1. Introduction

Anatomical variations of the renal vessels, both arterial and venous, are among the most common vascular abnormalities in humans, with incidence rates ranging from 4% to >60% in the renal arterial system and from 8.0% to ~40% in the venous system, depending on factors such as ethnicity, investigative methods (computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, surgical, or pathoanatomical data), and inclusion/exclusion criteria [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. The prevalence of accessory arteries is reported to range between 3% and 30% unilaterally and up to 10% bilaterally in various studies [

1,

4,

6,

7,

8]. Accessory veins are more frequently observed in the right renal vein (~16%) compared to the left (~2%), while other types of vascular malformations are less common [

1,

5,

9,

10].

Abnormalities in the development of renal vasculature encompass a highly heterogeneous group of vascular variations, and the clinical significance of many of these abnormalities remains undefined [

1,

4,

11,

12,

13]. Identification of variations in the renal vascular system is critical when planning interventions such as renal sympathetic denervation, aneurysm repair, renal transplantation, and other procedures [

1,

2,

6,

11,

12]. Certain vascular anomalies may also contribute to conditions such as hydronephrosis, varicocele, or orthostatic proteinuria [

1,

4,

9,

10,

12].

One important unresolved issue is the role of renal vascular variations in the development of arterial hypertension (HTN) [

1,

4,

11,

12,

13]. Renal vascular diseases are well-established causes of secondary (renal vascular) HTN [

14,

15,

16]. Certain conditions such as atherosclerotic renal artery disease, fibromuscular dysplasia, and specific types of vasculitis, are strongly associated with the development of HTN, which is often refractory to standard pharmacological treatment [

14,

15]. However, the role of anatomical renal vascular variations in the development of high blood pressure (BP), particularly resistant HTN, remains unconfirmed [

4,

5,

12,

13].

Given the relatively high prevalence of these abnormalities in the general population, we conducted this study to assess the overall prevalence and types of renal vascular abnormalities in patients with high BP, as well as their association with the development of treatment-resistant HTN.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted an observational, retrospective, non-interventional study. As an initial step, we consecutively screened 3,762 hypertensive patients who were hospitalized at our clinic between July 1, 2018, and March 27, 2024, for resistant HTN.

Inclusion criteria for our study were: 1) Age ≥18 years; 2) An established diagnosis of “Arterial hypertension” according to the 2024 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and 2023 European Society of Hypertension (ESH) Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of this disease [

14,

15]; 3) Maintenance of systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥90 mmHg after ≥1 month of treatment with optimal or best-tolerated doses of three or more drugs, including a thiazide/thiazide-like diuretic, an RAAS blocker (either an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) or an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB), and a calcium channel blocker (CCB); 4) Uncontrolled HTN confirmed by 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM); 5) Good adherence (≥80% of the treatment period) to the prescribed treatment; and 6) Patient agreement and signed informed consent at hospital admission to participate in all planned physical, instrumental, and laboratory investigations.

Exclusion criteria for the study were: 1) Patients with HTN at target BP values achieved using ≤3 antihypertensive drugs; 2) Patients with uncontrolled HTN using ≥3 drugs, but not at optimal doses or not including ACEi/ARB + CCB + thiazide/thiazide-like diuretic or a treatment period of <1 month; 3) Documented secondary HTN due to renal artery atherosclerotic/fibromuscular/vasculitis involvement, renal parenchymal disease, endocrinological, metabolic, cardiovascular or other diseases/conditions; 4) Patient clinical condition and/or comorbid factors/diseases making the planned instrumental investigations unfeasible.

After applying these criteria, we identified 128 (3.4%) of 3,762patients with resistant HTN. Of them, 63 (49.2%) were male, and 65 (50.8%) were female (p = 0.860). The median age was 58.0 years, with an interquartile range (IQR) of 46.0–69.0 years.

Using propensity score matching we matched these patients to 128 hypertensive patients, hospitalized at our clinic during the study period who had achieved target BP values (i.e. patients with controlled HTN). The control group had to meet the following inclusion criteria: 1) Office SBP 120–129 mmHg; 2) Office DBP 70–79 mmHg; 3) Mean 24-hour ABPM values <130 mmHg for SBP and <80 mmHg for DBP; 4) Mean daytime ABPM SBP <135 mmHg and <85 mmHg for DBP; 5) Mean nighttime ABPM SBP <120 mmHg for SBP and <70 mmHg for DBP; 6) Control of HTN achieved by ≤3 antihypertensive drugs (with a free or a single-pill combination if >1 drug used) from different classes at standard or maximal doses taken for at least 4 weeks; and 7) Patient agreement and signed informed consent at hospital admission to participate in all planned physical, instrumental, and laboratory investigations.

We conducted contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) imaging of the kidneys with renovasography for all participants in our study to determine the prevalence and types of anatomical variations in kidney vasculature. Additional instrumental investigations included electrocardiography (ECG), transthoracic echocardiography, 24-hour ABPM, and routine laboratory tests.

Patient information was collected using a structured questionnaire that included demographic characteristics, medical history (e.g., complaints, cardiovascular risk factors, comorbidities, and treatments), as well as clinical, instrumental, and laboratory findings of interest. Data were obtained directly from the patient’s hospitalization records and other available medical documents.

Cardiovascular risk was assessed based on the 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular prevention, as well as the 2024 ESC and 2023 ESH Guidelines for hypertension management [

14,

15,

17]. For apparently healthy individuals under 70 years of age without established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), diabetes mellitus (DM), chronic kidney disease (CKD), or genetic/rare lipid or blood pressure (BP) disorders, a 10-year estimation of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular risk was performed using the SCORE2 chart [

14,

15,

17]. This tool incorporates factors such as age, gender, smoking status, total cholesterol levels, and BP, calibrated to the country of residence. For individuals with ASCVD, DM, CKD, or genetic/rare lipid or BP disorders, cardiovascular risk was calculated using risk modifiers and the three cardiovascular risk categories recommended in the 2021 ESC Guidelines [

17].

The study was conducted following the ethical standards outlined in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments, guidelines for good clinical practice, and local regulations. Approval by a local ethics committee was not required for this type of clinical study/scientific research (observational, retrospective, non-interventional) in our country. All participants provided signed informed consent at hospital admission, agreeing to be examined and treated according to the diagnostic and treatment plan proposed by the clinician/hospital team, and that their results could be used anonymously for scientific purposes. The study was registered at

https://www.clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 7 February 2024) with reference number KPVB0001RH.

