This section considers the mechanisms that contribute to the photomechanical response, starting with heating, hole burning/re-orientation and ends in photomechanical efficiencies quantified by a figure of merit. The response times of the processes are evaluated and connected to the mechanisms.

5.1. Photomechanical Response

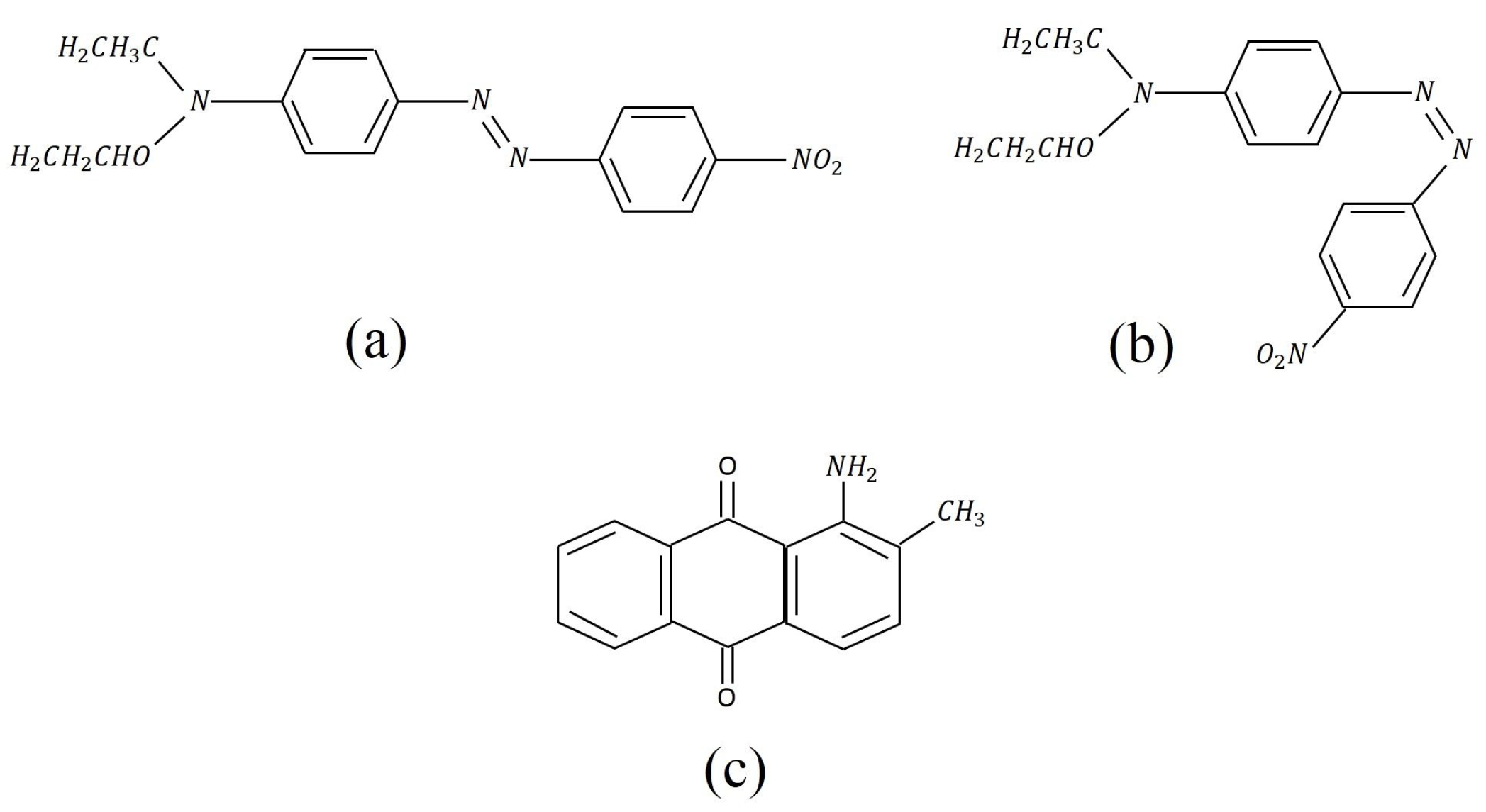

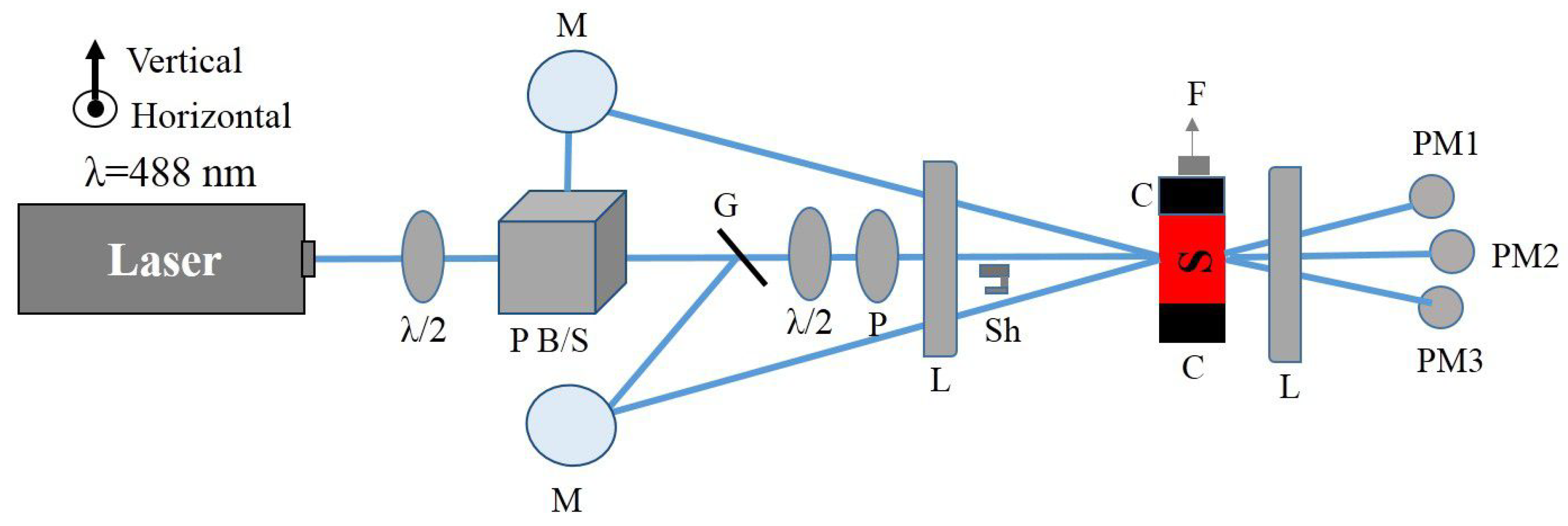

Comparisons of light-induced stress and absorbance in DR1 and DO11 doped PMMA thin films can be used to deduce the mechanisms of the photomechanical response in photo-isomerizable samples. The entire area of the sample is illuminated by the pump in a 15 second on and 15 second off cycle. After multiple repetitions, the intensity is increased and the protocol repeated. Typically, the experiment cycles through fifteen different intensities.

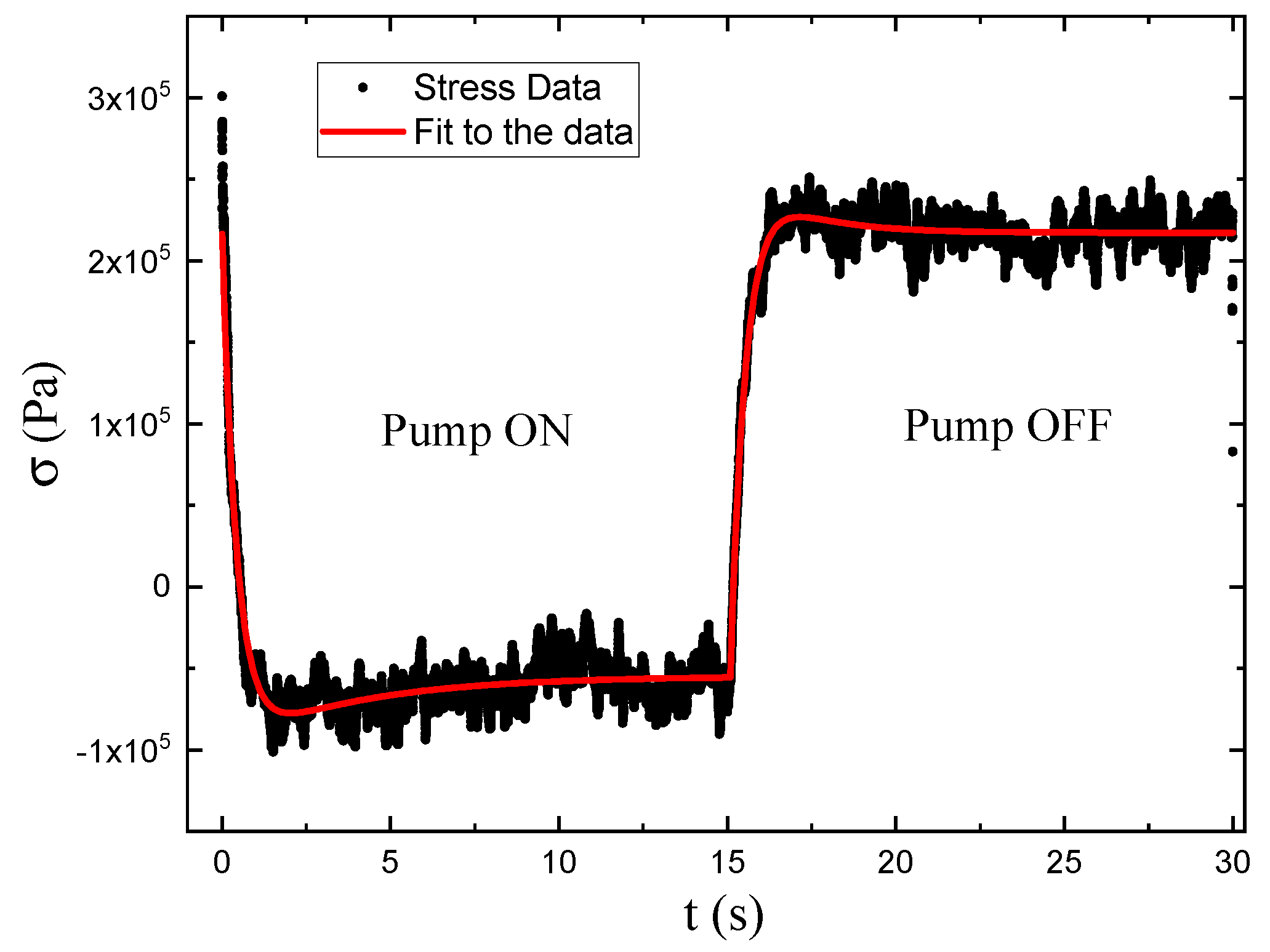

As shown in

Figure 4, the photomechanical stress response as a function of time for fixed pump intensity follows a bi-exponential function of the form given by Equations

2and

3 The data are fit to the model with a time offset of

to determine the time constants and amplitudes.

One parameter of interest is the long-time stress response

, where

and

come from the fits to the data. These are plotted in

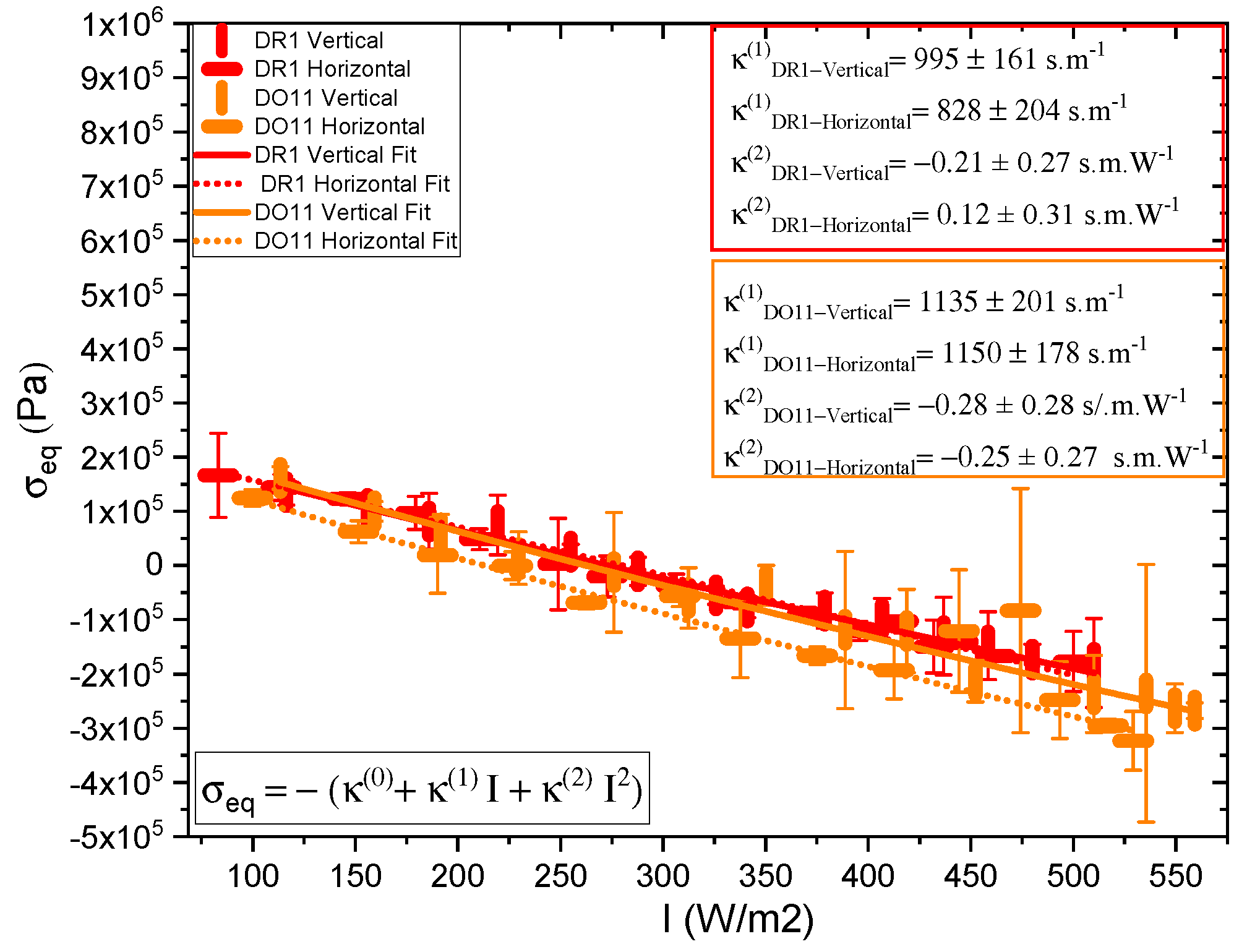

Figure 5. The data for each polarization are fitted to a quadratic polynomial which is in the form of Equation

1, and it shows that

I is large compared to

over the data range, so the stress response is linear within fractional deviations of 0.02 and 0.13 for DR1 and 0.05 and 0.12 for DO11 with horizontal and vertical polarizations of light, respectively, where the fractional deviation is given by

at the highest measured intensity.

