Submitted:

23 December 2024

Posted:

24 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

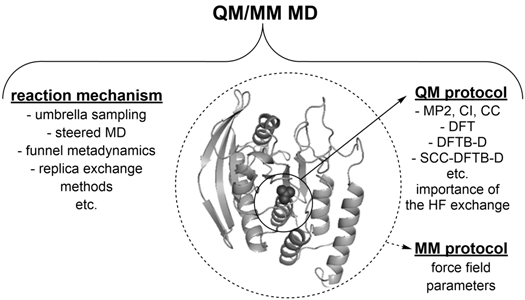

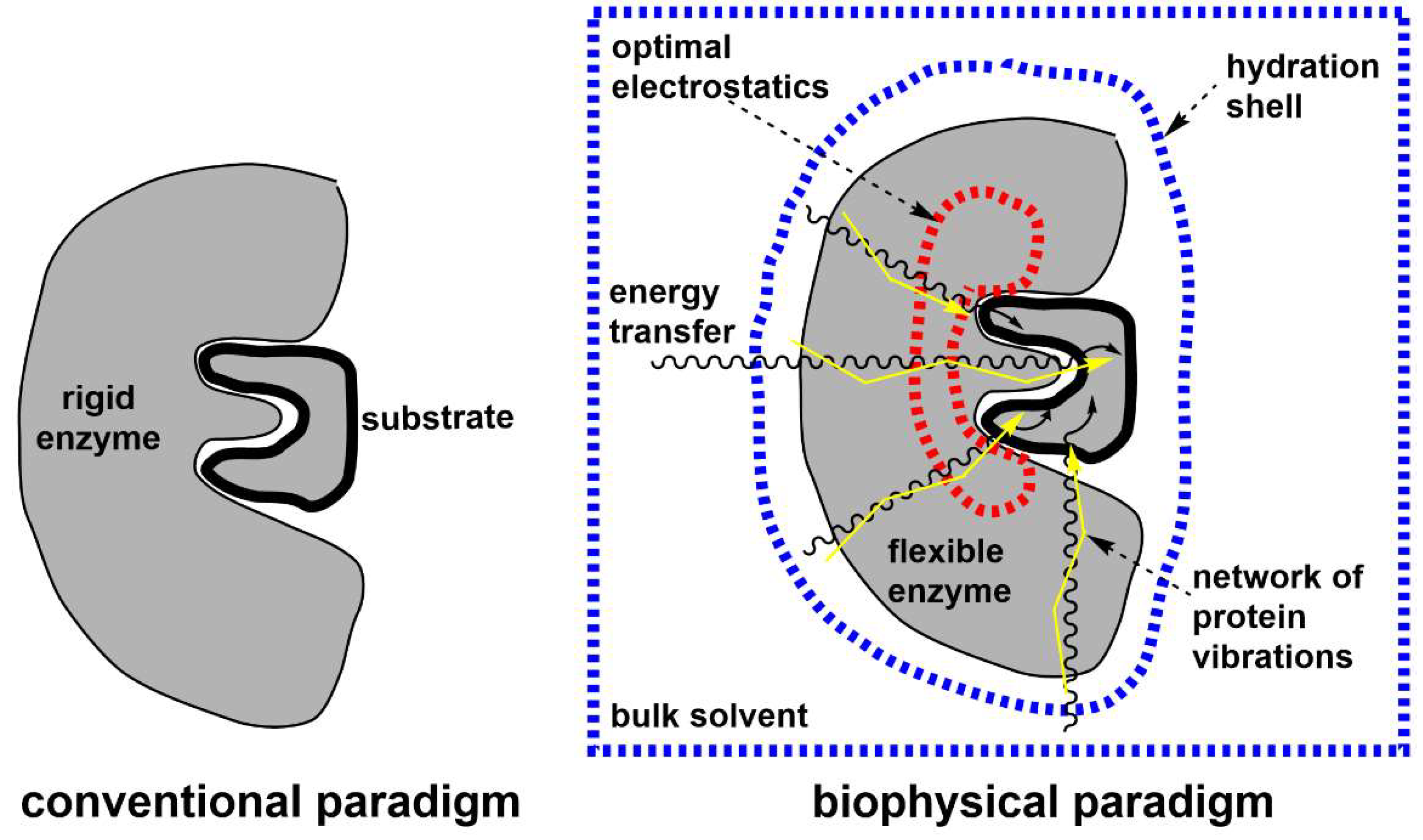

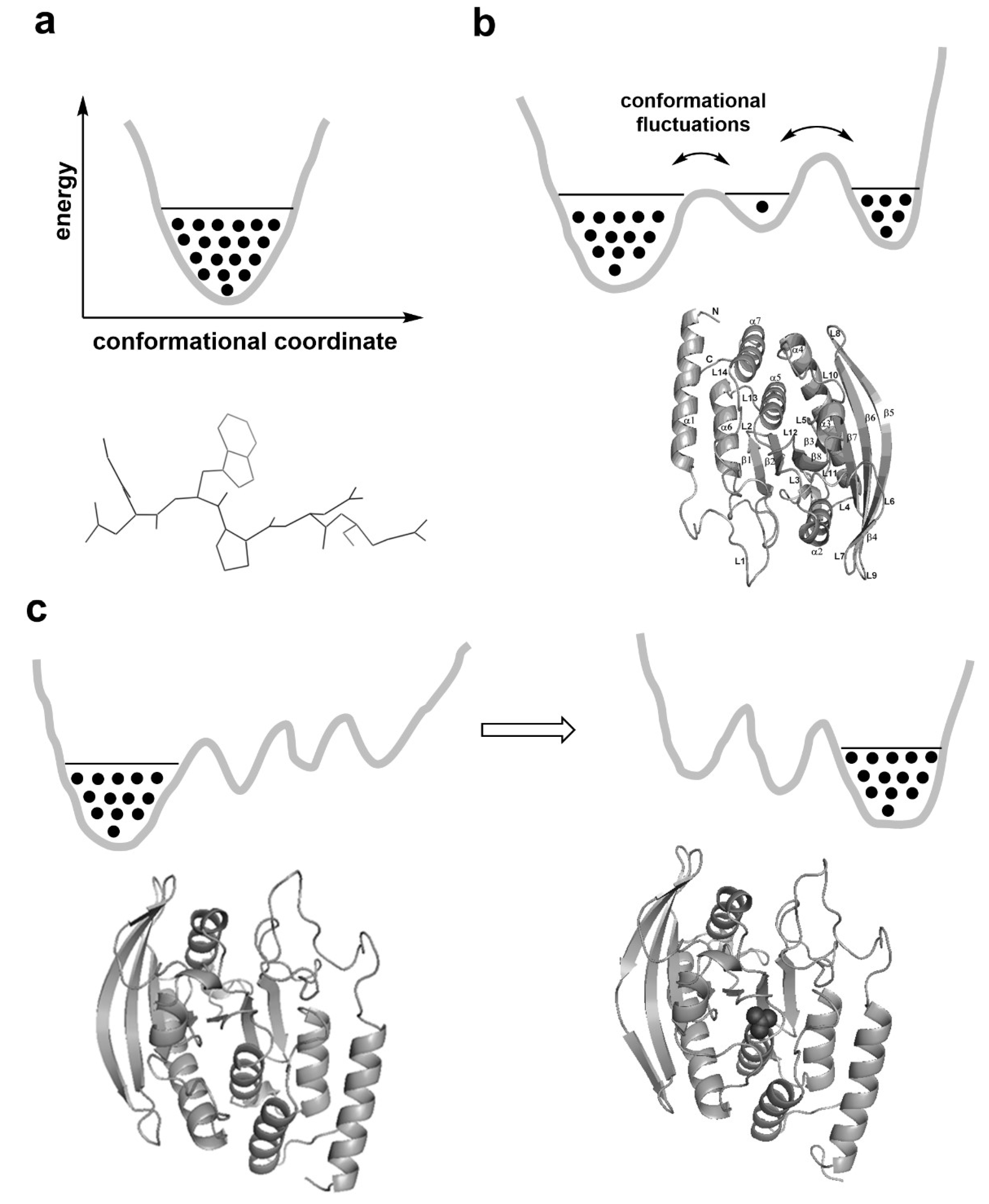

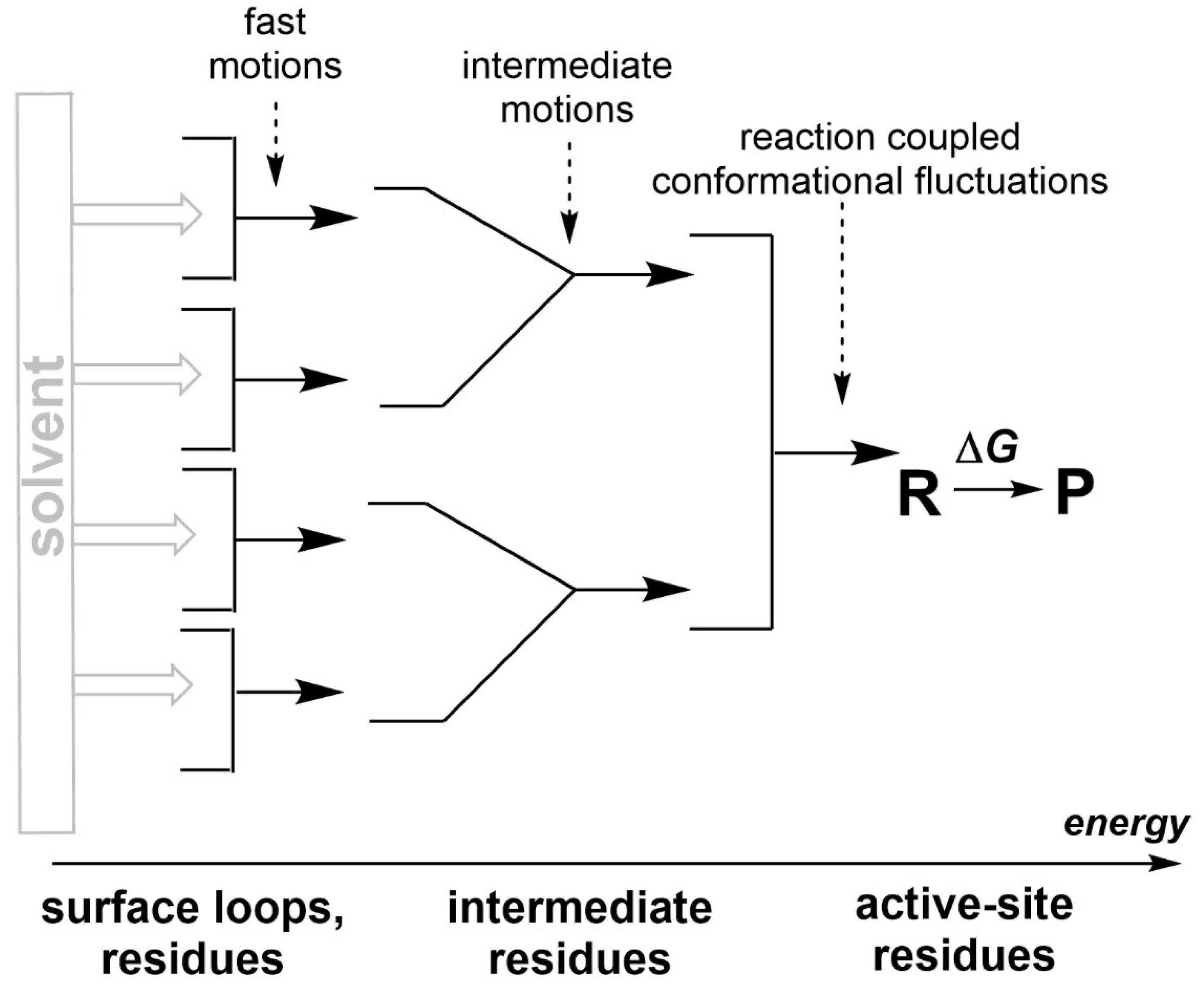

2. Reaction-promoting conformational fluctuations in the enzyme structure

3. On the relevant structural basis of enzymatic function

4. Future outlook

Acknowledgment

Disclosure statement

References

- Agarwal, P. K. (2004). Cis/trans isomerization in HIV-1 capsid protein catalyzed by cyclophilin A: insights from computational and theoretical studies. Proteins, 56(3), 449-463. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P. K. (2005). Role of protein dynamics in reaction rate enhancement by enzymes. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 127(43), 15248-15256. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P. K. (2006). Enzymes: an integrated view of structure, dynamics and function. Microbial Cell Factories, 5, 2. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P. K. (2019). A biophysical perspective on enzyme catalysis. Biochemistry, 58(6), 438-449. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P. K., Billeter, S. R., & Hammes-Schiffer, S. (2002a). Nuclear quantum effects and enzyme dynamics in dihydrofolate reductase catalysis. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 106(12), 3283-3293. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P. K., Billeter, S. R., Rajagopalan, P. T. R., Benkovic, S. J., & Hammes-Schiffer, S. (2002b). Network of coupled promoting motions in enzyme catalysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 99(5), 2794-2799. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P. K., Geist, A., & Gorin, A. (2004). Protein dynamics and enzymatic catalysis: investigating the peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerization activity of cyclophilin A. Biochemistry, 43(33), 10605-10618. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P. K., Schultz, C., Kalivretenos, A., Ghosh, B., & Broedel, S. E. (2012). Engineering a hyper-catalytic enzyme by photoactivated conformation modulation. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, 3(9), 1142-1146. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P. K., Webb, S. P., & Hammes-Schiffer, S. (2000). Computational studies of the mechanism for proton and hydride transfer in liver alcohol dehydrogenase. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 122(19), 4803-4812. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N., Babu, B. V., Singh, S., & Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2012). An efficient one-pot three-component synthesis of highly functionalized coumarin fused indenodihydropyridine and chromeno[4,3-b]quinoline derivatives. Heterocycles, 85(7), 1629-1653. [CrossRef]

