1. Introduction

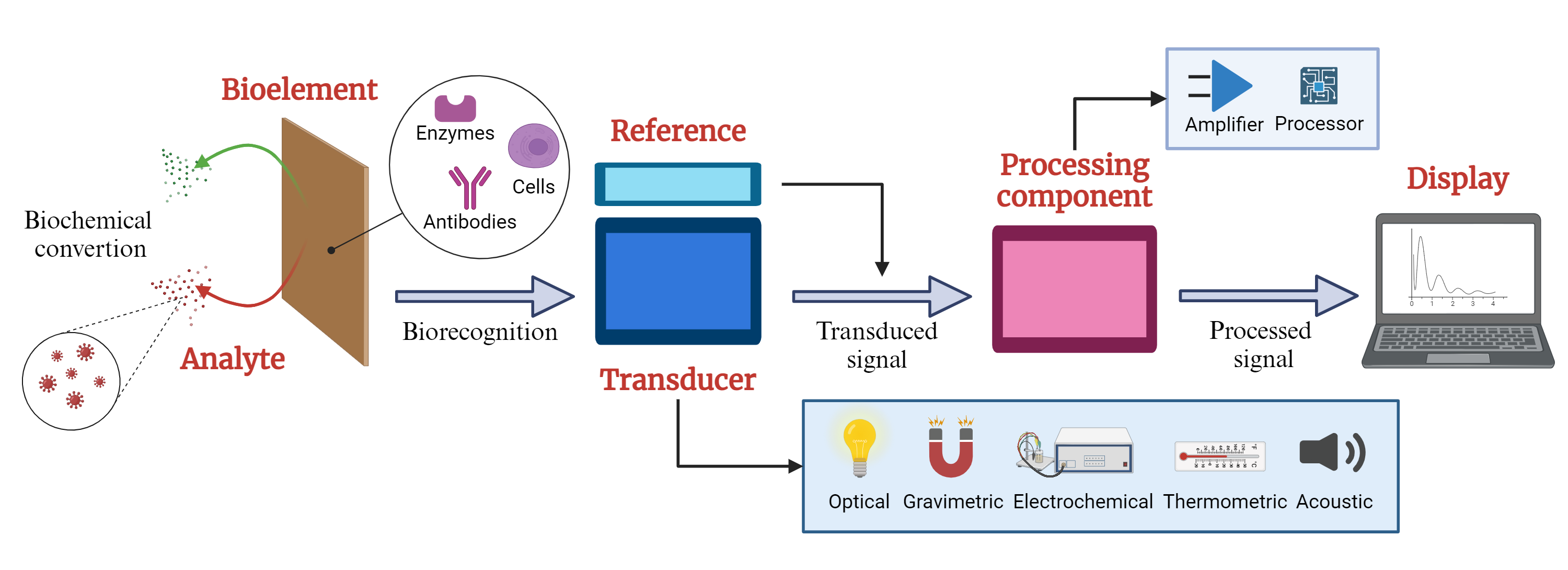

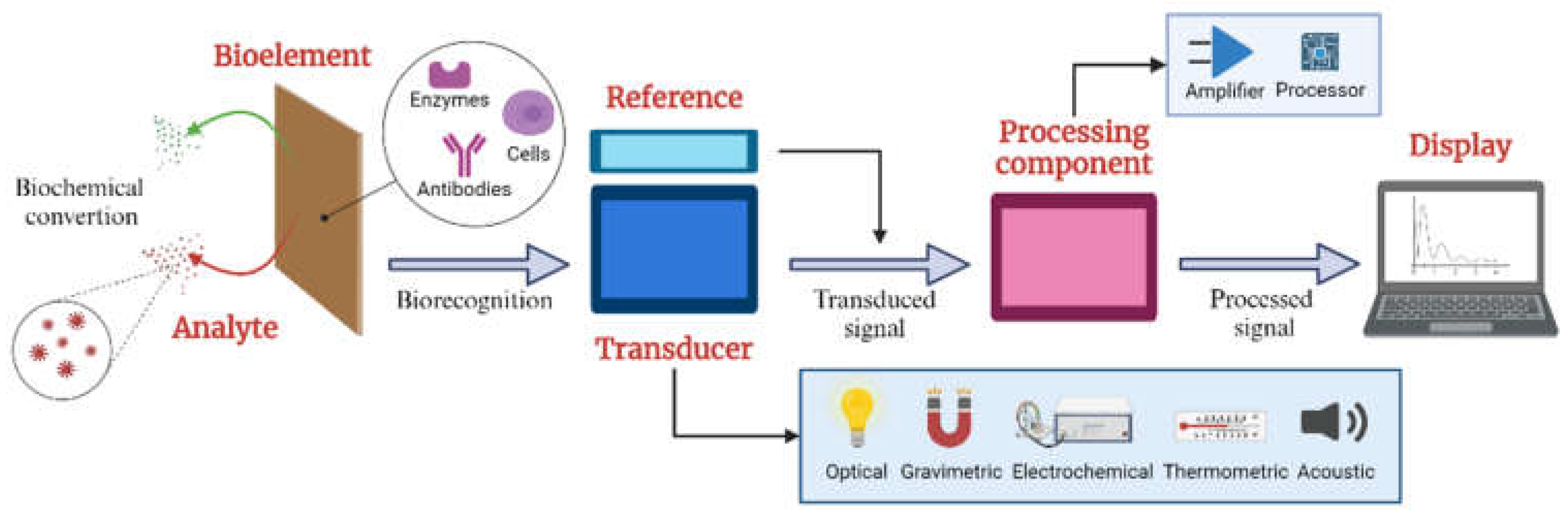

Biosensors are critical tools in analytical science since they combine biological response material with transducers to selectively measure biological or chemical analytes by converting a biological signal into a measurable electrical signal [

1].

Figure 1 shows the elements of a typical biosensor. Their structure comprises three fundamental components: a sensitive bioelement that recognizes the target analyte (microorganisms, cells, antibodies, or enzymes); a signal transducer that detects variations in one or more types of signals, such as impedance, electrical current, power, electromagnetic radiation, and optical density; and a signal processing component providing readable outputs for analysis and interpretation [

2,

3].

The Biosensors are categorized based on the transduction principle and the biological material they utilize, which includes electrochemical, calorimetric, optical, piezo-electric, and resonant biosensors. Specifically, electrochemical biosensors use various techniques such as amperometric, potentiometric, voltammetric, conductometric, and impedimetric methods. These biosensors interact with the recognition elements of the biochemical analytes, generating an electrical signal to transduce the chemical response [

4,

5]. Electrochemical biosensors can be categorized into enzymatic and non-enzymatic sensors. Enzymatic sensors offer excellent selectivity and sensitivity at low concentrations, using enzymes like glucose oxidase, lactate oxidase, or urease as the recognition elements. However, they suffer from a rapid decrease in selectivity over time and are susceptible to external environmental factors.

In contrast, non-enzymatic sensors, employing materials like conductive polymers, nanomaterials, or organic molecules instead of enzymes, have been developed to address the limitations of enzymatic biosensors. They provide long-term stability, high electron transfer rates, and high electrocatalytic activity. Nonetheless, their selectivity remains lower than that of enzymatic sensors [

6,

7,

8].

Optical biosensors have become an increasingly popular choice for disease detection and prevention in recent decades due to their rapid response and user-friendly nature. These biosensors can be classified as either label-free or label-based [

9]. Label-free optical biosensors operate without labels such as fluorescence or radio labels, offering benefits like real-time detection and avoidance of false signals caused by labeling. In contrast, label-based optical biosensors depend on labels like fluorescent dyes or nanoparticles to measure biomolecular binding events, which can sometimes interfere with the binding process and reduce efficiency [

10,

11]. This advancement in optical biosensors points toward a promising direction in the evolution of biosensors, particularly in cancer diagnosis and treatment, aiming to minimize unnecessary biopsies and enhance diagnostic accuracy [

12,

13,

14]. These biosensors are being studied for the detection and treatment of skin cancers such as melanoma and non-melanoma types, and their potential application may extend to other forms of cancer, such as breast, lung, and prostate cancer, in the future [

15]. Optical biosensors are designed based on optical phenomena, including fluorescence, chemiluminescence, and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) [

16,

17].

Nano biosensors are biosensors based on nanostructured materials that are promising tools for improving the detection of a specific analyte. Carbon dots (CDs) and glassy carbon (GC) are the most widely used nanomaterials in developing optical and electrochemical biosensors [

18,

19]. CDs are carbon nanoparticles with a quasi-spherical shape composed of crystalline or amorphous carbon. They primarily consist of graphene and graphene oxide sheets, whether in the form of sp

2-graphitic carbon or from the introduction of sp

3-hybridized carbon. They have been particularly attractive due to their nanoscale size, morphology, high colloidal stability, broad absorption in the UV-visible light spectrum, photoluminescent properties, low toxicity, and simplicity in their manufacturing processes [

20,

21,

22]. GC is a form of disordered sp

2 carbon, characterized by unique material properties such as high strength, a low density of approximately 1.5 g/cm³, the capability to withstand high temperatures in inert gas up to 3000 °C, and its exceptional extreme corrosion resistance [

23,

24]. These characteristics make carbon-based nanomaterials (CDs and GC) attractive for the fabrication of portable, biocompatible, and efficient nano biosensors with potential applications in fields such as cancer detection and treatment, officering improved specificity, affordability, and sensitivity compared to traditional cancer detection methodologies [

25,

26,

27].

