Submitted:

24 December 2024

Posted:

25 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Positive Psychotherapy as a Tertiary Standard of Protection and Prevention

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

| Group | Pre-test | Process | Post-test |

| G | Q1 | X | Q2 |

| G1: Substance Use Disorder and/or Alcohol Use Disorder G2: Substance Use Disorder and Mood Disorder |

Uskudar Result Awareness Scale, Uskudar Harm Perception Scale |

Individual Therapy, Interaction Group, Psychoeducation program | Uskudar Result Awareness Scale, Uskudar Harm Perception Scale |

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection Tools

2.3.1. Demographic Information Form

2.3.2. Uskudar Result Awareness Scale (USRAS) and Uskudar Harm Perception Scale (USHPS)

2.4. Criteria for Inclusion/Exclusion

2.5. Procedures

2.6. Data Processings and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Conclusion and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Coming to our senses: Healing ourselves and the world through mindfulness; Hachette UK: 2005.

- Kabat-Zinn, J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: Theoretical considerations and preliminary results. General hospital psychiatry 1982, 4, 33-47. [CrossRef]

- Alpay, Ü.; Aydogdu, B.E.; Yorulmaz, O. The Effect of Mindfulness-Based Interventions on Adults' Substance Use: A Systematic Review. Addicta 2018, 5, 736-746. [CrossRef]

- Bowen, S. and A. Marlatt, Surfing the Urge: Brief Mindfulness-Based Intervention for College Student Smokers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 2009. 23(4): p. 666-671.

- Brewer, J.A., et al., Mindfulness Training and Stress Reactivity in Substance Abuse: Results from a Randomized, Controlled Stage I Pilot Study. Substance Abuse, 2009. 30(4): p. 306-317.

- Witkiewitz, K.; Greenfield, B.L.; Bowen, S. Mindfulness-based relapse prevention with racial and ethnic minority women. Addictive Behaviors 2013, 38, 2821–2824.

- Association, A.P. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5; American psychiatric association: Washington, DC, 2013; Vol. 5.

- Güleç, G.; Köşger, F.; Eşsizoğlu, A. Alcohol and Substance Use Disorders in DSM-5 Current Approaches in Psychiatry 2015, 7, 448-460. [CrossRef]

- Carroll, H.; Lustyk, M.K.B. Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention for Substance Use Disorders: Effects on Cardiac Vagal Control and Craving Under Stress. Mindfulness 2018, 9, 488-499. [CrossRef]

- Turner, K. Mindfulness: The Present Moment in Clinical Social Work. Clin Soc Work J 2009, 37, 95-103. [CrossRef]

- Hoppes, K. The application of mindfulness-based cognitive interventions in the treatment of co-occurring addictive and mood disorders. CNS Spectrums 2006, 11, 829–851.

- Coffey, K.A.; Hartman, M. Mechanisms of Action in the Inverse Relationship Between Mindfulness and Psychological Distress. J Evid-Based Integr 2008, 13, 79-91. [CrossRef]

- Roemer, L.; Lee, J.K.; Salters-Pedneault, K.; Erisman, S.M.; Orsillo, S.M.; Mennin, D.S. Mindfulness and Emotion Regulation Difficulties in Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Preliminary Evidence for Independent and Overlapping Contributions. Behav Ther 2009, 40, 142-154, doi:DOI 10.1016/j.beth.2008.04.001.

- Murphy, C.; MacKillop, J. Living in the here and now: interrelationships between impulsivity, mindfulness, and alcohol misuse. Psychopharmacology 2012, 219, 527-536. [CrossRef]

- Bowen, S.; Chawla, N.; Collins, S.E.; Witkiewitz, K.; Hsu, S., Grow, J., ; ... ; Marlatt, A. Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for substance use disorders: A pilot efficacy trial. Substance abuse 2009, 30, 295-305. [CrossRef]

- Mermelstein, L.C.; Garske, J.P. A Brief Mindfulness Intervention for College Student Binge Drinkers: A Pilot Study. Psychol Addict Behav 2015, 29, 259-269. [CrossRef]

- Çatak, P.D.; Ögel, K.F.t.t.v.t.s.K.P., 13, 85–91. Mindfulness based therapies and therapeutic processes. Clinical Psychiatry 2010, 85-91.

