Introduction

Congenital heart defects are the most common birth defects in humans. Approximately 1% of live-born children have a congenital heart defect. Single ventricle defects are among the most serious congenital heart defects. The incidence of single ventricle defects is approximately 0.2%. [

1] The final common step in the treatment of children with single ventricle defects is the Fontan operation. The Fontan operation makes up approximately 3% of all congenital cardiac operations in American and European congenital cardiac surgery databases. [

2] This palliation has been an overwhelming success. It is estimated that there is a worldwide population of approximately 50,000 to 70,000 patients with a Fontan palliation. [

3] However, Fontan palliation remains imperfect because it inevitably results in fatal complications.

An Imperfect Palliation

Contemporary surgical management of single ventricle congenital heart disease is comprised of a series of palliative procedures which culminate with the Fontan-Kreutzer procedure. This operation, as performed presently, creates a total cavopulmonary connection that results in parallel systemic and pulmonary circulations. It has had several modifications since its initial description in 1971, with 65% surgeons currently performing an extracardiac conduit. [

2] Proponents of the extracardiac conduit tout the ease of surgical technique, preservation of normal atrial pressure, avoidance of atrial suture lines, reduction in arrhythmia burden, and avoidance of cardioplegic arrest. Regardless of the technique, all Fontan conduit choices inevitably result in Fontan failure.[

4] Among patients living with a Fontan circulation, approximately 20-30 percent experience signs and symptoms of Fontan failure. [

5] These include exercise intolerance, arrhythmias, pleural effusions, ascites, cyanosis, ventricular dysfunction, hepatic cirrhosis, protein losing enteropathy, and plastic bronchitis. Fontan failure arises as a result of nonpulsatile pulmonary blood flow, chronic elevation of systemic venous pressure, and low cardiac output. [

6] In the case of the extracardiac Fontan, conduit undersizing (or outgrowth) can result in hepatic congestion and cirrhosis, and conduit oversizing can lead to inefficient flow, stagnation, and thrombosis. [

7,

8]

The evolution of the Fontan procedure included iterations which attempted to utilize the atrium as a source of contractility for pulmonary blood flow. These include atriopulmonary Fontans and autogenous intraatrial tunnel Fontans. [

9,

10] The techniques avoided prosthetic material entirely, thus obviating the need for anticoagulation and maintaining growth potential. However, the procedures inherently reduced atrial size, introduced arrhythmic foci, risked native sinus node dysfunction, and were more complex to perform than either a lateral tunnel or extracardiac Fontan. Therefore, these techniques are thus obsolete.

Approaches for Subpulmonary Fontan Assist Pumps

The state of the art for subpulmonary Fontan assist pumps is based on mechanical engineering and tissue engineering. The most promising instance of a mechanical subpulmonary pump is based on an impeller. [

11] An extensive research effort has also focused on tissue engineering. Tissue engineered heart tissue was used to engineer a tubular Fontan conduit with embedded stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. [

12] However, neither mechanical engineering nor tissue engineering approaches have been translated from pre-clinical development into clinical practice.

