Submitted:

23 December 2024

Posted:

24 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

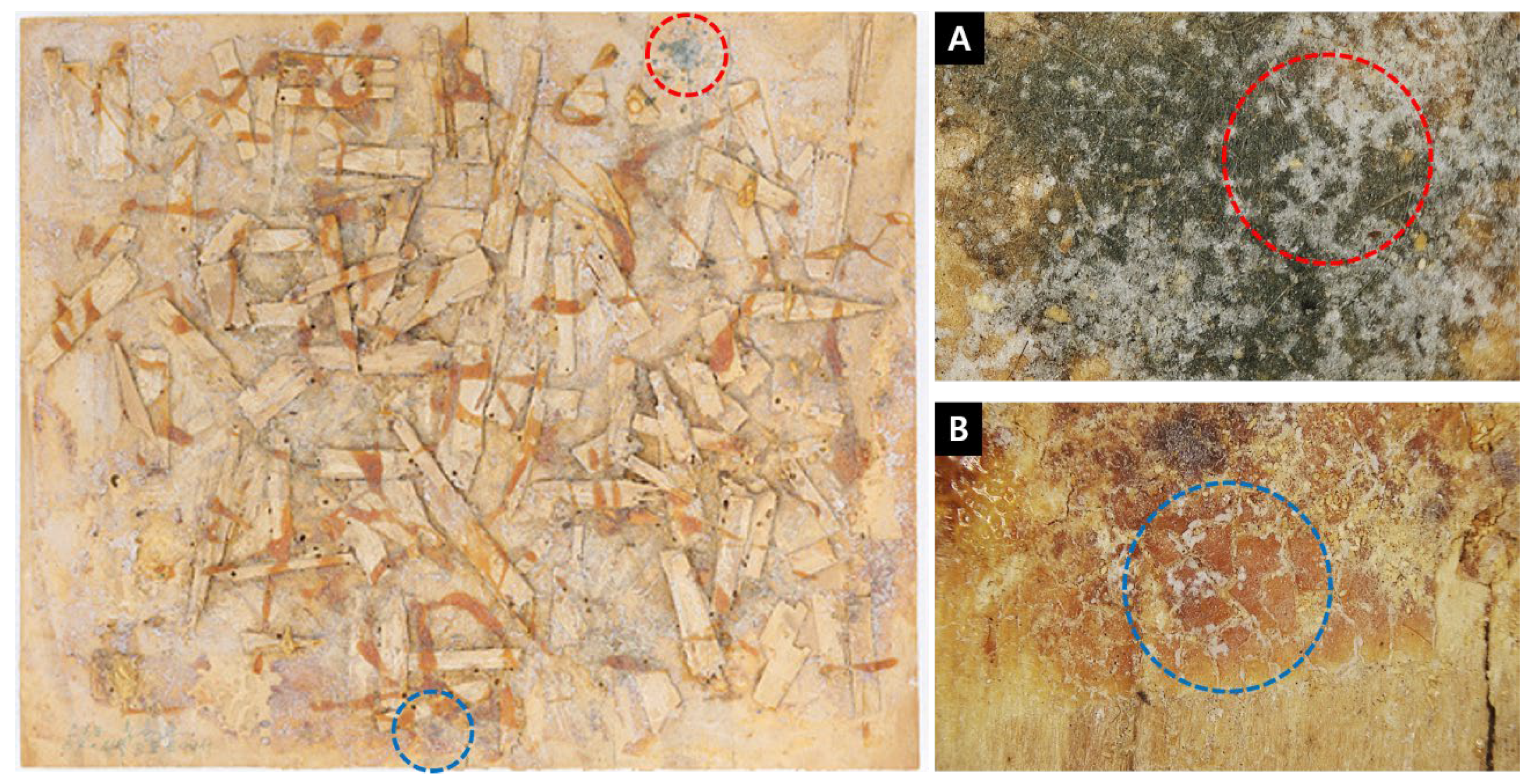

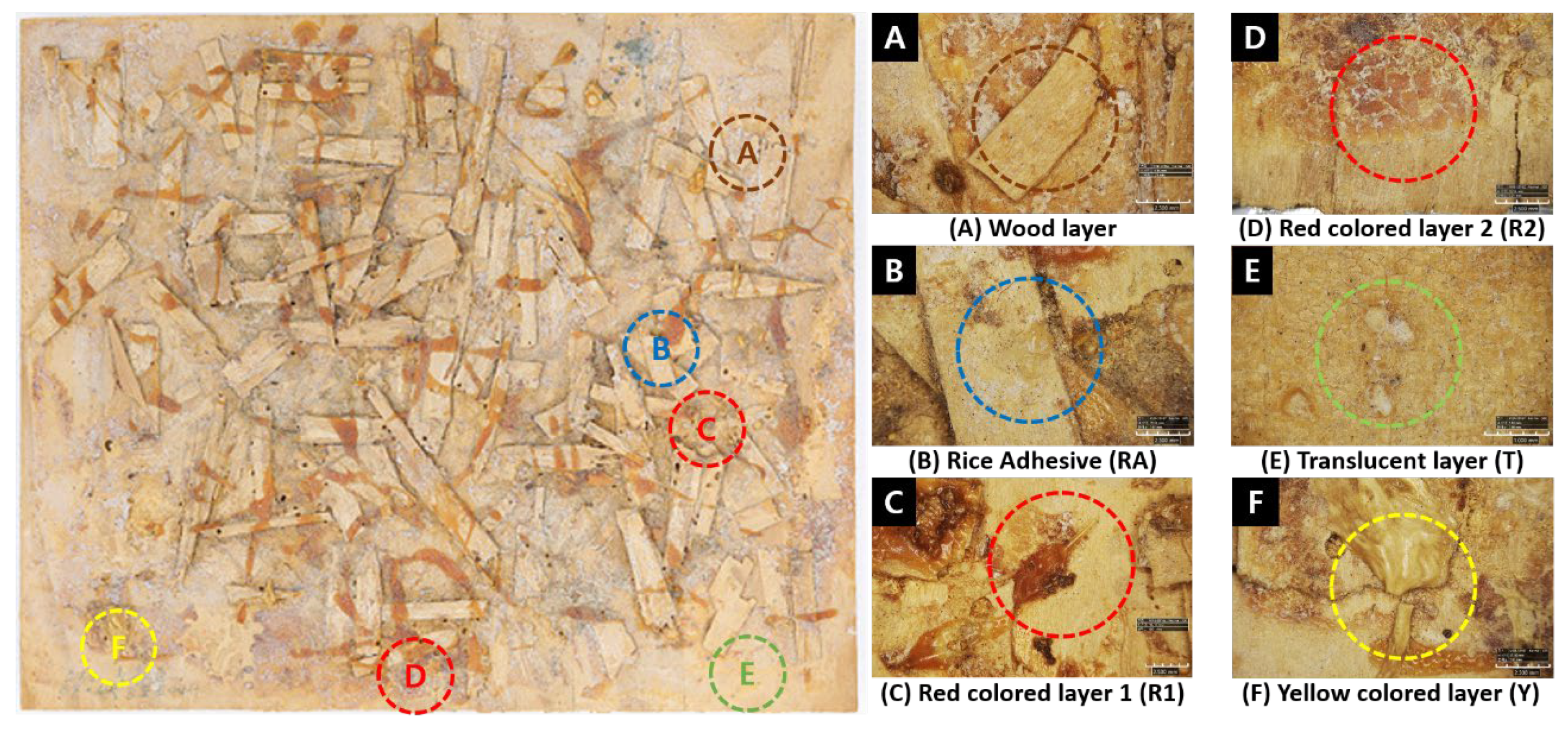

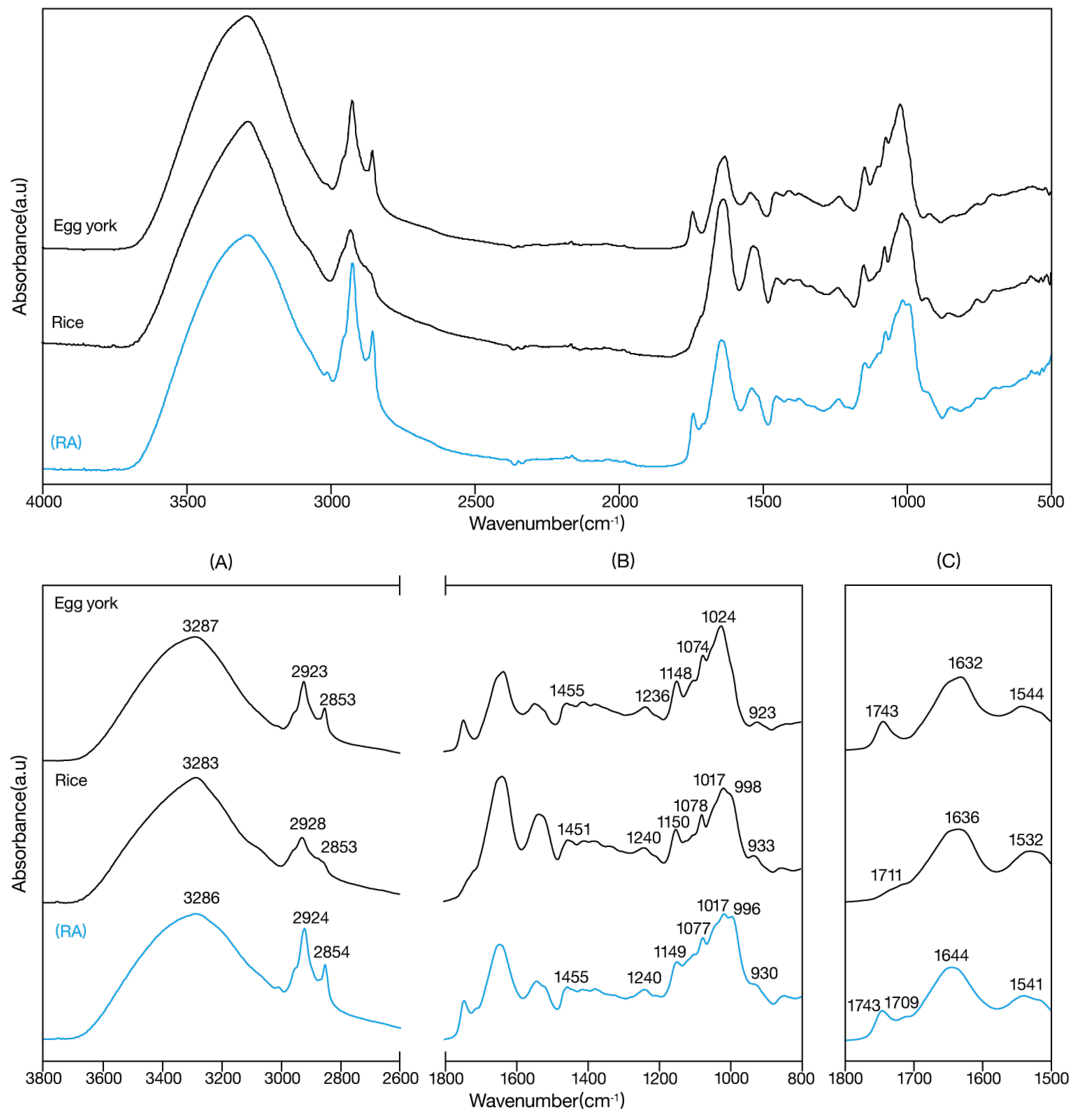

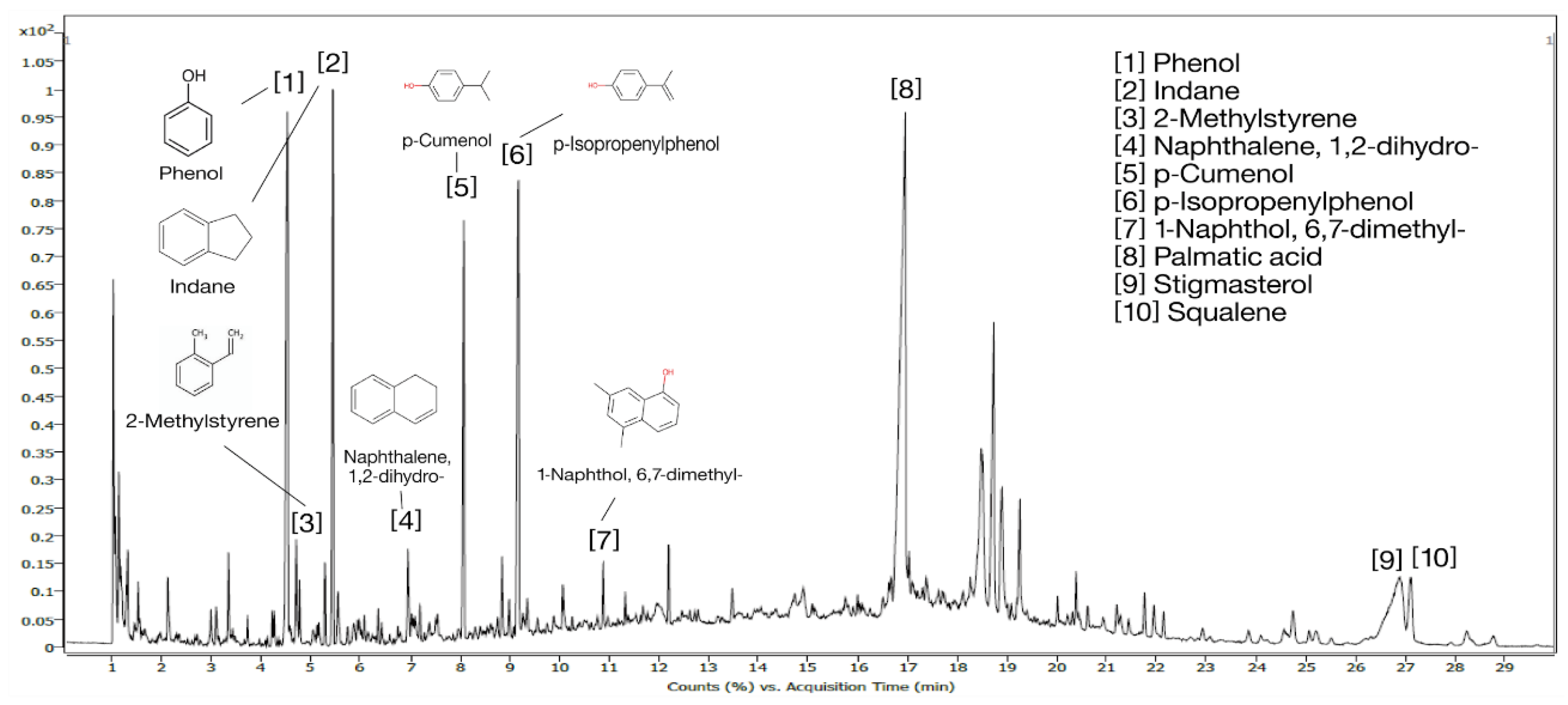

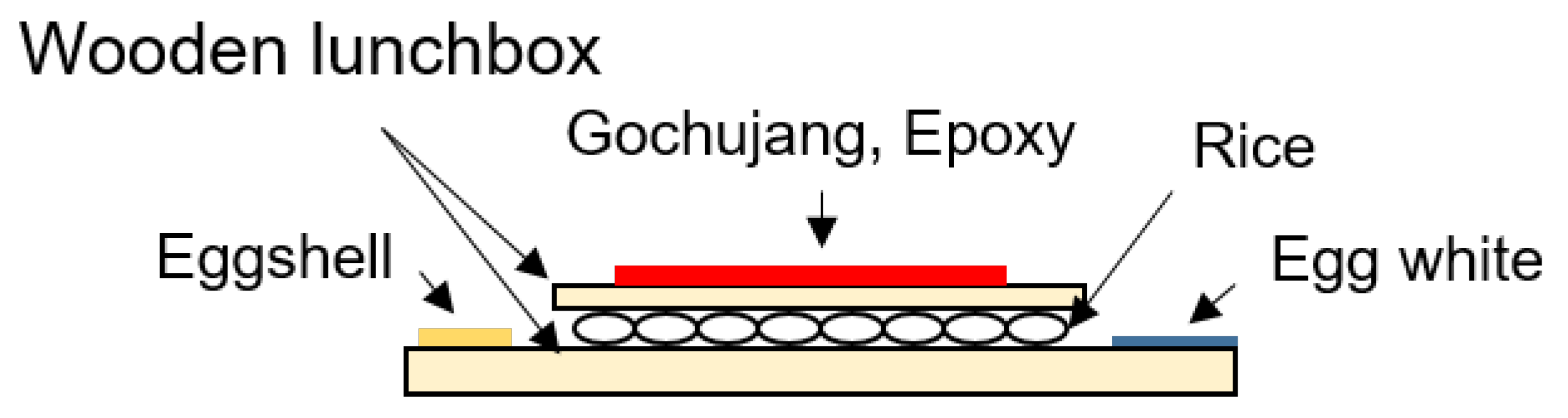

In this study, we used scientific analysis to estimate the materials used in Lee Ungno’s “Composition (1967)”, which is composed of ingredients such as gochujang and rice grains available in the prison, with the aim of establishing durable conservation materials for the artwork. The support material of the artwork was identified as hard pine, and the red-colored layers were identified as epoxy resin and gochujang. The adhesive applied to affix the wooden pieces to the support was determined to consist of rice grains, the translucent layer at the bottom of the artwork consisted of egg whites, and the yellow-colored layer contained eggshells. During the scientific analysis of the artwork, a combination of various other ingredients was identified as a result of the decomposition of ingredients, damage by microorganisms, and contamination. By utilizing control materials for comparison based on interviews and records of the artist, it was possible to estimate the specific type of food ingredients used. This approach provides fundamental information for the conservation of contemporary food-based artworks, and we anticipate that our findings will contribute to future conservation strategies for similar artworks.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Analytical Methods

