1. Introduction

As the demand for fossil natural resources increases, so do the requirements for environmental protection. One of the urgent issues in processing hydrogen sulfide-containing oils is increasing the operation efficiency and environmental safety of oilfield systems. In modern conditions of the market economy, there is a tendency to use small-sized automated installations in a block-aggregate design, which is due to the desire to save energy resources. The development of new energy- and resource-saving technologies is becoming an increasingly relevant topic in the field of environmental protection from harmful industrial gas emissions. Sulfur-containing compounds must be removed before use on power equipment due to their corrosive activity and the possibility of forming sulfide deposits on heating surfaces. Therefore, the use of adsorption technology, the development and use of sorbents from natural and waste materials for the purification of fuel gases and gas emissions from oil refining will contribute to solving the problems of rational use of natural resources and energy conservation in the oil refining sector.

2. Literature Review

The use of industrial waste to carry out the adsorption process has proven itself as one of the viable technologies for the purification of gaseous fuels and gaseous petroleum products from sulfur compounds [

1]. Adsorbents from industrial waste are cheaper than traditionally used adsorbents, such as carbon structures, zeolites, metal oxides, membranes, etc. Some studies are devoted to the development of inexpensive adsorbents using various agro-industrial and municipal wastes [

2,

3,

4]. Low-cost adsorbents help to protect the environment by contributing to the reduction of waste disposal costs.

In studies [

2,

5] it is shown that despite the developed production of industrial adsorbents, there is a growing trend towards the development of low-cost adsorbents from waste or natural materials. Adsorbents obtained from free waste can have an overall positive impact on the country’s economy.

Agricultural Waste as Low-Cost Adsorbents

Agricultural materials have potential sorption capacity for various pollutants due to the cellulose content. The main components of agricultural waste include hemicellulose, lignin, lipids, proteins, simple sugars, water, carbohydrates and starch containing various functional groups. Agricultural waste is a potential raw material for the production of adsorbents due to its unique chemical composition and has the advantages of being economical and environmentally friendly, accessible, renewable and low cost. Agricultural waste is a rich source for activated carbon production. It has low ash content and acceptable strength [

6], so recycling agricultural waste into low-cost adsorbents is a promising alternative to solve environmental problems.

Over the past decades, various agricultural wastes have been investigated as low-cost adsorbents. Over the past decades, various agricultural wastes have been investigated as low-cost adsorbents. Researchers have considered wastes such as shells and/or pits of fruits such as nuts [

7], peanuts [

8], olives [

9], almonds [

10], apricots [

11] and cherries [

12], wastes generated during the production of cereals such as rice [

13], corn [

14], as well as sugarcane bagasse [

15] and coconut pulp [

16]. These agricultural wastes were used in their natural form or after some physical or chemical modification.

It should be noted that the developed adsorbents based on agricultural waste show excellent results and are comparable to commercial adsorbents in terms of the adsorption capacity (sulfur adsorption capacity). Thus, when using rice husks processed by pyrolysis at 400 °C, the sulfur adsorption capacity of the resulting adsorbent was 382.7 mg/g. The model gas was humidified hydrogen sulfide [

17]. The sulfur adsorption capacity of coffee production waste modified by pyrolysis at 800 °C followed by processing was approximately 200 mg/g [

18].

Industrial and Municipal Waste as Low-Cost Adsorbents

Industrial enterprises produce huge amounts of solid waste as by-products. Some industrial waste is used, while other waste has no useful application besides storage or disposal. Industrial waste is available virtually free of charge and has serious disposal problems. If industrial solid waste could be used as low-cost adsorbents, it would provide a double benefit in terms of environmental pollution. First, the volume of industrial waste requiring disposal can be reduced. Second, the low-cost adsorbent from industrial waste can reduce wastewater pollution and gas emissions at reasonable cost. Due to the low cost of such adsorbents, there is no need to regenerate waste materials.

The main by-product of solid waste production in coal-fired thermal power plants is fly ash. The high silica and alumina content of fly ash makes it suitable for use as a low-cost adsorbent for industrial applications [

19]. The steel industry produces large quantities of waste such as blast furnace slag, dust and sludge, etc. In [

20], these wastes were investigated as adsorbents. Solid waste from the aluminum industry (red mud) produced during bauxite processing was considered as an adsorbent for wastewater treatment [

21]. The fertilizer industry also produces a number of by-products in large quantities that have no further use and may have a negative impact on the environment, but have good potential for use as adsorbents [

22]. Waste from the pulp and paper industry creates serious disposal problems and pollutes the environment. The experimental results showed that paper sludge from paint removal leads to the formation of mesoporous materials, while sludge from pulp production can be used to create highly porous adsorbents [

23]. Various industries produce sludge as by-products that have been investigated as adsorbents. Solid waste from distillation units is a by-product of the ammonia-soda process for the soda ash production, and has been used as an alternative adsorbent for the removal of anionic dyes from aqueous media [

24]. Bhatnagar A. et al. investigated battery industry waste for the removal of some metal ions (Pb, Cu, Cr and Zn) from aqueous solution [

25]. Sewage sludge has also been used to produce an effective adsorbent [

26].

