1. Introduction

The domain of drug delivery systems has garnered considerable interest in recent years, propelled by the demand for more efficient and tailored therapeutic approaches. These delivery devices function as nanocarriers, swiftly carrying medication to the targeted area while preventing its quick elimination or degradation. Drug delivery systems face challenges, including inadequate solubility, diminished bioactivity, and suboptimal targeting [

1,

2,

3]. Numerous inorganic (e.g., iron oxide nanoparticles, noble metal nanoparticles, quantum dots) and organic (e.g., liposomes, polymers, dendrimers) nanomaterials have been engineered as nanocarriers, each possessing distinct advantages and disadvantages [

4,

5,

6]. Among numerous advanced materials, metal/covalent-organic frameworks (MOFs/COFs) and organic small molecular photosensitizers (PS), such as indocyanine green (ICG), porphyrins, phthalocyanines (Pcs), BODIPY, and other dyes, including hybrid composites have emerged as promising candidates for improving drug delivery mechanisms [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

MOFs and COFs are customizable and adjustable functional crystalline porous materials investigated for applications including catalysis, chemical sensing, water harvesting, gas storage, and separation [

16,

17,

18,

19]. COFs create two- or three-dimensional structures by interacting with organic precursors, forming covalent bonds, and yielding porous organic materials. MOFs/COFs and PS possess unique characteristics for drug delivery. MOFs, also referred to as porous coordination polymers (PCPs), are crystalline coordination polymers. Due to the highly organized porosity and tunable properties of MOFs, they serve as an exceptional substrate for encapsulating various medicinal agents [

20,

21,

22,

23]. Their inherent characteristics, such as extensive surface area, enhanced stability, and ability to interact with diverse organic linkers, facilitate controlled drug release and improved bioavailability. They offer several benefits compared to traditional nanocarriers. (i) They can be engineered to create specific structures with varying shapes, sizes, and chemical characteristics, facilitating the incorporation of diverse therapeutic agents with distinct functionalities; (ii) their extensive surface area, significant porosity, consistent pore size, and volume contribute to elevated loading efficiency and selective transport; (iii) Biodegradable owing to unstable metal and ligand coordination bonds; (iv) Surface functionalization can improve colloidal stability and prolong the blood circulation time [

24,

25,

26,

27].

Numerous hybrid MOFs and COFs exhibit exceptional features, and the deficiencies of individual MOFs/COFs can be mitigated by creating hybrid MOF/COF delivery systems. In recent years, investigations have been conducted on the transport of various biomolecules using COF and MOF nanocarriers, as mentioned earlier. Anticancer agents such as doxorubicin [

28,

29], topotecan [

30], and 5-fluorouracil [

31,

32], to mention a few have been delivered intracellularly via MOFs. PS-functionalized MOFs/COFs have been applied as anticancer agents for photodynamic treatment (PDT) [

33,

34,

35].

PS are agents that absorb light at a specific wavelength and transform it into usable energy. Due to their exceptional photophysical and electrochemical capabilities, PS derivatives are acknowledged for their photophysical characteristics and versatility in various applications, including catalysis, biosensing, gas storage, solar cells, and biomedical uses [

36,

37,

38]. However, their biological applicability, particularly in cancer therapy and detection, is significantly constrained by inherent limitations, including self-quenching, weak absorption in the biological spectrum window, and inadequate chemical and optical stability.

In the past two decades, numerous natural and synthetic dyes, such as PS, have been examined in vitro and in vivo in PDT research. When combined with MOFs/COFs, PS can enhance the therapeutic efficacy of drug delivery systems through methods such as PDT, which utilizes light to initiate drug release or augment absorption by targeted cells. Efforts have been undertaken to associate existing molecular PS with MOFs to address the aggregation problem for biological applications [

33,

39]. Incorporating these two elements into composites facilitates the development of multifunctional platforms capable of addressing the constraints of conventional drug delivery, including low solubility, rapid metabolism, and nonspecific targeting [

40,

41,

42]. Administering these biologically significant molecules as biomolecular therapeutics presents a novel approach to disease treatment.

This succinct review article provides an overview of the various synthetic methodologies used to improve the design of MOFs, COFs, and PS hybrid composites for drug delivery purposes. We will thoroughly examine PS-based MOF/COF targeting techniques used in tumour-targeted therapy in recent years, along with an analysis of potential synergistic effects in medicinal applications. This work seeks to serve as a significant reference and source of concepts for targeted therapy utilizing PS-based MOF/COF materials while also encouraging further investigation of their potential for cancer treatment.

2. Synthesis and Methods

Metal ions or clusters self-assemble with organic ligands to produce repeating building blocks, the process by which photo-responsive MOFs are synthesized. A variety of factors influence their properties during the synthesis process. These elements generally encompass the photoelectronic properties of the metal ions and organic ligands, the solvent employed, the crystal formation speed, the process's length and temperature, and the crystal formation [

43,

44]. Researchers have devised various conventional synthesis methods for MOFs, including hydro-solve-thermal, sonochemical, microwave, mechanochemical, and electrochemical methods. The hydro-solve-thermal method is highly favoured for synthesising photo-responsive MOFs due to its cost-effectiveness, simplicity, and convenience [

43,

45]. In the same vein, there are numerous methods for synthesizing COFs. Conventional COF techniques include microwave [

46], solvothermal [

47], ionothermal [

48], mechanochemical [

49], and vapor phase-assisted [

50]. Assessing these factors and determining the most appropriate approach for the desired results is crucial. The precise selection of a method should be determined by the characteristics of the monomers and the necessary bonding conditions. Ultimately, the ideal MOF/COF synthesis method is determined by the specific requirements of the synthesis, including the desirable structure, scalability, reaction time, impurity removal, pressure, temperature, solvent selection, and potential for industrial production.

2.1. MOF Drug Incorporation Delivery Pathways

Drug loading tactics for MOFs have the distinguishing characteristics of having a large surface area and structural divergence, which make it easier to load drugs on the exterior or inside the pores using a variety of loading strategies. The one-step strategy and the two-step method are two forms of drug-loading strategies that are utilized frequently [

51].

2.1.1. One-Step Synthesis

This technique directly incorporates medicinal agents with the MOF during their synthesis. This technique employs uniform distribution and substantial drug-loading capability. Nonetheless, regulating particle size, shape, and physicochemical properties of existing MOFs is difficult. Furthermore, it is imperative to implement additional measures to guarantee that medicine remains undamaged during the production process [

52].

The one-pot approach involves the co-precipitation of the medication with the MOF during synthesis. As a result, the pores of MOFs evenly distribute drug molecules. [

52]. The one-step synthesis approach accomplishes the entire synthesis process under a singular reaction state, eliminates the need for separation and purification of intermediate products in multi-step synthesis, streamlines the synthesis pathway, and enhances synthesis efficiency. Zheng et al. [

53] proposed an innovative method integrating MOF production with molecular encapsulation in a single-step procedure. They demonstrated that zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF) crystals can contain substantial medication and dye molecules. The crystals uniformly disperse the molecules and allow for the adjustment of their concentrations. They showed that ZIF-8 crystals filled with the cancer-fighting drug DOX work well as drug delivery systems in cancer treatment because they release the drug when the pH level changes. Their efficacy on breast cancer cell lines surpasses that of free DOX. Their work demonstrates that the one-pot technique creates new opportunities to develop multifunctional delivery systems for many applications.

