Submitted:

24 December 2024

Posted:

25 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

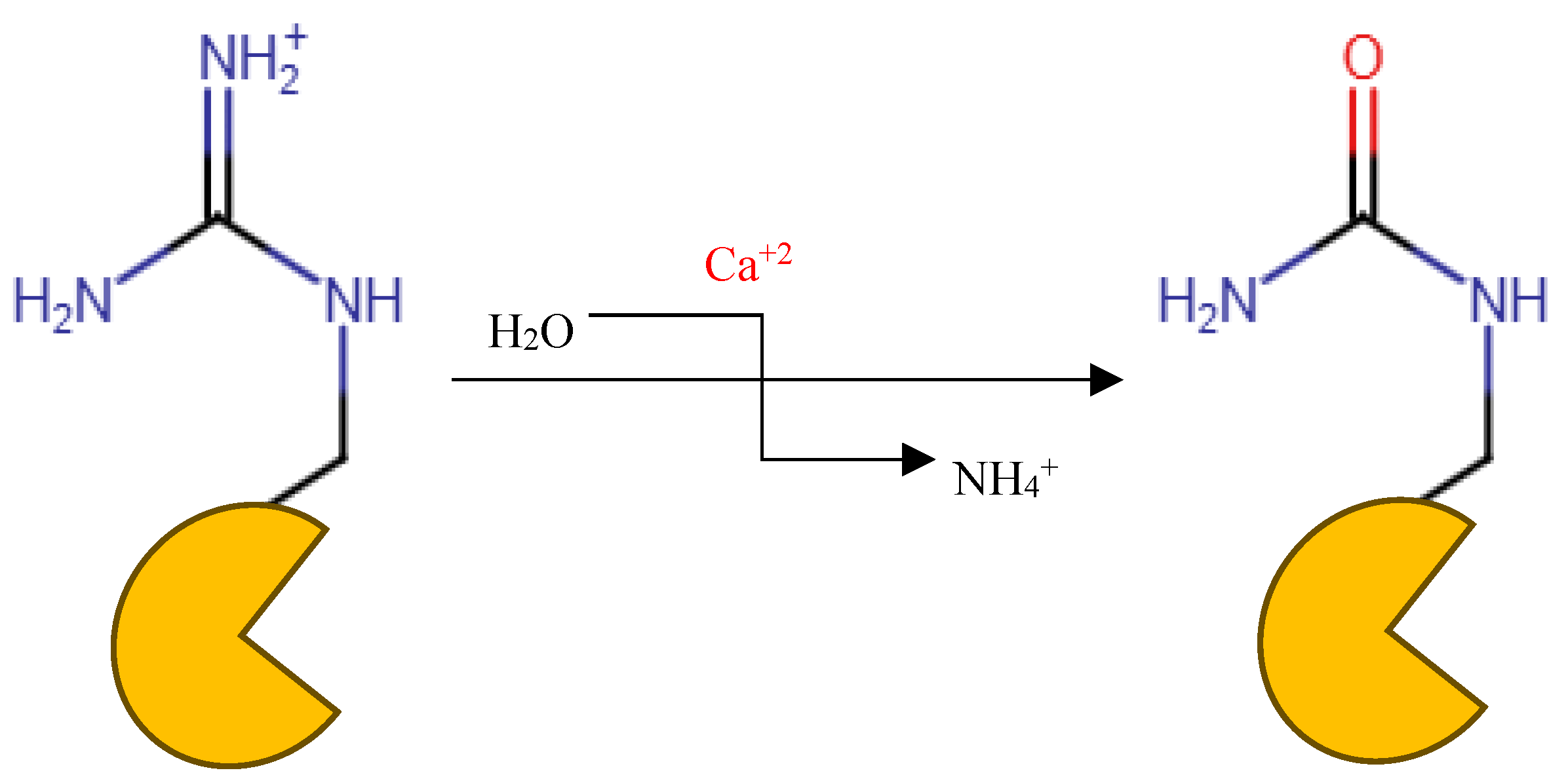

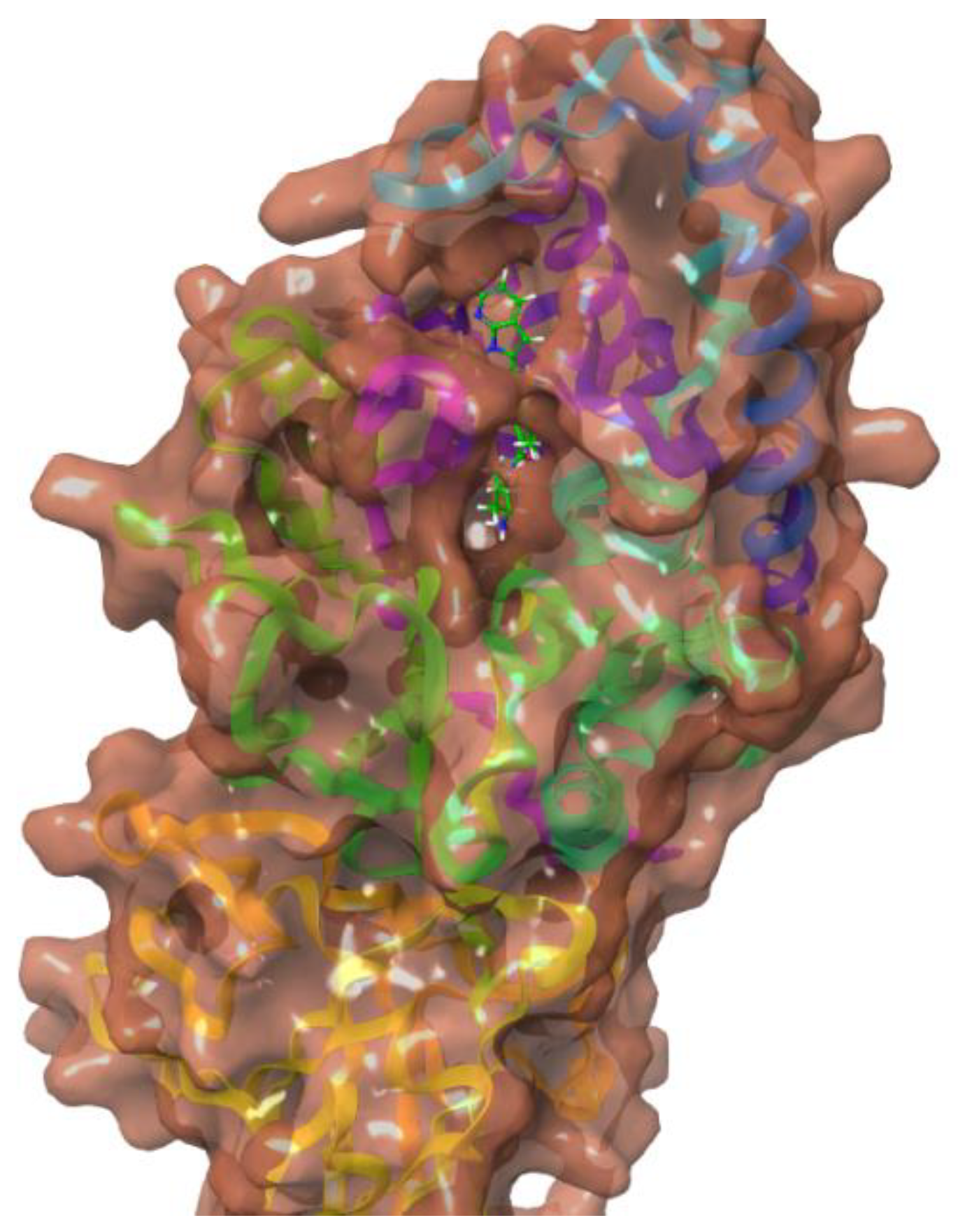

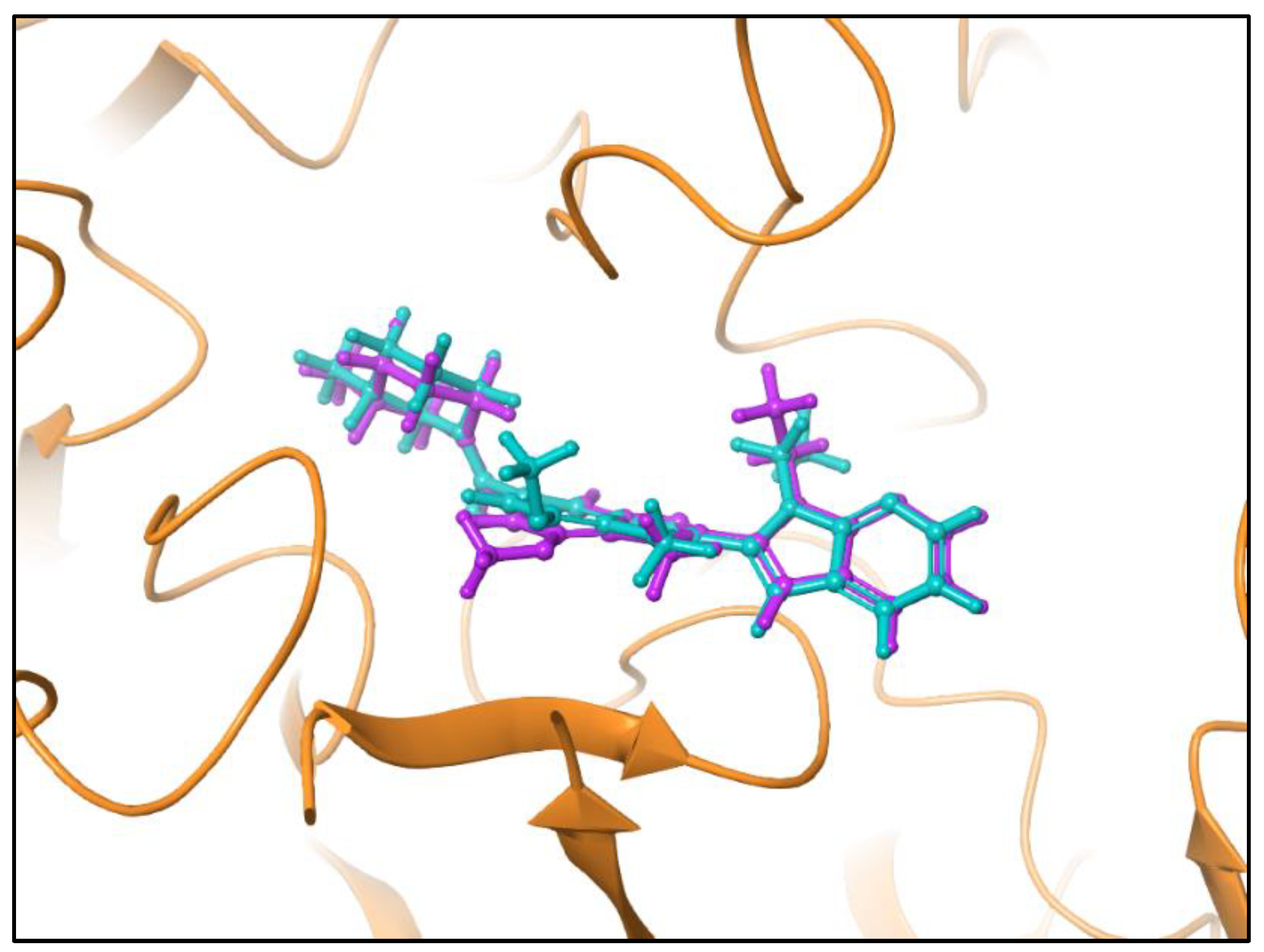

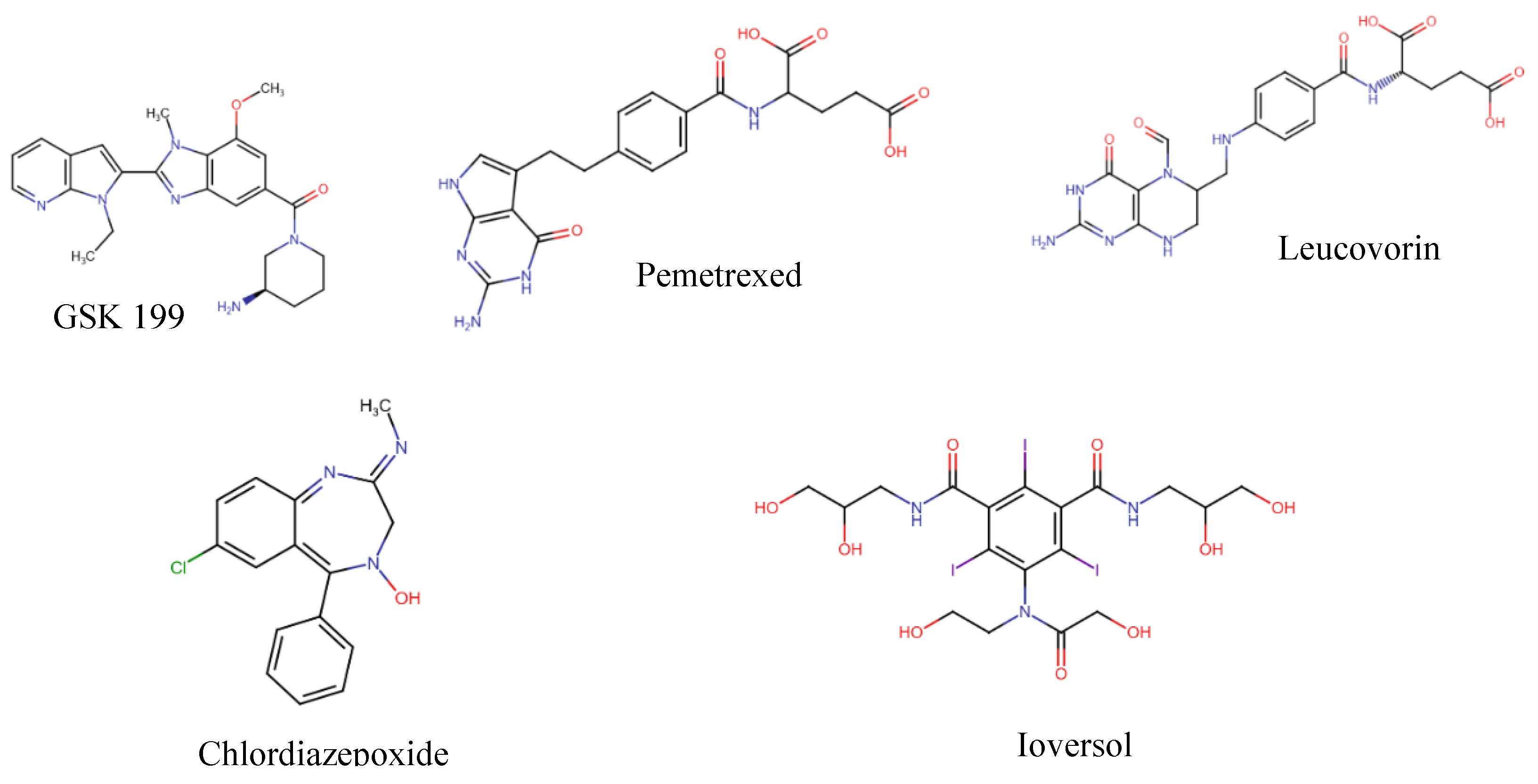

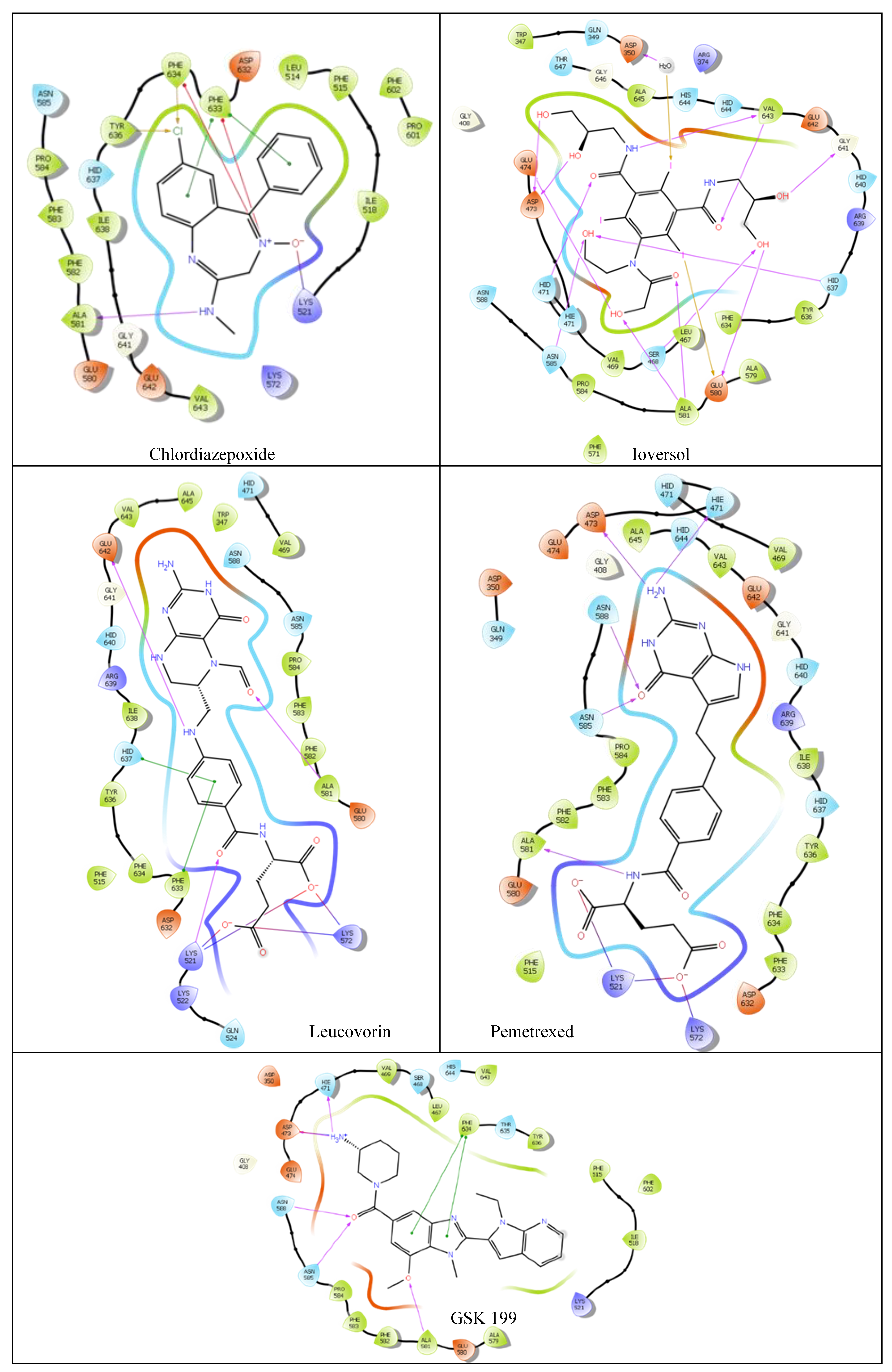

Background/Objectives: Neutrophil cells lysis forms the extracellular traps (NETs) to counter the foreign body during insults to the body. Peptidyl arginine deiminase (PAD) participates in this process and is then released into the extracellular fluid with the lysed cell components. In some diseases, patients with abnormal function of PADs, especially PAD 4, tend to form autoantibodies against the abnormal citrullinated proteins that are the result of PAD activity on arginine side chains. Those antibodies, which are highly distinct in RA are distinctly anti citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA). This study used an in-silico drug repurposing approach of FDA approved medications to identify potential alternative