The word "arrangement," which unites the three, makes it clear that they are related to one another. Thus, we have established their relationship. The transitive property, which states that if a ̴ b and b ̴ c, then a ̴ c, is the most effective method for demonstrating the relationship between three elements. Where " ̴ " stands for "related to." Since we are aware of the link and the approach we will take to prove it, let's start the process methodically, just like we would with a mathematical issue. This process is particularly useful when attempting to demonstrate the relationship between the three mathematically. The study of the logic of shapes, quantities, and arrangements is known as mathematics. Most potentially, some emerging open problems are provided. The paper ends with some concluding remarks combined with futuristic research pathways.

I. INTRODUCTION

Poetry

“Poetry is when an emotion has found its thought, and the thought has found words.”

Robert Frost

The authors argued that poetry represents a unique way of thinking that differs from other disciplines like politics, science, and philosophy, while still sharing some common ground with them. It emphasizes that poetry can express thoughts in a distinct and clear manner, challenging traditional ideas about what constitutes thought. By doing so, poetry reveals new forms of thinking that have not yet been fully explored or articulated, making it a powerful and rebellious form of expression.

Poetry is described as a unique form of expression that captures ideas and feelings that are difficult or impossible to articulate in straightforward language. This challenges philosophers[

1], who often believe they have a complete understanding of thought, as they struggle to accept that poetry can also convey deep and meaningful insights. This suggests that poetry[

1], by expressing thoughts in unconventional ways, forces philosophy to reconsider its own definitions of thinking and what it means to understand the world.

Hence [

1], this offers an opportunity to exploreing the idea that poetry is a unique form of expression that goes beyond simply conveying personal feelings; it creates a new way of communicating that resonates with universal human experiences. In priciple [

1], poetry allows individuals to articulate their thoughts in a way that reflects both their personal perspective and a broader human condition, rather than isolating them in a private language. This means that poetry not only expresses ideas but also embodies a deeper connection to language and shared human experiences, making it a powerful tool for communication.

This suggests that poetry works by breaking down traditional meanings and creating new ways of understanding[

1], which is referred to as "meaning-otherwise." The introduction emphasizes the importance of engaging with poetry and each other during challenging times, encouraging a sense of solidarity and shared thought among writers and thinkers.

The austhorsdiscussed the positive impact of incorporating poetry into the classroom, highlighting how it can enhance student growth and empowerment. By engaging with poetry[

2], students can improve their language skills, critical thinking, empathy, and self-confidence[

2], while also discovering their own voices through creative expression. The author advocated for educators to create a poetry-rich environment that fosters collaboration and active participation, ultimately nurturing a lifelong appreciation for writing.

This emphasizes the importance of poetry in education[

2], highlighting its benefits for students' writing skills, emotional development, and critical thinking. It suggests creating a supportive classroom environment where poetry is integrated into the curriculum through workshops[

2], discussions, and creative activities. By engaging with poetry[

2], students can enhance their language proficiency, express their emotions, and develop a deeper understanding of diverse cultures and perspectives. On another strong note[

2], poetry-rich classroom enhances students' creativity, language skills, critical thinking, empathy, cultural understanding, and self-confidence. By engaging with poetry[

2], students not only expand their intellectual horizons but also develop emotional intelligence and personal growth through structured activities like writing workshops and multimedia projects. This environment empowers students as writers and fosters a lasting appreciation for literature[

2], significantly impacting their overall learning and development.

Poetry-rich classrooms foster students' creativity, language proficiency, critical thinking, empathy, cultural awareness, and self-confidence. Poetry helps students understand themselves better and expands their horizons intellectually. Poetry enhances language and critical thinking abilities while promoting empathy and emotional intelligence. Participation and personal growth are encouraged in the structured poetry writing session. Student engagement is further increased through the use of multimedia projects, competitions, anthologies, and online resources. Students are empowered as writers when they understand the value of a poetry-rich environment, which promotes personal growth and a lifetime love of reading.

Students' learning and general growth can be greatly impacted by including them in poetic exercises and providing an organised workshop.

The authorhighlightd the importance of being attentive to the emotional needs of others, particularly in a workplace setting. This indeed suggests that a simple act of pausing to engage with a colleague who seems distressed could have significant consequences, potentially even saving their life. The reference to a poem [

3]emphasizes how literature can inspire us to recognize and respond to the struggles of those around us, reinforcing the idea that human connection is vital in times of crisis.

presented four key ideas about the relationship between poetry and abstract thought. First, he argued that abstract thinking is essential to poetry and cannot be separated from it. Second, he explained that abstract thought exists in different levels, from simple general ideas to deep philosophical reflections. Lastly, they note that when poetry includes philosophical ideas, it serves a different purpose than traditional philosophical writing, and they highlight the importance of understanding these differences when engaging with poetry that has a philosophical angle.

Poetry is not just a collection of written words but an active process that we experience in a physical and emotional way. It suggests that poetry[

5], like metaphors, helps us understand and navigate our experiences by connecting different ideas and feelings. The author [

5]also posited that this form of poetic thinking may have existed even before modern human cognition, playing a role in shaping how we think and feel about the world.

Emotions play a crucial role in how we understand ourselves and interact with the world around us [

5], which explains that having a rich vocabulary for emotions enhances our emotional intelligence, which helps us recognize and manage our own feelings and those of others. Poetry serves as a powerful tool for developing this emotional intelligence by allowing us to explore and reflect on emotions in a shared context, ultimately shaping our social values and ethical understanding.

“God used beautiful mathematics in creating the world”

Paul Dirac

Ethnomathematicsis a field of study that explores the connection between mathematics and different cultural backgrounds, examining how mathematical concepts are developed and used within various societies. The term combines "ethno," relating to cultures[

6], and "mathematics," indicating that it looks at how mathematical practices vary across cultures, rather than assuming a single universal approach. This highlights that everyday mathematics[

6], which people use in their daily lives, can differ significantly from the formal mathematics taught in schools, suggesting a need for a broader understanding of mathematical practices in diverse cultural contexts.

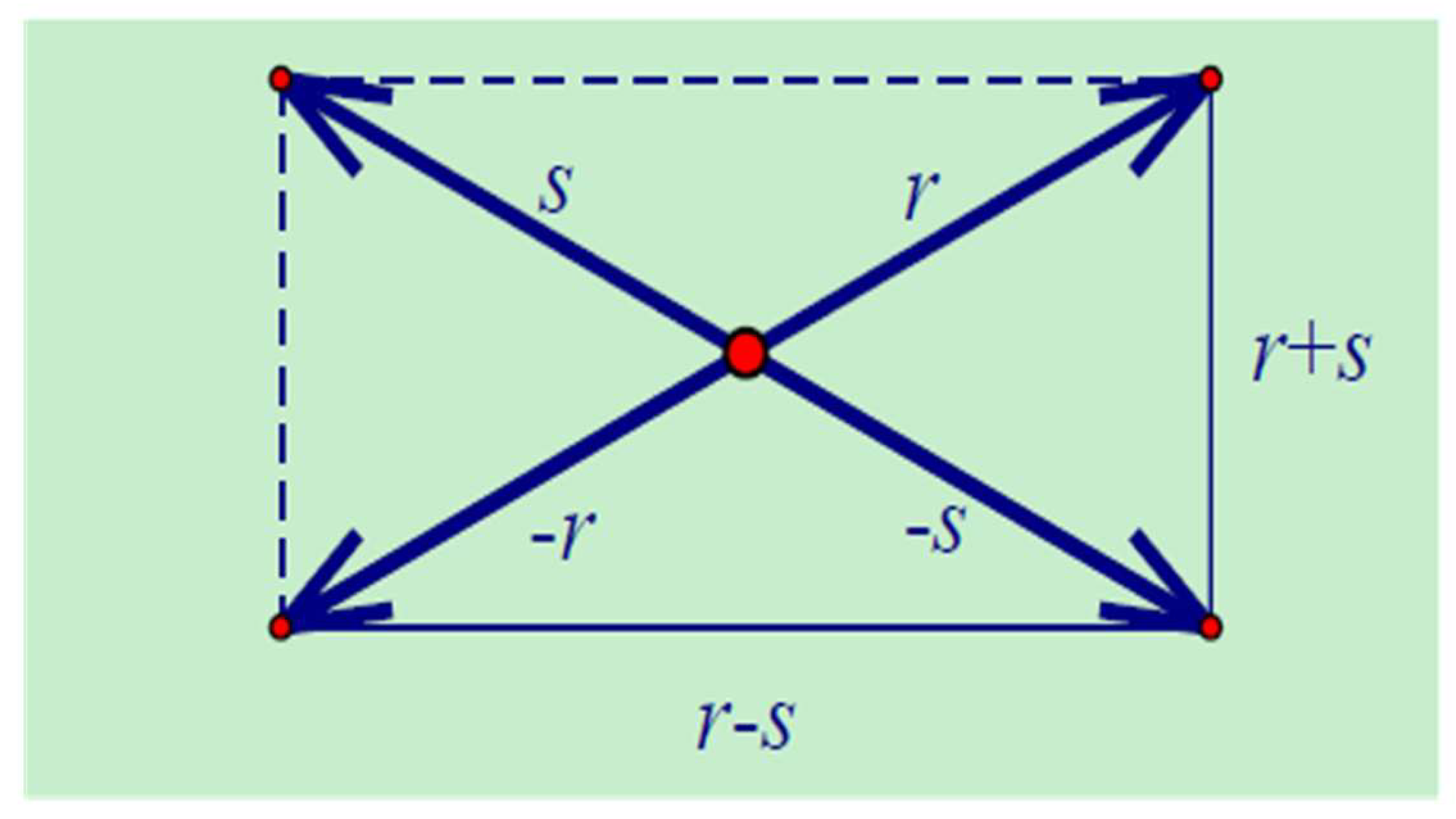

Most African communities south of the Sahara have a tradition of building houses with circular or rectangular shapes[

6]. In Mozambique[

6], for example, there are two common methods for constructing rectangular bases that do not involve the conventional approach of creating right angles one at a time. This clearly showcases the diverse mathematical practices across cultures[

6], showing that different methods can achieve the same geometric outcomes in unique ways.

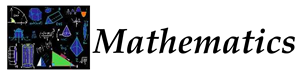

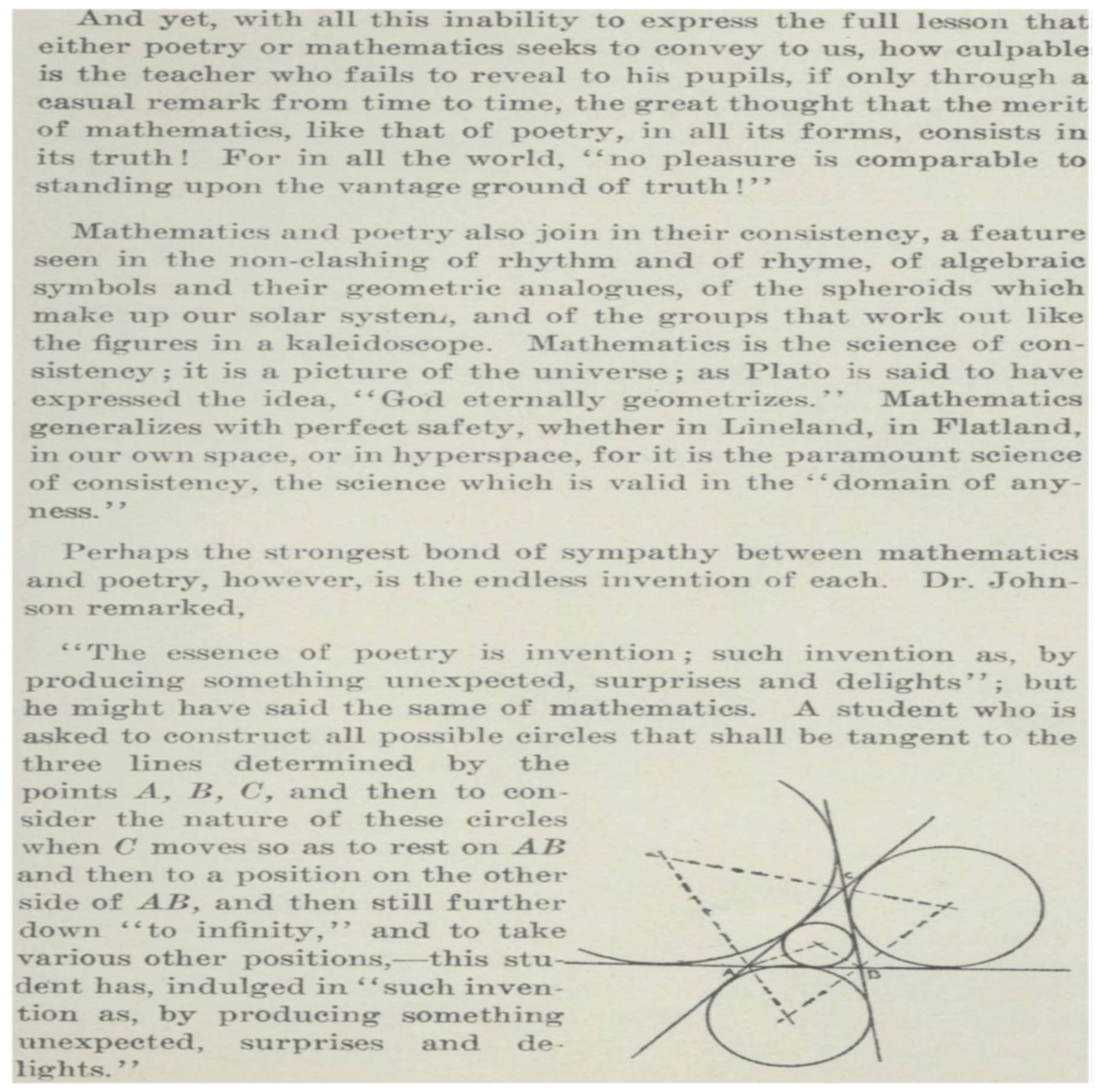

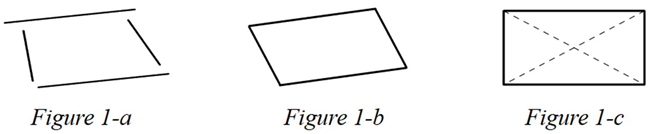

Method 1: The builders begin by placing two long, equal-length bamboo poles on the ground. These initial sticks are then joined by two additional sticks that are identical in length but typically shorter than the original ones (1-a). The sticks are now rearranged to create a quadrilateral (1-b) closure. The picture is further manipulated until the diagonals (1-c), as measured by a rope, are equal. After that, lines are drawn from where the sticks are now on the ground, allowing the house builders to begin construction.

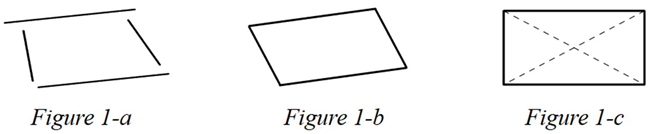

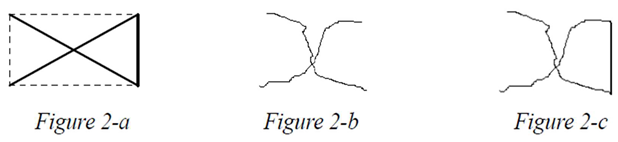

Method 2: Two ropes of equal length are knotted together at their midpoints by the home builders (2-a). A bamboo stick is placed on the floor with pins driven into the ground at either end. The stick's length is equal to the intended width of the house. Every rope has a termination that is connected to one of the pins (2-b). After that, the ropes are stretched, and fresh pins are driven into the earth at the ropes' remaining two ends. The four vertices of the home that has to be constructed are determined by these four pins (2-c).

The aforementioned resources provide some insight into China's high school mathematics curriculum change[

6]. As one of the key and fundamental ideas of contemporary mathematics, vector is a significant component of "Compulsory Mathematics Textbook 4," which was created based on "Senior High School Mathematics Curriculum Standards." It has a strong practical history and is a helpful tool for teaching algebra, geometry, and trigonometry. The two techniques used to build the rectangular basis of traditional homes involve knowledge that is closely related to vector, as showcased by

Figure 3 and

Figure 4(c.f., [

6]).

Incorporating culturally diverse materials into the curriculum, accurately assessing students from diverse backgrounds[

6], building everyone's self-esteem, and teaching them to respect all ethnic groups and cultures will all help students adjust to a multicultural environment in the future[

6]. It makes sense to incorporate ethnomathematics and mathematics into the curriculum, and doing so will help people recognise and understand the intrinsic mathematical significance of unique cultures and societies.

