Submitted:

22 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Material

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Perforin Staining and Flow Cytometry Analysis

3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Patient Characteristics

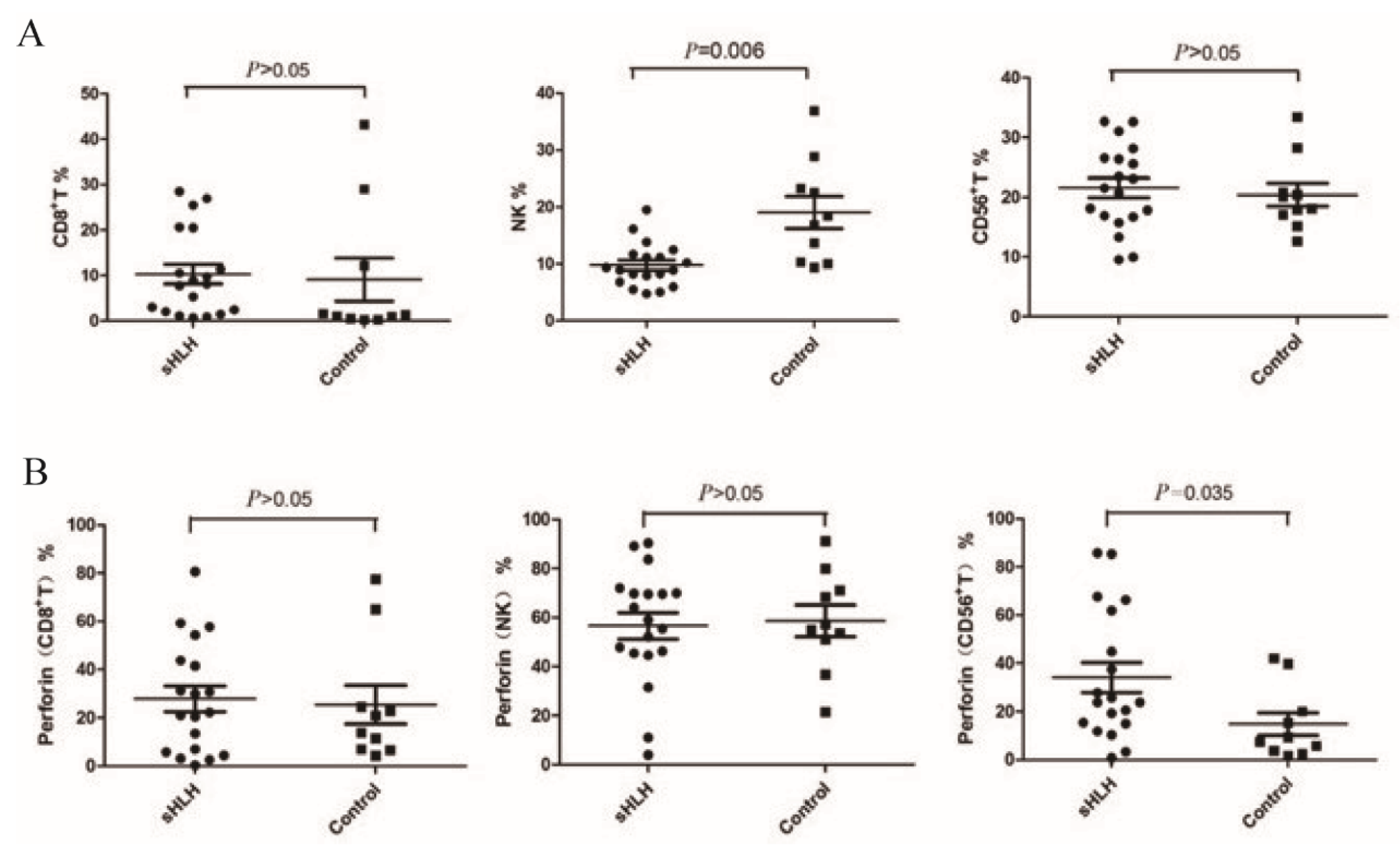

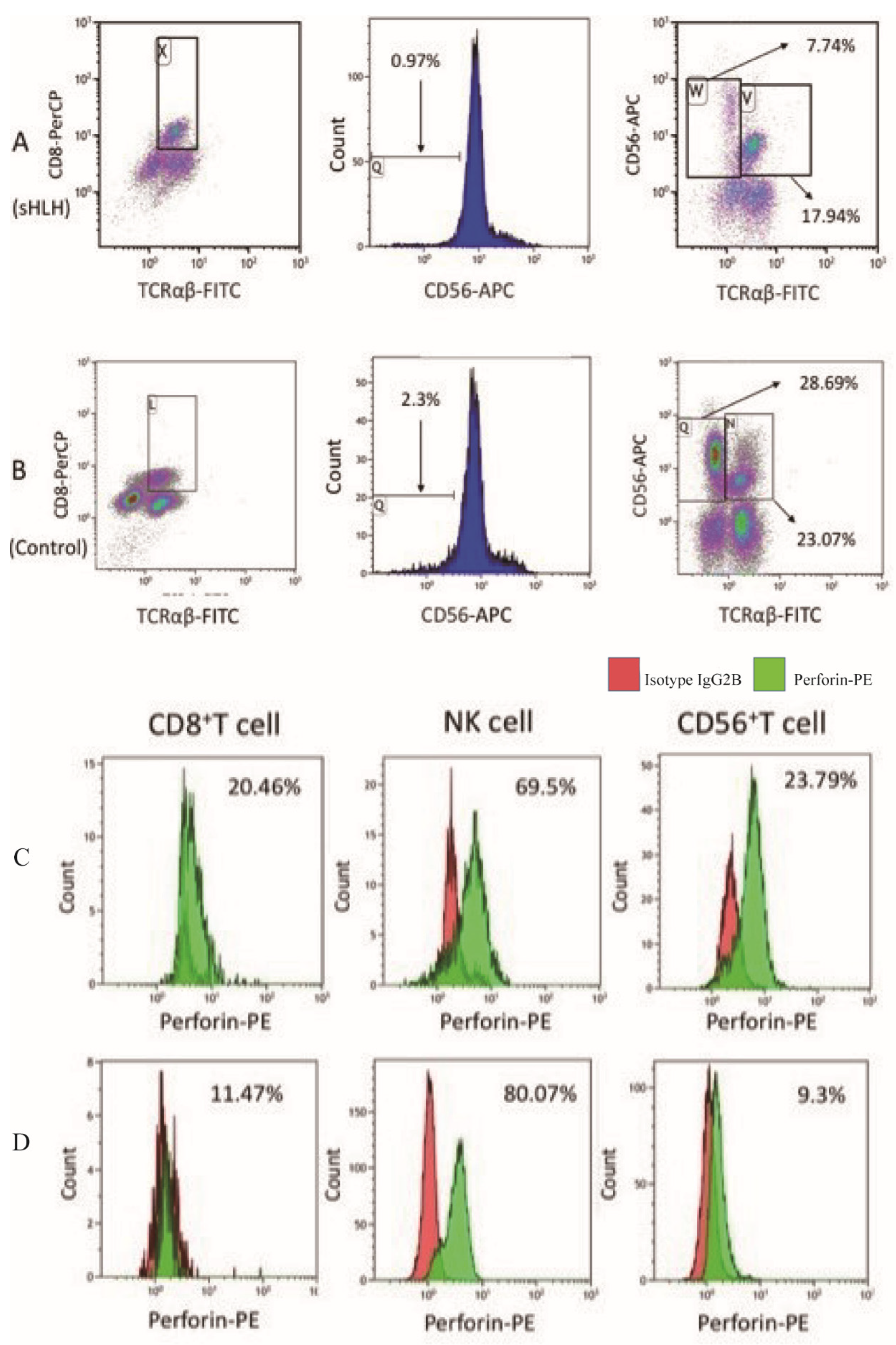

4.2. Comparison of the Proportions of Cytotoxic Lymphocytes and Perforin Expression Between Newly Diagnosed sHLH and Healthy

