1. Introduction

Ceramic inlays and partial crowns are a globally recognized type of restoration with clinically excellent survival rates[

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. This applies equally to chairside work and CAD/CAM restorations[

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. However, clinical problems still lie in the technique sensitivity of the adhesive systems[

7,

8,

9], the selection of the polymerization mode of the adhesive and luting composite[

10,

11,

12] and the accurate, ceramic-compatible preparation[

13]. The latter depends not only on the tooth structure that can be adhesively stabilized but also on the extent of dentin caries to be excavated. The proximal cavity geometry after caries excavation is usually clinically irregular and in many cases deeper in dentin than in enamel, resulting in characteristic undermined enamel lamellae (

Figure 1).

Also when selective dentin caries excavation, which is generally scientifically recommended today, is practiced[

14], the majority of the carious biomass would still be removed, resulting in the same phenomenon. Three clinical scenarios are initially possible for the frequently occurring case of the described pronounced undermined enamel clasp: the cavity is left as it is and the enamel remains undermined there until adhesive cementation (

Figure 2a), the dentin groove is filled adhesively with directly applied composite (

Figure 2b) or the enamel lamella is completely removed in this area (

Figure 2c), which would hypothetically prevent the risk of fracture or cracking, but which almost always leads to complete proximal-cervical enamel loss and the restoration ends up in dentin/cement.

The aim of the present in-vitro study was to investigate these described pre-preparative/primary restorative scenarios with regard to their influence on adhesive performance of ceramic inlays and partial crowns, whereby the type of fabrication as well as marginal quality on the one hand and crack formation in enamel on the other hand were to be examined. In addition to the cavity geometry, different luting systems were also considered, i.e. a multi-bottle system (Syntac, Ivoclar, Schaan, Principality of Liechtensein) and a universal adhesive (Adhese Universal, Ivoclar) were combined with a dual-curing luting composite (Variolink Esthetic DC, Ivoclar).

The four null hypotheses of the study were that 1. the handling of the enamel lamella would have no effect on the adhesive performance (margin and enamel cracks), 2. that the luting system would have no effect on the different groups, 3. that there would be no difference between inlays and partial crowns and 4. that there would be no difference between chairside and labside ceramics.

2. Materials and Methods

192 caries-free human wisdom teeth of similar size (max. 3 mm difference) with >80% developed and undamaged roots, freshly extracted for therapeutic reasons, were included in the study. All patients had given written consent for their teeth to be used for scientific purposes, the study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration, and the study protocol was reviewed and approved by a local ethics committee (University of XXXXXXXXXXXXXX, project code 143/09). The sample teeth were stored in 0.5% chloramine-T for a maximum of 30 days, cleaned and examined for cracks by light microscopy (10x magnification). The sample size was determined by the maximum capacity of the experimental setup and was also based on the specifications of recognized studies in this field.

The sample teeth received standardized mod cavities with a proximal box level 2 mm above the amelo-cemental junction, 50% of which were further prepared into partial crowns with a vertical cusp thickness of 1.5 mm (

Figure 3). Cavities were prepared using a special ceramic set (expert set, Komet, Lemgo) in a handpiece with 3 cooling nozzles and a flow rate of 30 mL/min. Inner angles were rounded and the edges were not beveled. A 2x2x4 mm groove was prepared in the mesial box to simulate the often deeper caries excavation there (see

Figure 1). This groove was either left in place (G) or filled directly with composite (F; Adhese Universal self-etch, Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein and SDR, Dentsply Sirona, Konstanz, Germany, one layer). All light-curing processes were carried out with a Bluephase polymerization light (Ivoclar Vivadent), whereby the light intensity was continuously checked with a radiometer (Demetron Research Corp, Danbury, CT, USA) to ensure that 1000 mW/cm

2 was always reliably exceeded.

In group F, after the adhesive build-up was completed, finishing was carried out with the above-mentioned diamond bur to expose the enamel margins again; the composite areas were sandblasted for 5 seconds (Rondoflex 360 plus, KaVo, Biberach, Germany).

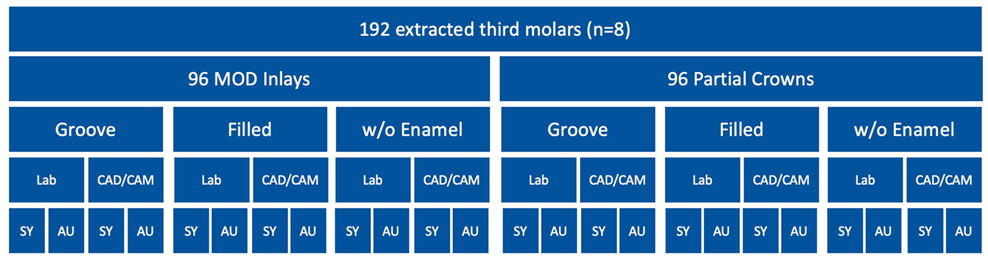

Table 1.

