Submitted:

19 December 2024

Posted:

25 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Bacterial cellulose (BC) is a biocompatible, non-toxic, non-cytotoxic, non-allergenic, biodegradable, chemically pure (which allows to significantly reduce environmental pollution), unique biopolymer with high elasticity, flexibility, plasticity, water-absorbing and water-retaining properties. BC is a promising biopolymer for various applications. However, its high cost and low productivity hinder large-scale production of BC. The mutant strain Komagataeibacter xylinus MS2530 obtained by us reduced the fermentation time from 14 to 5-7 days. In order to reduce the cost of the resulting BC, brewing waste without sterilization was used as a nutrient medium (while costs are significantly reduced under production conditions). The use of this medium led to an increase in the BC yield by 2-2.5 times compared to the classic HS medium. Various BC modification methods are used to increase the yield and improve the most important properties of BC. In order to modify the BC obtained by us, the method of co-fermentation with different yeast strains was used. As a result of co-fermentation, the yield of BC increased by 4-5 times. The obtained BC and modified BC were studied using SEM, IR-Fourier, etc. The study showed a change in the microstructure and physical properties of the obtained biofilms, which can contribute to the expansion of their application areas. The results we obtained can become a prerequisite for organizing large-scale production of BC and BC biocomposites.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

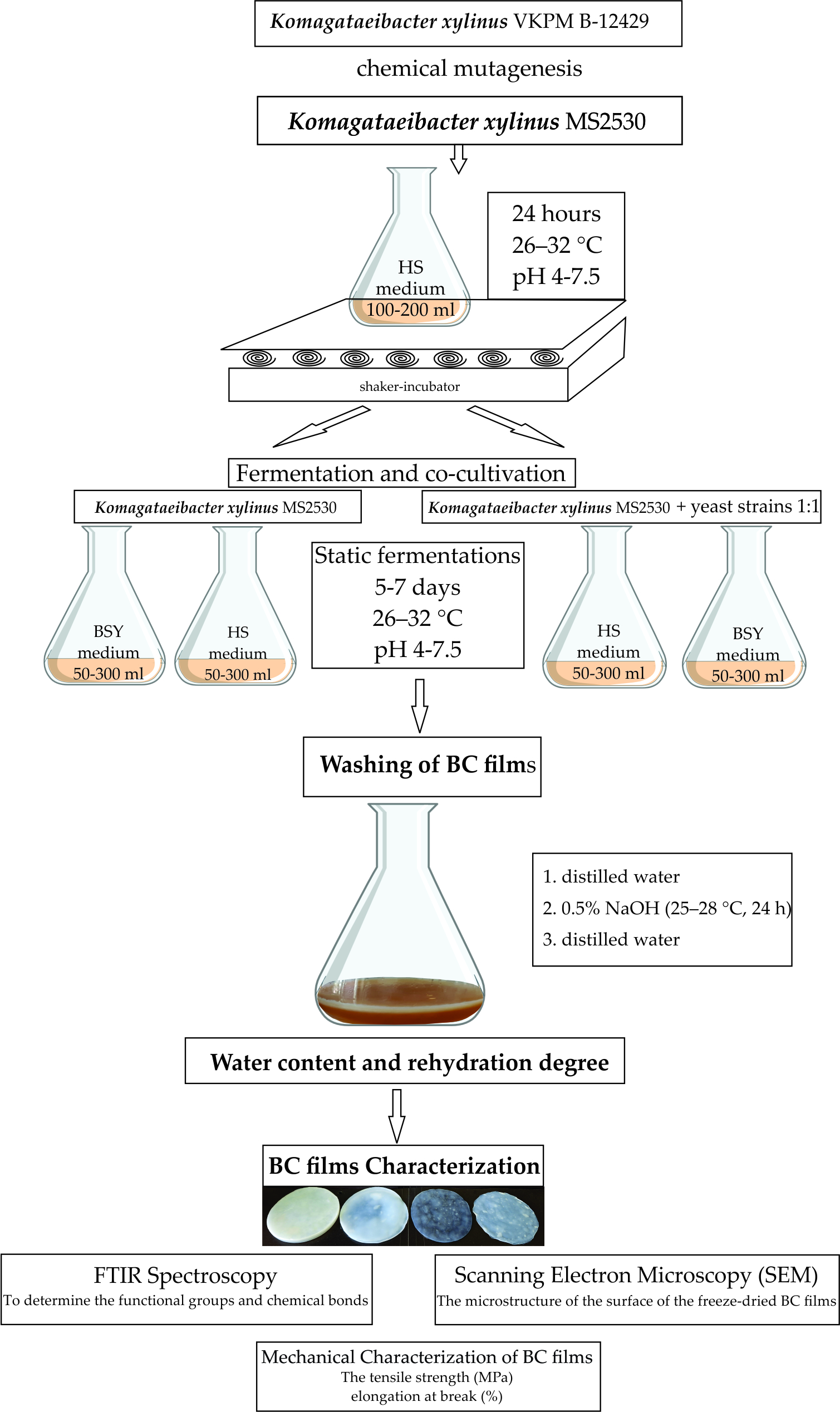

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganisms

2.2. BC Films and BC Modified Films Obtaining and Purification

2.2.1. BC Films and BC Modified Films Obtaining

2.2.2. Purification of BC Films and BC Modified Films

2.3. The Yield of BC and BC Productivity Were Calculated as Described by Jacek et al. [64].

2.4. The Reducing Sugar Content in the Culture Was Determined as Described by Lin et al. [37]

2.5. Water Content and Rehydration Degree of BC Films and BC Modified Films

2.6. BC Films and BC Modified Films Characterizations

2.6.1. Fourier Transformed Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy

2.6.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.7. Mechanical Characterization of BC Films

