Submitted:

19 December 2024

Posted:

21 December 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Enzymatic Oxidants, Antioxidants, and Inflammatory Bowel Disease

3. The Main Players

3. Finding Overlapping Roles of GPX1 and GPX2 in the Intestine by Peeling Back the Layers of Antioxidants

4. Any application to IBD?

5. Low Selenium Levels in IBD

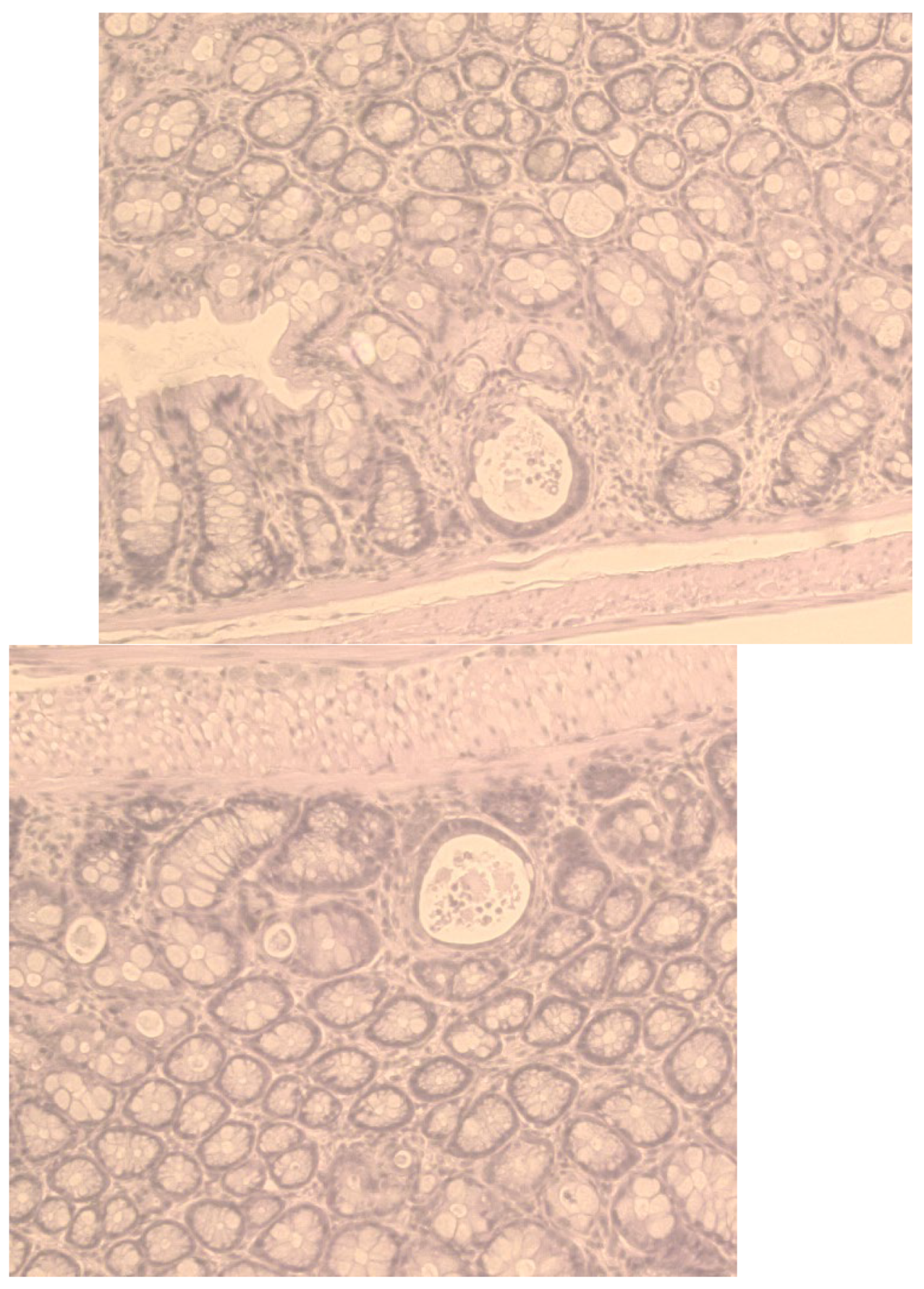

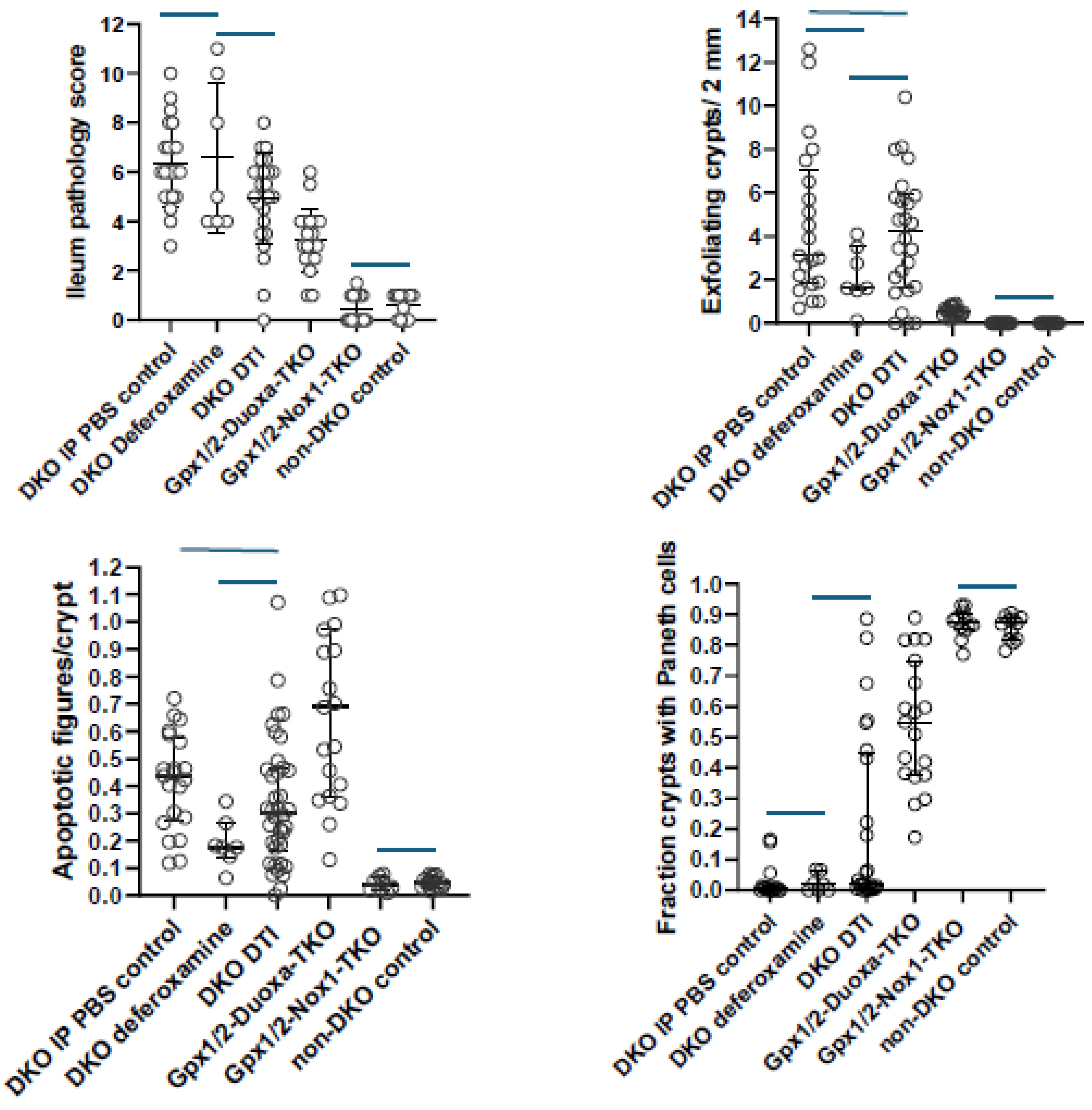

6. NADPH Oxidases and Pathology in Gpx1/2-DKO Mice and Normal Function in Wild Type Mice

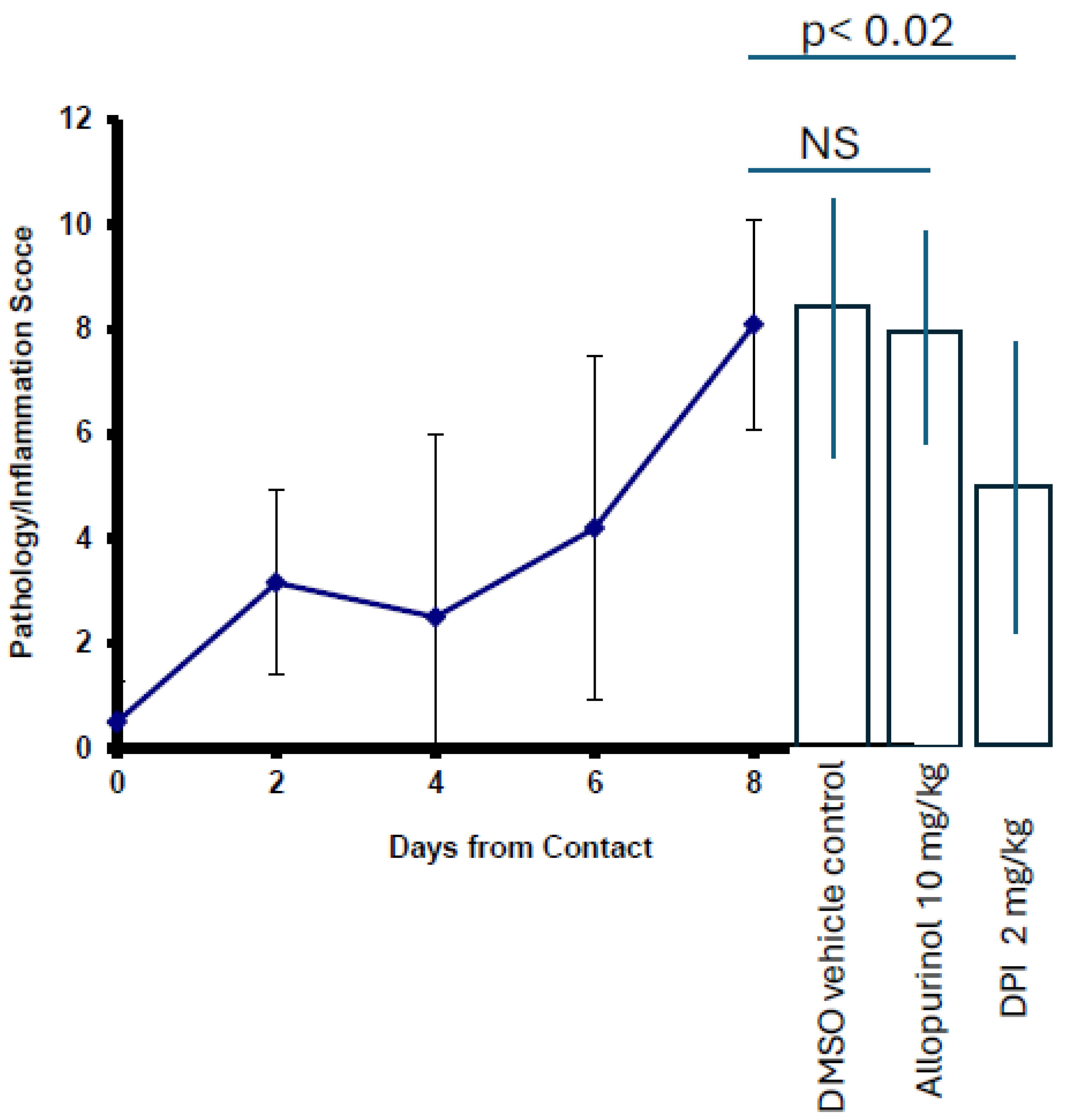

7. Other Sources of Oxidants

8. Ferroptosis, the 800-Pound Gorilla in the Room

9. Use of Markers for Identifying Ferroptosis

10. Concluding Remarks: Ferroptosis in IBD

11. Concluding Remarks: Oxidative Stress in IBD

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

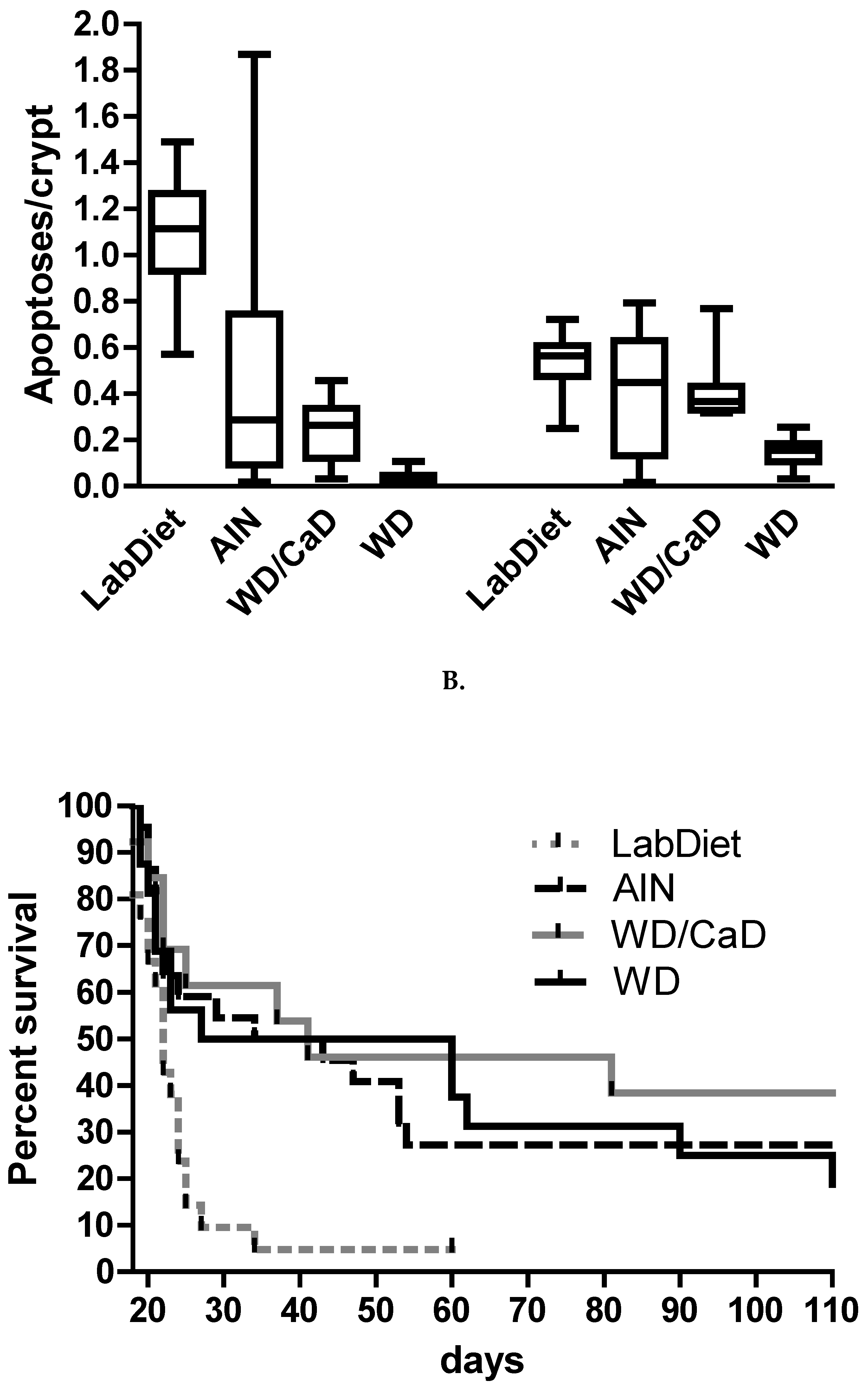

- Chu FF, Esworthy RS, Doroshow JH, Grasberger H, Donko A, Leto TL, Gao Q, Shen B. Deficiency in Duox2 activity alleviates ileitis in GPx1- and GPx2-knockout mice without affecting apoptosis incidence in the crypt epithelium. Redox Biol. 2017 Apr;11:144-156. Epub 2016 Nov 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chu FF, Esworthy RS, Shen B, Gao Q, Doroshow JH. Dexamethasone and Tofacitinib suppress NADPH oxidase expression and alleviate very-early-onset ileocolitis in mice deficient in GSH peroxidase 1 and 2. Life Sci. 2019 Dec 15;239:116884. Epub 2019 Nov 2. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Meulmeester FL, Luo J, Martens LG, Mills K, van Heemst D, Noordam R. Antioxidant Supplementation in Oxidative Stress-Related Diseases: What Have We Learned from Studies on Alpha-Tocopherol? Antioxidants (Basel). 2022 Nov 24;11(12):2322. doi: 10.3390/antiox11122322. PMID: 36552530; PMCID: PMC9774512; Myung SK, Kim Y, Ju W, Choi HJ, Bae WK. Effects of antioxidant supplements on cancer prevention: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Oncol. 2010 Jan;21(1):166-79. Epub 2009 Jul 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Gluud LL, Simonetti RG, Gluud C. Antioxidant supplements for prevention of mortality in healthy participants and patients with various diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Mar 14;2012(3):CD007176. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xavier LEMDS, Reis TCG, Martins ASDP, Santos JCF, Bueno NB, Goulart MOF, Moura FA. Antioxidant Therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: How Far Have We Come and How Close Are We? Antioxidants (Basel). 2024 Nov 8;13(11):1369. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hendrickson BA, Gokhale R, Cho JH. Clinical aspects and pathophysiology of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002 Jan;15(1):79-94. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.1.79-94.2002. PMID: 11781268; PMCID: PMC118061 Baumgart DC, Carding SR. Inflammatory bowel disease: cause and immunobiology. Lancet. 2007 May 12;369(9573):1627-40. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strober W, Fuss I, Mannon P. The fundamental basis of inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Invest. 2007 Mar;117(3):514-21. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wen Z, Fiocchi C. Inflammatory bowel disease: autoimmune or immune-mediated pathogenesis? Clin Dev Immunol. 2004 Sep-Dec;11(3-4):195-204. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Knight-Sepulveda K, Kais S, Santaolalla R, Abreu MT. Diet and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2015 Aug;11(8):511-20. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gordon H, Trier Moller F, Andersen V, Harbord M. Heritability in inflammatory bowel disease: from the first twin study to genome-wide association studies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015 Jun;21(6):1428-34. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Eckmann L, Karin M. NOD2 and Crohn's disease: loss or gain of function? Immunity. 2005 Jun;22(6):661-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana PT, Rosas SLB, Ribeiro BE, Marinho Y, de Souza HSP. Dysbiosis in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Pathogenic Role and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Mar 23;23(7):3464. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kuenzig ME, Manuel DG, Donelle J, Benchimol EI. Life expectancy and health-adjusted life expectancy in people with inflammatory bowel disease. CMAJ. 2020 Nov 9;192(45):E1394-E1402. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Laredo V, García-Mateo S, Martínez-Domínguez SJ, López de la Cruz J, Gargallo-Puyuelo CJ, Gomollón F. Risk of Cancer in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and Keys for Patient Management. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Jan 31;15(3):871. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mitropoulou MA, Fradelos EC, Lee KY, Malli F, Tsaras K, Christodoulou NG, Papathanasiou IV. Quality of Life in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Importance of Psychological Symptoms. Cureus. 2022 Aug 28;14(8):e28502. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aniwan S, Santiago P, Loftus EV Jr, Park SH. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia and Asian immigrants to Western countries. United European Gastroenterol J. 2022 Dec;10(10):1063-1076. Epub 2022 Dec 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dharni K, Singh A, Sharma S, Midha V, Kaur K, Mahajan R, Dulai PS, Sood A. Trends of inflammatory bowel disease from the Global Burden of Disease Study (1990-2019). Indian J Gastroenterol. 2024 Feb;43(1):188-198. Epub 2023 Oct 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loew, O. A NEW ENZYME OF GENERAL OCCURRENCE IN ORGANISMIS. Science. 1900 May 4;11(279):701-2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang J, Jin J, Jeon S, Moon SH, Park MY, Yum DY, Kim JH, Kang JE, Park MH, Kim EJ, Pan JG, Kwon O, Oh GT. SOD1 suppresses pro-inflammatory immune responses by protecting against oxidative stress in colitis. Redox Biol. 2020 Oct;37:101760. Epub 2020 Oct 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- O'Morain C, Smethurst P, Levi AJ, Peters TJ. Organelle pathology in ulcerative and Crohn's colitis with special reference to the lysosomal alterations. Gut. 1984 May;25(5):455-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- MILLS GC. Hemoglobin catabolism. I. Glutathione peroxidase, an erythrocyte enzyme which protects hemoglobin from oxidative breakdown. J Biol Chem. 1957 Nov;229(1):189-97. PMID. [PubMed]