Flowchart of the group classification (SY: Syntac; AU: Adhese Universal).

Table 1.

Flowchart of the group classification (SY: Syntac; AU: Adhese Universal).

Conventional (Flexitime, Kulzer-Dental, Hanau, Germany) or optical (Omnicam, Cerec, Dentsply Sirona, Bensheim, Germany) impressions were taken of the cavities and chairside and labside ceramic inlays and partial crowns (e.max CAD/e.max Press, Ivoclar Vivadent) were fabricated. The ceramic underside was pretreated with 5% hydrofluoric acid (Vita Ceramic Etch, Vita Zahnfabrik, Bad Säckingen, Germany) for 20 s. After spraying and drying, silane (Monobond Plus, Ivoclar) was applied for 60 s and no additional adhesive was applied. The chairside restorations received temporary inlays and partial crowns (Luxatemp, DMG, Hamburg, Germany), which were cemented with TempGrip (Dentsply Sirona) and subjected to a shortened TMB (1000 x 50 N and 25 thermocycles). The final restorations were adhesively cemented with Syntac or Adhese Universal (Ivoclar) and Variolink Esthetic DC according to the manufacturer’s instructions, whereby the adhesive was polymerized separately in the cavity with Adhese Universal (20 s) and not with Syntac. Variolink Esthetic DC was polymerized for 20 s per side, a total of 120 s per restoration for Adhese Universal and 240 s for Syntac. The restoration margins were finished with Soflex discs (Solventum, Seefeld, Germany) in three decreasing grit sizes.