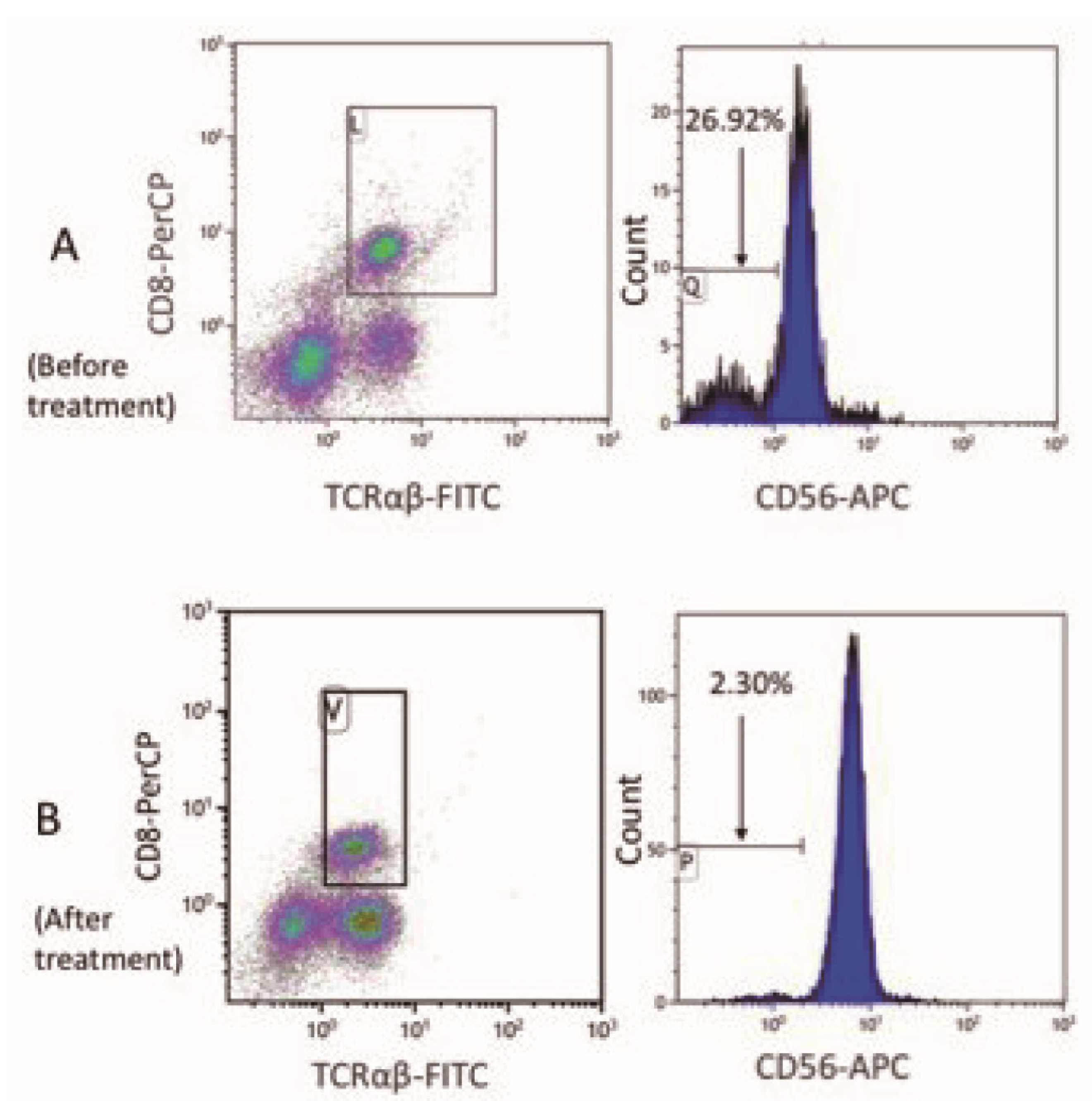

4.3. Comparison of the Cytotoxic Lymphocyte Proportion and Perforin Protein Expression Between Patients in Clinical Remission from sHLH and Newly Diagnosed sHLH

