Submitted:

21 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Reference | Dimensions, numerical method, and software | OC and reactor | Mass and momentum conservation | Energy conservation | Radiative heat transfer | Chemistry and kinetics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lapp et al. [43], 2013 | 2D model. | No OC reactions implemented. Counter-rotating cylinders reactor with solid-solid heat recovery. |

n.a. | LTE is assumed between the solid and gas phases. | RDA and Monte Carlo ray tracing. | No kinetics implemented (only thermal model). |

| Lapp et al. [47], 2014 | Transient 3D model. | Isotropic porous ceria (ε=0.75). Counter-rotating cylinders reactor with solid-solid heat recovery. |

n.a. | LTE is assumed between the solid and gas phases. | RDA. The surface is assumed to be opaque. | Equilibrium is implemented. Reduction is supposed to be “fast”; oxidation is supposed to reach near-completion at the temperatures predicted in the oxidation zone. Nonstoichiometry is supposed to decrease linearly to zero across the oxidation zone, in the absence of kinetic rate expressions. |

| Keene et al. [29], 2013 | Axisymmetric cylindrical domain. Finite volume method with in-house developed Fortran code. |

Porous ceria (ε=0.75), supposed homogeneous, isotropic, dimensionally stable. Directly irradiated. |

Mass conservation is formulated for solid and gas phases, and individual components of the fluid phase (i.e., argon and oxygen). Darcy’s law is used for momentum conservation. | LTNE - each phase (solid and gas) is described with its energy equation. | Radiatively participating solid, radiatively nonparticipating gas. RDA for the optically thick medium is implemented. Irradiated boundary treated as a black surface. | Solid-gas interface kinetics is implemented. A model is developed for the adsorption/desorption of oxygen across the solid-gas interface to accurately describe the kinetics in terms of the local T, pO2 and δ. Only reduction is simulated. |

| Keene et al. [30], 2014 | 1D model. Finite volume method with in-house developed Fortran code. | Porous ceria monolith. Cavity-type, directly irradiated. | Mass conservation is formulated for solid and gas phases, and individual components of the fluid phase (i.e., argon and oxygen). Darcy’s law is used for momentum conservation. | LTNE - each phase (solid and gas) is described with its energy equation. | Radiatively participating solid, radiatively nonparticipating gas. Internal radiative heat transport modelled with RDA. | Solid-gas interface kinetics is implemented. Kinetics is implemented through the model developed by Keene et al.[29]. Kinetic rate constant is enforced to be sufficiently high to simulate equilibrium chemistry (i.e., transport-limited regime). Only reduction is simulated. |

| Bala Chandran et al. [31], 2015 | 3D model of a single reactive element. Transport equations are solved in ANSYS Fluent 14.0.1. | Porous ceria supposed homogeneous, isotropic, and with constant porosity (ε=0.65) and specific surface area. Cylindrical cavities, directly irradiated. | Mass conservation is formulated for solid and gas phases, considering interfacial mass transfer due to oxygen release upon reduction. Momentum transport is formulated using the Darcy-Brinkman-Forchheimer model. | LTE is assumed between the solid and gas phases. | Radiatively participating solid, radiatively nonparticipating gas. Internal radiative heat transport modelled with RDA. | Solid-gas interface kinetics is implemented. Kinetics is implemented through the model developed by Keene et al.[29]. Only reduction is simulated. |

| Bala Chandran et al. [49], 2016 | Transient 3D model developed in ANSYS Fluent 15.0. | Isothermal, pressure-swing ceria redox cycle. Packed bed (εbed=0.45) of ceria porous particles (εp=0.75). | Volume-averaged mass and momentum conservation. Brinkman-Forchheimer law is used for momentum conservation. Binary mass diffusivities obtained from the Chapman-Enskog theory. | LTE is assumed between the solid and gas phases. | Combination of Monte Carlo ray tracing and a discrete ordinates model. | Reduction and CO2-driven oxidation are simulated. The kinetics from Bulfin et al. [41] is used to impose the thermodynamic equilibrium constraint, coupled with the CO2 thermal dissociation at high temperature. |

| Bader et al. [44], 2015 | 3D finite element model. | Isothermal, pressure-swing ceria redox cycle. Porous ceria particles, mm-scale porosity. Packed-bed cavity, indirectly irradiated (alumina tubes for the single reactive elements). Pressure drop and effective thermal conductivity are compared for a 65% porous monolith, packed bed of 5 mm 70% porous particles, 5 μm solid particles, and 92% porous RPC. | Extended Darcy’s law is used for the pressure drop estimation. | LTE is assumed between the solid and gas phases. | Monte Carlo ray tracing and RDA. | Thermal and linear elastic thermo-mechanical model of the isothermal redox cycle. No kinetics implemented. |

| Wang et al. [57], 2021 | 3D heat and mass transfer model. | Iron-manganese oxides. Packed-bed reactor. |

Mass and species conservation equations are solved separately for each phase. Momentum equation is solved only for the gas phase (solid phase is immobile). | LTNE - each phase (solid and gas) is described with its energy equation. | Radiative transport equation. | Global kinetics is implemented. |

| Lidor et al. [32], 2020 | 1D model. MONROE code (developed at DLR). | Macroporous ceria. ASTOR reactor. |

Darcy-Dupuit-Forchheimer law is used. | LTNE - each phase (solid and gas) is described with its energy equation. | RDA combined with Beer-Lambert law. | Equilibrium is implemented for ceria reduction (deduced/supposed). |

| Lidor et al. [46], 2021 | 1D model. MONROE code (developed at DLR). | Macroporous ceria. ASTOR reactor. |

Darcy-Dupuit-Forchheimer law is used. Oxygen exchange upon cooldown sweeping seems to be neglected. | LTNE - each phase (solid and gas) is described with its energy equation. | RDA combined with Beer-Lambert law. | Equilibrium is implemented for ceria reduction (as in Lidor et al.[32]) and oxidation (this latter is “supposed to be fast at every point in the reactor at each time step”). |

| Furler et al. [33], 2015 | In-house code, ANSYS CFX 14.0. | Single-scale porosity RPC ceria. Cavity receiver-reactor. | Mass, momentum, and species conservation equations expressed for the free-flow domains and the porous RPC domain. Momentum source according to Dupuit-Forchheimer law. | An interphaseal heat transfer coefficient is used, but LTE is imposed in practice through setting it artificially high (since diffusion is dominant over advection). | Radiative transfer equation. Radiatively participating RPC. | Only reduction is simulated, assuming equilibrium. “The reduction was modelled based on thermodynamic equilibrium, as previous work has shown that the overall kinetics were controlled by heat transfer”. |

| Zoller et al. [34], 2019 | 2D axysimmetric model. ANSYS CFX 17.0. | Dual-scale porosity RPC ceria. Cavity receiver-reactor. | n.a. | An interphaseal heat transfer coefficient is used, but LTE is imposed in practice through setting it artificially high. | Radiative transfer equation. Radiatively participating RPC. | Only reduction is simulated, assuming equilibrium. Heat transfer model. |

| Wang et al. [53], 2022 | 1D model. Axial macroscopic combined with radial mesoscopic model. | Porous ceria fixed bed. Directly irradiated. | Permeability tensor and flow resistance coefficient modelled by the Ergun equation. | LTNE. A radial mesoscopic heat transfer equation is also added to the solid phase. | P-1 model. | Reaction kinetics from Zhao et al. [54] is implemented for the H2-driven reduction and the H2O dissociation. |

| Dai et al. [55], 2022 | 1D model developed in COMSOL Multiphysics® 5.3. | Macroporous ceria. Directly irradiated. | Darcy-Brinkman-Forchheimer model is used for momentum conservation. | LTNE. | P-1 model. | The kinetics of both thermal reduction and H2O-driven oxidation is simulated with a similar approach as proposed by Bala Chandran et al. [49] and expressing the rate parameter as a function of temperature and reacting surface area. |

| Pan et al. [50], 2021 | 2D axisymmetric steady-state model. COMSOL Multiphysics®. | Oxygen-permeable ceria membrane reactor. | Navier-Stokes equations in the gas phase, no porous media (ceria dense membrane). Binary mass diffusion coefficients obtained from the Fuller-Schettler-Giliding equation. Oxygen ions migration in the membrane described by Fick's law. | No porous media. Convective heat transfer in the gas phase, and conductive heat transfer in the membrane. Simplified isothermal wall assumption. | Radiation is not modeled. | Reduction kinetics according to Bulfin et al. [41]. Oxidation kinetics according to Le Gal et al. [51]. A rate modification constant was included to consider the surface reaction on the ceria membrane. |

| Li et al. [36], 2020 | 3D model. ANSYS Fluent 17.1. | Single tube reactor featuring a downward ceria particle flow counter to an upward inert gas flow for ceria reduction. | Discrete particle phase studied with a Lagrangian-tracking approach. Gas phase resolved as a continuum with an Eulerian volume-averaged approach. Ambipolar diffusion is modelled within the ceria particles. | Isothermal conditions: . |