medications that can inhibit this process and address solutions to the current limitations of existing therapies. Methods: We utilized Maestro Schrödinger as a Computational tool for preparing and docking simulations on the PAD 4 enzyme crystal structure that is retrieved from RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 4X8G) while the docked FDA-approved medications are obtained from Zinc 15 database. The protein was bound to GSK 199 -investigational compound- as positive control for the docked molecules. Preparation of the protein was done by Schrödinger Protein Preparation Wizard tool. Binding Pocket Determination was done by Glide software and Validation of Molecular Docking carried out through redocking of GSK 199 and superimposition. After that, standard and induced fit docking were done. In molecular dynamics Desmond System Builder was utilized where the receptor-ligand complex was immersed in the TIP3P solvent model with a buffer containing 0.15M NaCl. ADMET properties prediction of hits were run by pkCSM website. Results/Conclusions: Among the four obtained hits Pemetrexed, Leucovorin, Chlordiazepoxide, and Ioversol, which showed the highest XP scores providing favorable binding interactions. The induced-fit docking (IFD) results displayed strong binding affinities of Ioversol, Pemetrexed, Leucovorin, Chlordiazepoxide in the order IFD values -11.617, -10.599, -10.521, -9.988, respectively. This research investigates Pemetrexed, Leucovorin, Chlordiazepoxide, and Ioversol as potential repurposing agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) as identified as PAD4 inhibitors. Keywords: PAD4; PAD IV; Rheumatoid arthritis; PAD4 activity; PAD4 inhibitor; Citrullination; Peptidyl arginine deiminase.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

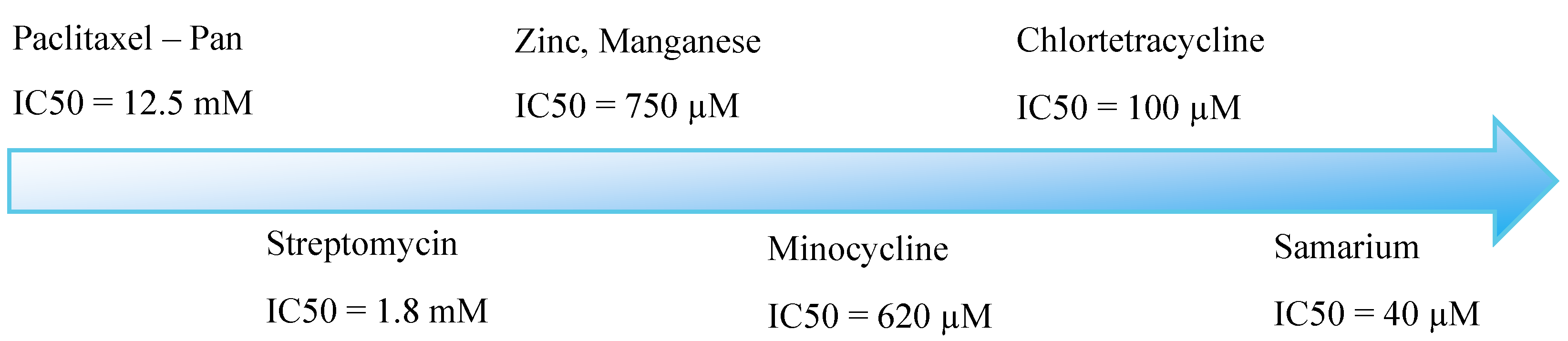

| Irreversible amidines (Pan inhibitors) | IC50 on PAD4 |

| F-amidine | 1.9µM |

| Cl-amidine | 22 µM |

| Reversible compounds (Selective) | |

| GSK199 | 200 nM |

| GSK484 | 50 nM |

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Computational Tools:

