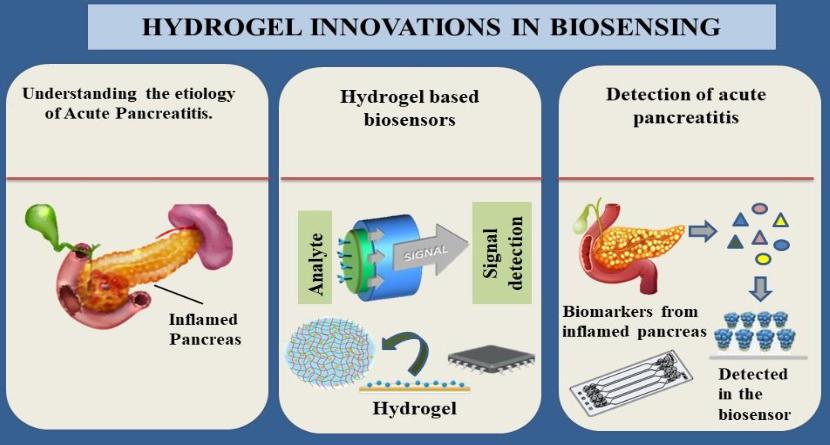

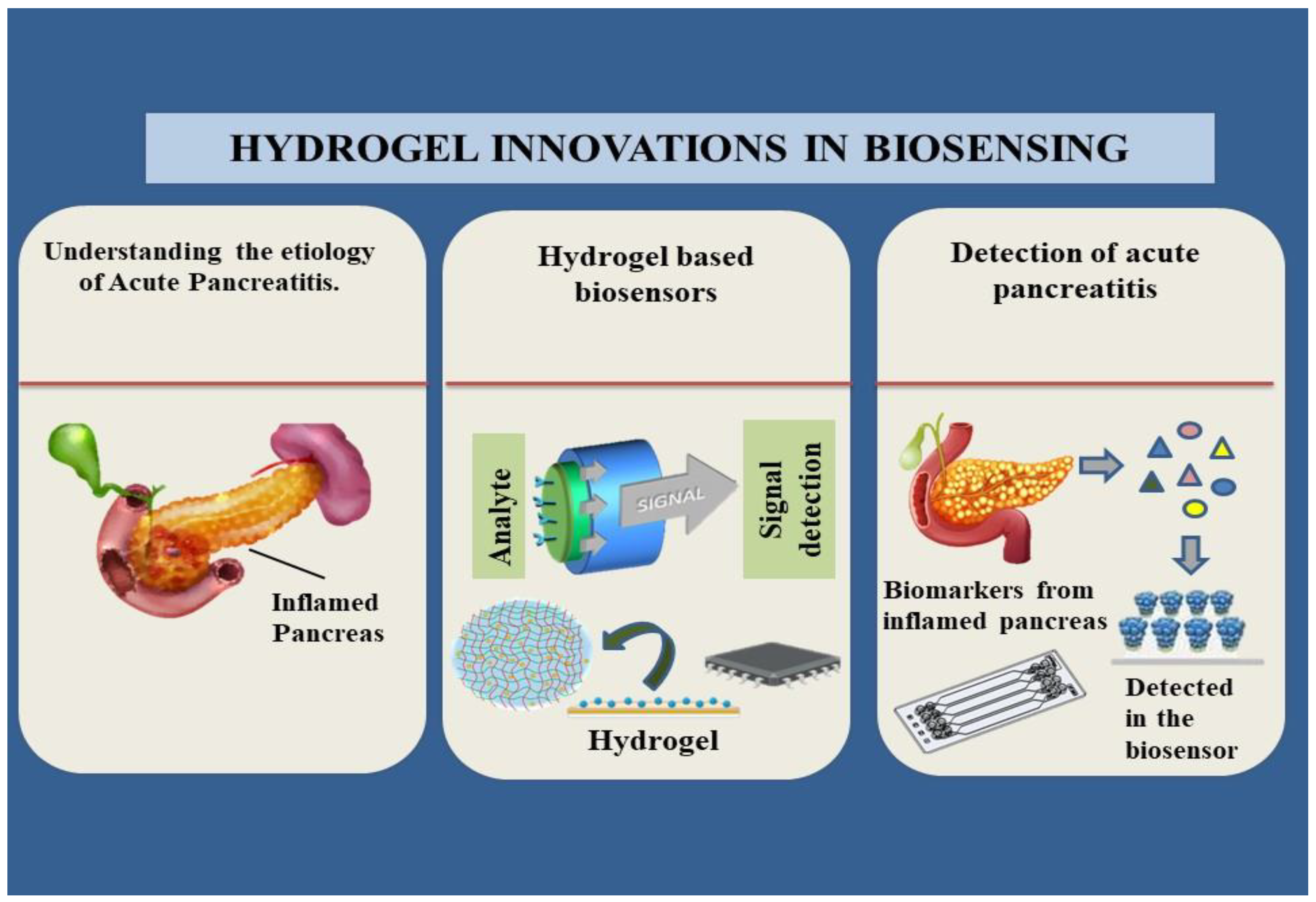

Graphical abstract: The current state of art of hydrogel-based biosensors and their relevance to acute pancreatitis.

1. Introduction

An exocrine pancreatic inflammatory condition linked to tissue damage and necrosis is known as acute pancreatitis. The disease has severity ranging from moderate conditions which have the ability to recover the damage and has a severe variant which leads to extra-pancreatic organ failure which has proven to be fatal (Pandol SJ et al 2007). Currently no pharmacological drugs are available which can alter the progression of disease and only viable option left is early disease management within a time bracket of 72h (Song, Y., & Lee, S. H. 2024). The most frequent cause of acute pancreatitis continues to be gallstones shifting out of the gallbladder and temporarily obstructing the pancreatic duct, exposing the pancreas to biliary substances (Yadav D & Lowenfels AB 2013). Alcohol misuse is the second most common cause of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatitis caused by excessive drinking of alcohol which involves heavy consumption of alcoholic beverages over an extended period of time (~4-5 drinks per day over >5 years) (Coté, G. A. et al. 2011). Alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking go hand in hand, and new research indicates that these behaviors have a major impact on health (Cosen-Binker LI et al.2007). Studies have demonstrated that, in addition to significant alcohol misuse (drinking pattern), smoking (nicotine) is an independent risk factor for acute, recurring, and chronic pancreatitis (Göltl, P. et al .2024). Additionally, the significance of hypertriglyceridemia (HTG) even in mild or moderate amounts is known to aggravate acute pancreatitis thus is recognized as a risk factor (Kiss, L. et al .2023). Acute pancreatitis is estimated to occur in 15%–20% of those with severe hypertriglyceridemia (triglyceride levels >1000 mg/dL) (Adiamah A et al. 2018). These patients have a more severe clinical course and a higher rate of permanent multi-organ failure. Medication-associated pancreatitis is a less prevalent cause of the condition, likely accounting for less than 5% of cases, even though pancreatitis has been linked to several medicines. In rare instances a case report informed that a 36-year-old man arrived at the hospital with acute severe pancreatitis, 4 days after consumption of orlistat, a lipase inhibitor used to treat obesity showing a possibility of even drug-related pancreatitis confirmed by biomedical and scanning tests (Napier, S.& Thomas, M. 2006). Some of the drugs, such as azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, didanosine, valproic acid, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and mesalamine, have been strongly linked to the development of acute pancreatitis (Jones MR et al. 2015). The diagnosis of Pancreatitis is very less common among pediatric population and data that has been emergent due to research has shown that pediatric cases occur due to underlying genetic influences that may influence important digestive enzymes to suffer mutations and thereby contribute as a key factor for pancreatitis (Suzuki M, Sai JK & Shimizu T 2014). The diagnosis of pancreatitis is difficult due to the invasiveness of biopsy procedures which includes risk of damage to the organ, which can lead to increased severity of the disease. Thereby development of a biosensor which could detect potent biomarkers of pancreatitis can bring about a revolution in early detection of disease and thereby have potential lifesaving application.

