Submitted:

19 December 2024

Posted:

20 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Patients

2.2. Diagnosis of Psoriasis

2.3. Interviewing of Patients

2.4. SNP Selection

2.5. Genetic Analysis

2.6. Statistical and Bioinformatics Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Association Between GSTO1 Gene Polymorphisms and the Risk of Psoriasis

3.2. The Combined Impact of GSTO1 Gene Polymorphisms on Psoriasis Risk

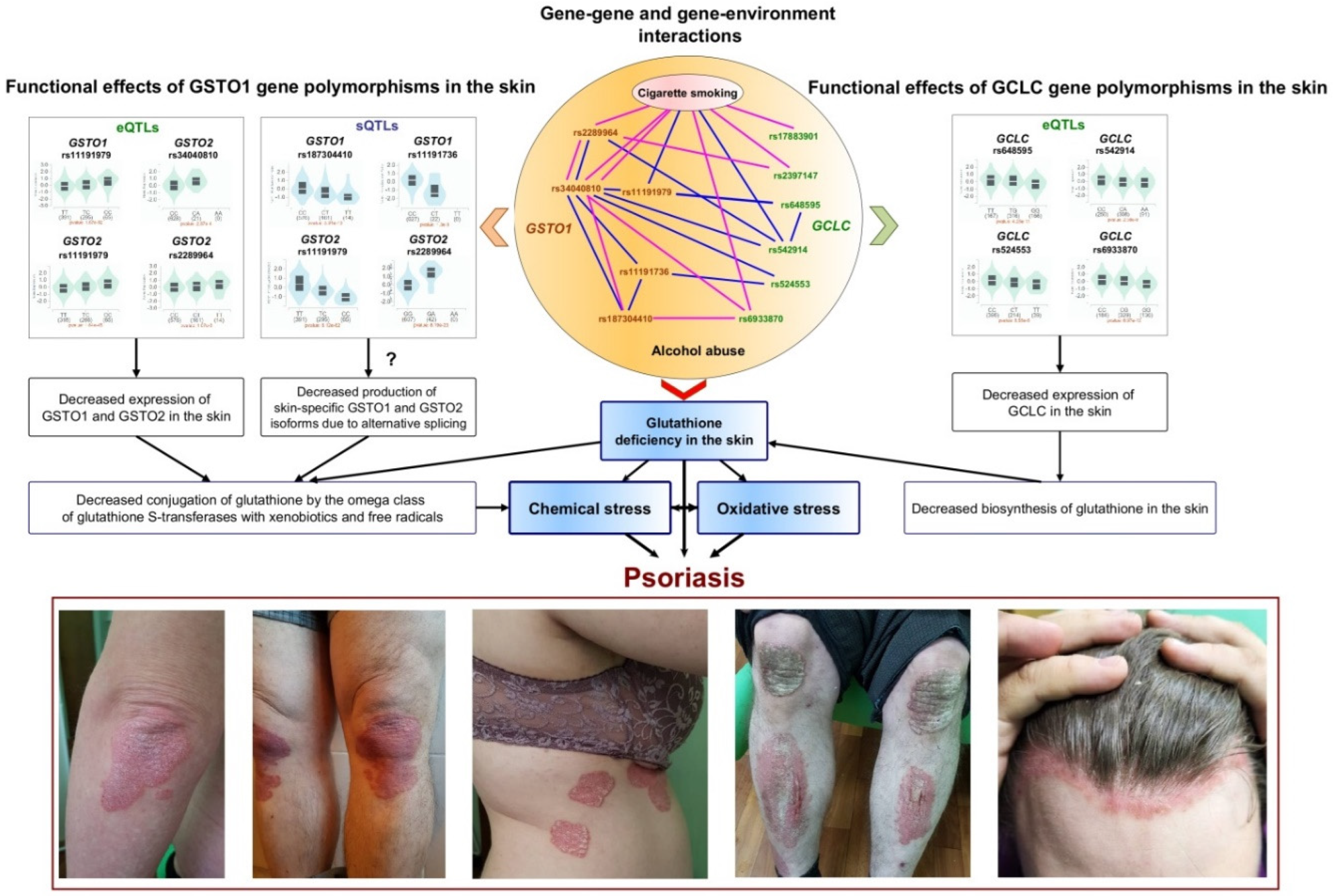

3.3. The Role of Gene-Gene and Gene-Environment Interactions in the Risk of Psoriasis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Campanati A, Marani A, Martina E, Diotallevi F, Radi G, Offidani A. Psoriasis as an Immune-Mediated and Inflammatory Systemic Disease: From Pathophysiology to Novel Therapeutic Approaches. Biomedicines. 2021 Oct 21;9(11):1511. [CrossRef]

- Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, Ashcroft DM; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013 Feb;133(2):377-85. [CrossRef]

- Rendon A, Schäkel K. Psoriasis Pathogenesis and Treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Mar 23;20(6):1475. [CrossRef]

- Capon, F. The Genetic Basis of Psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017 Nov 25;18(12):2526. [CrossRef]

- Yang C, Chen M, Huang H, Li X, Qian D, Hong X, Zheng L, Hong J, Hong J, Zhu Z, Zheng X, Sheng Y, Zhang X. Exome-Wide Rare Loss-of-Function Variant Enrichment Study of 21,347 Han Chinese Individuals Identifies Four Susceptibility Genes for Psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2020 Apr;140(4):799-805.e1. [CrossRef]