- Amaro R. E., & Li, W. W. (2010). Emerging methods for ensemble based virtual screening. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry, 10(1), 3-13. [CrossRef]

- Andricioaei, I., & Karplus, M. (2001). On the calculation of entropy from covariance matrices of the atomic fluctuations. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 115(14), 6289-6292. [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, D., & Schwartz, S. D. (2011). Protein dynamics and enzymatic chemical barrier passage. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 115(51), 15147-15158. [CrossRef]

- Arora, K., & Brooks, C. L. III (2009). Functionally important conformations of the Met20 loop in dihydrofolate reductase are populated by rapid thermal fluctuations. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 131(15), 5642-5647. [CrossRef]

- Aviram, H. Y., Pirchi, M., Mazal, H., Barak, Y., Riven, I., & Haran, G. (2018). Direct observation of ultrafast large-scale dynamics of an enzyme under turnover conditions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(13), 3243-3248. [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, J., & Chothia, C. (1979). Hemoglobin: the structural changes related to ligand binding and its allosteric mechanism. Journal of Molecular Biology, 129(2), 175-200. [CrossRef]

- Bandaria, J. N., Dutta, S., Hill, S. E., Kohen, A., & Cheatum, C. M. (2008). Fast enzyme dynamics at the active site of formate dehydrogenase. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 130(1), 22-23. [CrossRef]

- Bathelt, C. M., Ridder, L., Mulholland, A. J., & Harvey, J. N. (2003). Aromatic hydroxylation by cytochrome P450: model calculations of mechanism and substituent effects. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 125(49), 15004-15005. [CrossRef]

- Bathelt, C. M., Ridder, L., Mulholland, A. J., & Harvey, J. N. (2004). Mechanism and structure-reactivity relationships for aromatic hydroxylation by cytochrome P450. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry, 2(20), 2998-3005. [CrossRef]

- Bathelt, C. M., Mulholland, A. J., & Harvey, J. N. (2008). QM/MM modeling of benzene hydroxylation in human cytochrome P450 2C9. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 112(50), 13149-13156. [CrossRef]

