3.1. Empirical Mode Decomposition

Let be some analyzed time series with discrete time index.

Empirical mode decomposition (EMD) [

18,

19] represents the decomposition of the signal into empirical oscillation modes:

where

is the

j-th empirical mode,

is the remainder,

is the number of empirical modes.

The algorithm for decomposing into a sequence of empirical modes is iterative for each level

. We denote by

the iteration index:

, where

is the maximum number of iterations for level

. The iterations are described by the formula

Here , where and are the upper and lower envelopes for the signal , which are constructed using spline interpolation (usually a 3rd order spline) over all local maxima and minima of the signal .

Iterations (2) are initialized with a zero step for the first level () of the expansion . Then the upper and lower envelopes and are found, the average line is calculated and is found using formula (2). For the upper and lower envelopes and are determined and the average line , is found, and so on, up to the last iteration index , after which the first empirical mode is considered to be found.

The condition for stopping the iterations is usually chosen in the form of the inequality:

where

is some small number, such as 0.01. Once the mode

is found, an iterative process is started to determine the empirical mode

of the next level. This process is initialized by the formula for the initial iteration index

:

According to formula (4), the high-frequency part is subtracted from the original signal and the resulting, lower-frequency signal is considered as a new signal for subsequent decomposition. The construction of empirical oscillation modes continues until the number of local extrema becomes too small to be used to construct envelopes.

As the empirical mode level number

increases, the signals

become increasingly low-frequency and tend to an unchangeable form. The sequence

is constructed in such a way that its sum gives an approximation to the original signal

, which can be represented as (1) [

18,

19].

Empirical modes of oscillations, known as Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMF), are orthogonal to each other, thus constituting a certain empirical basis for the decomposition of the original signal. In what follows, the decomposition levels will be called IMF levels.

In practical implementation of the method, technical difficulties arise due to edge effects, since the behavior of envelopes beyond the first and last points of local extrema is ambiguous. There are several approaches to overcome this difficulty, in particular, a mirror continuation of the analyzed sample back and forth over a sufficiently long period of time. It was used in this work.

3.2. Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition

One of the key drawbacks of the EMD method is the problem of mode mixing, which occurs when one empirical mode includes signals of different scales or when signals of the same scale are distributed among different empirical modes. For example, if the signal exhibits "intermittency", i.e. short-term sections of higher-frequency behavior appear against the background of a smooth signal, then the EMD decomposition results in mixing of behavior modes with different frequencies, since the relatively rare points of local extrema of smooth behavior alternate with significantly more frequent points of local extrema of the high-frequency component.

To overcome this effect, Huang and Wu [

19] proposed the ensemble empirical mode decomposition (EEMD) method. It is a regularization of the EMD method in which finite-amplitude white noise is added to the original data. This allows the true empirical modes to be determined as the average over an ensemble of trials, each of which is the sum of the signal and white noise.

The EEMD algorithm includes the following steps:

1. Add a white noise realization to the original data.

2. Decompose the white noise-added data into empirical modes.

3. Repeat steps 1 and 2 a sufficiently large number of times with independent white noise realizations.

4. Obtain an ensemble mean for the corresponding empirical modes.

In this way, numerous “artificial” observations are simulated in the real time series:

where

is the

i-th independent realization of white noise.

The true component in the behavior of time series, according to the EEMD definition, for a sequence of all levels of empirical modes is calculated as their average value of the expansions of artificially noisy modes (5).

It is important to note that the use of EEMD largely eliminates the above-mentioned mode mixing problem [Huang and Wu, 2008]. Adding independent white noise to the sample has a regularizing effect, since it simplifies the construction of envelopes (after adding a small white noise, there are immediately many local extrema). The operation of averaging over a sufficiently large number of independent realizations of white noise allows one to get rid of the influence of the noise component and to isolate the true internal modes of oscillations of time series of meteorological parameters.

