1. Introduction

The valorization of food waste without generating pollutants represents a significant challenge and a crucial priority for sustainable industrial development aimed at preserving the environment. Biomass waste, which includes materials such as walnut shells, [

1], pecan shells [

2], apple peels [

2], date pits [

3], olive pits [

4], peach pits [

5], corn cobs [

6], coffee beans [

7], coffee grounds [

2,

8,

9,

10,

11], tea waste [

12], bagasse [

13], and coconut shells [

14] presents a promising market for recycling and value addition. These materials are particularly noteworthy due to their high carbon content, which allows them to serve as precursors for the production of modified cellulosic products or activated carbon.Coffee stands out as one of the most widely consumed beverages globally. According to the International Coffee Organization, approximately 680 million tons of coffee were produced in 2008. While some of the coffee grounds generated are repurposed for various applications such as soil remediation or odor adsorption, the majority require carbonization before they can be utilized effectively [

8]. It is important to note that the combustion of 1,000 grams of coffee grounds is estimated to produce around 538 grams of carbon dioxide [

8]. This highlights the environmental impact associated with coffee waste and underscores the need for sustainable management practices.Cellulose extracted from used coffee grounds is recognized as a natural polymer and is one of the most abundant and widely utilized renewable materials in various industries. Its natural abundance is estimated to be in billions of tons annually, making it a valuable resource due to its well-established chemical versatility. Recent advances in understanding cellulose's structure and morphology—factors that significantly influence its reactivity—have spurred developments in its chemical modification. Despite historically limited information available on cellulose properties, recent technological progress has led to a significant expansion in the production of cellulose derivatives. These derivatives have found diverse applications across multiple fields including pharmaceuticals, food processing, papermaking, textiles, and chemicals. Additionally, emerging industries such as cosmetics and biotechnology are increasingly utilizing these cellulose derivatives.Chemical modification has emerged as one of the most extensively developed methods for enhancing cellulose properties. Among these methods, the oxidation of alcohol groups in cellulose carbohydrates has gained considerable attention in recent years. This growing interest can be attributed to the unique properties exhibited by oxidized polysaccharides and their potential for further modification through processes such as esterification. In our research focused on chemically modifying cellulose extracted from coffee grounds, we specifically selected the oxidation of alcohol groups to aldehydes or carboxylic acids. This oxidation process can be achieved through various methods utilizing a wide range of reagents; however, when selectivity or mild operational conditions are required, the selection of suitable reagents becomes more constrained.One effective and selective method for oxidation involves using oxoammonium salts, particularly di-tert-alkyl TEMPO (2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl radical). The TEMPO radical is generated in situ and selectively oxidizes primary and secondary alcohols in a chemoselective and regioselective manner. Among the available oxidants for this purpose, the TEMPO radical has emerged as one of the most widely studied and regenerated in contemporary research. The first documented use of this system for oxidizing water-soluble polysaccharides—such as starch, amylodextrin, and pullulans—was reported by De Nooy et al. in 1995 [

18]. In this study, we aimed to oxidize the alcohol groups present in cellulose extracted from coffee grounds using a sodium hypochlorite/sodium bromide system combined with the TEMPO radical (TEMPO–NaOCl–NaBr) at room temperature and pH 10. This particular system was chosen due to its high selectivity in oxidizing primary alcohols. Over time, several oxidation methods have been developed to selectively modify the hydroxyl groups of various polysaccharides including starch, pullulan (a sugar polymer composed of maltotriose units amylose [

15], cyclodextrins [

16,

17], and cellulose itself. These modifications enhance polysaccharide properties such as gel formation and super-absorbency, thereby enabling their application across various industries including detergents, papermaking, and medicine. The exploration of these modifications not only contributes to waste valorization but also supports broader sustainability goals by promoting the efficient use of renewable resources.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Dry Coffee Grounds:

The coffee grounds analyzed in this study were sourced from ZOUHOUR, a renowned commercial establishment specializing in coffee beverages. This establishment is situated in the vibrant city of Marrakech, Morocco, at geographical coordinates 31.642792, -7.981603. The coffee brand employed in the research was Amarito M Milagro, a carefully curated blend of Robusta and Arabica beans. Each package had a net weight of 1 kilogram (Image 1). This selection was made based on the coffee's popularity and its distinctive qualities, which contribute to its widespread appeal among local and international consumers.

