1. Introduction

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is characterised by frequent decompensations, leading to increased morbidity and mortality. Clinical practice guidelines for COPD focus on symptom reduction and risk minimisation as the main therapeutic goals [

1,

2]. Achieving clinical control of the disease is the overall objective in the therapeutic approach, requiring adaptation of the therapeutic plan to the patient's evolution.

The concept of COPD control is an evaluative element proposed in the Spanish COPD Guide (GesEPOC), aimed at aiding clinicians in assessing the clinical status of COPD patients during visits [

1]. This evaluation is performed at each visit, assessing clinical impact (degree of dyspnea, rescue medication use, daily physical activity limitations, usual sputum color) and stability (absence of exacerbations in the last 3 months [

1,

3]). Previous studies have assessed the relevance of variables, thresholds, and the number of criteria required to define clinical control [

4,

5,

6]. In addition, studies have validated the concept of control as a predictor of risk. Controlled patients are at a lower risk of future complications [

4]. COPD control status is predictive of future exacerbations and time to the next exacerbation [

7,

8], as well as providing relevant information on health status and survival prognosis providing valuable information on health status [

9] and survival prognosis [

10].

Therefore, measurement of the degree of COPD control is a key tool for clinicians in the management of COPD patients, as it can avoid both unwarranted nihilism and excessive diagnostic-therapeutic intervention. Despite the scientific evidence supporting the assessment of COPD control in the follow-up of patients, it is rarely practised routinely by clinicians. The 2021 EPOCONSUL audit assessing practice in pulmonology practices revealed that the extent of clinical management of COPD was only assessed and reported in one quarter of the audited visits [

11]. These results underline the need to promote clinician assessment by providing a scoring system that quantifies the validated criteria defining the degree of control, as set out in GesEPOC.

Thus, this study aims to develop a score that quantifies the variables involved in defining the degree of clinical control in COPD, providing a quantitative assessment of clinical control. A scoring system that helps to assess the degree of clinical control of COPD and therefore to make decisions in the follow-up and management of patients with COPD.

2. Materials and Methods

Data Source

We conducted a retrospective analysis of the EPOCONSUL audit. Briefly, the EPOCONSUL audit is an observational, non-interventional, cross-sectional, multicenter, nationwide study promoted by the Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR). It is designed to evaluate outpatient care provided to COPD patients in respiratory clinics across Spain based on available medical registry data, with details previously described [

11]. To prevent alterations in usual clinical practice and maintain the blinding of clinical performance evaluation, the medical staff responsible for the outpatient respiratory clinic was not informed about the audit.

Briefly, the recruitment process was intermittent; each month, investigators recruited the clinical records of the first 10 patients diagnosed with COPD who were seen in the outpatient respiratory clinic. These patients were subsequently reevaluated to determine if they met the inclusion/exclusion criteria described in Appendix 1. The information collected was historical for clinical data from the last review visit and concurrent for hospital resource information, as described in Appendix 2. In total, 45 hospitals participated in the 2021 EPOCONSUL audit, and 4,225 clinical records of patients treated in outpatient respiratory clinics were evaluated between April 15, 2021, and January 31, 2022. The participating investigators in EPOCONSUL are listed in Appendix 3.

Participants

We included in this analysis all patients with a COPD clinical control grade estimated and reported by the physician at the visit, who had registered the criteria necessary to define the degree of clinical control validated and established in GesEPOC1.

Development and Validation Cohorts

The included population was randomly divided, with approximately 60% of the sample used to develop the model (development cohort) and 40% used as a validation cohort to validate and assess the model's diagnostic capability.

Predictors and Outcome

Based on the literature review [

12,

13,

14,

15] and in accordance with the criteria necessary to define the degree of clinical control validated and established in GesEPOC1, we included the following variables in our model as predictors of poor clinical control of COPD: the degree of dyspnea according to the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) [

14] scale, the use of rescue medication in the last week, sputum color, the degree of self-reported physical activity at the visit, and the absence of exacerbations in the previous three months requiring systemic corticosteroids and/or antibiotics. We categorized these criteria as predictors of our model based on the thresholds identified and validated in previous studies [

4,

5,

6] (detailed in Appendix 4). The outcome of our analysis was the poor clinical control of COPD, as estimated and reported by the treating physician at the visit.

Statistical analysis

Qualitative variables were summarized as frequency distributions and normally distributed quantitative variables were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD), or as median and interquartile range if they did not fit a normal distribution.