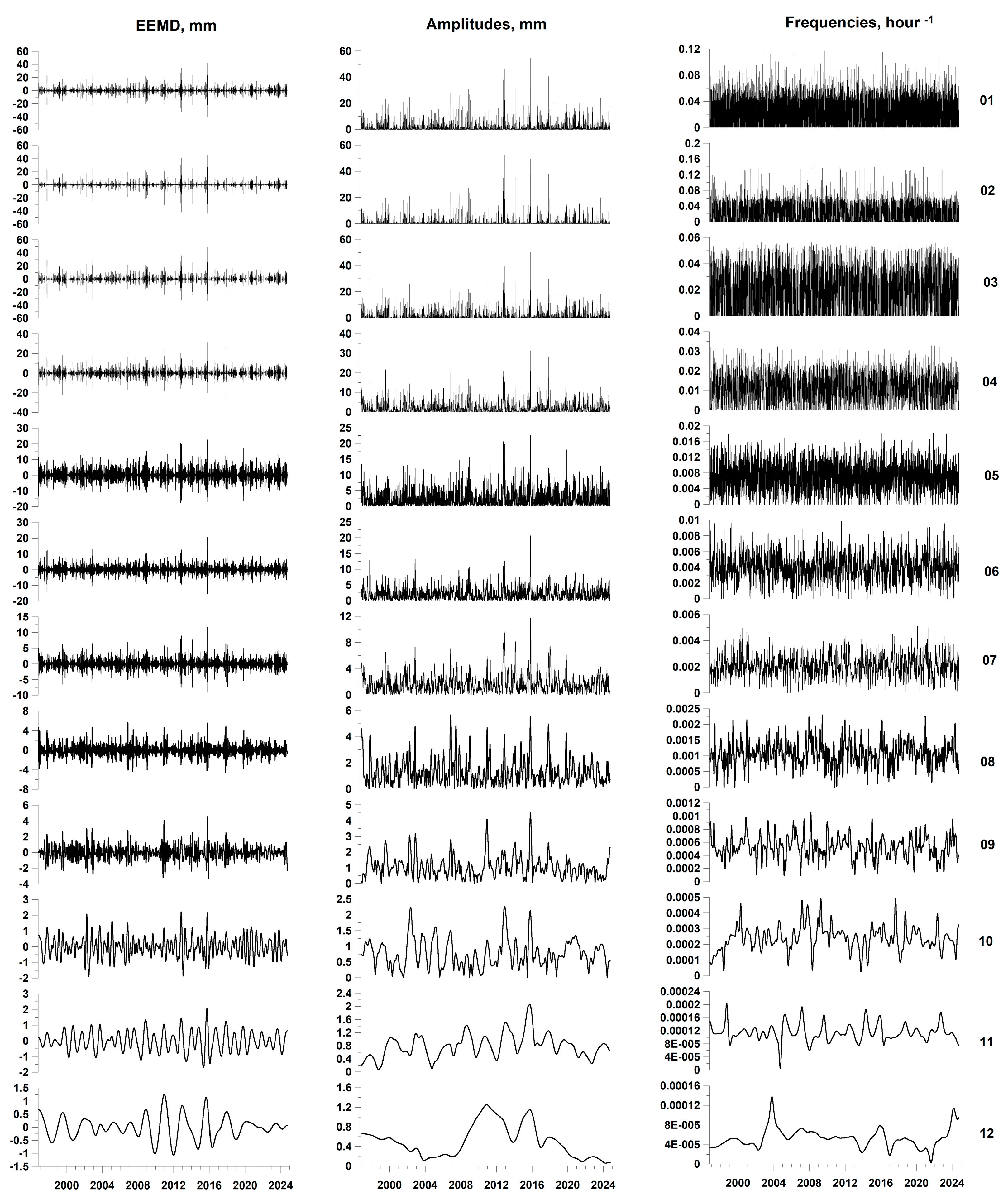

For each of the time series (

Figure 1), EEMD waveforms were calculated by averaging 2000 decompositions of the original signals, to which independent Gaussian white noise with a standard deviation equal to 0.1 of the standard deviation of each decomposed signal was added.

3.3. Hilbert Transform

The Hilbert transform [

20]

of a signal

is determined by the formula:

where

– convolution of two functions. If

и

– Fourier transforms of convoluted functions,

, then, as is known, the Fourier transform of a convolution is equal to the product of the Fourier transforms of the functions being convolved. The Fourier transform of

equals:

Thus, if

is a Fourier transform of

, then

If present

, then

Let be some analyzed time series with discrete time index.