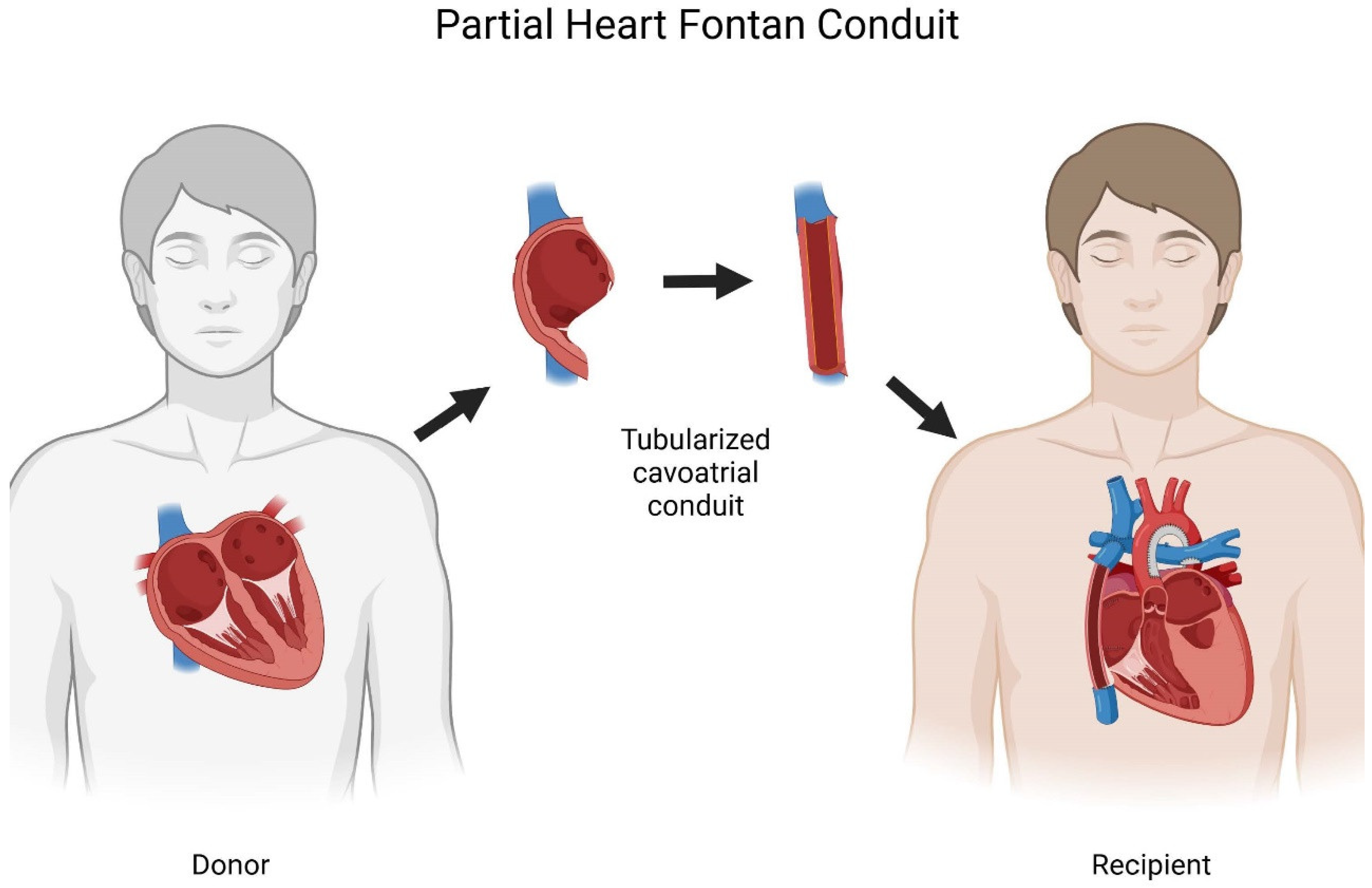

A New Approach for Subpulmonary Fontan Assist Based on Partial Heart Transplantation

Here we propose partial heart transplantation as a new approach to provide a subpulmonary Fontan assist pump that is based on transplantation. Partial heart transplants differ from heart transplants because only the necessary part of the heart is transplanted, while the native ventricle is preserved. [

13] Preserving the native ventricles increases the pool of donor hearts, because it offers the potential for using declined donors, transplant recipients with structurally normal hearts in a domino transplant, and longer tolerable ischemic times.[

14,

15,

16] So far, partial heart transplantation was clinically applied to provide growing heart valve implants.[

14,

17,

18] In the case of heart valves, the biological functions of the partial heart transplant are growth and self-repair.

Disadvantages / Potential Pitfalls

The advantages of partial heart transplantation need to be balanced against possible risks. Most importantly, partial heart transplantation would require immunosuppression to maintain viability of the atrial myocardial cells. The risks of immunosuppression are well known, based on an extensive experience with heart transplants. Notably, it is thought that partial heart transplant for semilunar valves may tolerate a lower level of immunosuppression than heart transplants because heart transplant rejection primarily affects the ventricles. Alloimmunization to donor tissue would also be a concern for single ventricle patients who are potential future transplant recipients. Finally, partial heart transplantation for Fontan completion depends on the availability of donor hearts. Donor hearts are a scarce resource with alternative use in heart transplantation. However, donor hearts with ventricular dysfunction can exclusively be used for partial heart transplantation. Therefore, the wait-time for a partial heart transplant is far shorter than for a heart transplant. The dependency on availability of a donor heart would also convert a normally elective procedure into a relatively time-sensitive operation that requires logistical adaptation of organ allocation systems as well as involvement of a donor surgical team. Finally, it is unclear what the intrinsic heart rate of the conduit would be and how susceptible it will be to arrhythmias. Bradycardia could be treated by electrical pacing.

Experimental Plan

The plan to test our hypothesis would require preliminary studies in an animal model to prove the viability, maintenance of contractility, and growth in cavoatrial partial heart transplant grafts. We would then proceed with three-dimensional printing of congenital heart defects, and surgical studies in human cadavers to formalize the surgical technique. This data would then make it possible to obtain institutional review board approval for human studies. The likely initial approach would be to offer a partial heart cavopulmonary conduit replacement to individuals who have failing Fontan physiology who are poor candidates for conventional heart transplantation. If promising, then future studies would explore the partial heart cavopulmonary conduit as an alternative at the time of the initial Fontan procedure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, writing – original draft, writing- review and editing: HKT. Writing – review and editing: TKR

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Wu W, He J, Shao X. Incidence and mortality trend of congenital heart disease at the global, regional, and national level, 1990-2017. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020 Jun 5;99(23):e20593. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs JP, Maruszewski B. Functionally univentricular heart and the fontan operation: lessons learned about patterns of practice and outcomes from the congenital heart surgery databases of the European association for cardio-thoracic surgery and the society of thoracic surgeons. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2013 Oct;4(4):349–55.

