1. Introduction

It is estimated that more than 200 million people around the world are affected by anxiety disorder [

1]. In addition, up to one-third of the population are affected by anxiety disorder during their lifetime [

2]. Over the COVID-19 pandemic, there had been an alarming increase of anxiety and depression across the world [

3,

4]. However, despite the growing demand of mental health care, the accessibility and acceptability of treatment options has been limited hampering the effective provision, only a small number of people receive adequate and effective intervention [

5]. Problems can be found in two current major emotional interventions - medication is likely to cause side-effects; cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is relatively costly and time-consuming [

6,

7].

To address such limitations, online and mobile-based interventions in mental health have been actively investigated as possible alternatives given its good accessibility and portability [

8,

9]. Among promising methods is Attention Bias Modification (ABM), an emerging low-cost, computer-based attention retraining protocol. ABM training engages a modified visual probe task with the goal of affecting emotions and reducing anxiety [

10]. It is found effective in reducing anxiety levels by targeting attentional threat bias (a key cognitive mechanism in anxiety) through repeatedly attending to specific target positive stimuli and ignoring others [

7,

11] and may have the potential to be used in daily settings beyond the clinical environment.

ABM training is considered repetitive and not engaging, which may reduce treatment compliance [

12]. Combining the gamification techniques for addressing the core issues of diminishing motivation to ABM treatments [

13], researchers have recently reported that gamified interventions can improve the performance of the attention bias modification task [

14,

15,

16]. This has a greater potential for promoting engagement in ABM treatment for managing stress, anxiety and substance use, receiving considerable interest from the health research community [

17,

18]. Personal Zen is an exemplary application [

12,

15,

19], showing its positive effects on a reduction of threat bias, subjective anxiety, and stress reactivity with physiological evidence (cortisol level dropping compared with placebo training). It has also been shown that gamified ABM has wider mental health intervention benefits, such as reducing attention dwelling on threats [

20], intervening excessive alcohol consumption [

14] and enhancing optimism bias [

21]. However, the gamification approach only has not always been found effective, particularly some incongruent results and reported with limited motivation [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

On another note, augmented reality (AR) has been given growing attention in offering immersive experiences [

27,

28,

29]. AR enhances real-world interactions [

30,

31]. With its highly immersive nature, AR is not only a popular choice in gaming and educational contexts, but also has been found effective in the health care domain, for example surgical training [

32]. In clinical psychology, researchers have demonstrated that applying AR into cognitive therapy can successfully help reduce anxiety, avoidance behaviours and substance addiction [

33,

34,

35]. For example, Botella et al found that the AR treatments produced a decrease in patients’ fear and avoidance behaviours [

36,

37]. Furthermore, applying AR to mobile applications has been found cost-effective, portable, and with higher accessibility features in comparison with headsets-based AR [

31]. Its wider benefits of mobile AR intervention were highlighted in treating anxiety disorders [

28] and supporting people with ASD (Autistic Spectrum Disorders) [

31] and children with ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) [

38]. However, the compelling interactive feature has not been explored and considered in ABM intervention, which can possibly be applied to a wide range of real-life situations.

Thus, in this paper we aim to investigate mobile AR integrated into a gamified ABM and its effects in uplifting a user’s mood states. We develop Uplifting Moods, a mobile AR ABM gamified mood intervention app and evaluate this in a mixed study with 24 participants, which is guided by our two research questions: To what extent is this new approach effective in improving people’s moods across two major affective dimensions: arousal and valence? And what features are important for designing an engaging and effective ABM game that keeps motivating users? Our findings inform design implications for researchers, software developers and designers to build joyous ABM games as a motivative emotional intervention to help enhance people’s mental health in real-life situational contexts.

Contributions - this paper makes three contributions: (i) Uplifting Moods: Design and implementation of a novel mobile intervention app combining AR and ABM gamification for improving daily mental wellbeing; (ii) Report on studies that demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposed AR-enabled ABM through a series of quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis; and (iii) Implications for software developers, designers and practitioners in developing mental health intervention software with the AR-enabled ABM gamification that can be more engaging and effective.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Gamified Intervention with AR and ABM: UPLIFTING MOODS

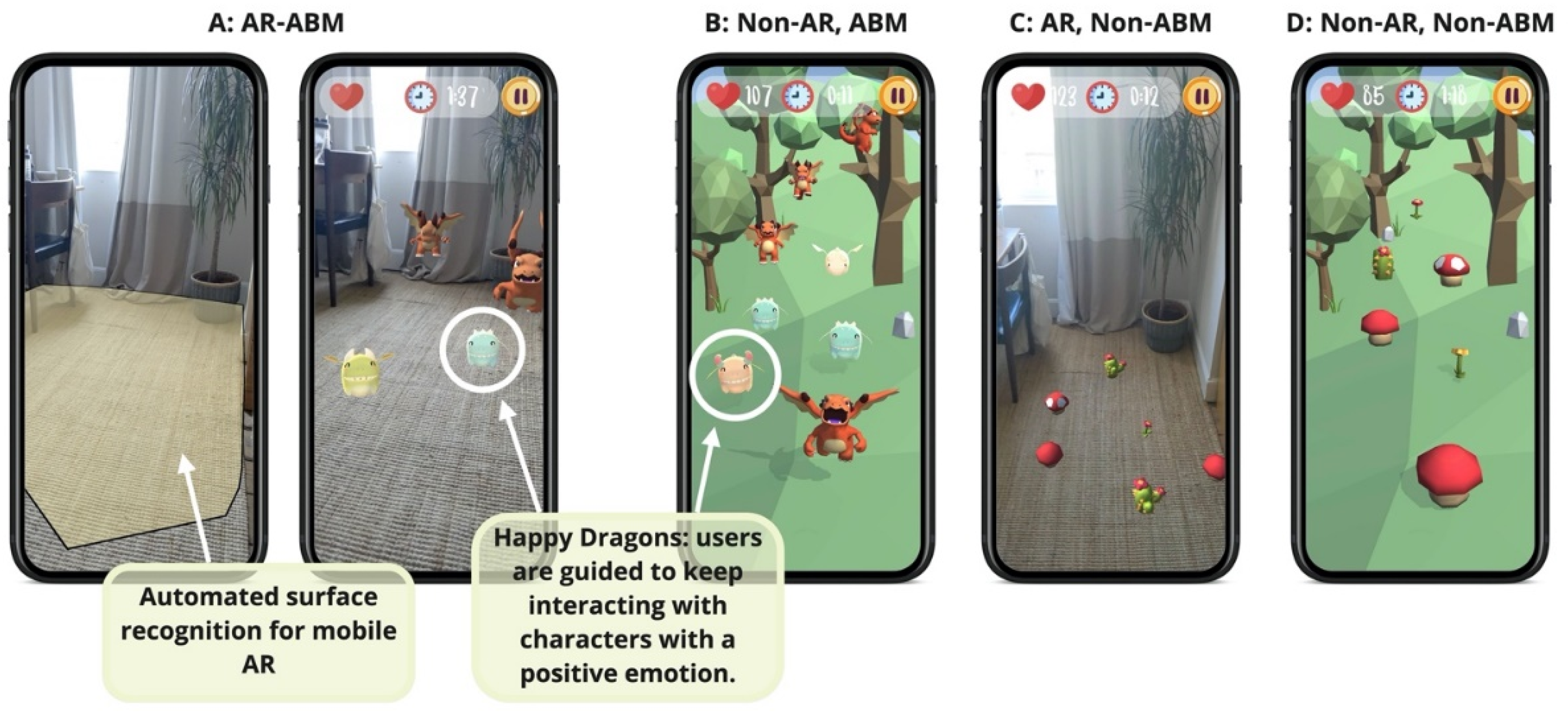

As shown in

Figure 1, we have developed a mobile application

Uplifting Moods and investigate the effectiveness of combining AR and ABM treatment in eliciting beneficial emotional outcomes. Two independent variables (IV) - presence of ABM and presence of AR (with each having two conditions) - are set out for this experiment as summarised in

Table 1. The first IV is ABM with two conditions: ABM and non-ABM. The first condition focuses on positive and negative stimuli referred to happy and angry imaginary animal characters (lively dragons), where participants are asked to search for the characters with positive emotions. In a gamification context, the search task is referred to as “petting happy dragons (characters with positive emotion)”. By contrast, the second condition asks participants to follow neutral objects without emotional expressions (“collecting food” in gamification). The second IV conditions are AR and non-AR, which decides whether to present both ABM and non-ABM tasks in an augmented reality environment. The games are progressed through rounds, during which users can interact with objects and earn score points.