2.2. Generation of Databases and Ligand Library Preparation

2.3. Crystal Structure Retrieval and Preparation

2.4. Binding Pocket Determination and Validation of Molecular Docking

2.5. Standard Molecular Docking (Rigid)

2.6. Induced-Fit Docking (IFD) (Flexible)

2.7. Molecular Mechanics-Based Re-Scoring

2.8. Shape-Based Screen

2.9. ADMET Properties and Drug-Likeness Predictions

2.10. Quantum Chemical Calculations

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Docking Studies

3.2. Computational Analysis of the Four Hits Binding to PAD4

3.3. Binding Free Energies Analysis

3.4. Shape Similarity Prediction

3.5. ADMET and Drug-Likeness

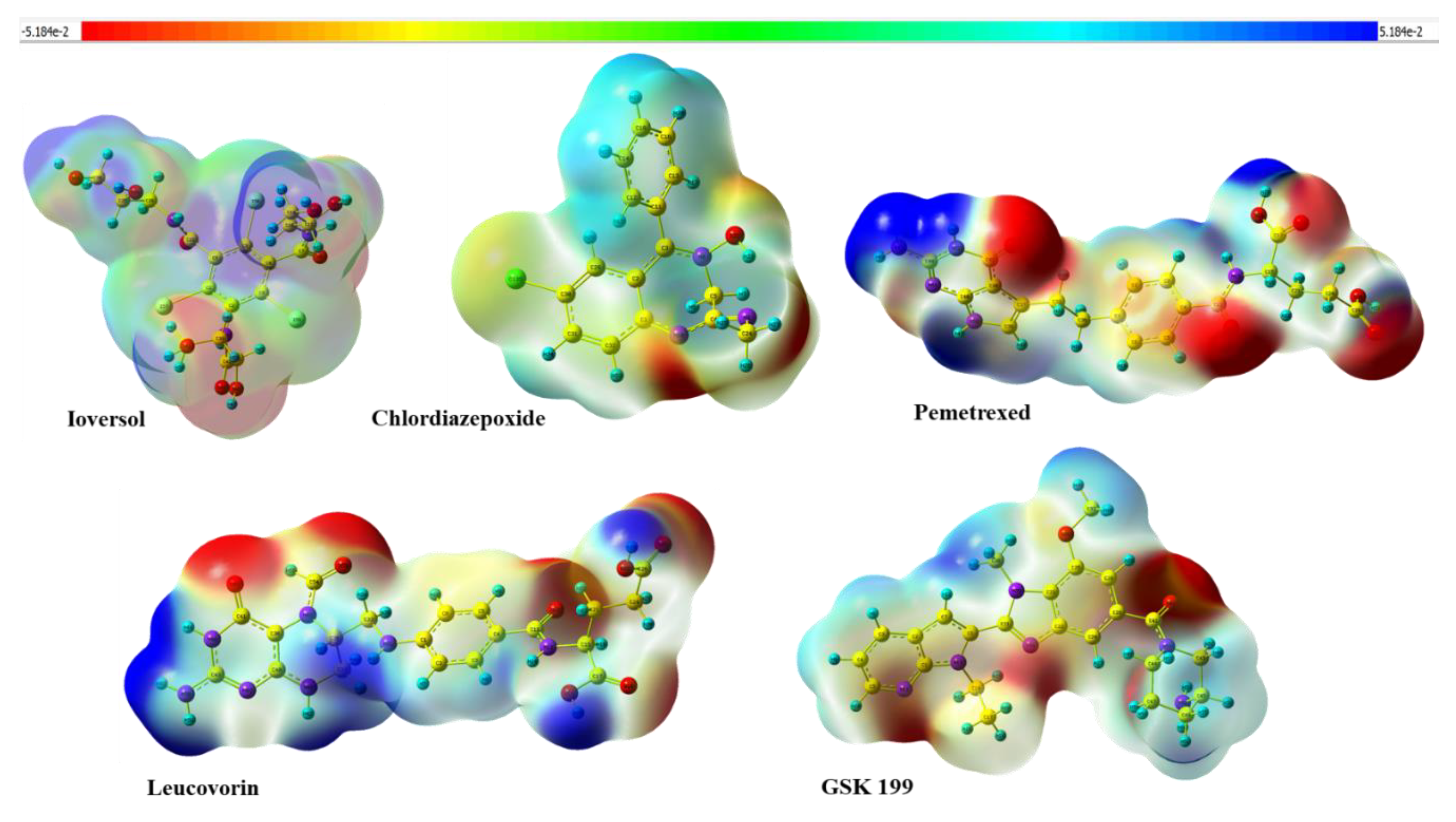

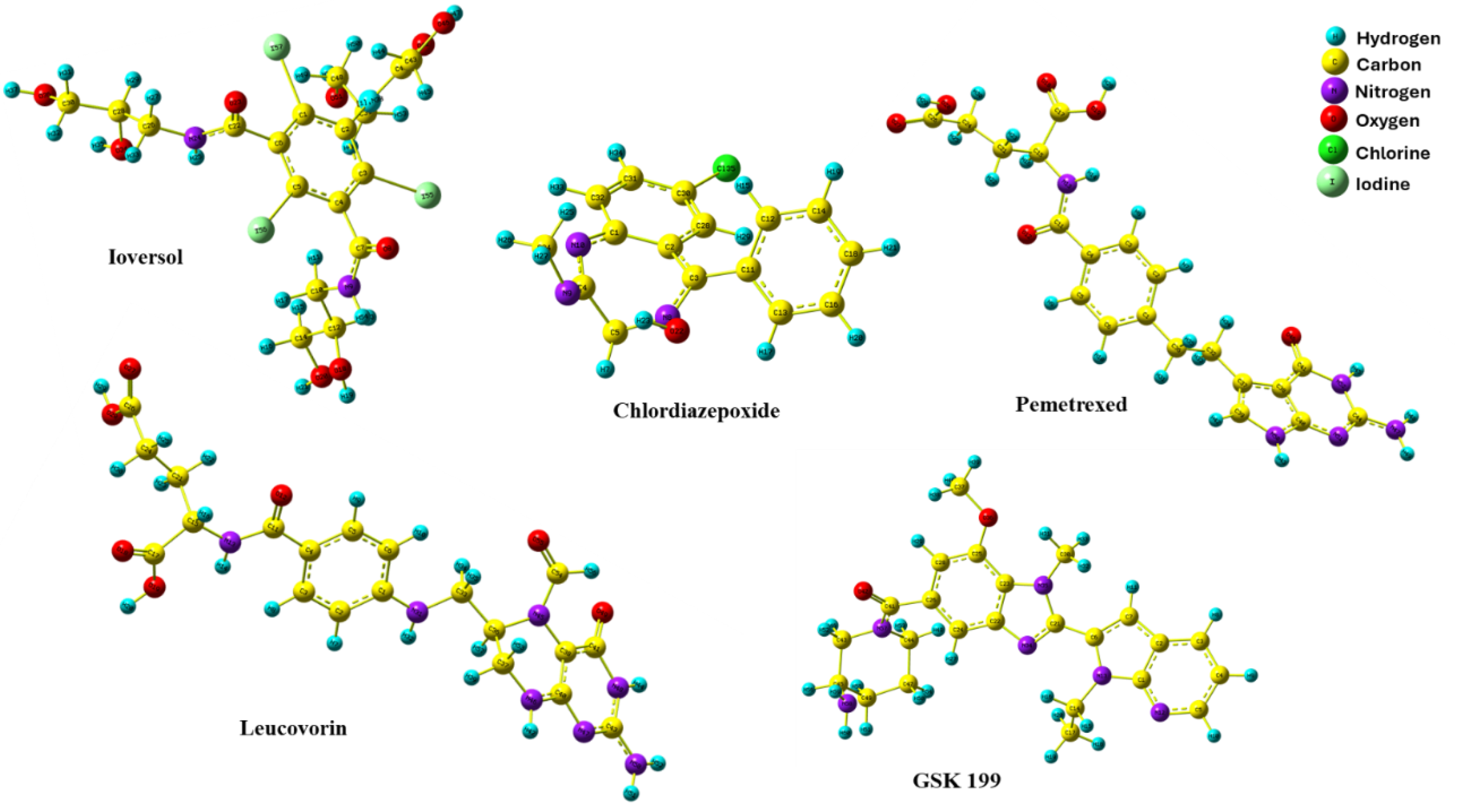

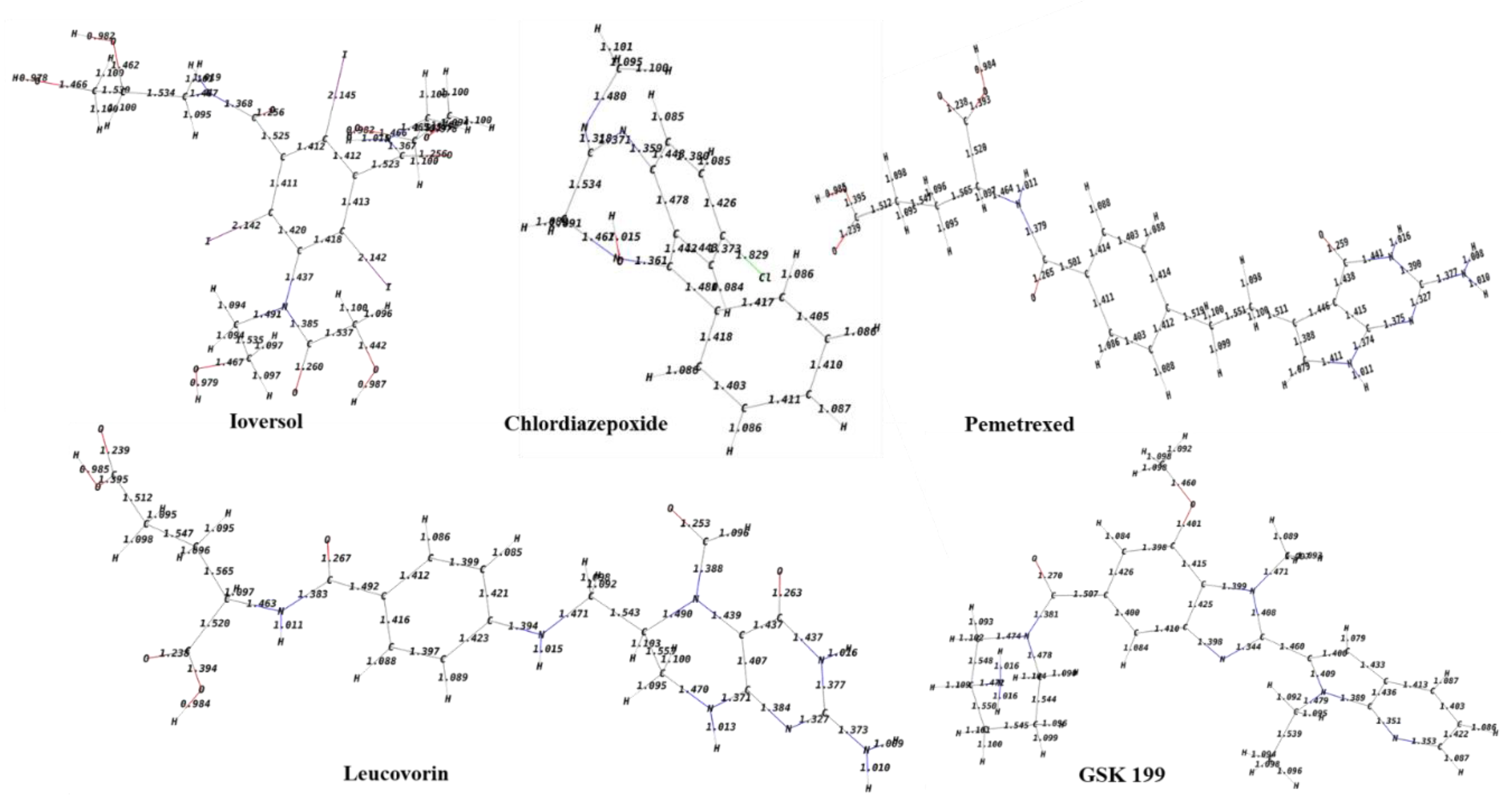

3.6. DFT Optimization Structures

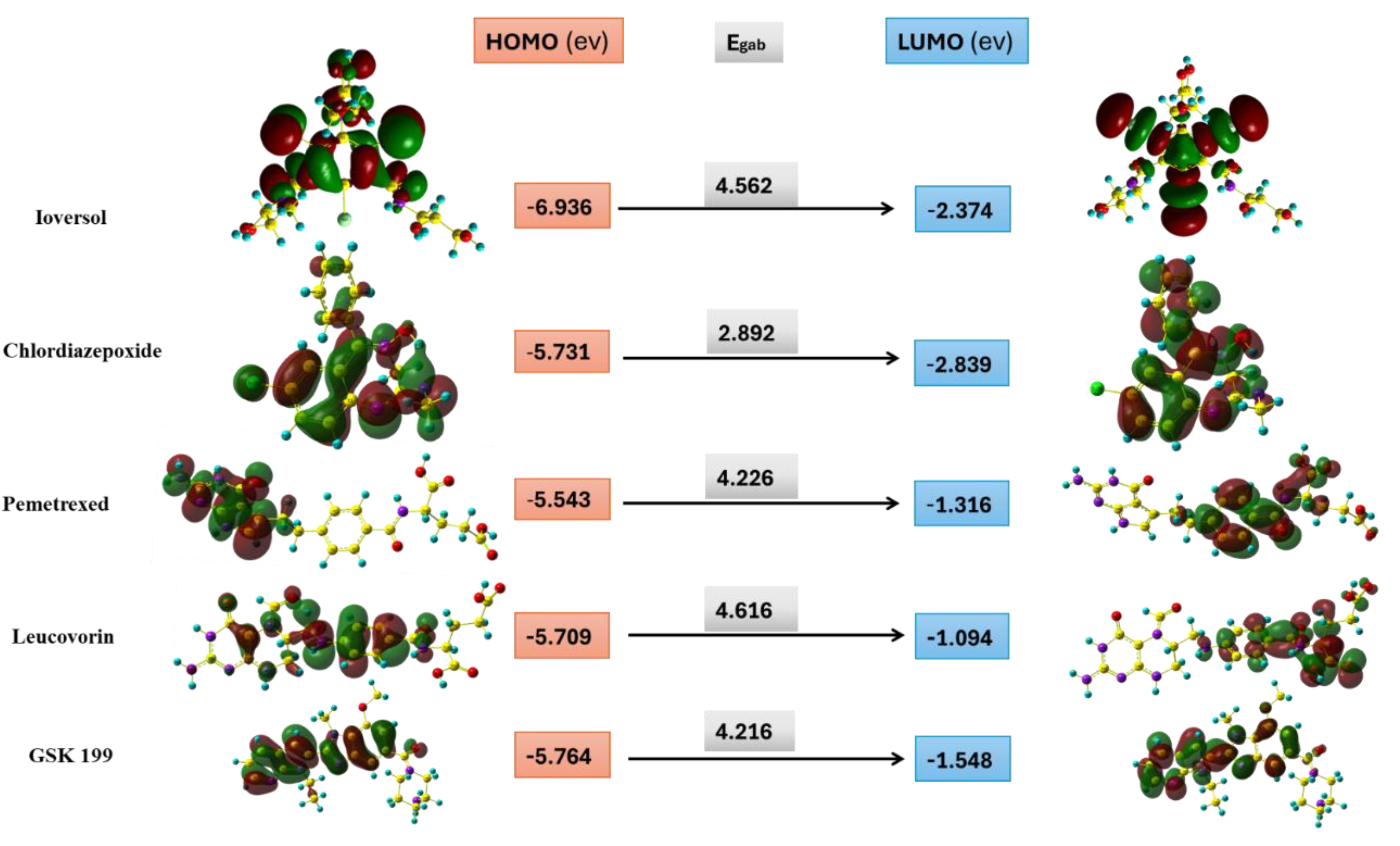

3.7. Frontier Molecular Orbital

3.8. Global Chemical Descriptors

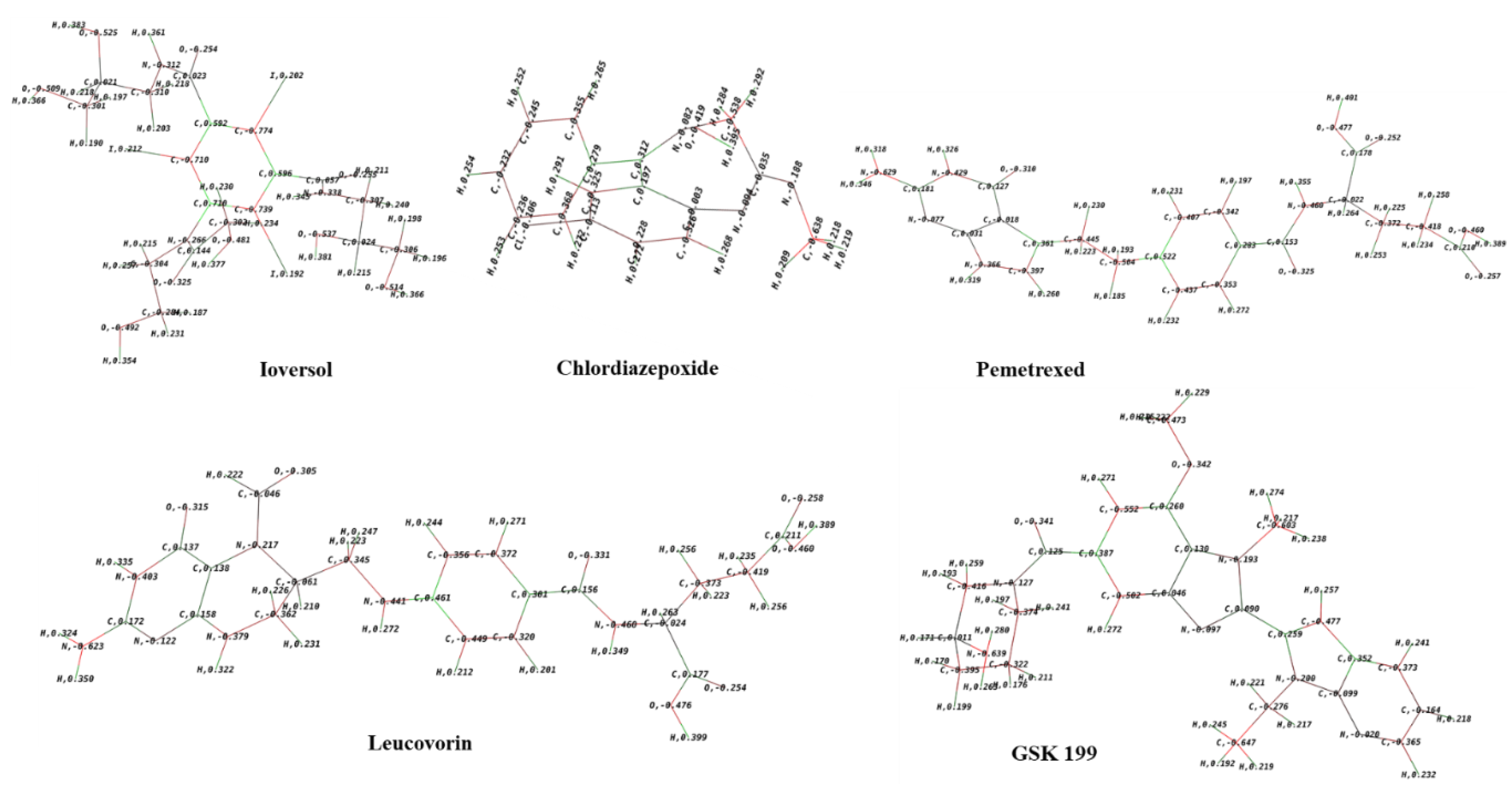

3.9. Molecular Electrostatic Potential and Mulliken population Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vossenaar, Erik R., et al. "PAD, a growing family of citrullinating enzymes: genes, features and involvement in disease." Bioessays 25.11 (2003): 1106-1118. [CrossRef]

