Egyptian Archaeological Heritage Legislation in Perspective

Egypt is universally perceived as the primary archaeological region par excellence. One must agree with Sandes who stated: “If we call to mind the fact that Egypt is no more than a narrow valley through which passes the earthly flow of the Nile and that its productive soil, containing a certain variety of products, possesses per se for mankind no interest save that yielded from the top of the pyramids; when we again ponder over the untold value of many other regions, and range all countries, with their divergent climates, agricultural, archaeological or historical riches, and try to analyze the causes of the unbounded, ever undiminished, attraction exercised by this narrow strip, so redolent of wonders, on the collective intellect of mankind, we may well fail to realize the peculiar potency of this attraction (Sandes, 2015).

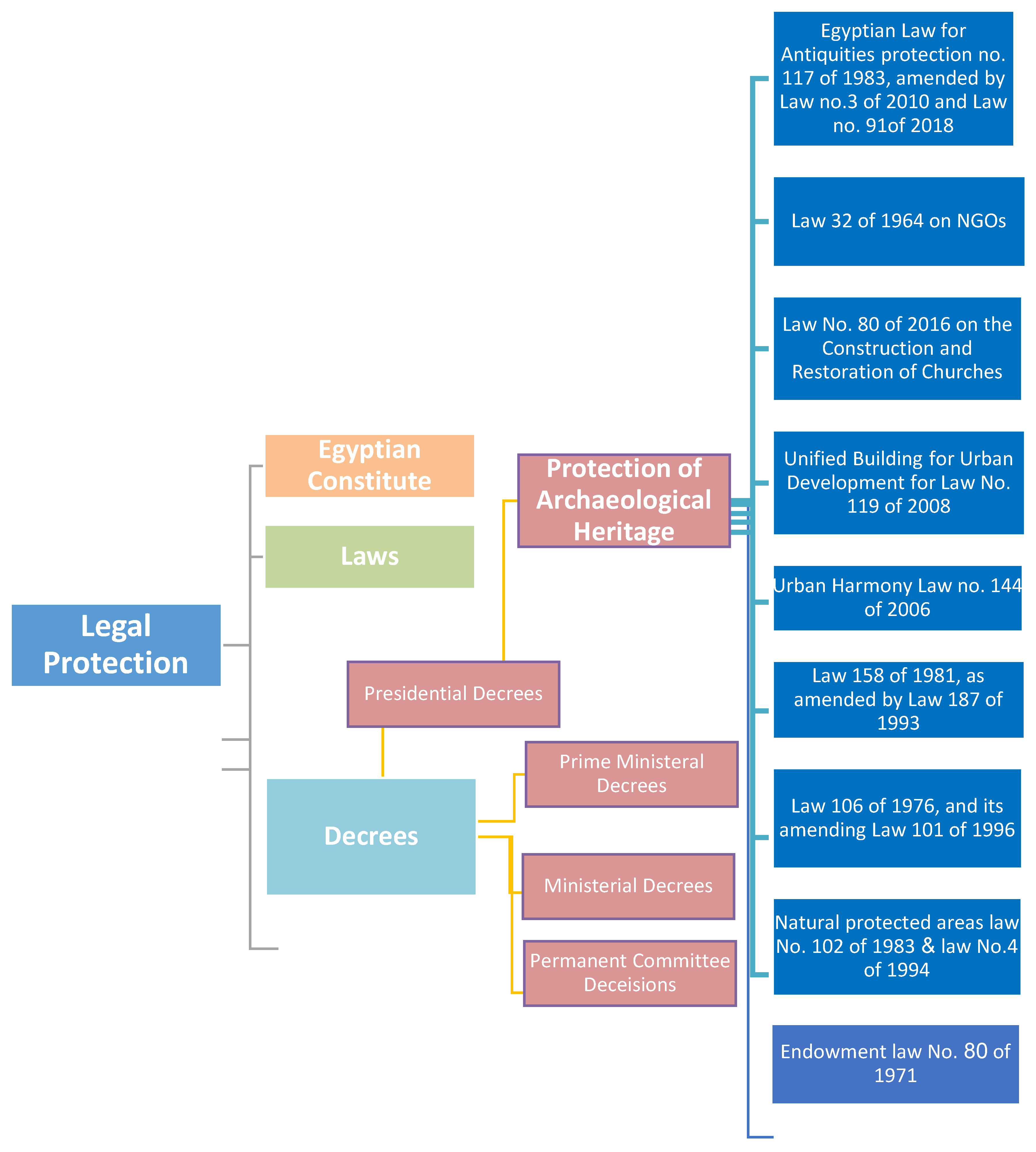

The legislative texts issued by the executive authorities in Egypt since the middle of the 19th century concerning the protection of its archaeological heritage reflect the evolution of Egypt’s perception of its more than seven-thousand-year-old cultural heritage, starting with the issuance of The Antiquities’ Protection Law in 1835, which was concerned with protecting the Egyptian monuments exposed to the excavations of archaeological missions and allowing the least possible intervention in this process, to the latest modifications of Law No. 91 of 2018, which have taken into account the recent archaeological discoveries in the areas designated for urban expansion, as well as the necessary harmonization with the requirements of community development, which sometimes contradicted the urgency to remove the archaeological site or the antiquities from the site.

