1. Introduction

Critical thinking (CT) is an active metacognitive process that, through the concurrence of certain skills, dispositions and knowledge, helps us make a informed judgment oriented towards action or problem resolution (Morancho and Rodríguez, 2020) and is a requirement necessary to function adequately in our globalized, contradictory and hyper-informed society (Morin, 2004; Wolton 2010; UNESCO, 2010, 2015, 2019, 2021a, 2021b), with a complexity that leads to a feeling of vertigo and imposing new skills on people (Saiz and Rivas, 2023). Sánchez et al. (2019) propose the following options when understanding CT: (a) ability to express a personal position; (b) express a founded point of view; (c) make a judgment; (d) thinking ability that is part of a more complex cognitive process; (e) reflection based on knowledge, analysis, understanding and processing of information. However, in the context of psychosocial intervention, the proposal of Bezanilla et al., (2018) may be more comprehensive, indicating that critical thinking is oriented towards understanding problems, resolving them, evaluating alternatives for decision-making. of decisions. In this sense, it means understanding to solve.

We speak of critical thinking as a competence, because it seeks to go beyond the mere mastery of the skills necessary to develop it, inexorably linking the critical dimension with the need to act in the world in which we operate (Jiménez, 2024). Even more so considering the primary objective of different university degrees that seek to promote positive change in people and society, such as social education, teaching or social communication. With this, it is not enough to know how to criticize, but to be critical from a commitment to good-being (García et al., 2024), seeking the truth (Liu, 2022) and addressing the fundamental issues that fully touch our existence such as responsibility, tolerance, commitment, and the value of family (Walker and LeBoeuf, 2022).

Critical thinking, at least in education for social change, goes much further than the mastery of certain cognitive skills, requiring social competencies that enable the solution of problems in a concrete and real space-time context (Halpern, 1998). It is not enough to recognize its importance, but to have the ability to put it into practice (Sánchez et al., 2019).

From different national and international levels, it is urged to train people in the development of said competence (UNESCO, 1998, 2009; International Economic Forum, 2020); Education, different types of companies and the labor market give it increasing importance (Dwyer, 2023; Halpern and Dunn 2021; Saiz and Rivas, 2023). These recommendations are considered in formal teaching, materializing in the different institutional ideologies. In this sense, the university context is ideal to promote critical thinking, with the teacher being an essential element in promoting the development of said thinking (Bezanilla et al. 2018; Tamayo et al., 2015), but as a requirement competence to respond to social demands and not only as an isolated training action disconnected from social reality, avoiding the lack of correspondence that is often detected between what is considered necessary and what is actually realized in practice. (Febres et al., 2017; Pithers and Soden, 2000).

There are many authors, from different fields, who have approached the concept of critical thinking, with as many definitions appearing as there are authors, which reflects, on the one hand, the growing interest in research on the subject and, on the other, the disparity of proposals that appear when defining it (Ennis, 1987; Lipman, 2006; Facione, 1990) among many others). From our point of view, it seems reasonable to think that talking about criticism in fields not linked to psychosocial intervention is not the same as those that are characterized by this. In this sense, responsibility towards social change does not seem qualitatively similar when one wants to identify errors in discourse than when one plans to propose factual alternatives to what exists to promote the promotion of the good being of people in society. There is no doubt that our current society needs people who understand reality from a competency, narrative approach embedded in one's own life story with others in society (García et al., 2023). This call for civic and social responsibility is made from different levels, higher education being one of them. Training for training's sake is no longer enough, this fact being legitimate, but rather its realization in the socio-community reality appears as the basis that justifies its existence. Developing social policies that promote the well-being of people in society is not developing ideas, but actions based on those ideas; It requires understanding what to improve, how to achieve it and why it is necessary to carry it out (Saiz and Rivas, 2023).

This necessarily means not separating critical competence and its teaching, not with action since then it would not be competence (Jiménez, 2024), but with ethics since we cannot talk about critical educational intervention without reflecting on ethics (Pantoja, 2012).

