Submitted:

24 December 2024

Posted:

25 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Raw Materials

2.2. Extracts Preparation

2.3. Phytochemical Research

HPLC Methods

2.4. Pharmacological Research

2.4.1. Acute Toxicity

2.4.2. Antimicrobial Activity

2.4.3. Sedative Activity

2.4.4. Hepatoprotective Activity

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Phytochemical analysis of extracts

3.2. Pharmacological Research

3.2.1. Acute Toxicity

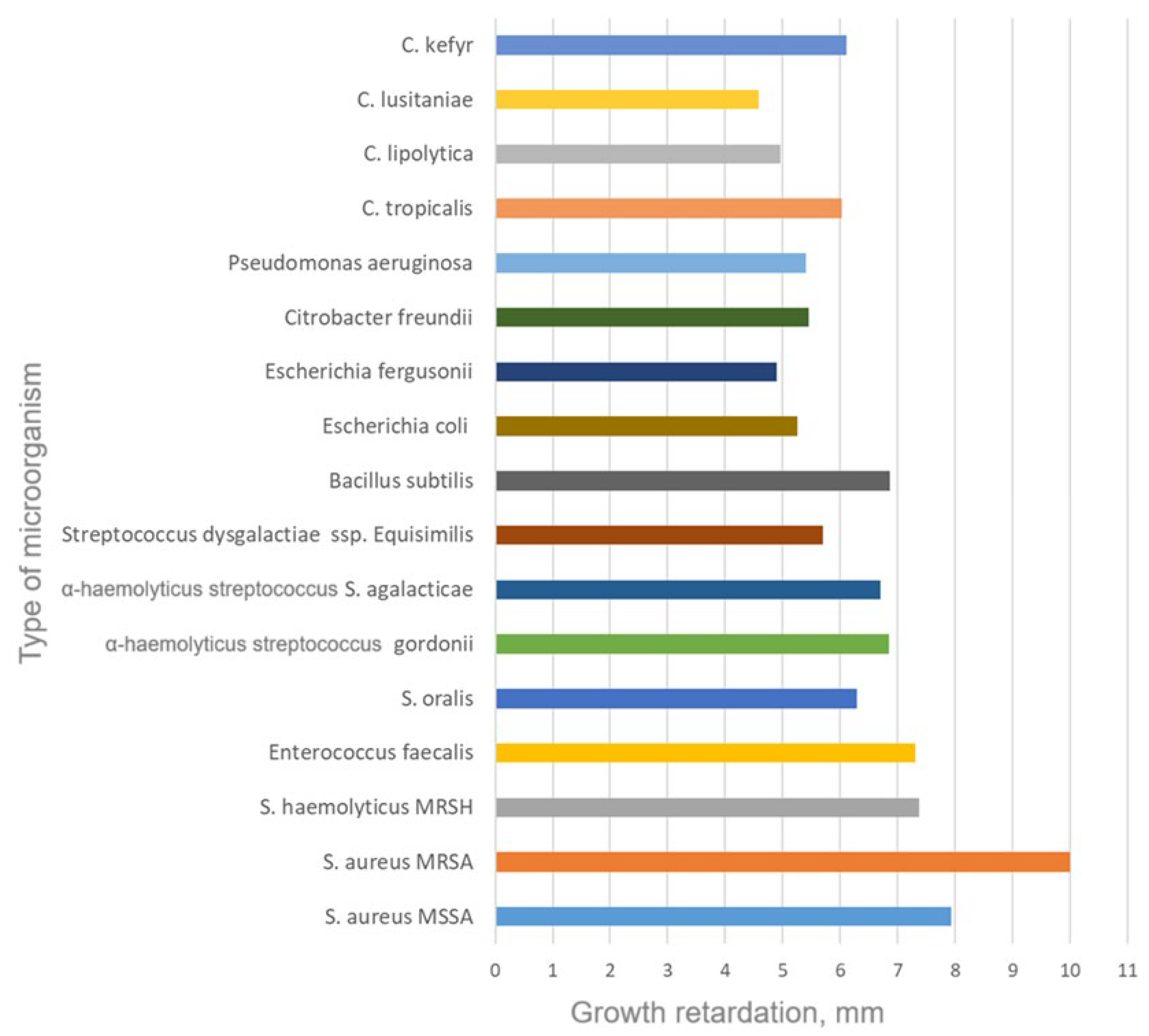

3.2.2. Antimicrobial Activity

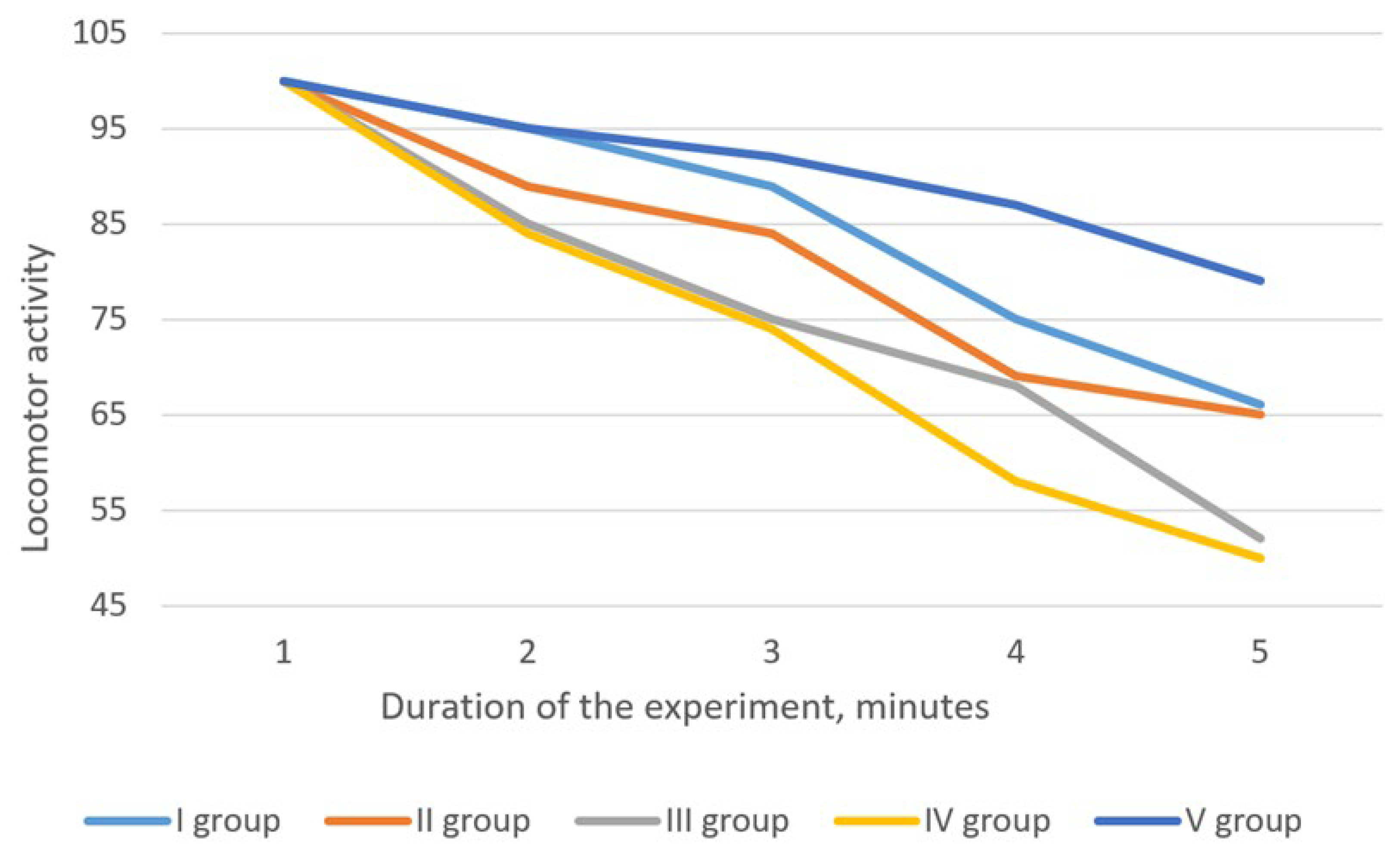

3.2.3. Sedative Activity

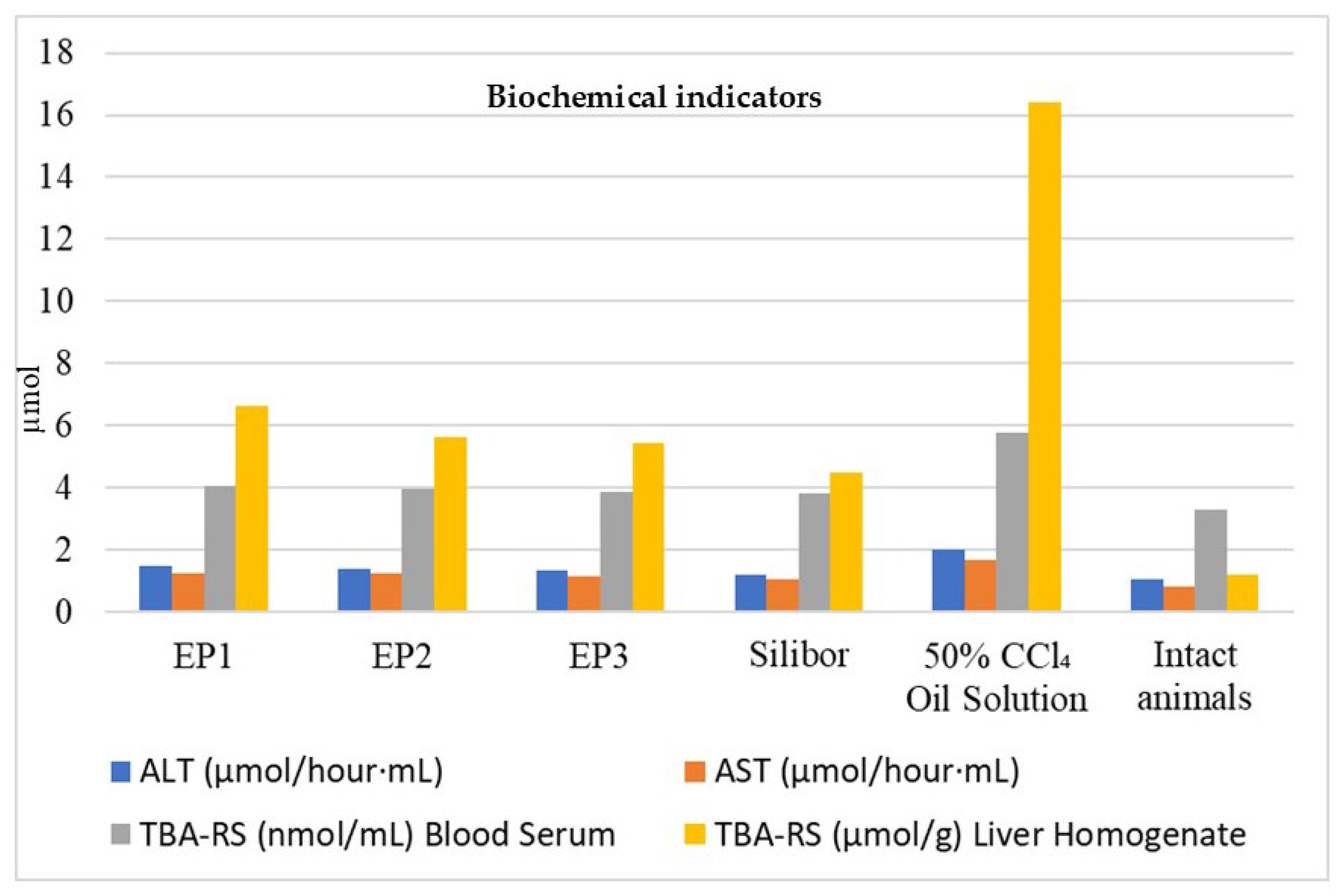

3.2.4. Hepatoprotective Activity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eryngium. The Plant List. Royal Botanic Gardens 2024. http://www.theplantlist.org/tpl1.1/search?q=Eryngium.

- Eryngium. International Plant Names Index, The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries and Australian National Botanic Gardens; 2024. https://www.ipni.org/n/30001853-2.

- BHL. Biodiversity Heritage Library. 2024. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/.

- Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. https://www.kew.org/.

- IUCN. Red List of Threatened Species 2024. https://www.iucnredlist.org/.