In the development cohort, we calculated the crude Odds Ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each of the five criteria necessary to define the degree of clinical control, as validated and established in GesEPOC, for the outcome of poor clinical control of COPD reported by the treating physician. This was done using univariate logistic analysis. Subsequently, the five criteria were included in a multivariate logistic regression model. The selection of the final set of criteria for the score estimation was performed using different strategies, including automatic selection algorithms (backward and forward) and information criteria (Akaike Information Criterion [AIC], Bayesian Information Criterion [BIC]). The final score was created by assigning points to each criterion by dividing each beta coefficient in the model by the lowest beta coefficient, then rounding to the nearest integer or half-integer. The discrimination capacity of the model and generated score was analyzed by calculating the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC) and its 95% CI. Model and score calibration was assessed with the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, and GiViTi Calibration belts were also constructed [

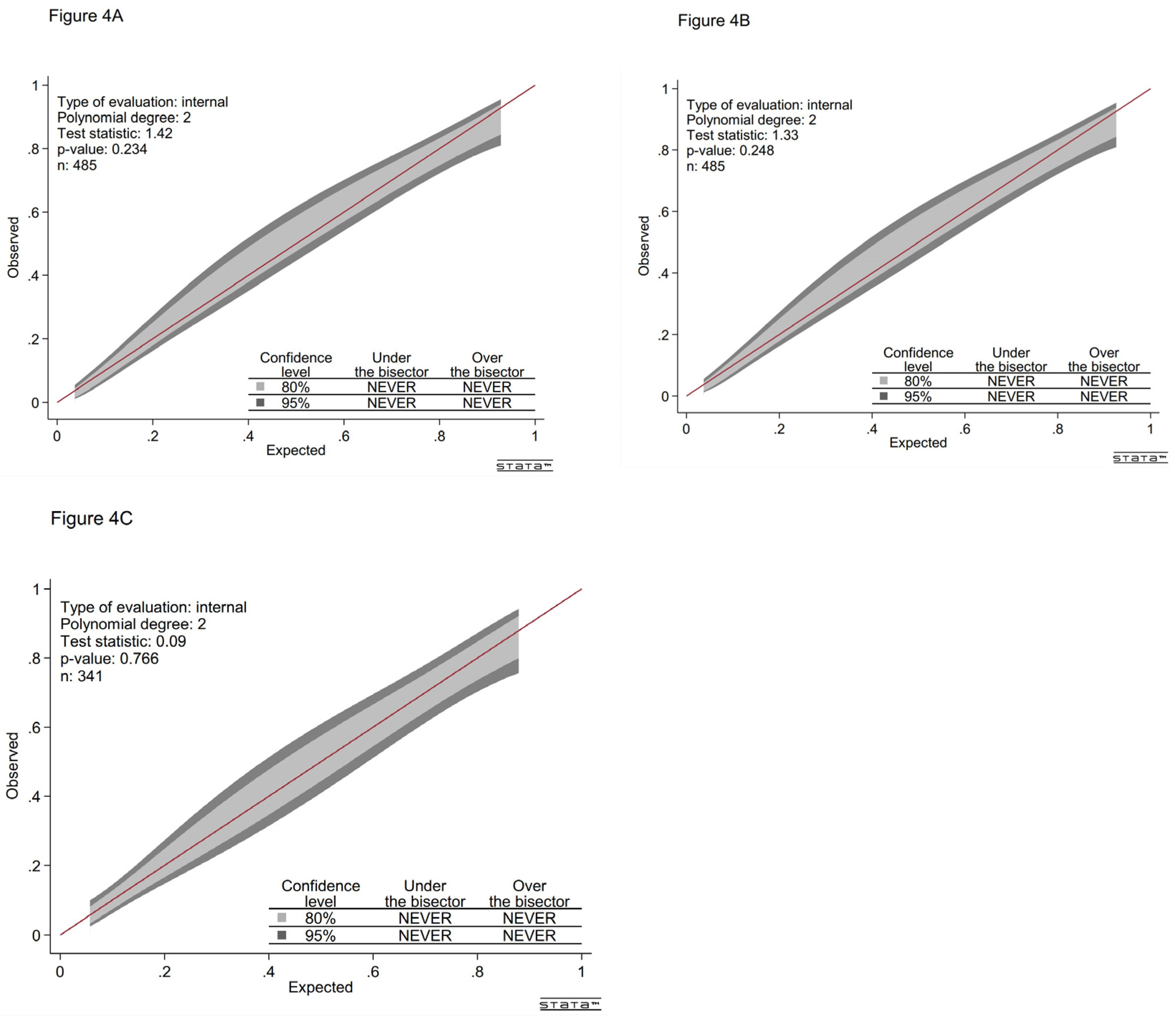

16]. The red line represents perfect calibration between the predicted probability and observed outcomes. The light and dark gray calibration bands represent the 80% and 95% confidence levels for this predictive model, respectively. If the red line falls within the calibration band, the model fits well when the P-value > 0.05.

