Submitted:

23 December 2024

Posted:

24 December 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

3.1. ML Models

3.1.1. Linear Regression (LinReg)

3.1.2. Decision Tree (DT)

3.1.3. Random Forest (RF)

3.1.4. Gradient Boosting (GB)

3.2. Hyperparameter Optimization

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

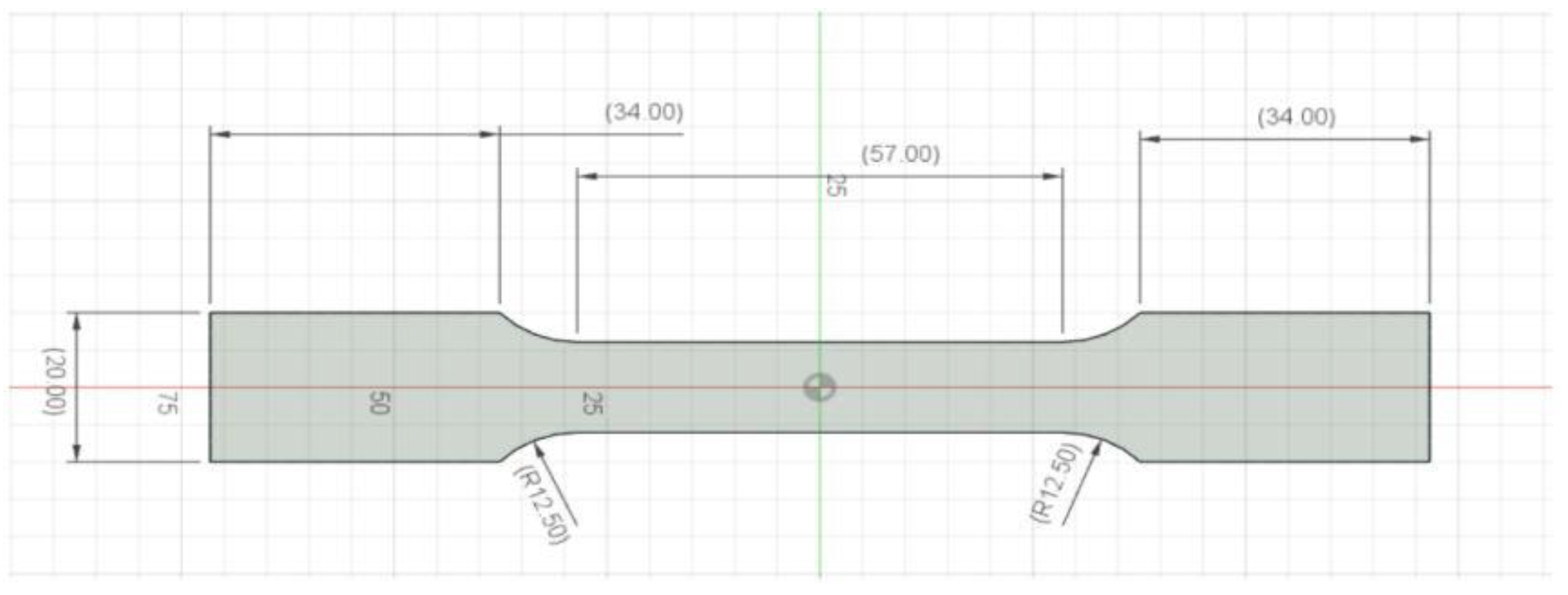

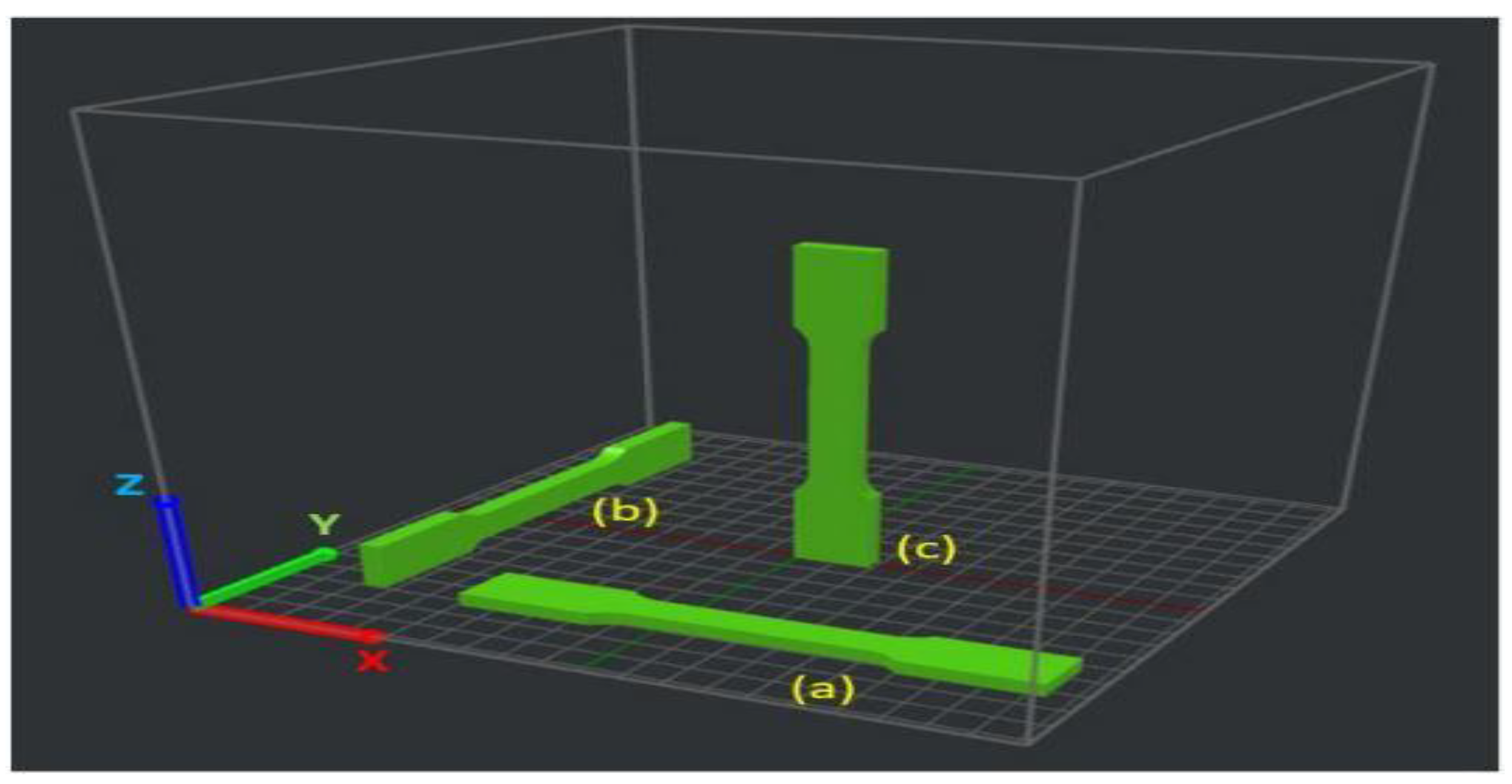

3.4. Data Collection and Preprocessing

3.5. Sustainability Metrics

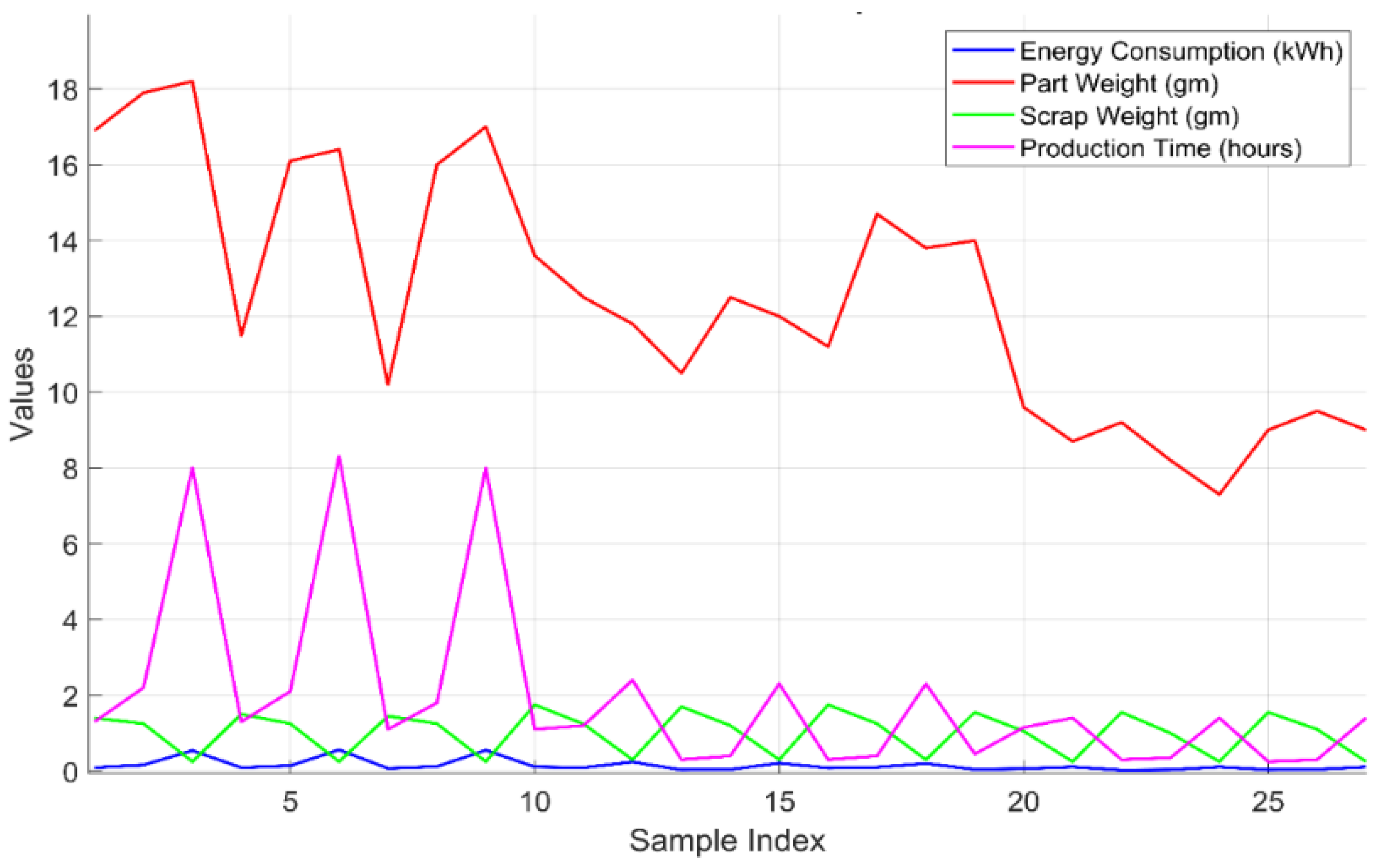

3.5.1. Energy Consumption (EC)

3.5.2. Part Weight (PW)

3.5.3. Scrap Weight (SW)

3.5.4. Production Time (PT)

4. Results and Discussion

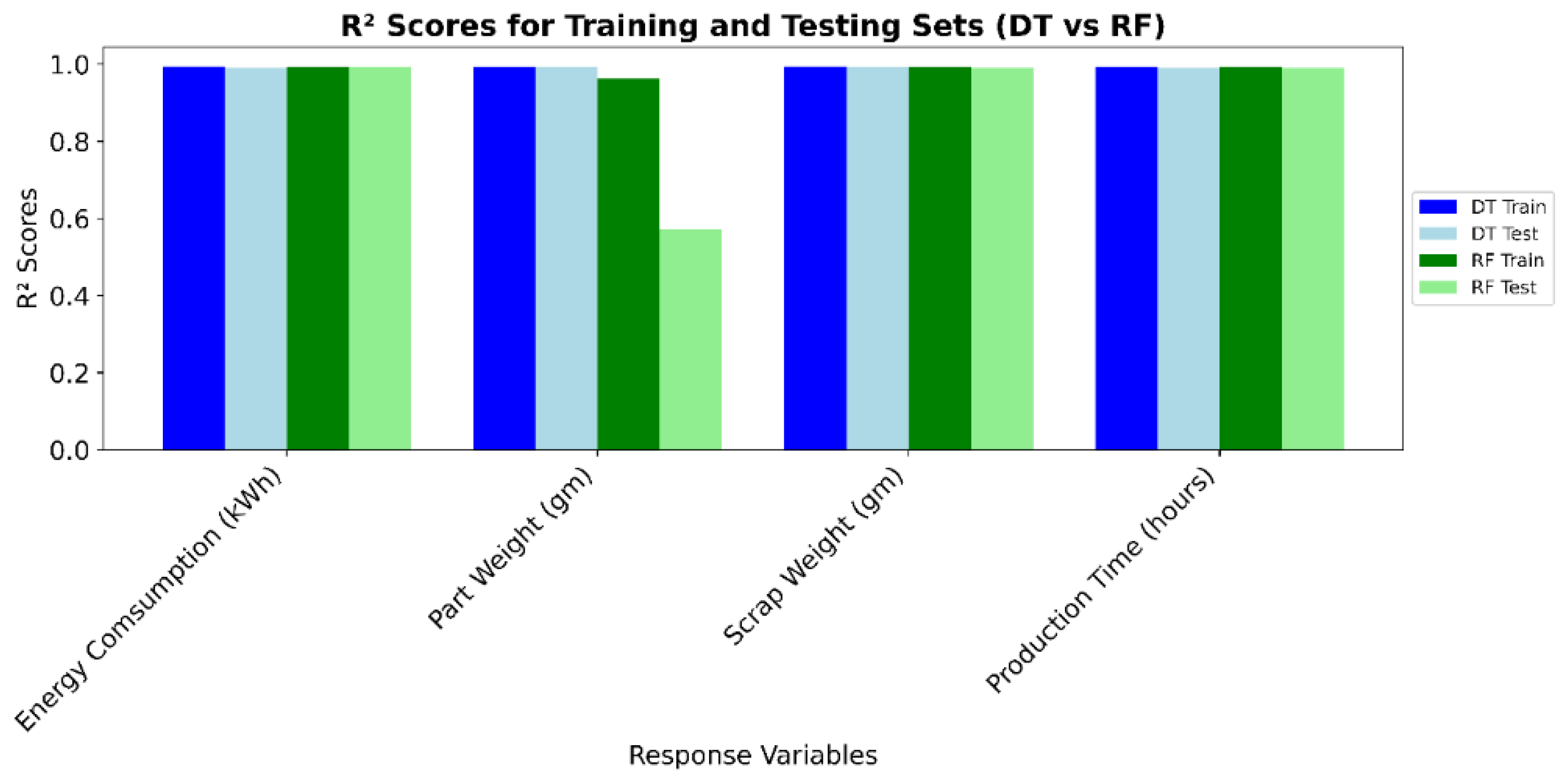

4.1. ML Models Evaluation