- Ögel, K.; Sarp, N.; Gürol, D.T.; Ermağan, E. Investigation of mindfulness and factors affecting mindfulness in addicted and non-addicted individuals. Anatolian Journal of Psychiatry Journal 2014, 15, 282-288.

- Tarhan, N.; Demirsoy, Ç.; Tutgun-Ünal, A. Measuring the Awareness Levels of Individuals with Alcohol and Substance Use Disorders: Tertiary Prevention Standards and Development of Uskudar Result Awareness and Harm Perception Scales. Brain Sci 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Dóra, T.B.; Szalkai, Z. The specifics of services of prevention in the case of addictions. In Proceedings of 9th international conference on management (ICM), Szent István University Gödöllő, Hungary pp. 276-283.

- Derin, G.; Okudan, M.; Aşıcıoğlu, F.; Ankara: Türkiye Klinikleri, -. Family risk factors in alcohol and substance use disorders; Turkey Clinics: Ankara, Turkey, 2021.

- Cai, W.Q.; Wang, Y.J. Family Support and Hope among People with Substance Use Disorder in China: A Moderated Mediation Model. Int J Env Res Pub He 2022, 19. [CrossRef]

- Küçükerdönmez, Ö.; Urhan, M.; Köksal, E.B.v.D.D., 46(2), 147-156. Relationship between appetite, nutritional status and quality of life in individuals with alcohol and substance dependence. Journal of Nutrition and Diet 2018, 46, 147-156. [CrossRef]

- Asan, Ö.; Tıkır, B.; Okay, İ.T.; Göka, E. Sociodemographic and clinical features of patients with alcohol and substance use disorders in a specialized Unit. Journal of Dependence 2015, 16, 1-8.

- Arıkan, Z.; Yasin Genç, D.Ç.E.; Aslan, S.; Parlak, P.İ. Stigmatization of the patients and their relatives in alcohol and other substance dependencies. Journal of Dependence 2004, 52-56.

- Akbaş, G.E.; Mutlu, E. Addiction and treatment experiences of people undergoing substance abuse treatment. Community and Social Work 2016, 27, 101-122.

- Witkiewitz, K.; Greenfield, B.L.; Bowen, S. Mindfulness-based relapse prevention with racial and ethnic minority women. Addictive Behaviors 2013, 38, 2821-2824. [CrossRef]

- Saatçioğlu, Ö.; Evren, E.C.; Çakmak, D. Evaluation of cases with alcohol and substance abuse who were hospitalised between 1998-2002. Journal of Addiction 2003, 109-117.

- Yılmaz, A.; Can, Y.; Bozkurt, M.; Evren, C. Remission and relapse in alcohol and substance addiction. Current Approaches in Psychiatry 2014, 6, 243-256. [CrossRef]

- Evren, C.; Durkaya, M.; Dalbudak, E.; Çelik, S.; Çetin, R.; Çakmak, D. Factors associated with relapse in male alcohol abusers: A 12-month follow-up study. Düşünen Adam Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences 2010, 92-99.

- Gordon, A.J.; Zrull, M. Social Networks and Recovery - One Year after Inpatient Treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat 1991, 8, 143-152, doi:Doi 10.1016/0740-5472(91)90005-U.

- Walton, M.A.; Castro, F.G.; Barrington, E.H. The role of attributions in abstinence, lapse, and relapse following substance abuse treatment. Addict Behav. 1994, 19, 319-331.

