1. Introduction

Mpox is a rare zoonotic disease caused by the monkeypox virus (MPXV), a member of the Orthopoxvirus genus within the

Poxviridae family. MPXV was first identified in 1958 during an outbreak among monkeys in a Danish research facility. Human infection was first documented in 1970 in a nine-month-old infant in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Endemic to West and Central Africa, mpox primarily arises in regions where frequent contact occurs between humans and wildlife or potential animal reservoirs. Transmission occurs primarily through direct contact with lesions, body fluids, or respiratory droplets from infected individuals or animals [

1,

2].

MPXV is currently classified into two major clades: clade I (formerly the Congo Basin clade), which includes subclades Ia and Ib, and clade II (formerly the West African clade), comprising subclades IIa and IIb. These clades differ in terms of virulence and clinical severity, with clade I being associated with more severe disease outcomes and higher mortality rates compared to clade II. [

1,

2,

3].

In May 2022, a global outbreak caused by clade IIb strains was identified in several non-endemic countries. Due to the rapid international spread of the virus, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared mpox a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) in July 2022. This decision underscored the urgent need to strengthen epidemiological surveillance and laboratory response capacities. On August 14, 2024, the WHO reissued the PHEIC declaration for mpox in response to a rise in infections caused by MPXV clade Ib in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and its spread to neighboring countries. Since then, cases of clade I mpox have been reported outside Africa, often associated with individuals with recent travel history to endemic areas. As of February 2025, the WHO had recorded over 130,000 confirmed mpox cases across 131 countries, including 304 deaths [

3,

4].

The typical clinical presentation of mpox includes a short febrile prodromal phase, followed by the progressive development of a characteristic skin rash with firm, umbilicated lesions. These lesions usually appear first on the head or face and subsequently spread to the limbs and trunk, maintaining a uniform stage of evolution. Lymphadenopathy is a distinguishing feature of the disease. However, in recent outbreaks atypical presentations have been reported, with lesions initially appearing in the genital area. The clinical differential diagnosis should include other exanthematous diseases, particularly varicella [

1].

Laboratory diagnosis of mpox is preferably performed using nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT), such as real-time or conventional polymerase chain reaction (PCR). These assays may be designed for general

Orthopoxvirus detection or, preferably, specifically target MPXV. Real-time PCR is the method of choice for initial diagnostic investigation due to its high sensitivity, specificity, and fast response time. In addition, viral genome sequencing provides valuable insights into transmission dynamics and plays a crucial role in molecular surveillance efforts. The most appropriate specimen for laboratory confirmation is lesion swab, with oropharyngeal swabs also recommended to complement diagnostic sensitivity. Depending on the patient’s clinical presentation, other specimen types, such as genital and/or rectal swabs, urine, and semen, may also be considered for testing [

5].

Early detection and the prompt implementation of control measures are essential to limit viral spread, underscoring the importance of reference laboratories equipped to respond rapidly to emerging health threats. In Portugal, the National Institute of Health Doutor Ricardo Jorge (INSA) has operated a dedicated Emergency Response and Biopreparedness Unit (UREB) since 2007. As the national reference laboratory for the detection of highly pathogenic agents, including Orthopoxvirus species, UREB plays a central role in laboratory-based surveillance, outbreak investigation, and rapid diagnostic support.

This study aims to describe the epidemiological evolution of mpox in Portugal between 2022 and 2025, characterize the major outbreak waves, and evaluate the diagnostic performance of different clinical sample types based on the experience of the national reference laboratory.

2. Materials and Methods

Clinical samples were collected from patients suspected of having mpox disease based on clinical observation, in healthcare facilities nationwide. All samples were tested at the UREB-INSA reference laboratory for MPXV screening.