- Becke, A. D. (1993). A new mixing of Hartree-Fock and local density-functional theories. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 98(2), 1372-1377. [CrossRef]

- Bellissent-Funel, M. C., Hassanali, A., Havenith, M., Henchman, R., Pohl, P., Sterpone, F., van der Spoel, D., Xu, Y., & Garcia, A. E. (2016). Water determines the structure and dynamics of proteins. Chemical Reviews, 116(13), 7673-7697. [CrossRef]

- Benkovic, S. J. (1992). Catalytic antibodies. Annual Review of Biochemistry, 61, 29-54. [CrossRef]

- Benkovic, S. J., Hammes, G. G., & Hammes-Schiffer, S. (2008). Free-energy landscape of enzyme catalysis. Biochemistry, 47(11), 3317-3321. [CrossRef]

- Billeter, S. R., Webb, S. P., Agarwal, P. K., Iordanov, T., & Hammes-Schiffer, S. (2001). Hydride transfer in liver alcohol dehydrogenase: quantum dynamics, kinetic isotope effects, and role of enzyme motion. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 123(45), 11262-11272. [CrossRef]

- Boehr, D. D., D’Amico, R. N., & O’Rourke, K. F. (2018). Engineered control of enzyme structural dynamics and function. Protein Science, 27(4), 825-838. [CrossRef]

- Boehr, D. D., Dyson, H. J., & Wright, P. E. (2006). An NMR perspective on enzyme dynamics. Chemical Reviews, 106(8), 3055-3079. [CrossRef]

- Boehr, D. D., Schnell, J. R., McElheny, D., Bae, S. H., Duggan, B. M., Benkovic, S. J., Dyson, H. J., & Wright, P. E. (2013). A distal mutation perturbs dynamic amino acid networks in dihydrofolate reductase. Biochemistry, 52(27), 4605-4619. [CrossRef]

- Borreguero, J. M., He, J. H., Meilleur, F., Weiss, K. L., Brown, C. M., Myles, D. A., Herwig, K. W., & Agarwal, P. K. (2011). Redox-promoting protein motions in rubredoxin. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 115(28), 8925-8936. [CrossRef]

- Bruice, T. C., & Benkovic, S. J. (2000). Chemical basis for enzyme catalysis. Biochemistry, 39(21), 6267-6274. [CrossRef]

- Camilloni, C., Sahakyan, A. B., Holliday, M. J., Isern, N. G., Zhang, F. L., Eisenmesser, E. Z., & Vendruscolo, M. (2014). Cyclophilin A catalyzes proline isomerization by an electrostatic handle mechanism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(28), 10203-10208. [CrossRef]

- Chi, C. N., Vogeli, B., Bibow, S., Strotz, D., Orts, J., Guntert, P., & Riek, R. (2015). A structural ensemble for the enzyme cyclophilin reveals an orchestrated mode of action at atomic resolution. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 54(40), 11657-11661. [CrossRef]