- McCord JM, Fridovich I. The utility of superoxide dismutase in studying free radical reactions. I. Radicals generated by the interaction of sulfite, dimethyl sulfoxide, and oxygen. J Biol Chem. 1969 Nov 25;244(22):6056-63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emerit J, Loeper J, Chomette G. Superoxide dismutase in the treatment of post-radiotherapeutic necrosis and of Crohn's disease. Bull Eur Physiopathol Respir. 1981;17 Suppl:287. [PubMed]

- Petkau, A. Scientific basis for the clinical use of superoxide dismutase. Cancer Treat Rev. 1986 Mar;13(1):17-44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahnfelt-Rønne I, Nielsen OH. The antiinflammatory moiety of sulfasalazine, 5-aminosalicylic acid, is a radical scavenger. Agents Actions. 1987 Jun;21(1-2):191-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grisham MB, MacDermott RP, Deitch EA. Oxidant defense mechanisms in the human colon. Inflammation. 1990 Dec;14(6):669-80. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming CR, McCall JT, O'Brien JF, Forsman RW, Ilstrup DM, Petz J. Selenium status in patients receiving home parenteral nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1984 May-Jun;8(3):258-62. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotruck JT, Pope AL, Ganther HE, Swanson AB, Hafeman DG, Hoekstra WG. Selenium: biochemical role as a component of glutathione peroxidase. Science. 1973 Feb 9;179(4073):588-90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penny WJ, Mayberry JF, Aggett PJ, Gilbert JO, Newcombe RG, Rhodes J. Relationship between trace elements, sugar consumption, and taste in Crohn's disease. Gut. 1983 Apr;24(4):288-92. doi: 10.1136/gut.24.4.288. PMID: 6832625; PMCID: PMC1419969. Harries AD, Heatley RV. Nutritional disturbances in Crohn's disease. Postgrad Med J. 1983 Nov;59(697):690-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barrett CW, Singh K, Motley AK, Lintel MK, Matafonova E, Bradley AM, Ning W, Poindexter SV, Parang B, Reddy VK, Chaturvedi R, Fingleton BM, Washington MK, Wilson KT, Davies SS, Hill KE, Burk RF, Williams CS. Dietary selenium deficiency exacerbates DSS-induced epithelial injury and AOM/DSS-induced tumorigenesis. PLoS One. 2013 Jul 4;8(7):e67845. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sang L, Chang B, Zhu J, Yang F, Li Y, Jiang X, Sun X, Lu C, Wang D. Dextran sulfate sodium-induced acute experimental colitis in C57BL/6 mice is mitigated by selenium. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016 Oct;39:359-368. Epub 2016 Aug 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider T, Caviezel D, Ayata CK, Kiss C, Niess JH, Hruz P. The Copper/Zinc Ratio Correlates With Markers of Disease Activity in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Crohns Colitis 360. 2020 Jan;2(1):otaa001. Epub 2020 Jan 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Amerikanou C, Karavoltsos S, Gioxari A, Tagkouli D, Sakellari A, Papada E, Kalogeropoulos N, Forbes A, Kaliora AC. Clinical and inflammatory biomarkers of inflammatory bowel diseases are linked to plasma trace elements and toxic metals; new insights into an old concept. Front Nutr. 2022 Dec 8;9:997356. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tian T, Wang Z, Zhang J. Pathomechanisms of Oxidative Stress in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Potential Antioxidant Therapies. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:4535194. Epub 2017 Jun 28. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Paschall M, Seo YA, Choi EK. Low Dietary Manganese Levels Exacerbate Experimental Colitis in Mice. Curr Dev Nutr. 2020 May 29;4(Suppl 2):1831. [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Choi EK, Aring L, Das NK, Solanki S, Inohara N, Iwase S, Samuelson LC, Shah YM, Seo YA. Impact of dietary manganese on experimental colitis in mice. FASEB J. 2020 Feb;34(2):2929-2943. Epub 2019 Dec 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kruidenier L, Kuiper I, van Duijn W, Marklund SL, van Hogezand RA, Lamers CB, Verspaget HW. Differential mucosal expression of three superoxide dismutase isoforms in inflammatory bowel disease. J Pathol. 2003 Sep;201(1):7-16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen OH, Ainsworth M, Coskun M, Weiss G. Management of Iron-Deficiency Anemia in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015 Jun;94(23):e963. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Besgen P, Trommler P, Vollmer S, Prinz JC. Ezrin, maspin, peroxiredoxin 2, and heat shock protein 27: potential targets of a streptococcal-induced autoimmune response in psoriasis. J Immunol. 2010 May 1;184(9):5392-402. Epub 2010 Apr 2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, YJ. Knockout Mouse Models for Peroxiredoxins. Antioxidants (Basel). 2020 Feb 22;9(2):182. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Esworthy, R.S.; Chu, F.-F. Using Information from Public Databases to Critically Evaluate Studies Linking the Antioxidant Enzyme Selenium-Dependent Glutathione Peroxidase 2 (GPX2) to Cancer. BioMedInformatics 2023, 3, 985-1014. [CrossRef]