2.2. Extraction and Purification of Cellulose:

The extraction and purification (or enrichment) of cellulose involve the removal of all contaminants, such as phenolic compounds, lignin, hemicelluloses, and other impurities, through specific chemical or enzymatic processes outlined below. Coffee grounds, while being a rich source of cellulose, also contain significant quantities of lignin, hemicelluloses, and other secondary compounds. These additional components must be effectively degraded or separated to isolate the cellulose in its purest form.

The process typically begins with a pretreatment step to break down the coffee grounds' complex matrix, facilitating the removal of non-cellulosic materials. This may include washing, drying, and grinding to achieve a uniform particle size. Following this, chemical treatments such as alkali extraction (using sodium hydroxide or potassium hydroxide) or oxidative delignification are applied to solubilize lignin and hemicelluloses. Acid hydrolysis may also be employed to further degrade hemicelluloses and eliminate residual impurities.

Alternatively, enzymatic methods can be used for a more environmentally friendly approach, leveraging enzymes such as cellulase or xylanase to selectively degrade non-cellulosic components. This method is particularly advantageous in reducing the use of harsh chemicals, thus minimizing environmental impact.

The final step involves washing and neutralizing the cellulose-rich material, followed by drying to obtain a purified cellulose product. This cellulose can then be further characterized or processed for various applications, such as in the production of bio-composites, bioplastics, or as a raw material in the textile and paper industries.

This multi-step approach ensures the efficient isolation of high-purity cellulose, making it suitable for a wide range of industrial and scientific purposes.

Alkaline Treatment: The removal of impurities and the conversion of coffee grounds into cellulose are achieved using sodium hydroxide (NaOH). An alkaline solution is typically employed to degrade lignin and hemicelluloses, thereby releasing cellulose in a fibrous form. In this study, coffee grounds were treated with a 1 N sodium hydroxide solution over three successive time intervals: 24 hours, 12 hours, and 6 hours. After each treatment, the mixture was thoroughly washed with water and filtered to isolate the cellulose.

Bleaching: To obtain high-purity cellulose, a bleaching process is employed to further remove residual impurities. This process can involve the use of hydrogen peroxide or chlorine dioxide. In this study, commercial bleach (sodium hypochlorite) was used as the bleaching agent. The treatment was carried out at 60 °C for 30 minutes. Following the bleaching, the material underwent triple filtration, thorough washing with water, and a final rinse with acetone to ensure complete purification.