- Irvin, J.E.; Bowers, C.A.; Dunn, M.E.; Wang, M.C. Efficacy of relapse prevention: A meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psych 1999, 67, 563-570, doi:Doi 10.1037/0022-006x.67.4.563.

- Tarhan, N. Positive psychology and psychotherapy in addiction. In Addiction diagnosis and treatment basic book, Dilbaz, N., Göğcegöz, I., Noyan, C.O., Kazan Kızılkurt, Ö., Eds. Nobel Medical Bookstores: Turkey, 2021; p. 419.

- Seligman, M.E.; Peterson, C. Positive clinical psychology. In A psychology of human strengths: Fundamental questions and future directions for a positive psychology Aspinwall, L.G., Staudinger, U.M., Eds. American Psychological Association: 2003; pp. 305–317.

- Donaldson, S.I.; Dollwet, M.; Rao, M.A. Happiness, excellence, and optimal human functioning revisited: Examining the peer-reviewed literature linked to positive psychology. J Posit Psychol 2015, 10, 185-195. [CrossRef]

- Kern, M.L.; Williams, P.; Spong, C.; Colla, R.; Sharma, K.; Downie, A.; Taylor, J.A.; Sharp, S.; Siokou, C.; Oades, L.G. Systems informed positive psychology. J Posit Psychol 2020, 15, 705-715. [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E. Positive psychology: A personal history. Annual review of clinical psychology 2019, 15, 1-23.

- Seligman, M.E. Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being; Simon and Schuster: 2011.

- Carreno, D.F.; Pérez-Escobar, J.A. Addiction in existential positive psychology (EPP, PP2.0): from a critique of the brain disease model towards a meaning-centered approach. Couns Psychol Q 2019, 32, 415-435. [CrossRef]

- Karasar, N. Scientific research method: concepts, principles, techniques; Nobel Publishing: Turkey, 2016.

- Groeneveld, R.A.; Meeden, G. Measuring Skewness and Kurtosis. The Statistician 1984, 33, 391-399.

- Hopkins, K.D.; Weeks, D.L. Tests for normality and measures of skewness and kurtosis: Their place in research reporting. Educational and Psychological Measurement 1990, 50, 717-729.

- Moors, J.J.A. The Meaning of Kurtosis - Darlington Reexamined. Am Stat 1986, 40, 283-284, doi:Doi 10.2307/2684603.

- Tarter, R.E.; Cochran, G.; Reynolds, M. Prevention of opioid addiction. Commonwealth 2018, 20.

- Vanyukov, M.M.; Kirisci, L.; Moss, L.; Tarter, R.E.; Reynolds, M.D.; Maher, B.S.; ...; Clark, D.B. Measurement of the risk for substance use disorders: phenotypic and genetic analysis of an index of common liability. Behavior genetics 2009, 39, 233-244.

- Kirisci, L.; Tarter, R.; Mezzich, A.; Ridenour, T.; Reynolds, M.; Vanyukov, M. Prediction of Cannabis Use Disorder between Boyhood and Young Adulthood: Clarifying the Phenotype and Environtype. Am J Addiction 2009, 18, 36-47. [CrossRef]

- Kirisci, L.; Tarter, R.E. Psychometric validation of a multidimensional schema of substance use topology: Discrimination of high and low risk youth and prediction of substance use disorder. J Child Adoles Subst 2001, 10, 23-33. [CrossRef]