- Hoehne MN, Spatial and temporal control of mitochondrial H2O2 release in intact human cells. EMBO J. 2022 Apr 4;41(7):e109169. Epub 2022 Feb 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pace PE, Fu L, Hampton MB, Winterbourn CC. Effect of peroxiredoxin 1 or peroxiredoxin 2 knockout on the thiol proteome of Jurkat cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2024 Oct 18;225:595-604. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun Y, Qiao Y, Liu Y, Zhou J, Wang X, Zheng H, Xu Z, Zhang J, Zhou Y, Qian L, Zhang C, Lou H. ent-Kaurane diterpenoids induce apoptosis and ferroptosis through targeting redox resetting to overcome cisplatin resistance. Redox Biol. 2021 Jul;43:101977. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2021.101977. Epub 2021 Apr 16. Erratum in: Redox Biol. 2024 Jun;72:103164. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Thapa, P, Jiang H, Ding N, Hao Y, Alshahrani A, Lee EY, Fujii J, Wei Q. Loss of Peroxiredoxin IV Protects Mice from Azoxymethane/Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colorectal Cancer Development. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023 Mar 9;12(3):677. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Esworthy RS, Aranda R, Martín MG, Doroshow JH, Binder SW, Chu FF. Mice with combined disruption of Gpx1 and Gpx2 genes have colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001 Sep;281(3):G848-55. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Remmen H, Williams MD, Guo Z, Estlack L, Yang H, Carlson EJ, Epstein CJ, Huang TT, Richardson A. Knockout mice heterozygous for Sod2 show alterations in cardiac mitochondrial function and apoptosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001 Sep;281(3):H1422-32. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Irigoyen O, Bovenga F, Piglionica M, Piccinin E, Cariello M, Arconzo M, Peres C, Corsetto PA, Rizzo AM, Ballanti M, Menghini R, Mingrone G, Lefebvre P, Staels B, Shirasawa T, Sabbà C, Villani G, Federici M, Moschetta A. Enterocyte superoxide dismutase 2 deletion drives obesity. iScience. 2021 Dec 27;25(1):103707. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brand MD, Affourtit C, Esteves TC, Green K, Lambert AJ, Miwa S, Pakay JL, Parker N. Mitochondrial superoxide: production, biological effects, and activation of uncoupling proteins. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004 Sep 15;37(6):755-67. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crapo JD, McCord JM. Oxygen-induced changes in pulmonary superoxide dismutase assayed by antibody titrations. Am J Physiol. 1976 Oct;231(4):1196-203. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bize IB, Oberley LW, Morris HP. Superoxide dismutase and superoxide radical in Morris hepatomas. Cancer Res. 1980 Oct;40(10):3686-93. [PubMed]

- Keyer K, Gort AS, Imlay JA. Superoxide and the production of oxidative DNA damage. J Bacteriol. 1995 Dec;177(23):6782-90. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim BW, Esworthy RS, Hahn MA, Pfeifer GP, Chu FF. Expression of lactoperoxidase in differentiated mouse colon epithelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012 May 1;52(9):1569-76. Epub 2012 Feb 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Antunes F, Brito PM. Quantitative biology of hydrogen peroxide signaling. Redox Biol. 2017 Oct;13:1-7. Epub 2017 May 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Winterbourn, CC. The biological chemistry of hydrogen peroxide. Methods Enzymol. 2013;528:3-25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won HY, Sohn JH, Min HJ, Lee K, Woo HA, Ho YS, Park JW, Rhee SG, Hwang ES. Glutathione peroxidase 1 deficiency attenuates allergen-induced airway inflammation by suppressing Th2 and Th17 cell development. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010 Sep 1;13(5):575-87. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dittrich AM, Meyer HA, Krokowski M, Quarcoo D, Ahrens B, Kube SM, Witzenrath M, Esworthy RS, Chu FF, Hamelmann E. Glutathione peroxidase-2 protects from allergen-induced airway inflammation in mice. Eur Respir J. 2010 May;35(5):1148-54. Epub 2009 Nov 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim HR, Lee A, Choi EJ, Kie JH, Lim W, Lee HK, Moon BI, Seoh JY. Attenuation of experimental colitis in glutathione peroxidase 1 and catalase double knockout mice through enhancing regulatory T cell function. PLoS One. 2014 Apr 17;9(4):e95332. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hu R, Xiao J, Fan L. The Role of the Trace Element Selenium in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2024 Nov;202(11):4923-4931. Epub 2024 Feb 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kryukov GV, Castellano S, Novoselov SV, Lobanov AV, Zehtab O, Guigó R, Gladyshev VN. Characterization of mammalian selenoproteomes. Science. 2003 May 30;300(5624):1439-43. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touat-Hamici Z, Bulteau AL, Bianga J, Jean-Jacques H, Szpunar J, Lobinski R, Chavatte L. Selenium-regulated hierarchy of human selenoproteome in cancerous and immortalized cells lines. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2018 Nov;1862(11):2493-2505. Epub 2018 Apr 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ocansey DKW, Yuan J, Wei Z, Mao F, Zhang Z. Role of ferroptosis in the pathogenesis and as a therapeutic target of inflammatory bowel disease (Review). Int J Mol Med. 2023 Jun;51(6):53. Epub 2023 May 19. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Takashima H, Toyama T, Mishima E, Ishida K, Wang Y, Ichikawa A, Ito J, Yogiashi S, Siu S, Sugawara M, Shiina S, Arisawa K, Conrad M, Saito Y. Impact of selenium content in fetal bovine serum on ferroptosis susceptibility and selenoprotein expression in cultured cells. J Toxicol Sci. 2024;49(12):555-563. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang WS, SriRamaratnam R, Welsch ME, Shimada K, Skouta R, Viswanathan VS, Cheah JH, Clemons PA, Shamji AF, Clish CB, Brown LM, Girotti AW, Cornish VW, Schreiber SL, Stockwell BR. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell. 2014 Jan 16;156(1-2):317-331. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chu FF, Doroshow JH, Esworthy RS. Expression, characterization, and tissue distribution of a new cellular selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidase, GSHPx-GI. J Biol Chem. 1993 Feb 5;268(4):2571-6. [PubMed]

- Esworthy RS, Mann JR, Sam M, Chu FF. Low glutathione peroxidase activity in Gpx1 knockout mice protects jejunum crypts from gamma-irradiation damage. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000 Aug;279(2):G426-36. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu FF, Esworthy RS. The expression of an intestinal form of glutathione peroxidase (GSHPx-GI) in rat intestinal epithelium. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995 Nov 10;323(2):288-94. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kannan N, Nguyen LV, Makarem M, Dong Y, Shih K, Eirew P, Raouf A, Emerman JT, Eaves CJ. Glutathione-dependent and -independent oxidative stress-control mechanisms distinguish normal human mammary epithelial cell subsets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014 May 27;111(21):7789-94. Epub 2014 May 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Esworthy RS, Swiderek KM, Ho YS, Chu FF. Selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidase-GI is a major glutathione peroxidase activity in the mucosal epithelium of rodent intestine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998 Jul 23;1381(2):213-26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tham DM, Whitin JC, Kim KK, Zhu SX, Cohen HJ. Expression of extracellular glutathione peroxidase in human and mouse gastrointestinal tract. Am J Physiol. 1998 Dec;275(6):G1463-71. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speckmann B, Bidmon HJ, Pinto A, Anlauf M, Sies H, Steinbrenner H. Induction of glutathione peroxidase 4 expression during enterocytic cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2011 Mar 25;286(12):10764-72. Epub 2011 Jan 20. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cohn SM, Schloemann S, Tessner T, Seibert K, Stenson WF. Crypt stem cell survival in the mouse intestinal epithelium is regulated by prostaglandins synthesized through cyclooxygenase 1. J Clin Invest. 1997 Mar 15;99(6):1367-79. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Koeberle SC, Gollowitzer A, Laoukili J, Kranenburg O, Werz O, Koeberle A, Kipp AP. Distinct and overlapping functions of glutathione peroxidases 1 and 2 in limiting NF-κB-driven inflammation through redox-active mechanisms. Redox Biol. 2020 Jan;28:101388. Epub 2019 Nov 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Banning A, Florian S, Deubel S, Thalmann S, Müller-Schmehl K, Jacobasch G, Brigelius-Flohé R. GPx2 counteracts PGE2 production by dampening COX-2 and mPGES-1 expression in human colon cancer cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008 Sep;10(9):1491-500. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capdevila JH, Morrow JD, Belosludtsev YY, Beauchamp DR, DuBois RN, Falck JR. The catalytic outcomes of the constitutive and the mitogen inducible isoforms of prostaglandin H2 synthase are markedly affected by glutathione and glutathione peroxidase(s). Biochemistry. 1995 Mar 14;34(10):3325-37. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulmacz RJ, Wang LH. Comparison of hydroperoxide initiator requirements for the cyclooxygenase activities of prostaglandin H synthase-1 and -2. J Biol Chem. 1995 Oct 13;270(41):24019-23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu FF, Esworthy RS, Doroshow JH. Role of Se-dependent glutathione peroxidases in gastrointestinal inflammation and cancer. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004 Jun 15;36(12):1481-95. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood ZA, Poole LB, Karplus PA. Peroxiredoxin evolution and the regulation of hydrogen peroxide signaling. Science. 2003 Apr 25;300(5619):650-3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- COHEN G, HOCHSTEIN P. GLUTATHIONE PEROXIDASE: THE PRIMARY AGENT FOR THE ELIMINATION OF HYDROGEN PEROXIDE IN ERYTHROCYTES. Biochemistry. 1963 Nov-Dec;2:1420-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu FF, Esworthy RS, Chu PG, Longmate JA, Huycke MM, Wilczynski S, Doroshow JH. Bacteria-induced intestinal cancer in mice with disrupted Gpx1 and Gpx2 genes. Cancer Res. 2004 Feb 1;64(3):962-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talmon G, Manasek T, Miller R, Muirhead D, Lazenby A. The Apoptotic Crypt Abscess: An Underappreciated Histologic Finding in Gastrointestinal Pathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2017 Nov 20;148(6):538-544. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esworthy RS, Kim BW, Chow J, Shen B, Doroshow JH, Chu FF. Nox1 causes ileocolitis in mice deficient in glutathione peroxidase-1 and -2. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014 Mar;68:315-25. Epub 2013 Dec 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Williams JM, Duckworth CA, Burkitt MD, Watson AJ, Campbell BJ, Pritchard DM. Epithelial cell shedding and barrier function: a matter of life and death at the small intestinal villus tip. Vet Pathol. 2015 May;52(3):445-55. Epub 2014 Nov 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kiesslich R, Duckworth CA, Moussata D, Gloeckner A, Lim LG, Goetz M, Pritchard DM, Galle PR, Neurath MF, Watson AJ. Local barrier dysfunction identified by confocal laser endomicroscopy predicts relapse in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2012 Aug;61(8):1146-53. Epub 2011 Nov 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Turcotte JF, Wong K, Mah SJ, Dieleman LA, Kao D, Kroeker K, Claggett B, Saltzman JR, Wine E, Fedorak RN, Liu JJ. Increased epithelial gaps in the small intestine are predictive of hospitalization and surgery in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2012 Jul 26;3(7):e19. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Esworthy RS, Yang L, Frankel PH, Chu FF. Epithelium-specific glutathione peroxidase, Gpx2, is involved in the prevention of intestinal inflammation in selenium-deficient mice. J Nutr. 2005 Apr;135(4):740-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto MA, Lopes MS, Bastos ST, Reigada CL, Dantas RF, Neto JC, Luna AS, Madi K, Nunes T, Zaltman C. Does active Crohn's disease have decreased intestinal antioxidant capacity? J Crohns Colitis. 2013 Oct;7(9):e358-66. Epub 2013 Mar 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi J, Ji S, Xu M, Wang Y, Shi H. Selenium inhibits ferroptosis in ulcerative colitis through the induction of Nrf2/Gpx4. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2024 Sep 21;48(9):102467. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros SÉL, Dias TMDS, Moura MSB, Soares NRM, Pierote NRA, Araújo COD, Maia CSC, Henriques GS, Barros VC, Moita Neto JM, Parente JML, Marreiro DDN, Nogueira NDN. Relationship between selenium status and biomarkers of oxidative stress in Crohn's disease. Nutrition. 2020 Jun;74:110762. Epub 2020 Feb 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalcarz M, Grabarek BO, Sirek T, Sirek A, Ossowski P, Wilk M, Król-Jatręga K, Dziobek K, Gajdeczka J, Madowicz J, Strojny D, Boroń K, Żurawski J. Evaluation of Selenium Concentrations in Patients with Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. Biomedicines. 2024 Sep 24;12(10):2167. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu S, Lin T, Wang W, Jing F, Sheng J. Selenium deficiency in inflammatory bowel disease: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Heliyon. 2024 Nov 5;10(22):e40139. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alfthan G, Xu GL, Tan WH, Aro A, Wu J, Yang YX, Liang WS, Xue WL, Kong LH. Selenium supplementation of children in a selenium-deficient area in China: blood selenium levels and glutathione peroxidase activities. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2000 Feb;73(2):113-25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia YM, Hill KE, Burk RF. Biochemical studies of a selenium-deficient population in China: measurement of selenium, glutathione peroxidase and other oxidant defense indices in blood. J Nutr. 1989 Sep;119(9):1318-26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combs, G.F., Jr. Biomarkers of selenium status. Nutrients 2015, 7, 2209–2236. [CrossRef]

