1. Introduction

Metal additive manufacturing [

1] is a manufacturing process based on three-dimensional models, using lasers, electron beams, electric arcs, and other heat sources to melt metal powders, and build parts through the layer-by-layer accumulation of materials. Metal additive manufacturing has the advantages of free forming, customization, and the ability to directly form complex parts with unique shapes [

2,

3], which is challenging to fabricate the parts via traditional technologies. Metal additive manufacturing is currently widely used in industrial applications such as aerospace [

4], biomedical equipment [

5], and automotive manufacturing [

6]. Among these methods of metal additive manufacturing, selective laser melting technology has emerged as a research focus [

7,

8]. During SLM process, metal powders are fully melted to fabricate dense parts due to the complete melting and solidification of powders. Fang Ruirui et al. [

9] successfully fabricate corrax stainless steel with a relative density of 99.52% and investigate the effect of process parameters on the mechanical properties of SLM samples. The samples exhibit the best mechanical properties with the highest microhardness (374.2HV), yield strength (946MPa), ultimate tensile strength (1084MPa) and elongation (17.64%) under process parameters of P = 190 W, V = 1.1 m·s−1.

Due to the excellent mechanical properties and corrrosion resistance, 316L stainless steel is widely used in industries such as marine [

10], aerospace [

11] and biomedical equipment [

12]. However, connecting various parts through welding may induce intergranular corrosion [

13]. Therefore, SLM technology have been developed to fabricate 316L stainless steel due to the good formability, low carbon content and high laser absorption of its spherical powder. Several studies [

14,

15,

16] have focused on the 316L austenitic stainless steel fabricated via SLM with better mechanical properties, compared with those of conventionally manufactured 316L. Bakhtiarian M et al. [

17] reported the density, microhardness and mechanical properties of SLM 316L and optimize process parameters with Taguchi optimization method. It was found that 316L with impressive tensile strengths (649MPa), yield strengths (409MPa), and elongation (42%) was obtained via a laser power of 180 W, a scanning speed of 1200 mm/s, and a layer thickness of 0.03 mm.

Microstructure determines mechanical properties, it is found that the improvement of mechanical properties is mainly due to finer columnar crystals and cellular crystals caused by the large temperature gradients and rapid solidification characteristic at high cooling rates [

18] of SLM technology. However, the SLM processes with large temperature, and rapid melting and solidification often induced a variety of internal and surface defects [

19,

20,

21] such as inhomogeneous microstructure, porosity, microcracks, and residual stresses. Nowadays, several scholars [

22,

23,

24] studied that process parameter modification, surface modification technologies and heat treatment are introducted to reduce the residual stresses and other surface defects. Heat treatment is more convenient compared with surface modification technologies, which lead to the surface plastic deformation of specimens. Zhou et al. [

25] investigated the microstructural evolution of SLM 316L and the effect of heat treatment on the corrosion resistance of SLM 316L. The results revealed that the elimination of the high-density dislocation of the cellular substructures and the molten pool boundaries induced uniform distribution of nano inclusions with heat treatment (950℃), which enhances the corrosion resistance. The study conducted by Riabov et al. [

26] delved into the effect of annealing temperatures ranging from 400 ℃ to 1200 ℃ on the tensile properties. The strain accumulation in the cell boundaries was increased after applying a strain of 20% and the cell boundaries provide a dislocation pinning effect. In addition, it is inevitable that SLM 316L specimens have anisotropy in microstructure and other properties [

27]. Zhou et al. [

28] investigated the anisotropy of microstructure and mechanical properties. The results show that the SLM 316L possessed excellent strength and ductility, but the anisotropy of the mechanical properties of the transverse and longitudinal specimens was evident, which is caused by the geometric relationship between the boundary of the molten pool and the tensile force. Nevertheless, due to the relatively poor wear resistance of 316L stainless steel, there is a lack of systematic research on the impact of heat treatment in improving anisotropy of the wear resistance of SLM 316L.

In this paper, the effects of different heat treatment processes on the microstructure, microhardness, and wear resistance of SLM 316L stainless steel was studied. SLM 316L fabricated via optimized process parameters is heat treated with solution treatment (1050℃×2h), aging treatment (850℃×4h) and solution treatment (1050℃×2h)+aging treatment (850℃×4h). In addition, the anisotropy of microhardness, and wear resistance of specimens with heat treatment are analyzed in detail. This provides a theoretical basis for exploring the optimal heat treatment system to comprehensively improve the performance of 316L stainless steel. This is of great significance for improving the microhardness and wear resistance of SLM 316L stainless steel in various building directions.

2. Materials and Methods

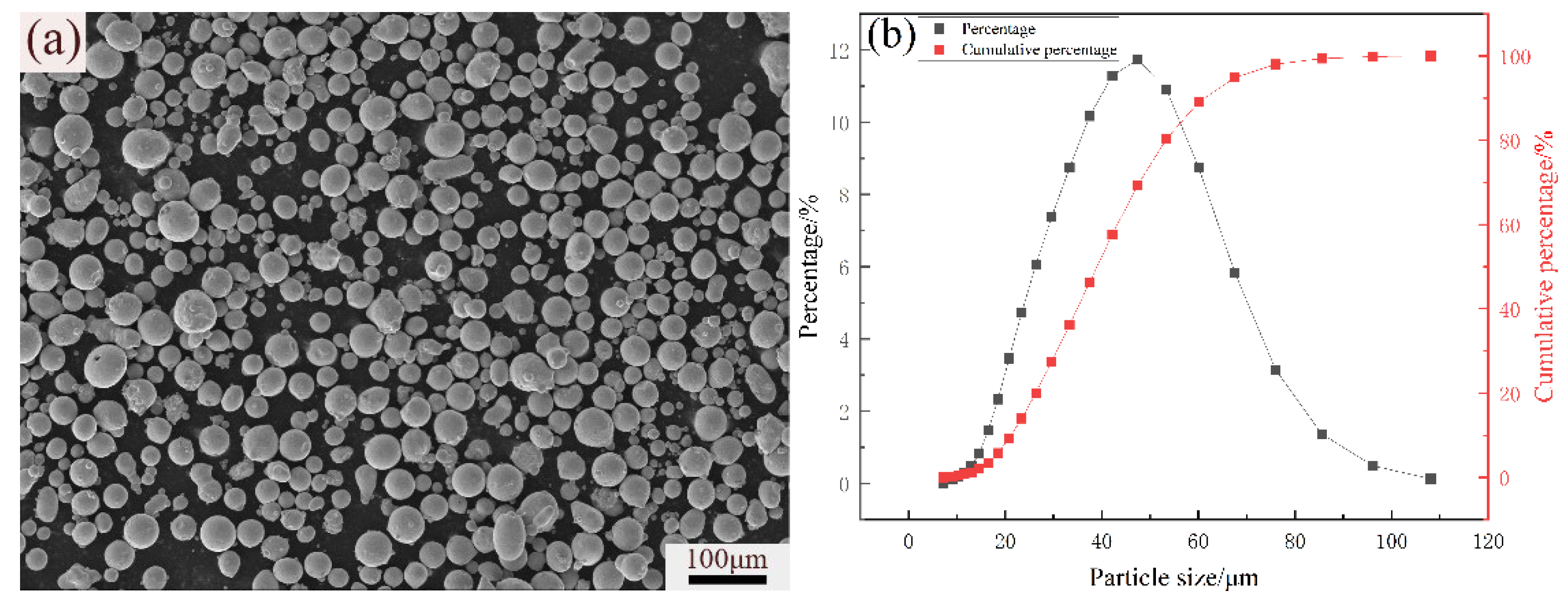

The morphology and particle size distribution of 316L powders user in this study were shown in