- Choy, M. S., Li, Y., Machado, L., Kunze, M. B. A., Connors, C. R., Wei, X., Lindorff-Larsen, K., Page, R., & Peti, W. (2017). Conformational rigidity and protein dynamics at distinct timescales regulate PTP1B activity and allostery. Molecular cell, 65(4), 644-658.e5. [CrossRef]

- Clouthier, C. M., Morin, S., Gobeil, S. M. C., Doucet, N., Blanchet, J., Nguyen, E., Gagne, S. M., & Pelletier, J. N. (2012). Chimeric beta-lactamases: global conservation of parental function and fast time-scale dynamics with increased slow motions. PLoS One, 7(12): e52283. [CrossRef]

- Coman, R. M., Robbins, A. H., Goodenow, M. M., Dunn, B. M., & McKenna, R. (2008). High-resolution structure of unbound human immunodeficiency virus 1 subtype C protease: implications of flap dynamics and drug resistance. Acta Crystallographica Section D: Biological Crystallography, D64(Pt7), 754-763. [CrossRef]

- Duff, M. R., Jr., Borreguero, J. M., Cuneo, M. J., Ramanathan, A., He, J., Kamath, G., Chennubhotla, S. C., Meilleur, F., Howell, E. E., Herwig, K. W., Myles, D. A. A., & Agarwal, P. K. (2018). Modulating enzyme activity by altering protein dynamics with solvent. Biochemistry, 57(29), 4263-4275. [CrossRef]

- Eisenmesser, E. Z., Bosco, D. A., Akke, M., & Kern, D. (2002). Enzyme dynamics during catalysis. Science, 295(5559), 1520-1523. [CrossRef]

- Eisenmesser, E. Z., Millet, O., Labeikovsky, W., Korzhnev, D. M., Wolf-Watz, M., Bosco, D. A., Skalicky, J. J., Kay, L. E., & Kern, D. (2005). Intrinsic dynamics of an enzyme underlies catalysis. Nature, 438(7064), 117-121. [CrossRef]

- Elstner, M., Frauenheim, T., & Suhai, S. (2003). An approximate DFT method for QM/MM simulations of biological structures and processes. Journal of Molecular Structrure: THEOCHEM, 632(1-3), 29-41. [CrossRef]

- Elstner, M., Hobza, P., Frauenheim, T., Suhai, S., & Kaxiras, E. (2001). Hydrogen bonding and stacking interactions of nucleic acid base pairs: a density-functional-theory based treatment. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 114(12), 5149-5155. [CrossRef]

- Elstner, M., Porezag, D., Jungnickel, G., Elsner, J., Haugk, M., Frauenheim, T., Suhai, S., & Seifert, G. (1998). Self-consistent-charge density-functional tight-binding method for simulations of complex materials properties. Physical Review B, 58(11), 7260-7268. [CrossRef]

- Fenimore, P. W., Frauenfelder, H., McMahon, B. H., & Young, R. D. (2004). Bulk-solvent and hydration-shell fluctuations, similar to alpha- and beta-fluctuations in glasses, control protein motions and functions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101(40), 14408-14413. [CrossRef]

- Fersht Alan (1985). Enzyme structure and mechanism (2nd edition). New York, NY: W. H. Freeman and Company.

- Fischer, E. (1894). Einfluss der configuration auf die wirkung den enzyme. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft, 27(3), 2985-2993. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, J. S., Clarkson, M. W., Degnan, S. C., Erion, R., Kern, D., & Alber, T. (2009). Hidden alternative structures of proline isomerase essential for catalysis. Nature, 462(7273), 669-673. [CrossRef]

- Frauenfelder, H., McMahon, B. H., Austin, R. H., Chu, K., & Groves, J. T. (2001). The role of structure, energy landscape, dynamics, and allostery in the enzymatic function of myoglobin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 98(5), 2370-2374. [CrossRef]

- Gagne, D., Charest, L. A., Morin, S., Kovrigin, E. L., & Doucet, N. (2012). Conservation of flexible residue clusters among structural and functional enzyme homologues. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 287(53), 44289-44300. [CrossRef]

- Gagne, D., Narayanan, C., & Doucet, N. (2015). Network of long-range concerted chemical shift displacements upon ligand binding to human angiogenin. Protein Science, 24(4), 525-533. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Viloca, M., Gao, J., Karplus, M., & Truhlar, D. G. (2004). How enzymes work: analysis by modern rate theory and computer simulations. Science, 303(5655), 186-195. [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S., Antony, J., Schwabe, T., & Muck-Lichtenfeld, C. (2007). Density functional theory with dispersion corrections for supramolecular structures, aggregates, and complexes of (bio)organic molecules. Organic and Biomolecular Chemistry, 5, 741-758. [CrossRef]

- Guallar, V., Baik, M.-H., Lippard, S. J., & Friesner, R. A. (2003). Peripheral heme substituents control the hydrogen-atom abstraction chemistry in cytochromes P450. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 100(12), 6998-7002. [CrossRef]

- Gur, M., Taka, E., Yilmaz, S. Z., Kilinc, C., Aktas, U., & Golcuk, M. (2020). Conformational transition of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein between its closed and open states. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 153(7), 075101. [CrossRef]

- Hachim, M. E., Sadik, K., Byadi, S., & Aboulmouhajir, A. (2020). Electronic investigation and spectroscopic analysis using DFT with the long-range dispersion correction on the six lowest conformers of 2.2. 3-trimethyl pentane. Journal of Molecular Modeling, 26(7), 168. [CrossRef]

- Hall, R., Dixon, T., & Dickson, A. (2020). On calculating free energy differences using ensembles of transition paths. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, 7, 106. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J. N., Bathelt, C. M., & Mulholland, A. J. (2006). QM/MM modeling of compound I active species in cytochrome P450, cytochrome C peroxidase, and ascorbate peroxidase. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 27(12), 1352-1362. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, R. J., & McLeish, T. C. B. (2006). Coupling of global and local vibrational modes in dynamic allostery of proteins. Biophysical Journal, 91(6), 2055-2062. [CrossRef]

- Heaslet, H., Rosenfeld, R., Giffin, M., Lin, Y. C., Tam, K., Torbett, B. E., Elder, J. H., McRee, D. E., & Stout, C. D. (2007). Acta Crystallographica Section D: Biological Crystallography, 63(Pt8), 866-875. [CrossRef]