A total of 5610 samples of different specimen from 2802 suspected patients were analyzed. Samples included lesion swabs (n=2977, 53.1%), oropharyngeal swabs (n=2146, 38.3%), rectal swabs (n=287, 5.1%), urine (n=99, 1.8%), and other specimen types (n=101, 1.8%), such as genital, ocular, cerebrospinal fluid, semen, peripheral blood, pleural fluid, serum and bronchial secretions. The number of samples exceeds the number of patients due to multiple specimens being collected from some individuals, as well as follow-up sampling in certain clinical cases. Additionally, samples from the same patient were collected and tested across different outbreak periods. Initially, lesion and oropharyngeal swabs were prioritized, in line with WHO recommendations. As understanding of the clinical presentation evolved other specimen types, such as rectal swabs and urine, were progressively incorporated into the diagnostic workflow.

Nucleic acid extraction from clinical specimens was carried out using the ANDiS Viral RNA Auto Extraction Kit on the ANDiS 350 automated platform (3DMed), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Detection of MPXV was performed using an in-house real-time PCR assay targeting the B7R gene, as previously described [

6]. Each run included positive, negative, and internal controls (RNAseP) to ensure assay reliability. PCR results were interpreted based on cycle threshold (Ct) values: negative (Ct ≥ 40), weakly positive (35 ≤ Ct < 40), and positive (Ct < 35). A case was considered laboratory-confirmed when at least one sample tested positive by real-time PCR.

For statistical analysis, sample characteristics between the positive and negative groups were compared using Fisher’s exact test, with a significance level set at p < 0.05, performed using GraphPad QuickCalcs [

7].

This study was conducted in accordance with all applicable ethical guidelines. INSA serves as the national reference laboratory in Portugal and is officially designated by the Directorate-General of Health—under Technical Orientation No. 004/2022 (May 31, 2022; updated March 8, 2024)—to perform MPXV diagnostic testing and genetic characterization. All samples were processed in an anonymized format, and no identifiable patient information or metadata was accessed or used.