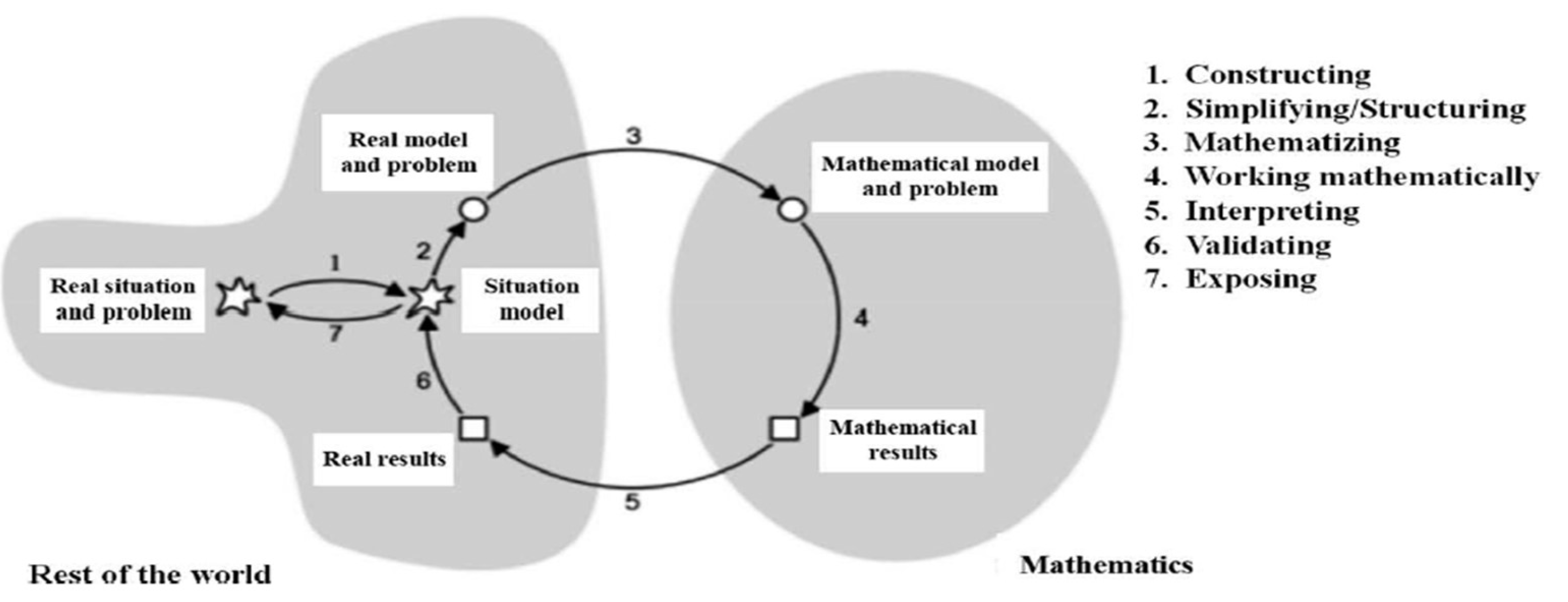

The theoretical background of realistic modeling, primarily influenced by focuses on using mathematics to solve real-world problems instead of just learning mathematical concepts [

7]. This approach encourages students to engage in authentic tasks that reflect real-life challenges[

7], helping them develop practical problem-solving skills. While there are various modeling cycles proposed by researchers, such as the one by Blum, there isn't a universally accepted cycle, allowing for flexibility in how mathematical modeling is taught and applied, as illustrated by

Figure 5 (c.f., [

7]).

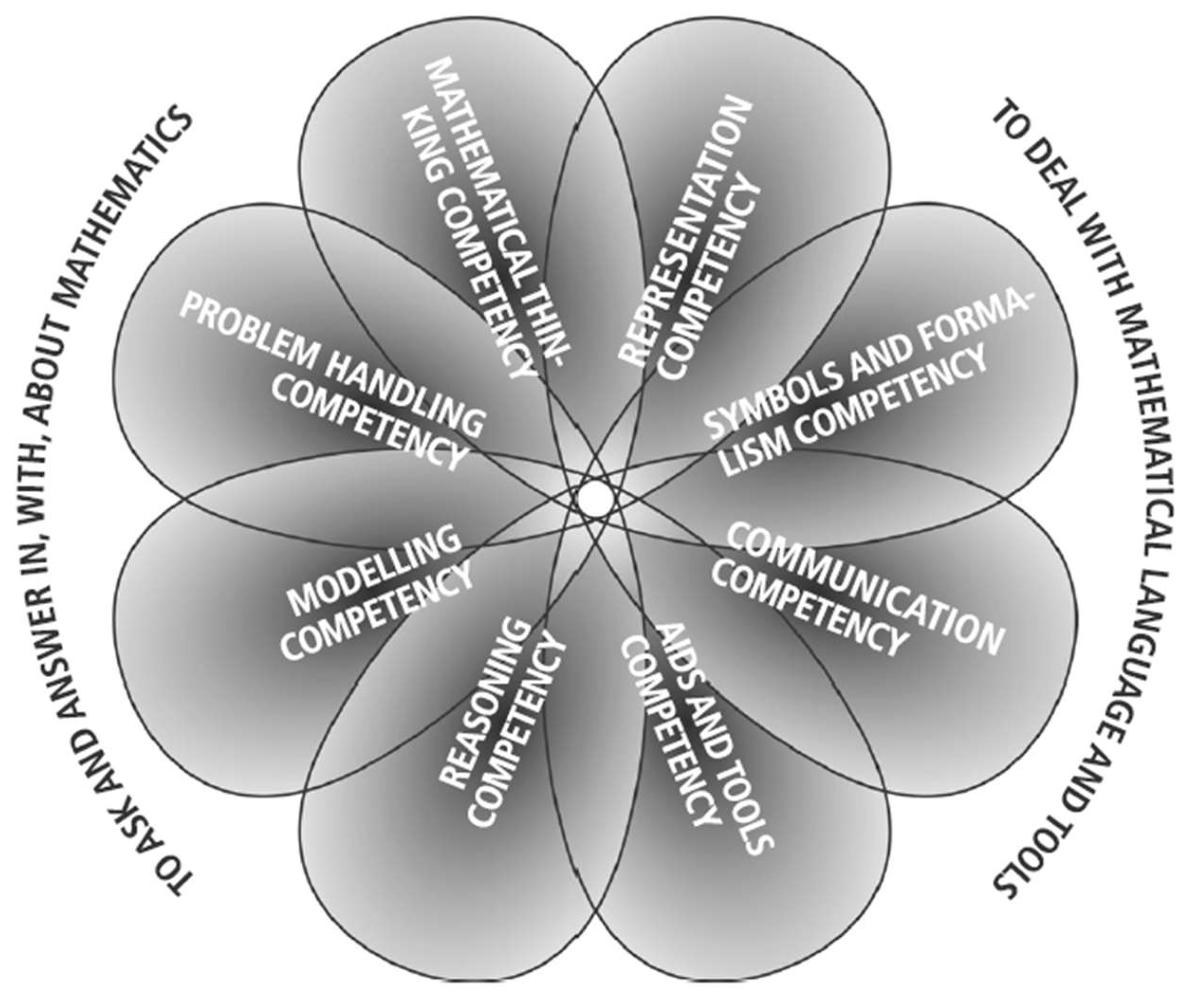

The receptive facet of a mathematical competency refers to a person's ability to understand and engage with ideas or processes that have already been presented by others[

8], such as evaluating a mathematical proof or a proposed solution. In contrast[

8], the constructive facet emphasizes the individual's skill in independently applying their mathematical knowledge to create new solutions or proofs in various situations. Together[

8], these facets highlight the different ways a person can utilize their mathematical competencies, either by responding to existing information or by generating new insights, as portayed by

Figure 6(c.f., [

8]).

Music

“Listening is the key to everything great in music.”

(Pat Metheny)

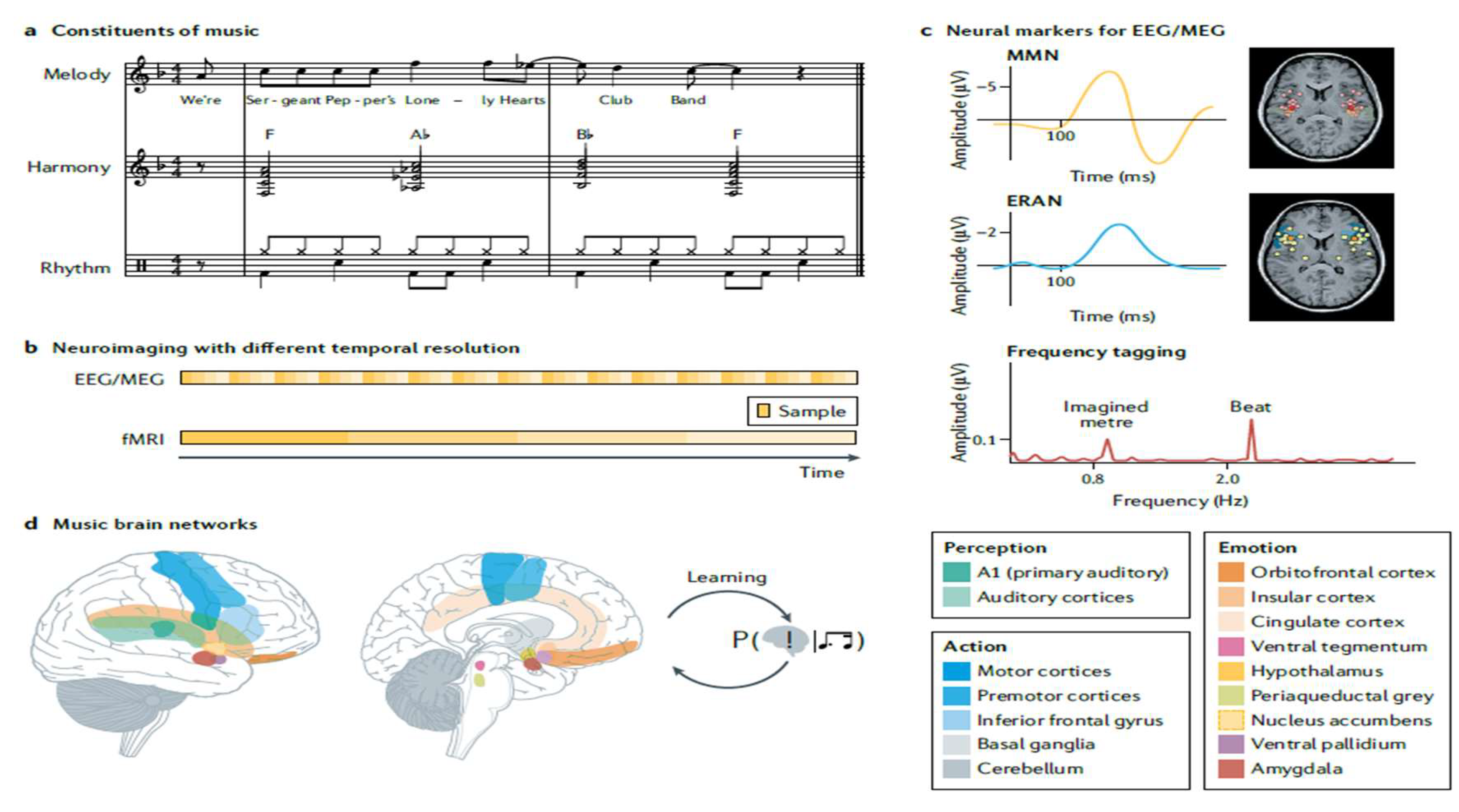

Music is a universal part of human culture that not only provides enjoyment but also influences our emotions and physical movements. Learning to play music affects how our brains are structured and function, as it involves predicting what will happen next in a piece of music. Understanding music perception involves not just hearing but also action, emotion, and learning, highlighting the brain's ability to predict and how this relates to creativity, especially in activities like music improvisation, were thoroughly discussed in [

9].

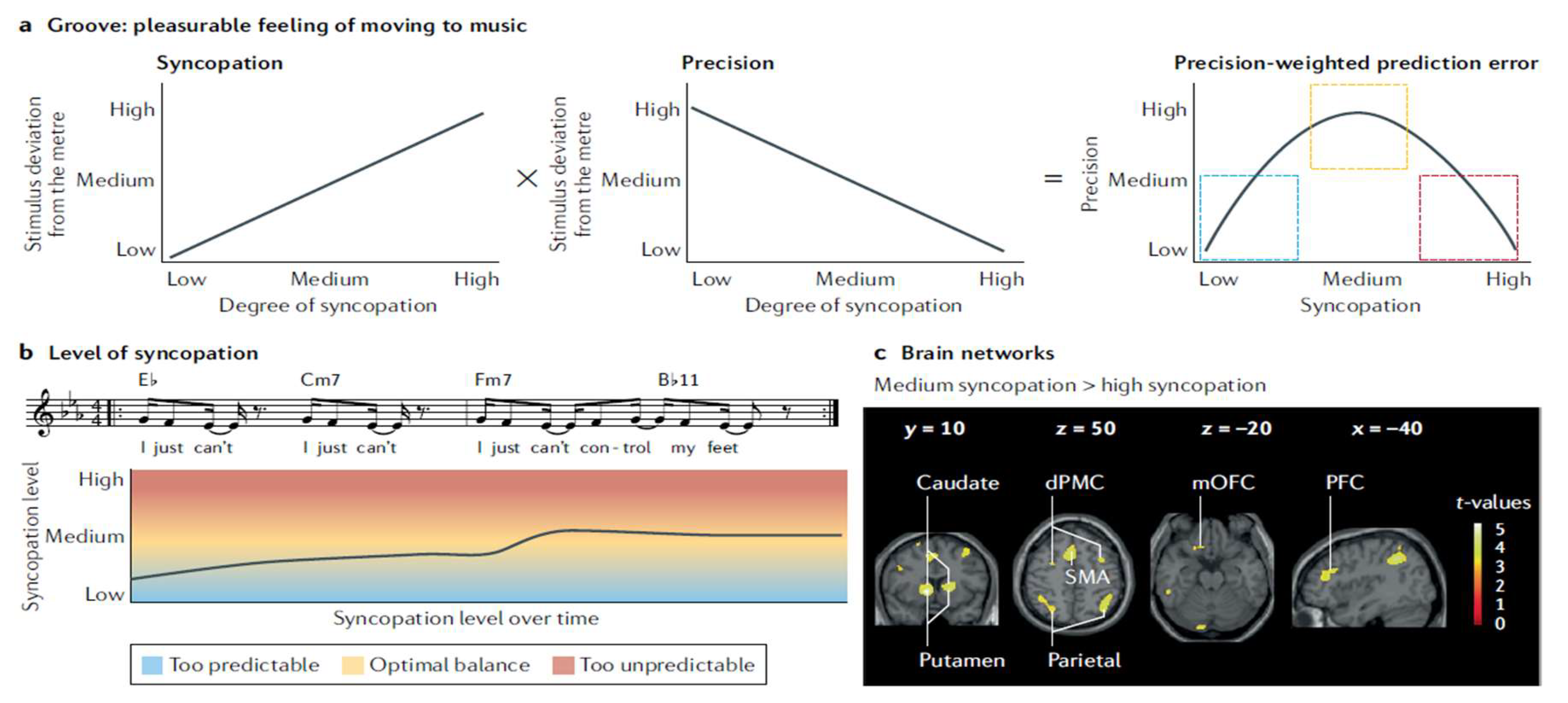

This showcases how music[

9], while sometimes viewed simply as organized sounds, holds significant emotional meaning for many people. From a theoretical perspective, music can be analyzed into three basic components: melody (the main tune), harmony (the combination of different musical notes played together), and rhythm (the pattern of beats and timing). These elements work together to create the emotional and meaningful experiences that listeners often associate with music, as depicted by

Figure 7(c.f., [

9]).

In music[

9], the way it is organized often includes patterns that help listeners anticipate what will happen next. This anticipation is based on statistical learning[

9], where people pick up on common musical structures and trends over time. When these expectations are met, it creates a sense of satisfaction[

9], but if they are not met, it can lead to surprise or even confusion, highlighting the dynamic relationship between music and listener engagement.