For validation, the developed score was applied to the validation cohort, and the discrimination and calibration performances were described. Statistical significance was assumed at p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using Stata software version 15 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

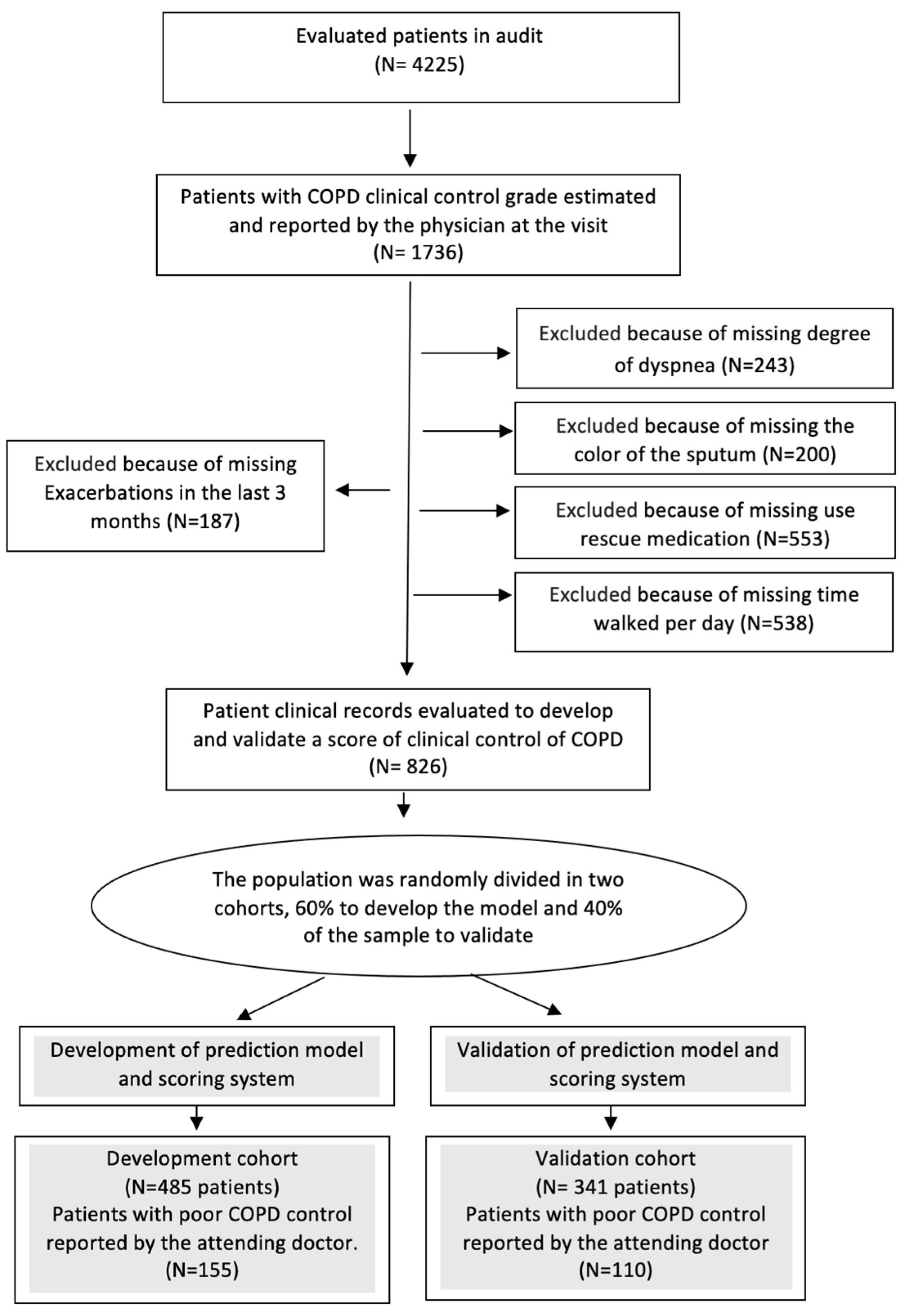

Among the 4225 patients audited in EPOCONSUL, 826 met the COPD clinical control grade reported at the visit and the criteria to define the degree of clinical control (

Figure 1).

