Submitted:

24 December 2024

Posted:

25 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

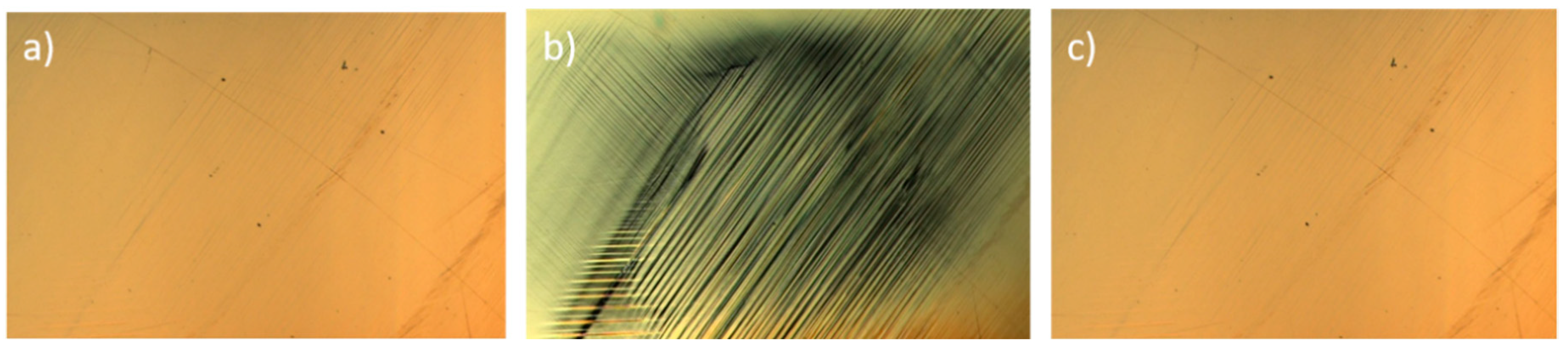

2. Experimental

3. Results

4. Discussion

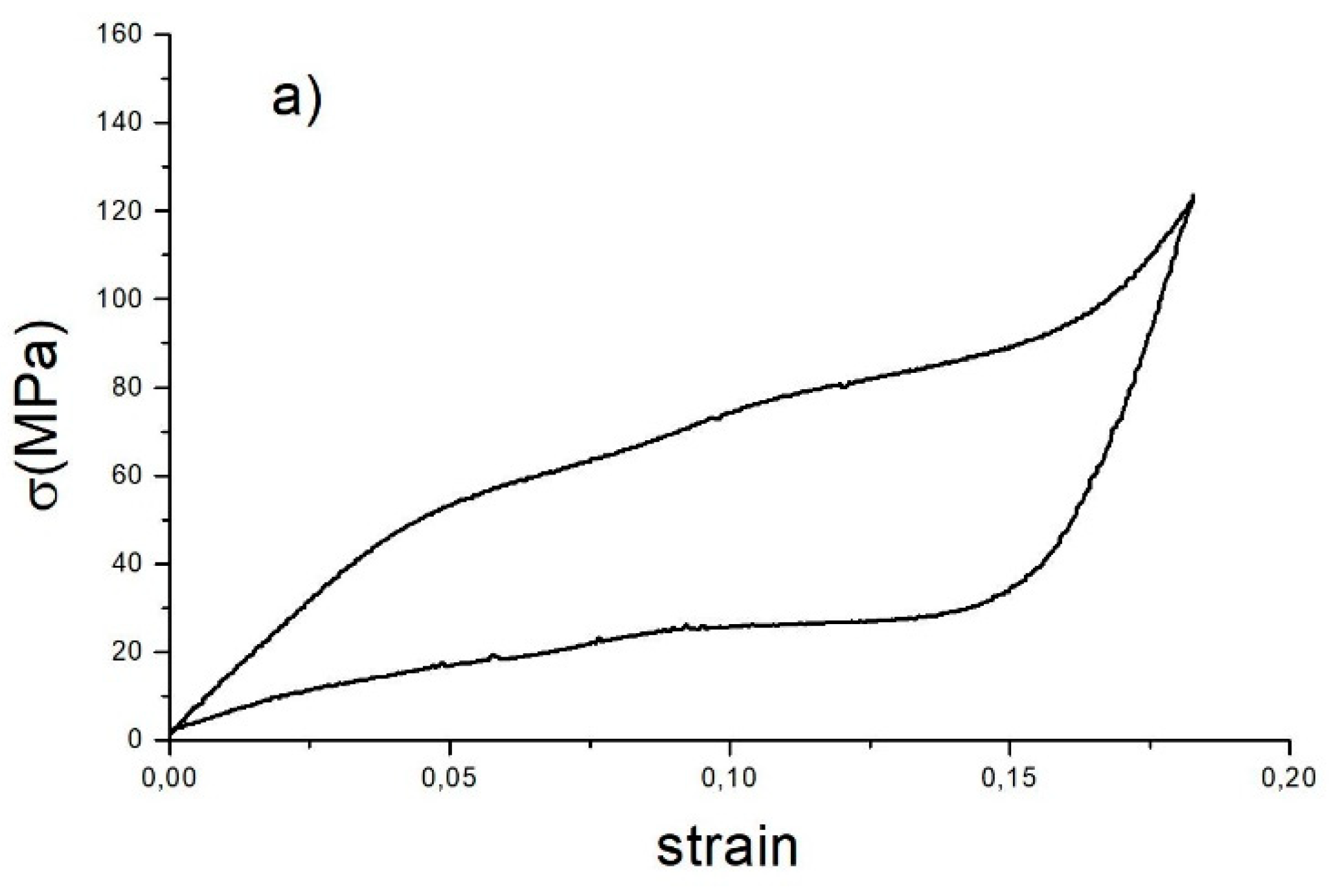

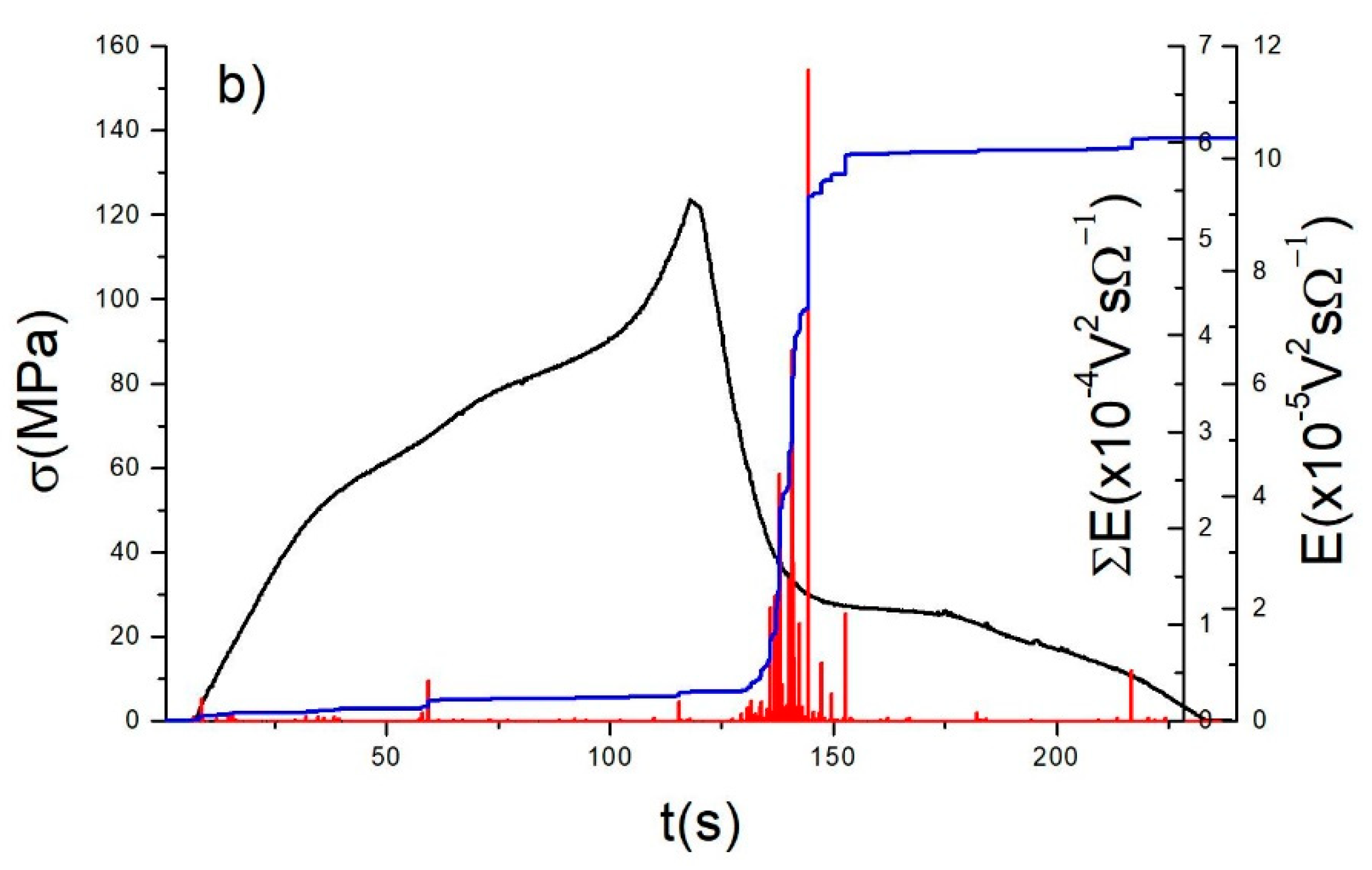

4.1. AE during Loading and Unloading

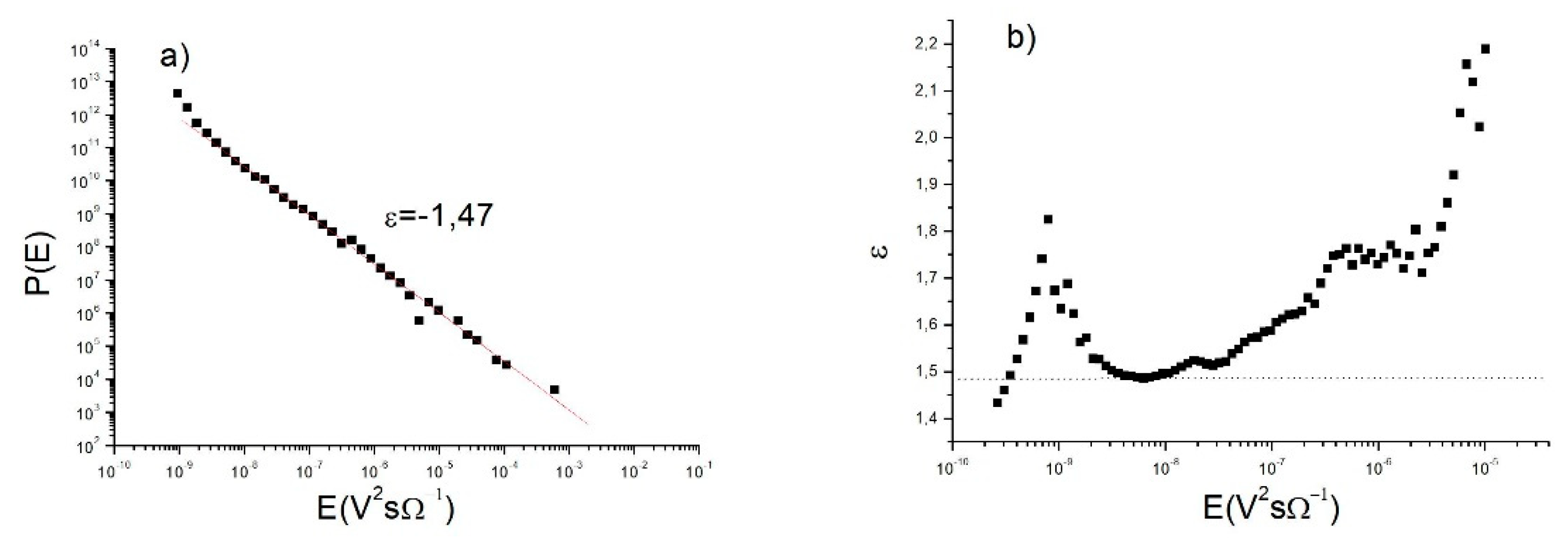

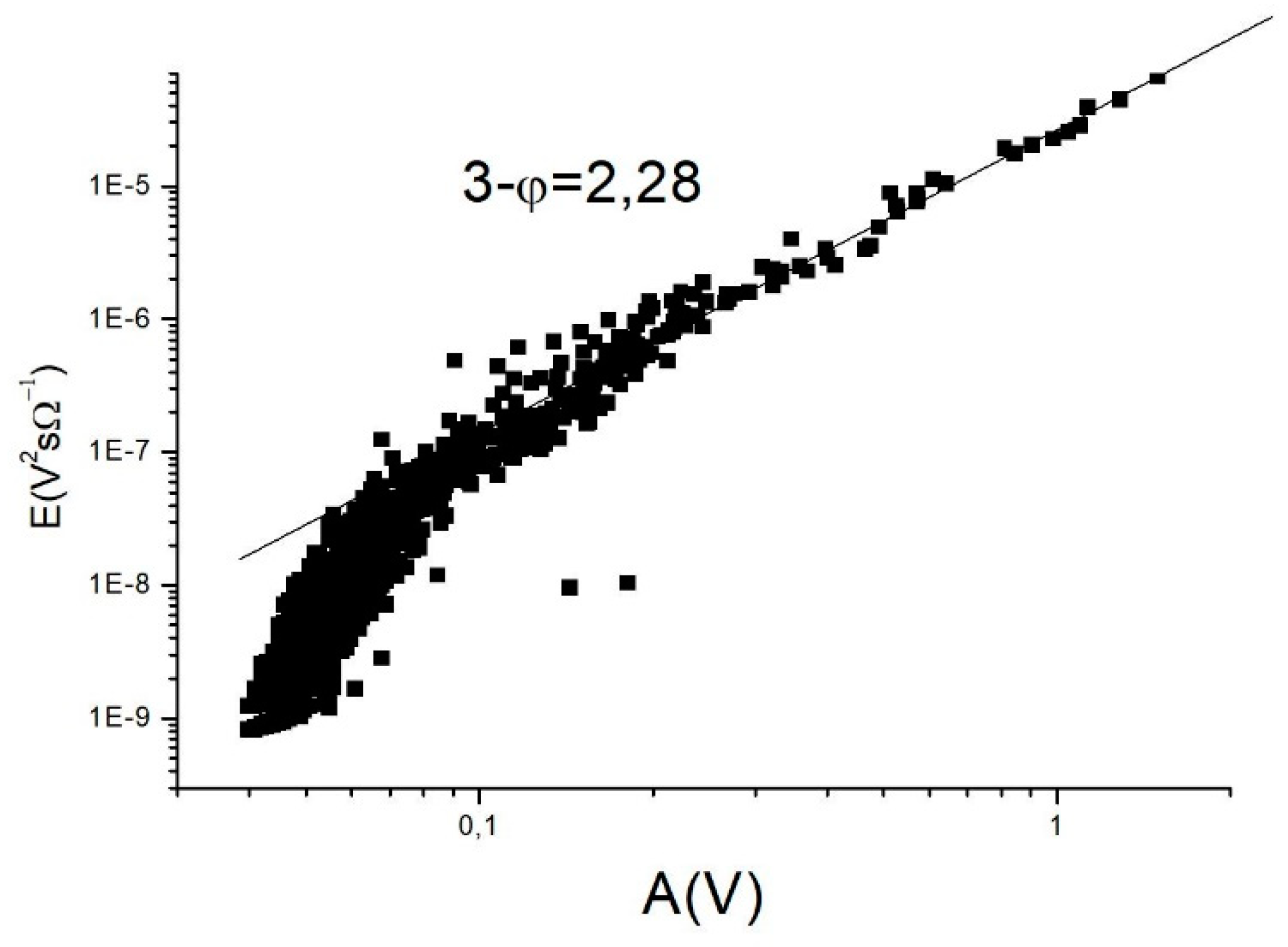

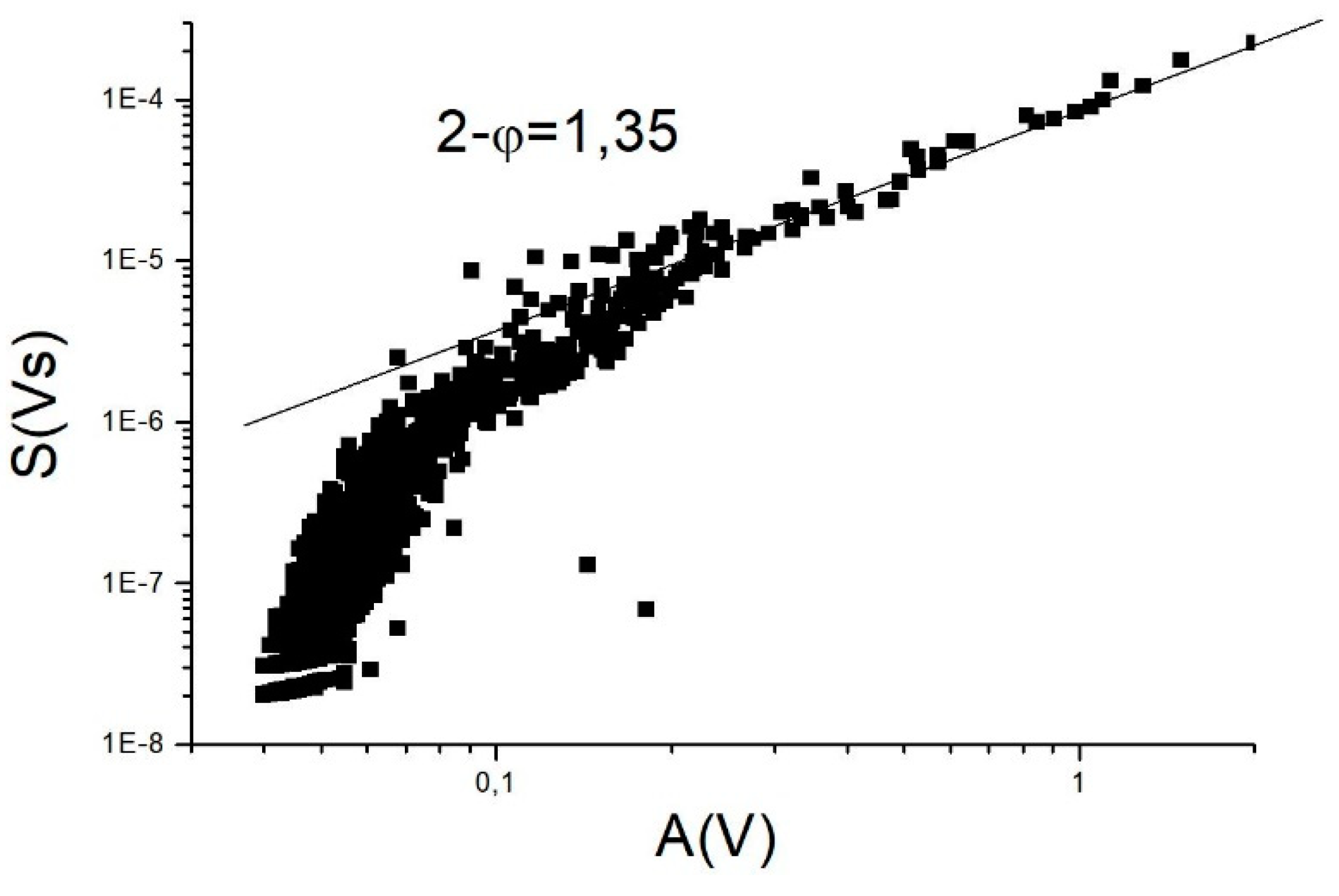