3. Results

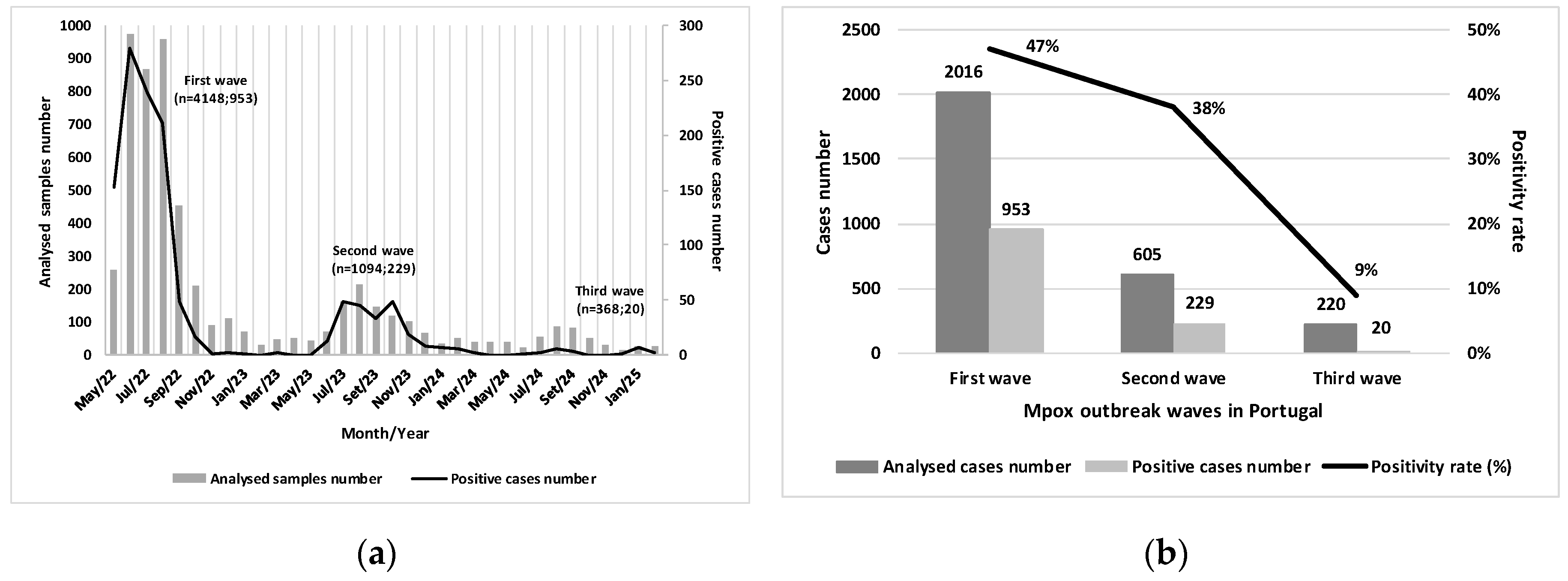

Between May 2022 and February 2025, three distinct mpox outbreak waves were identified in Portugal. The first wave, which occurred between May 2022 and March 2023, accounted for the majority of confirmed cases, with 953 cases, representing 79.3% of the total. The second wave, from June 2023 and March 2024, recorded 229 cases (19.0%), reflecting a significant decrease compared to the previous wave. The third wave began in June 2024 and recorded 20 cases (1.7%) up to February 28, 2025, totaling 1,202 confirmed cases reported by INSA (

Figure 1A).

During the first wave, a large volume of samples was analyzed, and a high positivity rate was observed (47.0%), with the peak frequency recorded in June 2022. The second wave showed lower intensity, with reductions in both sample volume and positive cases (positivity rate = 38.0%), and exhibited a more prolonged temporal distribution compared to the first. The third wave was characterized by a markedly lower positivity rate (9.0%). These findings suggest reduced viral circulation, indicating a phase of epidemiological decline and improved infection control (

Figure 1B).

Overall, the majority of cases were male (n=1,188; 98.8%), predominantly within the 20–29 (n=375; 31.2%) and 30–39 (n=512; 42.6%) age groups. Ages ranged from 17 to 66 years (median age of 33), with most cases occurring among men who have sex with men (MSM). Only 14 cases (1.2%) were reported in females, indicating a marked gender disparity. No cases were reported in children aged 0–9 years, and nine cases (0.7%) were reported in individuals over 60 years of age (

Table 1).

Positive cases were detected in all regions of Portugal, but the highest number was reported in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area (n=753; 79%), followed by the North (n=375; 31.2%) and Centre (n=234; 19.5%) regions (

Table 1).

In the detailed analysis of each outbreak wave, the data reveal a consistent predominance of male cases and individuals in the 20–29 and 30–39 age groups, with low representation among those under 20 and adults over 60 years of age.

The Lisbon Metropolitan Area accounted for 77.9% (n=742) of cases during the first outbreak and remained the most affected region in the second (n=153; 66.8%) and third outbreak waves (n=13; 65.0%), although its proportion gradually decreased. In contrast, the Northern region showed a significant increase in its share of cases, rising from 16.6% (n=158) in the first wave to 30.1% (n=69) in the second, and 35.0% (n=7) in the third. Notably, unlike the previous waves, which began in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, the third outbreak started in the Northern region. The Central, Alentejo, and Algarve regions, as well as the Autonomous Regions, maintained residual case numbers with little variation across the three outbreak waves.