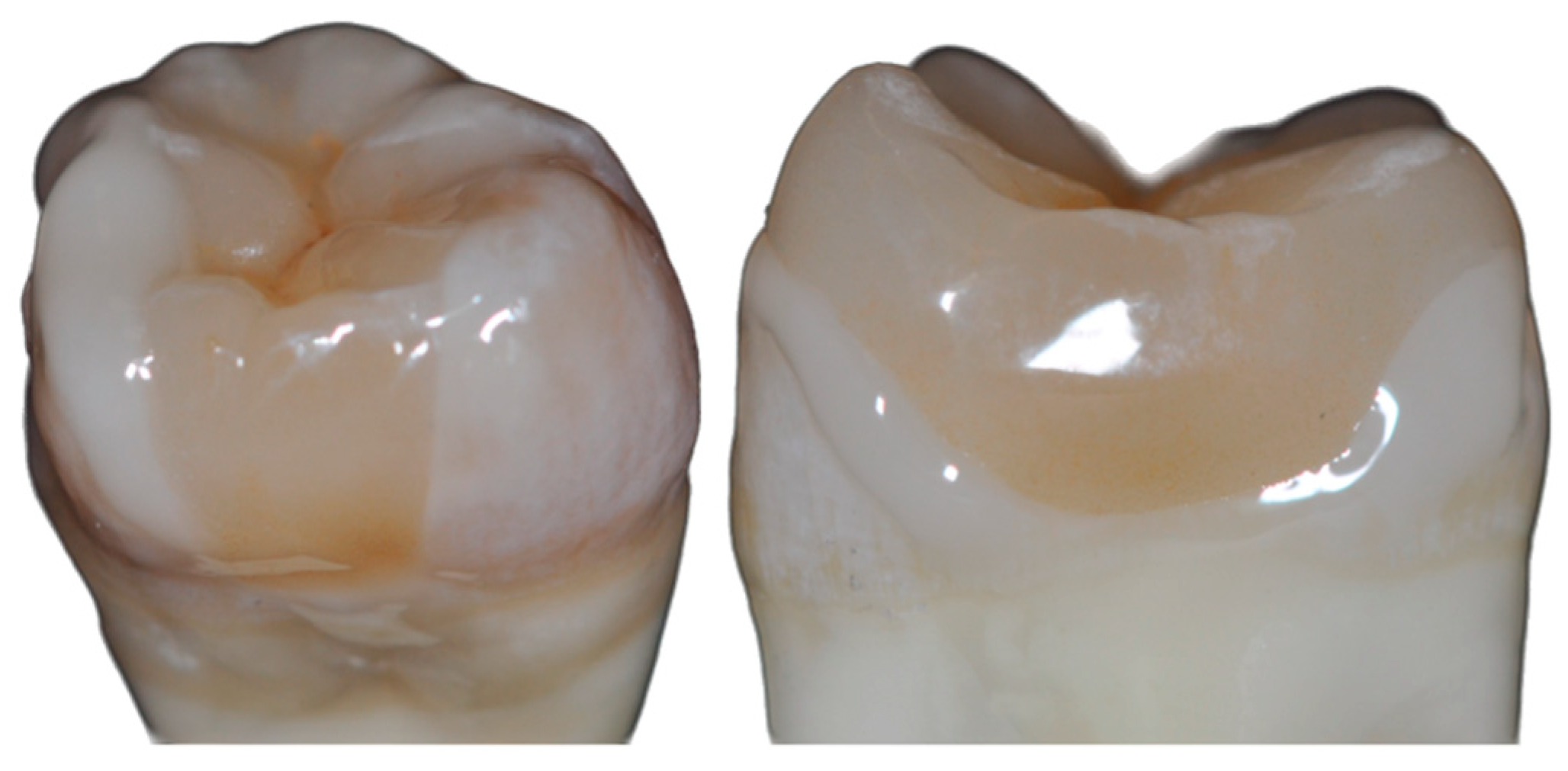

Figure 3.

Inlay vs. partial crown in vitro (here: labside procedure).

Figure 3.

Inlay vs. partial crown in vitro (here: labside procedure).

Directly after adhesive cementation (chairside restorations) or directly after provisional restoration (labside restorations) and after TMB, the total length of enamel cracks below the distal (control) and mesial proximal boxes on the original samples was measured by light microscopy (test groups G/F only; image: Z6 APO, Leica, Wetzlar / 10x under transmission; measurement: Photoshop CS6, Adobe Systems Software Ireland Limited, Dublin, Ireland;

Figure 4).

After 21 days of storage in distilled water at 37°C, the first impression was taken of the specimens (Flexitime) and a first set of epoxy resin replicas (Alpha-Die, Schütz Dental, Rosbach, Germany) was fabricated. Thermomechanical loading (TMB) of the sample teeth was performed in a chewing simulator (CS4 professional line, SD Mechatronik, Feldkirchen, Germany) under water. No artificial saliva or similar was used. Two sample teeth were installed in a chewing simulator chamber in such a way that its 6-mm steatite antagonist "chewed" two distal marginal ridges. The total number of mechanical cycles was 1 million at 50 N at a frequency of 0.5 Hz. Prior to this, the samples underwent 25,000 thermal cycles between 5°C and 55°C (30 s immersion time, THE 1100, SD Mechatronics;

Figure 5).