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

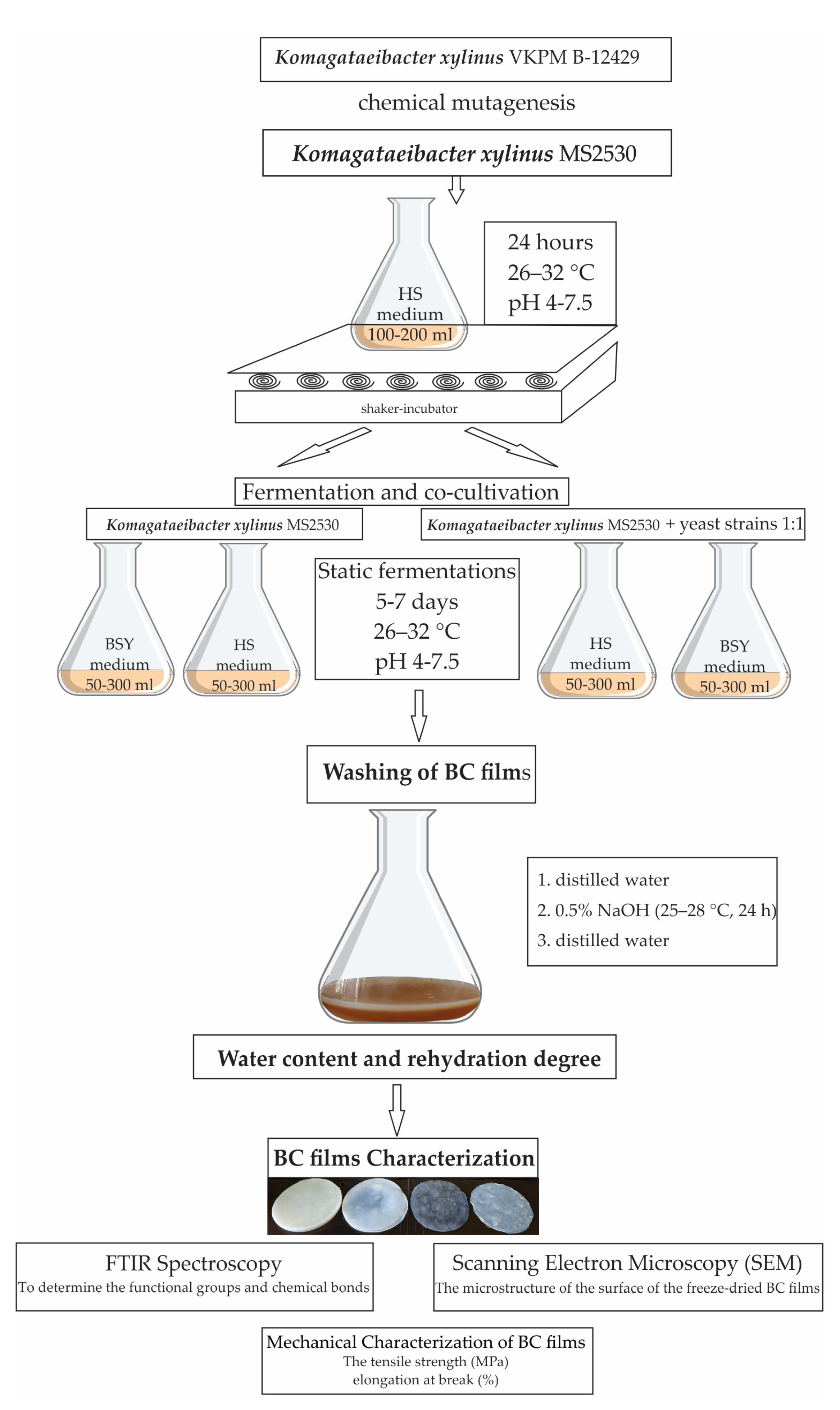

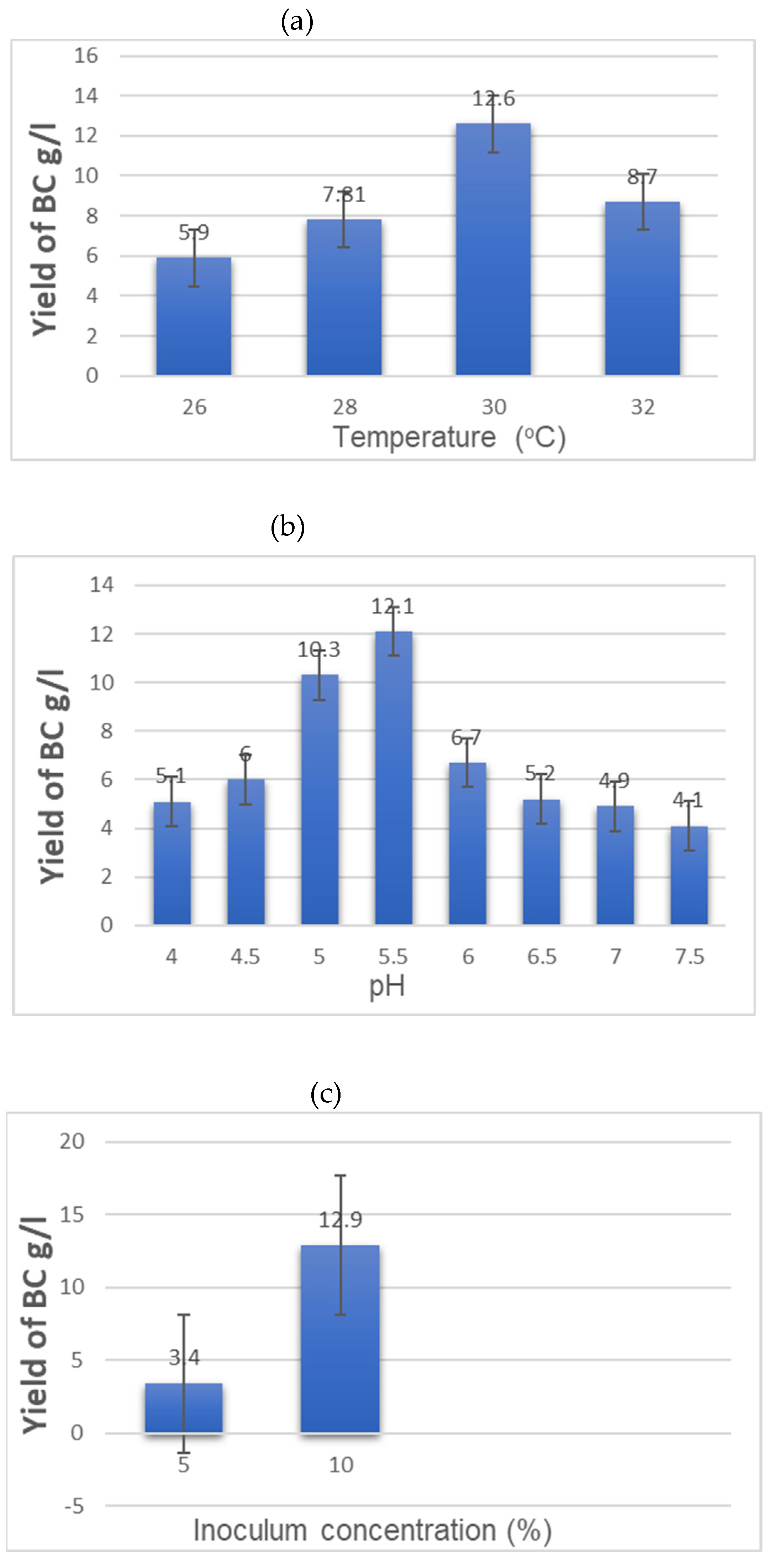

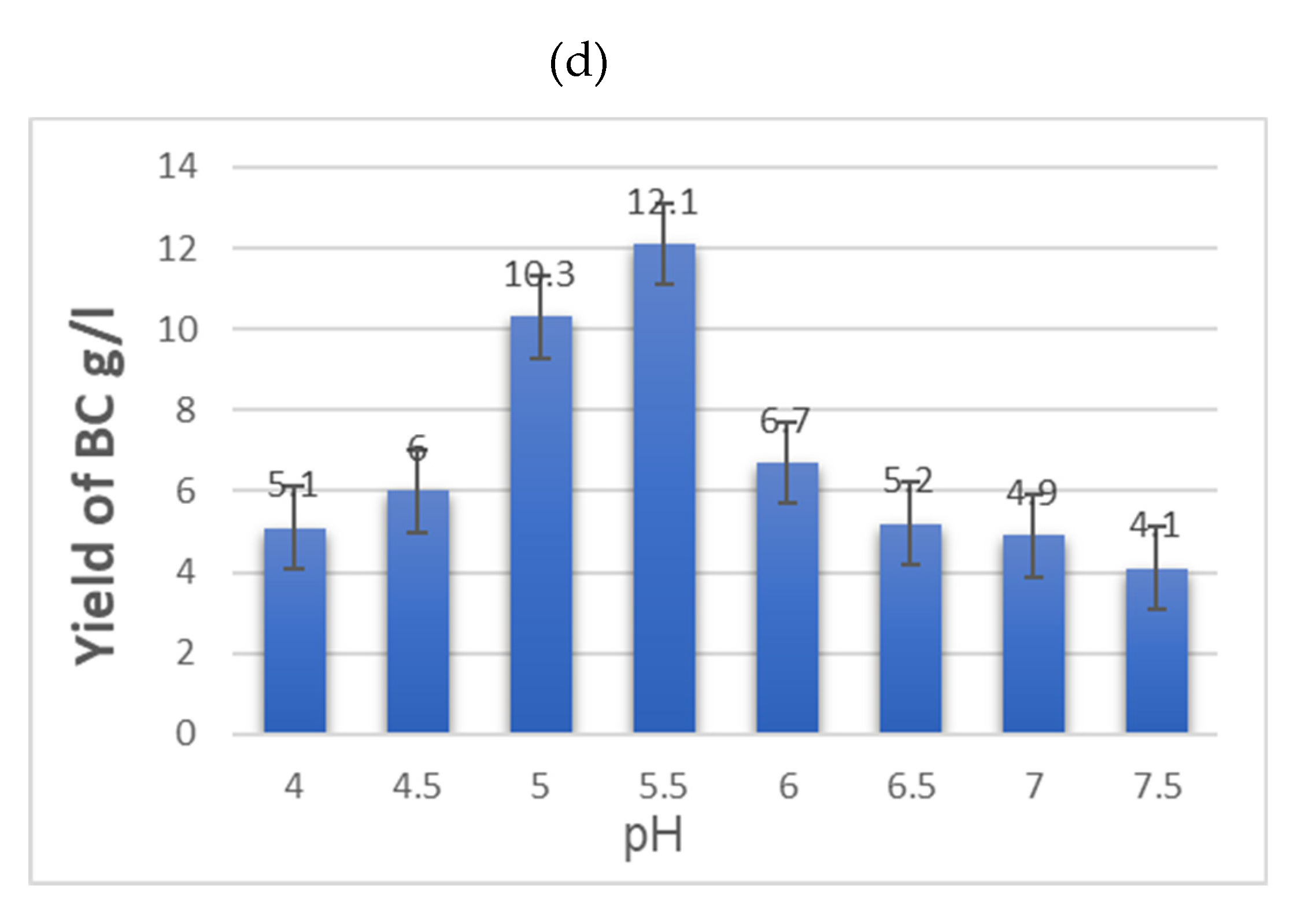