- Kamiya K, Kishimoto M, Sugai J, Komine M, Ohtsuki M. Risk Factors for the Development of Psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Sep 5;20(18):4347. [CrossRef]

- Lønnberg AS, Skov L, Skytthe A, Kyvik KO, Pedersen OB, Thomsen SF. Heritability of psoriasis in a large twin sample. Br J Dermatol. 2013 Aug;169(2):412-6. [CrossRef]

- Zeng J, Luo S, Huang Y, Lu Q. Critical role of environmental factors in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. J Dermatol. 2017 Aug;44(8):863-872. [CrossRef]

- Puri P, Nandar SK, Kathuria S, Ramesh V. Effects of air pollution on the skin: A review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017 Jul-Aug;83(4):415-423. [CrossRef]

- Araviiskaia E, Berardesca E, Bieber T, Gontijo G, Sanchez Viera M, Marrot L, Chuberre B, Dreno B. The impact of airborne pollution on skin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Aug;33(8):1496-1505. [CrossRef]

- Wu J, Ma Y, Yang J, Tian Y. Exposure to Air Pollution, Genetic Susceptibility, and Psoriasis Risk in the UK. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Jul 1;7(7):e2421665. [CrossRef]

- Liaw FY, Chen WL, Kao TW, Chang YW, Huang CF. Exploring the link between cadmium and psoriasis in a nationally representative sample. Sci Rep. 2017 May 11;7(1):1723. [CrossRef]

- Wacewicz-Muczyńska M, Socha K, Soroczyńska J, Niczyporuk M, Borawska MH. Cadmium, lead and mercury in the blood of psoriatic and vitiligo patients and their possible associations with dietary habits. Sci Total Environ. 2021 Feb 25;757:143967. [CrossRef]

- Bellinato F, Adami G, Vaienti S, Benini C, Gatti D, Idolazzi L, Fassio A, Rossini M, Girolomoni G, Gisondi P. Association Between Short-term Exposure to Environmental Air Pollution and Psoriasis Flare. JAMA Dermatol. 2022 Apr 1;158(4):375-381. [CrossRef]

- Wu J, Chen H, Yang R, Yu H, Shang S, Hu Y. Short-term exposure to ambient fine particulate matter and psoriasis: A time-series analysis in Beijing, China. Front Public Health. 2022 Oct 13;10:1015197. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Pan Z, Shen J, Wu Y, Fang L, Xu S, Ma Y, Zhao H, Pan F. Associations of exposure to blood and urinary heavy metal mixtures with psoriasis risk among U.S. adults: A cross-sectional study. Sci Total Environ. 2023 Aug 20;887:164133. [CrossRef]

- Götz C, Pfeiffer R, Tigges J, Blatz V, Jäckh C, Freytag EM, Fabian E, Landsiedel R, Merk HF, Krutmann J, Edwards RJ, Pease C, Goebel C, Hewitt N, Fritsche E. Xenobiotic metabolism capacities of human skin in comparison with a 3D epidermis model and keratinocyte-based cell culture as in vitro alternatives for chemical testing: activating enzymes (Phase I). Exp Dermatol. 2012 May;21(5):358-63. [CrossRef]

- van Eijl S, Zhu Z, Cupitt J, Gierula M, Götz C, Fritsche E, Edwards RJ. Elucidation of xenobiotic metabolism pathways in human skin and human skin models by proteomic profiling. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e41721. [CrossRef]

- Hayes JD, Flanagan JU, Jowsey IR. Glutathione transferases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;45:51-88. [CrossRef]

- Ryu J, Park SG, Park BC, Choe M, Lee KS, Cho JW. Proteomic analysis of psoriatic skin tissue for identification of differentially expressed proteins: up-regulation of GSTP1, SFN and PRDX2 in psoriatic skin. Int J Mol Med. 2011 Nov;28(5):785-92. [CrossRef]

- Karadag AS, Uzunçakmak TK, Ozkanli S, Oguztuzun S, Moran B, Akbulak O, Ozlu E, Zemheri IE, Bilgili SG, Akdeniz N. An investigation of cytochrome p450 (CYP) and glutathione S-transferase (GST) isoenzyme protein expression and related interactions with phototherapy in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Int J Dermatol. 2017 Feb;56(2):225-231. [CrossRef]

- Akbulak O, Karadag AS, Akdeniz N, Ozkanli S, Ozlu E, Zemheri E, Oguztuzun S. Evaluation of oxidative stress via protein expression of glutathione S-transferase and cytochrome p450 (CYP450) ısoenzymes in psoriasis vulgaris patients treated with methotrexate. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2018 Jun;37(2):180-185. [CrossRef]

- Reich K, Westphal G, Schulz T, Müller M, Zipprich S, Fuchs T, Hallier E, Neumann C. Combined analysis of polymorphisms of the tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-10 promoter regions and polymorphic xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes in psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 1999 Aug;113(2):214-20. [CrossRef]

- Richter-Hintz D, Their R, Steinwachs S, Kronenberg S, Fritsche E, Sachs B, Wulferink M, Tonn T, Esser C. Allelic variants of drug metabolizing enzymes as risk factors in psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2003 May;120(5):765-70. [CrossRef]