The analytical method of the texts of the relevant laws has been adopted in writing the research as it is based on extrapolation and comparison, through reviewing the legal texts that the legislator mentioned in this regard, whether they are at the heart of the Constitution of the Arab Republic of Egypt for the year 2014, contained in the laws that relate to antiquities and heritage trying to analyze it and discussing it to demonstrate its sufficiency to provide the necessary protection and management tools for this important archaeological heritage.

According to the Egyptian Constitution, article no. 49 and 50, the Egyptian government is obligated to protect and conserve cultural heritage. As for the Egyptian archaeological sites, the Ministry of Antiquities is responsible for the protection of the archaeological sites according to the Egyptian Law of Antiquities Protection No. 117 of 1983 amended by Law No. 3 of 2010, and Law No. 91 of 2018. The principal law defines the rule of archaeological site management, including excavation, discovery, restoration, maintenance, and optimum showing placement. This covers both fixed monuments, presented and shown in their place of discovery; e.g., temples, Tombs, mosques, churches, synagogues, palaces, cemeteries, etc., and movable antiquities (Shaikhon, A. 2017).

To appreciate the current position that historic heritage assumes in Egypt and other comparable Eastern societies, it is important to understand that heritage protection and management largely occur within a legislative framework established by the government.

Peter James suggests that the role legislation plays in this process is one that ‘provides penalties for use against people if they follow a particular course of action and that the ‘powers to impose penalties and the enabling powers which allow governments to disburse monies for conservation purposes are the only real roles of the law in the conservation process’ (Peter James, 1995).

However, overlooks a further key role that legislation assumes – the creation of the legal context within which administrative practice is influenced and informed. This is not to say that legislation is always clear in its purpose or easy to interpret. As Michael Pearson and Sharon Sullivan observe, the extent to which heritage-related laws, for instance, are effective is largely dependent on the quality and comprehensiveness of the legislation, the zeal and wisdom with which it is implemented, and the adequacy of the administrative and technical systems and financial resources supporting it’ (Pearson and Sullivan, 1995).

Any legislation that has at its core an objective to protect places of identified heritage value is, on balance, likely to impinge on the rights of private owners. Given the general reluctance of many governments to introduce legislation that interferes with such rights, a precautionary approach is often applied by legislators.

To begin to understand and appreciate how legislation affects or influences how we protect and manage our historic heritage it is important, therefore, to recognize that it is inevitably political and, as a corollary, subject to the excesses and vagaries associated with political processes operating at the national,

Regional and local levels. Balanced against this, though, is the need to appreciate that heritage legislation, in whatever guise, is still an expression of the community’s wish for [heritage place] management, and if properly written or used, is a useful tool’. (Pearson and Sullivan, p37.) With these sentiments in mind, this context will focus on some of the principal statutes affecting historic heritage protection and management in Egypt.