A study [

27] proposed using materials obtained from sewage sludge as adsorbents for the extraction of hydrogen sulfide from humid air. The adsorbent obtained by carbonization at 950 °C is twice as effective as activated carbon based on coconut shell. The authors showed that with an increase in carbonization temperature, materials obtained from sludge become more adsorption active. Presumably, carbonization at 950 °C produces a mineral-like phase consisting of catalytically active metals such as iron, zinc and copper. The obtained results demonstrate that the presence of iron oxide significantly increases the capacity of carbon black and activated alumina. Sludge-derived adsorbents are effective in removing hydrogen sulfide until the pores are blocked by sulfur as a product of the oxidation reaction. There are also conclusions that chemisorption plays an important role in removing hydrogen sulfide from humid air.

The authors in [

28] used sewage sludge to obtain an adsorbent by controlling the conditions of temperature and chemical activation. Using the adsorbent derived from sewage sludge to adsorb the low concentration SO

2 in fixed bed system, the effects of the metallic derivatives on characteristics of the adsorbent were investigated at different compositions of the gaseous mixtures. It has been shown that derivatives of metals (iron, calcium, copper, nickel), especially vanadium, fixed on the adsorbent have a great influence on the sorption characteristics of the adsorbent in relation to SO

2.

The authors [

29] obtained adsorbents for desulphurization from mixtures of sewage sludge and metal sludge of various compositions and individual sludges by pyrolysis at 650, 800 and 950 °C. The pyrolysis temperature and composition of the mixture play a role in the development of final properties of adsorbents. When the content of sewage sludge is high the strong synergetic effect is noticed after high temperature of pyrolysis. Such factors as development of mesoporosity and new catalytic phases formed as a result of solid-state reactions contribute to this behavior. The removal of hydrogen sulfide on the materials obtained is complex due to the competition between H

2S and CO

2 for adsorption centers and deactivation of those centers by CO

2/H

2CO

3.

In order to fully utilize the high catalytic capacity of sludge-based adsorbents for the hydrogen sulfide oxidation, the authors in [

30] synthesized composites consisting of a sewage sludge derived phase and coconut carbon, with 10 and 30% of the latter phase. They were obtained by simple pyrolysis at 600, 800 and 950 °C. After an extensive surface characterization from the viewpoints of chemistry and porosity, their performance was tested in a hydrogen sulfide removal from a moist gas phase at ambient conditions. The results showed an improvement in the performance only for the samples obtained at 600 and 800 °C. These composites absorbed three times more hydrogen sulfide than samples obtained from untreated sludge. The improvement was linked to the availability of catalytic centers contributing to hydrogen sulfide oxidation and to an increase in the porosity from the carbon phase, where the products of reactive adsorption could be stored. On the other hand, pyrolysis of the composites at 950 °C decreased the performance in comparison with that of an only-sludge-based adsorbent (87 mg/g). It was linked to the high temperature effect of blocking the favorable chemistry of the sludge phase by the carbon particles and by blocking the pores of carbon by its sintering with the inorganic sludge-based phase.

Factors Influencing Hydrogen Sulfide Adsorption

The mechanism of H

2S adsorption is a complex process with the simultaneous influence of several key factors, namely: porosity and specific surface area [

31,

32,

33], pH [

31,

32,

34,

35], humidity [

31,

35,

36,

37], metal inclusions [

33,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41].

The main problem in waste disposal is its heterogeneity and inconsistency of composition. Waste varies in composition even if it comes from the same source and location. Efficient waste management and sorting could facilitate their intended use, but it is virtually impossible to obtain separate waste of identical composition. One of the possible solutions for adjusting the composition is based on the standardization method. This method is associated with changing the properties of waste to specified parameters before further use as adsorbents. An example is the addition of iron filings to biochar and biomass-derived carbon to improve efficiency.