- Jones, Justin, et al. "Protein arginine deiminase 4 (PAD4): Current understanding and future therapeutic potential." Current opinion in drug discovery & development 12.5 (2009): 616. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- E Witalison, Erin, Paul R Thompson, and Lorne J Hofseth. "Protein arginine deiminases and associated citrullination: physiological functions and diseases associated with dysregulation." Current drug targets 16.7 (2015): 700-710. [CrossRef]

- Asaga, Hiroaki, Michiyuki Yamada, and Tatsuo Senshu. "Selective deimination of vimentin in calcium ionophore-induced apoptosis of mouse peritoneal macrophages." Biochemical and biophysical research communications 243.3 (1998): 641-646. [CrossRef]

- Koushik, Sindhu, et al. "PAD4: pathophysiology, current therapeutics and future perspective in rheumatoid arthritis." Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets 21.4 (2017): 433-447. [CrossRef]

- Sabnis, Ram W. "Novel Peptidylarginine Deiminase Type 4 (PAD4) Inhibitors." ACS Medicinal Chemistry Letters 13.10 (2022): 1537-1538. [CrossRef]

- Strahl, Brian D., and C. David Allis. "The language of covalent histone modifications." Nature 403.6765 (2000): 41-45. [CrossRef]

- Zee, Barry M., et al. "Global turnover of histone post-translational modifications and variants in human cells." Epigenetics & chromatin 3 (2010): 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Bicker, Kevin L., and Paul R. Thompson. "The protein arginine deiminases: Structure, function, inhibition, and disease." Biopolymers 99.2 (2013): 155-163. [CrossRef]