History of Egyptian Heritage Law and Legislations

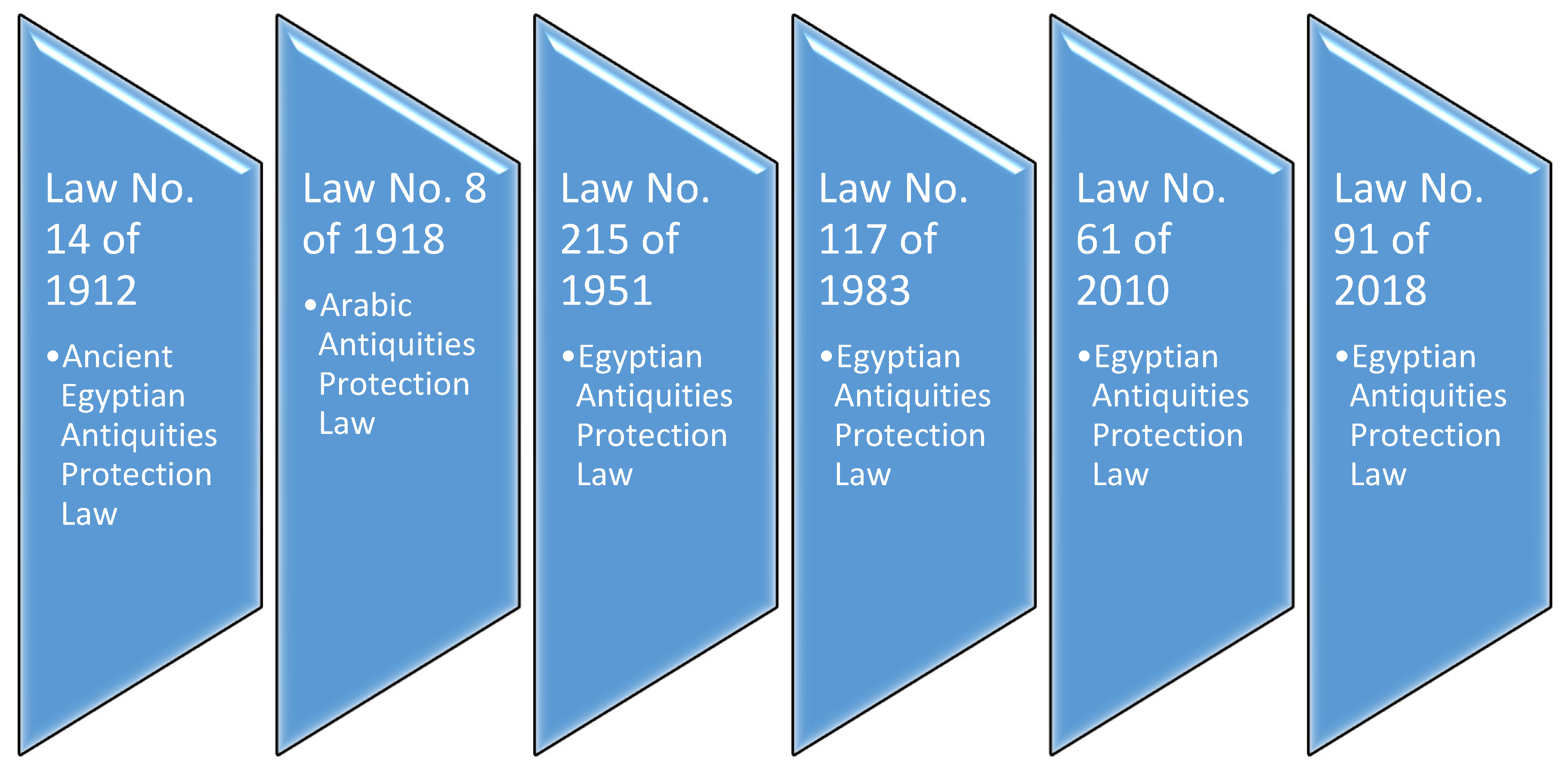

In the beginning, I would like to review the historical development of laws and legislation related to the protection of antiquities and heritage in Egypt, from the issuance of the first decree related to the protection of Egyptian heritage until now.

While monument protection laws were applied in European countries towards the middle of the nineteenth century, the foreign consuls stood against the Egyptian protection laws, which were being legislated at around the same time. Al-Tahtawi who lived in Europe between 1826 and 1831 worked hard to protect the Egyptian Antiquities. He convinced Mohamed Ali to issue a decree to control the plundering of antiquities. On August 15th, 1835, the decree specified that antiquities were to be sent to al-Tahtawy, director of the School of Languages in El Azbekiyeh, Cairo. The decree also came to control the activities of French, British, and American consuls in Egyptian archaeological sites. However, French Consul General Jean-François Mimaut and American Consul George R. Gliddon dismissed the decree and continued with their collecting policy (Reid 2002: 55).

In 1858 Said Pasha, conferred Auguste Mariette the role of Conservator of Egyptian Monuments this role was the beginning of heritage management in Egypt and his first act was to create the Museum of Cairo (Shaikhon, 2017). He was supported by Ismail Pasha in these early years of forming an Egyptian Antiquities Service by providing laborers for excavation and giving him the warehouses that would go on to become the Museum of Cairo (Greener 1966: 183). He used his influence as a close friend of Ismail Pasha and head of the Egyptian Antiquities Service to stop many other European Egyptologists from excavating in Egypt except the French (Wortham 1971: 83); In 1881 Khedive Tawfiq Pasha was concerned over the state of preservation over Islamic art and architecture formed the committee, it consisted of a mixture of Egyptian and western connoisseurs or Oriental art. However, by 1890 westerners dominated the board (Reid 2002: 226). The committee focused almost entirely on preserving mosques and mausoleums (Reid 2002: 228).

In 1912, Law No. 14 was issued during the reign of Khedive “Abbas Helmy ΙΙ” on antiquities and was allowed to trade antiques and export, where the second paragraph of Article IV stipulates that the right of individuals trafficking in antiquities if they owned Antiquities. The state granted a license to Antiquities dealer’s law allows inspectors to pass through them regularly, but wonder what it is to put laws on the export of monuments. As a result, flourished of Antiquities trade between 1912 and 1951, and the back of many licensed and unlicensed shops selling Antiquities but it came out that the street vendors who were selling Antiquities, provided the statues at the price of not more than five pounds, and after a vogue that trade, intervened State to subscribe to this crime has been allocated hall No.56 on the second floor of the Egyptian Museum liberalization be months showroom for the sale of Egyptian antiquities, (Shaikhon, 2017).

