Submitted:

20 December 2024

Posted:

25 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction and Background

- i)

- To describe the pathogens studied using MBA for serosurveillance.

- ii)

-

To describe the operational implementation of using MBA for serosurveillance:

- Sampling design to determine target population,

- How the samples were collected,

- MBA antibody targets, and

- Laboratories where MBA was conducted.

- iii)

-

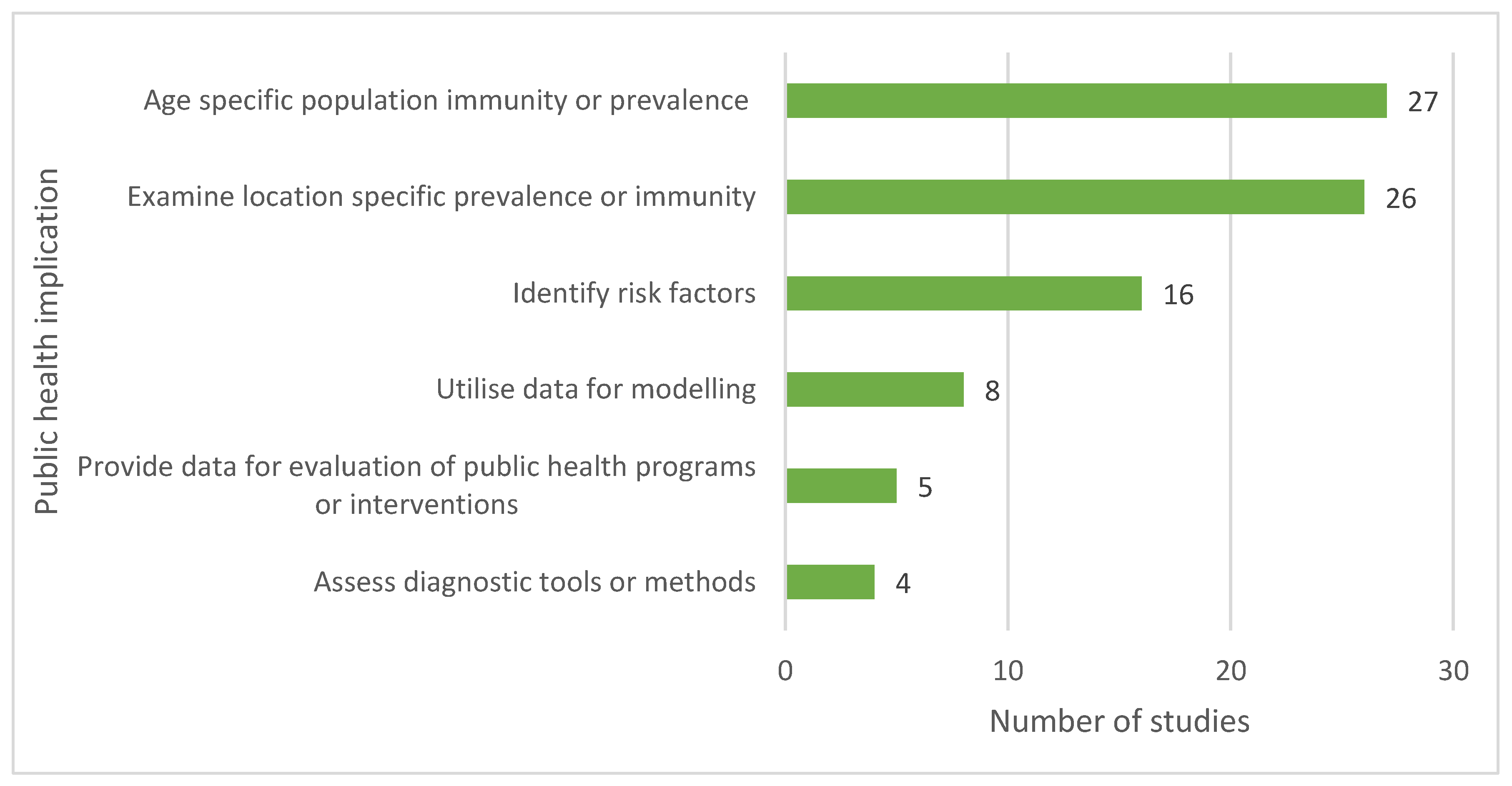

To describe the geographical distribution of studies and types of applications of MBA for serosurveillance:

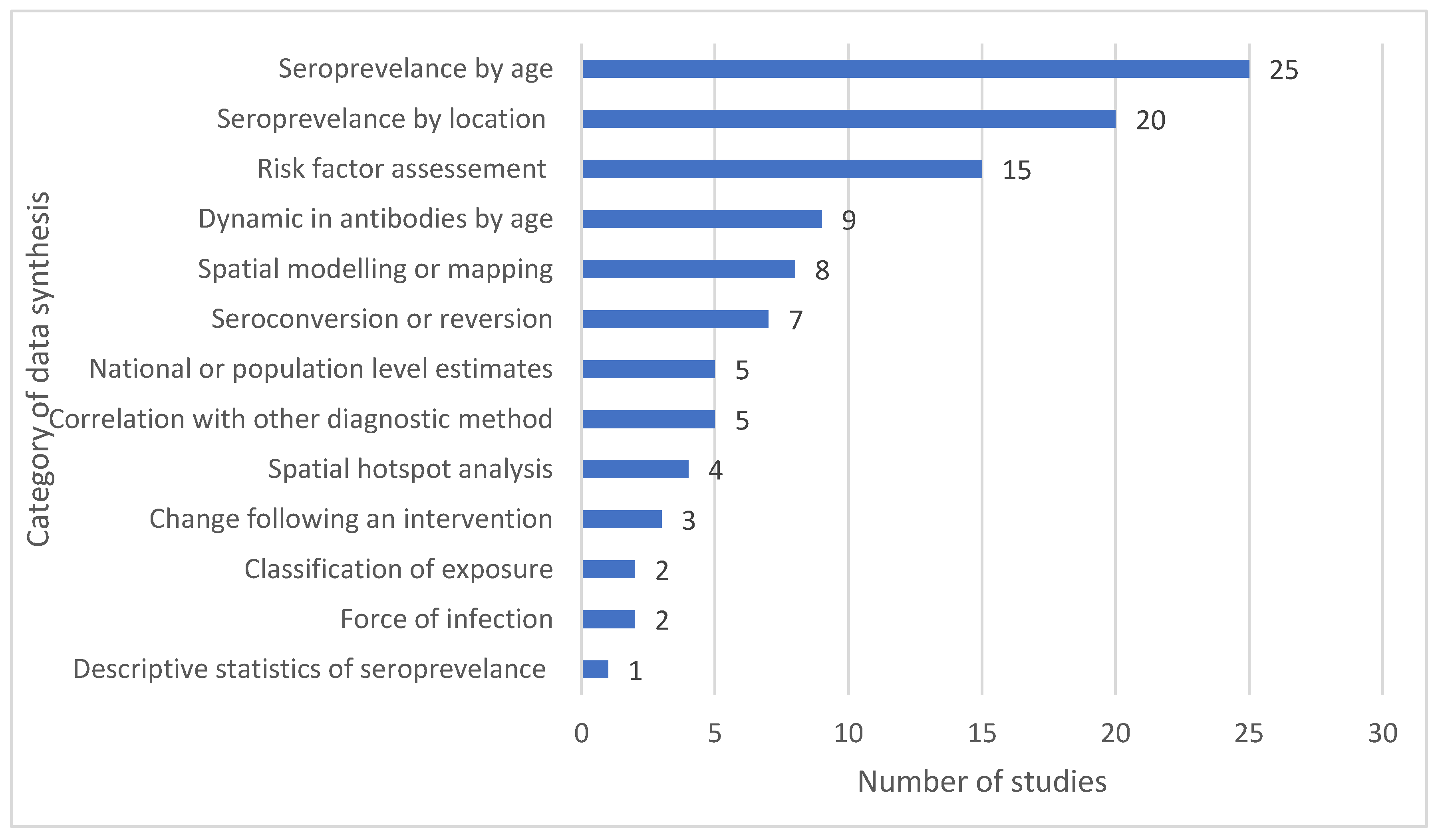

- Synthesis of data,

- Seroprevalence findings, and

- Public health implications.