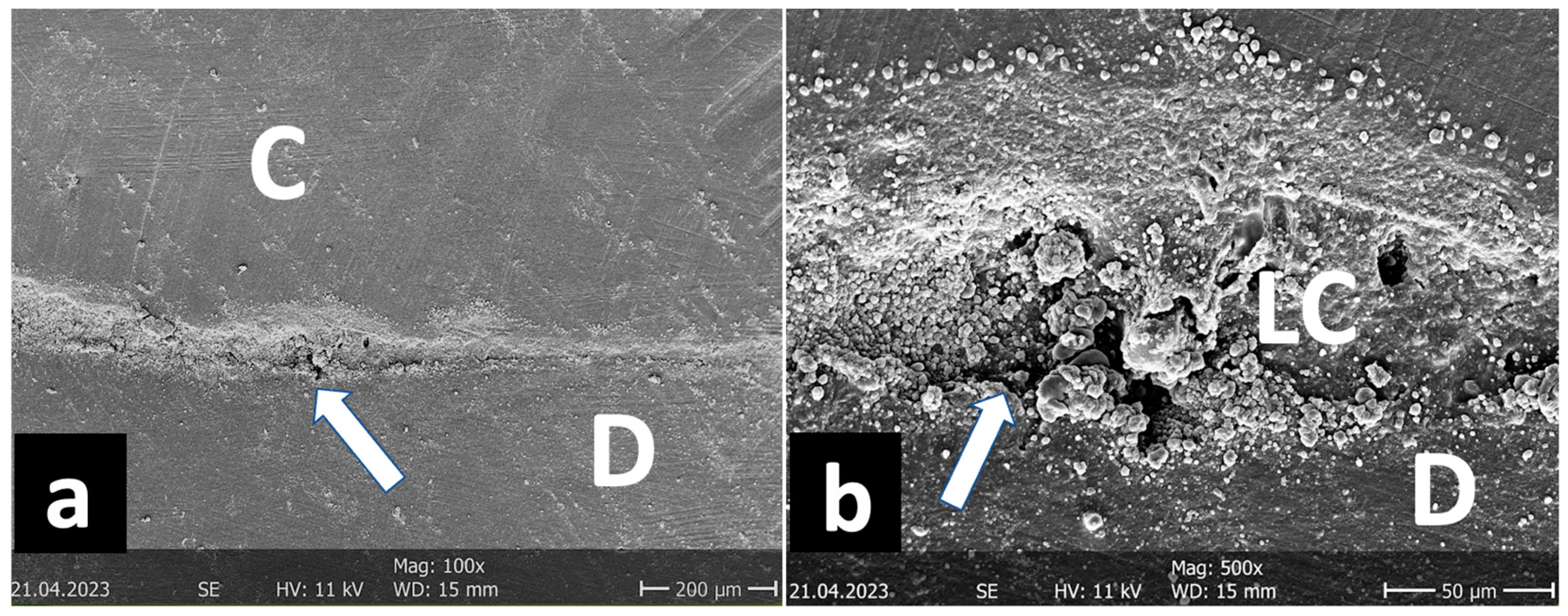

After TML, the next crack measurement was carried out and the second set of replicas was prepared. Both sets were analyzed under a scanning electron microscope (Phenom, FEI, Amsterdam, Netherlands) at 200x magnification. The marginal quality of the different interfaces (enamel luting composite, dentin luting composite, ceramic luting composite) was divided into "gap-free", "gap/irregularity" and "not assessable" and classified as a percentage of the gap-free margin in relation to the total margin. For better illustration, further SEM images were taken at different magnifications (

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9).

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). After testing the non-normal distribution (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test), significant changes over time were calculated using the Wilcoxon test and differences between the groups using the Mann-Whitney U test at a significance level of 5%.

3. Results

3.1. Marginal Quality

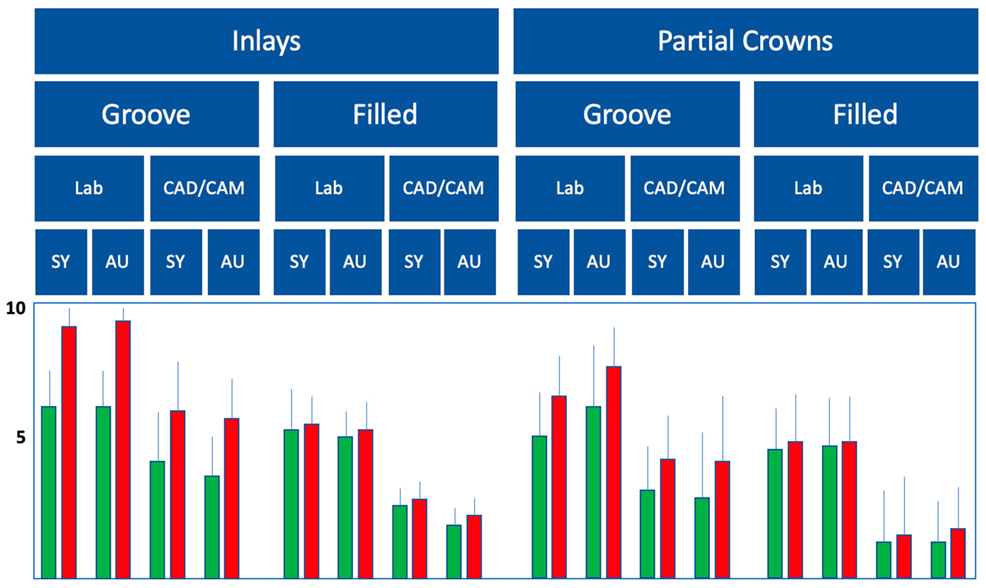

The results for SEM marginal quality evaluation are shown in

Table 2:

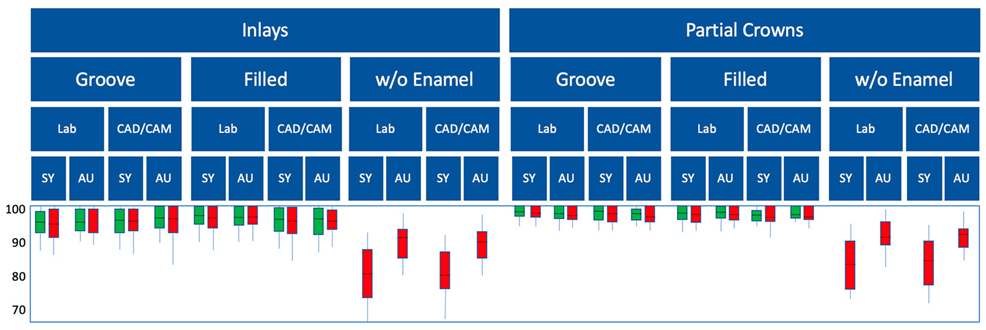

Table 2.