Radiation is not modeled. | Reduction kinetics is modelled according to Keene et al. [29], [30] and Bulfin et al. [41]. |

| Zhang and Smith [37], 2019 | 3D transient model. Soltrace software and STAR-CCM. | Directly irradiated, inert-swept partition-cavity solar thermochemical reactor, with a packed bed of CeO2 particles as the reactive material. | Mass conservation in the fluid and particle phases are coupled defining a CeO2 particle mass transfer rate from the rate equation as the O2 source. | The energy transfer between the fluid phase and the discrete particles is modelled through a convective heat transfer coefficient between the two phases. | Radiative transfer equation in the packed bed of particles. | Reduction kinetics is modelled according to Ishida et al. [42]. |

| Huang and Lin [45], 2021 | 3D steady-state non-isothermal model. COMSOL Multiphysics®. | Windowed (directly irradiated) and window-less (indirectly irradiated) designs. | Brinkman equations are implemented for mass and momentum conservation. | LTNE. | P1 approximation in the porous medium coupled to Surface-to-Surface radiation within the cavity and window. | Chemistry is not modelled. |

| Ma et al. [38], 2024 | 3D transient model. | Directly irradiated receiver-reactor containing a porous structure made of CeO2-ZrO2. Details on the morphology are not given explicitly. | Brinkman equations are implemented for mass and momentum conservation. | Heat transfer assumption in the porous medium not explicitly reported. | Approximation used not clearly stated. | Reduction kinetics is modelled according to Bulfin et al. [41]. |

| Wei et al. [58], 2024 | ANSYS Fluent 16.0 coupled with the Monte Carlo method. | Dense ceria tubular membrane reactor integrated with heat recovery for continuous fuel production. | Darcy-Brinkman-Forchheimer model is used for the momentum conservation. | LTNE in the alumina RPC. | Radiative transfer equation. | Kinetics is not implemented. |

| Lougou et al. [59], 2018 | Model developed in COMSOL Multiphysics® 5.3. | Porous NiFe2O4. | Brinkman equations are implemented for mass and momentum conservation in the porous medium. | Heat transfer assumption in the porous medium not explicitly reported. | RDA in the porous medium coupled to Surface-to-Surface radiation. | Chemistry is not modelled. |

| Li et al. [39], 2016 | 3D transient heat transient model. | Indirectly irradiated cavity receiver-reactor; an array of tubular absorbers with ceria particles packed bed loading. | Fluid flow governing equations are not reported (only heat transfer and thermal reduction model). | LTE. | Collision-based Monte Carlo ray tracing model inside the cavity. RDA in the porous bed. | Only reduction is simulated. Ceria is supposed to be at thermodynamic equilibrium (i.e., no kinetics is modelled) according to Bulfin et al. [41]. |

| This work | 1D model developed in COMSOL Multiphysics® 6.2. | Macroporous ceria. Directly irradiated. | Darcy-Forchheimer law is used. Binary mass diffusivities obtained from the Chapman-Enskog theory. | LTNE. | RDA. | Reduction kinetics is modelled according to Bulfin et al. [41]. Oxidation kinetics is modelled according to Arifin et al. [60], rearranging the apparent kinetic law into a local kinetic law. |