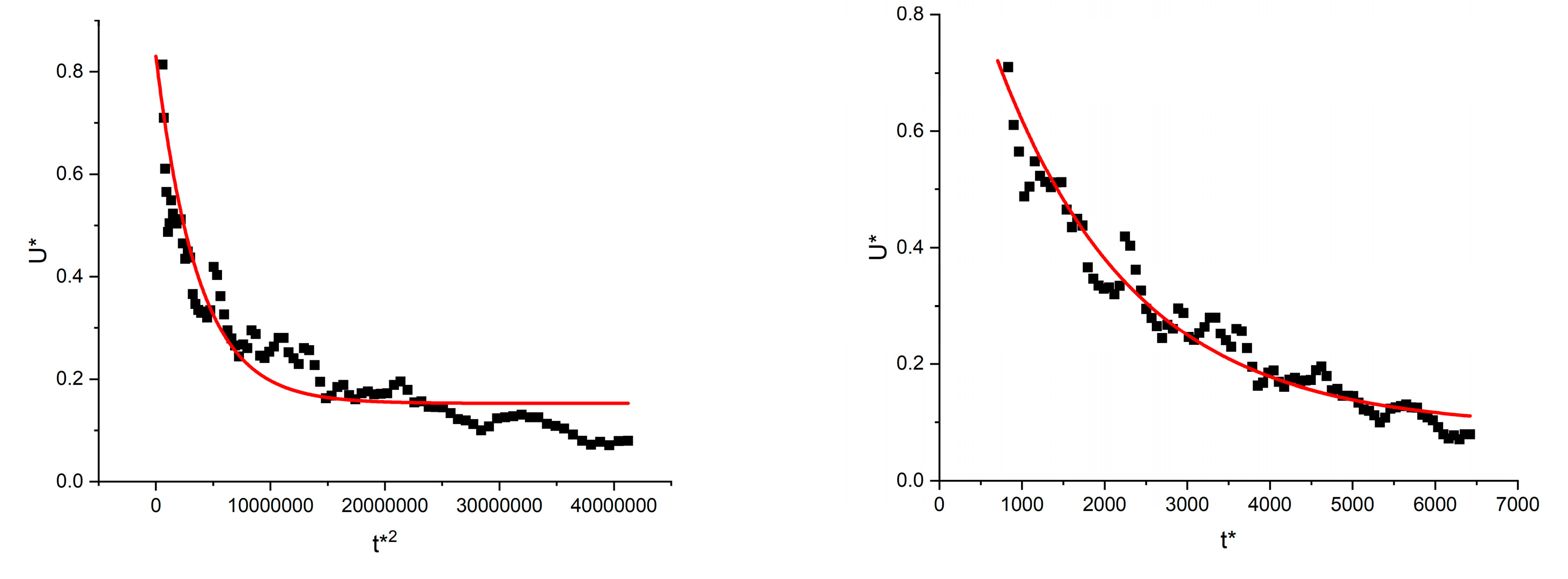

4.2. Power Exponents of the Acoustic Emission Parameters

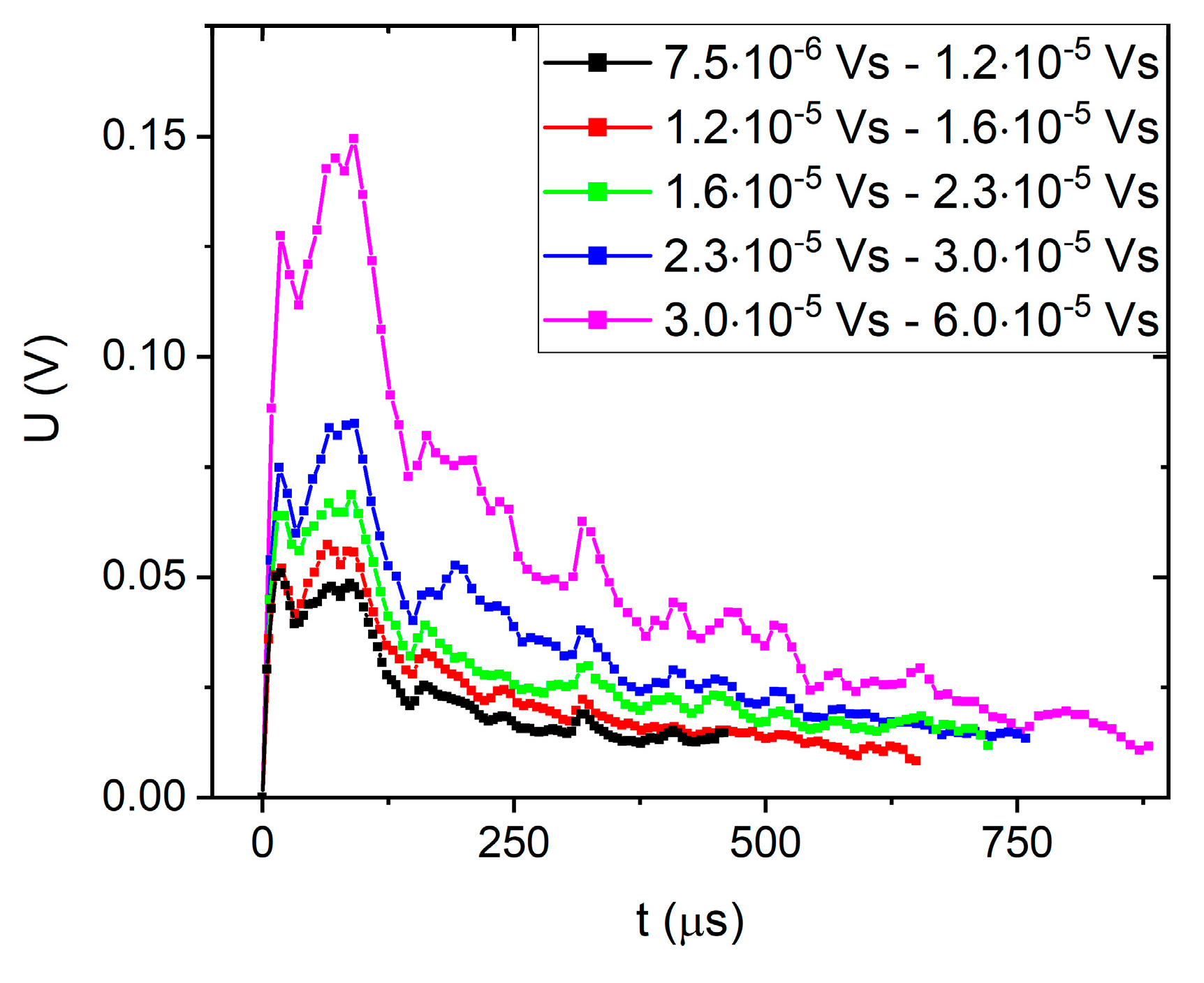

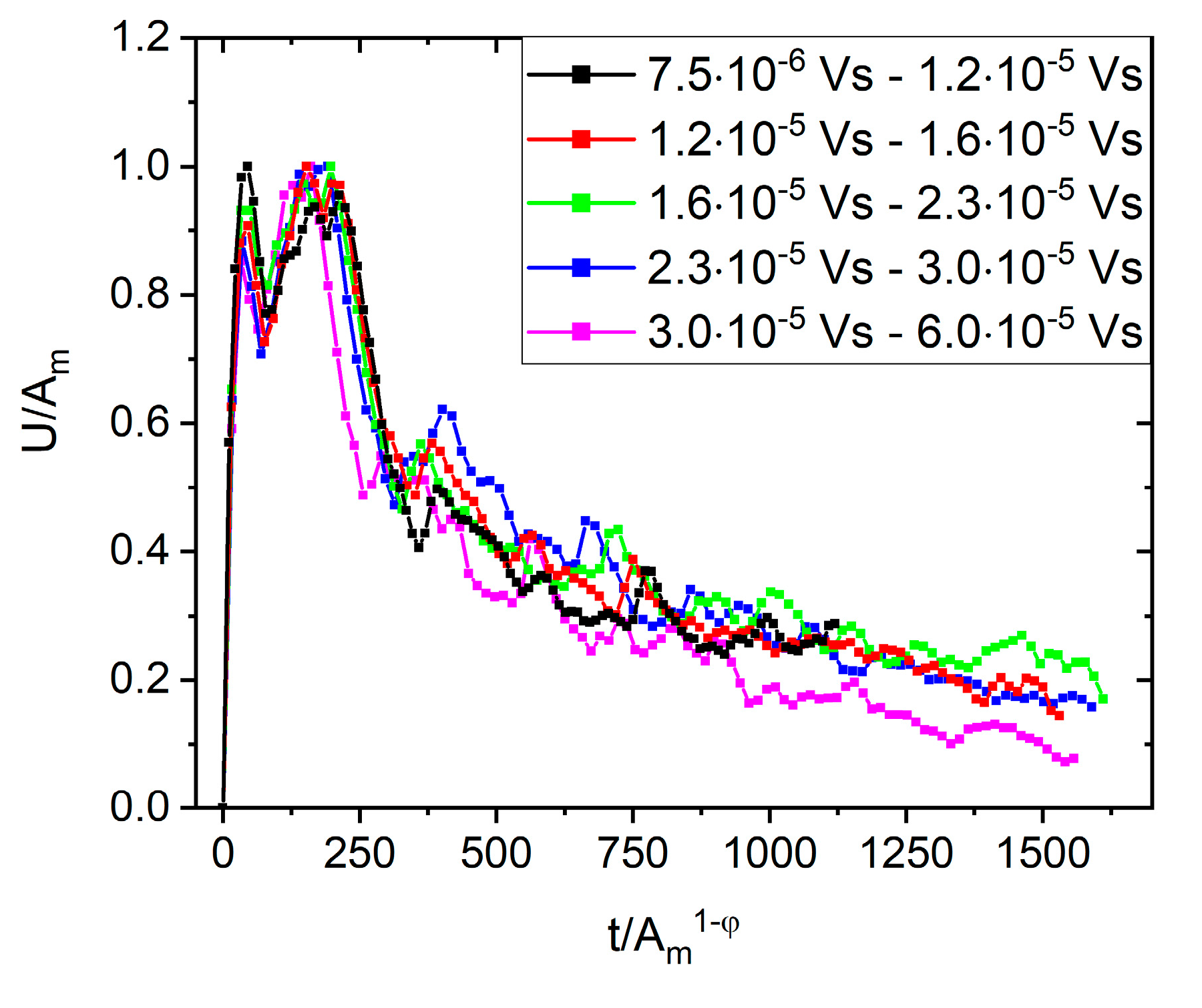

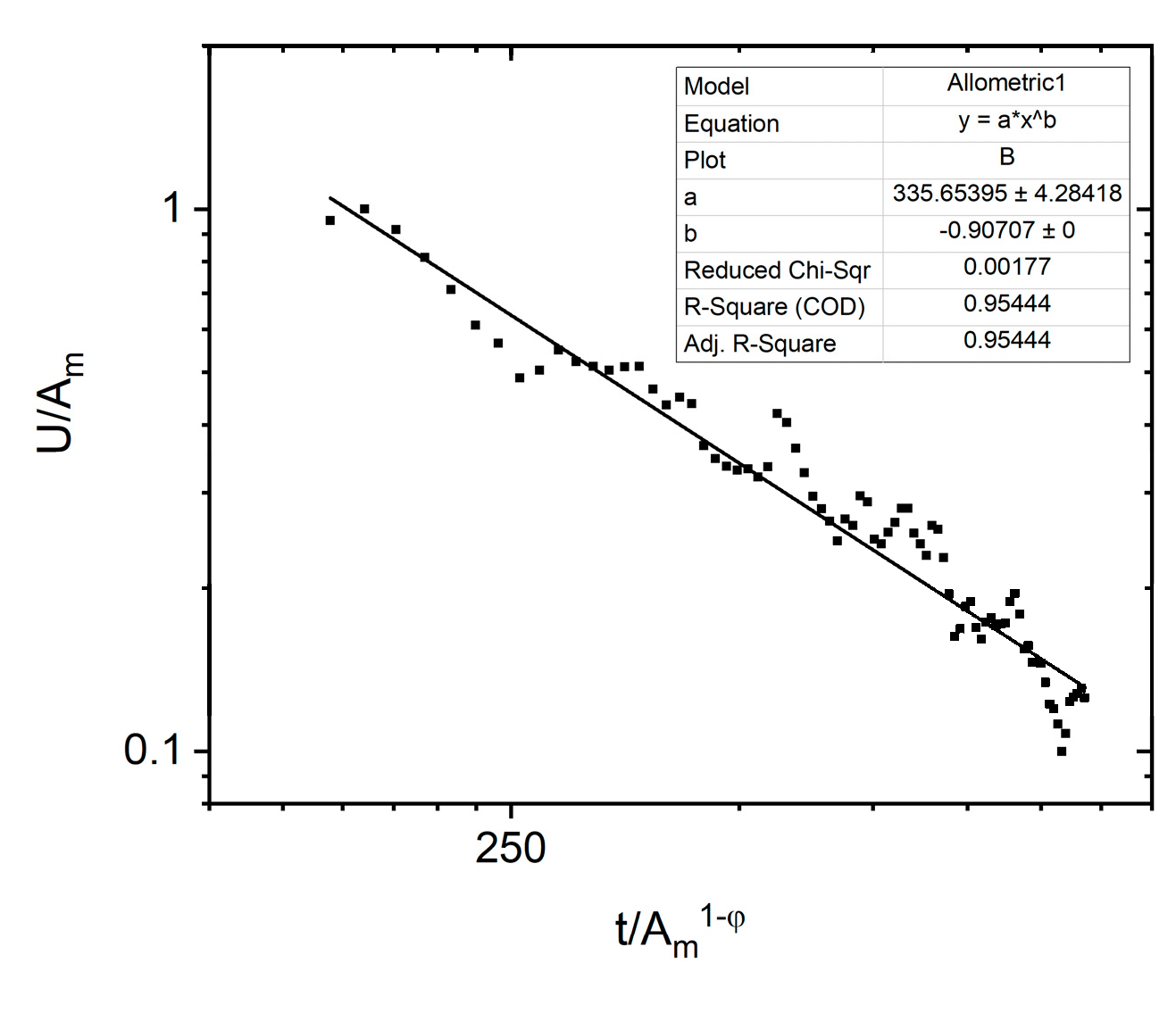

4.3. Normalized Temporal Avalanche Shapes for Fixed Duration and Area

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Otsuka, K.; Wayman, C.M.; Shape memory materials. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK,1999.