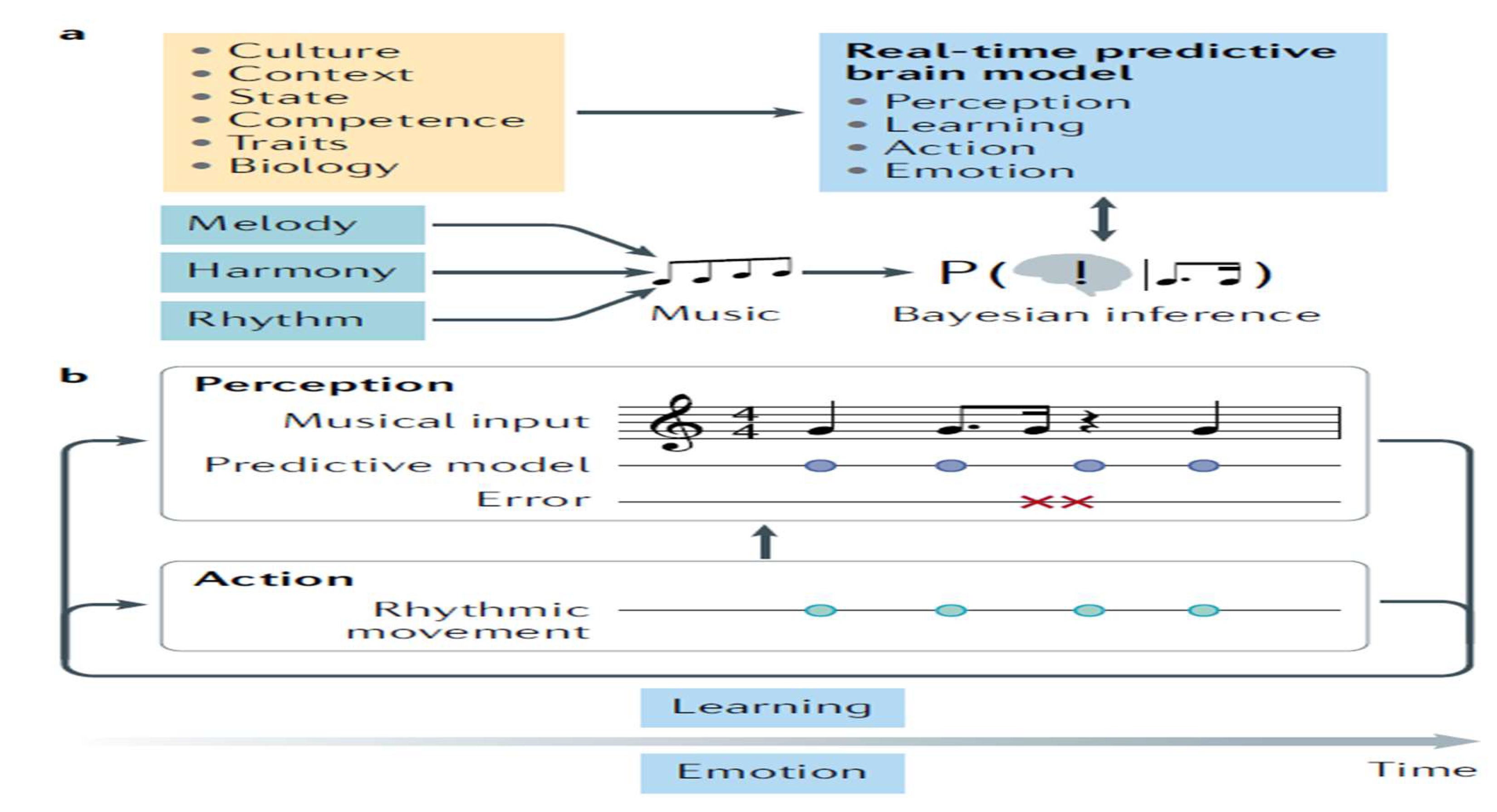

The experience of music is closely connected to how our brains create predictions about what we will hear next. For example[

9], when we listen to music, we recognize patterns like tonality, which helps us understand the main notes and chords, and metre, which helps us feel the rhythm. This ongoing process of making predictions not only shapes our perception and emotional responses to music but also contributes to our learning over time, as explained by the predictive coding of music (PCM) model.

The PCM suggests that when we listen to music, our brains use past experiences to predict what we will hear next[

9], which helps us understand the music better. For example, when we hear a syncopated rhythm, where a beat is unexpectedly delayed[

9], our brains recognize this as an error in our predictions, which might make us want to tap our feet to keep the beat. This active engagement with music not only shapes our emotional responses but also enhances our musical learning by continuously updating our predictive models over time, as illustrated by

Figure 8(c.f., [

9]).

Melody refers to the sequence of musical notes that create a recognizable tune, which is crucial for distinguishing one piece of music from another [

10],[

11],[

12],[

13],[

14],[

15], like the famous opening of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony. When a piano key is pressed [

10],[

11],[

12],[

13],[

14],[

15], it produces a note defined by its fundamental frequency (pitch) and additional overtones that give it a unique sound quality, known as timbre. Research shows that our brains can identify a single pitch even when the main frequency is missing [

10],[

11],[

12],[

13],[

14],[

15], and this pitch perception involves different processes for pitch height (how high or low a note sounds) and pitch chroma (the quality that allows us to categorize notes, like different C notes in various octaves).

In music, the structures that help us predict harmony and melody[

9], often called "syntax," are important for understanding how we experience emotions and learn about music across different cultures. The PCM model suggests that our brains create expectations about music based on previous experiences with harmony[

9], even if a melody doesn't have clear harmonies. For example, when listening to a song like "Blame It on the Boogie," the rhythm makes us want to move, showing how rhythm and melody work together to engage us, as visualized by

Figure 9 (c.f., [

9])).

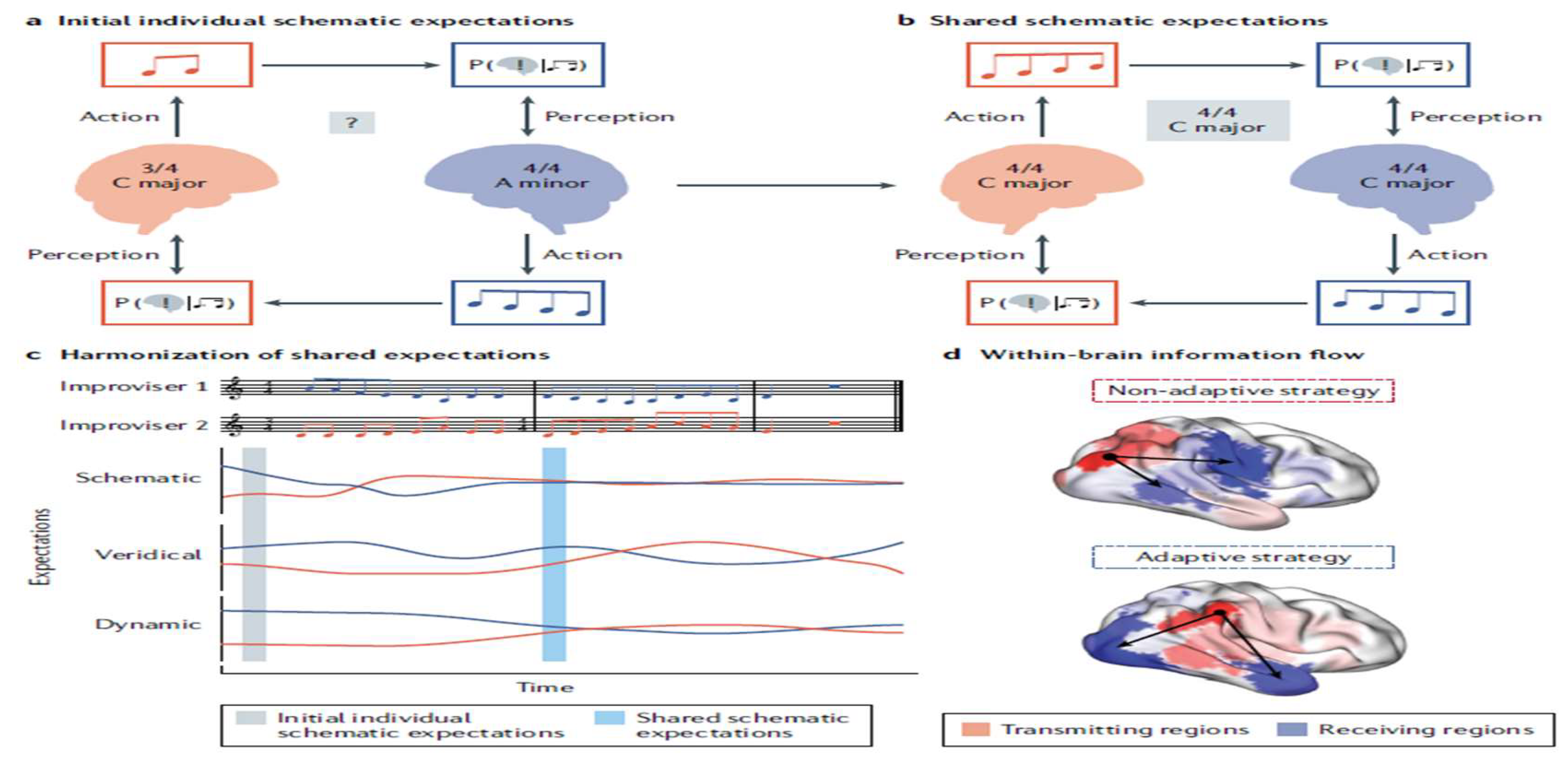

Musical interaction involves two musicians improvising together, who may start with different rhythmic patterns (like 3/4 and 4/4 time) and musical keys (like C major and A minor). Over time[

9], they can harmonize their expectations through a process called predictive coding, which helps them align their musical understanding. The study also shows how their brain activity differs when they adapt to each other, with some musicians being more flexible in synchronizing their rhythms than others, as portrayed by

Figure 10 (c.f., [

9]).

Over the past two decades[

9], research has significantly advanced our understanding of how the brain processes music, primarily through a concept called predictive coding, which helps explain how we anticipate musical patterns. Future studies are needed to explore how music influences social interactions and shared experiences[

9], including the potential for music to evoke feelings of well-being or "eudaimonia." Additionally[

9], there are many unanswered questions about how different musical elements interact and how we can generate musical experiences in our minds without actual sound, which could lead to new insights into the brain's functioning and the meaning of music in our lives.

Goleman's theory of emotional intelligence emphasizes the importance of social skills and self-awareness[

16], which can be beneficial in music education settings. While some aspects of his theory may conflict with traditional views in arts education[

16], it suggests that understanding emotions can enhance social interactions among students, especially in group music activities. Further research is needed to explore how applying Goleman's ideas might improve collaboration and performance quality in music ensembles.

Music educators should be cautious about quickly adopting all of Daniel Goleman's ideas[

16], particularly in how they relate to emotional intelligence in learning environments. While there is a risk of oversimplifying his theories into labels, exploring his concepts in contexts where peer interactions are important could lead to valuable educational practices. Ultimately[

16], this approach may help students better understand their emotions while engaging with music, which is a key objective in music education.

The current paper contributes to:

Putting in both theory an practice how poetry and music are employed to teach mathematics

The provision of open problems to enrich our way of thinking on how to think beyond classical frameworks of teaching mathematics

The paper is portrayed by the following schematic:

II. CRAFTING INNOVATIVE-LED MATHS TEACHING THROUGH POETRY AND MUSIC

A poetic-based approach to teach mathematics

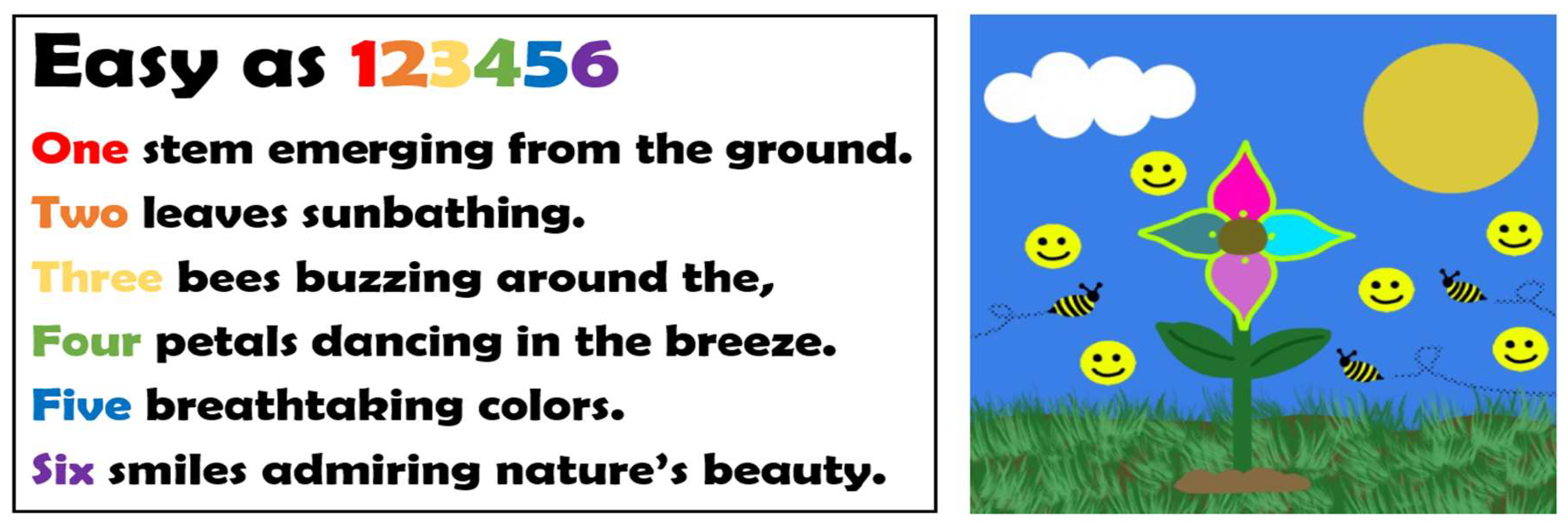

In the summer of 2021, the author explored an innovative approach to engage children in mathematics through "math poetry," aiming to make math enjoyable and less intimidating. Recognizing that the word "math" can create anxiety for many students, the author designed activities that blended poetry with mathematical concepts, allowing students from grades K-12 and college to learn creatively without realizing they were practicing math. The paper includes examples of poems created by students in grades two through eight, showcasing the effectiveness of this method in fostering a positive attitude towards math.

To enhance creativity and enjoyment in poetry writing for students, the author provided graph paper and coloured pencils, which allowed for a visual and artistic approach to the activity. The use of seven different types of poems was tailored for students as young as second grade[

17], and students were encouraged to list their interests beforehand to alleviate the common challenge of choosing a topic. This strategy not only made the writing process more engaging but also highlighted the importance of personal connection in creative expression[

17]; for more advanced poetry, the use of computers was suggested as a beneficial tool.

Kindergarteners are at a stage where they are learning foundational reading and writing skills[

17], which means they may not yet be fully proficient in these areas. The author's primary objective in working with this age group is to introduce them to graph theory[

17], a branch of mathematics that studies the relationships between objects, in a gentle and engaging way. By using map colouring as an activity, the author aims to make the concepts of graph theory accessible and fun[

17], helping young children to grasp mathematical ideas through a creative and visual approach.