In practice, it is more convenient to calculate the Hilbert transform using the concepts of an analytical signal:

where

are the amplitudes of the signal

envelope, and

is the instantaneous phase. The derivative

is called the instantaneous frequency. The Fourier transform of the analytical signal

can be written as:

after which the Hilbert transform is equal to the imaginary part of the result of the inverse Fourier transform of

:

For a discrete-time signal

, this transform can be calculated using the discrete Fourier transform:

after which the 2nd part of the Fourier coefficients (corresponding to negative frequencies) should be set to zero

: while the 1st part should be doubled

. After this, the Hilbert transform is calculated as the imaginary part of the inverse discrete Fourier transform:

Thus, after determining the instantaneous amplitudes and frequencies of the EEMD, the Hilbert-Huang expansion can be represented as follows:

In the work [

21], the Hilbert-Huang expansion was used to search for the predictive properties of the tremor of the earth's surface measured by space geodesy on the Japanese islands.

The further plan of action was to compare the times of the largest local maxima of the correlations between the amplitudes of the envelopes at different levels with the times of sufficiently strong earthquakes. In this case, the number of the largest local maxima of the correlations of the amplitudes of the envelopes is chosen to be equal to the number of seismic events under consideration.

Below, in

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, the EEMD waveform graphs are presented for levels 1 to 12 of all time series of meteorological parameters, the amplitude graphs of their envelopes and instantaneous frequencies calculated using the Hilbert transform.