- Arita, Kyouhei, et al. "Structural basis for Ca2+-induced activation of human PAD4." Nature structural & molecular biology 11.8 (2004): 777-783. [CrossRef]

- Cherrington, Brian D., et al. "Potential role for peptidylarginine deiminase 2 (PAD2) in citrullination of canine mammary epithelial cell histones." PloS one 5.7 (2010): e11768. [CrossRef]

- Jang, Byungki, et al. "Subcellular localization of peptidylarginine deiminase 2 and citrullinated proteins in brains of scrapie-infected mice: nuclear localization of PAD2 and membrane fraction-enriched citrullinated proteins.". Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology 70.2 (2011): 116-124. [CrossRef]

- Darrah, Erika, et al. "Peptidylarginine deiminase 2, 3 and 4 have distinct specificities against cellular substrates: novel insights into autoantigen selection in rheumatoid arthritis." Annals of the rheumatic diseases 71.1 (2012): 92-98. NIHMSID: NIHMS358568. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Masson-Bessiere, Christine, et al. "The major synovial targets of the rheumatoid arthritis-specific antifilaggrin autoantibodies are deiminated forms of the α-and β-chains of fibrin." The Journal of Immunology 166.6 (2001): 4177-4184. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Karen, and Paul Proost. "Insights into peptidylarginine deiminase expression and citrullination pathways." Trends in Cell Biology 32.9 (2022): 746-761. [CrossRef]

