Submitted:

22 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2.1. Databases Searched

2.2.. Keywords and Search Terms

2.2.1. Primary Keywords

2.2.2. Search Terms

- (“Nerve Guidance Conduits” OR “NGCs” OR “Artificial Nerve Grafts” OR “Neural Scaffolds”) AND (“Structural Design” OR “ Porous NGC” OR “Grooved NGC” OR “Fiber filled NGC” OR “Hydrogel filled NGC” OR “Nano-sponge filled NGC”) AND (“Axonal Misdirection” OR “Axonal Misrouting” OR “Axonal Fasciculation” OR “Reinnervation Mismatch” OR “Targeted Reinnervation” OR “Intraneural Branching Topography” OR “Intraneural Plexus Formation” OR “Selective Regeneration” OR “Preferential Regeneration”)

- (“Nerve Guidance Conduits” OR “NGCs” OR “Artificial Nerve Grafts” OR “Neural Scaffolds”) AND (“Individualized NGC” OR “3D Scanning” OR “Machine Learning”)

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

- Peer-reviewed studies

- Experimental and clinical studies assessing axonal misdirection following NGC repair

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

- Non-English studies

- NGC characterization studies

- Functionally enhanced NGCs

- Articles without access to full-text for detailed review

2.5. Screening Process

- Step 1: Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance.

- Step 2: Selected articles underwent full-text review to ensure they met inclusion criteria.

- Step 3: Articles were categorized based on their focus: nerve injury and recovery, axonal misdirection, NGC design strategies, future perspectives