- Gambichler T, Kreuter A, Susok L, Skrygan M, Rotterdam S, Höxtermann S, Müller M, Tigges C, Altmeyer P, Lahner N. Glutathione-S-transferase T1 genotyping and phenotyping in psoriasis patients receiving treatment with oral fumaric acid esters. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014 May;28(5):574-80. [CrossRef]

- Solak B, Karkucak M, Turan H, Ocakoğlu G, Özemri Sağ Ş, Uslu E, Yakut T, Erdem T. Glutathione S-Transferase M1 and T1 Gene Polymorphisms in Patients with Chronic Plaque-Type Psoriasis: A Case-Control Study. Med Princ Pract. 2016;25(2):155-8. [CrossRef]

- Hruska P, Rybecka S, Novak J, Zlamal F, Splichal Z, Slaby O, Vasku V, Bienertova-Vasku J. Combinations of common polymorphisms within GSTA1 and GSTT1 as a risk factor for psoriasis in a central European population: a case-control study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017 Oct;31(10):e461-e463. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava DSL, Jain VK, Verma P, Yadav JP. Polymorphism of glutathione S-transferase M1 and T1 genes and susceptibility to psoriasis disease: A study from North India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018 Jan-Feb;84(1):39-44. [CrossRef]

- Guarneri F, Sapienza D, Papaianni V, Marafioti I, Guarneri C, Mondello C, Roccuzzo S, Asmundo A, Cannavò SP. Association between genetic polymorphisms of glutathione S-transferase M1/T1 and psoriasis in a population from the area of the strict of messina (Southern Italy). Free Radic Res. 2020 Jan;54(1):57-63. [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, Noha Z.a. AbdallahHoda Y.bAbdullahMona E.aAlshaarawyHagar F.a.AtwaMona A.a.Glutathione S-transferase M1 and T1 gene polymorphisms in psoriasis patients: a pilot case-control study. Egyptian Journal of Dermatology and Venereology 43(3):p 200-207, September-December 2023. [CrossRef]

- Dursun HG, Dursun R, Çınar Ayan İ, Zamani AG, Yıldırım MS. Relationship between Glutathione S-transferase gene polymorphisms and clinical features of psoriasis: A case-control study in the Turkish population. Turkderm-Turk Arch Dermatol Venereol. 2024;58:75-82. [CrossRef]

- Klyosova, E.; Azarova, I.; Polonikov, A. A Polymorphism in the Gene Encoding Heat Shock Factor 1 (HSF1) Increases the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: A Pilot Study Supports a Role for Impaired Protein Folding in Disease Pathogenesis. Life 2022a, 12, 1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarenko, V.; Churilin, M.; Azarova, I.; Klyosova, E.; Bykanova, M.; Ob’edkova, N.; Churnosov, M.; Bushueva, O.; Mal, G.; Povetkin, S.; et al. Comprehensive Statistical and Bioinformatics Analysis in the Deciphering of Putative Mechanisms by Which Lipid-Associated GWAS Loci Contribute to Coronary Artery Disease. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobzeva, K.A.; Shilenok, I.V.; Belykh, A.E.; Gurtovoy, D.E.; Bobyleva, L.A.; Krapiva, A.B.; Stetskaya, T.A.; Bykanova, M.A.; Mezhenskaya, A.A.; Lysikova, E.A.; et al. C9orf16 (BBLN) gene, encoding a member of Hero proteins, is a novel marker in ischemic stroke risk. Res. Results Biomed. 2022, 8, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Meglio, P.; Villanova, F.; Nestle, F.O. Psoriasis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2014, 4, a015354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klyosova, E.Y.; Azarova, I.E.; Sunyaykina, O.A.; Polonikov, A.V. Validity of a brief screener for environmental risk factors of age-related diseases using type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease as examples. Res. Results Biomed. 2022b, 8, 130–137. [Google Scholar]

- Garbicz J, Całyniuk B, Górski M, Buczkowska M, Piecuch M, Kulik A, Rozentryt P. Nutritional Therapy in Persons Suffering from Psoriasis. Nutrients. 2021 Dec 28;14(1):119. [CrossRef]

- Mazari AMA, Zhang L, Ye ZW, Zhang J, Tew KD, Townsend DM. The Multifaceted Role of Glutathione S-Transferases in Health and Disease. Biomolecules. 2023 Apr 18;13(4):688. [CrossRef]

- Efanova E, Bushueva O, Saranyuk R, Surovtseva A, Churnosov M, Solodilova M, Polonikov A. Polymorphisms of the GCLC Gene Are Novel Genetic Markers for Susceptibility to Psoriasis Associated with Alcohol Abuse and Cigarette Smoking. Life (Basel). 2023 Jun 2;13(6):1316. [CrossRef]

- Azarova I, Klyosova E, Polonikov A. Association between RAC1 gene variation, redox homeostasis and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Clin Invest. 2022 Aug;52(8):e13792. [CrossRef]

- Stetskaya TA, Kobzeva KA, Zaytsev SM, et al. HSPD1 gene polymorphism is associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke in smokers. Research Results in Biomedicine. 2024;10(2):175-186. [CrossRef]

- Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, Sham PC. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007 Sep;81(3):559-75. [CrossRef]

- Calle ML, Urrea V, Malats N, et al. mbmdr: an R package for exploring gene-gene interactions associated with binary or quantitative traits. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(17):2198-9.