3.1. Study of the Influence of Various Factors on BC Biosynthesis During Fermentation

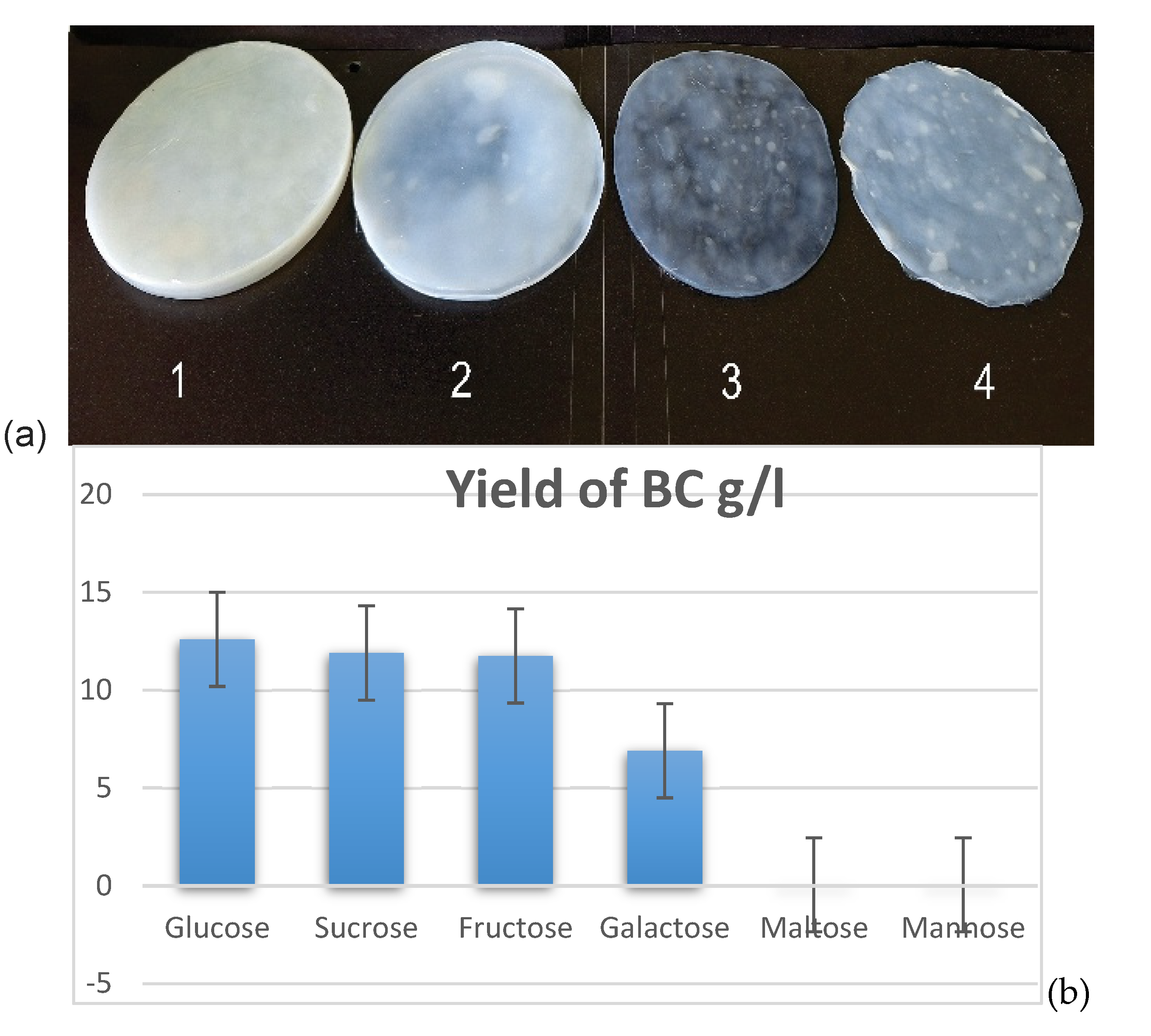

3.2. Cultivation of K. xylinus MC2530 Strain Using Different Carbon Sources