- Curran, Ashley M., et al. "PAD enzymes in rheumatoid arthritis: pathogenic effectors and autoimmune targets." Nature Reviews Rheumatology 16.6 (2020): 301-315. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Chao, et al. "Peptidylarginine deiminases 4 as a promising target in drug discovery." European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 226 (2021): 113840. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Prat, Laura, et al. Autoantibodies to protein-arginine deiminase (PAD) 4 in rheumatoid arthritis: immunological and clinical significance, and potential for precision medicine: Anti-PAD4 antibodies in RA. Expert review of clinical immunology 15.10 (2019): 1073-1087. [CrossRef]

- Damgaard, Dres, et al. "Relative efficiencies of peptidylarginine deiminase 2 and 4 in generating target sites for anti-citrullinated protein antibodies in fibrinogen, alpha-enolase and histone H3." PLoS One 13.8 (2018): e0203214. [CrossRef]

- Martín Monreal, María Teresa, et al. "Applicability of small-molecule inhibitors in the study of peptidyl arginine deiminase 2 (PAD2) and PAD4." Frontiers in Immunology 12 (2021): 716250. [CrossRef]

- Jones, J., Causey, C., Knuckley, B., Slack-Noyes, J. L., & Thompson, P. R. (2009). Protein arginine deiminase 4 (PAD4): Current understanding and future therapeutic potential. Current opinion in drug discovery & development, 12(5), 616. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, Dongmei, Cui Liu, and Jianping Lin. "Theoretical study of the mechanism of protein arginine deiminase 4 (PAD4) inhibition by F-amidine." Journal of Molecular Graphics and Modelling 55 (2015): 25-32. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Yuan, et al. "Inhibitors and inactivators of protein arginine deiminase 4: functional and structural characterization." Biochemistry 45.39 (2006): 11727-11736. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Luo, Yuan, et al. "A fluoroacetamidine-based inactivator of protein arginine deiminase 4: design, synthesis, and in vitro and in vivo evaluation." Journal of the American Chemical Society 128.4 (2006): 1092-1093. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Huw D., et al. "Inhibition of PAD4 activity is sufficient to disrupt mouse and human NET formation." Nature chemical biology 11.3 (2015): 189-191. [CrossRef]

- Jones, Justin E., et al. "Synthesis and screening of a haloacetamidine containing library to identify PAD4 selective inhibitors." ACS chemical biology 7.1 (2012): 160-165. [CrossRef]

- Causey, Corey P., et al. "The development of N-α-(2-carboxyl) benzoyl-N 5-(2-fluoro-1-iminoethyl)-l-ornithine amide (o-F-amidine) and N-α-(2-carboxyl) benzoyl-N 5-(2-chloro-1-iminoethyl)-l-ornithine amide (o-Cl-amidine). As second-generation protein arginine deiminase (PAD) inhibitors." Journal of medicinal chemistry 54.19 (2011): 6919-6935. [CrossRef]

- Knuckley, Bryan, Yuan Luo, and Paul R. Thompson. "Profiling Protein Arginine Deiminase 4 (PAD4): a novel screen to identify PAD4 inhibitors." Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry 16.2 (2008): 739-745. [CrossRef]

- Osada, A. , et al. "Citrullinated inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain 4 in arthritic joints and its potential effect in the neutrophil migration." Clinical & Experimental Immunology 203.3 (2021): 385-399. [CrossRef]

- Ali, Sikander, et al. "Understanding the role of peptidylarginine deiminases (PADs) in diseases and their inhibitors as potential therapeutic agents." European Journal of Pharmaceutical and Medical Research 4.6 (2017): 184-192.

- Ahmad, Faisal, et al. "Discovery of potential antiviral compounds against hendra virus by targeting its receptor-binding protein (G) using computational approaches." Molecules 27.2 (2022): 554. [CrossRef]

- Friesner, Richard A., et al. "Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy." Journal of medicinal chemistry 47.7 (2004): 1739-1749. [CrossRef]

- Sterling, Teague, and John J. Irwin. "ZINC 15–ligand discovery for everyone." Journal of chemical information and modeling 55.11 (2015): 2324-2337. [CrossRef]

- Shelley, John C., et al. "Epik: a software program for pK a prediction and protonation state generation for drug-like molecules." Journal of computer-aided molecular design 21 (2007): 681-691. [CrossRef]

- Jaundoo, Rajeev, et al. "Using a consensus docking approach to predict adverse drug reactions in combination drug therapies for gulf war illness." International Journal of Molecular Sciences 19.11 (2018): 3355. [CrossRef]

- Aldholmi, Mohammed, et al. "Anti-Infective Activity of Momordica charantia Extract with Molecular Docking of Its Triterpenoid Glycosides." Antibiotics 13.6 (2024): 544. [CrossRef]

- Alturki, MS. Exploring marine-derived compounds: In silico discovery of selective ketohexokinase (KHK) inhibitors for metabolic disease therapy. Mar Drugs. 2024;22(10):455. [CrossRef]

- Rants'o, Thankhoe A., C. Johan Van der Westhuizen, and Robyn L. van Zyl. "Optimization of covalent docking for organophosphates interaction with Anopheles acetylcholinesterase." Journal of Molecular Graphics and Modelling 110 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Dehbanipour, Razieh, and Zohreh Ghalavand. "Acinetobacter baumannii: Pathogenesis, virulence factors, novel therapeutic options and mechanisms of resistance to antimicrobial agents with emphasis on tigecycline.". Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 47.11 (2022): 1875-1884. [CrossRef]

- Massova, Irina, and Peter A. Kollman. "Combined molecular mechanical and continuum solvent approach (MM-PBSA/GBSA) to predict ligand binding." Perspectives in drug discovery and design 18 (2000): 113-135. [CrossRef]

- Vila, Jordi, and Jeronimo Pachon. "Therapeutic options for Acinetobacter baumannii infections: an update." Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy 13.16 (2012): 2319-2336. [CrossRef]

- Potron, Anais, Laurent Poirel, and Patrice Nordmann. "Emerging broad-spectrum resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii: mechanisms and epidemiology." International journal of antimicrobial agents 45.6 (2015): 568-585. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Ashutosh, and Kam YJ Zhang. "Advances in the development of shape similarity methods and their application in drug discovery." Frontiers in chemistry 6 (2018): 315. [CrossRef]

- Thapa, R. K., et al. (2017). Nanoformulations for antimicrobial therapy. Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control, 6, 2. [CrossRef]

- Duncan, Ken. "Progress in TB drug development and what is still needed." Tuberculosis 83.1-3 (2003): 201-207. [CrossRef]

- Stephens, Philip J., et al. "Ab initio calculation of vibrational absorption and circular dichroism spectra using density functional force fields. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Chengteh, Weitao Yang, and Robert G. Parr. "Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density." Physical review B 37.2 (1988): 785. [CrossRef]

- Hay, P. Jeffrey, and Willard R. Wadt. "Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for K to Au including the outermost core orbitals." The Journal of chemical physics 82.1 (1985). [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M. J. "Gaussian 09, Revision D. 01/Gaussian." (2009).

- Dennington, R. D. I. I. , Todd A. Keith, and John M. Millam. "GaussView, version 6.0. 16." Semichem Inc Shawnee Mission KS (2016).