2. Model

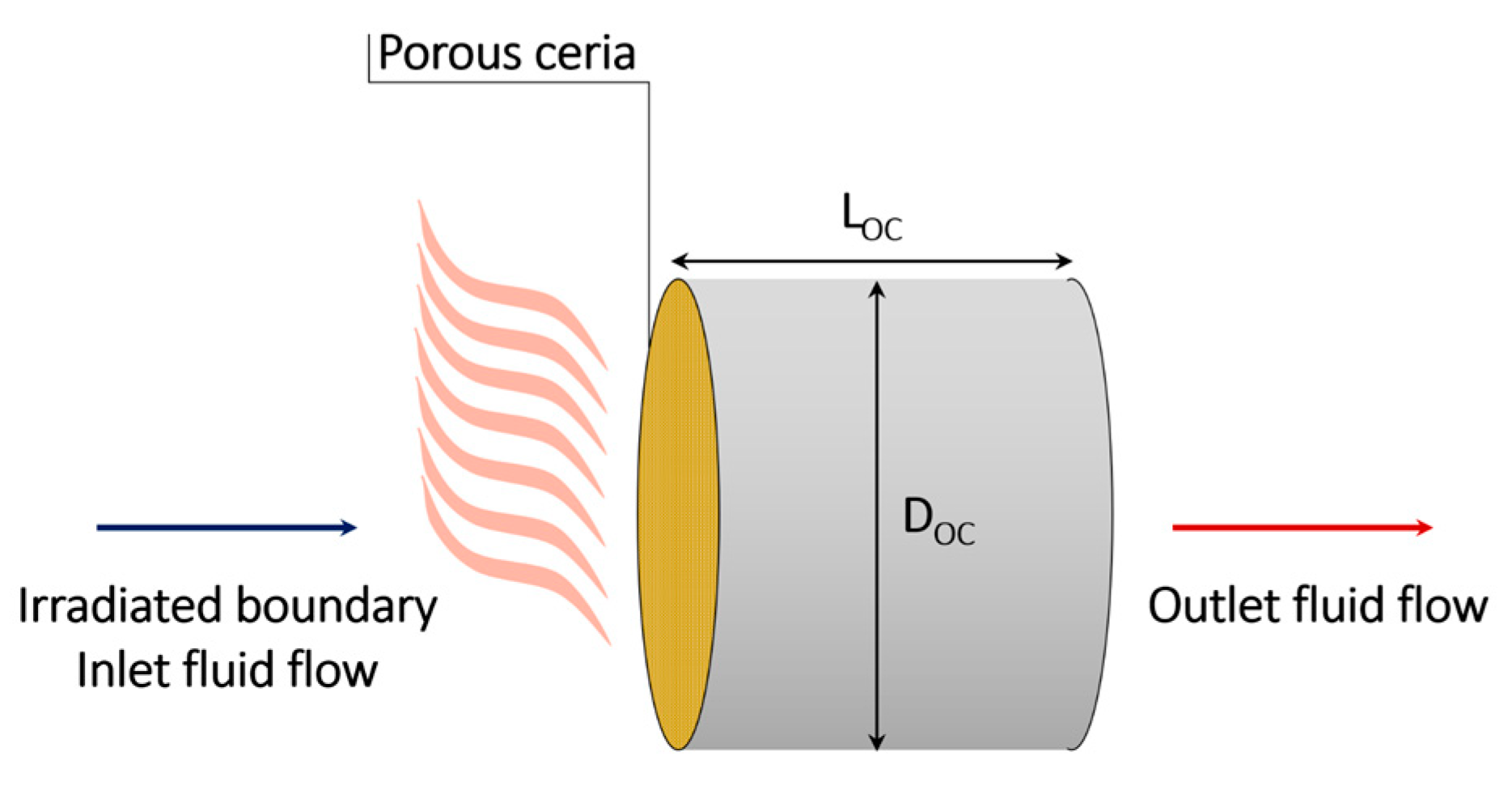

2.1. Geometry

2.2. Mass and Species Conservation

2.3. Momentum Conservation

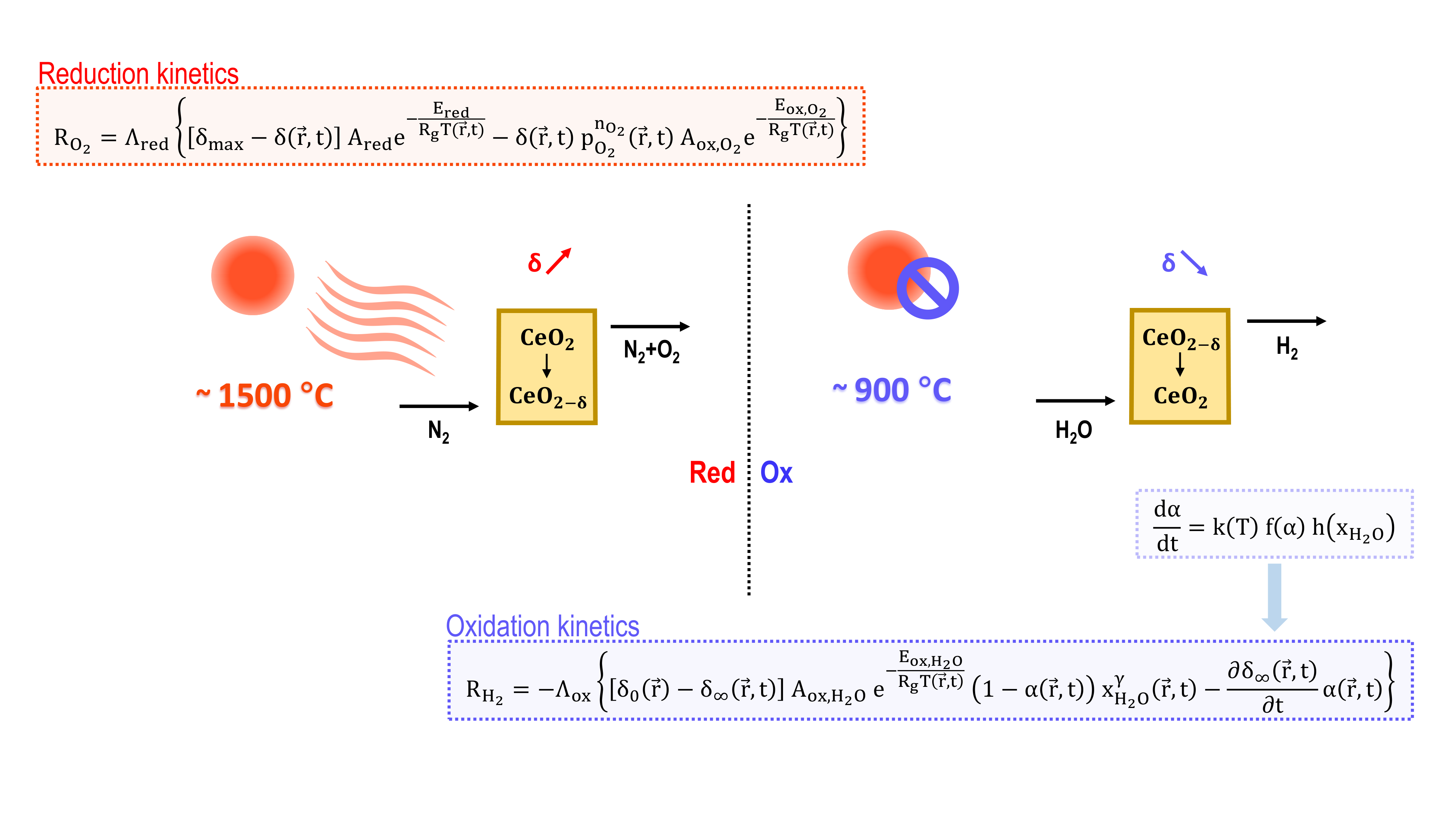

2.4. Reaction Kinetics

2.4.1. Thermal Reduction

2.4.2. H2O-Driven Oxidation

2.5. Energy Conservation

2.6. Initial and Boundary Conditions

2.6.1. Initial Conditions

| Initial or boundary condition | Value | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Mass and species conservation | ||