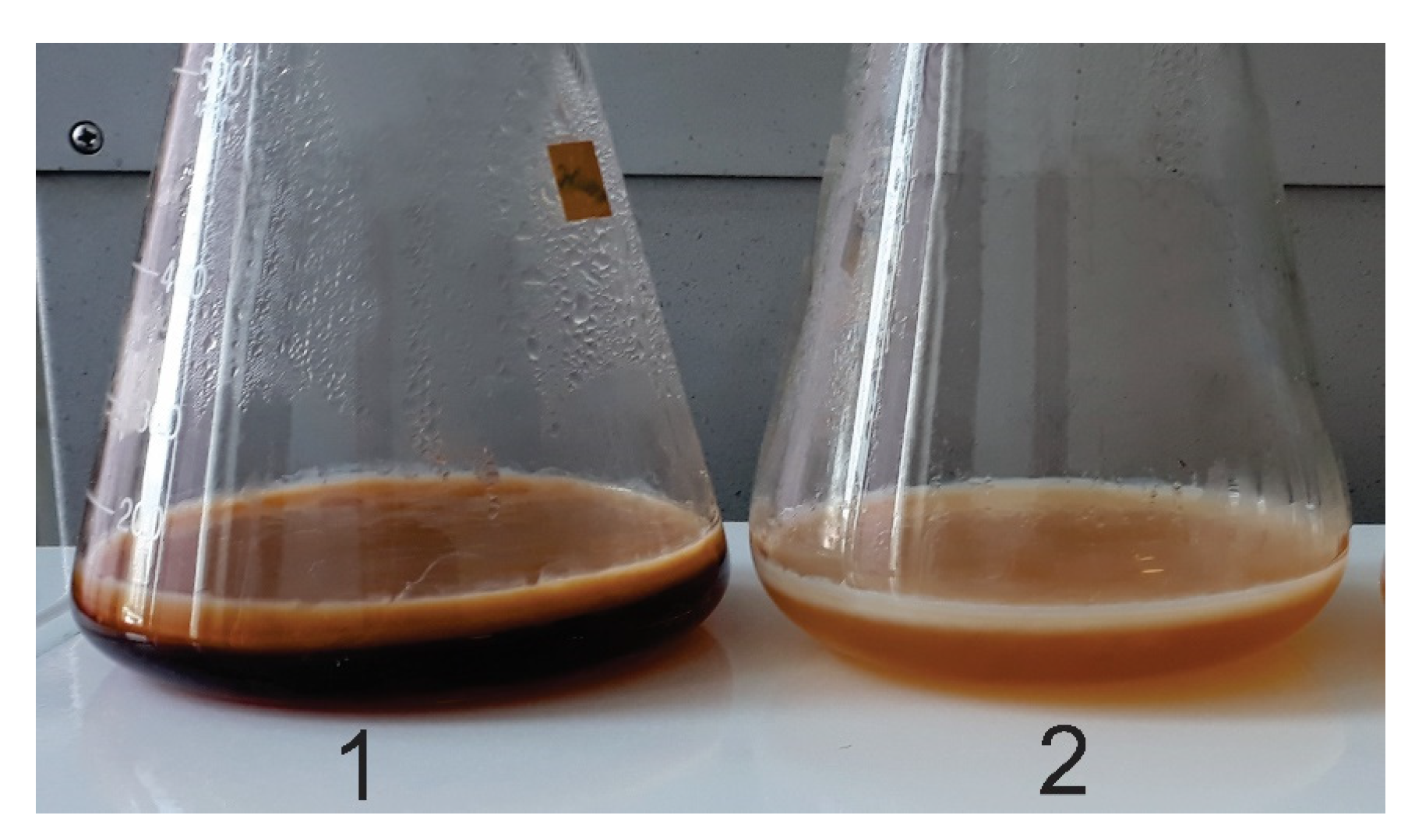

3.3. Use of Brewing Waste as a Cheap and Accessible Medium for Obtaining BC

3.4. Co-Cultivation of K. xylinus MS2530 Strain with Yeast Strains

