1. Introduction

Inorganic pyrophosphatases (PPases, E.c. 3.6.1.1) catalyze metal-dependent hydrolysis of pyrophosphate PP

i to phosphate P

i. Soluble PPases (sPPases) are grouped into non-homologous structural Families I and II. In addition to sPPases, there are integral membrane enzymes of separate group (mPPases) that can couple PP

i hydrolysis with H

+ or Na

+ translocation through biological membranes. Soluble PPases are important housekeeping enzymes, their most known metabolic role is the thermodynamic pull of endergonic biosynthetic reactions that yield PP

i as a by-product [

1]. Among sPPases, Family I PPases are the most widely spread enzymes found in all domains of life; among them, enzymes from

Saccharomyces cerevisiae and

Escherichia coli are the best studied both structurally and functionally. In particular, there are crystal structures of several complexes of these enzymes representing consecutive stages of a catalytic reaction, which allowed the description of structural changes along the catalytic pathway [

2].

In animals, Family I PPases are solely responsible for PPase function. Human genome encodes two Family I PPases, hPPA1 and hPPA2. hPPA1 is a cytosolic enzyme [

3]; it is overly expressed in cancer cells where it promotes tumor development through several signaling pathways, and is considered a negative prognostic biomarker in gastric, colorectal, ovarian and other types of cancer [

4,

5,

6]. hPPA2 is a mitochondrial enzyme [

7]; its expression level is much lower than that of hPPA1, and its metabolic role is not yet clearly understood. Biallelic mutations in the nuclear gene

ppa2 encoding hPPA2 impair both respiratory and other metabolic functions of mitochondria which in most patients lead to early death of sudden cardiac arrest [

8,

9].

Numerous experimental data demonstrate that conformational changes are key for the catalytic activity of sPPases [

2,

10,

11]. In addition, several sPPases show allosteric properties in respect to the stationary kinetics of substrate hydrolysis which may be caused by the homotropic interaction between the active sites of oligomeric proteins or by the heterotropic effects of allosteric site(s) [

12]. Despite the potential significance of allosteric behaviour for the functional properties of sPPases, mechanisms of their regulation are poorly understood. ATP, metal-free PP

i, fructose-1-phosphate and L-malate were found to allosterically affect

in vitro activity of several procaryotic and yeast PPases or change their interaction with small-molecule ligands [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Dithiothreitol and other reduced thiols were found to affect the

in vitro activity of mutant form of human cytosolic hPPA1 forming less active monomer, presumably, through the reduction of an important cysteine residue restoring a dimeric structure of PPase [

17]. Eukaryotic PPases of yeast and plants were found to depend on phosphorylation both

in vivo and

in vitro [

18,

19,

20]. While phosphorylation did not affect pollen sPPase activity under optimal conditions, it significantly enhanced its sensitivity to inhibition by H

2O

2, Ca

2+ and low pH [

20]. In addition, eukaryotic PPases can be regulated at the transcription level: the age-dependent increase in cytosolic PPase expression level and concomitant increase in tissue PPase activity was demonstrated in rat liver [

21].

In our recent study, we solved the crystal structure of PPA2 enzyme from thermotolerant yeast

Ogataea parapolymorpha (OpPPA2) and characterized its mutant variant Met52Val corresponding to the pathogenic variant Met94Val of the human hPPA2 [

22]. This mutant variant retained the overall structure and stability but demonstrated critically impaired catalytic properties compared to the wild-type PPase. Several important functional parameters were affected, including catalytic constant, Michaelis constant, and enzyme affinity for cofactor Mg

2+. Mutated residue Met52 belonged to the protein hydrophobic core and had no obvious connection to the active site or other functional sites. Using structural analysis, we suggested that the reason of the observed effects was the impaired conformational flexibility of PPA2 due to the mutation of flexible methionine to shorter and more rigid branched-chain valine residue. In particular, we suggested that the mutation affected the transitions of the protein structural elements required for the formation of the attacking nucleophile.

In this work, we studied the conformational dynamics of hPPA2 using molecular dynamic simulation of its 3D structural model, and of hPPA1 using its crystal structure. Obtained data were analyzed by the Principal Component Analysis, Normal Mode Analysis and other approaches to visualize structural changes of the protein molecule in a solution. This analysis was performed on the wild-type hPPA2 as well as on the structural models of four mutant variants with point mutations corresponding to the pathogenic variants of hPPA2 from the ClinVar database [

23]. The results of this work allow the deeper insight into the structural basis of PPase function and the possible effects of pathogenic mutations on the protein structure and function. Our results will be useful in future research on the allosteric behaviour of PPases and possible mechanisms of their regulation and protein-protein interaction.

2. Materials and Methods

Model Preparation: 3D structure of hPPA2 was modelled using I-Tasser server (

https://zhanggroup.org/I-TASSER/, [

36]) based on the Uniprot (

https://www.uniprot.org/, [

37]) sequence Q9H2U2 (IPYR2_HUMAN). The mature form of a protein (residues 33-334) without N-terminal mitochondrial transfer peptide was used in modelling. Top-ranked 5 models produced by I-Tasser were analyzed for reliability using local quality criteria. The best ranked model had C-score 0.44 and TM-score of 0.66, and hPPA1 (PDB ID 6C45 [

30]) was recognized as best template. All models had the same protein fold and slightly differed only in the conformations of highly flexible chain fragments which were modeled with lowest confidence score (residues 71–90 and 242–249). All generated models had good scores in validation estimated by percentage of Ramachandran favored and unfavored residues, MolProbity score, and Clash Score, and were of high reliability. The best ranked model was used in further analysis. The obtained model of hPPA2 subunit was subsequently used to manually model dimeric hPPA2 in a holoform. For the holoform modeling, Mg

2+ at the sites M1 and M2 and coordination water molecules were adopted from the structure of the holoform of yeast PPase 1WGI [

29]. Dimer was generated by symmetry modelling using crystal structure of human cytoplasmic PPase hPPA1 (6C45 [

30]), from which crystallographic water molecules were also included. The hPPA2 variants (Ser61Phe, Met94Val, Met106Ile, Gln294Pro) were created by substituting respective residues for mutated ones in both subunits of the WT hPPA2 structure using UCSF Chimera [

38]. Model construction and validation were completed in COOT [

39]. All models were corrected manually by removing steric clashes with a 0.6 Å van der Waals overlap threshold, adjusting amino acid rotamers, correcting peptide bond angles to reduce Ramachandran outliers to five or fewer. Protonation states were assigned to the residues at pH 7.5 according to p

Ka values calculated using ProPka [

40]. Hydrogen atoms were added to the models using the H++ server. (

http://newbiophysics.cs.vt.edu/H++/, [

41]). Active site aspartate side chains were deprotonated manually if necessary. Molecular visualization and interactive model adjustments were performed in UCSF Chimera and VMD [

42].

System preparation and Molecular Dynamics Simulation: Molecular dynamics simulations were carried out using AmberTools22 [

43]. Each protein model was placed within a truncated octahedral water box. Solvent shells were placed around the protein models using placevent. K+ and Cl- ions were added to mimic 0.15 M KCl solution. Final solvent density estimated by 3D-RISM was of 55.5 mol/L. Amber was used for structure parametrization. Calculations were performed on a graphical station with 4 NVIDIA GeForce GTX Titan X graphics cards, operated under Ubuntu 14 with a CUDA 6.5 toolkit package. The prepared systems underwent simulations at 300 K and constant pressure. The temperature was kept constant using a Langevin thermostat, and the pressure (1.0 bar) was kept constant using a Berendsen barostat. System relaxation involved two-stage minimization in sander, first with constraints on protein atoms to relax solvent, then fully minimizing the system. Heating from 0 K to 300 K was achieved in 10000 steps with a 2 ps time step. Production simulations were then conducted subsequently for 50 ns using pmemd.cuda_SPFP, with non-bonded interactions calculated by a 10 Å cutoff. Each system was simulated twice for a cumulative 200 ns (WT hPPA2 and Met94Val) or 100 ns (rest of the proteins) per setup. Models were independently reassembled for each dynamics repeat.

