comorbidities |

|

Plasmocitoma

Diabetes |

Mental deficiency |

|

|

|

Psoriazis |

Warts |

HBP

Pleuresy |

| Oncology treatment |

5 CHOP |

6 CVP |

No |

No |

No |

8 RCHOP |

3 EPOCH |

6 ABVD |

No |

| Survive (a) |

<1 |

<1 |

<1 |

<1 |

<1 |

>2 |

<1 |

>6 |

<1 |

| Survive (b) |

9 |

2 |

1 |

<1 |

24 |

>2 |

<1 |

>21 |

<1 |

Table A3.

Factors influencing the age of lymphomas diagnostic in PLWH (Two-Sample t-tests).

Table A3.

Factors influencing the age of lymphomas diagnostic in PLWH (Two-Sample t-tests).

| N=9 |

n |

Average age ±SD |

CI- 0.95 |

p |

| Lymphoma’s Subtype |

NHL |

7 |

32.85±15.97 |

-209.21; 189.92 |

0.649 |

| HL |

2 |

42.5±20.50 |

| Smoking |

Yes |

6 |

41.33±16.25 |

1.21; 36.78 |

0.039 |

| No |

3 |

22.33±5.13 |

| Pattern of HIV transmission |

Pediatric |

4 |

23.25±4.57 |

-42.14; -0.15 |

0.048 |

| Sexual |

5 |

44.4±16.11 |

| Tuberculosis history |

Yes |

5 |

28.6±12.60 |

-41.97; 13.17 |

0.237 |

| No |

4 |

43±18.25 |

| HBV-coinfection |

Yes |

4 |

23.25±4.57 |

-42.14; -0.15 |

0.048 |

| No |

5 |

44.4±16.11 |

References

- WHO. The urgency of now: AIDS at a crossroads. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2024. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2024-unaids-global-aids-update_en.pdf. Accessed [10.10.2024].

- Funderburg, N. T.; Huang, S. S. Y.; Cohen, C.; Ailstock, K.; Cummings, M.; Lee, J. C.; Ng, B.; White, K.; Wallin, J. J.; Downie, B.; et al. Changes to inflammatory markers during 5 years of viral suppression and during viral blips in people with HIV initiating different integrase inhibitor based regimens. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1488799. [CrossRef]

- Poizot-Martin, I.; Lions, C.; Allavena, C.; Huleux, T.; Bani-Sadr, F.; Cheret, A.; Rey, D.; Duvivier, C.; Jacomet, C.; Ferry, T.; Cabie, A. Spectrum and Incidence Trends of AIDS-and Non–AIDS-Defining Cancers between 2010 and 2015 in the French Dat'AIDS Cohort. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 2021, 30(3), 554-563. [CrossRef]

- Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Laversanne M, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Soerjomataram I, Bray F (2024). Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer. Available from: https://gco.iarc.who.int/today. Accessed [10.10.2024].

- Kimani, S.M., Painschab M.S., Horner MJ, Muchengeti M, Fedoriw Y, Shiels MS, Gopal S. Epidemiology of haematological malignancies in people living with HIV. The Lancet HIV, 2020, 7, e641-51.

- Wang, C.; Xiao, Q.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y. HIV associated lymphoma: latest updates from 2023 ASH annual meeting. Exp Hematol Oncol 2024, 13, 65. PMID: 38970132; PMCID: PMC11225138. [CrossRef]

- Panel on Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Available at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adult_oi.pdf. Accessed 29.09.2024.

- Horberg, M.; Thompson, M.; Agwu, A.; Colasanti, J.; Haddad, M.; Jain, M.; McComsey, G.; Radix, A.; Rakhmanina, N.; Short, W.R.; Singh, T. Primary Care Guidance for Providers of Care for Persons With Human Immunodeficiency Virus: 2024 Update by the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2024, ciae479. doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciae479.

- Re, A.; Cattaneo, C.; Rossi, G. HIV and lymphoma: from epidemiology to clinical management. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2019, 11, e2019004. [CrossRef]

- Berhan, A.; Bayleyegn, B.; Getaneh, Z. HIV/AIDS Associated Lymphoma: Review. Blood and Lymphatic Cancer: Targets and Therapy 2022, 12, 31-45. [CrossRef]