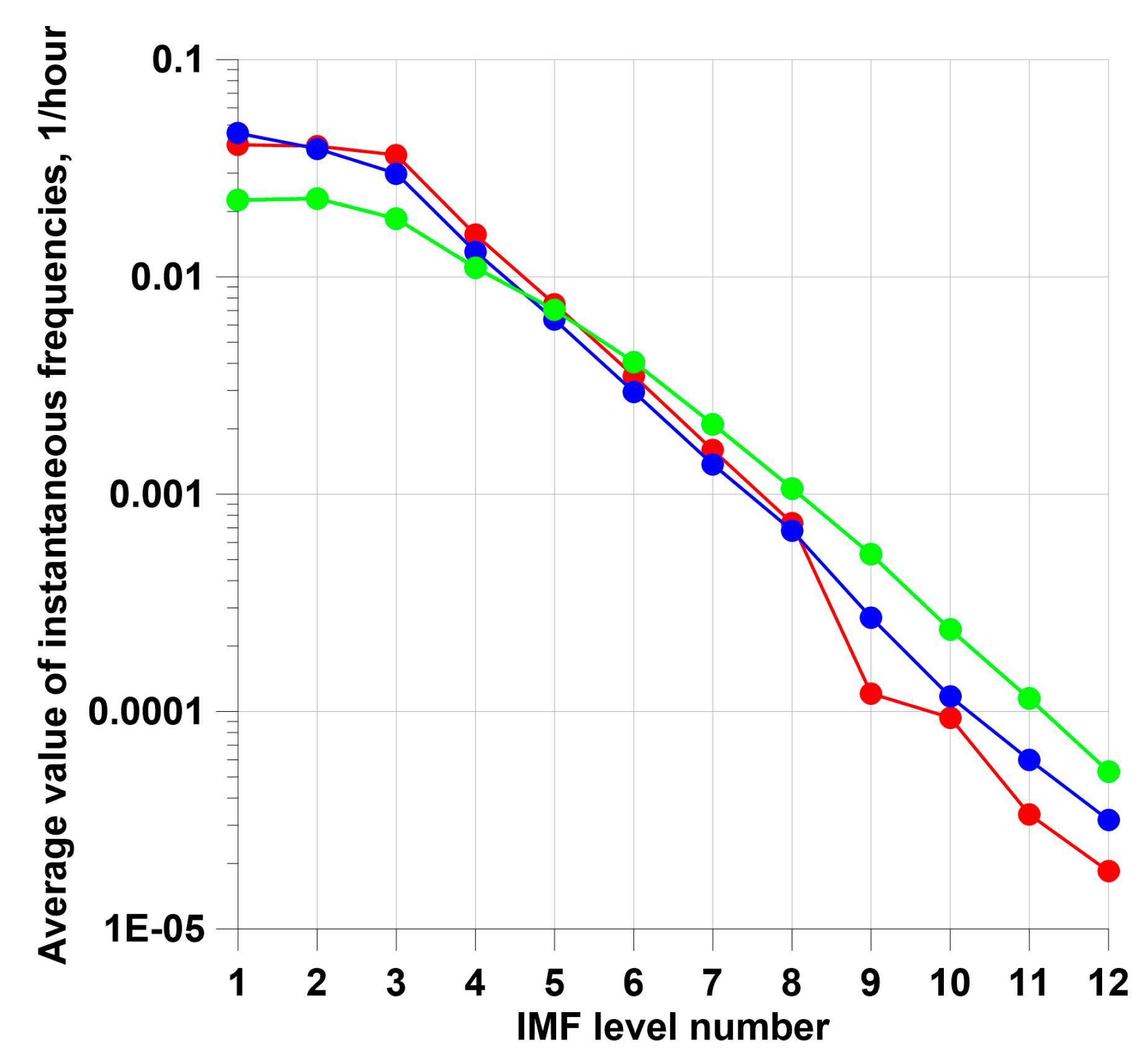

The Hilbert-Huang decomposition resembles the wavelet decomposition in its form (functionally): as in the wavelet decomposition, with an increase in the IMF level number, the corresponding component becomes increasingly low-frequency. However, there is a significant difference, which lies in the dependence of both the amplitude and the frequency on time, which is expressed by formula (15). In the orthogonal wavelet decomposition, the frequency band corresponding to the detail level with the number is fixed and corresponds to the frequency interval

, where

,

, where

is the discretization step in time [

22]. In the Hilbert-Huang decomposition, there is no such one-to-one correspondence. Therefore, to estimate the characteristic frequency of each IMF level, a value equal to the time average of all instantaneous frequency values was used.

Figure 6 shows the average values of instantaneous frequencies of meteorological parameters depending on the IMF level number.

3.4. Influence Matrix

The next stage of the analysis is the study of the relationship between two sequences of random events, which in this study represent the sequence of the largest local maxima of the envelopes of the initial series of meteorological parameters determined by the algorithm described above, and the sequence of 418 earthquakes with .

To solve this problem, a parametric model of the intensity of two point processes is used.

Previously, in [

23,

24], this method was used to test the hypotheses that local extremes of the mean values of certain seismic noise and magnetic field statistics precede the times of strong earthquakes. In [

21], this model was used to estimate the seismic forecasting properties of the positions of local maxima of instantaneous amplitudes of the envelopes of ground tremor on the Japanese islands, measured by GPS.

Let's consider the computational algorithm. Let represent the moments of time of 2 streams of events. In our case, these are:

1) a sequence of time moments corresponding to the largest local maxima of the envelope amplitudes at some IMF levels of the EEMD decomposition;

2) the sequence of times of seismic events with a magnitude not less than a given value (in our case, with a magnitude of ML≥5.5).

Let us represent the intensities of these two streams of events as follows:

where