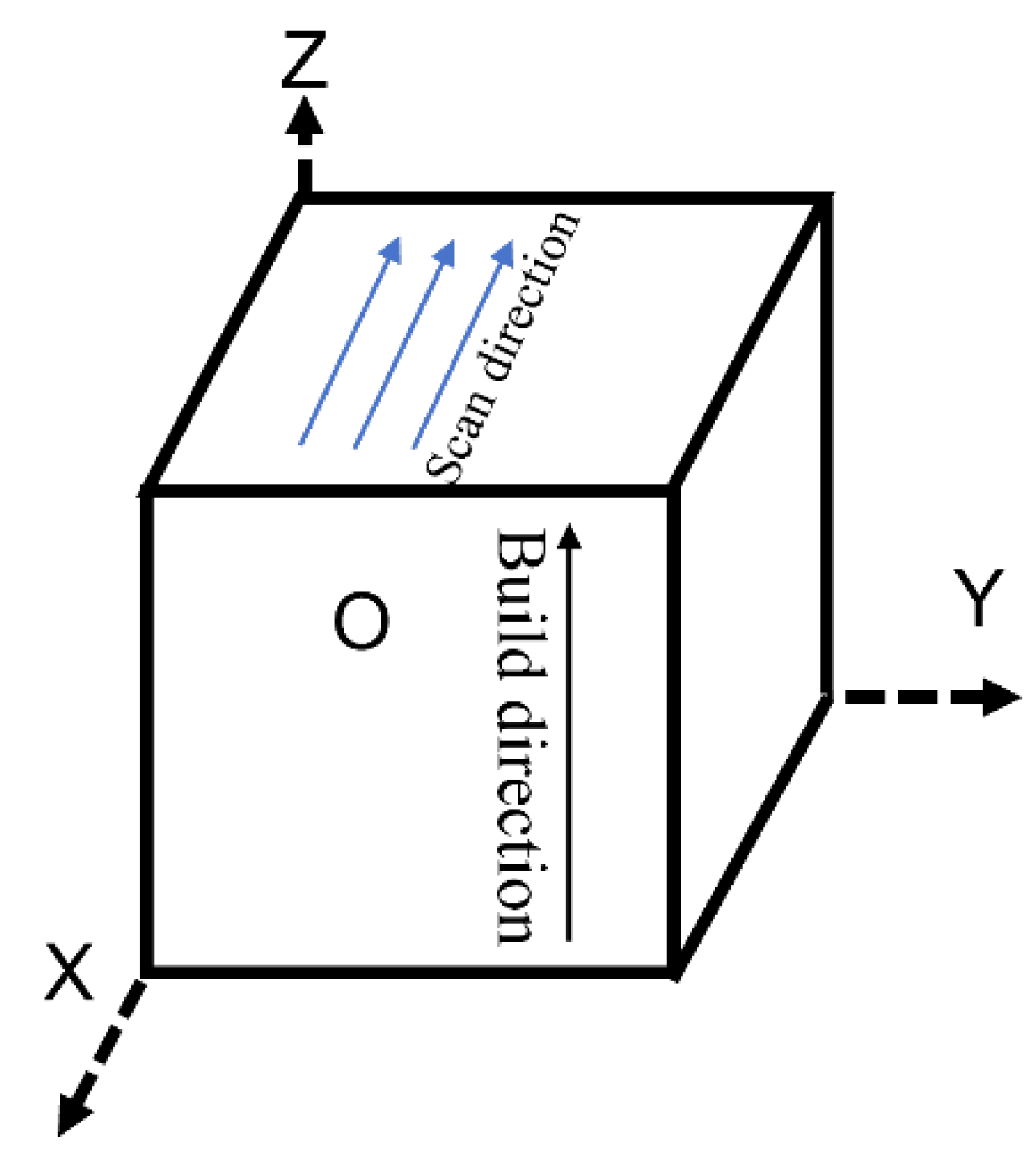

Figure 1. The powders with an average particle size of 40μm were spherical and exhibit a normal distribution, indicating good powder flowability, which is conducive to melting and forming. The powders and substrate were dried at 120℃ for 2h before SLM. The 316L stainless steel was fabricated via BLT-S210 metal printer (BLT, China) equipped with 500W fiber laser and wavelength of 1080nm. The SLM specimens with dimensions of 10mm×10mm×10mm was fabricated with a laser power of 150W, scanning speed of 800mm/s, hatch spacing of 80μm, and layer thickness of 20μm. The forming chamber was protected via argon and oxygen was reduced below 30ppm during the SLM process. The SLM specimens were prepared via rotating 67° layer by layer according to scanning strategy as shown in

Figure 2. The SLM specimens for heat treatments were applied in vacuum tubes as shown in

Table 1. The chemical composition of 316L stainless steel powder and SLM specimens shown in

Table 2 were analyzed. The results indicated that the chemical composition was hardly changed via SLM process.

Density is one of the important parameters for evaluating the quality of additively manufactured specimens. The Archimedes’ method is used to test the volume density of the specimens. First, the mass of the specimen (M1) was measured in air using a balance, then, a thin layer of vaseline was applied on the surface of the specimen and the weigh of SLM specimen in water (M2) was measured. The volume density of the specimen (ρt) can be calculated via the following formula:

Where ρw is the density of water, ρL is the theoretical density of 316L stainless steel. The planar density of the specimen was measured via metallographic method, and the polished and uncorroded specimen was photographed via an optical microscope (OM). The proportion of pore area (ρk) in the area was calculated in Image Pro Plus software, and the planar density of the specimen was obtained via the formula: ρm=1-ρk.