In 1951 Law No. 215 was issued, which Article 22 thereof to allow the trade in antiquities and sold without distinction, and given the right to museums to sell what dispensed with it without clear criteria or any requirements, where the authors of those laws could see appropriate legislation and European laws, but on the contrary, European laws at the time was to allow trade in antiquities in a narrow range and often was allowed to trade in Pharaonic, Islamic and Coptic monuments.

After 1952, the revolution was the first Egyptian law declared. In 1953, President Gamal Abdel Nasser issued Law No. 529 organized the work of Antiquities Services in a way aimed at protecting Egyptian Antiquities. Law no. 192 in 1955, and law no. 27 in 1970 optimized the 1953 law for organizing the Antiquities Authority. In 1971, President Anwar Al-Sadat issued decree No. 2828 which “established the Egyptian Antiquities Authority as the single authority for archaeological exploration, excavation, and preservation. The Egyptian Antiquities Authority was intended to define methods and ways of handling, utilizing, preserving, and protecting antiquities and archaeological sites.”(Radwan, 2009).

On 03/29/1979, the Council of Egyptian Antiquities Authority Minister of Culture issued a decision from one article to stop granting licenses to individuals for trafficking in antiquities, which were, sourced from outside the country; however, by 1983 many important Egyptian antiquities had already been transferred to foreign countries. Then Law No. 117 of 1983 was issued which prohibited the Antiquities trade both internally and decided to have a penalty of imprisonment and a fine for violation of its provisions. The Egyptian Government declared law No. 117 of 1983 that came to define how to manage the antiquities in museums and archaeological sites, including exploration, excavation, discovery, restoration, maintenance, and optimum rehabilitation for Presentation. (Radwan, 2009). This covers both fixed monuments which are presented and shown in their place of discovery; e.g., temples, mosques, palaces etc.; and movable antiquities; e.g., pans and tools made of clay, metal, wood, etc. which are shown inside museums.

In 1991, law no. 12 was issued to amend articles of law no. 117 of 1983. Presidential decree No. 82 was issued to “nullify the Egyptian Antiquities Authority and replace it with the Supreme Council of Antiquities.”(Radwan,2009). The government gave the Egyptian Antiquities Authority or the Supreme Council of Antiquities under the auspice of the Ministry of Culture, high authority so that its personnel can manage and protect the antiquities.

Law No. 117 of 1983 was amended by Law No.3 and 61 in 2010 (Ministry of Culture, Published in the official gazette on February 2010). On the 16th of, May 2012 the Supreme Council of Armed Forces decree number (283) was to exchange the Ministry of Culture and Minister of Culture with the Ministry of Antiquities, and the Minister of Antiquities. From this date 16th, May 2012 the Ministry of Antiquities will be independent (shaikhon, 2017).

The law governing the protection of Archaeological heritage is Law No. 117 of 1983, amended by Law No.3 and 61 in 2010. which covers the concept of protected property that must be preserved in Articles 1 and 2; the system of ownership in Articles 6, 8, 9, 16, and 35; and also, the extension of protection and conservation operations as follows: Registration and documentation in Articles 2, 8, 9, 16, and 35; Rights and duties of the owner of the historic properties as well as people who have the authority to control such properties in Articles 2, 9, 10, 13, 26, 28, and 30; Organize ways of dealing with monuments and antiquities in paragraphs 7 and 8; Export rules in paragraphs 9 and 13; Accidental discoveries and discoveries made by chance in Article 24; Archaeological excavations in Articles 5, 31, 32, and 37; Regulations of punishments in Articles 41 and 47; and Authorities responsible for conservation operations in Article No.5.

Following are the articles of law no. 117 of 1983 amended by Law No.3 and 61 in 2010, the principal law governing the management of antiquities, with several articles amended to give it wider jurisdiction and authority:

Antiquities are defined in Article One as all movable and immovable objects, that are produced by various civilizations or made by the arts, science, or religions from the prehistoric era and throughout the successive eras until before one hundred years whenever it has value, importance whether on historical or antiques level as a manifestation of various civilizations that were founded on Egypt or was related to its history, also the remains and the beings lived with it”.

All antiquities, either known or concealed, ultimately belong to the State and are required to be registered on an official inventory. Modification, displacement, or demolition of classified antiquities is prohibited. The State maintains the right to expropriate any antiquity, or land containing antiquities. The Discovery of antiquities should be reported immediately to the nearest administrative official; the State may acquire any such antiquity for national collections and the displaying of such antiquity.