- Henzler-Wildman, K. A., Lei, M., Thai, V., Kerns, S. J., Karplus, M., & Kern, D. (2007). A hierarchy of timescales in protein dynamics is linked to enzyme catalysis. Nature, 450(7171), 913-916. [CrossRef]

- Himo, F. (2017). Recent trends in quantum chemical modeling of enzymatic reactions. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 139(20), 6780-6786. [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, J. S., Arora, K., Brooks, C. L., & Schramm, V. L. (2010). Conformational dynamics in human purine nucleoside phosphorylase with reactants and transition-state analogues. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 114(49), 16263-16272. [CrossRef]

- Hobza, P., Sponer, J., & Reschel, T. (1995). Density functional theory and molecular clusters. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 16(11), 1315-1325. [CrossRef]

- Holliday, M. J., Camilloni, C., Armstrong, G. S., Vendruscolo, M., & Eisenmesser, E. Z. (2017). Networks of dynamic allostery regulate enzyme function. Structure, 25(2), 276-286. [CrossRef]

- Howard, B. R., Vajdos, F. F., Li, S., Sundquist, W. I., & Hill, C. P. (2003). Structural insights into the catalytic mechanism of cyclophilin A. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, 10(6), 475-481. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X., & Erec Stebbins, C. (2006). Dynamics of the WPD loop of the Yersinia protein tyrosine phosphatase. Biophysical Journal, 91(3), 948-956. [CrossRef]

- Ichiye, T., & Karplus, M. (1988). Anisotropy and anharmonicity of atomic fluctuations in proteins - implications for X-ray-analysis. Biochemistry, 27(9), 3487-3497. [CrossRef]

- Jurecka, P., Cerny, J., Hobza, P., & Salahub, D. R. (2007). Density functional theory augmented with an empirical dispersion term. Interaction energies and geometries of 80 noncovalent complexes compared with ab initio quantum mechanics calculations. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 28(2), 555-569. [CrossRef]

- Kamerlin, S. C. L., & Warshel, A. (2010). At the dawn of the 21st century: is dynamics the missing link for understanding enzyme catalysis? Proteins, 78(6), 1339-1375. [CrossRef]

- Kim, T. H., Mehrabi, P., Ren, Z., Sljoka, A., Ing, C., Bezginov, A., Ye, L., Pomes, R., Prosser, R. S., & Pai, E. F. (2017). The role of dimer asymmetry and protomer dynamics in enzyme catalysis. Science, 355(6322), eaag2355. [CrossRef]

- Klinman, J. P. (2013). Importance of protein dynamics during enzymatic C-H bond cleavage catalysis. Biochemistry, 52(12), 2068-2077. [CrossRef]

- Klinman, J. P., Offenbacher, A. R., & Hu, S. (2017). Origins of enzyme catalysis: experimental findings for C-H activation, new models, and their relevance to prevailing theoretical constructs. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 139(51), 18409-18427. [CrossRef]

- Kohen, A. (2015). Role of dynamics in enzyme catalysis: substantial versus semantic controversies. Accounts of Chemical Research, 48(2), 466-473. [CrossRef]

- Kondo, T., Pinnola, A., Chen, W. J., Dall’Osto, L., Bassi, R., & Schlau-Cohen, G. S. (2017). Single-molecule spectroscopy of LHCSR1 protein dynamics identifies two distinct states responsible for multi-timescale photosynthetic photoprotection. Nature Chemistry, 9(8), 772-778. [CrossRef]

- Koshland, D. E. (1958). Application of a theory of enzyme specificity to protein synthesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 44(2), 98-104. [CrossRef]

- Kristyan, S., & Pulay, P. (1994). Can (semi)local density functional theory account for the London dispersion forces? Chemical Physics Letters, 229(3), 175-180. [CrossRef]

- Krivitskaya, A. V., Khrenova, M. G., & Nemukhin, A. V. (2021). Two sides of quantum-based modeling of enzyme-catalyzed reactions: mechanistic and electronic structure aspects of the hydrolysis by glutamate carboxypeptidase. Molecules, 26(20), 6280. [CrossRef]

- Kuban-Jankowska, A., Sahu, K. K., Gorska, M., Niedzialkowski, P., Tuszynski, J. A., Ossowski, T., & Wozniak, M. (2016). Aurintricarboxylic acid structure modifications lead to reduction of inhibitory properties against virulence factor YopH and higher cytotoxicity. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 32, 163. [CrossRef]

- Kubar, T., Jurecka, P., Cerny, J., Rezac, J., Otyepka, M., Valdes, H., & Hobza, P. (2007). Density-functional, density-functional tight-binding, and wave function calculations on biomolecular systems. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 11(26), 5642-5647. [CrossRef]

- Lange, O. F., Lakomek, N. A., Fares, C., Schroder, G. F., Walter, K. F. A., Becker, S., Meiler, J., Grubmuller, H., Griesinger, C., & de Groot, B. L. (2008). Recognition dynamics up to microseconds revealed from an RDC-derived ubiquitin ensemble in solution. Science, 320(5882), 1471-1475. [CrossRef]

- Lapatto, R., Blundell, T., Hemmings, A., Overington, J., Wilderspin, A., Wood, S., Merson, J. R., Whittle, P. J., Danley, D. E., Geoghegan, K. F., Hawrylik, S. J., Lee, S. E., Scheld K. G., & Hobart, P. M. (1989). X-ray analysis of HIV-1 proteinase at 2.7 Å resolution confirms structural homology among retroviral enzymes. Nature, 342(6247), 299-302. [CrossRef]

- Layfield, J. P., & Hammes-Schiffer, S. (2013). Calculation of vibrational shifts of nitrile probes in the active site of ketosteroid isomerase upon ligand binding. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 135(2), 717-725. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., Natarajan, M., Nashine, V. C., Socolich, M., Vo, T., Russ, W. P., Benkovic, S. J., & Ranganathan, R. (2008). Surface sites for engineering allosteric control in proteins. Science, 322(5900), 438-442. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. T., Yang, W. T., & Parr, R. G. (1988). Development of the Cole-Salvetti correlation energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Physical Review B Condens Matter, 37(2), 785-789. [CrossRef]

- Leitner, D. M. (2008). Energy flow in proteins. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry, 59, 233-259. [CrossRef]