Statistical Analysis

For data processing and statistical analysis, we used IBM SPSS Statistics 19.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical variables were expressed as absolute numbers (percentage, %), and differences were evaluated using the chi-square test. Normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviation, and comparisons were made using the t-test for independent samples or analysis of variance. Non-normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as median (interquartile range) and compared using the Mann–Whitney U test or the Kruskal-Wallis H test. Association between the independent variables (renal vascular variations or normal renal vasculature) and the dependent variables (resistant vs. controlled HTN) was determined by logistic regression analysis with the strength of each variable demonstrated by the odds ratio (OR). A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Renal Vascular Characteristics

The contrast-enhanced CT imaging of the renal vasculature revealed anatomical variations in 64 (25%) of the 256 participants. These variations were more common in patients with resistant HTN, observed in 49 (38.3%) of 128 patients, compared to 15 (11.7%) of 128 patients with controlled HTN (p <0.001).

A variety of abnormalities in the renal vasculature were identified, with unilateral accessory renal arteries being the most frequent finding in both groups. However, this abnormality had a significantly higher prevalence in the resistant HTN group. Other more common findings included bilateral accessory renal arteries, the presence of two renal veins in a single kidney, and Nutcracker syndrome. The classic form of Nutcracker syndrome refers to the compression of the left renal vein between the abdominal aorta and the superior mesenteric artery [

18]. In our study, four patients presented with the classic form of Nutcracker syndrome, while one patient—a 28-year-old male—was diagnosed with the rarer right-sided Nutcracker syndrome, where the right renal vein was compressed between the abdominal aorta and the superior mesenteric artery.

Other renal vascular variants identified in our study population were also more prevalent in patients with resistant HTN. However, statistical analysis did not reveal significant differences between patients with resistant and controlled HTN regarding the prevalence of specific types of abnormalities. Among the 64 patients with congenital renal vascular abnormalities, 17 (26.6%) had two or more malformations.

Table 1 summarizes the types and prevalence of renal vascular variations observed in our study.

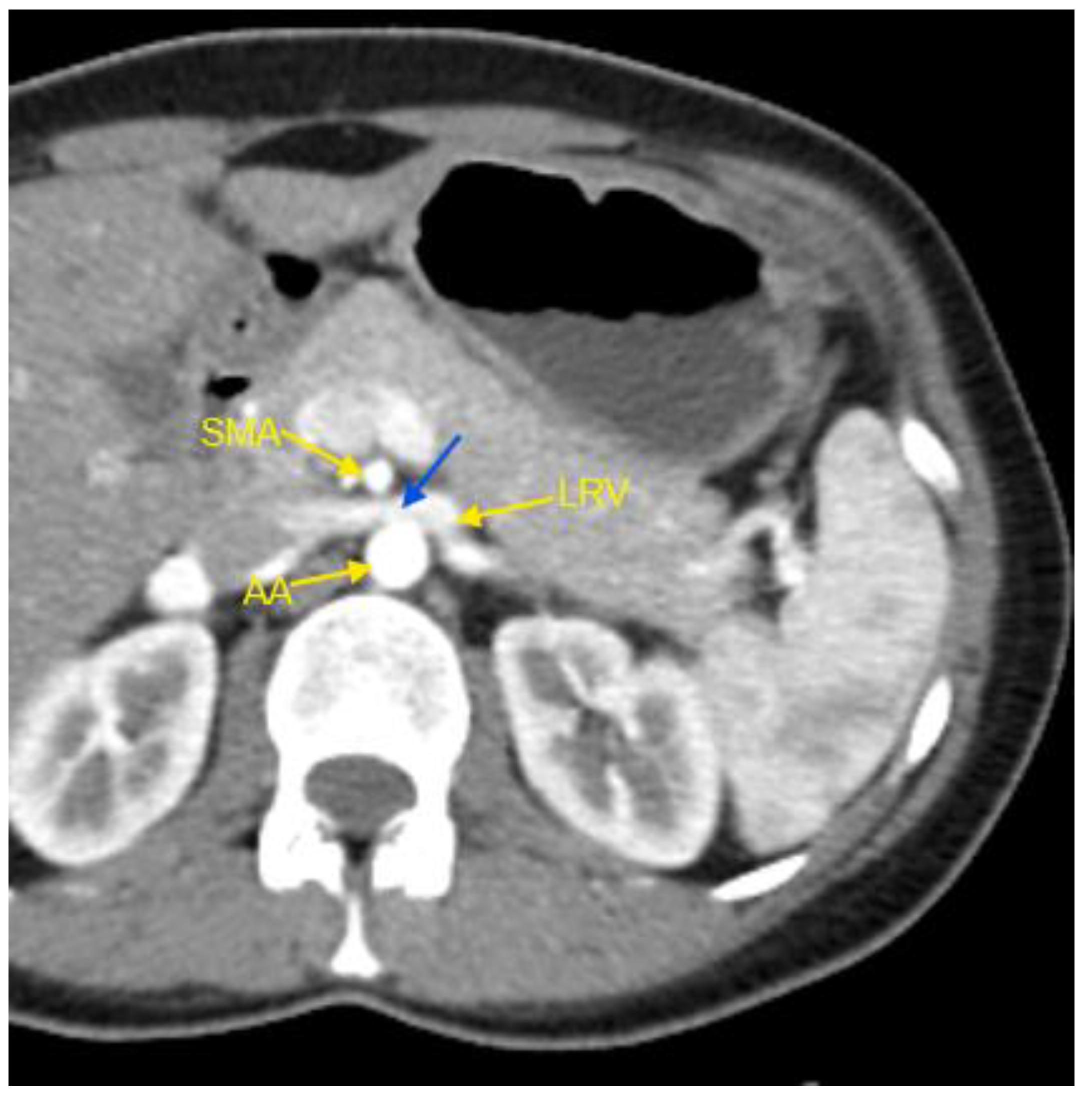

Figure 1 show examples of some renal vascular abnormalities we identified in our study population.