We implemented

Uplifting Moods with the concept of a low-polygon, cartoon-style casual game and followed consistency in user interface design (see

Figure 1) [

39]. Combining visually appealing and consistent game art, happy and uplifting background music and proper sound effects, the final outcome of the design achieved an aesthetic game as a whole. Every condition and corresponding application are implemented using the Unity3D game engine (v. 2020.3.5f1).

2.2. Experimental Design

2.2.1. Participants

Twenty-five adult participants were recruited and asked to fill in questionnaires and participate in experimental sessions and follow-up interviews. One participant was excluded due to the battery issue of the participant’s mobile phone. The final sample consisted of data from 24 adults (13 females, 11 males) aged 24 to 59 (M=31.375, SD=8.7268). For recruiting participants who may have state anxiety, a simplified version of Highly Sensitive Person Scale (HSPS) [

40] was used as a screening tool to recruit participants who scored above 65 (people who scored above 70 are considered having sensory processing sensitivity) as it has been proven that highly sensitive people may also experience higher levels of anxiety [

41,

42]. The scores of HSPS were used for screening purposes only.

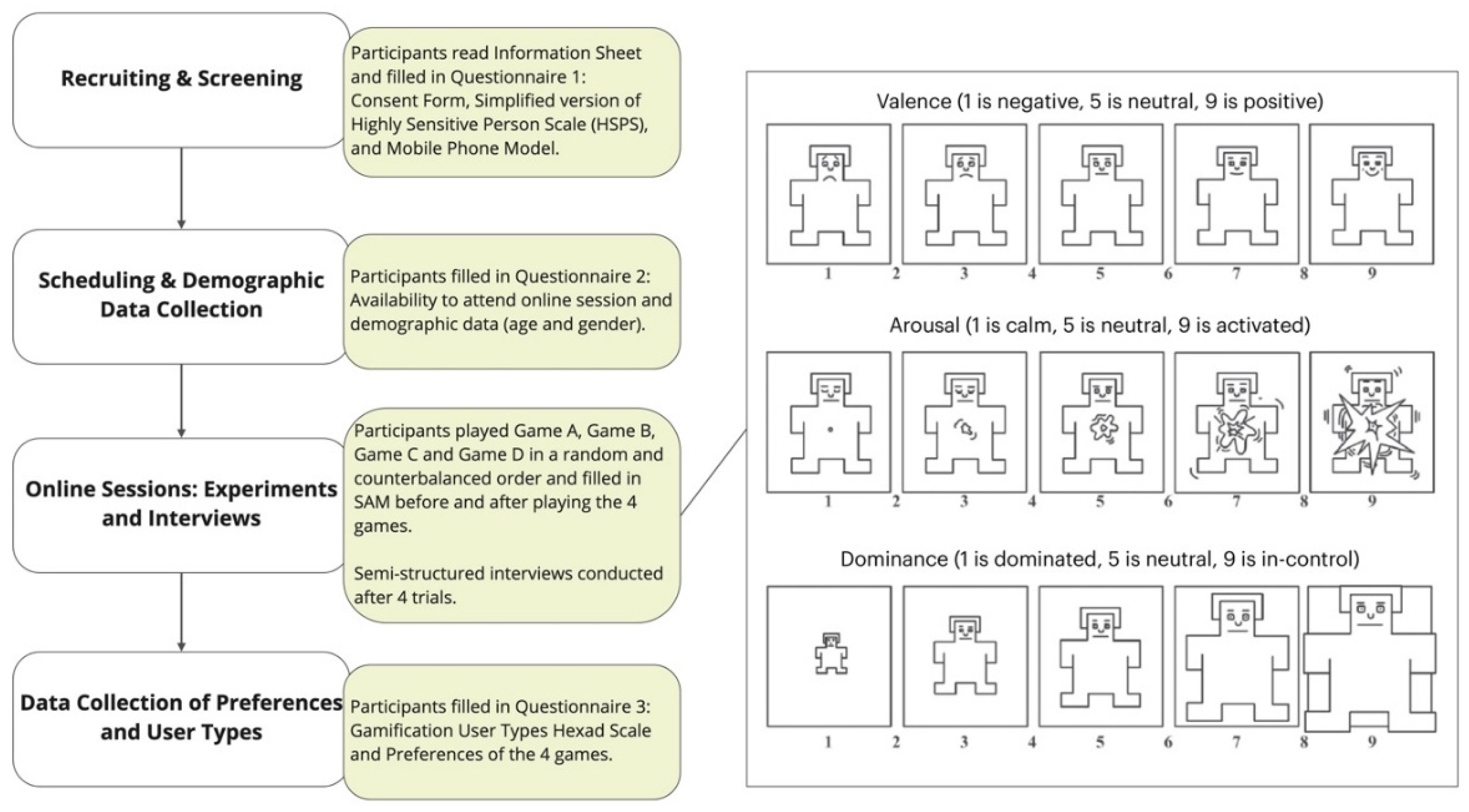

2.2.2. Tasks and Experiment Protocol

Figure 2 shows our experiment protocol for this study. Prior to experimental sessions, participants received the information sheet, consent form, and simplified HSPS, questionnaires on baseline demographic data. At the beginning of the experiment, introductions of the study procedure and instructions for using

Uplifting Moods were given to the participants. The goal of all game types is to touch targeted objects and avoid non-targeted ones to get the highest score. Participants were informed that clicking quicker would get higher points. Game stories of the game types (conditions for IVs) are summarized below:

Game Type A & B (Petting Lively Characters with Positive Emotion; AR interactive mode and regular mode): Players should interact with happy dragons and avoid angry dragons. By touching the happy dragons players receive rewarding points (faster interaction boosts the points; i.e., higher points). By contrast, touching angry dragons will lose points.

Game Type C & D (Collecting Objects without Emotion; AR interactive mode and regular mode): Players should only collect mushrooms among all the plants (which are the food for dragons). Collecting the right food will get points (faster interaction boosts the points; i.e., higher points). Collecting wrong foods will lose points.

With 2x2 conditions (IVs: AR and ABM), the present study uses a within-group design, in which all the participants were required to attend four trials including Game A: Petting Dragons in AR mode (ABM, AR), Game B: Petting Dragons in regular mode (ABM, non-AR), Game C: Collecting Food in AR mode (non-ABM, AR), and Game D: Collecting Food in regular mode (non-ABM, non-AR) in a random and counterbalanced order. When playing the games, the participants get visual feedback from their actions based on animations of objects and changes in UI (update of score and timer text). During the 3-min playing time in each of the games, positive (targeted) and negative (non-targeted) objects appeared 50% and 50% at random locations. The number of objects gradually increased from minimal 2 to maximal 8 in 47 rounds. The time for each round gets faster from 6 seconds to 4 seconds. Background music and sound effects were also exploited in the game. When users touch the targeted positive object, positive sound plays. When they touch the non-targeted objects, negative and buzzer sound plays.