A permit is legally required for all field research, the conditions of which are set at the time of granting the permit. All foreign nationals are required to submit a security declaration form to the Ministry of Antiquities Security Office, via the SCA.

Exportation of cultural property (including environmental and biological samples) is strictly prohibited without a permit, which must be obtained 30 days before the intended date of export. The movement of antiquities within the country must be approved 15 days before their transportation.

The Supreme Council of Antiquities under the auspice of the Ministry of Antiquities is responsible for the restoration and preservation of Egypt’s cultural heritage.

Article 5 of Law 117 of 1983 stipulates that the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA) has sole authority to supervise all matters related to antiquities whether in museums, warehouses, archaeological and historic sites/locations; even when such antiquities are discovered accidentally. The SCA is responsible for exploring antiquities above the ground and excavating antiquities buried underground and in territorial waters. The Chairperson of the SCA, after securing approval of the permanent committee concerned, may authorize/permit specialized patriotic/national and/or expatriate scientific expeditions to explore and excavate antiquities in certain locations for definite periods. Such permits are private permits that may not be assigned to others. Permits may only be given upon ensuring sufficient scientific, technical, financial, and archaeological prequalification of the entity requesting the permit.

On the date this law comes into effect, all trading in antiquities is banned the law gives the SCA the priority to retrieve the antiquities in return for just compensation. The SCA has the right to acquire or retrieve antiquities in the possession of traders or holders in return for just compensation. The SCA may exchange some of the movable antiquities with countries, museums, Arabic, or foreign scientific institutions upon a presidential decree issued based on a recommendation from the Minister of Antiquities.

Upon a presidential decree – in the achievement of public interest – some antiquities may be placed outside Egypt. This doesn’t include antiquities defined by the SCA as being unique or vulnerable. The law identified that the Antiquities are registered with a decree from the minister of culture based on a recommendation from the SCA’s board of directors. The registration shall be published in the Official Gazette.

Without prejudice to the penalties stipulated/stated in this law 117 of 1983 or other laws, the Chairperson of the SCA based on a decision of the standing antiquities committee, without the need to resort to the judiciary, may order the removal of any encroachment on archaeological sites using administrative process. The antiquities police shall undertake the implementation of the order. The violator shall be responsible for restoring the antiquity to its previous condition. The SCA may restore the antiquity to its previous condition at the expense of the violator.

Construction licenses may not be granted in archaeological sites and lands. Others may not construct any buildings, or graves, dig canals, pave roads, or cultivate over archaeological sites, or surrounding public utility terrain.

Authorized entities with the approval of the SCA may license construction in areas adjacent to archaeological sites within populated (inhabited) areas. The competent authority shall guarantee the license with the conditions that the SCA deems appropriate: the new building should not overshadow the antiquity, giving the antiquity-appropriate campus, while taking into consideration the historical and archaeological surroundings and the transportation leading to it.

With the continuous development of archaeological sites and the intensity of excavation activities, Egypt continues to develop a law that guarantees the protection of Egypt’s archaeological heritage. Law No. 117 of 1983 was amended by Law No.91 in 2018 (Ministry of Antiquities, Published in the official gazette in February 2018) to Reset the wording of some articles whose practical implementation has resulted in legal and realistic problems.

Create two independent bodies for the Grand Egyptian Museum and the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization, and give them the flexibility to upgrade their level and give them multiple powers so that each of them can play a role in raising archaeological awareness and revitalizing the tourism sector according to the latest scientific and international standards.

Granting authority to the Supreme Council of Antiquities to remove any irregularities in archeological sites and sites.

Regulating the presence of vehicles, vendors, and animals with specific conditions and controls to preserve the cultural appearance of Egypt.

Removing the confusion between the concept of prohibiting the impact and the approved cosmetic line of the effect, and setting a clear definition for each of them based on the approval of the specialized permanent committee.

Granting the Ministry concerned with antiquities affairs the extension of its jurisdiction over museums and antiquities stores located in some ministries, government agencies, public bodies, and universities, and that it should have the exclusive right to supervise it by ensuring that it is registered, insured, and maintained at the expense of the aforementioned entities (the bodies that exploit it.

The Antiquities Protection Law means everything that is archaeological, in light of the definition of Antiquities that the legislator has mentioned in the current law in the first and second articles. The legislator has ensured his protection, maintenance, and restoration on this basis, which is the matter that replaces the term archaeological buildings with the term historical buildings wherever they appear in the law.