Trajectory Analysis: Trajectory analysis was performed using CPPTRAJ, VMD and Python’s correlationplus. Data processing, visualization and analysis was performed using Python libraries including numpy, pandas, matplotlib, seaborn, scipy, correlationplus, and placevent.

Figures were made using UCSF Chimera [

38], VMD [

42] and SigmaPlot.

NMA analysis: Coarse-grained Normal Mode Analysis (NMA) was performed using portal DynOmics [

44]. This portal utilizes anisotropic network model (ANM) [

45] for molecular motions and animations and Gaussian network model (GNM) [

46] for the analysis of RMSF, cross-correlations between residue fluctuations, an inter-residue contact map, and properties of the GNM mode spectrum. Data were visualized using VMD or downloaded as the figures from the server.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of the Possible Effects of Pathogenic Mutations on hPPA2 Structure

In the ClinVar database, 374 natural variants of ppa2 gene with a number of variations are listed. Circa 200 of them are single-nucleotide variants, either missense or synonymous. Most of missense mutations of protein product are listed with the status of uncertain pathogenic significance, while 7 missense variants are classified as benign or likely benign, and 11 missense variants are classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic. The pathogenic variants in homo- or heterozygous biallelic combinations lead to cardiac failure of affected individuals. This work is the attempt to understand the molecular bases of the effects of pathogenic mutations on the structure and function of hPPA2.

In order to characterize the possible impact of mutations on protein structural stability, we calculated the predicted fold stability changes ΔΔG of hPPA2 using sequence-based variant of Strum algorithm (

https://zhanggroup.org/STRUM/about.html, [

24]). The values of changes in folding free energy, ΔΔG, were calculated for all possible mutations of all protein residues; the obtained values, as well as the mutation probability scores at the particular position, are listed in

Supplementary Table S1 for the pathogenic variants. The values are given for the particular pathogenic mutations found in affected patients; in addition, in order to visualize the overall importance of the studied position for the fold stability, the aggregated total values are given for mutations to other possible residues. Conservation scores for these positions were also calculated using ConSurf server (

https://consurf.tau.ac.il/consurf_index.php, [

25,

26]). Conservation fall all these positions are negative (

Supplementary Table S1) signifying that all of them evolve with lower rates than the average residue in this protein. The location of the mutated resdidues in the hPPA2 structure and their conservation scores are illustrated in

Figure 1. Most of the residues mutated in pathogenic variants are graded 8 or 9 by ConSurf algorithm which corresponds to highly conserved positions. These results suggest that mutations of Met94, Glu172 andnTrp202 to any residue should be destabilizing since aggregated ΔΔG for these residues have moderate but clearly negative values. The rest of pathogenic mutations show only slight, if any, destabilizing effect with positive or close to zero values of ΔΔG. Therefore, destabilization of a protein structure per se is probably not the primary cause of pathogenic effect of mutations. However, the effect of mutations on the protein structure could be revealed after the analysis of dynamic rather than static conformational states. That prompted us to study the conformational dynamics of hPPA2 using molecular dynamic simulation, coarse-grained NMA analysis and all-atom PCA analysis, and to identify the changes in the dynamic behavior of the protein caused by mutations.

3.2. Conformational Dynamics of hPPA2 Studied by Molecular Dynamics Simulation

3.2.1. General Characteristics

3D structure of hPPA2 is yet unknown; however, several crystal structures of eukaryotic Family I PPases are available in pdb and they all share a highly conserved global fold and dimeric organization. The structure of hPPA2 was therefore homology modelled in a holoform, optimized and prepared for the molecular dynamic simulations as described in the Materials and Methods. Family I PPases are metal-dependent enzymes with Mg

2+ being the best cofactor [

27,

28]. In the holoform, two Mg

2+ ions occupy the subsites M1 and M2 in the active site; this form is capable of binding substrate and subsequent catalysis [

2,

27,

29]. Positions of two Mg

2+ ions in hPPA2 were modelled using the holoform of yeast cytosolic PPA1 (PDB ID 1WGI [

30]) as a template. Since most eukaryotic PPases are functional as dimers, the dimeric form of hPPA2 was then generated using the crystal structure of human cytosolic PPase hPPA1 (PDB ID 6C45 [

31]) as a template. After minimization and heating to 300 K, two runs of molecular dynamic simulations were performed for 200 ns each. RMSD profiles for the wild-type hPPA2 are shown in

Supplementary Figure S1. The histograms of RMSD for the two subunits of a dimer are slightly different (

Figure S1, bottom plot); this result demonstrates that, although the original dimer of hPPA2 was generated from the identical subunits by their symmetry-related duplication, MD simulation induced subunit asymmetry in hPPA2. Superposition of the two subunits of dimers from the random frames along the trajectory gives an RMSD of 2.1-2.4 Å. The major variations (

Supplementary Figure S2) are observed in the regions of a chain 71-90, 121-128, 149-166, and 290-306. These parts of a chain are not directly involved in the intersubunit contact. The observed difference may be relevant to the allosteric properties of PPases where information is transferred from one subunit to another in the dimeric enzyme.

Supplementary Figure S3, A shows the all-atom RMSF analysis of hPPA2 trajectory after its equilibration. All-atom fluctuations are shown for subunits A and B of a dimer.

Figure 2 shows the hPPA2 dimer (average structure after equilibration) colored by RMSF. The most flexible chain fragments fluctuating with amplitude of 2.5 Å and higher include chain regions 71-90, 121-127, 152-161 and 295-320 (colored red in

Figure 2). The first region is an Ω-loop unique for the structure of mitochondrial PPases from animals. It is located at the protein surface and is not stabilized by the contacts with the main body of a protein. The coil regions 121-127 and 152-161 are located around the active site, contain the residues important for the catalysis and determine the “open” or “closed” state of the active site (discussed below). The extended region 295-320 is located close to the C-terminus of hPPA2 and contains a short helix; the residues of this region are mostly variable (

Figure 1). As expected, the most stable and least fluctuating residues (colored blue in

Figure 2) belong to the constituents of a β-barrel and elements stabilized by an intersubunit interaction. As in the homologous Family I PPases with known crystal structures, most of the active site residues belong to the stable β-strands involved in barrel formation, however, some active site residues (Arg127, Asp164, Asp201, Lys203) belong to less ordered structural elements and demonstrate moderate flexibility.

As demonstrated in the

Supplementary Figure S4 where the RMSF calculated for the different parts of an MD trajectory are shown, the RMSF profile only changes at the beginning of simulation, whereas after approximately the 100th frame the profiles are qualitatively similar.

3.2.2. Metal Coordination

Mg

2+ ions modelled at M1 and M2 sites are retained in both subunits for the entire course of simulation. The protein ligands of Mg

2+ in subunit A are carboxylic groups of Asp164, Asp169 and Asp201 as it was modelled in the original structure (

Figure 3, A). The side chains of Glu97, Glu107, Asp166 and Tyr142 as well as the peptide oxygen of Pro167 coordinate metal ions via water molecules. In subunit B, carboxylic oxygen atoms of Asp201 are approximately 4 Å from the metal ion and instead the fourth water molecule is coordinated to Mg

2+, while the other protein ligands are the same (

Figure 3B,

Supplementary Figure S5). Fluctuations of both metal ions around their mean positions are in the range of 0.6-0.7 Å (

Supplementary Figure S6), and the increase in the distance between M1B and Asp164 is due to the movement of the Asp164 side chain (

Figure 3, B). Conformational changes involving the movement of metal ions in the active site are of functional importance. In the holo-PPases, the two metal ions at M1 and M2 sites are connected by a two-water bridge; upon substrate binding, the metal ions get closer to each other, one of these two water molecules is expelled while the second water molecule becomes a bridging ligand and an attacking nucleophile [

2]. In the course of MD simulation, metal ions in both subunits do not come closer than 5.2 Å to each other (

Supplementary Figure S7), and they stay connected by a two-water bridge as in the original structure. In some frames, Cl

- is bound in the vicinity of Mg

2+, however, this is not enough to bring metal ions closer. Presumably, the formation of a one-water bridge requires binding of a larger anion (e.g. phosphate or pyrophosphate) that can coordinate both metal ions simultaneously and thus stimulate their movement to each other. The variation between Mg

2+ binding observed in the two subunits of hPPA2 reflects the difference in the position of the region II (residues 152-164), including Asp164 (

Figure 3, B), and the region III (residues 194-201), including Asp201. Positions of these regions are important for the dynamics of metal ions required for the catalysis, in particular, for the transition from the “open” to “close” conformation of the active site and the formation of the attacking nucleophile [

2]. The observed difference between the subunits may imply that the two subunits coordinate their dynamics in the course of catalysis.