2.1. Support Analysis

2.2. Screen Material Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Species Identification in the Support

3.2. Analysis of Media Materials

3.2.1. Rice Grain Adhesive (RA)

3.2.2. Red Colored Layer 1 (R1)

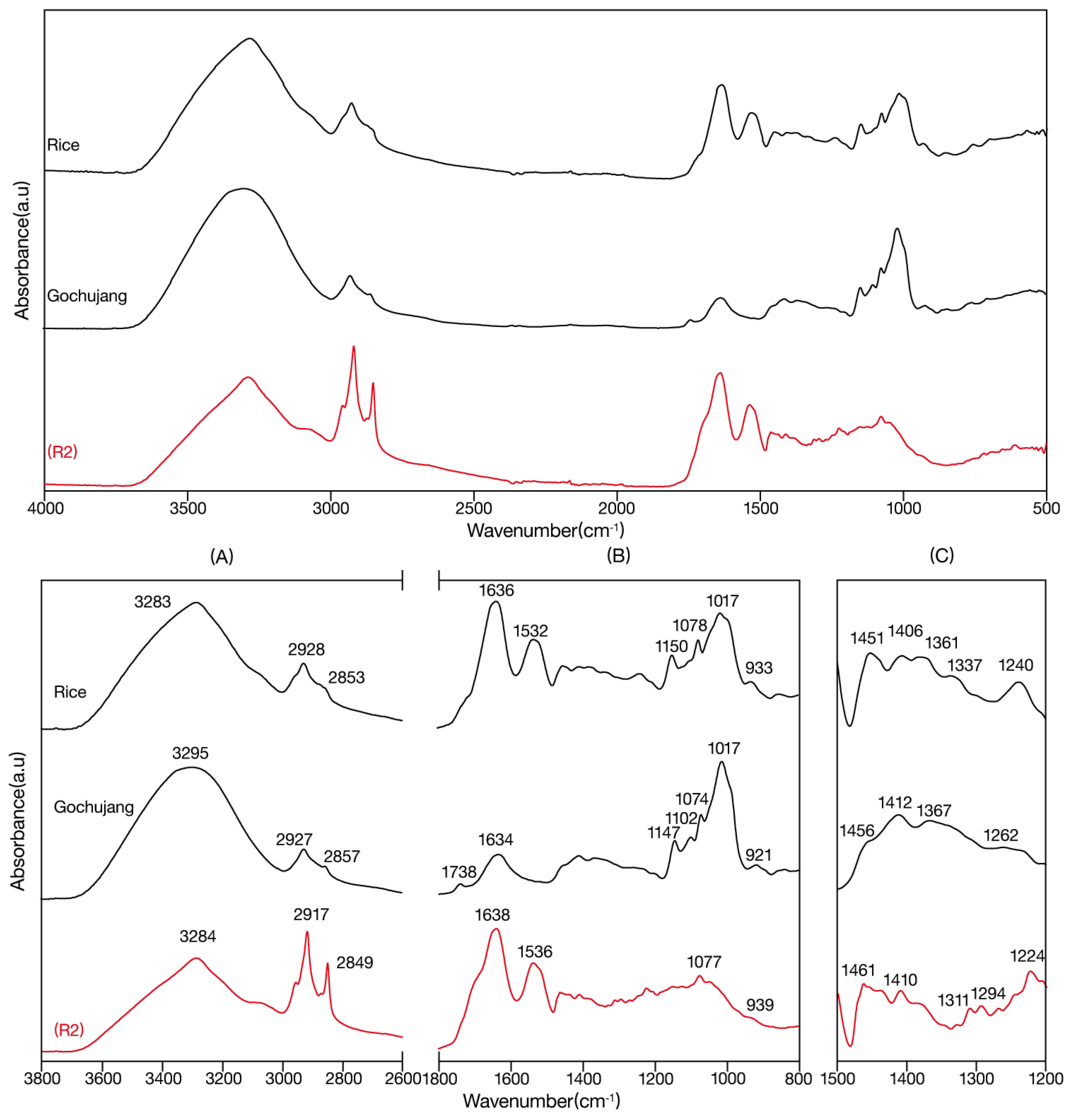

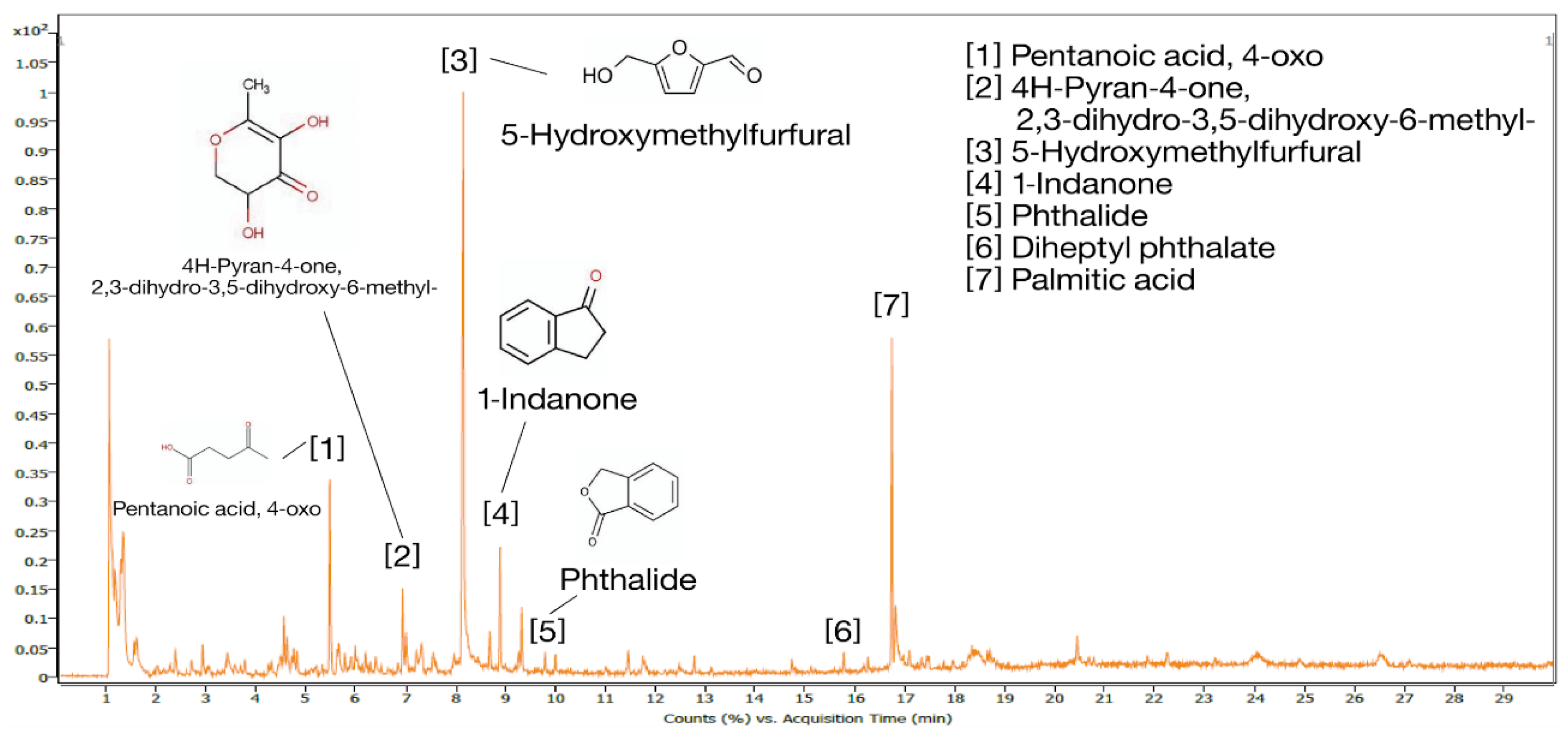

3.2.3. Red Colored Layer 2(R2)

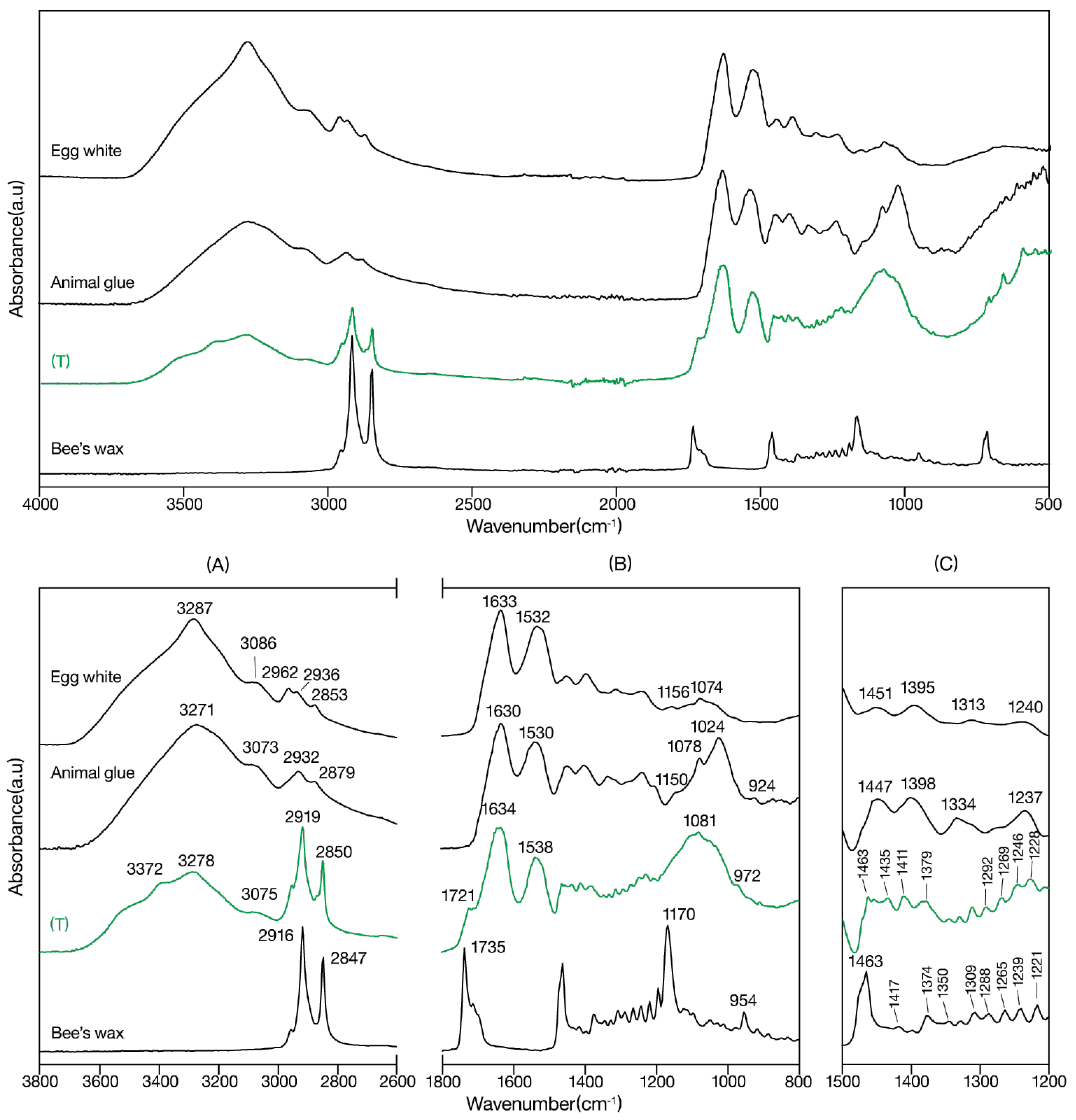

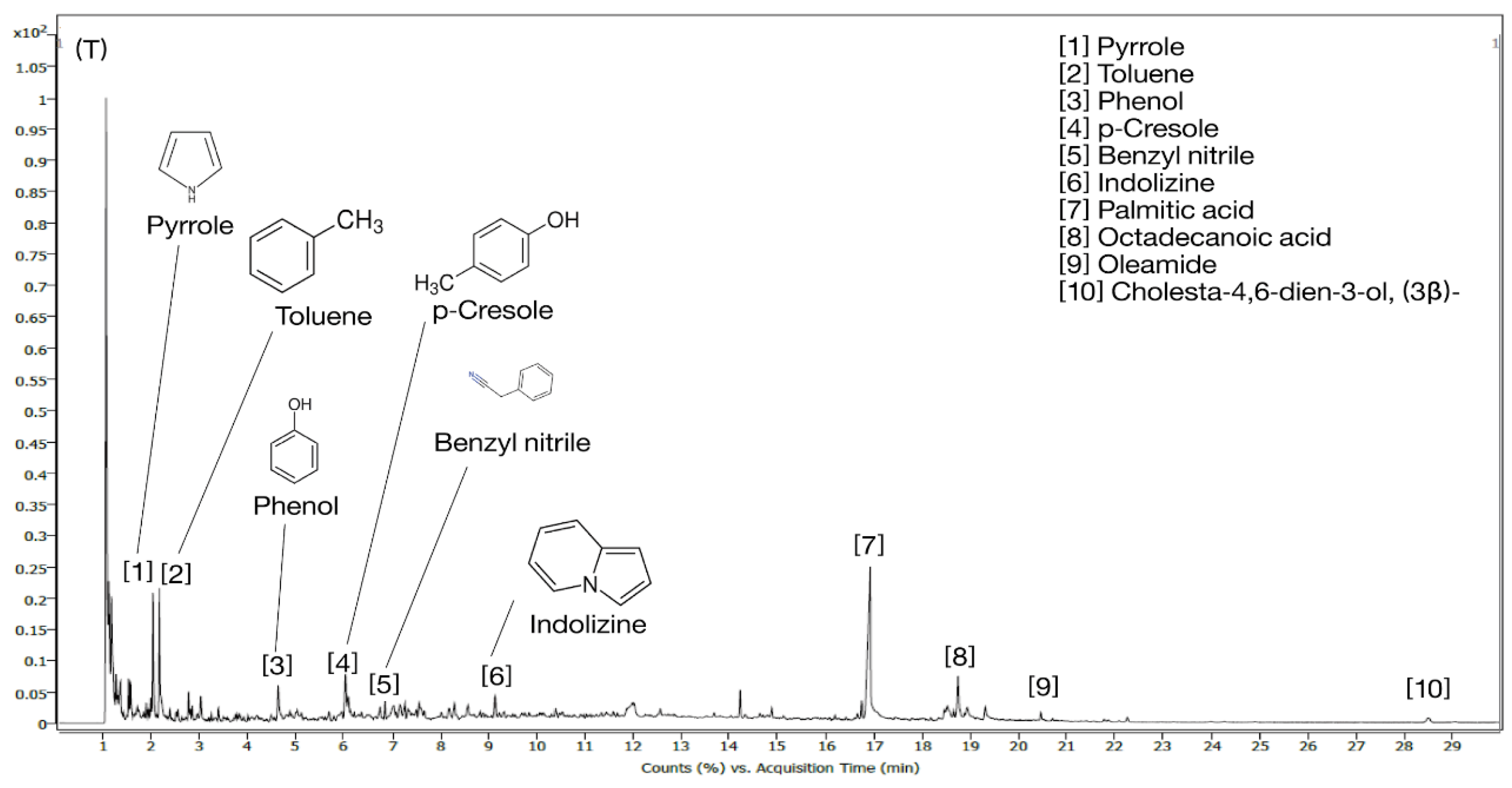

3.2.4. Translucent Layer (T)

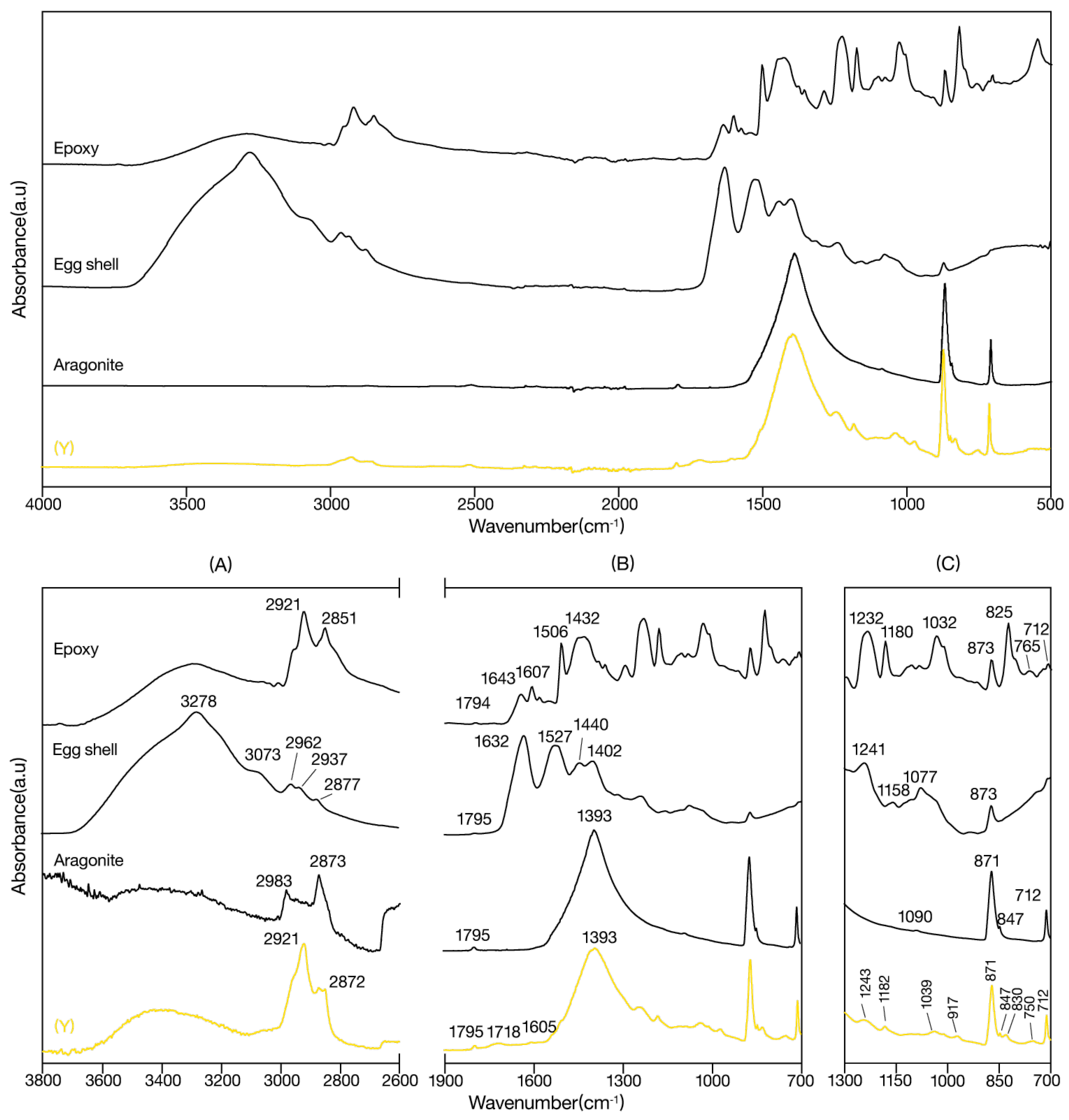

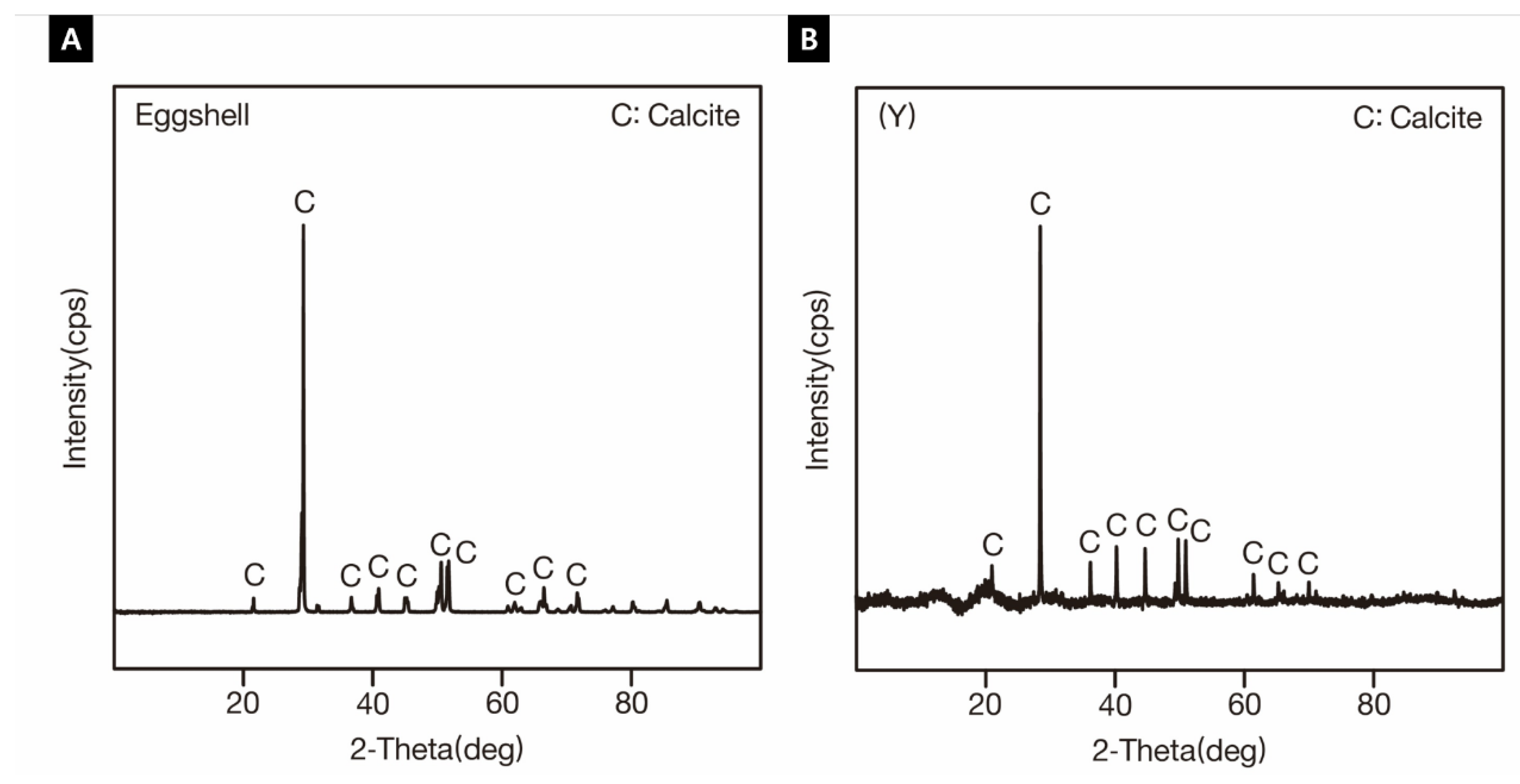

3.2.5. Yellow Colored Layer (Y)

4. Discussion

4.1. Materials in Lee Ungno’s “Composition”

4.2. Conservation Strategies for Contemporary Artworks: A Complementary Approach Combining Scientific Analysis with Non-Material Data

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shin, J.A.; Han, Y.B.; Cha, S.M.; Kim, Y.M.; Kwon, H.H. Conservation of contemporary artworks made with soap and research on the approprlate hygrothermal environment. J. Conserv. Sci. 2021, 37, 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koczanowicz, D. Beyond Taste: Daniel Spoerri’s art of feasting. Perform. Res. 2017, 22, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronado Garcia, C.M. Can We Use the Concept of Programmed Obsolescence to Identify and Resolve Conservation Issues on Eat Art Installations?, Living Matter: The Preservation of Biological Materials in Contemporary Art, An International Conference Held in Mexico City, June 3–5. Getty Conservation Institution, 2019.

- MALBA, Víctor Grippo: Homenaje, 2012. Available online: https://malba.org.ar/evento/victor-grippo-homenaje/ (accessed on 27 December 2012).

- Tadawa, T. Oppression to maintain power security, this is a national shame. National Times (accessd on 1 November 1985).