- Beck MA, Esworthy RS, Ho YS, Chu FF. Glutathione peroxidase protects mice from viral-induced myocarditis. FASEB J. 1998 Sep;12(12):1143-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis C, Javid PJ, Horslen S. Selenium deficiency in pediatric patients with intestinal failure as a consequence of drug shortage. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014 Jan;38(1):115-8. Epub 2013 Apr 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur R, Thakur S, Rastogi P, Kaushal N. Resolution of Cox mediated inflammation by Se supplementation in mouse experimental model of colitis. PLoS One. 2018 Jul 31;13(7):e0201356. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reeves, PG. Components of the AIN-93 diets as improvements in the AIN-76A diet. J Nutr. 1997 May;127(5 Suppl):838S-841S. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi C, Yue F, Shi F, Qin Q, Wang L, Wang G, Mu L, Liu D, Li Y, Yu T, She J. Selenium-Containing Amino Acids Protect Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis via Ameliorating Oxidative Stress and Intestinal Inflammation. J Inflamm Res. 2021 Jan 14;14:85-95. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shi J, Ji S, Xu M, Wang Y, Shi H. Selenium inhibits ferroptosis in ulcerative colitis through the induction of Nrf2/Gpx4. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2024 Sep 21;48(9):102467. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suwendi E, Iwaya H, Lee JS, Hara H, Ishizuka S. Zinc deficiency induces dysregulation of cytokine productions in an experimental colitis of rats. Biomed Res. 2012 Dec;33(6):329-36. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun Y, Wang Z, Gong P, Yao W, Ba Q, Wang H. Review on the health-promoting effect of adequate selenium status. Front Nutr. 2023 Mar 16;10:1136458. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ala M, Kheyri Z. The rationale for selenium supplementation in inflammatory bowel disease: A mechanism-based point of view. Nutrition. 2021 May;85:111153. Epub 2021 Jan 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa JA, McKay DM, Raman M. Selenium, Immunity, and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients. 2024; 16(21):3620. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16213620; Khazdouz, M.; Daryani, N.E.; Alborzi, F.; Jazayeri, M.H.; Farsi, F.; Hasani, M.; Heshmati, J.; Shidfar, F. Effect of Selenium Supplementation on Expression of Sirt1 and Pgc-1alpha Genes in Ulcerative Colitis Patients: A Double Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin. Nutr. Res. 2020, 9, 284–295.

- Khazdouz, M.; Daryani, N.E.; Alborzi, F.; Jazayeri, M.H.; Farsi, F.; Hasani, M.; Heshmati, J.; Shidfar, F. Effect of Selenium Supplementation on Expression of Sirt1 and Pgc-1alpha Genes in Ulcerative Colitis Patients: A Double Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin. Nutr. Res. 2020, 9, 284–295.

- Jones, R.M.; Luo, L.; Ardita, C.S.; Richardson, A.N.; Kwon, Y.M.; Mercante, J.W.; Alam, A.; Gates, C.L.;Wu, H.; Swanson, P.A.; et al. Symbiotic lactobacilli stimulate gut epithelial proliferation via Nox-mediated generation of reactive oxygen species. EMBO J. 2013, 32, 3017–3028.

- Kato, M.; Marumo, M.; Nakayama, J.; Matsumoto, M.; Yabe-Nishimura, C.; Kamata, T. The ROS-generating oxidase Nox1 is required for epithelial restitution following colitis. Exp. Anim. 2016, 65, 197–205; Matsumoto, M.; Katsuyama, M.; Iwata, K.

- Ibi, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, K.; Nauseef, W.M.; Yabe-Nishimura, C. Characterization of N-glycosylation sites on the extracellular domain of NOX1/NADPH oxidase. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 68, 196–204.

- Esworthy, RS. Evaluation of the Use of Cell Lines in Studies of Selenium-Dependent Glutathione Peroxidase 2 (GPX2) Involvement in Colorectal Cancer. Diseases. 2024 Sep 10;12(9):207. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- MacFie TS, Poulsom R, Parker A, Warnes G, Boitsova T, Nijhuis A, Suraweera N, Poehlmann A, Szary J, Feakins R, Jeffery R, Harper RW, Jubb AM, Lindsay JO, Silver A. DUOX2 and DUOXA2 form the predominant enzyme system capable of producing the reactive oxygen species H2O2 in active ulcerative colitis and are modulated by 5-aminosalicylic acid. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014 Mar;20(3):514-24. [CrossRef]

- Haberman Y, Tickle TL, Dexheimer PJ, Kim MO, Tang D, Karns R, Baldassano RN, Noe JD, Rosh J, Markowitz J, Heyman MB, Griffiths AM, Crandall WV, Mack DR, Baker SS, Huttenhower C, Keljo DJ, Hyams JS, Kugathasan S, Walters TD, Aronow B, Xavier RJ, Gevers D, Denson LA. Pediatric Crohn disease patients exhibit specific ileal transcriptome and microbiota signature. J Clin Invest. 2014 Aug;124(8):3617-33. Epub 2014 Jul 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li J, Simmons AJ, Hawkins CV, Chiron S, Ramirez-Solano MA, Tasneem N, Kaur H, Xu Y, Revetta F, Vega PN, Bao S, Cui C, Tyree RN, Raber LW, Conner AN, Pilat JM, Jacobse J, McNamara KM, Allaman MM, Raffa GA, Gobert AP, Asim M, Goettel JA, Choksi YA, Beaulieu DB, Dalal RL, Horst SN, Pabla BS, Huo Y, Landman BA, Roland JT, Scoville EA, Schwartz DA, Washington MK, Shyr Y, Wilson KT, Coburn LA, Lau KS, Liu Q. Identification and multimodal characterization of a specialized epithelial cell type associated with Crohn's disease. Nat Commun. 2024 Aug 22;15(1):7204. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Deng L, He S, Li Y, Ding R, Li X, Guo N, Luo L. Identification of Lipocalin 2 as a Potential Ferroptosis-related Gene in Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023 Sep 1;29(9):1446-1457. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fichman Y, Rowland L, Nguyen TT, Chen SJ, Mittler R. Propagation of a rapid cell-to-cell H2O2 signal over long distances in a monolayer of cardiomyocyte cells. Redox Biol. 2024 Apr;70:103069. Epub 2024 Feb 9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dang PM, Rolas L, El-Benna J. The Dual Role of Reactive Oxygen Species-Generating Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate Oxidases in Gastrointestinal Inflammation and Therapeutic Perspectives. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2020 Aug 10;33(5):354-373. Epub 2020 Feb 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaBere B, Gutierrez MJ, Wright H, Garabedian E, Ochs HD, Fuleihan RL, Secord E, Marsh R, Sullivan KE, Cunningham-Rundles C, Notarangelo LD, Chen K. Chronic Granulomatous Disease With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Clinical Presentation, Treatment, and Outcomes From the USIDNET Registry. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022 May;10(5):1325-1333.e5. Epub 2022 Jan 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aviello G, Knaus UG. NADPH oxidases and ROS signaling in the gastrointestinal tract. Mucosal Immunol. 2018 Jul;11(4):1011-1023. Epub 2018 May 9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao S, Carr ED, Xu YH, Hunt NH. Gp91(phox) contributes to the development of experimental inflammatory bowel disease. Immunol Cell Biol. 2011 Nov;89(8):853-60. Epub 2011 Feb 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes P, Dhillon S, O'Neill K, Thoeni C, Hui KY, Elkadri A, Guo CH, Kovacic L, Aviello G, Alvarez LA, Griffiths AM, Snapper SB, Brant SR, Doroshow JH, Silverberg MS, Peter I, McGovern DP, Cho J, Brumell JH, Uhlig HH, Bourke B, Muise AA, Knaus UG. Defects in NADPH Oxidase Genes NOX1 and DUOX2 in Very Early Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Sep 1;1(5):489-502. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Muise AM, Xu W, Guo CH, Walters TD, Wolters VM, Fattouh R, Lam GY, Hu P, Murchie R, Sherlock M, Gana JC; NEOPICS; Russell RK, Glogauer M, Duerr RH, Cho JH, Lees CW, Satsangi J, Wilson DC, Paterson AD, Griffiths AM, Silverberg MS, Brumell JH. NADPH oxidase complex and IBD candidate gene studies: identification of a rare variant in NCF2 that results in reduced binding to RAC2. Gut. 2012 Jul;61(7):1028-35. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300078. Epub 2011 Sep 7. Erratum in: Gut. 2013 Oct;62(10):1432. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schwerd T, Bryant RV, Pandey S, Capitani M, Meran L, Cazier JB, Jung J, Mondal K, Parkes M, Mathew CG, Fiedler K, McCarthy DJ; WGS500 Consortium; Oxford IBD cohort study investigators; COLORS in IBD group investigators; UK IBD Genetics Consortium; Sullivan PB, Rodrigues A, Travis SPL, Moore C, Sambrook J, Ouwehand WH, Roberts DJ, Danesh J; INTERVAL Study; Russell RK, Wilson DC, Kelsen JR, Cornall R, Denson LA, Kugathasan S, Knaus UG, Serra EG, Anderson CA, Duerr RH, McGovern DP, Cho J, Powrie F, Li VS, Muise AM, Uhlig HH. NOX1 loss-of-function genetic variants in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Mucosal Immunol. 2018 Mar;11(2):562-574. Epub 2017 Nov 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jiang H, Wu J, Ke S, Hu Y, Fei A, Zhen Y, Yu J, Zhu K. High prevalence of DUOX2 gene mutations among children with congenital hypothyroidism in central China. Eur J Med Genet. 2016 Oct;59(10):526-31. Epub 2016 Aug 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohata H, Shiokawa D, Obata Y, Sato A, Sakai H, Fukami M, Hara W, Taniguchi H, Ono M, Nakagama H, Okamoto K. NOX1-Dependent mTORC1 Activation via S100A9 Oxidation in Cancer Stem-like Cells Leads to Colon Cancer Progression. Cell Rep. 2019 Jul 30;28(5):1282-1295.e8. [CrossRef]