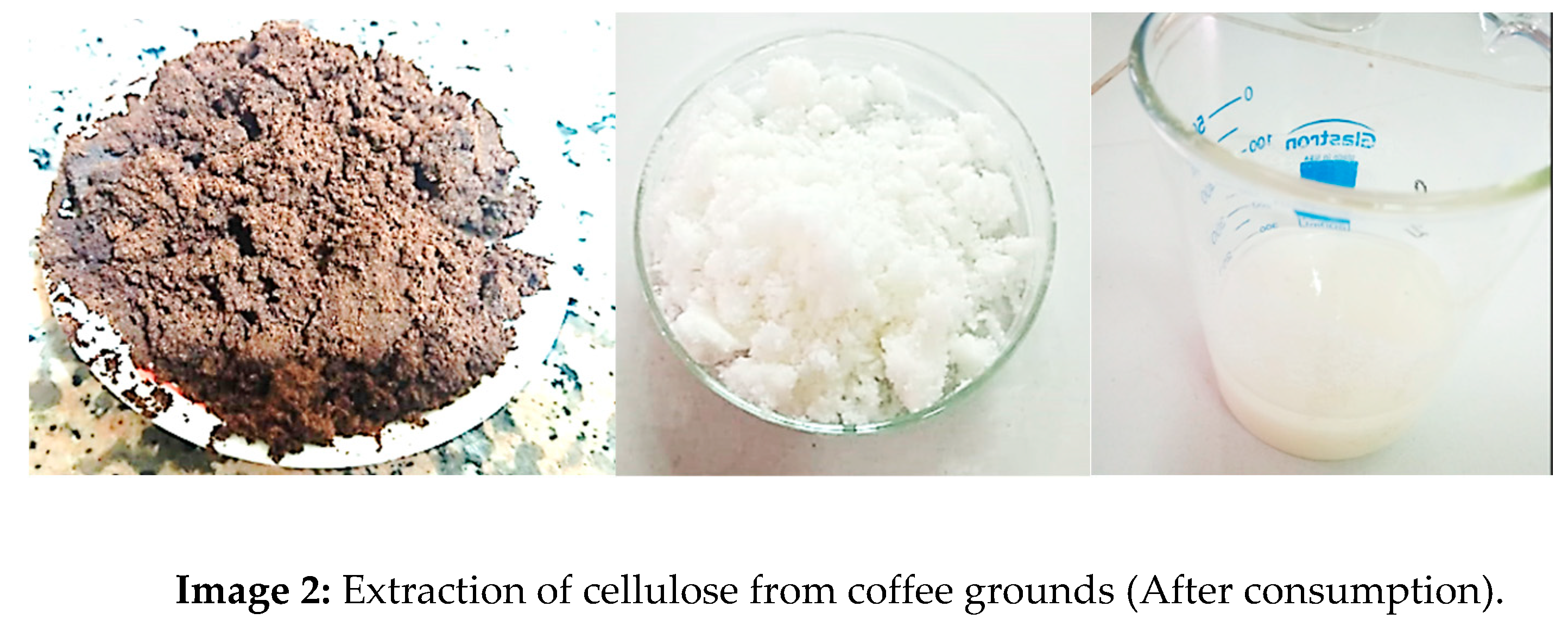

Cellulose Isolation: After undergoing the alkaline and bleaching processes, the material is transformed into fibrous pulp, primarily composed of purified cellulose (as illustrated in Img 2). This refined product is notable for its structural integrity and versatility, making it suitable for various applications such as bioplastics, paper manufacturing, and textiles. The effectiveness of the treatment ensures the removal of residual components like lignin and hemicelluloses, yielding a high-grade material ready for further use.

2.3. Oxidation of Cellulose Hydroxyl Groups:

The oxidation of cellulose hydroxyl groups is a critical step in modifying its chemical properties and enhancing its functionality. Traditionally, this process is performed using oxidizing agents, with sodium hypochlorite being widely utilized to convert hydroxyl groups into carboxylic acids.

In recent years, the use of oxoammonium salts, particularly the TEMPO (2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl) radical, has gained prominence due to its remarkable selectivity in oxidizing primary alcohols. Among the various systems developed, the TEMPO–NaOCl–NaBr combination stands out as one of the most efficient and thoroughly studied methods. This approach offers precise control over the oxidation process, ensuring minimal impact on secondary hydroxyl groups.

The reaction mechanism involves the consumption of two equivalents of sodium hypochlorite and is typically carried out at a pH range of 9.5–10.5 under ambient temperature conditions. This pH range is carefully maintained to optimize the reaction kinetics and prevent unwanted side reactions. The TEMPO-based system has become a benchmark in cellulose oxidation, paving the way for advanced applications in fields such as nanocellulose production, biomedicine, and sustainable materials development.

TEMPO Oxidation Process: The TEMPO oxidation process begins with adjusting the pH of the system to 10. A carefully prepared mixture containing sodium bromide (NaBr, 1.6 equivalents) and the TEMPO radical (0.0166 equivalents) is dissolved and introduced into the cellulose suspension (0.5 g). Subsequently, sodium hypochlorite (NaClO, 3.5 equivalents) is gradually added to the mixture to initiate the oxidation.

Throughout the reaction, the pH is closely monitored and maintained at 10.5 by the periodic addition of a 1 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution, ensuring optimal reaction conditions. The oxidation is allowed to proceed for 120 minutes, after which the reaction is terminated by adding 1.25 mL of methanol. The pH is then adjusted to neutral (pH 7) to stabilize the oxidized cellulose.

The oxidized pulp is subjected to centrifugation at 11,000 rpm for 30 minutes to separate the solid phase. The resulting material is then thoroughly washed with distilled water in three successive cycles to remove residual reactants and byproducts, yielding purified oxidized cellulose.