Methods

- i)

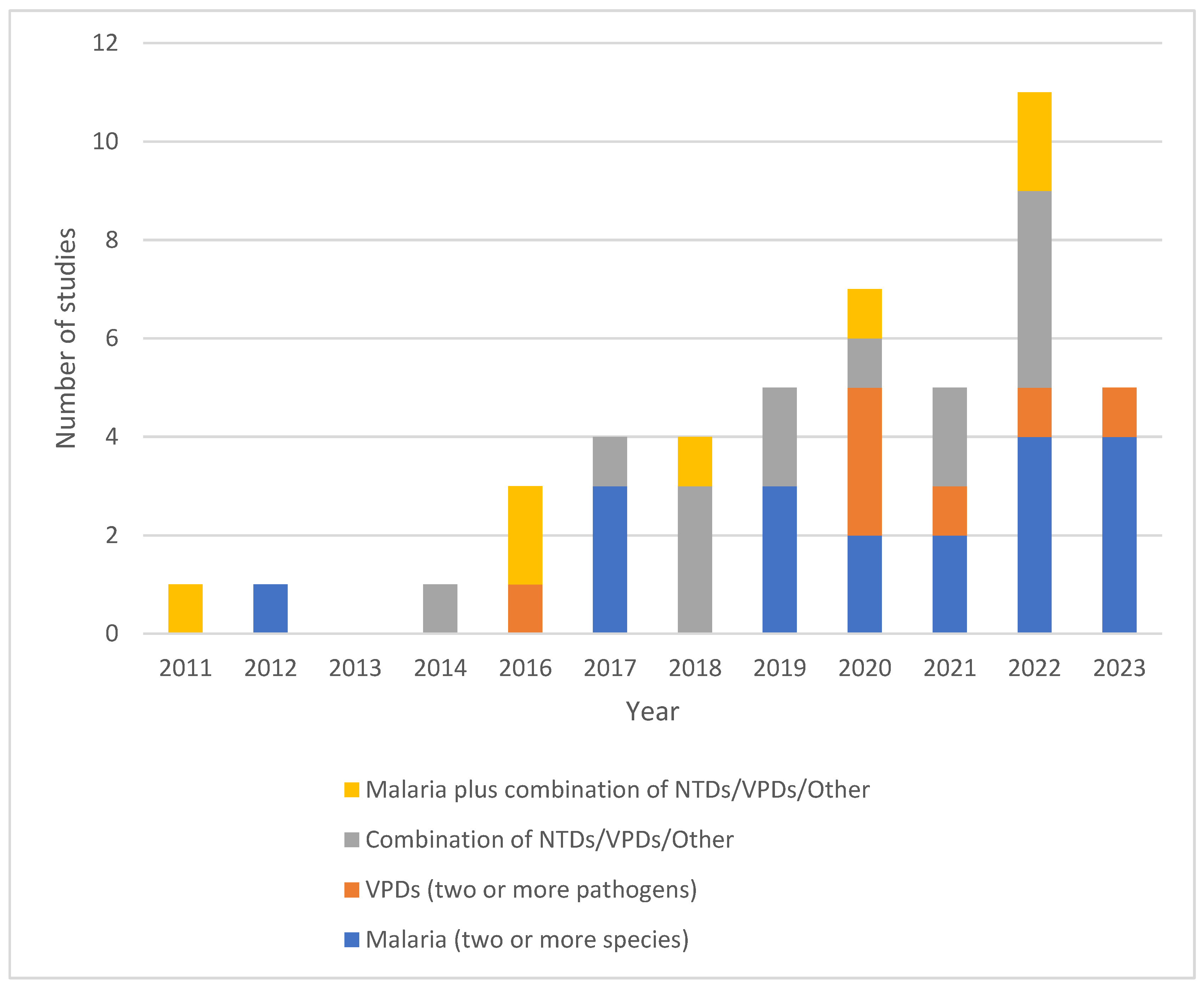

- Malaria (two or more species)

- ii)

- VPDs (two or more pathogens)

- iii)

- Combination of NTDs/VPDs/Other

- iv)

- Malaria plus combination of NTDs/VPDs/Other

Results

| ID | WHO Region (Countries) | Operational details of sample collection with sampling method/s (references) – Data source | Location of lab analysis (Sample type) |

| Malaria (two or more species) | |||

| 4 | Africa (Ethiopia) | Malaria Indicator Survey (2015) – A nationally representative cross-sectional survey using a two-stage cluster approach for selection of enumeration areas and random sampling for household selection targeting individuals of all ages. [62] | CDC, USA (DBS) |

| 7 | Western Pacific (Lao) | Cross-sectional household (conducted in 2016) survey targeting four districts Northern Lao with known malaria hotspots. A stratified two-stage cluster sampling design chose 25 survey clusters based on proportional-to-population size then households were selected randomly. People aged over 18 months within each household were invited to participate. [63] | LSHTM, UK (DBS) |

| 8 | Western Pacific (Malaysian Borneo) | Environmentally stratified, population based cross-sectional study (conducted in 2015) aimed to understand the transmission of malaria in people aged over 3 years, in northern Sabah as part of the MONKEYBAR project. A non-self-weighting two-stage sampling design whereby villages were selected based on proportion of forest cover and 20 households with each village were randomly selected. [64] | LSHTM, UK (Both) |

| 15 | Africa (Ethiopia) | Convenience sampling of individuals (5+ years) within a community-based onchocerciasis survey in three villages (Arengama 1, Arangama 2 and Konche) of southwest Addis Ababa. Participants were selected through convenience sampling in 2016. | CDC, USA (DBS) |

| 18 | Africa (Nigeria) | Nigeria HIV/AIDS Indicator and Impact Survey (NAIIS) - Conducted in 2018, this was a nationally representative cross-sectional survey using a two-stage cluster approach for selection of enumeration areas and random sampling for household selection targeting individuals of all ages. [65] | CDC, Nigeria (DBS) |

| 19 | Africa (Ethiopia) | Primary study: Cross-sectional serosurvey conducted in 2018 in two areas of southwestern Ethiopia (Arjo-Didessa and Gambella) with contrasting malaria transmission intensities. Using household clustering, individuals aged over 15 years were invited to participate. | Not reported (DBS) |

| 20 | Africa (Republic of Djibouti) | Primary study: Cross-sectional household-based serosurvey conducted in 2002 investigating the prevalence of malaria infections in adults aged 15-54 years in the Republic of Djibouti. Cluster sampling was used to select households whereby anonymized samples were collected from adults aged 15 - 54 years. | Not reported (Serum) |

| 22 | Africa (Cote d’Ivoire) | In 2010, 2012 and 2013, patients presenting to Abobo healthcare facility with symptomatic malaria were invited to join the study. In 2011, due to the Civil War, young asymptomatic school children (6 - 15 years) were recruited in a transversal survey (n=207) in addition to 175 symptomatic patients presenting to healthcare. [66] | Not reported (Serum) |

| 24 | Americas (Suriname) | Primary study: A cross-sectional study of adults (>18 years) conducted in three regions of Suriname (Stoelmanseiland and surroundings (Gakaba, Apoema and Jamaica), Benzdorp) between 2017 – 2018. Stoelmanseiland: All villagers who could be reached within a 4-day enrolment period. Benzdorp: Participants were recruited during active case detection conducted by the National Malaria Programme. | CDC, USA (DBS) |

| 25 | Africa (Ethiopia) | Malaria Indicator Survey (2015) – A nationally representative cross-sectional survey using a two-stage cluster approach for selection of enumeration areas and random sampling for household selection targeting individuals of all ages. [62] | CDC, USA (DBS) |