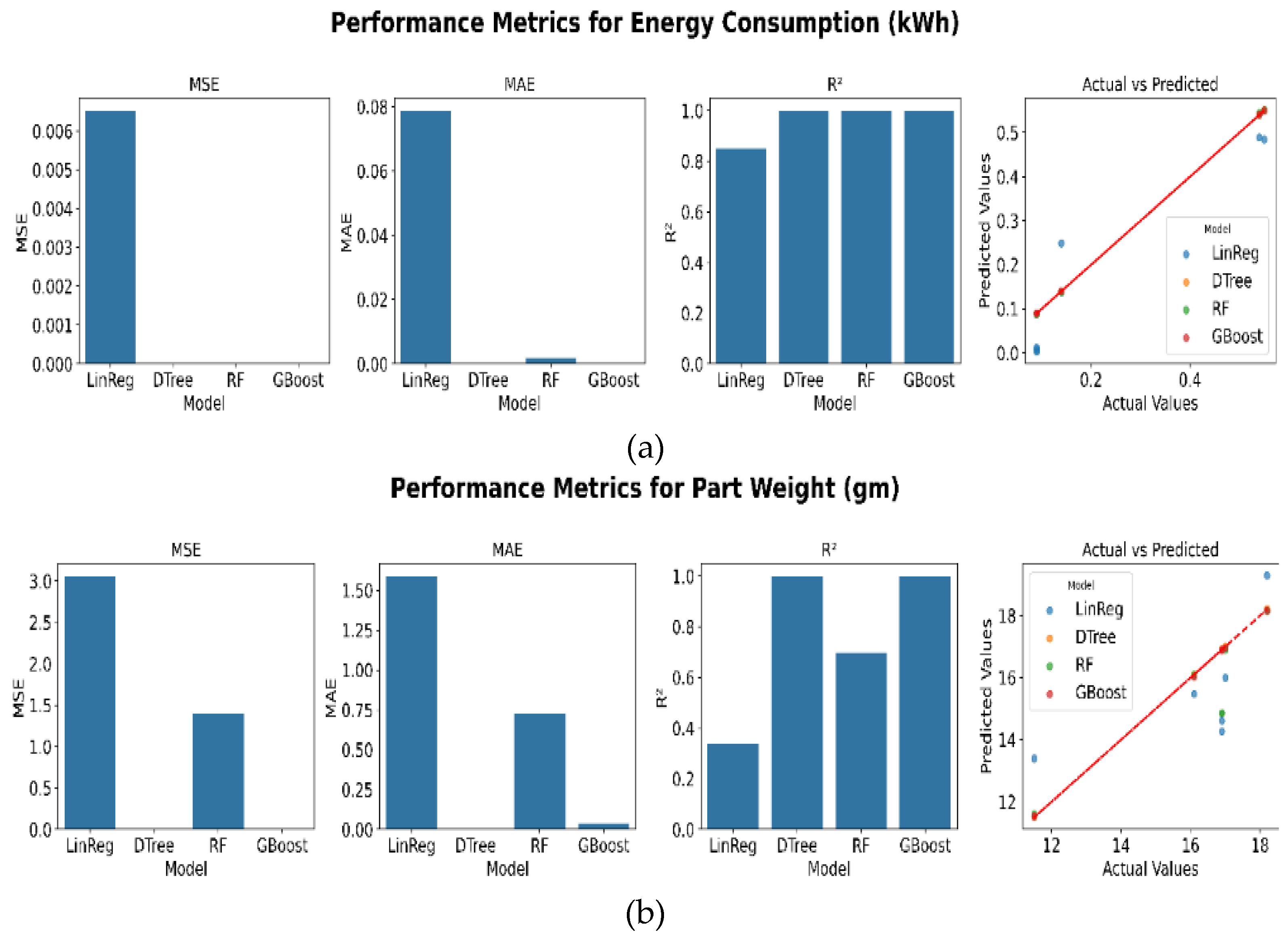

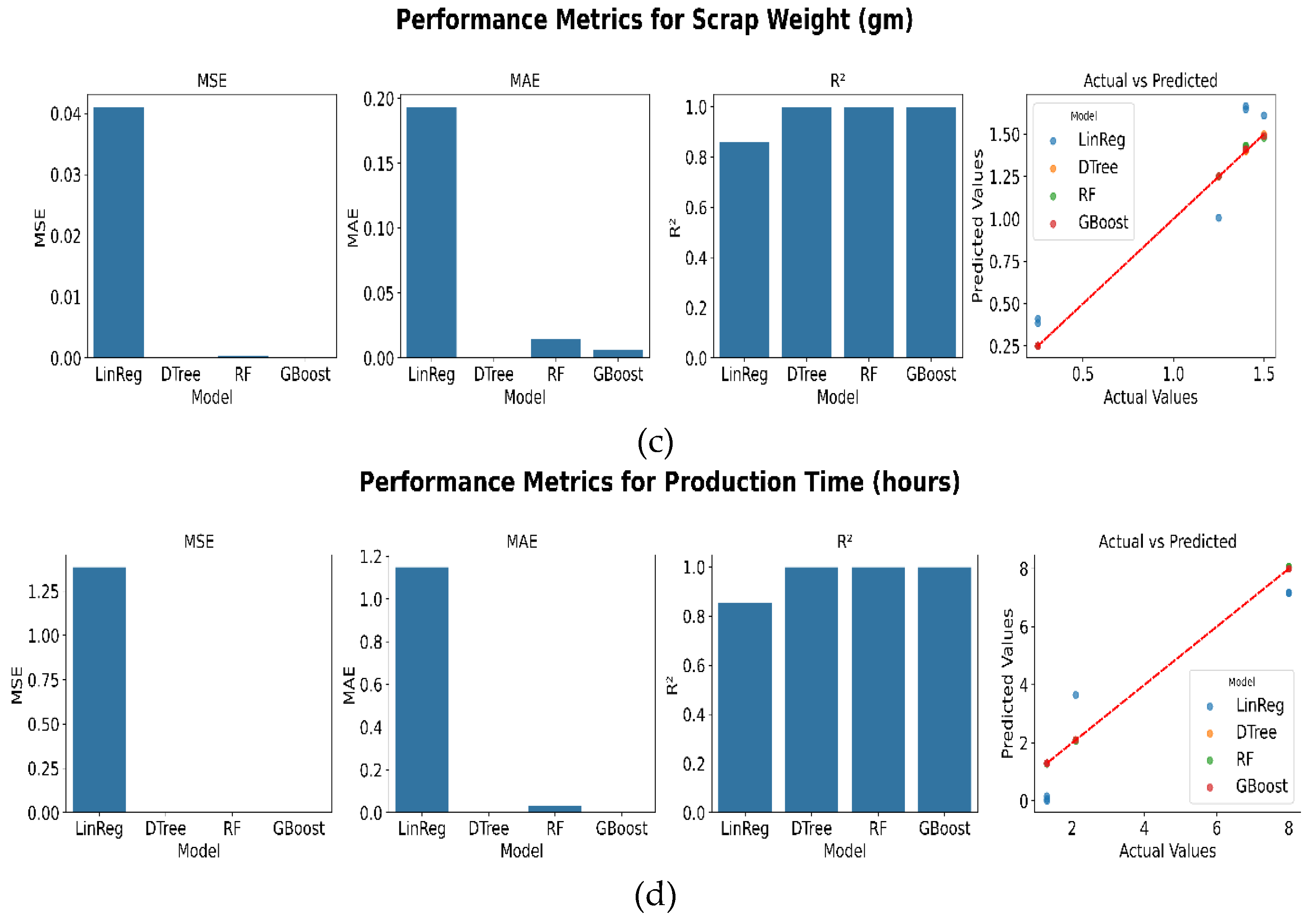

4.1.1. Performance Evaluation

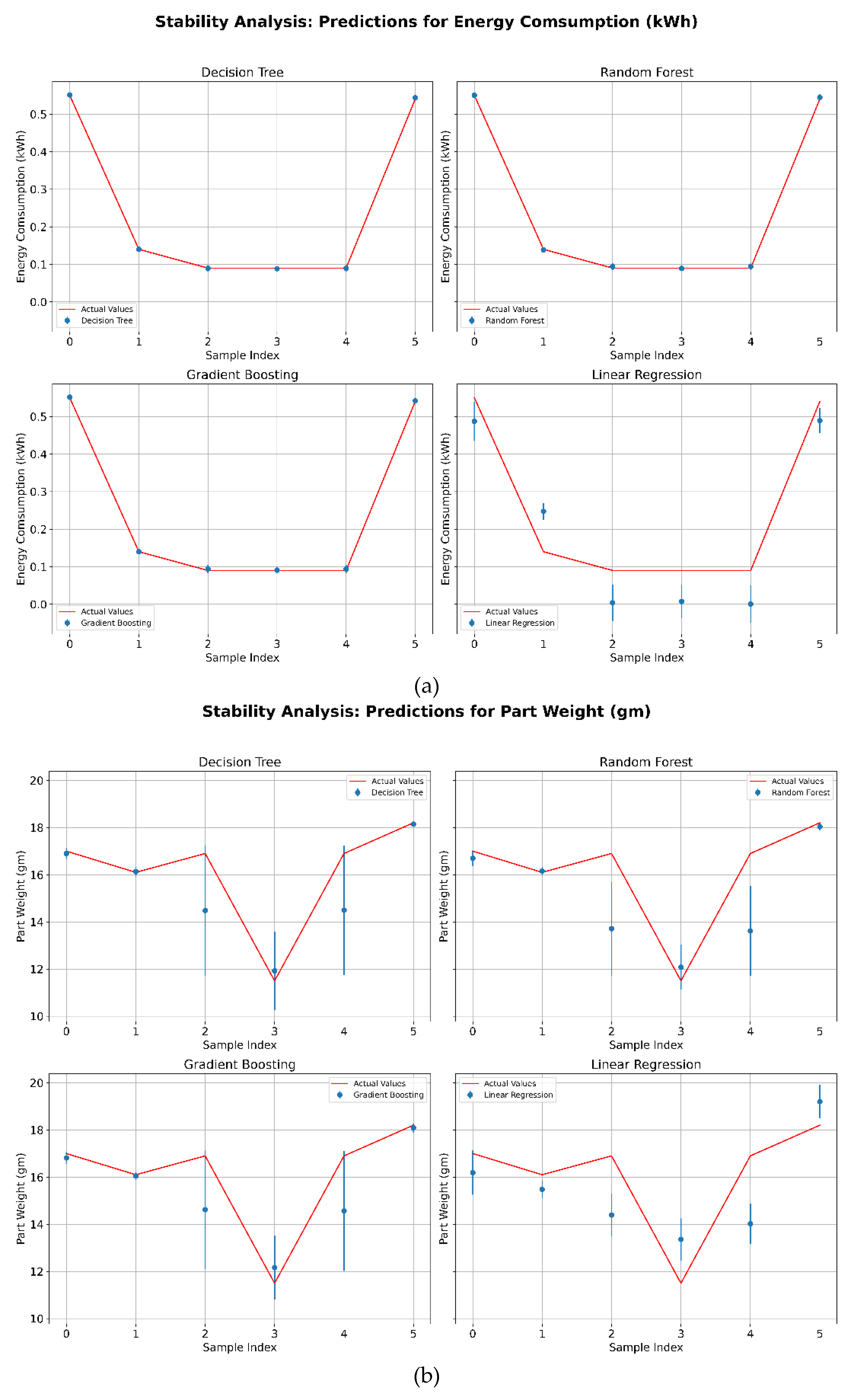

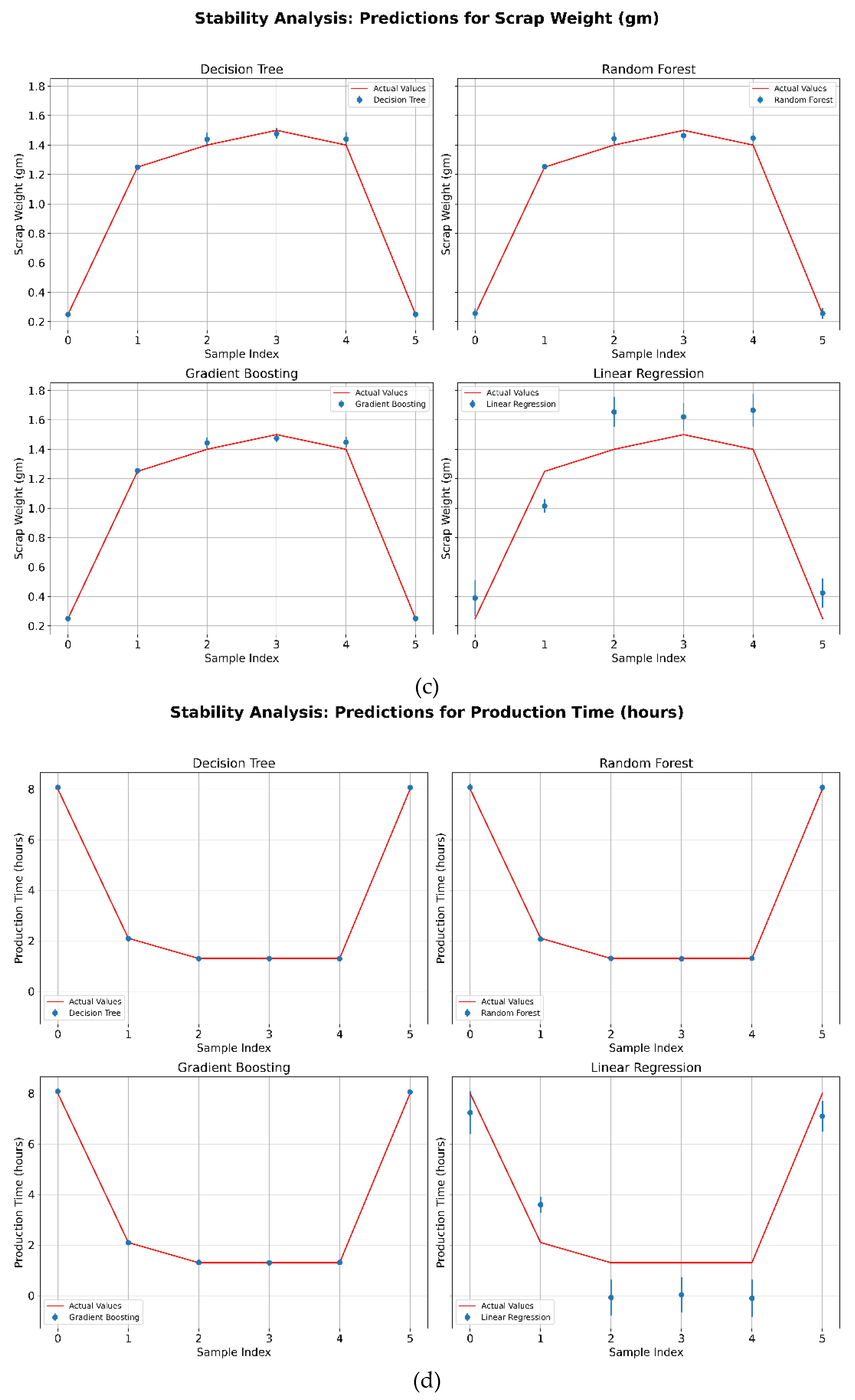

4.1.2. Model Stability Analysis

4.1.3. Model Selection and Parameter Optimization

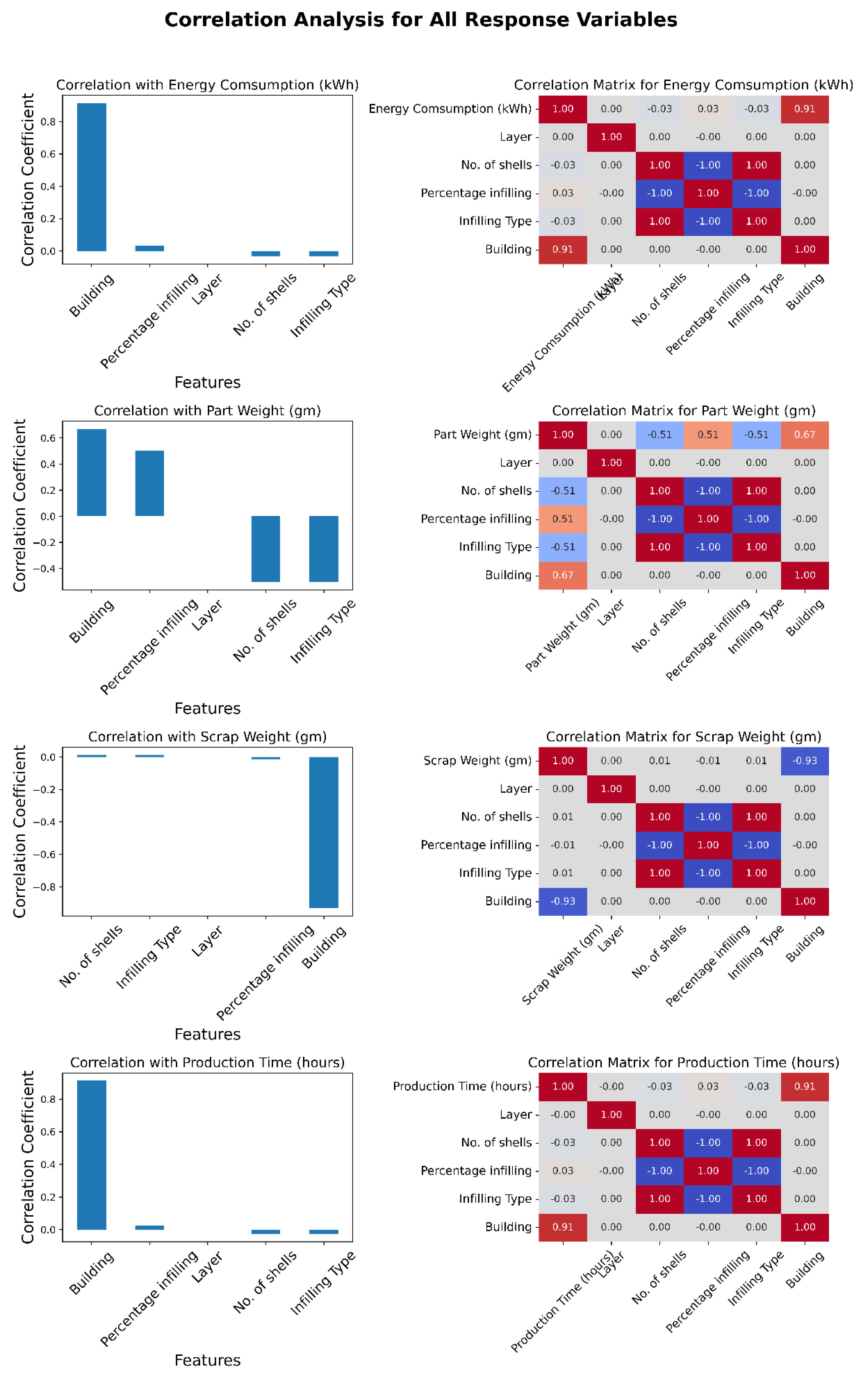

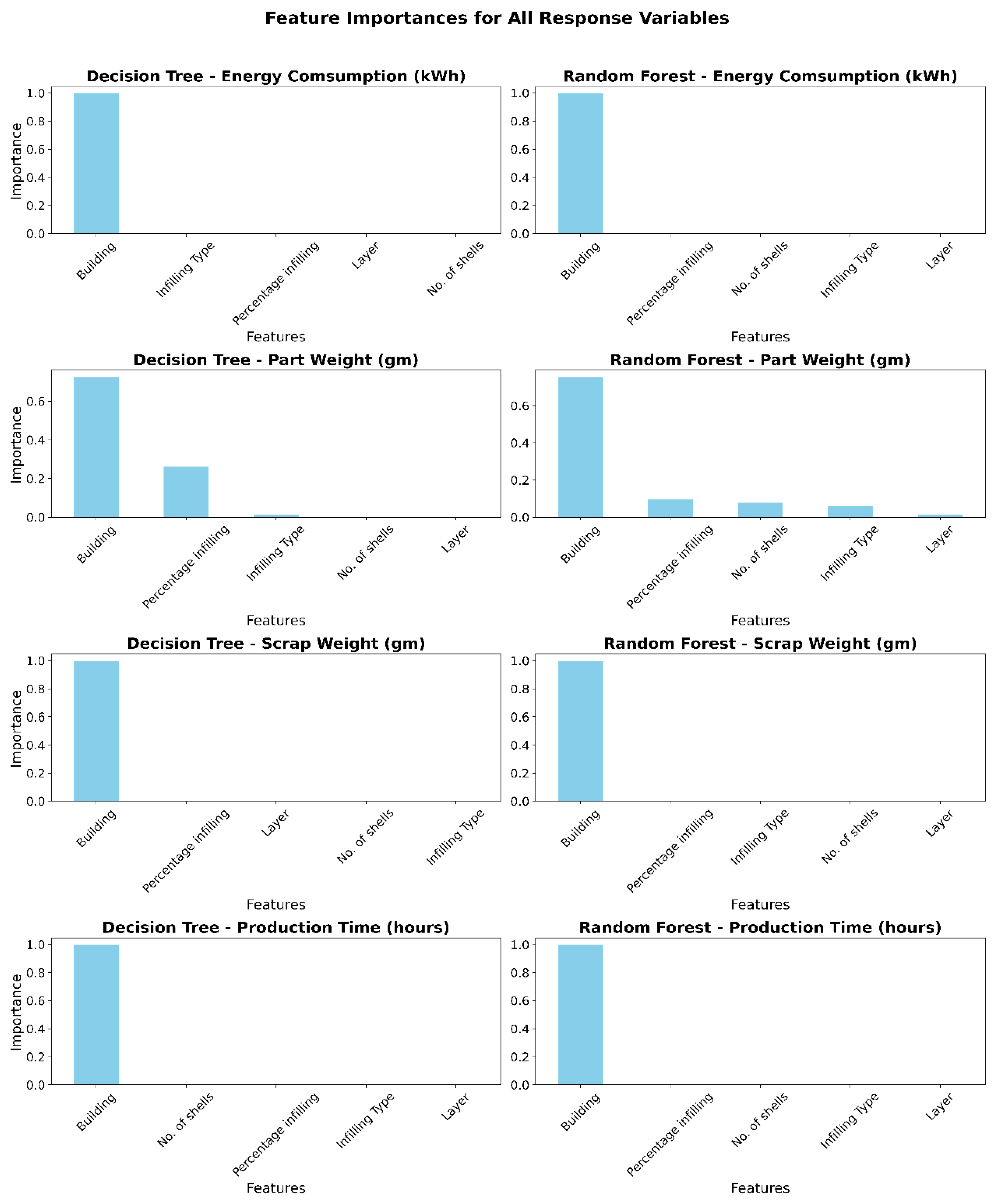

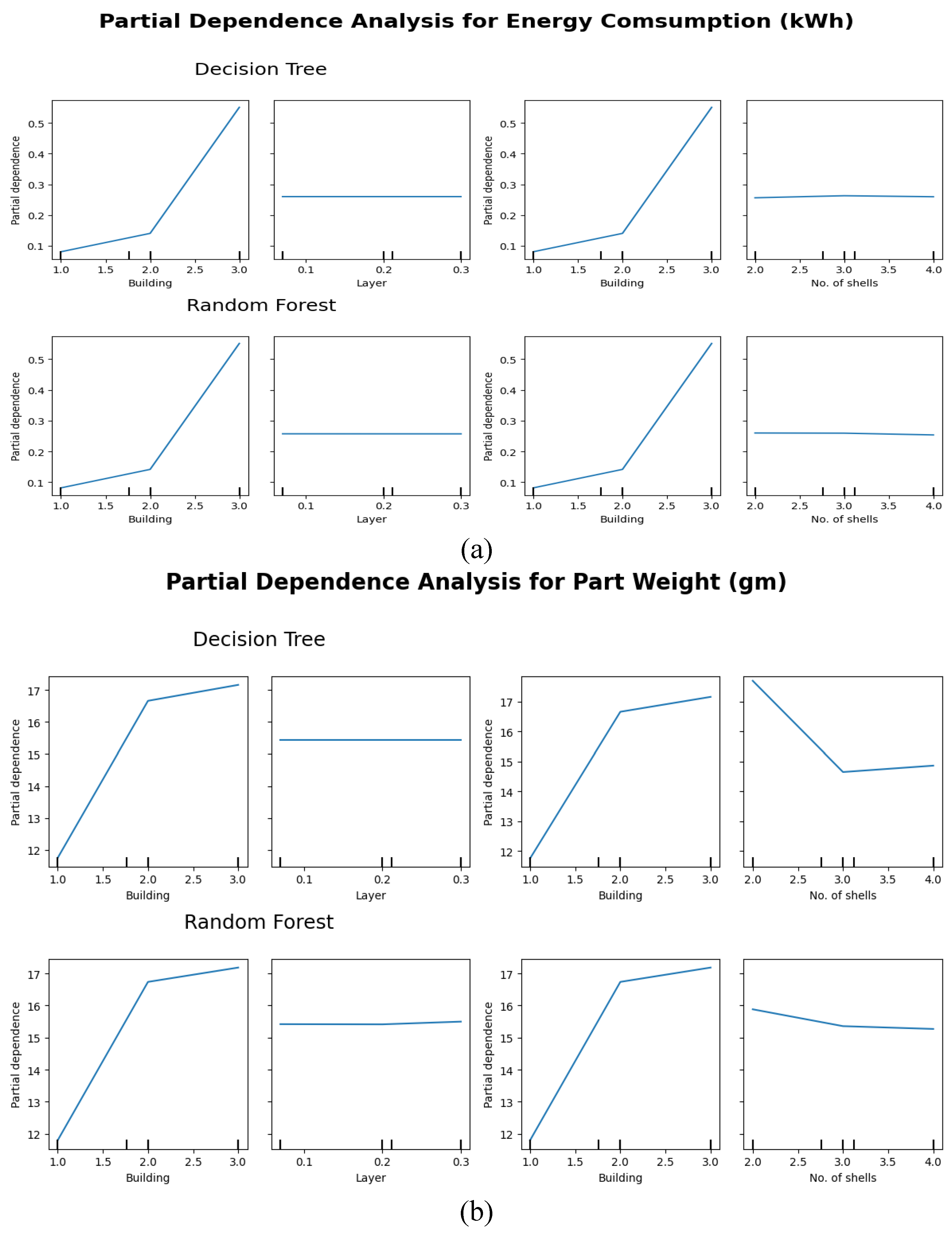

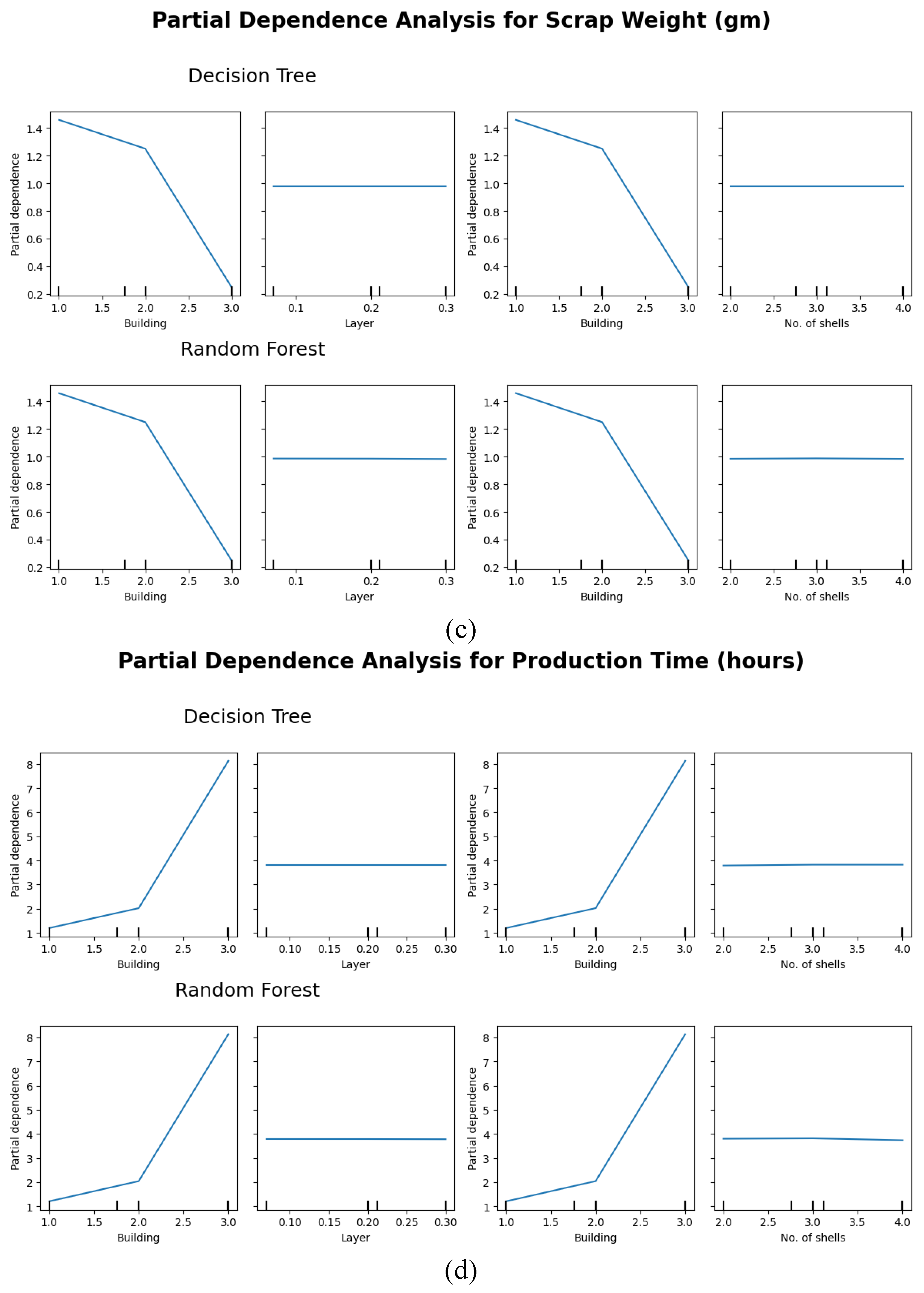

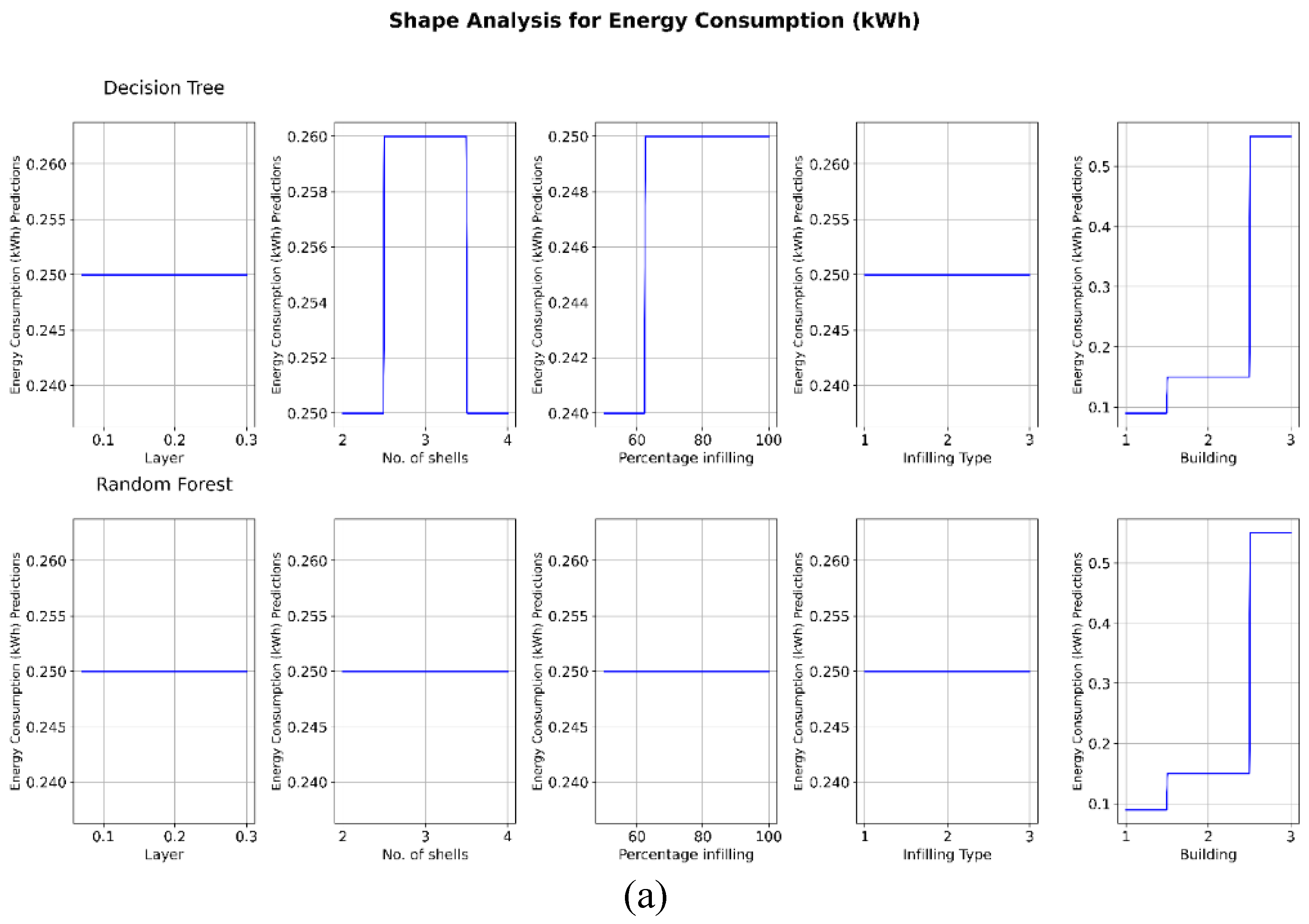

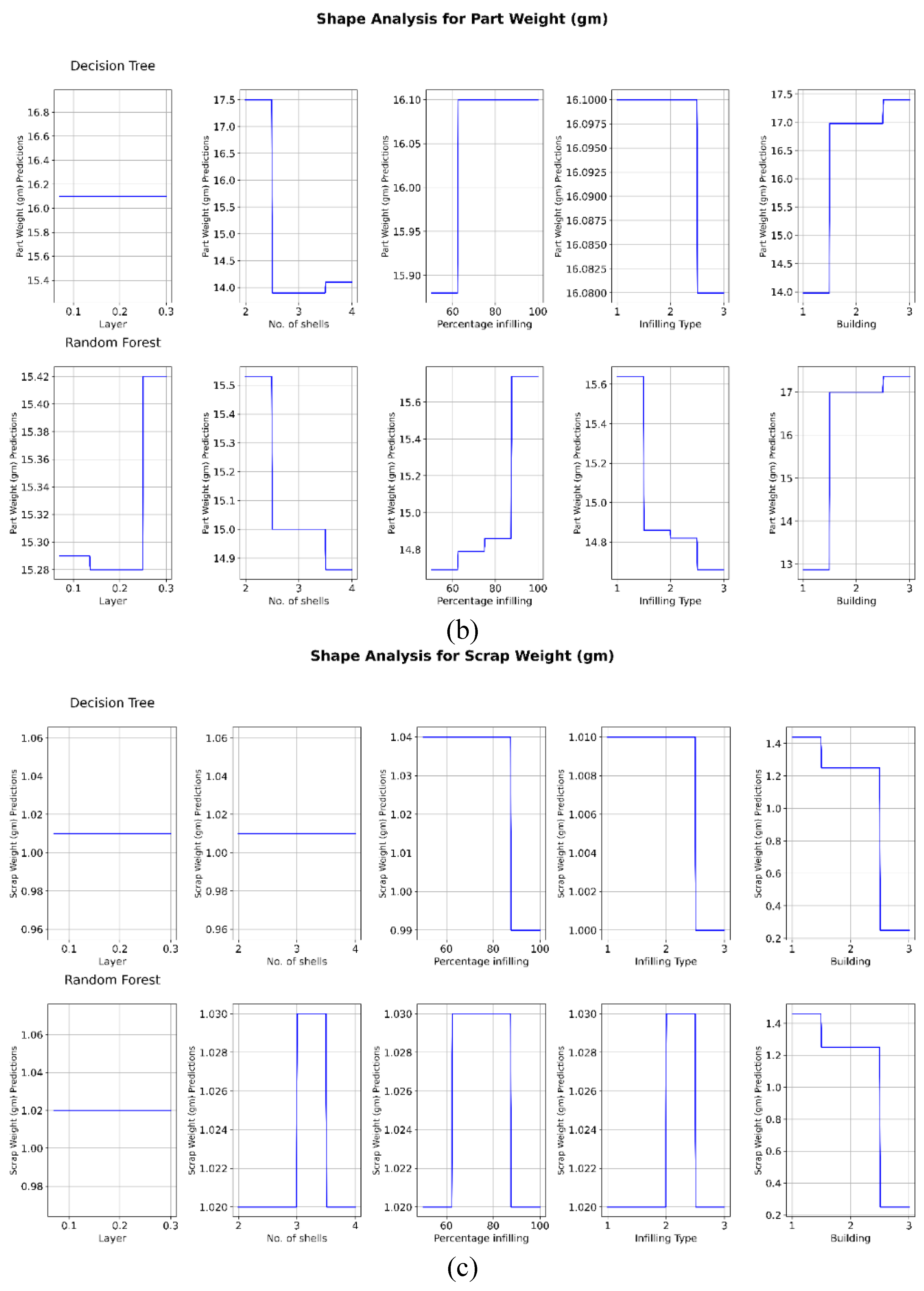

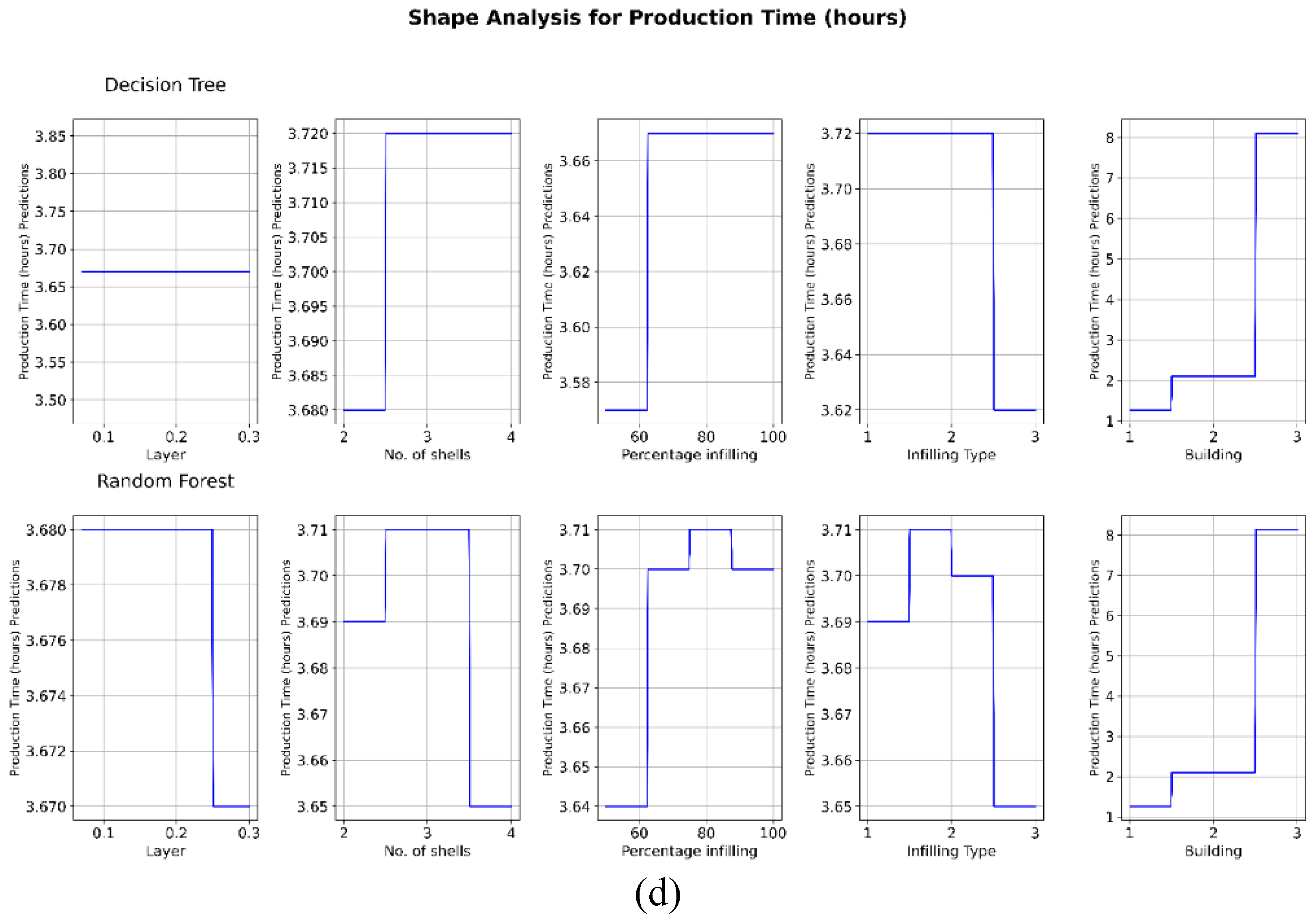

4.2. Relationship Analysis between Process Parameters and Response Variables

5. Conclusions

Abbreviations

| AM FDM CM |

Additive Manufacturing Fused Deposition Modelling Conventional Manufacturing |