Before and after playing each of the games, the participants were asked to fill in levels of arousal, valence, and dominance in a visualised 9-point scale Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM) [

43] (See

Figure 2). The participants had more than 3-min breaks between each of the 4 sessions until they feel relaxed. After the 4 experimental sessions, semi-structured user interviews were conducted to dive into participants' feelings about each of the games, preferable and unlikable features and their experiences regarding playing games generally and mental wellness. For analysing the results thoroughly by understanding each participant further, a questionnaire with the Gamification User Types Hexad Scale [

44] and a question about their preference of 4 games was additionally sent to the participants after the study sessions 1-2 weeks.

3. Results

We analysed the collected data from the questionnaires, SAM, and the interviews to examine the efficacy of AR in mood changing in the 4 game types (along with IV conditions), relations between AR and ABM, the usability of

Uplifting Moods, and the insights for designing an AR ABM game.

Table 2 shows participant demographics, HSPS results, ranking of 4 games, frequency of playing games, and User Types based on Marczewski's Player and User Types Hexad [

45]. The statistical analysis was conducted with IBM SPSS.

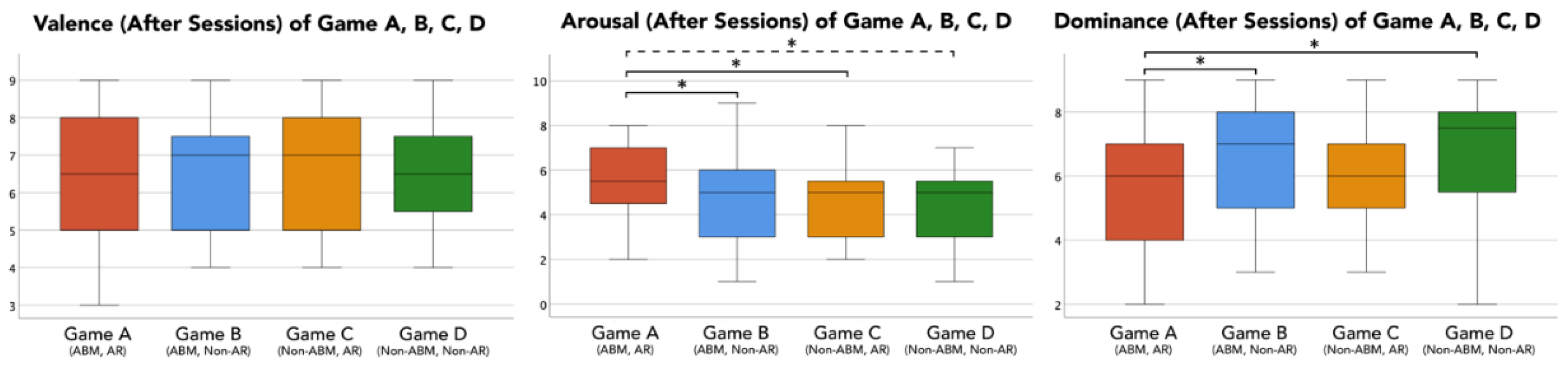

3.1. Self-Assessment Manikin

Descriptive statistical analyses on SAM results of baseline (data before the first trial) and after 4 experimental sessions were conducted (Valence from Baseline: mean 5.87, SD 1.51; Valence from Game Type A: mean 6.5, SD 1.86; Valence from Game Type B: mean 6.41, SD 1.47; Valence from Game Type C: mean 6.5, SD 1.58; Valence from Game Type D: mean 6.54, SD 1.35; Arousal from Baseline: mean 3.95, SD 1.70; Arousal from Game A: mean 5.45, SD 1.69; Arousal from Game B: mean 4.75, SD 1.79; Arousal from Game C: mean 4.5, SD 1.71; Arousal from Game D: mean 4.54, SD 1.64; Dominance from Baseline: mean 5.54, SD 1.66; Dominance from Game A: mean 5.70, SD 2.05; Dominance from Game B: mean 6.58, SD 1.90; Dominance from Game C: mean 6.29, SD 1.80; Dominance from Game D: mean 6.87, SD 1.98). Boxplots for valence, arousal and dominance rating distributions from after sessions across 24 participants for 4 games are shown in

Figure 3.

A Shapiro-Wilk test showed that valence, arousal and dominance ratings from all 4 games of Uplifting Moods are not normally distributed (p < 0.05). We therefore performed a non-parametric Friedman test on the values of valence (F Value = 0.425, p > 0.05), arousal (F Value = 8.213, p < 0.05) and dominance (F Value = 12.15, p < 0.05) to analyse the differences of participants’ perception in the 4 different games. Significant effects were found on changes of arousal and dominance among the 4 games, whereas there was no significant difference in valence values.

Post-hoc pairwise comparisons using Wilcoxon signed ranks tests were performed to compare the 2 repeated measurements AR and ABM in the 4 games (See

Table 3). The results showed the AR ABM (Game A) made users feel activated (higher arousal rate) and less dominated. There were significant differences on arousal levels between the pairs: A-B, A-C (p<0.05) with an approaching significance in the pair A-D, confirming the AR feature leading to more aroused states. Additionally, we performed pairwise comparisons on the dominance. There were significant differences between the pairs: A-B and A-D (p<0.05). Interestingly, without having AR feature, the participants felt more in control – this result also reflects on the qualitative study in the following section that the higher degree of difficulty of Game Type A made some of the participants feel less in control. Possible reasons for this trend are discussed in the corresponding section.