The XOY plane parallel to the SLM direction and the XOZ surface perpendicular to the SLM direction of each group of specimens were grinded and polished to fabricate metallographic specimens. Then the polished specimens were etched in aqua regia (VHCl: VHNO3=3:1) for 15s. The phases of SLM specimens were analyzed via XRD with Cu-Kα radiation in the 2θ range of 35° to 90°. Microstructural characterization of SLM 316L was conducted via scanning electron microscopy (SEM) at 20kV. Microhardness testing was performed via MHV-1000 Vickers hardness tester with a load of 0.2kgf and a duration time of 15s. Five points are taken for test and the average value is taken as the final microhardness value. Friction and wear tests were carried out at room temperature using a HT-1000 with a load of 10N and a rotation radius of 3mm. GCr15 steel ball is sliding against the specimens at 1000rpm for 30min. The mass change of the specimen before and after wear test were weighed to calculate the wear loss. The friction coefficient and the wear loss of specimen was quantitatively analyzed the wear resistance of specimen. To further investigating the wear resistance of specimen, 3D morphologies of wear track were conducted using VHX-X1F ultra depth of field microscope.

3. Results

3.1. Density

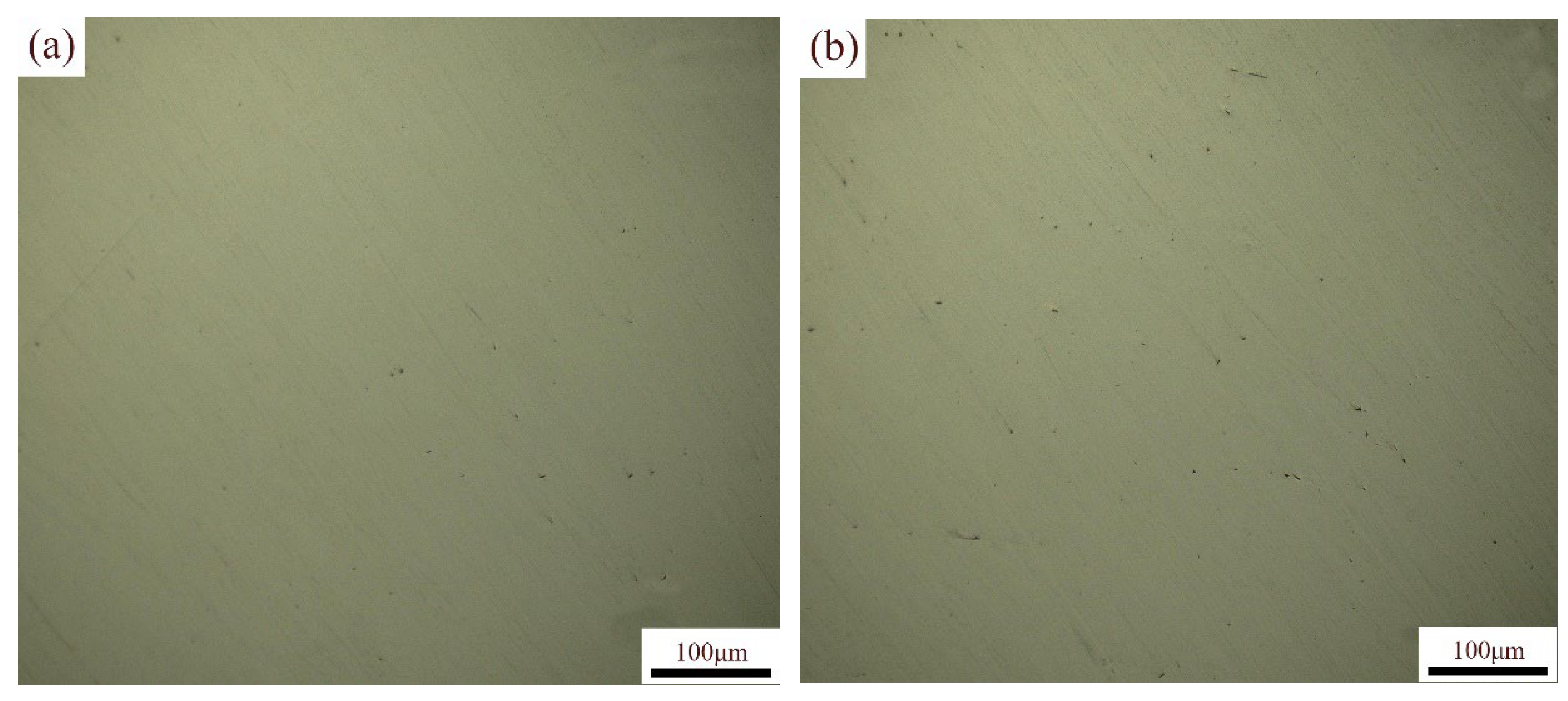

Figure 3a,b show the OM of XOY plane and XOZ plane, and the planar density of specimen was calculated via the pores in the images. As shown in

Table 3, the planar densities of XOY plane and XOZ plane of specimen are slightly higher than the volume densities. This may be due to the sampling position of the planar density and the difficulty in resolving fine pores with a microscope. In addition, planar density of the XOY plane is slightly higher than that of the XOZ plane. The volume densities of specimens a-d measured via the Archimedes’ method are above 99%, indicating that the SLM 316L stainless steel specimens are dense [

29]. After heat treatment, the volume densities of specimens decreased, and the volume density of specimen with solution treatment+aging treatment is the highest.