| Initial O2 molar fraction (first reduction) | 10-6 (balance N2) | |

| Initial H2 molar fraction (oxidation) | 0 | |

| Initial H2O molar fraction (oxidation) | 0 | |

| Inlet O2 molar fraction (reduction and oxidation) | 10-6 (balance N2) | |

| Inlet H2 molar fraction (oxidation) | 0 | |

| Inlet H2O molar fraction (oxidation) (base case | parametric range) |

0.2 | 0.2 – 0.4 (balance N2) | |

| Momentum conservation | ||

| Initial pressure (first reduction) | 1 | |

| Inlet volume flow rate during reduction (base case | parametric range) |

1 | 0.5 – 2 | |

| Inlet volume flow rate during oxidation | 1 | |

| Outlet pressure | 1 | |

| Reaction kinetics | ||

| Initial nonstoichiometry (first reduction) | 0 | |

| Initial nonstoichiometry time derivative (first reduction) | 0 | |

| Heat transfer | ||

| Initial temperature (first reduction) | 25 | |

| Inlet fluid temperature (reduction | oxidation) | 25 | 300 | |

| Incident radiative power (reduction | oxidation) | 1.5 | 0.5 | |

| Inlet boundary | Re-radiation towards | - |

| Outlet boundary | Thermal insulation | - |

| Other | ||

| Oxidation switching time | 60 | |

| Step duration (reduction | oxidation) (first cycle) | 5000 | 600 |

2.6.2. Boundary Conditions

2.7. Physical properties

2.8. Morphological and Effective Transport Properties

2.9. Numerical Methods and Computational Optimization

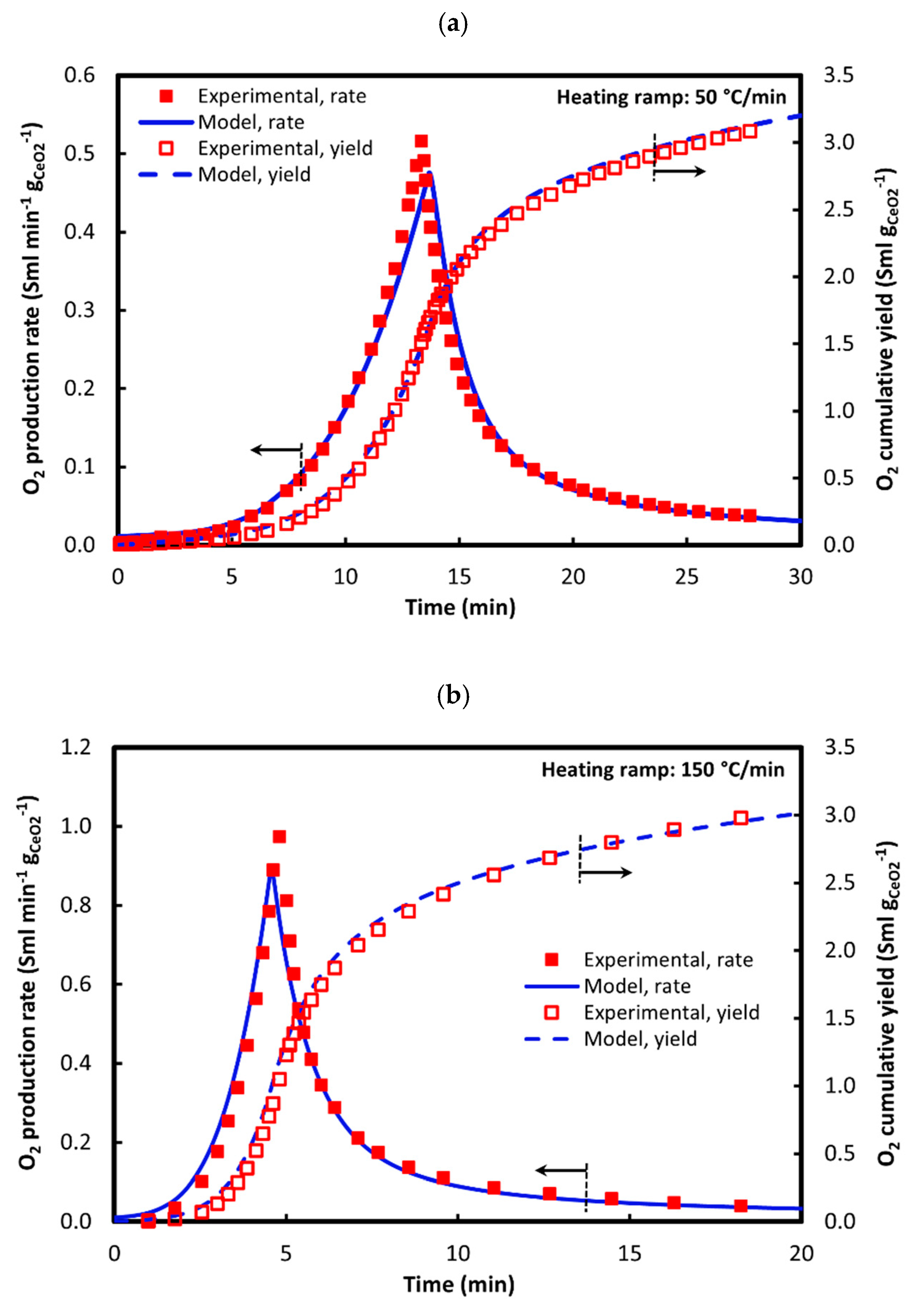

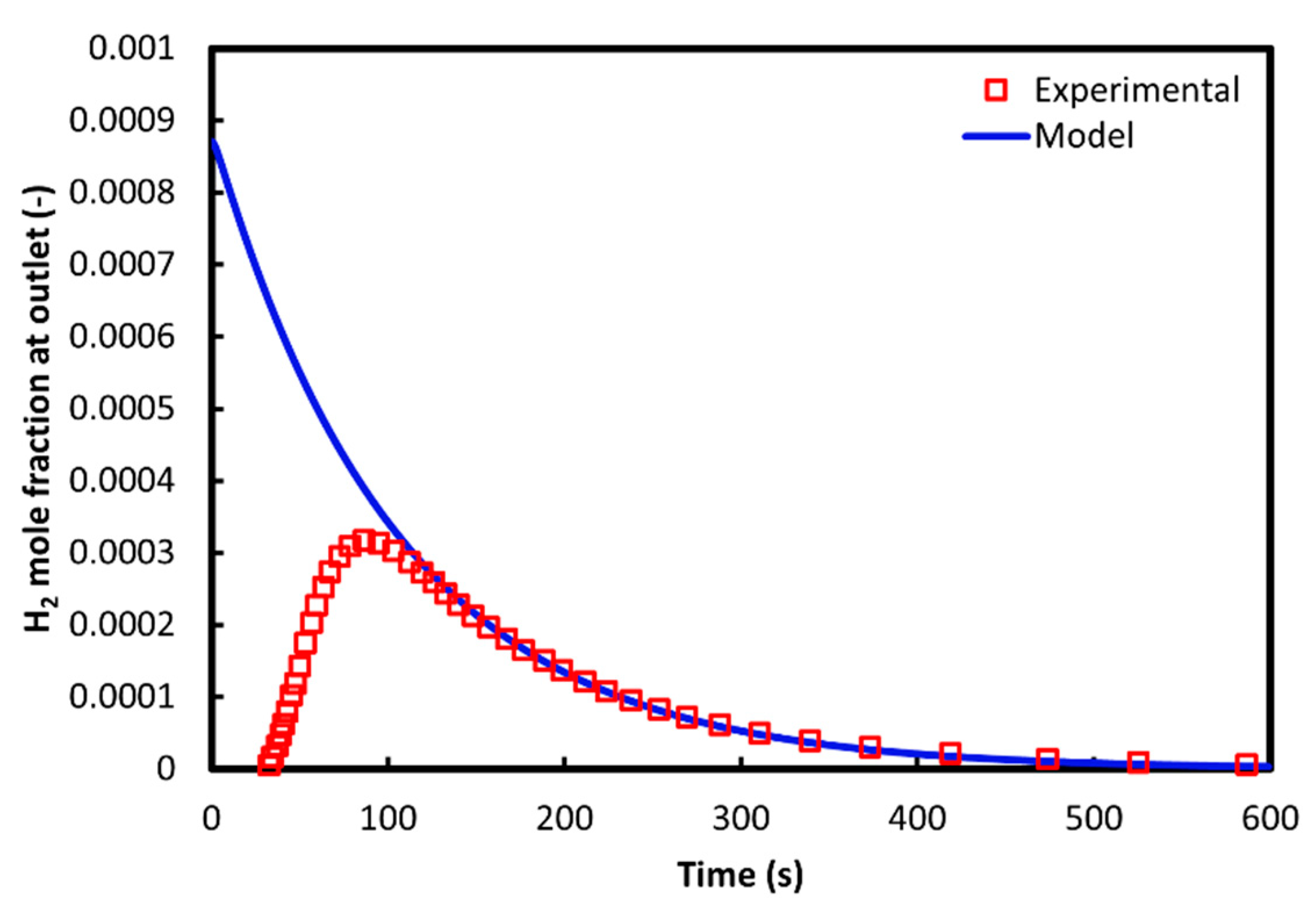

2.10. Validation

| Parameter | Experimental value [62] |

|---|---|

| Ceria mass (g) | 0.46 |

| Ceria bulk porosity (-) | 0.86 |

| Inner diameter (cm) | 0.635 |

| Temperature ramp (°C/min) | 50 or 150 |

| Initial temperature (°C) | 805 |

| Final temperature (°C) | 1488 |

| Inlet flow rate (sccm) | 463 |

| O2 inflow (ppm) | 10.8 |

| Reference conditions | 0 °C, 1 atm |

3. Results and Discussion

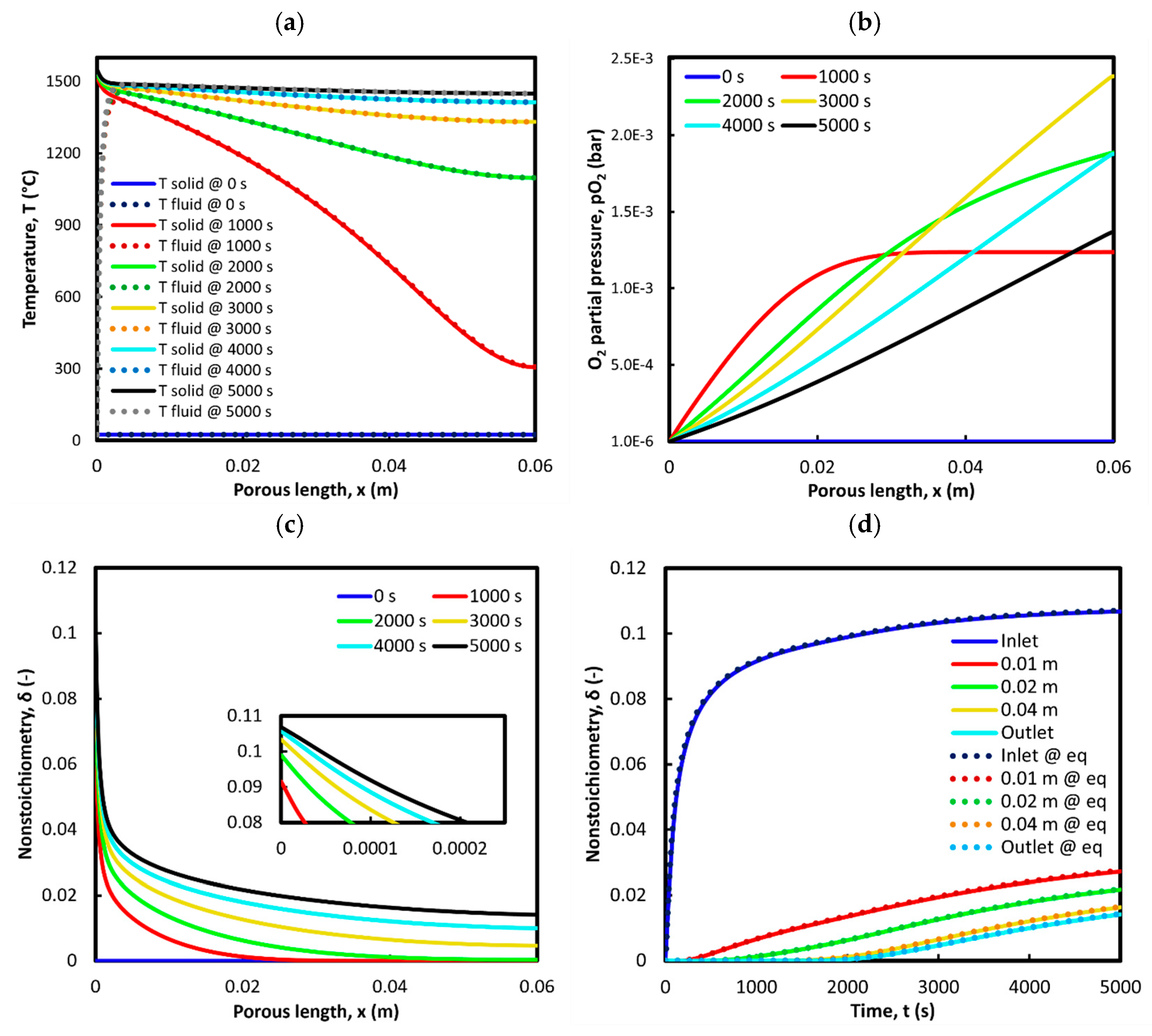

3.1. Reduction: 1st Cycle (Base Case)

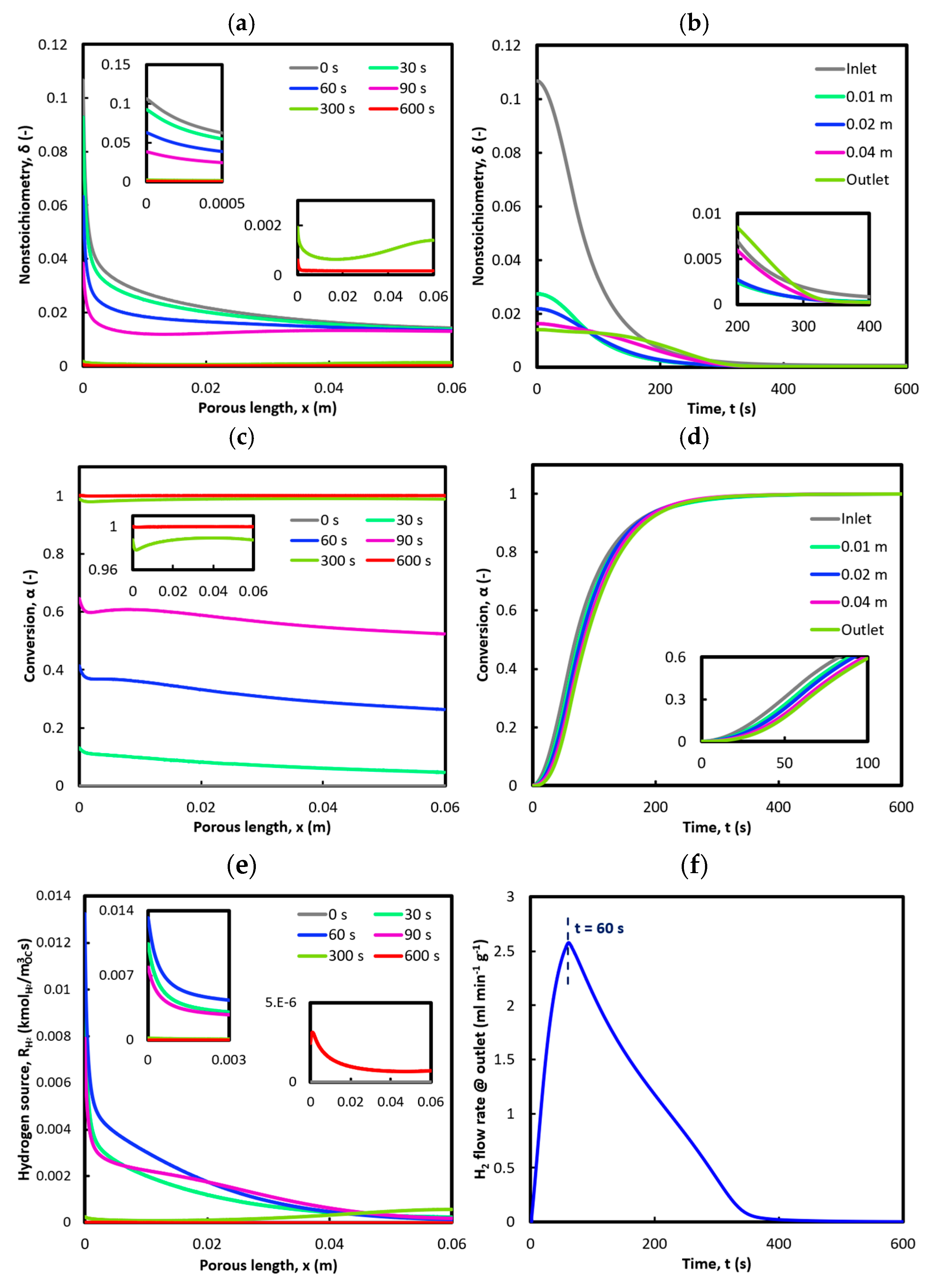

3.2. Oxidation: 1st Cycle (Base Case)

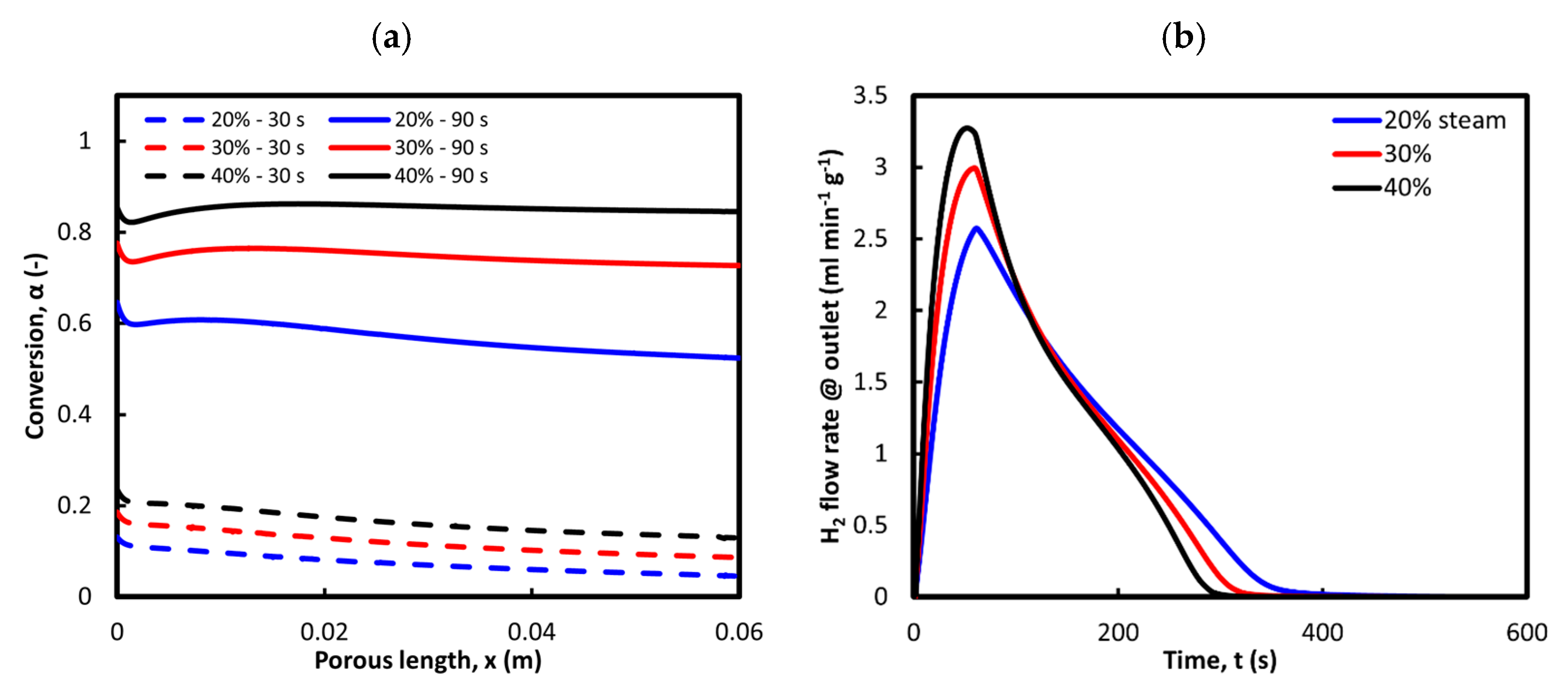

3.3. Parametric Study

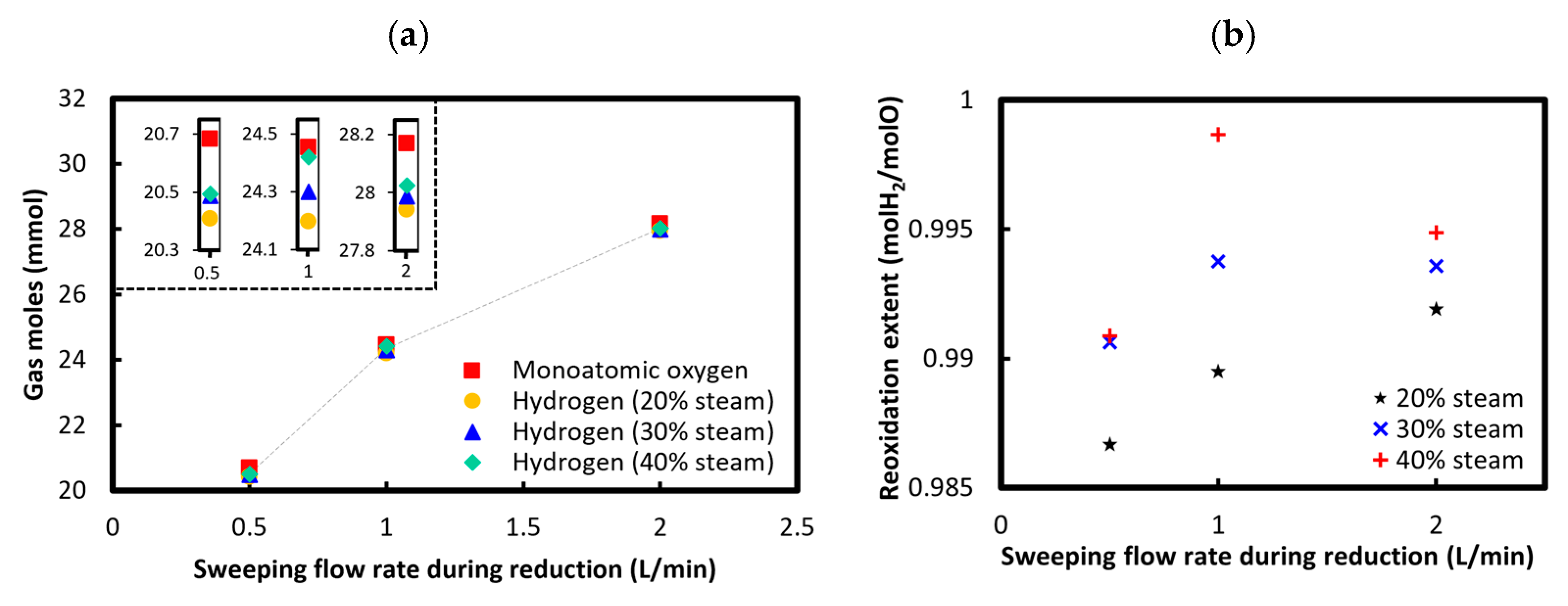

3.3.1. Sweeping Gas Flow Rate During Reduction

3.3.2. Steam Concentration During Oxidation

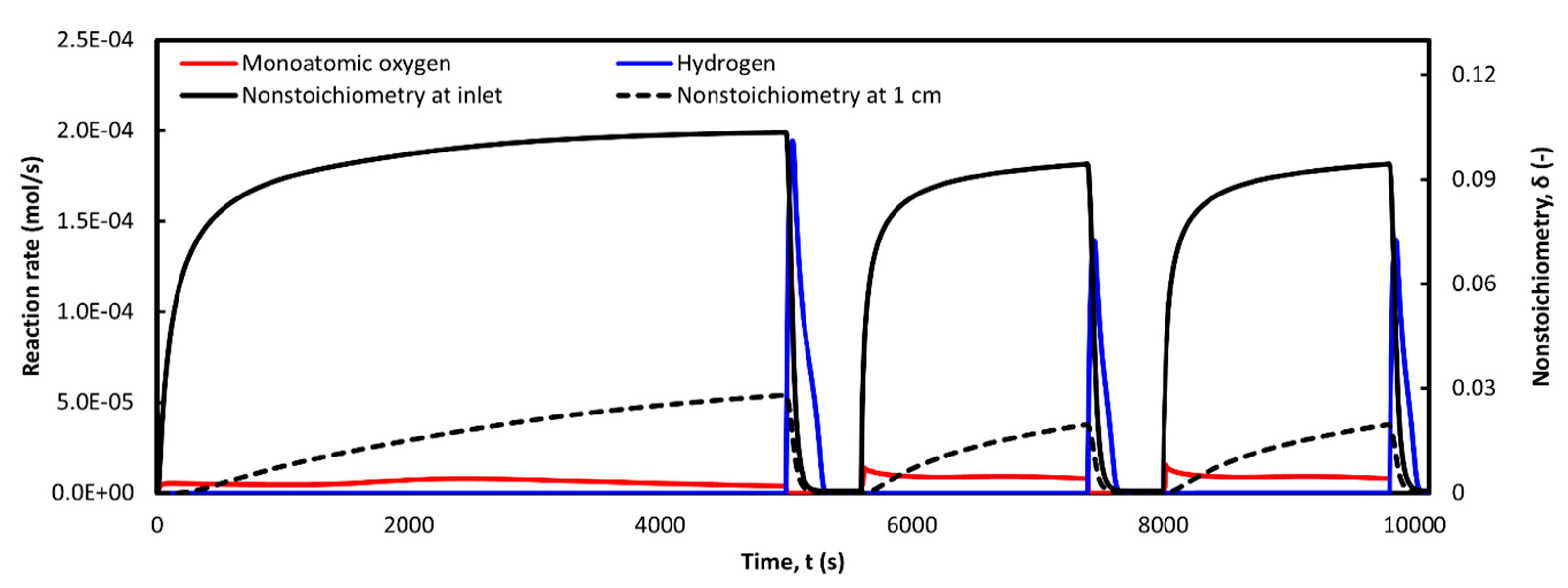

3.4. Verification of the Redox Model

3.5. Multiple Cycling

4. Model Applications

- i.

-

The analytical model makes use of global (or apparent) kinetic laws, that can be obtained experimentally from thermogravimetry or online gas analysis. Typically, a solid-state rate equation of this type is expressed in the following form [40], [60], as also described in more detail in Section 2.4.2:The solid conversion variation in time thus results from the factorized contributions of the reaction temperature, , of the solid conversion itself, , and of the gas atmosphere through the reactants’ partial pressure or molar fraction, . Extensive literature is available on this type of kinetic studies [40], and a considerable number of previous works addressed the definition of this kind of kinetic laws in chemical looping redox cycles and with different Oxygen Carriers (OCs), such as H2-assisted Fe3O4 reduction to FeO/Fe [79], isothermal reverse water-gas shift chemical looping of Fe2O3-Ce0.5Zr0.5O2 [80], H2-assisted reduction of Fe3O4/ZrO2 composite [81], CH4-assisted reduction of Fe3O4 [82], and CH4-assisted reduction of nonstoichiometric LaFeO3 [83]. Most interestingly, the ceria redox cycle was studied with this approach [13], with relevant examples for the CO2 [52] and H2O splitting step [60]. The usefulness of extracting a complete kinetic law lies in its potential use in modelling reactor systems and simulating the process behaviour. However, apparent kinetic laws are obtained from experiments as a bulk measurement on the tested sample. This aspect is well highlighted in a recent review on solar thermochemical reaction systems modelling [28]: “The use of this experimental data directly in a continuum model […] requires some care since this is a bulk solid measurement that must be