- Polonikov A, Bocharova I, Azarova I, Klyosova E, Bykanova M, Bushueva O, Polonikova A, Churnosov M, Solodilova M. The Impact of Genetic Polymorphisms in Glutamate-Cysteine Ligase, a Key Enzyme of Glutathione Biosynthesis, on Ischemic Stroke Risk and Brain Infarct Size. Life (Basel). 2022 Apr 18;12(4):602. [CrossRef]

- Zhabin S, Lazarenko V, Azarova I, Klyosova E, Bykanova M, Chernousova S, Bashkatov D, Gneeva E, Polonikova A, Churnosov M, Solodilova M, Polonikov A. The Joint Link of the rs1051730 and rs1902341 Polymorphisms and Cigarette Smoking to Peripheral Artery Disease and Atherosclerotic Lesions of Different Arterial Beds. Life (Basel). 2023 Feb 10;13(2):496. [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.D.; Hahn, L.W.; Roodi, N.; Bailey, L.R.; Dupont, W.D.; Parl, F.F.; Moore, J.H. Multifactor-Dimensionality Reduction Reveals High-Order Interactions among Estrogen-Metabolism Genes in Sporadic Breast Cancer. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001, 69, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chattopadhyay A, Lu TP. Gene-gene interaction: the curse of dimensionality. Ann Transl Med. 2019 Dec;7(24):813. [CrossRef]

- Lazarenko V, Churilin M, Azarova I, Klyosova E, Bykanova M, Ob’edkova N, Churnosov M, Bushueva O, Mal G, Povetkin S, Kononov S, Luneva Y, Zhabin S, Polonikova A, Gavrilenko A, Saraev I, Solodilova M, Polonikov A. Comprehensive Statistical and Bioinformatics Analysis in the Deciphering of Putative Mechanisms by Which Lipid-Associated GWAS Loci Contribute to Coronary Artery Disease. Biomedicines. 2022 Jan 25;10(2):259. [CrossRef]

- Sharma R, Yang Y, Sharma A, Awasthi S, Awasthi YC. Antioxidant role of glutathione S-transferases: protection against oxidant toxicity and regulation of stress-mediated apoptosis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2004 Apr;6(2):289-300. [CrossRef]

- Singhal SS, Singh SP, Singhal P, Horne D, Singhal J, Awasthi S. Antioxidant role of glutathione S-transferases: 4-Hydroxynonenal, a key molecule in stress-mediated signaling. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2015 Dec 15;289(3):361-70. [CrossRef]

- Kim Y, Cha SJ, Choi HJ, Kim K. Omega Class Glutathione S-Transferase: Antioxidant Enzyme in Pathogenesis of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:5049532. [CrossRef]

- Board PG, Menon D. Glutathione transferases, regulators of cellular metabolism and physiology. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013 May;1830(5):3267-88. [CrossRef]

- Lanner JT, Georgiou DK, Joshi AD, Hamilton SL. Ryanodine receptors: structure, expression, molecular details, and function in calcium release. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010 Nov;2(11):a003996. [CrossRef]

- Menon D, Coll R, O’Neill LA, Board PG. Glutathione transferase omega 1 is required for the lipopolysaccharide-stimulated induction of NADPH oxidase 1 and the production of reactive oxygen species in macrophages. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014 Aug;73:318-27. [CrossRef]

- Hruska P, Rybecka S, Novak J, Zlamal F, Splichal Z, Slaby O, Vasku V, Bienertova-Vasku J. Combinations of common polymorphisms within GSTA1 and GSTT1 as a risk factor for psoriasis in a central European population: a case-control study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017 Oct;31(10):e461-e463. [CrossRef]

- Dursun HG, Dursun R, Çınar Ayan İ, Zamani AG, Yıldırım MS. Relationship between Glutathione S-transferase gene polymorphisms and clinical features of psoriasis: A case-control study in the Turkish population. Turkderm-Turk Arch Dermatol Venereol. 2024;58:75-82. [CrossRef]

- Wang ZM, Wang DZ, Zhang KY, Huang W, Liu JJ. Systematic evaluation of association between the microsomal glutathione S-transferase 2 common variation and psoriasis vulgaris in Chinese population. Arch Dermatol Res. 2006 Aug;298(3):107-12. [CrossRef]

- Campione E, Mazzilli S, Di Prete M, Dattola A, Cosio T, Lettieri Barbato D, Costanza G, Lanna C, Manfreda V, Gaeta Schumak R, Prignano F, Coniglione F, Ciprani F, Aquilano K, Bianchi L. The Role of Glutathione-S Transferase in Psoriasis and Associated Comorbidities and the Effect of Dimethyl Fumarate in This Pathway. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022 Feb 8;9:760852. [CrossRef]

- Farkas A, Kemény L. Alcohol, liver, systemic inflammation and skin: a focus on patients with psoriasis. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2013;26(3):119-26. [CrossRef]

- Farkas A, Kemény L, Széll M, Dobozy A, Bata-Csörgo Z. Ethanol and acetone stimulate the proliferation of HaCaT keratinocytes: the possible role of alcohol in exacerbating psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2003 Jun;295(2):56-62. [CrossRef]

- Wu D, Cederbaum AI. Alcohol, oxidative stress, and free radical damage. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27(4):277-84.