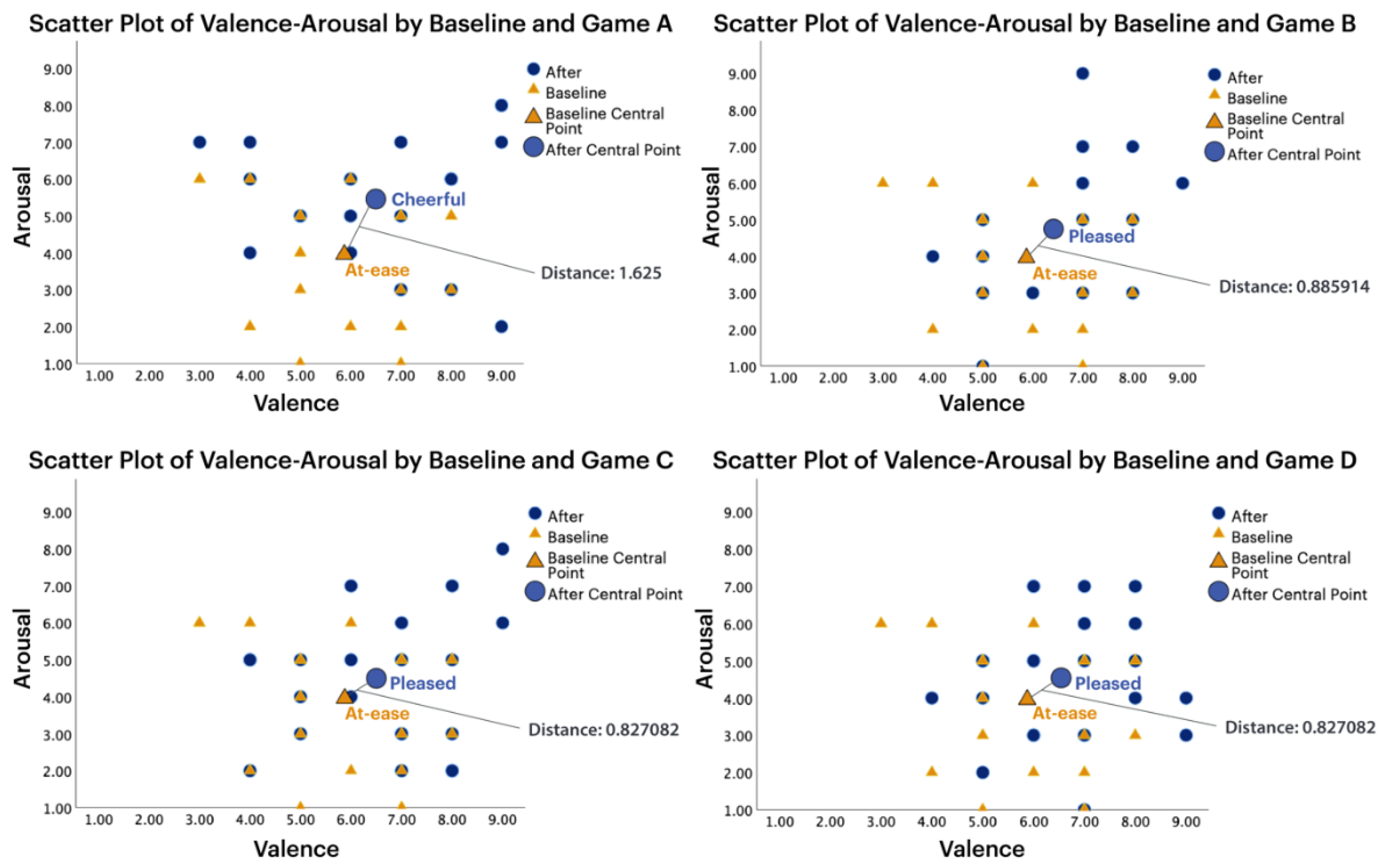

Further, we conducted valence-arousal dimensional analysis. With Russell’s Circumplex model of affect [

46] that shows two dimensions of emotions (with the valence dimension in the horizontal axis and the arousal dimension vertical axis), we dived into the changes in ratings from baseline and after sessions.

Figure 4 shows scatter plots of ratings in the valence-arousal dimension. Central points of baseline and after session data were created with the means of the corresponding ratings. From the Euclidian distances calculated from the central points, we confirm that moods from the AR ABM intervention (Game Type A) particularly improved with the longest distance 1.625 to the point of “

cheerful” state on average while the distances (mood changes) from other three interventions were 0.886, 0.827 and 0.827 respectively (all “

pleased” state on average). Compared with the other interventions, the proposed AR ABM intervention lifted the users’ mood more by increasing their arousal moderately to the optimal arousal level. Note that when people are in the optimal arousal state, they not only feel more energised but also more focused on their task performance [

47].