3.2.3. Anionic Binding Site

In the preparation of protein model for the MD simulation, K

+ and Cl

- were used as counter-ions to mimic the physiological conditions. Analysis of the distribution of Cl

- in the simulation box demonstrates that they form a cluster within the protein active site where the probability to find Cl

- is significantly higher than at any other place in the box. In contrast, K

+ shows an even probability distribution without clustering.

Figure 4 shows a high-probability cluster of Cl

- ions in the active site in the vicinity of Mg

2+ ion M2. Such clustering of Cl

- at one place suggests the formation of a binding site for anionic ligands. Position of this cluster coincides with the position of pyrophosphate in the enzyme-substrate complex of a homologous PPase as observed in the crystal structure 2AUU ([

32],

Figure 4, B). We may propose therefore that the conformational dynamics of a holo-form of hPPA2 in a solution leads to the formation of a binding site which can be occupied by pyrophosphate as part of a substrate. It should be noted that this binding site manifested by Cl

- clustering was observed only in one subunit of a dimeric molecule (subunit B). Analogous clusters of Cl

- were found in some of the mutant variants of hPPA2 (see below). This observation therefore follows some pattern, though the structural basis for that remains yet to be understood.

3.2.4. Conformation of the Active Site Loops

For the two Family I cytosolic PPases, those from

E. coli (Ec-PPase) and

S. cerevisiae (Sc-PPase), the available crystal structures made it possible to analyze the conformational changes along the catalytic pathway [

2,

11,

31]. It was concluded that the enzyme can adopt either “open” conformation or “closed” conformation depending on the ligands bound in the active site [

2]. These conformations are manifested in particular by the position of the loops around the active site: for Sc-PPase they are regions 72-76, 103-115 and 147-152 [

2]. Some residues of the active site, including those coordinating metal ions and phosphate or pyrophosphate, are located at these regions. “Open” conformation corresponds to the holoform with two metal ions bound at the M1 and M2 sites; “closed” conformation corresponds to the PPase with three or four metal ions and pyrophosphate or one or two phosphates bound.

Figure 5 shows the superposition of the “open” and “closed” conformations as they were observed for the Sc-PPase (PDB ID: 2IHP, subunit A is “open” and subunit B is “closed” [

2]) with the representative conformation of hPPA2 after MD simulation. The loops determining “open” or “closed” state are shown in Sc-PPase by blue and cyan colors, respectively, and in hPPA2 the corresponding regions of a chain are highlighted in purple color. As expected, the conformation of hPPA2 is closer to the “open” state of Sc-PPase which is clearly seen for the regions 121-128 and 468-475 (labelled as I and III, respectively). These regions of a chain contain the residues Asp201, Asp196, Lys122, Lys125, Arg127 important for catalysis. Asp201 is the ligand of M1 and, together with Asp196, in the enzyme-substrate complex it is supposed to coordinate the substrate metal ion M3; Arg127 in the enzyme-substrate complex is supposed to coordinate pyrophosphate and, after hydrolysis, the phosphate P1; Lys122 and Lys125 are thought to contribute the release of phosphate P1 [

2]. In the observed conformations of hPPA2 the residues that are not involved in metal binding are involved in the interactions keeping these flexible regions in the “open” state. Asp196 is H-bonded to the conserved residue Asn250 and forms a salt bridge with Lys242; Arg127 forms a salt bridge with Asp245, and Lys125 – with Glu325. These bonds and salt bridges populate a large fraction of frames in the course of MD simulation. According to Oksanen et al. [

2], the transition from “open” to “closed” conformation upon substrate binding is accompanied by the formation of a salt bridge between Arg78 (corresponding to Arg127 in hPPA2) and Asp71 that would trigger the P1 phosphate release. In hPPA2, the residue corresponding to Asp71 is Tyr120, though there is an Asp123 in the vicinity that corresponds to Lys74 of Sc-PPase and theoretically it could form a salt bridge with Arg127. Another difference of the two structures is the position of a region 426-438 (labelled II in

Figure 5). In Sc-PPase, the “closed” position of this loop (shown cyan in

Figure 5) looks more open than the “closed” position (shown blue). In hPPA2 the loop (shown purple) is indeed more open despite that it resembles the “closed” state of Sc-PPase. This loop is one of the most flexible regions in hPPA2, with RMSF of over 2 Å for some residues (

Figure S3). The fragment 159-170 containing catalytically important residues Asp164 (ligand of M1) and Asp169 (the residue assisting in formation of attacking nucleophile) is connected with the rest of the protein only by the H-bond between Cys161 and Glu199, and through metal ion or water molecules. The motion of this flexible region of a chain has probably the largest impact on the motion of M1 required for the one-bridging water state of the active site. In agreement with this suggestion, the side chain of Asp164 in some frames along the MD trajectory moves out of coordination sphere of a metal ion, as far as 4 Å from M1, and becomes a second-coordination shell ligand. This type of fluctuation is probably part of a conformational change bringing protein to a “closed” position after substrate binding.

3.2.5. PCA Analysis of MD Trajectory

Conformational space of hPPA2 in the course of MD simulation was characterized using Principal Component Analysis (PCA). This approach allows the transformation of a multidimensional system (e.g. the MD trajectory) into a lower-dimensional space using a special coordinate system of orthogonal vectors. Projections of the data onto these coordinates are principal components which extract the most essential information on the variations existing in the system. PC1 (principal component 1) corresponds to the greatest variance, PC2 – to the next greatest variance, etc. In particular, principal components in the MD analysis allow to describe the most essential (in terms of amplitude) motions of the molecule, while the plot of PC2 against PC1 allows some clustering of the possible conformations in the observed space.

Figure 6 shows this plot for the WT hPPA2. The space of conformations observed along the trajectory can be grouped into two clusters with population density higher than average (clusters I and II in

Figure 6, A, green or yellow symbols), and in addition there is a lot of separate states not forming dense clusters (blue symbols). PCA analysis was performed using the entire simulation time; in order to visualize the transitions between conformations in the course of simulation, the same data are presented in

Figure 6, B with color scheme corresponding to a frame of trajectory: from the beginning 100 frames (blue symbols) to the final 100 frames (purple symbols). This analysis suggests that in the course of MD simulation the constant drift is observed from one group of conformations to another group, then at some point in the middle of simulation the structure stays at more populated cluster II and finally it comes to a most populated cluster I and does not drift further. Cluster analysis of the trajectory using K-means or Dbscan approaches is in a good agreement with these results and allows to extract the representative structures corresponding to clusters I and II.

PCA analysis of the MD simulation was used to describe the all-atom motion of hPPA2 along the trajectory.

Figure 7, A shows which parts of a molecule contribute most into a PC1, i.e. the highest-amplitude motion. Directions of their oscillation are visualized on a porcupine plot (

Figure 7, B) by purple arrows. According to these calculations, PC1 involves several regions of a protein including the Ω-loop 71-90 and the flexible regions I (121-128) and II (155-161) around the active site. In addition, the loop 53-58 and the region 300-311 also contribute to PC1 motion. The predominant character of conformational changes in PC1 is a rocking motion of subunits causing the shift of these atoms in the observed directions.