Many studies have shown that the adsorption capacity for hydrogen sulfide mainly depends on the content of metal ions such as iron, magnesium and calcium. The results of work [

38] show that iron-containing sludge-based adsorbents containing calcium were the most reactive and demonstrated the greatest capacity to retain H

2S. For this particular sludge type, fairly good performance was observed even when using dehydrated (raw) sludge as the adsorbent/catalyst. Thermal treatment (gasification) of raw (dehydrated) sludges increased the capacity to absorb H

2S in all cases.

The adsorption capacity of wastes with low mineral content can be enhanced by adding iron filings, which increases their adsorption capacity by approximately 15% [

33]. Interesting results were also obtained for red clay containing natural iron oxide. Its adsorption capacity without any modifications was higher than when using biochar [

41].

Humidification of the adsorbent usually increases the adsorption capacity as reported in the previous sections. Some researchers have tried to increase the adsorption capacity of H

2S by increasing the humidity of the adsorption system in addition to pH and porosity. Some studies have shown an improvement in adsorption by almost three times with respect to low moisture content. For example, the initial water content of different types of biowaste affects the adsorption result [

41]. It has been shown that biowaste from pig farming has the highest sulfur capacity (65.4 mg/g) with a moisture content of 25 wt.%.

The presence of water causes the dissociation of H2S into H+ and HS- ions. This effect facilitates their adsorption in the subsequent process. It has also been found that humidity replaces other key factors in the H2S adsorption.

In addition to humidity and the presence of metal inclusions, chemical activation with changes in pH plays a major role. An experimental study was conducted to examine the effect of activation conditions on the adsorption efficiency of H

2S gas by drinking water treatment waste. In the study [

33], raw drinking water sludge was divided into 3 groups. In the first group, drinking water sludge was only oven dried at 105°C. For the other 2 groups, drinking water sludge was soaked in 2.5 M NaOH solution. After soaking, the sludge was divided into 2 groups (group 2 and 3). The second group was washed with distilled water until pH 7; while the third group was not. The material analysis showed that more surface area and total volume of sludge can be obtained after activated with NaOH. From the adsorption experiments, it was found that the highest adsorption capacity was 87.94 mg/g. Moreover, by adding of 20 wt.% iron filing into sludge of the third group the adsorption capacity increased to 105.22 mg/g adsorptive material.

During the adsorption process, elemental sulfur is formed in the presence of oxygen from the air. It covers the surface of the material, as a result of which the pores of the adsorbent are blocked and the process stops according to reaction (1) [

42].

In this study, a new hydrogen sulfide removal by sewage sludge-derived adsorbent without elemental sulfur precipitation was proposed. At temperatures <180 °C, the adsorbent obtained from the sludge was deactivated and showed a limited amount of hydrogen sulfide absorption—0.27 mmol/g after 60 min of the experiment. Scanning electron microscopy and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy showed that the carbon sites of the deactivated adsorbent were coated with elemental sulfur. In contrast, at temperatures >180 °C, the adsorbent achieved stable desulfurization without deactivation. As a result, the amount of hydrogen sulfide absorbed was 121.82 mmol/g after 20 h of the experiment. Sulfur efflux was a key factor determining the regeneration of active carbon sites and the continuous oxidation of H2S.

Thus, based on the results of the literature analysis, a number of unresolved problems were identified that complicate the industrial use of adsorbents from waste and natural materials. Nevertheless, a high growth in the number of available literary data on the use of low-cost adsorbents, including for the petrochemical industry, was shown. The aim of the work was to investigate a number of industrial wastes and natural materials with or without treatment as adsorbents for the removal of hydrogen sulfide from gas wastes of oil refining.

3. Materials and Methods

To test the developed and prepared sorbent compositions in laboratory conditions, a laboratory setup was assembled. The installation included a gas source, an adsorber, and a receiver with an absorbent solution. Gas from the source entered the adsorber for desulfurization, and at the adsorber’s outlet, a receiver with the absorbent solution was installed. The gas source was a chemical reaction of sodium sulfide interacting with hydrochloric acid and purging the released hydrogen sulfide with nitrogen, according to reaction 1. The amount of hydrogen sulfide released depends on the concentration of the initial solutions and their volumes. In this experiment, 100 ml of a 35 g/l solution of sodium sulfide 9-aqueous and 100 ml of a 10% hydrochloric acid solution were used. The amount of hydrogen sulfide released was determined experimentally using a blank sample. The convergence of three subsequent measurements was ±1%.

The quantitative determination of hydrogen sulfide released during the reaction and not adsorbed after the adsorber was carried out by iodometric titration and photometric method according to GOST 22387.2-2021 «Natural gas. Methods for determination of hydrogen sulfide and mercaptan sulfur».