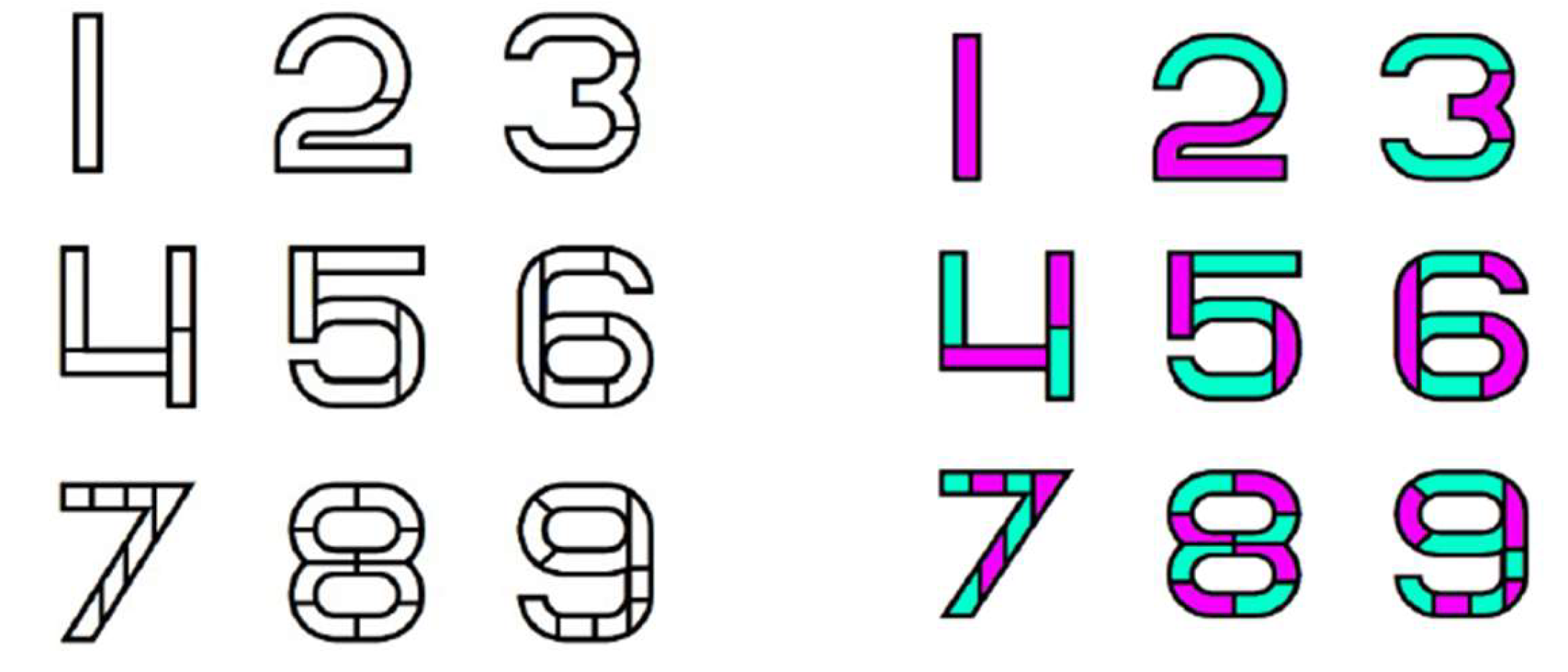

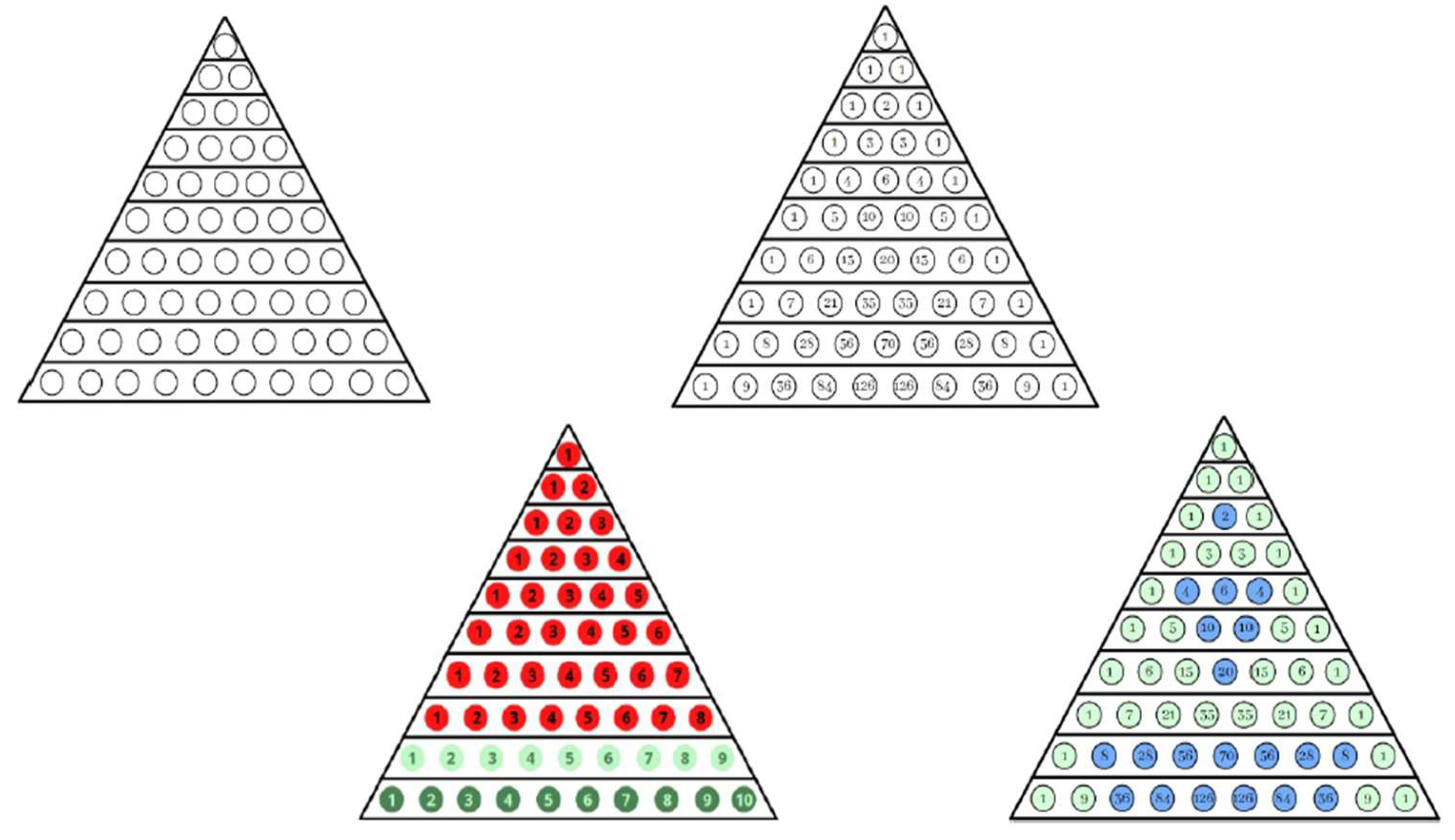

In

Figure 11(c.f., [

17]), the activity involves dividing numbers into sections based on their values, which helps teach young students about quantity and numerical relationships. This method also incorporates map colouring concepts, where students learn that adjacent sections cannot share the same colour, reinforcing the idea of distinct categories and promoting critical thinking. By combining these mathematical principles with engaging activities, educators can create a more interactive and enjoyable learning experience for kindergarteners.

The phrase "Coloring, counting, graphs! An activity for kindergarteners" refers to a creative educational activity designed to introduce young children to basic concepts of graph theory through engaging methods like colouring. In this activity, kindergarteners use colours to represent different areas or nodes on a map, which helps them understand how to visualize relationships and connections in a simple and playful manner. This approach not only makes learning fun but also lays the groundwork for mathematical thinking by integrating art and creativity into early education.

Figure 12 (c.f., [

17]) describes an educational activity that uses counting to help students understand patterns in Pascal's Triangle, a mathematical structure that illustrates the coefficients of binomial expansions. By numbering circles in a triangle and using colours to differentiate between numbers, such as colouring all "1"s blue or separating odd and even numbers, students can visually grasp the concept of patterns in mathematics. Additionally[

17], the activity encourages exploration of the Sierpinski Triangle within Pascal's Triangle by identifying multiples, thereby enhancing students' mathematical reasoning and pattern recognition skills.

For students in grades 1-2, teachers can use wordplay as a creative way to introduce basic arithmetic concepts like addition and subtraction[

17]. By manipulating words in a playful manner[

17], students engage in mathematical thinking while also practicing deductive reasoning and making connections between words. This approach not only makes learning math enjoyable but also helps students of various ages develop a more intuitive understanding of mathematical principles[

17]. This can be illustrated by

Figure 13 (c.f., [

17]).

To introduce word problems in math, the author uses a creative approach involving sestains, which are six-line poems where each line includes its corresponding line number[

17]. This activity encourages students to visualize the problems by drawing a picture of their story, making math feel less intimidating and more relatable. Additionally[

17], for older students in grades three to five, haikus—structured poems with a five-seven-five syllable pattern—are employed to teach concepts like prime numbers, helping students engage with mathematical ideas through a familiar and enjoyable format, as in

Figure 14(c.f., [

17]).

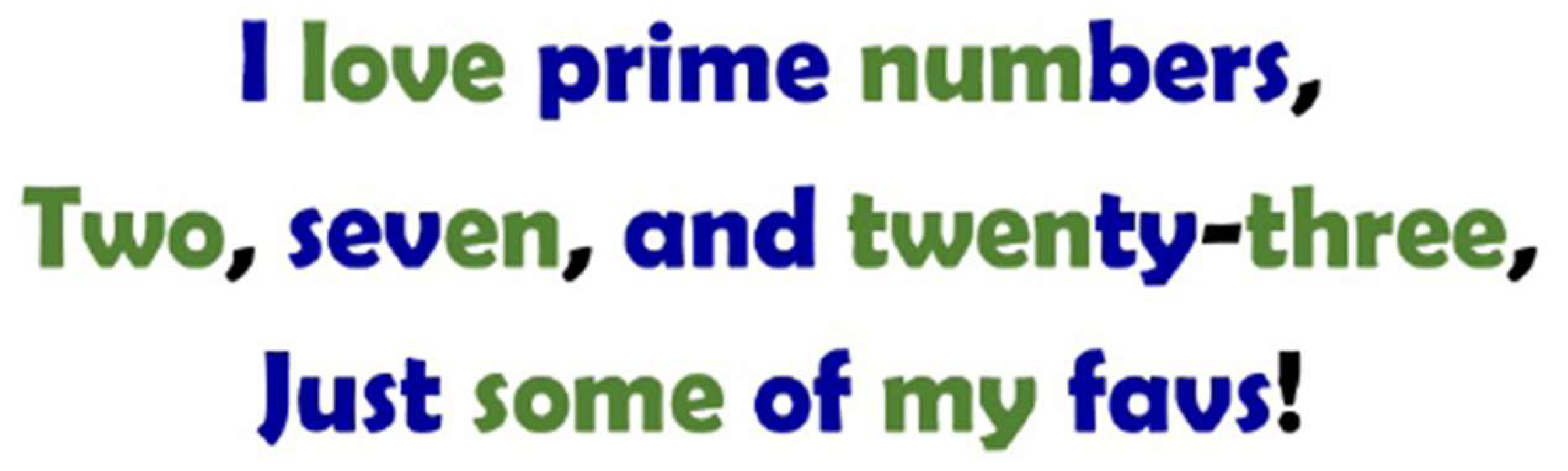

Haikus are a specific type of poem that consists of three lines with a syllable structure of five syllables in the first line, seven in the second, and five in the third, totaling 17 syllables. In the context of teaching[

17], using haikus can effectively introduce the concept of prime numbers to students, as the constraints of the poem encourage them to think critically about the structure and properties of numbers. This approach not only makes learning about prime numbers engaging but also helps students practice their understanding of syllables and poetic forms, as shown by

Figure 15 (c.f., [

17]). The structure of a haiku [

18], which is a traditional form of Japanese poetry consisting of three lines with a specific syllable count: five syllables in the first line[

18], seven in the second, and five in the third, totaling 17 syllables.

This structured format makes haikus accessible for students, as it provides clear guidelines for crafting their poems. Additionally[

18], the familiarity of haikus as a poetic form can help engage students in learning about concepts like prime numbers through creative expression.

This highlights a potential challenge for younger students[

17,

18], specifically those in grades 1-2, when it comes to writing haikus, which require an understanding of syllable structure. Since [

17,

18] these students may lack sufficient experience with syllables, they might struggle to create poems that adhere to the five-seven-five syllable format typical of haikus. To address this, the author suggests using clapping as a technique to help students learn and recognize syllables[

17,

18], thereby facilitating their ability to compose poetry.

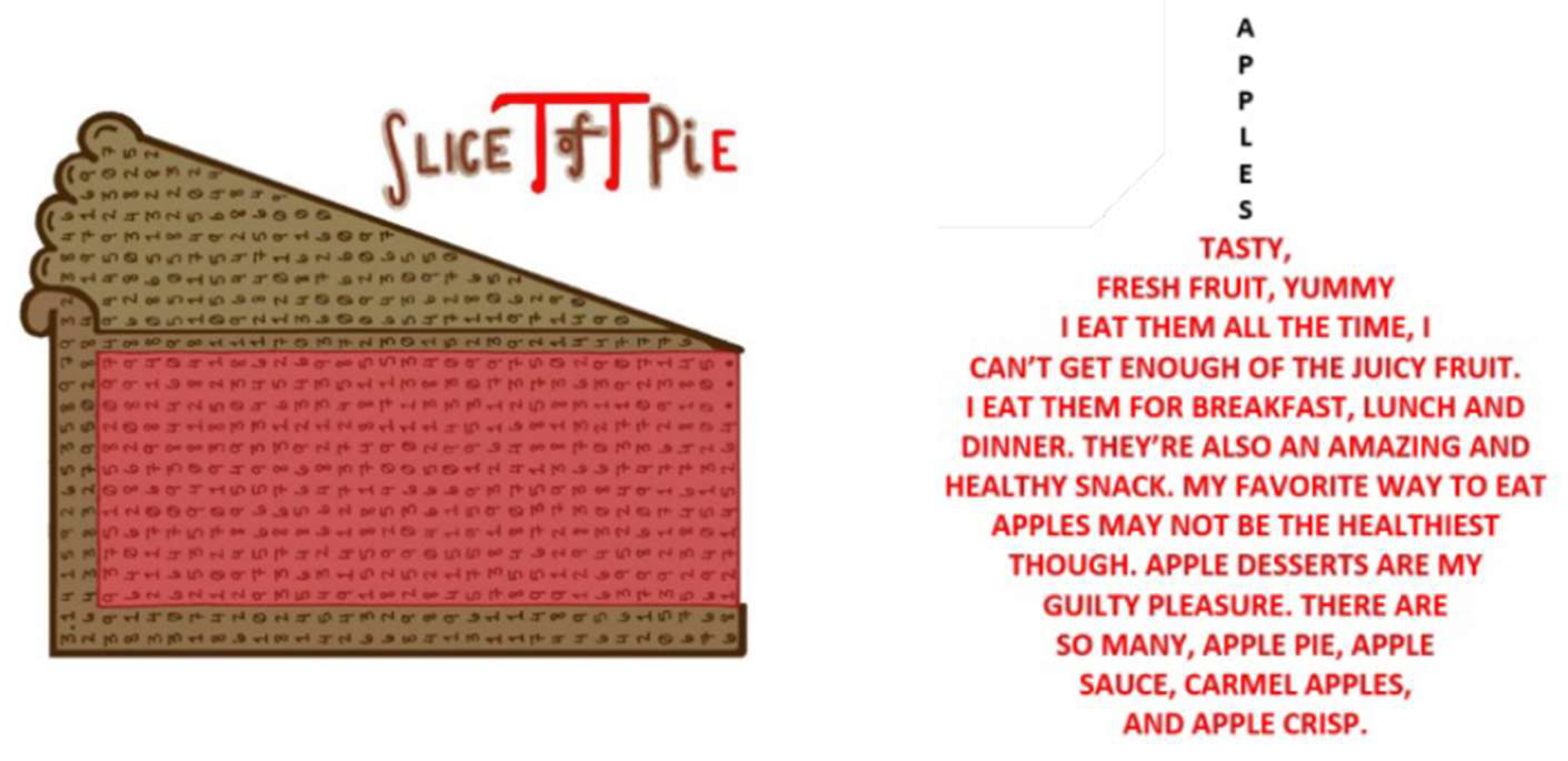

The author explored using lipograms—texts that intentionally omit certain letters—as a creative way to teach mathematical concepts related to sets. By removing specific letters from the alphabet, such as in the example where only the vowels "a" and "e" are used, students can explore ideas like set elements, unions, and intersections, which can also be visually represented using Venn diagrams. Additionally[

17], this highlights the introduction of symmetry in geometry for high school students, encouraging them to create poems that incorporate symmetric letters and shapes, thereby reinforcing their understanding of geometric principles.

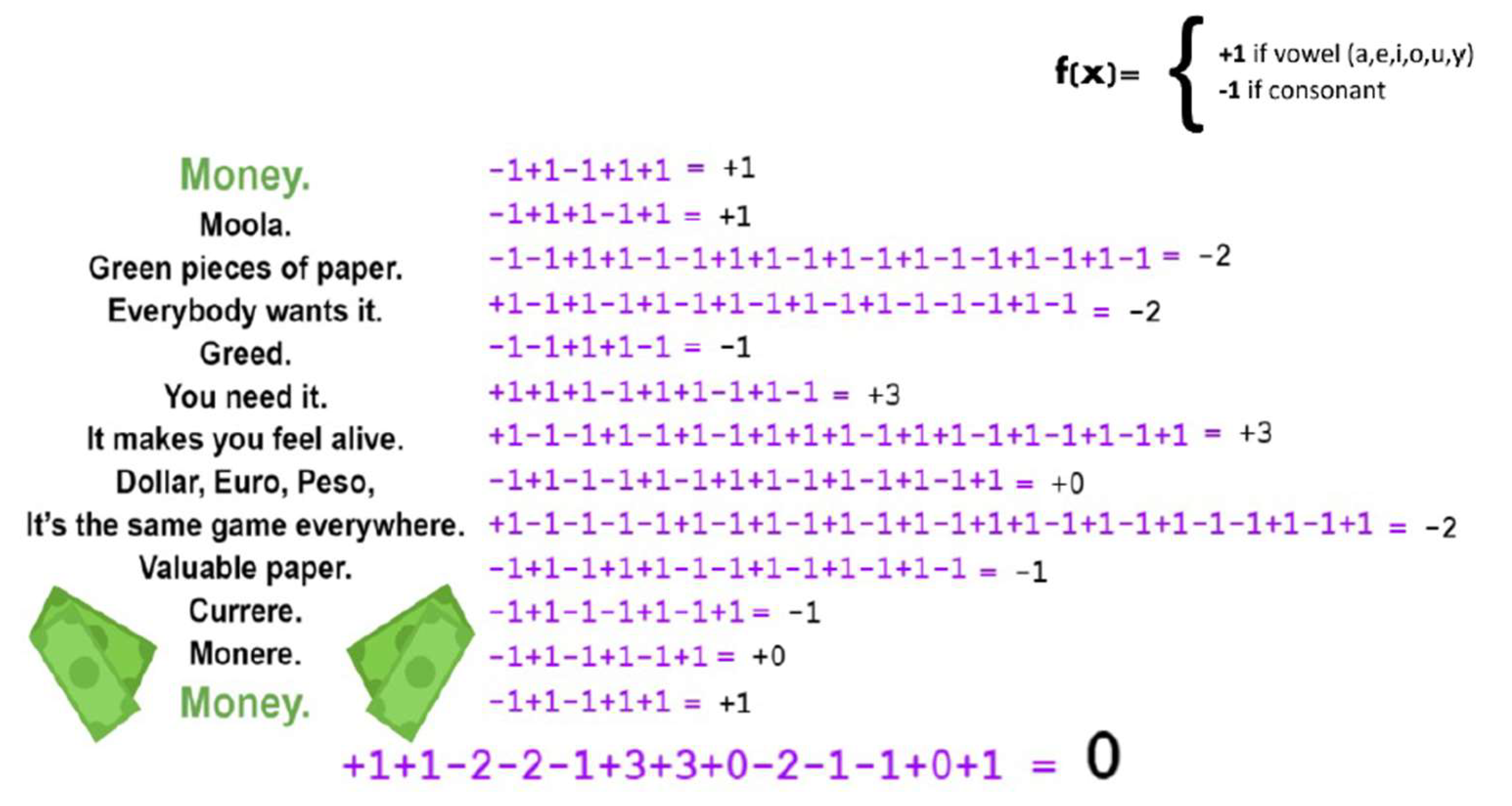

In this context[

17], the author explores the concept of homomorphism through a creative approach to poetry, a first college-level poem. The rule they apply assigns a value of +1 for each vowel (a, e, i, o, u, y) and -1 for each consonant, with the objective of achieving a final total of 0. This presents a challenge, as many common words tend to have more consonants than vowels, making it difficult to maintain a non-negative total while crafting the poem, as depicted in

Figure 17 (c.f., [

17]).