2.4. FTIR Analysis:

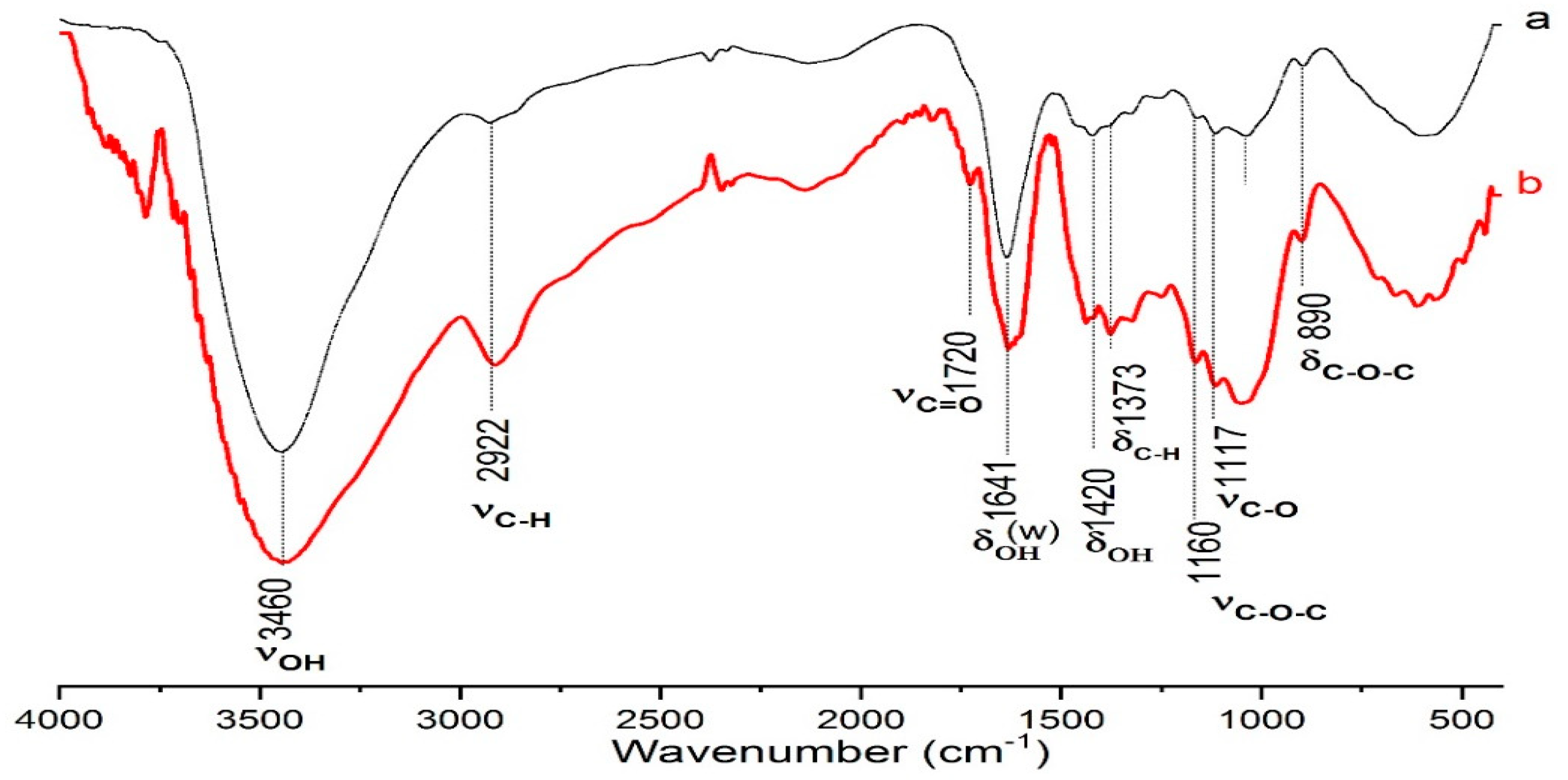

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was employed to characterize the surface functionalities of the modified cellulose. This technique enables the identification of functional groups introduced during the chemical modifications and surface reactions induced by the treatments.

Infrared (IR) spectra were recorded using a Bruker IFS 66 spectrophotometer, operating within a spectral range of 400–4000 cm⁻¹. The analysis utilized the KBr pellet technique, where 4 mg of the powdered cellulose sample was uniformly dispersed in 100 mg of potassium bromide (KBr), following the method described by Ouhammou et al. (2022).