3. Nerve Injury and Recovery: A Pathophysiological Overview

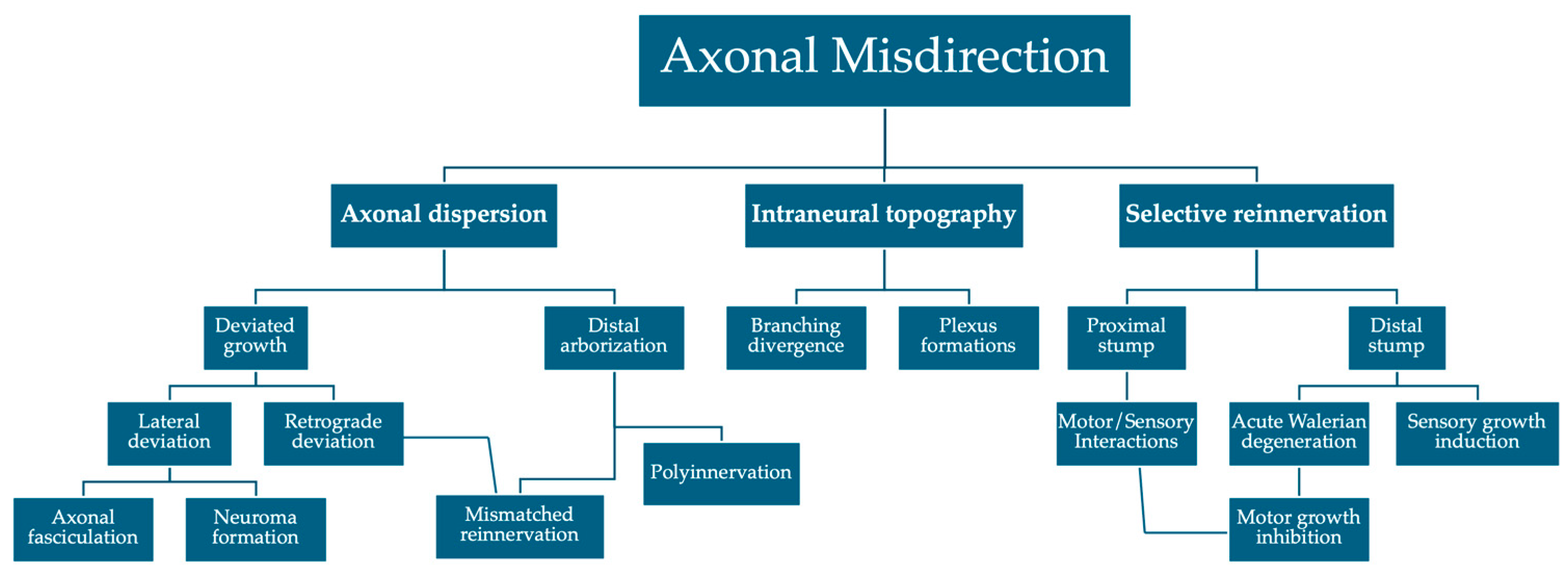

4. Axonal Misdirection

4.1. Axonal Dispersion

4.2. Selective Axonal Reinnervation

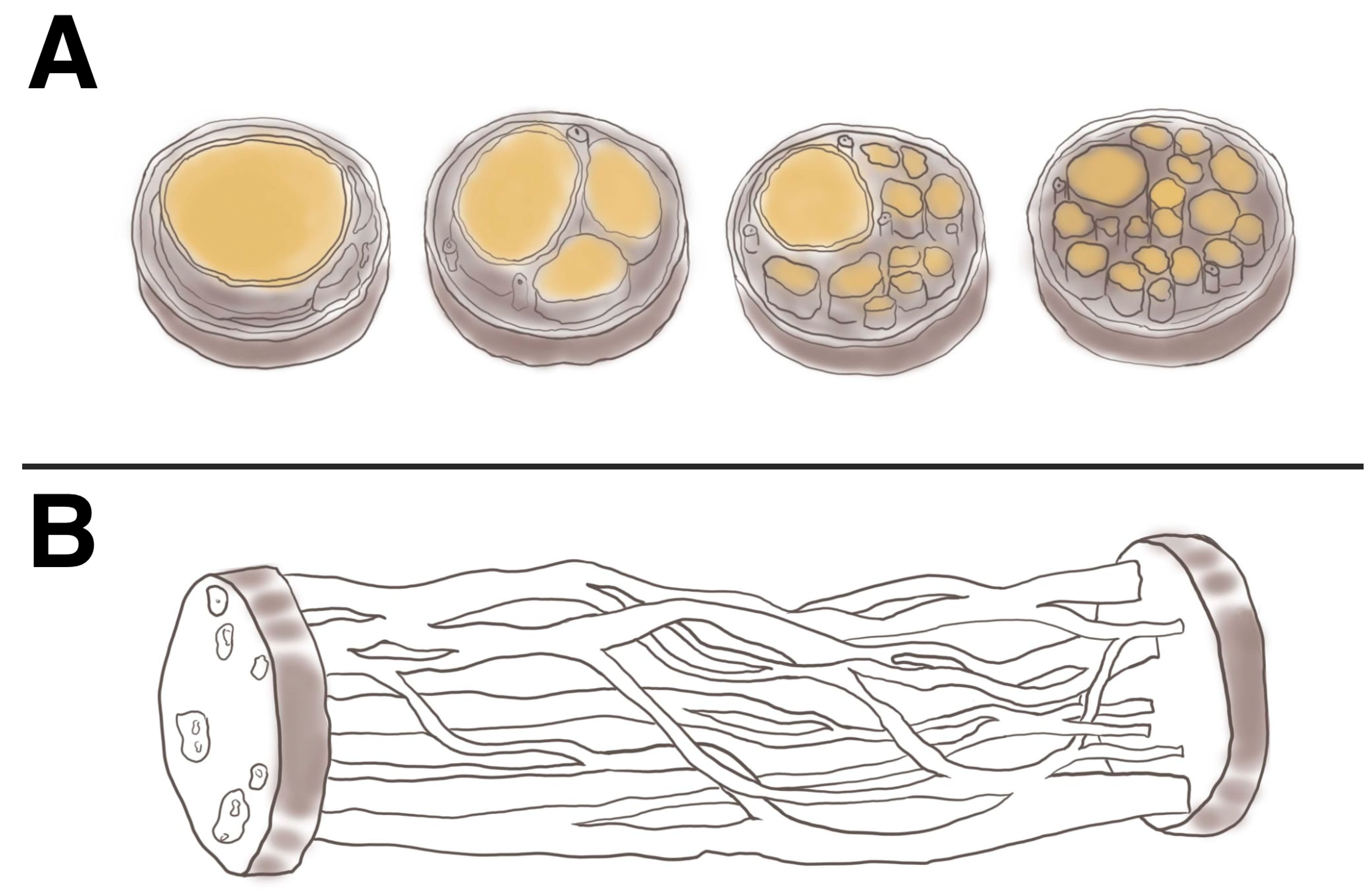

4.3. Intraneural Branching Topography

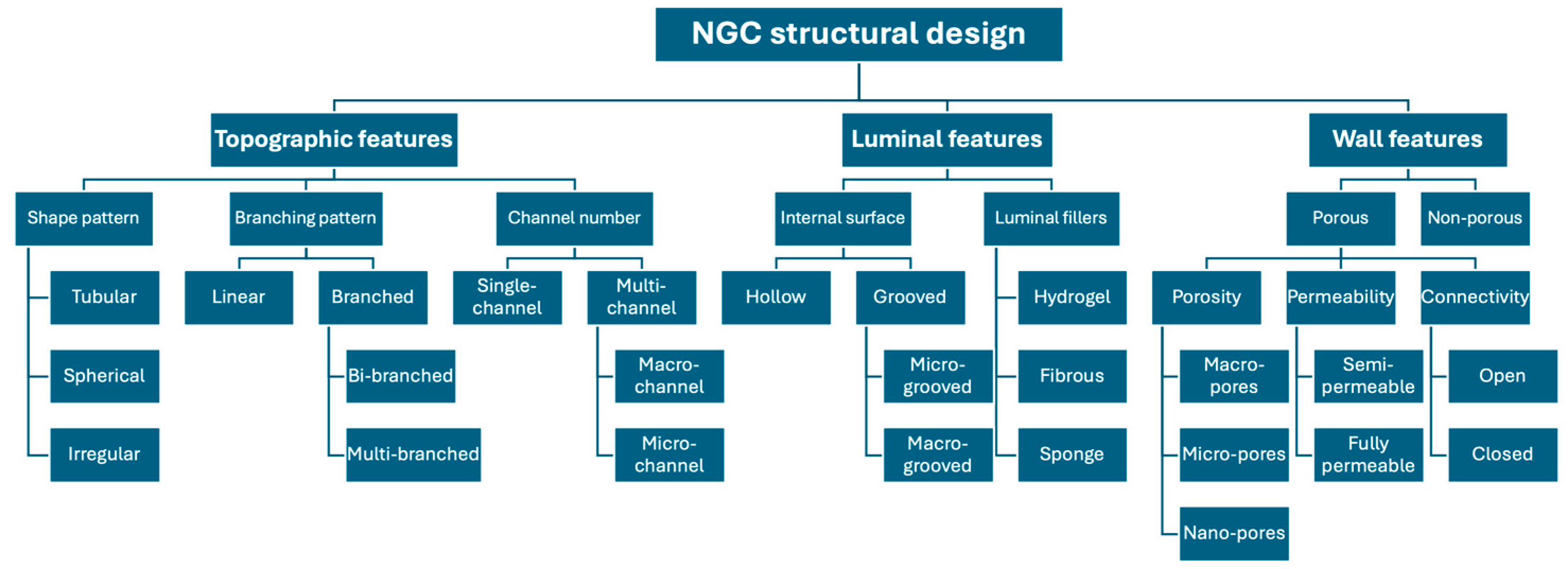

5. NGC Structural Features and Axonal Direction

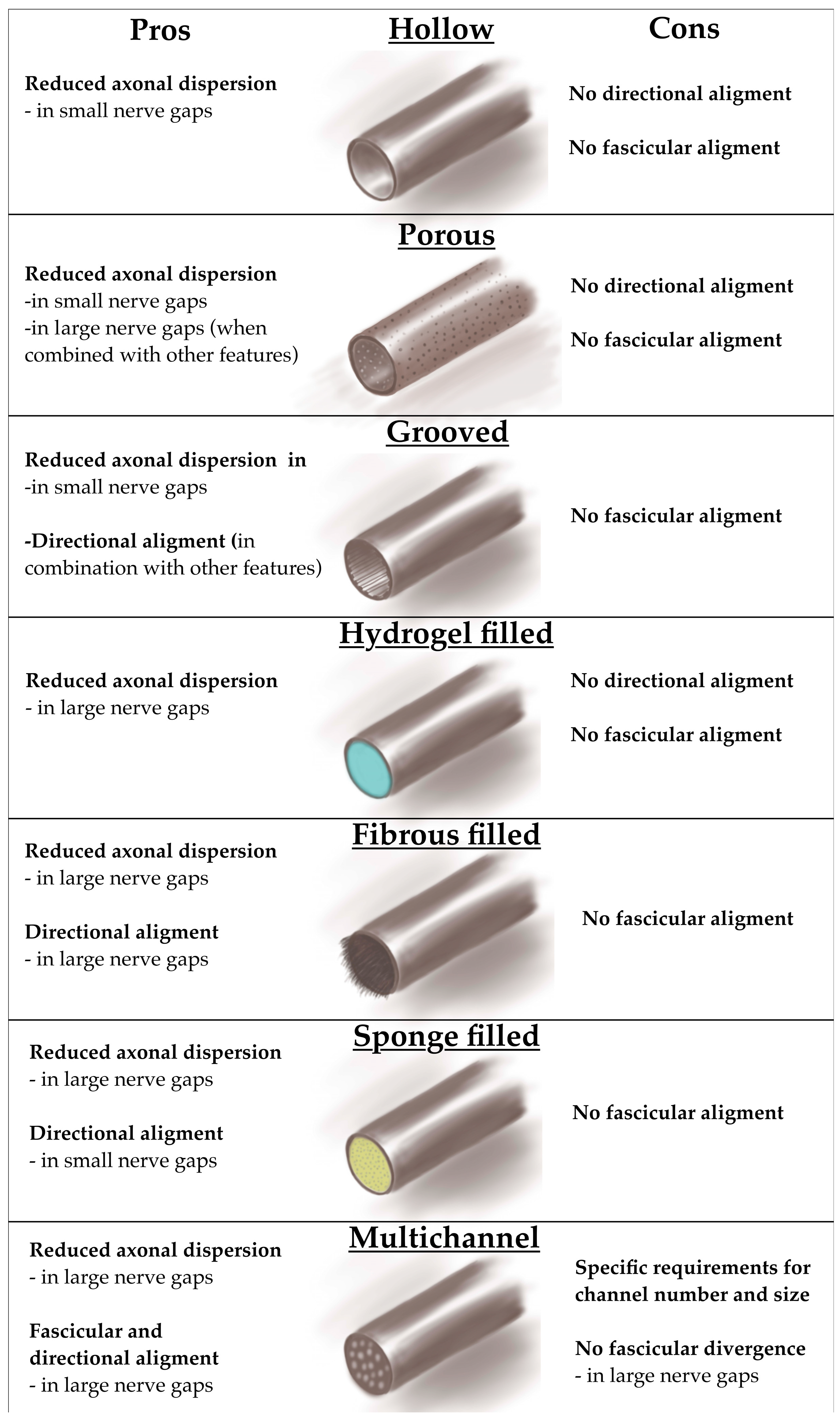

5.1. Single Hollow Design

5.2. Porous Single Hollow Design

5.3. Grooved Single Hollow Design

5.4. Filled Single Hollow Design

5.4.1. Hydrogel-Filled Single-Hollow Design

5.4.2. Fibrous-Filled Single-Hollow Design

5.4.3. Nanosponge-Filled Single-Hollow Design

5.5. Multichannel Design

6. Key Perspectives

7. Future Perspectives

8. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Acknowledgments

References

- Rasulić, L.; Nikolić, L.; Lepić, M.; Savić, A.; Vitošević, F.; Novaković, N.; Radojević, S.; Mićić, A.; Lepić, S.; Mandić-Rajčević, S. Useful functional recovery and quality of life after surgical treatment of peroneal nerve injuries. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 1005483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Córdoba-Mosqueda, M.E.; Rasulić, L.; Savić, A.; Grujić, J.; Vitošević, F.; Lepić, M.; Mićić, A.; Radojević, S.; Mandić-Rajčević, S.; Jovanović, I.; et al. Quality of life and satisfaction in patients surgically treated for cubital tunnel syndrome. Neurol. Res. 2022, 45, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faroni, A.; Mobasseri, S.A.; Kingham, P.J.; Reid, A.J. Peripheral nerve regeneration: Experimental strategies and future perspectives. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015, 82-83, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slutsky, D. A Practical Approach to Nerve Grafting in the Upper Extremity. Atlas Hand Clin. 2005, 10, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLeonibus, A.; Rezaei, M.; Fahradyan, V.; Silver, J.; Rampazzo, A.; Gharb, B.B. A meta-analysis of functional outcomes in rat sciatic nerve injury models. Microsurgery 2021, 41, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FF IJ, Nicolai JP, Meek MF. Sural nerve donor-site morbidity: thirty-four years of follow-up. Ann Plast Surg. 2006, 57, 391–395.