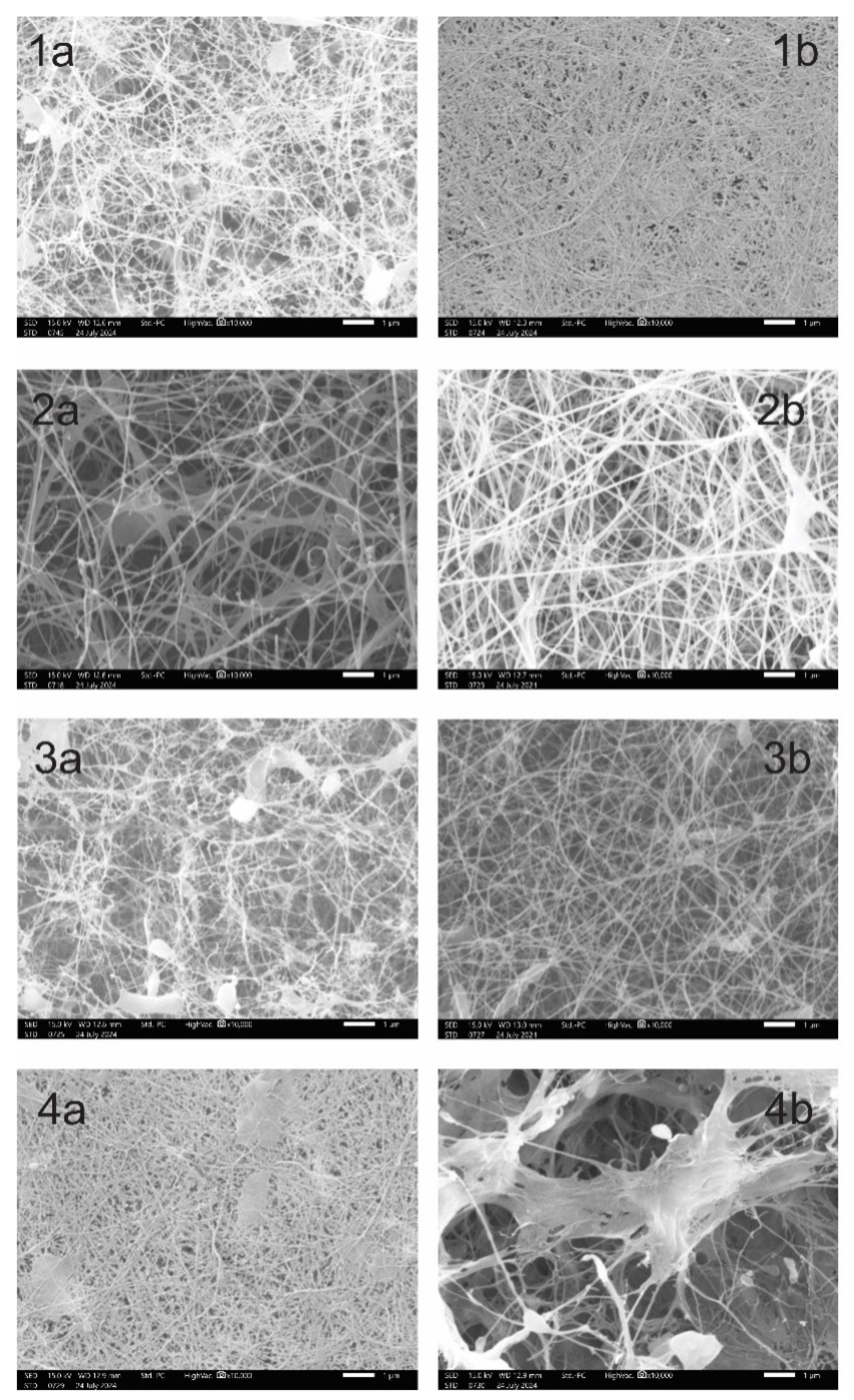

3.5. Study of the Structure and Properties of BC Obtained by the K.xylinus MS2530 Strain, as well as by Co-fermentation of K.xylinus MS2530 with Yeast Strains