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced CT imaging of a 44-year-old female patient, hospitalized for HTN refractory to treatment, revealed characteristic findings consistent with classic Nutcracker syndrome. The patient had been receiving a triple combination therapy comprising an angiotensin II receptor blocker (valsartan), a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (lercanidipine), and a thiazide-like diuretic (indapamide) at standard doses, with limited efficacy. In the accompanying image, the abdominal aorta, the superior mesenteric artery, and the left renal vein are indicated by yellow arrows. The compressed segment of the left renal vein is highlighted by a blue arrow. AA – abdominal aorta; CT – computed tomography; HTN – arterial hypertension; LVR – left renal vein; SMA – superior mesenteric artery.

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced CT imaging of a 44-year-old female patient, hospitalized for HTN refractory to treatment, revealed characteristic findings consistent with classic Nutcracker syndrome. The patient had been receiving a triple combination therapy comprising an angiotensin II receptor blocker (valsartan), a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (lercanidipine), and a thiazide-like diuretic (indapamide) at standard doses, with limited efficacy. In the accompanying image, the abdominal aorta, the superior mesenteric artery, and the left renal vein are indicated by yellow arrows. The compressed segment of the left renal vein is highlighted by a blue arrow. AA – abdominal aorta; CT – computed tomography; HTN – arterial hypertension; LVR – left renal vein; SMA – superior mesenteric artery.

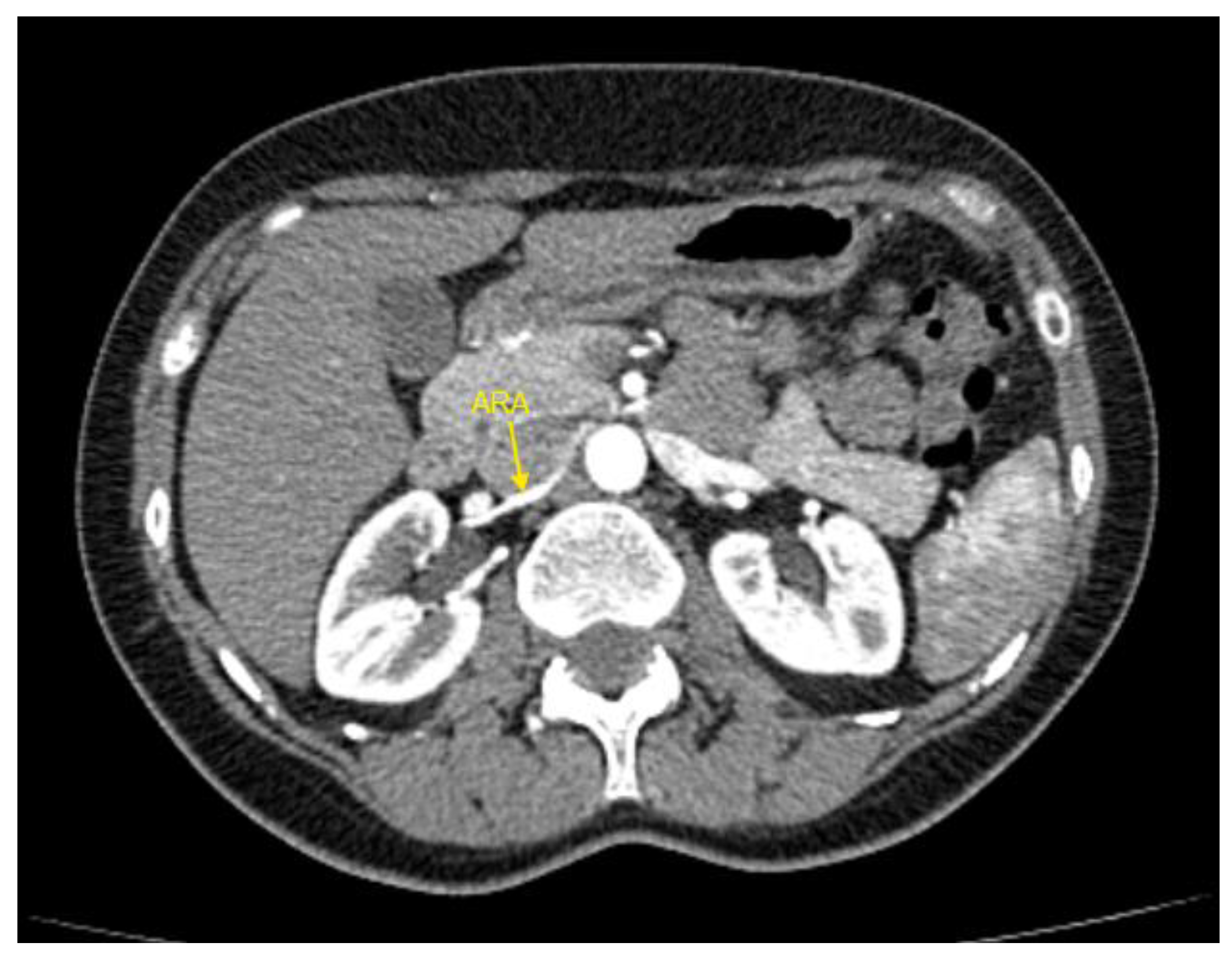

Figure 2.

Contrast-enhanced CT imaging of a 47-year-old female patient revealed an accessory renal artery in the left kidney, indicated by the yellow arrow. The patient was hospitalized for resistant HTN that persisted despite treatment with a combination of four drugs. Her regimen included an angiotensin II receptor antagonist (valsartan), a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (slow-release nifedipine), a beta-blocker (bisoprolol), and a thiazide diuretic (hydrochlorothiazide), all administered at standard doses. ARA – accessory renal artery; CT – computed tomography; HTN – arterial hypertension.

Figure 2.

Contrast-enhanced CT imaging of a 47-year-old female patient revealed an accessory renal artery in the left kidney, indicated by the yellow arrow. The patient was hospitalized for resistant HTN that persisted despite treatment with a combination of four drugs. Her regimen included an angiotensin II receptor antagonist (valsartan), a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (slow-release nifedipine), a beta-blocker (bisoprolol), and a thiazide diuretic (hydrochlorothiazide), all administered at standard doses. ARA – accessory renal artery; CT – computed tomography; HTN – arterial hypertension.