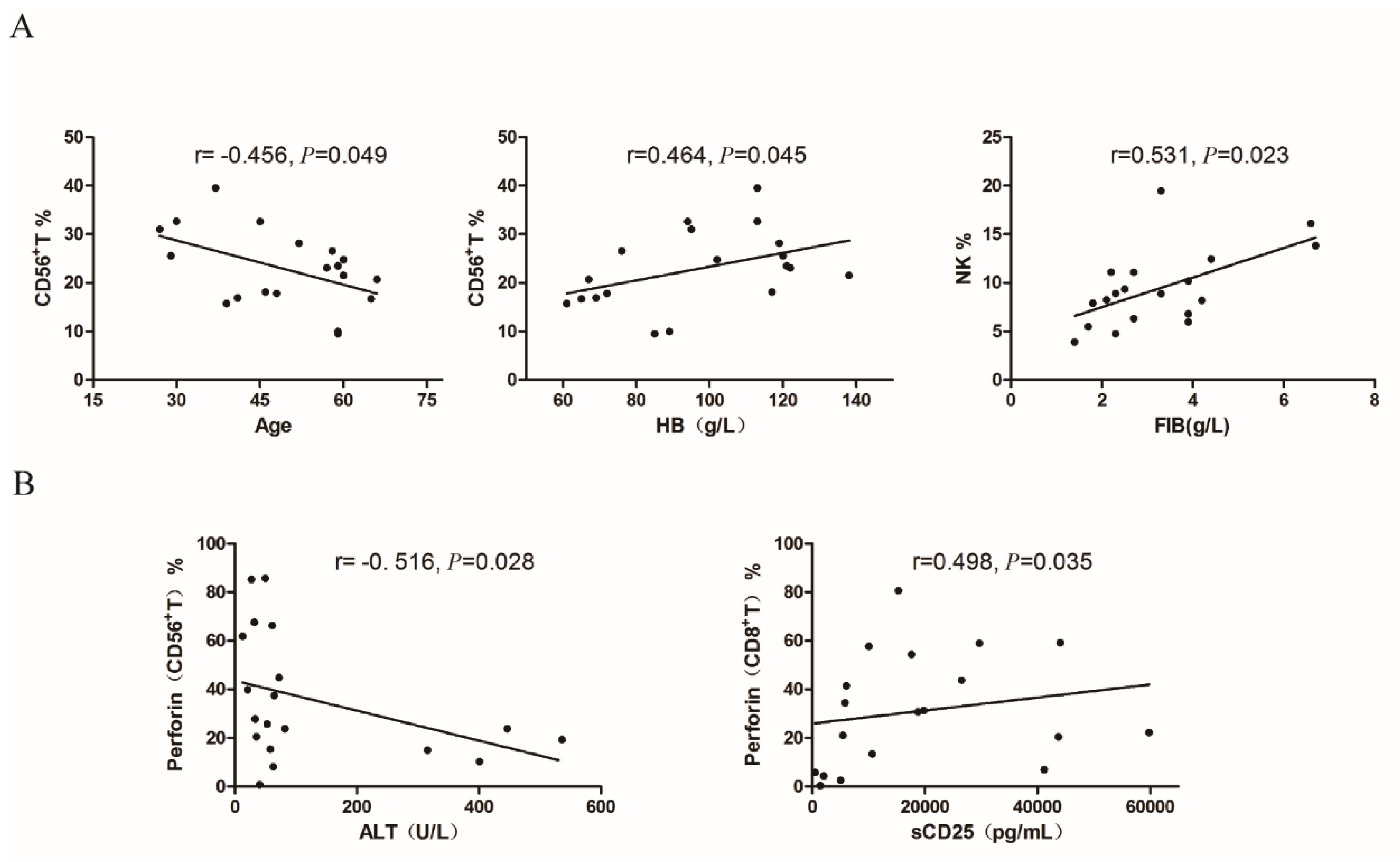

4.4. Correlation Analysis Between the Proportion of Cytotoxic Lymphocytes and Clinical Parameters in Newly Diagnosed sHLH Patients

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang L; Zhou J; Sokol L. Hereditary and acquired hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Cancer Control. 2014, 21, 4, 301-312.

- Janka GE; Lehmberg K. Hemophagocytic syndromes--an update. Blood Rev. 2014, 28, 4, 135-142.

- Murohashi I; Yoshida K; Ihara N; Wakao D; Yagasaki F; Nakamura Y; Kawai N; Matsuda A; Jinnai I; Bessho M. Serum levels of Thl/Th2 cytokines, angiogenic growth factors, and other prognostic factors in young adult patients with hemophagocytic syndrome. Lab Hematol. 2006, 12, 2, 71-74.

- Voskoboinik I; Trapani JA. Addressing the mysteries of perforin function. Immunol Cell Biol. 2006, 1, 66–71. [Google Scholar]

- Zur Stadt U; Beutel K; Kolberg S; Schneppenheim R; Kabisch H; Janka G; Hennies HC. Mutation spectrum in children with primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: molecular and functional analyses of PRF1, UNC13D, STX11, and RAB27A. Hum Mutat. 2006, 27, 1, 62-68.