The characteristics of the excluded patients in this analysis are described in Appendix 5.

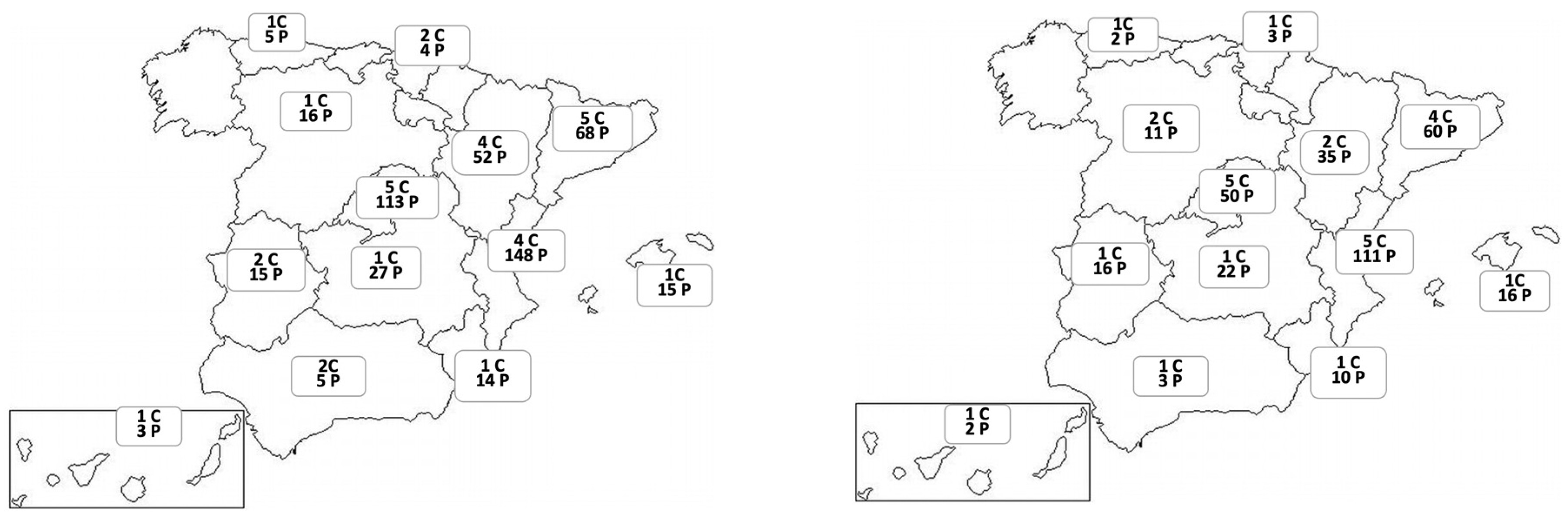

Figure 2 shows the distribution of centers and patients evaluated by regions in the development and validation cohorts.

The development cohort included 485 patients (mean [SD] age, 68.9 [9.4] years; 341 [70.3%] men) and the validation cohort included 341 patients (mean [SD] age, 69.4 [8.8] years; 240 [70.4%] men). Additional patient characteristics and in-hospital data are described in

Table 1. Most participating centers were primarily public university hospitals (development: 337 [69.5%]; validation: 211 [72.8%]). Most patients had moderate to severe obstruction (development: mean [SD] FEV1, 52.7 [17.6] % predicted; validation: mean [SD] FEV1, 52.8 [18.8] % predicted), and nearly half of the patients received inhaled triple therapy (development: 236 [48.8%]; validation: 156 [46.3%]). Poor clinical control of COPD, as reported by the physician at the follow-up visit, was observed in 32% (155) of patients in the development cohort and 32.3% (110) in the validation cohort.

Model Development and Performance

In the development cohort, we conducted an unadjusted analysis of the criteria to define the degree of clinical control in patients with poorly controlled COPD (

Table 2). The sputum color criterion was not retained in the final model to generate the score.