- Miura, S.; Maeda, S.; Nakanishi, N. Pseudoelasticity in Au-Cu-Zn thermoelastic martensite, Phil. Mag. 1974, 30:3, 565-581. [CrossRef]

- Murakami, Y.; Nakajima, Y.; Otsuka, K.; Ohba, T,; Matsuo, R.; Ohshima K. Characteristics and mechanism of martensite ageing effect in Au-Cd alloys, Mat. Sci. and Eng. 1997, A237, 87-101. [CrossRef]

- Ren, X,; Otsuka, K.; Origin of rubber-like behaviour in metal alloys, Nature 1997, 389/9, 579-582. [CrossRef]

- Likhachev A.A; Sozinov, A.; Ullakko, K. Different modeling concepts of magnetic shape memory and their comparison with some experimental results obtained in Ni–Mn–Ga, Mat. Sci. and Eng. 2004, A378, 513-518. [CrossRef]

- Beke, D.L.; Daróczi, L.; Shamy, N.M.; Tóth, L.Z.; Bolgár, M.K. On the thermodynamic analysis of martensite stabilization treatments, Acta Mater. 2020, 200, 490-501. [CrossRef]

- Ahlers, M.; Pellegrina J.L. Ageing of martensite: stabilisation and ferroelasticity in Cu-based shape memory alloys, Mater. Sci. Eng. 2003, A356, 298–315. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Kojima, R.; Fujii Y.; Nagasawa A. Reverse transformation behaviour of the stabilized martensite in CuZnAl alloy, Acta Metall. 1989, 37, 163–168. [CrossRef]

- Kustov, S,; Pons J.; Cesari E.; van Humbeeck J. Chemical and mechanical stabilization of martensite, Acta Mater. 2004, 52, 4547–4559. [CrossRef]

- Niendorf, T.; Krooβ, P.; Somsen C.; Eggeler G.; ChumlyakovY.I.; Maier H.J. Martensite aging –avenue to new high temperature shape memory alloys, Acta Mater. 2015, 89, 298–304. [CrossRef]

- Panchenko, E.; Timofeeva, E.; Eftifeeva, A,; Osipovich, S.; Surikov, N.; Chumlyakov, Y.; Gerstein, G.; Maier, H.J. Giant rubber-like behavior induced by martensite aging in Ni51Fe18Ga27Co4 single crystals. Scripta Materialia 2019, 162, 387–390. [CrossRef]