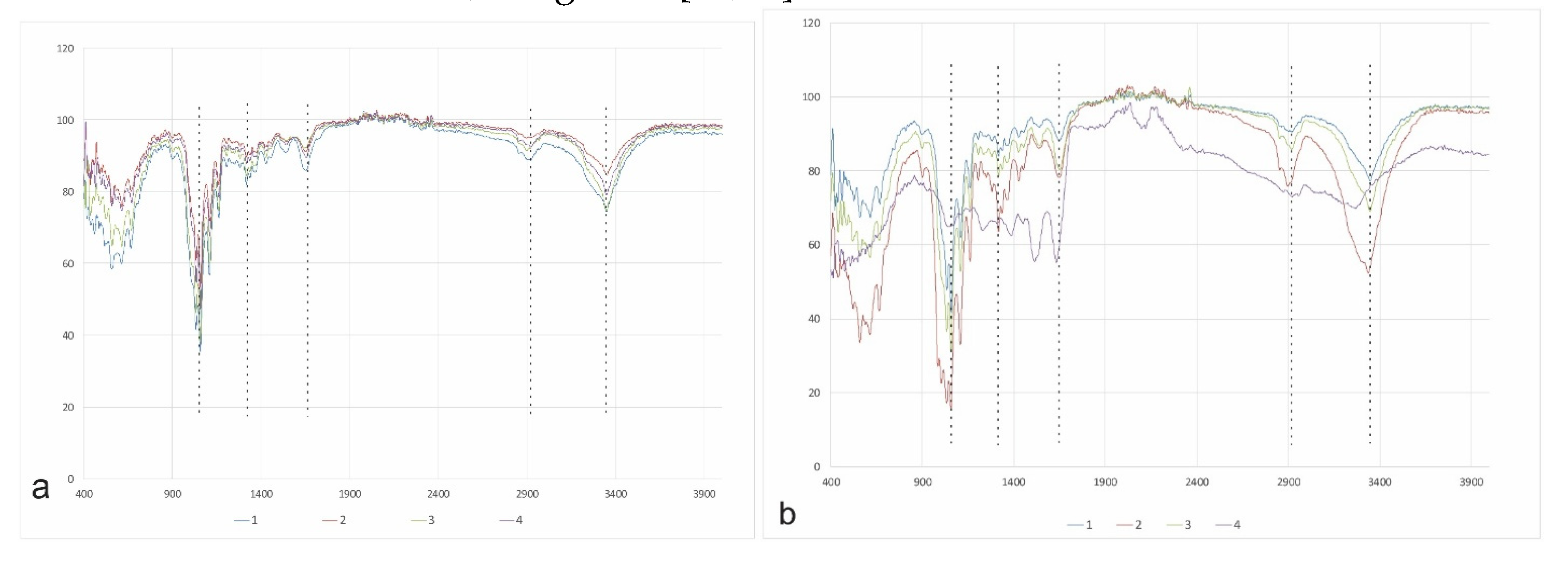

3.6. Determination of the chemical structure of synthesized BC films using FT-IR spectroscopy

3.7. Physicomechanical Parameters of BC Obtained from the K.xylinusMS2530 Producer Strain

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abral, H.; Pratama, A.B.; Handayani, D.; Mahardika, M.; Aminah, I.; Sandrawati, N.; Sugiarti, E.; Muslimin, A.N.; Sapuan, S.M.; Ilyas, R.A. Antimicrobial Edible Film Prepared from Bacterial Cellulose Nanofibers/Starch/Chitosan for a Food Packaging Alternative. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2021, 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abral, H.; Chairani, M.K.; Rizki, M.D.; Mahardika, M.; Handayani, D.; Sugiarti, E.; Muslimin, A.N.; Sapuan, S.M.; Ilyas, R.A. Characterization of compressed bacterial cellulose nanopaper film after exposure to dry and humid conditions. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 11, 896–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, A.; Kumar, K.D.; Kumar, R. In vitro degradation and antibacterial activity of bacterial cellulose deposited flax fabric reinforced with polylactic acid and polyhydroxybutyrate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 266, 131199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjay, M.R.; Siengchin, S. Exploring the applicability of natural fibers for the development of biocomposites. Express Polym. Lett. 2021, 15, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azman, M.A.; Asyraf, M.R.M.; Khalina, A.; Petru˚, M.; Ruzaidi, C.M.; Sapuan, S.M.; Wan Nik, W.B.; Ishak, M.R.; Ilyas, R.A.; Suriani, M.J. Natural Fiber Reinforced Composite Material for Product Design: A Short Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadier, A.; Ilyas, R.A.; Huzaifah, M.R.M.; Harihastuti, N.; Sapuan, S.M.; Harussani, M.M.; Azlin, M.N.M.; Yuliasni, R.; Ibrahim, R.; Atikah, M.S.N.; et al. Use of industrial wastes as sustainable nutrient sources for bacterial cellulose (BC) production: Mechanism, advances, and future perspectives. Polymers 2021, 13, 3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisyah, H.A.; Paridah, M.T.; Sapuan, S.M.; Ilyas, R.A.; Khalina, A.; Nurazzi, N.M.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, C.H. A Comprehensive Review on Advanced Sustainable Woven Natural Fibre Polymer Composites. Polymers 2021, 13, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurazzi, N.M.; Asyraf, M.R.M.; Khalina, A.; Abdullah, N.; Aisyah, H.A.; Rafiqah, S.A.; Sabaruddin, F.A.; Kamarudin, S.H.; Norrrahim, M.N.F.; Ilyas, R.A.; et al. A Review on Natural Fiber Reinforced Polymer Composite for Bullet Proof and Ballistic Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsubari, S.; Zuhri, M.Y.M.; Sapuan, S.M.; Ishak, M.R.; Ilyas, R.A.; Asyraf, M.R.M. Potential of natural fiber reinforced polymer composites in sandwich structures: A review on its mechanical properties. Polymers 2021, 13, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Liu, Z.; Shen, R.; Chen, S.; Yang, X. Bacterial cellulose in food industry: Current research and future prospects. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 158, 1007–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastav, P.; Pramanik, S.; Vaidya, G.; Abdelgawad, M.A.; Ghoneim, M.M. , Singh, A.; Abualsoud, B.M.; Amaral, L.S.; Abourehab, M.A.S.Bacterial cellulose as a potential biopolymer in biomedical applications: A state-of-the-art review. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 10, 3199–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Ding, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Y.; Fan, M.; Yang, J.; Sun, D. Bacterial cellulose-based biomaterials: From fabrication to application. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 278, Article–118995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meftahi, A.; Samyn, P.; Geravand, S.A.; Khajavi, R.; Alibkhshi, S.; Bechelany, M.; Barhoum, A. Nanocelluloses as skin biocompatible materials for skincare, cosmetics, and healthcare: Formulations, regulations, and emerging applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 278, Article–118956.7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishparenok, A.N.; Furman, V.V; Dobryakova, N.V.; Zhdanov, D.D. Protein Immobilization on Bacterial Cellulose for Biomedical Application. Polymers 2024, 16, 2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, L.; Su, T. An Eco-Friendly Adsorbent Based on Bacterial Cellulose and Vermiculite Composite for Efficient Removal of Methylene Blue and Sulfanilamide. Polymers 2023, 15, 2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, L.F.A.; Mouro, C.; Riool, M.; Gouveia, I.C. Antimicrobial food packaging based on prodigiosin-incorporated double layered bacterial cellulose and chitosan composites. Polymers 2022, 14, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyagi, N.; Suresh, S. Production of cellulose from sugarcane molasses using Gluconacetobacter intermedius SNT-1: Optimization & characterization. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, J.; Morena, A.G.; Valenzuela, S.V.; Pastor, F.I.J.; Díaz, P.; Martínez, J. Microbial Cellulose from a Komagataeibacter intermedius Strain Isolated from Commercial Wine Vinegar. J. Polym. Environ. 2019, 27, 956–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul-Islam, M.; Khan, T.; Park, J.K. Water holding and release properties of bacterial cellulose obtained by in situ and ex situ modification. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 88, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volova, T.G.; Prudnikova, S.V.; Kiselev, E.G.; Nemtsev, I.V.; Vasiliev, A.D.; Kuzmin, A.P.; Shishatskaya, E.I. Bacterial Cellulose (BC) and BC Composites: Production and Properties. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revin, V.V.; Liyaskina, E.V.; Parchaykina, M.V.; Kuzmenko, T.P.; Kurgaeva, I.V.; Revin, V.D.; Ullah, M.W. Bacterial Cellulose-Based Polymer Nanocomposites: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaczmarek, M.; Jedrzejczak-Krzepkowska, M.; Ludwicka, K. Comparative Analysis of Bacterial Cellulose Membranes Synthesized by Chosen Komagataeibacter Strains and Their Application Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Wang, L.; Deng, Y.; Wei, Q. Research progress of the biosynthetic strains and pathways of bacterial cellulose. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 49, kuab071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revin, V.V.; Liyas’kina, E.V.; Sapunova, N.B.; Bogatyreva, A.O. Isolation and characterization of the strains producing bacterial cellulose. Microbiology 2020, 14, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeredo, H.M.C.; Barud, H.; Farinas, CS.; Vasconcellos, V.M.; Claro, A.M. Bacterial Cellulose as a Raw Material for Food and Food Packaging Applications. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguluri, K.; La China, S.; Brugnoli, M.; Cassanelli, S.; Gullo, M. Better under stress: Improving bacterial cellulose production by Komagataeibacter xylinus K2G30 (UMCC 2756) using adaptive laboratory evolution. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 994097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimmer, M.; Mientus, M.; Klingl, A.; Ehrenreich, A.; Liebl, W. The Roles of the Various Cellulose Biosynthesis Operons in Komagataeibacter hansenii ATCC 23769. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e02460–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Walker, K.T.; Ledesma-Amaro, R.; Ellis, T. Engineering Bacterial Cellulose by Synthetic Biology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.F.S.; Almeida, F.C.G.; Vinhas, G.M.; Sarubbo, L.A. Production of bacterial cellulose by Gluconacetobacter hansenii using corn steep liquor as nutrient sources. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez-Riaño, M.; Bojacá, V. Production of bacterial cellulose from alternative low-cost substrates. Cellulose 2017, 24, 2677–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgieva, S.; Jančič, U.; Cepec, E.; Trček, J. Production efficiency and properties of bacterial cellulose membranes in a novel grape pomace hydrolysate by Komagataeibacter melomenusus AV436T and Komagataeibacter xylinus LMG 1518. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 244, 125368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; Gao, Y.; He, W.; Hu, H.; Tian, M.; Wang, K.; Pan, S. Production of nano bacterial cellulose from beverage industrial waste of citrus peel and pomace using Komagataeibacter xylinus. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 151, 1068–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzyol, H.K.; Saçan, M.T. Bacterial cellulose production by Komagataeibacter hansenii using algae-based glucose. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 11154–11162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revin, V.; Liyaskina, E.; Nazarkina, M.; Bogatyreva, A.; Shchankin, M. Cost-effective production of bacterial cellulose using acidic food industry by-products. Brazilian J. Microbiol. 2018, 49, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vazquez, A.; Foresti, M.L.; Cerrutti, P.; Galvagno, M. Bacterial Cellulose from Simple and Low Cost Production Media by Gluconacetobacter xylinus. J. Polym. Environ. 2013, 21, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongruang, S. Bacterial cellulose production by Acetobacter xylinum strains from agricultural waste products. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2008, 148, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D. , Lopez-Sanchez, P.; Li, R.; Li, Z. Production of bacterial cellulose by Gluconacetobacter hansenii CGMCC 3917 using only waste beer yeast as nutrient source. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 151, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsouko, E.; Kourmentza, C.; Ladakis, D.; Kopsahelis, N. ; Mandala, J; Papanikolaou, S.; Paloukis, F.; Alves, V.; Koutinas, A. Bacterial cellulose production from industrial waste and by-product streams. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 14832–14849. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. , Wang, L.; Hua, J.; Jia, S.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H. Production of nanobacterial cellulose from waste water of candied jujube-processing industry using Acetobacter xylinum. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 120, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Yang, X-Y. ; Xiong, L.; Guo H-J.; Luo, J.; Wang, B.; Zhang, H-R.; Lin, X-Q.; Chen X-D. Evaluating the possibility of using acetone-butanol-ethanol (ABE) fermentation wastewater for bacterial cellulose production by Gluconacetobacter xylinus. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 60, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, F.P.; Silva, N.H.C.S.; Trovatti, E.; Serafim, L.S. Production of bacterial cellulose by Gluconacetobacter sacchari using dry olive mill residue. Biomass. Bioenerg. 2013, 55, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, I.A.A.; Pedro, A.C.; Ribeiro, V.R.; Bortolini, D.G. , Ozaki, M.S.C.; Maciel, G.M.; Haminiuk, C.W.I. Bacterial cellulose: From production optimization to new applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 2598–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhania, R.R.; Patel, A.K. ; Tseng, Y-S.; Kumar, V.; Chen, C-W.; Haldar, D.; Saini, J.K.; Dong, C.D. Developments in bioprocess for bacterial cellulose production. Bioresource Technology, 2022, 344(Pt B), Article 126343.

- Akintunde, M.O.; Adebayo-Tayo, B.C.; Ishola, M.M.; Zamani, A.; Horvath, I.S. Bacterial cellulose production from agricultural residues by two komagataeibacter sp. strains. Bioengineered, 2022, 13, 10010–10025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.P.; Huang, S.H.; Ting, Y.; Hsu, H.Y.; Cheng, K.C. Evaluation of detoxified sugarcane bagasse hydrolysate by atmospheric cold plasma for bacterial cellulose production. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 204, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, K.; Papapostolou, H.; Alexandri, M.; Vlysidis, A.; Myrtsi, E.D.; Ladakis, D.; Pateraki, C; Haroutounian S. A.; Koutinas A. Integrated biorefinery development using winery waste streams for the production of bacterial cellulose, succinic acid and value-added fractions. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 343, Article–125989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, G.; Luo, M.; Huang, C.; Guo, H.; Chen, X.; Xiong, L.; Wang, B.; Lin, X.; Peng, F.; Chen, X. Comparison of bacterial cellulose production by Gluconacetobacter xylinus on bagasse acid and enzymatic hydrolysates. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134, 45066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.M.; Liu, R.H. Cost-effective production of bacterial cellulose in static cultures using distillery wastewater. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2013, 115, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, F.; Guo, X.; Zhang, S.; Han, S.F.; Yang, G.; Jönsson, L.J. Bacterial cellulose production from cotton-based waste textiles: Enzymatic saccharification enhanced by ionic liquid pretreatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 104, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Xia, J.; Wang, J.; Yan, X.; Wang, C.; Lei, T.; Xian, M.; Zhang, H. Production of bacterial cellulose using polysaccharide fermentation wastewater as inexpensive nutrient sources. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2018, 32, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huige, N. Brewery by-products and effluents. In: Handbook of brewing. Stewart GG, Priest FG, eds. 2nd edition. CRC Press, Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis Group, 2006; pp. 656–716.