3.2. Microstructure Characterization

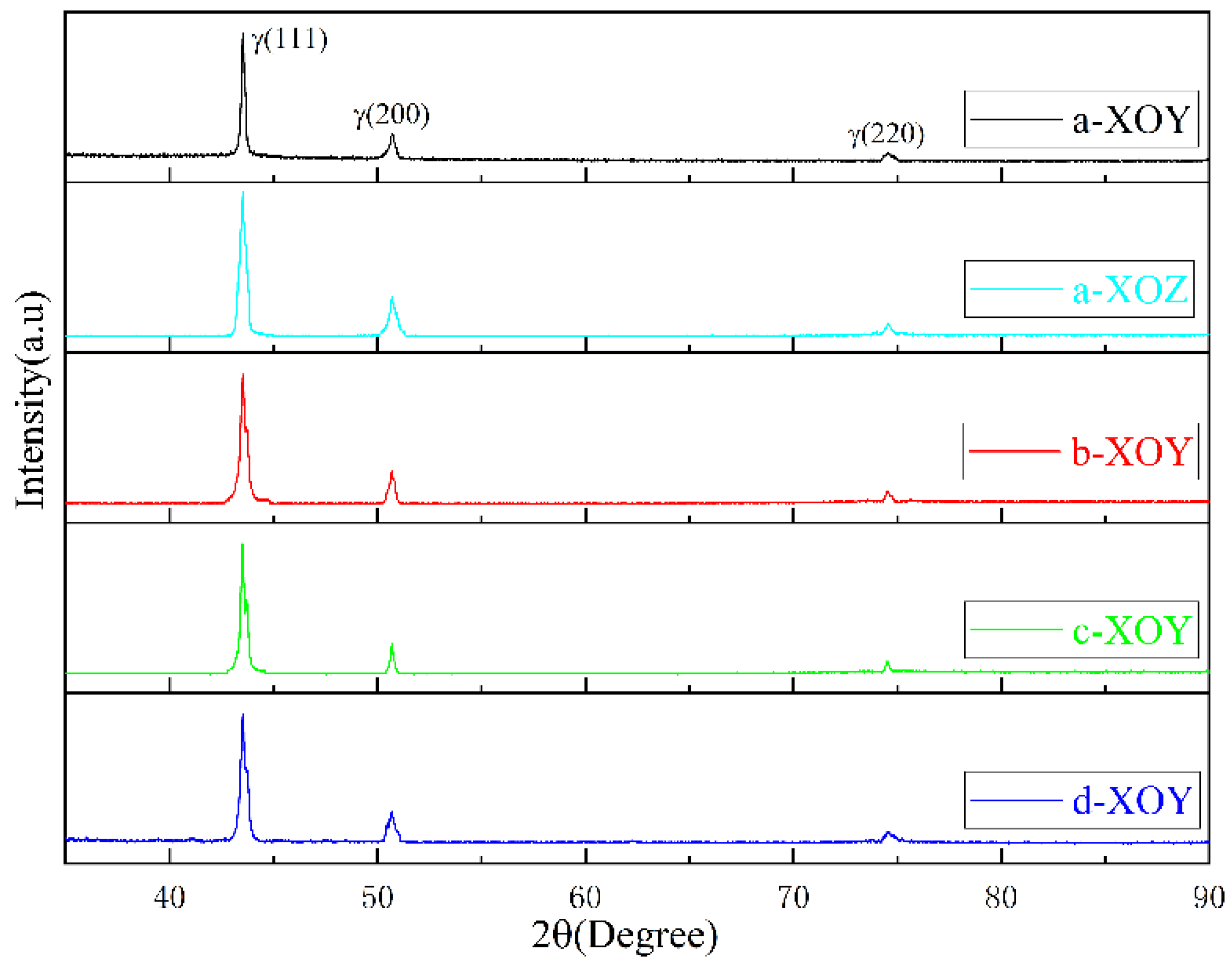

Figure 4 shows the XRD pattern of specimens a-d. The results of XRD analysis of specimen a in

Figure 4 reveals that the presence of (111), (200), and (220) austenite phase, exhibiting FCC structure. XRD analysis of XOY and XOZ planes show that no significant peak shifts are observed. The (111) peak intensity of the XOY plane is slightly lower than that of the XOZ plane, and the peak intensities of (200) and (220) are relatively close, indicating that the 316L stainless steel prepared by SLM exhibits anisotropy in grain orientation, with different degrees of anisotropy between the XOY and XOZ planes. After different heat treatment processes, the XRD pattern of the XOY planes of SLM specimens b-d are uniform.

Table 2 shows that the types and contents of elements in each group of specimens are consistent and shows no significant changes. It is demonstrated that no new phases are generated during heat treatment process, indicating that SLM 316L has good thermal stability.

Figure 5 depicts the OM and SEM images of XOY plane and XOZ plane of specimen a. From the OM images of the XOY and XOZ planes in

Figure 5a–c, it can be observed that the specimens exhibit different microstructures in different SLM directions. The microstructure on the XOY plane in

Figure 5b shows intersecting melt pools with an intersection angle of approximately 67°, which is consistent with the rotation angle of the laser scanning between layers. The microstructure on the XOZ plane, which is perpendicular to the SLM direction, appears as a fish-scale pattern composed of individual micro-melt pools, with the curves in

Figure 5c,d representing the boundaries of the melt pools. The microstructure of the SLM specimen exhibits anisotropy in different SLM directions. From

Figure 5c,d, it can be seen that the spacing between each SLM layer is about 20μm, which is consistent with the powder layer thickness.

Figure 5d–h display the SEM images of the XOZ plane of specimen a. From

Figure 5d, it is evident that the boundaries between adjacent melt pools are obvious, and the melt pool is composed of columnar crystals with varying growth directions and cellular crystals with different sizes. The non-uniform energy distribution during the SLM process leads to differences in temperature gradients, resulting in different microstructures within the melt pools. In

Figure 5e, the triangular area represents the melt pool overlap region, where cellular crystals grow and coarsen due to the remelting effect of the laser, and the grain size is larger compared to the rapidly solidified cellular crystals in the melt track. The melt pool boundaries in

Figure 5e exhibit columnar crystals that grow in a directionally oriented manner due to differences in temperature gradients; and the columnar crystals on the XOZ plane appear as cellular structures on the XOY plane [

30].

Figure 5g shows numerous nanoparticles attached to the surface of the cellular crystals, and EDS analysis reveals that these nanoparticles contain high contents of Si and O elements, as shown in

Figure 5h, which is consistent with the results reported in previous literature [

31,

32,

33], and these nano-oxides are believed to be SiO

2 precipitates.

The OM images of the microstructure of the specimens are shown in

Figure 6. As shown in

Figure 6a, the microstructure of the XOZ plane of specimen a exhibit a fish-scale pattern of melt pools. After solution treatment at 1050°C, the solution temperature reaches the austenitization temperature, the alloy elements were diffused, and the melt pool boundaries and fish-scale melt pools in specimen b disappear. The recrystallization occurs in specimen b, and the cellular structure within the melt pool coarsens, transforming into irregular grains. After aging treatment at 850°C, the melt pool boundaries in specimen c also disappear, and due to limited recrystallization, a part of grains grow, presenting as blocky grains of varying sizes. After solution treatment at 1050°C and aging treatment at 850°C, further recrystallization occurs, and the grains coarsen further.

3.3. Microhardness

Figure 7 shows the microhardness of the XOY and XOZ planes of specimen a-d. The microhardness of the XOY and XOZ planes of specimen a is 298.5HV and 291.3HV, respectively. Comparative analysis of the microhardness of specimens a-d on the XOY and XOZ planes reveals that the microhardness of the XOY plane is slightly higher than that of the XOZ plane, but the difference is not significant. This is mainly related to the anisotropy in the microstructure of the specimens on the XOY and XOZ planes. The microhardness values are affected via grain size and porosity. Due to the higher number of cellular crystals on the XOY plane, smaller grain size, and higher density, the microhardness of the XOY plane is higher. After heat treatment, the microhardness of specimens b-d on both the XOY and XOZ planes slightly decreases compared to specimen a, and the decrease of specimen d is lowest. After heat treatment, the microhardness decreases, which is related to grain coarsening and the disappearance of melt pool boundaries. According to the Hall-Petch formula [

34], the finer the grains in dense metal materials, the greater the resistance to dislocation slip along grain boundaries, and the higher the microhardness. Additionally, the density decreases after heat treatment, leading to a decrease in microhardness for specimens b-d.