2. Development of Biosensors

Integrating nanotechnology with biosensors enables rapid and accurate detection of molecular biomarkers in different samples. Nanomaterials contribute to reducing detection limits to individual molecules and improving sensor performance by increasing the number of bioreceptor units immobilized. Gold nanoparticles, quantum dots, carbon nanotubes, graphene, and other nanostructured materials are extensively researched for their effectiveness in biosensing applications due to their enhanced performance and specific properties [

28]. The synthesis of nanomaterials involves two methods classified as ‘bottom-up’ and ‘top-down’ approaches. In the ‘top-down’ approach, bulk materials are mechanically processed and converted into fine particles on the nanoscale size regime. Some techniques used are mechanical machining, physical vapor deposition (PVD), lithography, electrochemical method, and pyrolysis through thermal evaporation pyrolysis [

29,

30]. This method has the advantages of large-scale production, the possibility of deposition over a large substrate, and the fact that it does not require chemical purification. However, it also comes with disadvantages such as broad size distribution, varied particle shape, difficulty in controlling deposition parameters, and usually involves expensive equipment [

31].

In contrast, the fine particles are assembled using a bottom-up approach to construct nanomaterials. The ‘bottom-up’ approach involves the sol-gel method, chemical vapor deposition (CVD), chemical co-precipitation, micro-emulsions, hydrothermal, and microwave methods [

29,

30]. This method can produce ultra-fine nanoparticles, allows for control over deposition parameters, and is generally cheaper. However, it is challenging for large-scale production and requires chemical purification [

31]. The choice between these methods depends on the material and the specific applications. Applications of these methods vary widely; top-down approaches are used in areas like electronics and structural materials, while bottom-up methods are frequently employed in biomedical fields due to their ability to produce high-purity and well-defined nanomaterials [

32,

33].

2.1. Synthesis of Carbon Dots

Synthetic procedures for CDs are diverse and tailored to achieve specific characteristics and functionalities. Pyrolysis, a common technique, involves carbonizing organic precursors to yield nanoscale carbon structures with quantum confinement effects. Notably, the pyrolysis of citric acid is a prevalent approach. This method entails meticulously preparing a mixture comprising L-histidine, citric acid, and ultrapure water, which undergoes ultrasonic dissolution to ensure homogeneity. Subsequently, the solution is transferred to a Teflon-lined autoclave and heated to 180°C for 4 hours, facilitating carbonization. Centrifugation is employed to separate larger particles, followed by a dialysis procedure [

34].

Another notable method is hydrothermal synthesis, which employs elevated temperature and pressure conditions within an aqueous solution to facilitate the generation of CDs from various carbon precursor molecules [

35], such as plant-derived carbon precursors, specifically

Ferulago angulata. This technique entails the carbonization of

Ferulago angulata at different temperatures, followed by dispersion in deionized water to achieve a homogeneous solution [

36]. Furthermore, CDs have been successfully synthesized from tomato juice via hydrothermal treatment, resulting in particles ranging in size from 1.3 to 3.7 nm. These tomato-derived CDs have shown utility in detecting carcinoembryonic antigens [

37].

Microwave-assisted synthesis is a rapid and efficient technique that allows for uniform heating and precise control, significantly reducing reaction time [

33]. CDs were synthesized using this technique from banana peels to manufacture a biosensor for detecting colitoxin DNA in human serum [

38]. The microwave-assisted technique's rapid and efficient synthesis of carbon dots doped with sulfur and nitrogen, completed within 3 minutes of reaction time, demonstrates a significant advancement in materials chemistry. These dots exhibit high dispersity in water and a quantum yield of fluorescence of 75.6 ± 2.1%, along with notable antimicrobial and antioxidant properties, providing an efficient and sustainable alternative to traditional methods [

39].

The electrochemical method is another viable technique for synthesizing CDs. This method involves applying a specific voltage or current to a working electrode, typically a carbon material with conductive properties, to induce an oxidation reaction at the anode. This process results in the delamination of carbon nanoparticles from the carbon source, which is then obtained as carbon dots after centrifugation [

33]. An example of the electrochemical method's versatility is the synthesis of nitrogen and sulfur co-doped carbon dots (N, S/CDs) through electrolysis. Electrolyzing graphite rods in a specific solution can form N, S/Graphene Dots, demonstrating the diversity of available synthesis methods [

40].

2.2. Synthesis of Glassy Carbon

Despite the continued dominance of pyrolyzing phenol/formaldehyde (PFA) resins as the preferred method for producing glassy carbon (GC), numerous modifications to this traditional chemical protocol have been developed. The synthesis process typically involves pyrolysis of organic polymers like phenolic and poly (furfuryl alcohol) resins, followed by sulfuric acid etching, resulting in a material with remarkable properties [

41,

42]. One of these notable modifications is synthesizing the modified glassy carbon electrode (GCE), which starts with preparing a g-C3N4 suspension by ultrasonically dispersing 1 mg of g-C3N4 in 4 mL of deionized water. A 2.0 μL drop of this suspension is applied to a clean GCE and dried under an infrared lamp. Subsequently, l-cysteine is electropolymerized onto the g-C3N4/GCE surface using cyclic voltammetry (CV) for 240 seconds at a scan rate of 5 mV/s. This modified approach enhances the electrochemical properties of GC, making it practical for detecting methotrexate in pharmaceutical and biological samples [

43].

2.3. Fabrication Methods of Electrodes

2.3.1. Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPE)

SPE devices have stood out in recent decades thanks to their portability, low manufacturing cost, ease of use, and the possibility of being manufactured from different substances with flexible selectivity. Thanks to their versatility and high reproducibility, SPEs are attractive and ideal for use in various applications such as medicine, pharmacy, environment, etc [

44,

45]. Cancer detection is one of the most promising areas for applying SPE [

46]. These electrodes can be used in the diagnosis of various cancer-related pathologies, such as pancreatic cancer, melanomas, leukemia, breast cancer, glioma cells, cervical cancer, and ovarian cancer, to name but a few [

47,

48,

49]. The ability of SPE to detect specific markers in biological samples makes them valuable tools for the early detection and monitoring of disease progression.

The manufacturing process of an SPE begins with the design of a mesh, which delineates the size and geometry of the electrode, as well as the selection of conductive inks and suitable substances for the substrate. The most common inks for working electrodes (WE) are carbon-based. Silver or silver chloride inks are employed for the reference electrode (RE), whereas the counter electrode (CE) typically utilizes the same ink as the WE. Subsequently, thin films are fabricated through a layer-by-layer deposition technique, applying the chosen inks onto the substrate. This approach ensures the creation of a uniform and functional layer. After applying layers, the electrodes are subjected to drying using hot air and IR radiation. A curing process is also carried out to solidify the ink, thereby enhancing the durability and stability of the electrode [

45].

In the final step, the electrical circuits are coated with an insulating material. A sample is added to the surface of the SPE to conduct analytical evaluations, thus completing the manufacturing and preparation process of the electrode for use in various applications [

45].

Screen-Printed Electrode Configurations

There are two configurations of screen-printed electrodes:

- -

Screen-printed modules with three electrodes, which consist of a working electrode at which the electrochemical reaction of interest occurs, an auxiliary electrode (counter electrode) that completes the electrical circuit and is usually made from an inert material that does not participate in the electrochemical reaction under study and a reference electrode that provides a stable potential against which it measures the potential of the working electrode [

50].

- -

Screen-printed modules with four electrodes, including a working electrode, a working sensor electrode, an auxiliary electrode, and a reference electrode. The four-electrode configuration is usually employed to measure the effect of an applied current on a solution or some barrier within that solution. The selection of the configuration depends on the specific application; however, the three-electrode configuration is the most used for fabricating biosensors to detect cancer [

50].

It is important to note that these electrodes are available in various materials depending on the application's needs, such as glassy carbon, gold, platinum, or silver. In this review, the focus is on the working electrode material, specifically glassy carbon.

Glassy Carbon Electrodes (GCE) as Working Electrode

As mentioned above, for applications such as cell detection or cancer biomarkers, the most used material for detection or working electrodes is glassy carbon [

49,

51,

52]. These types of electrodes are made from highly purified carbon and subjected to rigorous heat treatment to generate a dense, non-graphitic structure, which gives GCE its outstanding stability and durability. However, to improve their analytical properties, such as sensitivity and selectivity, and increase stability, there has been a growing interest in developing these electrodes modified with nanomaterials, especially carbon-based ones, such as graphene or carbon quantum dots [

53,

54]. The ability of these nanomaterials to deliver enhances electrocatalytic activities and reduces deposition on the electrode surface, making them beneficial for biosensor development [

50].

Modifying the working electrode with different nanomaterials can involve a few advanced techniques, the most used being electrochemical deposition and drop casting [

55,

56]. These strategies allow for optimizing the electrode properties and improving its detection capacity, thus contributing to developing more sensitive and selective biosensors for the early and accurate identification of cancer biomarkers.