related to local gas/solid concentrations”. Our analytical model meets this gap, allowing to convert a global kinetic law into a local kinetic law, that can be readily coupled to other physics in reactor-level numerical modelling. The simple method consists of expressing the solid conversion as a function of the nonstoichiometry of the OC instead of as a function of the sample mass, thereby addressing a local dependence instead of a global, bulk dependence. This allows to correlate with via differentiation, and to eventually express the chemical species mass source/sink, , in terms of the local fields (e.g., temperature and species concentrations).

- ii.

- The approach developed well fits to any nonstoichiometric oxide, that is used as the OC in any chemical looping redox cycle for synthetic fuels production. Indeed, the equations derived herein for the H2O-driven oxidation of ceria can be adapted to CO2-driven oxidation and to fuel-assisted reduction reactions (such as in the reverse water-gas shift H2-assisted process [123], or in the methane reforming process [85]), through the reactant concentration dependent term, as well as to thermal reduction reactions. Although sparse examples in the literature [57], to the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that an analytical approach is rigorously derived for using apparent kinetics in (solar) reactor continuum-level modeling, and is applied to thermochemical fuel production. Robust validation against experimental data secures the validity of our methodology.

- iii.

- In this work, a kinetic law taking into account only the forward reaction was considered, according to Arifin et al. [60]. Details are given in Section 2.4.2. As mentioned, this form of the rate equation is valid given that the reaction products can be removed in a sufficiently fast way, such as to prevent the backward reaction. Equivalently, this happens when a large excess of gaseous reactant is supplied to the reaction site [40]. When dealing with thermochemical splitting, this condition should be typically met when using perovskite OCs, which have shown higher reduction extent and lower reduction temperatures than ceria but a lower re-oxidation extent at the same time, unless oxidant in excess is used to boost the thermodynamic driving force [7], [15]. Thus, the form of the model presented in this work perfectly matches the kinetic rate equation form that is usually suitable for perovskite OCs. Besides, the large steam excess needed by perovskite OCs calls for the necessity to optimize the oxidation step in terms of fluid flow, kinetics, and reaction times. This can be addressed by using our methodology and suitable rate expressions for the OC under investigation.

- iv.

- Being based on a local approach, our analytical model is dimensionality independent. Thus, it can be applied to any (solar) reactor geometry and can be useful in modelling much more complex systems than the one simulated herein, up to complete 2D/3D models. The inherently local nature of the model also allows to obtain spatial distributions of the redox material conversion/utilization and reactivity in time, paving the way for optimization strategies of reactor’s design and operation.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LTE | Local Thermal Equilibrium |

| LTNE | Local Thermal Non-Equilibrium |

| RDA | Rosseland Diffusion Approximation |

| RPC | Reticulated Porous Ceramics |

| OC | Oxygen Carrier |

| Solid conversion, | |

| Rosseland mean extinction coefficient, | |

| Concentration exponent, | |

| Nonstoichiometry, | |

| Maximum nonstoichiometry, | |

| Macro-scale porosity, | |

| Density, | |

| Stefan-Boltzmann constant, | |

| Characteristic length, | |

| Proportionality constant, | |

| Dynamic viscosity, | |

| Mass fraction, | |

| Diffusion collision integral, | |

| Initial time | |

| Chemical | |

| Fluid | |

| ith chemical species | |

| Oxidation | |

| Radiation | |

| Reduction | |

| Solid | |

| Thermodynamic equilibrium | |

| Exposed (irradiated) area, | |