| 26 | South-East Asia (Bangladesh) | Conducted in 2018, this vaccine coverage and vaccine serosurvey was conducted in two areas of Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh (Nayapara and makeshift settlement camps (MSs)) alongside an Emergency Nutrition Assessment that was concurrently conducted by the Nutrition Sector (led by Action Against Hunger). This assessment uses the Standardized Monitoring and Assessment for Relief and Transitions (SMART) Methodology. In Nayapara, households were selected using simple random sampling whereby in MSs, a cluster sampling design was used.[67] | CDC, USA (DBS) |

| 27 | Western Pacific (Philippines) | A rolling cross-sectional survey was conducted in three municipalities in three provinces in the Philippines. Sites were selected based on the 2014 Philippines’ National Malaria Program operational definition of malaria-endemic provinces (high endemicity - Rizal, Palawan; sporadic local cases - Abra de Ilog, Occidental Mindoro; malaria-free Morong, Bataan). Participants were recruited from health-care facilities between 2016 – 2018. [68] | University of Philippines(DBS) |

| 28 | Africa (Ethiopia and Costa Rica) | Ethiopia: Ethiopia Malaria Indicator Survey 2015 [62] Costa Rica: A household based serosurvey conducted 2015 in the Costa Rican canton of Matina (2015). This location was selected as one of the last locations in the country where malaria cases were present. Ethiopia (n= 7,077) was selected as the country is co-endemic for both P. falciparum and P. vivax, and Costa Rica (n=851) was selected as a representative low, mono-species Plasmodium endemic region. | CDC – USA (DBS) |

| 32 | Americas (Brazil) | Biorepository at the Institute of Biomedical Sciences of the University of São Paulo containing samples from three studies: Curado, et al. (1997): Cross-sectional household-based study of adults (15+ years) in an area 5-10km of a malaria case in two areas in Brazil with few sporadic cases of malaria between 1992-1994. Silva-Nunes, et al. (2006): Cross-sectional study describing baseline malaria and arbovirus prevalence in rural Amazonia in 2004. All households within the study area were invited to participate. Medeiros, et al. (2013): Cross-sectional study examining symptomatic and asymptomatic malaria cases in four localities on the riverbanks of the Madeira River. People aged over 1 year were eligible to participate. [69,70,71] | University of São Paulo, Brazil (Both) |

| 36 | Americas (Haiti) | Transmission assessment survey (TAS) for LF: Conducted yearly between 2014 – 2016, implementation units are chosen if they have completed at least five rounds of annual MDA with a coverage rate ≥ 65% of the entire population of the implementation unit. The target population for TAS are children aged 6 – 7 years and can be conducted as a school-based or community-based design. [72,73] | CDC, USA (DBS) |

| 37 | Africa (Senegal) | Yearly cross-sectional sampling (between 2002-2013) of febrile individuals (all ages) presenting to free medical clinics in two rural villages (Dielmo and Ndiop) in Senegal. [74,75] | Not reported (Serum) |

| 41 | Africa (Mali) | The primary study was a matched-control trial to assess the effectiveness of a school-based WASH program (2014) in southern Mali. Serology samples were collected from school children (4 - 17 years) as part of a cross-sectional study nestled within the longitudinal impact evaluation (NCT01787058). [76] | CDC, USA (DBS) |

| 42 | Americas (Haiti) | A 2017 serosurvey (ages >6 years) for malaria conducted in Haiti. Sampling method not defined. | CDC, USA (Both) |

| 44 | Americas (Haiti) | Based in Grand’Anse, in the southwest of Haiti, a prospective healthcare facility-based case-control study was conducted in 2018. Cases (>6 months) were defined as a febrile individual with positive RDT results for malaria. Controls were RDT negative individuals matched via age and gender. Follow up was conducted as a household visit to collect further information. [77] | National Laboratory, Port-au-Prince (DBS) |

| VPDs (two or more pathogens) | |||

| 5 | Europe (Belgium) | Primary study: A cross-sectional study examining vaccination and immunity to vaccine preventable diseases in adult (>18 years) at-risk patients (current diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, heart failure, chronic pulmonary obstructive disease, chronic kidney disease, HIV or solid organ transplant) attending outpatient clinics at the University Hospitals of Leuven. Active recruitment to the study was conducted between 2014 and 2016. | Scientific Institute, Belgium (Not stated) |

| 6 | Western Pacific (Solomon Islands) | Primary study: Conducted in 2016, a national cross-sectional school-based survey cluster survey of children (6 - 7 years) in the Solomon Islands. Schools (n=80) were systematically chosen proportional to estimated population size and all children eligible were invited to participate. | CDC, USA (DBS) |

| 9 | Europe (Belgium) | Randomly selected left-over serum samples (n=670) collected in 2012 by six laboratories in three regions of Belgium (Flanders, Wallonia and Brussels Capital Region). Samples collected were originally tested (n=1500) for pertussis prior to use within this study. All samples were collected from “healthy” asymptomatic (for pertussis) adults aged 20 – 30 years. [78] | Scientific Institute, Belgium (Serum) |

| 14 | South-East Asia (Bangladesh) | Emergency Nutrition Assessment (2018) - This survey used data and samples from the study described by Lu, et al. (2020). In brief, a survey was conducted in two areas of Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh (Nayapara and makeshift settlement camps (MSs)) alongside an Emergency Nutrition Assessment. In Nayapara, households were selected using simple random sampling whereby in MSs, a cluster sampling design was used. [67] | CDC, USA (DBS) |

| 21 | Europe (Ukraine) | Conducted in 2017, this cross-sectional serosurvey aimed to investigate immunity to polioviruses following an outbreak of cVDPV1. This survey targeted four areas (Zakarpattya province in the west, Sumy province in the east, Odessa province in the south, and the capital, Kyiv City) with problems related to cVDPVs and/or challenges with routine immunizations. Children (2 - 10 years) were chosen using one-stage cluster sampling in the three provinces and stratified simple random sampling based on registration with healthcare facilities. [79,80,81] | CDC, USA (Serum) |

| 31 | Americas (Haiti) | Nationally representative household-based survey (conducted in 2017) designed to estimate chronic hepatitis B virus infection and immunity to diphtheria, tetanus, measles, and rubella in children aged 5-7 years. Sampling was done by a two-stage cluster sampling method whereby enumeration areas were selected proportional to size and household were selected at random. [82] | CDC, USA (DBS) |

| 42 | Africa (Nigeria) | 2018 Nigeria HIV/AIDS Indicator and Impact Survey - A nationally representative cross-sectional survey using a two-stage cluster approach for selection of enumeration areas and random sampling for household selection targeting individuals of all ages. [65] | Not reported (DBS) |

| Combination of NTDs/VPDs/Other | |||

| 1 | Africa (Ethiopia) | A cluster-randomized trial (conducted in 2015) designed to determine the effectiveness of a comprehensive WASH package for ocular C. trachomatis infection (NEI U10 EY016214) in children (0 - 9 years) in three districts of the Wag Hemra zone of Amhara, Ethiopia. Prior to this trial, door-to-door census was performed to collect demographic information and from this, a random sample of 60 children in each cluster were chosen for inclusion. [83] | CDC, USA (DBS) |

| 2 | Africa (Haiti, Tanzania, and Kenya) | Samples from previous studies (1990 – 1999; 2012 – 2015) Haiti: Household-based cohort study examining LF prevalence in young children (0-4 years) at 6 - 9 monthly intervals in the coastal town of Leogane, Haiti between 1990-1999. Households were selected based on the high prevalence of LF in previous surveys (1990 and 1991). Kenya: A household-based randomized-controlled intervention trial to assess the impact of ceramic water filters on prevention of diarrhea and cryptosporidiosis in young children (4 - 10 months) in the Siaya county of western Kenya. The sampling frame was provided by the health and demographic surveillance system for the region with random sampling of households. Tanzania: House-hold-based, randomized control trial of children (1 - 9 years) examining the effects of annual azithromycin distribution on trachoma infection in 96 independent clusters from the Kongwa district of Tanzania. Clusters were chosen if not previously treated followed by random selection of households. [84,85,86] | CDC, USA (DBS) |