2.1.1.1. Drugs as Organic Linkers for MOFs

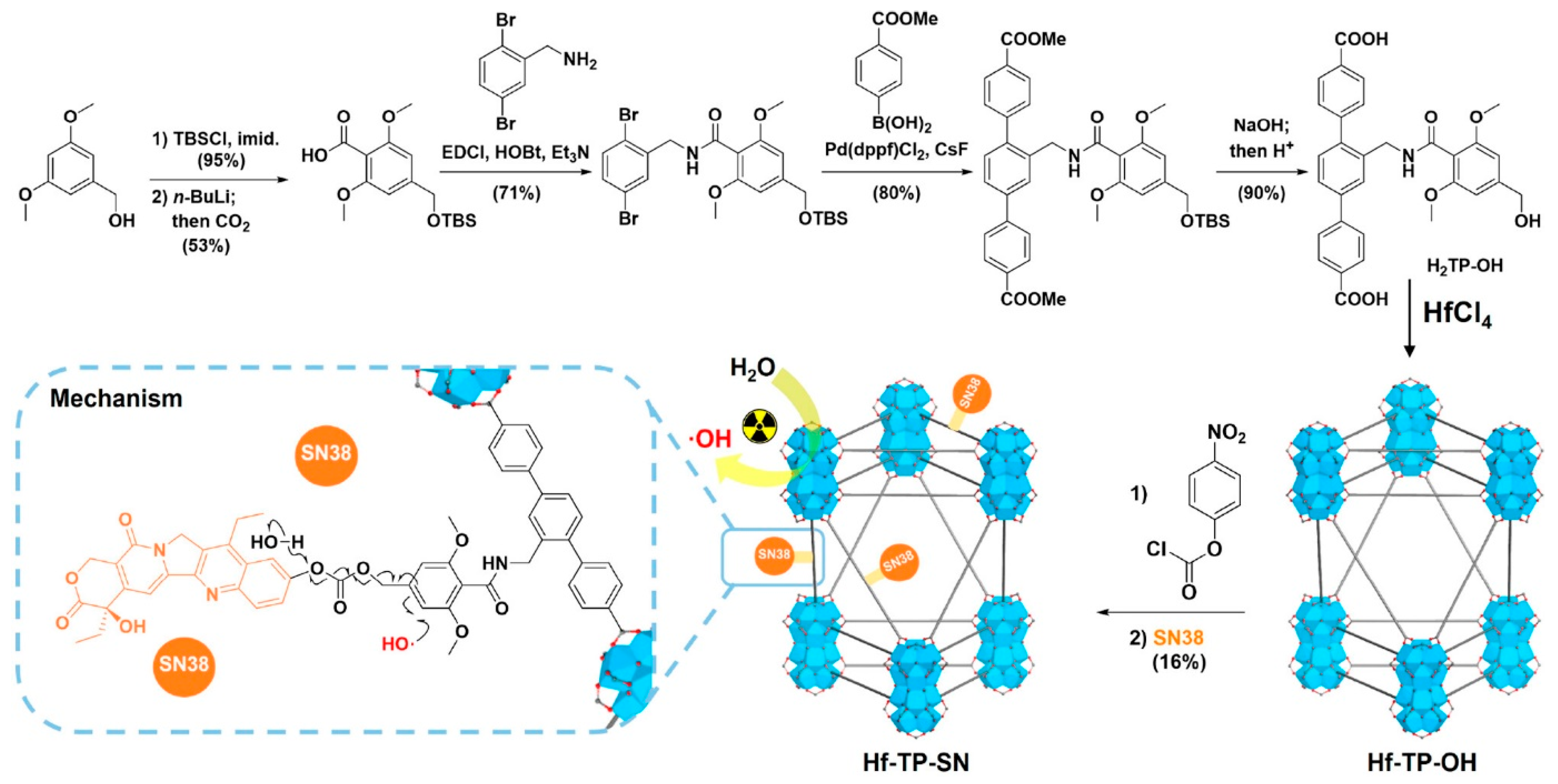

Drugs or their prodrugs may operate as organic ligands to form MOFs and act as MOF reservoirs by coordinating their specific functions with designated metal ions [

2],

Figure 1. Xu, Zhen, and colleagues reported the invention of a new nMOF, Hf-TP-SN, with an X-ray-triggerable 7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin (SN38) prodrug for synergistic radiation and chemotherapy. Upon X-ray irradiation, electron-dense Hf12 secondary building units function as radiosensitisers to augment hydroxyl radical production, facilitating the triggered release of SN38 through the hydroxylation of 3,5-dimethoxylbenzyl carbonate, followed by 1,4-elimination, resulting in a fivefold increase in the release of SN38 from Hf-TP-SN compared to its molecular counterpart. Therefore, using Hf-TP-SN along with radiation causes a lot of cell death in cancer cells and stops tumour growth in colon and breast cancer models in mice.

A study by Truong Hoang Q and colleagues also introduced nanoscale zirconium-based p-MOFs (PCN222) as safe and effective nanosonosensitizers. Polyethylene glycol (PEG)-coated PCN-222 (PEGPCN) was infused with the pro-oxidant agent piperlongumine (PL) to facilitate tumour-targeted chemo-photodynamic combination therapy. PEG-PCN and PL-incorporated PEG-PCN (PL-PEG-PCN) exhibited significant colloidal stability in biological media. Moreover, nanoscale PL-PEG-PCN was effectively internalised by breast cancer cells, resulting in a substantial enhancement of ROS formation with ultrasonic exposure [

54].

2.1.1.2. Co-Crystallization

Laboratory research and industry use co-crystallization to load medicines into MOFs. Minimal reaction conditions can create a 3D supramolecular structure containing the medication. Co-crystallization improves drug solubility and loading without affecting their physicochemical properties. Most importantly, cocrystallization does not alter the drug's physicochemical properties, which can improve solubility and loading. Hao Cheng and coworkers [

55] cocrystallized mannitol with CaCl₂ using slurry and solvent evaporation. They compared tablet performance between cocrystal and -mannitol. The bonding area-bonding strength (BA-BS) model associated tabletability differences with crystal structures. The produced cocrystal has a 1:1:2 molar ratio of mannitol, CaCl₂, and water (i.e., mannitol·CaCl₂·2H₂O). Mannitol molecules link the Ca

2+ in the cocrystal through an endless coordination network, forming a classic MOF structure. Compared to β-mannitol, MOF-based cocrystals showed better tabletability (2 times higher tensile strength) and less tendency to laminate (3 times higher minimum compaction pressure). Due to stronger intermolecular contacts, the cocrystal's greater BS improved tabletability. The lowered lamination propensity was due to lesser in-die elastic recovery than β-mannitol.

2.1.2. Two-Step Synthesis

The two-step synthesis method optimises the reaction conditions at each step to obtain the best reaction results. This phased synthesis strategy is conducive to selecting the appropriate solvent, temperature, and reaction time to improve the synthesis efficiency and product quality. When drugs' molecular dimensions are smaller than MOFs' pore diameter, this technique often predicts their containment within the scaffolds through hydrogen bonding, contacts, or other host-guest interactions. It is anticipated that larger drug molecules with opposing charges will be adsorbed by MOFs via electrostatic interactions [

56,

57].

2.1.2.1. Impregnation

Due to their porous nature and accessibility to metal ions and tiny molecules, MOFs can be impregnated with precursors by diffusion/deposition. The MOF solids are immersed in a precursor-laden solution for impregnation. The adsorbed precursors become the final active species or undergo further reactions (such as reduction, decomposition, or other chemical processes) to form new functional phases in the MOF matrices. Zulys and associates [

58] used solvothermal synthesis to create AgNPs@MOF-808 nanocomposites, which are used for drug delivery. They utilised a zirconium-based MOF with benzene-1,3,5-tricarboxylic acid linkers, also known as MOF-808. MOF-808 (72h) had the highest crystallinity with a nano-MOF particle size of around 77-277 nm. Ag⁺ was incorporated into AgNPs at different AgNO₃ concentrations (0.01, 0.05, 0.2, and 0.4 mmol), utilising MOF-808 as a template and DMF as a mild reductant. AgNPs@MOF808 (0.4) dispersed a maximum of 5 nm nano spherical AgNPs within the pores, accompanied by an octahedral MOF of approximately 130 nm.

2.1.2.2. Covalent Binding

Within the MOF structure framework, covalent bonds are created by utilising organic linkers and inorganic metal clusters during covalent binding. Even though the method can insert a wide variety of cargoes into MOFs, there are frequently issues with the pharmaceuticals slowly leaking due to the relatively weak contact force between the drugs and MOFs [

59]. The potential for the medications to cause leakage creates a problem. In addition, some MOF derivatives can break down and clump together in vivo, while loaded medications are known to experience the burst effect in these settings. X. Liu and associates [

60], developed a simple yet effective bilayer coating method to mitigate these issues as a conventional, dual-phase process component. The bilayer-coated MOF NU-901 also dispersed well in biologically relevant fluids like buffers and cell growth media throughout the study. Adding the coating makes the drug-loaded MOFs more stable in water by stopping drug leakage and MOF particles from sticking together.

2.2. PS-COF-Based Synthesis

Porphyrins are abundant in nature and play important roles in many living creatures, including cytochromes, haemoglobin, and chlorophyll. Metalloporphyrin complexes, known as "life pigments," compose these biological entities and play critical roles in life processes [

61,

62]. The unique properties of their tetrapyrrole macrocycles determine the porphyrins' functional prowess, including biochemical, enzymatic, and photochemical capabilities. As such, most research into synthesising PS-based COFs (PS-COFs) has focused on integrating porphyrins with COFs (p-COFs) for use in biological applications. The preparation of p-COFs is similar to those of other COFs. The construction of p-COFs frequently employs imine, triazine, and borate condensation reactions [

63]. The thermodynamic regulation allows for the reversibility of the ongoing reactions [

64,

65]. Processes can self-correct and self-heal during the production of reversible covalent bonds [

11,

66,

67]. These processes produce ordered and thermodynamically stable p-COFs [

68,

69].

3. Biocompatibility

3.1. MOFs

Metallic compounds employed in biomedical applications are frequently examined for their possible long-term consequences. The elevated reactivity and diminutive size of MOFs raise safety issues about human health. Researchers have conducted limited toxicity studies to evaluate the cytocompatibility of MOFs, which has led to an inadequate characterisation of their toxicity. MOFs may accumulate within cells due to their reduced size. Metal accumulation over time may pose safety risks, particularly if MOFs are employed as long-term medicinal delivery methods [

70,

71]. Therefore, it is essential to do comprehensive in vitro and in vivo toxicity assessments to guarantee biocompatibility. Creating a correlation between in vitro and in vivo research is essential to determine the appropriate dosage within safety parameters.

3.2. COFs

COFs, the metal-free counterparts of MOFs, are freshly created organic polymers that have generated significant enthusiasm among researchers aiming to harness their potential for drug delivery. COFs, created through the covalent bonding of molecules, constitute a new class of porous materials. The crystals of COFs consist only of light atoms, including C, H, O, N, and B [

40], therefore mitigating the potential toxicity linked to the metal ions present in their MOF counterparts. In relation to biocompatibility and biodegradability, both in vitro and in vivo tests yielded remarkable results. Still, the synthesised COFs must be thoroughly tested for toxicological effects, such as long-term systemic toxicity, biosafety, and biodegradation kinetics, in line with FDA rules [

72,

73].