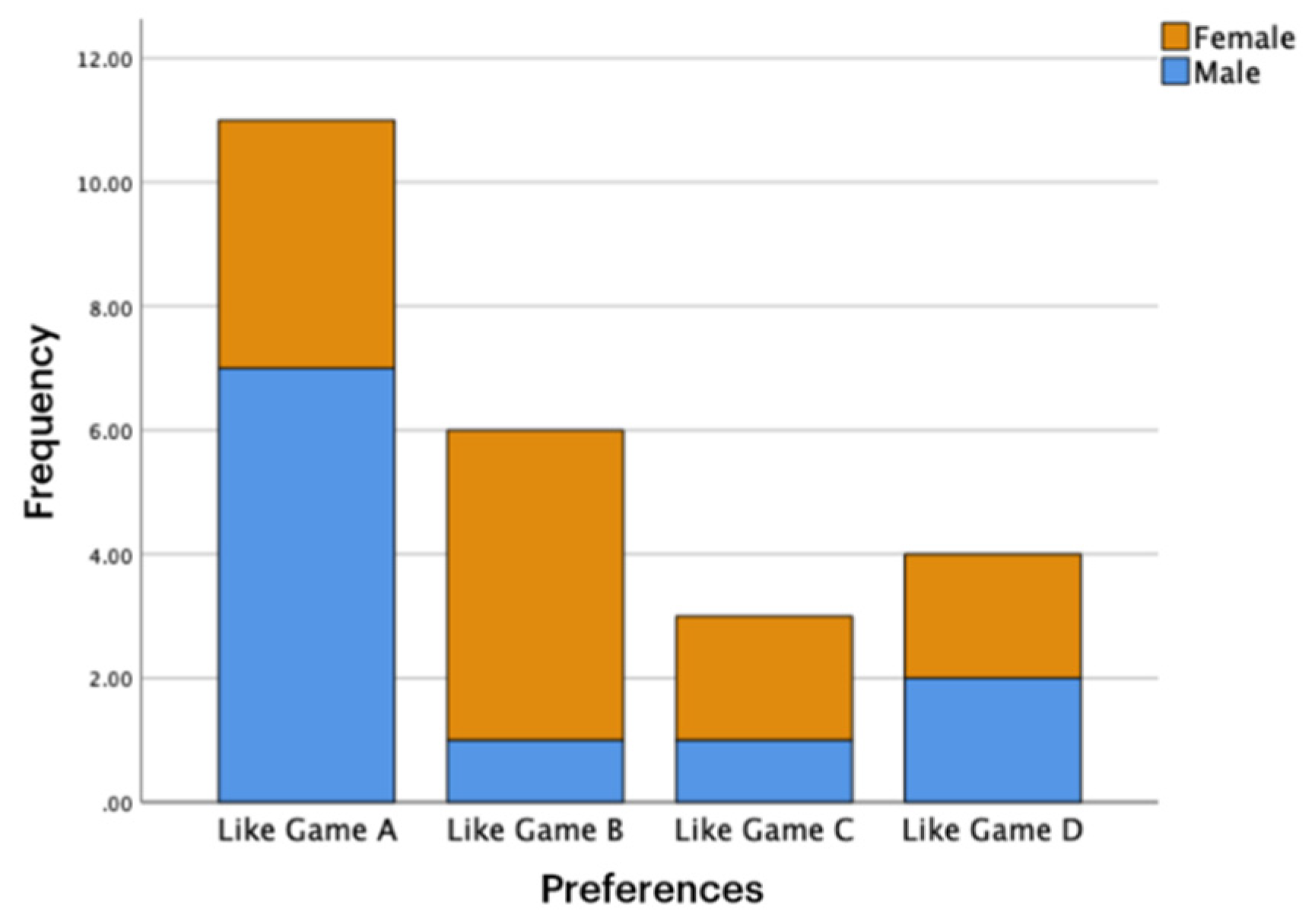

3.2. Game Preference

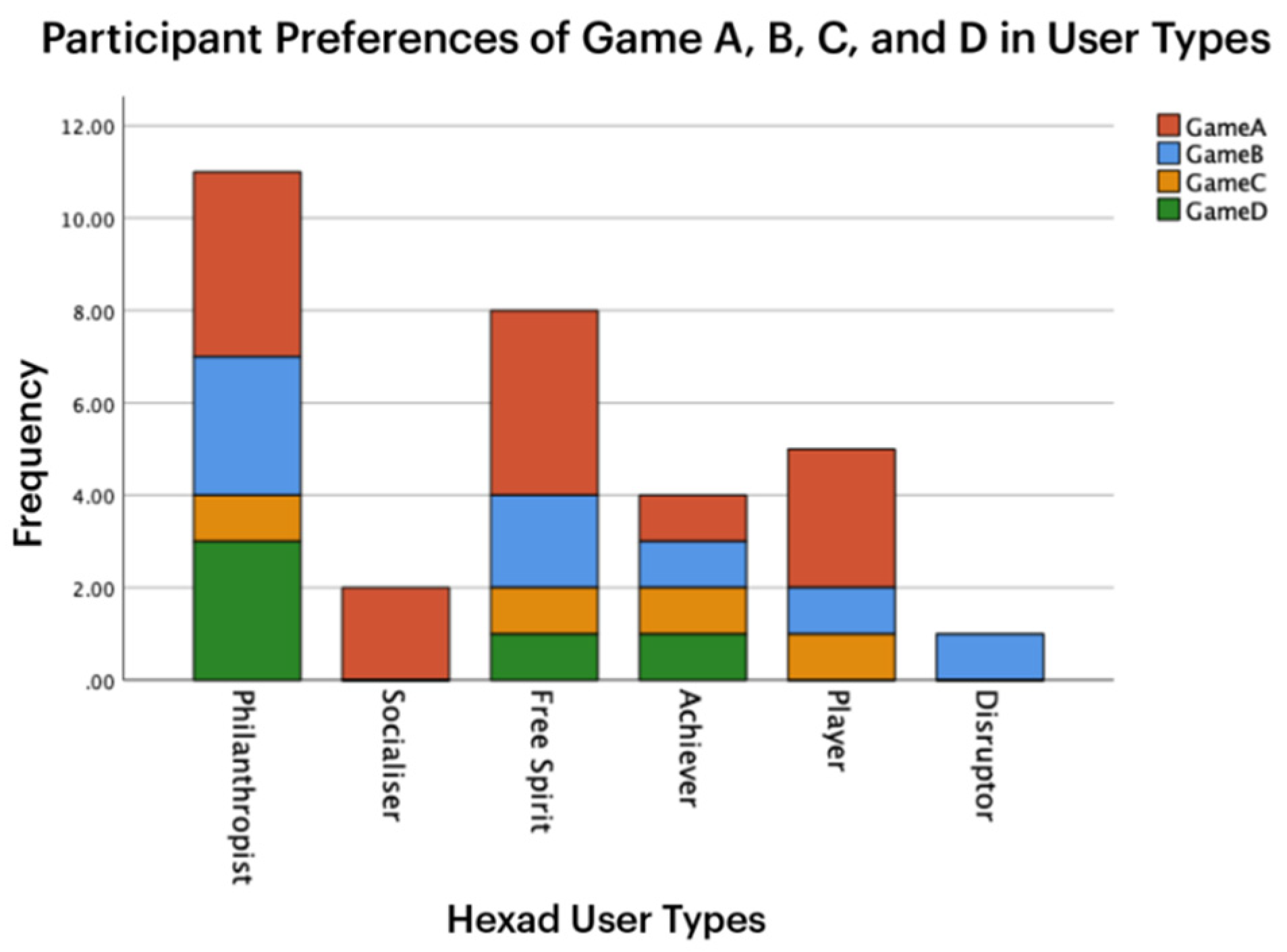

Figure 5 shows a stacked bar chart showing participants’ preference of the 4 games. It clearly shows that the proposed AR-enabled ABM (Game Type A) was the most preferable intervention with about half of the participants (7 male, 4 female) rating that they liked it the most. Non-AR ABM (Game Type B) is the second popular one with ratings from 6 participants (1 male, 5 female). On the other hand, only 3 and 4 participants rated Game Type C and Game Type D (non-ABMs) as their favourite games among all the games. We can see that the male participants tended to like Game Type A, in which there are 7 ratings from the males. The numbers of female participants who liked Game Type A and Game Type B were almost the same (4 or 5 female participants). Further,

Figure 6 shows the preference results with the Gamification User Types Hexad Scale [

44], which framework assumes six different user types are motivated differently by game design elements (either intrinsic or extrinsic motivational factors) [

45]. Given that the numbers of different user types among the participants were uneven, a comprehend analysis based on the user types could not be conducted, we discussed in the discussion section that how personalisation could benefit different user types in the ABM intervention.

3.3. Qualitative Analysis results

We conducted a thematic analysis [

48] on the semi-structured interview data to identify key themes in support of the quantitative results and answering research questions. The recordings of the interviews were transcribed and thoroughly analysed. There were three focused topics. The first is about the software interfaces, including how the participants felt when they played each of the games and what features they liked and did not. The second and third parts are about participants’ perception when comparing the AR interactive modes with the regular modes, and comparing ABM with non-ABM, respectively.

3.3.1. Positive feelings about Uplifting Moods Gamification Interfaces

Simple and Relaxing Nature: Participants highlighted the reasons why they liked Uplifting Moods were its simple gamification concept with its clear goal, which made individuals to feel calm, therapeutic and rewarding: “I really enjoyed playing them, I like the fact that when I touched them (the objects), they disappeared. I really enjoyed that they are disappearing, it's like collecting them. I felt much calmer and more concentrated on.” (P4), “It’s good that the way of playing these games is simple, I don’t have to think too much.” (P5), “I like the fact that they keep moving around. Sometimes I feel that doing things repeatedly is therapeutic.” (P6), and “The game itself is quite simple, so I will look at the moving objects. After a while, I felt a bit more relaxed, although I don’t know the reason.” (P8).

Aesthetic Gaming Arts: The game art of Uplifting Moods is another key element that the participants liked, such as the vivid and cartoony visual style, adorable and lively characters with interactive animation, relaxing and uplifting music and effective sound effects. About game style, 13 participants highlighted the visual style and artistic effects associated with ABM were favourable. For instance, “I think the style of the game is appealing and interesting.” (P2), “The visual style is cool! It’s like the polygon style.” (P14), “I really like the characters; both the character design and the animation are good! The angry dragon and the happy dragons are well-designed and cute.” (P3), “The animation is very clear, enjoyable and vibrant, reminded me that the video game I used to play.” (P17). Further, most of the participants found the music relaxing, peaceful and comforting: “The music was comforting” (P1, P13, P14, P20), and “I think the music made me feel relaxed and I am playing a relaxing game.” (P21). Participants found the sound effects were satisfying: “I also like the fact that when you press on bad ones you will get the noises that you know that one is wrong.” (P15), “The colours and music are fun and therapeutic, which made me want to play more.” (P16)

3.3.2. “Petting Lively Characters with Positive Emotion”-focused (AR-enabled ABM)

Aligned with the quantitative findings, positive perceptions towards Game Type A (AR-ABM) were found in the interviews. As the most preferable game type, Type A was found requiring more attention, effectively distracting the users from others (e.g., anxiety threats) and improving their moods overall. 9 participants highlighted its challenging and fun nature: “Petting Dragon AR mode is more difficult. Sometimes the dragons will be out of the screen or very close to the screen, which makes the game more challenging and fun. I found it quite funny and interesting.” (P1), “AR mode is more amusing and novel! It's easier to immerse myself into the game. I felt AR impressed me more, especially Petting Dragons. The dragons were flying up and down, which is more difficult so when I caught them, the feeling was stronger.” (P3), “The level of Petting Dragons AR mode is higher because dragons are flying around and blocking each other. While I was playing, I felt more excited.” (P7), “Dragons in AR is more exciting and difficult, which makes the fun time last longer.” (P22).

Participants identified that it was effective in attracting their attention, having positive distraction effects that made individuals feel more relaxed. “(Petting Dragons AR mode) It requires higher concentration for me to wait until the timing which I can touch happy dragons.” (P7), “Like today I fretted about many things in my head. But when I was playing Petting Dragons (ABM), I felt it distracted me from the annoyance. After playing it, I could feel that my mood improved. Things that are not getting in control do not bother me that much now. I felt that the mood changes from upset back to positive.” (P16), “I think I was more focused on the game when playing AR mode because it requires me to actively move my phone around.” (P21).