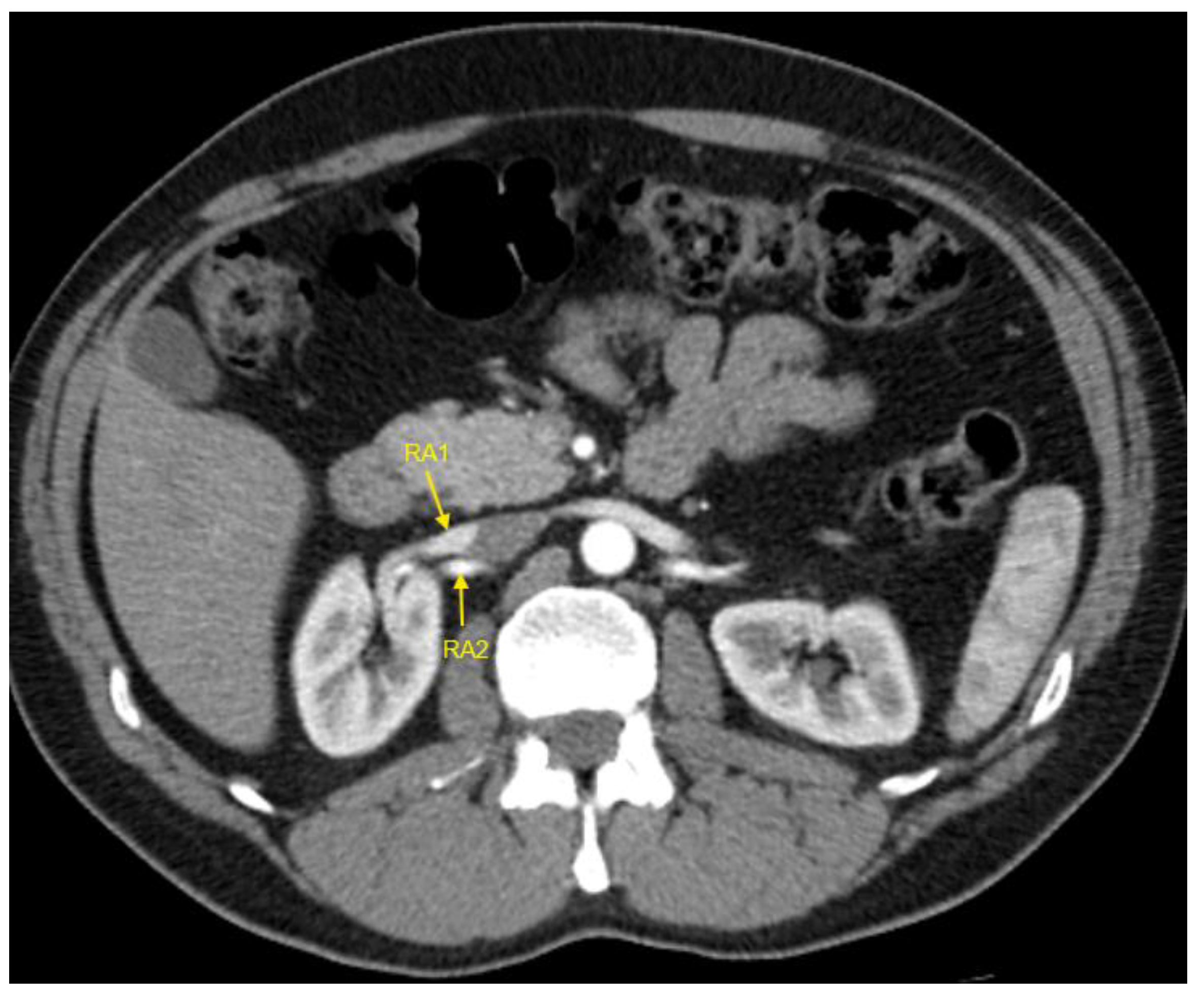

Figure 3.

Contrast-enhanced CT imaging of a 49-year-old female patient demonstrated an accessory renal artery in the right kidney, indicated by the yellow arrow. The patient was referred by her general practitioner to a cardiologist due to HTN resistant to treatment. Her blood pressure remained uncontrolled despite being on a single-pill combination therapy consisting of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (perindopril), a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (amlodipine), and a thiazide-like diuretic (indapamide) at maximal daily doses. ARA – accessory renal artery; CT – computed tomography; HTN – arterial hypertension.

Figure 3.

Contrast-enhanced CT imaging of a 49-year-old female patient demonstrated an accessory renal artery in the right kidney, indicated by the yellow arrow. The patient was referred by her general practitioner to a cardiologist due to HTN resistant to treatment. Her blood pressure remained uncontrolled despite being on a single-pill combination therapy consisting of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (perindopril), a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (amlodipine), and a thiazide-like diuretic (indapamide) at maximal daily doses. ARA – accessory renal artery; CT – computed tomography; HTN – arterial hypertension.

Figure 4.

Contrast-enhanced CT imaging of a 43-year-old male patient showed the presence of two renal arteries in the right kidney, indicated by the yellow arrows. The patient was referred to our clinic due to uncontrolled HTN, which persisted despite treatment with a combination therapy. His regimen included an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ramipril), a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (amlodipine), and a loop diuretic (torasemide), all at standard doses. CT – computed tomography; HTN – arterial hypertension; RA1 – first renal artery; RA2 – second renal artery.

Figure 4.

Contrast-enhanced CT imaging of a 43-year-old male patient showed the presence of two renal arteries in the right kidney, indicated by the yellow arrows. The patient was referred to our clinic due to uncontrolled HTN, which persisted despite treatment with a combination therapy. His regimen included an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ramipril), a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (amlodipine), and a loop diuretic (torasemide), all at standard doses. CT – computed tomography; HTN – arterial hypertension; RA1 – first renal artery; RA2 – second renal artery.