are the parameters,

is the influence function of events

of the flow with number

:

According to formula (16), the weight of the event with number becomes non-zero for times and decays with characteristic time . The parameter determines the degree of influence of the flow on the flow . The parameter determines the degree of influence of the flow on itself (self-excitation), and the parameter reflects a purely random (Poisson) component of intensity. Let us fix the parameter and consider the problem of determining the parameters .

The log-likelihood function for a non-stationary Poisson process is equal to over the time interval

[

25]:

It is necessary to find the maximum of functions (18) with respect to parameters

. It is easy to obtain the following expression:

Since the parameters

must be non-negative, each term on the left side of formula (19) is equal to zero at the point of maximum of function (18) – either due to the necessary conditions of the extremum (if the parameters are positive), or, if the maximum is reached at the boundary, then the parameters themselves are equal to zero. Consequently, at the point of maximum of the likelihood function, the equality is satisfied:

Let's substitute the expression

from (20) into (19) and divide by

. Then we get another form of formula (20):

where

- the average value of the influence function. Substituting

from (21) into (18), we obtain the following maximum problem:

where

, under restrictions:

Function (23) is convex with negative definite Hessian and, therefore, problem (23-24) has a unique solution. Having solved problem (23-24) numerically for a given

, we can introduce the elements of the influence matrix

according to the formulas:

The quantity

is a part of the average intensity of the process

with a number

, which is purely stochastic, the part

is caused by the influence of self-excitation

and

is determined by the external influence

. From formula (21) follows the normalization condition:

As a result, we can determine the influence matrix:

The first column of matrix (27) is composed of Poisson shares of average intensities. The diagonal elements of the right submatrix of size consist of self-excited elements of average intensity, while the off-diagonal elements correspond to mutual excitation. The sums of the component rows of the influence matrix (27) are equal to 1.