The linear photomechanical constant is the same within experimental uncertainty for both pump polarizations, i.e.

, in DR1 and in DO11. This observation is as expected in DO11, which has only one conformation so should be dominated by photothermal heating alone, a process that is polarization-independent. However, since DR1 is known to photo-isomerize [

1,

3] – which leads to angular hole burning,[

1,

3,

27,

28,

29] the data suggest that the light-induced change in the molecular orientational distribution function does not translate into a large-enough photomechanical response to be detectable within experimental uncertainties relative to the dominating photothermal heating mechanism. In addition, the magnitudes

and

of DO11 and DR1 agree with each other within experimental uncertainty, strengthening the conclusion that the mechanism of the response is the same in both materials. However, as seen in

Figure 5, the horizontal polarization data for DR1 dye is systematically lower than the vertical polarization data and at the edge of experimental uncertainty, allowing for a small contribution from a mechanism that is not found in DO11. This could originate from photoisomerization.

Figure 5.

Photomechanical response of DR1 and DO11 thin films for horizontal and perpendicular polarization of light as a function of intensity.

Figure 5.

Photomechanical response of DR1 and DO11 thin films for horizontal and perpendicular polarization of light as a function of intensity.

The sections below describe how one isolates each mechanism by controlling individual experimental parameters such as temperature and intensity while monitoring the stress and transmitted probe intensity.

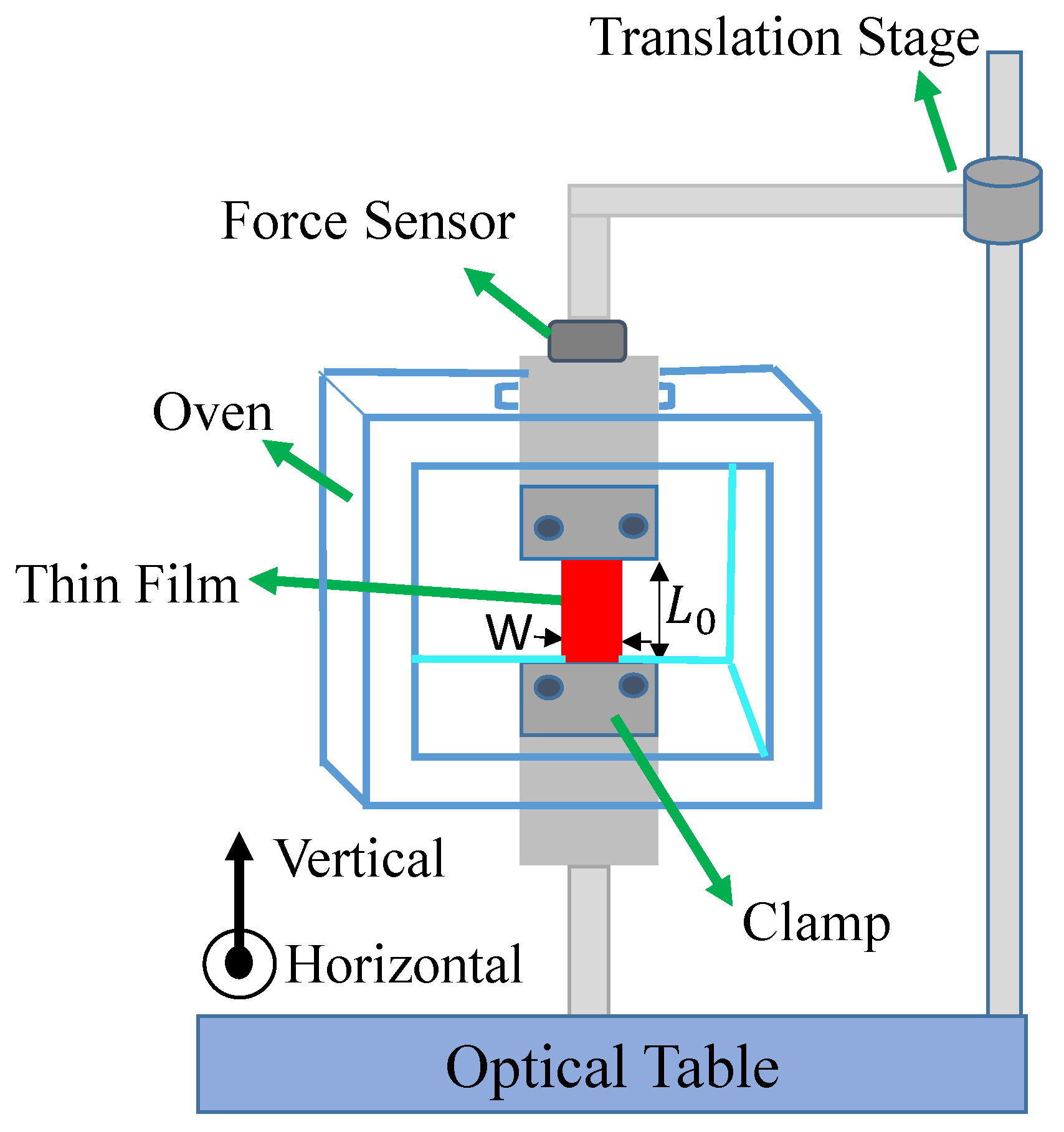

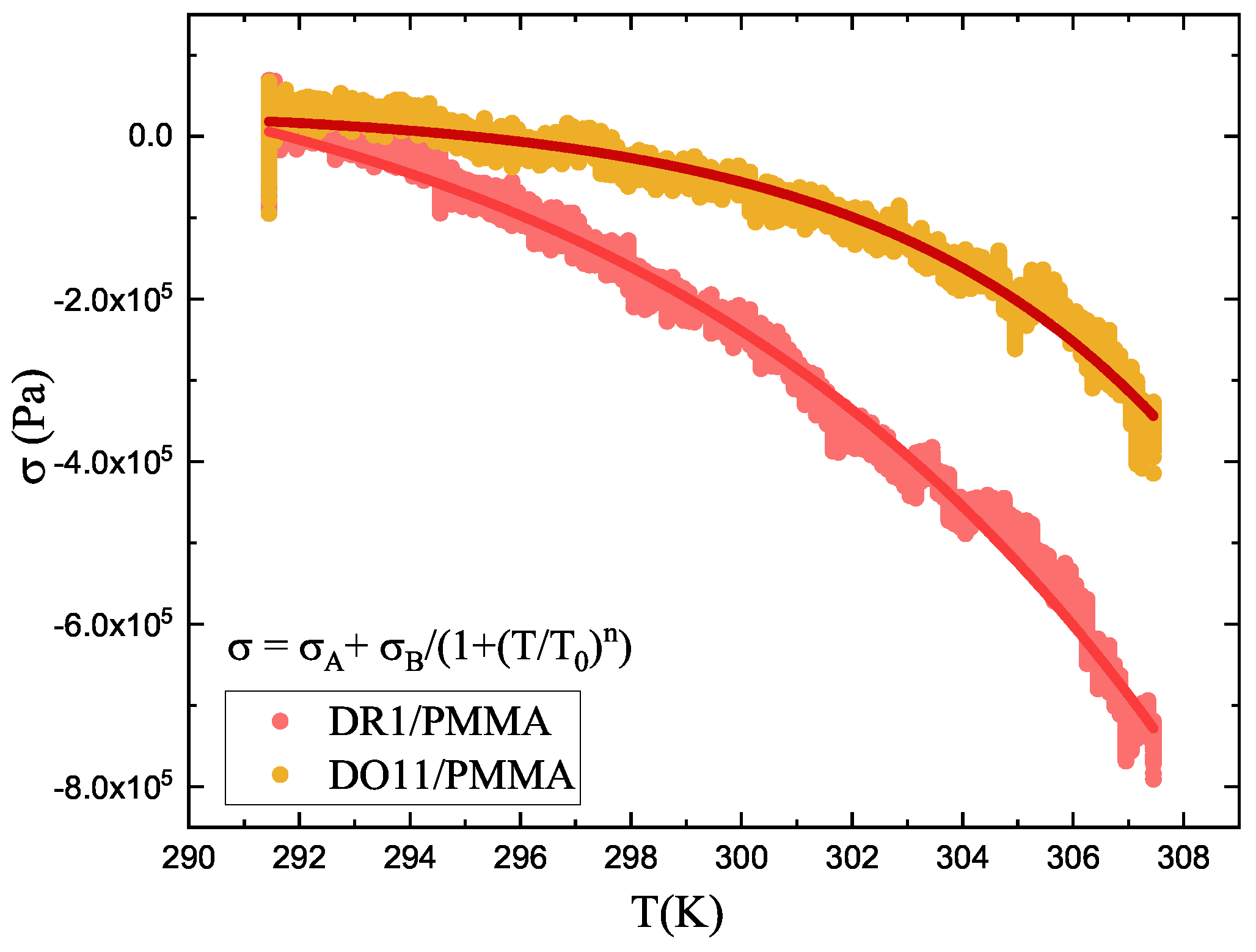

5.1.1. Heating

DR1 and DO11 thin films are studied by measuring the stress of a clamped sample as a function of temperature while heating them in an oven from 291.15K to 307.15K over a time span of 3 minutes. The result is shown in

Figure 6. The data are fit to Equation

4 and the fitting parameters are shown in

Table 1.

Equation

9 has the parameters

n,

and

that are determined from fits to Equation

4 to temperature-dependent stress data as shown in

Figure 6.

T is the temperature of the sample prior to illumination and

is the time constant of heating, which can be determined theoretically from the geometry of the material or imperially from the measured stress as a function of time.[

31]

The time constant can depend on the intensity of the pump beam, which gives its dependence on intensity.

5.1.2. Hole Burning and Photo-Stress Anisotropy

Table 2 summarizes the parameters determined from fits to the data shown in

Figure 5 for thin films. For comparison, also shown are the values for dye-doped fibers.[

24] The positive sign of

in both materials and in both thin films and fibers, indicates that photothermal heating drives expansion. The ratio of the hole burning to the heating response,

R, vanishes within experimental uncertainty, confirming that photothermal heating dominates in thin films and fibers. In DO11

and

are expected to be zero, because DO11 is nonisomerizable, and the results show this to be true with a high degree of confidence. So we conclude that angular hole burning and molecular re-orientation are absent in DO11. DR1 shows a larger contribution from angular hole burning, and the signs of the coefficients are what is expected, but vanish within experimental uncertainty. The sign of

indicates that the length of the sample along the light’s polarization decreases and the positive sign of

shows that the length of the sample increases along its long axis when it is illuminated by light perpendicular to it,[

1,

24] as would be expected. But again, the values are statistically insignificant so angular reorientation and hole burning are negligible.