3.3. PS

The optimal biocompatible PS should have high light absorption coefficients, especially for long-wavelength near-infrared radiation, to help them get deeper into tissues; low photobleaching quantum yields; high intersystem crossing efficiencies; low toxicity when light is not present; and, finally, the right balance of hydrophilic and hydrophobic properties to help them stick to tumours [

74,

75,

76]. The predominant alterations to the PS-based complexes encompass incorporating water-soluble moieties, enhancing optical characteristics, attaching targeting entities to facilitate accumulation in neoplastic cells, and extending therapeutic efficacy. Over the past decades, researchers have thoroughly examined various methods for synthesising PS derivatives and altering their photophysical and photobiological characteristics [

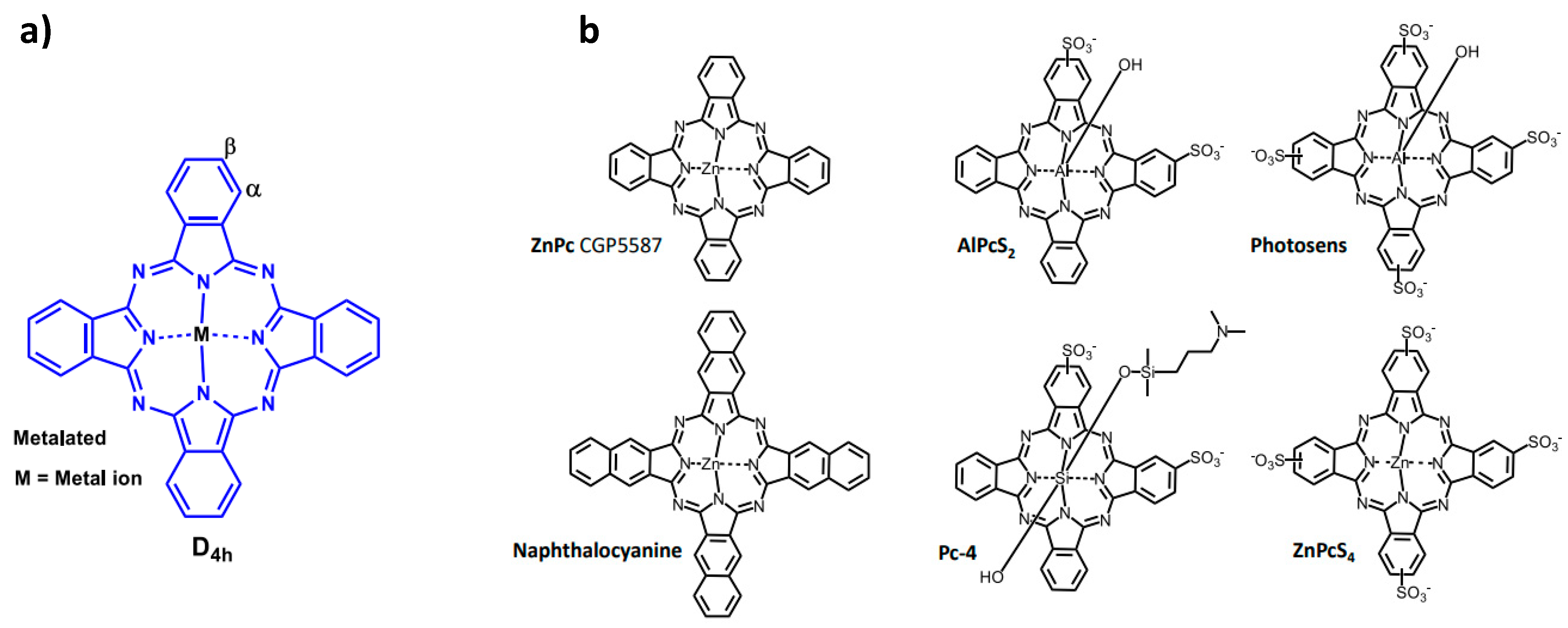

34]. Substitution on the various PS skeleton structures can be performed; for example, the Pc macrocycle can be modified at peripheral and/or non-peripheral positions

Figure 2 a, and depending on the metal centre, substituents can also be incorporated into the axial positions

Figure 2 b (Pc-4). In the field of PDT, there have been documented clinical trials that have utilised Pc-based PS,

Figure 2 b [

77,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83].

The conjugation or integration of PS into nanostructures facilitated their application in nanomedicine. The third generation of PS has a lot of benefits, such as the ability to do more than one thing, like targeting tumour tissues specifically and improving the efficiency and selectivity of intracellular delivery with PS [

7,

34]. In the fourth generation of PS, porous carriers are used; these include COFs and MOFs.

4. Biomedical Applications: Drug Delivery Therapeutics

4.1. Drug Delivery

Drug delivery involves encapsulating or loading therapeutic chemicals, particularly intractable and unstable medicines, into nanocarriers for successful transport to the desired target. This method reduces systemic side effects, extends the half-life of unbound pharmaceuticals, and improves the effectiveness of current medications [

84,

85]. Therefore, it is essential to construct drug delivery carriers with a significant surface area, high drug loading capacity, acceptable biocompatibility, and multifunctional properties. MOFs and COFs are regarded for drug delivery owing to their elevated porosity, ease of synthesis, configurable composition and structure, adjustable size, programmable surface functionality, and biodegradability, as earlier mentioned [

86,

87]. The porous and structured framework, customisable dimensions, and increased surface area ratios effectively load diverse cargos into MOFs, improving cargo capacity and rendering them suitable for biomedical applications [

88,

89].

Their highly porous architectures and multifunctionality facilitate the accommodation of substantial quantities of medicinal and imaging chemicals, enabling regulated release while protecting against enzymatic degradation and self-quenching in biological systems [

84,

85]. Compared with conventional nanomaterials such as inorganic zeolites, mesoporous silica, quantum dots, metal nanoparticles, and organic nanocarriers comprising lipids or polymers, MOFs often exhibit a bigger cargo loading capacity, good biocompatibility, and ease of functionalisation [

90,

91]. Moreover, their gentle synthetic conditions facilitate the development of various MOFs and the integration of a wide array of molecular capabilities on both their internal and external surfaces, encompassing imaging modalities, therapies, and targeting ligands. Many PS-MOF/COF-based composites have also been employed as targeting agents in the NIR in photothermal therapy [

92,

93].

Table 1 summarises a few illustrations of PS-COFs and PS-MOFs reported for the delivery of therapeutic agents.

4.2. Principle of Operation for PDT

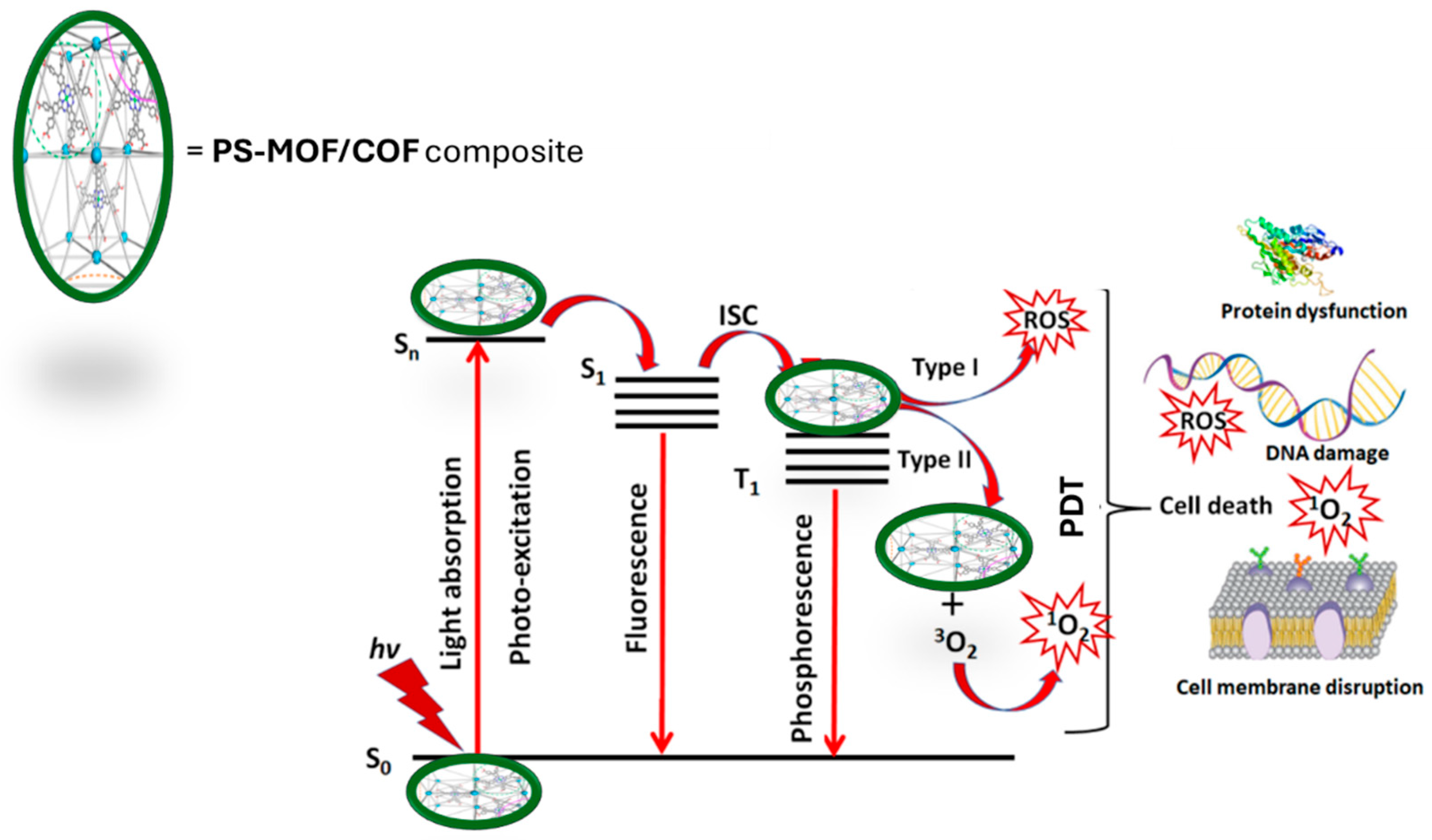

In PDT using photo-responsive PS-MOF/COF composite (

Figure 3), electrons that aren't stable in the S

1 state give off energy as fluorescent quanta. These electrons then move to a more stable excited state (T