3.2.6. NMA Analysis of hPPA2 Conformational Dynamics

A Normal Mode Analysis, or NMA, is widely used to characterize the short-time conformational dynamics of a protein around an equilibrium position (reviewed recently in [

33]). In order to analyze the general dynamical behavior of hPPA2, NMA was performed by the DynOmics server (

http://gnm.bahargroup.org/ [

34]) for the coarse-grained model of hPPA2, i.e. for the protein CA trace. Global low-frequency modes 1-3 of a protein motion calculated by this method are shown in

Figure 8. The first two modes involve the motion of subunits in respect to each other: mode 1 (the slowest mode) is the rocking motion of subunits, mode 2 is the twisting motion of the subunits around the line connecting their centers. Modes 2 and 3 also involve the nodding and twisting motions of an Ω-loop 71-90. Mode 1 is highly collective and has a high value of a parameter 1/λ (corresponding to a very low frequency) suggesting that the observed mode 1 of conformational oscillation may be functionally important. Modes 2 and 3 have lower “collectivity” parameter meaning that they involve mostly local elements of a chain (according to

Figure 8, the key player in these modes is an Ω-loop 71-90). Description of conformational dynamics of hPPA2 obtained by this method is in a good agreement with the results of a PCA analysis of MD trajectories. PC1 determined from PCA analysis is composed of elements of all global modes 1 and 2.

NMA analysis performed on the hPPA2 structures corresponding to several different frames of an MD trajectory, average structure after equilibration and the original model before MD simulation demonstrate that in all these structures the global type of conformational changes is the same (

Supplementary Figure S8). Predominant type of motion is the rocking of subunits, and additionally the motion of an Ω-loop can be sensed in lesser and varying degree. This result is in agreement with the similar profiles of RMSF obtained for different frames (

Figure S4).

Analogous NMA analysis performed on the crystal structure of a cytosolic PPase hPPA1 (PDB ID: 6C45 [

30]) demonstrates that the few lowest-frequency global modes generally describe the same type of motion in the two human PPases, hPPA1 and hPPA2 (

Supplementary Figure S9). However, hPPA1 lacks the Ω-loop 71-90 which in hPPA2 actively participates in the motion determined by modes 2 and 3, and the calculated modes do not exactly correspond one-to-one to each other in these two PPases. The rocking motion of the subunits described by the mode 1 is very similar also in other dimeric PPases as exemplified by a cytosolic PPases from

S. cerevisiae and

Schistosoma japonicum (

Supplementary Figure S10).

The oscillation of subunits found in dimeric PPases may be relevant to the information transfer between the two active sites of a dimer. In addition, this type of motion creates the dynamic binding pockets between the subunits opening and closing and adopting various conformations in the course of PPase oscillation. Possible ligand binding in these pockets may impede the motion of subunits and fix one of the conformational states. Therefore, this observed type of motion may represent the basis for the allosteric regulation of PPase function by effectors binding at the subunit interface.

3.3. Effect of Pathogenic Mutations on Conformational Dynamics of hPPA2

Molecular dynamic simulation was performed on the models of mutant variants of hPPA2 carrying the mutations analogous to the pathogenic natural variants Ser61Phe, Met94Val, Met106Ile, and Gln294Pro. All these proteins were modelled in holoform analogous to the wild-type hPPA2 (

Supplementary Figure S11). Analysis of their structures obtained after equilibration demonstrates that these proteins retain the global structure typical for the WT hPPA2. However, their conformational dynamics demonstrates several differences compared to the WT enzyme. First, some mutations cause the change in the global flexibility of the protein.

Supplementary Figure S3 shows the RMSF profiles of the mutant variants. Statistical analysis demonstrates that the variant Met94Val has the negative median value ΔRMSF of -0.52 Å compared to the WT PPase meaning that this protein is more rigid than the WT enzyme. Other mutant variants have the positive values of median ΔRMSF of 1.15-1.65 Å compared to the WT PPase which means that their structures are more flexible.

Analysis of the total amount of H-bonds in the dimeric proteins over the time course after equilibration shows that the Met94Val variant has on average more H-bonds than the WT hPPA2 (138 against 134), Gln294Pro variant – significantly fewer H-bonds (121 against 134), and the variants Ser61Phe and Met106Ile have similar or slightly decreased count of H-bonds compared to the WT protein (131 and 132, respectively).

The results of a PCA analysis of the MD trajectories of the mutant variants are in a good agreement with this conclusion. The values of PC1 (

Table 1) for Ser61Phe, Gln294Pro and Met106Ile, as well as PC2 for the first two variants, are higher than for the WT hPPA2 which means that the protein motion along these principal components is more pronounced in the mutants than in the WT enzyme. For the Met94Val variant the values of PC1 and PC2 are similar to the WT hPPA2 meaning that the overall conformational dynamics for this mutant is of the similar degree. For Met106Ile variant the motion along PC2 is less pronounced.

The plots of PC2 against PC1 for the mutant variants are shown in the

Supplementary Figure S12. It can be seen that for Gln294Pro and especially Ser61Phe the plots have higher dispersion around the most populated cluster which suggests that these proteins are less ordered than the WT PPase. For Gln294Pro the character of the plot suggests the increased flexibility of some local structural element rather than the overall structure. Analysis of the RMSF profiles (

Figure S3) suggests that these regions with larger fluctuations may be region II (residues 152-164) and the chain fragment 280-320. The Met94Val and Met106Ile variants have the compact and dense major clusters, and in Met94Val it is disconnected from the rest of the points which can be interpreted as the more rigid structure with more difficult transitions between the available conformational states. Ser61Phe also forms two different clusters but the intermediate points between them are more populated than in Met94Val. In Met106Ile the intermediate states are as much populated as in the WT PPase which suggests that the transitions between conformational states are not impaired in this variant.

The impact of mutations on the regions of the protein molecule important for the active site dynamics in the course of catalysis can be seen in

Supplementary Figure S6. Mutation Met106Ile decreases RMSF of the region I almost twofold compared to the WT PPase. Mutation Met94Val affects both regions I and II, though in lesser degree. In contrast, mutation Ser61Phe makes regions I and III more flexible. In the variant Gln294Pro, the RMSF of the region II is increased by 20%.