- Goam art institute. Goam Lee Ungno, Life and Art, Sprit and Knowledge; Eul gwa Al Co.,Ltd: Seoul, Korea, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Daejeon Goam Art and Culture Foundation LeeUngno Museum. Collection of Lee Ung No-Sculpture; International Print, Daejeon, Korea, 2021.

- Kim, J.G. The Loyalty and joy of life – Lee Eung-no's jade sculpture, fault in korean modern and contemporary art, In Life and Dream, The 33-Year History of Lee Eung-no's Study(1989~2021); Leeungno museum, Daejeon, Korea, 2021, 9–322.

- Park, S.J.; Lee, W.Y.; Lee, W.H. Timber organization and identification; Hangmunsa: Seoul, Korea, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, P.W. Wood properties and uses of the tree species grown in KoreaⅠ; Seoul National University Press: Seoul, Korea, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda, K.; Suzuki, A.; Kato, M.; Imai, K. Analysis of rice (Oryza sativa L.) lignin by pyrolysis-gas chromatography. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 1995, 34, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Yu, J.A.; Chung, Y.J. Study on qualitative analysis for lacquer mixed with some additives by pyrolysis-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. J. Conserv. Sci. 2017, 33, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsini, S.; Parlanti, F.; Bonaduce, I. Analytical pyrolysis of proteins in samples from artistic and archaeological objects. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2017, 124, 643–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.A. Analysis of binder in korean traditional Dancheong. Ph.D. Thesis, Korea National University of Cultural Heritage, Buyeo, Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, U.C.; Park, J.H.