- Panchenko, E.Yu; Timofeeva, E.E.; Chumlyakov, Y.I.; Osipovich, K.S.; Tagiltsev, A.I.; Gerstein, G.; Maier H.J., Compressive shape memory actuation response of stress-induced martensite aged Ni51Fe18Ga27Co4 single crystals. Mat. Sci. & Eng. 2019, A746, 448–455. [CrossRef]

- Morito, H.; Fujita A.; Oikawa K.; Ishida K.; Fukamichi K.; Kainuma, R. Stress assisted magnetic-field-induced strain in Ni-Fe-Ga-Co ferromagnetic shape memory alloys, Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90, 062505. [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, K.; Ren, X. Recent developments in the research of shape memory alloys, Intermetallics 1999, 7, 511-528. [CrossRef]

- Daróczi, L.; Gyöngyösi, S.; Tóth, L.Z.; Szabó, S.; Beke D.L. Jerky magnetic noises generated by cyclic deformation of martensite in Ni2MnGa single crystalline shape memory alloys, Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 106, 041908. [CrossRef]

- Daróczi L.; Gyöngyösi, S.; Tóth, L.Z.; Beke D.L., Effect of the martensite twin structure on the deformation induced magnetic avalanches in Ni2MnGa single crystalline samples Scr. Mater. 2016, 114, 161-164. [CrossRef]

- Bronstein, E.; Tóth, LZ.; Daróczi L.; Beke D.L.; Talmon R.; Shilo D.; Tracking Twin Boundary Jerky Motion at Nanometer and Microsecond Scales, Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2106573. [CrossRef]

- Perevertov, A.; Sevcik, M.; Heczko O. Correlation between Acoustic Emission and Stress Evolution during Single Twin Boundary Motion in Ni-Mn-Ga Magnetic Shape Memory Single Crystal, Phys, Status Solidi, RRL 2022, 17, 2200245. [CrossRef]

- Vives, E.; Soto-Parra, D.; Manosa, L.; Romero R.; Planes A. Driving-induced crossover in the avalanche criticality of martensitic transitions Phys. Rev. B 2009, 80, 180101. [CrossRef]

- Beke, D.L.; Daróczi, L.; Tóth, L.Z.; Kalmárné Bolgár, M.; Samy, N.M.; Hudák, A., Acoustic Emissions during Structural Changes in Shape Memory Alloys, Metals 2019, 9, 58; https://. [CrossRef]

- Setna, J.P.; Dahmen, K.A.; Myers, C.R. Crackling noise. Nature 2001, 410, 242–250. [CrossRef]

- Kuntz, M.C.; Setna, J.P. Noise in disordered systems: The power spectrum and dynamic exponents in avalanche models. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 62, 11699. [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, M.; Angheluta, L.; Dahmen, K.; Goldenfeld, N., Universal fluctuations and extreme statistics of avalanches near the depinning transition. Phys. Rev. E 2013, 87, 022126. [CrossRef]

- Papanikolaou, S.; Bohn, F.; Sommer, R.L.; Durin, G.; Zapperi, S.S.; Setna, J.P. Universality beyond power laws and the average avalanche shape. Nat. Phys. 2011, 7, 316–320. [CrossRef]

- Laurson, L.; Illa, X.; Santucci, S.; Tallakstad, K.T.; Maloy, K.J.; Alava, M.J. Evolution of the average avalanche shape with the universality class. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2927. [CrossRef]

- Kamel, S.M.; Samy, N.M.; Tóth, L.Z.; Daróczi, L.; Beke, D.L. Denouement of the Energy-Amplitude and Size-Amplitude Enigma for Acoustic-Emission Investigations of Materials. Materials 2022, 15, 4556. [CrossRef]

- Casals, B.; Dahmen, K.A.; Gou, B.; Rooke, S.; Salje, E.K.H. The duration-energy-size enigma for acoustic emission. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5590. [CrossRef]

- Spark, G.; Maas, R. Shapes and velocity relaxation of dislocation avalanches in Au and Nb microcrystals. Acta Mater. 2018, 152, 86–95. [CrossRef]

- Planes, A.; Manosa, L; Vives, E.; J. Alloys Compd. Acoustic emission in martensitic transformations2013, 577, S699-S704. [CrossRef]

- Dobrinevski, A.; Le Doussal, P.; Wiese, K. J. Statistics of avalanches with relaxation and Barkhausen noise: a solvable model. Phys. Rev. E, 2013, 88, 032106. [CrossRef]

- Dobrinevski, A.; Le Doussal, P.; Weise, K.J. Avalanche shape and exponents beyond mean-field theory. EPL 2015, 108, 66002. [CrossRef]

- Chi-Cong, Vu.; Weiss, J. Asymmetric Damage Avalanche Shape in Quasibrittle Materials and Subavalanche (Aftershock) Clusters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 125, 105502. [CrossRef]

- Antonaglia, J.; Wright, W.J.; Gu, X.; Byer, R.R.; Hufnagel, T.C.; LeBlanc, M.; Uhl, J.T.; Dahmen, K.A. Bulk metallic glasses deform via avalanches. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 112, 1555501. [CrossRef]

- Tóth, L.Z.; Bronstein, E.; Daróczi, L.; Shilo, D.; Beke D.L. Scaling of average avalanche shapes for acoustic emission during jerky motion of single twin boundary in single-crystalline Ni2MnGa, Materials, 2023, 16, 2089. [CrossRef]

- Kamel, S.M.; Daróczi, L.; Tóth, L.Z.; Panchenko, E.Y.; Chumlyakov, Y.I.; Samy, N.M.; Beke D.L. Acoustic emission and DSC investigations of anomalous stress-stain curves and burst like shape recovery of Ni49Fe18Ga27Co6 shape memory single crystals, Intermetallics 2023, 159, 107932. [CrossRef]

- Bolgár, M.K.; Tóth, L.Z.; Szabó, S.; Gyöngyösi, S.; Daróczi, L.; Panchenko, E.I.; Chumlyakov, Y.I; Beke D.L. Thermal and acoustic noises generated by austenite/martensite transformation in NiFeGaCo single crystals.J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 658, 29–35. [CrossRef]

- Tóth, L.Z. Daróczi, L.; Szabó, S.; Beke, D.L. Simultaneous investigation of thermal, acoustic, and magnetic emission during martensitic transformation in single-crystalline Ni2MnGa, Phys. Rev. 2017, B93, 144108. [CrossRef]

- Clauset, A.; Shalizi, C.R.; Newman, M.E. Power-Law Distributions in Empirical Data. SIAM Rev. 2009, 51, 661–703. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25662336.