The second college-level poem focuses on modular arithmetic, specifically using base 26 [

17], where each letter of the alphabet corresponds to a number (

). The goal is to create a poem where the total value of the letters adds up to 0 when calculated modulo 26. Additionally[

17], the poet can set different challenges, such as ensuring that each line or even each word of the poem results in the same remainder when divided by 26, adding complexity to the writing process, as shown by

Figure 18 (c.f., [

17]).

In the workshop described[

19], students explored poems that relate to mathematics, such as "Pi" by Wislawa Szymborska and Edna St. Vincent Millay's sonnet, which connects beauty in poetry to mathematical concepts like geometry. The goal was to help students see the connections between math and poetry[

19], encouraging them to reflect on what they find beautiful in mathematics and express those ideas creatively. By creating their own poems[

19], students learned to connect mathematical concepts with real-life experiences and emotions, enhancing their understanding of both subjects.

Figure 19(c.f., [

19]) showcases two poems by students F.T. and M.T., both of whom excelled in mathematics during high school. F.T.'s poem expresses a general sentiment about his feelings towards math, while M.T.'s poem employs more complex mathematical metaphors[

19], such as comparing a lack of interest to a flat line of a linear function and the distance to a loved one to parallel lines. This contrast highlights how poetry can serve as a creative outlet for students to articulate their mathematical experiences and emotions.

The work discussed how emotions play a crucial role in learning mathematics, particularly through two approaches: problem posing (creating problems) and problem solving (finding solutions). This examinedhow different types of situations—like relatable real-life scenarios and visual poems—affect students' feelings and performance in math tasks. The studyfound that using visual poems can inspire future teachers when creating problems, but solving problems based on distant real-life situations tends to yield better results in both understanding and emotional engagement.

Also, the work investigated how emotions and attitudes[

20], known as affective factors, play a crucial role in learning mathematics, particularly in problem-solving and posing. This showcased that students' feelings about math—like their interest, enjoyment, and the value they place on the subject—can significantly influence their understanding and performance. For example[

20], when students find math enjoyable or see its importance, they are more likely to engage and succeed, while feelings of boredom can hinder their learning experience.

In today's digital age[

20], communication goes beyond just written words; it includes various forms like images, videos, and sounds. This shift means that literacy now involves being able to understand and create meaning from multiple types of media[

20], not just traditional texts. As a result[

20], education should adopt a multimodal approach, helping students develop skills to interpret and express ideas through diverse formats, which enhances their understanding of the world around them.

The rise of visual or experimental poetry has made it more popular and useful in educational settings, especially as students' reading habits have changed with the influence of social media and digital content. This type of poetry combines different forms of expression[

20], making it engaging for students, who enjoy both reading and creating it. Additionally[

20], visual poetry connects with mathematics by using artistic representations of numbers, helping to make mathematical concepts more relatable and emotionally resonant, as demonstrated by the work of groups like "Colectivo Frontera de Matemáticas."

Problem 1 involves a real-life scenario that is relevant to the students[

20], where they must solve a mathematical problem related to a mobilization of students. Using an explanatory text and a scaled aerial image, students are required to estimate answers while applying the Pythagorean theorem. This problem also encourages them to make assumptions and perform estimations, which aligns with the concept of a Fermi problem—an estimation technique used to find approximate solutions to complex questions, as in

Figure 20(c.f., [

20]).

Problem 2 involves a mathematical scenario that uses the Pythagorean theorem but is set in a geographical context that is distant from the students' everyday experiences[

20]. The problem is based on a mountain that the students may know about, but since it is located in the Canary Islands[

20], they might struggle to visualize its actual size and details. This distance from their reality can make it more challenging for them to apply their mathematical knowledge effectively, as in

Figure 22 (c.f., [

20]).

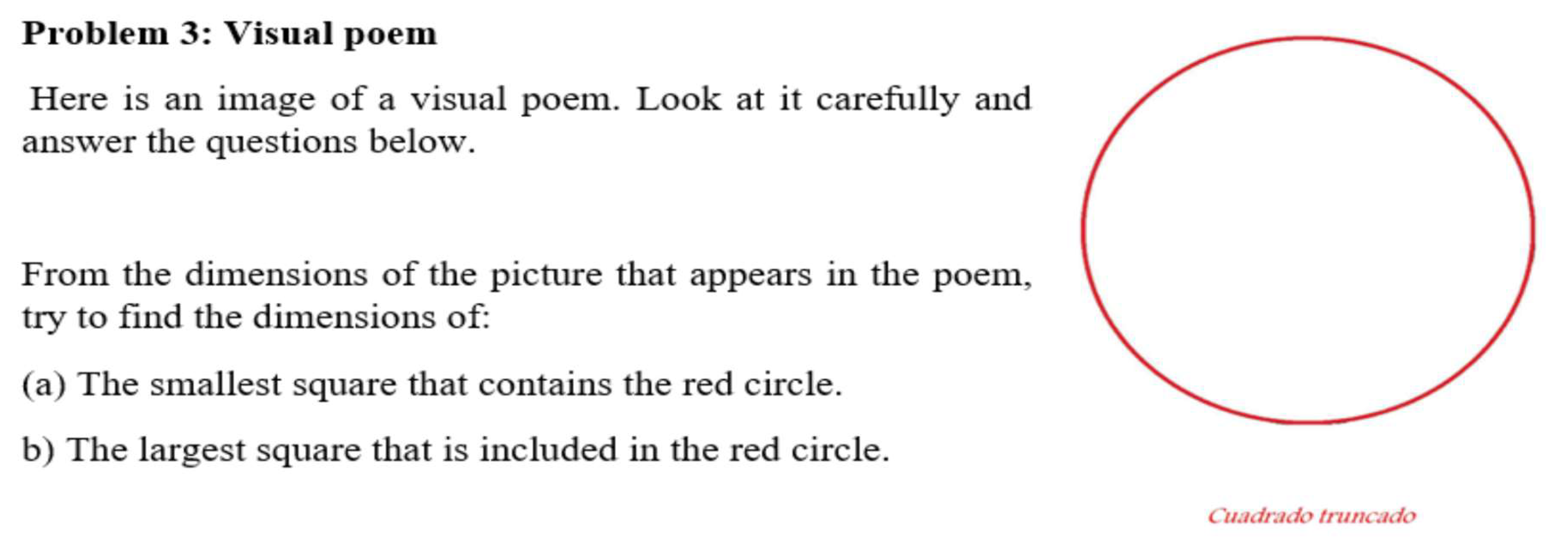

Problem 3 involves using a visual poem by Antonio Ledesma to create a mathematical problem related to the Pythagorean theorem[

20]. The poem features an image of a circle and includes the phrase "truncated square," which likely serves as a prompt for students to explore geometric relationships[

20]. This approach aims to engage students creatively while applying mathematical concepts in a unique context, as il;ustrated by

Figure 22 (c.f., [

20]).

In [

21], the authors explained how "I poems," which are a part of the Listening Guide method, can help researchers explore the different aspects of a student's mathematical identity. By analyzing an interview with a student[

21], they show that a student's mathematical identity is complex and can change over time, influenced by various external voices and experiences. Additionally[

21], they highlight that incorporating drawings into this method can further enrich the understanding of how students perceive and express their relationship with mathematics.

On another diffetrent note[

21], the authors discussed their analysis of interviews conducted with students about their experiences learning mathematics as part of a larger ongoing study. They used a method called the Listening Guide[

21], which involves four steps to deeply understand participants' voices and identities, focusing on their personal narratives. By analyzing one participant's interview[

21], they aim to reveal the complexities of her mathematical identity and how it is shaped by her experiences and environment.

In the first step of the Listening Guide method[

21], called "Listening for the Plot," researchers listen to an interview recording multiple times to understand the overall story and key themes shared by the participant, Elizabeth. They observed that Elizabeth often talked about herself [

21], but her descriptions seemed inconsistent or contradictory, indicating a complex self-narrative. Additionally[

21], they noted that she mentioned important figures in her life, such as her parents and teacher, which helped shape her story.

In the second step of their analysis[

21], the researchers created an "I poem" from Elizabeth's interview data, focusing on her personal expressions and feelings. They collaborated to determine which parts of her statements to keep and added clarifying remarks when necessary to maintain context. The resulting poem emphasizes Elizabeth's first-person perspective[

21], particularly highlighting her emotions during math tests through the repetition of "I" statements, which reflects her identity and experiences.

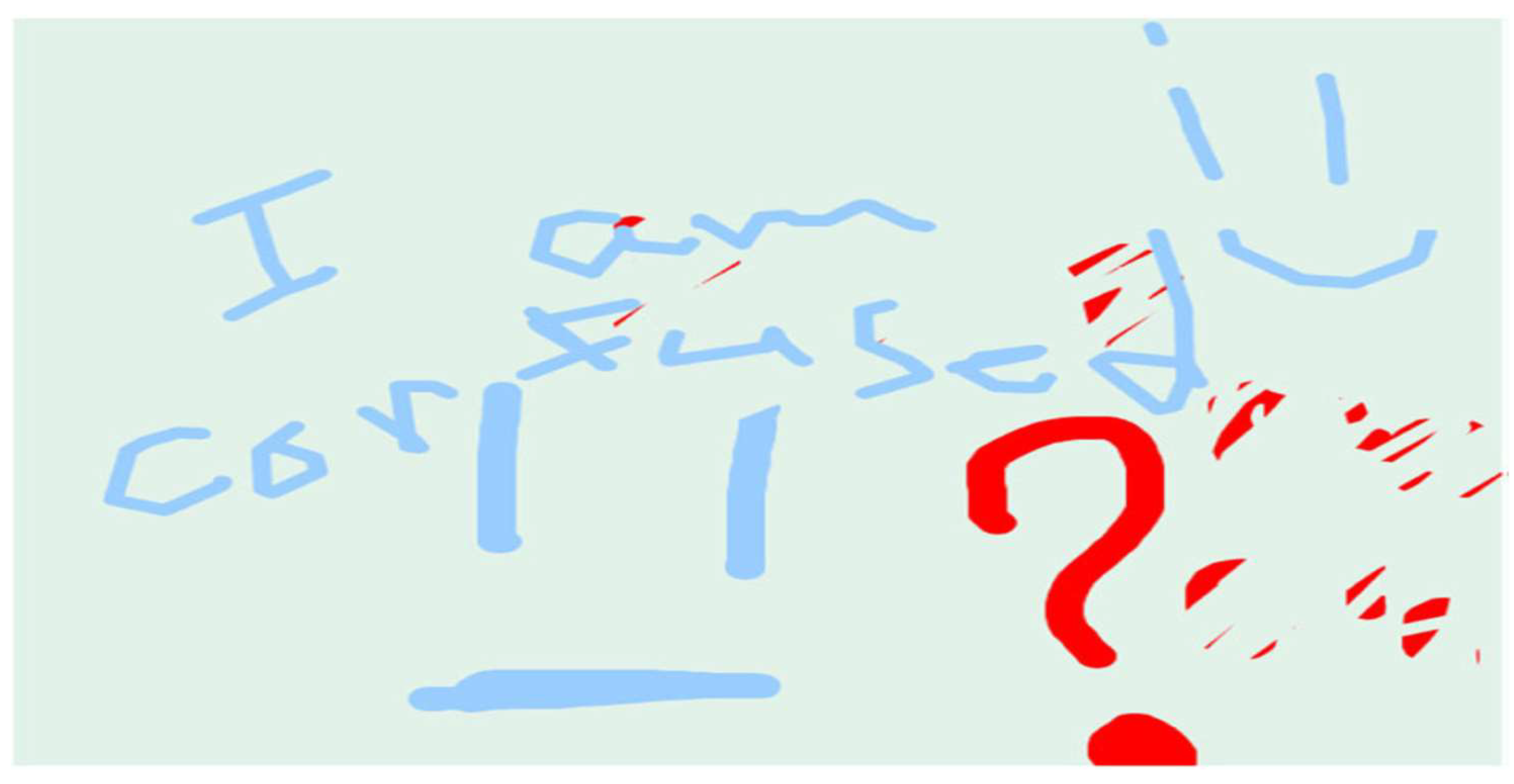

In this text, the authors describe their collaborative process of analyzing Elizabeth's dialogue to create an "I poem," which captures her personal feelings about doing mathematics tests. The poem uses repeated "I" statements to emphasize Elizabeth's individual perspective and how she sees herself in relation to her experiences. This approach allows for a deeper understanding of her emotional state and identity as a learner, particularly in the context of her struggles with mathematics, as in

Figure 23(c.f., [

21]).

The second excerpt from Elizabeth's I poem, as in

Figure 24 (c.f., [

21]), highlights her internal conflicts regarding her identity in mathematics, showing that she experiences both struggles and contradictions in how she views herself as a learner. This part of the poem reveals deeper feelings about her mathematical abilities and the pressures she faces, indicating that her self-perception is complex and multifaceted. By analyzing this excerpt, researchers can better understand the nuances of Elizabeth's mathematical identity and the emotional challenges she encounters.

The Listening Guide process consists of four steps that help analyze participants' identities through their narratives. In this study, the researchers added a drawing component to better capture the complexities and contradictions in Elizabeth's feelings about mathematics. When asked to illustrate her emotions using an iPad, Elizabeth's drawing revealed her conflicting voices, highlighting her struggles and insecurities alongside her desire to meet expectations, as visualized by

Figure 25 (c.f., [

21]).

However [

22], it is not poetry in mathematics or mathematics in poetry that piques our curiosity as much as mathematics and poetry do.the exhibition of the outcomes of human imagination through the merger of the two as equals. "The mathematics are generally regarded as the very antipodes of poetry," said Dr. Thomas Hill[

22], expressing the marriage of metathesis learning and poetry (poiesis, creation). However, since both poetry and metathesis are products of the imagination, they are the closest of their kind. Poetry is an invention[

22], a fabrication, and a work of fiction; an admirer of mathematics has referred to mathematics as the most sublime and stupendous of fictions. Indeed[

22], in addition to mathesis, or learning, they are also poiesis, or creation.

Verses[

22], which best exemplify "the power of thought." The connection between the verse of letters and the versed sine (also known as the "turned sine"), the umbra versa (also known as the "turned shadow"), and the vertical of geometry is not merely a matter of etymology. Every turn has both a form and a sentimental component.

All suggestions of the poetic form of algebra are meaningless to someone who cannot appreciate the rhythm of symmetrical expressions like

and

However, to someone whose master was a poet, such expressions combine perfect symmetry, perfect rhythm, and a perfect geometric picture, like the Parthenon's facade. In the combined precious Schematic writings 26 and 27 (c.f., [

22]), more elegant decriptions of poetic mathematics and mathematic poetry.

Schematic writing 27.