Results of the marginal quality (% gap-free enamel margin in the boxplot diagram with control/green and test groups/red, for the dentin groups only dentin margins; SY: Syntac; AU: Adhese Universal).

Table 2.

Results of the marginal quality (% gap-free enamel margin in the boxplot diagram with control/green and test groups/red, for the dentin groups only dentin margins; SY: Syntac; AU: Adhese Universal).

As the proportion of gap-free margins was initially 99-100% in all groups, the data was not shown for reasons of clarity. Regardless of the adhesive system, the marginal quality deteriorated significantly in all groups after TMB (p<0.05; Wilcoxon test;

Table 2). Also independent of the adhesive system used, the D groups generally showed significantly poorer marginal quality (p<0.05; Mann-Whitney U-test), with the universal adhesive performing better than the multi-step adhesive system (p<0.05; Mann-Whitney U-test;

Table 2). Subgroups G and F were similar in marginal quality regardless of the adhesive system (p>0.05; Mann-Whitney U-test;

Table 2) and not significantly worse than the controls (p>0.05; Mann-Whitney U-test;

Table 2). Partial crowns showed better marginal qualities in the enamel areas than mod inlays (p<0.05; Mann-Whitney U-test;

Table 2), in the dentin margins the difference between inlays and partial crowns was not significant (p>0.05; Mann-Whitney U-test;

Table 2).

3.2. Proximal enamel crack propagation

The evaluation of the proximal-cervical crack increase showed significantly less cracking at F than at G for both the inlays and the partial crowns (p<0.05; Mann-Whitney U-test;

Table 3). In general, significantly fewer cracks were observed in CAD/CAM restorations than in laboratory-fabricated restorations (p<0.05; Mann-Whitney U-test;

Table 3), with the greatest increase in cracking measured during the simulated provisional wearing time. Partial crowns showed fewer proximal enamel cracks than inlays (p<0.05; Mann-Whitney U-test;

Table 3).

4. Discussion

Thermomechanical loading (chewing simulation) is an established in-vitro method for the preclinical evaluation of different restorative materials[

15,

16] . The TMB represents a cyclic fatigue test that is very close to the clinical situation, where permanent, subcritical loads are generally far more common than events that lead directly to failure. Compared to other studies, the total number of cycles in the present study may be very high with 1 million, but here too we tended to follow the majority of laboratory studies on causal simulation and therefore chose the worst-case scenario. In our opinion, a direct transferability of X cycles of TMB to Y years of clinical exposure is not factual, but based on relevant in vitro-in vivo comparisons in the present study, one can assume a clinical equivalence period of approximately 10 years.

In view of the decision to define the distal, not additionally prepared proximal boxes as "control groups", at first glance this is a critical aspect of the present methodology, at least statistically. This definition could be viewed even more critically, since a one-tooth-to-two-tooth intercuspidation was simulated, as in the mouth, but the boxes under consideration were subjected to particular stress. However, a look at the results clearly shows that the mesial (test) and distal boxes (control) in the "good" groups did not differ significantly and therefore the chosen method of grouping appears acceptable.

When looking at the literature in the field of adhesive ceramic restorations, it is surprising that the problem presented in this study has never been investigated, as it is a phenomenon that certainly occurs millions of times in daily practice. It is obviously a rather trivial problem, but of considerable clinical relevance for daily routine. Whether disregarding the procedure suggested here automatically leads to clinical failure cannot, in all honesty, be completely proven. For the ultimate proof, the randomized, clinical-prospective study still remains the most suitable instrument[

2,

4,

7] . However, the latter is not ethically indicated in view of the experimental question at hand.

All three clinical scenarios investigated in the present in-vitro study are plausible in the presence of proximally deeper dentin levels compared to the enamel: leaving the groove (G) and simply filling it with the luting composite later appears to be pragmatic, simple and, at first glance, easy to solve with the adhesive technique without major effort. Nevertheless, this approach raises the question of whether these areas are at risk of fracture due to their lack of dentin support, e.g. during try-in or in the course of adhesive cementation, which certainly correlates with the extent of undermining, but would not be clinically acceptable in any case.

Another important factor in the course of crack evaluation is the non-adhesive provisional restoration in laboratory-fabricated restorations. Therefore, both CAD/CAM restorations (without temporaries) and laboratory-fabricated restorations (with temporaries and corresponding shortened chewing simulation in this limited time) were included in the present study[

16] . In the course of the present in-vitro study, it was indeed shown that the adhesive re-stabilization with the luting composite was not problematic in terms of marginal quality, but very problematic in terms of crack propagation, and this was much more pronounced in the laboratory-fabricated restorations. The time-limited chewing simulation of the provisionally restored teeth compared to the overall observation period was apparently sufficient to significantly influence the final result of crack propagation, which once again confirms the good clinical potential of chairside CAD/CAM restorations.