- Kogawa K; Lee SM; Villanueva J; Marmer D; Sumegi J; Filipovich AH. Perforin expression in cytotoxic lymphocytes from patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and their family members. Blood. 2002, 99, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filipovich, AH. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) and related disorders. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzawi M; Bradley B; Jeffery PK; Frew AJ; Wardlaw AJ; Knowles G; Assoufi B; Collins JV; Durham S; Kay AB. Identification of activated T lymphocytes and eosinophils in bronchial biopsies in stable atopic asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990, 142 6 Pt 1, 1407–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janka G; Imashuku S; Elinder G; Schneider M; Henter JI. Infection- and malignancy-associated hemophagocytic syndromes. Secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1998, 12, 2, 435-444.

- Girardi AJ; Weinstein D; Moorhead PS. SV40 transformation of human diploid cells. A parallel study of viral and karyologic parameters. Ann Med Exp Biol Fenn. 1966, 44, 242–254. [Google Scholar]

- Kummer JA; Kamp AM; Tadema TM; Vos W; Meijer CJ; Hack CE. Localization and identification of granzymes A and B-expressing cells in normal human lymphoid tissue and peripheral blood. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995, 100, 1, 164-172.

- Helenius A; Morein B; Fries E; Simons K; Robinson P; Schirrmacher V; Terhorst C; Strominger JL. Human (HLA-A and HLA-B) and murine (H-2K and H-2D) histocompatibility antigens are cell surface receptors for Semliki Forest virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978, 75, 8, 3846-3850.

- Garcia-Sanz JA; Plaetinck G; Velotti F; Masson D; Tschopp J; MacDonald HR; Nabholz M. Perforin is present only in normal activated Lyt2+ T lymphocytes and not in L3T4+ cells, but the serine protease granzyme A is made by both subsets. EMBO J. 1987, 6, 4, 933-938.

- Musha N; Yoshida Y; Sugahara S; Yamagiwa S; Koya T; Watanabe H; Hatakeyama K; Abo T. Expansion of CD56+ NK T and gamma delta T cells from cord blood of human neonates. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998, 113, 2, 220-228.

- Mathews, CK. Effects of thymidine analogs upon growth control in cultured hormone-dependent ray ovary cells. Exp Cell Res. 1975, 92, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakata M; Smyth MJ; Norihisa Y; Kawasaki A; Shinkai Y; Okumura K; Yagita H. Constitutive expression of pore-forming protein in peripheral blood gamma/delta T cells: implication for their cytotoxic role in vivo. J Exp Med. 1990, 172, 6, 1877-1880.

- Rutella S; Rumi C; Lucia MB; Etuk B; Cauda R; Leone G. Flow cytometric detection of perforin in normal human lymphocyte subpopulations defined by expression of activation/differentiation antigens. Immunol Lett. 1998, 60, 1, 51-55.

- Kawamura T; Kawachi Y; Moroda T; Weerasinghe A; Iiai T; Seki S; Tazawa Y; Takada G; Abo T. Cytotoxic activity against tumour cells mediated by intermediate TCR cells in the liver and spleen. Immunology. 1996, 1, 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Berthou C; Legros-Maida S; Soulie A; Wargnier A; Guillet J; Rabian C; Gluckman E; Sasportes M. Cord blood T lymphocytes lack constitutive perforin expression in contrast to adult peripheral blood T lymphocytes. Blood. 1995, 85, 1540–1546. [Google Scholar]

- Rukavina D; Laskarin G; Rubesa G; Strbo N; Bedenicki I; Manestar D; Glavas M; Christmas SE; Podack ER. Age-related decline of perforin expression in human cytotoxic T lymphocytes and natural killer cells. Blood. 1998, 92, 7, 2410-2420.

- Tabata Y; Villanueva J; Lee SM; Zhang K; Kanegane H; Miyawaki T; Sumegi J; Filipovich AH. Rapid detection of intracellular SH2D1A protein in cytotoxic lymphocytes from patients with X-linked lymphoproliferative disease and their family members. Blood. 2005, 105, 8, 3066-3071.