| LCA LCC ML LinReg DT RF GB R² MAE MSE |

Life Cycle Assessment Life Cycle Cost Machine Learning Linear Regression Decision Tree Random Forest Gradient Boosting Coefficient of Determination Mean Absolute Error Mean Squared Error |

References

- Panagiotopoulou, V.C.; Stavropoulos, P.; Chryssolouris, G. A Critical Review on the Environmental Impact of Manufacturing: A Holistic Perspective. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2022, 118, 603–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, H.H.; Tregambi, C.; Bareschino, P.; Pepe, F. Environmental and Economic Sustainability of Additive Manufacturing: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustain Prod Consum 2024, 51, 628–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekanye, S.A.; Mahamood, R.M.; Akinlabi, E.T.; Owolabi, M.G. Additive Manufacturing: The Future of Manufacturing. Materiali in Tehnologije 2017, 51, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, A.; Bose, S. ADDITIVE MANUFACTURING; Second edition.; CRC PRESS: BOCA RATON, 2019; ISBN 1-5231-3442-9. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.; Davim, J.P. Additive Manufacturing: Applications and Innovations; Manufacturing Design and Technology; First edition.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2018; ISBN 1-351-68666-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo-Carvajal, D.; Munoz, A.H.; Garrido-Gonzalez, J.J.; Carrasco-Gallego, R.; Montero, V.A. Recycled