3.4. Friction and Wear

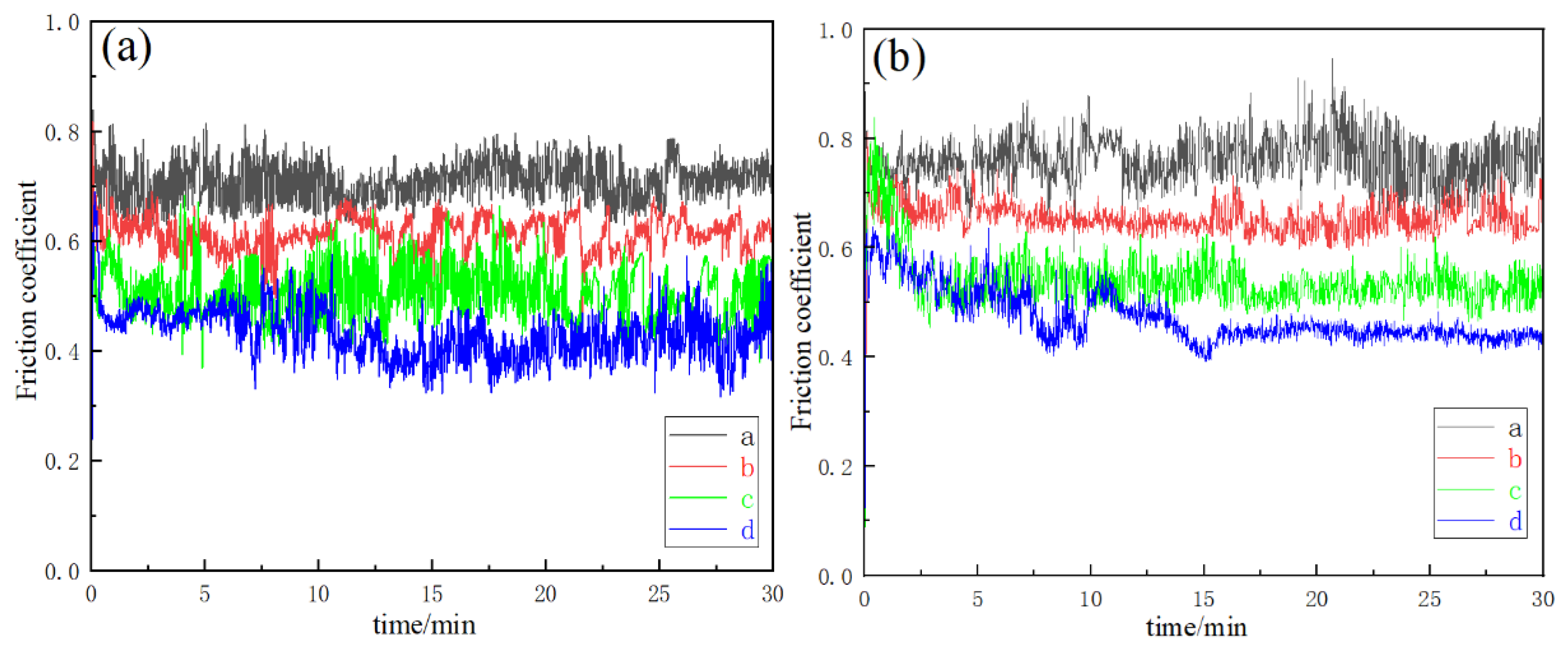

At room temperature, the friction coefficient variation of specimens a-d on the XOY and XOZ planes under a 10N load and 1000r/min for 30 min is shown in

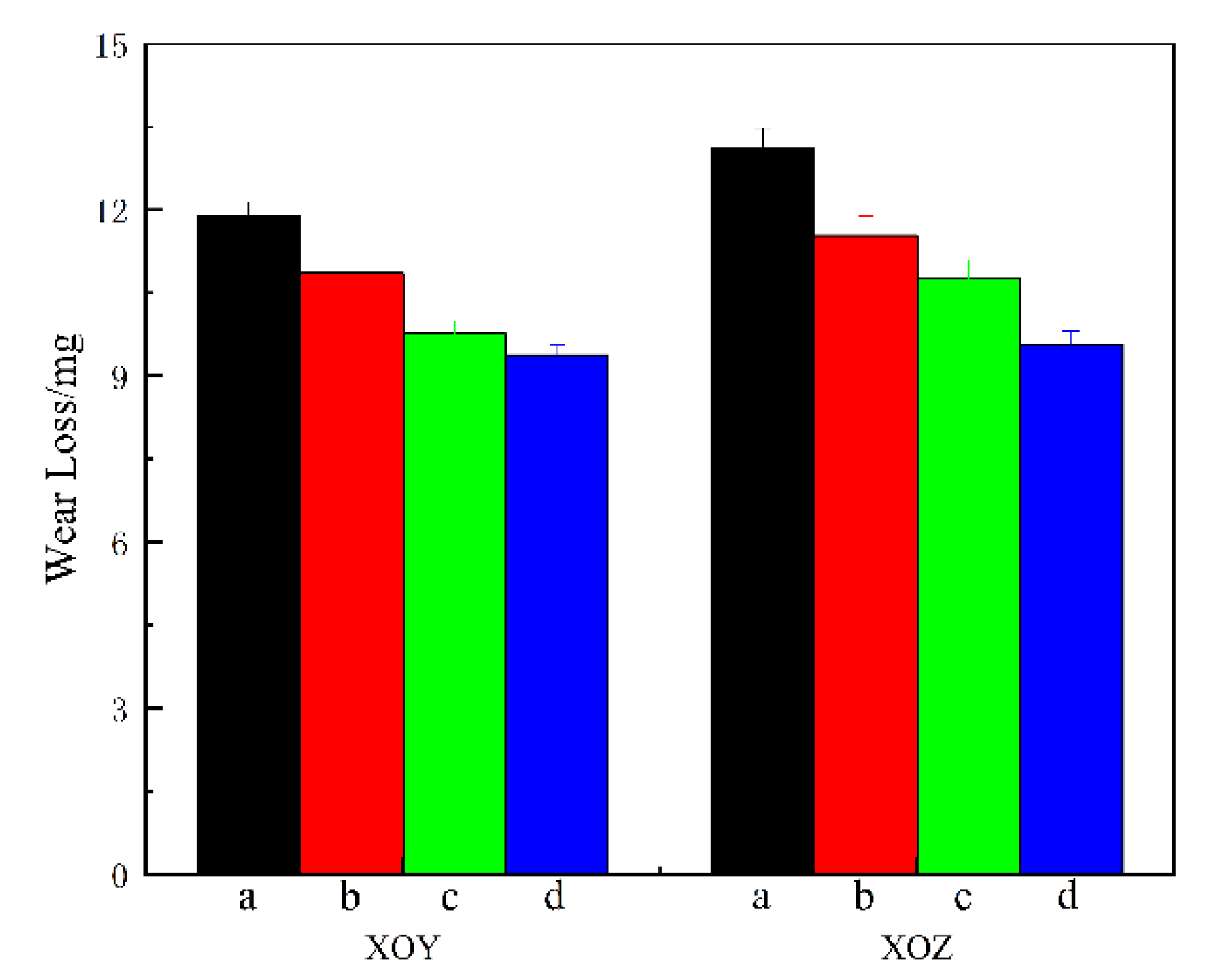

Figure 8, and the wear loss is shown in

Figure 9. In the initial stage of friction, the friction coefficient rises sharply due to the cold welding effect between the grinding ball and the friction surface. As the cold welding points tear and wear debris is generated and expelled, the friction coefficient stabilizes. Comparative analysis of the XOY and XOZ planes of each specimen in

Figure 8a,b reveals that the friction coefficient of the XOY plane is slightly lower than that of the XOZ plane, indicating that the XOY plane has better anti-friction performance than the XOZ plane. The friction coefficients of the specimens b-d are reduced, indicating better anti-friction properties after heat treatment.