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, S.C. Study on scientific analysis about red pigment and binder -the korean ancient red pottery-, Conserv. Sci. 2021, 37(5), 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén, M.D.; Cabo, N. Infrared spectroscopy in the study of edible oils and fats. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1997, 75, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subirade, M.; Kelly, I.; Guéguen, J.; Pézolet, M. Molecular basis of film formation from a soybean protein: Comparison between the conformation of glycinin in aqueous solution and in films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 1998, 23, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, P.L.; Cheong, K.Y.; Lee, H.L.; Zhao, F. Effects of drying temperature on preparation of pectin polysaccharide thin film for resistive switching memory. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2022, 33, 19805–19826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.W. Infrared Spectroscopy for Food Quality Analysis and Control, 1st ed.; Elsevier Inc., London, United Kingdom, 2009.

- Kim, P.Z.; Hong, S.M.; Kim, C.H. Studies on therma degradation and analysis of starches by pyrolysisgas chromatography/mass spectrometry. J. Korean Soc. Anal. Sci. 1989, 2, 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Vane, C.H.; Abbott, G.D. Proxies for land plant biomass: Closedsystem pyrolysis of some methoxyphenols. Org. Geochem. 1999, 30, 1535–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.C. Pyrolysis Behaviors of Carbohydrate Using Pyrolysis-GC and Pyrolysis-GC/MS. Master’s Thesis, Sejong University, Seoul, Korea, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Neal, S.G.; Qin, L.; Hong, Y.; George, D.C.; Marilyn, L.F.; Weiguo, L.; Guoping, S. Org. Geochem. Molecular preservation and bulk isotopic signals of ancient rice from the Neolithic Tianluoshan site, lower Yangtze River valley, China. J. Org Geochem. 