| Specific surface area, | |

| Preexponential factor, | |

| Heat capacity at constant pressure, | |

| Mean pore diameter, | |

| Diffusion coefficient, | |

| Diameter of the exposed (irradiated) area, | |

| Activation energy, | |

| Differential mechanistic model, | |

| Forchheimer coefficient, | |

| Water dissociation reaction enthalpy, | |

| Oxygen vacancy formation enthalpy, | |

| Heat transfer coefficient, | |

| Concentration dependent function, | |

| Diffusive flux, | |

| Rate constant, | |

| Thermal conductivity of the fluid phase, | |

| Thermal conductivity of the solid phase, | |

| Permeability, | |

| Thickness of the porous medium, | |

| Molar mass, | |

| Number of moles, | |

| O2 partial pressure exponent, | |

| Nusselt number, | |

| Pressure, or | |

| Prandtl number, | |

| Thermal power source or sink, | |

| Gas constant, | |

| Mass source, | |

| Reynolds number, | |

| sccm | Standard cubic centimeter |

| Temperature, | |

| Darcy velocity vector, | |

| Molar fraction, , or spatial coordinate, |

References

- L. Wei et al., “Solar-driven thermochemical conversion of H2O and CO2 into sustainable fuels,” iScience, vol. 26, no. 11, p. 108127, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. O. Jeje, T. Marazani, J. O. Obiko, and M. B. Shongwe, “Advancing the hydrogen production economy: A comprehensive review of technologies, sustainability, and future prospects,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 78, pp. 642–661, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. T. Tran, K. J. Warren, S. A. Wilson, C. L. Muhich, C. B. Musgrave, and A. W. Weimer, “An updated review and perspective on efficient hydrogen generation via solar thermal water splitting,” WIREs Energy and Environment, vol. 13, no. 4, p. e528, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Schäppi, V. Hüsler, and A. Steinfeld, “Solar Thermochemical Production of Syngas from H2O and CO2─Experimental Parametric Study, Control, and Automation,” Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., vol. 63, no. 8, pp. 3563–3575, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Schäppi et al., “Drop-in fuels from sunlight and air,” Nature, vol. 601, no. 7891, pp. 63–68, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Chang et al., “Recent Advances of Oxygen Carriers for Hydrogen Production via Chemical Looping Water-Splitting,” Catalysts, vol. 13, no. 2, p. 279, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Li et al., “Thermodynamic Guiding Principles for Designing Nonstoichiometric Redox Materials for Solar Thermochemical Fuel Production: Ceria, Perovskites, and Beyond,” Energy Tech, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 2000925, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Coronado and A. Bayón, “Catalytic enhancement of production of solar thermochemical fuels: opportunities and limitations,” Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., vol. 25, no. 26, pp. 17092–17106, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Lou et al., “Thermodynamic assessment of nonstoichiometric oxides for solar thermochemical fuel production,” Solar Energy, vol. 241, pp. 504–514, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Joshi et al., “Chemical looping-A perspective on the next-gen technology for efficient fossil fuel utilization,” Advances in Applied Energy, vol. 3, p. 100044, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Kim, H. S. Lim, H. S. Kim, M. Lee, J. W. Lee, and D. Kang, “Carbon dioxide splitting and hydrogen production using a chemical looping concept: A review,” Journal of CO2 Utilization, vol. 63, p. 102139, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. G. Al-Gamal et al., “Perovskite materials for hydrogen evolution: Processes, challenges and future perspectives,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 79, pp. 1113–1138, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Lu, “Solar fuels production: Two-step thermochemical cycles with cerium-based oxides,” Progress in Energy and Combustion Science, p. 49, 2019.