A musical-based approach to teach mathematics

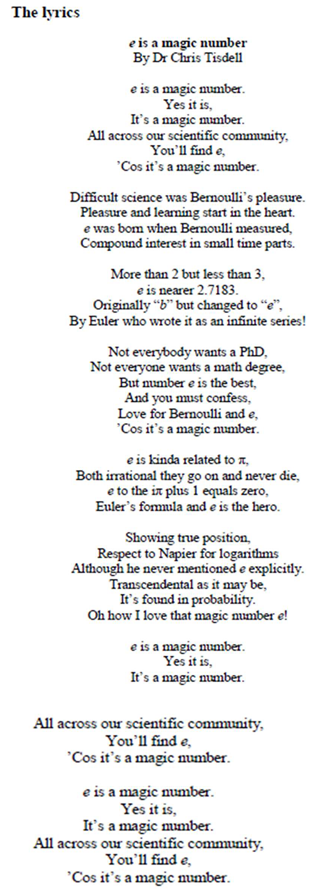

The authors explored how certain musical scales, known as harmonic sets, can be best matched with a specific tuning system called the chromatic just scale, which is based on pure intervals. They developed a method to identify which tuning systems, or temperaments, work well with this scale, finding that temperaments with 12, 19, 22, 24, 31, 34, 41, and 53 divisions are effective, with 53 divisions being the most accurate. They also discoveredthat major scales are better represented than minor scales when fitting these temperaments, and that using evenly spaced notes across an octave is not the best approach for finding suitable tunings, which aligns with findings in world music studies.

The concept of harmonicity in music comes from wave physics[

23], where certain frequencies sound good together because they are related by simple ratios. For example[

23], a perfect octave occurs when one frequency is double another, while a perfect fifth has a frequency ratio of 3:2. These relationships [

23]help create musical intervals, like major and minor chords, which are foundational to Western music theory and are represented in the twelve-tone chromatic scale.

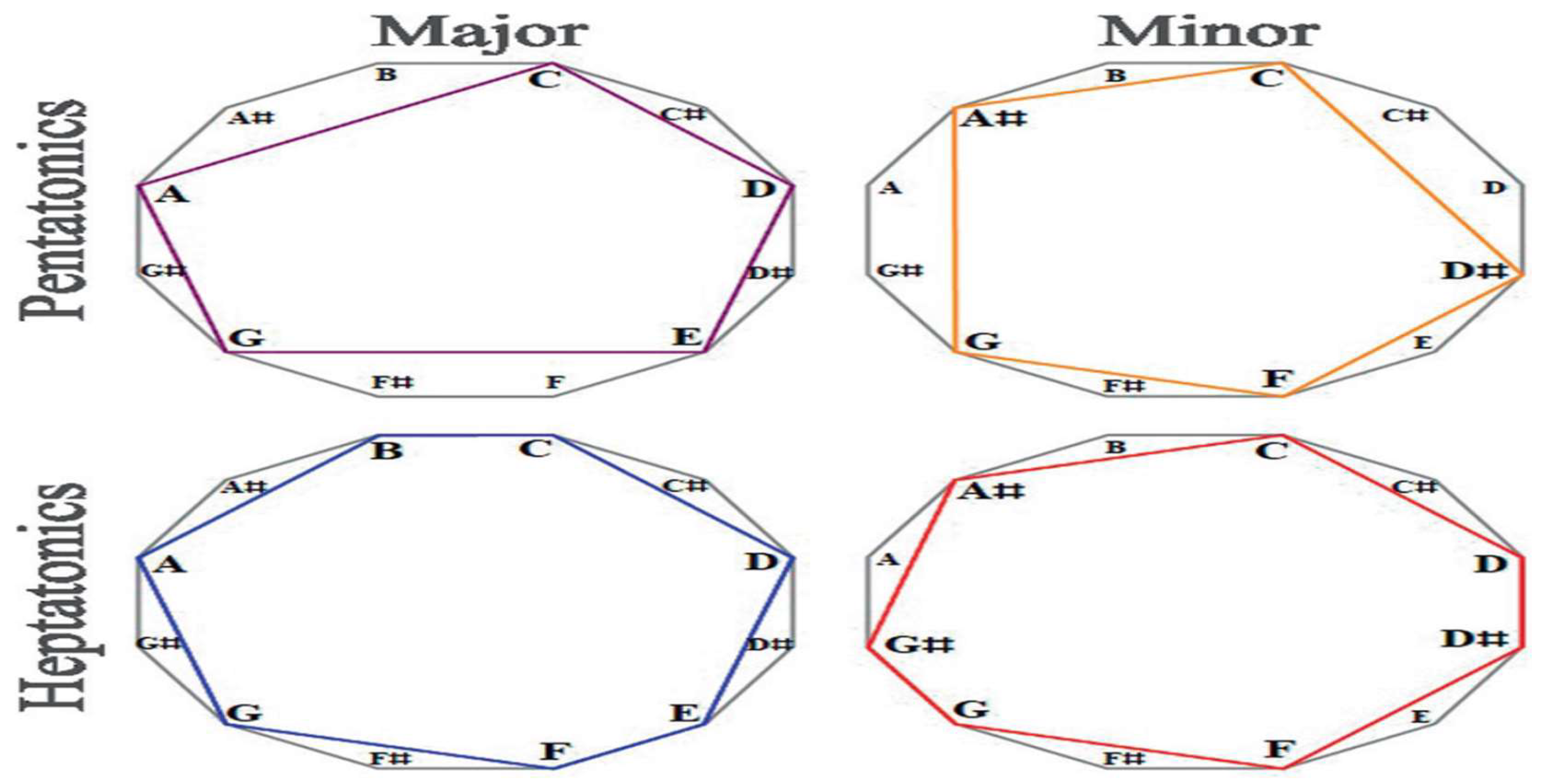

Harmonic scales are specific groups of musical notes selected to create pleasing sounds and combinations[

23], and they have unique mathematical properties that make them interesting for musicians. In Western music, the most common harmonic scales are pentatonic scales, which have five notes[

23], and heptatonic scales, which have seven notes. The major and minor scales are examples of these, and they can be visually represented as polygons inscribed in a dodecagon[

23], where each point corresponds to a specific musical interval, as in

Figure 28 (c.f., [

23]). The heptatonic minor scale, often referred to as the natural minor scale, is one of the most common scales in Western music and is characterized by a specific pattern of intervals between its notes. These diagrams help musicians understand the relationships between the notes in these scales, making it easier to compose and improvise music.

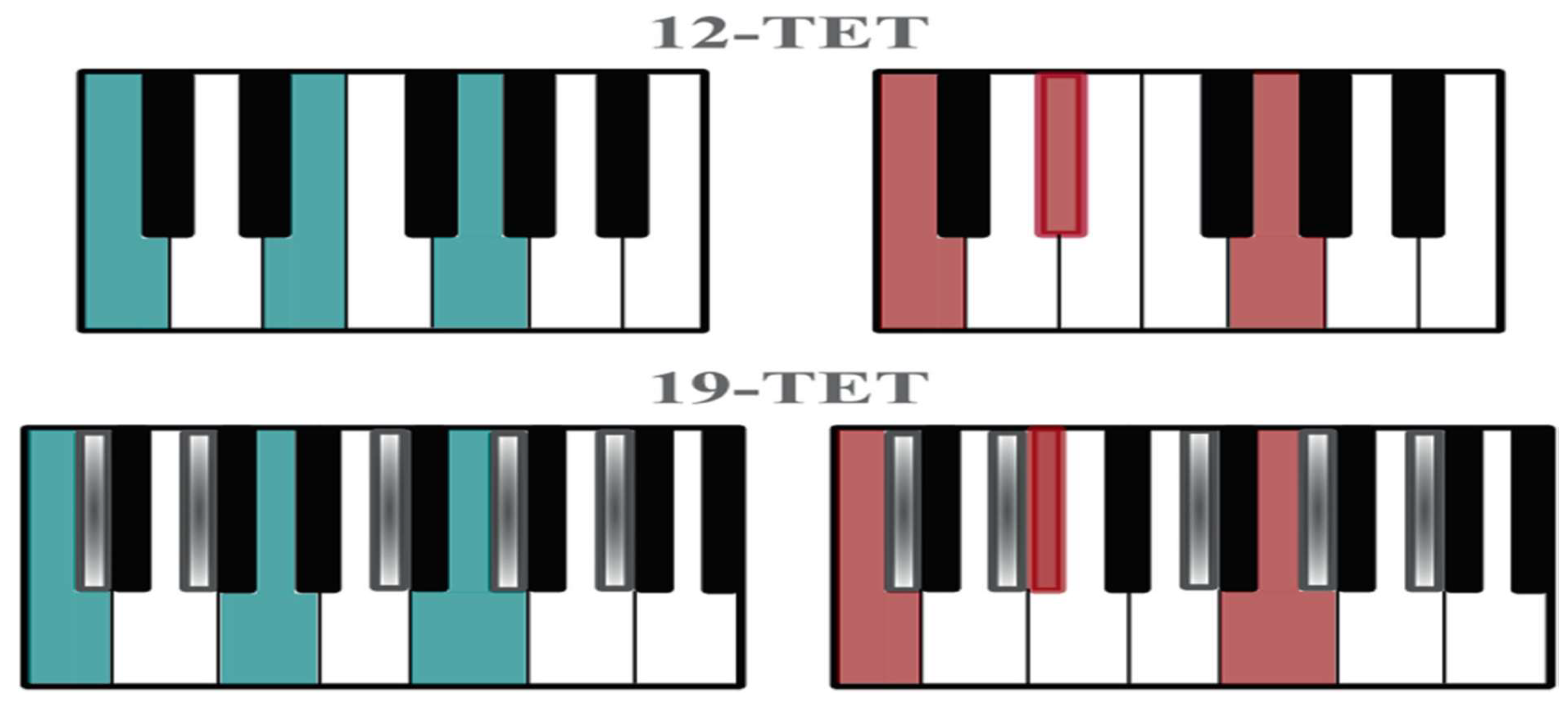

The desire for musicians to play pieces in different keys[

23], along with advancements like the invention of the piano, led to the adoption of equal temperament (ET) as a standard tuning system. Equal temperament organizes musical notes in a way that maintains a consistent ratio of frequencies[

23], specifically the octave ratio of 2:1, across all keys. The most common version, 12-TET, divides the octave into 12 equal intervals, allowing for flexibility in playing different pieces[

23], while alternative tunings like 19-TET aim to improve the sound of certain intervals, such as major and minor sevenths, as illustrated by

Figure 29 (c.f., [

23]).

In 12-TET, the octave is divided into 12 equal parts, which allows for playing in different keys but can lead to slight tuning discrepancies. In contrast, 19-TET divides the octave into 19 smaller intervals, providing more precise tuning options and allowing for a richer harmonic exploration, as shown in the colored representations of C major and minor chords for each system.

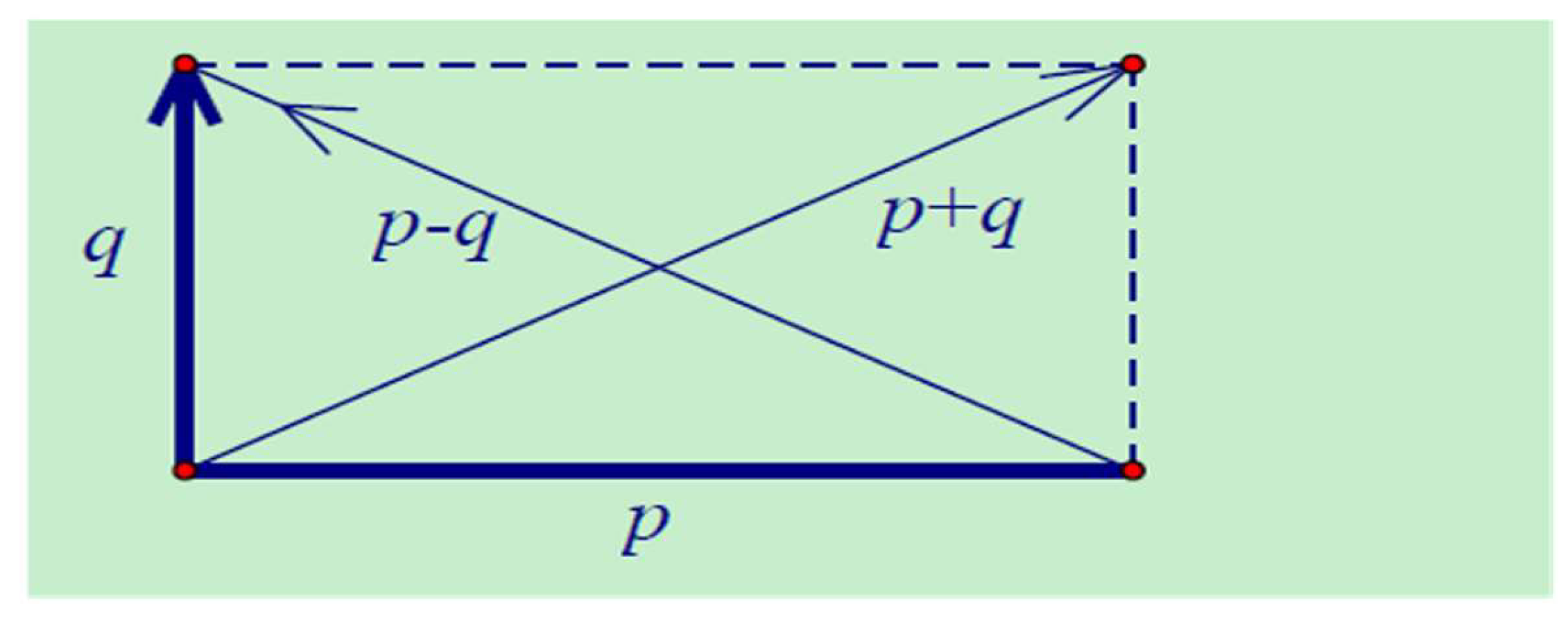

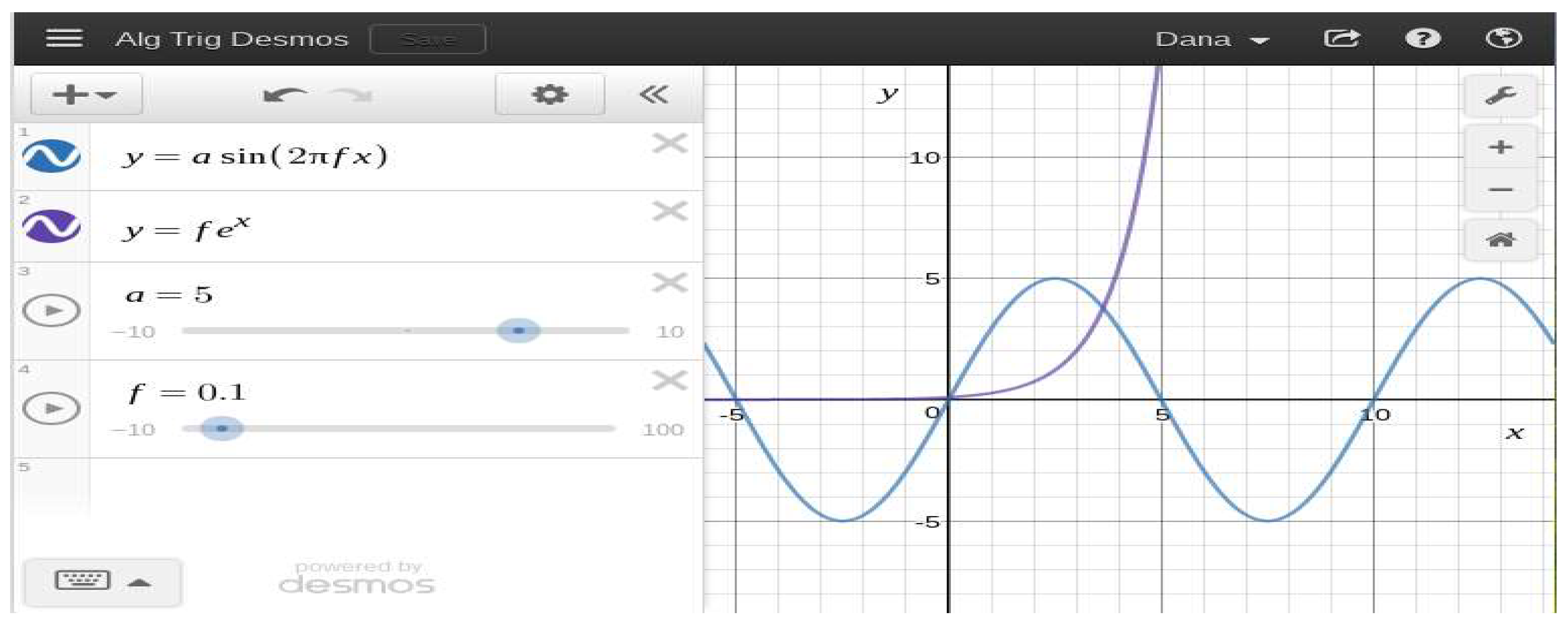

Music is an essential part of human experience and has played a significant role in the author's life[

24], influencing their interests and activities from a young age. As they transitioned into an academic career[

24], they felt it was natural to explore how music could enhance their teaching of mathematics, a subject they are passionate about. The author noted that many mathematicians also have a strong connection to music, and while music theory isn't formally grounded in mathematics, there are mathematical principles that describe musical sounds, such as the numerical ratios found in musical scales.