2. Pancreatitis

2.1. Causes of Pancreatitis

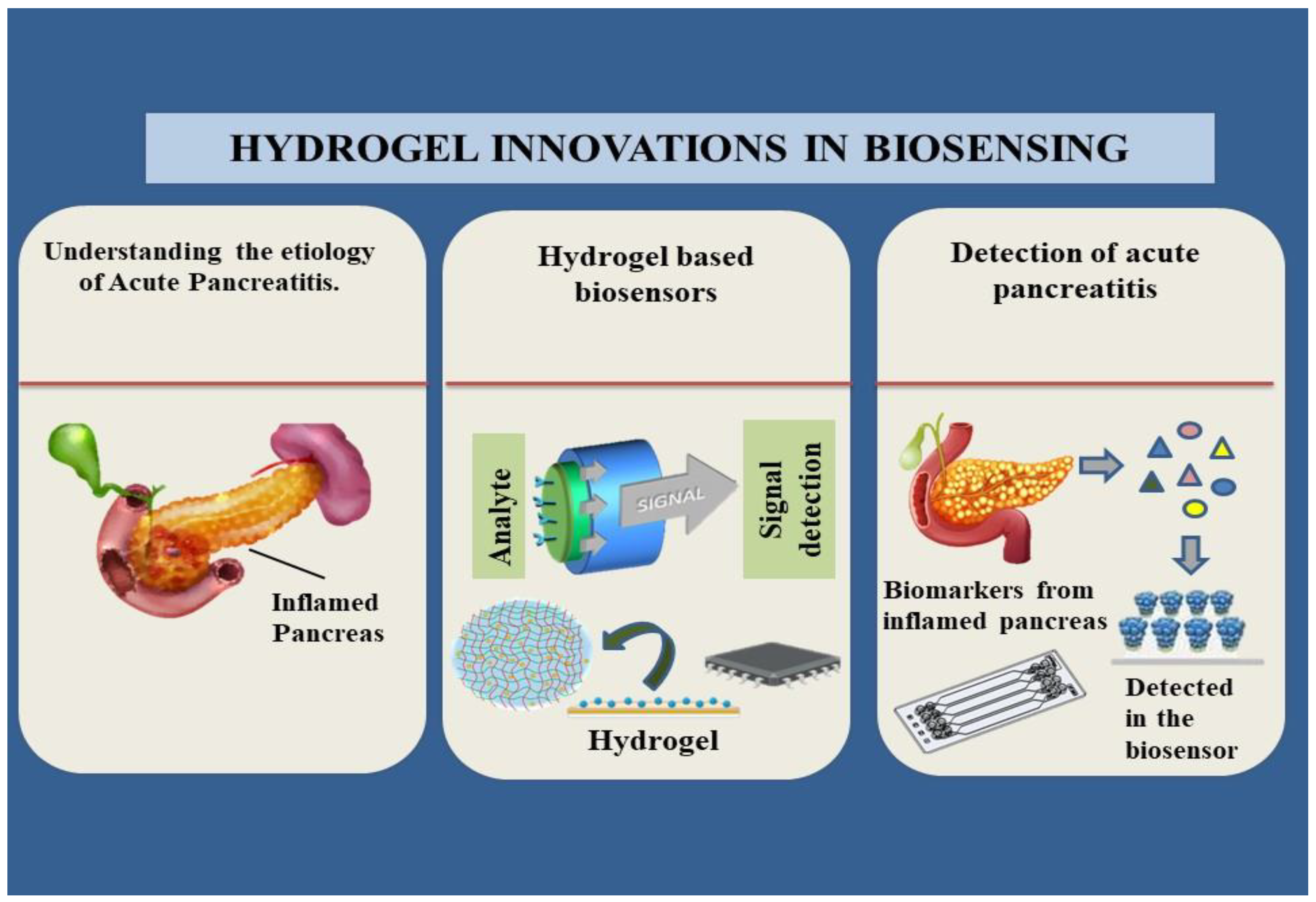

Acute Pancreatitis is the inflammation of the exocrine pancreas which leads to the necrosis of pancreatic tissue. If not resolved spontaneously within days it may result in extra-pancreatic organ failure which could lead to fatal consequences (Mederos MA, Reber HA & Girgis MD 2021). Due to the lack of therapeutic agents currently in use for the treatment of this condition, fluid resuscitation and supportive care to prevent the disease from being severe has been adopted. Numerous factors contribute to the condition, such as autoimmune pancreatitis, hypertriglyceridemia and lifestyle factors as mentioned in

Figure 1; post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), medications, genetic risk (mutations in the CFTR that is Cystic fibrosis trans-membrane conductance regulator protein and SPINK1 – Serine Protease Inhibitor Kazal type 1 genes that cause gain of function), pancreatic duct injury, and genetic risk are among the causes (Lankisch PG, Apte M & Banks PA 2015).

As mentioned before, Hyperglyceridemic pancreatitis is the third leading cause of acute pancreatitis and therefore conditions that could lead up to this should be avoided at all costs (Yang AL & McNabb-Baltar J. 2020). There are a lot of other metabolic factors like hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, hypertension and obesity which when observed in an individual’s lifestyle increase their risk of pancreatitis (Szatmary P et al. 2022). The role of obesity in case of increased body mass index has posed a negative impact and is a possible prognostic factor of acute pancreatitis as the increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and adipokines are relative to the increase of intra-pancreatic fat (Khatua B, El-Kurdi B & Singh VP. 2017). Conditions like fatty liver, diabetes mellitus and hypertension are some factors which contribute to the elevation of the risk of severe acute pancreatitis (AP) (Richardson A & Park WG. 2021). Mechanical causes, toxins and metabolites which are a potential cause of Pancreatitis are included in

Table 1.

2.2. Initiation of Pancreatitis

The most common theory about the pathophysiology of pancreatitis holds that a disruption in the regulation of pancreatic digesting enzymes by pancreatic acinar cells causes an inflammation that is either initiated or maintained (Boxhoorn L et al. 2020)( Lee PJ & Papachristou GI 2019). The digestive enzymes synthesized in pancreatic acinar cells are normally maintained in an inactive form (i.e., zymogens such as trypsinogen) while in the acinar cells and in the draining duct, they are converted to an active form (such as trypsin) upon entry into the gut lumen by enterokinase or trypsin itself (Habtezion A, Gukovskaya AS & Pandol SJ 2019). This information is crucial to understand the mechanism of disruption. Premature intra-acinar cell activation of the dormant enzymes can be attributed to many factors that may lead to auto-digestion of acinar cells, which can then trigger subsequent events that result in persistent pancreatic inflammation (Maatman TK & Zyromski NJ 2021). Trypsinogen autoactivation, activation of trypsinogen by lysosomal hydrolase cathepsin B (CatB) caused by shifting of trypsinogen into cellular compartments rich in proteases (lysosomes), and imbalances between degrading and activating acinar cell cathepsins are some of the mechanisms of such premature and inappropriate activation of normally inactive zymogens that have been proposed (Zierke, L.et al. 2024). It should be mentioned that elevated intracellular calcium concentrations are necessary for the activation of pancreatic proteases; as a result, abnormalities in these concentrations may be a contributing factor in pancreatitis (Krüger B, Albrecht E & Lerch MM 2000).

The breakdown and recycling of cytoplasmic organelles and long-lived proteins occurs during autophagy (Antonucci L et al. 2015). Targeted proteins are engulfed in double-membrane autophagic vacuoles during this process, and when the autophagic vacuoles fuse with lysosomes, they become exposed to proteolytic breakdown. The strongest evidence for this theory comes from studies conducted on mice that have specific deletions of important autophagy genes. For example, (Diakopoulos et al. 2015) study demonstrated that mice with pancreas-specific autophagy-related 5 (ATG5) deficiency develop chronic pancreatitis and exhibit endoplasmic reticulum stress in their acinar cells.

Since ablation of scaffold protein p62 partially corrected alterations are due to deletion of a protein kinase Inhibitory-kB kinase alpha (IKKα), it was assumed that these pathogenic changes, along with the presence of elevated oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress, were caused by accumulation of protein aggregates dependent on p62, a protein ordinarily removed by autophagy (Hennig P et al. 2021). The exact mechanism by which the IKKα deletion affects autophagy remains relatively unknown, however since IKKα interacts to ATG16L2, a malfunctioning autophagy protein, this could be the root cause of the autophagy deficiency.

Pancreatic acinar cell death, a prominent characteristic of pancreatitis, may result from necroptosis or apoptosis (Baer JM et al. 2023). Since necrosis is the predominant cell death mechanism in the related mouse model of cerulein-induced pancreatitis, and apoptosis is the main process in the rat model, there may be some species-dependent variation in which of these death processes is at play (Wang K et al. 2023). The fact that apoptosis and necrosis have different but similar molecular mechanisms is probably connected to these surprising species differences. Tumor Necrosis Factor-α-mediated activation of TNF receptor type 1-associated death domain protein (TRADD)/Fas-associated protein with death domain (FADD) or receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIP1)/RIP3 is the most common mechanism under which apoptosis is mediated under pathological conditions. This is followed by the activation of caspase-8, commonly known as the "executioner" molecule (Saluja A, Dudeja V, Dawra R & Sah RP. 2019). Necroptosis can be triggered by a variety of stimuli that produce TNF-α or, conversely, TLR3 or TLR4 signaling; however, it is unclear under what conditions this type of cell death takes place instead of apoptosis. Since necroptosis is inhibited by caspase-8, it is plausible that necroptosis happens when caspase-8 is either not created or is inactivated; on the other hand, since RIP3 is specifically implicated in necroptosis, it is also feasible that necroptosis occurs when RIP3 is strongly activated. According to these theories, in rat cerulein pancreatitis, caspases are triggered, and RIP is cleaved, however in this model, an endogenous caspase inhibitor (XIAP) is degraded (Watanabe, T., Kudo, M., & Strober, W. 2017).

However, research on inflammation strongly suggests that it most likely stems from the release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) from pancreatic acinar cells that are dying. These DAMPs then trigger inflammation through the innate immune system's pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) being activated. Several types of DAMPs have been identified as pancreatitis-associated “danger signals” (i.e., DAMPs) in human and experimental pancreatitis. These types of DAMPs include high-mobility group box protein 1 (HMGB1), self-DNA, nucleosomes (DNA coiled around histone octamers), and adenosine triphosphate (Zhou, Y. et al.2024). Out of all of them, HMGB1 is particularly noteworthy because (Yasuda et al. 2007) found that animals and individuals suffering from acute pancreatitis had much higher levels of this DAMP.

(Hoque et al. 2012) have clarified a potential molecular mechanism for cerulein-induced pancreatitis that is mediated by DAMPs-PRR interaction. These authors demonstrated that pancreatic macrophage TLR9, an endosome-linked PRR sensitive to bacterial CpG DNA and self-DNA, is activated by self-DNA produced from dying acinar cells during the early stages of cerulein-induced pancreatitis. Simultaneously with this, released adenosine triphosphate activates the purinergic receptor P2X7, which subsequently combines with TLR9 activation to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome and convert pro-IL-1β to mature IL-1β. The AIM2 inflammasome—which is lacking in melanoma 2—has been linked to a DAMP-PRR interaction in pancreatitis, according to recent reports. Nucleosomes, which were previously indicated as potential pro-inflammatory DAMPs in pancreatitis, were the stimulating DAMPs in this instance. According to (Kang et al. 2019) pertinent investigations, nucleosome activation of the AIM2 inflammasome and IL-1β production was necessitated by phosphorylation of dsRNA-activated protein kinase mediated by receptor for advance glycation end products, or RAGE. Furthermore, they discovered that under these conditions, L-arginine-induced pancreatitis is less common in AIM2- and RAGE-deficient animals, and HMGB1 expression—an inflammasome product—is also less common (Strum WB & Boland CR 2023).