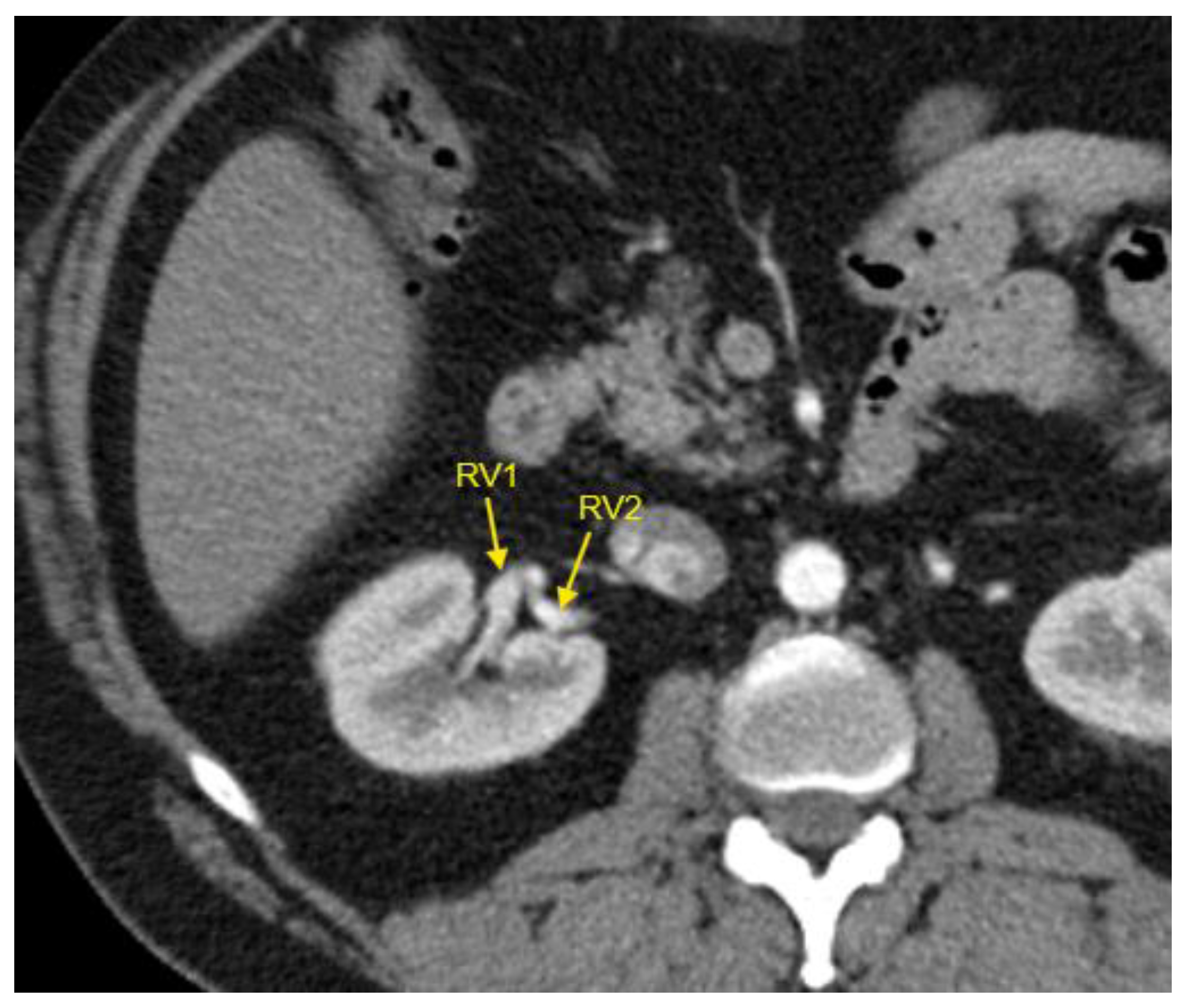

Figure 5.

Contrast-enhanced CT imaging of a 44-year-old male patient revealed two renal veins in the right kidney, indicated by the yellow arrows. This patient exhibited complex congenital renal vascular abnormalities, which also included an accessory renal artery in the right kidney and a retro-aortic left renal vein (not visible in this CT slice). He was referred to our clinic due to uncontrolled HTN despite treatment with a combination of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (lisinopril), a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (lercanidipine), a thiazide diuretic (hydrochlorothiazide), and an alpha-2/imidazoline receptor agonist (moxonidine), all administered at standard doses. CT – computed tomography; HTN – arterial hypertension; RV1 – first renal vein; RV2 – second renal vein.

Figure 5.

Contrast-enhanced CT imaging of a 44-year-old male patient revealed two renal veins in the right kidney, indicated by the yellow arrows. This patient exhibited complex congenital renal vascular abnormalities, which also included an accessory renal artery in the right kidney and a retro-aortic left renal vein (not visible in this CT slice). He was referred to our clinic due to uncontrolled HTN despite treatment with a combination of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (lisinopril), a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (lercanidipine), a thiazide diuretic (hydrochlorothiazide), and an alpha-2/imidazoline receptor agonist (moxonidine), all administered at standard doses. CT – computed tomography; HTN – arterial hypertension; RV1 – first renal vein; RV2 – second renal vein.

3.2. Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Table 2 compares the demographic characteristics, concomitant risk factors, comorbidities, and cardiovascular risk profiles of patients with renal vascular variations and those with normal renal vasculature. Both genders were equally represented in the overall study population and in the two comparison groups (renal vascular variations vs. normal renal vasculature). Patients with renal vascular variations were younger, with a median age difference of 9 years compared to those with normal renal vasculature.

As shown in

Table 2, resistant HTN was significantly more prevalent among patients with anatomical renal vascular variations than among those with normal kidney vasculature. Among participants with renal vascular abnormalities, 76.6% had resistant HTN, while only 23.4% had controlled HTN. Severe HTN (SBP ≥180 mmHg and/or DBP ≥110 mmHg) was also more common in the group with renal vascular variations.

Regarding concomitant risk factors and comorbidities, most were equally represented in both groups, with the notable exception of active smoking, which was three times more common among patients with congenital renal vascular abnormalities.

3.2. Laboratory Investigations

Table 3 displays the basic laboratory parameters of the study participants. Patients with renal vascular variations had higher potassium levels, compared to patients with controlled HTN. For all other laboratory parameters, both groups were comparable.

3.3. BP Measurement

Table 4 presents the office BP and 24-hour ABPM values, and office-measured heart rate (HR) for the study population. Patients with congenital renal vascular anatomic variations had significantly higher BP values in both office and ABPM measurements compared to those with normal renal vasculature. However, no statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups regarding pulse pressure or heart rate.