1). When the photosensitive PS-MOF/COF is in the T

1 state, it creates cytotoxic ROS through two different types of reactions [

99]. The PS-MOF/COF reacts directly with the cancerous substance in the type I reaction, creating free and anion radicals through electron or hydrogen transfer. This creates ROS, which includes hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2), hydroxyl radicals (

_OH), and superoxide anion radicals (O

2−) [

22,

100]. In type II reactions, the PS-MOF/COF directly transfers its energy from the T

1 state to the fundamental energetic state of O

2. Subsequently, it produces highly reactive

1 O

2 species [

34,

101]. The characteristics of nanoconjugates formed by MOFs/COFs with PS and their influence on PDT effectiveness have been assessed in several research investigations due to their significant significance in PDT as optimal organic PS carriers and delivery agents. The MOF nanoparticles can adsorb the PS molecules onto their surface.

4.2.1. Photodynamic Therapy

In PDT, nontoxic PS localised in tumours is activated by specific light, transferring energy to adjacent O

2 molecules and producing

1O

2. This reduces tumour, vascular damage, localised acute inflammation, and immune response. PS-MOF hybrid complexes have lately garnered attention as potential PS for PDT. The hypoxic conditions commonly present in solid tumours diminish the efficacy of PDT. PS, such as Pcs/porphyrin, can convert molecular O

2 into

1O

2 upon light exposure, enhancing PDT's therapeutic efficacy [

34].

Recent studies have identified nMOFs as a promising element for PDT due to their excellent biocompatibility, biodegradability, suitable dimensions, and capacity for precise functionalisation [

102]. Consequently, employing PS-MOF hybrid complexes PDT can enhance the effective transformation of ambient tissue oxygen into cytotoxic singlet oxygen, elevating cellular temperature [

103]. The effective photothermal conversion results in heightened cell necrosis and apoptosis, rendering hybrid composites based on PS-MOFs proficient oxygen sensors within cells [

103,

104].

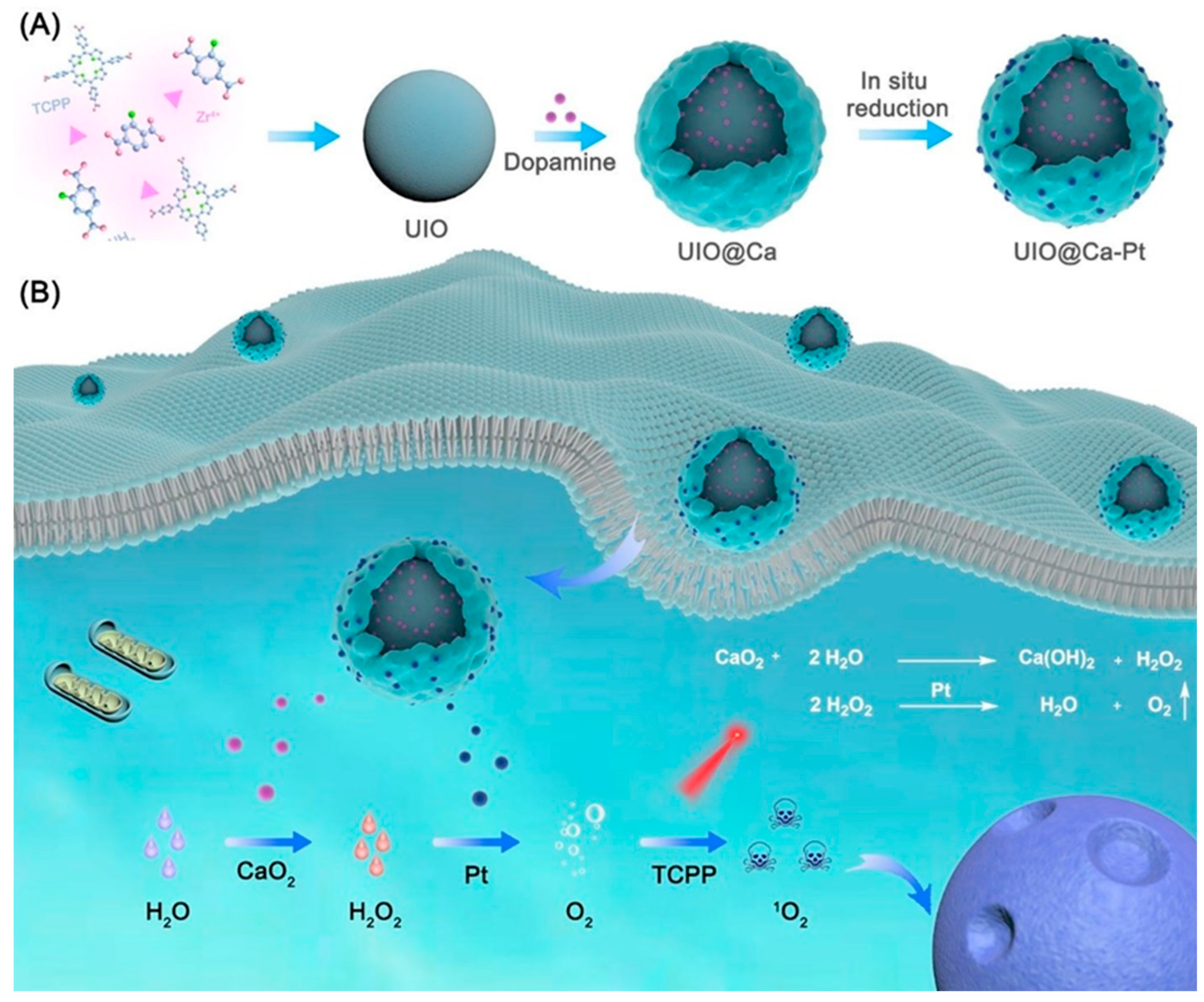

A study examined the design and construction of a multifunctional nano platform for catalytic cascades-enhanced PDT, utilising a combination of p-MOF (UIO) loaded with CaO

2 nanoparticles, polydopamine (PDA) and platinum precursors aimed at mitigating hypoxia and enhancing the efficacy of PDT in cancer treatment [

1],

Figure 4. The research indicated that the UIO@Ca-Pt nano platform could mitigate hypoxia and improve the efficacy of PDT in cancer treatment. The platform can generate oxygen and facilitate the generation of toxic singlet oxygen utilising PS TCPP under laser irradiation.

The study's results indicated that UIO@Ca-Pt nanoparticles generate oxygen and reactive ROS during exposure to laser light, leading to enhanced anticancer effects in vitro and in vivo. The UIO@Ca-Pt nano platform can efficiently generate ROS and oxygen. UIO@Ca-Pt has exceptional stability and biocompatibility. UIO@Ca-Pt can effectively induce cytotoxicity and death in cancer cells. UIO@Ca-Pt demonstrates exceptional therapeutic efficacy in mice with tumours. The findings indicate that the UIO@Ca-Pt nanoparticles exhibited a unique structure, enhanced PDT efficacy, and augmented oxygen-generating capabilities. Moreover, the nanoparticles exhibited much greater anticancer efficacy and reduced haemolytic potential compared to the intermediates and raw materials.

p-MOFs coated with a thin layer of manganese dioxide nanosheets (designated as MMNPs) have been utilised as PS for PDT upon NIR activation. Di Zhang and colleagues [

105] developed an O

2-evolving PDT nanoparticle that addresses the limitations of conventional PDT, including inadequate targeting and diminished therapeutic efficiency resulting from tumour hypoxia. The porphyrin-based MOFs were initially synthesised with a modified microemulsion templating method. The cell membrane serves as the shell for MMNPs, enabling cancer cell targeting capabilities (CM-MMNPs). The results demonstrated that the synthesised nanoparticle, CM-MMNPs, displayed excellent colloidal stability, robust targeting efficacy for homologous cancer cells, and dual-mode imaging capabilities (MRI and fluorescence).

Enhanced PDT properties of CM-MMNPs, exhibiting a 1O2 generation rate of 0.048 min−1 were obtained. The results indicate that CM-MMNPs had a pronounced selectivity for homologous cancer cells, and the MnO2 layer may be eroded within tumour cells, facilitating fluorescence imaging and disease diagnosis. In vitro, CM-MMNPs also exhibited favourable biocompatibility and antiproliferative properties. The results indicate the potential for employing PS-MOF hybrid composites in a combinatorial strategy for cancer treatment.