3.3.3. AR Interactive mode vs Regular mode

Participants felt that the AR interactive mode is exploring, engaging and interactive, especially when it applies to the ABM game. This amplifies the quantitative findings that AR options are preferable and strongly induce higher arousal states. Particularly, it adds “fun” elements with higher interactivity: “AR mode comparing non-AR, I think non-AR is rather easy and AR mode is much fun. I felt AR feature changed my emotions positively.” (P10), “Playing Petting Dragons in AR mode is more like playing a fun game. Without AR feature it was not that fun.” (P13), “AR mode made me more focused and motivated on playing the game. I also find AR is a novel feature, it is very different from other mobile apps.” (P16), “When playing non-AR version games, there was not much excitement because there was some time to wait for dragons and mushrooms showing up.” (P21), “AR mode has higher interactivity, probably because I have to move my body, which brings benefits to relaxation. Without AR mode, it’s like only blankly staring at the screen and clicking.” (P19), “I felt happy when dragons showing in my surrounding. Like they are accompanying me, which makes me concentrate on playing the game.” (P16).

The findings above can be backed with AR’s more challenging and explorative nature, highlighted by participants: “When playing non-AR games, due to their easiness, I felt conscious of the time and thinking about when will the game finish? This didn’t happen when I was playing AR mode because it was much more fun and allowed me to explore more areas and look for the targets.” (P3), “I like that I was scanning my room and I can choose where I am going to play with the scene that is going to be set.” (P4), “I think playing the 2 games in AR mode have more exploring experiences which made me more focused on playing. AR mode provided a wider area to play, it’s very impressive and fascinating.” (P7), “The playing area of the AR mode is out of the phone screen, so it made me move my phone around to see the dragons. I found that it increases the challenge level of the game, which is quite good.” (P14).

On the contrary, only a few participants preferred the regular mode (no-AR) due to its easiness of playing and controlling. This also reflects on the results of dominance that the AR feature made some of the participants feel dominated after they played the AR versions. “I found myself was focusing on the non-AR games more easily.” (P5), “I found AR mode is hard. I’d never played any AR games before. When I was playing, I had to move my phone and touch the food or dragons, it’s very hard. The other 2 games in regular mode then were better, like very easy and good.” (P9). Interestingly, P2 mentioned that: “Playing Non-AR games allows me sitting, which made me feel more dominant.” while the participant preferred the AR interactive mode more. How to improve the designs will be discussed in the implication section below.

3.3.4. ABM vs non-ABM

Lastly, we further delved into comparisons between ABM and non-ABM game types. Participants who preferred the ABM (i.e., Petting Lively Characters with Positive Emotion) perceived that the happy dragons made them actually happier, most likely due to the lively emotions expressed by the dragon characters. “Compared to playing Collecting Food non-AR, playing Petting Dragons non-AR makes me happier! Not sure why that is.” (P5), “Comparing Collecting Food and Petting Dragons, I found that I want to play Petting Dragons more. Probably because of the design. Dragons have facial expressions and are more interactive, flowers and mushrooms are just two normal objects. When I was playing Collecting Food, I found it cute at the beginning, but after a while, I felt it was a bit too much. I guess it’s because there are no emotions in the plants.” (P16). “the food one (non-ABM) was too repetitive.” (P24).

4. Discussion

Designing an engaging ABM game could be challenging due to the essence of ABM is a repeated training that may not easily attract users. In this study, it is highlighted that AR can increase the effectiveness of gamified ABM training in improving our moods. Overall, the result from our quantitative analysis has shown that this approach is more effective and preferable in positively shifting people's moods than other options including non-AR ABM and non-ABM gamification. From our qualitative data analysis, we confirm the provision of AR helps users motivated and brings certain benefits of feature personalisation meeting different types of users’ needs [

44,

45]. With interactive and immersive characteristics of AR, the participants highlighted the proposed AR-enabled ABM more challenging and fun, aligning with the fact that fun elements in gaming are associated with being challenging [

49]. Instead of focusing only on treating specific anxiety/cognitive disorders as in existing gamified ABM or AR interventions, this study highlights the broader effect of the AR ABM game in improving people’s moods in general and could potentially help design an effective long-term daily interactive intervention.

For designing AR ABM games, personalisation should be considered since it has been shown to be effective in interactive technology and game designs [

50]. While the AR ABM mode led to the most positive outcome and was the most preferable game in this study, personalisation can also be key in AR and ABM gamification design considering the diversity of users (e.g. along with Hexad User Types in

Figure 6 and two participants found AR made them nervous due to unfamiliarity, resulting in preferring the non-AR ABM mode). Instead, offering the AR mode as an optional feature would be useful and may suit different types of users.

4.1. Implications for Designing ABM Mental Wellbeing Interventions

To help researchers, software developers and designers to implement AR-enabled ABM gamification for mental wellbeing management in an engaging way, here we discuss design implications on three key elements below.

Aesthetic and Music: the design of games including visual style and music is an important way to tell a story that makes users feel connected and create affection towards the game, which may increase the meaningfulness of playing and users’ engagement [

20,

51]. In the interviews conducted after the participants played

Uplifting Moods, most of the participants highlighted that they liked the game art and enjoyed the music and sound effects of the game, and they felt that the adorable gaming arts and amusing music made them happy and relaxed. Studies also show that the pleasure cycle of music involves brain regions that comprise the reward system [

52,

53]. The fact that music is effective in deriving pleasure [

20] could be one of the reasons why no significant differences were found in the valence values after playing the 4 games in Uplifting Moods since all the background music was the same, pleasurable for the participants.

Level Progression: Games with progression mechanisms could make the gaming experience more exciting [

52]. Designing proper and achievable levels in ABM games would be beneficial in avoiding the repetitiveness of ABM and attracting users. As P4 commented on Uplifting Moods: “

I like that the game speed-ups as I go through the games, it starts quite slowly, like at the beginning only a few mushrooms and then there were much more mushrooms, like in a harder level, I like that there was a progress, it’s enjoyable.” P10 also suggested that: “

The game is rather simple and easy; maybe more levels could make a difference. Like getting harder or showing different characters etc.”

Socialisation: Social involvement with other players has been found to increase the meaningfulness of playing [

51]. For some of the participants in this study, socialising with friends motivates them to play games. Functions like sharing their score with friends, having a leaderboard could potentially bring more fun to the game (P7 and P17 suggested during the interviews). However, these competitive types of game elements should be carefully designed because it is important to avoid making users too nervous or excessively competitive which induces anxious feelings when they want to achieve better performance to compete with their friends [

54]. Making the game collaborative instead of competitive may be a good way to not only attract users who like socialising to play but also make the gaming process more enjoyable and rewarding, which may result in stronger intentions to play the game again [

55].

4.2. Limitations and Future Work

Some limitations in this work can guide potential future work. Firstly, the game

Uplifting Moods has limited instruction for AR. While the authors provided guidance when conducting the study, a clearer and interactive in-game instruction can help users who are not familiar with AR to proceed with the game with a better user experience. Secondly, different mobile phone devices, models and capacity may lead to different playing experiences in AR mode. While the development of

Uplifting Moods uses Unity3D and ARCore as a game engine and AR development environment, some instabilities can be found in giving feedback and switching rounds in the game depending on the phone factors of the participants. Finally, while we calculated Hexad User Types of the participants to better understand each individual, this study did not focus on exploring users’ other psychophysiological parameters which are important in personalisation and effective intervention [

56,

57,

58]. Future work will also benefit from advanced machine learning approaches [

59,

60] in tracking one's physiological signatures and offering micro-intervention for better mental wellbeing on a daily basis.