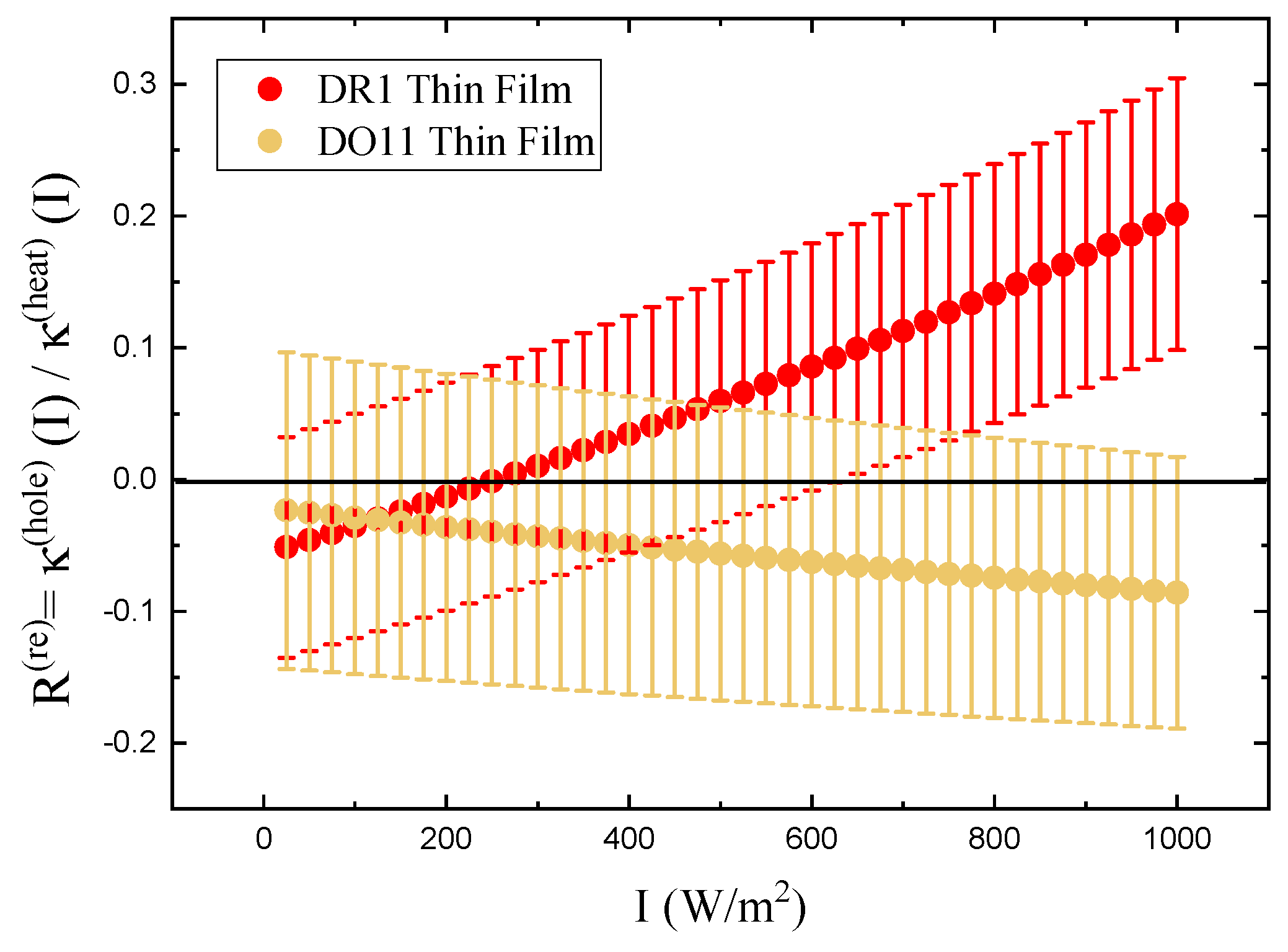

To make sure that the response is linear and we are in the low-intensity regime, the ratio

R as a function of intensity is also calculated for both samples.

R is found using Equation

26.

Figure 7 shows a plot of the relative reorientational fraction

R as a function of intensity, where we have evaluated

and

in Equation

26 using the values of

,

,

, and

determined from the slopes in

Figure 5 to get the points at each intensity

I. The error bars are propagated from the measured uncertainties in

,

,

, and

. The ratio varies more over the intensity range measured for DR1 than for DO11. The ratio

R for DR1 appears to change sign at low intensity, but this sign change is in the noise given the uncertainties. The increase of

R for DR1 is statistically significant, suggesting that hole burning becomes a significant fraction of the response mechanisms at the highest intensities.

While the behavior of the thin films and fibers is similar, the linear photomechanical constants are a factor of 3 to 4 times larger in the thin films.

5.2. Evolution of Molecular Orientation

Section 5.1 describes how the photomechanical effect depends on the various mechanisms. Here we focus on measurements that directly determine the orientational order of the dopant molecules in the PMMA polymer host, which can be correlated with the photomechanical response to assess if the orientational order couples mechanically to the polymer and that it contributes to photomechanical actuation.

The transmitted and incident intensities are recorded using a power meter with and without a sample. From these, the optical absorption coefficient of the sample is determined for the two orthogonal polarizations using the Beer-Lambert law [

1,

24]

where

and

and

are the absorbance parallel and perpendicular to the polarization of the pump beam, respectively.

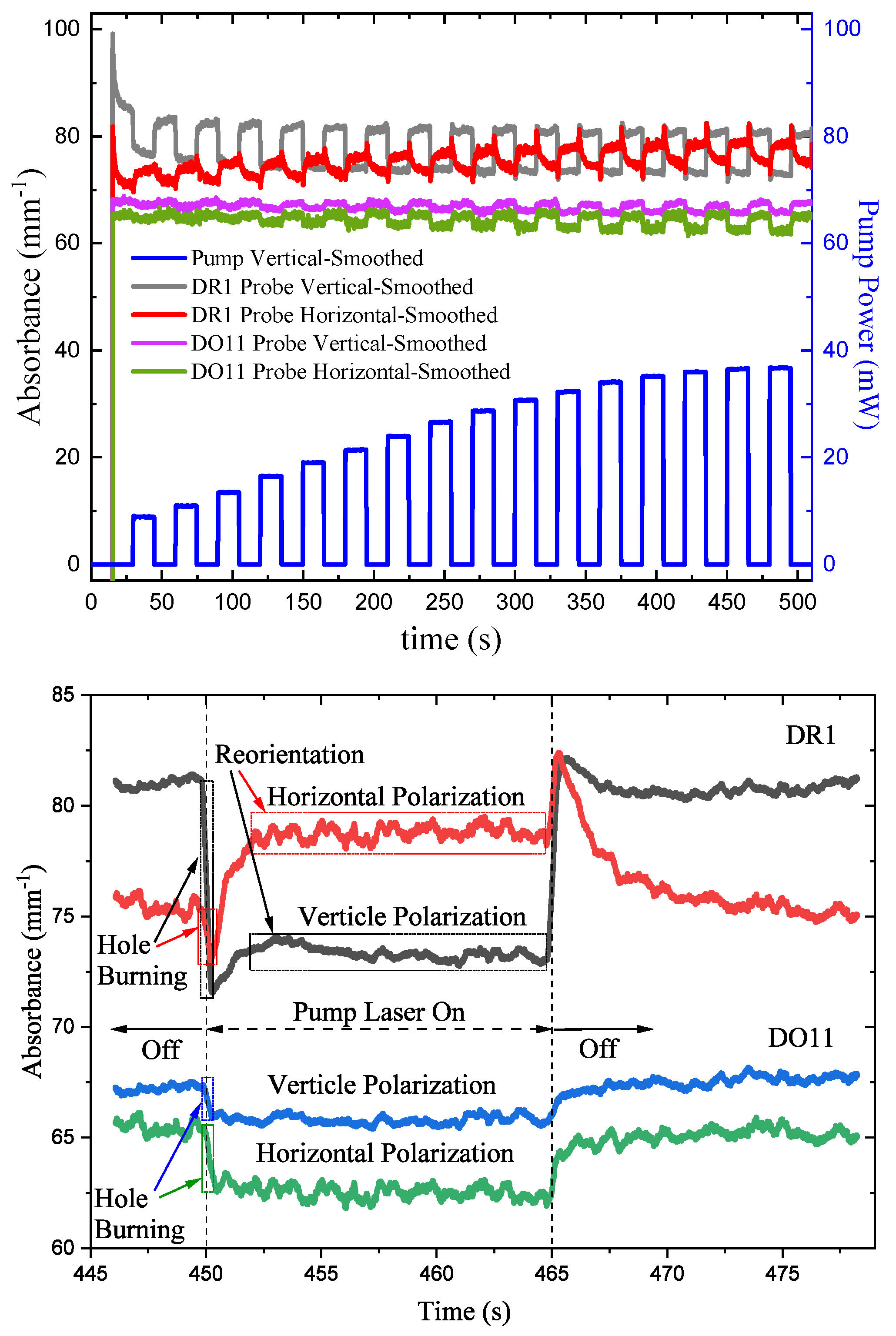

Figure 8(top) shows the absorbance for vertically- and horizontally-polarized probe beams in DR1- and DO11-doped PMMA thin films.

Figure 8(bottom) shows a close-up view of one cycle in a region where transients from the probe lasers being turned on have subsided. For DR1, the vertically-polarized pump induces a fast increase in the intensities of both probe polarizations as shown by the decreased absorbance. At later times with the pump on, the intensity of the horizontally-polarized probe beam decreases (increased absorbance) while the vertically-polarized probe beam shows little change.

This fast behavior can be understood as follows. Irradiating DR1 molecules with vertically-polarized light preferentially excites the vertically-oriented chromatophores. In the argument here, we assume that DR1 absorbs less light in its excited state and the molecules are one-dimensional, which has been shown to be a good approximation.[

32] The probability of exciting a chromophore that is oriented an angle

relative to the pump polarization is proportional to

, making it most probably to excite vertically-oriented molecules at

and improbably in the horizontal direction, where

. The probability of a molecule absorbing vertically-polarized probe light is proportional to

, making the probability of absorbing vertically-polarized probe light in the presence of the vertically-polarized pump beam is proportional to

. Similarly, since the probability of absorbing horizontally-polarized light is proportional to

, the probability of absorbing horizontally-polarized probe light in the presence of a vertically-polarized pump is proportional to

.

Finally, assuming that the sample is isotropic – which it should be based on the material’s processing conditions, the ratio of the change in absorbance for the two polarization for an initially isotropic sample is given by the orientational average ratio

Equation

31 implies that the drop in the vertically-polarized probe is greater than the horizontal one, and that they both should drop.[

1,

24]

Figure 8(bottom) shows this to be true for DR1. DO11, on the other hand, also shows a drop in the absorbance for both polarizations, but the one-dimensional approximation does not hold as well for DO11. In both cases, we see a drop in the absorbance due to the pump light exciting the molecules. This effect is labelled “hole burning" because the orientational distribution function takes on a shape like the dimple in an apple. Note that the probe beam intensities are much lower than the pump, so their affect on the excited populations should be minimal.

Another fast process is photothermal heating, which increases the temperature of the material as the absorbed light is converted to heat. Since the trans isomer is of lower energy than the cis isomer, the trans population drops and the cis population increases at higher temperatures, leading to an isotropic decrease in the absorbance of light by virtue of the cis molecule’s slow absorption cross-section. Thus isotropic heating will lower the absorbance of both polarizations equally. The fast component will thus be a combination of both heating and hole burning.

At longer time scales, molecules that undergo photo-isomerization will reorient into the horizontal direction, as we would expect; when molecules aligned along the light’s polarization turn into the smaller cis state, they re-orient randomly due to diffusion and on average end up in the perpendicular orientation once they decay back to the trans state.[

3,

24] This decreases the vertical absorbance because fewer molecules are aligned with the pump beam and increases the horizontal absorbance where there are more molecules. The horizontal probe sees an increase in absorbance as we would expect. Similarly, the long-time vertical probe sees a decrease in the absorbance, as expected. At an intermediate time between the fast hole-burning process and the slow molecular reorientation process, another feature is observed where both probe polarizations show an increase in absorbance. The region’s time scale includes the photothermal heating mechanism, which can change the relative populations between the cis and trans isomers. Separating the mechanisms to this level of detail is beyond the scope of this work, but it is worth mentioning that the three mechanisms can couple to produce complex behavior, which is difficult to model.

DO11 thin films show a decrease in absorption for both polarizations in response to the pump and an increase when the pump is turned off. The DO11 molecule is known to transition from the keto to the enol state when excited by a photon. Optical absorption of the enol state is weaker, so the absorbance decreases when the pump is on. The DO11 molecule relaxes back to the keto state when the pump is turned off,[

25,

33] leading to an increase in the absorbance.

In both DR1 and DO11 molecules, the time dependence of the absorbance when light is turned off is the reverse of the process when the light is turned on. In the case of DR1, where there are multiple exponential processes that contribute amplitudes of opposite signs, the process as left-right anti-asymmetric while the DO11 process is left-right symmetric. Note that for both cases, flipping the pump-off absorbance data about the horizonal axis and shifting it by 15 seconds give the same qualitative shape.

The difference in the absorbance measured by the two orthogonal probe lasers can be used to find the axial orientational order parameter

. For molecules that are approximately one-dimensional, the order parameter is given by [

25,

29]

The order parameter

if the long axes of the molecules are fully aligned and

when they are randomly aligned. The order parameter can be negative when the molecules lie flat in the plane perpendicular to the symmetry axis.

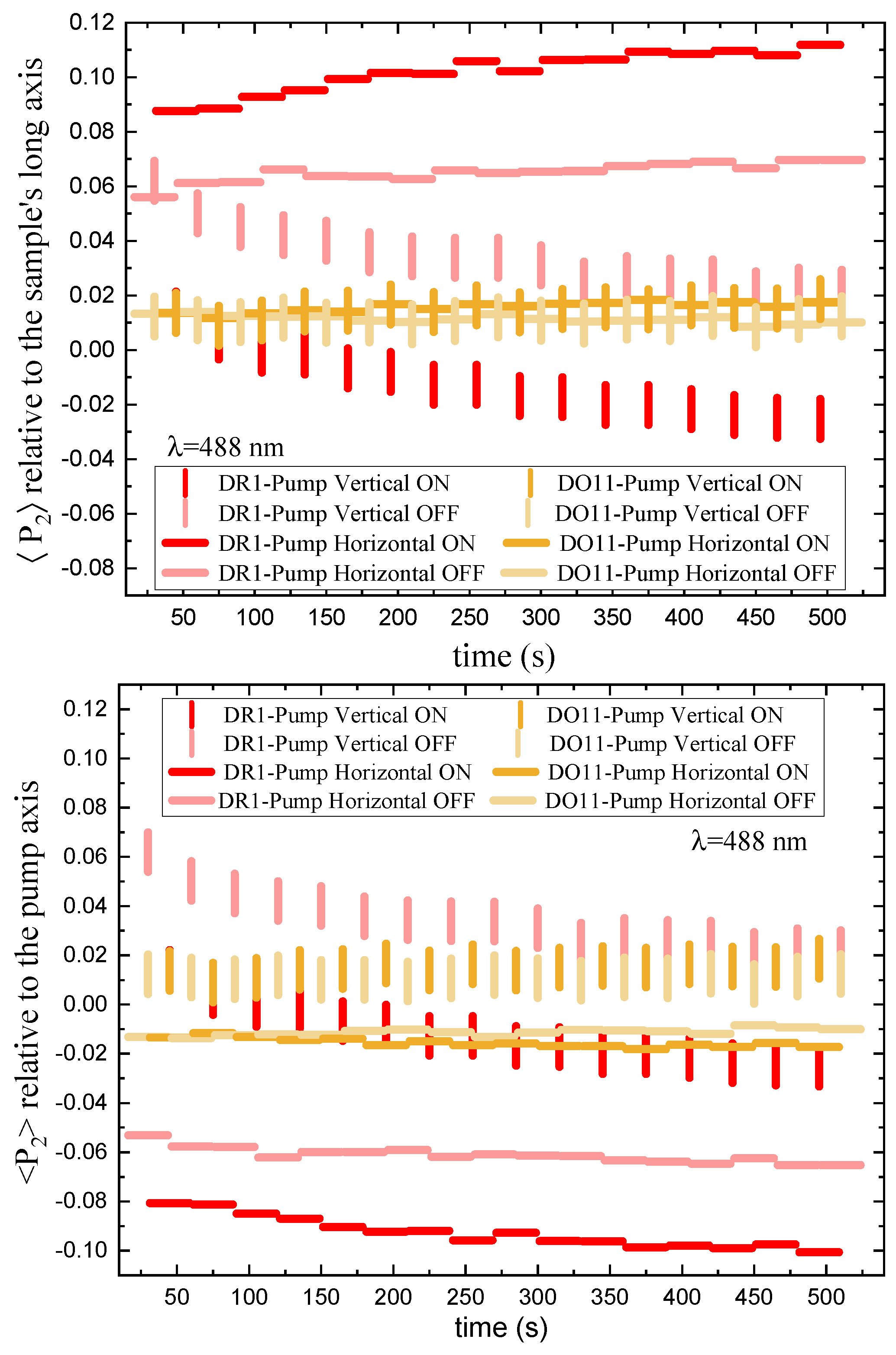

The order parameter relative to the sample’s long axis, mounted vertically, as a function of time and intensity, is shown in

Figure 9 for vertically and horizontally polarized pump light. The top plot references the order parameter to the long axis of the sample while the bottom plot is relative to the pump axis.