4.3. Principle of Operation for PTT

The operational principles of photothermal PS-MOF/COF-based compounds are intricate and varied. In most photothermal COFs/MOFs containing PS, the S

1 state typically experiences nonradiative vibrational relaxation, reverting to the ground state through collisions between chromophores and the surrounding biological milieu, thereby dissipating energy as heat [

34,

101,

106,

107]. Conversely, highly carrier-dose materials, including semiconductors, metals, metal oxides, and quantum dots, can exhibit a photothermal effect via localised plasmon surface resonance [

108,

109]. When this collective oscillation of electrons diminishes through nonradiative transition, energy is released as heat. In semiconductors with low electron density, thermal energy is produced by recombining electron-hole pairs. Irradiating them will elevate their electrons to a higher energy state in the conduction band, creating a vacancy in the valence band. The electrons and holes will dissipate energy as heat, transitioning to the band edges via vibrational relaxation, recombining near the band edge, and subsequently producing further heat by crystal lattice vibrations [

110,

111].

4.3.1. PS-MOF/COF-Based Combination Therapy (PDT, PTT, and Imaging) for Cancer Treatment

Innovative combination treatments are being formulated to enhance cancer treatment. Phototherapy demonstrates distinct advantages in therapeutic applications, including remote controllability, improved selectivity, and reduced biotoxicity compared to chemotherapy. Fluorescence imaging is an effective modality for both in vitro and in vivo applications due to its non-invasive nature and high signal sensitivity [

112]. Fluorescence imaging depends on the characteristics of fluorophores that absorb photon energy within a specific wavelength range and subsequently emit photon energy at longer wavelengths. To enhance safety and therapeutic efficacy, imaging-guided therapy is crucial as it incorporates visual information to infer the distribution and metabolism of the probe.

PDT and PTT are appealing approaches because they are not overly invasive, they are simple to administer, and they have a low level of systemic toxicity and adverse effects. The processes responsible for the synergy between PDT and PTT can be examined at cellular and tissue levels. Regarding the latter, PTT can target hypoxic tumour locations that may be resistant to the conventional oxygen-dependent PDT. Additionally, PTT has the potential to cause additional cell death in the event that the local oxygen levels are low after PDT [

113]. The efficacy of bioimaging/PTT/PDT and photostability can be enhanced by integrating PS in MOFs and COFs [

114,

115].

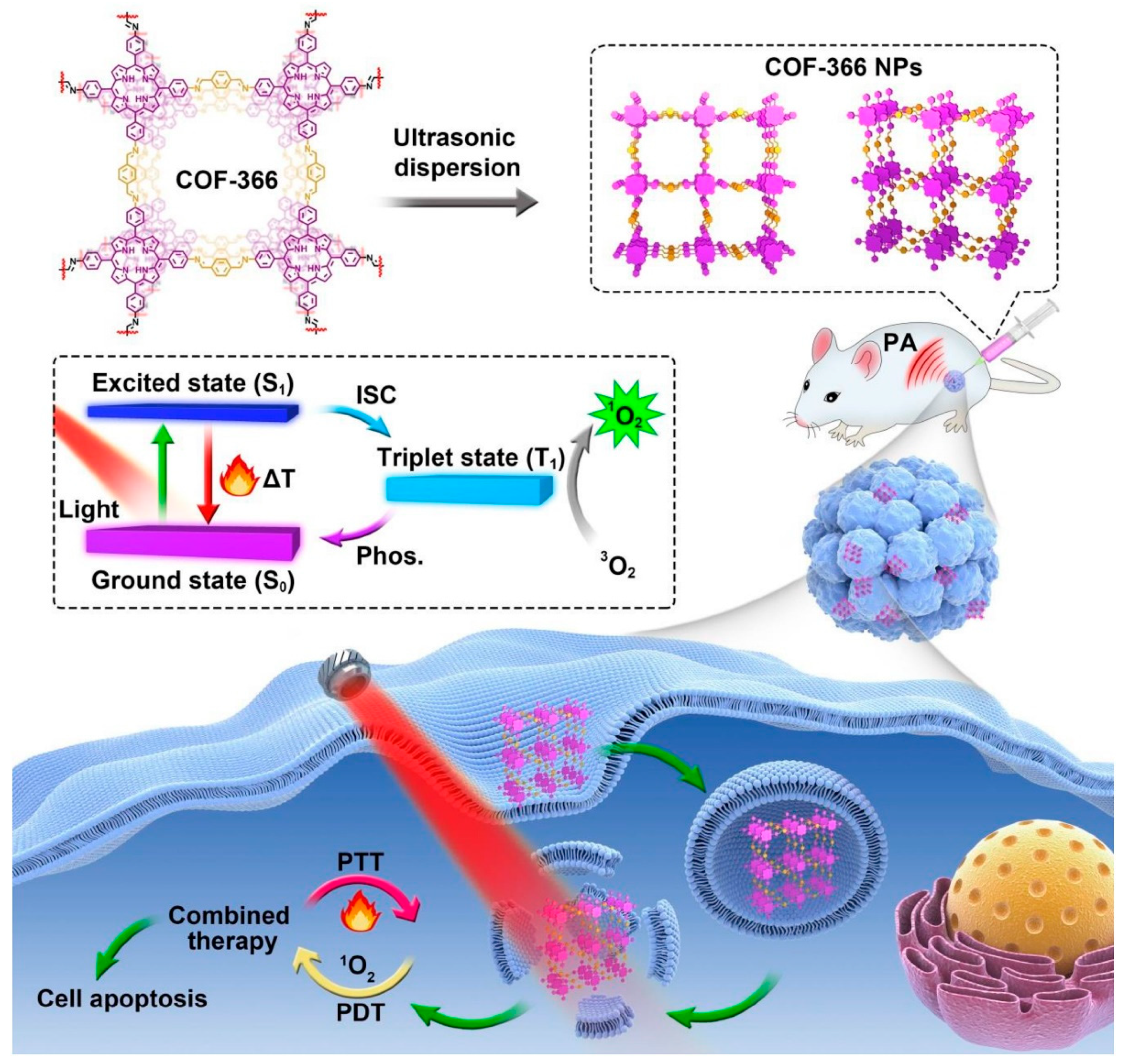

To make phototherapy more practicable, cancer theranostics must execute simultaneous PDT in a simple, secure, and effective method. Dianwei Wang, Zhe Zhang, and others synthesised p-COF-based nanoparticles (COF-366 NPs) for photoacoustic imaging-guided photodynamic and photothermal cancer therapy under a single wavelength light source [

3],

Figure 5. Even with big tumours, COF-366 NPs provided PTT and PDT with a single wavelength light source.

Biodegradability, hemocompatibility, and photostability were excellent for COF-366 NPs. They produced ROS under laser irradiation, causing 4T1 cell death and cytotoxicity. COF-366 NPs aggregated in tumours and suppressed them during laser irradiation. CoF-366 NPs generated ROS in cells and had photothermal activity, enabling PDT and PTT. The combination of PDT and PTT actions of COF-366 NPs completely inhibited big tumors in 4T1 tumor-bearing mice. The study found that COF-366 NPs can completely inhibit big tumors in 4T1 tumor-bearing mice with a single injection and light source.

In a similar study, Hui Zhang, Yu-Hao Li, Yang Chen, and associates [

116] developed a novel core-shell nanocomposite for dual-modality imaging-guided PTT and PDT, noted for its minimal cytotoxicity and biotoxicity. During its formation, the Fe₃O₄@C@PMOF nanocomposite was synthesised by incorporating a p-MOF into the Fe₃O₄@C core. In vivo investigations were conducted on female BALB/c-nu mice bearing MCF-7 breast cancer xenografts. The Fe

3O

4@C@PMOF nanocomposite demonstrated significant tumor accumulation, effective cancer treatment, and minimal damage to healthy tissues. The nanocomposite exhibited dual-modality imaging-guided PTT and PDT treatment functionalities. The Fe

3O

4@C@PMOF nanocomposites showed significant efficacy in producing

1O

2 when subjected to 655 nm laser irradiation, with an estimated

1O

2 quantum yield of 44.38%. The nanocomposites demonstrated significant biocompatibility and durability, whereas the combination of PDT and PDT yielded superior therapeutic efficacy relative to monotherapy.