We calculated the β coefficient and OR with 95% CIs using logistic regression analysis (

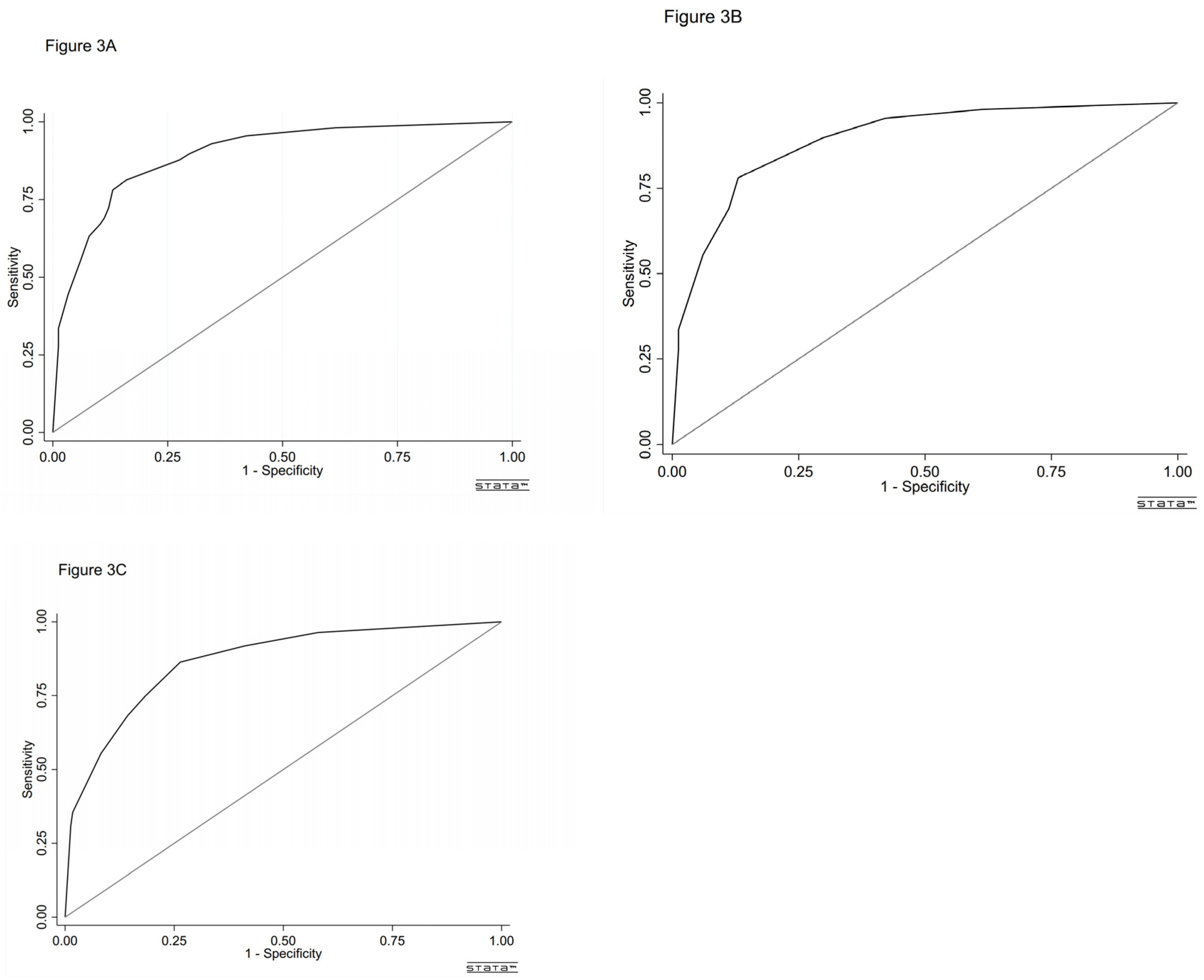

Table 3). The AUC of the model was 0.894 (95% CI, 0.864-0.924, p<0.001) as calculated by the ROC curve (

Figure 3A). The Hosmer-Lemeshow test results (χ²8= 2.286, P = 0.892) indicated that the prediction was well-calibrated to the observations.

Figure 4A shows that the GiViTi calibration curve does not cross the 95% CI area along the 45-degree line (P > 0.05).

Score and Grouping

We developed a simple scoring system based on the β coefficient (

Table 3). The weight assigned to each criterion is described in

Table 3, with a score ranging from 0 to 8, mean (SD) score 2.87 (2.66). The AUC of the score was 0.892 (95% CI, 0.862-0.923, p < 0.001) as calculated by the ROC curve (

Figure 3B). The Hosmer-Lemeshow test results (χ²8 = 4.232, P = 0.516) and the calibration belt (

Figure 4B) demonstrate good calibration.