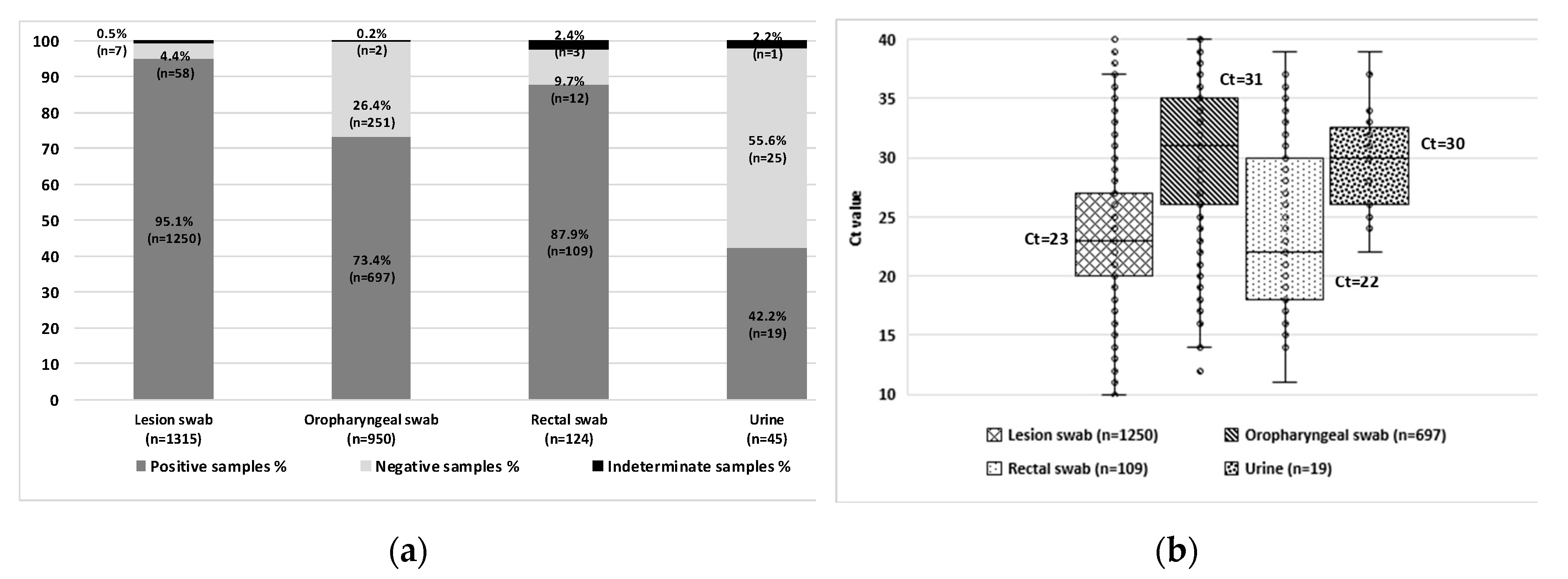

MPXV was detected in 2,075 samples from 1,202 patients. To evaluate the diagnostic performance of different specimen types for MPXV detection, a total of 2,434 samples (including positive, negative, and indeterminate results) collected from these 1,202 confirmed mpox cases were analyzed. The highest positivity rates were observed in lesion swabs (n=1,250/1,315; 95.1%) and rectal swabs (n=109/124; 87.9%), compared to oropharyngeal swabs (n=697/950; 73.4%) and urine samples (n=19/45; 42.2%) (

Figure 2A). A statistically significant difference in positivity rates was found among specimen types (p < 0.0001), except between lesion and rectal swabs.

In approximately 5% of cases during the first wave, diagnosis was achieved using oropharyngeal swabs (n=38; 3.9%), rectal swabs (n=5; 0.5%), or a combination of both (n=6/953; 0.6%) in patients with negative lesion swabs. All samples were collected on the same day as the corresponding lesion swab. These individuals were tested due to known contact with MPXV-positive cases or identified risk behaviors [

8].

Lesion and rectal swabs showed lower median Ct values (Ct=23 and Ct=22, respectively), indicating higher viral loads compared to oropharyngeal swabs (Ct=31) and urine samples (Ct=30) (

Figure 2B). These findings reinforce lesion and rectal swabs as the preferred specimen types for laboratory diagnosis of mpox, due to their higher viral loads and superior sensitivity for MPXV detection. Oropharyngeal swabs remain a valuable alternative, particularly in patients without visible lesions, while urine samples may serve as complementary specimens in atypical clinical scenarios.