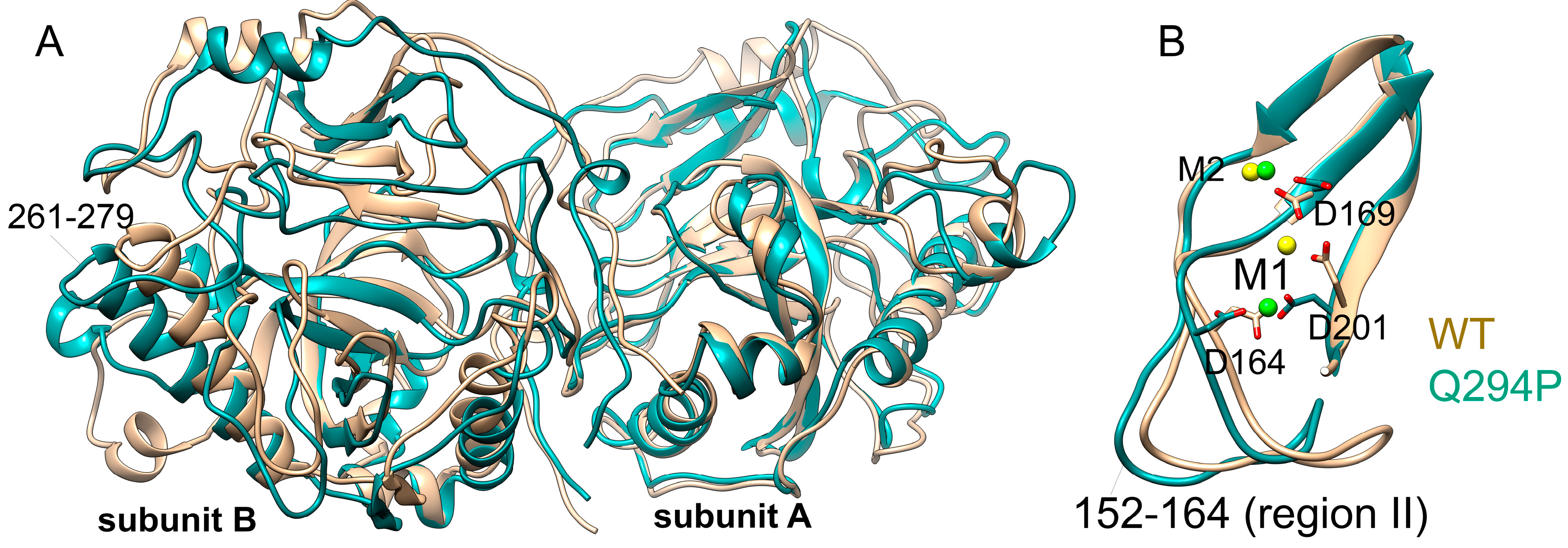

Positions of the metal ions in the mutant variants Ser61Phe, Met94Val and Met106Ile are virtually the same as in the WT PPase, considering their self-fluctuations; in contrast, in the Gln294Pro variant the M1 metal ion in subunit B oscillates between the two positions one of which is 5.6 Å apart from the conventional binding site (

Figure 9,

Figure S6). In the dimer of Gln294Pro superimposed to WT hPPA2 one subunit significantly deviates from its position of the WT protein as can be seen, for instance, from the different positions of the α-helices 261-279 (

Figure 9, A). Conformation of a protein chain region II (residues 152-164) is also different in the Gln294Pro where it adopts even more open conformation than in the WT protein, in addition to its larger RMSF values (

Figure S6); this difference may cause the observed variations in the M1 position.

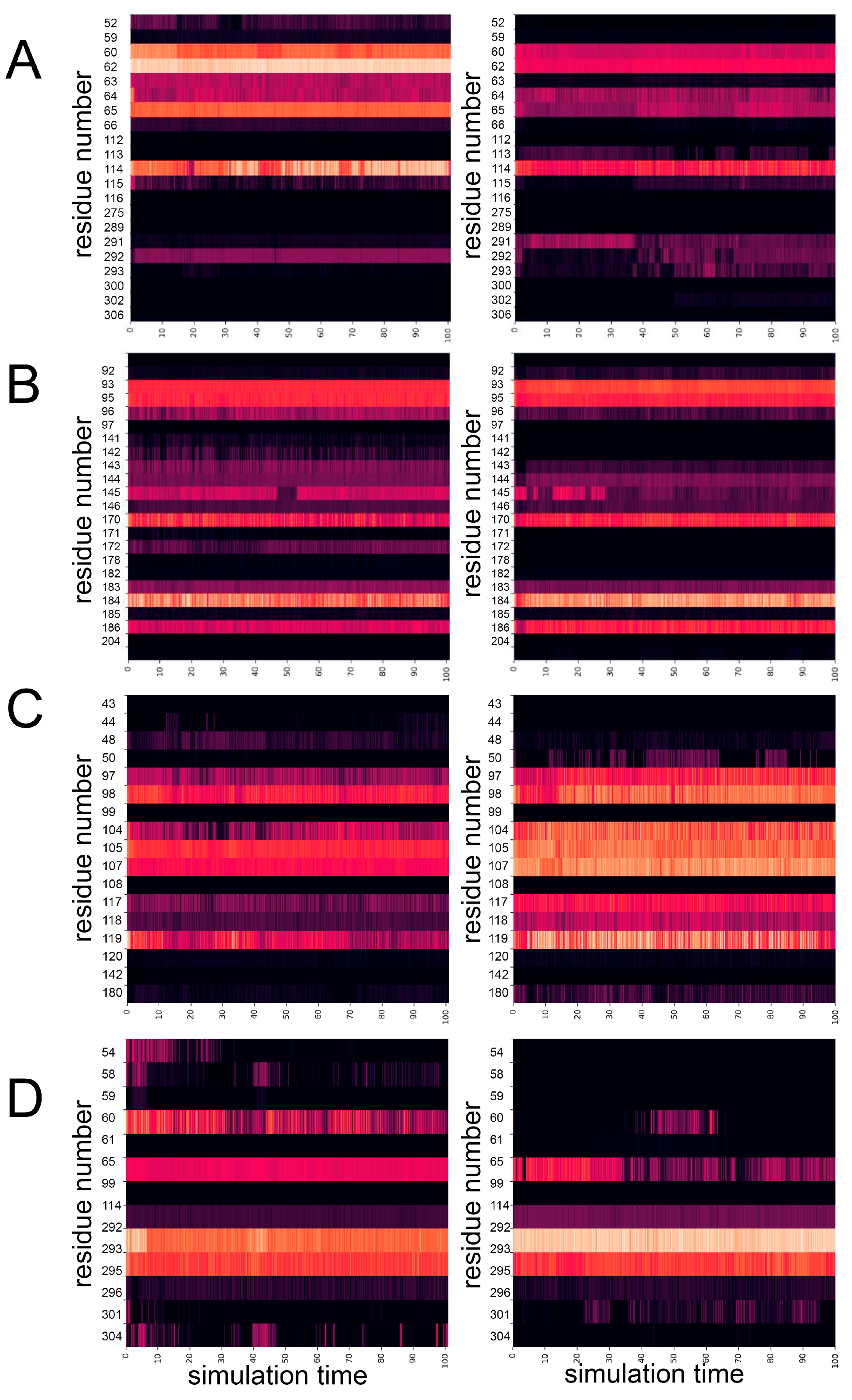

Another difference observed in the dynamics of the mutant variants is the change in the character and density of non-covalent interactions of the regions of protein in the vicinity of the mutation site.

Figure 10 shows heatmaps of the contact density of the mutated residues in the structures of WT PPase and mutant variants calculated as the number of atoms that can be found within 5 Å of mutated residue over the MD trajectories. It can be seen that for all mutant PPases mutation causes drastic changes in the observed heatmaps. For example, Ser61 in the WT hPPA2 has connections with the residues 60, 62, 63, 65, 114, 292 and the number of these connections are significantly decreased after mutation. On the other hand, the total number of diffused connections with the region 291-293 and in particular with the residue Thr291 is increased. In turn, Gln294Pro variant as a result of mutation loosens connections with the residues 54-61, though the possible impact of this for PPase function is unclear. In the mutant variant Met106Val the connection density of mutated residue is significantly increased, this includes the regions 97-98, 104-107 and 117-119. In the case of Met94Val the general picture is not as clearly demonstrated;

However, connections are lost with the regions 142-143 and 96-97 which can be important for the catalytic performance of PPase, since both Glu97 and Tyr142 are the active site residues participating in the metal ion M2 and/or substrate binding. In contrast, the residues 170 and 186 increase the density of connections in Met94Val which can be related to the decreased flexibility of this mutant variant. Asp169 preceding Val170 in the sequence is the ligand of metal ion M1, the neighboring residues Asp166 and Pro167 are important for the formation of the attacking nucleophile. Decreased flexibility of this structural element may impair the movements required for this stage of catalysis.

We performed NMA analysis of the global motion of the mutant PPases and expected that it would not show significant differences from the WT hPPA2, since this approach was performed in the coarse-grained variant and the mutant PPases retain the overall structure typical for the WT hPPA2. In Ser61Phe and Met94Val, mode 1 is indeed the same type of motion as in the WT PPase though in mutants the motion is more intense and involves additional structural elements. However, some variations were observed for the mutant variants Met106Ile and Gln294Pro variants (

Supplementary Figure S13). In Gln294Pro variant, mode 1 includes the intense motion of the Ω-loop, and the mode 2 is similar to the mode 1 of the WT PPase. In Met106Ile, mode 1 includes only Ω-loop, while the motion of subunits is involved in modes 2 and 3. These changes are subtle but they can be taken into consideration when the functional properties of mutant variants will be studied.