This approach provided detailed insights into the structural changes occurring on the cellulose surface, particularly those resulting from oxidation and other chemical transformations. The observed spectral shifts and peak intensities (

Figure 1) offered a clear indication of the functional groups introduced during the treatments, confirming the effectiveness of the chemical modifications.

2.5. Analysis by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Coupled with an EDX Probe:

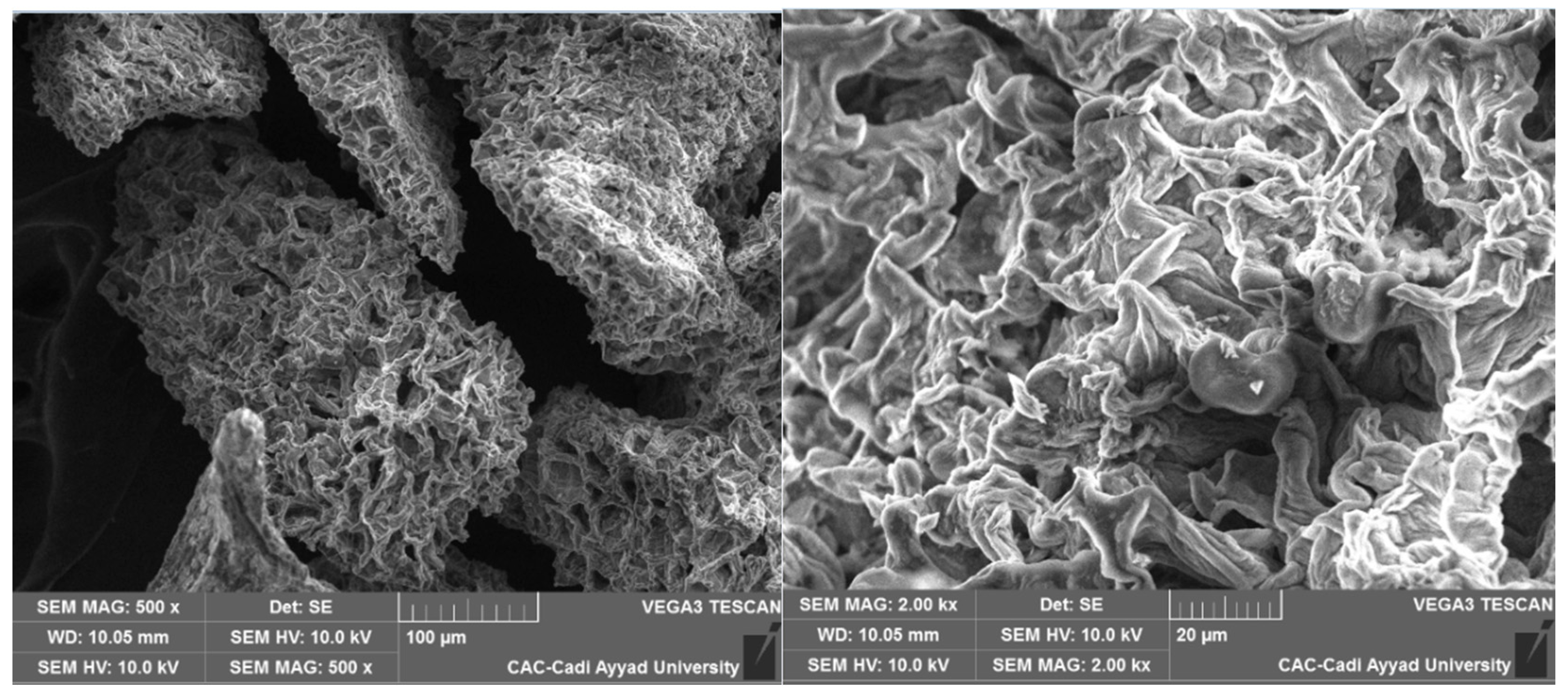

The microstructure of the modified cellulose was examined using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (TES-CAN VEGA 3) at the Analysis and Characterization Center of the Faculty of Sciences, Semlalia, Cadi Ayyad University. Prior to analysis, the sample was coated with a thin layer of carbon to enhance conductivity. SEM images were captured at various magnifications, with an acceleration voltage set to 10 kV, allowing for high-resolution imaging of the surface morphology (

Figure 2).