2.3. Pathogenesis of Pancreatitis

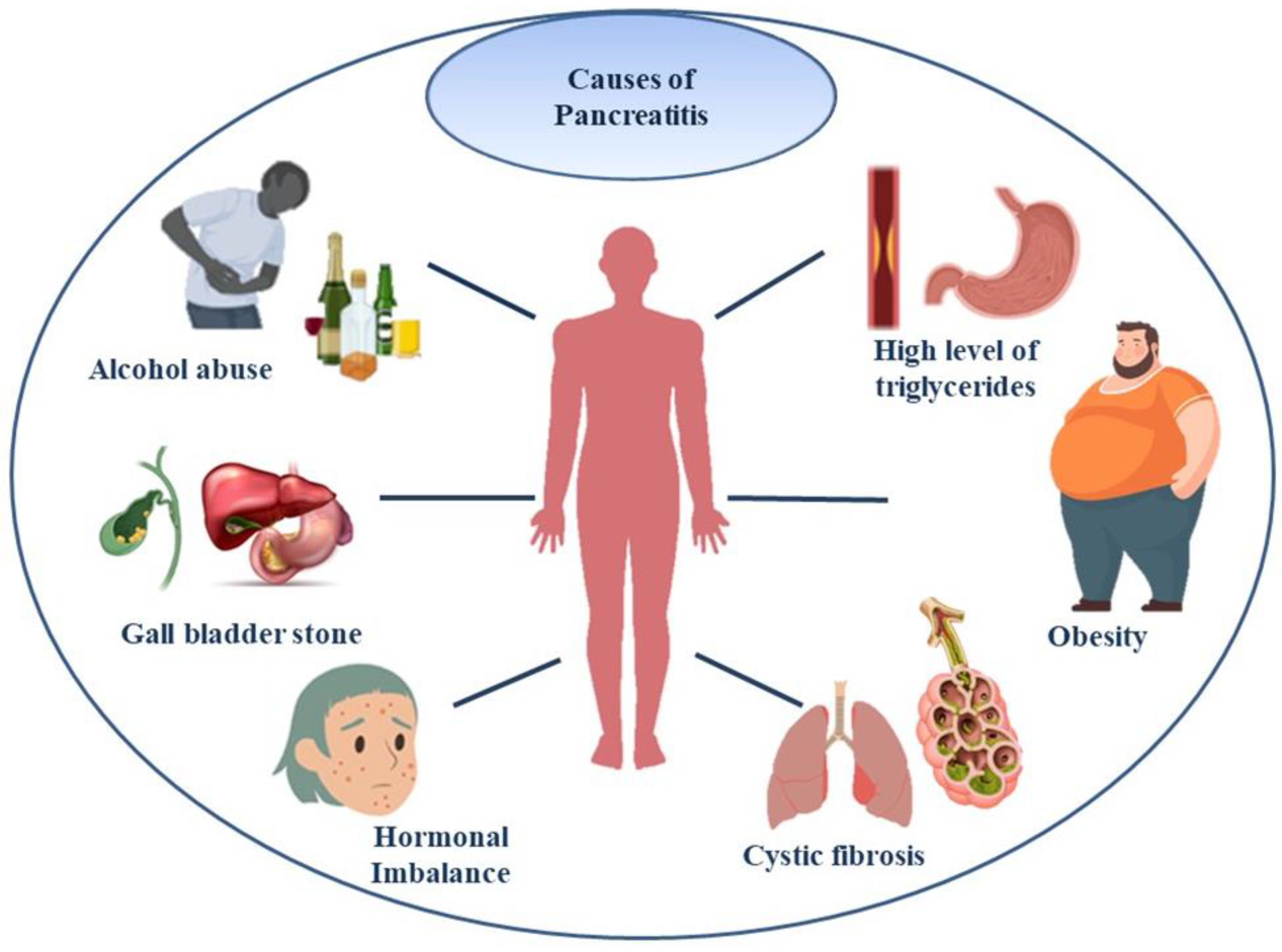

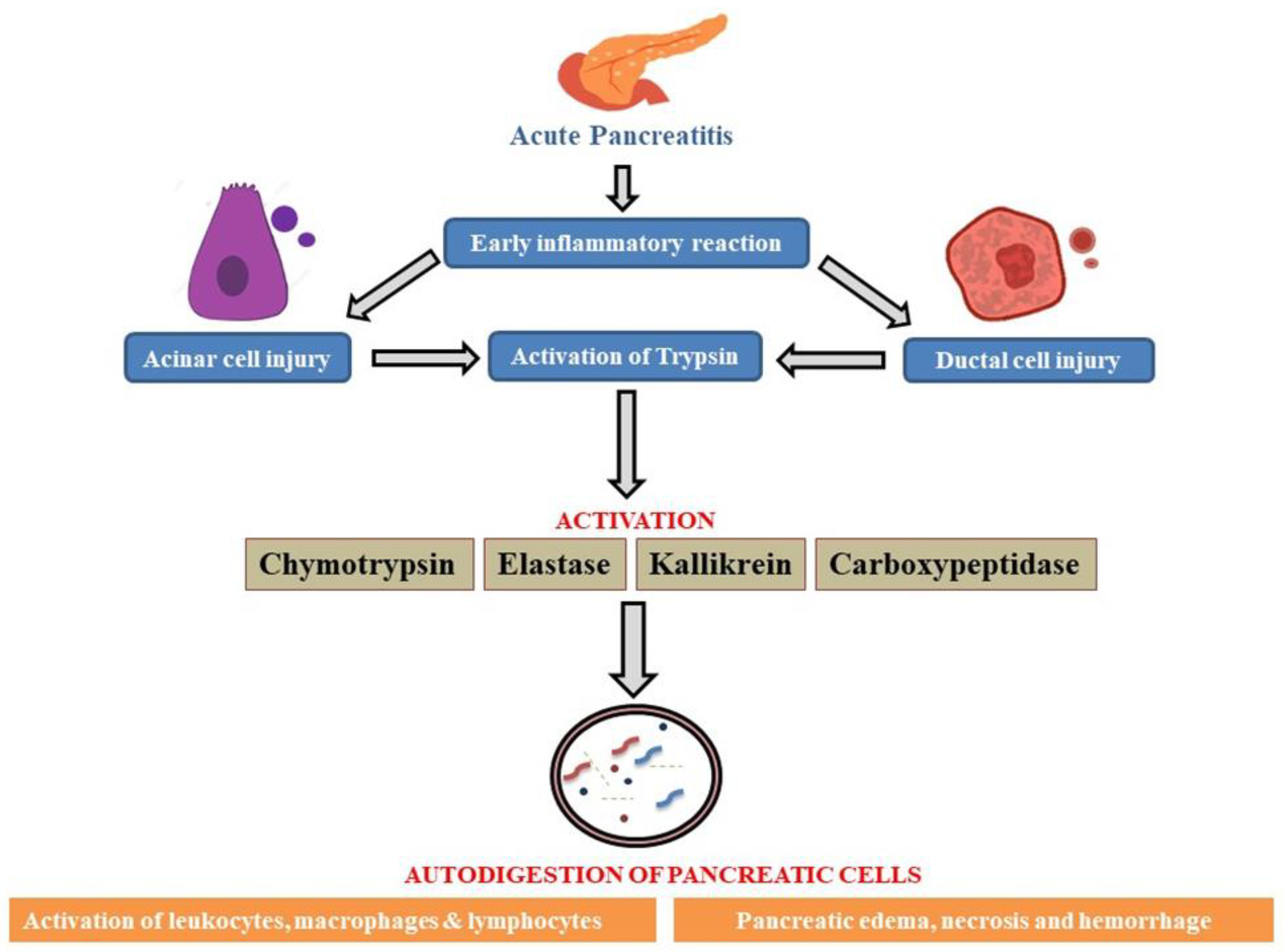

When significant local and systemic problems are evident, acute pancreatitis (AP), a severe pancreatitis, has a high morbidity and death rate. The pathophysiology of AP has been the subject of numerous publications; yet the exact mechanism behind this illness is still unknown but a theoretical pathology has been established as mentioned in

Figure 3 (Wang GJ et al. 2009). Numerous studies carried out in the past few decades have shown that identifying individuals who are at risk of complications or death depends heavily on what happens in the first 24 hours following the onset of symptoms. Gallstones and alcohol are the two most common causes, yet the exact reason is unknown due to its complicated etiology (van Geenen EJM et al. 2010). None of the mechanisms that have been proposed to explain the pathophysiological process of Acute Pancreatitis are particularly clear. A few of the theories include the early activation of trypsin by the acinar and ductal membrane, the attraction and activation of leukocytes, the recruitment of adhesion molecules, cytokines, and oxygen free radicals, all of which result in microcirculatory damage and mitochondrial dysfunction which has been depicted in

Figure 2 (Wang GJ et al. 2010). The characteristic that all mechanisms have in common is an overreaction to inflammation.

As there is relative difficulty in obtaining pancreatic tissue, the scientist has shifted their attention to studying the disease pathology via animal models to investigate the molecular elements of Acute Pancreatitis pathogenesis (Wang GJ et al.2010). The disparate outcomes from various animals and models subjected to a comparable etiology further compound the problem. The most widely accepted idea about the primary mechanism underlying the start of pancreatic tissue auto-digestion and the subsequent onset of systemic and local inflammatory processes is the early activation of trypsin. Its progression is divided into three phases: Local inflammation, generalized inflammatory response and multi-organ dysfunction (Biczo G et al.2018).

Figure illustrates the onset of AP via early inflammatory response leading to pancreatic cellular injury followed by downstream activation of enzymes which promotes autodigestion of pancreatic cells, worsening the patient’s condition with symptoms such as pancreatic edema, tissue necrosis and hemorrhage caused by the rapid inflammation due to activation of leukocytes, macrophages and lymphocytes.

2.4. Biomarkers of Pancreatitis

An essential inflammatory cytokine involved in the pathophysiology of Acute Pancreatitis is tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α along with IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and IL-10 as most relevant biomarkers (Sternby, H. et al.2021), which damages acinar cells directly and causes necrosis, inflammation, and edema. This cytokine is the primary immune response mediator and is believed to be the first cytokine released. The start of experimental Acute Pancreatitis causes an increase in TNF-α expression in the pancreas. It is commonly recognized that interleukin plays a crucial role in the early stages of the pancreatic acute inflammatory process (Yang H et al. 2024). In a study to assess the severity of Acute Pancreatitis, it was discovered that the Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist had the best accuracy among many indicators and that Interleukin-1 levels suggest severe Acute Pancreatitis on admission with accuracy similar to that of Interleukin-6 (82% and 88%, respectively). (Wang et al. 2017), confirmed that after administering L-arginine, there was a significant increase in the concentration of TNF-α in the pancreas. The overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) could be the cause of this, as it triggers the activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), leading to the overexpression of multiple inflammatory cytokines, especially interleukin (IL)-1β and TNF-α. Patients with severe Acute Pancreatitis have been discovered to have elevated levels of TNF-α receptors, which are markers of TNF-α activity (Paajanens H et al. 2005). It has also been demonstrated that TNF-α inhibition lowers mortality and lessens the severity of experimental Acute Pancreatitis.