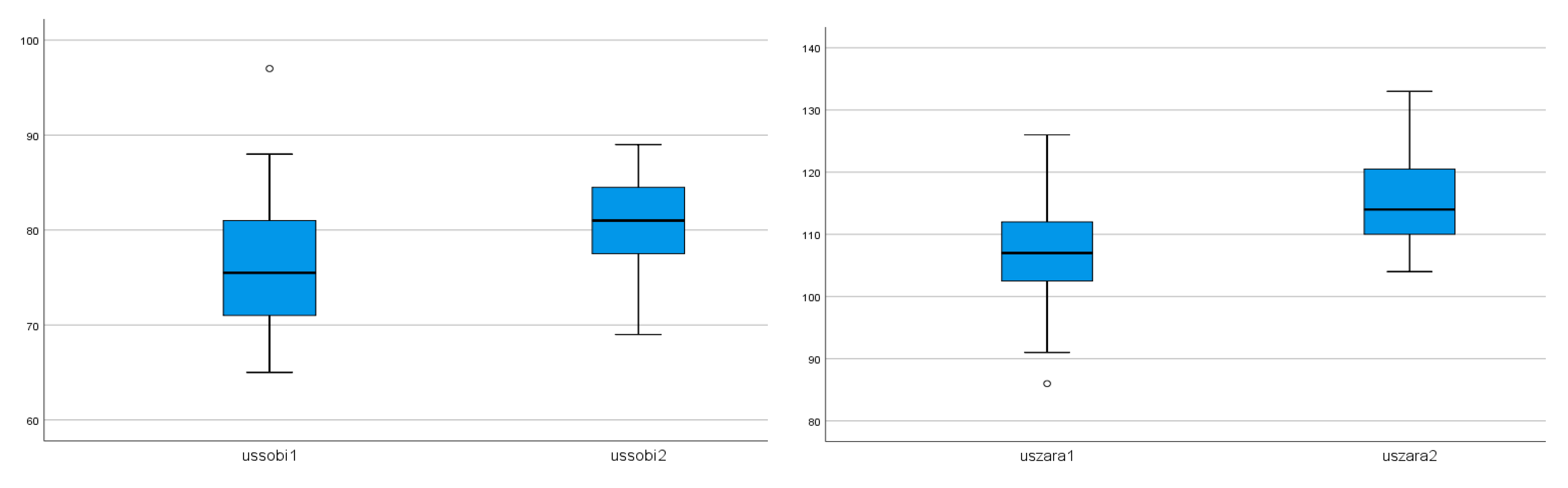

| Groups | USRAS1 | Sd1 | USRAS2 | Sd2 | USHPS1 | Sd1 | USHPS2 | Sd2 |

| G1: Substance Use Disorder and/or Alcohol Use Disorder (n=30) |

75,70 | 6,60 | 79,86 | 5,20 | 107,00 | 8,36 | 116,30 | 6,33 |

| G2: Substance Use Disorder and Mood Disorder (n=14) | 76,50 | 7,14 | 82,28 | 4,44 | 107,57 | 8,26 | 113,35 | 7,01 |

| Male (n=35) | 75,68 | 6,70 | 80,14 | 5,26 | 107,22 | 8,67 | 116,22 | 6,90 |

| Female (n=9) | 77,00 | 7,01 | 82,55 | 3,77 | 107,00 | 6,72 | 112,00 | 4,12 |

| Total (n=44) | 75,95 | 6,70 | 80,63 | 5,05 | 107,18 | 8,24 | 115,36 | 6,61 |

| Groups* | X | Sd | t | df | p |

| Group1 USRAS1 (n=30) | 75,70 | 6,60 | 62,74 | 29 | ,00a |

| Group1 USRAS2 (n=30) | 79,86 | 5,20 | 84,05 | 29 | |

| Group1 USHPS1 (n=30) | 107,00 | 8,36 | 70,04 | 29 | ,00b |

| Group1 USHPS2 (n=30) | 116,30 | 6,33 | 100,61 | 29 | |

| Group2 USRAS1 (n=14) | 76,50 | 7,14 | 40,06 | 13 | ,00c |

| Group2 USRAS2 (n=14) | 82,28 | 4,44 | 69,26 | 13 | |

| Group2 USHPS1 (n=14) | 107,57 | 8,26 | 48,71 | 13 | ,00d |

| Group2 USHPS2 (n=14) | 113,35 | 7,01 | 60,48 | 13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).