External Validation of the Model

In the validation cohort, the AUC of the score was 0.867 (95% CI, 0.826-0.908, p<0.001) (

Figure 3C) and the Hosmer-Lemeshow test results (χ²8 = 6.007, P = 0.306) and the calibration belt (

Figure 4C) indicate good calibration.

4. Discussion

In this study, we have developed and validated a score that weights the criteria defining the clinical control of COPD. This scoring system aims to provide a quantitative measure of clinical control, promoting its assessment during patient follow-up and facilitating the interpretation of changes over time and their therapeutic implications for clinicians. The score demonstrated good calibration and discrimination accuracy. It includes four criteria defining COPD control according to GesEPOC [

1]: dyspnea, use of rescue medication, impact on physical activity, and exacerbations. These criteria support the premise that COPD control is a multidimensional construct, comprising two evaluative dimensions: a cross-sectional one—clinical impact, or the repercussion of the disease on the patient, and a longitudinal one—stability, defined as the absence of exacerbations3. The sputum color criterion, which was infrequent in our sample, was not associated with poor COPD control and was therefore not retained in the final model. The score demonstrated good calibration and discrimination power.

The assessment of the degree of control in monitoring COPD is a novel element proposed in GesEPOC [

1] to aid clinicians in decision-making during visits. However, despite existing guidelines, the assessment of clinical control of COPD is not always evaluated in clinical practice [

11], which may lead to a lack of treatment adjustment and COPD patients receiving inadequate treatment with an increased risk of exacerbations and poorer quality of life [

17,

18,

19]. The fact that the degree of COPD control is often not measured or is overestimated by clinicians suggests that current criteria and recommendations alone are insufficient for an adequate assessment of COPD control. Therefore, having a scoring system that provides a quantitative measure of the criteria defining clinical control of COPD will help to assess the degree of control during visits. This will also allow measurement of changes in the degree of control over time, as a result of the therapeutic interventions adopted.

The main strengths of the study are its potential relevance and implications in clinical practice as a tool to facilitate the standardization of the assessment of the degree of control in the follow-up of COPD patients. Firstly, the score may assist clinicians in identifying patients with insufficient clinical control of COPD, thereby aiding decision-making during visits. As a more concrete and comparable measure, the score can boost physicians' confidence in guiding and planning various treatment options, contributing to the appropriate use of medical resources. This is particularly crucial for high-risk populations, allowing for the reassessment of goals, redefinition of necessary therapies, and earlier consideration of other associated factors, such as psychosocial issues. Secondly, this quantitative measure of clinical control is easily translatable into routine clinical practice, as it encompasses validated criteria defining the degree of control and pertinent measurements to be conducted during follow-up visits. Previous studies have demonstrated that increased use of rescue medication [

20] and low levels of physical activity [

21] are linked to poorer health outcomes, including a higher risk of future exacerbations, greater deterioration of lung function, and increased all-cause mortality.

In our scoring, the criterion of rescue inhaler use had the highest weight. However, it is a measure not always reported and recorded during clinical practice visits according to the EPOCONSUL audit results, despite its relative ease of assessment11. This highlights a crucial point that clinicians often limit their assessment to physiological markers and symptoms. Thirdly, this score provides a means of interpreting changes in the degree of clinical control over time. We anticipate that this score could play a significant role in the assessment of COPD control, similar to the Asthma Control Test (ACT) [

22] in asthma, and therefore, could be crucial in evaluating therapeutic interventions in COPD in the future. The scoring system translates qualitative criteria into a quantitative and objective tool, allowing clinicians to more accurately identify patients with insufficient control. This facilitates clinical decision-making, treatment adjustments and monitoring of changes over time.