- Hleyhel, M.; Bouvier, A.M.; Belot, A.; Tattevin, P.; Pacanowski, J.; Genet, P.; De Castro, N.; Berger, J.-L.; Dupont, C. et al. Risk of Non-AIDS-Defining Cancers among HIV-1-Infected Individuals in France between 1997 and 2009: Results from a French Cohort. AIDS 2014, 28, 2109–2118. [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, N.; Abayomi, A.; Locketz, C.; Musaigwa, F.; Greiwal, R. Incidence of Hodgkin lymphoma in HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients at a tertiary hospital in South Africa (2005 - 2016) and comparison with other African countries. S Afr Med J 2018, 108, 563-567. [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71, 209-249. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Pang, W.S.; Lok, V.; Zhang, L.; Lucero-Prisno III, D.E.; Xu, W.; Zheng, Z.J.; Elcarte, E.; Withers, M.; Wong, M.C.S. Incidence, mortality, risk factors, and trends for Hodgkin lymphoma: a global data analysis. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2022, 15, 57. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhang, X.; Tao, H.; Jia, Y. The prognostic value of Epstein−Barr virus infection in Hodgkin lymphoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Oncology 2022, 12, 1034398; [CrossRef]

- Taj, T.; Poulsen, A.H.; Ketzel, M.; Geels, C.; Brandt, J.; Christensen, J.H.; Hvidtfeldt, U.A.; Sørensen, M.; Raaschou-Nielsen, O. Long-term residential exposure to air pollution and Hodgkin lymphoma risk among adults in Denmark: a population-based case–control study. Cancer Causes Control 2021, 32, 935–42. https:// doi. org/ 10. 1007/ s10552-021-01446-w.

- Hübel, K.; Bower, M.; Aurer, I.; Bastos-Oreiro, M.; Besson, C.; Brunnberg, U.; Cattaneo, C.; Collins, S.; Cwynarski, K.; Pria, A.D.; Hentrich, M. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated Lymphomas: EHA–ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. HemaSphere 2024, 8, e150. [CrossRef]

- Castelli, R.; Schiavon, R.; Preti, C.; Ferraris, L. HIV-Related Lymphoproliferative Diseases in the Era of Combination Antiretroviral Therapy. Cardiovascular & Haematological Disorders-Drug Targets 2020, 20, 175-180. [CrossRef]

- Zelenetz, A.D.; Gordon, L.I.; Abramson, J.S.; Advani, R.H.; Andreadis, B.; Bartlett, N.L.; Budde, L.E.; Caimi, P.F.; Chang, J.E.; Christian, B.; DeVos, S. NCCN Guidelines® insights: B-cell lymphomas, version 6.2023: featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2023, 21, 1118-1131. [CrossRef]

- Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Parkin, D.M.; Pineros, M.; Znaor, A.; Bray, F. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: an overview. International Journal of Cancer 2021,149, 778-789. https://doi:10.1002/ijc.3358811.

- Singh, D.; Vacarella, S.; Gini, A.; Silva, N.D.P.; Steliarova-Foucher, E.; Bray, F. Global patterns of Hodgkin lymphoma incidence and mortality in 2020 and a prediction of the future burden in 2040. International Journal of Cancer 2022, 150, 1941-1947. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision. icd.who.int/browse10/2019.

- Centers for Disease Control (1992) 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ 41 (RR-17): 1–19.

- European AIDS Clinical Society Guidelines. Available at: https://www.eacsociety.org/guidelines/guidelines-archive. Accessed: 10.10.2024.

- Hoppe, R.; Advani, R.H.; Ambinder, R.F.; Armand P.; Bello, C.M.; Beniez C.M.; Chen, W.; Cherian, S.; Dabaja, B.; Daly, M.E. et al. Hodgkin Lymphoma Version 4.2024 — October 22, 2024, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology 2024. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/hodgkins.pdf.

- Landgren, O.; Goedert, J.J.; Rabkin, C.S.; Wilson, W.H.; Dunleavy, K.; Kyle, R.A.; Katzmann, J.A.; Rajkumar, S.V.; Engels, E.A. Circulating serum free light chains as predictive markers of AIDS-related lymphoma. Journal of clinical oncology 2010, 28, 773-779. [CrossRef]

- Borgia, M.; Dal Bo, M.; Toffoli, G. Role of virus-related chronic inflammation and mechanisms of cancer immune-suppression in pathogenesis and progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 4387. [CrossRef]

- Carbone, A.; Volpi, C.C.; Gualeni, A.V.; Gloghini, A. Epstein–Barr virus associated lymphomas in people with HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2017, 12, 39–46. [CrossRef]

- Leal, V.N.C; Reis, E.C.; Pontillo, A. Inflammasome in HIV infection: lights and shadows. Molecular immunology 2020, 118, 9-18. [CrossRef]

- Lv, T.; Cao, W.; Li, T. HIV-Related Immune Activation and Inflammation: Current Understanding and Strategies. Journal of immunology research, 2021, 1, 7316456. [CrossRef]