Taking into account that critical thinking, as the ability to glimpse what is necessary from what is residual and anecdotal in our society (Facione, 1990; Nieto, Sáiz and Orgaz, 2009; UNESCO, 2021a; 2021b) is an essential element that is valued very positively by university students of the degrees referred to above (Garcia et al. 2021) since this fact may be influenced by the area study or research (Altuve, 2020), with this research we seek to delve into the beliefs that a group of university students from the degree of social education, teaching, sports sciences and educational psychology have about critical thinking as a necessary competence for change, and its connection with elements scarcely covered in literature such as ethics. And this, being aware that there are studies such as those by Arum and Roska (2011) that consider that university students in their first years do not have sufficient tools or maturity to learn critical competence; that this competence improves with age (Huber and Kuncel, 2016), although they recognize its usefulness (Garcia et al. 2021, 2024). And for this research, we will understand beliefs as the set of knowledge, values and ideas that people use to guide our lives and actions with a strong internal consistency (Rodríguez and González, 1995), in such a way that the lines of research on this topic have indicated that people do not use scientific theories when solving practical problems (Rodríguez and Correa, 1999), but rather a set of more or less consistent beliefs that contingently influence the actions of an individual.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Sample Composition

With the aim of analyzing the proposed research topic, we focus on the description of a group of undergraduate and postgraduate students of degrees related to psychosocial and socio-educational intervention in Spain; Specifically, a non-probabilistic sample of 100 subjects was used, 50 men and 50 women, from degrees in Social Education, Psychology, Teaching and aged between 18 and 35 years (M=24.5; SD = 3. 41) and who are studying the Master of Communication and Visual Education or the Master in Teacher Training for Secondary, Baccalaureate, Vocational Training and School of Languages, or some of the degrees indicated and offered by the University of Huelva (Spain); Specifically, 43 respondents are studying undergraduate degrees and 57 postgraduate students.

The design used is mixed with a descriptive-correlational part and a qualitative content analysis part insofar as it has been considered the option that can dissect and describe the beliefs of the subjects subject to intervention with more depth and richness. Along these lines, a self-developed questionnaire has been used as information collecting instruments to know the beliefs held by the investigated population; In turn, this information has been complemented and expanded with two focus groups in which the knowledge of opinions and beliefs about critical competence and the importance of ethics as a regulatory element of criticism has been deepened. In more detail we specify it below:

2.2. Instrument

2.2.1. Critical Competence Beliefs Questionnaire

With the objective of analyzing the beliefs and opinions of the investigated subjects, a self-developed questionnaire used in previous research (García et al., 2024) was used, validated by the system of judges, and which reaches an alpha of 0.7 and which, given the complexity of the construct analyzed, we consider acceptable for the present investigation. However, considering the nature of the design used as well as the research objective, this condition takes back seat considering that we are interested in knowing a group case in depth; an object-context of study that allows offering ideas that contribute to better knowledge and improvement of the phenomenon investigated (Stake, 2005). The JASP 0.19.2 statistical package was used for analysis.

The issues raised are detailed below:

Table 1.

Critical Competence Beliefs Questionnaire.

Table 1.

Critical Competence Beliefs Questionnaire.

| Questionnaire about beliefs about critical competence in the initial training of degrees linked to social intervention |

|

I consider that my level of knowledge of critical thinking is

I think the university favors critical thinking

I believe that today's society places a lot of importance on critical thinking.

The subjects taken at the university promote critical thinking

The situation of today's society requires people with critical thinking

I know how to discriminate the essential from the circumstantial

I consider that critical thinking is essential for my life

I believe that knowledge is necessary to be a good critical thinker.

Critical thinking is something you are born with

I think I have good critical competence

Empathy is necessary for critical thinking

Critical thinking requires greater effort for the person, which sometimes does not pay off.

I have taken or am taking specific training courses in critical thinking

Having critical thinking makes you popular among others

Critical thinking is an attitude of criticizing everything that is considered |

|

The following sociodemographic variables were added to these questions: sex, age, employment status, and studies (undergraduate - postgraduate).

2.2.3. Focus Group

To complete this information and saturate the data, two focus groups were established; one composed of 10 people (7 women and 3 men) and the second with 9 (6 men and 3 women), with a duration of 40 minutes. In these focus groups, different issues related to critical and ethical competence in the professional practice of psychosocial intervention were discussed (

Table 2). The transcription of the information was carried out, as well as the procedure of identifying units and propositions with significance in the proposed theme, coding of said units and propositions, to group them according to thematic nuclei that allow the construction of categories that enable their own analysis. of structured content analysis. For this, the ATLAS.ti.7.5 software was used.

2.2. Procedure

Regarding the procedure, the selection of the degrees and the academic year were carried out intentionally, administering the online self-report prepared had hoc and used in part in previous research (Garcia et al., 2024). The questionnaire took approximately 10 minutes to complete once written informed consent was obtained from all students. Subsequently, two focus groups were held with a selection of students who participated in the survey and who voluntarily wanted to take it. The session was recorded and transcribed to perform content analysis based on established categories. The duration of the focus groups was 40 minutes.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Study

3.1.1. Descriptive Statistics and Non-Parametric Tests

90% of the students surveyed believe that they have a high level of knowledge about CT, with 80% of men and 70% of women considering CT as essential and important for their lives. However, 42% of women are hesitant when considering that they have critical competence; that is, to act critically, compared to 28% of men. 70% of the sample indicates that they have not taken any training course on CT.