- Beke, D.L.; Bolgar, M.K.; Toth, L.Z.; Daroczi L., On the asymmetry of the forward and reverse martensitic transformations in shape memory alloys, J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 741, 106–115. [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, K.; Ren, X,; Mechanism of martensite aging effects and new aspects, Mater. Sci. Eng. 2001, A312, 207–218. [CrossRef]

- Timofeeva, .E..; Panchenko, E. Yu.; Tokhmetova, A.B.; Eftifeeva, A.B.; Chumlyakov, Yu.I; Volochaev, M.N.; The cyclic stability of rubber-like behaviour in stress-induced martensite aged Ni49Fe18Ga27Co6 (at.%) single crystals, Mat. Lett. 2021, 300, 130207. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, J.-z.; Zeng, L.-y.; Wang, S.; Song, X.-y.; Chen, N.-l.; Zuo, X.-w.; Rong, Y.-h. Revealing dislocation activity modes 980 during yielding and uniform deformation of low-temperature tempered steel by acoustic emission. Journal of Iron and Steel 981 Research International 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ozgowicz, W.; Grzegorczyk, B.; Pawełek, A.; Pia̧tkowski, A.; Ranachowski, Z. The Portevin - Le Chatelier effect and acoustic 923 emission of plastic deformation CuZn30 monocrystals. Arch Metall Mater 2014, 59, 183-188. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ding, X.; Sun J.; Salje, E.K.H. Thermal and athermal crackling noise in ferroelastic nanaostuctures, J of Phys. Condens Matter 2014, 26, 142201. [CrossRef]

- Nataf G.; Salje, E.K.H. Avalanches in ferroelectric and coelastic materials: Phase transition, domain switching and propagation, Feroelectrics, 2020, 569, 82-107. [CrossRef]

- Zreihan N.; Faran E.; Vives E.; Planes A.; Shilo D. Coexistence of a well-determined kinetic law and a scale-invariant power law during the same physical process. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 97, 014103. [CrossRef]

- Zreihan N.; Faran E.; Vives E.; Planes A.; Shilo D. Relations between stress drops and acoustic emission measured during mechanical loading. Phys. Rev. Mater, 2019, 3, 043603. [CrossRef]

- Daróczi, L.; Piros, E.; Tóth, L.Z.; Beke, D.L. Magnetic field induced random pulse trains of magnetic and acoustic noises in martensitic single-crystal Ni2MnGa. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 96, 014416. [CrossRef]

- Daróczi, L.; Hudák, A.; Tóth, L.Z.; Beke, D.L. Investigation of magnetic and acoustic emission during stress induced superplastic deformation of martensitic Ni2MnGa single crystal. In Proceedings of the 11th European Symposium on Martensitic Transformations, ESOMAT 2018, Section 5 No. 142, Metz, France, 27–31 August 2018.

- Samy, N.M.; Bolgár, M.K.; Barta N.;, Daróczi, L.; Tóth, L.Z.; Chumlyakov Y.I.; Karaman I.; Beke, D.L. Thermal, acoustic and magnetic noises emitted during martensitic transformation in single crystalline Ni45Co5Mn36.6In13.4 meta-magnetic shape memory alloy, J of Alloys and Comp. 2019, 778, 669-680. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Gou, B.; Yuan, B.; Ding, X.; Sun, J.; Salje, E.K.H. Multiple Avalanche Processes in Acoustic Emission Spectroscopy: Multibranching of the Erenergy-Amplitude Scaling, Phys. Stat. Sol. B 2021 2100465. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Gou, B.; Ding, X.; Sun, J.; Salje, E.K.H.; Fine structure of acoustic emission spectra: How to separate dsiclocation movements and entanglements in 316L stainless steel, Appl. Phy. Lett. 2020, 117, 262901. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Gou B.; Ding, X.; Sun, J.; Salje, E.K.H. Real-time monitoring dislocations, martensitic transfromations and detwinning in stainless steel: statistical analysis and mashine learning, J. Mat. Sci &Techn. 2021, 92, 31-39. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Gou, B,; Xu, X.; Ding, X.; Sun, J.; Salje E.K.H. Multibranches of acoustic emission as identifier for deformation mechanisms in additively manufactured 316L stainless steel, Additive Manufacturing 2023, 78, 103819. [CrossRef]

- McFaul, L.W.;Wright, W.J.;Sickle, J.; Dahmen, J.A., Force oscillations distort avalanche shapes, Mater. Res. Lett. 2019, 7, 456-502. [CrossRef]

- Tóth, L.Z.; Daróczi, L.; Elrasasi, T.Y.; Beke, D.L. Clustering Characterization of Acoustic Emission Signals Belonging to Twinning and Dislocation Slip during Plastic Deformation of Polycrystalline Sn. Materials 2022, 15, 6696. [CrossRef]

- Utsu, T.; Ogata, Y.; Matsu'ura, R.S. The Centenary of the Omori Formula for a Decay Law of Aftershock Activity, J. Phys. Earth, 1995, 43, 1-33. [CrossRef]

| P(E) ~ ε |

P(A) ~ α |

P(S) ~ δ |

ϕ |

ϕ |

| 1.5 | 2.3 | 1.6 |

| Single crystal | Summary | ε | α |

| Ni51Fe18Ga27Co4, this work, averaged | Rubber like, stress induced |

1.5±0.1 | 2.3±0.2 |

| Ni2MnGa [18] |

Single twin boundary Type I, stress induced |

2.3±0.2 | |

| Ni2MnGa [18] |

Single twin boundary Type II, stress induced (less than one decade energy range) |

3.0±0.2 | |

| Ni2MnGa [46] | Type II | 1.5±0.1 | |

| Ni2MnGa [47] | Type I | 1.5±0.1 | |

| Ni2MnGa [34] | Single twin boundary Type I, stress induced |

1.5±0.1 | 2.1±0.1 |

| Ni2MnGa [48] | after compression along the [100] direction, magnetic field induced | 1.5 ±0.1 | 1.8±0.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).