To determine the adsorption capacity of the studied adsorbents, a spectrophotometric method was used. The content of sulfides in the absorbing solution after the adsorber was determined using a Shimadzu UV-1800 spectrophotometer at a wavelength of λ=670 nm. The adsorption efficiency was estimated quantitatively by the sulfur absorption capacity index. This index was calculated as the amount of substance (hydrogen sulfide in mg) absorbed by a unit mass of the sorbent (in g) under given adsorption conditions.

Adsorbent material compositions were developed to absorb sulfur compounds. The waste from preliminary treatment of the water treatment plant was used as a basis for the sorbent preparation. The waste was in the form of an aqueous suspension, the solid part of which mainly consisted of calcium carbonate (more than 80%), magnesium hydroxide, iron oxides, and aluminum. The qualitative composition of the waste directly depends on the reagent treatment and the source water composition. In this work, waste from the preliminary treatment of the water treatment plant of Nizhnekamsk TPP-2 was used to conduct experiments.

To use sludge as a component of the adsorbent, it is necessary to carry out its pre-treatment, which is based on the following steps:

- sludge dehydration;

- calcination of dehydrated sludge for 2 hours at 1000 °C (heating and cooling were carried out with a uniform change in temperature).

Since the sludge is predominantly composed of calcium carbonate, when it is heated (more than 840 °C), it decomposes and carbon dioxide and calcium oxide (quicklime) are released.