The primary trigger for acute-phase protein synthesis in the liver is interleukin-6, which also serves as the primary mediator in the production of hepcidin, fibrinogen, and C Reactive Protein (CRP) (Khanna AK et al. 2013). Numerous studies have also confirmed the importance of IL-6 in the early and accurate prediction of pancreatitis severity. CRP is a positive acute-phase reactant that the liver produces in response to inflammation and infection (Piñerúa-Gonsálvez JF et al. 2023). It is triggered by cytokines such as Interleukin-6, and its blood level rises considerably with time. Particularly in cases involving inflammation, it can be utilized for diagnosis, prognosis, therapy monitoring, and death prediction.

Pro-peptide pro-calcitonin (PCT) is produced by thyroid gland G-cells and hepatocytes (Woo SM et al. 2011). Several investigations have confirmed its function as an early biochemical marker in infection, sepsis, and multiorgan failure (Párniczky A et al. 2019). Sepsis, infected pancreatic necrosis, and multiorgan failure are known to be linked to severe acute pneumonia, and preclinical CT (PCT) can be utilized to assess Acute Pancreatitis early on (Woo Su Mi et al.2011). Among the serine proteases present in neutrophil granules is polymorphonuclear (PMN) elastase, proteolytic enzymes, cationic peptides, reactive oxygen species, and eicosanoids are just a few of the microbicidal compounds that are released when granulocytes infiltrate and become activated as a first-line defense after tissue damage (Siriwardena AK et al. 2019). The early stages of Acute Pancreatitis also involve this process (Mofidi R et al. 2009). Endothelial activity is marked by soluble E-selectin (sES), while endothelial damage is marked by soluble thrombomodulin (sTM). Endothelium is harmed by the production of elastases by activated neutrophils during Acute Pancreatitis (Ida et al. 2009).

Hemoconcentration could be a sign of pancreatic microcirculation insufficiency, leading to necrosis. It has been suggested that hemoconcentration at admission, as determined by initial hematocrit, is a helpful prognostic indicator for Acute Pancreatitis (Gan SI & Romagnuolo J.2004). It has been demonstrated that there is a higher chance of necrosis and severe Acute Pancreatitis in cases of early hemoconcentration (Parsa N et al. 2019). It has been confirmed that increased renal permeability occurs following ischemia, burn injuries, trauma, and surgery that causes minimal proteinuria (Schult, L et al. 2023). In many diseases, the degree of proteinuria is correlated with severity and prognosis. A urine dipstick can identify this signal, providing quick and affordable findings. Several investigations have confirmed its function as an early biochemical marker in infection, sepsis, and multi-organ failure (Garg PK & Singh VP 2019)

It is an acute-phase reactant. PCT can be utilized as an early diagnostic test for acute pancreatitis (AP) because severe Acute Pancreatitis is known to be associated with sepsis, infected pancreatic necrosis, and multi-organ failure. It has been discovered that endothelin I (ET-1) levels are elevated in Acute Pancreatitis patients, and that these levels strongly correlate with the severity of the condition (Oz HS et al. 2012). The blood concentration of albumin, a negative acute-phase protein produced by the liver, falls when inflammation increases (Xu X et al. 2020). Because of the connection between inflammation and malnutrition, albumin has also been investigated in relation to the degree of inflammation, the prognosis of the disease, and death. It has also been shown that low ionized calcium (Ca2+) levels in blood serum are a significant factor in the identification of patients with severe pancreatitis. In addition to these biomarkers, other biological factors such as intercellular adhesion molecule (Liu J et al. 2019), histone protein (Ou X et al. 2015), angiopoietin-2 (Orfanos SE et al. 2007), serum Cys-C (Patel ML et al. 2020) creatinine (Uğurlu, E. T., & Tercan, M. 2022), and hemoglobin, to mention a few, are also likely to be strong indicators of pancreatitis (de Pretis N et al. 2022). Summarizing the potential biomarkers for the detection of pancreatitis,

Table 2 mentions cut-off amount and the time of testing for these biomarkers. By incorporating these biological components with their appropriate substrates, we can modify a biosensor technology to aid in the early identification of pancreatitis.

3. Hydrogel Based Biosensor

Hydrogels are three-dimensional, water-swellable structures that are created through physical crosslinking (non-covalent interactions) or chemical crosslinking (covalent bonds) (Hwang HJ et al. 2017). Their molecular interaction with biological components, their regulating viscoelastic properties, their reactivity to external stimuli, their antifouling characteristics, and the availability of numerous well-known synthesis methods for integrating bio-receptors into their highly wet structure are just a few of the features that have made them popular for bio-sensing applications.

Hydrogels are generally biocompatible, and mimic hydrated biological tissues, which presents an amazing possibility for their use as sensing systems (Cao H et al. 2021). As such, they may have applications in vivo. Moreover, the synthetic flexibility of these gels enables chemistry to be fine-tuned to provide desired stimulus responses. These responses provide both indirect (alterations in UV absorption characteristics) and direct (visible color changes) read-outs through degradation and swelling/deswelling (Ahmed B

et al.2024).