This study has several limitations that need to be taken into account when assessing the results. Although this model has been validated in the validation cohort, which makes it potentially applicable to similar settings, however our population evaluated are COPD patients treated in respiratory clinics, most patients have moderate to severe obstruction, so studies are needed for future generalisation of the results to other wider populations of COPD patients, in particular those treated in primary care settings. Another limitation to be taken into account is that our model considered as outcome the clinical control of COPD estimated and reported by the specialist during the medical visit. This estimate is based on compliance with treatment goals according to good clinical practice guidelines. This introduces variability, as there is no universal standard, no standardised method to measure control objectively. In addition, although this study included a relatively large sample size, the number of outcomes was limited, which may increase the risk of overfitting the model. Another aspect to consider is the retrospective nature of the study, so its analysis introduces the possibility that unrecognised factors, inaccurate measurements or missing data may lead to measurement biases that may influence the results, even though the recorded data were checked by data managers and members of the EPOCONSUL Audit Committee. Therefore, future prospective research is needed to evaluate this quantitative score as a predictor of COPD outcomes.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we developed and validated an easy-to-use scoring system that quantifies the criteria defining the degree of clinical control of COPD. This system will aid in measuring COPD control and its progression during patient follow-up. Further studies are required to prospectively evaluate our scoring system as a predictor of outcomes in COPD across different settings and to elucidate its clinical utility.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: The inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria;

Table 2: Hospital-related and patient-related variables; Table S3: Participants in 2021 EPOCONSUL study; Table S4: Clinical control of COPD according to GesEPOC criteria; Table S5: Characteristics of patients included and excluded in this analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing—review and editing JLRH, JJSC, MM, BAN, JJLC, and MCR; validation, formal analysis, data curation and writing—original draft preparation MCR and JLRH; resources, supervision, project administration and funding acquisition MCR. MEFF did the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to data analysis, results interpretation, drafting and revising the paper, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study has been promoted and sponsored by the Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was carried out according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Data confidentiality was ensured according to the Law of Data Protection 2018. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Clínico San Carlos (Madrid, Spain; internal code 20/722-E). Additionally, in accordance with current research laws in Spain, the ethics committees at each participating hospital reviewed and approved the study protocol.

Informed Consent Statement

The need for informed consent was waived due to the clinical audit nature of the study, its non-interventional design, data anonymization, and the requirement to evaluate clinical performance blindly.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the centers that participated in EPOCONSUL study and participants investigators (Appendix 4). We thank Chiesi for its support in carrying out the study.

Conflicts of Interest

MCR has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Bial, Chiesi, CSL Behring, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, Sanofi and Grifols, and consulting fees from GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi, Grifols and Bial. JJSC has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, FAES, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini and Novartis, and consulting fees from Bi-al, Chiesi and GSK, and grants from GSK. MM has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Cipla, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, Kamada, Takeda, Zambon, CSL Behring, Specialty Therapeutics, Janssen, Grifols and Novartis, consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Atriva Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, CSL Behring, Inhibrx, Ferrer, Menarini, Mereo Biopharma, Spin Therapeutics, Specialty Therapeutics, ONO Pharma, Palobiofarma SL, Takeda, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Zambon and Grifols and research grants from Grifols. BAN reports grants and personal fees from GSK, personal fees and non-financial support from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees and non-financial support from Chiesi, non-financial support from Laboratorios Menarini, grants, personal fees and non-financial support from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Gilead, personal fees and non-financial support from MSD, personal fees from Laboratorios BIAL, personal fees from Zambon, outside the submitted work; in addition, Dr. Alcázar-Navarrete has a patent P201730724 issued. JLLC has received honoraria for lecturing, scientific advice, participation in clinical studies or writing for publications for: AstraZeneca, Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, CSL Behring, Ferrer, Gebro, GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols, Menarini, Megalabs, Novartis and Rovi. MEFF no conflicts of interest. JLRH has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, CSL Behring, GlaxoSmithKline, Zambon and Grifols, and consulting fees from Bial and Grifols. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COPD |

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| AUC |

Area Under Curve |

| GesEPOC |

Spanish COPD Guide |

References

- Miravitlles M, Calle M, Molina J, Almagro P, Gómez JT, Trigueros JA, et al. Spanish COPD Guidelines (GesEPOC) 2021: Updated Pharmacological treatment of stable COPD. Arch Bronconeumol. 2022;58:69-81. [CrossRef]

- Agustí A, Celli BR, Criner GJ, Halpin D, Anzueto A, Barnes P, et al. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2023 Report: GOLD Executive Summary. Arch Bronconeumol. 2023;59:232-248. [CrossRef]

- Soler-Cataluña JJ, Alcázar-Navarrete B, Miravitlles M. The concept of control in COPD: a new proposal for optimising therapy. Eur Respir J. 2014;44:1072–1075. [CrossRef]

- Soler-Cataluña JJ, Marzo M, Catalán P, Miralles C, Alcazar B, Miravitlles M. Validation of clinical control in COPD as a new tool for optimizing treatment. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:3719-31. [CrossRef]