4. Discussion

The principal objective of our work is the characterization of mitochondrial human PPase, hPPA2, in the attempt to understand the molecular bases of the pathogenic effects of natural mutations leading to severe mitochondrial disfunction. This particular study is aimed at the characterization of the conformational dynamics of hPPA2 in the solution and the effect of pathogenic mutations on the observed patterns. There is a number of crystal structures of Family I PPases, both from prokaryotes and eukaryotes, but the solution structure is not yet known, so our understanding of the dynamic behavior of PPases is based solely on the comparative analysis of crystal structures in various complexes. This analysis demonstrates that the slight variations in the static structure caused by single-residue mutations cannot completely explain the changes in functional properties of PPases. Therefore, it is probably more informative to characterize the effects of mutations on the structure and function of PPases using the analysis of conformational dynamics. In order to fill this gap, we applied a number of computational approaches to describe the dynamic behavior of hPPA2 and four of its mutant variants corresponding to natural pathogenic variants. We performed molecular dynamic simulations of these proteins in solution; PCA analysis of the MD trajectories; and NMA analysis of the coarse-grained models. The proteins were characterized in the holoform, i.e. as complexes with the two cofactor Mg2+ ions bound in each subunit of a dimer.

Analysis of the possible impact of the mutations on the protein stability showed that only three of the 11 pathogenic variants (Met94Val, Glu172Lys and Trp202Cys) are supposed to be less stable than the WT PPase. The changes in folding energy are moderate and are not expected to significantly impair protein folding or thermostability. The mutant variant Met52Val of PPA2 from yeast

Ogataea parapolymorpha (OpPPA2) corresponding to the Met94Val variant of hPPA2 had the same thermostability that the WT enzyme [

22]. In agreement with that, the characterization of the conformational dynamics of the mutant PPases demonstrated that they retain the overall structure typical for the WT hPPA2, although with slight variations, and that this structure is stable over the course of MD simulation. Variations of the conformational stability were observed for the variants Ser61Phe and Gln294Pro that demonstrated larger fluctuations around the equilibrium state compared to the WT hPPA2. In addition, Glu294Pro variant had the fewer H-bonds stabilizing protein structure that can imply lower thermo- and conformational stability. On the other hand, even slight changes in the global fold or the arrangement of surface structural elements can affect the interaction of PPases with cell partners, including proteases, so the predicted moderate changes in ΔΔG can affect the proteolytic stability of mutant variants or their recognition by cell degrading systems. Therefore, the stability of mutant PPases in the cell cannot be reliably predicted, and the decreased stability as the cause of mitochondrial disfunction cannot be completely ruled out.

Another possible reason for the pathogenic effect of these mutations is their catalytic incompetence as PPases. The residues mutated in the variants studied in this work are not located in the active site and do not have obvious connection to the PPase activity. However, most of pathogenic mutants of hPPA2 were earlier shown to be less active or completely inactive despite the location of the mutated residues [

8,

9,

35]. Our results shed some light on this phenomenon. Characterization of the conformational dynamics of the WT hPPA2 in holoform confirmed that the flexible regions I-III around the active site adopt the “open” conformation suggested for the Sc-PPase from the analysis of the crystal structures [

2]. Transition to the “closed” conformation necessary for the formation of the attacking nucleophile requires the certain flexibility of the regions I-III. Met94Val is the example of the variant where the region II is too strictly fixed due to the additional connections between the residues of this region and the mutated residue. The conformational changes required for the formation of the attacking nucleophile can be negatively affected in this mutant which would significantly decrease the catalytic activity, as it was found for the Met52Val variant of OpPPA2 [

22]. To the contrast, the catalytically important residues Tyr142 and Glu97 that require firm anchoring in the hydrophobic core get less ordered upon mutation of Met94 to the Val with shorter side chain. As a result, the catalytic activity of Met94Val can be further decreased due to the impaired affinity for the cofactor or substrate. The examples of the opposite effect on protein dynamics are Ser61Phe and Gln294Pro. They demonstrate enhanced flexibility up to the disordered character of motion which can impair the pre-organization of the active site required for the effective catalysis. In the Gln294Pro, some regions are overly flexible including the region II (residues 152-164) that presumably determines the correct functioning of the system regulating the transition between the “open” and “closed” conformations of the active site. In this mutant the system malfunctions and the M1 metal ion is positioned incorrectly. Therefore, impaired cofactor binding is predicted for this variant that in turn would affect all consecutive stages of catalysis.

The characterization of the dynamic properties of hPPA2, in addition to the aspects related to the effects of mutations on this particular enzyme, allowed some findings related globally to the function of PPases. The global character of motion of various dimeric PPases was identified; both the all-atom PCA analysis on MD trajectories and the coarse-grained NMA analysis on different conformations of hPPA2 and homologous PPases demonstrated that the most prominent and the lowest-frequency mode protein motion is the rocking motion of the subunits that in the case of hPPA2 is accompanied at various degrees by the motion of the Ω-loop 71-90. Subunit type of motion is globally important for dimeric PPases, it can be relevant to the cooperative effects of subunits or the allosteric regulation of dimeric PPases by cell effectors of various nature binding at the subunit interface. The motion of the Ω-loop is supposed to be of local effect for hPPA2 and other animal mitochondrial PPases; probably, this motion is relevant to the interaction of PPA2 with small molecule ligands or protein partners.

Another finding that seems to be relevant to the PPases as a group is the binding site for the anionic ligands that was absent in the original structure but formed in the course of molecular dynamics, in particular, as a result of metal dynamics at the site M1. This finding may be relevant to the PPase catalysis in general since it shows the spontaneous formation of the binding site in the exact position where pyrophosphate is bound in the enzyme-substrate complex. This site was found in one subunit of a dimer, confirming the inequality of subunits induced by dynamics.

In conclusion, our results provide a novel information on the PPase catalysis in general and effects of pathogenic mutations on hPPA2 in particular. In addition, this work provides a basis for the further study of PPase dynamics and the understanding of molecular mechanisms of PPase function in norm and pathology.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1. Predicted effect of the pathogenic mutations on the hPPA2 fold stability calculated using Strum [

24]; Figure S1. RMSD analysis of hPPA2; Figure S2. Superposition of subunits A (shown in yellow) and B (shown in pink) from several random frames of an MD trajectory after equilibration; Figure S3. RMSF profile of hPPA2 and its mutant variants; Figure S4. RMSF profile of subunit A of hPPA2 calculated for the different parts of a trajectory; Figure S5. The distances from metal ions M1 and M2 in subunits A and B to their protein ligands; Figure S6. (A) RMSF of the regions I (residues 121-125), II (residues 152-164) and III (residues 189-201) in the course of simulation. (B) RMSF of the metal ions M1 and M2 in subunits A and B in the course of simulation; Figure S7. The distances between metal ions M1 and M2 in the WT hPPA2 and the mutant variants; Figure S8. Mode 1 of the NMA analysis calculated for the hPPA2 structure at random frames of the MD simulation; Figure S9. Modes 1-3 of the NMA analysis calculated for hPPA2 (average structure after equilibration) and hPPA1 (6c45 [

31]); Figure S10. Mode 1 of the NMA analysis calculated for the crystal structures of different PPases; Figure S11. Total RMSD of dimeric molecules of the mutant variants of hPPA2 (top plot) and histograms of their distribution for the subunits A (blue lines) and B (pink lines); Figure S12. PCA analysis of the MD trajectory of mutant variants of hPPA2; Figure S13. NMA analysis of mutant variants of hPPA2.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.R.; Data curation, E.B., S.K. and N.V.; Formal analysis, E.B. and E.R.; Investigation, E.B., S.K., N.V. and E.R.; Project administration, S.K. and E.R.; Resources, N.V. and E.B.; Visualization, E.B. and E.R.; Writing – original draft, E.B. and E.R.; Writing – review & editing, E.B., S.K., N.V. and E.R.