- Muheremu, A.; Ao, Q. Past, Present, and Future of Nerve Conduits in the Treatment of Peripheral Nerve Injury. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayavenkataraman, S. Nerve guide conduits for peripheral nerve injury repair: A review on design, materials and fabrication methods. Acta Biomaterialia 2020, 106, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supra, R.; Agrawal, D.K. Peripheral Nerve Regeneration: Opportunities and Challenges. J. Spine Res. Surg. 2023, 05, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grinsell, D.; Keating, C.P. Peripheral Nerve Reconstruction after Injury: A Review of Clinical and Experimental Therapies. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 698256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheib, J.; Höke, A. Advances in peripheral nerve regeneration. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2013, 9, 668–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.; Bai, J.; Zhou, X.; Chen, N.; Jiang, Q.; Ren, Z.; Li, X.; Su, T.; Liang, L.; Jiang, W.; et al. Electrical stimulation with polypyrrole-coated polycaprolactone/silk fibroin scaffold promotes sacral nerve regeneration by modulating macrophage polarisation. Biomater Transl. 2024, 5, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amalakanti, S.; Mulpuri, R.P.; Avula, V.C.R. Recent advances in biomaterial design for nerve guidance conduits: a narrative review. Adv. Technol. Neurosci. 2024, 1, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.P.; Lokai, T.; Albin, B.; Yang, I.H. A Review on the Technological Advances and Future Perspectives of Axon Guidance and Regeneration in Peripheral Nerve Repair. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Z.; Yang, Y.; Deng, J.; Rahman, M.S.U.; Sun, C.; Xu, S. Physical Stimulation Combined with Biomaterials Promotes Peripheral Nerve Injury Repair. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ruiter, G.C.W.; Spinner, R.J.; Verhaagen, J.; Malessy, M.J.A. Misdirection and guidance of regenerating axons after experimental nerve injury and repair. J. Neurosurg. 2014, 120, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Yao, R.; Zhao, J.; Chen, K.; Duan, L.; Wang, T.; Zhang, S.; Guan, J.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, X.; et al. Implantable nerve guidance conduits: Material combinations, multi-functional strategies and advanced engineering innovations. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 11, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, M.D.; Naghieh, S.; McInnes, A.D.; Schreyer, D.J.; Chen, X. Regeneration of peripheral nerves by nerve guidance conduits: Influence of design, biopolymers, cells, growth factors, and physical stimuli. Progress in Neurobiology 2018, 171, 125–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker; Naghieh, S.; McInnes, A.D.; Schreyer, D.J.; Chen, X. Strategic Design and Fabrication of Nerve Guidance Conduits for Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Biotechnol. J. 2018, 13, e1700635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, L.; de Ruiter, G.C.; Wang, H.; Knight, A.M.; Spinner, R.J.; Yaszemski, M.J.; Windebank, A.J.; Pandit, A. Controlling dispersion of axonal regeneration using a multichannel collagen nerve conduit. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 5789–5797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, A.; Rossettie, S.; Rafael, J.; Cox, C.; Ducic, I.; Mackay, B. Assessment of Motor Function in Peripheral Nerve Injury and Recovery. Orthop. Rev. 2022, 14, 37578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; He, B.; Zhu, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Zhou, X.; Zheng, C.; Li, P.; Zhu, S.; Zhu, J.; B, H.; et al. Factors predicting sensory and motor recovery after the repair of upper limb peripheral nerve injuries. Neural Regen. Res. 2014, 9, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adidharma, W.; Khouri, A.N.; Lee, J.C.; Vanderboll, K.; Kung, T.A.; Cederna, P.S.; Kemp, S.W.P. Sensory nerve regeneration and reinnervation in muscle following peripheral nerve injury. Muscle Nerve 2022, 66, 384–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.G.; Pang, R.P.; Zhou, L.J.; Wei, X.H.; Zang, Y. Neuropathic Pain: Sensory Nerve Injury or Motor Nerve Injury? Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016, 904, 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Saragaglia, D.; Hassan Chamseddine, A. Injuries to Peripheral Nerves. Traumatology for the Emergency Doctor; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, H.; Perera, N. Peripheral nerve injury: an update. Orthop. Trauma 2020, 34, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Zhou, Y.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, W. Wallerian degeneration: From mechanism to disease to imaging. Heliyon 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, J.; Li, R.; Ma, S.; Ying, Z. Schwann cell promotes macrophage recruitment through IL-17B/IL-17RB pathway in injured peripheral nerves. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 113753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras, E.; Bolívar, S.; Navarro, X.; Udina, E. New insights into peripheral nerve regeneration: The role of secretomes. Exp. Neurol. 2022, 354, 114069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benga, A.; Zor, F.; Korkmaz, A.; Marinescu, B.; Gorantla, V. The neurochemistry of peripheral nerve regeneration. Indian J. Plast. Surg. 2017, 50, 005–015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattin, A.-L.; Lloyd, A.C. The multicellular complexity of peripheral nerve regeneration. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2016, 39, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Gao, X.; Qian, Y.; Sun, W.; You, Z.; Fan, C. Biomechanical microenvironment in peripheral nerve regeneration: from pathophysiological understanding to tissue engineering development. Theranostics 2022, 12, 4993–5014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotterman, T.M.; García, V.V.; Housley, S.N.; Nardelli, P.; Sierra, R.; Fix, C.E.; et al. Structural Preservation Does Not Ensure Function at Sensory Ia-Motoneuron Synapses following Peripheral Nerve Injury and Repair. J Neurosci. 2023, 43, 4390–4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koerber, H.; Seymour, A.W.; Mendell, L.M. Mismatches between peripheral receptor type and central projections after peripheral nerve regeneration. Neurosci. Lett. 1989, 99, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dun, X.