- Soler-Cataluña JJ, Marzo M, Catalán P, Miralles C, Alcazar B, Miravitlles M, et al. Evaluation criteria for clinical control in a prospective, international, multicenter study of patients with COPD. Respir Med. 2018; 136: 8–14. [CrossRef]

- Nibber A, Chisholm A, Soler-Cataluña JJ, Alcazar B, Price D, Miravitlles M; on Behalf of the Respiratory Effectiveness Group. Validating the concept of COPD control: a real-world cohort study from the United Kingdom. COPD. 2017; 14: 504–12. [CrossRef]

- Miravitlles M, Sliwinski P, Rhee CK, Costello RW, Carter V, Tan JHY, et al; Respiratory Effectiveness Group (REG). Changes in Control Status of COPD Over Time and Their Consequences: A Prospective International Study. Arch Bronconeumol. 2021;57:122-9. [CrossRef]

- Barrecheguren M, Kostikas K, Mezzi K, Shen S, Alcazar B, Soler-Cataluña JJ, et al. COPD clinical control as a predictor of future exacerbations: concept validation in the SPARK study population. Thorax. 2020;75:351-3. [CrossRef]

- Soler-Cataluña JJ, Alcazar B, Marzo M, Pérez J, Miravitlles M. Evaluation of changes in control status in COPD: an opportunity for early intervention. Chest. 2020;157:1138–46. [CrossRef]

- Calle Rubio M, Rodríguez Hermosa JL, de Torres JP, Marín JM, Martínez-González C, Fuster A, et al. COPD Clinical Control: predictors and long-term follow-up of the CHAIN cohort. Respir Res. 2021;22:36. [CrossRef]

- Calle Rubio M, López-Campos JL, Soler-Cataluña JJ, Alcázar Navarrete B, Soriano JB, Rodríguez González-Moro JM, et al; EPOCONSUL Study. Variability in adherence to clinical practice guidelines and recommendations in COPD outpatients: a multi-level, cross-sectional analysis of the EPOCONSUL study. Respir Res. 2017;18:200. [CrossRef]

- Soler-Cataluña JJ, Alcázar-Navarrete B, Miravitlles M. The concept of control of COPD in clinical practice. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:1397–1405. [CrossRef]

- Singh D, Agusti A, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Bourbeau J, Celli BR, et al. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease: the GOLD science committee report 2019. Eur Respir J. 2019;53:1900164. [CrossRef]

- Bestall JC, Paul EA, Garrod R, Garnham R, Jones PW, Wedzicha JA. Usefulness of the medical research council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1999;54:581–6. [CrossRef]

- Ramon MA, Esquinas C, Barrecheguren M, Pleguezuelos E, Molina J, Quintano JA, et al. Self-reported daily walking time in COPD: relationship with relevant clinical and func¬tional characteristics. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:1173–81. [CrossRef]

- Nattino G, Finazzi S, Bertolini G. A new test and graphical tool to assess the goodness of fit of logistic regression models. Stat Med. 2016;35:709-20. [CrossRef]

- Halpin DMG, de Jong HJI, Carter V, Skinner D, Price D. Distribution, temporal stability and appropriateness of therapy of patients with COPD in the UK in relation to GOLD 2019. EClinicalMedicine. 2019;14:32–41. [CrossRef]

- Albitar HAH, Iyer VN. Adherence to Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease guidelines in the real world: current understanding, barriers, and solutions. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2020;26:149–54. [CrossRef]

- Calle Rubio M, Miravitlles M, López-Campos JL, Alcázar Navarrete B, Soler Cataluña JJ, Fuentes Ferrer ME, et al. Inhaled Maintenance Therapy in the Follow-Up of COPD in Outpatient Respiratory Clinics. Factors Related to Inhaled Corticosteroid Use. EPOCONSUL 2021 Audit. Arch Bronconeumol. 2023;59:725-35. [CrossRef]

- Jenkins CR, Postma DS, Anzueto AR, Make BJ, Peterson S, Eriksson G, et al. Reliever salbutamol use as a measure of exacerbation risk in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMC Pulm Med. 2015;15:97. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Aymerich J, Lange P, Benet M, Schnohr P, Antó JM. Regular physical activity modifies smoking-related lung function decline and reduces risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population-based cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:458–63. [CrossRef]

- Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski M, Schatz M, Li JT, Marcus P, et al. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;113:59–65. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).