Even without the findings from the G groups just described, the authors considered filling the described dentin groove with composite (F) to be an effective approach. In this case, a universal adhesive was bonded in self-etch mode and restored with an established bulk-fill composite. The disadvantage of this approach is traditionally that the enamel margins have to be refinished again for re-exposure, which means that the cervical extension of the preparation is always deeper than in the R groups. It was shown in all groups that this procedure was nevertheless significantly better than the other groups and can therefore also be recommended clinically.

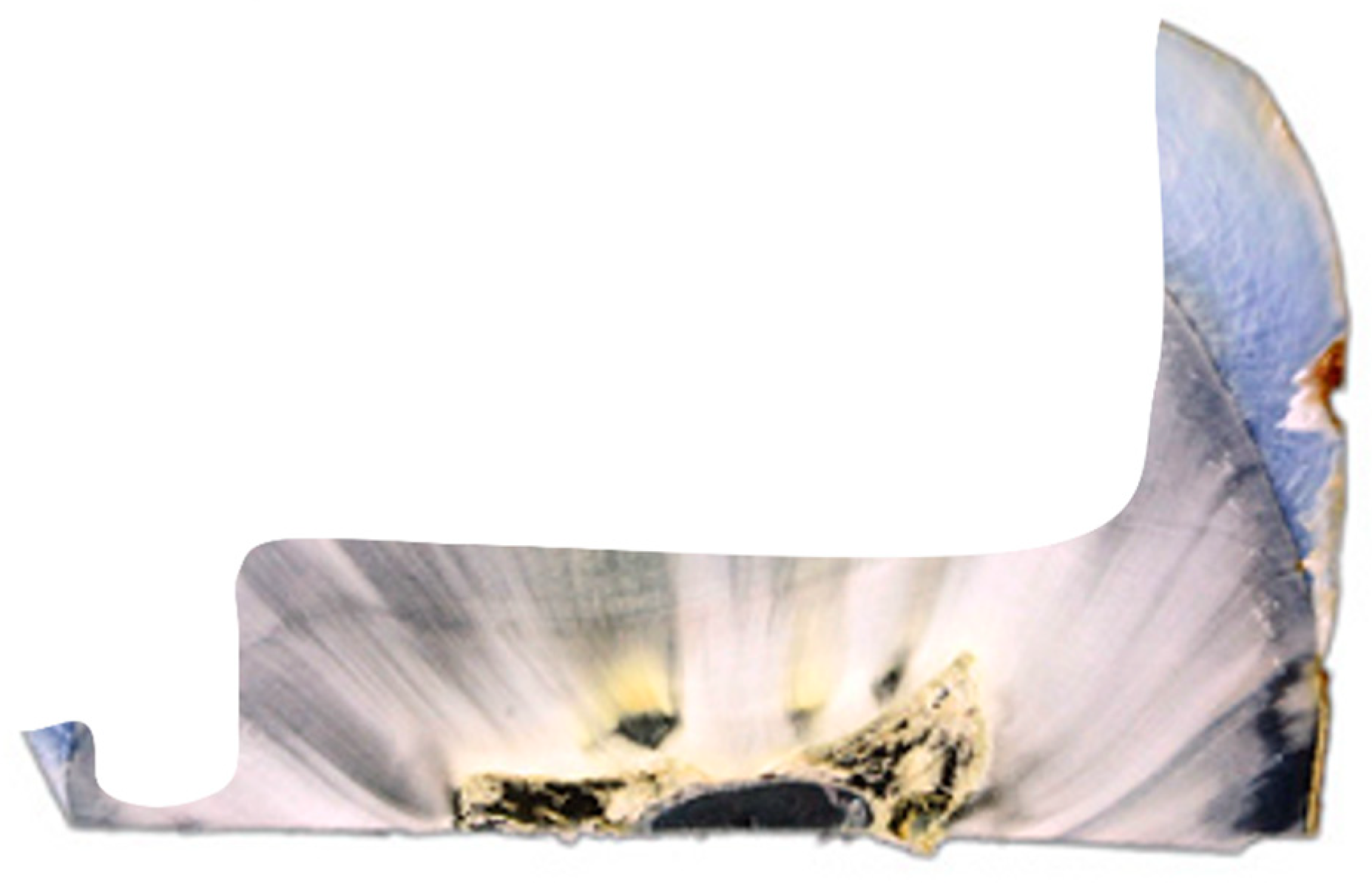

It was generally interesting that marginal gaps in the enamel after TMB were mainly found in the upper third of the proximal box (

Figure 8) and not, as often postulated, in the cervical part. This phenomenon was already described in the 1990s by Mehl et al.[

15] . The increase in cracks over time (before/after TMB) was different; here it was clear that mainly the proximal-cervical portion was affected by significant increases in cracks in the G groups. Finally, it was also interesting to note that both evaluated parameters (gap-free margins and crack increase) were better for the partial crowns than for the inlays, regardless of the cementation mode.