Order parameter relative to long axis of sample: We first consider the top plot of

Figure 9, which references the order parameter to the long axis of the thin film sample. The long axis is always mounted vertically. Turning the pump on and off for both polarizations does not affect the order parameter in DO11 – as expected when photo-isomerization is absent. In contrast, for DR1, a

vertically-polarized pump decreases the order parameter along the film’s long axis (vertical) and turning the pump off results in an increase of this order parameter back to its pre-pumped state. A

horizontally-polarized pump increases the order parameter, which decreases reversibly when the pump is turned off. This behavior is expected if the pump light that is polarized along the trans molecule’s long axis excites the cis state, making a “hole" along the light’s polarization direction by depleting those trans molecules. Subsequently, the number of molecules in the perpendicular orientation increases as the cis molecules relax back to the trans state and take on random orientation, but leaving a net depletion along the pump’s polarization.

Order parmater relative to pump polarization axis: The bottom part of

Figure 9 shows the order parameter relative to the pump’s polarization axis. For an isotropic sample, the order parameter in a dark sample should vanish and the order parameter in the presence of pump light should be the same for both polarizations if their intensities are the same. The data shows that the order parameters are not the same for the two polarizations, so the samples are not isotropic. There are several possible sources of this anisotropy, including the fact that the sample are slightly stretched in the vertical direction when mounted in the sample holder. This is consistent with the observation that a vertical pump polarization has a slight positive order parameter while the horizontal one has a negative order parameter. In both cases, the presence of the pump leads to a decrease in the order parmater, as expected for molecular reorientation.

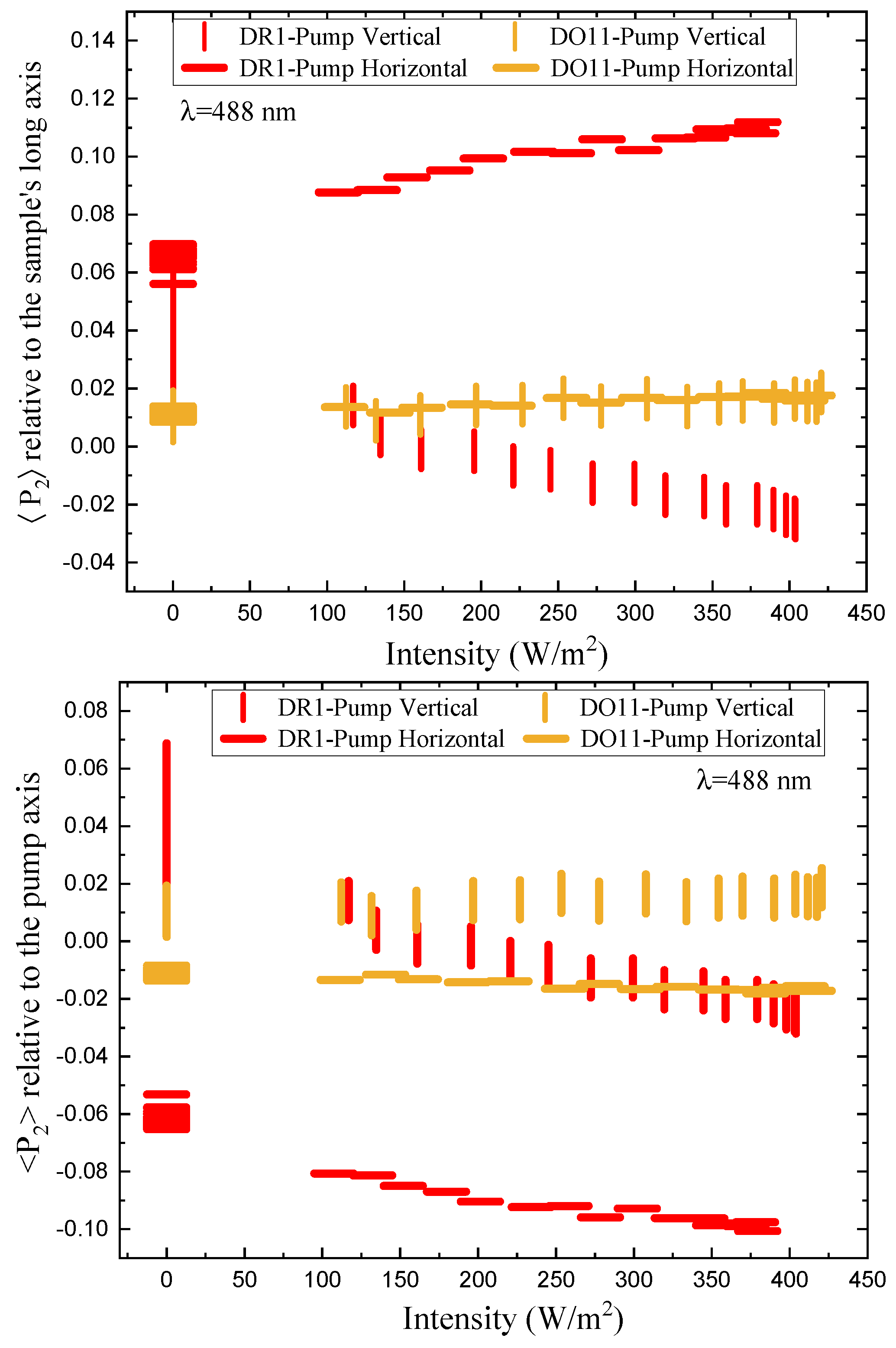

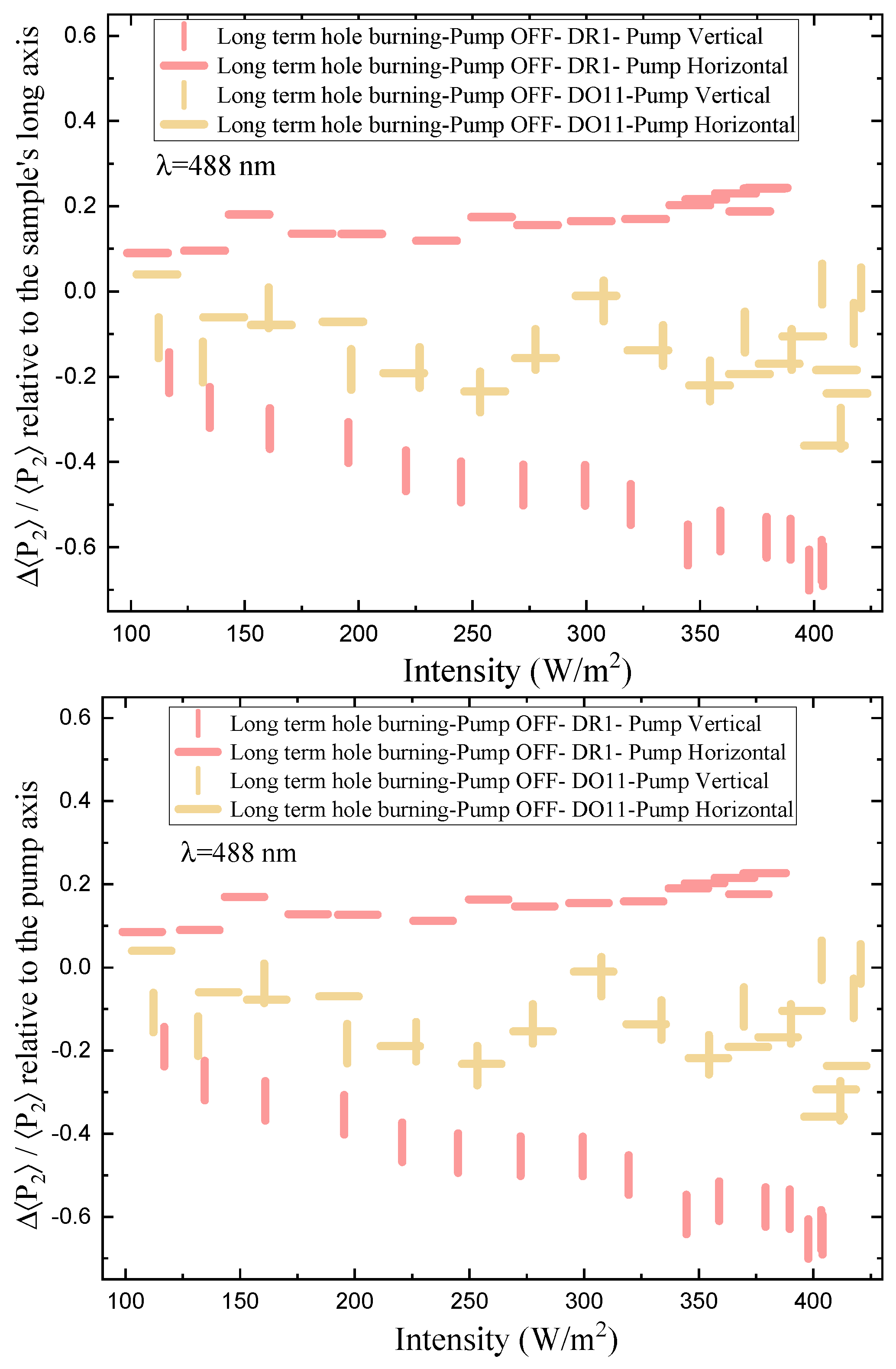

Figure 10 shows the same data as in

Figure 9, but as a function of pump power. Because the samples are slightly anisotropic, the behavior is made clearer by considering the change in the order parameter relative to the dark state. This change in the order parameter

is given by

where

is the order parmater when the pump intensity is

I and

is the order parameter of the material prior to the start of the experiment. We call

the total order parameter change because it includes the change in order parameter due to the instantaneous pump power as well as the accumulated order parameter from all past exposure due to the fact that the dye molecules have not had the change to relax to the isotropic state during the 14s period that the pump light is turned off. The low levels of probe light might also add to the cumulative effect. The values of

at

include all the values determined when the pump light is off between measurements where the intensity is changed. If there were no cumulative effects of time as the pump intensity is increased, there would be only one point for each polarization and each material.