It is essential to highlight that this modification represents just one step in modifying an electrode's surface. Before modification, thorough preparation of the electrode surface is necessary. Typically, this involves three essential steps: polishing, cleaning, and drying, using specific materials to remove contaminants, and ensuring accurate and reproducible electrochemical measurements. A few methods are commonly used for surface polishing and cleaning. Polishing can be achieved with AL203 or alumina slurry powder. Both ethanol and deionized water are practical options for cleaning, and electrochemical cleaning is a well–established technique [

34,

57,

58,

59].

2.3.2. Electrochemical Deposition

Electrochemical deposition, or electrodeposition or electroplating, is a method for depositing conducting or semiconducting materials onto a substrate. This process relies on the application of an electric field and redox reactions. By passing an electrical current through an electrolyte solution containing cations of the desired material, these positively charged ions are reduced at the surface of the electrode (cathode), forming a thin film or coating of the target material on the substrate [

60].

Electrodeposition is a widely recognized conventional technique employed to enhance diverse materials' aesthetic appeal and functionality by modifying their surface characteristics. However, its significance extends further as it is increasingly acknowledged as a versatile method for crafting nanomaterials. In sensor development, electrodeposition plays a pivotal role in adapting the surface properties of electrodes. This precision in surface modification is crucial for enhanced electrode conductivity, facilitating electron transfer, and improving biosensors’ analytical sensitivity, selectivity, and stability [

61,

62].

Electrochemical deposition is a pivotal technique in the surface modification of working electrodes for biosensor applications. A novel electrochemical cytosensor was designed for the sensitive detection and quantification of KG1a cells as a model of LSCs. To achieve this objective, the GCE underwent modification by incorporating graphene dots (GDs), which was aimed at improving its electrical conductivity, particularly by augmenting the specific surface area of the modified electrode. This was accomplished by electrochemically depositing synthesized GDs onto the pre-cleaned GCE using the cyclic voltammetry (CV) technique [

64]

. The summary of studies on electrochemical deposition is shown in

Table 1.

2.3.3. Drop Casting

The drop casting technique is a simple, easy, and fast procedure that directly incorporates nanomaterials into the electrode. This technique is mainly used to prepare the surface of vitreous and silk-screened carbon electrodes [

65]

. In this method, a drop of liquid containing a suspension of the particles of the nanomaterial of interest is deposited directly on the surface of the electrode to be modified with the help of a suitable solvent, ideally limiting its distribution exclusively to the working electrode without spilling onto the surrounding insulating material [

66].

A 2019 study, “A Novel Carbon Quantum Dots Signal Amplification Strategy Coupled with Sandwich Electrochemiluminescence Immunosensor for the Detection of CA15-3 in Human Serum” was conducted. In this study,

the electrode modification process primarily utilized the drop-cast technique. 6 μL of primary anti-CA15-3 (Ab1) solution (50 μg mL-1) was initially deposited onto the PDA-AgNPs/GCE electrode. This deposition occurred at 4 °C over 12 hours, forming Ab1/PDA-AgNPs/GCE. Subsequently, to eliminate physically adsorbed Ab1, the electrode was rinsed with PBS. Next, 4 μL of bovine serum albumin solution (0.5 wt%) was drop-cast onto the modified electrode and incubated at 37 °C for 40 minutes. This step effectively blocked nonspecific coupling sites, yielding BSA/Ab1/PDA-AgNPs/GCE. The drop-cast technique facilitated precise control over the deposition of each layer, ensuring efficient modification of the electrode surface [

34].

In a 2021 study titled "Application of sulfur-doped graphene quantum dots@gold-carbon nanosphere for electrical pulse-induced impedimetric detection of glioma cells," the biosensing electrode was crafted through drop-casting the nanocomposite onto the GCE. Specifically, the SGQDs@Au–CNS NPs solution was deposited onto the polished GCE electrode to form the sensing probe. This process yielded the GCE||Au–CNS@S-GQD/Ang-2 configuration [

67].

In another 2022 study titled “Electrochemically Exfoliated Graphene Quantum Dots Based Biosensor for CD44 Breast Cancer”. The drop-cast technique was employed to prepare the biosensing electrode. Initially, 5 μL of GQDs solution was drop-cast onto the GCE surface and allowed to dry at ambient temperature for 24 hours. Subsequently, a freshly prepared solution of 4:1 EDC: NHS in 10 mM PBS (pH 7.0) was drop-cast onto the GQDs-modified electrodes to activate the functional groups. After one hour, the electrodes were rinsed with Milli-Q water. Next, 5 μL of 20 μg/mL CD44 antibodies (in 10 mM PBS pH 7.0) were immobilized to allow the antibodies to bind with the activated electrode surface. The final surface-modified GCE, i.e., BSA/CD44 antibody/GQDs/GCE, was used as the electrochemical probe to detect the CD44 antigen [

68]

.

In a recent 2023 study titled "A novel bimetallic MXene derivative QD-based ECL sensor for miRNA-27a-3p detection”. Initially, SnS2 nanosheets were applied onto a GCE, followed by the deposition of DSPE-PEG2000-NH2 solution onto the same electrode, which was then subjected to incubation. Subsequently, DOPC solution was added and incubated, resulting in the formation of a fluid layer. Next, 4 μL of capture DNA (H1) modified with cholesterol was incubated on the surface of the lipid bilayer at room temperature. During the sensing process, different concentrations of target miRNA-27a-3p were introduced and incubated at room temperature. Finally, Mo2TiC2 QDs-labeled H2 was introduced into the sensing system at room temperature and allowed to incubate. After removing any unconnected miRNA and Mo2TiC2 QDs, an ECL test was conducted in phosphate-buffered saline containing potassium persulfate (K2S2O8) [

69]. The summary of the information about these studies and other relevant ones is found in

Table 1.

2.3.4. Electrodeposition and Drop Cast

Researchers have used electrodeposition and drop-casting techniques in recent studies to modify Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) surfaces for various electrochemical applications. These techniques offer distinct advantages and enhanced functionalities and, when combined, improve the performance of the modified electrodes.

In a 2020 study titled “Anodic Electrochemiluminescence of Carbon Dots Promoted by Nitrogen Doping and Application to Rapid Cancer Cell Detection” a mixture solution containing nitrogen-doped carbon dots (NHCDs) and chitosan (CS) was drop cast onto a well-polished GCE surface. After drying, gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) were electrodeposited onto the NHCDs/CS film [

40].

Another 2022 study, “Early-stage evaluation of colon cancer using tungsten disulfide quantum dots and bacteriophage nanocomposite as an efficient electrochemical platform,” involved the sequential modification of the GCE surface by drop casting WS2 quantum dots (QDs) followed by electrodeposition of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) using the cyclic voltammetry (CV) technique [

71].

2.4. Transducer Principles

2.4.1. Electrochemical Principles of Transduction

Potentiometric Biosensors

Potentiometric biosensors generate a potential difference between the working electrode and the reference electrode to detect chemical reactions of electroactive materials under a constant current. This technique does not deplete the measured species compared to amperometric biosensors. The value of potentiometric biosensors lies in their sensitivity and selectivity, particularly when coupled with a reliable reference electrode, which contributes to their significance in various applications. Moreover, their manufacturing simplicity and performance maintenance, even with significant size reduction, further enhance their appeal [

30,

73]. Despite their structural similarities, a potentiometric biosensor was implemented using an aptamer-based nano filter interface to distinguish between l-3,4 dihydroxyphenylalanine (l-DOPA) and dopamine (DA). A DA–Ap nano_filter-coated Gold (Au) gate field-effect transistor (FET) was employed, with an Au gate electrode assessing the electrical response to l-DOPA based on oxidative reactions. The nano_filter interface, formed by immobilizing the DA–Ap layer on an aryl-diazonium-based anchor monolayer, allowed for clear discrimination between the electrical signals of l-DOPA and DA [

74].

Amperometric Biosensors

Amperometric biosensors stand out for their ability to generate current via oxidation reactions, making a device capable of providing precise quantitative analytical data. While these biosensors often compete with potentiometric biosensors in response time, energy range, and sensitivity, they may face challenges regarding selectivity and susceptibility to interference from other electroactive substances. These biosensors operate in either two-electrode or three-electrode configurations. They measure the current produced by electrochemical oxidation or reduction of electroactive species at the working electrode. This occurs when a constant potential is applied with respect to the reference electrode. When a potential is applied during operation, the resulting current (typically from nanoamps to milliamps) reflects the catalytic conversion or protein adsorption occurring at the electrode surface in the amperometric biosensor setup. [

30,

73]. An amperometric biosensor for l-fucose detection was developed to address the challenges of electroactive interferences in urinalysis, such as ascorbic acid, dopamine, and uric acid. By utilizing the direct electron transfer type bioelectrocatalysis of pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ)-dependent pyranose dehydrogenase from Coprinopsis cinerea (CcPDH), the biosensor achieved a catalytic current at a lower potential than the interfering compounds, allowing for the selective detection of l-fucose [

75].