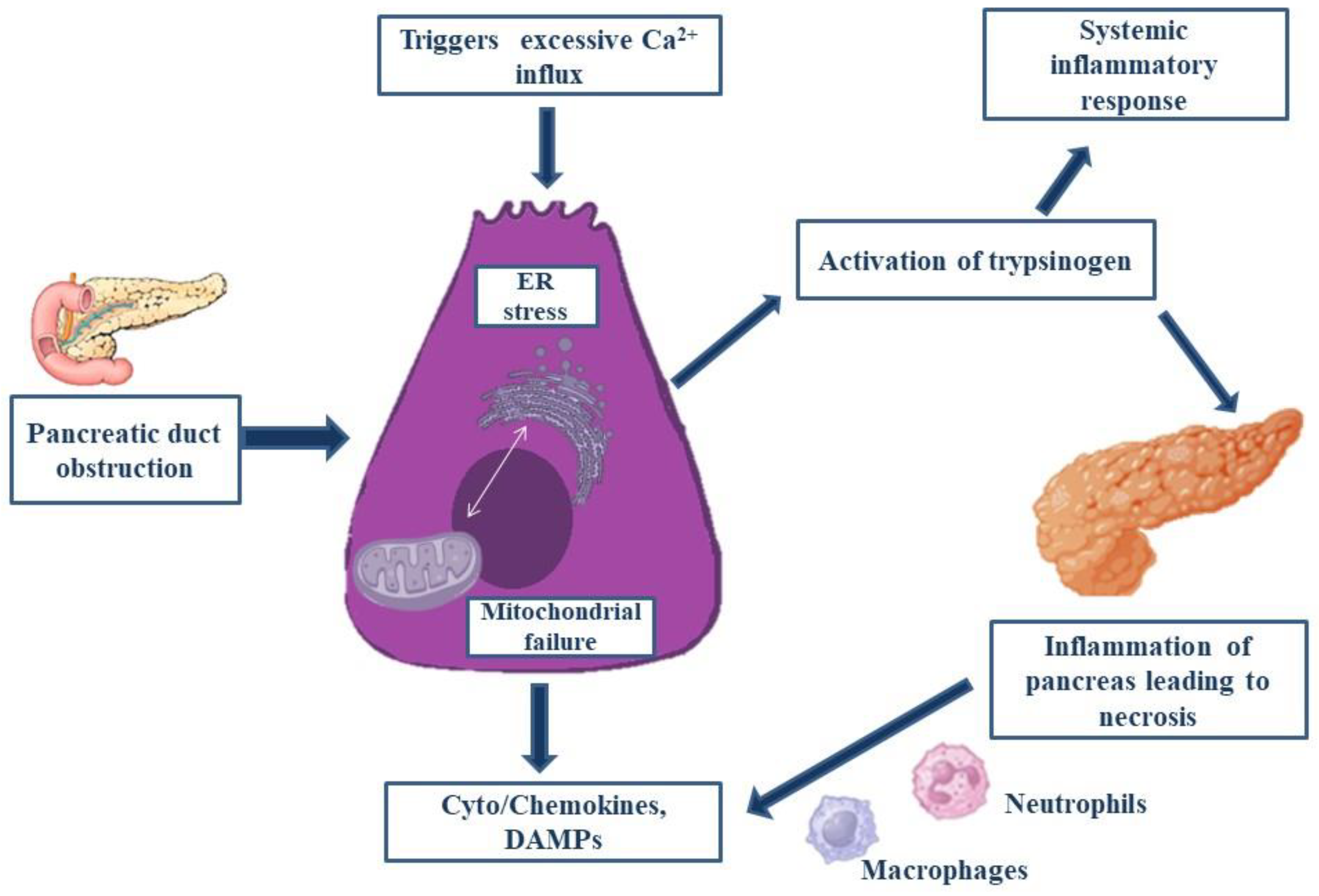

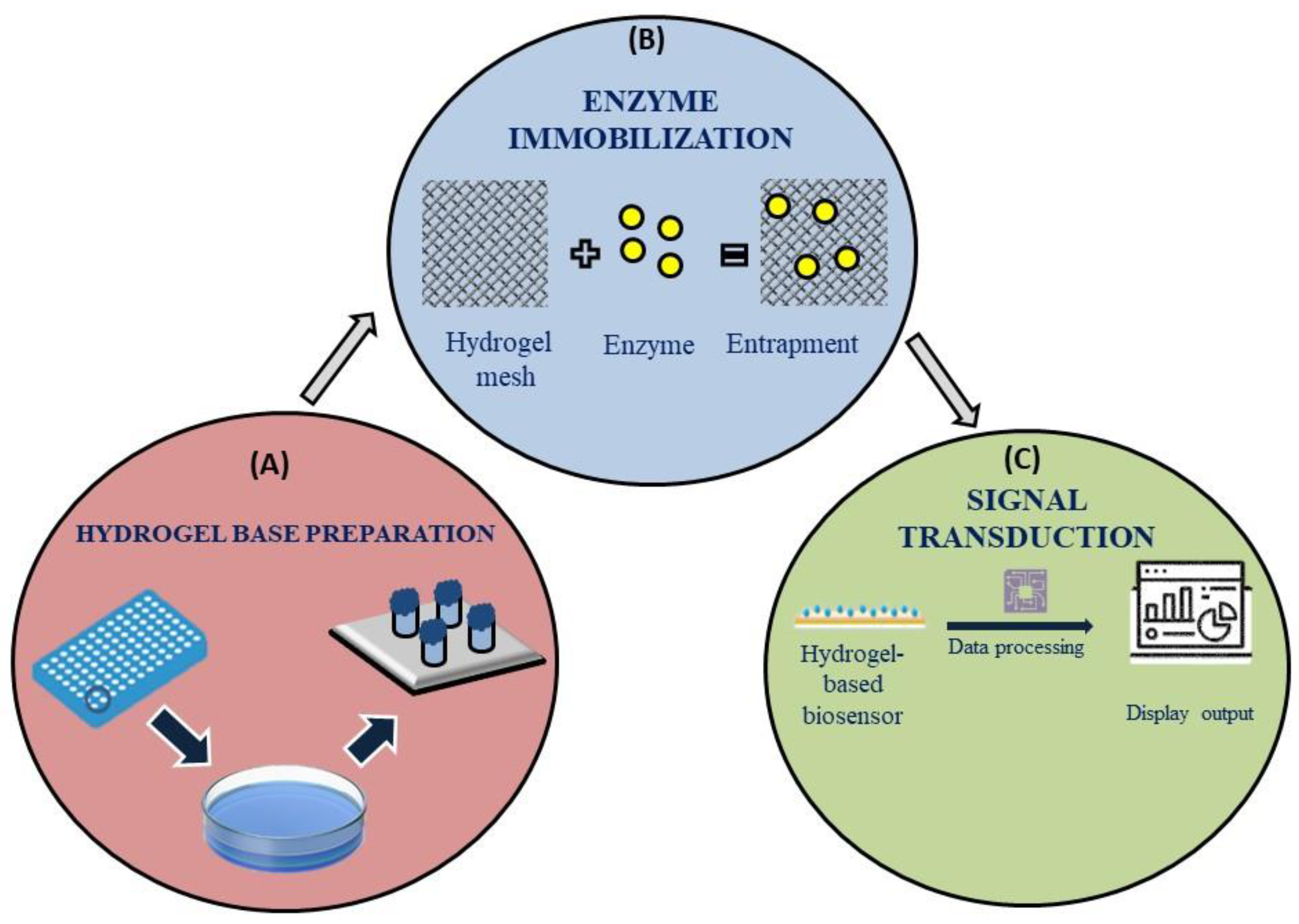

Figure 4 mentions the basic working of a hydrogel based sensor where its discusses about the hydrogel base preparation, enzyme immobilisation and signal transduction. However, the monomer utilized for hydrogel synthesis as well as the preparation techniques employed in its creation determine the properties and possible uses of hydrogels (Zou R et al. 2024). Although hydrogels exhibit great variability in their reaction to a wide range of stimuli, their use in sensing applications necessitates the development of a signal transduction system capable of converting the hydrogel response into a signal that can be understood. An example was the color shift of hydrogels containing embedded nanoparticles or micro-particles when glucose was present in a biosensor for detecting pancreatitis (Govindaraj M et al. 2023). As a result of its many uses, electrochemical-based biosensors have emerged as the most widely utilized kind of biosensors.

The hydrogel-based sensors operate via (a) creation of a hydrogel base (b) Immobilization of enzymes and their reaction with target biomarkers in test fluid (c) The display of signal using sophisticated signal transducing apparatus.

Hydrogels have shown promise as an immobilization matrix for the bio-sensing components in electrochemical-based biosensors (Wei Y et al. 2019). Their three-dimensional design increases the amount of recognition factors by offering a larger surface area. Furthermore, hydrogels function well in physiological setting, which enables them to monitor biological events in vivo with little interference from the biological activity. The liquid crystal (LC)- based sensors, due to their advantageous properties of simplified operations, low cost and high sensitivity they have a faster operation time. The molecules present at the LC interface can sense the biomarker molecules, amplify them and transduce into optical signals which can be detected. LC-based Biosensors have been curated to detect different types of biomolecules like DNA, enzymes and proteins (Ryu JJ & Jang CH. 2023). However, it is always a necessary step to have elaborate sample preparation and multiple washing steps to acquire proper results in the detection of the biomolecule. Therefore, it is an essential demand to develop a biosensor that could minimize such steps and make detection of Pancreatitis easier.

4. Types of Hydrogels

Bio-molecular recognition components are hosted by bio-receptors to uniquely recognize a specific occurrence within a bio-system. Stable bio-receptor immobilization, surface bonding techniques, blocking nonspecific protein adsorption to the hydrogel surface, probe density, flexibility, and swelling kinetics are critical factors in the design of this kind of biosensor (Tavakoli J and Tang Y, 2017).

4.1. Polyvinyl Alcohol

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) has shown promising biocompatibility along with features like high mechanical strength, low friction coefficient and suitable water content plus the ability to be 3D printed make them ideal for biomedical applications (Zhong, Y. et al 2024). PVA hydrogels can resemble soft tissue and reduce inflammation and fibrosis, which is essential for implantable sensors because of their flexibility and stability in a variety of environmental circumstances (Tsai, H. C., & Doong, R. A. 2007).

4.2. Polyethylene Glycol

Because of its low interfacial energy, polyethylene glycol (PEG), a hydrophilic biomaterial, offers strong antifouling capabilities that prevent attachment of proteins and cells to its surface (Muñoz EM et al. 2005). PEG is frequently utilized as a biosensor with antifouling properties due to its biocompatibility (Riedel T et al.2013). PEG and its blends have been used in recent research to create mass-based, electrochemical, and optical biosensors (Lowe S, O’Brien-Simpson NM & Connal LA 2015).

4.3. Poly-Acrylate Families

Sensation-responsive hydrogels, such as poly-acrylic acid, poly-hydroxy-ethyl methacrylate, polyacrylamide, and poly(isopropylacrylamide), are primarily employed in biosystems for temperature and pH sensing (Yin MJ et al. 2016). Ionic hydrogels are hydrophilic materials that can swell and de-swell in response to changes in their environment because of their dependence on charged group density (Majumdar S, Dey J & Adhikari B 2006). Recently adhesive and conductive hydrogels based on polyacrylate composites have been developed which could potentially fucntion as biosensors.( Zhao, Y., & Sun, S. 2024). Fabrication patterning techniques have recently been recognized as a crucial stage of development for increased usage of ionic hydrogels' sensing capabilities, particularly when they're employed without using bioreceptors that have been immobilized.

4.4. Biologically Originated Hydrogels

Biomaterials possessing gel-forming qualities include polysaccharides and polypeptides such as hyaluronic acid, agarose, chitin and chitosan, cellulose, dextran, and alginate (Wang X, et al. 2012). These hydrogels with biological origins have special qualities like hydrophilicity, biocompatibility, and heavy metal ion Chelation, strong protein affinity, and simplicity of surface chemical modification made possible by the comprising easily obtainable materials, inexpensive preparation, suitable mechanical qualities, and reactive functional groups production technique—even in tiny geometries—makes them appealing for biosensor uses (Polyak B, Geresh S & Marks RS. 2004). Tissue regenerative properties of biologically originated hydrogels have also been well documented (Kesharwani, P et al. 2024).

4.5. Electro-Conductive Hydrogels

Because of their special qualities, electro-conductive hydrogels—compositions of hydrated structures with electrical functionality—have drawn interest in the field of biomaterials (Yang M et al. 2017). Such hydrogels have porous hydrogels that offer a wide surface area with higher diffusivity and conductive polymers that help transport electrons across the interface. These hydrogels are important in the field of biosensors technology because of their capacity to conduct electrons with flexibility and processability, as well as the capabilities they acquire through chemical changes (Wu S et al. 2017). When creating conductive hydrogels, the most popular conducting polymers utilized are poly-pyrrole, polyaniline, and poly- (ethylene-dioxy thiophene). Due to their redox activity, electrochemical enzyme-immobilized biosensors react with the bio-system environment in a way that causes electrons to transfer across the electro-conductive hydrogel, producing a current or changing the potential to generate voltage (Nguyen HH et al. 2019). High sensitivity and specificity monitoring of small molecules, like cholesterol and glucose, presents significant prospects for early therapy, primary diagnosis, and improved chronic illness management. A few specifications of hydrogel-based biosensors for the detection of tiny molecules are shown in

Table 3.

5. Using Hydrogel-Based Instruments to Diagnose Pancreatitis Point-of-Care Examinations

Timely and accurate diagnosis of pancreatitis is crucial to initiate appropriate treatment and mitigate complications. Traditional diagnostic methods which include imaging techniques and biochemical assays can be time-consuming and require sophisticated laboratory infrastructure to make sure reliable results are being derived (Smotkin J &Tenner S.2002). However, advancement in biomedical devices and by large hydrogel-based sensors offer a promising solution for point-of-care examinations, providing rapid, reliable and user-friendly diagnostic tools directly at the bedside or in remote settings. In the context of diagnosing a severe disease like pancreatitis, hydrogel-based biosensors can be engineered to detect specific biomarkers associated with the disease as mentioned earlier in this review, enabling accurate POC testing (Simha A et al.2021). Hydrogel based biosensors leverage the interaction between the target biomarker and a functional hydrogel matrix to produce a measurable signal. By keeping an environment moist, alginate, a polysaccharide with a high absorption capacity, helps to reduce wound fluids and enhance wound healing. By utilizing ionic crosslinking, they were able to effectively create alginate-hyaluronan hydrogel, which aids in keratinocyte migration and proliferation (Catanzano O et al. 2015). The hydrogel NU-GELTM is an affordable, transparent, and amorphous gel. Sodium alginate, an ingredient in this hydrogel, efficiently eliminates slough and injured tissue. Additionally, it produces the moisture needed for wound healing. The gel's alginate content raises the absorptive capacity (Aswathy SH 2020). Dr. Derm Professional Collagen Hydrogel is a hydrogel used as a cosmetic product that aids in skin regeneration and restoration of the skin's suppleness, elasticity, and moisture content. Collagen and hyaluronic acid make up this hydrogel. By providing the skin with moisture, hyaluronic acid contributes significantly to skin hydration (Papakonstantinou E, Roth M & Karakiulakis G 2012). In order to postpone photoaging, (Kim et al. 2014) created a liposome in a hydrogel complex system that improved medication penetration through the skin. Thanks to hydrogel technology, which facilitates skin hydration and helps to relax the skin barrier, medication penetration through the skin has been enhanced (Wu Y, Midinov B & White RJ 2019). Bausch & Lomb produces soft contact lenses for both short- and long-sightedness, including SofLens Daily disposable, Ultra Contact lens, PureVision2 HD, iconnect, and New Biotrue®. Additionally, they manufactured contact lenses for astigmatism, such as SofLens Daily Disposable Toric, SofLens Toric, and PureVision 2, and for presbyopia, SofLens Multifocal, Bio real ONEday lens, and Pure Vision 2 (Lichtman JW & Conchello JA.2015).