Figure 2.

SEM image of coffee grounds cellulose before oxidation by the TEMPO/NaBr system.

Figure 2.

SEM image of coffee grounds cellulose before oxidation by the TEMPO/NaBr system.

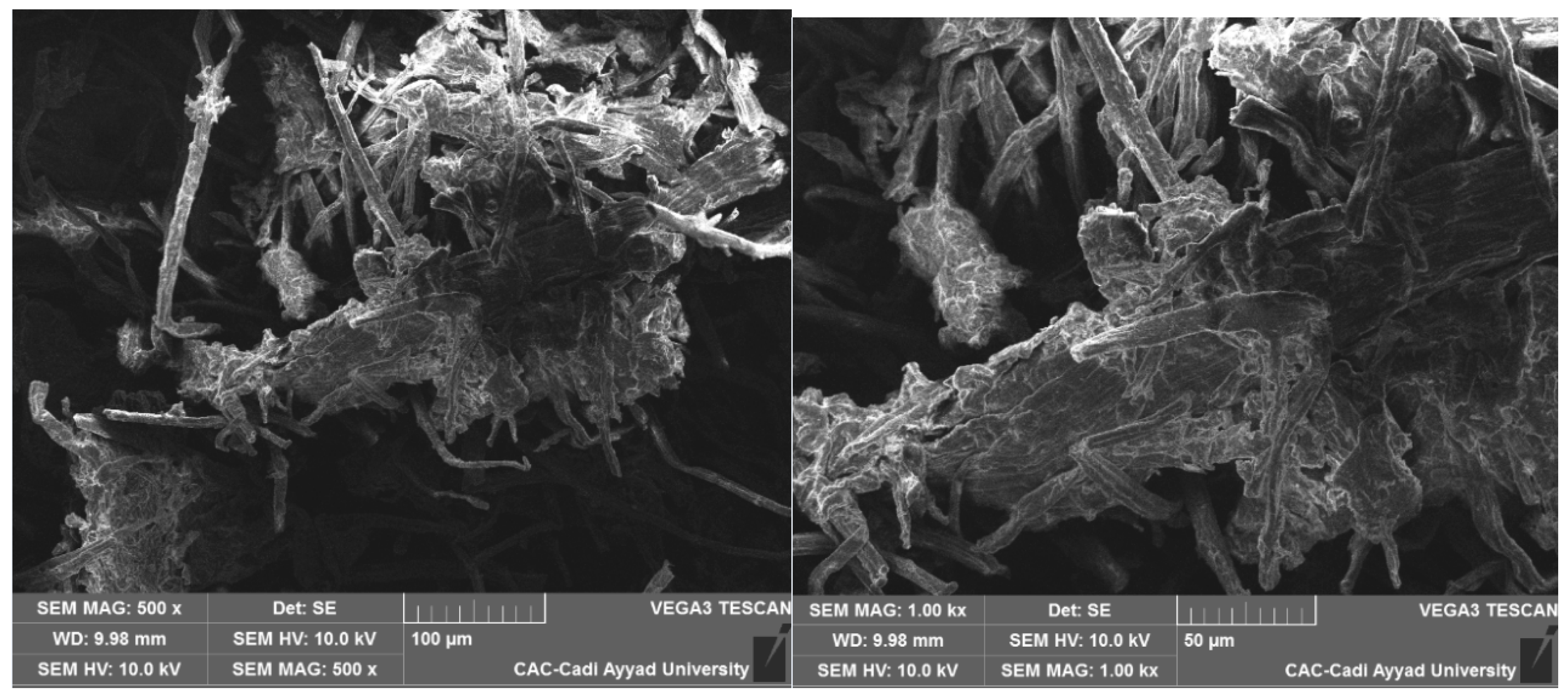

Figure 3.

SEM image of coffee grounds cellulose after oxidation by the TEMPO/NaBr system.

Figure 3.

SEM image of coffee grounds cellulose after oxidation by the TEMPO/NaBr system.