Regarding the role of the University in promoting such thinking, 44% of men say they agree compared to 76% of women, in this sense the difference being significantly positive in favor of the latter; However, 68% of both sexes believe that society does not support CT.

Focusing on the more structural aspects of CT, 68% of boys compared to 52% of girls consider that they know how to discriminate what is important from what is circumstantial in situations. Curiously, only 20% of men and 36% of women do not give importance to knowledge as one of the fundamental elements of good CT. In turn, regarding empathy as a dispositional component, approximately 60% of the sample do give it importance to develop a good CT compared to 30% who consider that it is not necessary.

Finally, practically 75% of the entire sample believes that developing a CT involves a great effort for the person that sometimes does not pay off and, furthermore, does not make the person who acts like this popular (60% of the sample).

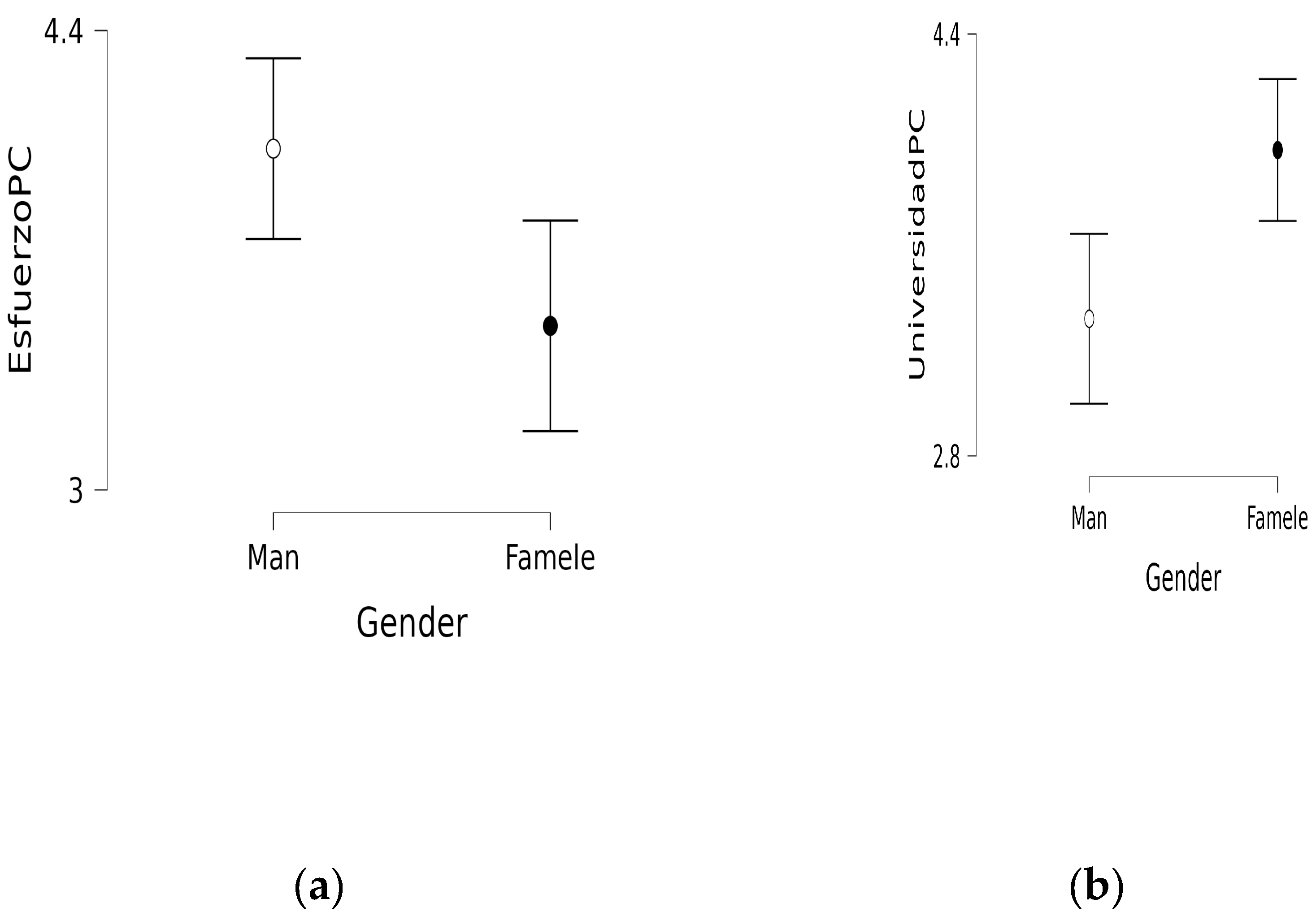

Regarding the variables “age” and “graduate-postgraduate”, no significant differences are obtained with any of the variables under study. Significant differences are obtained when we assess the differences between sex. Men believe that CT involves greater effort, while women believe that the University favors CT more than men (

table 4 and

Figure 1)