- Michalak A, Lach T, Cichoż-Lach H. Oxidative Stress-A Key Player in the Course of Alcohol-Related Liver Disease. J Clin Med. 2021 Jul 6;10(14):3011. [CrossRef]

- Lu, SC. Glutathione synthesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013 May;1830(5):3143-53. [CrossRef]

- Vairetti M, Di Pasqua LG, Cagna M, Richelmi P, Ferrigno A, Berardo C. Changes in Glutathione Content in Liver Diseases: An Update. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021 Feb 28;10(3):364. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi K, Ishigaki K, Suzuki A, Tsuchida Y, Tsuchiya H, Sumitomo S, Nagafuchi Y, Miya F, Tsunoda T, Shoda H, Fujio K, Yamamoto K, Kochi Y. Splicing QTL analysis focusing on coding sequences reveals mechanisms for disease susceptibility loci. Nat Commun. 2022 Aug 24;13(1):4659. [CrossRef]

- Lowe ME, Akhtari FS, Potter TA, Fargo DC, Schmitt CP, Schurman SH, Eccles KM, Motsinger-Reif A, Hall JE, Messier KP. The skin is no barrier to mixtures: Air pollutant mixtures and reported psoriasis or eczema in the Personalized Environment and Genes Study (PEGS). J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2023 May;33(3):474-481. [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva M, Mufti A, Maliyar K, Lytvyn Y, Yeung J. Hydroxychloroquine effects on psoriasis: A systematic review and a cautionary note for COVID-19 treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Aug;83(2):579-586. [CrossRef]

- van der Fits L, Mourits S, Voerman JS, Kant M, Boon L, Laman JD, Cornelissen F, Mus AM, Florencia E, Prens EP, Lubberts E. Imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation in mice is mediated via the IL-23/IL-17 axis. J Immunol. 2009 May 1;182(9):5836-45. [CrossRef]

- Jafferany, M. Lithium and psoriasis: what primary care and family physicians should know. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10(6):435-9. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Q, Zhang M, Zhao C. Exposure to Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances and Risk of Psoriasis: A Population-Based Study. Toxics. 2024; 12(11):828. [CrossRef]

- Zakharyan RA, Sampayo-Reyes A, Healy SM, Tsaprailis G, Board PG, Liebler DC, Aposhian HV. Human monomethylarsonic acid (MMA(V)) reductase is a member of the glutathione-S-transferase superfamily. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001 Aug;14(8):1051-7. [CrossRef]

- Schmuck EM, Board PG, Whitbread AK, Tetlow N, Cavanaugh JA, Blackburn AC, Masoumi A. Characterization of the monomethylarsonate reductase and dehydroascorbate reductase activities of Omega class glutathione transferase variants: implications for arsenic metabolism and the age-at-onset of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005 Jul;15(7):493-501. [CrossRef]

- Barnett, J. B. , and K. M. Brundage. “Immunotoxicology of pesticides and chemotherapies.” In Comprehensive Toxicology (Second Edition) Elsevier Science (2010): 467-487.

- Kitahata K, Matsuo K, Hara Y, Naganuma T, Oiso N, Kawada A, Nakayama T. Ascorbic acid derivative DDH-1 ameliorates psoriasis-like skin lesions in mice by suppressing inflammatory cytokine expression. J Pharmacol Sci. 2018 Dec;138(4):284-288. [CrossRef]

- Fares-Medina S, Díaz-Caro I, García-Montes R, Corral-Liria I, García-Gómez-Heras S. Multiple Chemical Sensitivity Syndrome: First Symptoms and Evolution of the Clinical Picture: Case-Control Study/Epidemiological Case-Control Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Nov 29;19(23):15891. [CrossRef]

| SNP ID | Minor allele | N | Permutation P-values (Pperm) estimated for genetic models of SNP-disease associations* | |||

| Allelic | Additive | Dominant | Recessive | |||

| Entire groups | ||||||

| rs11191736 | T | 901 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.19 | NA |

| rs34040810 | A | 944 | 0.45 | 0.29 | 0.39 | NA |

| rs2289964 | T | 941 | 0.86 | 1.00 | 0.78 | 0.86 |

| rs11191979 | C | 930 | 0.59 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.73 |

| rs187304410 | A | 944 | 0.86 | 0.31 | 0.52 | NA |

| Males | ||||||

| rs11191736 | T | 467 | 0.02 | NA | NA | NA |

| rs34040810 | A | 486 | 0.34 | 0.39 | 0.64 | NA |

| rs2289964 | T | 486 | 0.78 | 0.64 | 0.55 | 0.59 |

| rs11191979 | C | 479 | 0.71 | 0.67 | 0.52 | 0.59 |

| rs187304410 | A | 486 | 0.46 | 0.31 | 0.29 | NA |

| Females | ||||||

| rs11191736 | T | 434 | 0.25 | NA | NA | NA |

| rs34040810 | A | 458 | 0.86 | 0.63 | 0.55 | NA |

| rs2289964 | T | 455 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.29 | NA |

| rs11191979 | C | 451 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| rs187304410 | A | 458 | 0.02 | 0.012 | 0.011 | NA |