Funding

This research was funded by the Russian Science Foundation (grant No. 23-24-00177).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The data are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. V. Anashkin (Moscow State University, Russia) for the help with the computational facilities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

PPi, inorganic pyrophosphate; Pi, inorganic phosphate; PPases, inorganic pyrophosphatases; sPPases, soluble PPases; mPPases, membrane PPases; PPA1, cytosolic pyrophosphatases; PPA2, mitochondrial pyrophosphatases; hPPA1, human cytosolic pyrophosphatase; hPPA2, human mitochondrial pyrophosphatase; Sc-PPase, cytosolic pyrophosphatase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae; Ec-PPase, cytosolic pyrophosphatase from Escherichia coli; OpPPA2, mitochondrial pyrophosphatase from yeast Ogataea parapolymorpha

References

- Heinonen J.K. Biological role of inorganic pyrophosphate, Kluwer Academic Publishers Inc., 2001.

- Oksanen, E.; Ahonen, A.K.; Tuominen, H.; Tuominen, V.; Lahti, R.; Goldman, A. et al. A complete structural description of the catalytic cycle of yeast pyrophosphatase. Biochemistry, 2007, 46, 1228 – 1239. [CrossRef]

- Fairchild, T.A.; Patejunas, G. Cloning and expression profile of human inorganic pyrophosphatase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1999, 1447, 133 – 136. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Cai, J.; Yin, J.; Wang, D.; Bai, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, K.; Yu, G.; Zhang, Z. Inorganic pyrophosphatase (PPA1) is a negative prognostic marker for human gastric cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015, 8, 12482-90.

- Wang, S.; Wei, J.; Li, S.; Luo, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Shen, W.; Luo, D.; Liu, D. PPA1, an energy metabolism initiator, plays an important role in the progression of malignant tumors. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1012090. [CrossRef]

- Niu, T.; Zhu, J.; Dong, L.; Yuan, P.; Zhang, L.; Liu, D. Inorganic pyrophosphatase 1 activates the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling to promote tumorigenicity and stemness properties in colorectal cancer. Cellular Signalling, 2023, 108, 110693. [CrossRef]

- Curbo, S.; Lagier-Tourenne, C.; Carrozzo, R.; Palenzuela, L.; Lucioli, S.; Zhirano, M.; Santorelli, F.; Arenas, J.; Karlsson, A.; Johansson, M. Human mitochondrial pyrophosphatase: cDNA cloning and analysis of the gene in patients with mt DNA depletion syndromes. Genomics, 2006, 87, 410 –416. [CrossRef]

- Guimier, A.; Gordon, C.T.; Godard, F.; Ravenscroft, G.; Oufadem, M.; Vasnier, C.; Rambaud, C.; Nitschke, P.; Bole-Feysot, C.; Masson, C.; Dauger, S.; Longman, C.; Laing, N.G.; Kugener, B.; Bonnet, D.; Bouvagnet, P.; Di Filippo, S.; Probst, V.; Redon, R.; Charron, P.; Rötig, A.; Lyonnet, S.; Dautant, A.; de Pontual, L.; di Rago, J.P.; Delahoyde, A.; Amiel, J. Biallelic PPA2 mutations cause sudden unexpected cardiac arrest in infancy. American Journal of Human Genetics, 2016, 99, 666 – 673. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, H.; Haack, T.B.; Hartill, V.; Matakoviс, L.; Baumgartner, E.R.; Potter, H.; Mackay, R.; Alston, C.L.; O'Sullivan, S.; McFarland, R.; Connolly, G.; Gannon, C.; King, R.; Mead, S.; Crozier, I.; Chan, W.; Florkowski, C.M.; Sage, M.; Höfken, T.; Alhaddad, B.; Kremer, L.S.; Kopajtich, R.; Feichtinger, R.G.; Sperl, W.; Rodenburg, R.J.; Minet, J.C.; Dobbie, A.; Strom, T.M.; Meitinger, T.; George, P.M.; Johnson, C.A.; Taylor, R.W.; Prokisch, H.; Doudney, K.; Mayr, J.A. Sudden cardiac death due to deficiency of the mitochondrial inorganic pyrophosphatase PPA2. American Journal of Human Genetics, 2016, 99, 674 – 682. [CrossRef]

- Moiseev, V.M.; Rodina, E.V.; Kurilova, S.A.; Vorobyeva, N.N.; Nazarova, T.I.; Avaeva, S.M. Substitutions of glycine residues Gly100 and Gly147 in conservative loops decrease rates of conformational rearrangements of Escherichia coli inorganic pyrophosphatase. Biochemistry (Moscow), 2005, 70, 858–866.

-

Rodina, E.V. Structural aspects of Family I inorganic pyrophosphatases. Protein Structures: Kaleidoscope of Structural Properties and Functions (Uversky, V.N., ed.). Research Signpost Kerala, India, 2003, 627–650.

- Avaeva, S.M. Active site interactions in oligomeric structures of inorganic pyrophosphatases. Biochemistry (Moscow), 2000, 65, 361-372.

- Baykov, A.A.; Pavlov, A.R.; Kasho, V.N.; Avaeva, S.M. Allosteric regulation of yeast inorganic pyrophosphatase by substrate. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1989, 273, 301-308. [CrossRef]

- Rodina, E.V.; Vorobyeva, N.N.; Kurilova, S.A.; Sitnik, T.S.; Nazarova, T.I. ATP as effector of inorganic pyrophosphatase of Escherichia coli. The role of residue Lys112 in binding effectors, Biochemistry (Moscow), 2007, 72, 100–108. [CrossRef]

- Vorobyeva, N.N.; Kurilova, S.A.; Anashkin, V.A.; Rodina, E.V. Inhibition of Escherichia coli inorganic pyrophosphatase by fructose-1-phosphate. Biochemistry (Moscow), 2017, 82, 953–956.

- Romanov, R.; Kurilova, S.; Baykov, A.; Rodina, E. Effect of structure variations in the inter-subunit contact zone on the activity and allosteric regulation of inorganic pyrophosphatase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochemistry (Moscow), 2020, 85, 326–333.

- Zheng, S.; Zheng, C.; Chen, S.; Guo, J.; Huang, L.; Huang, Z.; Xu, S.; Wu, Y.; Li, S.; Lin, J.; You, Y.; Hu, F. Structural and biochemical characterization of active sites mutant in human inorganic pyrophosphatase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - General Subjects, 2024, 1868, 130594. [CrossRef]

- Vener, A.V.; Smirnova, I.N.; Baykov, A.A. Phosphorylation of rat liver inorganic pyrophosphatase by ATP in the absence and in the presence of protein kinase. FEBS Lett. 1990, 264, 40–42.

- De Graaf, B.H.J.; Rudd, J.J.; Wheeler, M.J.; Perry, R.M.; Bell, E.M.; Osman, K.; Franklin, F.C.H.; Franklin-Tong, V.E. Self-incompatibility in Papaver targets soluble inorganic pyrophosphatases in pollen. Nature, 2006, 444, 490–493.

- Eaves, D.J.; Haque, T.; Tudor, R.L.; et al. Identification of Phosphorylation Sites Altering Pollen Soluble Inorganic Pyrophosphatase Activity. Plant Physiol. 2017, 173, 1606-1616.