Figure 9 shows that the wear loss of the XOY plane is less than that of the XOZ plane for each specimen, indicating that the XOY plane has better wear resistance than the XOZ plane. After heat treatment, the wear loss of the specimen is reduced, and the wear resistance is improved. Generally, the higher the hardness of a material, the better its ability to resist plastic deformation and the better its wear resistance [

35]. However, the SLM 316 stainless steel without heat treatment has a higher hardness but worse wear resistance, which may be due to its greater brittleness [

36], making it more prone to crack formation and surface spalling under repeated friction loads.

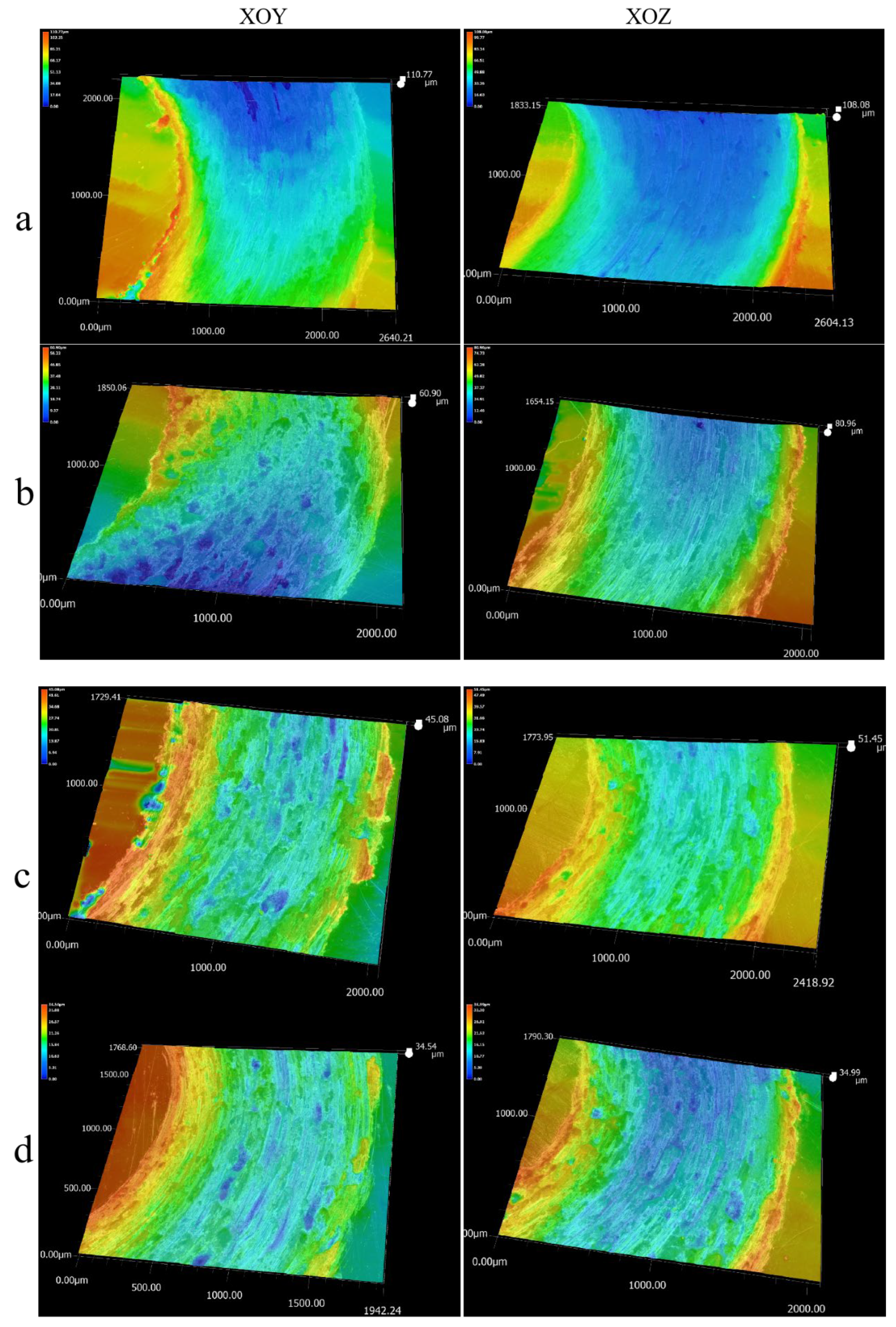

To further analyze the wear characteristics of the samples, a super-depth-of-field microscope was used to characterize the 3D morphologies of wear track, as shown in

Figure 10. The 3D morphologies of wear track on the XOY and XOZ planes revealed that the wear tracks on the XOY plane were shallower and narrower than those on the XOZ plane, further proving that the wear resistance of the XOY plane is better than that of the XOZ plane. After heat treatment, the wear track depth became shallower and the width narrower, indicating better wear resistance, The wear resistance of sample was the best. This may be due to the grain coarsening caused by heat treatment; although the microhardness is reduced, the crack resistance is enhanced during the cyclic friction and wear process, leading to the reduce of wear loss.

Figure 10a,b show that the wear surface of sample a exhibited continuous furrows and deeper wear pits. During continuous sliding, the abrasive particles cut the wear surface. Due to the relatively higher brittleness of sample a, surface spalling occurred, and the sample a mainly exhibited abrasive wear and fatigue wear. After heat treatment, in addition to furrows, smooth areas appear on the wear surface, indicating that the sample mainly exhibited abrasive wear and adhesive wear.