| SNP | Genotype/ allele |

Healthy Controls1 | Patients with psoriasis1 | OR2 (95% CI) | Pperm3 | ||

| n | % | n | % | ||||

| Entire groups | |||||||

| rs11191736 | C/C | 454 | 99.3 | 438 | 98.6 | 2.07 (0.52-8.34) | 0.19D |

| C/T | 3 | 0.7 | 6 | 1.4 | |||

| T/T | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| T | 3 | 0.3 | 6 | 0.7 | 2.07 (0.52-8.29) | 0.26 | |

| rs34040810 | C/C | 465 | 98.9 | 466 | 98.3 | 1.60 (0.52-4.92) | 0.29A |

| C/A | 5 | 1.1 | 8 | 1.7 | |||

| A/A | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| A | 5 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.8 | 1.59 (0.52-4.88) | 0.45 | |

| rs2289964 | C/C | 360 | 76.6 | 365 | 77.5 | 0.95 (0.70-1.29) | 0.78D |

| C/T | 103 | 21.9 | 99 | 21.0 | |||

| T/T | 7 | 1.5 | 7 | 1.5 | |||

| T | 117 | 12.4 | 113 | 12.0 | 0.96 (0.73-1.26) | 0.86 | |

| rs11191979 | T/T | 236 | 51.3 | 248 | 52.8 | 0.94 (0.73-1.22) | 0.53D |

| T/C | 192 | 41.7 | 183 | 38.9 | |||

| C/C | 32 | 7.0 | 39 | 8.3 | |||

| C | 256 | 27.8 | 261 | 27.8 | 1.00 (0.81-1.22) | 0.59 | |

| rs187304410 | G/G | 451 | 96.0 | 459 | 96.8 | 0.78 (0.39-1.55) | 0.31A |

| G/A | 19 | 4.0 | 15 | 3.2 | |||

| A/A | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| A | 19 | 2.0 | 15 | 1.6 | 0.78 (0.39-1.54) | 0.86 | |

| Males | |||||||

| rs11191736 | C/C | 226 | 100.0 | 235 | 97.5 | NA | NA |

| C/T | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 2.5 | |||

| T/T | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| T | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 1.2 | NA | 0.017 | |

| rs34040810 | C/C | 231 | 98.7 | 245 | 97.2 | 2.20 (0.56-8.6) | 0.39A |

| C/A | 3 | 1.3 | 7 | 2.8 | |||

| A/A | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| A | 3 | 0.6 | 7 | 1.4 | 2.18 (0.56-8.49) | 0.34 | |

| rs2289964 | C/C | 185 | 79.1 | 192 | 76.2 | 1.18 (0.77-1.81) | 0.55D |

| C/T | 42 | 17.9 | 54 | 21.4 | |||

| T/T | 7 | 3.0 | 6 | 2.4 | |||

| T | 56 | 12.0 | 66 | 13.1 | 1.11 (0.76-1.62) | 0.78 | |

| rs11191979 | T/T | 111 | 48.5 | 129 | 51.6 | 0.88 (0.62-1.26) | 0.52D |

| T/C | 100 | 43.7 | 98 | 39.2 | |||

| C/C | 18 | 7.9 | 23 | 9.2 | |||

| C | 136 | 29.7 | 144 | 28.8 | 0.96 (0.72-1.27) | 0.71 | |

| rs187304410 | G/G | 226 | 96.6 | 239 | 94.8 | 1.54 (0.63-3.78) | 0.29D |

| G/A | 8 | 3.4 | 13 | 5.2 | |||

| A/A | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| A | 8 | 1.7 | 13 | 2.6 | 1.52 (0.63-3.71) | 0.46 | |

| Females | |||||||

| rs11191736 | C/C | 228 | 98.7 | 203 | 100.0 | NA | NA |

| C/T | 3 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| T/T | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| T | 3 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | NA | 0.25 | |

| rs34040810 | C/C | 234 | 99.2 | 221 | 99.5 | 0.53 (0.05-5.88) | 0.55D |

| C/A | 2 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.5 | |||

| A/A | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| A | 2 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.53 (0.05-5.87) | 0.86 | |

| rs2289964 | C/C | 175 | 74.2 | 173 | 79.0 | 0.76 (0.49-1.18) | 0.29D |

| C/T | 61 | 25.8 | 45 | 20.5 | |||

| T/T | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.5 | |||

| T | 61 | 12.9 | 47 | 10.7 | 0.81 (0.54-1.21) | 0.33 | |

| rs11191979 | T/T | 125 | 54.1 | 119 | 54.1 | 1.03 (0.77-1.39) | 0.86A |

| T/C | 92 | 39.8 | 85 | 38.6 | |||

| C/C | 14 | 6.1 | 16 | 7.3 | |||

| C | 120 | 26.0 | 117 | 26.6 | 1.03 (0.77-1.39) | 0.86 | |

| rs187304410 | G/G | 225 | 95.3 | 220 | 99.1 | 0.19 (0.04-0.85) | 0.012D |

| G/A | 11 | 4.7 | 2 | 0.9 | |||

| A/A | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| A | 11 | 2.3 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.19 (0.04-0.86) | 0.02 | |