2013, 63, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Park, H.S.; Lim, S.J. Comparison study on the material characteristics of oil paint (Ⅰ). J. Conserv. Sci. 2017, 33, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombini, M.P.; Modugno, F.; Menicagli, E.; Fuoco, R.; Giacomelli, A. GC-MS characterization of proteinaceous and lipid binders in UV aged polychrome artifacts. Microchem. J. 2000, 67, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, B.; Rong, B. Analysis of polychromy binder on Qin Shihuang's Terracotta Warriors by immunofluorescence microscopy. J. Cult. Herit. 2015, 16, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Zhang, T.; Min, J.; Li, G.; Ding, Y.; Liu, J.; Gu, A.; Kang, B.; Li, Y.; Lei, Y. Analytical investigation into materials and technique: Carved lacquer decorated panel from Fuwangge in the Forbidden City of Qianlong Period, Qing Dynasty. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2018, 17, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahmetlioglu, E.; Yuruk, H.; Sürme, Y. Synthesis and characterization of oligosalicylaldehyde-based epoxy resins- Slovak Academy of Sciences. Chemical Papers. 2006, 60, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M.G.; Cabanelas, J.C.; Baselga, J. Applications of FTIR on Epoxy Resins – Identification, Monitoring the Curing Process, Phase Separation and Water Uptake. in Infrared Spectroscopy – Materials Science, Engineering and Technology, IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-953-51-0537-4.