5. Conclusion and Prospects

This review encapsulates a collection of PS-MOF/COF hybrids and suggests their promising applications in photodynamic therapy, photothermal treatment, and imaging agents. Both COF and MOF exhibit crystalline and porous structures; they can be engineered with tailored features and may undergo post-synthetic modification—advantages not commonly associated with other nanomaterials. In contrast to traditional nano-based materials, COFs and MOFs possess significant potential in biomedicine and demonstrate several advantages, such as excellent biocompatibility, minimal toxicity, and improved photothermal conversion. These hybrid nanocarriers can generate singlet oxygen due to their PS base in photodynamic therapy, eliminating adjacent cancer cells by producing harmful singlet oxygen. Furthermore, incorporating COF/MOF carriers for PS diminishes self-aggregation and quenching of the PS, significantly improving their efficacy for phototherapy and bioimaging. The porous structure and readily adjustable characteristics of COFs and MOFs render them an exceptional platform for imaging-guided and combination therapies. Nevertheless, the utilisation of hybrid materials comprising MOFs and COFs in biological research remains nascent compared to traditional nanomaterials like mesoporous silica. Numerous difficulties remain to be resolved. The complex COF and MOF materials preparation processes and their extended biocompatibility significantly limit their practical application. Consequently, substantial efforts must be dedicated to designing and fabricating PS-based MOFs and COFs with specific shapes and optimal characteristics. Moreover, the promising performance of MOFs in biological applications is mitigated by the instability of certain MOFs and the toxicity associated with many metal centres. Ultimately, any MOFs or COFs intended for clinical use must first comply with rigorous safety and efficacy standards established by regulatory organisations. We assert that the intelligent self-assembly strategy, incorporation of targeted imaging, and the combined PTT/PDT therapeutic impact offer a progressive methodology for developing more sophisticated platforms to combat bacterial infections.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.; formal analysis, A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.; writing—review and editing, A.M. The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author acknowledges Walter Sisulu University's (WSU) support and APC funding from the Directorate of Research Development and Innovation, WSU, South Africa.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ren, S.-Z.; Zhu, X.-H.; Wang, B.; Liu, M.; Li, S.-K.; Yang, Y.-S.; An, H.; Zhu, H.-L. , A versatile nanoplatform based on multivariate porphyrinic metal–organic frameworks for catalytic cascade-enhanced photodynamic therapy. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2021, 9, 4678–4689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Zhen, W.; McCleary, C.; Luo, T.; Jiang, X.; Peng, C.; Weichselbaum, R. R.; Lin, W. , Nanoscale Metal–Organic Framework with an X-ray Triggerable Prodrug for Synergistic Radiotherapy and Chemotherapy. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2023, 145, 18698–18704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, L.; Liu, F.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Li, Y.; Tian, H.; Chen, X. , Porphyrin-based covalent organic framework nanoparticles for photoacoustic imaging-guided photodynamic and photothermal combination cancer therapy. Biomaterials 2019, 223, 119459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharya, B.; Behera, A.; Behera, S.; Moharana, S. , Recent Advances in Nanotechnology-Based Drug Delivery Systems for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Reproductive Disorders. ACS Applied Bio Materials 2024, 7, 1336–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M. J.; Billingsley, M. M.; Haley, R. M.; Wechsler, M. E.; Peppas, N. A.; Langer, R. , Engineering precision nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2021, 20, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochubiojo, M.; Chinwude, I.; Ibanga, E.; Ifianyi, S., Nanotechnology in Drug Delivery. InTech: 2012.

- Galstyan, A. , Turning Photons into Drugs: Phthalocyanine-Based Photosensitizers as Efficient Photoantimicrobials. Chemistry – A European Journal 2021, 27, 1903–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malacarne, M. C.; Banfi, S.; Rugiero, M.; Caruso, E. , Drug delivery systems for the photodynamic application of two photosensitizers belonging to the porphyrin family. Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences 2021, 20, 1011–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porubský, M.; Gurská, S.; Stanková, J.; Hajdúch, M.; Džubák, P.; Hlaváč, J. , AminoBODIPY Conjugates for Targeted Drug Delivery Systems and Real-Time Monitoring of Drug Release. Molecular Pharmaceutics 2021, 18, 2385–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Lee, K.; Zunbul, Z.; Lee, I.; Kim, E.; Chi, S. G.; Kim, J. S. , Covalent organic framework nanomedicines: Biocompatibility for advanced nanocarriers and cancer theranostics applications. Bioact Mater 2023, 21, 358–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghi, O. M.; O'Keeffe, M.; Ockwig, N. W.; Chae, H. K.; Eddaoudi, M.; Kim, J. , Reticular synthesis and the design of new materials. Nature 2003, 423, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younas, R.; Jubeen, F.; Bano, N.; Andreescu, S.; Zhang, H.; Hayat, A. , Covalent organic frameworks (COFs) as carrier for improved drug delivery and biosensing applications. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 2024, 121, 2017–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, T.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, R.; Liu, X.; Ni, B.; Wei, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yuan, W.; Peng, H.; Jiang, Z.; Zhao, Y. , Porphyrin-Based Covalent Organic Frameworks Anchoring Au Single Atoms for Photocatalytic Nitrogen Fixation. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2023, 145, 6057–6066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, P.; Arora, S.; Pan, Y.; Ahmed, I.; Kumar, S.; Parshad, B. , Tailoring Indocyanine Green J-Aggregates for Imaging, Cancer Phototherapy, and Drug Delivery: A Review. ACS Applied Bio Materials 2024, 7, 5121–5135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; Xu, Y.; Hu, F.; Zhai, L.; Huang, Y.; Qiao, H.; Xiong, J.; Yang, D.; Ni, Z.; Zheng, X.; Mi, L. , Fluorinated covalent organic frameworks for efficient drug delivery. RSC Advances 2022, 12, 31276–31281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, R.; Zaremba, O.; Arnauts, G.; Ameloot, R.; Skorupskii, G.; Dincă, M.; Bavykina, A.; Gascon, J.; Ejsmont, A.; Goscianska, J.; Kalmutzki, M.; Lächelt, U.; Ploetz, E.; Diercks, C. S.; Wuttke, S. , The Current Status of MOF and COF Applications. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2021, 60, 23975–24001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yadav, A.; Zhou, H.; Roy, K.; Thanasekaran, P.; Lee, C., Advances and Applications of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) in Emerging Technologies: A Comprehensive Review. Global Challenges 2024, 8, (2).

- Mansour, F. R.; Hammad, S. F.; Abdallah, I. A.; Bedair, A.; Abdelhameed, R. M.; Locatelli, M. , Applications of metal organic frameworks in point of care testing. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2024, 172, 117596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkhoo, E.; Mallakpour, S.; Hussain, C. M. , Design, synthesis, and application of covalent organic frameworks as catalysts. New Journal of Chemistry 2023, 47, 6765–6788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P.; Banerjee, P. , Drug delivery using biocompatible covalent organic frameworks (COFs) towards a therapeutic approach. Chemical Communications 2023, 59, 12527–12547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huxford, R. C.; Della Rocca, J.; Lin, W. , Metal–organic frameworks as potential drug carriers. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 2010, 14, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Q.; Zhou, L.-L.; Li, W.-Y.; Li, Y.-A.; Dong, Y.-B. , Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) for Cancer Therapeutics. Chemistry – A European Journal 2020, 26, 5583–5591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, W.; Tian, J.; Bu, F.; Zhao, T.; Liu, M.; Lin, R.; Zhang, F.; Lee, M.; Zhao, D.; Li, X., Imparting multi-functionality to covalent organic framework nanoparticles by the dual-ligand assistant encapsulation strategy. Nature Communications 2021, 12, (1).

- Mittal, A.; Roy, I.; Gandhi, S., Drug Delivery Applications of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs). IntechOpen: 2022.

- Riccò, R.; Liang, W.; Li, S.; Gassensmith, J. J.; Caruso, F.; Doonan, C.; Falcaro, P. , Metal–Organic Frameworks for Cell and Virus Biology: A Perspective. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shano, L. B.; Karthikeyan, S.; Kennedy, L. J.; Chinnathambi, S.; Pandian, G. N. , MOFs for next-generation cancer therapeutics through a biophysical approach—a review. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon-Yarza, T.; Mielcarek, A.; Couvreur, P.; Serre, C. , Nanoparticles of Metal-Organic Frameworks: On the Road to In Vivo Efficacy in Biomedicine. Advanced Materials 2018, 30, 1707365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljazzar, S. O. , Encapsulation of the anticancer drug doxorubicin within metal-organic frameworks: Spectroscopic analysis, exploration of anticancer, antioxidant, antibacterial properties, and optimization through Box-Behnken design. Journal of the Indian Chemical Society 2024, 101, 101125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Tang, Y.; Cao, W.; Cui, Y.; Qian, G. , Highly Efficient Encapsulation of Doxorubicin Hydrochloride in Metal–Organic Frameworks for Synergistic Chemotherapy and Chemodynamic Therapy. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2021, 7, 4999–5006. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, T.; Guo, T.; He, Y.; Cao, Z.; Xu, H.; Wu, W.; Wu, L.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, J. , Lactone Stabilized by Crosslinked Cyclodextrin Metal-Organic Frameworks to Improve Local Bioavailability of Topotecan in Lung Cancer. Pharmaceutics 2022, 15, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javanbakht, S.; Hemmati, A.; Namazi, H.; Heydari, A. , Carboxymethylcellulose-coated 5-fluorouracil@MOF-5 nano-hybrid as a bio-nanocomposite carrier for the anticancer oral delivery. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 155, 876–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padya, B. S.; Fernandes, G.; Hegde, S.; Kulkarni, S.; Pandey, A.; Deshpande, P. B.; Ahmad, S. F.; Upadhya, D.; Mutalik, S. , Targeted Delivery of 5-Fluorouracil and Sonidegib via Surface-Modified ZIF-8 MOFs for Effective Basal Cell Carcinoma Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, S. R.; Calori, I. R.; Tedesco, A. C. , Photosensitizer-based metal-organic frameworks for highly effective photodynamic therapy. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2021, 131, 112514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T. C.; Nguyen, V.-N.; Choi, Y.; Lee, S.; Yoon, J. , Recent Strategies to Develop Innovative Photosensitizers for Enhanced Photodynamic Therapy. Chemical Reviews 2021, 121, 13454–13619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Cao, J. , Recent Progress of Metal-Organic Framework-Based Photodynamic Therapy for Cancer Treatment. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2022, Volume 17, 2367–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuramochi, Y.; Satake, A. , Porphyrins Acting as Photosensitizers in the Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction Reaction. Catalysts 2023, 13, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddah, H. A.; Berry, V.; Behura, S. K. , Biomolecular photosensitizers for dye-sensitized solar cells: Recent developments and critical insights. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2020, 121, 109678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariño-Ocampo, N.; Dibona-Villanueva, L.; Escobar-Álvarez, E.; Guerra-Díaz, D.; Zúñiga-Núñez, D.; Fuentealba, D.; Robinson-Duggon, J. , Recent Photosensitizer Developments, Delivery Strategies and Combination-based Approaches for Photodynamic Therapy<sup>†</sup>. Photochemistry and Photobiology 2023, 99, 469–497. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, B.; Lu, C.; Quan, G.; Huang, Z.; Wu, C.; Pan, X. , An oxygen-generating metal organic framework nanoplatform as a “synergy motor” for extricating dilemma over photodynamic therapy. Materials Advances 2023, 4, 5420–5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, X.; Yang, C.; Cheng, K.; Tan, T.; Lv, Y.; Liu, Y. , Hybrid Porous Crystalline Materials from Metal Organic Frameworks and Covalent Organic Frameworks. Advanced Science 2021, 8, 2101883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlou, G. G.; Abrahamse, H. , Nanoscale metal–organic frameworks as photosensitizers and nanocarriers in photodynamic therapy. Frontiers in Chemistry 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songca, S. P. , Synthesis and applications of metal organic frameworks in photodynamic therapy. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology 2024, 23, 100245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raptopoulou, C. P. , Metal-Organic Frameworks: Synthetic Methods and Potential Applications. Materials 2021, 14, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Shao, Q.; Song, Q.; Cui, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, B.; Ge, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Vajtai, R.; Ajayan, P. M.; Wang, H.; Xu, T.; Wu, Y. , A solvent-assisted ligand exchange approach enables metal-organic frameworks with diverse and complex architectures. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Du, L.; Wu, C., Chapter 7 - Hydrothermal synthesis of MOFs. In Metal-Organic Frameworks for Biomedical Applications, Mozafari, M., Ed. Woodhead Publishing: 2020; pp 141-157.