- Rychik J, Atz AM, Celermajer DS, Deal BJ, Gatzoulis MA, Gewillig MH, et al. Evaluation and Management of the Child and Adult With Fontan Circulation: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019 Aug 6;140(6):e234–84. [CrossRef]

- Hong H, Menon PG, Zhang H, Ye L, Zhu Z, Chen H, et al. Postsurgical Comparison of Pulsatile Hemodynamics in Five Unique Total Cavopulmonary Connections: Identifying Ideal Connection Strategies. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2013 Oct;96(4):1398–404. [CrossRef]

- Deal BJ, Jacobs ML. Management of the failing Fontan circulation. Heart. 2012 Jul 15;98(14):1098–104. [CrossRef]

- Gewillig M, Brown SC. The Fontan circulation after 45 years: update in physiology. Heart. 2016 Jul 15;102(14):1081–6. [CrossRef]

- Itatani K, Miyaji K, Tomoyasu T, Nakahata Y, Ohara K, Takamoto S, et al. Optimal conduit size of the extracardiac Fontan operation based on energy loss and flow stagnation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009 Aug;88(2):565–72; discussion 572-573. [CrossRef]

- Kisamori E, Venna A, Chaudhry HE, Desai M, Tongut A, Mehta R, et al. Alarming rate of liver cirrhosis after the small conduit extracardiac Fontan: A comparative analysis with the lateral tunnel. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2024 Oct;168(4):1221-1227.e1. [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto K, Kurosawa H, Tanaka K, Yamagishi M, Koyanagi K, Ishii S, et al. Total cavopulmonary connection without the use of prosthetic material: Technical considerations and hemodynamic consequences. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 1995 Sep;110(3):625–32. [CrossRef]

- Xing Q, Shi L, Han L, Wu Q. Total cavopulmonary direct anastomosis in the beating heart without prosthetic material: preliminary experience with modified extracardiac fontan procedure. J Card Surg. 2013 Sep;28(5):576–9. [CrossRef]

- Rodefeld MD, Marsden A, Figliola R, Jonas T, Neary M, Giridharan GA. Cavopulmonary assist: Long-term reversal of the Fontan paradox. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019 Dec;158(6):1627–36. [CrossRef]

- Köhne M, Behrens CS, Stüdemann T, Bibra C von, Querdel E, Shibamiya A, et al. A potential future Fontan modification: preliminary in vitro data of a pressure-generating tube from engineered heart tissue. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2022 Jul 11;62(2):ezac111. [CrossRef]

- Rajab TK. Evidence-based surgical hypothesis: Partial heart transplantation can deliver growing valve implants for congenital cardiac surgery. Surgery. 2021 Apr;169(4):983–5. [CrossRef]

- Rajab TK. Partial heart transplantation: Growing heart valve implants for children. Artificial Organs. 2024 Apr;48(4):326–35. [CrossRef]

- Quintao R, Kwon JH, Bishara K, Rajab TK. Donor supply for partial heart transplantation in the United States. Clin Transplant. 2023 Oct;37(10):e15060. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen SN, Schiazza A, Richmond ME, Zuckerman WA, Bacha EA, Goldstone AB. Trends in pediatric donor heart discard rates and the potential use of unallocated hearts for allogeneic valve transplantation. JTCVS Open. 2023 Sep;15:374–81. [CrossRef]

- Rajab TK, Vogel AD, Alexander VS, Brockbank KGM, Turek JW. The future of partial heart transplantation. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2024 Jun;43(6):863–5.

- Turek JW, Kang L, Overbey DM, Carboni MP, Rajab TK. Partial Heart Transplant in a Neonate With Irreparable Truncal Valve Dysfunction. JAMA. 2024 Jan 2;331(1):60–4. [CrossRef]

- Amirghofran A, Edraki F, Edraki M, Ajami G, Amoozgar H, Mohammadi H, et al. Surgical repair of tetralogy of Fallot using autologous right atrial appendages: short- to mid-term results. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 2021 Apr 13;59(3):697–704. [CrossRef]

- Talwar S, Siddharth CB, Choudhary SK, Kumar AS. The use of an autologous right atrial free wall as a patch for closure of atrial septal defects. J Card Surg. 2020 Jul;35(7):1414–9. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).