- A. Boretti, “Technology Readiness Level of Solar Thermochemical Splitting Cycles,” ACS Energy Lett., pp. 1170–1174, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. J. Carrillo and J. R. Scheffe, “Advances and trends in redox materials for solar thermochemical fuel production,” Solar Energy, vol. 156, pp. 3–20, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Scheffe and A. Steinfeld, “Oxygen exchange materials for solar thermochemical splitting of H2O and CO2: a review,” Materials Today, vol. 17, no. 7, pp. 341–348, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Lidor and B. Bulfin, “A critical perspective and analysis of two-step thermochemical fuel production cycles,” Solar Compass, vol. 11, p. 100077, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Mao et al., “Hydrogen production via a two-step water splitting thermochemical cycle based on metal oxide – A review,” Applied Energy, vol. 267, p. 114860, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Lu, L. Zhu, C. Agrafiotis, J. Vieten, M. Roeb, and C. Sattler, “Solar fuels production: Two-step thermochemical cycles with cerium-based oxides,” Progress in Energy and Combustion Science, vol. 75, p. 100785, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Weber, J. Grobbel, M. Neises-von Puttkamer, and C. Sattler, “Swept open moving particle reactor including heat recovery for solar thermochemical fuel production,” Solar Energy, vol. 266, p. 112178, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Brendelberger, P. Holzemer-Zerhusen, E. Vega Puga, M. Roeb, and C. Sattler, “Study of a new receiver-reactor cavity system with multiple mobile redox units for solar thermochemical water splitting,” Solar Energy, vol. 235, pp. 118–128, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Vega Puga, S. Brendelberger, A. Weber, and C. Sattler, “Modelling Development of a Receiver-Reactor of Type R2Mx for Thermochemical Water Splitting,” presented at the ASME 2023 17th International Conference on Energy Sustainability collocated with the ASME 2023 Heat Transfer Summer Conference, American Society of Mechanical Engineers Digital Collection, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. S. Patankar, X.-Y. Wu, W. Choi, H. L. Tuller, and A. F. Ghoniem, “A Reactor Train System for Efficient Solar Thermochemical Fuel Production,” Journal of Solar Energy Engineering, vol. 144, no. 6, p. 061014, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Gokon, S. Takahashi, H. Yamamoto, and T. Kodama, “New Solar Water-Splitting Reactor With Ferrite Particles in an Internally Circulating Fluidized Bed,” Journal of Solar Energy Engineering, vol. 131, no. 011007, Jan. 2009. [CrossRef]

- J. T. Tran et al., “Feasibility of continuous water and carbon dioxide splitting via a pressure-swing, isothermal redox cycle using iron aluminates,” Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 497, p. 154791, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Zoller et al., “A solar tower fuel plant for the thermochemical production of kerosene from H2O and CO2,” Joule, vol. 6, no. 7, pp. 1606–1616, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Marxer, P. Furler, M. Takacs, and A. Steinfeld, “Solar thermochemical splitting of CO 2 into separate streams of CO and O 2 with high selectivity, stability, conversion, and efficiency,” Energy Environ. Sci., vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 1142–1149, 2017. [CrossRef]

- V. M. Wheeler, R. Bader, P. B. Kreider, M. Hangi, S. Haussener, and W. Lipiński, “Modelling of solar thermochemical reaction systems,” Solar Energy, vol. 156, pp. 149–168, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Keene, J. H. Davidson, and W. Lipiński, “A Model of Transient Heat and Mass Transfer in a Heterogeneous Medium of Ceria Undergoing Nonstoichiometric Reduction,” Journal of Heat Transfer, vol. 135, no. 5, p. 052701, May 2013. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Keene, W. Lipiński, and J. H. Davidson, “The effects of morphology on the thermal reduction of nonstoichiometric ceria,” Chemical Engineering Science, vol. 111, pp. 231–243, May 2014. [CrossRef]

- R. Bala Chandran, R. Bader, and W. Lipiński, “Transient heat and mass transfer analysis in a porous ceria structure of a novel solar redox reactor,” International Journal of Thermal Sciences, vol. 92, pp. 138–149, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Lidor, T. Fend, M. Roeb, and C. Sattler, “Parametric investigation of a volumetric solar receiver-reactor,” Solar Energy, vol. 204, pp. 256–269, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Furler and A. Steinfeld, “Heat transfer and fluid flow analysis of a 4kW solar thermochemical reactor for ceria redox cycling,” Chemical Engineering Science, vol. 137, pp. 373–383, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Zoller, E. Koepf, P. Roos, and A. Steinfeld, “Heat Transfer Model of a 50 kW Solar Receiver–Reactor for Thermochemical Redox Cycling Using Cerium Dioxide,” Journal of Solar Energy Engineering, vol. 141, no. 2, p. 021014, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Sharma et al., “Chemical and thermal performance analysis of a solar thermochemical reactor for hydrogen production via two-step WS cycle,” Energy Reports, vol. 10, pp. 99–113, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Li, V. M. Wheeler, A. Kumar, and W. Lipiński, “Numerical modelling of ceria undergoing reduction in a particle–gas counter-flow: Effects of chemical kinetics under isothermal conditions,” Chemical Engineering Science, vol. 218, p. 115553, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang and J. D. Smith, “Investigating influences of geometric factors on a solar thermochemical reactor for two-step carbon dioxide splitting via CFD models,” Solar Energy, vol. 188, pp. 935–950, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Ma et al., “Analysis of heat and mass transfer in a porous solar thermochemical reactor,” Energy, vol. 294, p. 130842, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Li et al., “A transient heat transfer model for high temperature solar thermochemical reactors,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 41, no. 4, pp. 2307–2325, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Vyazovkin, A. K. Burnham, J. M. Criado, L. A. Pérez-Maqueda, C. Popescu, and N. Sbirrazzuoli, “ICTAC Kinetics Committee recommendations for performing kinetic computations on thermal analysis data,” Thermochimica Acta, vol. 520, no. 1–2, pp. 1–19, Jun. 2011. [CrossRef]

- B. Bulfin et al., “Analytical Model of CeO 2 Oxidation and Reduction,” J. Phys. Chem. C, vol. 117, no. 46, pp. 24129–24137, Nov. 2013. [CrossRef]

- T. Ishida, N. Gokon, T. Hatamachi, and T. Kodama, “Kinetics of Thermal Reduction Step of Thermochemical Two-step Water Splitting Using CeO2 Particles: MASTER-plot Method for Analyzing Non-isothermal Experiments,” Energy Procedia, vol. 49, pp. 1970–1979, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Lapp, J. H. Davidson, and W. Lipiński, “Heat Transfer Analysis of a Solid-Solid Heat Recuperation System for Solar-Driven Nonstoichiometric Redox Cycles,” Journal of Solar Energy Engineering, vol. 135, no. 3, p. 031004, Aug. 2013. [CrossRef]

- R. Bader et al., “Design of a Solar Reactor to Split CO2 Via Isothermal Redox Cycling of Ceria,” Journal of Solar Energy Engineering, vol. 137, no. 3, p. 031007, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. Huang and M. Lin, “Optimization of solar receivers for high-temperature solar conversion processes: Direct vs. Indirect illumination designs,” Applied Energy, vol. 304, p. 117675, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Lidor, T. Fend, M. Roeb, and C. Sattler, “High performance solar receiver–reactor for hydrogen generation,” Renewable Energy, vol. 179, pp. 1217–1232, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Lapp and W. Lipiński, “Transient Three-Dimensional Heat Transfer Model of a Solar Thermochemical Reactor for H2O and CO2 Splitting Via Nonstoichiometric Ceria Redox Cycling,” Journal of Solar Energy Engineering, vol. 136, no. 3, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. J. Venstrom, R. M. De Smith, R. Bala Chandran, D. B. Boman, P. T. Krenzke, and J. H. Davidson, “Applicability of an Equilibrium Model To Predict the Conversion of CO 2 to CO via the Reduction and Oxidation of a Fixed Bed of Cerium Dioxide,” Energy Fuels, vol. 29, no. 12, pp. 8168–8177, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- R. Bala Chandran and J. H. Davidson, “Model of transport and chemical kinetics in a solar thermochemical reactor to split carbon dioxide,” Chemical Engineering Science, vol. 146, pp. 302–315, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Pan, Y. Lu, and L. Zhu, “Numerical Modeling of CO2 Splitting in High-Temperature Solar-Driven Oxygen Permeation Membrane Reactors,” Journal of Solar Energy Engineering, vol. 143, no. 2, p. 021001, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Le Gal, S. Abanades, and G. Flamant, “CO 2 and H 2 O Splitting for Thermochemical Production of Solar Fuels Using Nonstoichiometric Ceria and Ceria/Zirconia Solid Solutions,” Energy Fuels, vol. 25, no. 10, pp. 4836–4845, Oct. 2011. [CrossRef]