PLA for 3D Printing: A Comparison of Recycled PLA Filaments from Waste of Different Origins after Repeated Cycles of Extrusion. Polymers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development (a/42/427); 1987.

- Meng, L.; McWilliams, B.; Jarosinski, W.; Park, H.-Y.; Jung, Y.-G.; Lee, J.; Zhang, J. Machine Learning in Additive Manufacturing: A Review. JOM 2020, 72, 2363–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehbaz, W.; Peng, Q. Selection and Optimization of Additive Manufacturing Process Parameters Using Machine Learning: A Review; 2024.

- Swetha, R.; Siva Rama Krishna, L.; Hari Sai Kiran, B.; Ravinder Reddy, P.; Venkatesh, S. Comparative Study on Life Cycle Assessment of Components Produced by Additive and Conventional Manufacturing Process. Mater Today Proc 2022, 62, 4332–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Výtisk, J.; Honus, S.; Kočí, V.; Pagáč, M.; Hajnyš, J.; Vujanovic, M.; Vrtek, M. Comparative Study by Life Cycle Assessment of an Air Ejector and Orifice Plate for Experimental Measuring Stand Manufactured by Conventional Manufacturing and Additive Manufacturing. Sustainable Materials and Technologies 2022, 32, e00431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solaimani, S.; Parandian, A.; Nabiollahi, N. A Holistic View on Sustainability in Additive and Subtractive Manufacturing: A Comparative Empirical Study of Eyewear Production Systems. Sustainability 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokare, S.; Oliveira, J.P.; Godina, R. A LCA and LCC Analysis of Pure Subtractive Manufacturing, Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing, and Selective Laser Melting Approaches. J Manuf Process 2023, 101, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.; Peng, Q. Investigation of Printing Parameters of Additive Manufacturing Process for Sustainability Using Design of Experiments. JOURNAL OF MECHANICAL DESIGN 2021, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, P.; Zagórski, K. Cost, Resources, and Energy Efficiency of Additive Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the E3S WEB CONF; E D P Sciences: CEDEX A, 2017; Vol. 14, p. 1040. [Google Scholar]