Confronting cases of encroachment on archaeological sites and lands that have increased significantly in recent times, and the presence of extreme difficulty in facing this negative phenomenon, requires amendment of Article 17 to include rapid measures to ensure the protection of those archaeological sites and lands, and the most important of these measures is to stop the infringement activities in the cradle with a decision It is issued by the Minister, upon the issuance of a record of the violation, until the decision of removal is issued after the approval of the permanent committee, in view of the procedures it takes during which the transgressor has reached his stage of difficulty with removal, based on the security study prepared by the police in this regard, as required by the text On E. Obliging all the concerned authorities not to grant accompanying or other licenses for the actions resulting from the infringement, without prejudice to the penalties stipulated in the law or any other law, to thwart any infringement on our cultural heritage.

The draft law added an article about military museums at the level of the Republic, entrusted with the management of military museums, which assumed all responsibilities and functions of supervision, administration, and insurance concerning military museums.

The current legislation in Article 30 obligated both the Ministry of Endowments, the Egyptian Endowments Authority and the Coptic Endowments Authority, the Egyptian Church with the expenses of restoration and maintenance of the registered historical properties belonging to them, because of their religious value as well as what they constitute a true reflection of civilization, and the consolidation of the principle of equality between equal legal centers according to the text According to the constitution, the draft law included the assumption by the churches of various denominations of their churches for the maintenance and restoration of archaeological buildings belonging to them, provided that the competent ministry in antiquities affairs in cases of necessity and grave danger that require rapid intervention to carry out maintenance and restoration work for some of the Real Estate archaeological belonging to any of the entities referred to above and refer the expenses on the owner.

The current legislation included in the last paragraph of Article 32 thereof, the determination of the right for the entity authorized to work in the archaeological sites to study the effects discovered, drawn, and photographed, and it was rather that these works also include restoration because of its importance and benefit accruing to The impact and the benefit of the young archaeologists accompanying the missions from their experience in this field. This article must be amended by adding the restoration to the works referred to.

Article 36 of the current legislation decided to apply to the archeological models produced by the ministry and pictures of artifacts and archaeological sites owned by the ministry. All intellectual property rights. Law No.82 of 2002 mandated the determination of the competent authorities and the application of its provisions without including the Ministry of Antiquities for their non-existence at the time of issuing this legislation, The draft law remembers it in Article 36 by stipulating that the minister responsible for antiquities affairs is responsible for applying the provisions of the intellectual property law concerning antiquities affairs.

The current legislation added a very important step towards achieving the ministry’s goals by establishing production units of a special nature, which opens the way for the establishment of holding or contributing companies to serve those goals, whose purpose is to manage services in archaeological sites and museums, and not to manage sites and museums that take over the ministry without Others manage it.

Since the general rules have been established provided that fees are not estimated except by law, and to meet the Ministry’s financial obligations, the matter requires increasing the fees for visiting museums, archaeological sites, and areas for Egyptians and foreigners, by not exceeding an amount of two thousand pounds, instead of a thousand pounds for Egyptians, and ten thousand pounds instead of Five thousand pounds or it’s equivalent in foreign currencies for foreigners, and regarding the collection of visiting fees, the board of directors estimates the fees for opening areas, archaeological sites, and museums in times other than official working hours, not exceeding five million pounds. The project also created a provision that the opinion of the Ministry of Tourism should be taken in the event of issuing villages the increase in fees to activate the integration between the ministries concerned so that the increase does not affect the flows of tourist groups in the country.

In March 2020, President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi issued Law No. 20 of 2020 amending some provisions of the Antiquities Protection Law. The amendments stipulated that two new articles numbered (42 bis 2, and 45 bis 1) be added to the Antiquities Protection Law No. 117 of 1983 issued a new punishment for climbers of monuments, or access to an archaeological site or museum without permission and The penalty shall be doubled if the violation of public morals or insulting the country. It is clear that Egyptian authorities trying to update their legislation and laws to ensure more protection for their cultural heritage sites. In recent years, several important modifications to the current laws were made to preserve heritage properties.

Figure 2.

Legal Development through the Century Source: © Ahmed Shaikhon. Other Laws and Regulations Related to the Archaeological Heritage Management.

Figure 2.

Legal Development through the Century Source: © Ahmed Shaikhon. Other Laws and Regulations Related to the Archaeological Heritage Management.

Table 1.

Legal regulations and their relation to the archaeological Heritage sites.

Table 1.