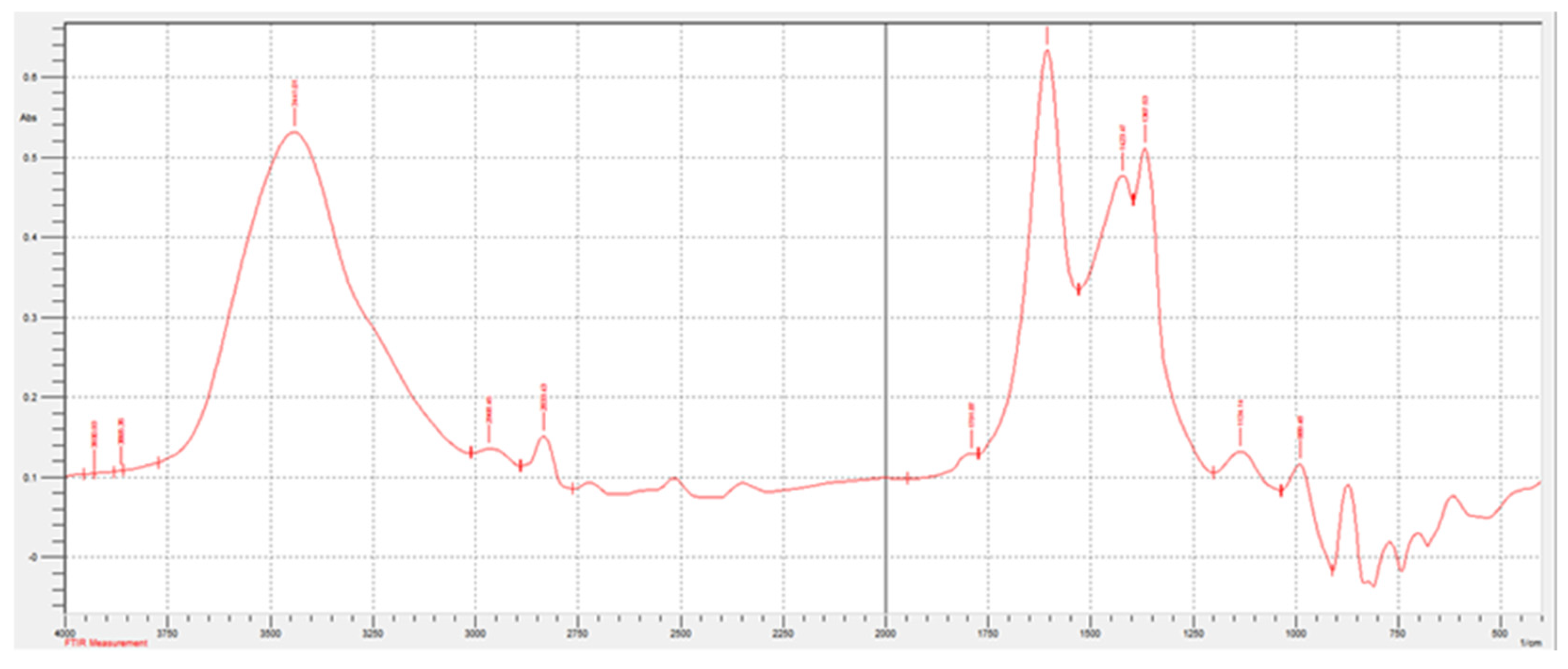

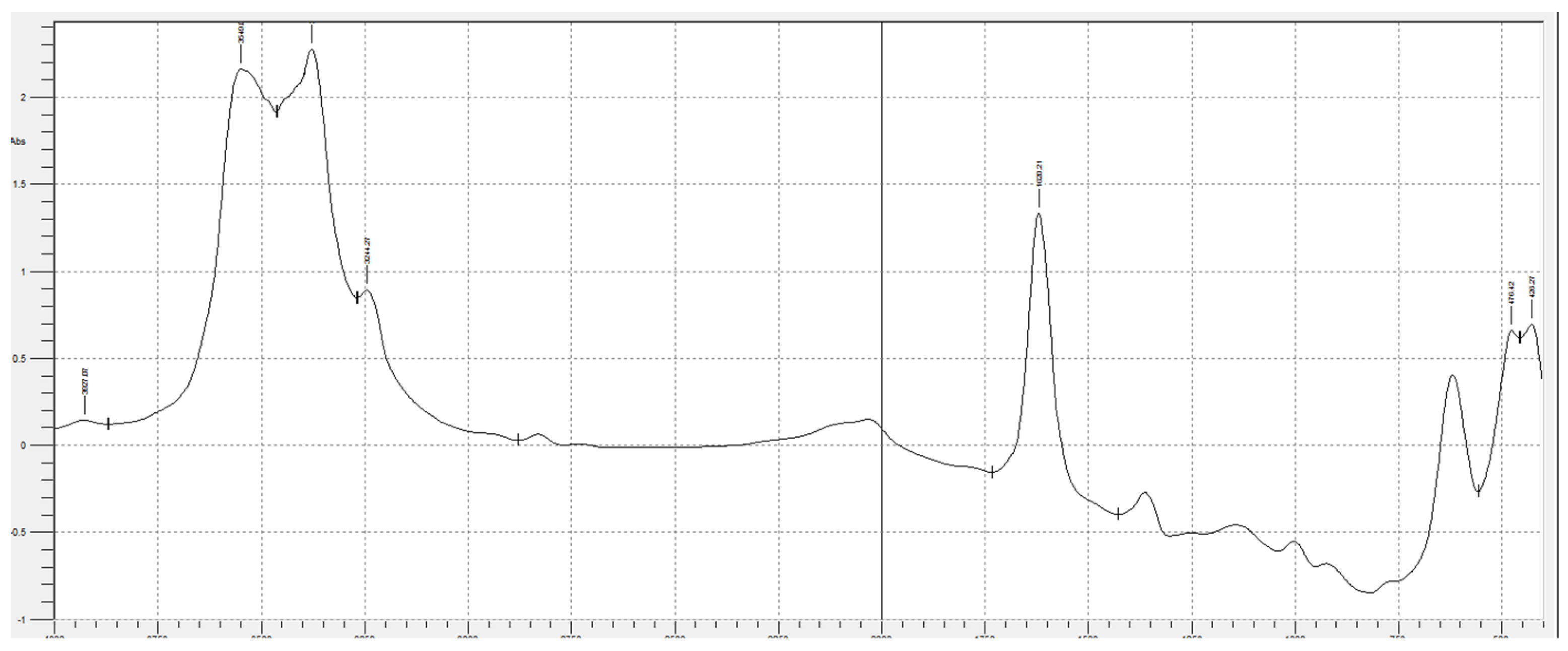

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 show the spectra of the sludge before and after pyrolysis. The spectra were obtained on a Shimadzu IRAffinity-1S IR spectrophotometer.

Table 1 shows the decoding of IR spectra based on the characteristic absorption bands of certain bonds or groups of atoms.

After preliminary treatment, soda lime was prepared from the activated sludge by adding dry sodium hydroxide in a ratio of 83/17 and mixing with distilled water (23% of the total mass of the mixture). The mixture is heated, after cooling the activated sludge can be used as an active component.

For the study, adsorption compositions were prepared, including natural materials and waste (granulated coal, bentonite clay, red clay, non-activated sludge, activated sludge, sodium metasilicate, starch, natural limestone, wood sawdust), as well as chemical reagents and commercial adsorbents (chemical lime absorbent (HP-I) of Russian and foreign production, ascarite, zeolite NaX, sodium alkali, calcium oxide, Anionite Tulsion A23CL). The composition of the obtained adsorbents and the methods of their treatment are presented in

Table 2.