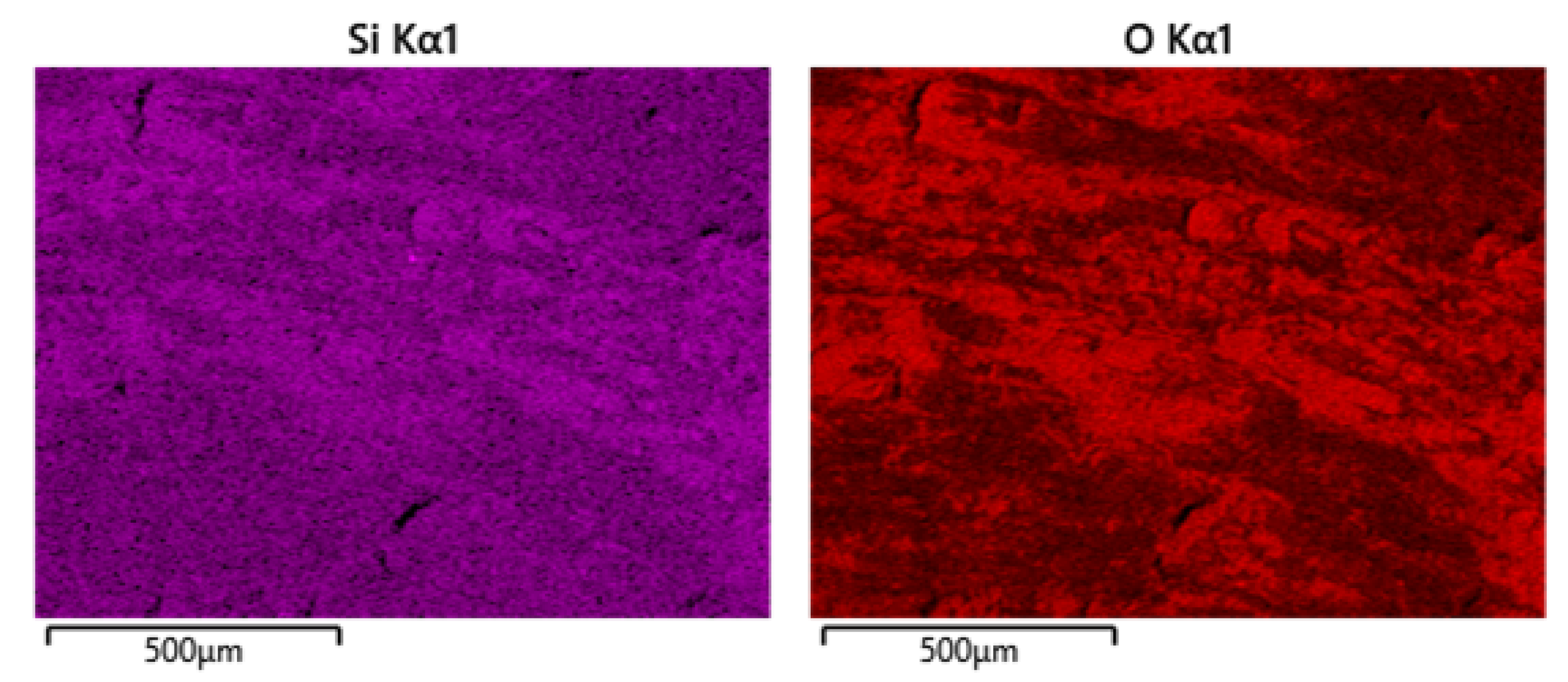

Figure 11 shows the EDS spectrum of the wear surface of the heat-treated samples, where a significant enrichment of Si-O is observed. After heat treatment, nanoscale SiO

2 precipitates exude and coarsen, distributing dispersedly within the samples, playing a role in precipitation strengthening and dispersion strengthening, enhancing the resistance to shear and furrowing [

37].

4. Conclusions

In this work, the effect of different heat treatments and anisotropy on the microstructure, density, microhardness and wear resistance of SLM 316L specimen has been investigated, and the microstructure of SLM 316L specimen have been analyzed.

1. The planar densities of XOY plane and XOZ plane of SLM 316 and specimens with heat treatment are higher than 99%. The volume density of specimen with solution treatment+aging treatment is the highest.

2. The XRD analysis of all specimen present (111), (200), and (220) austenite phase, the XOY plane and XOZ plane exhibit anisotropy in grain orientation. SLM 316L has good thermal stability and heat treatment will not induce phase transition. Microstructure of SLM 316L specimen exhibits intersecting melt pools on the XOY plane and fish-scale-like melt pools on the XOZ plane. The melt pools are composed of columnar crystals and cellular crystals due to the rapid solidification characteristic. With heat treatment, melt pool boundaries are eliminated and microstructure are coarsening.

3. The microhardness of the XOY plane is slightly higher than that of the XOZ plane. Microhardness of specimens with heat treatments decrease due to the coarsen of microstructure, the decrease of specimen with solution+aging treatment is lowest. The wear resistance of the XOY plane is better than that of XOZ plane, and the specimen with solution+aging treatment is the best owing to the enhancement of crack resistance, and precipitation strengthening and dispersion strengthening of nano SiO2 precipitates.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S., Q.W., J.W., H.W., X.W., H.Z., Y.A., Y.L. and L.M.; Methodology, M.S., Q.W., J.W., H.W., X.W., H.Z., Y.A., Y.L. and L.M.; Validation, M.S.; Data curation, M.S.; Writing—original draft, M.S.; Writing—review & editing, M.S. and J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51965053). Research business expenses in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. First-Class Discipline Research Special Project (YLXKZX-NKD-042).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dadkhah, M.; Mosallanejad, M.H.; Iuliano, L.; Saboori, A. A Comprehensive Overview on the Latest Progress in the Additive Manufacturing of Metal Matrix Composites: Potential, Challenges, and Feasible Solutions. Acta Met. Sin. (English Lett. 2021, 34, 1173–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazyar, A. , Mobin K. , Ehsan T. Adaptive Model-based Optimization for Fusion-based Metal Additive Manufacturing (directed energy deposition). J. Manuf. Process., 2023, 108, 588–595. [Google Scholar]

- Song, W. , Yang J. , Liang J., et al. A New Approach to Design Advanced Superalloys for Additive Manufacturing. Addit. Manuf., 2024, 84, 104098. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy M.S., Christopher A.K., Nikolai A.Z., et al. A 3D Printable Alloy Designed for Extreme Environments. Nature, 2023, 617(7961), 513-51.

- Ataee, A.; Li, Y.; Wen, C. A Comparative Study on the Nanoindentation Behavior, Wear Resistance and in Vitro Biocompatibility of SLM Manufactured CP–Ti and EBM Manufactured Ti64 Gyroid Scaffolds. Acta. Biomater. 2019, 97, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, T.D.; Kashani, A.; Imbalzano, G.; Nguyen, K.T.Q.; Hui, D. Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing): A Review of Materials, Methods, Applications and Challenges. Compos. Part B Eng. 2018, 143, 172–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andac, O.; Eda, A.; Arcan, F.D. Selective Laser Melting of Nano-TiN Reinforced 17-4 PH Stainless Steel: Densification, Microstructure and Mechanical Properties. Mater. Sci. & Eng. A, 2021, 836, 142574.