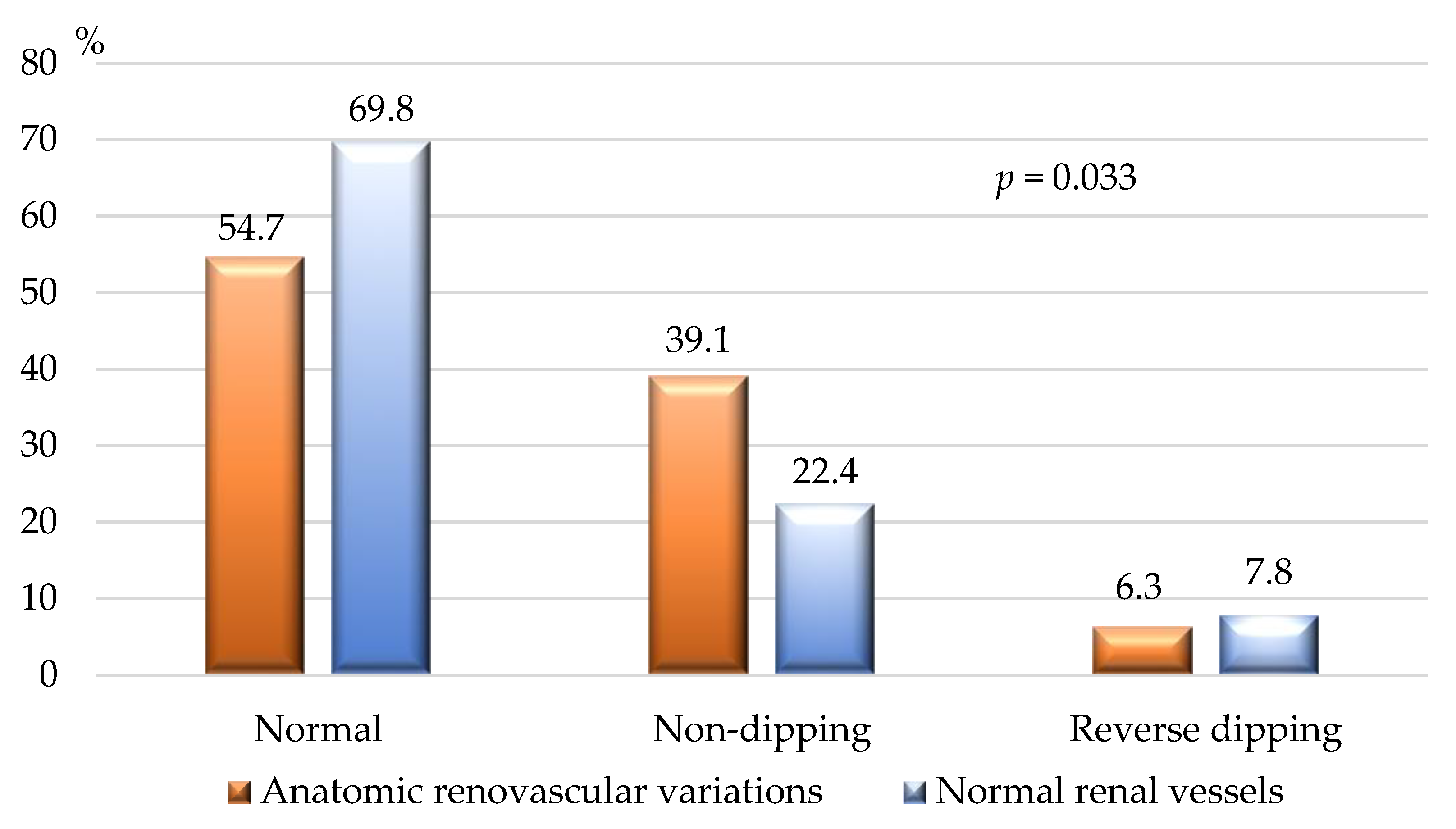

Figure 6 shows the BP dipping status of the study population, assessed by 24-h ABPM. According to our results non-dipping state was significantly more common among patients with congenital renal vascular variations.

3.4. Impact of Congenital Renal Vascular Variations on HTN Control

Table 5 summarizes the results of the logistic regression analysis conducted to assess the association between congenital renal vascular variations and the development of resistant HTN in our study. A significant positive association was identified, with renal vascular variations increasing the overall likelihood of refractory-to-treatment HTN by approximately 4.7-fold.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to assess the association between renal vascular variations and the development of resistant HTN. Congenital abnormalities in renal vasculature are among the most common vascular malformations, yet their clinical significance remains poorly understood [

2,

4,

5,

7,

9]. In our study, renal vascular variations were identified in 25% of participants, with no gender differences in prevalence and this finding aligns with previous reports [

1,

2,

5,

6,

9,

19,

20].

CT imaging in our study demonstrated 19 distinct types of renal vascular abnormalities, with arterial and venous variations being almost equally represented. We did not observe a predominant localization in the right or left kidney. In contrast, García-Barrios et al. reported that arterial variations were more frequent on the right side (64.3%) compared to the left (35.7%), while venous anomalies were equally distributed [

1]. Similar findings have been described by Ugurel et al. and Özkan et al. in two renal CT angiographic studies involving 100 and 855 patients, respectively [

21,

22].

The most common renal vascular abnormalities in our study were unilateral or bilateral accessory renal arteries, the presence of two renal veins in one kidney, and Nutcracker syndrome. At least one accessory artery, with or without additional abnormalities, was present in 19.3% of our patients. Similarly, García-Barrios et al. reported accessory polar renal arteries as the most frequent renovascular variation, observed in 56.3% of cases, although their study involved only 16 dissected kidneys [

1]. Satyapal et al. and Khamanarong et al. found accessory polar renal arteries in 27.7% and 17% of cases, respectively [

3,

7]. Direct comparison between our findings and these studies is challenging due to differences in study populations, as we exclusively enrolled hypertensive patients, whereas the other cohorts were more heterogeneous in clinical characteristics and inclusion/exclusion criteria.