The obtained adsorbents had the form of granules with a diameter of 5 mm. The criteria for selecting the prepared adsorbent samples for subsequent sorption capacity testing were based on the principles of environmental friendliness, availability, and cost-effectiveness of materials. A test of mechanical abrasion resistance was also carried out for compliance with the requirements of GOST 6755-88 «Chemical Lime Absorbent HP-I».

4. Results

The obtained results of the developed adsorbents are comparable with the indicators of adsorbents from waste and natural materials in terms of sulfur adsorption capacity, presented by researchers in the literature [

4,

5]. Based on the results of laboratory studies of the developed composite adsorbents, a high sulfur adsorption capacity was revealed in comparison with commercial adsorption materials. Powdered bentonite, a mixture of bentonite with coal, soda lime from sludge in powder form and soda lime from sludge with the addition of zinc oxide are 5-15 times higher in sulfur adsorption capacity than commercial adsorbents zeolite, HP-I, lime absorbent (

Table 2).

It has been shown that sludge from water treatment plants has good potential for capturing hydrogen sulfide, especially after preliminary heat treatment due to its content of predominantly alkaline earth metal oxides. The addition of sodium hydroxide significantly increases the sulfur adsorption capacity, which reached 377 mg/g for the soda lime sample from thermally treated sludge. However, for this sample, strong loosening of the final product is observed, with its transformation into powder form. To form spherical granules, sodium metasilicate or starch was added to the powder. They give strength to the final product, but at the same time the sulfur absorption capacity decreased by more than 10 times.

Mixing powdered sorbents with high sulfur adsorption capacity with moistened wood sawdust in a 1/1 ratio slightly reduces the sulfur absorption capacity (from 333 to 225 mg/g). But at the same time, it improves the hydrodynamic properties when the gas passes through the adsorber, due to a decrease in the bulk density of the adsorber backfill.

Sorbent samples made from red clay and primary untreated sludge have sufficient mechanical abrasion resistance (92%), measured according to GOST 6755-88, and their regeneration is possible. Although their sulfur adsorption capacity is lower than that of samples with thermally treated sludge in their composition (on average by 40%), nevertheless, after regeneration with 4% sodium alkali, their sorption capacity returns to its initial value.

The developed sludge-based adsorbents acquire a dark green color when in contact with hydrogen sulfide. The color change can be used to draw a conclusion about the degree of material depletion and the need for its replacement (

Figure 3).

Bentonite clay samples have high sulfur adsorption capacity (119.8 mg/g) and regeneration ability, but have a high percentage of mass loss after regeneration and calcination (about 20% by mass).

All samples prepared in the form of granules using molding materials (starch, sodium metasilicate, red clay, slaked lime) have a sufficient level of mechanical strength. Granulated samples were tested according to GOST 6755-88 and their mechanical abrasion resistance was at least 65%. This value corresponds to the minimum permissible limit of mechanical strength for the materials being developed.

4. Conclusions

The article presents a laboratory study of developed and commercially available adsorbents from natural and industrial waste materials for the purpose of removing hydrogen sulfide from fuel gases and gas emissions from oil production. The developed adsorbents are proposed for purifying sulfur-containing gas waste at petrochemical facilities. It is also proposed to use them for natural gas desulfurization for subsequent use as fuel or for hydrogen production by steam reforming.

The developed adsorbents showed a high level of sulfur adsorption capacity for hydrogen sulfide relative to commercially available products—activated carbon (brand BAU), chemical lime absorbent HP-I (Russia) and lime absorber Atrasorb (Portugal), ascarite, zeolite NaX, anionite Tulsion A23CL, which are offered by manufacturers for gases purification from hydrogen sulfide for industrial purposes. But it is worth noting that in the future, existing issues regarding the ability to regenerate, shape formation, etc. should be resolved.

The study demonstrates that solid waste from energy enterprises (sludge from water treatment plants) can be used with high efficiency to purify gas waste from petrochemical enterprises.

The adsorbent obtained from thermally treated sludge with the addition of sodium alkali and mixing with wood sawdust showed the best results among the developed and commercially available materials in terms of sorption efficiency, environmental friendliness, moldability, availability, and ease of production. The sulfur adsorption capacity of the sample was 225 mg/g, which allows us to consider it as a promising composite sorption material for use in the petrochemical industry.