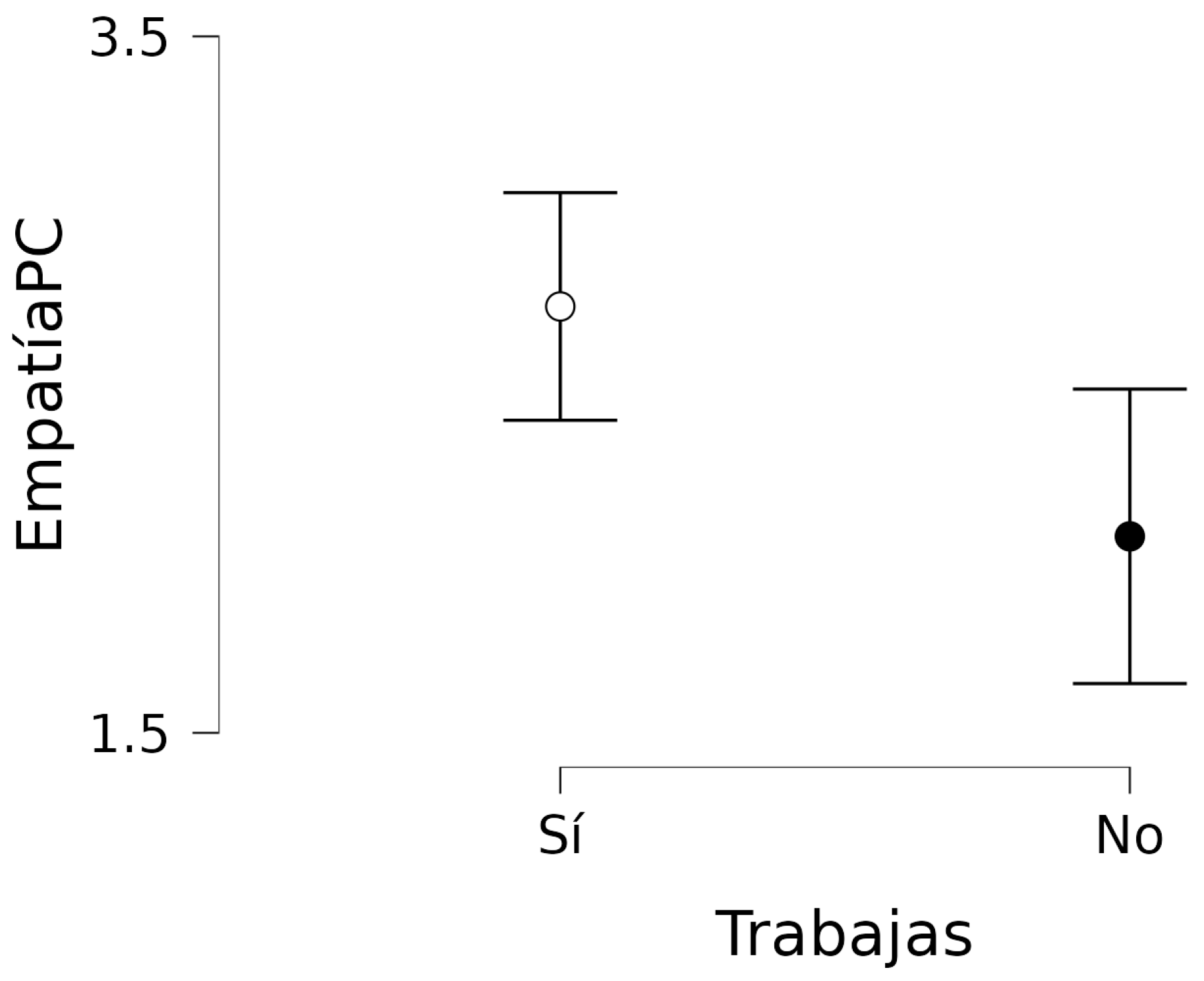

Finally, respondents who are working consider that empathy is a fundamental element of CT,

unlike those who are not working.

Table 5.

Independent Samples T-test.

Table 5.