Conductometric Biosensors

Conductometric biosensors serve as pivotal tools for quantifying alterations in conductance between electrodes, reflecting changes in the conductivity properties of the analyte due to electrochemical reactions. These biosensors find extensive application in monitoring metabolic processes within living biological systems, facilitating real-time assessment of biochemical changes based on conductivity variations. Their utility lies in providing valuable insights into dynamic metabolic activities, enabling a deeper understanding of biological processes at a molecular level. One of the key applications of conductometric biosensors is quantifying the change in the electrical conductivity of cell solutions. Electrochemical reactions within the solution produce electrons or ions, altering the solution's conductivity. Although the sensitivity of conductance measurement is relatively low, applying a sinusoidal electric field can mitigate undesirable effects such as Faradaic processes, concentration polarization, and double-layer charging [

30,

76].

Impedimetric Biosensors

Impedimetric biosensors detect alterations in electrical impedance at the electrode/electrolyte interface upon applying a small sinusoidal excitation signal. This method involves applying a low-amplitude AC voltage to the sensor electrode and measuring in-phase and out-of-phase current responses across different frequencies facilitated by an impedance analyzer. Such an approach enables sensor performance evaluation across a range of frequencies, offering valuable insights into analyte activity and facilitating precise measurements and monitoring. These label-free techniques are beneficial for quantifying biomolecular interactions, including enzymatic reactions, DNA hybridization, various antigen-antibody, and protein-protein interactions. When a target biomolecule interacts with a specific bioreceptor on the sensor surface, changes in dielectric constant or resistance occur exclusively due to the presence of the target molecules. Consequently, impedance sensing eliminates the need for labels, making it advantageous for protein detection and constructing third-generation biosensors [

30,

73]. A novel four-electrode-based impedimetric biosensors were developed to assess tamoxifen's cytotoxicity on cervical cancer cell lines, particularly HeLa cells. By employing the electric cell-substrate impedance sensing (ECIS) method, the biosensors measured cell impedance across a frequency range of 100 Hz to 1 MHz. The results indicated a significant reduction in the number of HeLa cells on the electrode surfaces in a dose-dependent manner upon exposure to tamoxifen [

77].

Electro-bioimpedance is a non-invasive detection method that measures the electrical impedance of biological tissue, similar to microfluidic cell detection. It is widely used for medical purposes, complementing physicochemical and biochemical techniques. The electrical impedance (Z) is expressed as a complex relationship between the voltage response (Vo) and the current excitation (Io) flowing through the material, where ω is the angular frequency, and ϴ is the signal phase. The complex number Z is represented by the real part of the impedance (RZ), the resistance, and the imaginary part (XZ), the reactance. In a biological system, the parameter RZ can be associated with the degree of hydration. The parameter XZ is associated with the capacitive behavior of cells and can be compared to the number of cells present and the reactance value, and ϴ is considered a parameter that describes tissue behavior and, according to some authors, the diagnosis of clinical parameters [

78].

Voltammetric Biosensors

Voltammetry, an electro-analytical method, quantifies current changes consequent to voltage fluctuations. Various techniques, including Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV), Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV), and Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV), among others, find application within this domain. The inherent advantages of voltammetric methods, such as their cost-effectiveness, remarkable selectivity, and heightened sensitivity, render them prevalent in biosensing systems [

73]. An example of this is using the voltammetric principle to investigate the binding of pazopanib with dsDNA using bare and modified glassy carbon electrodes (GCE). The interaction was primarily evaluated based on the decrease of the voltammetric signal of deoxyadenosine by differential pulse voltammetry. The study employed three methods for this evaluation: incubated solutions, a dsDNA biosensor, and a nanosensor. The nanosensor was fabricated using SnO2 nanoparticles and a carbon hybrid material derived from waste masks, the most used personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results indicated that pazopanib (PZB) was active in the minor groove region of DNA [

79].

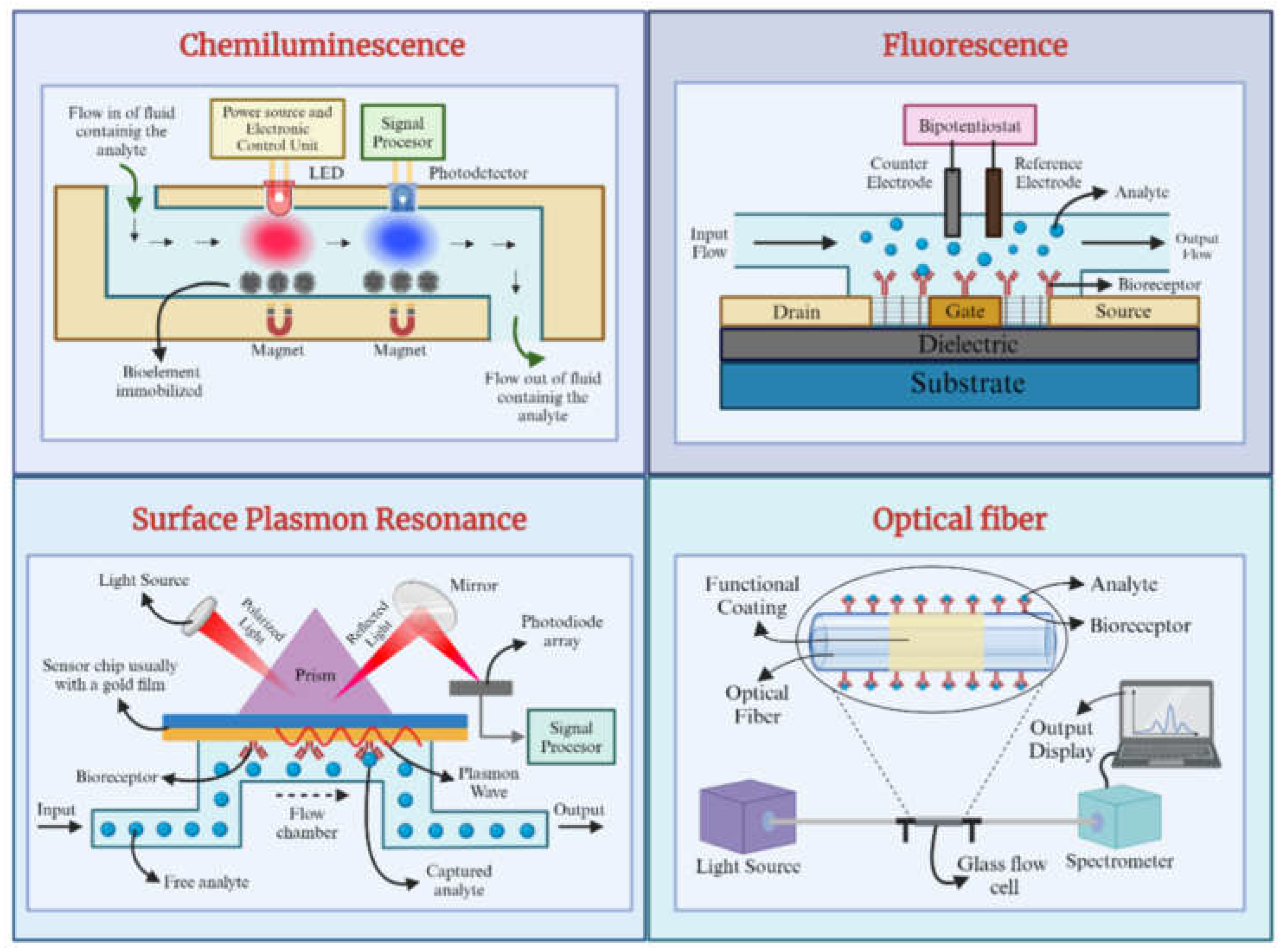

2.4.2. Optical Principles of Transduction

Fluorescence-Based Optical Biosensors

Fluorescence, an optical phenomenon utilized for analyte or molecule detection, has become a focal point in developing fluorescence-based optical biosensors. These biosensors, renowned for their exceptional selectivity, sensitivity, and rapid response time, are extensively explored in medical diagnosis, environmental monitoring, and food quality assessment. They employ various fluorescent materials, such as quantum dots, organic dyes, and fluorescent proteins, enabling detection across a wide range of analytes [

30]. Three primary approaches characterize fluorescence-based biosensors: fluorescent quenching (turn-off), fluorescent enhancement (turn-on), and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET). These latter have gained prominence for their heightened sensitivity, particularly in studying intracellular processes. FRET involves nonradiative energy transfer from an excited donor molecule (D) to an acceptor molecule (A) at the ground state, facilitated by long-range multipole interactions. Due to their ability to detect minute changes ranging from angstroms to nanometers, FRET-based sensors find critical applications in cancer therapy and aptamer analysis. Fluorescence typically arises from the emission of light or radiation upon external exposure to an object absorbing light or radiation. A fluorescence detection system comprises four essential components: an excitation light source, a fluorophore, wavelength filters isolating emission photons from excitation photons, and a detector [

73,

80,

81]. A novel switch-conversational radiometric fluorescence biosensor (SCRF biosensor) for highly sensitive miRNA detection was designed. This biosensor employed a structure-convertible DNA switch, a single-strand DNA with a stem-loop structure modified with two fluorophores (Cy3 and Cy5), and a quencher at specific sites. The detection process involved the production of amplicon fragments (c*) through an exponential amplification reaction. When these c* fragments hybridized to the loop of the DNA switch, the switch's structure converted, leading to fluorescence resonance energy transfer between Cy5 and Cy3. This transfer resulted in the observation of two fluorescence signals with different trends. By analyzing the ratio of these two signals, the target miRNA could be quantitatively and rapidly detected within a concentration range from 100 fM to 100 nM, with an impressive detection limit down to 70.9 fM [

82].