Author Contributions

A.V. and A.F. worked on all the tasks, A.F., R.K., I.B. and A.Ch. worked on the literature review, I.I., I.B. and A.F. conducted computational studies, I.I. and A.Ch. performed the supervision, and all authors analyzed the results. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is financed by the European Union—NextGenerationEU—through the National Recovery and Resilience Plan of the Republic of Bulgaria, project N° BG-RRP-2.013-0001-C01. This research was also co-funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation “Study of processes in a fuel cell-gas turbine hybrid power plant” (project code: FZSW-2022-0001).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bhatnagar, А.; Sillanpää, M. Utilization of agro-industrial and municipal waste materials as potential adsorbents for water treatment—A review. Chemical Engineering Journal 2010, 157(2-3), 277–296.

- Аhmad, W.; Sethupathi, S.; Kanadasan, G.; Lau, L.C.; Kanthasamy, R. A review on the removal of hydrogen sulfide from biogas by adsorption using sorbents derived from waste. Reviews in Chemical Engineering 2021, 37(3), 407–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papurello, D.; Lanzini, A.; Bressan, M.; Santarelli, M. H2S Removal with Sorbent Obtained from Sewage Sludges. Processes 2020, 8(2), 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamukamba, P.; Mukumba, P.; Chikukwa, E.S.; Makaka, G. Hydrogen Sulphide removal from biogas: A review of the upgrading techniques and mechanisms involved. International Journal oRenewable Energy Research 2022, 12(1), 557–568. [Google Scholar]

- Pudi, A.; Rezaei, M.; Signorini, V.; Andersson, M.P.; Baschetti, M.G.; Mansouri, S.S. Hydrogen sulfide capture and removal technologies: a comprehensive review of recent developments and emerging trends. Separation and Purification Technology 2022, 298(9), 121448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmedna, M.; Marshall, W.E.; Rao, R.M. Production of granular activated carbons from select agricultural by-products and evaluation of their physical, chemical and adsorption properties. Bioresource Technology 2000, 71(2), 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toles, C.A.; Marshall, W.E.; Johns, M.M. Phosphoric acid activation of nutshells for metal and organic remediation: process optimization. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology 1998, 72, 255–263.

- Wafwoyo, W.; Seo, C.W.; Marshall, W.E. Utilization of peanut shells as adsorbents for selected metals. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology 1999, 74, 1117–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Nyazi, K.; Yaacoubi, A.; Baçaoui, A.; Bennouna, C.; Dahbi, A.; Rivera-utrilla, J.; Moreno-castilla, C. Preparation and characterization of new adsorbent materials from the olive wastes. Journal de Physique IV (Proceedings) 2005, 123, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, T.; Wayne, M.E. Copper ion removal by almond shell carbons and commercial carbons: batch and column studies. Separation Science and Technology 2002, 37(10), 2369–2383. [Google Scholar]

- Soleimani, M.; Kaghazchi, T. Activated hard shell of apricot stones: a promising adsorbent in gold recovery. Chinese Journal of Chemical Engineering. 2008, 16(1), 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessier, M.C.; Shull, J.C.; Miller, D.J. Activated carbon from cherry stones. Carbon 1994, 30(8), 1493–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, L.B. Adsorption characteristics of activated carbon obtained from rice husks by treatment with phosphoric acid. Adsorption Science & Technology 1996, 13, 317–325. [Google Scholar]

- Elizalde-González, M.P.; Mattusch, J.; Wennrich, R. Chemically modified maize cobs waste with enhanced adsorption properties upon methyl orange and arsenic. Bioresource Technology 2008, 99(11), 5134–5139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girgis, B.S.; Khalil, L.B.; Tawfik, T.A.M. Activated carbon from sugar cane bagasse by carbonization in the presence of inorganic acids. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology 1994, 61(1), 87–92.

- Namasivayam, C.; Sangeetha, D. Recycling of agricultural solid waste, coir pith: removal of anions, heavy metals, organics and dyes from water by adsorption onto ZnCl2 activated coir pith carbon. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2006, 135(1-3), 449–452.

- Shang, G.; Shen, G.; Liu, L.; Chen, Q.; Xu, Z. Kinetics and mechanisms of hydrogen sulfide adsorption by biochars. Bioresource Technology 2013, 133, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowicki, P.; Skibiszewska, P.; Pietrzak, R. Hydrogen sulphide removal on carbonaceous adsorbents prepared from coffee industry waste materials. Chemical Engineering Journal 2014, 248, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wu, H. Environmental-benign utilisation of fly ash as low-cost adsorbents. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2006, 136(3), 482–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Delgado, A.; Pérez, C.; López, F.A. Sorption of heavy metals on blast furnace sludge. Water Research 1998, 32(4), 989–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, E.; Soto, B.; Arias, M.; Núńez, A.; Rubinos, D.; Barral, M.T. Adsorbent properties of red mud and its use for wastewater treatment. Water Research 1998, 32(4), 1314–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.K.; Ali, I. Removal of endosulfan and methoxychlor from water on carbon slurry. Environmental Science & Technology 2008, 42(3), 766–770.