Legal regulations and their relation to the archaeological Heritage sites.

| Legal Framework |

Relation to the Archaeological Heritage |

| Egyptian Constitution (Issued in 2014) |

The Egyptian constitution is the main legal frame for the Egyptian state. According to article no. 49 and 50 relative to cultural heritage management, the Egyptian government has to protect and conserve cultural heritage |

| Egyptian Law of Antiquities Protection no. 117 of 1983 amended by Law no.3 of 2010 and Law no. 91 of 2018 |

This law is the main legal framework for Cultural Heritage Management in Egypt. It defines the main responsibilities of the Ministry of Antiquities and its relationship with the other responsible governmental parties, its administrative main framework, and the decision-making process regarding the management, conservation, and maintenance projects. |

| Urban Harmony Law no. 144 of 2006 |

This law addresses the conservation of architectural heritage. This law is concerned with protecting buildings of distinctive value and buildings of high heritage value. The law includes “Buildings and structures of distinctive architectural order or related to national history or a historic personality or those representing a historic era or considered a touristic destination”, those are protected against demolition or modification. |

| Law No. 80 of 2016 on the Construction and Restoration of Churches. |

This law regulates the construction and restoration of churches in local administrations, tourist and industrial areas, and new urban and residential communities as determined by a decision of the Ministry of Housing. |

Unified Building for Urban Development

Law No. 119 of 2008 (Articles 32 - 60 - 102 - 104 - 107) |

This law deals with urban planning (determining the conditions of land use, planning, and design of roads, parks, and green areas) and defines the role of the General Authority for Urban Planning (GOPP) in the organization of rehabilitation works in coordination with various entities. The law also stipulates the importance of preserving historical sites and developing areas of special value and specifies the requirements for new building permits according to the building regulations of each region. |

| Natural Reserves Law No. 102 of 1983 |

This law shall protect the Nature Reserves of Egypt. Article 1 stipulates that a nature reserve is defined as: “Any area of land or coastal or inland waters characterized by flora, fauna and natural features of cultural, scientific, touristic or aesthetic values.” |

The laws particularly outfitted towards protecting Egypt’s built heritage (Laws No. 117/1983, No. 178/1961, and No. 144/2006) have also led to the endangerment and sometimes demolition of historic houses due to ambiguous legal jargon. Antiquities, in general, are protected by Law No. 117 of 1983, and buildings of architectural value and historical importance are protected by Law No. 178 of 1961. Law No. 144 of 2006 regulates demolition licenses and is concerned with protecting buildings of recognized architectural value. According to Law No. 117, buildings are classified as ‘‘historic” if they can be attributed to one of Egypt’s essential cultural influences (Greek, Roman, Christian, Islamic, or Ancient Egyptian). Law No. 144, by contrast, leaves the ‘‘heritage” classification much more ambiguous, and there is no ministry or state institution that is explicitly responsible for the official classification or protection of heritage buildings. Because of these loopholes, property owners who aim to demolish a heritage building need only to request consent from a heritage committee consisting of specialists and representatives from the governorate and the Ministry of Housing, Utilities, and Urban Communities. These rulings essentially remove all legal barriers that protect these buildings from demolition.

Recently, the international debate in the field of Archaeological Resource Management has focused on how sites are used for, and by, the general public. In Egypt, several management plans for nationally designated archaeological sites have recently been undertaken. A revision of the Antiquities Protection Act 1983 in 2018 without mention of the management of archaeological sites while the South Korean Cultural Heritage Protection Act 1962 in 2012 includes the ‘Formulation of a Master Plan for Cultural Heritage’ in Article 6: ‘the Administrator of the Cultural Heritage Administration shall formulate a comprehensive master plan addressing the following matters (hereinafter referred to as “master plan for cultural heritage”) every five years, following consultations with the competent Mayor/Do Governor for the preservation, management, and utilization of cultural heritage (Radwan, 2009).