4. Discussion

The first confirmed case of the 2022 mpox outbreak was reported in the United Kingdom on May 6, 2022, in a patient with a recent travel history to Nigeria. On May 17, 2022, Portugal became the second country to confirm mpox cases [

9,

10]. Subsequent studies revealed that the virus had been circulating silently within Portugal prior to official notification, which may explain the abrupt surge in initial case numbers [

8]. A mathematical model suggests that MPXV had been circulating for approximately 50 days before detection [

11].

In this study, 5,610 samples from 2,802 probable cases were analyzed, confirming MPXV infection in 1,202 patients. Genomic characterization identified subclade IIb (B.1 sublineages) across all three outbreak waves in Portugal, with no detection of clade I or subclade Ib strains [

12,

13].

The first outbreak was marked by high transmission intensity and rapid community spread, requiring an immediate laboratory response. Subsequent waves showed lower impact, with slower and more localized transmission, likely influenced by factors such as acquired immunity, behavioral changes, and targeted public health strategies. The third outbreak, originating in the Northern region, reflected a marked decline in viral circulation, indicative of improved epidemic control.

Demographic patterns remained consistent, with a predominance of cases among MSM, young adults, and residents of the Lisbon Metropolitan Area. These findings emphasize the importance of tailored public health interventions for high-risk populations.

Laboratory data indicated that lesion and rectal swabs were the most effective specimens for MPXV detection, given their high positivity rates and viral loads. However, oropharyngeal swabs proved a valuable alternative, particularly in cases without visible lesions, enabling diagnosis in ~5% of cases during the first outbreak [

8]. The consistent detection of MPXV in the oropharynx suggests its potential role in transmission, especially through direct oral contact [

8,

14,

15]. Although less sensitive, urine samples demonstrated some diagnostic utility (42.2% positivity) and may serve as complementary specimens, particularly in atypical clinical presentations.

These findings highlight the importance of collecting samples from multiple anatomical sites to enhance diagnostic sensitivity.

Laboratory surveillance between 2022 and 2025 identified three outbreak waves with progressively decreasing transmission intensity. This evolution reflects not only the natural course of infection but also the positive impact of public health interventions, including vaccination, screening strategies, and behavioral modifications.

Mathematical models indicate that transmission was strongly driven by high-risk sexual behavior, with an estimated 120-fold higher impact in subgroups with elevated sexual activity. Vaccination demonstrated high effectiveness, with vaccinated individuals contributing approximately eight times less to transmission and exhibiting milder symptoms, suggesting a key role in containing the second wave [

13].

Between June 2022 and February 2025, a total of 21,063 vaccine doses were administered in Portugal, 93.5% as pre-exposure prophylaxis, covering 11,771 individuals [

16].

Despite the decline in case numbers, the persistence of MPXV within the same target population reinforces the need for sustained surveillance and prevention strategies, risk-adapted approaches, and integration into early warning and rapid response systems. Mpox remains an emerging infection with re-emergence potential, requiring non-endemic countries to maintain laboratory capacity and active surveillance in order to detect and respond promptly to future outbreaks. This study has some limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the analysis was based solely on laboratory-confirmed cases, without integration of detailed clinical data or patient follow-up, which could have provided deeper insights into disease progression and atypical presentations. Additionally, the selection of specimen types evolved over time as clinical knowledge advanced, potentially introducing variability in diagnostic practices across the different outbreak waves. Finally, the absence of comprehensive behavioral and vaccination status data for all patients limited the ability to assess the influence of these factors on transmission dynamics. In conclusion, the progressive decline in mpox cases observed in Portugal underscores the critical role of timely laboratory surveillance, targeted vaccination, and risk-adapted public health interventions. However, the persistence of MPXV transmission within specific populations highlights the ongoing vulnerability to re-emergence. Sustained diagnostic capacity, continuous genomic surveillance, and proactive communication strategies remain essential components of preparedness frameworks. Lessons learned from these outbreak waves should inform international guidelines, ensuring that both endemic and non-endemic countries are equipped to detect, respond to, and effectively contain future mpox outbreaks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C.; methodology, R.C., R.F., A.P., I.L.C. and M.S.N.; formal analysis, R.C. and R.F.; data curation, R.C. and R.F.; writing—original draft preparation, R.C.; writing—review and editing, R:C., R.F., A.P., I.L.C. and M.S.N.; supervision, M.S.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all healthcare professionals for their support in the laboratory diagnosis of mpox cases. We also extend our gratitude to our colleagues Sílvia Lopo, Raquel Neves, Maria Raquel Rocha, Paula Palminha, and Maria José Borrego from DDI/INSA for their contribution to laboratory diagnostics during the first mpox outbreak wave.