Finally, in the D groups, the undermined enamel clasp was completely removed, which meant that these restorations always ended up in the dentin/root cement. Although this technique would eliminate the cervical enamel cracks and the risk of fracture, the greater susceptibility to hydrolysis and enzymatic degradation in the dentin would be expected to result in more adhesive fatigue per se[

17,

18,

19] . This suspicion was clearly confirmed by the results of the marginal quality examination: the dentin margins were significantly worse than the enamel margins in all groups, even if the measured proportions of gap-free margins in the dentin were not catastrophic (

Figure 9). The D group would only be a recommendable alternative if, for example, parts of the enamel had broken off during fitting or try-in or if the crack increase in the adjacent, non-dentin-supported enamel had been very pronounced. In general, it can be said that fatigue of the composite-dentin bond is not an unsolvable problem today, but that restoration margins should not be placed in the root dentin without necessity if viable alternatives (groups G and F) are available[

18] .

A secondary result of the present study is the standardized evaluation of the effectiveness of different adhesive strategies in adhesive luting, which emerge from the test groups and provide additional, clinically relevant information for daily work. For example, the use of multi-bottle adhesives was a recognized gold standard, not least in the adhesive cementation of ceramics in tooth preservation. This term is derived from thousands of successful in-vitro and in-vivo studies, clearly documented low technique sensitivity and, last but not least, the presence of a hydrophobic bonding agent, which has been and is attested to be less susceptible to hydrolysis[

20,

21] . However, studies from the last decade in particular also show that the class of universal adhesives has caught up considerably in terms of overall adhesive performance and is no longer second-rate in its capacity as a single-bottle bonding agent[

18,

19] . In addition, they solve a major problem in the adhesive cementation of indirect restorations, as in the present study: Compared to the rather highly viscous bonding agents of multi-bottle adhesives, where separate polymerization always entails the risk of not bringing the restoration into the final position during cementation, universal adhesives can easily be blown so thinly that they can be polymerized separately at any time[

23] . This was also shown in the present study, as Heliobond was not polymerized separately with Syntac, the deep margins were also significantly worse compared to the universal adhesive groups despite 240s light-curing. If the adhesive was not polymerized separately, it is possible that the evaluation of the margin still gives a positive picture, as the light source ensures sufficient polymerization at least at the margin. Even if the direct comparison with cervical fillings is somewhat limited, our results confirm the observations of other working groups with advantages for the universal adhesives compared to older multi-bottle adhesives, which have already been confirmed in vivo[

24,

25] .

Based on the available results, the four null hypotheses had to be rejected.

5. Conclusions

When the dentin level lays below the enamel level after proximal excavation, the resulting undermined enamel should not be removed. Instead, undermined enamel should be adhesively built up. Regarding overall performance, the universal adhesive Adhese Universal superseded the former gold standard, the multi-step adhesive Syntac.

References

- Strasding M, Sebestyén-Hüvös E, Studer S, Lehner C, Jung RE, Sailer I. Long-term outcomes of all-ceramic inlays and onlays after a mean observation time of 11 years. Quintessence Int 2020;51:566-576. [CrossRef]

- van Dijken JW, Hasselrot L. A prospective 15-year evaluation of extensive dentin-enamel-bonded pressed ceramic coverages. Dent Mater 2010;26:929-939. [CrossRef]

- Borgia Botto E, Baró R, Borgia Botto JL. Clinical performance of bonded ceramic inlays/onlays: A 5- to 18-year retrospective longitudinal study. Am J Dent 2016;29:187-192.

- Reich SM, Wichmann M, Rinne H, Shortall A. Clinical performance of large, all-ceramic CAD/CAM-generated restorations after three years: a pilot study. J Am Dent Assoc 2004;135:605-612.

- Reiss B. Clinical results of Cerec inlays in a dental practice over a period of 18 years. Int J Comput Dent 2006;9:11-22.