- A. E. Farooqui et al., “Assessment of kinetic model for ceria oxidation for chemical-looping CO2 dissociation,” Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 346, pp. 171–181, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Wang, R. K. Wei, and K. Vafai, “A dual-scale transport model of the porous ceria based on solar thermochemical cycle water splitting hydrogen production,” Energy Conversion and Management, vol. 272, p. 116363, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhao, M. Uddi, N. Tsvetkov, B. Yildiz, and A. F. Ghoniem, “Redox Kinetics Study of Fuel Reduced Ceria for Chemical-Looping Water Splitting,” J. Phys. Chem. C, vol. 120, no. 30, pp. 16271–16289, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- X. Dai and S. Haussener, “Non-Uniform Porous Structures and Cycling Control for Optimized Fixed-Bed Solar Thermochemical Water Splitting,” Journal of Solar Energy Engineering, vol. 144, no. 3, p. 030904, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. de la Calle, I. Ermanoski, J. E. Miller, and E. B. Stechel, “Towards chemical equilibrium in thermochemical water splitting. Part 2: Re-oxidation,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 72, pp. 1159–1168, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Wang et al., “Thermal reduction of iron–manganese oxide particles in a high-temperature packed-bed solar thermochemical reactor,” Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 412, p. 128255, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Wei, Z. Li, Z. Pan, Z. Yi, G. Li, and L. An, “A design of solar-driven thermochemical reactor integrated with heat recovery for continuous production of renewable fuels,” Energy Conversion and Management, vol. 310, p. 118484, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Guene Lougou, Y. Shuai, R. Pan, G. Chaffa, and H. Tan, “Heat transfer and fluid flow analysis of porous medium solar thermochemical reactor with quartz glass cover,” International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 127, pp. 61–74, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Arifin and A., W. Weimer, “Kinetics and mechanism of solar-thermochemical H2 and CO production by oxidation of reduced CeO2,” Solar Energy, vol. 160, pp. 178–185, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. T. Krenzke and J. H. Davidson, “On the Efficiency of Solar H2 and CO Production via the Thermochemical Cerium Oxide Redox Cycle: The Option of Inert-Swept Reduction,” Energy Fuels, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 1045–1054, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- T. C. Davenport, M. Kemei, M. J. Ignatowich, and S. M. Haile, “Interplay of material thermodynamics and surface reaction rate on the kinetics of thermochemical hydrogen production,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 42, no. 27, pp. 16932–16945, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Le Gal, M. Drobek, A. Julbe, and S. Abanades, “Improving solar fuel production performance from H2O and CO2 thermochemical dissociation using custom-made reticulated porous ceria,” Materials Today Sustainability, vol. 24, p. 100542, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Bulfin, M. Zuber, O. Gräub, and A. Steinfeld, “Intensification of the reverse water–gas shift process using a countercurrent chemical looping regenerative reactor,” Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 461, p. 141896, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. E. Poling, J. M. Prausnitz, and J. P. O’Connell, The properties of gases and liquids, 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001.

- R. J. Panlener, “A THERMODYNAMIC STUDY OF NONSTOICHIOMETRIC CERIUM DIOXIDE”.

- S. Vyazovkin et al., “ICTAC Kinetics Committee recommendations for collecting experimental thermal analysis data for kinetic computations,” Thermochimica Acta, vol. 590, pp. 1–23, Aug. 2014. [CrossRef]

- B. Bulfin et al., “Thermodynamics of CeO2 Thermochemical Fuel Production,” Energy Fuels, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 1001–1009, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- F. Orsini et al., “Exsolution-enhanced reverse water-gas shift chemical looping activity of Sr2FeMo0.6Ni0.4O6-δ double perovskite,” Chemical Engineering Journal, p. 146083, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Marra, M. Santarelli, and D. Papurello, “Solar Dish Concentrator: A Case Study at the Energy Center Rooftop,” International Journal of Energy Research, vol. 2023, p. e9658091, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. O. of D. and Informatics, “NIST Chemistry WebBook.” Accessed: Apr. 22, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry/.

- I. Riess, M. Ricken, and J. No¨lting, “On the specific heat of nonstoichiometric ceria,” Journal of Solid State Chemistry, vol. 57, no. 3, pp. 314–322, May 1985. [CrossRef]

- S. Suter, A. Steinfeld, and S. Haussener, “Pore-level engineering of macroporous media for increased performance of solar-driven thermochemical fuel processing,” International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 78, pp. 688–698, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Sas Brunser et al., “Solar-Driven Redox Splitting of CO2 Using 3D-Printed Hierarchically Channeled Ceria Structures,” Advanced Materials Interfaces, vol. 10, no. 30, p. 2300452, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Petrasch, F. Meier, H. Friess, and A. Steinfeld, “Tomography based determination of permeability, Dupuit–Forchheimer coefficient, and interfacial heat transfer coefficient in reticulate porous ceramics,” International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 315–326, Feb. 2008. [CrossRef]

- M. A. A. Mendes, P. Talukdar, S. Ray, and D. Trimis, “Detailed and simplified models for evaluation of effective thermal conductivity of open-cell porous foams at high temperatures in presence of thermal radiation,” International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 68, pp. 612–624, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Loretz, E. Maire, and D. Baillis, “Analytical Modelling of the Radiative Properties of Metallic Foams: Contribution of X-Ray Tomography,” Adv Eng Mater, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 352–360, Apr. 2008. [CrossRef]

- B. Bulfin, F. Call, J. Vieten, M. Roeb, C. Sattler, and I. V. Shvets, “Oxidation and Reduction Reaction Kinetics of Mixed Cerium Zirconium Oxides,” Journal of Physical Chemistry C, vol. 120, no. 4, pp. 2027–2035, 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Barde, J. F. Klausner, and R. Mei, “Solid state reaction kinetics of iron oxide reduction using hydrogen as a reducing agent,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 41, no. 24, pp. 10103–10119, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Wenzel et al., “CO production from CO2 via reverse water–gas shift reaction performed in a chemical looping mode: Kinetics on modified iron oxide,” Journal of CO2 Utilization, vol. 17, pp. 60–68, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Q. Tang, Y. Ma, and K. Huang, “Fe 3 O 4 /ZrO 2 Composite as a Robust Chemical Looping Oxygen Carrier: A Kinetics Study on the Reduction Process,” ACS Appl. Energy Mater., vol. 4, no. 7, pp. 7091–7100, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Lu et al., “Chemical looping reforming of methane using magnetite as oxygen carrier: Structure evolution and reduction kinetics,” Applied Energy, vol. 211, pp. 1–14, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- X. Dai, J. Cheng, Z. Li, M. Liu, Y. Ma, and X. Zhang, “Reduction kinetics of lanthanum ferrite perovskite for the production of synthesis gas by chemical-looping methane reforming,” Chemical Engineering Science, vol. 153, pp. 236–245, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Wenzel, “Reverse water-gas shift chemical looping for syngas production from CO2,” Doctoral Thesis, 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. T. Krenzke, J. R. Fosheim, and J. H. Davidson, “Solar fuels via chemical-looping reforming,” Solar Energy, vol. 156, pp. 48–72, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

| Kinetic parameter | Value | Units |

|---|---|---|

| 720000 | ||

| 232 | ||

| 82 | ||

| 36 | ||

| 0.218 | 1 | |

| 1 | ||

| 29 | ||

| 0.89 | 1 |

| Property | Value | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Ceria | ||

| Porosity | 0.7 | |

| Molar mass | 172.115 [32] | |

| Density | 7215 [32] | |

| Thermal conductivity | 0.5615 [32] | |

| Heat capacity at constant pressure | [72] | |

| Gas mixture | ||

| Density | Molar fraction averaged | |

| Thermal conductivity | Molar fraction averaged | |

| Specific heat capacity | Mass fraction averaged | |

| Viscosity | Molar fraction averaged |

| Parameter | Experimental value [60] |

|---|---|

| Ceria mass (g) | 0.15 |

| Wall/inlet temperature (°C) | 800 |

| Reactor pressure (torr) | 75 |

| Inlet flow rate (sccm) | 500 |

| H2O inflow molar fraction (-) | 0.2 |

| Reduction temperature (°C) | 1500 |

| Reduction pressure (torr) | 600 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).