| 10 | Western Pacific (American Samoa) | Transmission assessment survey (TAS) for LF: Data were obtained from three TASs conducted across elementary schools (children aged 6 - 7 years) in American Samoa (all schools on the main island of Tutuila and the adjacent island of Aunu’u) in 2011, 2015, and 2016. Surveys were carried out at 25, 30, and 29 schools for each survey year, respectively. [72] | CDC, USA (DBS) |

| 11 | Western Pacific (Malaysia) | Environmentally stratified, population based cross-sectional study (2015) aimed to understand the transmission of malaria in people aged over 3 years, in northern Sabah as part of the MONKEYBAR project. A non-self-weighting two-stage sampling design whereby villages were selected based on proportion of forest cover and 20 household within each village were randomly selected. [64] | CDC, USA (DBS) |

| 13 | South-East Asia (Bangladesh) | Emergency Nutrition Assessment (2018) - This survey used data and samples from the study described by Lu, et al. (2020). In brief, a survey was conducted in two areas of Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh (Nayapara and makeshift settlement camps (MSs)) alongside an Emergency Nutrition Assessment. In Nayapara, households were selected using simple random sampling whereby in MSs, a cluster sampling design was used. [67] | CDC, USA (DBS) |

| 16 | Africa (Ghana) | Trachoma pre-validation: A population-based survey conducted in the Northern, Northeast, Savanna and Upper West regions of Ghana between 2015 - 2016 using a two-stage cluster-sampled approach. This survey targeted children (1 - 9 years) as this age group have the highest risk of active trachoma. Villages were chosen proportional to population size and households were selected using compact segment sampling. [87,88] | CDC, USA (DBS) |

| 17 | Africa (Kenya) | Primary study: Random selection (based on site, sex, and age group) of participants (all ages) based off the Health and Demographic Surveillance System database of two Kenyan towns, Kwale and Mbita. Prior to recruitment, individuals were visited at their household and invited to participate by attending a blood sampling location the following day. This was conducted in 2011. | Nairobi laboratory, Kenya (Serum) |

| 23 | Africa (Tanzania) | Sample were leftover serum samples from the Mother-Offspring Malaria Study Project, a large cohort study conducted from 2002 - 2006 in Muheza, northeastern Tanzania, an area of intense malaria transmission. Pregnant mothers (18 - 45 years) were recruited prior to giving birth at the Muheza Designated District Hospital. Infants were seen at birth and at 2-week intervals for full clinical examination and blood sampling for the first year of life. [89] | Not reported (Serum) |

| 29 | Europe (United Kingdom) | The UK Biobank is a large prospective study with over 500,000 participants aged 40 – 69 years, recruited between 2006–2010. Participants were recruited from 22 assessment centers throughout the UK, covering a variety of different settings to provide socioeconomic and ethnic heterogeneity and urban–rural mix. [90] | Oxford University, UK (Serum) |

| 30 | Americas (Alaska) | A cross-sectional survey investigating exposure to highly pathogenic avian influenza virus H5N1 in individuals and their families (>5 years) in Anchorage and western Alaska between 2007 – 2008. Target participants were grouped into four groups that had regular contact with wild birds: (i) rural subsistence bird hunters and (ii) their family members, (iii) urban sport hunters, and (iv) wildlife biologists. [91] | CDC, USA (Serum) |

| 33 | Americas (Alaska) | A cross-sectional survey investigating exposure to highly pathogenic avian influenza virus H5N1 in individuals and their families (>5 years) in Anchorage and western Alaska between 2007 – 2008. Target participants were grouped into four groups that had regular contact with wild birds: (i) rural subsistence bird hunters and (ii) their family members, (iii) urban sport hunters, and (iv) wildlife biologists. [91] | CDC, USA (Serum) |

| 45 | Western Pacific (American Samoa) | Transmission assessment survey (TAS) for LF: Data were obtained from 3 TASs conducted across elementary schools (children aged 6 - 7 years) in American Samoa (all schools on the main island of Tutuila and the adjacent island of Aunu’u) in 2011 and 2015. Target sample sizes in 2011 and 2015 were 1,042 and 1,014, respectively. [72] | CDC, USA (Serum) |

| 46 | Europe (France) | A mix of samples from routine hospital medical care (94.4%) of individuals of all ages (0 - 100 years) or samples collected in the INCOVPED (NCT04336761) study; an observational study examining COVID-19 prevalence in children presenting to emergency departments in north-eastern France. (COVID-19 and seasonal HCoV). Samples collected between 2002 – 2020. | Institut Pasteur, France (Serum) |

| 47 | Africa (Rwanda) | A nested village-level study (10 households with at least one child under 4 years) within a cluster-randomized trial. The larger cluster-randomized trial consisted of 96 sectors (each with approximately 40 villages) in western region of Rwanda whereby 72 sectors received the intervention (improved cookstoves and household water filters) and 24 sectors acted as controls. Selection for inclusion within the nested-study was determined using a stratified, two-stage design - purposive sampling of study areas then random sampling of households. Conducted between 2014 and 2016. [92] | CDC, USA (DBS) |

| Malaria plus combination of NTDs/VPDs/Other | |||

| 3 | Africa (Niger, Malawi, and Tanzania) | Pre-specified, secondary analysis of the MORDOR Niger trial (CT02048007) where 30 rural communities were randomized 1:1 to biannual mass azithromycin distribution or placebo offered to all children 1 - 59 months (0 - 4 years). Communities were chosen for the trial if the population was between 200 and 2000 inhabitants. A sub-study examining morbidity randomly selected 30 communities from the trial and all households in each community were visited and invited to participate in this component. From this, 50 children within each community were asked to provide samples. This study was conducted between 2014 and 2020. [93,94] | CDC, USA (DBS) |

| 12 | Americas (Haiti) | Under the Global Fund grant against malaria, enumeration areas (117 communities) throughout Haiti were selected based on high risk of malaria. Households (20 per enumeration area) were chosen at random, and people of all ages were invited to participate. This study was conducted between 2014 and 2015. | CDC, USA (DBS |

| 34 | Americas (Haiti) | A randomized, placebo-controlled trial conducted between 1998 and 1999 investigating the tolerance, efficacy, and nutritional benefit of combining chemotherapeutic treatment of intestinal helminths and lymphatic filariasis in the coastal town of Leogane, Haiti. Twelve selected primary schools were chosen, and all children aged 5 - 11 years were eligible to participate. Allocation to treatment groups was randomized. [95] | CDC, USA (Serum) |

| 35 | Africa (Kenya) | Cross-sectional study conducted in Eastern and Southern Africa Centre of International Parasitic Control (ESACIPAC), to provide a comprehensive epidemiological assessment of LF infection in people aged over 2 years (as recommended by WHO LF guidelines) before restarting MDA. 10 sentinel sites in costal Kenya were selected and from this, five were selected based on LF risk. Household sampling was conducted door-to-door to achieve a sample size of 300 per sentinel site. This study was conducted in 2015. [72,96] | Nairobi, Kenya (DBS) |

| 38 | Africa (Mozambique) | Primary study: Two consecutive cross-sectional household surveys before and after the LLIN campaign in six rural districts of the northern province of Nampula. From each district, 20 survey clusters were chosen randomly, with random selection of households within each cluster. Individuals of all ages were invited to participate. This study was conducted in 2013 and 2014. | CDC, USA (DBS) |

| 39 | Americas (Haiti) | Household-based longitudinal cohort study (n=61) based on the coastal town of Ca Ira examining the effect of DEC fortified salt on transmission of LF in children (2-10 years) at time points of 2011, 2013, and 2014. Additional samples (n=127) were collected from the above cohort in 2014 as well as samples from additional children (2 - 10 years) in Ca Ira that had not been previously sampled. This study was conducted in 2011, 2013 and 2014. | CDC, USA (DBS) |

| 40 | Western Pacific (Cambodia) | Nationally representative survey (conducted in 2012) designed to estimate serological evidence to vaccine preventable diseases in women of childbearing age (15 - 39 years). Based on the 2009 Cambodian neonatal tetanus risk assessment, multi-stage cluster sampling was performed with oversampling of areas with higher risk of tetanus. [97,98] | CDC, USA (Serum) |