| Haplotypes | SNP | Patients with psoriasis | Healthy Controls | Chi Square | P-value | ||||

| rs11191736 | rs34040810 | rs2289964 | rs11191979 | rs187304410 | |||||

| Entire gropus | |||||||||

| H1 | C | C | C | T | G | 0.671 | 0.672 | 0.005 | 0.999 |

| H2 | C | C | C | C | G | 0.200 | 0.190 | 0.314 | 0.972 |

| H3 | C | C | T | C | G | 0.076 | 0.085 | 0.589 | 0.951 |

| H4 | C | C | T | T | G | 0.032 | 0.030 | 0.070 | 0.993 |

| Rare | - | - | - | - | - | 0.021 | 0.023 | - | - |

| Males | |||||||||

| H1 | C | C | C | T | G | 0.645 | 0.657 | 0.118 | 1.000 |

| H2 | C | C | C | C | G | 0.208 | 0.215 | 0.097 | 1.000 |

| H3 | C | C | T | C | G | 0.076 | 0.084 | 0.089 | 1.000 |

| H4 | C | C | T | T | G | 0.036 | 0.026 | 0.436 | 0.953 |

| Rare | - | - | - | - | - | 0,035 | 0,018 | - | - |

| Females | |||||||||

| H1 | C | C | C | T | G | 0.701 | 0.687 | 0.233 | 1.000 |

| H2 | C | C | C | C | G | 0.187 | 0.165 | 0.733 | 1.000 |

| H3 | C | C | T | C | G | 0.077 | 0.089 | 0.438 | 1.000 |

| H4 | C | C | T | T | G | 0.028 | 0.032 | 0.094 | 1.000 |

| Rare | - | - | - | - | - | 0.007 | 0.027 | - | - |

| Mbmdr-models of SNP × risk factors interactions | Entire groups1 | Males1 | Females1 | |||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Two-order models | N=12 | N=16 | N=13 | |||

| ALCOHOL × GSTO1 (1 SNP) | 5 | 41.7 | 5 | 31.3 | 5 | 38.5 |

| ALCOHOL × GCLC (1 SNP) | 6 | 50.0 | 6 | 37.5 | 6 | 46.2 |

| ALCOHOL × SMOKE | 1 | 8.3 | 1 | 6.3 | 1 | 7.7 |

| GSTO1 (1 SNP) × GCLC (1 SNP) | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 25.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| GSTO1 (1 SNP) × GSTO1 (1 SNP) | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 7.7 |

| Three-order models | N=68 | N=83 | N=28 | |||

| ALCOHOL × GSTO1 (1 SNP) × GSTO1 (1 SNP) | 10 | 14.7 | 10 | 12.0 | 8 | 28.6 |

| ALCOHOL × GCLC (1 SNP) × GSTO1 (1 SNP)* | 30 | 44.1 | 45 | 54.2 | 8 | 28.6 |

| ALCOHOL × GCLC (1 SNP) × GCLC (1 SNP) | 15 | 22.1 | 15 | 18.1 | 1 | 3.6 |

| ALCOHOL × SMOKE × GSTO1 (1 SNP) | 5 | 7.4 | 5 | 6.0 | 5 | 17.9 |

| ALCOHOL × SMOKE × GCLC (1 SNP) | 6 | 8.8 | 6 | 7.2 | 6 | 21.4 |

| Other models | 2 | 2.9 | 2 | 2.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Four-order models | N=239 | N=148 | N=19 | |||

| ALCOHOL × GSTO1 (3 SNPs) | 10 | 4.2 | 9 | 6.1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| ALCOHOL × GSTO1 (2 SNPs) × GCLC (1 SNP)** | 60 | 25.1 | 53 | 35.8 | 0 | 0.0 |

| ALCOHOL × GCLC (2 SNPs) × GSTO1 (1 SNP) | 95 | 39.7 | 6 | 4.1 | 1 | 5.3 |

| ALCOHOL × GCLC (3 SNPs) | 20 | 8.4 | 14 | 9.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| ALCOHOL × SMOKE × GCLC (2 SNPs) | 10 | 4.2 | 12 | 8.1 | 1 | 5.3 |

| ALCOHOL × SMOKE × GCLC (1 SNP) × GSTO1 (1 SNP)** | 30 | 12.6 | 36 | 24.3 | 12 | 63.2 |

| ALCOHOL × SMOKE × GSTO1 (2 SNPs)* | 10 | 4.2 | 10 | 6.8 | 5 | 26.3 |

| Other models | 4 | 1.7 | 8 | 5.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Mbmdr-models of SNP × risk factors interactions | NH | β-H | WH | NL | β-L | WL | Pperm | |

| Two-order models | ||||||||

| 1 | ALCOHOL × GSTO1 rs34040810 | 2 | 0.322 | 34.87 | 1 | -0.322 | 34.87 | <0.0001 |

| 2 | ALCOHOL × GSTO1 rs11191736 | 1 | 0.299 | 26.12 | 1 | -0.313 | 30.68 | <0.0001 |

| 3 | ALCOHOL × GSTO1 rs187304410 | 1 | 0.300 | 27.14 | 1 | -0.292 | 29.57 | <0.0001 |

| 4 | ALCOHOL × GCLC rs648595 | 3 | 0.308 | 29.57 | 1 | -0.259 | 14.33 | <0.0001 |

| 5 | ALCOHOL × GCLC rs542914 | 3 | 0.308 | 29.57 | 2 | -0.183 | 14.68 | <0.0001 |

| Three-order models | ||||||||

| 1 | ALCOHOL × GCLC rs524553 × GSTO1 rs34040810 | 2 | 0.297 | 25.88 | 3 | -0.322 | 34.30 | <0.0001 |