- Limongelli, V. (2020). Ligand binding free energy and kinetics calculation in 2020. WIREs Computational Molecular Science, 10(4), e1455. [CrossRef]

- Limongelli, V., Bonomi, M., & Parrinello, M. (2013). Funnel metadynamics as accurate binding free-energy method. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(16), 6358-6363. [CrossRef]

- Lisi, G. P., & Loria, J. P. (2016). Solution NMR spectroscopy for the study of enzyme allostery. Chemical Reviews, 116(11), 6323-6369. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F., Kovalevsky, A. Y., Louis, J. M., Boross, P. I., Wang, Y. F., Harrison, R. W., & Weber, I. T. (2006). Mechanism of drug resistance revealed by the crystal structure of the unliganded HIV-1 protease with F53L mutation. Journal of Molecular Biology, 358(5), 1191-1199. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Li, Y., Wu, S., Li, G., & Chu, H. (2022). Synergistic effect of conformational changes in phosphoglycerate kinase 1 product release. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics, 41(19), 10059-10069. [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, R., Harvey, J. N., & Mulholland, A. J. (2010). Compound I reactivity defines alkene oxidation selectivity in cytochrome P450cam. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 114(2), 1156-1162. [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, R., Olah, J., Mulholland, A. J., & Harvey, J. N. (2011). Does compound I vary significantly between isoforms of cytochrome P450? Journal of the American Chemical Society, 133(39), 15464-15474. [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, R., Harvey, J. N., & Mulholland, A. J. (2012). A practical guide to modelling enzyme-catalysed reactions. Chemical Society Reviews, 41(8), 3025-3038. [CrossRef]

- Love, O., Pacheco Lima, M. C., Clark, C., Cornillie, S., Roalstad, S., & Cheatham III, T. E. (2022). Evaluating the accuracy of the AMBER protein force fields in modeling dihydrofolate reductase structures: misbalance in the conformational arrangements of the flexible loop domains. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics, 41(13), 5946-5960. [CrossRef]

- Machleder, S. Q., Pineda, J. R. E. T., & Schwartz, S. D. (2010). On the origin of the chemical barrier and tunneling in enzymes. Journal of Physical Organic Chemistry, 23(7), 690-695. [CrossRef]

- Martin, P., Vickrey, J. F., Proteasa, G., Jimenez, Y. L., Wawrzak, Z., Winters, M. A., Merigan, T. C., & Kovari, L. C. (2005). “Wide-open” 1.3 Å structure of a multidrug-resistant HIV-1 protease as a drug target. Structure, 13(12), 1887-1895. [CrossRef]

- Micheletti, C. (2013). Comparing proteins by their internal dynamics: exploring structure-function relationships beyond static structural alignments. Physics of Life Reviews, 10(1), 1-26. [CrossRef]

- Mihajlovic, M. L., & Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2008). Another look at the molecular mechanism of the resistance of H5N1 influenza A virus neuraminidase (NA) to oseltamivir (OTV). Biophysical Chemistry, 136(2-3), 152-158. [CrossRef]

- Mihajlovic, M. L., & Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2009a). Applications of the ArgusLab4/AScore protocol in the structure-based binding affinity prediction of various inhibitors of group-1 and group-2 influenza virus neuraminidases (NAs). Molecular Simulation, 35(4), 311-324. [CrossRef]

- Mihajlovic, M. L., & Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2009b). Some novel insights into the binding of oseltamivir and zanamivir to H5N1 and N9 influenza virus neuraminidases: a homology modeling and flexible docking study. Journal of the Serbian Chemical Society, 74(1), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2001). Quantitative characterization of the P-C bonds in ylides of phosphorus. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 22(13), 1387-1395. [CrossRef]

- Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2002). Qualitative characterization of the P-C bonds in ylides of phosphorus. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 106(30), 7026-7033. [CrossRef]

- Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2003a). Acrylonitrile (AN)/Cu9(100) interfaces: electron distribution and nature of bonded interactions. Canadian Journal of Chemistry, 81(6), 542-554. [CrossRef]

- Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2003b). Sharing analysis of the behavior of electrons in some simple ylides. Chemical Physics, 286(1), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2004). Invariant description of the behavior of electrons in donor–acceptor molecules. Chemical Physics Letters, 392(4-6), 419-427. [CrossRef]

- Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2005). Cross-linking between thymine and indolyl radical: Possible mechanisms for cross-linking of DNA and tryptophan-containing peptides. Bioconjugate Chemistry, 16(3), 588-597. [CrossRef]

- Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2009). On the structure-based design of novel inhibitors of H5N1 influenza A virus neuraminidase (NA). Biophysical Chemistry, 140(1-3), 35-38. [CrossRef]

- Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2010a). Electronic processes at organic/metal interfaces: recent progress and pitfalls. Current Organic Chemistry, 14(2), 198-211. [CrossRef]

- Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2010b). Advances in the structure-based design of the influenza A neuraminidase inhibitors. Current Drug Targets, 11(3), 315-326. [CrossRef]

- Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2012). Advances in boron-based supramolecular architecture. Current Organic Synthesis, 9(2), 233-246. [CrossRef]

- Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2013). Progress in structure-based design of EGFR inhibitors. Current Drug Targets, 14(7), 817-829. [CrossRef]

- Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2014a). Structural elucidation of unique inhibitory activities of two thiazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidines against epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR): implications for successful drug design. Medicinal Chemistry, 10(1), 46-58. [CrossRef]

- Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2014b). Inhibitory activity against epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) based on single point mutations of active site residues. Medicinal Chemistry, 10(3), 252-270. [CrossRef]

- Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2015). Sequence-dependent binding of flavonoids to duplex DNA. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 55(2), 421-433. [CrossRef]

- Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2018). Structural insights into the binding of small ligand molecules to a G-quadruplex DNA located in the HIV-1 promoter. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics, 36(9), 2292-2302. [CrossRef]

- Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2019). Small-molecule interaction with G-quadruplex DNA: context of anti-cancer drug design. Croatica Chemica Acta, 92(1), 43-57. [CrossRef]

- Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2020). Quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics study on caspase-2 recognition by peptide inhibitors. Acta Chimica Slovenica, 67(3), 876-884. [CrossRef]

- Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2022). On the inhibition of cytochrome P450 3A4 by structurally diversified flavonoids. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics, 40(20), 9713-9723. [CrossRef]

- Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2023). On the recognition of Yersinia protein tyrosine phosphatase by carboxylic acid derivatives. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics, 41(5), 1879-1894. [CrossRef]

- Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2024a). On the specificity of aurintricarboxylic acid toward some phosphatases. ChemRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2024b). On the potential pharmacophore for the structure-based inhibitor design against phosphatases, ChemRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadkhani, R., Ramezanzadeh, M., Akbarzadeh, S., Bahlakeh, G., & Ramezanzadeh, B. (2020). Graphene oxide nanoplatforms reduction by green plant-sourced organic compounds for construction of an active anti-corrosion coating; experimental/electronic-scale DFT-D modeling studies. Chemical Engineering Journal, 397, 125433. [CrossRef]

- Monod, J., Changeux, J. P., & Jacob, F. (1963). Allosteric proteins and cellular control systems. Journal of Molecular Biology, 6(4), 306-329. [CrossRef]

- Moritsugu, K., & Kidera, A. (2004). Protein motions represented in moving normal mode coordinates. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 108(12), 3890-3898. [CrossRef]

- Nagel, Z. D., & Klinman, J. P. (2009). A 21st century revisionist’s view at a turning point in enzymology. Nature Chemical Biology, 5(8), 543-550. [CrossRef]

- Nagel, Z. D., Cun, S. J., & Klinman, J. P. (2013). Identification of a long-range protein network that modulates active site dynamics in extremophilic alcohol dehydrogenases. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 288(20), 14087-14097. [CrossRef]

- Navia, M. A., Fitzgerald, P. M., McKeever, B. M., Leu, C. T., Heimbach, J. C., Herber, W. K., Sigal, I. S., Darke, P. L., & Springer, J. P. (1989). Three-dimensional structure of aspartyl protease from human immunodeficiency virus HIV-1. Nature, 337(6208), 615-620. [CrossRef]

- Onions, S. T., Ito, K., Charron, C. E., Brown, R. J., Colucci, M., Frickel, F., Hardy, G., Joly, K., King-Underwood, J., Kizawa, Y., Knowles, I., Murray, P. J., Novak, A., Rani, A., Rapeport, G., Smith, A., Strong, P., Taddei, D. M., & Williams, J. G. (2016). The discovery of narrow spectrum kinase inhibitors: new therapeutic agents for the treatment of COPD and steroid-resistant asthma. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 59(5), 1727-1746. [CrossRef]

- Otten, R., Liu, L., Kenner, L. R., Clarkson, M. W., Mavor, D., Tawfik, D. S., Kern, D., & Fraser, J. S. (2018). Rescue of conformational dynamics in enzyme catalysis by directed evolution. Nature Communications, 9, 1314. [CrossRef]

- Palmer, A. G. III (2015). Enzyme dynamics from NMR spectroscopy. Accounts of Chemical Research, 48(2), 457-465. [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, A., & Mitrasinovic, P. M. (2010). Theoretical insights into dispersion and hydrogen-bonding interactions in biomolecular systems. Current Organic Chemistry, 14(2), 129-137. [CrossRef]

- Pillai, B., Kannan, K. K., & Hosur, M. V. (2001). 1.9 Å x-ray study shows closed flap conformation in crystals of tethered HIV-1 PR. Proteins, 43(1), 57-64. [CrossRef]

- Pisliakov, A. V., Cao, J., Kamerlin, S. C. L., & Warshel, A. (2009). Enzyme millisecond conformational dynamics do not catalyze the chemical step. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106(41), 17359-17364. [CrossRef]

- Pontiggia, F., Colombo, G., Micheletti, C., & Orland, H. (2007). Anharmonicity and self-similarity of the free energy landscape of protein G. Physical Review Letters, 98(4), 048102. [CrossRef]

- Quaytman, S. L., & Schwartz, S. D. (2007). Reaction coordinate of an enzymatic reaction revealed by transition path sampling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104(30), 12253-12258. [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, A., & Agarwal, P. K. (2009). Computational identification of slow conformational fluctuations in proteins. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 113(52), 16669-16680. [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, A., & Agarwal, P. K. (2011). Evolutionarily conserved linkage between enzyme fold, flexibility, and catalysis. PLoS Biology, 9(11), e1001193. [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, A., Savol, A., Burger, V., Chennubhotla, C., & Agarwal, P. K. (2014). Protein conformational populations and functionally relevant sub-states. Accounts of Chemical Research, 47(1), 149-156. [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, A., Savol, A. J., Langmead, C. J., Agarwal, P. K., & Chennubhotla, C. S. (2011). Discovering conformational sub-states relevant to protein function. PLoS One, 6(1), e15827. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, K. A., McLaughlin, R. N., & Ranganathan, R. (2011). Hot spots for allosteric regulation on protein surfaces. Cell, 147(7), 1564-1575. [CrossRef]

- Richard, J. P. (2013). Enzymatic rate enhancements: a review and perspective. Biochemistry, 52(12), 2009-2011. [CrossRef]

- Robbins, A. H., Coman, R. M., Bracho-Sanchez, E., Fernandez, M. A., Gilliland, C. T., Li, M., Agbandje-McKenna, M., Wlodawer, A., Dunn, B. M., & McKenna R. (2010). Structure of the unbound form of HIV-1 subtype A protease: comparison with unbound forms of proteases from other HIV subtypes. Acta Crystallographica Section D: Biological Crystallography, 66(Pt3), 233-242. [CrossRef]

- Robertus, J. D., Kraut, J., Alden, R. A., & Birktoft, J. J. (1972). Subtilisin. Stereochemical mechanism involving transition-state stabilization. Biochemistry, 11(23), 4293-4303. [CrossRef]

- Sawaya, M. R., & Kraut, J. (1997). Loop and subdomain movements in the mechanism of Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase: crystallographic evidence. Biochemistry, 36(3), 586-603. [CrossRef]

- Schlitter, J. (1993). Estimation of absolute and relative entropies of macromolecules using the covariance matrix. Chemical Physics Letters, 215(6), 617-621.