- Paun, G.; Neagu, E.; Moroeanu, V.; Albu, C.; Savin, S.; Lucian Radu, G. Chemical and Bioactivity Evaluation of Eryngium Planum and Cnicus Benedictus Polyphenolic-Rich Extracts. BioMed Research International 2019, 2019, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conea, S.; Vlase, L.; Chirila, I. Comparative Study on the Polyphenols and Pectin of Three Eryngium Species and Their Antimicrobial Activity. Cellulose Chemistry and Technology 2016, 50, 473–481. [Google Scholar]

- Thiem, B.; Kikowska, M.; Kurowska, A.; Kalemba, D. Essential Oil Composition of the Different Parts and In Vitro Shoot Culture of Eryngium Planum L. Molecules 2011, 16, 7115–7124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalczyk, M.; Masullo, M.; Thiem, B.; Piacente, S.; Stochmal, A.; Oleszek, W. Three New Triterpene Saponins from Roots of Eryngium Planum. Natural Product Research 2014, 28, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, T.L.M.; Silva, M.E.P.; Gurgel, E.S.C.; Oliveira, M.S.; Lucas, F.C.A. Eryngium Foetidum L. (Apiaceae): A Literature Review of Traditional Uses, Chemical Composition, and Pharmacological Activities. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2022, 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, D.; Zovko Končić, M.; Kosalec, I.; Košir, I.J.; Potočnik, T.; Čerenak, A.; Srečec, S.; Dunkić, V.; Vuko, E. Phytochemical Traits and Biological Activity of Eryngium Amethystinum and E. Alpinum (Apiaceae). Horticulturae 2021, 7, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calviño, C.I.; Levin, G.A. A New Species of Eryngium (Apiaceae, Saniculoideae) from the USA. Systematic Botany 2019, 44, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bährle-Rapp, M. Eryngium campestre. In Springer Lexikon Kosmetik und Körperpflege; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2007; pp. 189–189 ISBN 978-3-540-71094-3.

- Rehman, T.; Khan, Y.; Zeb, M.; Izhar, S. Phytochemical Analysis, Green Synthesis of Silver and Gold Nanoparticles, and Antibacterial Activity of Eryngium Amethystinum. Bioscience Research 2021, 18, 2788–2794. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal Laboratories. https://kamal.pk/.

- Homeopathic Pharmacopeia Convention of the United States (HPCUS); https://www.hpus.com/.

- Homeopathic Pharamacopeia of India (HPI); https://www.nhp.gov.in/.

- SEPPIC. CELTOSOMETM ERYNGIUM MARITIMUM. https://www.seppic.com/en/wesource/celtosome-eryngium-maritimum.

- Grodzinsky, A.M. Medicinal Plants: Encyclopedic Guide; Ukrainian encyclopedia named after M. P. Bazhana.; 1990.

- Derda, M.; Thiem, B.; Budzianowski, R. The Evaluation of the Amebicidal Activity of Eryngium Planum Extracts. Acta Poloniae Pharmaceutica 2013, 70, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Сonea, S.; Parvu, A.; Taulescu, M.; Vlase, L. Effects of Eryngium Planum and Eryngium Campestre Extracts on Ligatureinduced Rat Periodontitis Article. Digest Journal of Nanomaterials and Biostructures 2015, 693–704. [Google Scholar]

- Ozarowski, M.; Thiem, B.; Mikolajczak, P.L.; Piasecka, A.; Kachlicki, P.; Szulc, M.; Kaminska, E.; Bogacz, A.; Kujawski, R.; Bartkowiak-Wieczorek, J.; et al. Improvement in Long-Term Memory Following Chronic Administration of Eryngium Planum Root Extract in Scopolamine Model: Behavioral and Molecular Study. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2015, 2015, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanbeiglu, S.; Hosseini, K.; Molavi, O.; Asgharian, P.; Tarhriz, V. Eryngium Billardieri Extract and Fractions Induce Apoptosis in Cancerous Cells. ACAMC 2022, 22, 2189–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convention on the Conservation of European Wild Flora and Fauna and Natural Habitats.; 1979.

- Dobrochaeva, D.N.; Kotov, M.I.; Prokudin, Y.N.; Barbarich, A.I. Key to Higher Plants of Ukraine; Naukova Dumka: Kyiv, Ukraine, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Melnyk, N.; Pawłowska, K.A.; Ziaja, M.; Wojnowski, W.; Koshovyi, O.; Granica, S.; Bazylko, A. Characterization of Herbal Teas Containing Lime Flowers – Tiliae Flos by HPTLC Method with Chemometric Analysis. Food Chemistry 2021, 346, 128929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kukhtenko, H.; Bevz, N.; Konechnyi, Y.; Kukhtenko, O.; Jasicka-Misiak, I. Spectrophotometric and Chromatographic Assessment of Total Polyphenol and Flavonoid Content in Rhododendron Tomentosum Extracts and Their Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity. Molecules 2024, 29, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasova, I.; Gontova, T.; Grytsyk, L.; Zhumashova, G.; Sayakova, G.; Boshkayeva, A.; Shanaida, M.; Koshovyi, O. Determination of Standardization Parameters of Oxycoccus Macrocarpus (Ait.) Pursh and Oxycoccus Palustris Pers. Leaves. SR: PS 2022, 48–57. [CrossRef]