5. Conclusions

In this paper we have presented our novel AR-enabled ABM mobile application, Uplifting Moods. The data collection and mixed study analysis results showed that participants tended to feel more cheerful after playing the AR-ABM game type (condition A) with the significantly increased arousal levels and fun, exploring, and challenging features. The same type was also rated as the most preferable game compared to the other 3 game types. Design implications for making AR-enabled ABM games effective and interactive were then developed, which focused on characteristics of aesthetics, music, level progression and socialisation. Overall, this study has contributed to the understandings of how the AR feature and gamification in providing benefits in ABM and contributes to the possibility of building greater effectiveness in novel treatments and improvements in people’s mental wellbeing in the real-life context.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.C, S.S.J; Investigation, Y.Y., Y.C; methodology, Y.Y., Y.C; design artefacts, Y.Y.; data collection and analysis, Y.Y; manuscript preparation, Y.Y., S.S.J, Y.C; overall supervision, Y.C.; project administration, Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol is approved by the University College London Interaction Centre ethics committee (ID Number: UCLIC/1920/006/Staff/Cho).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank our participants who participated in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABM |

Attention Bias Modification |

| AR |

Augmented Reality |

| HSPS |

Highly Sensitive Person Scale |

| SAM |

Self Assessment Manikin |

References

- Ritchie, H.; Roser, M. Mental Health. Our World in Data 2018.

- Bandelow, B.; Michaelis, S. Epidemiology of Anxiety Disorders in the 21st Century. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2015, 17, 327–335.

- Torales; O’Higgins; Castaldelli-Maia; J. M The Outbreak of COVID-19 Coronavirus and Its Impact on Global Mental Health - Julio Torales, Marcelo O’Higgins, João Mauricio Castaldelli-Maia, Antonio Ventriglio, 2020.

- World Health Organization Substantial Investment Needed to Avert Mental Health Crisis Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/14-05-2020-substantial-investment-needed-to-avert-mental-health-crisis (accessed on 23 August 2021).

- Kessler, R.C.; Angermeyer, M.; Anthony, J.C.; De Graaf, R.; Demyttenaere, K.; GASQUET, I.; DE GIROLAMO, G.; GLUZMAN, S.; GUREJE, O.; HARO, J.M.; et al. Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of Mental Disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry 2007, 6, 168–176.

- Pine, D.S.; Helfinstein, S.M.; Bar-Haim, Y.; Nelson, E.; Fox, N.A. Challenges in Developing Novel Treatments for Childhood Disorders: Lessons from Research on Anxiety. Neuropsychopharmacology 2009, 34, 213–228. [CrossRef]

- Hakamata, Y.; Lissek, S.; Bar-Haim, Y.; Britton, J.C.; Fox, N.; Leibenluft, E.; Ernst, M.; Pine, D.S. Attention Bias Modification Treatment: A Meta-Analysis towards the Establishment of Novel Treatment for Anxiety. Biol Psychiatry 2010, 68, 982–990. [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Julier, S.J.; Bianchi-Berthouze, N. Instant Stress: Detection of Perceived Mental Stress Through Smartphone Photoplethysmography and Thermal Imaging. JMIR Mental Health 2019, 6, e10140. [CrossRef]

- Rohani, D.A.; Quemada Lopategui, A.; Tuxen, N.; Faurholt-Jepsen, M.; Kessing, L.V.; Bardram, J.E. MUBS: A Personalized Recommender System for Behavioral Activation in Mental Health. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; ACM: Honolulu HI USA, April 21 2020; pp. 1–13.

- Mogg, K.; Waters, A.M.; Bradley, B.P. Attention Bias Modification (ABM): Review of Effects of Multisession ABM Training on Anxiety and Threat-Related Attention in High-Anxious Individuals. Clinical Psychological Science 2017, 5, 698–717. [CrossRef]

- Naim, R.; Kivity, Y.; Bar-Haim, Y.; Huppert, J.D. Attention and Interpretation Bias Modification Treatment for Social Anxiety Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial of Efficacy and Synergy. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 2018, 59, 19–30. [CrossRef]

- Dennis, T.A.; O’Toole, L.J. Mental Health on the Go: Effects of a Gamified Attention-Bias Modification Mobile Application in Trait-Anxious Adults. Clinical Psychological Science 2014, 2, 576–590. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ying, J.; Song, G.; Fung, D.S.; Smith, H. Gamified Cognitive Bias Modification Interventions for Psychiatric Disorders: Review. JMIR Ment Health 2018, 5, e11640. [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.; Intrilligator, J.; Hillier, C. Chimpshop and Alcohol Reduction – Using Technology to Change Behaviour. Perspect Public Health 2015, 135, 126–127. [CrossRef]

- Dennis-Tiwary, T.A.; Egan, L.J.; Babkirk, S.; Denefrio, S. For Whom the Bell Tolls: Neurocognitive Individual Differences in the Acute Stress-Reduction Effects of an Attention Bias Modification Game for Anxiety. Behav Res Ther 2016, 77, 105–117. [CrossRef]

- Notebaert, L.; Grafton, B.; Clarke, P.J.; Rudaizky, D.; Chen, N.T.; MacLeod, C. Emotion-in-Motion, a Novel Approach for the Modification of Attentional Bias: An Experimental Proof-of-Concept Study. JMIR Serious Games 2018, 6, e10993. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.; Deterding, S.; Kuhn, K.-A.; Staneva, A.; Stoyanov, S.; Hides, L. Gamification for Health and Wellbeing: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Internet Interventions 2016, 6, 89–106. [CrossRef]

- Birk, M.V.; Wadley, G.; Abeele, V.V.; Mandryk, R.; Torous, J. Video Games for Mental Health. interactions 2019, 26, 32–36. [CrossRef]

- Dennis-Tiwary, T.A.; Denefrio, S.; Gelber, S. Salutary Effects of an Attention Bias Modification Mobile Application on Biobehavioral Measures of Stress and Anxiety during Pregnancy. Biological Psychology 2017, 127, 148–156. [CrossRef]

- Lazarov, A.; Pine, D.S.; Bar-Haim, Y. Gaze-Contingent Music Reward Therapy for Social Anxiety Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. AJP 2017, 174, 649–656. [CrossRef]

- Kress, L.; Aue, T. Learning to Look at the Bright Side of Life: Attention Bias Modification Training Enhances Optimism Bias. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2019, 13. [CrossRef]

- Boendermaker, W.J.; Maceiras, S.S.; Boffo, M.; Wiers, R.W. Attentional Bias Modification With Serious Game Elements: Evaluating the Shots Game. JMIR Serious Games 2016, 4, e6464. [CrossRef]

- Edbrooke-Childs, J.; Smith, J.; Rees, J.; Edridge, C.; Calderon, A.; Saunders, F.; Wolpert, M.; Deighton, J. An App to Help Young People Self-Manage When Feeling Overwhelmed (ReZone): Protocol of a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Research Protocols 2017, 6, e7019. [CrossRef]

- Edridge, C.; Deighton, J.; Wolpert, M.; Edbrooke-Childs, J. The Implementation of an mHealth Intervention (ReZone) for the Self-Management of Overwhelming Feelings Among Young People. JMIR Formative Research 2019, 3, e11958. [CrossRef]

- Edridge, C.; Wolpert, M.; Deighton, J.; Edbrooke-Childs, J. An mHealth Intervention (ReZone) to Help Young People Self-Manage Overwhelming Feelings: Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2020, 22, e14223. [CrossRef]

- Pieters, E.K.; De Raedt, R.; Enock, P.M.; De Putter, L.M.S.; Braham, H.; McNally, R.J.; Koster, E.H.W. Examining a Novel Gamified Approach to Attentional Retraining: Effects of Single and Multiple Session Training. Cogn Ther Res 2017, 41, 89–105. [CrossRef]

- Botella, C.; Riva, G.; Gaggioli, A.; Wiederhold, B.K.; Alcaniz, M.; Baños, R.M. The Present and Future of Positive Technologies. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 2012, 15, 78–84. [CrossRef]

- Acar, D.; Miman, M.; Akirmak, O.O. Treatment of Anxiety Disorders Patients Through EEG and Augmented Reality. 2014, 3, 10.