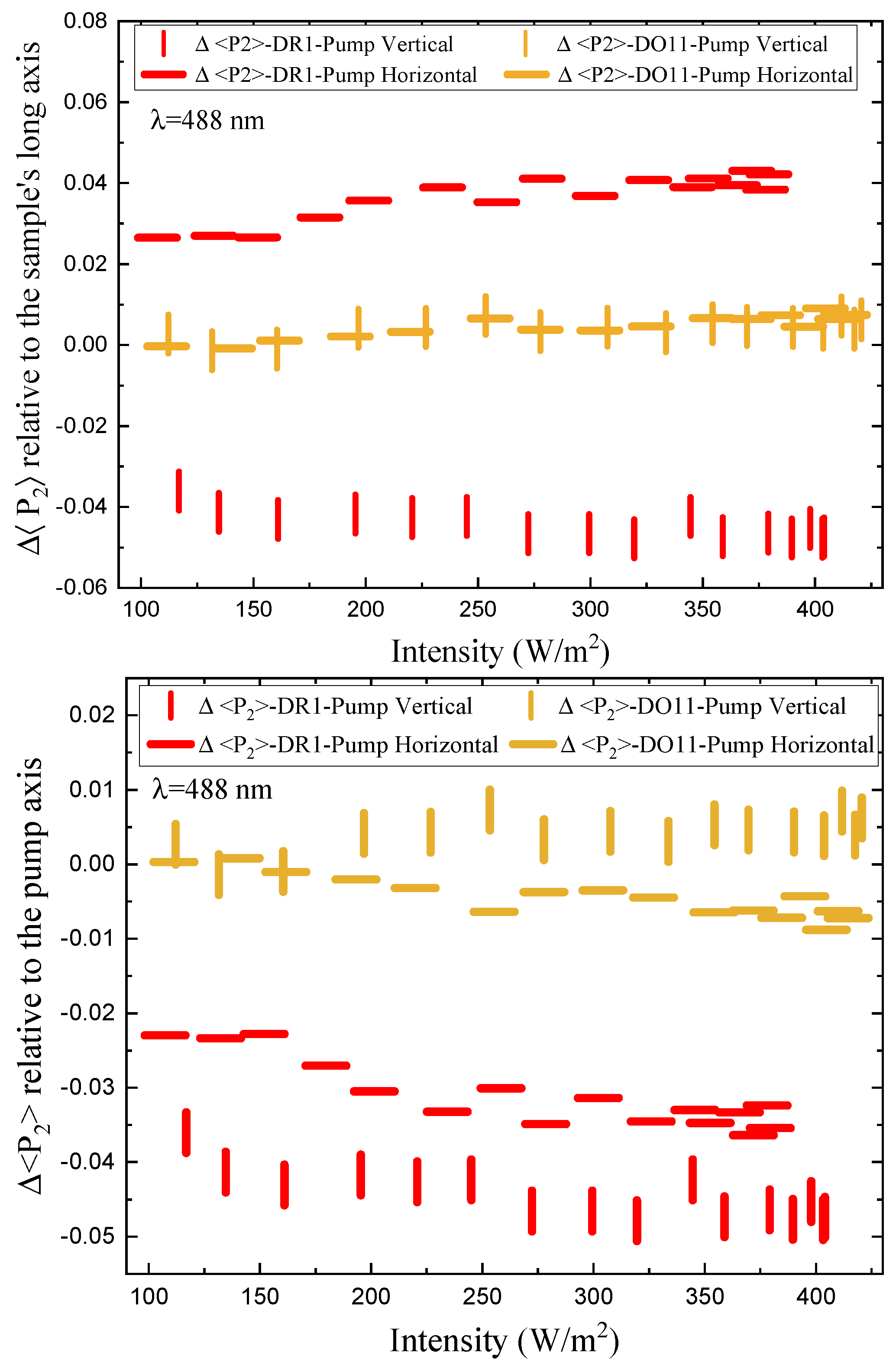

Figure 11 shows the order parameter change

as a function of absorbed intensity relative to the sample’s long axis (top) and the pump axis (bottom). For DO11-doped PMMA, the order parameter referenced to the long axis of the sample (top plot) shows no statistically significant change as a function of intensity, while DR1-doped PMMA shows a dramatic effect with the horizontal pump inducing an increase in order parameter and the vertical pump inducing a decrease. The decrease of order parameter for the vertical pump is of slightly larger magnitude than the increase induced by the horizontal pump. These observations are consistent with molecules re-orientating away from the light’s polarization and ending up in the plan perpendicular to the pump.

The order parameter referenced to the pump axis (bottom plot) shows a larger difference between the two pump polarizations for DO11 and a similar difference for DR1. But, the trend is the same; the order parameter drops in the direction of the pump polarization axis. The observation of a pump polarization-dependent change in the parameter suggests that the sample might be initially anisotropic. The change in the order parameter appears to saturate at higher intensities, which one would expect for a fixed population of molecules.

Next, we seek to understand the source of the anisotropy. The two obvious candidates are (1) anisotropy due to the slight stretching of the sample along its long axis from mounting strain and (2) long-time molecular re-orientation that builds over time if the dyes in the polymer do not have enough time to relax over the 15 second dark cycle when the pump is off. There may also be an effect due to the excitation of molecules due to the ever-present weak probe beams, whose small effects may accumulate over time.

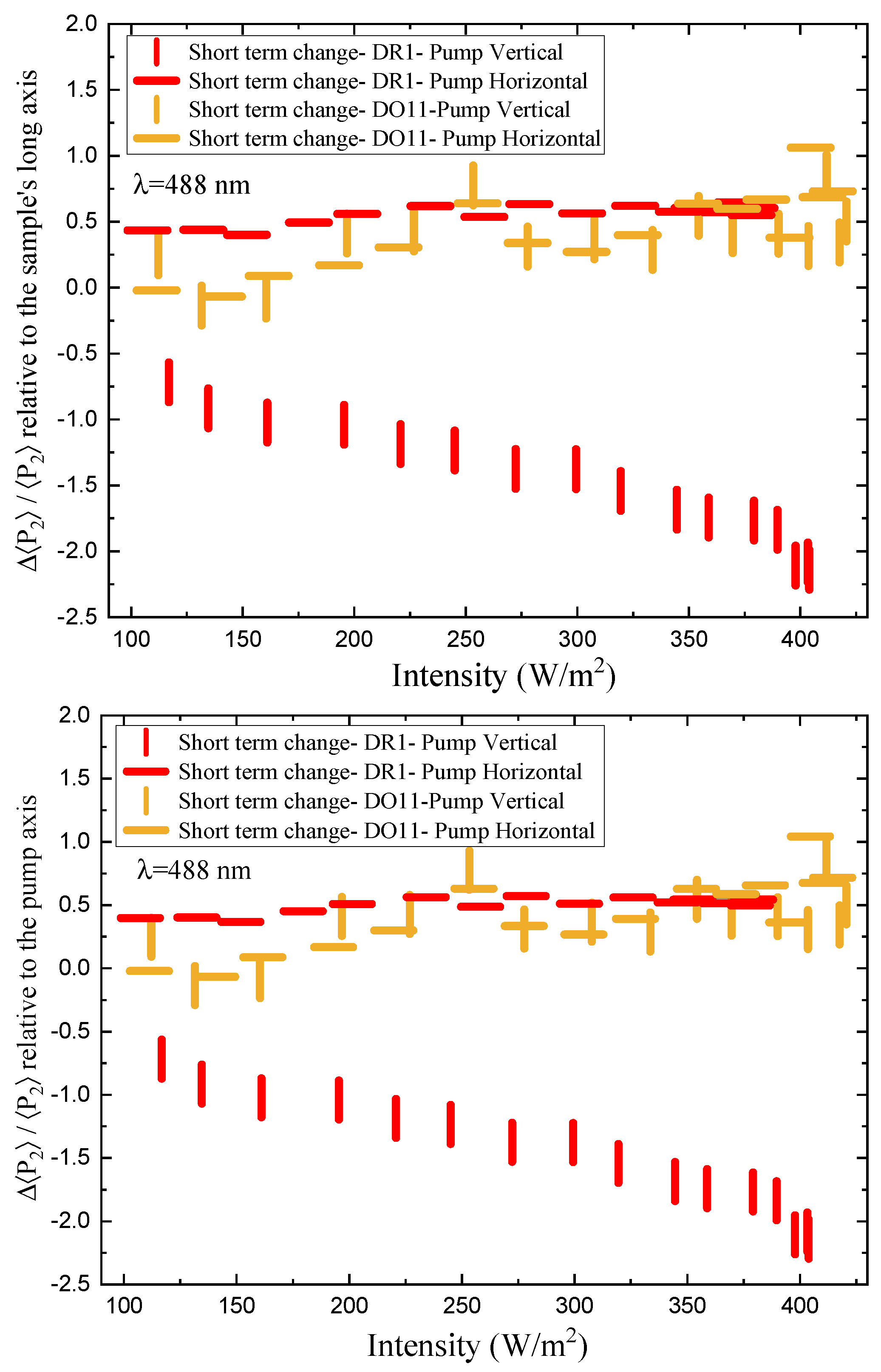

First we need to determine the change in order parameter due to the current pump cycle. This is best characterized by the short-time order parameter change, defined as the fractional change in the order parameter, which is normalized to the order parameter just before the pump is turned on during each cycle,

(n), given by

where

n labels the cycle number.

Figure 12 shows the short-time fractional order parameter change as a function of intensity relative to the sample’s long axis (top) and relative to the pump’s polarization axis for both vertically and horizontally polarized pumps. DO11 shows the same fractional order parameter change for both pump polarizations, which is consistent with the absence of molecular re-orientation. DR1, on the other hand, is consistent with molecular re-orientation in that the order parameter change relative to the long axis for a vertically-polarized pump is greater than for a a horizontally-polarized pump and of opposite sign. In the low-intensity regime, the ratio is about -2/3, as predicted by Equation

31. The ratio becomes smaller at higher-intensities, which is an indication that the sample is changing over time due to pump cycling and the effects of the probe beams. This does not preclude an intensity-dependent effect that originates in nonlinearities in the underlying mechanisms. Note that extrapolating the plots to zero intensity suggests clustering around a vanishing fractional order parameter change.

The long-term effects of the light on the sample can be assessed by comparing its properties at a given cycle with the sample prior to the first cycle. To this end, we define the long-term fractional change of the order parameter in the n

th cycle by referencing it to the order parameter of the sample at the start of the measurement. We start by determining the fractional change of the order parameter when the pump is off after the n

th cycle, given by

This will determine the change in the dark state of the sample in the presence of only the weak probe lasers. Doing the same for when the pump is on during the n

th cycle, we get

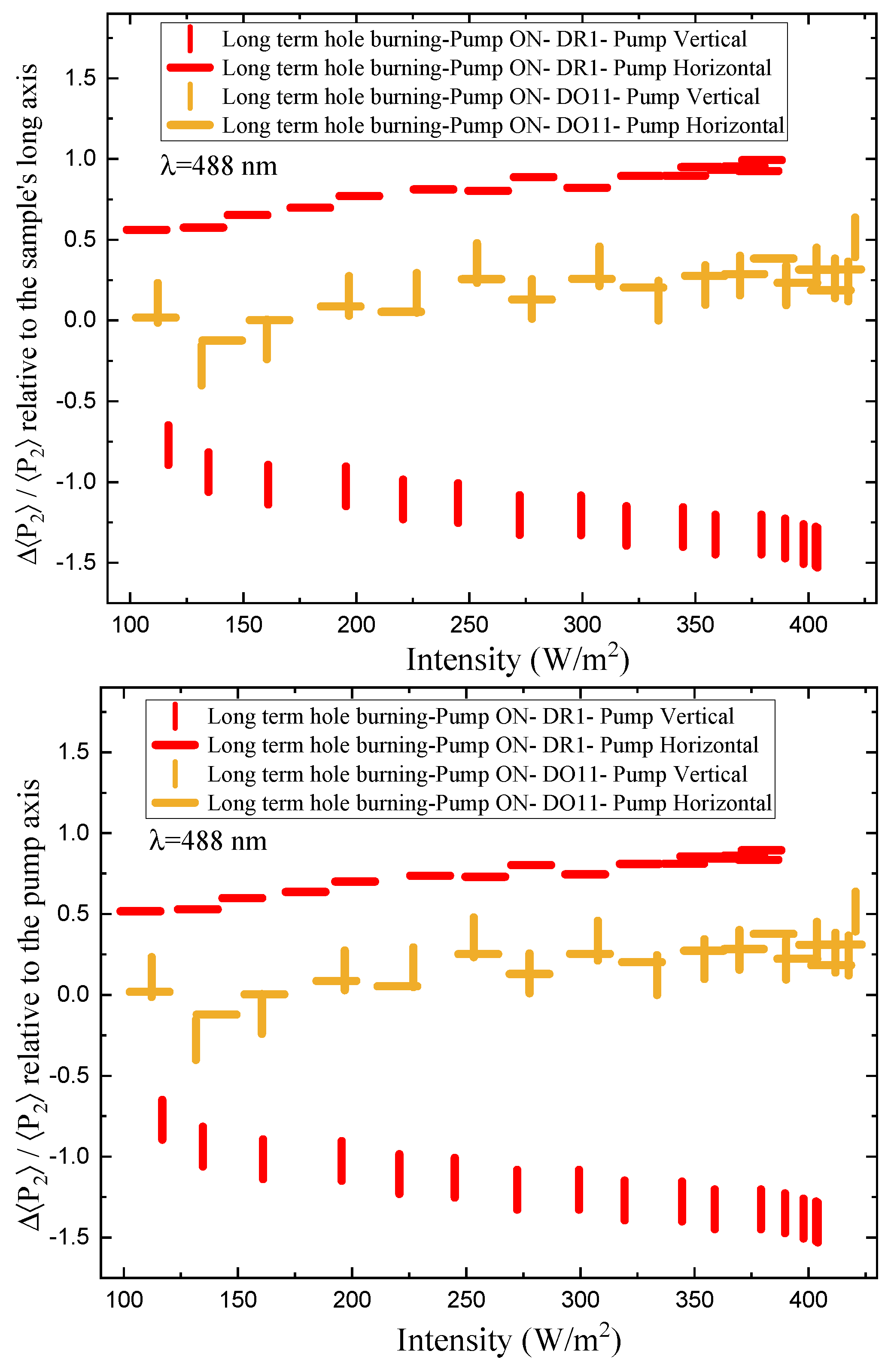

The long-term fractional change of the order parameter as a function of intensity when the pump is off and the pump is on relative to the pristine sample are shown in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14. The data clearly show that the dark state of the material (when pump is off but the probes are on), over the long-term span of the experiment, evolves over time. The fractional change of the vertically-referenced order parameter in DR1 decreases over time (and with increased pump intensity). This change is most likely a combination of the sample’s properties changing over time under the influence of the pump and probe beams as well as the increased pump intensities, which might produce a longer-lasting change in the materials properties. Similarly, when the pump is on, the vertically-referenced fractional order parameters decreases over time, but by a greater factor than the dark state. This is attributable to that fact that in the pumped state, the fractional change in the order parameter is influenced by both the long-term changes in the sample and the short-term effects of the pump.

Consider that the fast response shows an increase in the fractional order parameter change over time/intensity from about -0.75 to -2.25, the slow dark state changes from -0.3 to -0.65 and the slow pumped state changes from -0.75 to -1.3. At the lowest intensity and earliest times, there is already evidence of the dark state being anisotropic. At the highest intensity, the fast response shows the largest fractional change of the order parameter while the long-term response is somewhat lower, but by a statistically-significant amount. The long-term change in the fractional order parameter in the dark state is greater than the initial value, but still significantly smaller that the pumped state. Thus, the changes in the sample are enough to have a statistically significant effect on the measurements of the pumped state at high intensity, though not a large difference. Changes in the material from long-term light exposure might explain most of the small variations in DO11-doped PMMA thin films. However, the fractional change in the order parameter in DO11 is always similar for both pump polarizations, confirming that angular hole burning and re-orientation are insubstantial.