- van der Post S, Birchenough GMH, Held JM. NOX1-dependent redox signaling potentiates colonic stem cell proliferation to adapt to the intestinal microbiota by linking EGFR and TLR activation. Cell Rep. 2021 Apr 6;35(1):108949. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Coant N, Ben Mkaddem S, Pedruzzi E, Guichard C, Tréton X, Ducroc R, Freund JN, Cazals-Hatem D, Bouhnik Y, Woerther PL, Skurnik D, Grodet A, Fay M, Biard D, Lesuffleur T, Deffert C, Moreau R, Groyer A, Krause KH, Daniel F, Ogier-Denis E. NADPH oxidase 1 modulates WNT and NOTCH1 signaling to control the fate of proliferative progenitor cells in the colon. Mol Cell Biol. 2010 Jun;30(11):2636-50. Epub 2010 Mar 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kato M, Marumo M, Nakayama J, Matsumoto M, Yabe-Nishimura C, Kamata T. The ROS-generating oxidase Nox1 is required for epithelial restitution following colitis. Exp Anim. 2016 Jul 29;65(3):197-205. Epub 2016 Feb 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hsu NY, Nayar S, Gettler K, Talware S, Giri M, Alter I, Argmann C, Sabic K, Thin TH, Ko HM, Werner R, Tastad C, Stappenbeck T, Azabdaftari A, Uhlig HH, Chuang LS, Cho JH. NOX1 is essential for TNFα-induced intestinal epithelial ROS secretion and inhibits M cell signatures. Gut. 2023 Apr;72(4):654-662. Epub 2022 Oct 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Koeberle SC, Gollowitzer A, Laoukili J, Kranenburg O, Werz O, Koeberle A, Kipp AP. Distinct and overlapping functions of glutathione peroxidases 1 and 2 in limiting NF-κB-driven inflammation through redox-active mechanisms. Redox Biol. 2020 Jan;28:101388. Epub 2019 Nov 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Matziouridou C, Rocha SDC, Haabeth OA, Rudi K, Carlsen H, Kielland A. iNOS- and NOX1-dependent ROS production maintains bacterial homeostasis in the ileum of mice. Mucosal Immunol. 2018 May;11(3):774-784. Epub 2017 Dec 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drieu La Rochelle J, Ward J, Stenke E, Yin Y, Matsumoto M, Jennings R, Aviello G, Knaus UG. Dysregulated NOX1-NOS2 activity as hallmark of ileitis in mice. Mucosal Immunol. 2024 Sep 7:S1933-0219(24)00093-X. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benhar, M. Roles of mammalian glutathione peroxidase and thioredoxin reductase enzymes in the cellular response to nitrosative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018 Nov 1;127:160-164. Epub 2018 Feb 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS, Morrison B 3rd, Stockwell BR. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012 May 25;149(5):1060-72. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang M, Zheng C, Zhou F, Ying X, Zhang X, Peng C, Wang L. Iron and Inflammatory Cytokines Synergistically Induce Colonic Epithelial Cell Ferroptosis in Colitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Nov 25. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen X, Iwata K, Ikuta K, Zhang X, Zhu K, Ibi M, Matsumoto M, Asaoka N, Liu J, Katsuyama M, Yabe-Nishimura C. NOX1/NADPH oxidase regulates the expression of multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 and maintains intracellular glutathione levels. FEBS J. 2019 Feb;286(4):678-687. Epub 2019 Feb 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haber AL, Biton M, Rogel N, Herbst RH, Shekhar K, Smillie C, Burgin G, Delorey TM, Howitt MR, Katz Y, Tirosh I, Beyaz S, Dionne D, Zhang M, Raychowdhury R, Garrett WS, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Shi HN, Yilmaz O, Xavier RJ, Regev A. A single-cell survey of the small intestinal epithelium. Nature. 2017 Nov 16;551(7680):333-339. Epub 2017 Nov 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Grasberger H, Gao J, Nagao-Kitamoto H, Kitamoto S, Zhang M, Kamada N, Eaton KA, El-Zaatari M, Shreiner AB, Merchant JL, Owyang C, Kao JY. Increased Expression of DUOX2 Is an Epithelial Response to Mucosal Dysbiosis Required for Immune Homeostasis in Mouse Intestine. Gastroenterology. 2015 Dec;149(7):1849-59. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.062. Epub 2015 Aug 7. Erratum in: Gastroenterology. 2023 May;164(6):1033. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lipinski S, Till A, Sina C, Arlt A, Grasberger H, Schreiber S, Rosenstiel P. DUOX2-derived reactive oxygen species are effectors of NOD2-mediated antibacterial responses. J Cell Sci. 2009 Oct 1;122(Pt 19):3522-30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies JM, Abreu MT. The innate immune system and inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015 Jan;50(1):24-33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paidimarri SP, Ayuthu S, Chauhan YD, Bittla P, Mirza AA, Saad MZ, Khan S. Contribution of the Gut Microbiota to the Perpetuation of Inflammation in Crohn's Disease: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2024 Aug 24;16(8):e67672. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jauregui-Amezaga A, Smet A. The Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Clin Med. 2024 Aug 7;13(16):4622. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gaschler MM, Hu F, Feng H, Linkermann A, Min W, Stockwell BR. Determination of the Subcellular Localization and Mechanism of Action of Ferrostatins in Suppressing Ferroptosis. ACS Chem Biol. 2018 Apr 20;13(4):1013-1020. Epub 2018 Mar 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cochemé HM, Kelso GF, James AM, Ross MF, Trnka J, Mahendiran T, Asin-Cayuela J, Blaikie FH, Manas AR, Porteous CM, Adlam VJ, Smith RA, Murphy MP. Mitochondrial targeting of quinones: therapeutic implications. Mitochondrion. 2007 Jun;7 Suppl:S94-102. Epub 2007 Mar 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruidenier L, Kuiper I, Lamers CB, Verspaget HW. Intestinal oxidative damage in inflammatory bowel disease: semi-quantification, localization, and association with mucosal antioxidants. J Pathol. 2003 Sep;201(1):28-36. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds PD, Rhenius ST, Hunter JO. Xanthine oxidase activity is not increased in the colonic mucosa of ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996 Oct;10(5):737-41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salim, AS. Role of oxygen-derived free radical scavengers in the management of recurrent attacks of ulcerative colitis: a new approach. J Lab Clin Med. 1992 Jun;119(6):710-7. [PubMed]

- Järnerot G, Ström M, Danielsson A, Kilander A, Lööf L, Hultcrantz R, Löfberg R, Florén C, Nilsson A, Broström O. Allopurinol in addition to 5-aminosalicylic acid-based drugs for the maintenance treatment of ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000 Sep;14(9):1159-62. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacher P, Nivorozhkin A, Szabó C. Therapeutic effects of xanthine oxidase inhibitors: renaissance half a century after the discovery of allopurinol. Pharmacol Rev. 2006 Mar;58(1):87-114. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- El-Mahdy NA, Saleh DA, Amer MS, Abu-Risha SE. Role of allopurinol and febuxostat in the amelioration of dextran-induced colitis in rats. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2020 Jan 1;141:105116. Epub 2019 Oct 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li H, Li X, Wang Y, Han W, Li H, Zhang Q. Hypoxia-Mediated Upregulation of Xanthine Oxidoreductase Causes DNA Damage of Colonic Epithelial Cells in Colitis. Inflammation. 2024 Aug;47(4):1142-1155. Epub 2024 Jan 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang J, Yin H, Liao L, Qin H, Ueda F, Uemura K, Eguchi K, Bharate GY, Maeda H. Water soluble PEG-conjugate of xanthine oxidase inhibitor, PEG-AHPP micelles, as a novel therapeutic for ROS related inflammatory bowel diseases. J Control Release. 2016 Feb 10;223:188-196. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.12.049. Epub 2015 Dec 29. PMID: 26739550. 119. Worledge CS, Kostelecky RE, Zhou L, Bhagavatula G, Colgan SP, Lee JS. Allopurinol Disrupts Purine Metabolism to Increase Damage in Experimental Colitis. Cells. 2024 Feb 21;13(5):373. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Worledge CS, Kostelecky RE, Zhou L, Bhagavatula G, Colgan SP, Lee JS. Allopurinol Disrupts Purine Metabolism to Increase Damage in Experimental Colitis. Cells. 2024 Feb 21;13(5):373. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bayoumy AB, Mulder CJJ, Ansari AR, Barclay ML, Florin T, Kiszka-Kanowitz M, Derijks L, Sharma V, de Boer NKH. Uphill battle: Innovation of thiopurine therapy in global inflammatory bowel disease care. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2024 Feb;43(1):36-47. Epub 2024 Feb 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Riaz AA, Wan MX, Schäfer T, Dawson P, Menger MD, Jeppsson B, Thorlacius H. Allopurinol and superoxide dismutase protect against leucocyte-endothelium interactions in a novel model of colonic ischaemia-reperfusion. Br J Surg. 2002 Dec;89(12):1572-80. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiaro TR, Soto R, Zac Stephens W, Kubinak JL, Petersen C, Gogokhia L, Bell R, Delgado JC, Cox J, Voth W, Brown J, Stillman DJ, O'Connell RM, Tebo AE, Round JL. A member of the gut mycobiota modulates host purine metabolism exacerbating colitis in mice. Sci Transl Med. 2017 Mar 8;9(380):eaaf9044. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf9044. Erratum in: Sci Transl Med. 2017 May 3;9(388):eaan5218. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li H, Li X, Wang Y, Han W, Li H, Zhang Q. Hypoxia-Mediated Upregulation of Xanthine Oxidoreductase Causes DNA Damage of Colonic Epithelial Cells in Colitis. Inflammation. 2024 Aug;47(4):1142-1155. Epub 2024 Jan 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esworthy RS, Smith DD, Chu FF. A Strong Impact of Genetic Background on Gut Microflora in Mice. Int J Inflam. 2010 Jun 1;2010(2010):986046. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Atiq A, Lee HJ, Khan A, Kang MH, Rehman IU, Ahmad R, Tahir M, Ali J, Choe K, Park JS, Kim MO. Vitamin E Analog Trolox Attenuates MPTP-Induced Parkinson's Disease in Mice, Mitigating Oxidative Stress, Neuroinflammation, and Motor Impairment. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Jun 9;24(12):9942. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Esworthy RS, Kim BW, Larson GP, Yip ML, Smith DD, Li M, Chu FF. Colitis locus on chromosome 2 impacting the severity of early-onset disease in mice deficient in GPX1 and GPX2. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011 Jun;17(6):1373-86. Epub 2010 Sep 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Seiler A, Schneider M, Förster H, Roth S, Wirth EK, Culmsee C, Plesnila N, Kremmer E, Rådmark O, Wurst W, Bornkamm GW, Schweizer U, Conrad M. Glutathione peroxidase 4 senses and translates oxidative stress into 12/15-lipoxygenase dependent- and AIF-mediated cell death. Cell Metab. 2008 Sep;8(3):237-48. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinhilber, D. (2016). Lipoxygenases: An Introduction. In: Steinhilber, D. (eds) Lipoxygenases in Inflammation. Progress in Inflammation Research. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Friedmann Angeli JP, Schneider M, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Tyurin VA, Hammond VJ, Herbach N, Aichler M, Walch A, Eggenhofer E, Basavarajappa D, Rådmark O, Kobayashi S, Seibt T, Beck H, Neff F, Esposito I, Wanke R, Förster H, Yefremova O, Heinrichmeyer M, Bornkamm GW, Geissler EK, Thomas SB, Stockwell BR, O'Donnell VB, Kagan VE, Schick JA, Conrad M. Inactivation of the ferroptosis regulator Gpx4 triggers acute renal failure in mice. Nat Cell Biol. 2014 Dec;16(12):1180-91. Epub 2014 Nov 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shah R, Shchepinov MS, Pratt DA. Resolving the Role of Lipoxygenases in the Initiation and Execution of Ferroptosis. ACS Cent Sci. 2018 Mar 28;4(3):387-396. Epub 2018 Feb 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wenzel SE, Tyurina YY, Zhao J, St Croix CM, Dar HH, Mao G, Tyurin VA, Anthonymuthu TS, Kapralov AA, Amoscato AA, Mikulska-Ruminska K, Shrivastava IH, Kenny EM, Yang Q, Rosenbaum JC, Sparvero LJ, Emlet DR, Wen X, Minami Y, Qu F, Watkins SC, Holman TR, VanDemark AP, Kellum JA, Bahar I, Bayır H, Kagan VE. PEBP1 Wardens Ferroptosis by Enabling Lipoxygenase Generation of Lipid Death Signals. Cell. 2017 Oct 19;171(3):628-641.e26. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Agarwal R, Wang ZY, Bik DP, Mukhtar H. Nordihydroguaiaretic acid, an inhibitor of lipoxygenase, also inhibits cytochrome P-450-mediated monooxygenase activity in rat epidermal and hepatic microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 1991 May-Jun;19(3):620-4. [PubMed]