Discussion

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of interest

References

- Arnold, B.F., et al., Measuring changes in transmission of neglected tropical diseases, malaria, and enteric pathogens from quantitative antibody levels. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 2017. 11(5). [CrossRef]

- Haselbeck, A.H., et al., Serology as a Tool to Assess Infectious Disease Landscapes and Guide Public Health Policy. Pathogens, 2022. 11(7). [CrossRef]

- Hatherell, H.-A., et al., Sustainable surveillance of neglected tropical diseases for the post-elimination era. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2021. 72(Supplement_3): p. S210-S216. [CrossRef]

- Arnold, B.F., H.M. Scobie, J.W. Priest, and P.J. Lammie, Integrated serologic surveillance of population immunity and disease transmission. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 2018. 24(7): p. 1188-1194. [CrossRef]

- Elshal, M.F. and J.P. McCoy, Multiplex bead array assays: performance evaluation and comparison of sensitivity to ELISA. Methods, 2006. 38(4): p. 317-323. [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.Y., et al., Determining seropositivity-a review of approaches to define seroprevalence when using multiplex bead assays to assess burden of tropical diseases. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 2020. 103(5 SUPPL): p. 123-124. [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, H., Monoplex and multiplex immunoassays: approval, advancements, and alternatives. Comparative clinical pathology, 2022. 31(2): p. 333-345. [CrossRef]

- Benedicto-Matambo, P., et al. Exploring natural immune responses to Shigella exposure using multiplex bead assays on dried blood spots in high-burden countries: protocol from a multisite diarrhea surveillance study. in Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2024. Oxford University Press US. [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, J., et al., Sero-epidemiology as a tool to study the incidence of Salmonella infections in humans. Epidemiology & Infection, 2008. 136(7): p. 895-902. [CrossRef]

- Ward, S., H. Lawford, B. Sartorius, and C. Lau, Integrated serosurveillance of infectious diseases using multiplex bead assays: A systematic review. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Veritas Health Innovation, Covidence systematic review software. 2023: Melbourne, Australia,.

- Page, M.J., et al., The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International journal of surgery, 2021. 88: p. 105906. [CrossRef]

- Aiemjoy, K., et al., Seroprevalence of antibodies against Chlamydia trachomatis and enteropathogens and distance to the nearest water source among young children in the Amhara Region of Ethiopia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2020. 14(9): p. e0008647. [CrossRef]

- Arnold, B.F., et al., Enteropathogen antibody dynamics and force of infection among children in low-resource settings. eLife, 2019. 8. [CrossRef]

- Arzika, A.M., et al., Effect of biannual azithromycin distribution on antibody responses to malaria, bacterial, and protozoan pathogens in Niger. Nature communications, 2022. 13(1): p. 976. [CrossRef]

- Assefa, A., et al., Multiplex serology demonstrate cumulative prevalence and spatial distribution of malaria in Ethiopia. Malar J, 2019. 18(1): p. 246. [CrossRef]

- Boey, L., et al., Seroprevalence of Antibodies against Diphtheria, Tetanus and Pertussis in Adult At-Risk Patients. Vaccines (Basel), 2021. 9(1). [CrossRef]

- Breakwell, L., et al., Seroprevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection and immunity to measles, rubella, tetanus and diphtheria among schoolchildren aged 6-7 years old in the Solomon Islands, 2016. Vaccine, 2020. 38(30): p. 4679-4686. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, I., et al., Characterizing the spatial distribution of multiple malaria diagnostic endpoints in a low-transmission setting in Lao PDR. Front Med (Lausanne), 2022. 9: p. 929366. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, I., et al., Serological evaluation of risk factors for exposure to malaria in a pre-elimination setting in Malaysian Borneo. Sci Rep, 2023. 13(1): p. 12998. [CrossRef]

- Caboré, R.N., D. Piérard, and K. Huygen, A Belgian serosurveillance/seroprevalence study of diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis using a luminex xMAP technology-based pentaplex. Vaccines, 2016. 4(2). [CrossRef]

- Cadavid Restrepo, A.M., et al., Potential use of antibodies to provide an earlier indication of lymphatic filariasis resurgence in post–mass drug ad ministration surveillance in American Samoa. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 2022. 117: p. 378-386. [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.L., et al., Assessing seroprevalence and associated risk factors for multiple infectious diseases in Sabah, Malaysia using serological multiplex bead assays. Front Public Health, 2022. 10: p. 924316. [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y., et al., Multiplex Serology for Measurement of IgG Antibodies Against Eleven Infectious Diseases in a National Serosurvey: Haiti 2014-2015. Front Public Health, 2022. 10: p. 897013. [CrossRef]

- Cooley, G.M., et al., No Serological Evidence of Trachoma or Yaws Among Residents of Registered Camps and Makeshift Settlements in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2021. 104(6): p. 2031-2037. [CrossRef]

- Feldstein, L.R., et al., Vaccination coverage survey and seroprevalence among forcibly displaced Rohingya children, Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh, 2018: A cross-sectional study. PLoS Med, 2020. 17(3): p. e1003071. [CrossRef]

- Feleke, S.M., et al., Sero-identification of the aetiologies of human malaria exposure (Plasmodium spp.) in the Limu Kossa District of Jimma Zone, South western Ethiopia. Malar J, 2019. 18(1): p. 292. [CrossRef]

- Fornace, K.M., et al., Characterising spatial patterns of neglected tropical disease transmission using integrated sero-surveillance in Northern Ghana. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 2022. 16(3). [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y., et al., Serological Surveillance Development for Tropical Infectious Diseases Using Simultaneous Microsphere-Based Multiplex Assays and Finite Mixture Models. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 2014. 8(7). [CrossRef]

- Herman, C., et al., Non-falciparum malaria infection and IgG seroprevalence among children under 15 years in Nigeria, 2018. Nat Commun, 2023. 14(1): p. 1360. [CrossRef]

- Jeang, B., et al., Serological Markers of Exposure to Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax Infection in Southwestern Ethiopia. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 2023. 108(5): p. 871-881. [CrossRef]

- Khaireh, B.A., et al., Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum infections in the Republic of Djibouti: Evaluation of their prevalence and potential determinants. Malaria Journal, 2012. 11. [CrossRef]

- Khetsuriani, N., et al., Diphtheria and tetanus seroepidemiology among children in Ukraine, 2017. Vaccine, 2022. 40(12): p. 1810-1820. [CrossRef]

- Koffi, D., et al., Longitudinal analysis of antibody responses in symptomatic malaria cases do not mirror parasite transmission in peri-urban area of Cote d'Ivoire between 2010 and 2013. PLoS One, 2017. 12(2): p. e0172899. [CrossRef]

- Kwan, J.L., et al., Seroepidemiology of helminths and the association with severe malaria among infants and young children in Tanzania. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 2018. 12(3). [CrossRef]

- Labadie-Bracho, M.Y., F.T. van Genderen, and M.R. Adhin, Malaria serology data from the Guiana shield: first insight in IgG antibody responses to Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium malariae antigens in Suriname. Malar J, 2020. 19(1): p. 360. [CrossRef]

- Leonard, C.M., et al., Spatial Distribution of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax in Northern Ethiopia by Microscopic, Rapid Diagnostic Test, Laboratory Antibody, and Antigen Data. J Infect Dis, 2022. 225(5): p. 881-890. [CrossRef]