Independent Samples T-test.

| |

IN |

df |

p |

| Empathy |

1364.500 |

|

0.024 |

3.1.3. Correlations

Regarding the bivariate correlations, a significant correlation occurs at (p=<.001), (p=<0.01) and (p=<0.05) between the following study variables: Those who consider that they have a good level of knowledge of CT consider that they know how to discriminate the essential from the circumstantial (r=0.397 p=<0.001); valuing CT as something essential for their own lives (r=0.428 p=<0.001), although they also consider that it requires greater effort for people (r=0.219 p=<0.028) and also do not consider empathy to be a necessary element to develop critical thinking in their own professional role (r=-0.254 p=<0.011).

On the other hand, those who consider that the university favors CT believe that current society gives a lot of importance to this thought (r=0.300 p=<0.002), carrying out specific training courses on the topic (r=0.235 p=<0.019), obtaining a very significant correlation between believing that one has a good knowledge of CT and having taken specific CT courses (r=0.324 p=0.001), and believe that one has good critical competence by having taken specific training courses on the topic (r=0.338 p=<0.001).

Finally, we highlight the correlation that occurs between thinking that one is born with CT and the fact of having good popularity (r=0.329 p=<0.001), and consider that in addition to the fact that CT is something innate, it consists of criticizing everything with which one does not agree (r=0410 p=<0.001), this last element reaching a very significant correlation with having great popularity (r=0.325 p=<0.001).

Table 4.

Bivariate correlations.

Table 4.

Bivariate correlations.

| |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

| 1.Knowledge level |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2.University |

0.192

0.056 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3.Society |

0.006

0.950 |

0.300**

0.002 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4.Subjects |

0.227*

0.023 |

0.789***

<0.001 |

0.213*

0.033 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 5.Requirement |

0.134

0.184 |

0.303**

0.002 |

0.095

0.349 |

0.302**

0.002 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 6.Discriminate |

0.397***

<0.001 |

0.150

0.138 |

-0.028

0.784 |

0.122

0.226 |

0.157

0.118 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 7.Necessary |

0.428***

<0.001 |

0.141

0.161 |

-0.083

0.411 |

0.193

0.054 |

0.299**

0.002 |

0.374***

<0.001 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 8.Knowledge need |

0.118

0.242 |

0.155

0.124 |

0.171

0.090 |

0.251*

0.012 |

0.135

0.179 |

-0.033

0.748 |

0.151

0.134 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 9.Innate |

-0.042

0.677 |

-0.010

0.923 |

0.144

0.154 |

0.048

0.637 |

0.042

0.678 |

-0.185

0.066 |

0.006

0.954 |

0.215*

0.0032 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 10.Competence |

0.372***

<0.001 |

-0.004

0.972 |

0.016

0.878 |

0.025

0.802 |

0.110

0.276 |

0.420***

<0.001 |

0.572***

<0.001 |

0.178

0.076 |

0.089

0.377 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 11.Empathy |

-0.254*

0.011 |

0.117

0.247 |

0.250*

0.012 |

0.117

0.245 |

0.002

0.983 |

-0.110

0.274 |

-0.058

0.566 |

0.242*

0.015 |

0.196

0.051 |

-0.100

0.322 |

|

|

|

|

| 12.Effort |

0.219*

0.028 |

0.023

0.817 |

-0.053

0.598 |

-0.072

0.479 |

-0.031

0.758 |

0.247*

0.013 |

0.241*

0.016 |

-0.044

0.661 |

-0.146

0.147 |

0.219*

0.028 |

0.140

0.164 |

|

|

|

| 13.Courses |

0.250*

0.012 |

0.235*

0.019 |

0.146

0.149 |

0.233*

0.019 |

0.322**

0.001 |

-0.029

0.775 |

0.179

0.075 |

0.324**

0.001 |

0.250*

0.012 |

0.338***

<0.001 |

0.102

0.313 |

0.142

0.160 |

|

|

| 14.Popular |

-0.085

0.403 |

0.062

0.540 |

0.311**

0.002 |

0.033

0.745 |

0.031

0.760 |

-0.129

0.201 |

0.508

0.997 |

0.022

0.831 |

0.329***

<0.001 |

0.190

0.058 |

0.086

0.393 |

0.042

0.682 |

0.348***

<0.001 |

|

| 15.Criticizing |

0.022

0.826 |

-0.125

0.217 |

0.199*

0.047 |

-0.123

0.223 |

-0.041

0.682 |

-0.164

0.104 |

-0.078

0.440 |

0.186

0.064 |

0.410***

<0.001 |

0.200*

0.046 |

0.102

0.311 |

-0.037

0.711 |

0.310**

0.002 |

0.325***

<0.001 |

3.2. Qualitative Study

Below we will transcribe the results obtained in the focus groups taking into account that the identification code that accompanies each statement is interpreted by the initials of: Male or Female; age, working, graduate or postgraduate and group.