- Vronska, L.V. Chromatographic Profile of Hydroxycinnamic Acids of Dry Extract of Blueberry Shoots. Pharmaceutical journal 2019, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hordiei, K.; Gontova, T.; Trumbeckaite, S.; Yaremenko, M.; Raudone, L. Phenolic Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Tanacetum Parthenium Cultivated in Different Regions of Ukraine: Insights into the Flavonoids and Hydroxycinnamic Acids Profile. Plants 2023, 12, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starchenko, G.; Hrytsyk, A.; Raal, A.; Koshovyi, O. Phytochemical Profile and Pharmacological Activities of Water and Hydroethanolic Dry Extracts of Calluna Vulgaris (L.) Hull. Herb. Plants 2020, 9, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovaleva, A.M.; Abdulkafarova, E.R. Phenolic Compounds from Potentilla Anserina. Chem Nat Compd 2011, 47, 446–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Pharmacopoeia; 11th ed.; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, 2022.

- State Pharmacopoeia of Ukraine; 2nd ed.; Ukrainian Scientific Pharmacopoeial Center of Drugs Quality: Kharkiv, Ukraine, 2015.

- Hrytsyk, Y.; Koshovyi, O.; Hrytsyk, R.; Raal, A. Extracts of the Canadian Goldenrod (Solidago Canadensis L.) – Promising Agents with Antimicrobial, Anti-Inflammatory and Hepatoprotective Activity. ScienceRise: Pharmaceutical Science 2024, 78–87. [CrossRef]

- European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals Used for Experimental and Other Scientific Purposes 1999.

- Council Directive 2010/63/EU on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific Purposes 2010.

- On Approval of the Procedure for Preclinical Study of Medicinal Products and Examination of Materials of Preclinical Study of Medicinal Products; 2009.

- Stefanov, O.V. Preclinical Studies of Drugs; Avicenna: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2001.

- Bergey, D.H. Bergey’s Manual of Determinative Bacteriology; Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins Co, 1957.

- Kutsyk, R.V. Screening Study of the Antimicrobial Activity of Medicinal Plants of the Carpathian Region against Polyantibiotic-Resistant Clinical Strains of Staphylococci. Message 1. Galician Medical Bulletin 2004, 11, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kutsyk, R. Study of Antimicrobial Activity of Medicinal Plants of the Carpathian Region against Antibiotic-Resistant Clinical Strains of Staphylococci. Galician Medical Herald 2005, 12, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Huzio, N.; Grytsyk, A.; Raal, A.; Grytsyk, L.; Koshovyi, O. Phytochemical and Pharmacological Research in Agrimonia Eupatoria L. Herb Extract with Anti-Inflammatory and Hepatoprotective Properties. Plants 2022, 11, 2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovalenko, V.N. Compendium 2020. Medicines; MORION: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2020.

- Shanaida, M.; Oleschuk, O.; Lykhatskyi, P.; Kernychna, I. Study of the Hepatoprotective Activity of the Liquid Extract of the Garden Thyme Herb in Tetrachloromethane Hepatitis. Pharmaceutical journal 2017, 42, 92–97. [Google Scholar]

- Yezerska, O.; Gavrilyuk, M.; Gavrilyuk, O.; Nektyegaev, I.; Kalynyuk, T. Study of Hepatoprotective Activity of Chicory Extract (Cichorium Intybus L.). Current issues of pharmaceutical and medical science and practice 2014, 2023.

- Korobeinikova, E.N. Modification of Determination of Lipid Peroxidation Products in the Reaction with Thiobarbituric Acid. Laboratory work 1989, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lapach, S.N.; Chubenko, A.V.; Babich, P.N. Statistical Methods in Biomedical Research Using Excel; MORION: Kyiv, 2000.