- Lu, A., et al., Screening for malaria antigen and anti-malarial IgG antibody in forcibly-displaced Myanmar nationals: Cox's Bazar district, Bangladesh, 2018. Malar J, 2020. 19(1): p. 130. [CrossRef]

- Macalinao, M.L.M., et al., Analytical approaches for antimalarial antibody responses to confirm historical and recent malaria transmission: an example from the Philippines. The Lancet Regional Health - Western Pacific, 2023. 37. [CrossRef]

- McCaffery, J.N., et al., The use of a chimeric antigen for Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax seroprevalence estimates from community surveys in Ethiopia and Costa Rica. PLoS ONE, 2022. 17(5 5). [CrossRef]

- Mentzer, A.J., et al., Identification of host–pathogen-disease relationships using a scalable multiplex serology platform in UK Biobank. Nature Communications, 2022. 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Miernyk, K.M., et al., Human Seroprevalence to 11 Zoonotic Pathogens in the U.S. Arctic, Alaska. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases, 2019. 19(8): p. 563-575. [CrossRef]

- Minta, A.A., et al., Seroprevalence of Measles, Rubella, Tetanus, and Diphtheria Antibodies among Children in Haiti, 2017. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2020. 103(4): p. 1717-1725. [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, E.F., et al., Antibody Profile Comparison against MSP1 Antigens of Multiple Plasmodium Species in Human Serum Samples from Two Different Brazilian Populations Using a Multiplex Serological Assay. Pathogens, 2021. 10(9). [CrossRef]

- Mosites, E., et al., Giardia and Cryptosporidium antibody prevalence and correlates of exposure among Alaska residents, 2007-2008. Epidemiol Infect, 2018. 146(7): p. 888-894. [CrossRef]

- Moss, D.M., et al., Multiplex bead assay for serum samples from children in Haiti enrolled in a drug study for the treatment of lymphatic filariasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2011. 85(2): p. 229-37. [CrossRef]

- Njenga, S.M., et al., Integrated Cross-Sectional Multiplex Serosurveillance of IgG Antibody Responses to Parasitic Diseases and Vaccines in Coastal Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2020. 102(1): p. 164-176. [CrossRef]

- Oviedo, A., et al., Spatial cluster analysis of Plasmodium vivax and P. malariae exposure using serological data among Haitian school children sampled between 2014 and 2016. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2022. 16(1): p. e0010049. [CrossRef]

- Perraut, R., et al., Serological signatures of declining exposure following intensification of integrated malaria control in two rural Senegalese communities. PLoS ONE, 2017. 12(6). [CrossRef]

- Plucinski, M.M., et al., Multiplex serology for impact evaluation of bed net distribution on burden of lymphatic filariasis and four species of human malaria in northern Mozambique. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 2018. 12(2). [CrossRef]

- Poirier, M.J., et al., Measuring Haitian children's exposure to chikungunya, dengue and malaria. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 2016. 94(11): p. 817-825A. [CrossRef]

- Priest, J.W., et al., Integration of Multiplex Bead Assays for Parasitic Diseases into a National, Population-Based Serosurvey of Women 15-39 Years of Age in Cambodia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2016. 10(5): p. e0004699. [CrossRef]

- Rogier, E., et al., Evaluation of Immunoglobulin G Responses to Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax in Malian School Children Using Multiplex Bead Assay. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2017. 96(2): p. 312-318. [CrossRef]

- Rogier, E., et al., High-throughput malaria serosurveillance using a one-step multiplex bead assay. Malar J, 2019. 18(1): p. 402. [CrossRef]

- Tohme, R.A., et al., Tetanus and Diphtheria Seroprotection among Children Younger Than 15 Years in Nigeria, 2018: Who Are the Unprotected Children? Vaccines (Basel), 2023. 11(3). [CrossRef]

- van den Hoogen, L.L., et al., Rapid Screening for Non-falciparum Malaria in Elimination Settings Using Multiplex Antigen and Antibody Detection: Post Hoc Identification of Plasmodium malariae in an Infant in Haiti. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2021. 104(6): p. 2139-2145. [CrossRef]

- Won, K.Y., et al., Comparison of antigen and antibody responses in repeat lymphatic filariasis transmission assessment surveys in American Samoa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2018. 12(3): p. e0006347. [CrossRef]

- Woudenberg, T., et al., Humoral immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and seasonal coronaviruses in children and adults in north-eastern France. EBioMedicine, 2021. 70: p. 103495. [CrossRef]

- Zambrano, L.D., et al., Use of serologic responses against enteropathogens to assess the impact of a point-of-use water filter: A randomized controlled trial in western province, Rwanda. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 2017. 97(3): p. 876-887. [CrossRef]

- Won, K.Y., et al., Use of antibody tools to provide serologic evidence of elimination of lymphatic filariasis in the Gambia. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 2018. 98(1): p. 15-20. [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y., et al., Determining seropositivity—a review of approaches to define population seroprevalence when using multiplex bead assays to assess burden of tropical diseases. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 2021. 15(6). [CrossRef]

- Institute, E.P.H., Ethiopia National Malaria Indicator Survey 2015. 2016: Ethiopia.

- Lover, A.A., et al., Prevalence and risk factors for asymptomatic malaria and genotyping of glucose 6-phosphate (G6PD) deficiencies in a vivax-predominant setting, Lao PDR: implications for sub-national elimination goals. Malaria journal, 2018. 17: p. 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Fornace, K.M., et al., Environmental risk factors and exposure to the zoonotic malaria parasite Plasmodium knowlesi across northern Sabah, Malaysia: a population-based cross-sectional survey. The Lancet Planetary Health, 2019. 3(4): p. e179-e186. [CrossRef]

- Health, F.M.o., Nigeria HIV/AIDS Indicator and Impact Survey (NAIIS) 2018: Technical Report. 2019: Abuja, Nigeria.

- Koffi, D., et al., Analysis of antibody profiles in symptomatic malaria in three sentinel sites of Ivory Coast by using multiplex, fluorescent, magnetic, bead-based serological assay (MAGPIX™). Malar J, 2015. 14: p. 509. [CrossRef]

- Group, A.A.H.C.a.t.T.A., Standardized Monitoring and Assessment for Relief and Transitions Methodology Manual 2.0. 2017.

- Reyes, R.A., et al., Enhanced health facility surveys to support malaria control and elimination across different transmission settings in the Philippines. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 2021. 104(3): p. 968. [CrossRef]

- Curado, I., et al., Antibodies anti bloodstream and circumsporozoite antigens (Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium malariae/P. brasilianum) in areas of very low malaria endemicity in Brazil. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, 1997. 92: p. 235-243. [CrossRef]

- Silva-Nunes, M.d., et al., The Acre Project: the epidemiology of malaria and arthropod-borne virus infections in a rural Amazonian population. Cadernos de Saude Publica, 2006. 22: p. 1325-1334.

- Medeiros, M.M., et al., Natural antibody response to Plasmodium falciparum merozoite antigens MSP5, MSP9 and EBA175 is associated to clinical protection in the Brazilian Amazon. BMC Infectious Diseases, 2013. 13: p. 1-19. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, Monitoring and epidemiological assessment of mass drug administration in the global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis: a manual for national elimination programmes. 2011.

- Organization, W.H., Assessing the epidemiology of soil-transmitted helminths during a transmission assessment survey in the global programme for the elimination of lymphatic filariasis. 2015.