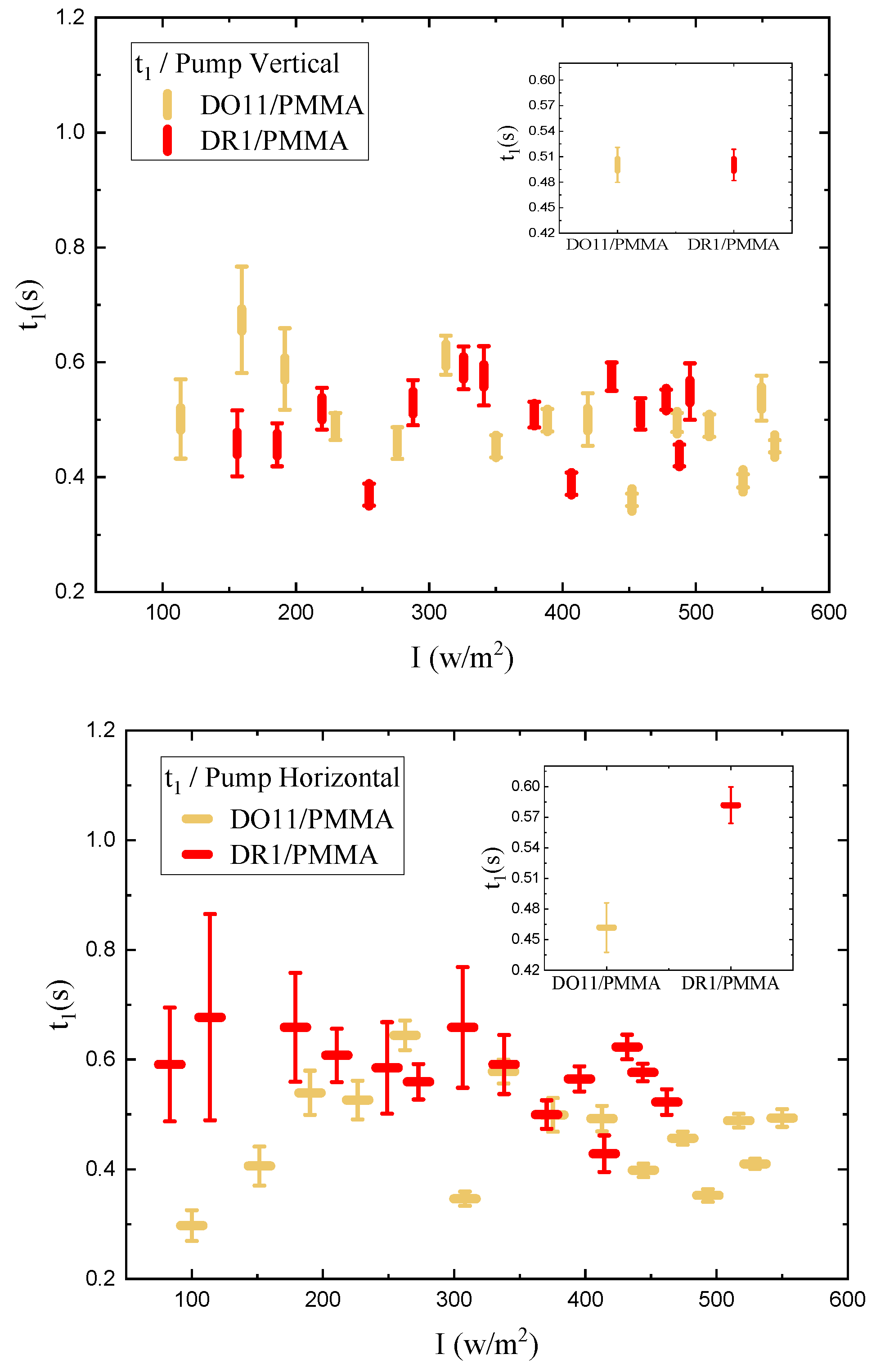

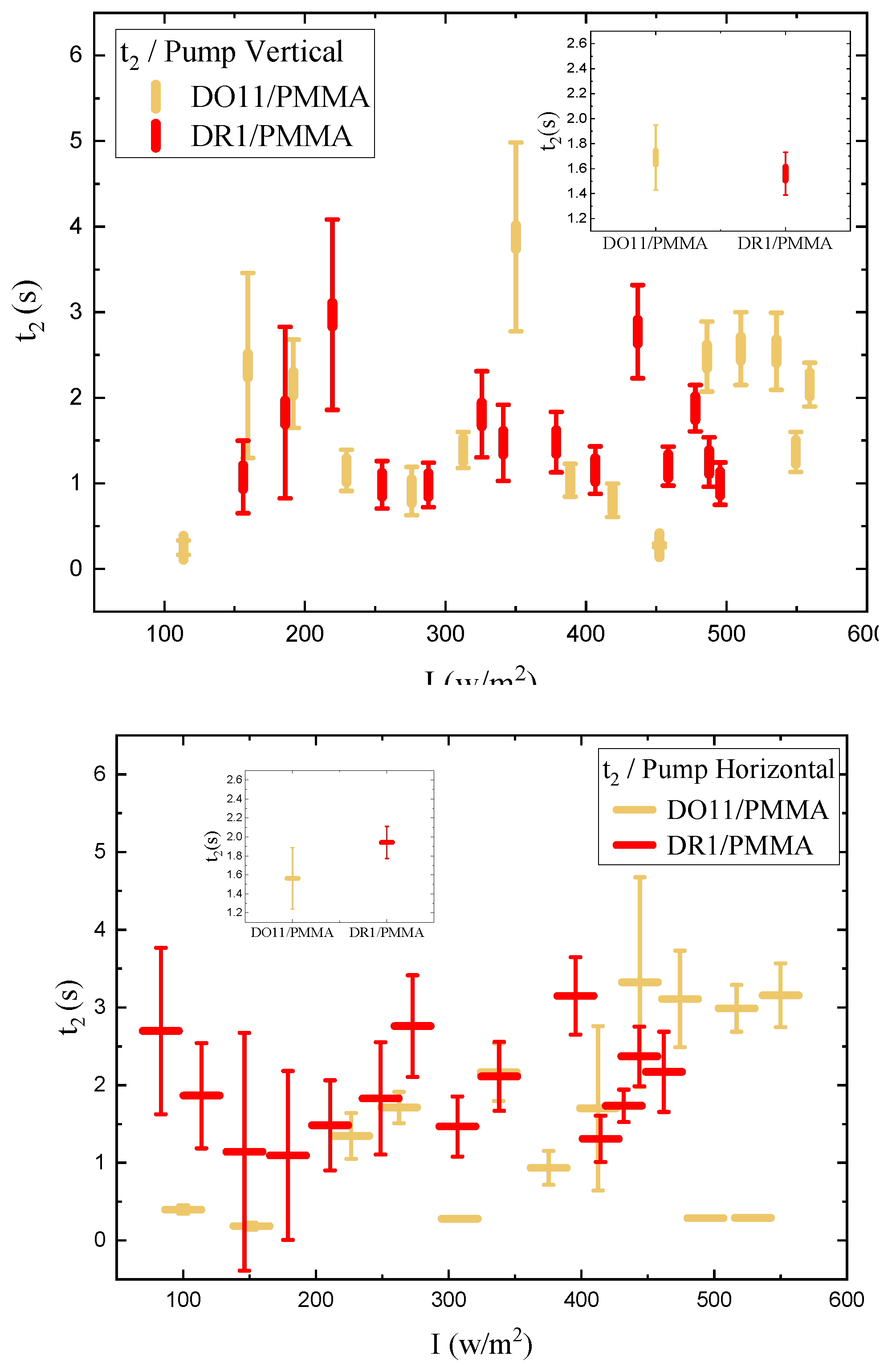

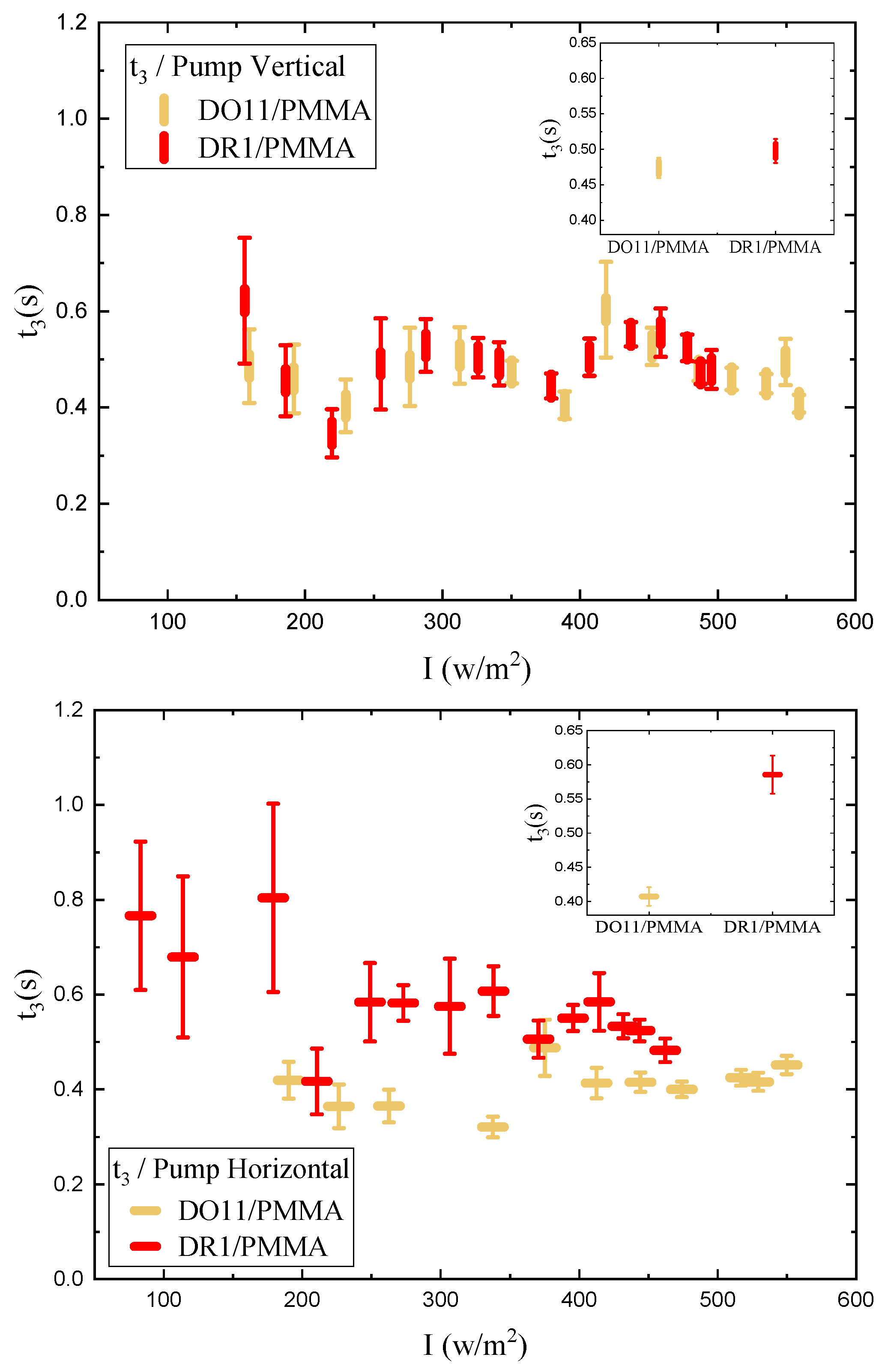

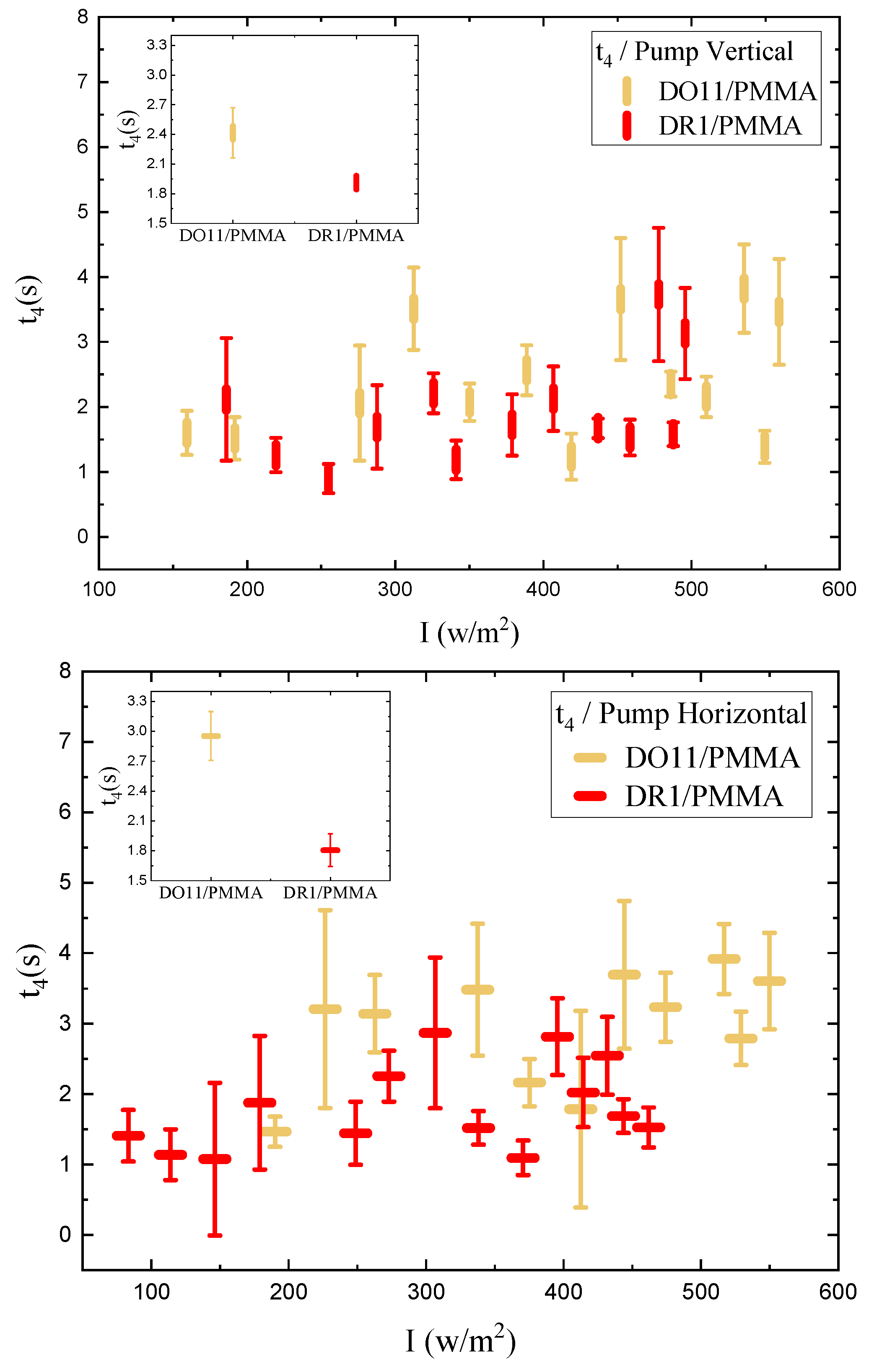

5.4. Photomechanical Time Response

We determine the photomechanical response times by fitting the time-dependent stress as shown in

Figure 4 to a double exponential when the pump is on and a separate double exponential when the pump is off. As a function of intensity, these fits give the intensity dependence of the magnitude and characteristic photomechanical time constants.