3.5. Relationship Between Local Maxima of the Instantaneous Amplitudes of Meteorological Parameters and Seismic Events

The further plan is to use the influence matrix apparatus to assess the relationship between the times of maximum amplitudes of the envelopes of meteorological time series and the times of strong earthquakes.

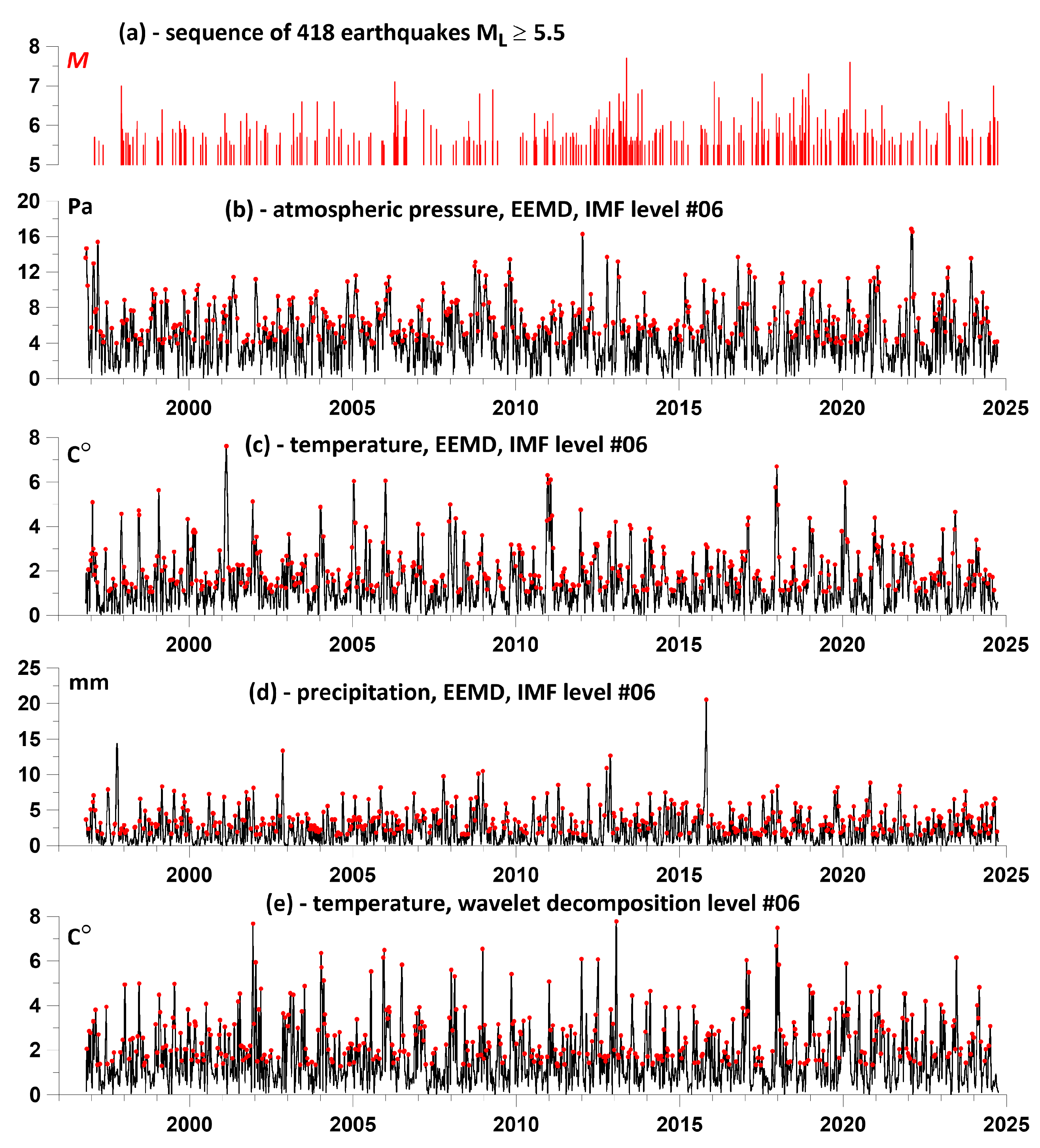

The threshold of local earthquake magnitudes for the Kamchatka Peninsula region in the KB GS RAS control zone was defined as . There were 418 such seismic events during the studied period (average recurrence of 15 events/year or 1.25 events/month).

The working hypothesis was investigated, which consisted in the fact that for certain levels of decomposition, the moments of time of the largest local maxima of the amplitudes of the envelope meteorological parameters "on average" precede the moments of time of earthquakes. In confirming this hypothesis, we assume that the maxima of meteorological parameters precede the occurrence of strong earthquakes, i.e. there is an effect of an advanced connection between meteorological parameters and strong earthquakes.

For a correct comparison of two event flows, their average intensities must be approximately equal. This means that the number of the largest local maxima of the amplitudes of the envelopes of meteorological parameter series must be equal to the number of earthquakes, i.e. 418. It should also be taken into account that with an increase in the number of the decomposition level, both the waveforms of the levels themselves and the amplitudes of their envelopes become increasingly low-frequency. As a result, it is possible to select 418 largest local maxima of the amplitudes of the envelopes only for a certain number of lower decomposition levels.

As a result of sorting through the IMF levels for all three series of the EEMD decomposition (

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5), the 6th IMF level was chosen as the optimal one, for which the “direct” influence of the moments of time of the largest local maxima of the amplitudes of the envelopes on the moments of time of seismic events with a magnitude of at least 5.5 significantly exceeded the “reverse” influence.

This means that in the range of low instantaneous frequencies of the 6th level of decomposition, the amplitudes of the envelopes of meteorological time series precede the moments of time of sufficiently strong earthquakes and one can assume the presence of a prognostic effect.

Another possibility for extracting the amplitudes of the envelopes of narrow-band components of time series is to use wavelet decomposition with subsequent calculation of the amplitudes of the envelopes from each level of detail using the Hilbert transform. However, this method turned out to be less effective for studying the leading influence of meteorological parameters on seismic events than the Hilbert-Huang decomposition, with the exception of the air temperature time series. The behavior of the air temperature time series is quite smooth (

Figure 1b), as a result of which the optimal Daubechies wavelet with 10 vanishing moments was determined for this time series from the condition of minimum entropy of the distribution of squares of wavelet coefficients [

22]. The prognostic effect of such an analysis of the air temperature time series turned out to be most effective for the 6th detail level using wavelet decompositions. With a sampling time step of 3 hours, this level corresponds to a range of periods of 8-16 days, that is, it is in the low-frequency range of 0.53-0.27 month

-1.