| 2 | ALCOHOL × GCLC rs542914 × GSTO1 rs34040810 | 4 | 0.322 | 34.30 | 2 | -0.203 | 18.31 | <0.0001 |

| 3 | ALCOHOL × GSTO1 rs34040810 × GSTO1 rs11191736 | 1 | 0.299 | 26.12 | 1 | -0.323 | 33.91 | <0.0001 |

| 4 | ALCOHOL × GSTO1 rs11191979 × GSTO1 rs34040810 | 4 | 0.317 | 33.31 | 2 | -0.267 | 27.36 | <0.0001 |

| 5 | ALCOHOL × GSTO1 rs2289964 × GSTO1 rs34040810 | 3 | 0.316 | 32.45 | 1 | -0.172 | 12.53 | <0.0001 |

| Four-order models | ||||||||

| 1 | ALCOHOL × GCLC rs648595 × GCLC rs542914 × GSTO1 rs11191979 | 4 | 0.301 | 16.69 | 6 | -0.303 | 38.90 | <0.0001 |

| 2 | ALCOHOL × GCLC rs524553 × GSTO1 rs34040810 × GSTO1 rs11191736 | 2 | 0.288 | 22.76 | 3 | -0.322 | 33.34 | <0.0001 |

| 3 | ALCOHOL × GCLC rs542914 × GSTO1 rs2289964 × GSTO1 rs34040810 | 5 | 0.313 | 29.13 | 3 | -0.167 | 11.98 | <0.0001 |

| 4 | ALCOHOL × GSTO1 rs187304410 × GSTO1 rs34040810 × GSTO1 rs11191736 | 1 | 0.292 | 23.98 | 1 | -0.292 | 28.65 | <0.0001 |

| 5 | ALCOHOL × SMOKE × GCLC rs542914 × GSTO1 rs11191979 | 5 | 0.291 | 26.44 | 4 | -0.279 | 28.03 | <0.0001 |

| Mbmdr-models of SNP × risk factors interactions | NH | β-H | WH | NL | β-L | WL | Pperm | |

| Two-order models | ||||||||

| 1 | ALCOHOL × SMOKE | 3 | 0.285 | 22.22 | 1 | -0.285 | 22.22 | <0.0001 |

| 2 | ALCOHOL × GSTO1 rs187304410 | 1 | 0.319 | 14.02 | 2 | -0.319 | 14.02 | <0.0001 |

| 3 | ALCOHOL × GSTO1 rs34040810 | 1 | 0.317 | 13.42 | 1 | -0.288 | 11.62 | <0.0001 |

| 4 | ALCOHOL × GSTO1 rs11191736 | 1 | 0.327 | 12.65 | 1 | -0.291 | 10.29 | <0.0001 |

| 5 | ALCOHOL × GSTO1 rs2289964 | 2 | 0.323 | 14.27 | 1 | -0.159 | 6.21 | <0.0001 |

| Three-order models | ||||||||

| 1 | ALCOHOL × SMOKE × GSTO1 rs2289964 | 3 | 0.263 | 15.51 | 2 | -0.289 | 22.82 | <0.0001 |

| 2 | ALCOHOL × SMOKE × GSTO1 rs187304410 | 3 | 0.285 | 22.22 | 2 | -0.285 | 22.22 | <0.0001 |

| 3 | ALCOHOL × SMOKE × GSTO1 rs34040810 | 3 | 0.282 | 21.52 | 1 | -0.270 | 20.04 | <0.0001 |

| 4 | ALCOHOL × SMOKE × GCLC rs17883901 | 3 | 0.261 | 16.24 | 2 | -0.187 | 10.81 | <0.0001 |

| 5 | ALCOHOL × SMOKE × GCLC rs542914 | 3 | 0.320 | 14.56 | 1 | -0.236 | 8.39 | <0.0001 |

| Four-order models | ||||||||

| 1 | ALCOHOL × SMOKE × GCLC rs2397147 × GSTO1 rs2289964 | 2 | 0.292 | 8.24 | 3 | -0.238 | 22.18 | <0.0001 |

| 2 | ALCOHOL × SMOKE × GSTO1 rs187304410 × GSTO1 rs34040810 | 3 | 0.282 | 21.52 | 2 | -0.270 | 20.04 | <0.0001 |

| 3 | ALCOHOL × SMOKE × GCLC rs6933870 × GSTO1 rs187304410 | 4 | 0.342 | 21.24 | 2 | -0.166 | 9.87 | <0.0001 |

| 4 | ALCOHOL × SMOKE × GSTO1 rs2289964 × GSTO1 rs34040810 | 3 | 0.263 | 15.51 | 2 | -0.274 | 20.61 | <0.0001 |

| 5 | ALCOHOL × SMOKE × GCLC rs6933870 × GSTO1 rs34040810 | 4 | 0.340 | 20.56 | 1 | -0.165 | 9.84 | <0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).