- Koppenol WH. The centennial of the Fenton reaction. Free Radic Biol Med. 1993 Dec;15(6):645-51. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(93)90168-t. PMID: 8138191; Gutteridge JM. Iron and oxygen: a biologically damaging mixture. Acta Paediatr Scand Suppl. 1989;361:78-85. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HOCHSTEIN P, ERNSTER L. ADP-ACTIVATED LIPID PEROXIDATION COUPLED TO THE TPNH OXIDASE SYSTEM OF MICROSOMES. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1963 Aug 14;12:388-94. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannai S, Tsukeda H, Okumura H. Effect of antioxidants on cultured human diploid fibroblasts exposed to cystine-free medium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1977 Feb 21;74(4):1582-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ursini F, Bosello Travain V, Cozza G, Miotto G, Roveri A, Toppo S, Maiorino M. A white paper on Phospholipid Hydroperoxide Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx4) forty years later. Free Radic Biol Med. 2022 Aug 1;188:117-133. Epub 2022 Jun 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiorino M, Chu FF, Ursini F, Davies KJ, Doroshow JH, Esworthy RS. Phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase is the 18-kDa selenoprotein expressed in human tumor cell lines. J Biol Chem. 1991 Apr 25;266(12):7728-32. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie Y, Hou W, Song X, Yu Y, Huang J, Sun X, Kang R, Tang D. Ferroptosis: process and function. Cell Death Differ. 2016 Mar;23(3):369-79. Epub 2016 Jan 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Damiani CR, Benetton CA, Stoffel C, Bardini KC, Cardoso VH, Di Giunta G, Pinho RA, Dal-Pizzol F, Streck EL. Oxidative stress and metabolism in animal model of colitis induced by dextran sulfate sodium. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007 Nov;22(11):1846-51. Epub 2007 Apr 19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minaiyan M, Mostaghel E, Mahzouni P. Preventive Therapy of Experimental Colitis with Selected iron Chelators and Anti-oxidants. Int J Prev Med. 2012 Mar;3(Suppl 1):S162-9. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Millar AD, Rampton DS, Blake DR. Effects of iron and iron chelation in vitro on mucosal oxidant activity in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000 Sep;14(9):1163-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu Y, Ran L, Yang Y, Gao X, Peng M, Liu S, Sun L, Wan J, Wang Y, Yang K, Yin M, Chunyu W. Deferasirox alleviates DSS-induced ulcerative colitis in mice by inhibiting ferroptosis and improving intestinal microbiota. Life Sci. 2023 Feb 1;314:121312. Epub 2022 Dec 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantzaris MD, Bellou S, Skiada V, Kitsati N, Fotsis T, Galaris D. Intracellular labile iron determines H2O2-induced apoptotic signaling via sustained activation of ASK1/JNK-p38 axis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016 Aug;97:454-465. Epub 2016 Jul 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vechalapu SK, Kumar R, Chatterjee N, Gupta S, Khanna S, Thimmappa PY, Senthil S, Eerlapally R, Joshi MB, Misra SK, Draksharapu A, Allimuthu D. Redox modulator iron complexes trigger intrinsic apoptosis pathway in cancer cells. iScience. 2024 ;27(6):109899. 3 May. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gao M, Monian P, Quadri N, Ramasamy R, Jiang X. Glutaminolysis and Transferrin Regulate Ferroptosis. Mol Cell. 2015 Jul 16;59(2):298-308. Epub 2015 Jul 9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Parant F, Mure F, Maurin J, Beauvilliers L, Chorfa C, El Jamali C, Ohlmann T, Chavatte L. Selenium Discrepancies in Fetal Bovine Serum: Impact on Cellular Selenoprotein Expression. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Jul 1;25(13):7261. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bannai S, Tsukeda H, Okumura H. Effect of antioxidants on cultured human diploid fibroblasts exposed to cystine-free medium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1977 Feb 21;74(4):1582-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolma S, Lessnick SL, Hahn WC, Stockwell BR. Identification of genotype-selective antitumor agents using synthetic lethal chemical screening in engineered human tumor cells. Cancer Cell. 2003 Mar;3(3):285-96. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang WS, Stockwell BR. Synthetic lethal screening identifies compounds activating iron-dependent, nonapoptotic cell death in oncogenic-RAS-harboring cancer cells. Chem Biol. 2008 Mar;15(3):234-45. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hirschhorn T, Stockwell BR. The development of the concept of ferroptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019 Mar;133:130-143. Epub 2018 Sep 28. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Esworthy RS, Doan K, Doroshow JH, Chu FF. Cloning and sequencing of the cDNA encoding a human testis phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase. Gene. 1994 Jul 8;144(2):317-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurst R, Korytowski W, Kriska T, Esworthy RS, Chu FF, Girotti AW. Hyperresistance to cholesterol hydroperoxide-induced peroxidative injury and apoptotic death in a tumor cell line that overexpresses glutathione peroxidase isotype-4. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001 Nov 1;31(9):1051-65. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kriska T, Levchenko VV, Chu FF, Esworthy RS, Girotti AW. Novel enrichment of tumor cell transfectants expressing high levels of type 4 glutathione peroxidase using 7alpha-hydroperoxycholesterol as a selection agent. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008 Sep 1;45(5):700-7. Epub 2008 Jun 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Esworthy RS, Baker MA, Chu FF. Expression of selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidase in human breast tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 1995 Feb 15;55(4):957-62. [PubMed]