- Kerby, C.; Vriesekoop, F. An overview of the utilisation of brewery by-products as generated by british craft breweries. Beverages 2017, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podpora, B.; Swiderski, F.; Sadowska. A.; Rakovska, R.; Wasiak-Zys, G. Spent brewer's yeast extracts as a new component of functional food. Czech J. Food Sci. 2016, 34, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathias, T.R.S.; Alexandre, V.M.F.; Cammarota, M.C.; Mello, P.P.M.; Sérvulo, E.F.C. Characterization and determination of brewer's solid wastes composition. JIB 2015, 121, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yan, H.H.; Qin, C.Q. ։ Liang, Y.X.։ Ren, D.F. Accumulation of astaxanthin by co-fermentation of Spirulina platensis and recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae․ Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2022, 194, 988–999. 194,.

- Rémi, H.; Michael, S. An artificial coculture fermentation system for industrial propanol production. FEMS Microbes 2022, 3, xtac013. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Catchmark, J.M. Enhanced mechanical properties of bacterial cellulose nanocomposites produced by co-culturing Gluconacetobacter hansenii and Escherichia coli under static conditions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 219, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H. , Catchmark, J. M., Demirci, A. Co-culture fermentation on the production of bacterial cellulose nanocomposite produced by Komagataeibacter hansenii. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2021, 100028. [Google Scholar]

- Freilich, S.; Zarecki, R.; Eilam, O.; Segal, E.S.; Henry, C.S.; Kupiec, M.; Gophna, U.; Sharan, R.; Ruppin, E. Competitive and cooperative metabolic interactions in bacterial communities. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seto, A.; Saito, Y.; Matsushige, M.; Kobayashi, H.; Sasaki, Y.; Tonouchi, N.; Tsuchida, T.; Yoshinaga, F.; Ueda, K.; Beppu, T. Effective cellulose production by a coculture of Gluconacetobacter xylinus and Lactobacillus mali. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 73, 915–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.K. , Nguyen, P.B., Nguyen, H.T.; Le, P.H. Screening the optimal ratio of symbiosis between isolated yeast and acetic acid bacteria strain from traditional kombucha for high-level production of glucuronic acid. LWT 2015, 64, 1149–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, C.; Bhardwaj, N.K. Biotransformation of fermented black tea into bacterial nanocellulose via symbiotic interplay of microorganisms. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 132, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Mu, J.; Ma, Q.; Lu, X. Symbiosis of acetic acid bacteria and yeast isolated from black tea fungus mimicking the kombucha environment in bacterial cellulose synthesis. Int. Food Res. J. 2023, 30, 1504–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacek, P.; Soares da Silva, F.A.G.; Dourado, F.; Bielecki, S.; Gama, M. Optimization and characterization of bacterial nanocellulose produced by Komagataeibacter rhaeticus K3. Carbohydr. Polym. Appl. 2021, 2, 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, F.; Ma, K.; Feng, Y.; Zheng, J.; Mao, D.; Yang, X. Bacterial cellulose production by Acetobacter xylinum ATCC 23767 using tobacco waste extract as culture medium. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 274, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.M.; Gu, J.; Kafle, K.; Catchmark, J.; Kim, S.H. Cellulose produced by Gluconacetobacter xylinus strains ATCC 53524 and ATCC 23768: Pellicle formation, post-synthesis aggregation and fiber density. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 133, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. , Li C. , Tang Y.; Constructing bacterial cellulose and its composites: regulating treatments towards applications. Cellulose 2024, 31, 7793–7817. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.; Ge1, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xia, X.; Zhao, B.; Dong, M. Production and characterization of bacterial cellulose from kombucha-fermented soy whey. FPPN 2024, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhantlessova, S.; Savitskaya, I.; Kistaubayeva, A.; Ignatova, L.; Talipova, A.; Pogrebnjak, A.; Digel, I. Advanced “Green” Prebiotic Composite of Bacterial Cellulose/Pullulan Based on Synthetic Biology-Powered Microbial Coculture Strategy. Polymers 2022, 14, 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J. , Zheng, S., Zhang, Z., Yang, F., Ma, K., Feng, Y., et al. Bacterial cellulose production by Acetobacter xylinum ATCC 23767 using tobacco waste extract as culture medium. Bioresource Technology 2019, 274, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Strains | Yield BC on HS(g/l) |

g/L· Day -1 |

Yield BC on BSY (g/l) |

g/L ·Day-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K. xylinusMS2530 | 12.51 ± 0.2 | 1,79 | 13.1 ± 0.26 | 1,87 |

| K.xylinusMS2530+Kluyveromyces marxianus MDC 10081 | 20.9 ± 0.3 | 2,97 | 26.4 ± 0.35 | 3,77 |

| K. xylinusMS2530+Pichia fermentans MDC10169 | 18.9 ± 0.13 | 2.69 | 23.0 ± 0.24 | 3,27 |

| K. xylinusMS2530+Pichiya pastoris MDC 10178 | 17.0 ± 0.21 | 2,42 | 22.2 ± 0.16 | 3,16 |

| Properties | BC hydrogel | Freeze-dried BC |

|---|---|---|

| Water-holding capacity (%) | 99.9± 0.3 | 198.6 ± 0.13 |

| Tensile strength (MPa) | 0,69±0,31 | 0.1± 0.1 |

| Elongation (%) | 4,95±1,39 | 3.7±0.2 |

| Young’s modulus (GPa) | 9,86±0,29 | 45,7±1,02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).