We hypothesize that renal vascular variations may contribute to the development of HTN, a notion supported by other authors, such as Tremblay and Sanghvi [

12,

13]. However, to date, no dedicated clinical investigations provide direct evidence to confirm this hypothesis. Establishing a causal relationship is inherently challenging due to several factors: 1. Hypertensive disease is the most common cardiovascular condition globally, affecting approximately 1.5 billion individuals [

14,

15]; 2. Primary HTN has a heterogeneous pathogenesis, influenced by a multitude of factors including age, genetic predisposition (>1,000 genes are implicated in BP regulation), obesity, increased salt intake and others [

14,

15]; 3. Primary HTN increasingly affects younger populations, and most patients have multiple risk factors for high BP [

14,

15]. According to the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure, normotensive individuals at age 55 have a ~90% lifetime risk of developing HTN [

23]. This statistic underscores the inevitability of HTN in the general population, irrespective of renal vascular variations. Consequently, our study focused on investigating the association between congenital renal vascular abnormalities and resistant HTN—a clinically and practically significant subset of HTN.

In our study, renal vascular variations were significantly more prevalent in patients with resistant HTN (29.2%) compared to those with controlled HTN (9.4%),

p<0.001. Logistic regression analysis demonstrated that congenital renal vascular abnormalities overall increased the odds of developing resistant HTN by more than 4.5-fold, with the most common abnormalities in our study—accessory renal arteries or veins—showing an increase in odds by more than 6-fold. We found no other studies with a similar design and cohort to allow direct comparison. Kasprzycki et al. observed frequent accessory renal arteries in patients with resistant HTN but provided no specific data for comparison [

11]. Current guidelines for the diagnosis and management of HTN acknowledge that certain renal vascular diseases can cause secondary HTN, often resistant to treatment [

14,

15]. However, none of these documents mentions renal vascular variations as potential etiologies for secondary or resistant HTN [

14,

15].

In our cohort, patients with anatomical renal vascular variants and resistant HTN were middle-aged (median age ~54 years) and had no concomitant conditions or diseases that could explain their resistance to standard pharmacological treatment. Good adherence to therapy was an inclusion criterion, and secondary HTN due to other causes was an exclusion criterion. Thus, we propose that renal vascular variations, or at least some of them, may contribute to the development of resistant HTN.

The pathophysiology of resistant HTN involves complex interactions among neurohumoral factors, including increased levels of aldosterone, endothelin-1, vasopressin, and heightened sympathetic activity [

14,

15,

24,

25,

26]. These factors lead to sodium and volume overload, increased peripheral vascular resistance, arterial stiffness, and advanced hypertensive-mediated organ damage, particularly cardiorenal injury [

14,

24,

25,

26]. The precise mechanisms underlying BP elevation in patients with renal vascular variations remain unclear [

10,

12,

14,

15]. We hypothesize that impaired kidney perfusion, whether constant or transient, may activate the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), leading to angiotensin-mediated vasoconstriction and aldosterone-induced sodium and water retention. Increased sympathetic activity is unlikely to play a significant role, as patients with high sympathetic activity typically exhibit resting heart rates ≥80 beats/min, while the median resting heart rate in our cohort was 74 beats/min. Although increased secretion of other vasoconstrictors (e.g., endothelins, vasopressin, others) cannot be excluded, we consider RAAS activation the most probable pathophysiological mechanism.

Our study is a pilot investigation that seeks to address unresolved questions about the clinical significance of anatomical renal vascular variations, particularly their prevalence and association with resistant HTN. Large-scale future studies are necessary to evaluate the impact of different variations on BP control and to elucidate the precise mechanisms contributing to resistant HTN. These insights could improve treatment strategies and BP control in affected patients.

Study Limitations

Our study has several limitations: 1. The sample size and single-center design limit the generalizability of our findings; 2. We assessed the association between renal vascular abnormalities and resistant HTN collectively, without analyzing the impact of specific types beyond accessory arteries and veins; 3. Pathogenic mechanisms underlying resistant HTN in the presence of renal vascular variations were not investigated through laboratory tests or other instrumental methods; 4. Our cohort consisted exclusively of hospitalized hypertensive patients, who may differ from ambulatory populations.

5. Conclusions

Anatomical renal vascular variations were highly prevalent in our hypertensive cohort. The most common abnormalities were unilateral or bilateral accessory renal arteries, double renal veins, and Nutcracker syndrome. These variations were strongly associated with the development of treatment-resistant HTN. Future large-scale studies are needed to evaluate the impact of specific vascular variations on blood pressure control and elucidate their role in resistant HTN pathophysiology, which may lead to improved management strategies for these patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.N.; Methodology, S.N., E.M., M.J and N.R.; Validation, S.N. and N.R.; Formal analysis, S.N. and E.M.; Investigation, S.N., M.J and N.R.; Resources, S.N., M.J and E.M.; Data curation, S.N. and N.R; Writing—original draft preparation— S.N.; Writing— S.N., E.M., M.J. and N.R.; Visualization, S.N., M.J. and E.M; Supervision, N.R.; Project administration, S.N.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval by an Institutional Review Board or Ethics Committee is not required in Bulgaria for this type of research (observational, retrospective, non-interventional study). Our study was registered at

https://www.clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 7 February 2024) with reference number KPVB0001RH.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results are available and can be provided by Stefan Naydenov, MD, PhD; email:

snaydenov@gmail.com.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- García-Barrios, A.; Cisneros-Gimeno, A. I.; Celma-Pitarch, A.; Whyte-Orozco, J. Anatomical Study about the Variations in Renal Vasculature. Folia Morphol 2023, VM/OJS/J/95151. [CrossRef]

- Aristotle, S. Anatomical Study of Variations in the Blood Supply of Kidneys. JCDR 2013. [CrossRef]

- Khamanarong, K.; Prachaney, P.; Utraravichien, A.; Tong-Un, T.; Sripaoraya, K. Anatomy of Renal Arterial Supply. Clinical Anatomy 2004, 17, 334–336. [CrossRef]

- Gulas, E.; Wysiadecki, G.; Szymański, J.; Majos, A.; Stefańczyk, L.; Topol, M.; Polguj, M. Morphological and Clinical Aspects of the Occurrence of Accessory (Multiple) Renal Arteries. aoms 2018, 14, 442–453. [CrossRef]