- Konovalov, D.A.; Cáceres, E.A.; Shcherbakova, E.A.; Herrera-Bravo, J.; Chandran, D.; Martorell, M.; Hasan, M.; Kumar, M.; Bakrim, S.; Bouyahya, A.; et al. Eryngium Caeruleum: An Update on Ethnobotany, Phytochemistry and Biomedical Applications. Chin Med 2022, 17, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| № | Compound | Content in dense extract, µg/g | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EP1 | EP2 | EP3 | ||

| Hydroxycinnamic acids | ||||

| 1 | Chlorogenic acid | 3945.81±174.12 | 4931.72±215.32 | 4843.06±92.07 |

| 2 | Caffeic acid | 1268.87±94.14 | 1492.33±87.12 | 1319.78±79.16 |

| 3 | Syringic acid | 176.09±13.07 | 234.98±19.06 | 312.86±15.37 |

| 4 | p-Coumaric acid | 418.61±21.16 | 531.85±16.43 | 591.77±28.92 |

| 5 | trans-Ferulic acid | 729.98±31.88 | 910.11±29.19 | 937.32±51.06 |

| 6 | Sinapic acid | 3011.84±156.18 | 3532.33±141.82 | 3319.96±138.46 |

| 7 | trans-Cinnamic acid | 2358.07±93.61 | 2841.49±105.04 | 2909.52±135.47 |

| Flavonoids | ||||

| 8 | Rutin | 1382.762±102.04 | 2412.37±92.08 | 2631.62±108.37 |

| 9 | Quercetin-3-O-glucoside | 509.71±25.07 | 917.74±37.05 | 993.52±47.08 |

| 10 | Naringenin | 2944.71±172.73 | 4430.62±201.42 | 4873.07±212.92 |

| 11 | Neohesperidin | 989.72±39.09 | 2091.52±87.41 | 2313.43±93.36 |

| 12 | Quercetin | 697.92±29.93 | 1393.55±65.12 | 1493.72±72.17 |

| 13 | Kaempferol | 919.23±58.39 | 1801.17±11.03 | 1945.91±74.32 |

| Tannin metabolites | ||||

| 14 | Epicatechin | 1507.72±82.06 | 1420.08±73.93 | 1274.58±59.37 |

| 15 | Epicatechin gallate | 431.25±15.03 | 368.42±10.96 | 331.09±21.12 |

| 16 | Gallocatechin | 1607.71±57.86 | 1525.03±65.41 | 1318.62±45.16 |

| Content of compound groups, % | ||||

| Total polyphenols (%) | 14.92±0.48 | 17.52±0.61 | 21.84±0.97 | |

| Tannins (%) | 9.13±0.29 | 8.72±0.21 | 8.17±0.23 | |

| Flavonoids (%) | 3.11±0.14 | 5.71±0.26 | 6.19±0.13 | |

| Polysaccharides (%) | 21.14±0.95 | 7.73±0.36 | - | |

| Animal Group | Time spent, % | Number of downward glances | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closed arm | Open arm | In center | ||

| I group (EP1) | 60.9±3.10* | 34.2±1.71* | 4.9±0.22* | 5.7±0.29* |

| II group (EP2) | 53.1±2.85* | 40.8±1.25* | 6.1±0.29* | 6.8±0.30* |

| III group (EP3) | 48.3±2.41* | 44.5±1.21* | 7.2±0.31* | 6.5±0.35* |

| IV group (control) | 44.5±2.40 | 49.7±1.20 | 5.8±0.28 | 7.8±0.35 |

| V group (intact) | 78.8±2.89* | 16.2±0.82* | 5.0±0.19* | 3.5±0.12* |

| Group | Time of first exit (s) | Number of exits | Total duration of exits (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| I group (EP1) | 53.1±2.15* | 2.5±0.01* | 37.2±1.18* |

| II group (EP2) | 28.6±1.41* | 2.7±0.01* | 36.2±1.41* |

| III group (EP3) | 19.0±1.12* | 3.2±0.02* | 63.8±2.09* |

| IV group (control) | 14.3±0.92 | 5.0±0.02 | 78.0±2.14 |

| V group (intact) | 75.0±3.16* | 1.8±0.01* | 16.1±0.98* |

| Group | Time of first exit (s) | Number of exits | Total duration of exits (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| I group (EP1) | 23.0±0.98* | 6.5±0.15 | 33.2±1.22 |

| II group (EP2) | 12.7±0.51 | 10.2±0.20 | 48.2±1.25 |

| III group (EP3) | 10.3±0.12 | 7.5±0.15 | 63.6±1.65 |

| IV group (control) | 8.3±0.10 | 9.8±0.15 | 55.3±1.50 |

| V group (intact) | 28.2±0.26 | 3.8±0.15 | 13.2±0.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).