3.2.1. Defining Critical Thinking

To analyze this section, we follow the proposals of the great researchers on CT when defining its components. (Ennis, 1987; Epstein, 2006; Facione, 1990; Halpern, 2003) in skills and dispositions; although we consider the motivational contributions (Valenzuela et al., 2014).

The students participating in the focus groups consider that “CT is a fundamental attitude that all people must have in the face of the challenges of today's society” (F21G2); “it is a strategy that allows us to identify errors…” (M23G1), “… move forward and improve our society by identifying problems…” (M22WG1). “It's something that is talked about a lot today but that we don't really know in depth.” (F34WP2). When asked to be more specific, there is great difficulty in the two focus groups, expressing some general opinions: “Strategy to change things…” (M26PG2); “knowing how to reflect and realize the errors that exist in society” (F20WG1), “it is a way of facing the problems that appear in life” (F31PG2), “having an opinion about something and knowing how to defend it” (M23G1 ).

In the statements, the idea of CT as defending one's own opinions predominates. When this idea is questioned, both groups come up with alternatives such as “These are not just opinions since we must go one step further. It is necessary to know what one thinks; a minimum knowledge since many things can be said and few of them be true..." (M28WPG2), "but it is not enough to just know things, it is also necessary to defend it since there are people who know a lot and do nothing to change the situations... ” (M23G2), “it is necessary to analyze, understand, know and also convince, otherwise what we do is for nothing…” (F29WPD1), “...I also think it is necessary to say that a good critical thinker seeks and defends the truth. ” (F24G1)

3.2.2. Ethics for Positive Change

In the focus groups, the responses that have been given to CT have had a marked teleological character. The why of it has been more concerned than defining it. In this sense, when asked about the purpose of CT, the answers received are: “... improve the world” (M23G2), “defend justice” (M23G1), “... change the things we know that they are wrong or at least try” (M22WG1). Given this, the following question arises: is it possible that we know how to change things but that it is not convenient to do so? What do you think of this? “... I don't think we can afford to be cowards" (M20G2), “... we have to be professionals and improve society” (F22G1), “... injustices should not be allowed” (F22aG1). The following responses are also received: “I don't think it's as easy as wanting to do things. Even if you want to, you can't always…” (F35WPG1), “…many times it is the pressure of the work environment that prevents you from doing something. I have had experiences in this sense of wanting to change something and not being able to do so due to the climate itself. It is not that easy many times” (M30WPG2), “for me, the automatic acting in which we are often immersed is what prevents us from acting critically” (M22G2).

When asked if anything is worth it to change things, the answers go along the following lines: “...In our way of understanding work, not everything is worth it; It is necessary to start from values, respect for the other person, with a highly developed empathetic attitude, with sincerity and knowing well what you can do and say depending on who you are with and at the moment” (F27WG1).

4. Discussion

The training of future professionals in socio-educational and psychosocial intervention requires specific, and not just transversal, training programs in CT, following the recommendations of the different institutions and organizations competent in the matter (UNESCO, 1998, 2009, 2010, 2015, 2019, 2021a, 2021b). The importance that is being given to CT is indisputable (Jiménez, 2023; Saiz and Rivas, 2023); In this sense, the sample is consistent with this trend, giving a very high assessment of the importance of CT for their lives as professionals of socio-educational and psychosocial intervention, although it does not reach 100% of the sample. However, the knowledge of what it means and what it entails is much smaller, and the responsibility when it comes to training in this line is practically anecdotal (Bejarano et al. 2014). Even regarding the question of whether respondents considered themselves to have adequate CT skills, no significant differences were observed between younger and older respondents. They do value critical thinking as a need for training; These results coincide with those obtained by Díaz et al. (2019), however there is no interest in training in this regard. Regarding the differences found based on sex, even though they are different research groups, there is a similarity with another research (García et al. 2024). In both, women consider that universities develop CT contrary to the smaller number of men surveyed who believe in this; but, curiously, they consider that it requires less effort when it comes to carrying it out than men; However, the results achieved could be due to the social influences of upbringing and the differentiated contextual development that the participants present (Escurra, et al., 2008).

Arum and Roska (2011) consider that university students in their first years do not have sufficient tools or maturity to learn critical competence; that this competence improves with age (Huber and Kuncel, 2016), although they recognize its usefulness (Garcia et al. 2021, 2024). The data indicates that the academic curriculum offered does not adequately develop CT. Obviously, there are studies in which significant differences have been observed in relation to CT in first- and third-year students; However, these differences may have been mediated by contextual variables (Roohr et al. 2019).