-P.; Parkinson, D.B. Visualizing Peripheral Nerve Regeneration by Whole Mount Staining. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0119168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ruiter, G.C.; Spinner, R.J.; Malessy, M.J.; Moore, M.J.; Sorenson, E.J.; Currier, B.L.; et al. Accuracy of motor axon regeneration across autograft, single-lumen, and multichannel poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nerve tubes. Neurosurgery 2008, 63, 144–153, discussion 153–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puigdellívol-Sánchez, A.; Prats-Galino, A.; Molander, C. Estimations of topographically correct regeneration to nerve branches and skin after peripheral nerve injury and repair. Brain Res. 2006, 1098, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Qin, B. [Research progress of peripheral nerve mismatch regeneration]. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi 2021, 35, 387–391. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.I.; A Gurjar, A.; Talukder, M.A.H.; Rodenhouse, A.; Manto, K.; O’brien, M.; Karuman, Z.; Govindappa, P.K.; Elfar, J.C. Purposeful Misalignment of Severed Nerve Stumps in a Standardized Transection Model Reveals Persistent Functional Deficit With Aberrant Neurofilament Distribution. Mil. Med. 2021, 186, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, T. Peripheral Nerve Regeneration and Muscle Reinnervation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, T. Peripheral Nerve Regeneration and Muscle Reinnervation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, W.T.; Yao, L.; Abu-Rub, M.T.; O'Connell, C.; Zeugolis, D.I.; Windebank, A.J.; Pandit, A.S. The effect of intraluminal contact mediated guidance signals on axonal mismatch during peripheral nerve repair. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 6660–6671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, L.; de Ruiter, G.C.; Wang, H.; Knight, A.M.; Spinner, R.J.; Yaszemski, M.J.; Windebank, A.J.; Pandit, A. Controlling dispersion of axonal regeneration using a multichannel collagen nerve conduit. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 5789–5797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uschold, T.; Robinson, G.A.; Madison, R.D. Motor neuron regeneration accuracy: Balancing trophic influences between pathways and end-organs. Exp. Neurol. 2007, 205, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brushart, T.M.; Gerber, J.; Kessens, P.; Chen, Y.-G.; Royall, R.M. Contributions of Pathway and Neuron to Preferential Motor Reinnervation. J. Neurosci. 1998, 18, 8674–8681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.; O'Daly, A.; Vyas, A.; Rohde, C.; Brushart, T. Adult motor axons preferentially reinnervate predegenerated muscle nerve. Exp. Neurol. 2013, 249, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brushart, T.; Kebaish, F.; Wolinsky, R.; Skolasky, R.; Li, Z.; Barker, N. Sensory axons inhibit motor axon regeneration in vitro. Exp. Neurol. 2020, 323, 113073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maki, Y.; Yoshizu, T.; Tajima, T.; Narisawa, H. The Selectivity of Regenerating Motor and Sensory Axons. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 1996, 12, 547–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, Y.; Yoshizu, T.; Tsubokawa, N. Selective regeneration of motor and sensory axons in an experimental peripheral nerve model without endorgans. Scand. J. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Hand Surg. 2005, 39, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Q.; Zhang, F.; Cheng, W.; Gao, X.; Ding, Z.; Zhang, X.; Lu, Q.; Kaplan, D.L. Nerve Guidance Conduits with Hierarchical Anisotropic Architecture for Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Adv. Heal. Mater. 2021, 10, e2100427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valero-Cabré, A.; Navarro, X. Functional Impact of Axonal Misdirection after Peripheral Nerve Injuries followed by Graft or Tube Repair. J. Neurotrauma 2002, 19, 1475–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.I.; A Gurjar, A.; Talukder, M.A.H.; Rodenhouse, A.; Manto, K.; O’brien, M.; Karuman, Z.; Govindappa, P.K.; Elfar, J.C. Purposeful Misalignment of Severed Nerve Stumps in a Standardized Transection Model Reveals Persistent Functional Deficit With Aberrant Neurofilament Distribution. Mil. Med. 2021, 186, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alant, J.D.d.V.; Senjaya, F.; Ivanovic, A.; Forden, J.; Shakhbazau, A.; Midha, R. The Impact of Motor Axon Misdirection and Attrition on Behavioral Deficit Following Experimental Nerve Injuries. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e82546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brushart, T. Motor axons preferentially reinnervate motor pathways. J. Neurosci. 1993, 13, 2730–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madison, R.D.; Robinson, G.A.; Chadaram, S.R. The specificity of motor neurone regeneration (preferential reinnervation). Acta Physiol. 2007, 189, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hizay, A.; Ozsoy, U.; Demirel, B.M.; Ozsoy, O.; Angelova, S.K.; Ankerne, J.; Sarikcioglu, S.B.; Dunlop, S.A.; Angelov, D.N.; Sarikcioglu, L. Use of a Y-Tube Conduit After Facial Nerve Injury Reduces Collateral Axonal Branching at the Lesion Site But Neither Reduces Polyinnervation of Motor Endplates Nor Improves Functional Recovery. Neurosurgery 2012, 70, 1554–1556, discussion 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guntinas-Lichius, O.; Hundeshagen, G.; Paling, T.; Angelov, D.N. Impact of different types of facial nerve reconstruction on the recovery of motor function: an experimental study in adult rats. Neurosurgery 2007, 61, 1276–1283, discussion 1283–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ruiter, G.C.; Malessy, M.J.; Alaid, A.O.; Spinner, R.J.; Engelstad, J.K.; Sorenson, E.; Kaufman, K.; Dyck, P.J.; Windebank, A.J. Misdirection of regenerating motor axons after nerve injury and repair in the rat sciatic nerve model. Exp. Neurol. 2008, 211, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzel, C.; Rohde, C.; Brushart, T.M. Pathway sampling by regenerating peripheral axons. J. Comp. Neurol. 2005, 485, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajal SRy. Cajal's Degeneration and Regeneration of the Nervous System. DeFelipe, J., Jones, E.G., May, R.M., Eds.; Oxford University Press; 1991 22 Mar 2012.