- Méndez, A.; Barriga, S.; Fidalgo, J.M.; Gascó, G. Adsorbent materials from paper industry waste materials and their use in Cu(II) removal from water. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2009, 165(1-3), 736–743.

- Şener, S. Use of solid wastes of the soda ash plant as an adsorbent for the removal of anionic dyes: equilibrium and kinetic studies. Chemical Engineering Journal 2008, 138(1-3), 207–214.

- Bhatnagar, A.; Minocha, A.K.; Kim, S.-H.; Jeon, B.-H. Removal of some metal ions from water using battery industry waste and its cement fixation. Fresenius Environmental Bulletin 2007, 16(9 A), 1049–1055. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.Y.; Wang, P.; Zhuang, Y.Y. Dye removal from wastewater using the adsorbent developed from sewage sludge. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2005, 17(6), 1018–1021. [Google Scholar]

- Bagreev, A.; Bashkova, S.; Locke, D.C.; Bandosz, T.J. Sewage Sludge-Derived Materials as Efficient Adsorbents for Removal of Hydrogen Sulfide. Environmental Science & Technology 2001, 35(7), 1537–1543.

- Zhai, Yb.; Wei, Xx.; Zeng, Gm.; Zhang, Dj. Effects of metallic derivatives in adsorbent derived from sewage sludge on adsorption of sulfur dioxide. Journal of Central South University of Technology 2004, 11, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Bandosz, T.J. Removal of hydrogen sulfide from biogas on sludge-derived adsorbents. Fuel 2007, 86(17-18), 2736–2746.

- Florent, M.; Policicchio, A.; Niewiadomski, S.; Bandosz, T.J. Exploring the options for the improvement of H2S adsorption on sludge derived adsorbents: Building the composite with porous carbons. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 249, 119412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, G.; Zhang, L.; Sun, Z. Preparation of high performance H2S removal biochar by direct fluidized bed carbonization using potato peel waste. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2017, 107, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, R.; Seredych, M.; Zhang, P.; Bandosz, T.J. Municipal waste conversion to hydrogen sulfide adsorbents: investigation of the synergistic effects of sewage sludge/fish waste mixture. Chemical Engineering Journal 2014, 237, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polruang, S.; Banjerdkij, P.; Sirivittayapakorn, S. Use of drinking water sludge as adsorbent for H2S gas removal from biogas. Environ Asia 2017, 10(1), 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, G.; Shen, G.; Liu, L.; Chen, Q.; Xu, Z. Kinetics and mechanisms of hydrogen sulfide adsorption by biochars. Bioresource Technology 2013, 133, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Cao, X.; Zhao, L.; Sun, T. Comparison of sewage sludge- and pig manure-derived biochars for hydrogen sulfide removal. Chemosphere 2014, 111, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obis, M.F.; Germain, P.; Troesch, O.; Spillemaecker, M.; Benbelkacema, H. Valorization of MSWI bottom ash for biogas desulfurization: influence of biogas water content. Waste Management 2017, 60, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicki, P.; Skibiszewska, P.; Pietrzak, R. Hydrogen sulphide removal on carbonaceous adsorbents prepared from coffee industry waste materials. Chemical Engineering Journal 2014, 248, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, A.; Montes-Moran, M.A.; Fuente, E.; Nevskaia, D.M.; Martin, M.J. Dried sludges and sludge-based chars for H2S removal at low temperature: influence of sewage sludge characteristics. Environmental Science & Technology 2006, 40, 302–309. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, F.J.G.; Aguilera, P.G.; Ollero, P. Biogas desulfurization by adsorption on thermally treated sewage sludge. Separation and Purification Technology 2014, 123, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhu, Y.; Bian, S.; Ko, J.H.; Li, S.; Xu, Q. H2S adsorption by municipal solid waste incineration (MSWI) fly ash with heavy metals immobilization. Chemosphere 2018, 195, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skerman, A.G.; Heubeck, S.; Batstone, D.J.; Tait, S. Low-cost filter media for removal of hydrogen sulphide from piggery biogas. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2017, 105, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, J.; Liu, Q.; Qian, G. Continuous oxidation of hydrogen sulfide by an adsorbent derived from sewage sludge. Environmental Engineering Science 2019, 36(9), 1170–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).