- Schramm, A. M., Mehra-Chaudhary, R., Furdui, C. M., & Beamer, L. J. (2008). Backbone flexibility, conformational change, and catalysis in a phosphohexomutase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochemistry, 47(35), 9154-9162. [CrossRef]

- Schubert, H. L., Fauman, E. B., Stuckey, J. A., Dixon, J. E., & Saper, M. A. (1995). A ligand-induced conformational change in the Yersinia protein tyrosine phosphatase. Protein Science, 4(9), 1904-1913. [CrossRef]

- Sevrioukova, I. F., & Poulos, T. L. (2015). Anion-dependent stimulation of CYP3A4 monooxygenase. Biochemistry, 54, 4083-4096. [CrossRef]

- Shaik, S,, Kumar, D., de Visser, S. P., Altun, A., & Thiel, W. (2005). Theoretical perspective on the structure and mechanism of cytochrome P450 enzymes. Chemical Reviews, 105(6), 2279-2328 . [CrossRef]

- Shaik, S., Cohen, S., Wang, Y., Chen, H., Kumar, D., & Thiel, W. (2010). P450 enzymes: their structure, reactivity, and selectivity-modeled by QM/MM calculations. Chemical Reviews, 110(2), 949-1017. [CrossRef]

- Siegel, J. B., Zanghellini, A., Lovick, H. M., Kiss, G., Lambert, A. R., St Clair, J. L., Gallaher, J. L., Hilvert, D., Gelb, M. H., Stoddard, B. L., Houk, K. N., Michael, F. E., & Baker, D. (2010). Computational design of an enzyme catalyst for a stereoselective bimolecular Diels-Alder reaction. Science, 329(5989), 309-313. [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, S., Liu, Q. Z., Alzari, P. M., Hirel, P. H., & Poljak, R. J. (1991). The three-dimensional structure of the aspartyl protease from the HIV-1 isolate BRU. Biochimie, 73(11), 1391-1396. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y., Wells, J. A., & Arkin, M. R. (2011). Structural and enzymatic insights into caspase-2 protein substrate recognition and catalysis. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 286(39), 34147-34154. [CrossRef]

- Tehei, M., Franzetti, B., Wood, K., Gabel, F., Fabiani, E., Jasnin, M., Zamponi, M., Oesterhelt, D., Zaccai, G., Ginzburg, M., & Ginzburg, B. Z. (2007). Neutron scattering reveals extremely slow cell water in a Dead Sea organism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104(3), 766-771. [CrossRef]

- Veeraraghavan, N., Bevilacqua, P. C., & Hammes-Schiffer, S. (2010). Long-distance communication in the HDV ribozyme: insights from molecular dynamics and experiments. Journal of Molecular Biology, 402(1), 278-291. [CrossRef]

- Verkhivker G. M., Agajanian, S., Oztas, D., & Gupta, G. (2022). Computational analysis of protein stability and allosteric interaction networks in distinct conformational forms of the SARS-CoV-2 spike D614G mutant: reconciling functional mechanisms through allosteric model of spike regulation. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics, 40(20), 9724-9741. [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, V. S., Ryan, M. J., Dhruv, H. D., Gill, S., Eichhoff, O. M., Seashore-Ludlow, B., Kaffenberger, S. D., Eaton, J. K., Shimada, K., Aguirre, A. J., Viswanathan, S. R., Chattopadhyay, S., Tamayo, P., Yang, W. S., Rees, M. G., Chen, S., Boskovic, Z. V., Javaid, S., Huang, C., Wu, X., Tseng, Y. Y., Roider, E. M., Gao, D., Cleary, J. M., Wolpin, B. M., Mesirov, J. P., Haber, D. A., Engelman, J. A., Boehm, J. S., Kotz, J. D., Hon, C. S., Chen, Y., Hahn, W. C., Levesque, M. P., Doench, J. G., Berens, M. E., Shamji, A. F., Clemons, P. A., Stockwell, B. R., & Schreiber, S. L. (2017). Dependency of a therapy-resistant state of cancer cells on a lipid peroxidase pathway. Nature, 547(7664), 453-457. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-Q., Cheng, X.-C., Dong, W.-L., Wang, R.-L., & Chou, K.-C. (2010). Three new powerful oseltamivir derivatives for inhibiting the neuraminidase of influenza virus. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 401(2), 188-191. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Goodey, N. M., Benkovic, S. J., & Kohen, A. (2006). Coordinated effects of distal mutations on environmentally coupled tunneling in dihydrofolate reductase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 103(43), 15753-15758. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K., & Zhu, W. (2020). Insight into the roles of small molecules in CL-20 based host-guest crystals: a comparative DFT-D study. CrystEngComm, 22(37), 6228-6238. [CrossRef]

- Warshel, A., Sharma, P. K., Kato, M., Xiang, Y., Liu, H. B., & Olsson, M. H. M. (2006). Electrostatic basis for enzyme catalysis. Chemical Reviews, 106(8), 3210-3235. [CrossRef]

- Xie, A. H., van der Meer, L., & Austin, R. H. (2002). Excited-state lifetimes of far-infrared collective modes in proteins. Journal of Biological Physics, 28(2), 147-154. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M., Huang, J., & MacKerell, A. D. Jr. (2015). Enhanced conformational sampling using replica exchange with concurrent solute scaling and hamiltonian biasing realized in one dimension. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 11(6), 2855-2867. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M., & MacKerell, A. D. Jr. (2015). Conformational sampling of oligosaccharides using Hamiltonian replica exchange with two-dimensional dihedral biasing potentials and the weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM). Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 11(2), 788-799. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X., & Leitner, D. M. (2005). Heat flow in proteins: computation of thermal transport coefficients. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 122(5), 54902. [CrossRef]

- Yu, W., & MacKerell, A. D. Jr. (2017). Computer-aided drug design methods. Methods in Molecular Biology, 1520, 85-106. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y., Wang, J., Chen, Z., Wang, G., Shao, Q., Shi, J., & Zhu, W. (2017). Structural insights into HIV-1 protease flap opening processes and key intermediates. RSC Advances, 7(71), 45121-45128. [CrossRef]

- Zavodszky, P., Kardos, J., Svingor, A., & Petsko, G. A. (1998). Adjustment of conformational flexibility is a key event in the thermal adaptation of proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 95(13), 7406-7411. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Q., Rajagopalan, P. T. R., Selzer, T., Benkovic, S. J., & Hammes, G. G. (2004). Single-molecule and transient kinetics investigation of the interaction of dihydrofolate reductase with NADPH and dihydrofolate. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101(9), 2764-2769. [CrossRef]

- Zurek, J., Foloppe, N., Harvey, J. N., & Mulholland, A. J. (2006). Mechanisms of reaction in cytochrome P450: hydroxylation of camphor in P450cam. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry, 4(21), 3931-3937. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).