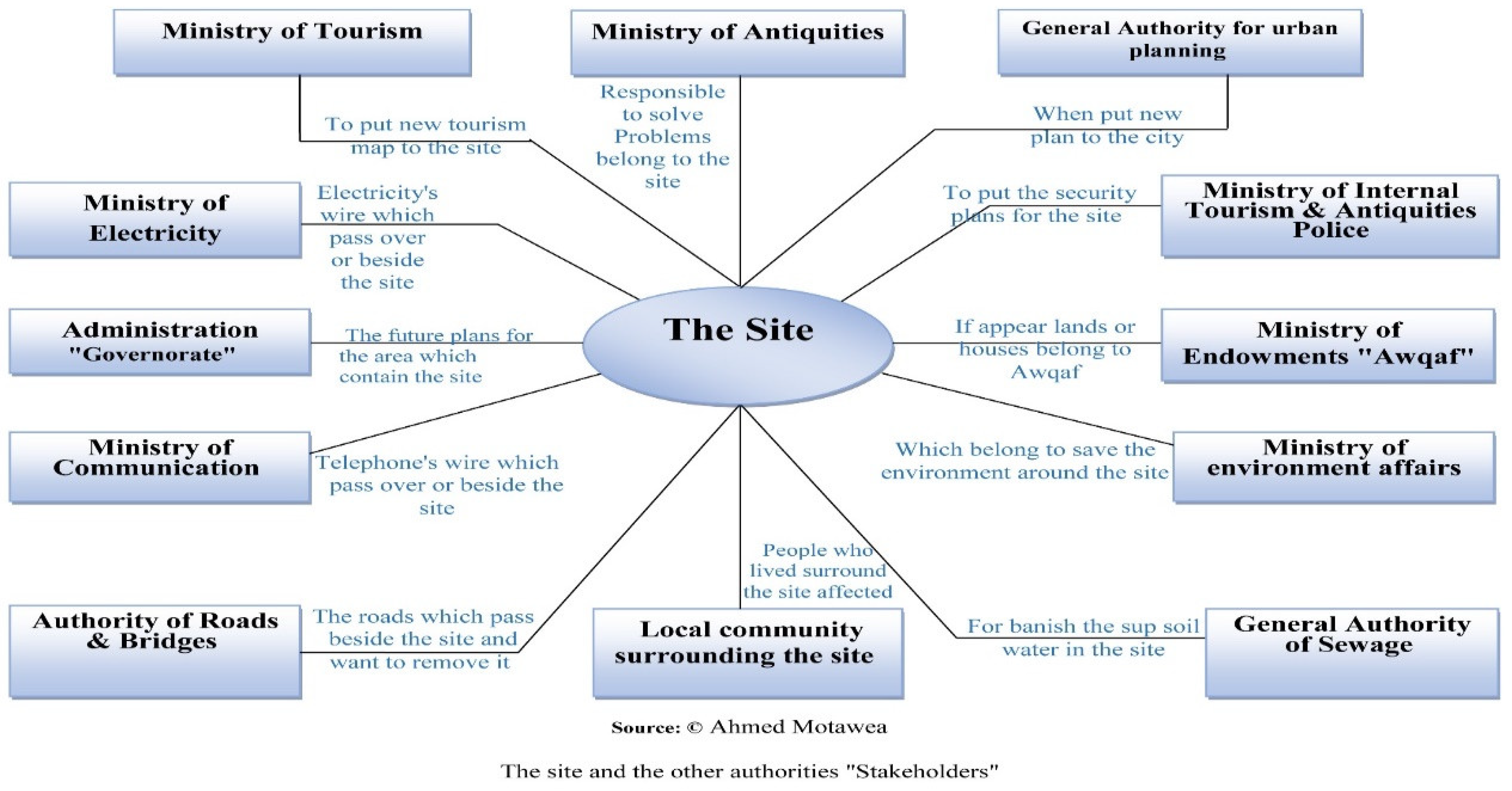

The above-mentioned laws and regulations lack integration and coordination, and while only Law 117 of 1983 touches on buildings and sites that are part of the Cultural Heritage of Egypt, the other laws do have a serious primary potential impact on the buildings and sites. The major gap existing is that neither the laws nor the bodies assigned their implementation and execution have any direct or indirect, clear or inferred role or responsibilities in the present framework of Culture Heritage Management.

The Unified Building Law No. 119 of 2008 granted the competent authority in the localities to issue permits for demolition, restoration, and construction within the city’s boundaries, and the Antiquities Protection Law No. 117 of 1983 granted the Supreme Council of Antiquities alone the authority to carry out the necessary maintenance and restoration work for all monuments, archaeological areas, and historical buildings. By studying and reviewing the laws, regulations, and ministerial decisions related to the archaeological and historical sites, it became clear that there is a multiplicity of the concerned parties, a duality of competence, and a conflict of authority, which resulted in impeding any development and preservation of its world heritage.

Stakeholders are public and private bodies and individuals who are in some way affected by the outcome of the management process. To achieve public support for the Management Plan, initiatives, and acceptance of its outputs, the participation of stakeholders is essential. Information sharing, consultation through public hearings, and involvement in community-based projects are means to ensure stakeholder participation. Furthermore, the heritage conservation process and laws have not been made transparent or explained to the involved parties. Besides, the participation of stakeholders and the community is not a legal requirement in the Egyptian political system connected with the issuing of laws. Consequently, the engagement of owners in the decision-making process regarding heritage conservation was not considered.

Figure 3.

diagram shows the site and all authorities related to the management plan. Source: © Ahmed Shaikhon.

Figure 3.

diagram shows the site and all authorities related to the management plan. Source: © Ahmed Shaikhon.

Local communities are still not widely involved in heritage conservation endeavors. Involvement is crucial because there are so many stakeholders in heritage beyond the practitioners, governments, researchers, and developers. Most heritage legal instruments have no role for these communities which makes them spectators in the study and protection of their heritage. The tendency has been for scientists to carry out their work without involving local people or by merely employing them as laborers.

The need for a National Strategy requires that all actions about the identification, processing recommendation, conservation, preservation, and management of Heritage buildings or sites be set in a single well-coordinated, and integrated legal framework. This framework must be transparent to all national, local as well as international bodies, and be specific as to the responsible bodies and entities, as well as the accountabilities for each aspect of the strategy, and its implementation.