Chemiluminescence-Based Optical Biosensors

Chemiluminescence, the phenomenon wherein light energy is emitted from a chemical reaction, has garnered significant interest due to its simplicity, low detection limit, wide calibration range, and cost-effective instrumentation. Chemiluminescence-based biosensors have emerged as valuable tools in various fields. Recent advancements in chemiluminescence studies involve the integration of nanomaterials to enhance intrinsic sensitivity and explore novel detection applications. Chemiluminescence shares similarities with fluorescence, yet a crucial distinction lies in its initiation mechanism. While fluorescence relies on exciting molecules with external light, chemiluminescence triggers biomolecule excitation through chemical reactions, typically involving oxidizing substances like O

2 or H

2O

2. Notably, chemiluminescence does not necessitate an external light source to initiate the reaction [

30,

73,

80,

83]. The enzyme-free chemiluminescence immunoassay with ODI-CL detection has been developed for the early diagnosis of thyroid cancer. This method involves a sandwich immunoassay using fluorescent microsphere-conjugated detection antibodies and paramagnetic beads to capture and detect Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH) in human serum. The assay has a dynamic range of 0.037-18μIUml-1 with a low detection limit of 0.011μIUml-1, showing statistically acceptable accuracy, precision, and reproducibility [

84].

Surface Plasmon Resonance-Based Biosensors

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) based biosensors utilize surface plasmon waves to detect changes in refractive index resulting from molecular interactions at a metal surface. This label-free biosensing technology operates on the principle of SPR, wherein polarized light illuminates a metal surface at the interface of two media with different refractive indices, generating electron charge density waves known as plasmons. The intensity of reflected light decreases at a specific angle, known as the resonance angle, proportional to the mass on the surface. Noble metals like gold and silver are commonly used to create surface plasmons in SPR biosensors. In SPR, incident light at the resonance angle excites surface plasmons, causing a decrease in reflected light intensity. Any change on the metal surface, such as biomolecule binding, alters the resonance angle, known as the SPR shift, which is proportional to the change in surface mass. A typical SPR biosensor comprises a gold surface functionalized with bioreceptor molecules for target molecule capture. Real-time detection is achieved by monitoring changes in optical reflectivity as target molecules bind to the surface [

30,

73,

80,

85]. Researchers have developed a 1-D grating-based SPR biosensor and a carboxyl-functionalized molybdenum disulfide SPR detection assay, focusing on the detection of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) lung cancer biomarkers. The biosensor's design includes periodic gratings and multiple metal layers to enhance resonance effects. Using finite difference time domain simulations, the study confirms the biosensor's ability to detect biomarker-induced refractive index changes, enabling label-free early lung cancer detection [

86].

Optical Fiber-Based Biosensors

Optical fiber biosensors, also known as bio-optrodes, are sensor systems derived from optical fibers that utilize optical fields to detect and quantify biological species such as whole cells, proteins, and aptamers. These biosensors offer a promising alternative to traditional biomolecule assessment methods. One dependable optical fiber technique involves evanescent field sensing, mainly observed in tapered optical fibers. An evanescent wave is generated at the sample interface when light passes through an optical fiber due to total internal reflection. This field decays exponentially with distance from the interface, and it can be utilized to excite fluorescence near a sensing surface. Tapered optical fibers are commonly employed with various optical transduction processes, including variations in refractive index, absorption, fluorescence, and surface plasmon resonance (SPR). Optical fibers are typically silica or plastic, characterized by their small diameter, strength, durability, and flexibility. These fibers can withstand harsh and hazardous environments, making them suitable for remote sensing applications. Additionally, optical fibers enable multiplex sensing by transmitting multiple light signals simultaneously. They consist of a cylindrical core surrounded by cladding and function as circular waveguides [

30,

73,

80,

87]. A novel lasso-shaped fiber laser biosensor was developed for specific detection of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)-related cell adhesion molecules 5 (CEACAM5) protein in serum samples. Emphasizing the need for high sensitivity and reproducibility in cancer biomarker detection for Point-of-Care Testing (POCT), the biosensor offers a solution by capitalizing on the optical fiber-based transduction principle. The biosensor operates based on changes in the spectral characteristics of a fiber laser induced by biomolecular binding. The ultra-narrow linewidth of the laser facilitates precise spectral analysis, enabling the detection of minute variations in the lasing signal resulting from biomolecular interactions [

88].

Figure 2 provides an overview of each optical biosensor type's fundamental principles and configurations, highlighting their unique mechanisms for detecting and quantifying biological species.

3. Types of Biosensors for Cancer Detection

3.1. Enzymatic and Non-Enzymatic Biosensors

Enzymatic biosensors use enzymes as the recognition element to detect and measure specific substances in a sample [

89]. These biosensors are designed to convert a biochemical signal from an enzymatic reaction into a measurable output, often an electrical signal. This type is characterized by its high specificity for their target molecules, which is also related to selectivity to detect and measure the concentration of a particular analyte, reducing the interference from other substances present in the sample [

90]. It also can often detect low concentrations of the target analyte, providing a sensitive response to changes in concentration. The most relevant fact is that enzymatic biosensors are typically biocompatible, allowing their integration into biological systems without causing any harm [

91].

It is also necessary to identify that enzymatic biosensors have some limitations, such as their sensibility to environmental factors such as pH or temperature fluctuations. The immobilized enzymes may degrade over time, affecting the biosensor's performance. This can introduce a new research question about how enzymatic biosensors can be improved to reduce their possible difficulties [

92].

Non-enzymatic biosensors are an alternative approach that aims to overcome some limitations by using non-biological recognition elements while maintaining high sensitivity and selectivity. To better understand the functioning of this kind of biosensor, it is essential to highlight that they can detect and measure specific substances in a sample without relying on enzymes as the recognition element. Instead, they use non-biological materials or components to achieve selective and sensitive detection of target analytes. Non-enzymatic biosensors can overcome the limitations of enzymatic biosensors by exhibiting stable long-term characteristics, high-cost performance, high sensitivity, electron transfer, and high electrocatalytic activity [

93]. Also, their resistance to environmental factors makes them more robust in diverse operating conditions, and they can be manufactured using a wider variety of materials compared to the enzymatic ones [

3].

Enzymatic biosensors hold significant promise for cancer applications due to their ability to detect specific biomolecules associated with cancer development and progression. These biosensors typically consist of enzymes integrated with transducers that convert biochemical signals into measurable electrical or optical outputs [

57,

69]. In the context of cancer, enzymatic biosensors can detect cancer-specific biomarkers such as enzymes, proteins, or nucleic acids in bodily fluids or tissue samples with high sensitivity and specificity. This enables early cancer diagnosis, disease progression monitoring, and treatment efficacy assessment. Moreover, enzymatic biosensors offer rapid detection, low cost, and portability, making them suitable for point-of-care testing and remote monitoring applications.

Non-enzymatic biosensors represent a promising avenue for cancer applications, offering distinct advantages over enzymatic counterparts. These biosensors utilize non-biological recognition elements such as aptamers, antibodies, or molecularly imprinted polymers to bind to cancer-specific biomarkers selectively. By leveraging the unique molecular interactions between these recognition elements and target molecules, non-enzymatic biosensors can detect cancer biomarkers with high specificity and sensitivity [

94]. Additionally, their compatibility with various transduction mechanisms, including electrochemical, optical, and surface plasmon resonance, enables versatile detection platforms tailored to specific cancer biomarkers and sample types.

3.2. Biomarkers

Biomarkers are measurable indicators of biological processes, conditions, or states within an organism. These can be objectively measured substances, molecules, or genes, aiding disease diagnosis, treatment selection, and monitoring therapeutic efficacy [

95].

Biomarkers in cancer provide valuable insights into the development, progression, and response to the treatment of cancerous tumors. Biomarkers such as specific genetic mutations, protein expression levels, or abnormal cellular features serve as diagnostic tools to identify and characterize the existence of cancer [

96]. Additionally, it is possible to use biomarkers to recognize the prognostic of cancer patients, guiding clinicians in determining the most appropriate treatment strategies and personalized therapies. Through monitoring of biomarkers during treatment, healthcare providers can assess the effectiveness of therapies and make informed decisions regarding adjustments or changes to treatment regimens. Moreover, biomarker-driven clinical trials enable the development of targeted therapies tailored to individual patients, ultimately improving outcomes and advancing the field of oncology [

97].