- Chattaraj, Pratim Kumar, and Debesh Ranjan Roy. "Update 1 of: electrophilicity index." Chemical reviews 107.9 (2007): PR46-PR74. [CrossRef]

- Geerlings, Paul, Frank De Proft, and Wilfried Langenaeker. "Conceptual density functional theory." Chemical reviews 103.5 (2003): 1793-1874. [CrossRef]

- Chattaraj, Pratim Kumar, and Buddhadev Maiti. "HSAB principle applied to the time evolution of chemical reactions." Journal of the American Chemical Society 125.9 (2003): 2705-2710. [CrossRef]

- Pearson, Ralph G. "Absolute electronegativity and hardness correlated with molecular orbital theory." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 83.22 (1986): 8440-8441. [CrossRef]

- Pearson, Ralph G. "Absolute electronegativity and hardness: applications to organic chemistry." The Journal of Organic Chemistry 54.6 (1989): 1423-1430. [CrossRef]

- Fukui, Kenichi, et al. "Molecular orbital theory of orientation in aromatic, heteroaromatic, and other conjugated molecules." The Journal of Chemical Physics 22.8 (1954): 1433-1442. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Morales, Yosadara. "HOMO− LUMO gap as an index of molecular size and structure for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and asphaltenes: A theoretical study. I." The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 106.46 (2002): 11283-11308. [CrossRef]

- Murray, Jane S., and Peter Politzer. "Statistical analysis of the molecular surface electrostatic potential: an approach to describing noncovalent interactions in condensed phases." Journal of Molecular Structure: THEOCHEM 425.1-2 (1998): 107-114. [CrossRef]

- Mulliken, Robert S. "Electronic population analysis on LCAO–MO molecular wave functions. I." The Journal of chemical physics 23.10 (1955): 1833-1840. [CrossRef]

- Sherman, Woody, et al. "Novel procedure for modeling ligand/receptor induced fit effects." Journal of medicinal chemistry 49.2 (2006): 534-553. [CrossRef]

- Genheden, Samuel, and Ulf Ryde. "The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods to estimate ligand-binding affinities." Expert opinion on drug discovery 10.5 (2015): 449-461. [CrossRef]

- Sastry, G. Madhavi, Steven L. Dixon, and Woody Sherman. "Rapid shape-based ligand alignment and virtual screening method based on atom/feature-pair similarities and volume overlap scoring.". Journal of chemical information and modeling 51.10 (2011): 2455-2466. [CrossRef]

- Guengerich, F. Peter. "Mechanisms of drug toxicity and relevance to pharmaceutical development." Drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics 26.1 (2011): 3-14. [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, Christopher A., et al. "Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings." Advanced drug delivery reviews 23.1-3 (1997): 3-25. [CrossRef]

- Rosales-López, Antonio, et al. "Correlation between Molecular Docking and the Stabilizing Interaction of HOMO-LUMO: Spirostans in CHK1 and CHK2, an In Silico Cancer Approach." International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25.16 (2024): 8588. [CrossRef]

- Gheidari, Davood, Morteza Mehrdad, and Foroozan Hoseini. "Virtual screening, molecular docking, MD simulation studies, DFT calculations, ADMET, and drug likeness of Diaza-adamantane as potential MAPKERK inhibitors." Frontiers in Pharmacology 15 (2024): 13. [CrossRef]

- Nehra, Nidhi, Ram Kumar Tittal, and Vikas D. Ghule. "1, 2, 3-Triazoles of 8-hydroxyquinoline and HBT: Synthesis and studies (DNA binding, antimicrobial, molecular docking, ADME, and DFT)." ACS omega 6.41 (2021): 27089-27100. [CrossRef]

- Al Sheikh Ali, Adeeb, et al. "Design, synthesis, molecular modeling, anticancer studies, and density functional theory calculations of 4-(1, 2, 4-triazol-3-ylsulfanylmethyl)-1, 2, 3-triazole derivatives." ACS omega 6.1 (2020): 301-316. [CrossRef]

- Vargas, Rubicelia, Jorge Garza, and Andrés Cedillo. "Koopmans-like approximation in the Kohn− Sham method and the impact of the frozen core approximation on the computation of the reactivity parameters of the density functional theory.". The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 109.39 (2005): 8880-8892. [CrossRef]

| Compound | Glide Score Docking (Rigid) | Induced-Fit Docking (IFD) (Flexible) | Ionic Interactions | H- bond Interactions | Pi Pi- bond Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ioversol | -8.35 | -11.617 | NA | HID471 ASP473 GLU474 GLU580 ALA581 GLY641 H2O350 |

NA |

| Pemetrexed | -8.28 | -10.599 | LYS521 LYS572 |

HIE471 ASP473 ASN585 ASN588 ALA581 |

NA |

| Chlordiazepoxide | -5.23 | -9.988 | LYS521 PHE633 PHE634 |

ALA581 | PHE633 |

| Leucovorin | -4.16 | -10.521 | LYS521 LYS572 |

LYS521 ALA581 GLU642 |

PHE633 HID637 |

| GSK199 | -9.58 | NA | HIE471 ASP473 |

ALA581 ASN585 ASN588 |

PHE634 |

| Compound | ΔG bindinga |

|---|---|

| Ioversol | -53.53 |

| Leucovorin | -43.71 |

| Chlordiazepoxide | -30.96 |

| Pemetrexed | -28.46 |

| GSK199 (Control) | -107.15 |

| Compound | Shape Similaritya |

|---|---|

| Ioversol | 0.212 |

| Leucovorin | 0.258 |

| Chlordiazepoxide | 0.280 |

| Pemetrexed | 0.300 |

| GSK199 | 1 |

| ADMET Parameters/Compounds | GSK199 | Ioversol | Pemetrexed | Leucovorin | Chlordiazepoxide |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | |||||

| Water solubility (log mol/L) | -2.881 | -2.521 | -2.879 | -2.862 | -3.64 |

| Caco2 permeability (log Papp in 10-6 cm/s) | 1.531 | 0.172 | -1.162 | -1.187 | 1.229 |

| Intestinal absorption (human) (% Absorbed) | 93.652 | 22.978 | 15.394 | 0 | 96.327 |

| P-glycoprotein substrate (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Distribution | |||||

| BBB permeability (log BB) | -1.202 | -1.839 | -1.587 | -2.221 | 0.209 |

| CNS permeability (log PS) | -2.945 | -4.793 | -3.916 | -4.463 | -1.613 |

| Metabolism | |||||

| CYP2D6 substrate (Yes/No) | No | No | No | No | No |

| CYP3A4 substrate (Yes/No) | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| CYP1A2 inhibitor (Yes/No) | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| CYP2C19 inhibitor (Yes/No) | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| CYP2C9 inhibitor (Yes/No) | No | No | No | No | No |

| CYP2D6 inhibitor (Yes/No) | No | No | No | No | No |

| CYP3A4 inhibitor (Yes/No) | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Excretion | |||||

| Total Clearance (log ml/min/kg) | 0.911 | 0.146 | 0.189 | 0.091 | 0.22 |

| Renal OCT2 substrate (Yes/No) | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Toxicity | |||||

| AMES toxicity (Yes/No) | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Max. tolerated dose (human) (log mg/kg/day) | 0.325 | 0.823 | -0.292 | -0.554 | -0.054 |

| hERG I inhibitor (Yes/No) | No | No | No | No | No |

| Hepatotoxicity (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Molecule properties | GSK199 | Ioversol | Pemetrexed | Chlorthalidone | Leucovorin | Chlordiazepoxide |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | 468.989 | 807.114 | 427.417 | 338.772 | 473.446 | 299.761 |

| LogP | 3.6036 | -2.016 | 0.6664 | 0.9242 | -0.7311 | 1.8492 |

| #Acceptors | 7 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 9 | 3 |

| #Donors | 1 | 8 | 6 | 3 | 7 | 1 |

| Lipinski alert | Pass | Not Pass; 2 violations: Molecular weight >500; #Donors>5 | Pass; 1violation: #Donors>5 | Pass | Pass; 1violation: #Donors>5 | Pass |

| Compound | HOMO | LUMO | Global hardness (η) | Global softness (σ) |

Electronegativity ( ) )

|

Electrophilicity index(ώ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ioversol | -6.936 | -2.374 | 2.281 | 0.438 | 4.655 | 5.934 |

| Pemetrexed | -5.543 | -1.316 | 2.113 | 0.473 | 3.430 | 4.718 |

| Chlordiazepoxide | -5.731 | -2.839 | 1.446 | 0.691 | 4.285 | 1.512 |

| Leucovorin | -5.709 | -1.094 | 2.308 | 0.433 | 3.402 | 6.147 |

| GSK199 | -5.764 | -1.548 | 2.108 | 0.474 | 3.656 | 4.685 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).