- Wiederhold, B.K.; Miller, I.; Wiederhold, M.D. Augmenting Behavioral Healthcare: Mobilizing Services with Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality. In Digital Health: Scaling Healthcare to the World; Rivas, H., Wac, K., Eds.; Health Informatics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 123–137 ISBN 978-3-319-61446-5.

- Hugues, O.; Fuchs, P.; Nannipieri, O. New Augmented Reality Taxonomy: Technologies and Features of Augmented Environment. In Handbook of Augmented Reality; Furht, B., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, 2011; pp. 47–63 ISBN 978-1-4614-0064-6.

- Wang, K.; Julier, S.J.; Cho, Y. Attention-Based Applications in Extended Reality to Support Autistic Users: A Systematic Review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 15574–15593. [CrossRef]

- Barsom, E.Z.; Graafland, M.; Schijven, M.P. Systematic Review on the Effectiveness of Augmented Reality Applications in Medical Training. Surg Endosc 2016, 30, 4174–4183. [CrossRef]

- Collins, B.N.; Brandon, T.H. Effects of Extinction Context and Retrieval Cues on Alcohol Cue Reactivity among Nonalcoholic Drinkers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2002, 70, 390–397. [CrossRef]

- Chicchi Giglioli, I.A.; Pallavicini, F.; Pedroli, E.; Serino, S.; Riva, G. Augmented Reality: A Brand New Challenge for the Assessment and Treatment of Psychological Disorders.

- Vinci, C.; Brandon, K.O.; Kleinjan, M.; Brandon, T.H. The Clinical Potential of Augmented Reality. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 2020, 27, e12357. [CrossRef]

- Botella, C.; Bretón-López, J.; Quero, S.; Baños, R.; García-Palacios, A. Treating Cockroach Phobia With Augmented Reality. Behavior Therapy 2010, 41, 401–413. [CrossRef]

- Botella, C.; Breton-López, J.; Quero, S.; Baños, R.M.; García-Palacios, A.; Zaragoza, I.; Alcaniz, M. Treating Cockroach Phobia Using a Serious Game on a Mobile Phone and Augmented Reality Exposure: A Single Case Study. Computers in Human Behavior 2011, 27, 217–227. [CrossRef]

- Ocay, A.B.; Rustia, R.A.; Palaoag, T.D. Utilizing Augmented Reality in Improving the Frustration Tolerance of ADHD Learners: An Experimental Study. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Digital Technology in Education - ICDTE 2018; ACM Press: Bangkok, Thailand, 2018; pp. 58–63.

- Nielsen, J. Coordinating User Interfaces for Consistency. SIGCHI Bull. 1989, 20, 63–65. [CrossRef]

- Aron, E.N.; Aron, A. Sensory-Processing Sensitivity and Its Relation to Introversion and Emotionality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1997, 73, 345–368. [CrossRef]

- Neal, J.A.; Edelmann, R.J.; Glachan, M. Behavioural Inhibition and Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression: Is There a Specific Relationship with Social Phobia? British Journal of Clinical Psychology 2002, 41, 361–374. [CrossRef]

- Benham, G. The Highly Sensitive Person: Stress and Physical Symptom Reports. Personality and Individual Differences 2006, 40, 1433–1440. [CrossRef]

- Bradley, M.M.; Lang, P.J. Measuring Emotion: The Self-Assessment Manikin and the Semantic Differential. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 1994, 25, 49–59. [CrossRef]

- Tondello, G.F.; Wehbe, R.R.; Diamond, L.; Busch, M.; Marczewski, A.; Nacke, L.E. The Gamification User Types Hexad Scale. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2016 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, October 15 2016; pp. 229–243.

- Marczewski, A. Even Ninja Monkeys Like to Play: Unicorn Edition. 2015, 69–84.

- Russell, J.A. A Circumplex Model of Affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1980, 39, 1161–1178. [CrossRef]

- Yerkes, R.M.; Dodson, J.D. The Relation of Strength of Stimulus to Rapidity of Habit-Formation. Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology 1908, 18, 459–482. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006, 3, 77–101. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.; Woolley, J.; Sherrick, B.; Bowman, N.D.; Oliver, M.B. Fun Versus Meaningful Video Game Experiences: A Qualitative Analysis of User Responses. Comput Game J 2017, 6, 63–79. [CrossRef]

- Orji, R.; Tondello, G.F.; Nacke, L.E. Personalizing Persuasive Strategies in Gameful Systems to Gamification User Types. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–14 ISBN 978-1-4503-5620-6.

- Laato, S.; Rauti, S.; Islam, A.K.M.N.; Sutinen, E. Why Playing Augmented Reality Games Feels Meaningful to Players? The Roles of Imagination and Social Experience. Computers in Human Behavior 2021, 121, 106816. [CrossRef]

- Ljungkvist, P.; Mozelius, P. Educational Games for Self Learning in Introductory Programming Courses -a Straightforward Design Approach with Progression Mechanisms; 2012;

- Stark, E.A.; Vuust, P.; Kringelbach, M.L. Chapter 7 - Music, Dance, and Other Art Forms: New Insights into the Links between Hedonia (Pleasure) and Eudaimonia (Well-Being). In Progress in Brain Research; Christensen, J.F., Gomila, A., Eds.; The Arts and The Brain; Elsevier, 2018; Vol. 237, pp. 129–152.

- Gilbert, P.; McEwan, K.; Bellew, R.; Mills, A.; Gale, C. The Dark Side of Competition: How Competitive Behaviour and Striving to Avoid Inferiority Are Linked to Depression, Anxiety, Stress and Self-Harm. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice 2009, 82, 123–136. [CrossRef]

- Plass, J.L.; O’keefe, P.A.; Homer, B.D.; Perlin, K. The Impact of Individual, Competitive, and Collaborative Mathematics Game Play on Learning, Performance, and Motivation 2013.

- Joshi, J.; Wang, K.; Cho, Y. PhysioKit: An Open-Source, Low-Cost Physiological Computing Toolkit for Single- and Multi-User Studies. Sensors 2023, 23, 8244. [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Julier, S.J.; Marquardt, N.; Bianchi-Berthouze, N. Robust Tracking of Respiratory Rate in High-Dynamic Range Scenes Using Mobile Thermal Imaging. Biomed. Opt. Express, BOE 2017, 8, 4480–4503. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, J.; Cho, Y. iBVP Dataset: RGB-Thermal rPPG Dataset with High Resolution Signal Quality Labels. Electronics 2024, 13, 1334. [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y. Rethinking Eye-Blink: Assessing Task Difficulty through Physiological Representation of Spontaneous Blinking. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–12.

- Joshi, J.; Agaian, S.S.; Cho, Y. FactorizePhys: Matrix Factorization for Multidimensional Attention in Remote Physiological Sensing. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 37.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).