- Kim, S.H.; Park, N.J.; Oh, M.S. Determination of epoxy resin type in EMC by pyrolysis-GC and GC/MS. Polym. (Korea) 1999, 23, 401–412. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Fina, A.; Ferraro, G.; Yang, R. FTIR and GCMS analysis of epoxy resin decomposition products feeding the flame during UL 94 standard flammability test. Application to the understanding of the blowing-out effect in epoxy/polyhedral silsesquioxane formulations. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2018, 135, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokkanta, P.; Sookwong, P.; Tanang, M.; Setchaiyan, S.; Boontakham, P.; Mahatheeranont, S. Simultaneous determination of tocols, γ-oryzanols, phytosterols, squalene, cholecalciferol and phylloquinone in rice bran and vegetable oil samples. Food Chem. 2019, 271, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, L.C.; Broco e Silva, R.G.; Scopel, E.; Hatami, T.; Rezende, C.A.; Martínez, J. Concentration of stigmasterol, β-sitosterol and squalene from passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims.) by-products by supercritical CO2 adsorption in zeolite 13-X. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2024, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anese, M.; Suman, M. Mitigation strategies of furan and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural in food. Food Res. Int. 2013, 51, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y.; Lee, T.S.; Park, S.O.; Noh, B.S. Changes of volatile flavor compounds in traditional Kochujang during fermentation. Korean J. Food Sci. Technol. 1997, 29, 745–751. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzeo, R.; Prati, S.; Quaranta, M.; Joseph, E.; Kendix, E.; Galeotti, M. Attenuated total reflection micro FTIR characterisation of pigment-binder interaction in reconstructed paint films. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2008, 392, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Blanco, J.; Shaw, S.; Benning, L. The kinetics and mechanisms of amorphous calcium carbonate (ACC) crystallization to calcite, via vaterite. Nanoscale 2010, 3, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widjonarko, D.M.; Jumina, J.; Kartini, I.; Nuryono, N. Phosphonate modified silica for adsorption of Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II), and Zn(II). Indones. J. Chem. 2014, 14, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, P.; Sharma, P.; Kumar, V. FTIR and GC-MS spectral datasets of wax from Pinus roxburghii Sarg. needles biomass. Data Brief 2017, 15, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brzeska, J.; Elert, A.M.; Morawska, M.; Sikorska, W.; Kowalczuk, M.; Rutkowska, M. Branched Polyurethanes Based on Synthetic Polyhydroxybutyrate with Tunable Structure and Properties. Polymers 2018, 10, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, D.; Maensiri, S.; Wongpratat, U.; Lee, S.W.; Nyachhyon, A.R. Shorea robusta derived activated carbon decorated with manganese dioxide hybrid composite for improved capacitive behaviors. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S. Analysis of animal glue by pyrolysis/GC/MS. Anal. Sci. Technol. 2015, 28, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelatin Manufacturers Association, Asia Pacific Press. 2015. Available online: http://www.gmap-gelatin.com/about_gelatin_AminoAcidComp.html (accessed on 3 Mar 2015).

- Jin-Li, Z.H.A.O.; Zong-Ren, Y.U.; Bo-Min, S.U. Analysis of egg whites from burial murals by pyrolysis-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Chin. J. Appl. Chem. 2023, 40, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, C.; Robertson, D.H. The analysis of proteins, peptides and amino acids by pyrolysis-gas chromatography and mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 1967, 5, 96–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuge, S.; Matsubara, H. High-resolution pyrolysis-gas chromatography of proteins and related materials. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 1985, 8, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldoveanu, S.C., Ed. In Analytical Pyrolysis of Natural Organic Polymers 1st edn. 20. Elsevier, 1998, 373–397.

- Drevin, I.; Johansson, B.L.; Larsson, E.L. Pyrolysis in biotechnology. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 2001, 18, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legan, L.; Retko, K.; Peeters, K.; Knez, F.; Ropret, P. Investigation of proteinaceous paint layers, composed of egg yolk and lead white, exposed to fire-related effects, Nature research. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asperger, A.; Engewald, W.; Fabian, G. Analytical characterization of natural waxes employing pyrolysis–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 1999, 50, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reig, F.B.; Adelantado, J.V.G.; Moya Moreno, M.C. FTIR quantitative analysis of calcium carbonate (calcite) and silica (quartz) mixtures using the constant ratio method. Application to geological samples. Talanta. 2002, 58, 811–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, H.P.; Cruz, A.J.; Candeias, A.; Mirão, J.; Cardoso, A.M.; Oliveira, M.J.; Valadas, S. Problems of Analysis by FTIR of Calcium Sulphate–Based Preparatory Layers: The Case of a Group of 16th-Century Portuguese Paintings. Archaeometry. 2014, 56, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrián, L.V.; Anastasia, E. Amine Responsive Poly(lactic acid) (PLA) and Succinic Anhydride (SAh) Graft-Polymer: Synthesis and Characterization. Polymers. 2019, 11, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W.K.; Lee, K.H. Changes in the species of woods used for Korean ancient and historic architectures. Archit. Hist. 2007, 50, 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, H.C.; Lee, W.H. Characteristics and Species of wooden chopsticks. J. Korea Furniture Soc. 2022, 33, 129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, H.H.; Lee, G.S. Collaboration with stakeholders for conservation of contemporary art. J. Conserv. Sci. 2020, 36, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.M.; Han, Y.B.; Shin, J.A.; Cha, S.M.; Kwon, H.H. The conservation treatment of the bark of wooden sculpture. J. Conserv. Sci. 2021, 37, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).