- Panda, H.; Pandey, R.S.; Debata, P.R.; Supakar, P.C. Age-dependent differential expression and activity of rat liver cytosolic inorganic pyrophosphatase gene. Biogerontology, 2007, 8, 517-525. [CrossRef]

- Bezpalaya, E.Y.; Matyuta, I.O.; Vorobyeva, N.N.; Kurilova, S.A.; Oreshkov, S.D.; Minyaev, M.E.; Boyko, K.M.; Rodina, E.V. The crystal structure of yeast mitochondrial type pyrophosphatase provides a model to study pathological mutations in its human ortholog. Biochem. and Biophys. Res. Comm., 2024, 738, 150563. [CrossRef]

- Landrum, M.J.; Lee, J.M.; Benson, M.; Brown, G.R.; Chao, C.; Chitipiralla, S.; Gu, B.; Hart, J.; Hoffman, D.; Jang, W.; Karapetyan, K.; Katz, K.; Liu, C.; Maddipatla, Z.; Malheiro, A.; McDaniel, K.; Ovetsky, M.; Riley, G.; Zhou, G.; Holmes, J.B.; Kattman, B.L.; Maglott, D.R. ClinVar: improving access to variant interpretations and supporting evidence. Nucleic acids research, 2018, 46(D1), D1062 –D1067. [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.; Lv, Q.; Zhang, Y. STRUM: Structure-based stability change prediction upon single-point mutation. Bioinformatics, 2016, 32, 2911-2919.

- Ashkenazy, H.; Abadi, S.; Martz, E.; Chay, O.; Mayrose, I.; Pupko, T.; Ben-Tal, N. ConSurf 2016: an improved methodology to estimate and visualize evolutionary conservation in macromolecules. Nucl. Acids Res. 2016, 44(W1), W344–W350. [CrossRef]

- Yariv, B.; Yariv, E.; Kessel, A.; Masrati, G.; Ben Chorin, A.; Martz, E.; Mayrose, I.; Pupko, T.; Ben-Tal, N. Using evolutionary data to make sense of macromolecules with a 'face-lifted' ConSurf. Protein Science, 2023, 32, e4582. [CrossRef]

- Baykov, A.A.; Shestakov, A.S. Two pathways of pyrophosphate hydrolysis and synthesis by yeast inorganic pyrophosphatase. Eur. .J Biochem. 1992, 206, 463-470. [CrossRef]

- Zyryanov, A.B.; Shestakov, A.S.; Lahti, R.; Baykov, A.A. Mechanism by which metal cofactors control substrate specificity in pyrophosphatase. Biochem. J. 2002, 367, 901-906. [CrossRef]

- Samygina, V. Inorganic pyrophosphatases: structural diversity serving the function. Russ. Chem. Rev., 2016, 85, 464. [CrossRef]

- Heikinheimo, P.; Lehtonen, J.; Baykov, A.; Lahti, R.; Cooperman, B.S.; Goldman, A. The structural basis for pyrophosphatase catalysis. Structure, 1996, 4, 1491-1508. [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Zhu, J.; Qu, Q.; Zhou, X.; Huang, X.; Du, Z. Crystallographic and modeling study of the human inorganic pyrophosphatase 1: A potential anti-cancer drug target. Proteins, 2021, 89, 853 – 865. [CrossRef]

- Samygina, V.R.; Moiseev, V.M.; Rodina, E.V.; Vorobyeva, N.N.; Popov, A.N.; Kurilova, S.A.; Nazarova, T.I.; Avaeva, S.M.; Bartunik, H.D. Reversible Inhibition of Escherichia coli Inorganic Pyrophosphatase by Fluoride: Trapped Catalytic Intermediates in Cryo-crystallographic Studies. J. Mol. Biol., 2007, 366, 1305-1317. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.A.; Pavlović, J.; Bauerová-Hlinková, V.; Normal Mode Analysis as a Routine Part of a Structural Investigation. Molecules, 2019, 24, 3293. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chang. Y.Y.; Lee, J.Y.; Bahar, I.; Yang, L.W. DynOmics: Dynamics of structural proteome and beyond. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W374–W380. [CrossRef]

- Guimier, A.; Achleitner, M. T.; Moreau de Bellaing, A.; Edwards, M.; de Pontual, L.; Mittal, K.; Dunn, K. E.; Grove, M. E.; Tysoe, C. J.; Dimartino, C.; Cameron, J.; Kanthi, A.; Shukla, A.; van den Broek, F.; Chatterjee, D.; Alston, C. L.; Knowles, C. V.; Brett, L.; Till, J. A.; Homfray, T.; French, P.; Spentzou, G.; Elserafy, N.A.; Lichkus, K.S.; Sankaran, B.P.; Kennedy, H.L.; George, P.M.; Kidd, A.; Wortmann, S.B.; Fisk, D.G.; Koopmann, T.T.; Rafiq, M.A.; Merker, J.D.; Parikh, S.; Ahimaz, P.; Weintraub, R.G.; Ma, A.S.; Turner, C.; Ellaway, C.J.; Phillips, L.K.; Thorburn, D.R.; Chung, W.K.; Kana, S.L.; Faye-Petersen, O.M.; Thompson, M.L.; Janin, A.; McLeod, K.; McGowan, R.; McFarland, R.; Girisha, K.M.; Morris-Rosendahl, D.J.; Hurst, A.C.E.; Turner, C.L.S.; Hamilton, R.M.; Taylor, R.W.; Bajolle, F.; Gordon, C.T.; Amiel, J.; Mayr, J.A.; Doudney, K. PPA2-associated sudden cardiac death: extending the clinical and allelic spectrum in 20 new families. Genetics in medicine: official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics, 2021, 23, 2415–2425. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yan, R.; Roy, A.; Xu, D.; Poisson, J.; Zhang, Y. The I-TASSER Suite: Protein structure and function prediction. Nature Methods, 2015, 12, 7-8.

- The UniProt Consortium. UniProt: the Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D523–D531.

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng. E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612.

- Emsley, P.; Lohkamp, B.; Scott, W.G.; Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr., 2010, 66, 486–501.

- Li, H.; Robertson, A.D.; Jensen, J.H. Very Fast Empirical Prediction and Rationalization of Protein pKa Values. PROTEINS: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics, 2005, 61, 704-721.

- Gordon, J.C.; Myers, J.B.; Folta, T.; Shoja, V.; Heath, L.S.; Onufriev, A. H++: a server for estimating pKas and adding missing hydrogens to macromolecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33(Web Server issue), W368-71. [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual Molecular Dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 33–38. [CrossRef]

- Case, D.A.; Aktulga, H.M.; Belfon, K.; Cerutti, D.S.; Cisneros, G.A.; Cruzeiro, V.W.D.; Forouzesh, N.; Giese, T.J.; Götz, A.W.; Gohlke, H.; Izadi, S.; Kasavajhala, K.; Kaymak, M.C.; King, E.; Kurtzman, T.; Lee, T.-S.; Li, P.; Liu, J.; Luchko, T.; Luo, R.; Manathunga, M.; Machado, M.R.; Nguyen, H.M.; O’Hearn, K.A.; Onufriev, A.V.; Pan, F.; Pantano, S.; Qi, R.; Rahnamoun, A.; Risheh, A.; Schott-Verdugo, S.; Shajan, A.; Swails, J.; Wang, J.; Wei, H.; Wu, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, S.; Zhu, Q.; Cheatham III, T.E.; Roe, D.R.; Roitberg, A.; Simmerling, C.; York, D.M.; Nagan, M.C.; Merz Jr., K.M. AmberTools. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 6183-6191.

- Li, H.; Chang, Y.Y.; Lee, J.Y,; Bahar, I.; Yang, L.W. DynOmics: dynamics of structural proteome and beyond. Nucleic Acids Res., 2017, 45, W374-W380.

- Eyal, E.; Lum, G.; Bahar, I. The anisotropic network model web server at 2015 (ANM 2.0). Bioinformatics, 2015, 31, 1487–1489. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.W.; Rader, A.J.; Liu, X.; Jursa, C.J.; Chen, S.C.; Karimi, H.A.; Bahar, I. o GNM: Online computation of structural dynamics using the Gaussian Network Model. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, W24–W31. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).