Hydrogels can be chemically modified to incorporate specific recognition elements, such as antibodies, enzymes, or aptamers (Liu X et al. 2019), that bind selectively to biomarkers such as Hepcidin, Interleukins, C-reactive proteins or pancreatic enzymes like amylase or lipase (Danyuo Y et al. 2019). Upon binding the target biomarker to the recognition element, a change occurs in the hydrogel’s properties such as its swelling behavior or optical characteristics. This change is transduced into a detectable signal, such as color change, fluorescence, or electrochemical response, which could be measured quantitatively (D O’Connell et al.2016). The resulting signal is then read using a portable device, providing immediate feedback on the presence and concentration of the biomarker. Hydrogel-based biosensors often require only small volumes of biological samples, such as blood or urine. This is advantageous in scenarios where sample collection is challenging or when minimizing patient discomfort is a priority.

6. Difficulties and Future Perspectives

Hydrogel biosensors represent a very exciting area of research and technology with a lot of potential but there are several challenges that pose a barrier in their working capacity. Their stability and performance can be affected by environmental conditions like temperature, pH and ionic strength which could reduce their sensitivity. Building a biosensor which is strictly specific to a particular biomarker is a task in itself, therefore, hydrogels need to be tailored to interact specifically with the target analytes and not give false results. While producing hydrogel-based biosensors for biomedical applications one must make sure that they are biocompatible and non-toxic. Inspired by pufferfish, MIT researchers have created an ingestible hydrogel device (Liu X et al. 2019). This fast-acting and highly soluble hydrogel is created by encapsulating polyacrylic acid within a hydrogel membrane composed of polyvinyl alcohol. It can be applied to both prolonged drug release and the measurement of stomach temperature. Other uses for this ingestible hydrogel include monitoring drug habits, measuring bio signals, and seeing the gastrointestinal tract with the use of a tiny camera linked to the device. Prodigiosin, a cancer medication, was released from a thermosensitive P(NIPA) based hydrogel for the treatment of breast cancer, according to (Danyuo et al. 2019) Drug release is greatly influenced by the hydrogel's porosity and crosslinking ratio. Studies of this nature steer a significant impact on drug delivery studies utilizing hydrogels. The fabrication technique in tissue engineering is crucial, and more studies these days are centered on in situ crosslinked hydrogel. By concurrently injecting hydrogel and cells, (D O’Connell C et al. 2016) developed a bio pen that can be used for the in-situ creation of hydrogel scaffolds. Hydrogels have been the subject of in-depth research for tissue engineering applications, although the products' commercialization is still in its early stages.

Ensuring that the materials used are safe for long term use for biological systems is crucial. Hydrogels can degrade over time which would affect the lifespan and reliability of the biosensor, so it is essential that hydrogels with improved durability are developed. Keeping these particular facts in mind, future research may focus on developing new hydrogel materials with enhanced properties such as better mechanical strength, chemical stability to increase shelf life, and improved biocompatibility. Development of smart hydrogels that can respond dynamically to environmental changes are also a promising area in the future perspective of this research. Advances in the fields of nanotechnology and micro-fabrication could lead to more precise and scalable production of hydrogel-based biosensors. Techniques like 3D printing may also enable more complex sensor designs. To increase the sensitivity and functionalization of hydrogel biosensors, the incorporation of new types of recognition elements or single transducers apart from fluorescent tags could be an essential step. Apart from the initial idea of a point-of-care kit for the hydrogel-based biosensor, the development of flexible and wearable biosensors using hydrogels could lead to new applications in the detection of diseases as severe as pancreatitis.

Ensuring that the materials used are safe for long term use for biological systems is crucial. Hydrogels can degrade over time which would affect the lifespan and reliability of the biosensor, so it is essential that hydrogels with improved durability are developed. Keeping these particular facts in mind, future research may focus on developing new hydrogel materials with enhanced properties such as better mechanical strength, chemical stability to increase shelf life, and improved biocompatibility. Development of smart hydrogels that can respond dynamically to environmental changes are also a promising area in the future perspective of this research. Advances in the fields of nanotechnology and micro-fabrication could lead to more precise and scalable production of hydrogel-based biosensors. Techniques like 3D printing may also enable more complex sensor designs. To increase the sensitivity and functionalization of hydrogel biosensors, the incorporation of new types of recognition elements or single transducers apart from fluorescent tags could be an essential step. Apart from the initial idea of a point-of-care kit for the hydrogel-based biosensor, the development of flexible and wearable biosensors using hydrogels could lead to new applications in the detection of diseases as severe as pancreatitis.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

Hydrogel based Biosensors offer a promising frontier for the detection and management of pancreatitis due to their unique properties including high water content, biocompatibility, and adaptability which make them well suited for developing sensitive and reliable diagnostic tools. The ability to integrate functional elements which would act as substrates for the tagging of biomarkers associated with pancreatitis potentially lead to early diagnosis and effective monitoring of the disease. Despite the exciting potential, there are still challenges to address such as improving the stability and specificity of these biosensors and ensuring their practical application in clinical settings without the possibility of an anomaly in the results shown by it to maximize the efficiency of the biosensor. Continued research and development on this aspect will likely increase the performance of hydrogel-based biosensors, making them an asset in the detection and treatment of pancreatitis. As we look forward, the integration of these biosensors into routine clinical practice could revolutionize how we diagnose and manage this debilitating condition, ultimately leading to better patient outcomes and advancements in personalized medicine. Hydrogel-based biosensors are a novel and promising method for pancreatitis diagnosis and treatment. These biosensors produce highly sensitive and targeted diagnostic tools by combining cutting-edge sensing technology with the biocompatibility, adjustable characteristics, and flexibility of hydrogels. Their reactivity to biological stimuli, including enzymes or pancreatitis-related indicators, improve real-time monitoring and early identification. Furthermore, new potential for point-of-care diagnostics is presented by the integration of hydrogel biosensors with wearable and portable devices, which can improve patient outcomes by implementing prompt interventions. These devices could be further optimized by future developments in material design and sensor integration, which would make them indispensable for the clinical diagnosis and treatment of pancreatitis.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the School of Health Sciences at UPES for equipping us with the knowledge and confidence to pursue scientific writing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adiamah A, Psaltis E, Crook M, Lobo DN. A systematic review of the epidemiology, pathophysiology and current management of hyperlipidaemic pancreatitis. Clin Nutr. 2018;37(6, Part A):1810-1822. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed B, Reiche CF, Magda JJ, Solzbacher F, Körner J. Smart Hydrogel Swelling State Detection Based on a Power-Transfer Transduction Principle. ACS Appl Polym Mater. 2024;6(9):5544-5554. [CrossRef]

- Antonucci L, Fagman JB, Kim JY, et al. Basal autophagy maintains pancreatic acinar cell homeostasis and protein synthesis and prevents ER stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(45):E6166-74. [CrossRef]

- Arabul M, Celik M, Aslan O, et al. Hepcidin as a predictor of disease severity in acute pancreatitis: a single center prospective study. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60(123):595-600. [CrossRef]

- Aswathy SH, Narendrakumar U, Manjubala I. Commercial hydrogels for biomedical applications. Heliyon. 2020;6(4). [CrossRef]

- Baer JM, Zuo C, Kang LI, et al. Fibrosis induced by resident macrophages has divergent roles in pancreas inflammatory injury and PDAC. Nat Immunol. 2023;24(9):1443-1457. [CrossRef]

- Biczo G, Vegh ET, Shalbueva N, et al. Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Through Impaired Autophagy, Leads to Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress, Deregulated Lipid Metabolism, and Pancreatitis in Animal Models. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(3):689-703. [CrossRef]

- Bornhoeft LR, Biswas A, McShane MJ. Composite Hydrogels with Engineered Microdomains for Optical Glucose Sensing at Low Oxygen Conditions. Biosensors. 2017;7(1). [CrossRef]

- Brahim S, Narinesingh D, Guiseppi-Elie A. Amperometric determination of cholesterol in serum using a biosensor of cholesterol oxidase contained within a polypyrrole–hydrogel membrane. Anal Chim Acta. 2001;448(1):27-36. [CrossRef]

- Cao H, Duan L, Zhang Y, Cao J, Zhang K. Current hydrogel advances in physicochemical and biological response-driven biomedical application diversity. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):426. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso FS, Ricardo LB, Oliveira AM, et al. C-reactive protein prognostic accuracy in acute pancreatitis: timing of measurement and cutoff points. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25(7). https://journals.lww.com/eurojgh/fulltext/2013/07000/c_reactive_protein_prognostic_accuracy_in_acute.5.aspx.

- Catanzano O, D’Esposito V, Acierno S, et al. Alginate–hyaluronan composite hydrogels accelerate wound healing process. Carbohydr Polym. 2015;131:407-414. [CrossRef]

- Cosen-Binker LI, Lam PPL, Binker MG, Reeve J, Pandol S, Gaisano HY. Alcohol/Cholecystokinin-evoked Pancreatic Acinar Basolateral Exocytosis Is Mediated by Protein Kinase Cα Phosphorylation of Munc18c*. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(17):13047-13058. [CrossRef]

- Coté, G. A., Yadav, D., Slivka, A., Hawes, R. H., Anderson, M. A., Burton, F. R., ... & North American Pancreatitis Study Group. (2011). Alcohol and smoking as risk factors in an epidemiology study of patients with chronic pancreatitis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 9(3), 266-273.

- D O’Connell C, Di Bella C, Thompson F, et al. Development of the Biopen: a handheld device for surgical printing of adipose stem cells at a chondral wound site. Biofabrication. 2016;8(1):15019.

- Danyuo Y, Ani CJ, Salifu AA, et al. Anomalous release kinetics of prodigiosin from poly-N-isopropyl-acrylamid based hydrogels for the treatment of triple negative breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):3862.