For the case of skin cancer, and acknowledging the existent types of this, it is possible to identify biomarkers related explicitly to the presence of this condition. The most common biomarkers associated with skin cancer encompass a range of molecules and proteins reflective of disease progression and aggressiveness. In melanoma, multiple biomarkers are identified as diagnostic tools, such as Human Melanoma Black-45 (HMB-45), Melan-A, tyrosinase, microphthalmia transcription factor, and S100, which are described as immunohistochemical markers because they allow the detection of this type of cancer despite its cytomorphological variants [

98]. When checking on the most common types of skin cancer, it is essential to introduce two kinds of carcinoma in this section: basal cells (BCC) and cutaneous squamous cells (CSCC). BCC has a characteristic related to the difficulty it presents with differentiation from trichoblastoma, so there are two novel biomarker candidates: Meteorine Like Peptide (METRNL) and Asprosin, where METRNL presented an overexpression in the lesion area of the trichoblastoma, but Asprosin did not increase, but in BCC samples they both are relatively higher [

99]. Otherwise, CSCC is vitally detected through MYBL2 and TK1, demonstrating the cancer progression in analyzing differentially expressed genes (DEGs) samples [

100].

The articles reviewed in the paper's research phase identified different biomarkers related exclusively to skin cancer using biosensors of various types and detection mechanisms with their operation conditions. It is also important to mention the materials used to build up the biosensor to clarify the features related to their properties. In 2019, CDs and molecular beacon-based and AuPt nanoparticles, vertical graphene (VG) sheets, and glassy carbon electrode (GCE) were used for the manufacturing of biosensors that detected MicroRNA-21 and Alpha-Fetoprotein (AFP), respectively. They are both skin cancer biomarkers. The CDs and molecular beacon-based one detect MicroRNA-21. In contrast, AuPt nanoparticles, vertical graphene (VG) sheets, and glassy carbon electrodes (GCE) are used to detect Alpha-Fetoprotein (AFP). These biosensors demonstrate the potential of using advanced materials and detection mechanisms for the early and accurate diagnosis of skin cancer.

Then, B16-F10 cells were detected as skin cancer biomarkers. Still, there is particularity in its classification of biosensors because they do not fit in any of the analytes related to the enzymatic or non-enzymatic structure; thus, they can be classified under a different differentiation criterion. Finally, in 2023, using antimonide nano-flakes (AMNFs) and carbon dots, it was possible to sense MicroRNA-21 again using an electrochemical detection mechanism. It also included the detection of HER2 (human epidermal growth factor) with a biosensor made with Carboxylic acid group-rich graphene quantum dots (GQDs) modified with gold nanoparticles and a porphyrin binuclear framework (CoP-BNF) to modify the glassy carbon electrode, because it is noted that some biomarkers are not specific for just one type of cancer but for grouping them according to the type of cells or tissues involved [

57]. A summary of the biomarkers utilized in various biosensors and the respective detection conditions can be found in

Table 2.

4. Characterization of Biosensors

4.1. Characteristics of a Biosensor

The primary attributes of biosensors are selectivity, linearity, stability, repeatability, and sensitivity. Specific analytes can be identified among other chemicals according to selectivity, and consistent results from repeated experiments are guaranteed thanks to repeatability. Stability refers to the biosensor's resistance to environmental perturbations to provide accurate measurements throughout time. The ability to detect minute amounts of an analyte is determined by sensitivity, which is important for medical applications. Finally, linearity guarantees a precise and direct correlation between the measured response and the analyte concentration, necessary for accuracy over a range of concentrations [

91,

102,

103,

104,

105].

4.2. Techniques for the Characterization of Electrochemical Biosensors

4.2.1. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy is a technique involving the application of an alternating current signal to an electrochemical system and measuring the frequency response of the resulting impedance. It allows the characterization of resistance and capacitance at the electrode-electrolyte interface and charge transfer processes and chemical reactions at the interface [

105,

106].

EIS has emerged as a crucial tool in detecting and analyzing various biomarkers and biological entities. In a 2021 study, EIS was employed to develop an impedimetric detection system for glioma cells using sulfur-doped graphene quantum dots and gold-carbon nanospheres. This system proved effective in buffered solutions and complex biological samples like human serum, highlighting its potential for real-time biomedical applications [

67]. Furthermore, in a subsequent study from 2022, EIS was utilized to confirm the successful immobilization of DNA probes on carbon dots, vital for susceptible detection of the BRCA1 gene in real samples and cellular imaging. The stabilization of DNA probes on the surface of quantum dots was verified through fluorescence spectroscopy and EIS [

36].

Additionally, in an innovative approach in 2023, a bimetallic MXene quantum dot-based electrochemiluminescence (ECL) sensor was developed for miRNA-27a-3p detection. EIS played a crucial role in confirming the successful construction of the sensor system, and the linear relationship between ECL intensity and miRNA-27a-3p concentration demonstrated the biosensor’s selectivity and sensitivity [

69]. These studies underscore the fundamental role of EIS in developing and characterizing biomolecular detection systems, paving the way for research and application in clinical diagnostics and biotechnology. The characteristics of the studies that used EIS for electrochemical characterization are found in

Table 3.

4.2.2. Cyclic Voltammetry (CV)

Cyclic voltammetry is an electrochemical technique where a reversal experiment is conducted by changing the direction of the potential scan at a specific time or at a designated switching potential. During the experiment, the applied potential varies linearly with time, and upon reaching the reversal point, the scan direction is reversed. This is done to observe the electrochemical response of the system in both scan directions [

105,

106,

107,

108].

CV is a pivotal technique in the electrochemical characterization of biosensors, as demonstrated in two distinct studies. In the first investigation from 2019, a novel electrochemiluminescence (ECL) immunosensor for detecting CA15-3 in human serum was meticulously evaluated. The sensor exhibited remarkable stability through continuous cyclic voltammetry, as evidenced by consistent ECL signals across multiple scanning cycles [

34].

The ECL immunosensor demonstrated high selectivity, effectively distinguishing interference substances and explicitly responding to samples like CA15-3. It exhibited remarkable reproducibility, with cyclic voltammetry curves remaining nearly constant over 11 consecutive scans and an RSD below 2.3% for CA15-3 measurements. Additionally, it showed stability with only a 10.4% decrease in ECL signal after one month of storage at 4°C. The sensor achieved a LOD of 0.0017 U mL⁻¹ and maintained a linear concentration range from 0.005 to 500 U mL⁻¹ [

34].

In a complementary study from 2020, catalase-immobilized antimonide quantum dots (Cat@AMQDs) were explored as an electrochemical biosensor for the quantitative determination of H2O2 from CA-125 diagnosed ovarian cancer samples. Through CV, the modified electrode exhibited distinct redox activity, featuring oxidation and reduction peaks indicative of the redox activity of Cat@AMQDs-GCE [

47]. Together, these studies underscore the utility of CV in the comprehensive electrochemical characterization of biosensors, elucidating their stability, selectivity, reproducibility, and optimal operating conditions for diverse clinical applications.

The Cat@AMQDs-GCE electrode demonstrated selectivity for H2O2 detection, even in interferences like ascorbic acid and glucose. The modified electrode retained its redox behavior over 30 cycles, with a recovery rate of 95% to 103.4%. Additionally, the electrode's stability was evaluated through 30 cyclic voltammetry cycles for 1 mM H

2O

2 in 0.1 M PBS at pH 7. The LOD was 4.4 μM, making it suitable for biological analysis, and it showed linearity up to 0.989 [

47].

Together, these studies underscore the utility of CV in the comprehensive electrochemical characterization of biosensors, elucidating their stability, selectivity, reproducibility, and optimal operating conditions for diverse clinical applications.

In recent years, significant progress has been made in developing biosensors for detecting cancer cells, utilizing electrochemical techniques such as CV EIS. In a study conducted in 2018, an impedimetric biosensor was employed to identify cancer cells using the carbohydrate-binding ability of Concanavalin A (ConA). CV and EIS tests were performed on an Au||ConA-GQD@Fe3O4 electrode to characterize its performance. CV demonstrated a decrease in the

Fe(CN)63-/4- peak intensity with increasing glucose concentration, demonstrating the immobilized ConA's ability for glucose detection. At the same time, EIS revealed changes in charge transfer resistance (Rct) upon adhering to different cell lines, notably improving impedance after incubation with cancerous cells HeLa and MCF-7 [

109]. In another study from 2019, a strategy based on the concatenation of aptamers-DNA and quantum dots was proposed for the ultrasensitive detection of tumor cells through mercury-free anodic stripping voltammetry. Both EIS and CV were employed to investigate the biosensor assembly process, unveiling alterations in electronic transfer resistance (Ret) and inhibiting the electron transfer process by adding biomolecules [

51].

In the same year, an immunosensor for quantitatively detecting the breast cancer biomarker UBE2C was also developed. CV and EIS tests during immunosensor fabrication showed significant changes in charge transfer resistance (Rct), reflecting modification of the electrode/electrolyte interface and obstruction of the electron transfer process due to biomolecule immobilization [

58]. Furthermore, during that period, a polyaniline-decorated graphene quantum dots nanowire was suggested for impedimetric detection of the carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). CV and EIS tests revealed alterations in current intensity and charge transfer resistance upon the electrode surface modification with biomolecules, underscoring the significance of graphene quantum dots in amplifying electrode functionality and achieving effective CEA detection [

110].