- Rice, A.P. The HIV-1 Tat protein: mechanism of action and target for HIV-1 cure strategies. Curr Pharm Des 2017, 23, 4098–4102. [CrossRef]

- Isaguliants, M.; Bayurova, E.; Avdoshina, D.; Kondrashova, A.; Chiodi, F.; Palefsky, J.M. Oncogenic effects of HIV-1 proteins, mechanisms behind. Cancers 2021, 13, 305. [CrossRef]

- Okuma, A.; Idahor, C. Mechanism of Increased Cancer Risk in HIV, European Journal of Health Sciences 2020, 5, 42-50. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Bieniasz, P.D. HIV-1 Vpr induces cell cycle arrest and enhances viral gene expression by depleting CCDC137, eLife 2020, 9, e55806. [CrossRef]

- Noy, A. Optimizing Treatment of HIV-Associated Lymphoma. Blood 2019, 134, 1385–94. [CrossRef]

- Rana, I.; Dahlberg, S.; Steinmaus, C.; Zhang, L. Benzene exposure and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a systematic review and metaanalysis of human studies. Lancet Planet Health 2021, 5, e633–e643.

- Wang, Q.; De Luca, A.; Smith, C.; Zangerle, R.; Sambatakou, H.; Bonnet, F.; Smit, C.; Schommers, P.; Thornton, A.; Berenguer, J.; Peters, L. Chronic hepatitis B and C virus infection and risk for non-Hodgkin lymphoma in HIV-infected patients: a cohort study. Annals of internal medicine 2017, 166, 9-17.

- Bertuzzi, C.; Sabattini, E.; Bacci, F.; Agostinelli, C.; Ferri, G.G. Two different extranodal lymphomas in an HIV+ patient: a case report and review of the literature. Case Reports in Hematology 2019, 1, 8959145. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xiao, Q.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y. HIV associated lymphoma: latest updates from 2023 ASH annual meeting. Exp Hematol Oncol 2024, 13, 65. PMID: 38970132; PMCID: PMC11225138. [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, S.; Lise, M.; Clifford, G.; Rickenbach, M.; Levi, F.; Maspoli, M.; Bouchardy, C.; Dehler, S.; Jundt, G.; Ess, S.; Bordoni, A. Changing patterns of cancer incidence in the early- and late-HAART periods: the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Br J Cancer 2010, 103, 416–422. [CrossRef]

- Long, J.L.; Engels, E.A.; Moore R.D.; Gebo K.A. Incidence and outcomes of malignancy in the HAART era in an urban cohort of HIV-infected individuals, AIDS 2008, 22, 489–496. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.B.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, W.; Lu, X.; Ming Sun, C.; Liu P.; Hu, Q.H.; Wen, Y. In-hospital Mortality and Causes of Death in People Diagnosed With HIV in a General Hospital in Shenyang, China: A Cross-Sectional Study, Front Public Health 2021, 9, 774614. [CrossRef]

- Radkiewicz, C.; Bruchfeld, J.B.; Weibull, C.E.; Jeppesen, M.L.; Frederiksen, H.; Lambe, M.; Jakobsen, L.; El-Galaly, T.C.; Smedby, K.E.; Wasterlid, T. Sex differences in lymphomaincidence and mortality by subtype: A population-based study, American Journal of Hematology 2022, 98, 23-30. [CrossRef]

- Pfreundschuh, M. Age and sex in non-Hodgkin lymphoma therapy: it's not all created equal, or is it? American Society of Clinical Oncololgy Educational Book 2017, 37, 505-511. [CrossRef]

- Vargas, J.C.; Marques, M.O.; Pereira, J.; Braga, W.M.T.; Hamerschlak, N.; Tabacof, J.; Ferreira, P.R.A.; Colleoni, G.W.B.; Baiocchi, O.C.G. Factors associated with survival in patients with lymphoma and HIV. AIDS 2023, 37, 1217-1226. Epub 2023 Mar 17. PMID: 36939075. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Chen, C.; Zhang, M.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Shi, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, D.; Hu, S. The clinical features and prognosis of 100 AIDS-related lymphoma cases. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 5381. [CrossRef]

- Vandenhende, M.A.; Roussillon, C.; Henard, S.; Morlat, P.; Oksenhendler, E.; Aumaitre, H.; Georget, A.; May, T.; Rosenthal, E.; Salmon, D.; Cacoub, P. Cancer-related causes of death among HIV-infected patients in France in 2010: evolution since 2000. PloS one 2015, 10, e0129550.