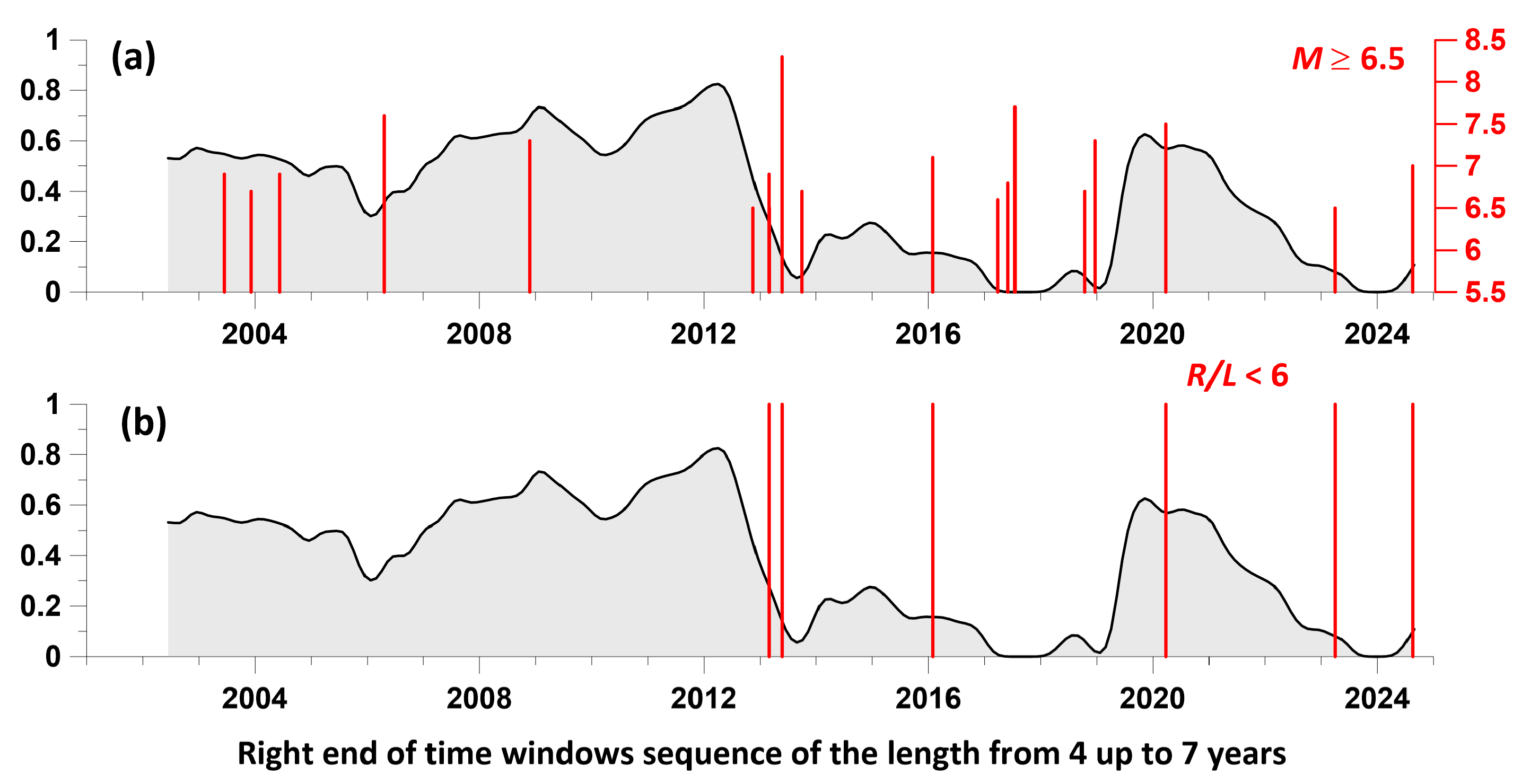

Figure 7(a) shows a sequence of earthquakes with magnitudes

. Then,

Figure 7(b, c, d) show the graphs of the envelope amplitudes at the 6th IMF level of the EEMD decomposition of the time series of atmospheric pressure, air temperature and precipitation. In addition,

Figure 7(e) shows the graph of the envelope amplitude of the wavelet decomposition of the air temperature time series at the 6th level of detail using the Daubechies wavelet with 10 vanishing moments.