- Ji P.C., Wang Z.H., Mu Y.K., et al. Microstructural Evolution of (FeCoNi)85.84Al7.07Ti7.09 High-entropy Alloy Fabricated by an Optimized Selective Laser Melting Process. Mater. & Design, 2022, 224, 111326.

- Fang, R.R.; Deng, N.N.; Zhang, H.B.; et al. Effect of Selective Laser Melting Process Parameters on the Microstructure and Properties of a Precipitation Hardening Stainless Steel. Mater. & Design, 2021, 212, 110265. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, T.A.; Escobar, J.; Shen, J.; Duarte, V.R.; Ribamar, G.; Avila, J.A.; Maawad, E.; Schell, N.; Santos, T.G.; Oliveira, J. Effect of heat treatments on 316 stainless steel parts fabricated by wire and arc additive manufacturing : Microstructure and synchrotron X-ray diffraction analysis. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obadele, B.A.; Adesina, O.S.; Oladijo, O.P.; Ogunmuyiwa, E.N. Fabrication of functionally graded 316L austenitic and 2205 duplex stainless steels by spark plasma sintering. J. Alloy. Comp 2020, 849, 156697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katta, P.P.; Nalliyan, R. Corrosion resistance with self-healing behavior and biocompatibility of Ce incorporated niobium oxide coated 316L SS for orthopedic applications. Surf. Coatings Technol. 2019, 375, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C.; Martín, F.; de Tiedra, P.; Cambronero, L.G. Pitting corrosion behaviour of PM austenitic stainless steels sintered in nitrogen–hydrogen atmosphere. Corros. Sci. 2007, 49, 1718–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Jayaraj, R.; Suryawanshi, J.; Satwik, U.; McKinnell, J.; Ramamurty, U. Fatigue strength of additively manufactured 316L austenitic stainless steel. Acta Mater. 2020, 199, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabarzadeh, S.; Ghasemi-Ghalebahman, A.; Najibi, A. Investigation into microstructure, mechanical properties, and compressive failure of functionally graded porous cylinders fabricated by SLM. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhradeep, D.; Vishal, Y.; Bandar, A.; et al. Additive Manufacturing of Graphene Reinforced 316L Stainless Steel Composites with Tailored Microstructure and Mechanical Properties. Mater. Chem. & Phys., 2023, 303, 127826. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtiarian, M.; Omidvar, H.; Mashhuriazar, A.; Sajuri, Z.; Gur, C.H. The effects of SLM process parameters on the relative density and hardness of austenitic stainless steel 316L. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 1616–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdali, A.; Nedjad, S.H.; Zargari, H.H.; Saboori, A.; Yildiz, M. Predictive tools for the cooling rate-dependent microstructure evolution of AISI 316L stainless steel in additive manufacturing. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 5530–5538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.L.; Roehling, J.D.; Strantza, M.; et al. Residual Stress Analysis of in Situ Surface Layer Heating Effects on Laser Powder Bed Ffusion of 316L Stainless Steel. Addit. Manuf., 2021, 37, 102252. [Google Scholar]

- Chepkoech, M.; Owolabi, G.; Warner, G. Investigation of Microstructures and Tensile Properties of 316L Stainless Steel Fabricated via Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Materials 2024, 17, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog D., Seyda V., Wycisk E., et al. Additive Manufacturing of Metals. Acta. Mater., 2016, 117, 371-392.

- Maleki, E.; Unal, O.; Doubrava, M.; et al. Application of Impact-based and Laser-based Surface Severe Plastic Deformation Methods on Additively Manufactured 316L: Microstructure, Tensile and Fatigue Behaviors. Mater. Sci. & Eng. A, 2024, 916, 147360. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, Q.; Thomas, S.; Birbilis, N.; Cizek, P.; Hodgson, P.D.; Fabijanic, D. The effect of post-processing heat treatment on the microstructure, residual stress and mechanical properties of selective laser melted 316L stainless steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Wang, K.S.; Wang, W.; et al. Relationship between Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Friction Stir Processed AISI 316L Steel Produced by Selective Laser Melting. Mater. Charact. 2020, 163, 110283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.S.; Wu, F.Y.; Tang, D.; et al. Effect of Subcritical-temperature Heat Treatment on Corrosion of SLM SS316L with Different Process Parameters. Corros. Sci., 2023, 218, 111214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riabov, D.; Leicht, A.; Ahlström, J.; Hryha, E. Investigation of the strengthening mechanism in 316L stainless steel produced with laser powder bed fusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 822, 141699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güden, M.; Yavaş, H.; Tanrıkulu, A.A.; Taşdemirci, A.; Akın, B.; Enser, S.; Karakuş, A.; Hamat, B.A. Orientation dependent tensile properties of a selective-laser-melt 316L stainless steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 2021, 824, 141808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou B.G., Xu P.W.,Wei L., et al. Microstructure and Anisotropy of the Mechanical Properties of 316L Stainless Steel Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting. Metals, 2021, 11(5), 775-775.

- Li Z., Voisin T., McKeoun J.T., et al. Tensile Properties, Strain Rate Sensitivity, and Activation Volume of Additively Manufactured 3l6L Stainless Steels. Int. J. Plasticity, 2019, 120(1), 395-410.

- Chen Y.F., Wang X.W., Li D., et al. Experimental Characterization and Strengthening Mechanism of Process-structure-property of Selective Laser Melted 316 L. Mater. Charact., 2023, 198, 112753.

- Yan, F.; Xiong, W.; Faierson, E.; Olson, G.B. Characterization of nano-scale oxides in austenitic stainless steel processed by powder bed fusion. Scr. Mater. 2018, 155, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen S., Ma G., Wu G., et al. Strengthening Mechanisms in Selective Laser Melted 316L Stainless Steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A, 2022, 832, 142434.

- Voisin, T.; Forien, J.-B.; Perron, A.; Aubry, S.; Bertin, N.; Samanta, A.; Baker, A.; Wang, Y.M. New insights on cellular structures strengthening mechanisms and thermal stability of an austenitic stainless steel fabricated by laser powder-bed-fusion. Acta Mater. 2021; 203, 116476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, J.A.; Davies, H.M.; Mehmood, S.; Lavery, N.P.; Brown, S.G.R.; Sienz, J. Investigation into the effect of process parameters on microstructural and physical properties of 316L stainless steel parts by selective laser melting. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2015, 76, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemachandra, M.; Thapliyal, S.; Adepu, K. A review on microstructural and tribological performance of additively manufactured parts. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 17139–17161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Y.W., Godfrey A., Liu W. Effect of Heat Treatment on Microstructural Evolution in Additively Manufactured 316L Stainless Steel. Metals, 2023, 13(6), 1062.

- Han Z.Z., Yuan J., Tian P.J., et al. Preparation of Highly Transparent and Wear-resistant SiO2 Coating by Alkali/acid Dual Catalyzed Sol-gel Method. J. Mater. Res., 2023, 38(13), 3316-3323.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).