Figure 16 and

Figure 17 show the time constants for the photomechanical response while

Figure 18 and

Figure 19 show the relaxation time constants when the light is turned off for both DR1- and DO11-doped PMMA for both pump polarizations. The insets show the average time constant over the full intensity range for each material at each polarization.

While the fluctuations in the data exceed the error bar range, there is no obvious trend in the intensity dependence. The average of each run for a given sample and pump polarization shows that both the photomechanical response and its relaxation have two characteristic time constants that are about the same for each material. The fast time constant is about 0.5 s for both materials and for both the photomechanical response and the relaxation process. The longer time-scale process shows a different time constant for the pump on and off and range from about 1.5s for pumped response to 3 s during relaxation.

In contrast, fibers from previous studies display a single time constant for both decay and recovery between about 0.7 s and 1.0 s.[

24] This suggests that the underlying processes in the two sample geometries may be different, which might originate in the surface skin effect, where in thin films, the skin is a much larger fraction of the total volume than in fibers. As such, the thin film measurements reported here most likely are probing a regime where the skin contributes a large fraction of the total response, thus showing two unique processes while the fiber measurements are mostly probing bulk effects.

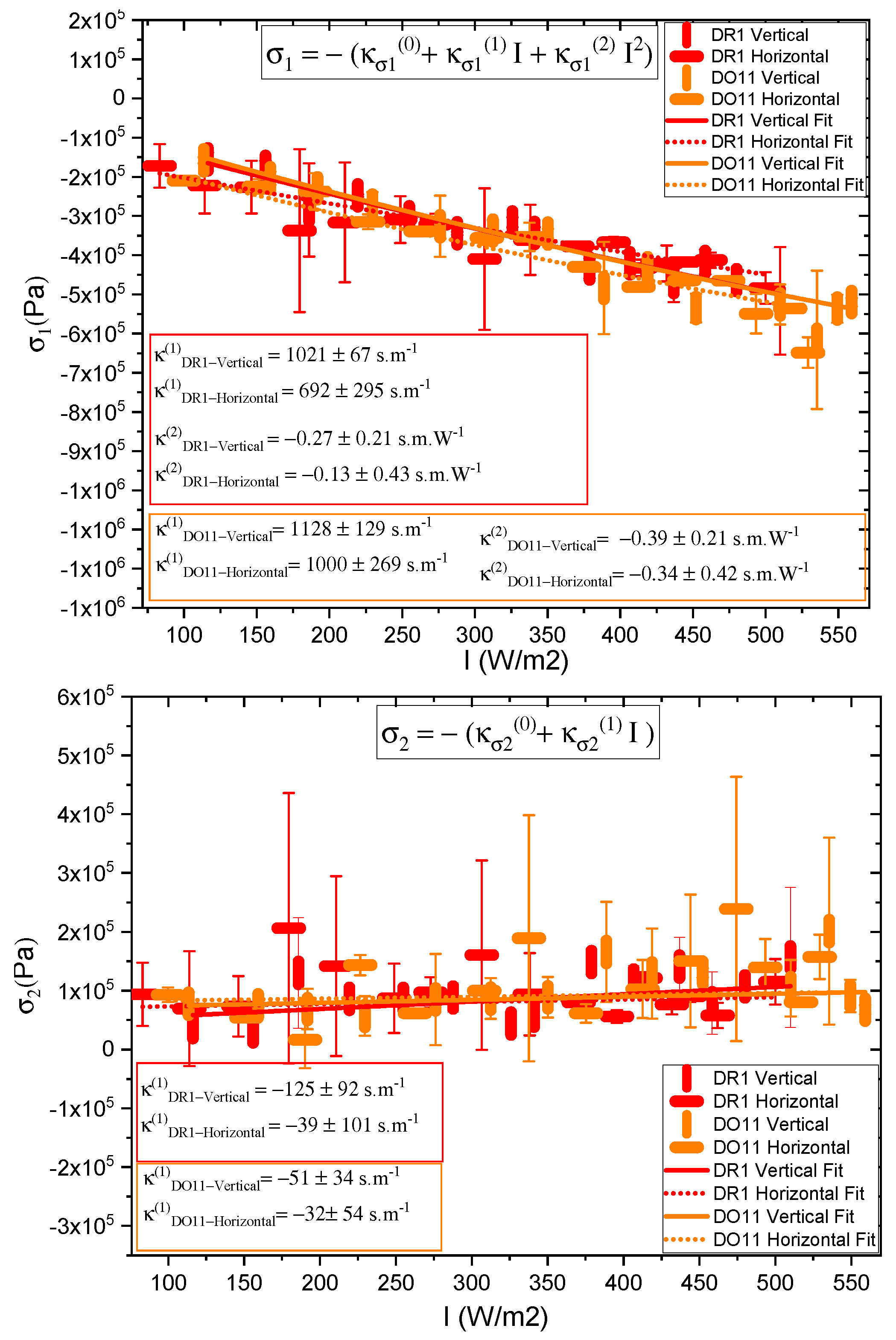

The amplitudes of the photomechanical response for the fast and slow processes determined from Equation

2 are plotted in

Figure 20. The faster response mechanism amplitude

shows a large dependence on the pump power while the slower response associated with the amplitude

remains approximately unchanged as a function of the intensity.

The fits in

Figure 20 to

and

as a function of intensity are to the power series expansions

and

Note that

and

are not the material constants but rather related to the pre-stress

when mounting the samples, which is given by

Then we can define an intensity-dependent photomechanical response as being given by

and

where

is the long-time photomechanical stress response of process

i to light of intensity

I.

The parameters

and

are determined for DR1 and DO11 doped PMMA for both vertical and horizontal pump intensities from fits to the data to Equation

37 as shown in the top portion of

Figure 20. The same is done for the long-term stress response for the process associated with time constant

by fitting the data in the bottom portion of

Figure 20 to the power series expansion given by Equation

38. In this case, the data is relatively flat, so the fit includes only the linear term.

To summarize, the data given by

Figure 20 are used to get the photomechanical coefficients

for each process, which are substituted in Equations

37 and

38 to get the long-term stress

. These fits are also used to determine the intensity-dependent photomechanical response

for each process.

The strategy for isolating the mechanisms of the photomechanical response is to compare the photothermal heating model’s predictions given by Equation

9 with the magnitude of the fast and slow response determined from the data. The heating model depends on several types of parameters. First,

,

,

and

n characterize the thermodynamic properties of the material, and are determined from the temperature dependent stress of a clamped sample as shown in

Figure 6. For DO11 and DR1, the data are fit to Equation

4 as shown in

Figure 6 to get these parameters. Next, the physical properties of each sample, such as their thicknesses

w, are directly determined with a micrometer. Properties such as the specific heat capacity of the polymer

c and the material density

are sourced from the literature. We are thus assuming that the dopant dyes do not contribute substantially to these properties because of their low concentration. This assumption may need to be revisited given the large difference in the data between DO11 and DR1 in

Figure 6. Finally, each of the time constants from the fits of the stress response are used to get

at each intensity that is used in Equation

5 to relate the temperature change to the light intensity. Recall that

and

are defined to be the short and long time constants for pump intensity

I. The strategy is to identify which exponential component of the two-exponential fit best agrees with the model’s prediction.

Alternatively, as we saw above, we can eliminate the parameter

in Equation

9 using Equation

4, yielding the semi-empirical model given by Equation

12. In this case, the measured stress

at pump intensity

I determined from the fits for the process of response time

is used in the heating model, de-emphasizing reliance on the phenomenological stress model given my Equation

4. As we will see below, the small differences between these two approaches are insignificant in determining which process is associated with photothermal heating.