- Chen, B.; Chen, Q.; Parkinson, D.B.; Dun, X.-P. Analysis of Schwann Cell Migration and Axon Regeneration Following Nerve Injury in the Sciatic Nerve Bridge. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, Q.; Parkinson, D.B.; Dun, X. Migrating Schwann cells direct axon regeneration within the peripheral nerve bridge. Glia 2020, 69, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried, K.; Govrin-Lippmann, R.; Devor, M. Close apposition among neighbouring axonal endings in a neuroma. J. Neurocytol. 1993, 22, 663–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.; Lanzarin, L.D.; A J, B. Clinical Evidence of Retrograde Axonal Growth in Chronic Brachial Plexus Injury. Cureus 2024, 16, e62424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero-Cabré, A.; Tsironis, K.; Skouras, E.; Navarro, X.; Neiss, W.F. Peripheral and Spinal Motor Reorganization after Nerve Injury and Repair. J. Neurotrauma 2004, 21, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Rassekh, N.; O'Daly, A.; Kebaisch, F.; Wolinsky, R.; Vyas, A.; Skolasky, R.; Hoke, A.; Brushart, T. Preferential motor reinnervation is modulated by both repair site and distal nerve environments. Exp. Neurol. 2024, 385, 115066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konschake, M.; Burger, F.; Zwierzina, M. Peripheral Nerve Anatomy Revisited: Modern Requirements for Neuroimaging and Microsurgery. Anat. Rec. 2019, 302, 1325–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spivey, E.C.; Khaing, Z.Z.; Shear, J.B.; Schmidt, C.E. The fundamental role of subcellular topography in peripheral nerve repair therapies. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 4264–4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulin, E.; Bowen, E.C.; Dogar, S.; Mukit, M.; Lebhar, M.S.; Galarza, L.I.; Edwards, S.R.; Walker, M.E. A Comprehensive Review of Topography and Axon Counts in Upper-Extremity Peripheral Nerves: A Guide for Neurotization. J. Hand Surg. Glob. Online 2024, 6, 784–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Martínez, I.; Badia, J.; Pascual-Font, A.; Rodríguez-Baeza, A.; Navarro, X. Fascicular Topography of the Human Median Nerve for Neuroprosthetic Surgery. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, W.; Yao, L.; Zeugolis, D.; Windebank, A.; Pandit, A. A biomaterials approach to peripheral nerve regeneration: bridging the peripheral nerve gap and enhancing functional recovery. J. R. Soc. Interface 2012, 9, 202–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Han, N.; Wang, T.; Xue, F.; Kou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yin, X.; Lu, L.; Tian, G.; Gong, X.; et al. Biodegradable Conduit Small Gap Tubulization for Peripheral Nerve Mutilation: A Substitute for Traditional Epineurial Neurorrhaphy. Int. J. Med Sci. 2013, 10, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Mi, D.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, J.; Wang, Y.; Tan, X.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Gu, X.; et al. Tubulation repair mitigates misdirection of regenerating motor axons across a sciatic nerve gap in rats. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, K.; Kubo, T.; Matsuda, K.; Hattori, R.; Fujiwara, T.; Yano, K.; Hosokawa, K. Effect of conduit repair on aberrant motor axon growth within the nerve graft in rats. Microsurgery 2007, 27, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker; Naghieh, S.; McInnes, A.D.; Schreyer, D.J.; Chen, X. Strategic Design and Fabrication of Nerve Guidance Conduits for Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Biotechnol. J. 2018, 13, e1700635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro-Resende, V.T.; Koenig, B.; Nichterwitz, S.; Oberhoffner, S.; Schlosshauer, B. Strategies for inducing the formation of bands of Büngner in peripheral nerve regeneration. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 5251–5259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taras, J.S.; Jacoby, S.M. Repair of Lacerated Peripheral Nerves With Nerve Conduits. Tech. Hand Up. Extremity Surg. 2008, 12, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, E.O.; Soucacos, P.N. Nerve repair: Experimental and clinical evaluation of biodegradable artificial nerve guides. Injury 2008, 39, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiono, V.; Tonda-Turo, C.; Ciardelli, G. Chapter 9: Artificial scaffolds for peripheral nerve reconstruction. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2009, 87, 173–198. [Google Scholar]