- Nguyen VD, Saaranen MJ, Karala AR, Lappi AK, Wang L, Raykhel IB, Alanen HI, Salo KE, Wang CC, Ruddock LW. Two endoplasmic reticulum PDI peroxidases increase the efficiency of the use of peroxide during disulfide bond formation. J Mol Biol. 2011 Feb 25;406(3):503-15. Epub 2011 Jan 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood ZA, Poole LB, Karplus PA. Peroxiredoxin evolution and the regulation of hydrogen peroxide signaling. Science. 2003 Apr 25;300(5619):650-3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastian SA, Kaiwan O, Co EL, Mehendale M, Mohan BP. Current Pharmacologic Options and Emerging Therapeutic Approaches for the Management of Ulcerative Colitis: A Narrative Review. Spartan Med Res J. 2024 Sep 9;9(3):123397. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ye K, Chen Z, Xu Y. The double-edged functions of necroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2023 Feb 27;14(2):163. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gao M, Monian P, Pan Q, Zhang W, Xiang J, Jiang X. Ferroptosis is an autophagic cell death process. Cell Res. 2016 Sep;26(9):1021-32. Epub 2016 Aug 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hou JK, Abraham B, El-Serag H. Dietary intake and risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Apr;106(4):563-73. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldenburg B, Koningsberger JC, Van Berge Henegouwen GP, Van Asbeck BS, Marx JJ. Iron and inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001 Apr;15(4):429-38. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy TH, Miyamoto M, Sastre A, Schnaar RL, Coyle JT. Glutamate toxicity in a neuronal cell line involves inhibition of cystine transport leading to oxidative stress. Neuron. 1989 Jun;2(6):1547-58. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tallima H, El Ridi R. Arachidonic acid: Physiological roles and potential health benefits - A review. J Adv Res. 2017 Nov 24;11:33-41. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Platt, SR. The role of glutamate in central nervous system health and disease--a review. Vet J. 2007 Mar;173(2):278-86. Epub 2005 Dec 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang X, Ma Y, Ji J, Zhao X, Yuan J, Wang H, Lv G. High-fat diet alleviates colitis by inhibiting ferroptosis via solute carrier family seven member 11. J Nutr Biochem. 2022 Nov;109:109106. Epub 2022 Jul 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang X, Li W, Ma Y, Zhao X, He L, Sun P, Wang H. High-fat diet aggravates colitis-associated carcinogenesis by evading ferroptosis in the ER stress-mediated pathway. Free Radic Biol Med. 2021 Dec;177:156-166. Epub 2021 Oct 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahalhal A, Burkitt MD, Duckworth CA, Hold GL, Campbell BJ, Pritchard DM, Probert CS. Long-Term Iron Deficiency and Dietary Iron Excess Exacerbate Acute Dextran Sodium Sulphate-Induced Colitis and Are Associated with Significant Dysbiosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Mar 31;22(7):3646. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moon S, Kim M, Kim Y, Lee S. Supplementation with High or Low Iron Reduces Colitis Severity in an AOM/DSS Mouse Model. Nutrients. 2022 May 12;14(10):2033. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang Y, Yin L, Zeng X, Li J, Yin Y, Wang Q, Li J, Yang H. Dietary High Dose of Iron Aggravates the Intestinal Injury but Promotes Intestinal Regeneration by Regulating Intestinal Stem Cells Activity in Adult Mice With Dextran Sodium Sulfate-Induced Colitis. Front Vet Sci. 2022 Jun 15;9:870303. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carrier JC, Aghdassi E, Jeejeebhoy K, Allard JP. Exacerbation of dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis by dietary iron supplementation: role of NF-kappaB. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006 May;21(4):381-7. Epub 2005 Aug 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahalhal A, Frau A, Burkitt MD, Ijaz UZ, Lamb CA, Mansfield JC, Lewis S, Pritchard DM, Probert CS. Oral Ferric Maltol Does Not Adversely Affect the Intestinal Microbiota of Patients or Mice, But Ferrous Sulphate Does. Nutrients. 2021 Jun 30;13(7):2269. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mahalhal A, Burkitt MD, Duckworth CA, Hold GL, Campbell BJ, Pritchard DM, Probert CS. Long-Term Iron Deficiency and Dietary Iron Excess Exacerbate Acute Dextran Sodium Sulphate-Induced Colitis and Are Associated with Significant Dysbiosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Mar 31;22(7):3646. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mahalhal A, Williams JM, Johnson S, Ellaby N, Duckworth CA, Burkitt MD, Liu X, Hold GL, Campbell BJ, Pritchard DM, Probert CS. Oral iron exacerbates colitis and influences the intestinal microbiota. PLoS One. 2018 Oct 11;13(10):e0202460. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Song Y, Song Q, Tan F, Wang Y, Li C, Liao S, Yu K, Mei Z, Lv L. Seliciclib alleviates ulcerative colitis by inhibiting ferroptosis and improving intestinal inflammation. Life Sci. 2024 Aug 15;351:122794. Epub 2024 Jun 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, Yin L, Zeng X, Li J, Yin Y, Wang Q, Li J, Yang H. Dietary High Dose of Iron Aggravates the Intestinal Injury but Promotes Intestinal Regeneration by Regulating Intestinal Stem Cells Activity in Adult Mice With Dextran Sodium Sulfate-Induced Colitis. Front Vet Sci. 2022 Jun 15;9:870303. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen X, Yu C, Kang R, Tang D. Iron Metabolism in Ferroptosis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020 Oct 7;8:590226. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maiorino M, Conrad M, Ursini F. GPx4, Lipid Peroxidation, and Cell Death: Discoveries, Rediscoveries, and Open Issues. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2018 Jul 1;29(1):61-74. Epub 2017 May 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee JY, Kim WK, Bae KH, Lee SC, Lee EW. Lipid Metabolism and Ferroptosis. Biology (Basel). 2021 Mar 2;10(3):184. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kakhlon O, Cabantchik ZI. The labile iron pool: characterization, measurement, and participation in cellular processes(1). Free Radic Biol Med. 2002 Oct 15;33(8):1037-46. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parant, F.;Mure, F.;Maurin, J.; Beauvilliers, L.; Chorfa, C.; El Jamali, C.; Ohlmann, T.; Chavatte, L. Selenium Discrepancies in Fetal Bovine Serum: Impact on Cellular Selenoprotein Expression. Int. J.Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7261. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park VS, Pope LE, Ingram J, Alchemy GA, Purkal J, Andino-Frydman EY, Jin S, Singh S, Chen A, Narayanan P, Kongpachith S, Phillips DC, Dixon SJ, Popovic R. Lipid composition differentiates ferroptosis sensitivity between in vitro and in vivo systems. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2024 Nov 15:2024.11.14.622381. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Santesmasses D, Gladyshev VN. Selenocysteine Machinery Primarily Supports TXNRD1 and GPX4 Functions and Together They Are Functionally Linked with SCD and PRDX6. Biomolecules. 2022 Jul 28;12(8):1049. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ, Fulda S, Gascón S, Hatzios SK, Kagan VE, Noel K, Jiang X, Linkermann A, Murphy ME, Overholtzer M, Oyagi A, Pagnussat GC, Park J, Ran Q, Rosenfeld CS, Salnikow K, Tang D, Torti FM, Torti SV, Toyokuni S, Woerpel KA, Zhang DD. Ferroptosis: A Regulated Cell Death Nexus Linking Metabolism, Redox Biology, and Disease. Cell. 2017 Oct 5;171(2):273-285. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stockwell, BR. Ferroptosis turns 10: Emerging mechanisms, physiological functions, and therapeutic applications. Cell. 2022 Jul 7;185(14):2401-2421. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lin S, Zheng Y, Chen M, Xu L, Huang H. The interactions between ineffective erythropoiesis and ferroptosis in β-thalassemia. Front Physiol. 2024 Feb 26;15:1346173. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chassaing B, Aitken JD, Malleshappa M, Vijay-Kumar M. Dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis in mice. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2014 Feb 4;104:15.25.1-15.25.14. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dieleman LA, Ridwan BU, Tennyson GS, Beagley KW, Bucy RP, Elson CO. Dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis occurs in severe combined immunodeficient mice. Gastroenterology. 1994 Dec;107(6):1643-52. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim TW, Seo JN, Suh YH, Park HJ, Kim JH, Kim JY, Oh KI. Involvement of lymphocytes in dextran sulfate sodium-induced experimental colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2006 Jan 14;12(2):302-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gancarcikova S, Lauko S, Hrckova G, Andrejcakova Z, Hajduckova V, Madar M, Kolesar Fecskeova L, Mudronova D, Mravcova K, Strkolcova G, Nemcova R, Kacirova J, Staskova A, Vilcek S, Bomba A. Innovative Animal Model of DSS-Induced Ulcerative Colitis in Pseudo Germ-Free Mice. Cells. 2020 Dec 1;9(12):2571. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang C, Merlin D. Unveiling Colitis: A Journey through the Dextran Sodium Sulfate-induced Model. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2024 May 2;30(5):844-853. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maiorino M, Gregolin C, Ursini F. Phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:448-57. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato C, Suzuki Y, Parida IS, Kato S, Yamasaki H, Takekoshi S, Nakagawa K. Possible Glutathione Peroxidase 4-Independent Reduction of Phosphatidylcholine Hydroperoxide: Its Relevance to Ferroptosis. J Oleo Sci. 2022 Oct 28;71(11):1689-1694. Epub 2022 Oct 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo P, Liu D, Zhang Q, Yang F, Wong YK, Xia F, Zhang J, Chen J, Tian Y, Yang C, Dai L, Shen HM, Wang J. Celastrol induces ferroptosis in activated HSCs to ameliorate hepatic fibrosis via targeting peroxiredoxins and HO-1. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022 May;12(5):2300-2314. Epub 2021 Dec 18. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Song Y, Wang X, Sun Y, Yu N, Tian Y, Han J, Qu X, Yu X. PRDX1 inhibits ferroptosis by binding to Cullin-3 as a molecular chaperone in colorectal cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2024 Sep 23;20(13):5070-5086. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lai W, Zhu W, Wu J, Huang J, Li X, Luo Y, Wang Y, Zeng H, Li M, Qiu X, Wen X. HJURP inhibits sensitivity to ferroptosis inducers in prostate cancer cells by enhancing the peroxidase activity of PRDX1. Redox Biol. 2024 Nov;77:103392. Epub 2024 Oct 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- He J, Hou X, Wu J, Wang K, Qi X, Wei Z, Sun Y, Wang C, Yao H, Liu K. Hspb1 protects against severe acute pancreatitis by attenuating apoptosis and ferroptosis via interacting with Anxa2 to restore the antioxidative activity of Prdx1. Int J Biol Sci. 2024 Feb 25;20(5):1707-1728. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.84494. PMID: 38481805; PMCID: PMC10929186. 200. Chen P, Chen Z, Zhai J, Yang W, Wei H. Overexpression of PRDX2 in Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Enhances the Therapeutic Effect in a Neurogenic Erectile Dysfunction Rat Model by Inhibiting Ferroptosis. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2023 Feb 8;2023:4952857. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sun Y, Qiao Y, Liu Y, Zhou J, Wang X, Zheng H, Xu Z, Zhang J, Zhou Y, Qian L, Zhang C, Lou H. ent-Kaurane diterpenoids induce apoptosis and ferroptosis through targeting redox resetting to overcome cisplatin resistance. Redox Biol. 2021 Jul;43:101977. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2021.101977. Epub 2021 Apr 16. Erratum in: Redox Biol. 2024 Jun;72:103164. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xu S, Liu Y, Yang S, Fei W, Qin J, Lu W, Xu J. FXN targeting induces cell death in ovarian cancer stem-like cells through PRDX3-Mediated oxidative stress. iScience. 2024 Jul 14;27(8):110506. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cui S, Ghai A, Deng Y, Li S, Zhang R, Egbulefu C, Liang G, Achilefu S, Ye J. Identification of hyperoxidized PRDX3 as a ferroptosis marker reveals ferroptotic damage in chronic liver diseases. Mol Cell. 2023 Nov 2;83(21):3931-3939.e5. Epub 2023 Oct 19. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rashba-Step J, Tatoyan A, Duncan R, Ann D, Pushpa-Rehka TR, Sevanian A. Phospholipid peroxidation induces cytosolic phospholipase A2 activity: membrane effects versus enzyme phosphorylation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997 Jul 1;343(1):44-54. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scanavachi G, Coutinho A, Fedorov AA, Prieto M, Melo AM, Itri R. Lipid Hydroperoxide Compromises the Membrane Structure Organization and Softens Bending Rigidity. Langmuir. 2021 Aug 24;37(33):9952-9963. Epub 2021 Aug 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saraev DD, Pratt DA. Reactions of lipid hydroperoxides and how they may contribute to ferroptosis sensitivity. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2024 Aug;81:102478. Epub 2024 Jun 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun WY, Tyurin VA, Mikulska-Ruminska K, Shrivastava IH, Anthonymuthu TS, Zhai YJ, Pan MH, Gong HB, Lu DH, Sun J, Duan WJ, Korolev S, Abramov AY, Angelova PR, Miller I, Beharier O, Mao GW, Dar HH, Kapralov AA, Amoscato AA, Hastings TG, Greenamyre TJ, Chu CT, Sadovsky Y, Bahar I, Bayır H, Tyurina YY, He RR, Kagan VE. Phospholipase iPLA2β averts ferroptosis by eliminating a redox lipid death signal. Nat Chem Biol. 2021 Apr;17(4):465-476. Epub 2021 Feb 4. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Oh M, Jang SY, Lee JY, Kim JW, Jung Y, Kim J, Seo J, Han TS, Jang E, Son HY, Kim D, Kim MW, Park JS, Song KH, Oh KJ, Kim WK, Bae KH, Huh YM, Kim SH, Kim D, Han BS, Lee SC, Hwang GS, Lee EW, The lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 inhibitor Darapladib sensitises cancer cells to ferroptosis by remodelling lipid metabolism. Nat Commun. 2023 Sep 15;14(1):5728. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Adibhatla RM, Hatcher JF. Phospholipase A(2), reactive oxygen species, and lipid peroxidation in CNS pathologies. BMB Rep. 2008 Aug 31;41(8):560-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen JW, Dodia C, Feinstein SI, Jain MK, Fisher AB. 1-Cys peroxiredoxin, a bifunctional enzyme with glutathione peroxidase and phospholipase A2 activities. J Biol Chem. 2000 Sep 15;275(37):28421-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, AB. Peroxiredoxin 6 in the repair of peroxidized cell membranes and cell signaling. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2017 Mar 1;617:68-83. Epub 2016 Dec 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen Z, Inague A, Kaushal K, Fazeli G, N Xavier da Silva T, Ferreira Dos Santos A, Cheytan T, Porto Freitas F, Yildiz U, Gasparello Viviani L, Santiago Lima R, Peglow Pinz M, Medeiros I, Geronimo Pires Alegria T, Pereira da Silva R, Regina Diniz L, Weinzweig S, Klein-Seetharaman J, Trumpp A, Manas A, Hondal R, Fischer M, Bartenhagen C, Shimada BK, Seale LA, Fabiano M, Schweizer U, Netto LE, Meotti FC, Alborzinia H, Miyamoto S, Friedmann Angeli JP. PRDX6 contributes to selenocysteine metabolism and ferroptosis resistance. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2024 Jun 6:2024.06.04.597364. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Doll S, Freitas FP, Shah R, Aldrovandi M, da Silva MC, Ingold I, Goya Grocin A, Xavier da Silva TN, Panzilius E, Scheel CH, Mourão A, Buday K, Sato M, Wanninger J, Vignane T, Mohana V, Rehberg M, Flatley A, Schepers A, Kurz A, White D, Sauer M, Sattler M, Tate EW, Schmitz W, Schulze A, O'Donnell V, Proneth B, Popowicz GM, Pratt DA, Angeli JPF, Conrad M. FSP1 is a glutathione-independent ferroptosis suppressor. Nature. 2019 Nov;575(7784):693-698. Epub 2019 Oct 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantle D, Heaton RA, Hargreaves IP. Coenzyme Q10 and Immune Function: An Overview. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021 May 11;10(5):759. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fujita H, Tanaka YK, Ogata S, Suzuki N, Kuno S, Barayeu U, Akaike T, Ogra Y, Iwai K. PRDX6 augments selenium utilization to limit iron toxicity and ferroptosis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2024 Aug;31(8):1277-1285. Epub 2024 Jun 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen Z, Inague A, Kaushal K, Fazeli G, Schilling D, Xavier da Silva TN, Dos Santos AF, Cheytan T, Freitas FP, Yildiz U, Viviani LG, Lima RS, Pinz MP, Medeiros I, Iijima TS, Alegria TGP, Pereira da Silva R, Diniz LR, Weinzweig S, Klein-Seetharaman J, Trumpp A, Mañas A, Hondal R, Bartenhagen C, Fischer M, Shimada BK, Seale LA, Chillon TS, Fabiano M, Schomburg L, Schweizer U, Netto LE, Meotti FC, Dick TP, Alborzinia H, Miyamoto S, Friedmann Angeli JP. PRDX6 contributes to selenocysteine metabolism and ferroptosis resistance. Mol Cell. 2024 Nov 7:S1097-2765(24)00867-0. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Velarde JM, Allen KN, Salvador-Pascual A, Leija RG, Luong D, Moreno-Santillán DD, Ensminger DC, Vázquez-Medina JP. Peroxiredoxin 6 suppresses ferroptosis in lung endothelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2024 Jun;218:82-93. Epub 2024 Apr 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fisher AB, Dodia C, Sorokina EM, Li H, Zhou S, Raabe T, Feinstein SI. A novel lysophosphatidylcholine acyl transferase activity is expressed by peroxiredoxin 6. J Lipid Res. 2016 Apr;57(4):587-96. Epub 2016 Feb 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lagal DJ, Ortiz-Alcántara Á, Pedrajas JR, McDonagh B, Bárcena JA, Requejo-Aguilar R, Padilla CA. Loss of peroxiredoxin 6 (PRDX6) alters lipid composition and distribution resulting in increased sensitivity to ferroptosis. Biochem J. 2024 Nov 27:BCJ20240445. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esworthy RS, Chu FF, Doroshow JH. Analysis of glutathione-related enzymes. Curr Protoc Toxicol. 2001 May;Chapter 7:Unit7.1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storch J, McDermott L. Structural and functional analysis of fatty acid-binding proteins. J Lipid Res. 2009 Apr;50 Suppl(Suppl):S126-31. Epub 2008 Nov 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Catalá, A. Five decades with polyunsaturated Fatty acids: chemical synthesis, enzymatic formation, lipid peroxidation and its biological effects. J Lipids. 2013;2013:710290. Epub 2013 Dec 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ek-Von Mentzer BA, Zhang F, Hamilton JA. Binding of 13-HODE and 15-HETE to phospholipid bilayers, albumin, and intracellular fatty acid binding proteins. implications for transmembrane and intracellular transport and for protection from lipid peroxidation. J Biol Chem. 2001 May 11;276(19):15575-80. Epub 2001 Jan 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalá, A. Interaction of fatty acids, acyl-CoA derivatives and retinoids with microsomal membranes: effect of cytosolic proteins. Mol Cell Biochem. 1993 Mar 24;120(2):89-94. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guajardo MH, Terrasa AM, Catalá A. Retinal fatty acid binding protein reduce lipid peroxidation stimulated by long-chain fatty acid hydroperoxides on rod outer segments. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002 Apr 15;1581(3):65-74. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan X, Xu M, Ren Q, Fan Y, Liu B, Chen J, Wang Z, Sun X. Downregulation of fatty acid binding protein 4 alleviates lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress in diabetic retinopathy by regulating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ-mediated ferroptosis. Bioengineered. 2022 Apr;13(4):10540-10551. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sun J, Esplugues E, Bort A, Cardelo MP, Ruz-Maldonado I, Fernández-Tussy P, Wong C, Wang H, Ojima I, Kaczocha M, Perry R, Suárez Y, Fernández-Hernando C. Fatty acid binding protein 5 suppression attenuates obesity-induced hepatocellular carcinoma by promoting ferroptosis and intratumoral immune rewiring. Nat Metab. 2024 Apr;6(4):741-763. Epub 2024 Apr 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayr L, Grabherr F, Schwärzler J, Reitmeier I, Sommer F, Gehmacher T, Niederreiter L, He GW, Ruder B, Kunz KTR, Tymoszuk P, Hilbe R, Haschka D, Feistritzer C, Gerner RR, Enrich B, Przysiecki N, Seifert M, Keller MA, Oberhuber G, Sprung S, Ran Q, Koch R, Effenberger M, Tancevski I, Zoller H, Moschen AR, Weiss G, Becker C, Rosenstiel P, Kaser A, Tilg H, Adolph TE. Dietary lipids fuel GPX4-restricted enteritis resembling Crohn's disease. Nat Commun. 2020 Apr 14;11(1):1775. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yan J, Zeng Y, Guan Z, Li Z, Luo S, Niu J, Zhao J, Gong H, Huang T, Li Z, Deng A, Wen Q, Tan J, Jiang J, Bao X, Li S, Sun G, Zhang M, Zhi M, Yin Z, Sun WY, Li YF, He RR, Cao G. Inherent preference for polyunsaturated fatty acids instigates ferroptosis of Treg cells that aggravates high-fat-diet-related colitis. Cell Rep. 2024 Aug 27;43(8):114636. Epub 2024 Aug 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu M, Tao J, Yang Y, Tan S, Liu H, Jiang J, Zheng F, Wu B. Ferroptosis involves in intestinal epithelial cell death in ulcerative colitis. Cell Death Dis. 2020 Feb 3;11(2):86. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hondal, RJ. Selenium vitaminology: The connection between selenium, vitamin C, vitamin E, and ergothioneine. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2023 Aug;75:102328. Epub 2023 May 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gao Q, Esworthy RS, Kim BW, Synold TW, Smith DD, Chu FF. Atherogenic diets exacerbate colitis in mice deficient in glutathione peroxidase. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010 Dec;16(12):2043-54. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kaser A, Lee AH, Franke A, Glickman JN, Zeissig S, Tilg H, Nieuwenhuis EE, Higgins DE, Schreiber S, Glimcher LH, Blumberg RS. XBP1 links ER stress to intestinal inflammation and confers genetic risk for human inflammatory bowel disease. Cell. 2008 Sep 5;134(5):743-56. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Deka D, D'Incà R, Sturniolo GC, Das A, Pathak S, Banerjee A. Role of ER Stress Mediated Unfolded Protein Responses and ER Stress Inhibitors in the Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2022 Dec;67(12):5392-5406. Epub 2022 Mar 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadwell K, Liu JY, Brown SL, Miyoshi H, Loh J, Lennerz JK, Kishi C, Kc W, Carrero JA, Hunt S, Stone CD, Brunt EM, Xavier RJ, Sleckman BP, Li E, Mizushima N, Stappenbeck TS, Virgin HW 4th. A key role for autophagy and the autophagy gene Atg16l1 in mouse and human intestinal Paneth cells. Nature. 2008 Nov 13;456(7219):259-63. Epub 2008 Oct 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Miotto G, Rossetto M, Di Paolo ML, Orian L, Venerando R, Roveri A, Vučković AM, Bosello Travain V, Zaccarin M, Zennaro L, Maiorino M, Toppo S, Ursini F, Cozza G. Insight into the mechanism of ferroptosis inhibition by ferrostatin-1. Redox Biol. 2020 Jan;28:101328. Epub 2019 Sep 20. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang C, Chu Q, Dong W, Wang X, Zhao W, Dai X, Liu W, Wang B, Liu T, Zhong W, Jiang C, Cao H. Microbial metabolite deoxycholic acid-mediated ferroptosis exacerbates high-fat diet-induced colonic inflammation. Mol Metab. 2024 Jun;84:101944. Epub 2024 Apr 18. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cheli VT, Santiago González DA, Marziali LN, Zamora NN, Guitart ME, Spreuer V, Pasquini JM, Paez PM. The Divalent Metal Transporter 1 (DMT1) Is Required for Iron Uptake and Normal Development of Oligodendrocyte Progenitor Cells. J Neurosci. 2018 Oct 24;38(43):9142-9159. Epub 2018 Sep 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Singhal R, Mitta SR, Das NK, Kerk SA, Sajjakulnukit P, Solanki S, Andren A, Kumar R, Olive KP, Banerjee R, Lyssiotis CA, Shah YM. HIF-2α activation potentiates oxidative cell death in colorectal cancers by increasing cellular iron. J Clin Invest. 2021 Jun 15;131(12):e143691. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhao S, Gong Z, Zhou J, Tian C, Gao Y, Xu C, Chen Y, Cai W, Wu J. Deoxycholic Acid Triggers NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Aggravates DSS-Induced Colitis in Mice. Front Immunol. 2016 Nov 28;7:536. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Newmark HL, Lipkin M, Maheshwari N. Colonic hyperplasia and hyperproliferation induced by a nutritional stress diet with four components of Western-style diet. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990 Mar 21;82(6):491-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiszt M, Lekstrom K, Brenner S, Hewitt SM, Dana R, Malech HL, Leto TL. NAD(P)H oxidase 1, a product of differentiated colon epithelial cells, can partially replace glycoprotein 91phox in the regulated production of superoxide by phagocytes. J Immunol. 2003 Jul 1;171(1):299-306. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laleu B, Gaggini F, Orchard M, Fioraso-Cartier L, Cagnon L, Houngninou-Molango S, Gradia A, Duboux G, Merlot C, Heitz F, Szyndralewiez C, Page P. First in class, potent, and orally bioavailable NADPH oxidase isoform 4 (Nox4) inhibitors for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Med Chem. 2010 Nov 11;53(21):7715-30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang X, Ma Y, Ji J, Zhao X, Yuan J, Wang H, Lv G. High-fat diet alleviates colitis by inhibiting ferroptosis via solute carrier family seven member 11. J Nutr Biochem. 2022 Nov;109:109106. Epub 2022 Jul 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford RR, Prescott ET, Sylvester CF, Higdon AN, Shan J, Kilberg MS, Mungrue IN. Human CHAC1 Protein Degrades Glutathione, and mRNA Induction Is Regulated by the Transcription Factors ATF4 and ATF3 and a Bipartite ATF/CRE Regulatory Element. J Biol Chem. 2015 Jun 19;290(25):15878-15891. Epub 2015 Apr 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sun J, Ren H, Wang J, Xiao X, Zhu L, Wang Y, Yang L. CHAC1: a master regulator of oxidative stress and ferroptosis in human diseases and cancers. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2024 Oct 29;12:1458716. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wek, RC. Role of eIF2α Kinases in Translational Control and Adaptation to Cellular Stress. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2018 Jul 2;10(7):a032870. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Esworthy RS, Kim BW, Rivas GE, Leto TL, Doroshow JH, Chu FF. Analysis of candidate colitis genes in the Gdac1 locus of mice deficient in glutathione peroxidase-1 and -2. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e44262. Epub 2012 Sep 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gao S, Sun C, Kong J. Vitamin D Attenuates Ulcerative Colitis by Inhibiting ACSL4-Mediated Ferroptosis. Nutrients. 2023 Nov 20;15(22):4845. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wen W, Xu Y, Qian W, Huang L, Gong J, Li Y, Zhu W, Guo Z. PUFAs add fuel to Crohn's disease-associated AIEC-induced enteritis by exacerbating intestinal epithelial lipid peroxidation. Gut Microbes. 2023 Dec;15(2):2265578. Epub 2023 Oct 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Deng L, He S, Li Y, Ding R, Li X, Guo N, Luo L. Identification of Lipocalin 2 as a Potential Ferroptosis-related Gene in Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023 Sep 1;29(9):1446-1457. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen Z, Gu Q, Chen R. Promotive role of IRF7 in ferroptosis of colonic epithelial cells in ulcerative colitis by the miR-375-3p/SLC11A2 axis. Biomol Biomed. 2023 May 1;23(3):437-449. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen Y, Zhang P, Chen W, Chen G. Ferroptosis mediated DSS-induced ulcerative colitis associated with Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. Immunol Lett. 2020 Sep;225:9-15. Epub 2020 Jun 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brzozowa-Zasada M, Ianaro A, Piecuch A, Michalski M, Matysiak N, Stęplewska K. Immunohistochemical Expression of Glutathione Peroxidase-2 (Gpx-2) and Its Clinical Relevance in Colon Adenocarcinoma Patients. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Sep 27;24(19):14650. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Takagi T, Homma T, Fujii J, Shirasawa N, Yoriki H, Hotta Y, Higashimura Y, Mizushima K, Hirai Y, Katada K, Uchiyama K, Naito Y, Itoh Y. Elevated ER stress exacerbates dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in PRDX4-knockout mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019 Apr;134:153-164. Epub 2018 Dec 19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto Y, Koh YH, Park YS, Fujiwara N, Sakiyama H, Misonou Y, Ookawara T, Suzuki K, Honke K, Taniguchi N. Oxidative stress caused by inactivation of glutathione peroxidase and adaptive responses. Biol Chem. 2003 Apr;384(4):567-74. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melhem H, Spalinger MR, Cosin-Roger J, Atrott K, Lang S, Wojtal KA, Vavricka SR, Rogler G, Frey-Wagner I. Prdx6 Deficiency Ameliorates DSS Colitis: Relevance of Compensatory Antioxidant Mechanisms. J Crohns Colitis. 2017 Jul 1;11(7):871-884. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu J, Sun L, Chen D, Huo X, Tian X, Li J, Liu M, Yu Z, Zhang B, Yang Y, Qiu Y, Liu Y, Guo H, Zhou C, Ma X, Xiong Y. Prdx6-induced inhibition of ferroptosis in epithelial cells contributes to liquiritin-exerted alleviation of colitis. Food Funct. 2022 Sep 22;13(18):9470-9480. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuqua BK, Vulpe CD, Anderson GJ. Intestinal iron absorption. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2012 Jun;26(2-3):115-9. Epub 2012 May 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi Y, Ohfuji S, Kondo K, Fukushima W, Sasaki S, Kamata N, Yamagami H, Fujiwara Y, Suzuki Y, Hirota Y; Japanese Case-Control Study Group for Ulcerative Colitis. Association between dietary iron and zinc intake and development of ulcerative colitis: A case-control study in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Oct;34(10):1703-1710. Epub 2019 Mar 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner T, Wagner SJ, Martínez I, Walter J, Chang JS, Clavel T, Kisling S, Schuemann K, Haller D. Depletion of luminal iron alters the gut microbiota and prevents Crohn's disease-like ileitis. Gut. 2011 Mar;60(3):325-33. Epub 2010 Nov 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye Y, Liu L, Feng Z, Liu Y, Miao J, Wei X, Li H, Yang J, Cao X, Zhao J. The ERK-cPLA2-ACSL4 axis mediating M2 macrophages ferroptosis impedes mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2024 Mar;214:219-235. Epub 2024 Feb 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding K, Liu C, Li L, Yang M, Jiang N, Luo S, Sun L. Acyl-CoA synthase ACSL4: an essential target in ferroptosis and fatty acid metabolism. Chin Med J (Engl). 2023 Nov 5;136(21):2521-2537. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li X, He J, Gao X, Zheng G, Chen C, Chen Y, Xing Z, Wang T, Tang J, Guo Y, He Y. GPX4 restricts ferroptosis of NKp46+ILC3s to control intestinal inflammation. Cell Death Dis. 2024 Sep 19;15(9):687. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]