- Rejeski, D.; Zhao, F.; Huang, Y. Research Needs and Recommendations on Environmental Implications of Additive Manufacturing. Addit Manuf 2018, 19, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, T.R.; Lee, W.J.; Spurgeon, B.E.; Boor, B.E.; Zhao, F. An Experimental Study on the Energy Consumption and Emission Profile of Fused Deposition Modeling Process. Procedia Manuf 2018, 26, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Li, C.; Fang, X.Y.; Guo, Y.B. Energy Consumption in Additive Manufacturing of Metal Parts. Procedia Manuf 2018, 26, 834–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, H.P.N.; Haapala, K.R. Environmental Performance Evaluation of Direct Metal Laser Sintering through Exergy Analysis. Procedia Manuf 2017, 10, 957–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneevogt, H.; Stelzner, K.; Yilmaz, B.; Abali, B.E.; Klunker, A.; Völlmecke, C. Sustainability in Additive Manufacturing: Exploring the Mechanical Potential of Recycled PET Filaments. Composites and Advanced Materials 2021, 30, 26349833211000064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Mak, K.; Zhao, Y.F. A Framework to Reduce Product Environmental Impact through Design Optimization for Additive Manufacturing. J Clean Prod 2016, 137, 1560–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, T.; Filho, M.; Ganga, G.; Callefi, M.H. The Relationship between Additive Manufacturing and Circular Economy: A Sistematic Review. Independent Journal of Management & Production 2020, 11, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huu, P.N.; Van, D.P.; Xuan, T.H.; Ilani, M.A.; Trong, L.N.; Thanh, H.H.; Chi, T.N. Review: Enhancing Additive Digital Manufacturing with Supervised Classification Machine Learning Algorithms. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2024, 133, 1027–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrin, T.; Pourkamali-Anaraki, F.; Peterson, A.M. Application of Machine Learning in Polymer Additive Manufacturing: A Review. JOURNAL OF POLYMER SCIENCE 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Jatti, V.S.; Sefene, E.M.; Jatti, A. V; Sisay, A.D.; Khedkar, N.K.; Salunkhe, S.; Pagac, M.; Nasr, E.S.A. Machine Learning-Assisted Pattern Recognition Algorithms for Estimating Ultimate Tensile Strength in Fused Deposition Modelled Polylactic Acid Specimens. MATERIALS TECHNOLOGY 2024, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziadia, A.; Mohamed, H.; Kelouwani, S. Machine Learning Study of the Effect of Process Parameters on Tensile Strength of FFF PLA and PLA-CF. Eng 2023, 4, 2741–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, E.; Bagherifard, S.; Guagliano, M. Application of Artificial Intelligence to Optimize the Process Parameters Effects on Tensile Properties of Ti-6Al-4V Fabricated by Laser Powder-Bed Fusion. International Journal of Mechanics and Materials in Design 2022, 18, 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigilipalli, B.K.; Veeramani, A. A Machine Learning Approach for the Prediction of Tensile Deformation Behavior in Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing. IJIDEM 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ege, D.; Sertturk, S.; Acarkan, B.; Ademoglu, A. Machine Learning Models to Predict the Relationship between Printing Parameters and Tensile Strength of 3D Poly (Lactic Acid) Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering Applications Machine Learning Models to Predict the Relationship between Printing Parameters and Tensile Strength of 3D Poly (Lactic Acid) Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering Applications. Biomed Phys Eng Express 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Singh, J.; Gupta, V. Predicting the Compressive Strength of Additively Manufactured PLA-Based Orthopedic Bone Screws: A Machine Learning Framework. Polym Compos 2022, 43, 5663–5674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Shi, J.; Yu, T.; Santomauro, A.; Gordon, A.; Gou, J.; Wu, D. Predicting Flexural Strength of Additively Manufactured Continuous Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites Using Machine Learning. J Comput Inf Sci Eng 2020, 20, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, Y. Neural Optimization Machine: A Neural Network Approach for Optimization; 2022.

- Chen, J.; Liu, Y.M. Neural Optimization Machine: A Neural Network Approach for Optimization and Its Application in Additive Manufacturing with Physics-Guided Learning. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A-Mathematical Physical and Engineering Sciences 2023, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharate, N.; Anerao, P.; Kulkarni, A.; Abdullah, M. Explainable AI Techniques for Comprehensive Analysis of the Relationship between Process Parameters and Material Properties in FDM-Based 3D-Printed Biocomposites. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.-K.; Chen, R.-S.; Tsai, M.-C.; Lee, R.-M.; Lin, C.-C.; Huang, J.-C.; Chang, T.-W.; Horng, M.-H. Machine Learning Applied to Property Prediction of Metal Additive Manufacturing Products with Textural Features Extraction. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2024, 132, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawardane, H.; Davies, I.J.; Gamage, J.R.; John, M.; Biswas, W.K. Sustainability Perspectives – a Review of Additive and Subtractive Manufacturing. Sustainable Manufacturing and Service Economics 2023, 2, 100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, M.; Lyons, K.W.; Gupta, S.K. Sustainability Characterization for Additive Manufacturing. J Res Natl Inst Stand Technol 2014, 119, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, S.; Despeisse, M. Additive Manufacturing and Sustainability: An Exploratory Study of the Advantages and Challenges. J Clean Prod 2016, 137, 1573–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, P.; Zamani, M.; Mostafaei, A. Machine Learning Prediction of Mechanical Properties in Metal Additive Manufacturing. Addit Manuf 2024, 91, 104320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Hyperparameters |

| Decision Tree | Random-state=42 |

| Random Forest | n-estimators=100, random-state=42 |

| Train-Test-Split | Test-size=0.2, random-state=42 |

| minimize (L-BFGS-B) | method='L-BFGS-B' |

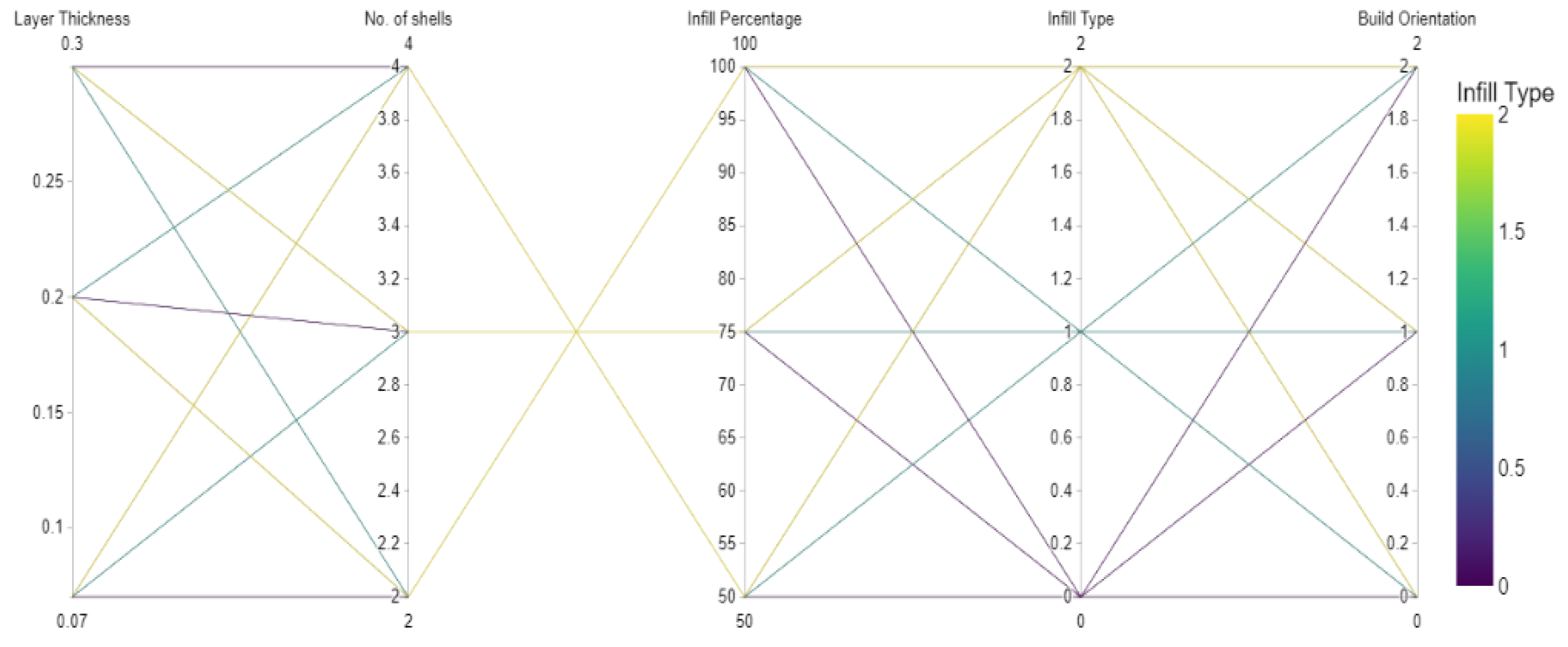

| Process Parameters | Levels | ||

| Layer thickness | 0.07 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Number of shells | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Infill percentage | 50 | 75 | 100 |

| Infill type | Cross | Diamond | Honeycomb |

| Build orientation | Flat | On-edge | Up right |

| Model | Layer | No. of Shells | Infill % | Infill Type |

Build Orientation |

EC (kWh) | PW (gm) | SW (gm) | PT (hours) | |

| DT | 0.2 | 3 | 75 | Diamond | On-edge | 0.140 | 16.10 | 1.2 | 2.1 | |

| RF | 0.2 | 3 | 75 | Diamond | On-edge | 0.139 | 16.09 | 1.2 | 2 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).