A study conducted in 2021 delved into the utilization of an integrated 0D/2D heterostructure comprising bimetallic CoCu-ZIF nanosheets and carbon quantum dots derived from MXene for impedimetric cytodection of B16-F10 melanoma cells. The electrochemical measurements involved various techniques, including EIS and CV, to characterize cytosensor fabrication and cell detection [

101]. Similarly, during the same year, another investigation introduced an impedimetric aptasensor for the HER2 biomarker utilizing graphene quantum dots, polypyrrole, and electrodes modified with cobalt phthalocyanine. Cyclic voltammetry studies provided insight into various modified electrodes' electron transfer properties. Additionally, EIS yielded valuable data to characterize the interface properties of the modified electrodes, assisting in their differentiation and characterization [

53].

In a study conducted in 2022, the CVs and EIS measurements were performed on various modified electrodes in 1 mM

[Fe(CN)]63−/4− (in 0.1 M KCl) electrolyte. The CVs exhibited significant changes in peak potentials and shapes upon modification, indicating alterations in electron transfer properties. Meanwhile, the EIS responses, represented by Nyquist plots, provided insights into the electrode surface’s charge transfer resistance (Rct). The Rct values were used to assess the conductivity of the modified surfaces, with higher Rct indicating hindered electron transfer [

57]. In addition, in a study from 2023, cyclic voltammetry was employed to investigate electron transfer properties among modified surfaces using ferricyanide as a marker. The ΔEp values, representing anodic to cathodic peak potential separation, were analyzed to evaluate electron-transporting abilities. Lower ΔEp values were indicative of desirable electron transfer properties. EIS was also used to study surface-modified electrodes, with Rct values obtained to characterize the charge transfer resistance. The data from both CV and EIS agreed, with surfaces exhibiting lower ΔEp values demonstrating lower Rct values, suggesting enhanced conductivity [

59]. These investigations highlight the crucial role of cyclic voltammetry and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy in advancing biosensor technology, showcasing their versatility and effectiveness in electrochemical analysis and sensor development. The Characteristics of studies that use EIS and CV for electrochemical characterization are found in

Table 4.

4.2.3. Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV)

Differential pulse voltammetry is an electrochemical technique that allows for even better sensitivities than normal pulse voltammetry. This technique is based on a scheme of reduced-amplitude pulses, where the base potential is steadily changed in small increments for most of a drop's lifetime. The pulse height is constant relative to the base potential, and two current samples are taken during each pulse cycle. The difference in current between these two samples is recorded against the base potential, which characterizes the electrochemical response of the system. Differential pulse voltammetry is used to study complex electrochemical reactions and is especially useful for detecting analytes with high sensitivity and selectivity [

105,

107].

In a 2019 study, EIS was utilized to analyze the interfacial properties of electrodes throughout various modification stages, from the glassy carbon electrode (GCE) to the final sensor formation. Nyquist plots reveal changes in the charge transfer resistance (Rct), confirming the success of immunological reactions at each electrode modification step. Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) is employed for alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) detection, demonstrating a linear relationship between AFP concentration and peak current in antibody immobilization-based and label-free detection strategies [

49].

In a second study from 2022, Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) was used to investigate chemical reactions involving electron transfer during electrode surface modification with electrochemically exfoliated graphene quantum dots (GQDs) and CD44 antibodies. CV results show a gradual decrease in peak current with each modification step, confirming the effectiveness of antibody immobilization and biolayer formation on the electrode. Furthermore, EIS was employed to study changes in charge transfer resistance (RCT) in modified electrodes, demonstrating a decrease in RCT with GQDs incorporation and a subsequent increase with CD44 antibody immobilization and bovine serum albumin (BSA) adsorption. Lastly, Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) is utilized for ultrasensitive detection of the CD44 antigen, showing a linear response over a wide concentration range and high sensitivity of the developed biosensor [

68].

The same year, a mobile device integrated graphene oxide quantum dots-based electrochemical biosensor was developed to detect miR-141 as a pancreatic cancer biomarker. This study employed a combination of CV, DPV, and EIS techniques. CV analysis revealed a concentration-dependent decrease in current values as miR-141 concentration increased, suggesting the binding of miR-141 to the sensor and hindrance of electron transfer at the surface. DPV measurements further validated the biosensor's sensitivity, demonstrating a proportional drop in current values with increasing miR-141 concentration. Additionally, EIS analysis provided insights into changes in electron transfer resistance, confirming the effectiveness of the biosensor preparation and supporting the findings obtained from CV analysis [

111].

In 2023, an ultrasensitive electrochemical biosensor was developed to simultaneously detect microRNA-21 and microRNA-155 based on the specific interaction of antimonide quantum dots with RNA. DPV experiments were conducted to scrutinize each step of the modified electrode, confirming the validity of electrochemically amplified signals and the microRNA complexes modified with single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs). DPV results revealed significantly higher oxidation peaks of NB (-6.4 V) and MB (-0.3 V) in the single-stranded RNA complex. Moreover, a notable reduction in the oxidation peaks of NB and MB was observed after the addition of complementary microRNAs, indicating facile desorption of the hybridization target from the antimonide quantum dots interface. Sequential characterization of the sensor assembly was performed via cyclic voltammetry (CV). Higher

Fe(CN)63-/4 oxidation peaks were observed on the SWCNTs-modified electrode, followed by the self-assembly of the AMQDs/ssRNA reactive complex on the SWCNTs/SPCE surface. Subsequently, the detection of microRNA-21 and microRNA-155 exhibited increased oxidation peaks of

Fe(CN)63-/4, signifying the successful orientation of the microRNAs [

112].

Electrochemical DNA biosensors with a dual-signal amplification strategy were also designed for highly sensitive HPV 16 detection. The utilization of cyclic voltammetry enabled the characterization of each operational step, demonstrating improved electron transfer efficiency due to the self-assembled APTES film and a gradual decline in oxidation peaks owing to DNA hybridization and the addition of DNA probes [

52]. These techniques enabled the validation of amplified signals, studying electrode modification, optimizing electron transfer, and assessing biosensor sensitivity. While not new, the strategic application of these techniques is crucial to achieving sensitive and specific detection of relevant biomolecules in medical and biotechnological applications. The characteristics of the studies that used DPV for electrochemical characterization are found in

Table 5.

4.2.4. Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV)

Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) is a highly versatile electrochemical technique that combines the best features of various pulse voltammetric methods. It integrates the background suppression and sensitivity of differential pulse voltammetry, the diagnostic value of normal pulse voltammetry, and the ability to interrogate electrochemical products akin to reverse pulse voltammetry directly. Typically performed at a stationary electrode, SWV employs a unique waveform involving measurement cycles without diffusion layer renewal between cycles. This technique provides detailed insights into the kinetics and thermodynamics of electrochemical reactions and is executed using computer-controlled potentiostatic systems for precise and efficient data analysis [

105,

107,

113].

In 2018, SWV was performed within a potential range of -1.0 to -0.3 V at a scan rate of 0.1 V/s, while EIS was analyzed in a frequency range of 10^6 to 0.1 Hz with an AC amplitude of 5 mV. Both techniques were used in a 0.1 M KCl solution containing

Fe(CN)63-/4. Finally, the electrochemical response was determined through differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.0) with a pulse amplitude and width of 50 mV and 0.05 s, respectively. These techniques enabled the sensitive detection of MCF-7 cells, demonstrating the efficacy of the proposed biosensor for diagnostic applications [

70].

In 2021, a notable study introduced an electrochemical platform incorporating gold nanoparticles, graphene quantum dots, and graphene oxide films. CV responses of the biosensor were extensively assessed across various scan rates in a KCl solution containing Fe(CN)63-/4 , demonstrating diffusion-controlled electron-transfer processes.

Moreover, SWV elucidated distinct peaks corresponding to redox indicators, facilitating concurrent multiple microRNA detections. Under optimal assay conditions, SWV peak currents exhibited correlations with miRNA-21, miRNA-155, and miRNA-210 concentrations, enabling ultrasensitive detection with wide linear ranges and low detection limits (LODs). Additionally, EIS revealed enhancements in charge transfer resistance (Rct) upon modification of electrode surfaces, particularly with the incorporation of gold nanoparticles, graphene quantum dots, and graphene oxide, thereby improving electrochemical performance for microRNA detection [

48]. Another notable study in 2021 presented an electrochemical biosensor utilizing antimonide for the ultrasensitive detection of microRNA-21. Characterization through CV and EIS elucidated the stepwise assembly process, showcasing the successful construction of the microRNA biosensor. Under optimal parameters, SWV unveiled distinct electrochemical signals attributed to the oxidation of Cd2+ on the biosensor surface, enabling the precise determination of microRNA-21 concentrations with exceptional sensitivity and low detection limits [

54].

In 2023, the electrochemical immunosensor for ultra-low detection of Human Papillomavirus biomarkers for cervical cancer underwent CV analyses to assess its performance. The SWV method was employed to monitor the reaction between the immunosensors and different concentrations of HPV-16 L1 antigen. The continuous suppression of redox peaks upon increasing antigen concentration indicated excellent complexation between the antibody and antigen. Despite the broader peak response of the Onion-like carbon (OLC)-based immunosensor, the polyacrylonitrile (OLC-PAN)-based counterpart exhibited superior linearity, enabling its use for HPV-16 L1 antigen detection across various concentrations [

72]. The characteristics of the studies that used SWV for electrochemical characterization are found in

Table 6.