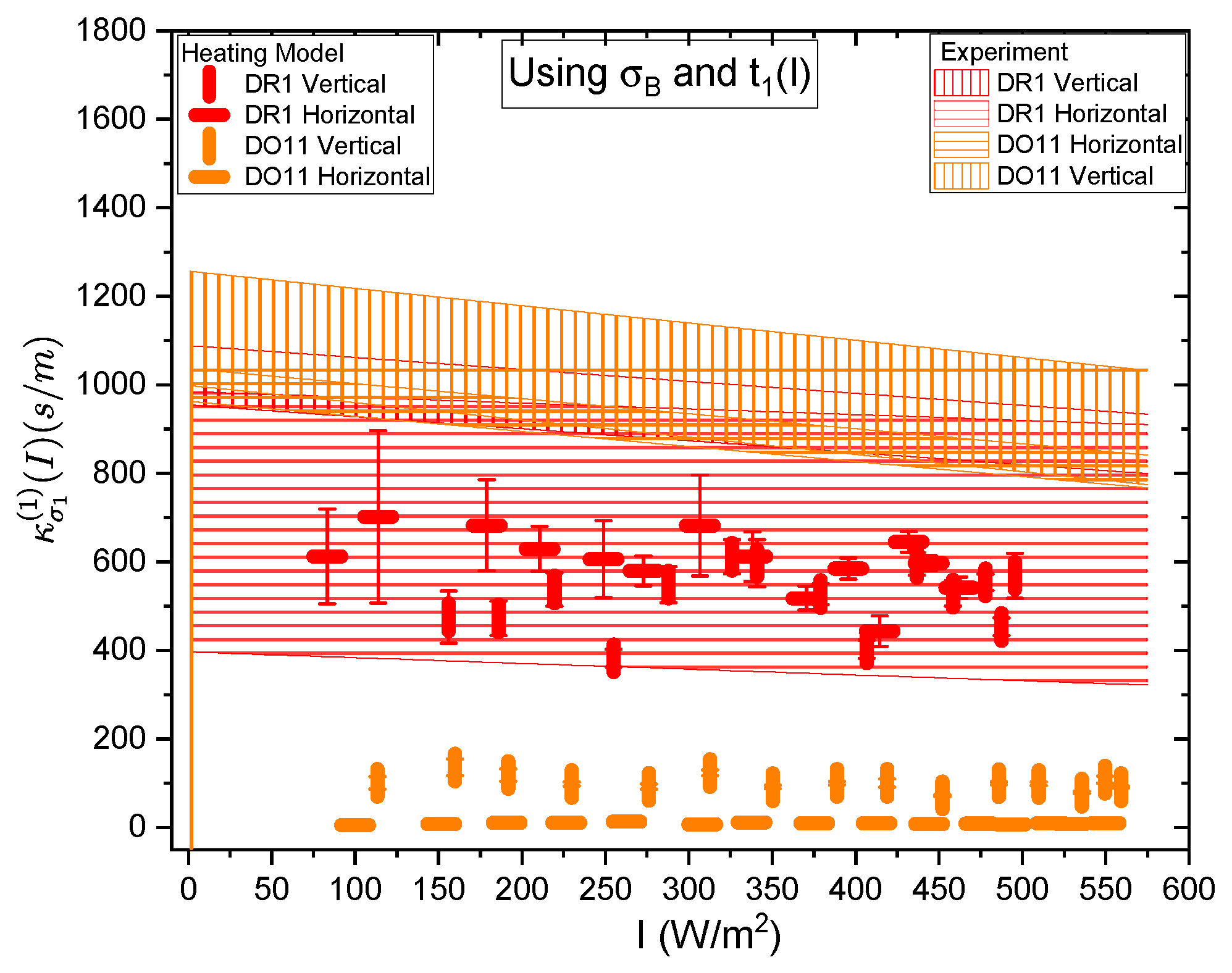

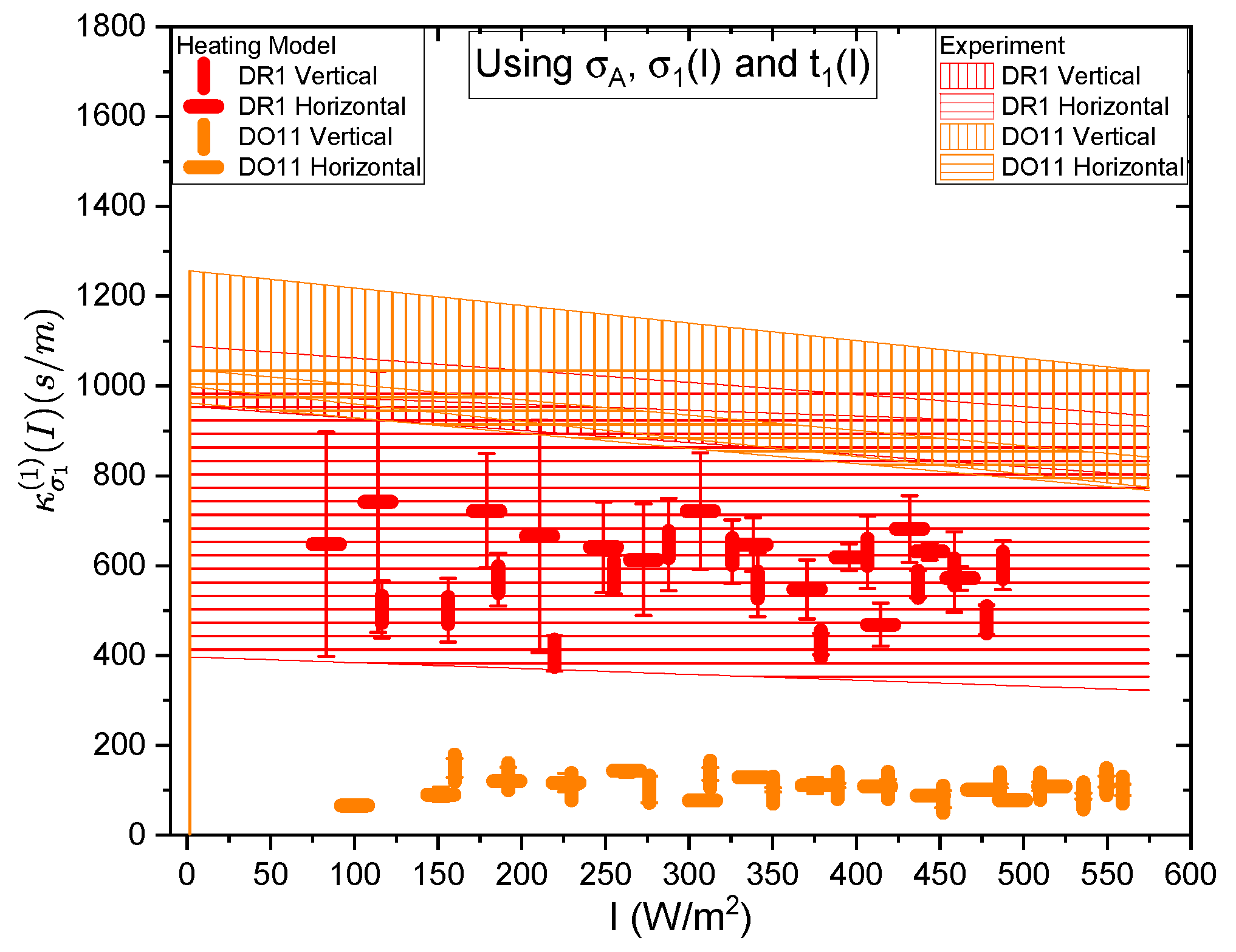

Figure 21 and

Figure 22 show a summary of the theoretical and experimental intensity-dependent photomechanical constant

for the faster process with response time

. The bands are derived from the experientially-determined amplitudes of the fast process and their widths represent the one standard deviation uncertainty band. The vertical and horizonal data markers represent the photothermal heating model’s prediction for the intensity-dependent photomechanical response for the two orthogonal pump polarization directions. Their values are determined using the heating theory given by Equation

9, plotted in

Figure 21, and Equation

12, plotted in

Figure 22. The scatter in the plots originate from the scatter in the measured time constants

that are input parameters to the theory. The semi-empirical theory using Equation

12 has an additional contribution to the uncertainty from

and

, which leads to larger error bars. Similarly, the error bands of the data are coded with vertical and horizontal hash marks to represent the polarization direction.

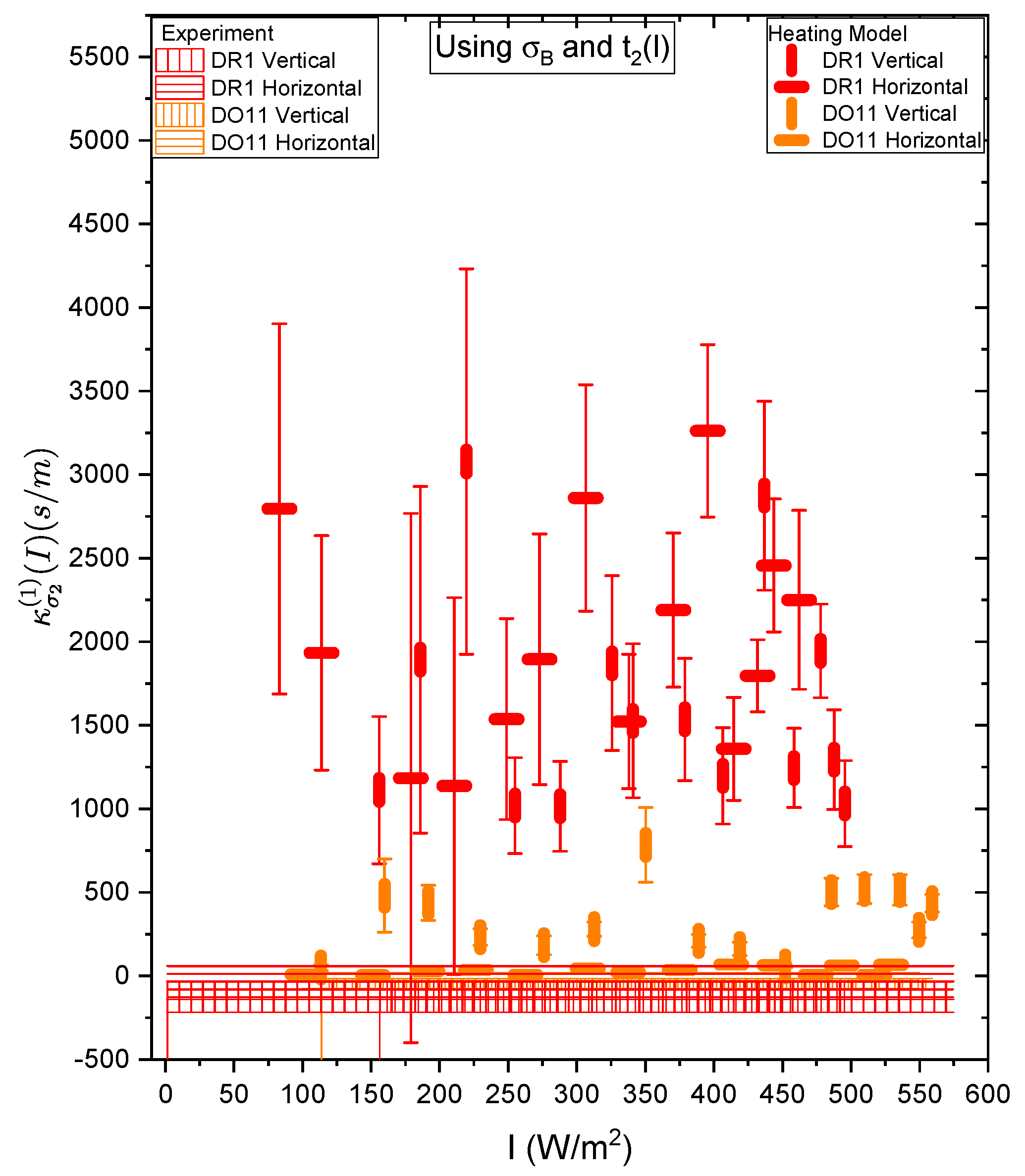

Figure 23 and

Figure 24 show the slower process with the time constant data and theory using

and

for the analysis.

Figure 21 and

Figure 22 show that the magnitude of the measured fast linear photomechanical response, as represented by the bands, decreases with pump intensity. The samples are pristine at the start of the experiment, and characterized in the same physical spot starting with low intensity, then ending at the highest intensity with uniform intensity increases in between. Measurements of the order parameter, as discussed above, show that the material undergoes long-term changes in axial order of the dopant dyes, which we provisionally attribute to long-term molecular re-orientational. This change in the fast response with exposure is consistent with the long-term process of molecular re-orientation.

Figure 21 and

Figure 22 show that the data and the photothermal heating theory for the fast response agree for DR1 but disagree in DO11. As such, we conclude that the fast process is due to heating in DR1 but not in DO11. This is puzzling unless our assumption that the heat capacities are the same for both materials is wrong. The data suggests that the heat capacity of DO11 would need to be an order of magnitude smaller than in neat PMMA to make the heating theory agree with the data, which seems unlikely.

Figure 23 and

Figure 24 show the experimental data bands and the theory markers for the slower response given by time constant

. For DO11, the photomechanical response of the data and theory seem to marginally agree with some outliers while for DR1, the data disagree with theory. However the signs disagree. This suggests that the slow response is not associated with photothermal heating in both materials.

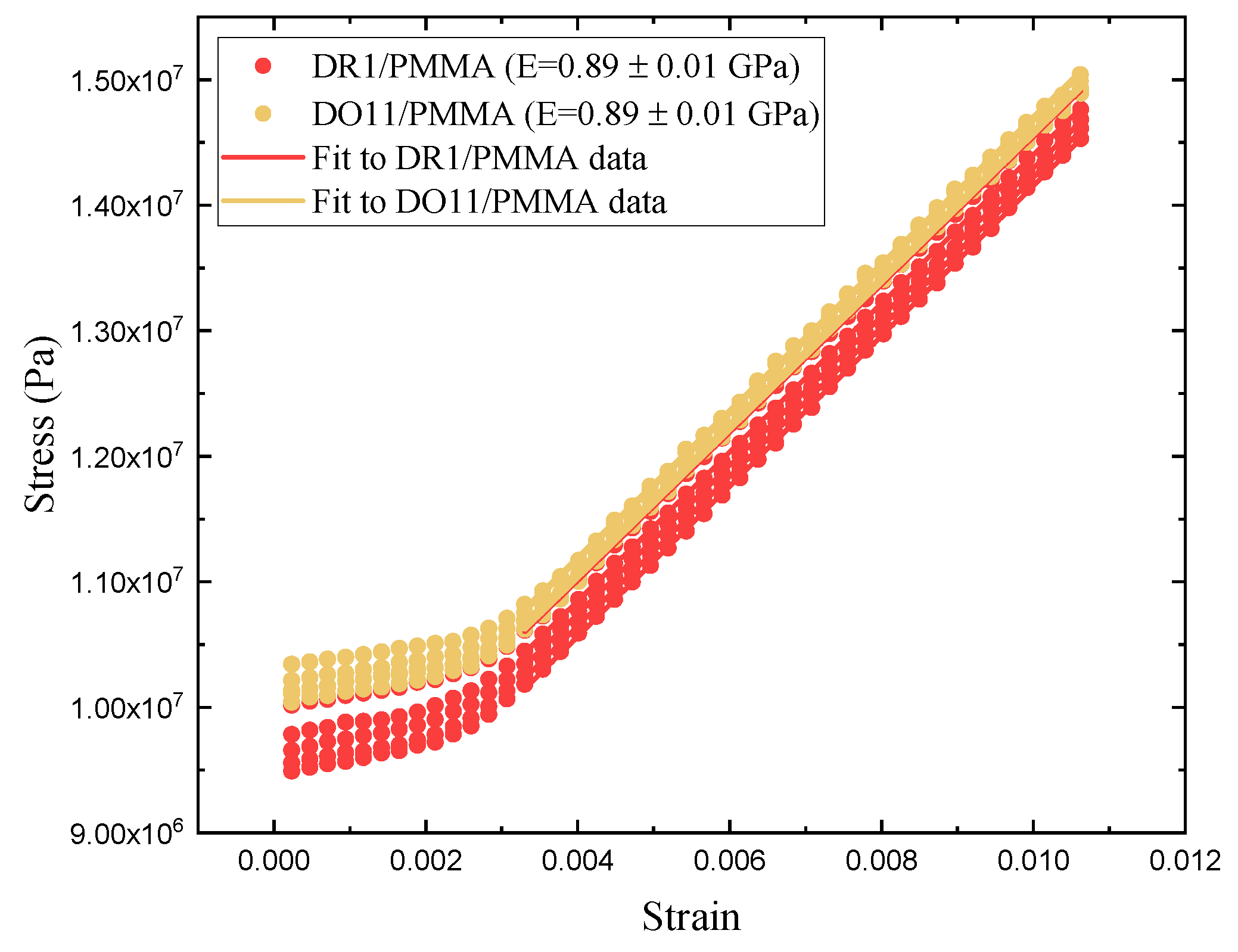

Table 4 summarizes the data. The fast response time of both DR1- and DO11-doped PMMA thin films is the same within experimental uncertainty, and is consistent with the time constant being determined form the sample geometry, which determines how heat dissipates. For heating, then, the time constants are expected to be similar, as is

. The fact that the time constants are independent of polarization is also what one would expect from an isotopic sample. This gives us greater confidence that the fast response originates in photothermal heating. The fact that DO11 has a smaller linear response from heating is also consistent with

Figure 6, which shows that heating results in a smaller temperature-dependent force. All of these data together are consistent with photothermal heating being responsible for the fast process.

The slow response in both materials is of negative sign, consistent with sample contraction as one would expect for molecular hole burning and molecular reorientation away from the pump polarization direction. Molecular re-orientation would result in a positive response for a perpendicular pump beam, while orientational hole burning would give a negative response, but of smaller magnitude. The data is consistent with hole burning but uncertainties are too large to make a definitive conclusion.

The critical intensity

due to the fast heating process is defined by

and quantifies the intensity at which the higher-order term exceeds the linear response. DO11’s critical intensity is smaller than DR1’s value because its linear response is smaller. For both materials and both polarizations, the first nonlinear correction to the photomechanical response

is the same within experimental uncertainty.