In addition to the morphological examination, energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy was employed to analyze the elemental composition of the sample, providing further insights into the surface characteristics and the presence of any chemical modifications.

3. Results and Discussion:

In summary, the oxidation of cellulose using sodium bromide (NaBr) and the TEMPO radical is a catalytic process that transforms cellulose into TEMPO-oxidized cellulose (TEMPOxy). This modification enhances the cellulose's properties, making it more suitable for a broad spectrum of industrial and biomaterial applications. The TEMPO-mediated oxidation process not only improves the chemical reactivity of cellulose but also facilitates its integration into advanced materials, such as biocomposites, nanocellulose, and sustainable packaging solutions. These improvements in cellulose functionality open new possibilities for its use in various fields, including environmental and medical applications [

21,

22,

23].

3.1. Infrared Spectroscopy (IR):

Infrared (IR) spectroscopy provides valuable insights into the chemical structural changes of cellulose during oxidation, allowing for a detailed comparison of the biomass before and after treatment. The analysis identifies key infrared absorption bands, each corresponding to specific functional groups present in the cellulose. The following sections highlight the primary IR bands observed in the spectra, along with the functional groups they represent, both prior to and following the oxidation process (see figure below).

The spectra of oxidized cellulose (b) show the appearance of an additional band around 1720 cm⁻¹, which is absent in the spectrum of native cellulose (a) (-OH). This band is attributed to the carbonyl group (C=O), characteristic of carboxyl groups (-COOH). It serves as a key marker for the oxidation of cellulose into carboxymethylcellulose or other carboxyl-containing structures. This result confirms the successful modification of the cellulose substrate, in line with previous studies in the literature [

19,

20].

However, the band at 1641 cm⁻¹, corresponding to the OH bonds of water adsorbed on the cellulose, appears very broad. This is likely due to the presence of residual moisture, which is a common challenge when drying samples prior to chemical treatment [

19,

20].

Changes in the C-O band observed between 1050-1100 cm⁻¹ may suggest structural modifications of the cellulose, indicating the introduction of additional functional groups. These changes can influence the crystallinity and solubility of the modified cellulose.

Additionally, the C-O-C absorption band at 1160 cm⁻¹ may shift or become more intense as hydroxyl groups are converted into carboxyl groups or other oxygenated structures.

A decrease in the intensity of the O-H band at 3460 cm⁻¹ is also noted, reflecting the transformation of hydroxyl groups into other functional groups during the oxidation process.

3.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM):

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) is an effective technique for analyzing material morphology and structure following chemical modifications. After the oxidation of coffee ground cellulose using the TEMPO/NaBr system, notable changes in surface roughness and topography were observed. These changes result from the introduction of functional groups, particularly carboxyl groups, which enhance the cellulose’s properties.

Such modifications improve the cellulose's ability to bond with other materials, facilitating the creation of advanced composites. Additionally, the increased surface roughness may enhance moisture retention, making the modified cellulose suitable for applications in biocomposites, packaging, and water filtration [

21,

22,

23].

SEM can be used to observe changes in the particle size and distribution of nanostructures. The SEM images reveal that the fibrous structure of coffee ground cellulose is significantly altered after oxidation. This refinement occurs when cellulose undergoes oxidation using the TEMPO/NaBr system, leading to a more fragile structure with broken or fragmented morphologies. If the oxidation is intense, partial depolymerization of the cellulose chains occurs, resulting in a reduction in fiber size and the formation of nanocellulose. This nanocellulose exhibits enhanced properties, such as an increased specific surface area, greater hydrophilicity, and improved chemical reactivity [

19,

20].

3.3. Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX):