- Collares K, Corrêa MB, Laske M, Kramer E, Reiss B, Moraes RR, Huysmans MC, Opdam NJ. A practice-based research network on the survival of ceramic inlay/onlay restorations. Dent Mater 2016;32:687-694. [CrossRef]

- Castro AS, Maran BM, Gutierrez MF, Chemin K, Mendez-Bauer ML, Bermúdez JP, Reis A, Loguercio AD. Effect of dentin moisture in posterior restorations performed with universal adhesive: A randomized clinical trial. Oper Dent 2022;47:E91-E105. [CrossRef]

- Costa T, Rezende M, Sakamoto A, Bittencourt B, Dalzochio P, Loguercio AD, Reis A. influence of adhesive type and placement technique on postoperative sensitivity in posterior composite restorations. Oper Dent 2017;42:143-154. [CrossRef]

- Peschke A, Blunck U, Roulet JF. Influence of incorrect application of a water-based adhesive system on the marginal adaptation of Class V restorations. Am J Dent 2000;13:239-244.

- Taschner M, Stirnweiss A, Frankenberger R, Kramer N, Galler KM, Maier E. Fourteen years clinical evaluation of leucite-reinforced ceramic inlays luted using two different adhesion strategies. J Dent 2022;123:104210. [CrossRef]

- de Kuijper MCFM, Ong Y, Gerritsen T, Cune MS, Gresnigt MMM. Influence of the ceramic translucency on the relative degree of conversion of a direct composite and dual-curing resin cement through lithium disilicate onlays and endocrowns. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2021;122:104662.

- Ashy LM, Marghalani H, Silikas N. In vitro evaluation of marginal and internal adaptations of ceramic inlay restorations associated with immediate vs delayed dentin sealing techniques. Int J Prosthodont 2020;33:48-55. [CrossRef]

- Ahlers MO, Mörig G, Blunck U, Hajtó J, Pröbster L, Frankenberger R. Guidelines for the preparation of CAD/CAM ceramic inlays and partial crowns. Int J Comput Dent 2009;12:309-325.

- Schwendicke F, Walsh T, Lamont T, Al-Yaseen W, Bjørndal L, Clarkson JE, Fontana M, Gomez Rossi J, Göstemeyer G, Levey C, Müller A, Ricketts D, Robertson M, Santamaria RM, Innes NP. Interventions for treating cavitated or dentine carious lesions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021;7:CD013039.

- Mehl A, Godescha P, Kunzelmann K-H, Hickel R. Marginal gap behavior of composite and ceramic inlays in extended cavities. Dtsch Zahnärztl Z 1996;51:234-238.

- Frankenberger R, Krämer N, Appelt A, Lohbauer U, Naumann M, Roggendorf MJ. Chairside vs. labside ceramic inlays: effect of temporary restoration and adhesive luting on enamel cracks and marginal integrity. Dent Mater 2011;27:892-898. [CrossRef]

- Ma KS, Wang LT, Blatz MB. Efficacy of adhesive strategies for restorative dentistry: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of double-blind randomized controlled trials over 12 months of follow-up. J Prosthodont Res 2023;67:35-44. [CrossRef]

- Carrilho E, Cardoso M, Marques Ferreira M, Marto CM, Paula A, Coelho AS. 10-MDP Based Dental Adhesives: Adhesive Interface Characterization and Adhesive Stability-A Systematic Review. Materials (Basel). 2019 7;12:790. [CrossRef]

- Elkaffas AA, Hamama HHH, Mahmoud SH. Do universal adhesives promote bonding to dentin? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Restor Dent Endod 2018;43:e29. [CrossRef]

- Fuentes MV, Perdigão J, Baracco B, Giráldez I, Ceballos L. Effect of an additional bonding resin on the 5-year performance of a universal adhesive: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig 2023;27:837-848. [CrossRef]

- Ermis RB, Ugurlu M, Ahmed MH, Van Meerbeek B. Universal adhesives benefit from an extra hydrophobic adhesive layer when light cured beforehand. J Adhes Dent 2019;21:179-188. [CrossRef]

- Madrigal EL, Tichy A, Hosaka K, Ikeda M, Nakajima M, Tagami J. The effect of curing mode of dual-cure resin cements on bonding performance of universal adhesives to enamel, dentin and various restorative materials. Dent Mater J 2021;40:446-454. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed MH, Yao C, Van Landuyt K, Peumans M, Van Meerbeek B. Extra bonding layer compensates universal adhesive’s thin film thickness. J Adhes Dent 2020;22:483-501.

- Merle CL, Fortenbacher M, Schneider H, Schmalz G, Challakh N, Park KJ, Häfer M, Ziebolz D, Haak R. Clinical and OCT assessment of application modes of a universal adhesive in a 12-month RCT. J Dent 2022;119:104068. [CrossRef]

- Haak R, Hähnel M, Schneider H, Rosolowski M, Park KJ, Ziebolz D, Häfer M. Clinical and OCT outcomes of a universal adhesive in a randomized clinical trial after 12 months. J Dent 2019;90:103200. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).