- Chiono, V.; Tonda-Turo, C. Trends in the design of nerve guidance channels in peripheral nerve tissue engineering. Prog. Neurobiol. 2015, 131, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Hu, W.; Deng, A.; Zhao, Q.; Lu, S.; Gu, X. Surgical repair of a 30 mm long human median nerve defect in the distal forearm by implantation of a chitosan-PGA nerve guidance conduit. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2011, 6, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, T.; Wang, Y.-L.; Zhang, F.-S.; Zhang, X.-M.; Zhang, Y.-C.; Jiang, H.-R.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, P.-X. The Porous Structure of Peripheral Nerve Guidance Conduits: Features, Fabrication, and Implications for Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Hu, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Gou, Z.; Cheng, H.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; You, S.; et al. A 3D-engineered porous conduit for peripheral nerve repair. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, T.; Scialla, S.; D’albore, M.; Cruz-Maya, I.; De Santis, R.; Guarino, V. An Easy-to-Handle Route for Bicomponent Porous Tubes Fabrication as Nerve Guide Conduits. Polymers 2024, 16, 2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.D.V.; Aleemardani, M.; Atkins, S.; Boissonade, F.M.; Claeyssens, F. Emulsion templated composites: Porous nerve guidance conduits for peripheral nerve regeneration. Mater. Des. 2024, 239, 112779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankavi, F.; Ibrahim, R.; Wang, H. Advances in Biomimetic Nerve Guidance Conduits for Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, C.R.; Oliveira, J.M.; Reis, R.L. Modern Trends for Peripheral Nerve Repair and Regeneration: Beyond the Hollow Nerve Guidance Conduit. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Suo, H.; Qian, J.; Yin, J.; Fu, J.; Huang, Y. Physical understanding of axonal growth patterns on grooved substrates: groove ridge crossing versus longitudinal alignment. Bio-Design Manuf. 2020, 3, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, K.; Ohnishi, K.; Kiyotani, T.; Sekine, T.; Ueda, H.; Nakamura, T.; Endo, K.; Shimizu, Y. Peripheral nerve regeneration across an 80-mm gap bridged by a polyglycolic acid (PGA)–collagen tube filled with laminin-coated collagen fibers: a histological and electrophysiological evaluation of regenerated nerves. Brain Res. 2000, 868, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Hu, W.; Cao, Y.; Yao, J.; Wu, J.; Gu, X. Dog sciatic nerve regeneration across a 30-mm defect bridged by a chitosan/PGA artificial nerve graft. Brain 2005, 128, 1897–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos, D.; Navarro, X.; Dubey, N.; Wendelschafer-Crabb, G.; Kennedy, W.R.; Tranquillo, R.T. Magnetically aligned collagen gel filling a collagen nerve guide improves peripheral nerve regeneration. Exp Neurol. 1999, 158, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonda-Turo, C.; Gentile, P.; Saracino, S.; Chiono, V.; Nandagiri, V.K.; Muzio, G.; Canuto, R.A.; Ciardelli, G. Comparative analysis of gelatin scaffolds crosslinked by genipin and silane coupling agent. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2011, 49, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novajra, G.; Tonda-Turo, C.; Vitale-Brovarone, C.; Ciardelli, G.; Geuna, S.; Raimondo, S. Novel systems for tailored neurotrophic factor release based on hydrogel and resorbable glass hollow fibers. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2013, 36, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Liu, J.; Yao, S.; Mao, H.; Peng, J.; Sun, X.; Cao, Z.; Yang, Y.; Xiao, B.; Wang, Y.; et al. Prompt peripheral nerve regeneration induced by a hierarchically aligned fibrin nanofiber hydrogel. Acta Biomater. 2017, 55, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochkind, S.; Nevo, Z. Recovery of Peripheral Nerve with Massive Loss Defect by Tissue Engineered Guiding Regenerative Gel. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Kankowski, S.; Ertekin, E.; Almog, M.; Nevo, Z.; Rochkind, S.; Haastert-Talini, K. Modified Hyaluronic Acid-Laminin-Hydrogel as Luminal Filler for Clinically Approved Hollow Nerve Guides in a Rat Critical Defect Size Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, W.; Lee, E.; Cho, W.; Kang, B.-J.; Yoo, H.S. Cell-directed assembly of luminal nanofibril fillers in nerve conduits for peripheral nerve repair. Biomaterials 2023, 301, 122209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigner, T.; Haynl, C.; Salehi, S.; O'Connor, A.; Scheibel, T. Nerve guidance conduit design based on self-rolling tubes. Mater. Today Bio 2020, 5, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Lu, S.-B.; Quan, Q.; Meng, H.-Y.; Chang, B.; Liu, G.-B.; Cheng, X.-Q.; Tang, H.; Wang, Y.; Peng, J. Aligned fibers enhance nerve guide conduits when bridging peripheral nerve defects focused on early repair stage. Neural Regen. Res. 2019, 14, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farzamfar, S.; Salehi, M.; Tavangar, S.M.; Verdi, J.; Mansouri, K.; Ai, A.; Malekshahi, Z.V.; Ai, J. A novel polycaprolactone/carbon nanofiber composite as a conductive neural guidance channel: an in vitro and in vivo study. Prog. Biomater. 2019, 8, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wei, H.; Cheng, H.; Cai, J.; Chen, X.; Xia, L.; Wang, H.; Chai, R. Scaffolds with anisotropic structure for neural tissue engineering. Eng. Regen. 2022, 3, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, T.; Chen, W.; Li, D.; Zheng, H.; El-Hamshary, H.; Al-Deyab, S.S.; Mo, X.; Yu, Y. Development of Nanofiber Sponges-Containing Nerve Guidance Conduit for Peripheral Nerve Regeneration in Vivo. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 26684–26696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Wei, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, L.; Kou, H.; Li, W.; Wang, H. Electrospun Nanofibrous Conduit Filled with a Collagen-Based Matrix (ColM) for Nerve Regeneration. Molecules 2023, 28, 7675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Jiang, L.; Du, J.; Xu, B.; Li, A.; Wang, W.; Zhao, S.; Li, X. Fluffy sponge-reinforced electrospun conduits with biomimetic structures for peripheral nerve repair. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2021, 230, 109482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Wei, H.; Cheng, H.; Qi, Y.; Gu, Y.; Ma, X.; Sun, J.; Ye, F.; Guo, F.; Cheng, C. Advances in nerve guidance conduits for peripheral nerve repair and regeneration. Am J Stem Cells 2023, 12, 112–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, W.; Li, H.; Yu, K.; Xie, C.; Wang, P.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, P.; Xiu, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, F.; et al. 3D printing of gelatin methacrylate-based nerve guidance conduits with multiple channels. Mater. Des. 2020, 192, 108757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawelec, K.; Koffler, J.; Shahriari, D.; Galvan, A.R.; Tuszynski, M.; Sakamoto, J. Microstructure and in vivo characterization of multi-channel nerve guidance scaffolds. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 13, 044104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Chang, J.; Liu, W.; Han, B. Multichannel nerve conduit based on chitosan derivates for peripheral nerve regeneration and Schwann cell survival. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 301, 120327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinis, T.; Elia, R.; Vidal, G.; Dermigny, Q.; Denoeud, C.; Kaplan, D.; Egles, C.; Marin, F. 3D multi-channel bi-functionalized silk electrospun conduits for peripheral nerve regeneration. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2015, 41, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, D.; Kim, D.; Park, S.J.; Choi, J.H.; Seo, Y.; Kim, D.-H.; Lee, S.-H.; Hyun, J.K.; Yoo, J.; Jung, Y.; et al. Micropattern-based nerve guidance conduit with hundreds of microchannels and stem cell recruitment for nerve regeneration. npj Regen. Med. 2022, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.N.; Lancaster, K.Z.; Zhen, G.; He, J.; Gupta, M.K.; Kong, Y.L.; Engel, E.A.; Krick, K.D.; Ju, A.; Meng, F.; et al. 3D Printed Anatomical Nerve Regeneration Pathways. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25, 6205–6217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Tringale, K.R.; Woller, S.A.; You, S.; Johnson, S.; Shen, H.; Schimelman, J.; Whitney, M.; Steinauer, J.; Xu, W.; et al. Rapid continuous 3D printing of customizable peripheral nerve guidance conduits. Mater. Today 2018, 21, 951–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Zhu, Q.-T.; Yao, Z.; Yan, L.-W.; Wang, T.; Qiu, S.; Lin, T.; He, F.-L.; Yuan, R.-H.; Liu, X.-L. A rapid micro-magnetic resonance imaging scanning for three-dimensional reconstruction of peripheral nerve fascicles. Neural Regen. Res. 2018, 13, 1953–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Yan, L.-W.; Qiu, S.; He, F.-L.; Gu, F.-B.; Liu, X.-L.; Qi, J.; Zhu, Q.-T. Customized Scaffold Design Based on Natural Peripheral Nerve Fascicle Characteristics for Biofabrication in Tissue Regeneration. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, P.S.; Lee, T.Y.; Kneiber, D.; Dy, C.J.; Ward, P.M.; Kazarian, G.; Apostolakos, J.; Brogan, D.M. Design and In Vivo Testing of an Anatomic 3D-Printed Peripheral Nerve Conduit in a Rat Sciatic Nerve Model. HSS J. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, C.E.; Kan, C.F.K.; Stewart, B.R.; Sanicola, H.W.; Jung, J.P.; Sulaiman, O.A.R.; Wang, D. Machine intelligence for nerve conduit design and production. J. Biol. Eng. 2020, 14, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkata Krishna, D.; Ravi Sankar, M. Engineered approach coupled with machine learning in biofabrication of patient-specific nerve guide conduits - Review. Bioprinting 2023, 30, e00264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).