- de Pretis N, Amodio A, De Marchi G, Marconato E, Ciccocioppo R, Frulloni L. The role of serological biomarkers in the diagnosis and management of autoimmune pancreatitis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2022;18(11):1119-1124. [CrossRef]

- Diakopoulos KN, Lesina M, Wörmann S, et al. Impaired autophagy induces chronic atrophic pancreatitis in mice via sex- and nutrition-dependent processes. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(3):626-638.e17. [CrossRef]

- Gan SI, Romagnuolo J. Admission Hematocrit: A Simple, Useful and Early Predictor of Severe Pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49(11):1946-1952. [CrossRef]

- Garg PK, Singh VP. Organ Failure Due to Systemic Injury in Acute Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(7):2008-2023. [CrossRef]

- Göltl, P., Murillo, K., Simsek, O., Wekerle, M., Ebert, M. P., Schneider, A., & Hirth, M. (2024). Impact of alcohol and smoking cessation on the course of chronic pancreatitis. Alcohol, 119, 29-35.

- Govindaraj M, Srivastava A, Muthukumaran MK, et al. Current advancements and prospects of enzymatic and non-enzymatic electrochemical glucose sensors. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;253(Pt 2):126680. [CrossRef]

- Habtezion A, Gukovskaya AS, Pandol SJ. Acute Pancreatitis: A Multifaceted Set of Organelle and Cellular Interactions. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(7):1941-1950. [CrossRef]

- Han, T., Cheng, T., Liao, Y., He, Y., Liu, B., Lai, Q., ... & Yu, H. (2022). The ratio of red blood cell distribution width to serum calcium predicts severity of patients with acute pancreatitis. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 53, 190-195.

- Hennig P, Fenini G, Di Filippo M, Karakaya T, Beer H-D. The Pathways Underlying the Multiple Roles of p62 in Inflammation and Cancer. Biomedicines. 2021; 9(7):707. [CrossRef]

- Hoque R, Malik AF, Gorelick F, Mehal WZ. Sterile inflammatory response in acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2012;41(3):353-357. [CrossRef]

- Hwang HJ, Ryu MY, Park CY, et al. High sensitive and selective electrochemical biosensor: Label-free detection of human norovirus using affinity peptide as molecular binder. Biosens Bioelectron. 2017;87:164-170. [CrossRef]

- Ida, S., Fujimura, Y., Hirota, M., Imamura, Y., Ozaki, N., Suyama, K., Hashimoto, D., Ohmuraya, M., Tanaka, H., Takamori, H., & Baba, H. (2009). Significance of endothelial molecular markers in the evaluation of the severity of acute pancreatitis. Surgery today, 39(4), 314–319. [CrossRef]

- Jones MR, Hall OM, Kaye AM, Kaye AD. Drug-induced acute pancreatitis: a review. Ochsner J. 2015;15(1):45-51.

- Kang R, Chen R, Xie M, et al. The Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products Activates the AIM2 Inflammasome in Acute Pancreatitis. J Immunol. 2016;196(10):4331-4337. [CrossRef]

- Kesharwani, P., Alexander, A., Shukla, R., Jain, S., Bisht, A., Kumari, K., ... & Sharma, S. (2024). Tissue regeneration properties of hydrogels derived from biological macromolecules: A review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 132280.

- Khamdamov, B. Z., Ganiev, A. A., & Khamdamov, I. B. (2023). The role of cytokines in the immunopatogenesis of acute pancreatitis. Journal of Survey in Fisheries Sciences, 10(2S), 3949-3958.

- Khanna AK, Meher S, Prakash S, et al. Comparison of Ranson, Glasgow, MOSS, SIRS, BISAP, APACHE-II, CTSI Scores, IL-6, CRP, and procalcitonin in predicting severity, organ failure, pancreatic necrosis, and mortality in acute pancreatitis. HPB Surg. 2013;2013. [CrossRef]

- Khatua B, El-Kurdi B, Singh VP. Obesity and pancreatitis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2017;33(5):374-382. [CrossRef]

- Kim SJ, Kwon SS, Jeon SH, Yu ER, Park SN. Enhanced skin delivery of liquiritigenin and liquiritin-loaded liposome-in-hydrogel complex system. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2014;36(6):553-560.

- Kimita, W., Ko, J., Li, X., Bharmal, S. H., & Petrov, M. S. (2022). Associations between iron homeostasis and pancreatic enzymes after an attack of pancreatitis. Pancreas, 51(10), 1277-1283.

- Kiss, L., Fűr, G., Pisipati, S., Rajalingamgari, P., Ewald, N., Singh, V., & Rakonczay Jr, Z. (2023). Mechanisms linking hypertriglyceridemia to acute pancreatitis. Acta Physiologica, 237(3), e13916.

- Krüger B, Albrecht E, Lerch MM. The role of intracellular calcium signaling in premature protease activation and the onset of pancreatitis. Am J Pathol. 2000;157(1):43-50. [CrossRef]

- Kwan RCH, Hon PYT, Mak KKW, Renneberg R. Amperometric determination of lactate with novel trienzyme/poly(carbamoyl) sulfonate hydrogel-based sensor. Biosens Bioelectron. 2004;19(12):1745-1752. [CrossRef]

- Lankisch PG, Apte M, Banks PA. Acute pancreatitis. Lancet (London, England). 2015;386(9988):85-96. [CrossRef]

- Lee PJ, Papachristou GI. New insights into acute pancreatitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(8):479-496. [CrossRef]

- Lichtman JW, Conchello JA. Fluorescence microscopy. Nat Methods. 2005;2(12):910-919. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Wang G, Liu Y, Huang L, Xu X, Wang J. Effects of Somatostatin Combined with Pantoprazole on Serum C-Reactive Protein and Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1 in Severe Acute Pancreatitis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2019;29(7):683-684. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Steiger C, Lin S, et al. Ingestible hydrogel device. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):493.

- Lowe S, O’Brien-Simpson NM, Connal LA. Antibiofouling polymer interfaces: poly(ethylene glycol) and other promising candidates. Polym Chem. 2015;6(2):198-212. [CrossRef]

- Ma WJ, Luo CH, Lin JL, et al. A Portable Low-Power Acquisition System with a Urease Bioelectrochemical Sensor for Potentiometric Detection of Urea Concentrations. Sensors (Basel). 2016;16(4). [CrossRef]

- Maatman TK, Zyromski NJ. Chronic Pancreatitis. Curr Probl Surg. 2021;58(3):100858. [CrossRef]

- Majumdar S, Dey J, Adhikari B. Taste sensing with polyacrylic acid grafted cellulose membrane. Talanta. 2006;69(1):131-139. [CrossRef]

- Mano N, Yoo JE, Tarver J, Loo YL, Heller A. An electron-conducting cross-linked polyaniline-based redox hydrogel, formed in one step at pH 7.2, wires glucose oxidase. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129(22):7006-7007. [CrossRef]

- Mederos MA, Reber HA, Girgis MD. Acute Pancreatitis: A Review. JAMA. 2021;325(4):382-390. [CrossRef]

- Mofidi R, Suttie SA, Patil P V, Ogston S, Parks RW. The value of procalcitonin at predicting the severity of acute pancreatitis and development of infected pancreatic necrosis: systematic review. Surgery. 2009;146(1):72-81. [CrossRef]

- Mumin, A., Abdullah Al Amin, A. K. M., Kabir, S., Noor, R. A., & Rahman, U. (2024). Role of C-Reactive Protein (CRP) and Neutrophil Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) in detecting severity & Predicting outcome of Acute Pancreatitis patients. Dinkum Journal of Medical Innovations, 3(01), 01-12.

- Muñoz EM, Yu H, Hallock J, Edens RE, Linhardt RJ. Poly(ethylene glycol)-based biosensor chip to study heparin-protein interactions. Anal Biochem. 2005;343(1):176-178. [CrossRef]

- Napier S, Thomas M. 36-year-old man presenting with pancreatitis and a history of recent commencement of Orlistat case report. Nutr J. 2006;5:19. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen HH, Lee SH, Lee UJ, Fermin CD, Kim M. Immobilized Enzymes in Biosensor Applications. Materials (Basel). 2019;12(1). [CrossRef]

- Orfanos SE, Kotanidou A, Glynos C, et al. Angiopoietin-2 is increased in severe sepsis: Correlation with inflammatory mediators. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(1). https://journals.lww.com/ccmjournal/fulltext/2007/01000/angiopoietin_2_is_increased_in_severe_sepsis_.29.aspx.

- Ou X, Cheng Z, Liu T, et al. Circulating Histone Levels Reflect Disease Severity in Animal Models of Acute Pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2015;44(7). https://journals.lww.com/pancreasjournal/fulltext/2015/10000/circulating_histone_levels_reflect_disease.12.aspx.

- Oz HS, Lu Y, Vera-Portocarrero LP, Ge P, Silos-Santiago A, Westlund KN. Gene expression profiling and endothelin in acute experimental pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(32):4257-4269. [CrossRef]

- Paajanens H, Laato M, Jaakkola M, Pulkki K, Niinikoski J, Nordback I. Serum tumour necrosis factor compared with C-reactive protein in the early assessment of severity of acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2005;82(2):271-273. [CrossRef]

- Pandol SJ, Saluja AK, Imrie CW, Banks PA. Acute Pancreatitis: Bench to the Bedside. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(3):1127-1151. [CrossRef]

- Papakonstantinou E, Roth M, Karakiulakis G. A key molecule in skin aging Hyaluronic acid. Dermatoendocrinology. 2012;4(3):253-258.

- Párniczky A, Lantos T, Tóth EM, et al. Antibiotic therapy in acute pancreatitis: From global overuse to evidence based recommendations. Pancreatology. 2019;19(4):488-499. [CrossRef]

- Parsa N, Faghih M, Garcia Gonzalez F, et al. Early Hemoconcentration Is Associated With Increased Opioid Use in Hospitalized Patients With Acute Pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2019;48(2):193-198. [CrossRef]

- Patel, M. L., Shyam, R., Bharti, H., Sachan, R., Gupta, K. K., & Parihar, A. (2020). Evaluation of serum cystatin C as an early biomarker of acute kidney injury in patients with acute pancreatitis. Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine: Peer-reviewed, Official Publication of Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine, 24(9), 777.