- Urban, B. A.; Ratner, L. E.; Fishman, E. K. Three-Dimensional Volume-Rendered CT Angiography of the Renal Arteries and Veins: Normal Anatomy, Variants, and Clinical Applications. RadioGraphics 2001, 21, 373–386. [CrossRef]

- Gulas, E.; Wysiadecki, G.; Cecot, T.; Majos, A.; Stefańczyk, L.; Topol, M.; Polguj, M. Accessory (Multiple) Renal Arteries – Differences in Frequency According to Population, Visualizing Techniques and Stage of Morphological Development. Vascular 2016, 24, 531–537. [CrossRef]

- Satyapal, K. S.; Haffejee, A. A.; Singh, B.; Ramsaroop, L.; Robbs, J. V.; Kalideen, J. M. Additional Renal Arteries Incidence and Morphometry. Surg Radiol Anat 2001, 23, 33–38. [CrossRef]

- Aremu, A.; Igbokwe, M.; Olatise, O.; Lawal, A.; Maduadi, K. Anatomical Variations of the Renal Artery: A Computerized Tomographic Angiogram Study in Living Kidney Donors at a Nigerian Kidney Transplant Center. Afr H. Sci. 2021, 21, 1155–1162. [CrossRef]

- Hostiuc, S.; Rusu, M. C.; Negoi, I.; Dorobanțu, B.; Grigoriu, M. Anatomical Variants of Renal Veins: A Meta-Analysis of Prevalence. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 10802. [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela Fuenzalida, J. J.; Vera-Tapia, K.; Urzúa-Márquez, C.; Yáñez-Castillo, J.; Trujillo-Riveros, M.; Koscina, Z.; Orellana-Donoso, M.; Nova-Baeza, P.; Suazo-Santibañez, A.; Sanchis-Gimeno, J.; et al. Anatomical Variants of the Renal Veins and Their Relationship with Morphofunctional Alterations of the Kidney: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prevalence. JCM 2024, 13, 3689. [CrossRef]

- Kasprzycki, K.; Petkow-Dimitrow, P.; Krawczyk-Ożóg, A.; Bartuś, S.; Rajtar-Salwa, R. Anatomic Variations of Renal Arteries as an Important Factor in the Effectiveness of Renal Denervation in Resistant Hypertension. JCDD 2023, 10, 371. [CrossRef]

- Tremblay A., T. A. Renal Artery Variations Clinical Significance and Implications. Int J Anat Var 2024 No. Int J Anat Var, 675–676. [CrossRef]

- Sanghvi, K.; Wang, Y.; Daemen, J.; Mathur, A.; Jain, A.; Dohad, S.; Sapoval, M.; Azizi, M.; Mahfoud, F.; Lurz, P.; et al. Renal Artery Variations in Patients With Mild-to-Moderate Hypertension From the RADIANCE-HTN SOLO Trial. Cardiovascular Revascularization Medicine 2022, 39, 58–65. [CrossRef]

- Mancia, G.; Kreutz, R.; Brunström, M.; Burnier, M.; Grassi, G.; Januszewicz, A.; Muiesan, M. L.; Tsioufis, K.; Agabiti-Rosei, E.; Algharably, E. A. E.; et al. 2023 ESH Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension: Endorsed by the International Society of Hypertension (ISH) and the European Renal Association (ERA). Journal of Hypertension 2023, 41, 1874–2071. [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, J. W.; McCarthy, C. P.; Bruno, R. M.; Brouwers, S.; Canavan, M. D.; Ceconi, C.; Christodorescu, R. M.; Daskalopoulou, S. S.; Ferro, C. J.; Gerdts, E.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Elevated Blood Pressure and Hypertension. European Heart Journal 2024, 45, 3912–4018. [CrossRef]

- Charles, K.; Lewis, M. J.; Montgomery, E.; Reid, M. The 2021 Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration Race-Free Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate Equations in Kidney Disease: Leading the Way in Ending Disparities. Health Equity 2024, 8, 39–45. [CrossRef]

- Visseren, F. L. J.; Mach, F.; Smulders, Y. M.; Carballo, D.; Koskinas, K. C.; Bäck, M.; Benetos, A.; Biffi, A.; Boavida, J.-M.; Capodanno, D.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice. European Heart Journal 2021, 42, 3227–3337. [CrossRef]

- Kurklinsky, A. K.; Rooke, T. W. Nutcracker Phenomenon and Nutcracker Syndrome. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2010, 85, 552–559. [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.; Bhat, S. M.; Venkataramana, V.; Deepthinath, R.; Bolla, S. R. Bilateral Prehilar Multiple Branching of Renal Arteries: A Case Report and Literature Review. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 2006, 4, 345–348.

- Cho, Y.; Yoon, S.-P. Bilateral Inferior Renal Polar Arteries with a High Origin from the Abdominal Aorta. Folia Morphol 2021, 80, 215–218. [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, U.; Oğuzkurt, L.; Tercan, F.; Kizilkiliç, O.; Koç, Z.; Koca, N. Renal Artery Origins and Variations: Angiographic Evaluation of 855 Consecutive Patients. Diagn Interv Radiol 2006, 12, 183–186.

- Ugurel, M. S.; Battal, B.; Bozlar, U.; Nural, M. S.; Tasar, M.; Ors, F.; Saglam, M.; Karademir, I. Anatomical Variations of Hepatic Arterial System, Coeliac Trunk and Renal Arteries: An Analysis with Multidetector CT Angiography. BJR 2010, 83, 661–667. [CrossRef]

- Chobanian, A. V. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood PressureThe JNC 7 Report. JAMA 2003, 289, 2560. [CrossRef]

- Dudenbostel, T.; Acelajado, M. C.; Pisoni, R.; Li, P.; Oparil, S.; Calhoun, D. A. Refractory Hypertension: Evidence of Heightened Sympathetic Activity as a Cause of Antihypertensive Treatment Failure. Hypertension 2015, 66, 126–133. [CrossRef]

- Parasher, A.; Jhamb, R. Resistant Hypertension: A Review. Int J Adv Med 2021, 8, 1433. [CrossRef]

- Cai, A.; Calhoun, D. A. Resistant Hypertension: An Update of Experimental and Clinical Findings. Hypertension 2017, 70, 5–9. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).