4.2.5. Chronoamperometry (CA)

CA is an electrochemical technique that records the electric current as a function of time during an electrochemical experiment. This method involves applying a constant potential to an electrode and measuring the current flowing in response to the electrochemical reaction at the electrode-solution interface. Chronoamperometry helps study the kinetics of electrochemical reactions, the formation of electrochemical products, and the dynamics of electrochemical interfaces. It allows for investigating how electric currents vary over time and provides valuable insights into the underlying electrochemical processes [

105,

107].

In 2019, various electrochemical techniques, including CV, DPV, EIS, and CA, were employed to validate the progression of electrode modification. The CV method recorded cyclic voltammograms at a scan rate of 100 mV/s in a 2 mM catechol solution to assess the redox reactions at each modification step. Modifying the glassy carbon electrode (GCE) with Bio AuNP and Bio AuNP/CD exhibited increased oxidation peak currents, attributed to the unique properties of carbon dots (CDs) enhancing surface-to-volume ratio and quantum size effects. DPV analyses validated the CV results, while EIS illustrated changes in electron transfer resistance after each modification step. CA facilitated the rapid and reproducible registration of signals post-addition of CD, Bio AuNP, aptamer sequence, antigen, probe DNA, and target oligonucleotide [

114]. These findings underscore the utility of electrochemical methods in monitoring and optimizing the fabrication of biosensors, paving the way for enhanced analytical capabilities in biochemical sensing applications.

The biosensor demonstrated high selectivity, showing no significant decrease in peak current after hybridization with mismatch targets or non-complementary DNA sequences. It exhibited excellent reproducibility, with relative standard deviations (RSDs) of 0.014 and 0.012 for the DNA sensor and aptasensor. Negligible changes in peak current confirmed stability after one week of storage at 4°C. The sensor also achieved low detection limits of 1.5 pM for DNA and 0.26 pg mL−1 for the aptamer sensor. Additionally, it maintained linear relationships between peak currents and the logarithm of target DNA and CEA antigen concentrations across a wide range [

114].

4.2.6. Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV)

LSV is an electrochemical technique that understands a system's behavior by sweeping the potential linearly with time while recording the resulting current. Compared to other methods, LSV provides a more efficient and comprehensive way to analyze electrochemical reactions, offering insights into the presence of different species and the kinetics of reactions. It is conducted with sweep rates ranging from 10 mV/s to 106 V/s and is commonly used to obtain current-potential curves, aiding in the qualitative and quantitative analysis of electrochemical processes [

105,

107].

In a 2021 study, various electrochemical techniques were employed to optimize the sensor's performance. CV technique was utilized for the electrodeposition of graphene quantum dots (GQDs) onto the precleaned glassy carbon electrode (GCE), with the cycle number optimized to achieve the best thickness of GQDs on the GCE surface. EIS

) was subsequently employed to confirm the CV results. Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) were electrochemically synthesized using the CA technique after GQD deposition to enhance the conductivity of the modified electrode. The linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) reduction technique was used to optimize CHA voltammograms and determine the appropriate potential for AuNP deposition. Additionally, the optimum volume of biotinylated antibodies immobilized on the modified electrode was determined using LSV oxidation results. Finally, SWV was employed to generate a calibration curve correlating the electrical current with the number of immobilized cells on the modified electrode, showcasing the sensitivity and utility of the developed electrochemical cytosensor [

64].

The biosensor demonstrates unique specificity for the biorecognition of KG1a cells, indicating high selectivity. It exhibits excellent reproducibility, with a relative standard deviation (RSD) of 1.5% for 50 repeated measurements at a concentration of 1 cell/mL, highlighting its remarkable stability. The sensitivity of the cytosensor is reflected in its LOD, determined to be 1 cell/mL. Furthermore, it shows good linearity with a linear dynamic range from 1 to 25 cells/mL [

64].

It is evident in the articles that most of these studies employ two or more electrochemical techniques. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and cyclic voltammetry (CV) are the most used techniques. Combining these methodologies has become a common practice due to their ability to comprehensively evaluate biosensors' electrochemical and surface properties. This trend underscores the importance of supporting findings with complementary approaches, contributing to a more thorough and reliable characterization of biosensors for cancer detection.

4.3. Techniques for the Characterization of Optical Biosensors

The evolution in the characterization of optical biosensors from 2019 to 2023 highlights significant advances in biomedical detection, starting with photoluminescence spectroscopy to study the emission properties of quantum dots and progressing to sophisticated techniques such as confocal microscopy to visualize the interaction between complexes and tumor cells [

40,

115]. Innovations include the use of fluorescence emission spectra and Raman spectroscopy to analyze the interaction with microRNA and carbon nanostructures in cells, expanding to a combination of methods such as UV-vis, FTIR, SEM, TEM, and CLSM to evaluate the optical, structural, and morphological properties of the biosensors [

94,

116,

117,

118]. This progress culminated in the implementation of CLSM in 2023 to detail cellular uptake and intracellular trafficking of nanoparticles, highlighting the importance of comprehensive characterization for developing and applying optical biosensors in medical diagnostics, particularly in cancer detection [

119].

Table 7 summarizes the key characteristics and methodologies of studies utilizing optical characterization techniques, emphasizing the range and evolution of methods applied over this period.

5. Summary and Conclusions

The review highlights recent advancements in electrochemical and optical biosensors utilizing carbon dots (CDs) and glassy carbon (GC) for cancer detection. The studies demonstrate that these nanostructured materials have greatly improved biosensor performance in terms of sensitivity, selectivity, and stability. A comparison between optical and electrochemical approaches reveals their respective advantages and challenges. Optical biosensors are recognized for their high sensitivity, rapid response, and user-friendly nature, while electrochemical biosensors offer better selectivity, robustness, and the potential for miniaturization. The combination of the unique properties of CDs and GC has led to the development of hybrid biosensors with enhanced detection characteristics.

In summary, the literature indicates that CQD- and GC-based biosensors hold promise for the early and accurate detection of various types of cancer. Compared to conventional methods, these devices significantly improve key parameters, such as sensitivity, selectivity, and stability. However, every approach is deemed superior, and the choice of biosensor type will depend on the application's specific requirements. The review also underscores the significance of electrochemical techniques, such as electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), cyclic voltammetry (CV), and differential pulse voltammetry (DPV), in comprehensively characterizing biosensors. These techniques provide valuable information on electron transfer properties, electrode surface modification, and overall device performance, thereby contributing to developing and optimizing advanced biosensing platforms. Continued innovation in the synthesis and modification of CDs and GC, in addition to the development of hybrid strategies combining the strengths of optical and electrochemical approaches, is expected to drive further significant advances in the early detection and monitoring of cancer through highly efficient and reliable biosensors.

6. Future Perspectives

Future research in developing electrochemical and optical carbon dots (CDs) and glassy carbon (GC) biosensors should center on leveraging these technologies for more precise and early cancer detection and potential therapeutic applications. Integrating these biosensors with novel biomarkers, particularly those based on single genes or proteins, can facilitate precise detection tailored to individual cancer types.

To propel this field forward, scientists should prioritize the development of multifunctional platforms capable of simultaneously measuring multiple outputs from a single biosensor. This approach enhances diagnostic accuracy and paves the way for personalized treatment strategies. Further research is essential to improve the stability and reduce the cost of nanostructure fabrication, particularly in functionalizing metal layers with 2D materials, antibodies, aptamers, and proteins. Overcoming these challenges will be pivotal for commercializing and widespread adoption of these biosensors in clinical settings.

Moreover, exploring the combination of optical and electrochemical detection mechanisms within a single device could yield hybrid biosensors with superior performance characteristics. Such innovations could revolutionize cancer diagnostics, enabling earlier detection and more effective monitoring of treatment responses. Future investigations should also focus on synthesizing and modifying CDs and GC, exploring their potential in detection, targeted drug delivery, and real-time monitoring of therapeutic outcomes. By addressing these areas, the scientific community can significantly contribute to developing next-generation biosensors that offer robust, cost-effective cancer detection and treatment solutions.

Author Contributions

The following statements should be used: Conceptualization, P.C.C. and F.F; methodology, A.O.O.-M., D.C.R.-B., and F.F.; software, J.G.L., M.M., V.A., and V.G.; validation, D.C.R.-B., and F.F.; formal analysis, P.C.C., and A.O.O.-M.; investigation, J.G.L., M.M., V.A., V.G., and F.F.; resources, F.F.; writing—original draft preparation, J.G.L., M.M., V.A., and V.G.; writing—review and editing, A.O.O.-M., D.C.R.-B., and F.F.; visualization, D.C.R.-B., and F.F.; supervision, F.F.; project administration, D.C.R.-B., and F.F.; funding acquisition, D.C.R.-B., and F.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding for project No. 22INTER-453 for the Universidad Autónoma de Occidente and the Universidad del Rosario.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the Universidad Autónoma de Occidente and the Universidad del Rosario, the institutions that supported this research project No. 22INTER-453.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References