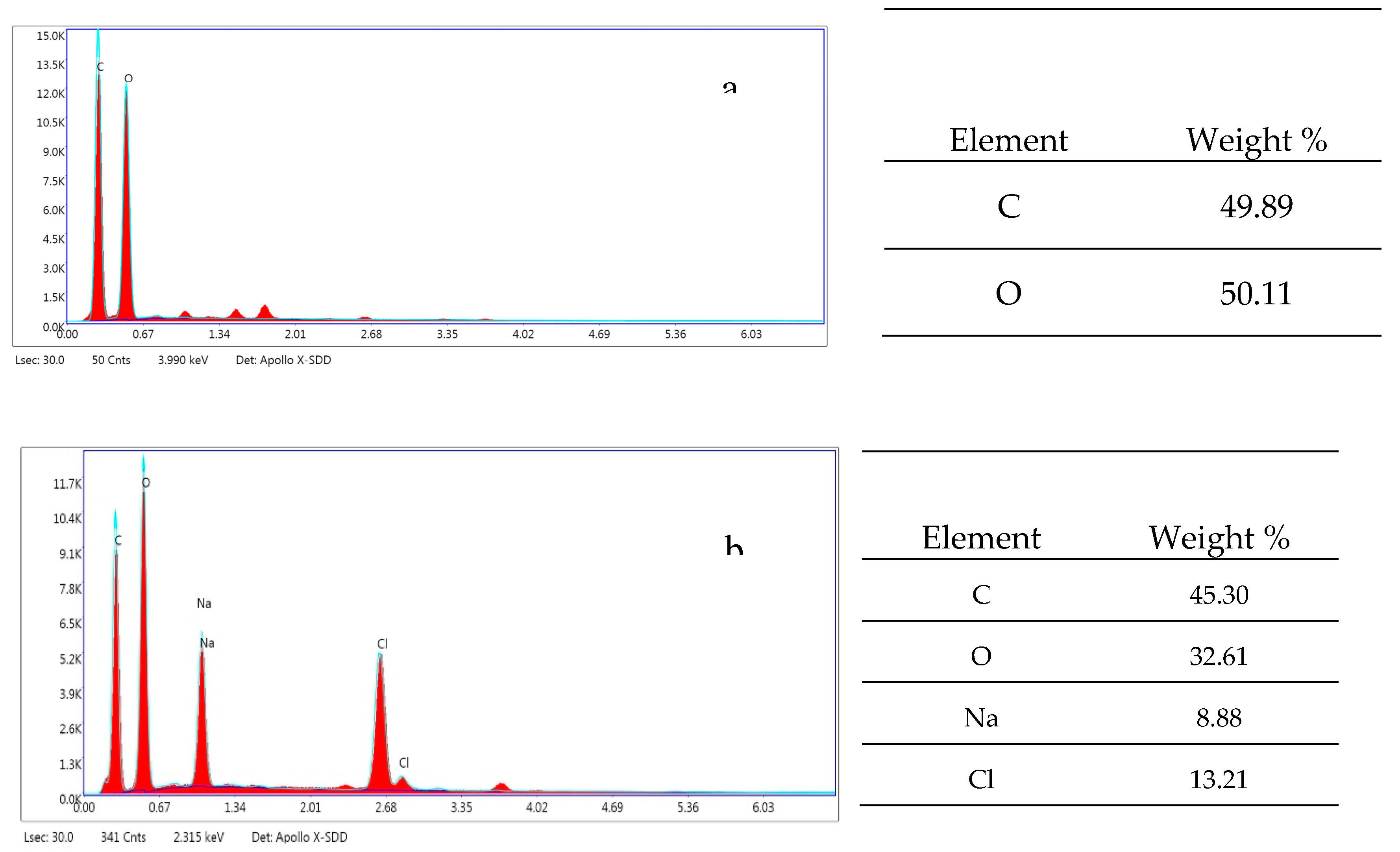

Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX) provides a detailed analysis of the elemental composition of a sample's surface. When coupled with Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), EDX allows for the precise localization and quantification of chemical elements in specific regions of interest. This technique was used to analyze the cellulose before and after oxidation with the TEMPO/NaBr system, as illustrated in the figure below.

Figure 4.

EDX spectrum of cellulose before and after oxidation by the TEMPO/NaBr system.

Figure 4.

EDX spectrum of cellulose before and after oxidation by the TEMPO/NaBr system.

The following elements were detected: carbon and oxygen, with oxygen being particularly abundant in the cellulose. This increase in oxygen content indicates a chemical modification that alters the solubility, hydrophilicity, and chemical reactivity of the cellulose.

The oxidation process induced by TEMPO and NaBr leads to the formation of functional groups, such as carboxylates (-COOH), resulting in a modified carbon-to-oxygen ratio. Furthermore, the EDX spectra revealed the presence of impurities and secondary products from the chemical reaction, as well as non-carbonized oxidized products.