This manuscript benefited from the use of ChatGPT (GPT-4 model, OpenAI, accessed via

https://chat.openai.com) to assist in language editing, paragraph restructuring, and summarization. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MPXV |

monkeypox virus |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| PHEIC |

Public Health Emergency of International Concern |

| NAAT |

Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| INSA |

National Institute of Health Doutor Ricardo Jorge |

| UREB |

Emergency Response and Biopreparedness Unit |

| Ct |

Cycle threshold |

| MSM |

Men who have sex with men |

| NUTS |

Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics |

References

- Antunes F, Cordeiro R, Virgolino A. Monkeypox: From a neglected tropical disease to a public health threat. Infect Dis Rep. 2022, 14, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitjà O, Ogoina D, Titanji BK, et al. Monkeypox. Lancet. 2023, 401, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Mpox Trends. April 4, 2025. Accessed April 7, 2025. Available online: https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/mpx_global/.

- World Health Organization. Multi-country outbreak of mpox. External situation report #49. March 28, 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/multi-country-outbreak-of-mpox--external-situation-report--49---28-march-2025.

- World Health Organization. Diagnostic testing and testing strategies for mpox: Interim guidance. 12 November 2024. [CrossRef]

- Shchelkunov SN, Shcherbakov DN, Maksyutov RA, et al. Species-specific identification of variola, monkeypox, cowpox, and vaccinia viruses by multiplex real-time PCR assay. J Virol Methods. 2011, 175, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GraphPad QuickCalcs [Internet]. Accessed April 7, 2025. Available online: https://www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/contingency1/.

- Cordeiro R, Pelerito A, de Carvalho IL, et al. An overview of monkeypox virus detection in different clinical samples and analysis of temporal viral load dynamics. J Med Virol. 2024, 96, e70104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Monkeypox cases reported in UK and Portugal. May 19, 2022. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/monkeypox-cases-reported-uk-and-portugal.

- Perez Duque M, Ribeiro S, Martins JV, et al. Ongoing monkeypox virus outbreak, Portugal, 29 April to 23 May 2022. Euro Surveill. 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro R, Pelerito A, de Carvalho IL, et al. Undetected circulation of monkeypox virus in Portugal estimated via mathematical modelling: Evidence for a 50-day gap before first detection. Submitted for publication.

- Borges V, Perez Duque M, Martins JV, et al. Viral genetic clustering and transmission dynamics of the 2022 mpox outbreak in Portugal. Nat Med. 2023, 29, 2509–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordeiro R, Caetano CP, Sobral D, et al. Viral genetics and transmission dynamics in the second wave of mpox outbreak in Portugal and forecasting public health scenarios. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2412635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- León-Figueroa DA, Barboza JJ, Saldaña-Cumpa HM, et al. Detection of monkeypox virus according to the collection site of samples from confirmed cases: A systematic review. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2022, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heskin J, Belfield A, Milne C, et al. Transmission of monkeypox virus through sexual contact: A novel route of infection. J Infect. 2022, 85, 334–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Direção-Geral da Saúde, Centro de Emergências em Saúde Pública. Mpox em Portugal e no Mundo - Informação a 28 de fevereiro de 2025. Available online: https://www.dgs.pt/saude-a-a-z.aspx?v=%3d%3dBAAAAB%2bLCAAAAAAABABLszU0AwArk10aBAAAAA%3d%3d#saude-de-a-a-z/monkeypox/informacao-semanal.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).