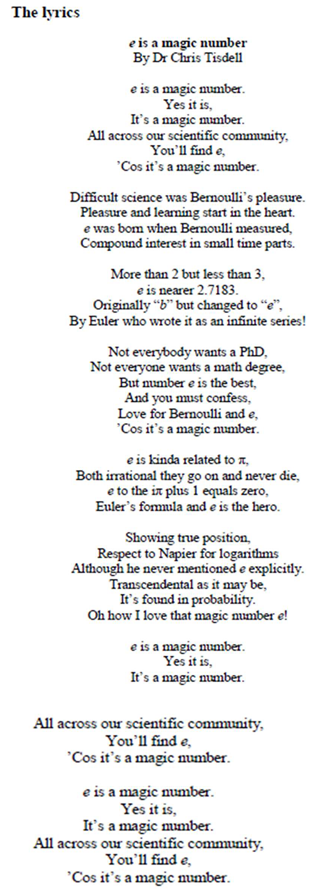

The number is a key mathematical constant, roughly equal to 2.7183, that plays an important role in calculus and various mathematical applications. One way to understand is through its connection to compound interest, where it represents the limit of a sequence that describes how money grows when interest is compounded continuously. This concept is foundational in mathematics and helps illustrate how exponential growth works in real-world scenarios.

The number

is written as

The number

[

24], approximately equal to 2.718, is often overshadowed by the more famous number π, which has a long history and is widely recognized in mathematics and culture. While π is celebrated with events like Pi Day and has inspired numerous books and songs, e is less known because it is more closely related to advanced topics like calculus[

24], which students typically encounter later in their education. The lyric "

is a magic number" aims to highlight the importance of

and promote a broader appreciation for it, challenging the dominance of π and encouraging educators and mathematicians to explore diverse mathematical concepts.

The human sense of hearing has extraordinary abilities to recognise patterns, yet listening has not received much attention as a method of pattern-finding [

26]. Even Einstein never considered equations[

26]; instead, he sensed or saw the answers, which he later transformed to convey to others. Given the multimodal nature of human cognition[

26], auditory sensory experiences may add to the semantic richness of mathematical conceptions, but they have not received much attention in the field of mathematics education[

27].

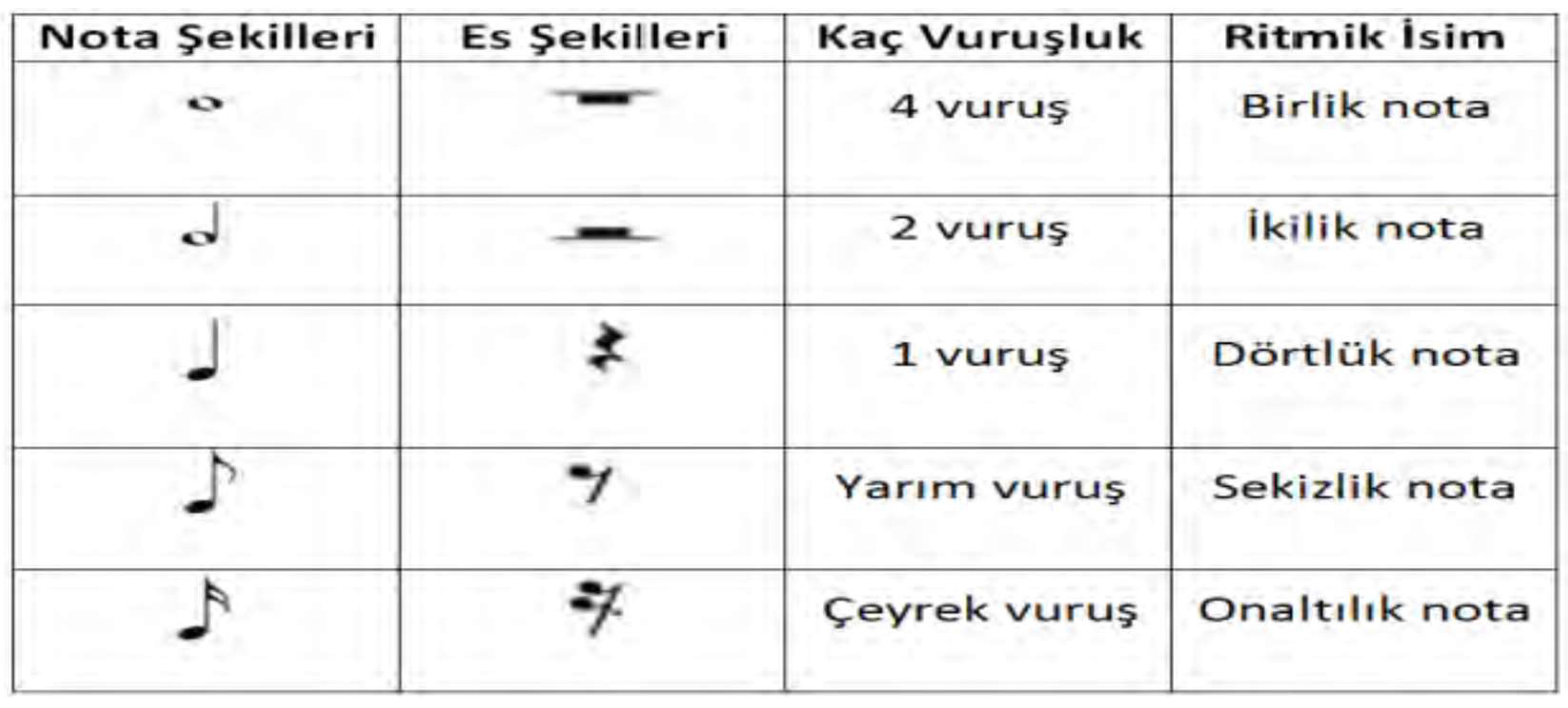

Play the Legacy Prototype and My Math (PMM) Concept[

28]. Students in PMM develop, read, and perform musical compositions while honing their mathematics skills. An introductory lesson on creating and reading music using just numbers, arithmetic, fractions, algebraic formulas, and bar graphical representations is the first step in the educational game for mathematical musicians[

28]. Students' goal in the game is to continue writing and playing music, and the key to doing so is finishing courses[

28], figuring out mathematical problems, and conquering mathematical musical obstacles. During our initial development cycle, we created a Composition Tool that lets students create their own rhythms by arranging bar graphs with customisable percussion sounds. An algebraic notation reference is updated as the graphical beats are altered[

28], allowing pupils to relate what they hear and sense the beauty of mathematics.

Teachers' Specific Objectives. Features that allow teachers to work on and thoroughly explore fraction issues should be taken into consideration by PMM [

28]. The authors have added a new notations tab to their Composition Tool, which is also the centrepiece of the new Music Lab in the Tools area, where educators can consult decimal, percentage, and algebraic notation. Teachers can choose to work with up to eight graphical bars (wholes) and split them into up to 50 parts using the Fractions Lab module that we created. This will enable the teachers to address more difficult least-common multiple cases and work more flexibly with larger denominators. For both the Music and Fractions Labs, users can now depict mixed fractions by linking the active fractions of two graphical bars.

In [

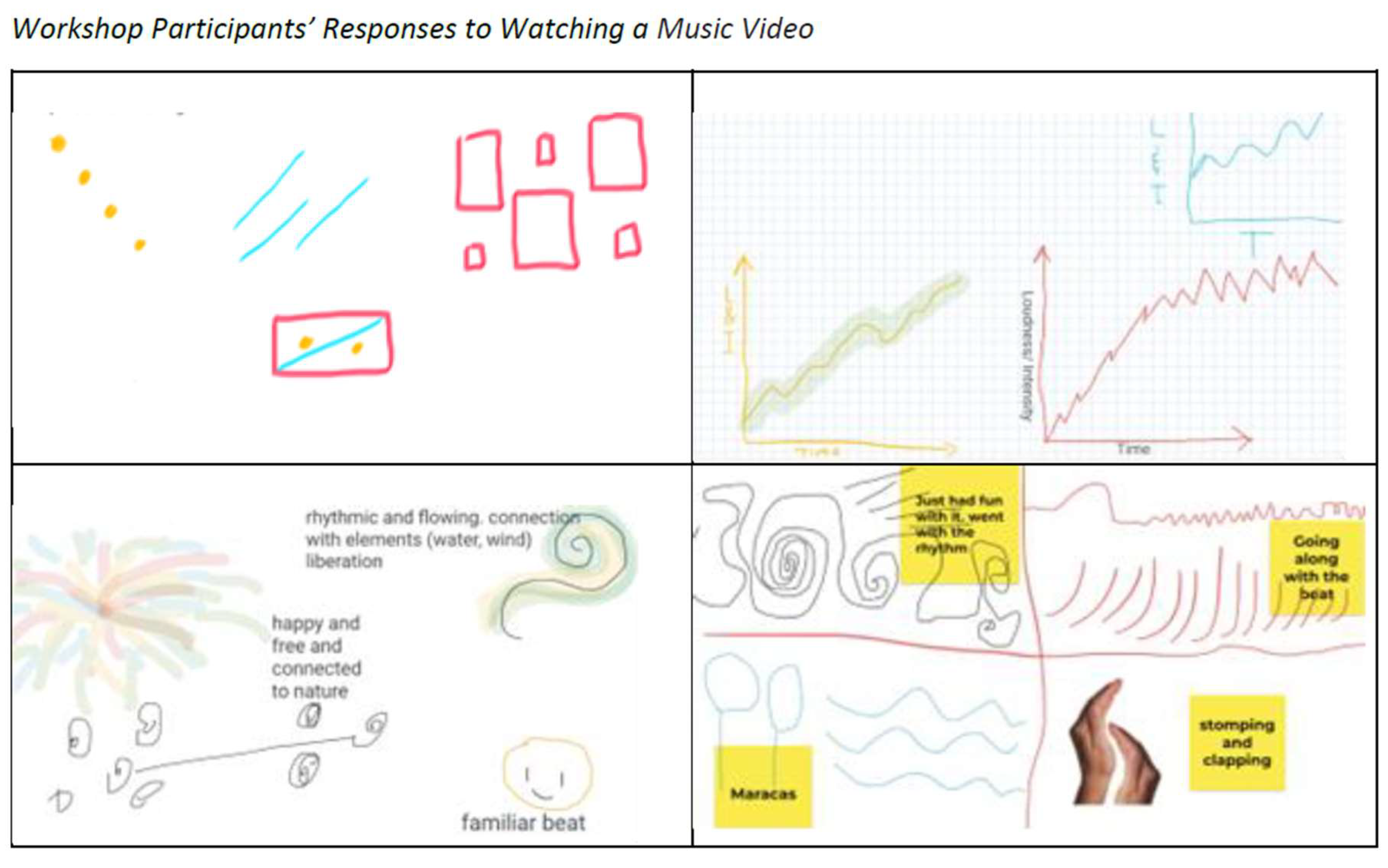

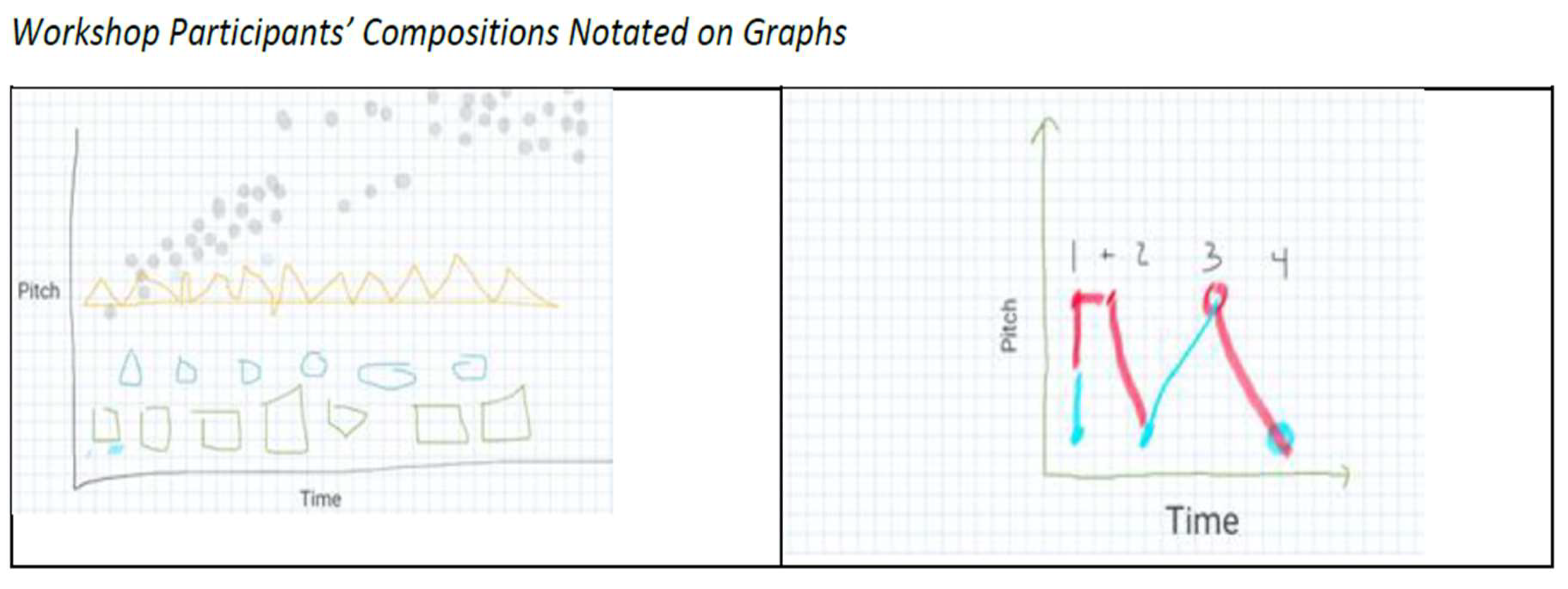

29], culturally relevant content and inclusive tools can create fair and innovative learning environments, particularly in the fields of music and mathematics were undertaken. The authorshared his experiences of designing a workshop that combines these two subjects for preservice teachers, emphasizing how this approach encourages collaboration, inquiry, and creativity. By participating in these interdisciplinary tasks[

29], teachers can enhance their musical and mathematical abilities while also developing important social skills and confidence.

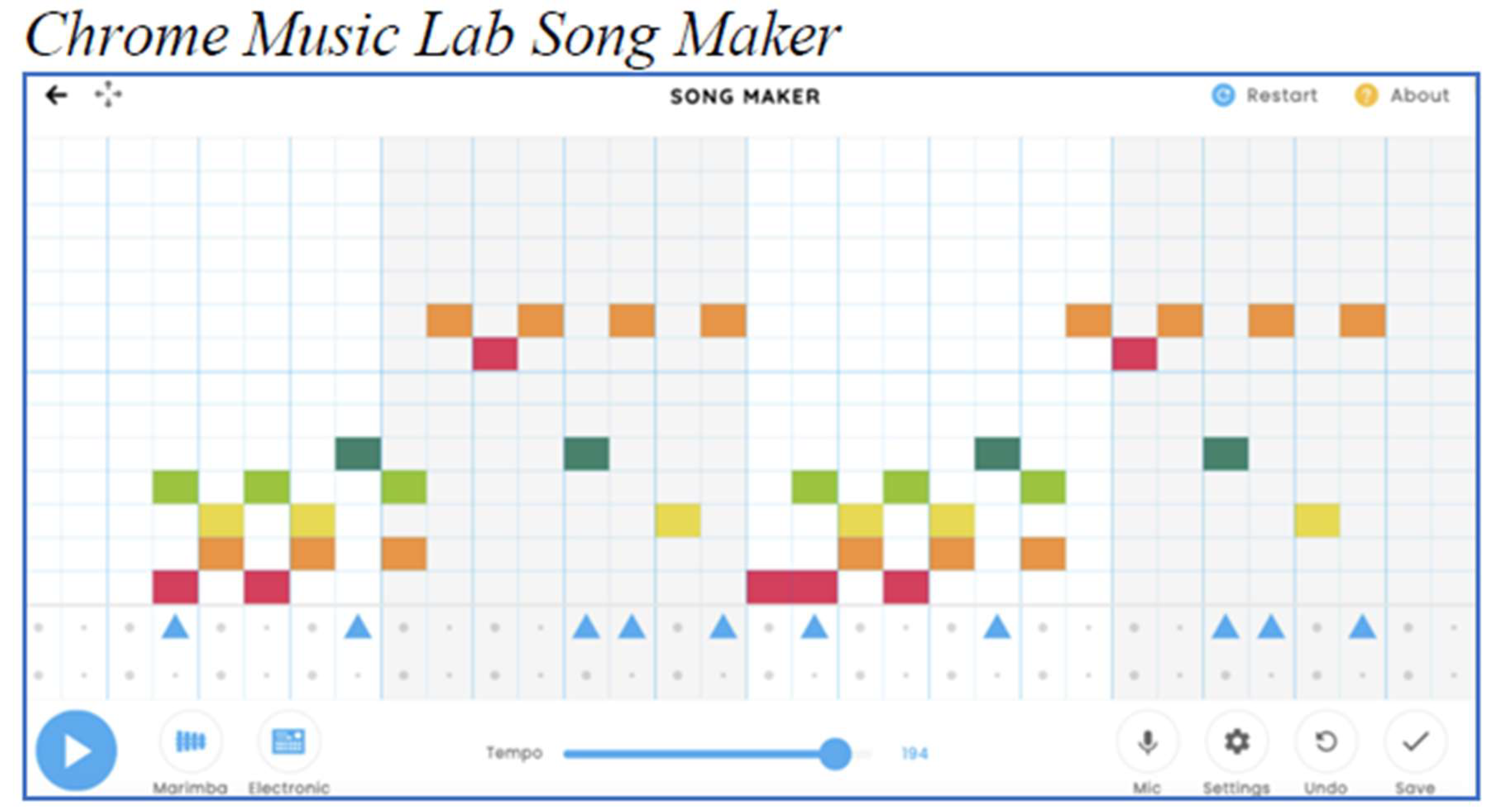

Both traditional musical instruments and modern music technology provide students with various ways to express themselves creatively[

29]. Traditional instruments often resonate with students' personal interests and cultural backgrounds, such as Latin percussion instruments being popular in certain New York City neighborhoods due to their presence in local music[

29]. Additionally[

29], virtual and electronic tools like Chrome Music Lab allow for customization and adaptability, enabling students to explore music in ways that align with their individual needs and preferences, as depicted by

Figure 30 (c.f., [

29]).