Although the students show some initial difficulty when correctly defining what TC is, confusing it with mere opinions or mere attitudes of courage, they are later able to reach conclusions more in line with what research on the topic is dealing with. ; That is, critical competence is knowing how to argue, analyze, corroborate, understand, what appears before oneself. You must be motivated to do it (Valenzuela et al., 2014). It is necessary to know to make criticism (Morancho and Rodríguez, 2020), but a way of understanding ethics is also necessary (García et al., 2024), as is the case of empathy, this data being much more significant in the subjects analyzed that are working than those that are not. Ethics is a central element for them and even more so in future professionals of socio-educational and psychosocial intervention (Pantoja, 20129). Likewise, a more complex vision of critical competence is shown in older people than in younger ones; this has been especially significant in focus groups opinions emerging that warn of the difficulty; Furthermore, this is a fact also corroborated in other similar investigations (García et al. 2021, 2024).

5. Conclusions

We find especially interesting the importance of the ethical component in critical competence in psychosocial and socio-educational intervention professionals, establishing an inseparable relationship between criticism for change and ethics that always respect fundamental principles of respect for what it means. Another above any confrontation. This aspect means defending a transversality of certain components that define the critical work of these professionals while at the same time entails a review when it comes to explaining the ethical dimension as a necessary element when understanding critical competence. Parallel training of both is essential.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used Conceptualization, F.J.G.M. and D.G.B..; methodology, F.J.G.M., D.G.B.; formal analysis, F.J.G.M.; investigation, F.J.G.M..; data curation, F.J.G.M.; writing—original draft preparation, F.J.G.M. and D.G.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data was created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Altuve G. Critical thinking and its insertion in higher education. Accounting news Faces 2010, 13(20): 5-18.

- Arum, R., y Roksa, J. 2011. Academically adrift: Limited learning on college campuses. University of Chicago Press.

- Bejarano, Lina.M.; Galván, Francy E.; Lopez, Beatriz. 2014. Critical thinking and motivation towards critical thinking in psychology students. Rev. Aleth., 6.

- Bezanilla-Albisua, M.J.; Poblete-Ruiz, M.; Fernández-Nogueira, D.; Arranz-Turnes, S.; Campo-Carrasco, L. (2028) Critical Thinking from the Perspective of University Teachers. Study Pedagogicals, 44, 89–113.

- Díaz-Larenas, Claudio H.; Ossa-Cornejo, Carlos J.; Palma-Luengo, Maritza R.; Lagos-San Martín, Nelly.G.; Boudon-Araneda, Javiera I. 2019. The concept of critical thinking according to Chilean pedagogy students. Sophia Filos Collection. Educ., 27, 275–296.

- Dwyer, Christopher P. 2023. An Evaluative Review of Barriers to Critical Thinking in Educational and Real-World Settings. Journal of Intelligence 11: 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Ennis, R. 1987. A taxonomy of critical thinking disposition and abilities. In Baron y Stemberg (eds.). Teaching thinking skills. New York: Freeman.

- Epstein, R. 2006. Critical thinking. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Thomas Learning.

- Escurra, Miguel.; Delgado, Ana. 2008. Relationship between disposition towards critical thinking and thinking styles in university students in metropolitan Lima. Person, 11, 143–175.

- Facione, P. 1990. Critical thinking: A statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction. Millbrae, CA: The California Academic Press.

- Febres, M.; Laziness.; Africano, B. 2017. Alternative pedagogies develop critical thinking. To bring out, 21, 269–274.

- García Moro, Francisco José; Gomez Baya, Diego and Nicoletti, Javier Augusto. 2024. Being critical: thinking-doing from an ethic of good-being. Behavior Analysis and Modification 50 (184): 79-88. https://doi.org/10.33776/amc.v50i184.8359.

- García Moro, Francisco. J., Gadea Aiello, Walter. F., & Fernández Mora, Vicente. de J. 2021. Critical thinking in students of the Degree in Social Education. Class, 27, 279–295. https://doi.org/10.14201/aula202127279295.

- Halpern, Diane F. 199). Teaching critical thinking for transfer across domains. Dispositions, skills, structure training, and metacognitive monitoring. American Psychologist, 53 (4), 449-455. [CrossRef]

- Halpern, Diane. F. 2003. Thought and knowledge. An introduction to critical thinking (4ª Ed.). Erlbaum.

- Halpern, Diane F., and Dana S. Dunn. 2021. Critical Thinking: A Model of Intelligence for Solving Real-World Problems. Journal of. [CrossRef]

- Intelligence 9: 22.

- JASP Team (2024). JASP (Version 0.19.2)[Computer software].