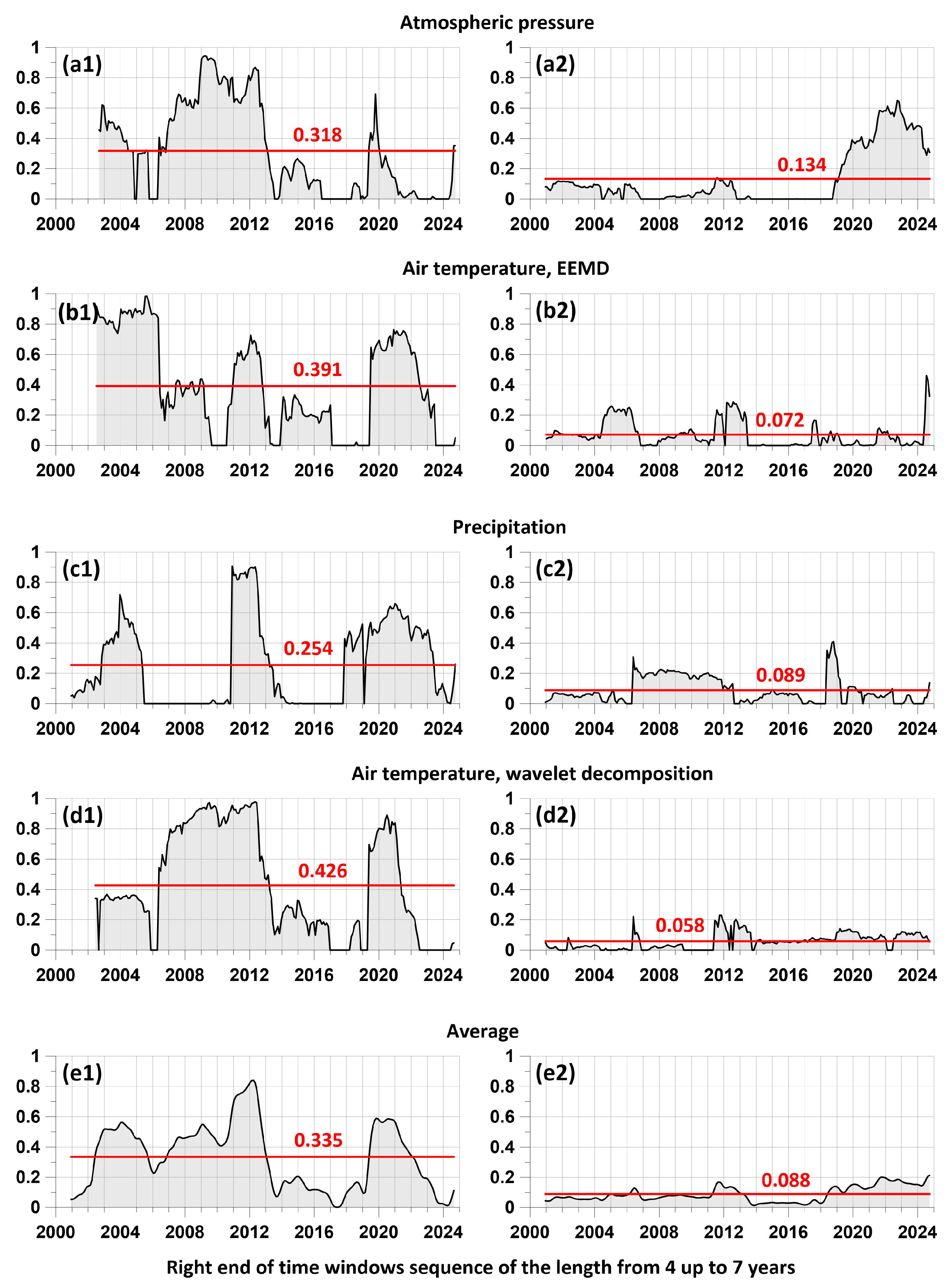

When analyzing variations of the components of influence matrices in sliding time windows corresponding to the mutual influence of the analyzed time sequences, the main attention is paid to their local maxima with their subsequent averaging. Below is described a method for processing these local maxima and averaging them for a set of time window lengths changing within specified limits.

1. The minimum and maximum lengths of time windows are selected and - the number of lengths of time windows in this interval. Thus, the lengths of time windows took the values , , . In our calculations, we took equal to 4 years, and - 7 years, .

2. Each time window of length shifted from left to right along the time axis with some offset . Let us denote by , the sequence of time moments of the positions of the right windows of length . The number of time windows of length is determined by their time offset . We used a time window offset of 0.05 years.

3. For each position of the time window of length , the elements of the influence matrix (27) are estimated for a given relaxation time of the model (16-17), corresponding to the mutual influence of the two analyzed processes. We took a value equal to 0.5 years. For definiteness, we will consider some one influence, for example, of the first process on the second. As a result of such estimates, we obtain their values in the form , where is the corresponding element of the influence matrix for the position with the number of the time window of length .

4. In the sequence , we select elements corresponding to local maxima of values , that is, from the condition .

5. We choose a "small" time interval of length and for a sequence of such time fragments we calculate the average value of local maxima for which their time marks belong to these fragments. Averaging is performed over all lengths of time windows. In our calculations we took the length equal to 0.1 years.

Thus, the complete set of free parameters of the influence matrix method is: , , , , , .