In a collaborative learning environment, preservice teachers engaged in music activities that helped them understand how music relates to fundamental human experiences, such as breathing, walking, and speaking, as noted by jazz pianist Vijay Iyer. While explaining their thoughts on a music video through various forms like math, pictures, and improvised music, they connected their personal experiences with music and math to their cultural backgrounds. This process allowed them to see the deeper relationships between these disciplines and their own lives(See

Figure 33(c.f., [

29])).

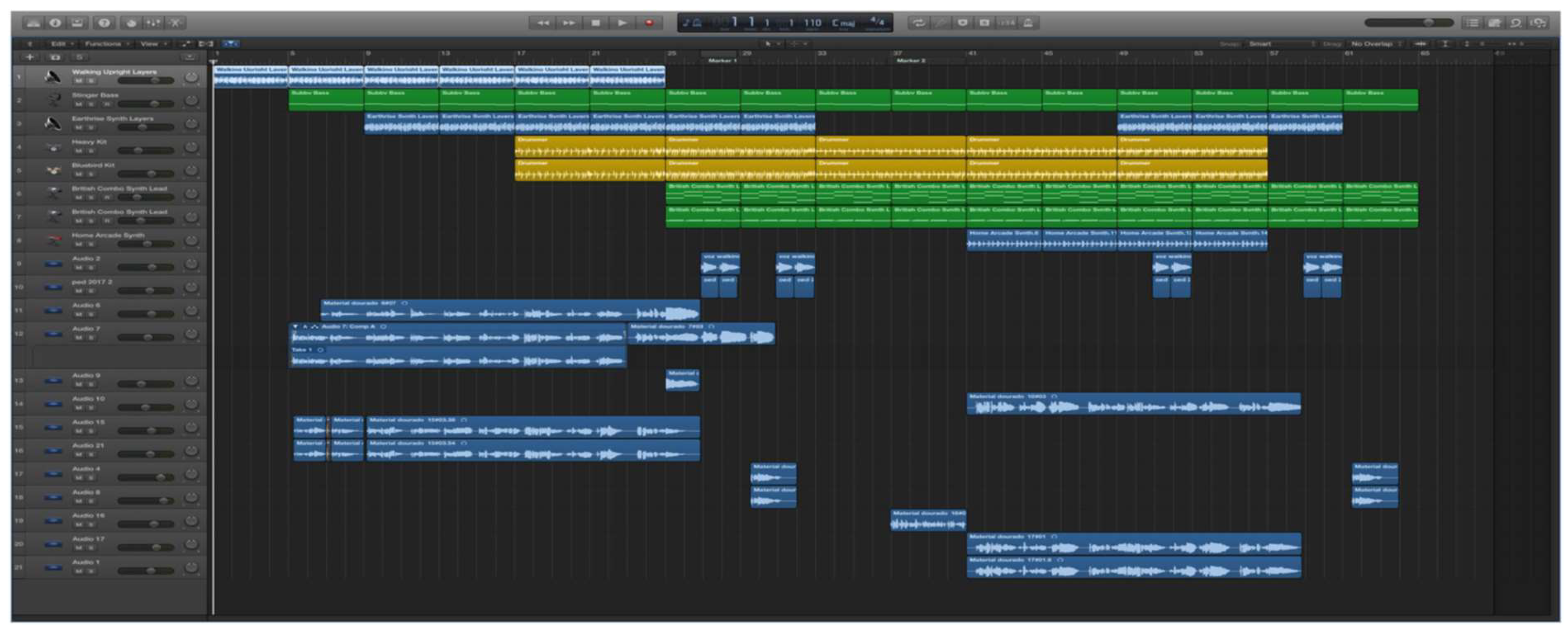

Figure 35 (c.f., [

30]) shows a screenshot of the Logic Pro X music software, which was used by education majors to create a mathematical song called "Golden Material" during research activities in 2017. This project involved exploring mathematical concepts, specifically related to place value manipulatives, through music production. The interface displays various tracks and instruments, highlighting how students can engage with mathematical ideas while composing music.

In this research, the authors argued that music and mathematics are interconnected, with mathematics having an artistic side and music being grounded in mathematical principles. The study suggested that music can be an effective teaching tool for mathematics, helping students understand concepts like fractions through musical notes and rhythms. Additionally[

30], preservice teachers reported positive experiences when integrating music into math lessons, finding it a refreshing alternative to traditional teaching methods.

In visual arts, artists like Da Vinci and Mondrian used mathematical concepts such as the golden ratio and geometric shapes to create their works[

30], showing a connection between art and math. Additionally[

30], the history of mathematics and music has been intertwined, starting from the Pythagoreans, who studied musical harmonics using simple fractions, to modern techniques like Fourier analysis, which helps automate music processing. This highlights how both fields influence and enhance each other over time.

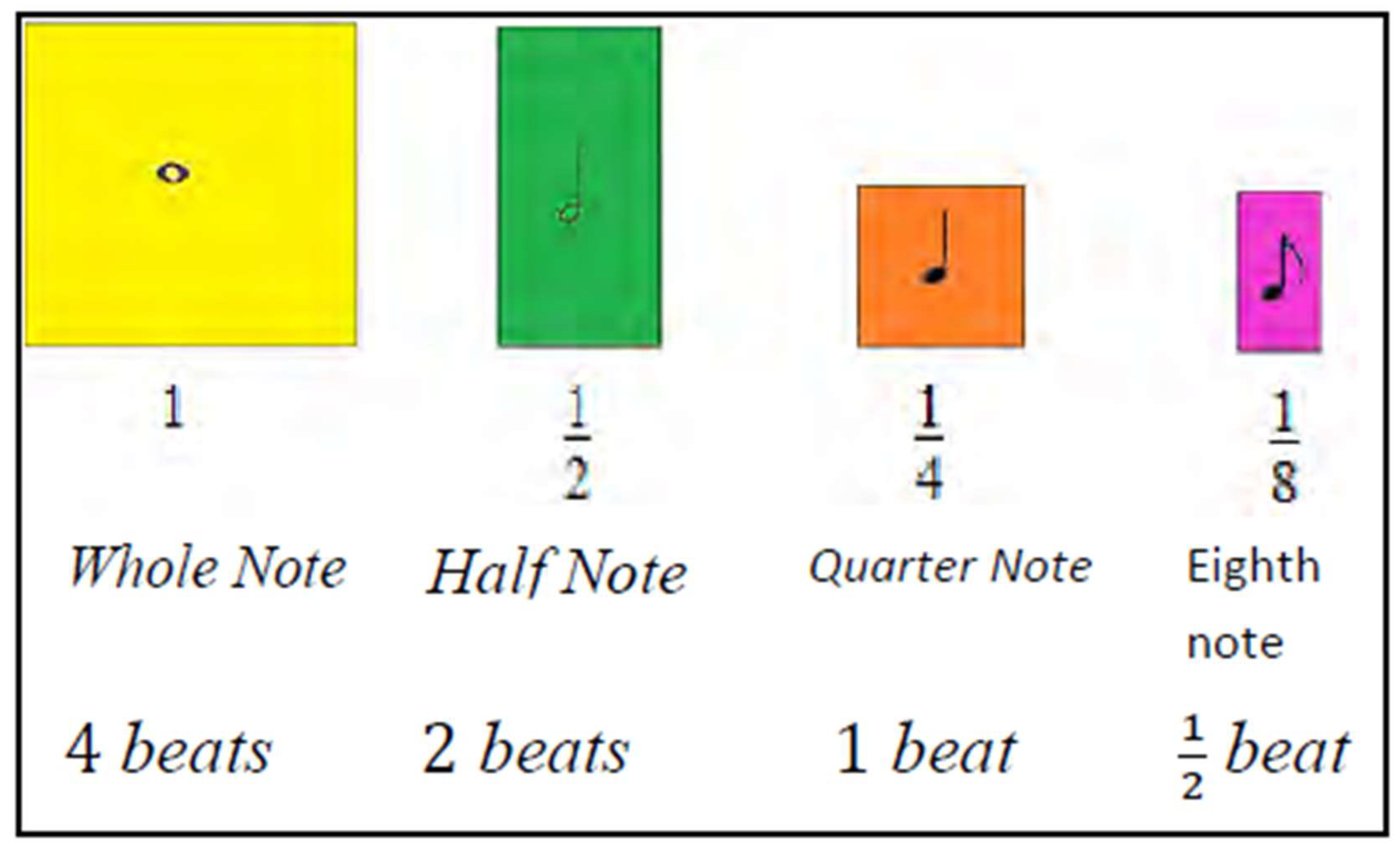

This explains how music can be effectively used as a teaching tool for mathematics[

30], particularly in helping students understand fractions. For instance[

30], by exploring the time values of musical notes, third-grade students could learn about fractions and their operations through different representations. This approachnot only engages students but also makes mathematical concepts more relatable and easier to grasp, as visualized by

Figure 38 (c.f., [

30]).

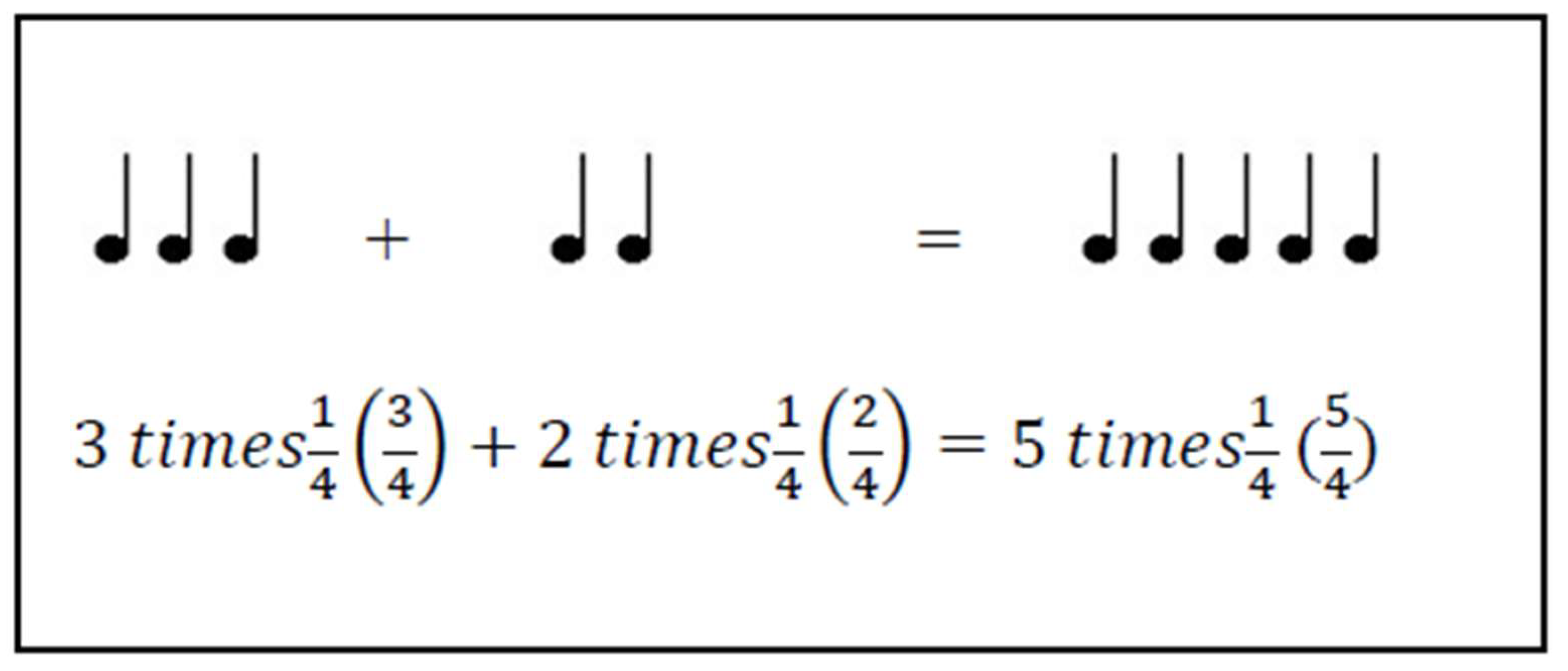

In the classroom[

31], students learned about musical measures, specifically how different time signatures like 3/4 and 3/2 relate to the number of notes they contain, such as quarter and half notes. When asked about a 4/4 measure, they correctly identified it as consisting of four quarter notes. To reinforce their understanding of note durations, the teacher used colored paper to represent different note values and had the students practice clapping to the rhythm of whole notes, half notes, and quarter notes, helping them connect the visual representation of notes with their rhythmic values, as in

Figure 39 (c.f., [

31]).

In music[

31], rests are symbols that indicate periods of silence, and they have specific durations that correspond to the lengths of notes. For example, a quarter rest lasts as long as a quarter note, while a half rest lasts as long as a half note.

Figure 40 (c.f., [

31]) in the context illustrates the different shapes of notes and rests, along with their respective beat times and names, helping students understand how to incorporate both sound and silence into their musical performances.

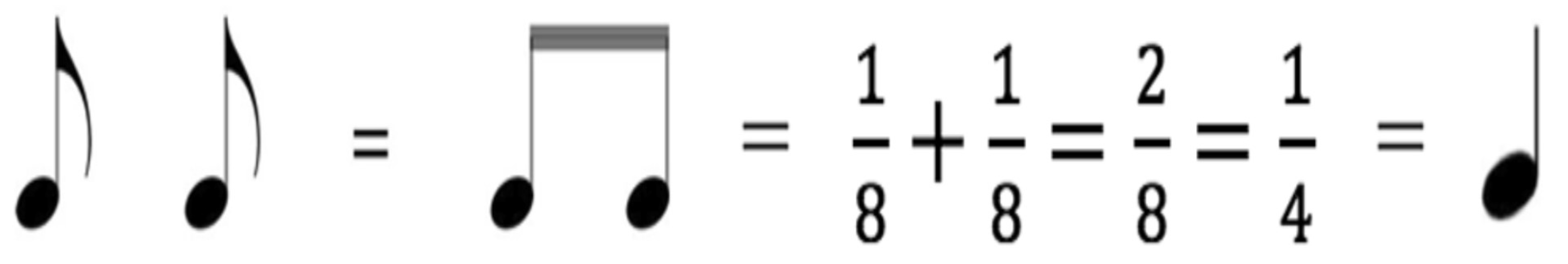

In the context of the lesson, when students add two fractions with the same denominator, such as

they recognize that

represents three quarter notes and

represents two quarter notes. By adding these fractions, they calculate the total as

which corresponds to five quarter notes. This exercise reinforces their understanding of both musical notation and fraction addition, linking the concepts of music and mathematics effectively, as depicted by

Figure 41 (c.f., [

31]).

Here is an example of a conversationfrom this point in the lesson between the teacher and the students:

Teacher: One quarter note plus another quarter note adds up to what?

S1: Two quarter notes are involved.

Teacher: Could you give us the fraction of the two quarter notes?

S2: Teacher : How long do one eighth note and two eighth notes last together? Who wants to use fractions to describe it?

S3: The fraction is , and it is three eighth notes, Teacher.

The curriculum design process involves combining different subject [

31], like music and mathematics, to enhance students' learning experiences. In this study with fifth-grade students[

31], activities were created that linked musical concepts, such as notes and beats, to the mathematical operations of adding and subtracting fractions. This interdisciplinary approach not only increased student motivation and engagement but also helped them understand fraction operations more effectively[

31], demonstrating the positive relationship between music and math education.