- Huber, C. y Kuncel, N. (2015). Does College Teach Critical Thinking? A Meta-Analysis. Review of Educational Research. 86. 10.3102/0034654315605917.

- Jiménez Pérez, Elena del Pilar. 2023. «Critical thinking VS Critical competence: Critical reading». Reading Research 18 (1):1-26. https://doi.org/10.24310/isl.vi18.15839.

- Liu, Yan. 2022. Readability and adaptation of children’s literary works from the perspective of ideational grammatical metaphor. Journal of World Languages, 7(2): 334-354. https://doi.org/10.1515/jwl-2021-0020.

- Morancho, Vendrell I., and Rodríguez Mantilla, Jesús Miguel. 2020. "Critical Thinking: conceptualization and relevance within higher education." Journal of Higher Education 49,194: 9-25.

- Morin, Edgar. 2004. Introduction to complex thinking. Gedisa.

- Nieto Carracedo, A., Saiz, C. and Orgaz, B. (2009). Analysis of the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the HCTAES Halpern Test for the evaluation of critical thinking through everyday situations. REMA, 14(1).1-15.

- Pantoja Vargas, L. (2012). Deontology and deontological code of the social educator. Social Pedagogy. Interuniversity Magazine, 19, 65-79. http://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/3827746.pdf.

- Pithers, R. y Soden, R. 2000. Critical thinking in education. Educational research, 42(3), 237-249.

- Rodríguez Pérez, A.; González Méndez, R. 1995. Five hypotheses about implicit theories. Rev. Psychol. Gen. Appl., 48: 221–229.

- Rodrigo, M.J.; Correa, N. Implicit Theories, Mental Models and Educational Change. 1999. In Strategic Learning. Teaching to Think from the Curriculum; Well , J.I. , Moreno , C. , Eds.; Santillana: Madrid; pp. 100-1 75–85.

- Roohr, Katrina.; Olivera-Aguilar, Margarita.; Ling, Guangming.; Rikoon, Samuel. 2019. A multi-level modeling approach to investigating students’ critical thinking at higher education institutions. Assess. Eval. High. Educ., 44, 946–960. [CrossRef]

- Stake, Robert E. 2004. Research with case studies. Morata.

- Saiz, Carlos, and Rivas F. Silvia. 2023. "Critical Thinking, Formation, and Change" Journal of Intelligence 11, no. 12: 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence11120219.

- Sánchez, J.L.; Farrán, X. C.; Baiges, E. B. and Suárez-Guerrero, Cr. (2019). Critical treatment of university students' information from personal learning environments. Educação e Pesquisa, 45, e193355. Epub May 30, 2019. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634201945193355.

- Tamayo, O.E.; Zona, R.; Loaiza, Y.E. Critical thinking in education. Some central categories in your study. Rev. Latinam. Study Educ. 2015, 11, 111–133.

- UNESCO (1998). World Conference on Higher Education: Higher Education in the 21st Century. Vision and action. Volume I, Final report. UNESCO.

- UNESCO (2009). Communiqué World Conference on Higher Education: The new dynamics of higher education and research for social change and development. UNESCO. http://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/peredu/v31n126/v31n126a8.pdf.

- UNESCO (2010). World Conference on Higher Education - 2009: The new dynamics of higher education and research for social change and development (UNESCO Headquarters, Paris, 5-8 July 2009). Release. (July 8, 2009). Communicate. UNESCO.

- UNESCO. (2015). Rethinking education: towards a global common good?. UNESCO.

- UNESCO. (2019). Regional comparative and explanatory study (ERCE 2019). UNESCO.

- UNESCO (2021a). Paths towards 2050 and beyond. Results of a public consultation on the futures of higher education.UNESCO.https://www.iesalc.unesco.org/los-futuros-de-la-educacion-superior/caminos-\\hacia-2050-y-mas -there/.

- UNESCO (2021b). Think beyond the limits. Perspectives on the future of Higher Education until 2050. UNESCO.

- Valenzuela, J.; Nieto, A.M.; Muñoz, C. 2014. Motivation and dispositions: Alternative approaches to explain the performance of.

- critical thinking skills. Rev. Electronic Research. Educ., 16, 16–32.

- Walker, Susan K., y LeBoeuf, Samantha. (2022, June 14). Relationships in teaching for critical thinking dispositions and skills. 8th International Conference on Higher Education Advances (HEAd’22). Eighth International Conference on Higher Education Advances. https://doi.org/10.4995/HEAd22.2022.14682.

- Informing is not communicating.

- World Economic Forum. The Future of Jobs Report: 2020. Available online: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_of_Jobs_2020.pdf (accessed on 2 Nov 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).