- Shiels, M.S.; Pfeiffer R.M.; Gail, M.H.; Hall, H.I.; Li, J.; Chaturvedi, A.K.; Bhatia, K.; Uldrick, T.S.; Yarchoan, R.; Goedert, J.J.; Engels, E.A. Cancer burden in the HIV-infected population in the United States. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2011, 103, 753-62. [CrossRef]

- Moahi, K.; Ralefala, T.; Nkele, I.; Triedman, S.; Sohani, A.; Musimar, Z.; Efstathiou, J.; Armand, P.; Lockman, S.; Dryden-Peterson, S. HIV and Hodgkin Lymphoma Survival: A Prospective Study in Botswana. JCO Glob Oncol 2022, 8, e2100163. https://doi:10.1200/GO.21.00163. PMID: 35025689; PMCID: PMC8769145.

- MINISTRY OF HEALTH. NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES “PROF.DR.MATEI BALŞ” Compartment for Monitoring and Evaluation of HIV/AIDS Infection in Romania. Statistic data 2003, 2012, 2024. Available from: https://www.cnlas.ro/index.php/date-statistice.

- Arbune, M.; Georgescu, C. V.; Voinescu, D. C. AIDS-related lymphoma in a young HIV late presenter patient. Rom J Morphol Embryol 2016, 57 (1), 273-276.

- Oseso, L.N.; Chiao, E.Y.; Ignacio, R.A.B. Evaluating Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation in HIV-Associated Malignancy: Is There Enough Evidence to Inform Clinical Guidelines?, Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2018, 16, 927-932. [CrossRef]

- Sereti, I. Immune Reconstruction Inflammatory Syndrome in HIV Infection: Beyond What Meets The Eye, Topics in Antiviral Medicine 2020, 27, 106–111. PMCID: PMC7162680, PMID: 32224502.

- Vargas, J.C.; Cecyn, K.Z.; Oliveira Marques, M.; Pereira, J.; Tobias Braga, W.M.; Hamerschlak, N.; Tabacof, J.; Liz, C.D.; Abdo, A.; Ferreira, P.R.A.; Colleoni, G.W.B.; Baiocchi, O.C.G. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome-associated lymphoma: A retro-spective Brazilian cohort. EJHaem 2023, 5, 147-152. PMID: 38406522; PMCID: PMC10887249. [CrossRef]

- Gopal, S.; Patel, M. R.; Achenbach, C. J.; Yanik, E. L.; Cole, S. R.; Napravnik, S.; Burkholder, G. A.; Mathews, W. C.; Rodriguez, B.; Deeks, S. G.; et al. Lymphoma immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in the center for AIDS research network of integrated clinical systems cohort. Clin Infect Dis 2014, 59 (2), 279-286. [CrossRef]

- McNally, G.A. HIV and Cancer: An Overview of AIDS-Defining and Non–AIDS-Defining Cancers in Patients With HIV. Clinical journal of oncology nursing 2019, 23, 327-331.

- Uldrick, T.S.; Ison, G.; Rudek, M.A.; Noy, A.; Schwartz, K.; Bruinooge, S.; Schenkel, C.; Miller, B.; Dunleavy, K.; Wang, J.; Zeldis, J.; Little, R.F. Modernizing Clinical Trial Eligibility Criteria: Recommendations of the American Society of Clinical Oncology-Friends of Cancer Research HIV Working Group. J Clin Oncol 2017, 35, 3774-80.

- Vora, K.B.; Ricciuti, B.; Awad, M.M. Exclusion of patients living with HIV from cancer immune checkpoint inhibitor trials, Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 6637. [CrossRef]

- Carbone, A.; Vaccher, E.; Gloghini, A. Hematologic cancers in individuals infected by HIV. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 2022, 139, 995-1012. [CrossRef]

- Re, A.; Cattaneo, C.; Montoto, S. Treatment management of haematological malignancies in people living with HIV. Lancet Haematol 2020, 7, e679-e689. PMID: 32791044. [CrossRef]

- Bertoli, D.; Re, A.; Chiarini, M.; Sottini, A.; Serana, F.; Giustini, V.; Roccaro, A.M.; Cattaneo, C.; Caimi, L.; Rossi, G.; Imberti, L. B-and T-lymphocyte number and function in HIV+/HIV− lymphoma patients treated with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous bone marrow transplantation. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 37995. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, A.; Peeke, S.; Shah, N.; Mustafa, J.; Khatun, F.; Lombardo, A.; Abreu, M.; Elkind, R.; Fehn, K.; De Castro, A.; Wang, Y. Axicabtagene ciloleucel CD19 CAR-T cell therapy results in high rates of systemic and neurologic remissions in ten patients with refractory large B cell lymphoma including two with HIV and viral hepatitis. Journal of hematology & oncology 2020, 13, 1-4. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).