- Rodríguez-Carríllo, C.; Benítez, M.; El Haskouri, J.; Amorós, P.; Ros-Lis, J. V. , Novel Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of COFs: 2020–2022. Molecules 2023, 28, 3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Ignacz, G.; Szekely, G. , Synthesis of covalent organic frameworks using sustainable solvents and machine learning. Green Chemistry 2021, 23, 8932–8939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, H.; Yusran, Y.; Xue, M.; Fang, Q.; Yan, Y.; Valtchev, V.; Qiu, S. , Fast, Ambient Temperature and Pressure Ionothermal Synthesis of Three-Dimensional Covalent Organic Frameworks. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2018, 140, 4494–4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzehpoor, E.; Effaty, F.; Borchers, T. H.; Stein, R. S.; Wahrhaftig-Lewis, A.; Ottenwaelder, X.; Friščić, T.; Perepichka, D. F. , Mechanochemical Synthesis of Boroxine-linked Covalent Organic Frameworks. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bhunia, S.; Deo, K. A.; Gaharwar, A. K. , 2D Covalent Organic Frameworks for Biomedical Applications. Advanced Functional Materials 2020, 30, 2002046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wu, L.; Li, X.; Sun, H.; Xiong, T.; Liu, J.; Huang, C.; Xu, H.; Sun, H.; Chen, W.; Gref, R.; Zhang, J. , Metal-organic frameworks for advanced drug delivery. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 2021, 11, 2362–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, H. D.; Walton, S. P.; Chan, C. , Metal–Organic Frameworks for Drug Delivery: A Design Perspective. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2021, 13, 7004–7020. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Wan, W.; Guo, P.; Nyström, A. M.; Zou, X. , One-pot Synthesis of Metal–Organic Frameworks with Encapsulated Target Molecules and Their Applications for Controlled Drug Delivery. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2016, 138, 962–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong Hoang, Q.; Kim, M.; Kim, B. C.; Lee, C. Y.; Shim, M. S. , Pro-oxidant drug-loaded porphyrinic zirconium metal-organic-frameworks for cancer-specific sonodynamic therapy. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2022, 209, (Pt 1), 112189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Wei, Y.; Wang, S.; Qiao, Q.; Heng, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Y.; Qian, S. , Improving Tabletability of Excipients by Metal-Organic Framework-Based Cocrystallization: a Study of Mannitol and CaCl2. Pharmaceutical Research 2020, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghe, A.; Strudwick, B.; Dawson, D. M.; Ashbrook, S. E.; Woutersen, S.; Dubbeldam, D.; Tanase, S. , Synthesis of Chiral MOF-74 Frameworks by Post-Synthetic Modification by Using an Amino Acid. Chemistry – A European Journal 2020, 26, 13957–13965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W. , Matel Organic Frameworks in Drug Delivery: Synthesis and Drug Loading Strategies. MATEC Web of Conferences 2024, 404, 03013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulys, A.; Hanifah, N.; Umar, A.; Satya, A.; Adawiah, A. , Zirconium-Based Metal-Organic Framework Impregnated With Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs@MOF-808) As The Anticancer Drug Delivery System. Egyptian Journal of Chemistry 2023, 0, 119–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, J. Y.; Kim, M. , Covalent connections between metal–organic frameworks and polymers including covalent organic frameworks. Chemical Society Reviews 2023, 52, 6379–6416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Obacz, J.; Emanuelli, G.; Chambers, J. E.; Abreu, S.; Chen, X.; Linnane, E.; Mehta, J. P.; Wheatley, A. E. H.; Marciniak, S. J.; Fairen-Jimenez, D. , Enhancing Drug Delivery Efficacy Through Bilayer Coating of Zirconium-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks: Sustained Release and Improved Chemical Stability and Cellular Uptake for Cancer Therapy. Chemistry of Materials 2024, 36, 3588–3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueneli, N.; McKenna, A. M.; Ohkouchi, N.; Boreham, C. J.; Beghin, J.; Javaux, E. J.; Brocks, J. J. , 1.1-billion-year-old porphyrins establish a marine ecosystem dominated by bacterial primary producers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, E6978–E6986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahoun, M.; Gee, C. T.; McCoy, V. E.; Sander, P. M.; Müller, C. E. , Chemistry of porphyrins in fossil plants and animals. RSC Advances 2021, 11, 7552–7563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Chen, K.; Li, T.-T. , Porphyrin and phthalocyanine based covalent organic frameworks for electrocatalysis. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2022, 464, 214563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Huang, D.; Lai, C.; Zeng, G.; Qin, L.; Wang, H.; Yi, H.; Li, B.; Liu, S.; Zhang, M.; Deng, R.; Fu, Y.; Li, L.; Xue, W.; Chen, S. , Recent advances in covalent organic frameworks (COFs) as a smart sensing material. Chemical Society Reviews 2019, 48, 5266–5302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-San-Miguel, D.; Montoro, C.; Zamora, F. , Covalent organic framework nanosheets: preparation, properties and applications. Chemical Society Reviews 2020, 49, 2291–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, A. P.; Benin, A. I.; Ockwig, N. W.; O'Keeffe, M.; Matzger, A. J.; Yaghi, O. M. , Porous, Crystalline, Covalent Organic Frameworks. Science 2005, 310, 1166–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Kaderi, H. M.; Hunt, J. R.; Mendoza-Cortés, J. L.; Côté, A. P.; Taylor, R. E.; O'Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O. M. , Designed Synthesis of 3D Covalent Organic Frameworks. Science 2007, 316, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowan, S. J.; Cantrill, S. J.; Cousins, G. R. L.; Sanders, J. K. M.; Stoddart, J. F. , Dynamic Covalent Chemistry. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2002, 41, 898–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, A.; Gasparini, G.; Matile, S. , Functional systems with orthogonal dynamic covalent bonds. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 1948–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana-Tavra, C.; Köppen, M.; Li, A.; Stock, N.; Fairen-Jimenez, D. , Biocompatible, Crystalline, and Amorphous Bismuth-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks for Drug Delivery. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2020, 12, 5633–5641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Qutub, S.; Khashab, N. M. , Biocompatibility and biodegradability of metal organic frameworks for biomedical applications. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2021, 9, 5925–5934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, N.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Y.; Yuan, J.; Wang, D.; Ma, G.; Dong, J.; Sun, X. , Biodegradable two-dimensional nanomaterials for cancer theranostics. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2022, 458, 214415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, B.; Sun, J.; Hu, W.; Wang, H. , Recent advances in porous nanostructures for cancer theranostics. Nano Today 2021, 38, 101146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klausen, M.; Ucuncu, M.; Bradley, M. , Design of Photosensitizing Agents for Targeted Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy. Molecules 2020, 25, 5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubrak, T. P.; Kołodziej, P.; Sawicki, J.; Mazur, A.; Koziorowska, K.; Aebisher, D. , Some Natural Photosensitizers and Their Medicinal Properties for Use in Photodynamic Therapy. Molecules 2022, 27, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, S.; Knap, B.; Przystupski, D.; Saczko, J.; Kędzierska, E.; Knap-Czop, K.; Kotlińska, J.; Michel, O.; Kotowski, K.; Kulbacka, J. , Photodynamic therapy – mechanisms, photosensitizers and combinations. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2018, 106, 1098–1107. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Hur, E.; Kol, R.; Marko, R.; Riklis, E.; Rosenthal, I. , Combined Action of Phthalocyanine Photosensitization and Gamma-radiation on Mammalian Cells. International Journal of Radiation Biology 1988, 54, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolmans, D. E. J. G. J.; Fukumura, D.; Jain, R. K. , Photodynamic therapy for cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer 2003, 3, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filonenko, E. V.; Sokolov, V. V.; Chissov, V. I.; Lukyanets, E. A.; Vorozhtsov, G. N. , Photodynamic therapy of early esophageal cancer. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2008, 5, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z. , An update on the regulatory status of PDT photosensitizers in China. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2008, 5, 285–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. D.; Baron, E. D.; Scull, H.; Hsia, A.; Berlin, J. C.; McCormick, T.; Colussi, V.; Kenney, M. E.; Cooper, K. D.; Oleinick, N. L. , Photodynamic therapy with the phthalocyanine photosensitizer Pc 4: The case experience with preclinical mechanistic and early clinical–translational studies. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 2007, 224, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sounik, J.; Rihter, B.; Ford, W.; Rodgers, M.; Kenney, M., Naphthalocyanines relevant to the search for second-generation PDT sensitizers. SPIE: 1991; Vol. 1426.