- Diene Sarr, F., et al., Acute febrile illness and influenza disease burden in a rural cohort dedicated to malaria in senegal, 2012–2013. PLoS One, 2015. 10(12): p. e0143999. [CrossRef]

- Trape, J.-F., et al., The rise and fall of malaria in a west African rural community, Dielmo, Senegal, from 1990 to 2012: a 22 year longitudinal study. The Lancet infectious diseases, 2014. 14(6): p. 476-488. [CrossRef]

- Trinies, V., J.V. Garn, H.H. Chang, and M.C. Freeman, The impact of a school-based water, sanitation, and hygiene program on absenteeism, diarrhea, and respiratory infection: a matched–control trial in Mali. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 2016. 94(6): p. 1418. [CrossRef]

- Ashton, R.A., et al., Risk Factors for Malaria Infection and Seropositivity in the Elimination Area of Grand'Anse, Haiti: A Case-Control Study among Febrile Individuals Seeking Treatment at Public Health Facilities. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2020. 103(2): p. 767-777. [CrossRef]

- Huygen, K., et al., Bordetella pertussis seroprevalence in Belgian adults aged 20–39 years, 2012. Epidemiology & Infection, 2014. 142(4): p. 724-728. [CrossRef]

- Huseynov, S., N. Khetsuriani, N. Chitadze, and L. Slobodianyk, Poliomyelitis, measles, rubella, diphtheria, tetanus, and hepatitis B seroepidemiology among children born in 2006–2015 in four regions on Ukraine, 2017. 2021.

- Khetsuriani, N., et al., Seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus infection markers among children in Ukraine, 2017. Vaccine, 2021. 39(10): p. 1485-1492. [CrossRef]

- Khetsuriani, N., et al., Responding to a cVDPV1 outbreak in Ukraine: Implications, challenges and opportunities. Vaccine, 2017. 35(36): p. 4769-4776. [CrossRef]

- Childs, L., et al., Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection among children in Haiti, 2017. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 2019. 101(1): p. 214. [CrossRef]

- Stoller, N.E., et al., Efficacy of latrine promotion on emergence of infection with ocular Chlamydia trachomatis after mass antibiotic treatment: a cluster-randomized trial. International health, 2011. 3(2): p. 75-84. [CrossRef]

- Lammie, P.J., et al., Longitudinal analysis of the development of filarial infection and antifilarial immunity in a cohort of Haitian children. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 1998. 59(2): p. 217-221. [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.F., et al., A randomized controlled trial to assess the impact of ceramic water filters on prevention of diarrhea and cryptosporidiosis in infants and young children—western Kenya, 2013. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 2018. 98(5): p. 1260-1268. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N., et al., Evaluation of a single dose of azithromycin for trachoma in low-prevalence communities. Ophthalmic epidemiology, 2019. 26(1): p. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, Validation of elimination of trachoma as a public health problem. 2016.

- Debrah, O., et al., Elimination of trachoma as a public health problem in Ghana: Providing evidence through a pre-validation survey. PLoS neglected tropical diseases, 2017. 11(12): p. e0006099. [CrossRef]

- Mutabingwa, T.K., et al., Maternal malaria and gravidity interact to modify infant susceptibility to malaria. PLoS medicine, 2005. 2(12): p. e407. [CrossRef]

- Sudlow, C., et al., UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS medicine, 2015. 12(3): p. e1001779. [CrossRef]

- Reed, C., et al., Characterizing wild bird contact and seropositivity to highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) virus in Alaskan residents. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses, 2014. 8(5): p. 516-523. [CrossRef]

- Nagel, C.L., et al., Study design of a cluster-randomized controlled trial to evaluate a large-scale distribution of cook stoves and water filters in Western Province, Rwanda. Contemporary clinical trials communications, 2016. 4: p. 124-135. [CrossRef]

- Oldenburg, C., et al., Annual versus biannual mass azithromycin distribution and serologic markers of trachoma among children in Niger: a community randomized trial. American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 2018. 99(4): p. 436.

- Keenan, J.D., et al., Azithromycin to reduce childhood mortality in sub-Saharan Africa. New England Journal of Medicine, 2018. 378(17): p. 1583-1592. [CrossRef]

- Fox, L.M., et al., Tolerance and efficacy of combined diethylcarbamazine and albendazole for treatment of Wuchereria bancrofti and intestinal helminth infections in Haitian children. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 2005. 73(1): p. 115-121. [CrossRef]

- Njenga, S.M., et al., Assessment of lymphatic filariasis prior to re-starting mass drug administration campaigns in coastal Kenya. Parasites & vectors, 2017. 10: p. 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Scobie, H.M., et al., Tetanus immunity among women aged 15 to 39 years in Cambodia: a national population-based serosurvey, 2012. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology, 2016. 23(7): p. 546-554. [CrossRef]

- Mao, B., et al., Immunity to polio, measles and rubella in women of child-bearing age and estimated congenital rubella syndrome incidence, Cambodia, 2012. Epidemiology & Infection, 2015. 143(9): p. 1858-1867. [CrossRef]

- Plucinski, M.M., et al., Screening for Pfhrp2/3-Deleted Plasmodium falciparum, Non-falciparum, and Low-Density Malaria Infections by a Multiplex Antigen Assay. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 2019. 219(3): p. 437-447. [CrossRef]

- Rogier, E., et al., Bead-based immunoassay allows subpicogram detection of histidine-rich protein 2 from Plasmodium falciparum & estimates reliability of malaria rapid diagnostic tests. PLoS ONE, 2017. 12(2). [CrossRef]

- Gelband, H., et al., Is malaria an important cause of death among adults? The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 2020. 103(1): p. 41. [CrossRef]

- Roser, M., Malaria: One of the leading causes of child deaths, but progress is possible and you can contribute to it, in Our World in Data. 2024.

- Talapko, J., et al., Malaria: the past and the present. Microorganisms, 2019. 7(6): p. 179. [CrossRef]

- Organization, W.H., World malaria report 2023. 2023: World Health Organization.

- Yang, X., M.B. Quam, T. Zhang, and S. Sang, Global burden for dengue and the evolving pattern in the past 30 years. Journal of travel medicine, 2021. 28(8): p. taab146. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., et al., Global epidemiology and burden of tetanus from 1990 to 2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 2023. 132: p. 118-126. [CrossRef]

- Nsubuga, P., et al., Public health surveillance: a tool for targeting and monitoring interventions. 2011.

- Jain, S. and S.K. Sharma, Challenges & options in dengue prevention & control: A perspective from the 2015 outbreak. Indian Journal of Medical Research, 2017. 145(6): p. 718-721. [CrossRef]

- den Hartog, G., et al., Immune surveillance for vaccine-preventable diseases. Expert review of vaccines, 2020. 19(4): p. 327-339. [CrossRef]

- MacNeil, A., C.-w. Lee, and V. Dietz, Issues and considerations in the use of serologic biomarkers for classifying vaccination history in household surveys. Vaccine, 2014. 32(39): p. 4893-4900. [CrossRef]

- Cutts, F.T. and M. Hanson, Seroepidemiology: an underused tool for designing and monitoring vaccination programmes in low-and middle-income countries. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 2016. 21(9): p. 1086-1098. [CrossRef]

- Azizi, H., et al., Health workers readiness and practice in malaria case detection and appropriate treatment: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Malaria Journal, 2021. 20: p. 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), Toolkit for Integrated Serosurveillance of Communicable Diseases in the Americas. 2022: Washington, D.C.

- Sbarra, A.N., et al., Evaluating Scope and Bias of Population-Level Measles Serosurveys: A Systematized Review and Bias Assessment. Vaccines, 2024. 12(6): p. 585. [CrossRef]

- Daag, J.V., et al., Performance of dried blood spots compared with serum samples for measuring dengue seroprevalence in a cohort of children in Cebu, Philippines. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 2021. 104(1): p. 130. [CrossRef]

- Styer, L.M., et al., High-throughput multiplex SARS-CoV-2 IgG microsphere immunoassay for dried blood spots: a public health strategy for enhanced serosurvey capacity. Microbiology spectrum, 2021. 9(1): . [CrossRef]

- Curtis, K.A., K.M. Ambrose, M. Susan Kennedy, and S. Michele Owen, Evaluation of dried blood spots with a multiplex assay for measuring recent HIV-1 Infection. PLoS ONE, 2014. 9(9). [CrossRef]

- Amini, F., et al., Reliability of dried blood spot (DBS) cards in antibody measurement: A systematic review. PLoS One, 2021. 16(3): p. e0248218. [CrossRef]

- Organization, W.H., Generic framework for control, elimination and eradication of neglected tropical diseases. 2016, World Health Organization.