- Marsh RA; Madden L; Kitchen BJ; Mody R; McClimon B; Jordan MB; Bleesing JJ; Zhang K; Filipovich AH. XIAP deficiency: a unique primary immunodeficiency best classified as X-linked familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and not as X-linked lymphoproliferative disease. Blood. 2010, 116, 7, 1079-1082.

- Abdalgani M; Filipovich AH; Choo S; Zhang K; Gifford C; Villanueva J; Bleesing JJ; Marsh RA. Accuracy of flow cytometric perforin screening for detecting patients with FHL due to PRF1 mutations. Blood. 2015, 15, 1858–1860. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin TS; Zhang K; Gifford C; Lane A; Choo S; Bleesing JJ; Marsh RA. Perforin and CD107a testing is superior to NK cell function testing for screening patients for genetic HLH. Blood. 2017, 129, 2993–2999. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Age/ sex |

Diagnose | Treatment | OS (months) | Prognosis |

| 1 | 66/M | LHLH | CHOP | 2.3 | Died |

| 2 | 65/M | LHLH |

High-dose corticosteroid & IVIG +antiviral therapy +3 cycle MINE |

39.7 | Died |

| 3 | 27/M | LHLH | HLH-2004 + 3 cycle MINE + 3 cycle CHOPE |

93.0 | Survival |

| 4 | 59/M | LHLH | 3 cycle MINE + splenic radiotherapy + 3cycle DHAP | 39.9 | Died |

| 5 | 45/M | LHLH | HLH-2004 + 2 cycle MINE + 1 cycle GDP + 1 cycle HyperCVAD-A + 1 cycle CHOP | 6.0 | Died |

| 6 | 30/F | LHLH | HLH-2004+3 cycle MINE + 1 cycle DHAP+ 1 cycle HyperCVAD-A | 17.1 | Died |

| 7 | 60/M | LHLH | SMILE | 0.9 | Died |

| 8 | 41/F | LHLH | High-dose corticosteroid & IVIG +HLH-2004+12 cycle L-GemOx | 92.3 | Survival |

| 9 | 60/M | LHLH | 4 cycle CHOP+ 4 cycle GDP | 7.8 | Died |

| 10 | 59/M | LHLH | High-dose corticosteroid & IVIG +HLH-2004+ 8 cycle MINE |

98.0 | Survival |

| 11 | 37/M | LHLH | High-dose corticosteroid & IVIG +2 cycle MINE+ L-GemOx+ 3 cycle GemOx |

7.3 | Died |

| 12 | 39/M | IHLH (EBV, Fungus) |

High-dose corticosteroid & IVIG + HLH-2004+ Anti-fungal theraphy |

96.0 | Survival |

| 13 | 57/M | IHLH (Fungus) | Anti-fungal therapy+ anti-infectious therapy+ corticosteroid | 93.0 | Survival |

| 14 | 59/M | IHLH (pneumonia) | Supportive treatment | NA | Lost to follow-up |

| 15 | 29/F | IHLH (EBV) |

Corticosteroid +antiviral therapy + supportive treatment |

2.9 | Died |

| 16 | 52/F | IHLH (sepsis) |

Anti-infectious therapy+ supportive treatment | 94.1 | Survival |

| 17 | 48/M | IHLH | High-dose corticosteroid & IVIG+ anti-infectious therapy | 104.0 | Survival |

| 18 | 58/F | AHLH | COP+ High-dose corticosteroid & IVIG&CTX | 3.1 | Died |

| 19 | 46/M | AHLH | COP+ supportive treatment | 12.0 | Died |

| Flow cytometric parameters | Normal (N=10) |

ND-sHLH (N=19) |

Remission-sHLH (N=6) |

| CD8+ T% | 1.21(0.46~16.44) | 5.39(1.35~21.73) | 1.43(0.83~2.07) |

| NK% | 17.62(10.24~24.66) | 9.54(5.84~12.79) | 7.88(5.11~9.40) |

| CD56+T% | 19.10(16.60~22.68) | 23.28(15.12~27.67) | 32.64(20.73~38.81) |

| Perforin (CD8+T) % | 17.38(6.88~34.76) | 30.99(17.09~55.23) | 37.76(32.89~53.19) |

| Perforin (NK) % | 56.20(47.58~73.34) | 66.79(45.89~74.92) | 48.97(27.58~76.64) |

| Perforin (CD56+T) % | 8.39(3.52~25.01) | 31.60(19.14~66.64) | 20.54(12.96~31.19) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).