- Piñerúa-Gonsálvez JF, Ruiz Rebollo ML, Zambrano-Infantino RDC, Rizzo-Rodríguez MA, Fernández-Salazar L. Value of CRP/albumin ratio as a prognostic marker of acute pancreatitis: a retrospective study. Rev Esp enfermedades Dig. 2023;115(12):707-712. [CrossRef]

- Polyak B, Geresh S, Marks RS. Synthesis and characterization of a biotin-alginate conjugate and its application in a biosensor construction. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5(2):389-396. [CrossRef]

- Rahman MM, Li X bo, Kim J, Lim BO, Ahammad AJS, Lee JJ. A cholesterol biosensor based on a bi-enzyme immobilized on conducting poly(thionine) film. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2014;202:536-542. [CrossRef]

- Reiter S, Habermüller K, Schuhmann W. A reagentless glucose biosensor based on glucose oxidase entrapped into osmium-complex modified polypyrrole films. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2001;79(2):150-156. [CrossRef]

- Riedel T, Riedelová-Reicheltová Z, Májek P, et al. Complete identification of proteins responsible for human blood plasma fouling on poly(ethylene glycol)-based surfaces. Langmuir. 2013;29(10):3388-3397. [CrossRef]

- Romero MR, Garay F, Baruzzi AM. Design and optimization of a lactate amperometric biosensor based on lactate oxidase cross-linked with polymeric matrixes. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2008;131(2):590-595. [CrossRef]

- Russell RJ, Pishko M V, Gefrides CC, McShane MJ, Coté GL. A fluorescence-based glucose biosensor using concanavalin A and dextran encapsulated in a poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogel. Anal Chem. 1999;71(15):3126-3132. [CrossRef]

- Saluja A, Dudeja V, Dawra R, Sah RP. Early Intra-Acinar Events in Pathogenesis of Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(7):1979-1993. [CrossRef]

- Schult, L., Halbgebauer, R., Karasu, E., & Huber-Lang, M. (2023). Glomerular injury after trauma, burn, and sepsis. Journal of nephrology, 36(9), 2417-2429.

- Shumyantseva V, Deluca G, Bulko T, et al. Cholesterol amperometric biosensor based on cytochrome P450scc. Biosens Bioelectron. 2004;19(9):971-976. [CrossRef]

- Simha A, Saroch A, Pannu AK, et al. Utility of point-of-care urine trypsinogen dipstick test for diagnosing acute pancreatitis in an emergency unit. Biomark Med. 2021;15(14):1271-1276. [CrossRef]

- Siriwardena AK, Jegatheeswaran S, Mason JM, et al. PROCalcitonin-based algorithm for antibiotic use in Acute Pancreatitis (PROCAP): Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20(1):1-11. [CrossRef]

- Smotkin J, Tenner S. Laboratory diagnostic tests in acute pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34(4):459-462. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y., & Lee, S. H. (2024). Recent Treatment Strategies for Acute Pancreatitis. Journal of clinical medicine, 13(4), 978.

- Soylemez S, Udum YA, Kesik M, Gündoʇdu Hizliateş C, Ergun Y, Toppare L. Electrochemical and optical properties of a conducting polymer and its use in a novel biosensor for the detection of cholesterol. Sensors Actuators, B Chem. 2015;212:425-433. [CrossRef]

- Sternby, H., Hartman, H., Thorlacius, H., & Regnér, S. (2021). The initial course of IL1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IFN-γ and TNF-α with regard to severity grade in acute pancreatitis. Biomolecules, 11(4), 591.

- Strum WB, Boland CR. Advances in acute and chronic pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29(7):1194-1201. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki M, Sai JK, Shimizu T. Acute pancreatitis in children and adolescents. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2014;5(4):416-426. [CrossRef]

- Szatmary P, Grammatikopoulos T, Cai W, et al. Acute Pancreatitis: Diagnosis and Treatment. Drugs. 2022;82(12):1251-1276. [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli J, Tang Y. Hydrogel Based Sensors for Biomedical Applications: An Updated Review. Polymers. 2017; 9(8):364. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H. C., & Doong, R. A. (2007). Preparation and characterization of urease-encapsulated biosensors in poly (vinyl alcohol)-modified silica sol–gel materials. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 23(1), 66-73.

- Uğurlu, E. T., & Tercan, M. (2022). The role of biomarkers in the early diagnosis of acute kidney injury associated with acute pancreatitis: Evidence from 582 cases. Ulusal travma ve acil cerrahi dergisi= Turkish journal of trauma & emergency surgery: TJTES, 29(1), 81-93.

- van Geenen EJM, van der Peet DL, Bhagirath P, Mulder CJJ, Bruno MJ. Etiology and diagnosis of acute biliary pancreatitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7(9):495-502. [CrossRef]

- Wang B, Li B, Deng Q, Dong S. Amperometric glucose biosensor based on sol-gel organic-inorganic hybrid material. Anal Chem. 1998;70(15):3170-3174. [CrossRef]

- Wang GJ, Gao CF, Wei D, Wang C, Ding SQ. Acute pancreatitis: etiology and common pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(12):1427-1430. [CrossRef]

- Wang GJ, Li Y, Zhou ZG, Wang C, Meng WJ. Integrity of the pancreatic duct-acinar system in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2010;9(3):242-247.

- Wang K, Zhao A, Tayier D, et al. Activation of AMPK ameliorates acute severe pancreatitis by suppressing pancreatic acinar cell necroptosis in obese mice models. Cell death Discov. 2023;9(1):363. [CrossRef]

- Wang N, Zhang F, Yang L, et al. Resveratrol protects against L-arginine-induced acute necrotizing pancreatitis in mice by enhancing SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of p53 and heat shock factor 1. Int J Mol Med. 2017;40(2):427-437. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Han M, Bao J, Tu W, Dai Z. A superoxide anion biosensor based on direct electron transfer of superoxide dismutase on sodium alginate sol-gel film and its application to monitoring of living cells. Anal Chim Acta. 2012;717:61-66. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T., Kudo, M., & Strober, W. (2017). Immunopathogenesis of pancreatitis. Mucosal immunology, 10(2), 283-298.

- Wei Y, Zeng Q, Wang M, Huang J, Guo X, Wang L. Near-infrared light-responsive electrochemical protein imprinting biosensor based on a shape memory conducting hydrogel. Biosens Bioelectron. 2019;131:156-162. [CrossRef]

- Woo SM, Noh MH, Kim BG, et al. Comparison of serum procalcitonin with Ranson, APACHE-II, Glasgow and Balthazar CT severity index scores in predicting severity of acute pancreatitis. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2011;58(1):31-37. [CrossRef]

- Woo, S. M., Noh, M. H., Kim, B. G., Hsing, C. T., Han, J. S., Ryu, S. H., Seo, J. M., Yoon, H. A., Jang, J. S., Choi, S. R., & Cho, J. H. (2011). Comparison of serum procalcitonin with Ranson, APACHE-II, Glasgow and Balthazar CT severity index scores in predicting severity of acute pancreatitis. The Korean journal of gastroenterology = Taehan Sohwagi Hakhoe chi, 58(1), 31–37. [CrossRef]

- Wu S, Su F, Dong X, et al. Development of glucose biosensors based on plasma polymerization-assisted nanocomposites of polyaniline, tin oxide, and three-dimensional reduced graphene oxide. Appl Surf Sci. 2017;401:262-270. [CrossRef]

- Wu Y, Midinov B, White RJ. Electrochemical Aptamer-Based Sensor for Real-Time Monitoring of Insulin. ACS sensors. 2019;4(2):498-503. [CrossRef]

- Xu X, Ai F, Huang M. Deceased serum bilirubin and albumin levels in the assessment of severity and mortality in patients with acute pancreatitis. Int J Med Sci. 2020;17(17):2685-2695. [CrossRef]

- Yadav D, Lowenfels AB. The Epidemiology of Pancreatitis and Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(6):1252-1261. [CrossRef]

- Yang AL, McNabb-Baltar J. Hypertriglyceridemia and acute pancreatitis. Pancreatol Off J Int Assoc Pancreatol . [et al]. 2020;20(5):795-800. [CrossRef]

- Yang H, Cao R, Zhou F, et al. The role of Interleukin-22 in severe acute pancreatitis. Mol Med. 2024;30(1):60. [CrossRef]

- Yang M, Jeong JM, Lee KG, Kim DH, Lee SJ, Choi BG. Hierarchical porous microspheres of the Co(3)O(4)@graphene with enhanced electrocatalytic performance for electrochemical biosensors. Biosens Bioelectron. 2017;89(Pt 1):612-619. [CrossRef]

- Yao J, Lv G. Association between red cell distribution width and acute pancreatitis: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2014;4(8):e004721. [CrossRef]

- Yasuda T, Ueda T, Shinzeki M, et al. Increase of high-mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 in blood and injured organs in experimental severe acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2007;34(4):487-488. [CrossRef]

- Yin MJ, Yao M, Gao S, Zhang AP, Tam HY, Wai PKA. Rapid 3D Patterning of Poly(acrylic acid) Ionic Hydrogel for Miniature pH Sensors. Adv Mater. 2016;28(7):1394-1399. [CrossRef]

- Zanini VP, López de Mishima B, Solís V. An amperometric biosensor based on lactate oxidase immobilized in laponite–chitosan hydrogel on a glassy carbon electrode. Application to the analysis of l-lactate in food samples. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2011;155(1):75-80. [CrossRef]

- Zhai D, Liu B, Shi Y, et al. Highly sensitive glucose sensor based on pt nanoparticle/polyaniline hydrogel heterostructures. ACS Nano. 2013;7(4):3540-3546. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., & Sun, S. (2024). Adhesive and conductive hydrogels based on poly (acrylic acid) composites for application as flexible biosensors. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 134575.

- Zhong, Y., Lin, Q., Yu, H., Shao, L., Cui, X., Pang, Q., ... & Hou, R. (2024). Construction methods and biomedical applications of PVA-based hydrogels. Frontiers in Chemistry, 12, 1376799.

- Zhou, Y., Huang, X., Jin, Y., Qiu, M., Ambe, P. C., Basharat, Z., & Hong, W. (2024). The role of mitochondrial damage-associated molecular patterns in acute pancreatitis. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 175, 116690.

- Zhybak M, Beni V, Vagin MY, Dempsey E, Turner APF, Korpan Y. Creatinine and urea biosensors based on a novel ammonium ion-selective copper-polyaniline nano-composite. Biosens Bioelectron. 2016;77:505-511. [CrossRef]

- Zierke, L., John, D., Gischke, M., Tran, Q. T., Sendler, M., Weiss, F. U., ... & Aghdassi, A. A. (2024). Initiation of acute pancreatitis in mice is independent of fusion between lysosomes and zymogen granules. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 81(1), 207.

- Zou R, Li H, Shi J, Sun C, Lu G, Yan X. Dual-enhanced enzyme cascade hybrid hydrogel for the construction of optical biosensor. Biosens Bioelectron. 2024;263:116613. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).