- Uspenskiĭ, L. V.; Chistov, L. V.; Kogan, E. A.; Loshchenov, V. B.; Ablitsov, I.; Rybin, V. K.; Zavodnov, V.; Shiktorov, D. I.; Serbinenko, N. F.; Semenova, I. G. , [Endobronchial laser therapy in complex preoperative preparation of patients with lung diseases]. Khirurgiia (Mosk) 2000, 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kipp, J. E. , The role of solid nanoparticle technology in the parenteral delivery of poorly water-soluble drugs. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2004, 284, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ould-Ouali, L.; Noppe, M.; Langlois, X.; Willems, B.; Te Riele, P.; Timmerman, P.; Brewster, M. E.; Ariën, A.; Préat, V. , Self-assembling PEG-p(CL-co-TMC) copolymers for oral delivery of poorly water-soluble drugs: a case study with risperidone. Journal of Controlled Release 2005, 102, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. C.; Gillies, E. R.; Fox, M. E.; Guillaudeu, S. J.; Fréchet, J. M. J.; Dy, E. E.; Szoka, F. C. , A single dose of doxorubicin-functionalized bow-tie dendrimer cures mice bearing C-26 colon carcinomas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2006, 103, 16649–16654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Sasmal, H. S.; Kundu, T.; Kandambeth, S.; Illath, K.; Díaz Díaz, D.; Banerjee, R. , Targeted Drug Delivery in Covalent Organic Nanosheets (CONs) via Sequential Postsynthetic Modification. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2017, 139, 4513–4520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.; Sun, Y.; Chu, J.; Zhang, X.; Deng, H. , Multivariate Metal–Organic Frameworks for Dialing-in the Binding and Programming the Release of Drug Molecules. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2017, 139, 14209–14216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preiß, T.; Zimpel, A.; Wuttke, S.; Rädler, J. , Kinetic Analysis of the Uptake and Release of Fluorescein by Metal-Organic Framework Nanoparticles. Materials 2017, 10, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsaiari, S. K.; Patil, S.; Alyami, M.; Alamoudi, K. O.; Aleisa, F. A.; Merzaban, J. S.; Li, M.; Khashab, N. M. , Endosomal Escape and Delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing Machinery Enabled by Nanoscale Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2018, 140, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illes, B.; Wuttke, S.; Engelke, H. , Liposome-Coated Iron Fumarate Metal-Organic Framework Nanoparticles for Combination Therapy. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Nash, G. T.; Xu, Z.; Jiang, X.; Liu, J.; Lin, W. , Nanoscale Metal–Organic Framework Confines Zinc-Phthalocyanine Photosensitizers for Enhanced Photodynamic Therapy. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2021, 143, 13519–13524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X.-Z.; Deng, H. , Covalent Organic Frameworks as Favorable Constructs for Photodynamic Therapy. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2019, 58, 14213–14218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Chen, L.; Wang, L.; Xie, Z. , Photoactive Metal–Organic Framework@Porous Organic Polymer Nanocomposites with pH-Triggered Type I Photodynamic Therapy. Advanced Materials Interfaces 2020, 7, 2000504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Xie, Z. , Mimetic sea cucumber-shaped nanoscale metal-organic frameworks composite for enhanced photodynamic therapy. Dyes and Pigments 2022, 197, 109920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Q.; Fu, D.-D.; Li, Y.-A.; Kong, X.-M.; Wei, Z.-Y.; Li, W.-Y.; Zhang, S.-J.; Dong, Y.-B. , BODIPY-Decorated Nanoscale Covalent Organic Frameworks for Photodynamic Therapy. iScience 2019, 14, 180–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhou, F.; Guan, K.; Wang, Y.; Fu, X.; Yang, Y.; Yin, X.; Song, G.; Zhang, X.-B.; Tan, W. , <i>In vivo</i> therapeutic response monitoring by a self-reporting upconverting covalent organic framework nanoplatform. Chemical Science 2020, 11, 1299–1306. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, S.; Tong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Hu, Y.; Yuan, A. , Covalent Organic Framework-Supported Molecularly Dispersed Near-Infrared Dyes Boost Immunogenic Phototherapy against Tumors. Advanced Functional Materials 2019, 29, 1902757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeRosa, M. C.; Crutchley, R. J., Photosensitized singlet oxygen and its applications. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2002, 233-234, 351-371.

- Lan, G.; Ni, K.; Veroneau, S. S.; Feng, X.; Nash, G. T.; Luo, T.; Xu, Z.; Lin, W. , Titanium-Based Nanoscale Metal–Organic Framework for Type I Photodynamic Therapy. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2019, 141, 4204–4208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filatov, M. A. , Heavy-atom-free BODIPY photosensitizers with intersystem crossing mediated by intramolecular photoinduced electron transfer. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry 2020, 18, 10–27. [Google Scholar]

- Chedid, G.; Yassin, A. , Recent Trends in Covalent and Metal Organic Frameworks for Biomedical Applications. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, A. K.; Priyadarshini, N.; Priyadarshini, P.; Behera, G. C.; Parida, K. , Recent advancements in metal organic framework-modified multifunctional materials for photodynamic therapy. Materials Advances 2024, 5, 6030–6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Z.; Wu, C.; Pan, X.; Huang, Z.; Lu, C.; Quan, G. , Photodynamic therapy for cancer: mechanisms, photosensitizers, nanocarriers, and clinical studies. MedComm 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Ye, Z.; Wei, L.; Luo, H.; Xiao, L. , Cell Membrane-Coated Porphyrin Metal–Organic Frameworks for Cancer Cell Targeting and O2-Evolving Photodynamic Therapy. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2019, 11, 39594–39602. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Q.; Zhou, L.-L.; Li, Y.-A.; Li, W.-Y.; Wang, S.; Song, C.; Dong, Y.-B. , Nanoscale Covalent Organic Framework for Combinatorial Antitumor Photodynamic and Photothermal Therapy. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 13304–13316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K. K.; Zheng, G. , Molecular Interactions in Organic Nanoparticles for Phototheranostic Applications. Chemical Reviews 2015, 115, 11012–11042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, R.; Li, Y.; Song, L.; Xiong, Y. , Coupling Solar Energy into Reactions: Materials Design for Surface Plasmon-Mediated Catalysis. Small 2015, 11, 3873–3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luther, J. M.; Jain, P. K.; Ewers, T.; Alivisatos, A. P. , Localized surface plasmon resonances arising from free carriers in doped quantum dots. Nature Materials 2011, 10, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Liu, X.; Tan, L.; Liang, Y.; Cui, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhu, S.; Li, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Yeung, K. W. K.; Wang, X.; Wu, S. , Photocatalysis: Light-Activated Rapid Disinfection by Accelerated Charge Transfer in Red Phosphorus/ZnO Heterointerface (Small Methods 3/2019). Small Methods 2019, 3, 1970008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Deng, L.; Wei, N.; Weng, Y.; Dong, S.; Qi, D.; Qiu, J.; Chen, X.; Wu, T. , High-performance photothermal conversion of narrow-bandgap Ti2O3 nanoparticles. Advanced materials 2017, 29, 1603730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refaat, A.; Yap, M. L.; Pietersz, G.; Walsh, A. P. G.; Zeller, J.; Del Rosal, B.; Wang, X.; Peter, K. , In vivo fluorescence imaging: success in preclinical imaging paves the way for clinical applications. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overchuk, M.; Weersink, R. A.; Wilson, B. C.; Zheng, G. , Photodynamic and Photothermal Therapies: Synergy Opportunities for Nanomedicine. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 7979–8003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-S.; Wei, X.; Zhao, X.; Chen, L.-J.; Yan, X.-P. , Near-Infrared Photothermal/Photodynamic-in-One Agents Integrated with a Guanidinium-Based Covalent Organic Framework for Intelligent Targeted Imaging-Guided Precision Chemo/PTT/PDT Sterilization. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2021, 13, 27895–27903. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, X.; Ai, F.; Han, L. , Recent Development of MOF-Based Photothermal Agent for Tumor Ablation. Frontiers in Chemistry 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, Y.-H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, M.-M.; Wang, X.-S.; Yin, X.-B. , Fluorescence and Magnetic Resonance Dual-Modality Imaging-Guided Photothermal and Photodynamic Dual-Therapy with Magnetic Porphyrin-Metal Organic Framework Nanocomposites. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 44153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).