- Organization, W.H., Validation of elimination of lymphatic filariasis as a public health problem. 2017.

- World Health Organization, Ending the neglect to attain the Sustainable Development Goals: a road map for neglected tropical diseases 2021–2030. 2020.

| ID | First author, year, [reference] | Title |

| 1 | Aiemjoy 2020 [13] | Seroprevalence of antibodies against Chlamydia trachomatis and enteropathogens and distance to the nearest water source among young children in the Amhara Region of Ethiopia |

| 2 | Arnold 2019 [14] | Enteropathogen antibody dynamics and force of infection among children in low-resource settings |

| 3 | Arzika 2022 [15] | Effect of biannual azithromycin distribution on antibody responses to malaria, bacterial, and protozoan pathogens in Niger |

| 4 | Assefa 2019 [16] | Multiplex serology demonstrate cumulative prevalence and spatial distribution of malaria in Ethiopia |

| 5 | Boey 2021 [17] | Seroprevalence of antibodies against diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis in adult at-risk patients |

| 6 | Breakwell 2020 [18] | Seroprevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection and immunity to measles, rubella, tetanus and diphtheria among schoolchildren aged 6-7 years old in the Solomon Islands, 2016 |

| 7 | Byrne 2022 [19] | Characterizing the spatial distribution of multiple malaria diagnostic endpoints in a low-transmission setting in Lao PDR |

| 8 | Byrne 2023 [20] | Serological evaluation of risk factors for exposure to malaria in a pre-elimination setting in Malaysian Borneo |

| 9 | Cabora 2016 [21] | A Belgian serosurveillance/seroprevalence study of diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis using a luminex xMAP technology-based pentaplex |

| 10 | Cadavid Restrepo 2022 [22] | Potential use of antibodies to provide an earlier indication of lymphatic filariasis resurgence in post mass drug administration surveillance in American Samoa |

| 11 | Chan 2022 [23] | Assessing seroprevalence and associated risk factors for multiple infectious diseases in Sabah, Malaysia using serological multiplex bead assays |

| 12 | Chan 2022 [24] | Multiplex serology for measurement of IgG antibodies against eleven infectious diseases in a national serosurvey: Haiti 2014-2015 |

| 13 | Cooley 2021 [25] | No serological evidence of trachoma or yaws among residents of registered camps and makeshift settlements in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh |

| 14 | Feldstein 2020 [26] | Vaccination coverage survey and seroprevalence among forcibly displaced Rohingya children, Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh, 2018: A cross-sectional study |

| 15 | Feleke 2019 [27] | Sero-identification of the aetiologies of human malaria exposure (Plasmodium spp.) in the Limu Kossa District of Jimma Zone, Southwestern Ethiopia |

| 16 | Fornace 2022 [28] | Characterising spatial patterns of neglected tropical disease transmission using integrated sero-surveillance in Northern Ghana |

| 17 | Fujii 2014 [29] | Serological Surveillance Development for Tropical Infectious Diseases Using Simultaneous Microsphere-Based Multiplex Assays and Finite Mixture Models |

| 18 | Herman 2023 [30] | Non-falciparum malaria infection and IgG seroprevalence among children under 15 years in Nigeria, 2018 |

| 19 | Jeang 2023 [31] | Serological Markers of Exposure to Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax Infection in Southwestern Ethiopia |

| 20 | Khaireh 2012 [32] | Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum infections in the Republic of Djibouti: Evaluation of their prevalence and potential determinants |

| 21 | Khetsuriani 2022 [33] | Diphtheria and tetanus seroepidemiology among children in Ukraine, 2017 |

| 22 | Koffi 2017 [34] | Longitudinal analysis of antibody responses in symptomatic malaria cases do not mirror parasite transmission in peri-urban area of Cote d'Ivoire between 2010 and 2013 |

| 23 | Kwan 2018 [35] | Seroepidemiology of helminths and the association with severe malaria among infants and young children in Tanzania |

| 24 | Labadie-Bracho 2020 [36] | Malaria serology data from the Guiana shield: first insight in IgG antibody responses to Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium malariae antigens in Suriname |

| 25 | Leonard 2022 [37] | Spatial Distribution of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax in Northern Ethiopia by Microscopic, Rapid Diagnostic Test, Laboratory Antibody, and Antigen Data |

| 26 | Lu 2020 [38] | Screening for malaria antigen and anti-malarial IgG antibody in forcibly-displaced Myanmar nationals: Cox's Bazar district, Bangladesh, 2018 |

| 27 | Macalinao 2023 [39] | Analytical approaches for antimalarial antibody responses to confirm historical and recent malaria transmission: an example from the Philippines |

| 28 | McCaffery 2022 [40] | The use of a chimeric antigen for Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax seroprevalence estimates from community surveys in Ethiopia and Costa Rica |

| 29 | Mentzer 2022 [41] | Identification of host-pathogen-disease relationships using a scalable multiplex serology platform in UK Biobank |

| 30 | Miernyk 2019 [42] | Human seroprevalence to 11 zoonotic pathogens in the U.S. Arctic, Alaska |

| 31 | Minta 2020 [43] | Seroprevalence of measles, rubella, tetanus, and diphtheria antibodies among children in Haiti, 2017 |

| 32 | Monteiro 2021 [44] | Antibody profile comparison against msp1 antigens of multiple plasmodium species in human serum samples from two different Brazilian populations using a multiplex serological assay |

| 33 | Mosites 2018 [45] | Giardia and cryptosporidium antibody prevalence and correlates of exposure among Alaska residents, 2007-2008 |

| 34 | Moss 2011 [46] | Multiplex bead assay for serum samples from children in Haiti enrolled in a drug study for the treatment of lymphatic filariasis |

| 35 | Njenga 2020 [47] | Integrated cross-sectional multiplex serosurveillance of IgG antibody responses to parasitic diseases and vaccines in coastal Kenya |

| 36 | Oviedo 2022 [48] | Spatial cluster analysis of Plasmodium vivax and Plsmodium malariae exposure using serological data among Haitian school children sampled between 2014 and 2016 |

| 37 | Perraut 2017 [49] | Serological signatures of declining exposure following intensification of integrated malaria control in two rural Senegalese communities |

| 38 | Plucinski 2018 [50] | Multiplex serology for impact evaluation of bed net distribution on burden of lymphatic filariasis and four species of human malaria in northern Mozambique |

| 39 | Poirier 2016 [51] | Measuring Haitian children's exposure to chikungunya, dengue and malaria |

| 40 | Priest 2016 [52] | Integration of multiplex bead assays for parasitic diseases into a national, population-based serosurvey of women 15-39 years of age in Cambodia |

| 41 | Rogier 2017 [53] | Evaluation of immunoglobulin G responses to plasmodium falciparum and plasmodium vivax in Malian school children using multiplex bead assay |

| 42 | Rogier 2019 [54] | High-throughput malaria serosurveillance using a one-step multiplex bead assay |

| 43 | Tohme 2023 [55] | Tetanus and diphtheria seroprotection among children younger than 15 years in Nigeria, 2018: Who are the unprotected children? |

| 44 | vandenHoogen 2021 [56] | Rapid screening for non-falciparum malaria in elimination settings using multiplex antigen and antibody detection: Post hoc identification of plasmodium malariae in an infant in Haiti |

| 45 | Won 2018 [57] | Comparison of antigen and antibody responses in repeat lymphatic filariasis transmission assessment surveys in American Samoa |

| 46 | Woudenberg 2021 [58] | Humoral immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and seasonal coronaviruses in children and adults in north-eastern France |

| 47 | Zambrano 2017 [59] | Use of serologic responses against enteropathogens to assess the impact of a point-of-use water filter: A randomized controlled trial in western province, Rwanda |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).