Submitted:

19 December 2024

Posted:

20 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Galectins are widely distributed throughout the animal kingdom, from marine sponges to mammals. Galectins are a family of soluble lectins that specifically recognize β-galactoside-containing glycans and are categorized into three subgroups based on the number and function of their carbohydrate recognition domains (CRDs). The interaction of galectins with specific ligands mediates a wide range of biological activities, depending on the cell type, tissue context, expression levels of individual galectin, and receptor involvement. Galectins affect various immune cell processes through both intracellular and extracellular mechanisms and play roles in processes, such as apoptosis, angiogenesis, and fibrosis. Their importance has increased in recent years because they are recognized as biomarkers, therapeutic agents, and drug targets, with many other applications in conditions such as cardiovascular diseases and cancer. However, little is known about the involvement of galectins in liver disease. Here, we review the functions of various galectins and evaluate their roles in liver diseases.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Galectin Family

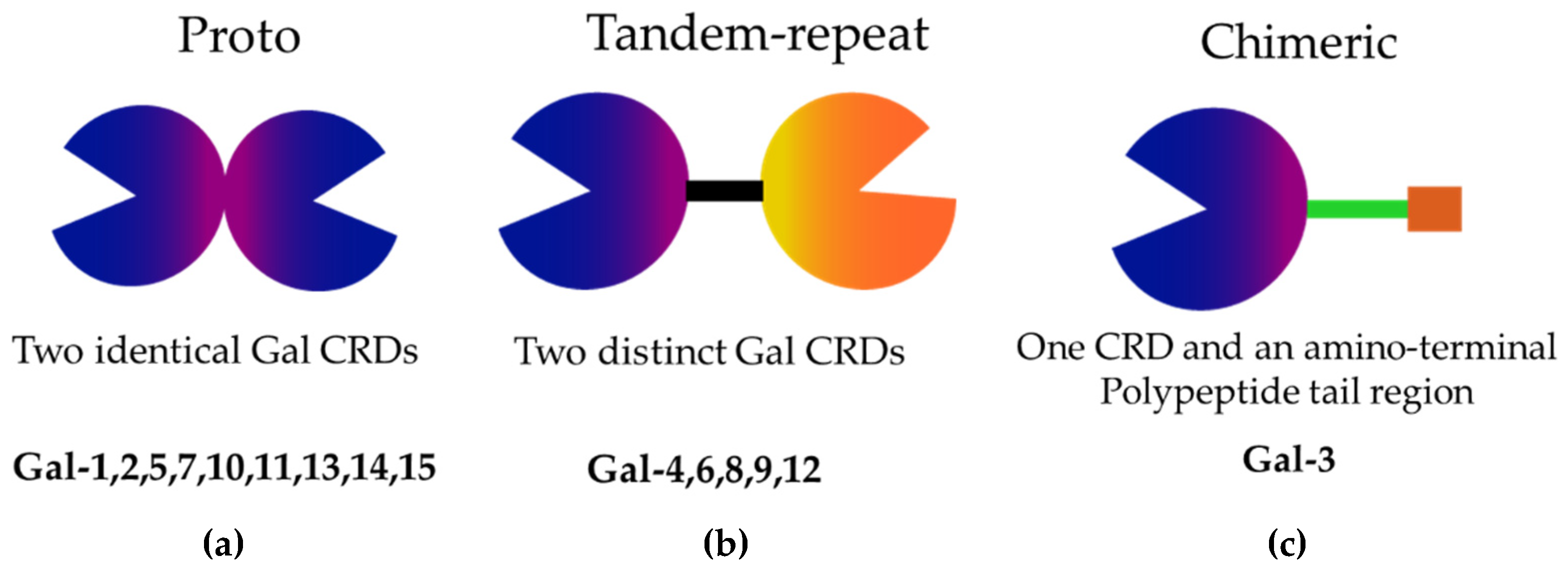

2.1. Structure of Galectins

2.2. Functions of Galectin Structures

3. Functions of Galectins

3.1. Regulation of Immune Response

3.2. Apoptosis

3.3. Angiogenesis

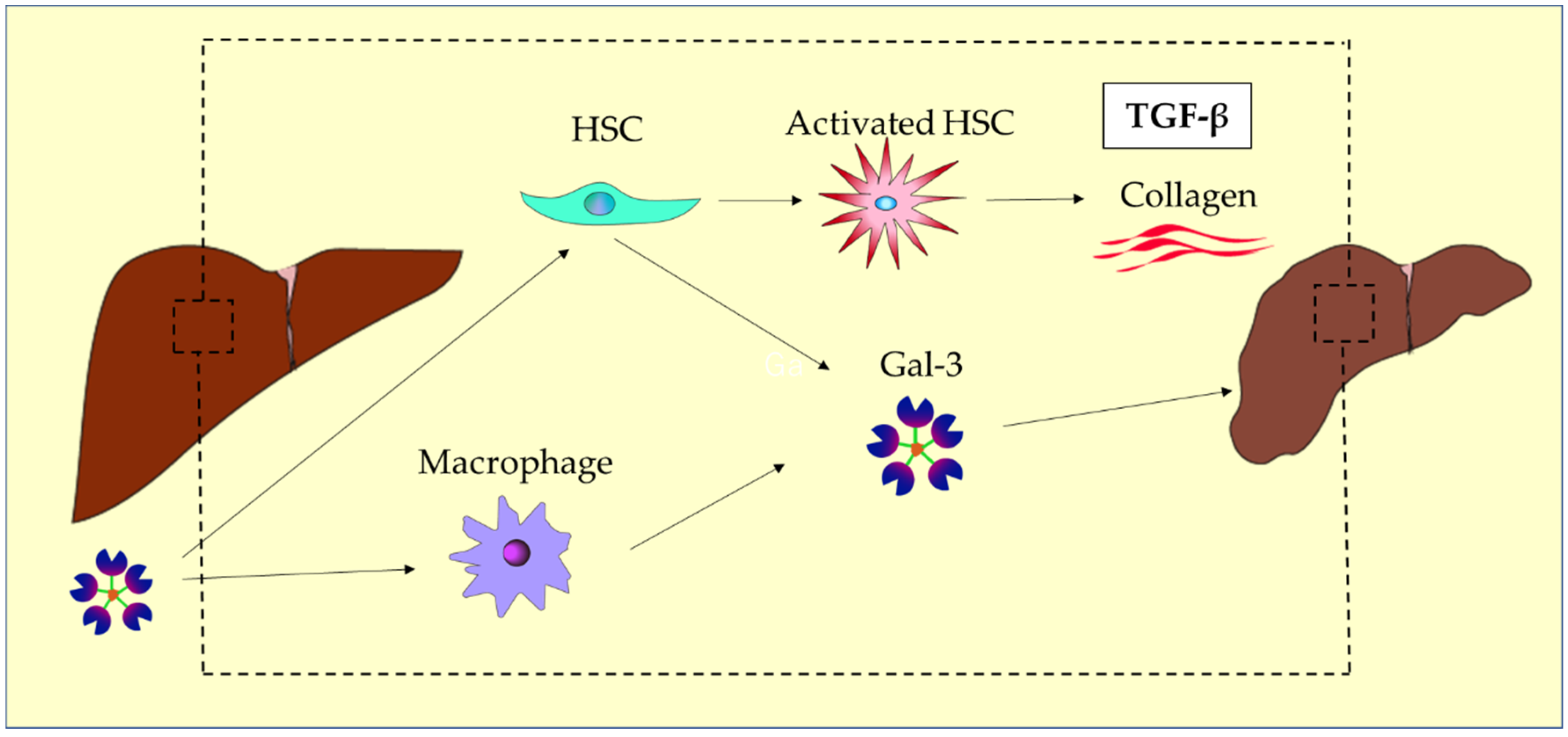

3.4. Fibrosis

4. Galectins and Medicine

4.1. Galectins as Disease Biomarkers

4.2. Application as a Therapeutic Target

5. Expression Patterns and Roles of Galectins in the Liver

6. Liver Fibrosis

7. Galectins and the Gut-Liver Axis

8. Galectins and Liver Diseases

8.1. Chronic Hepatitis B (CHB)

8.2. Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Infection

8.3. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease/Steatohepatitis (MASLD/MASH)

8.4. Alcohol Associated Liver Disease (ALD)

8.5. Autoimmune Hepatitis (AIH)

8.6. Primary Biliary Cholangitis (PBC)

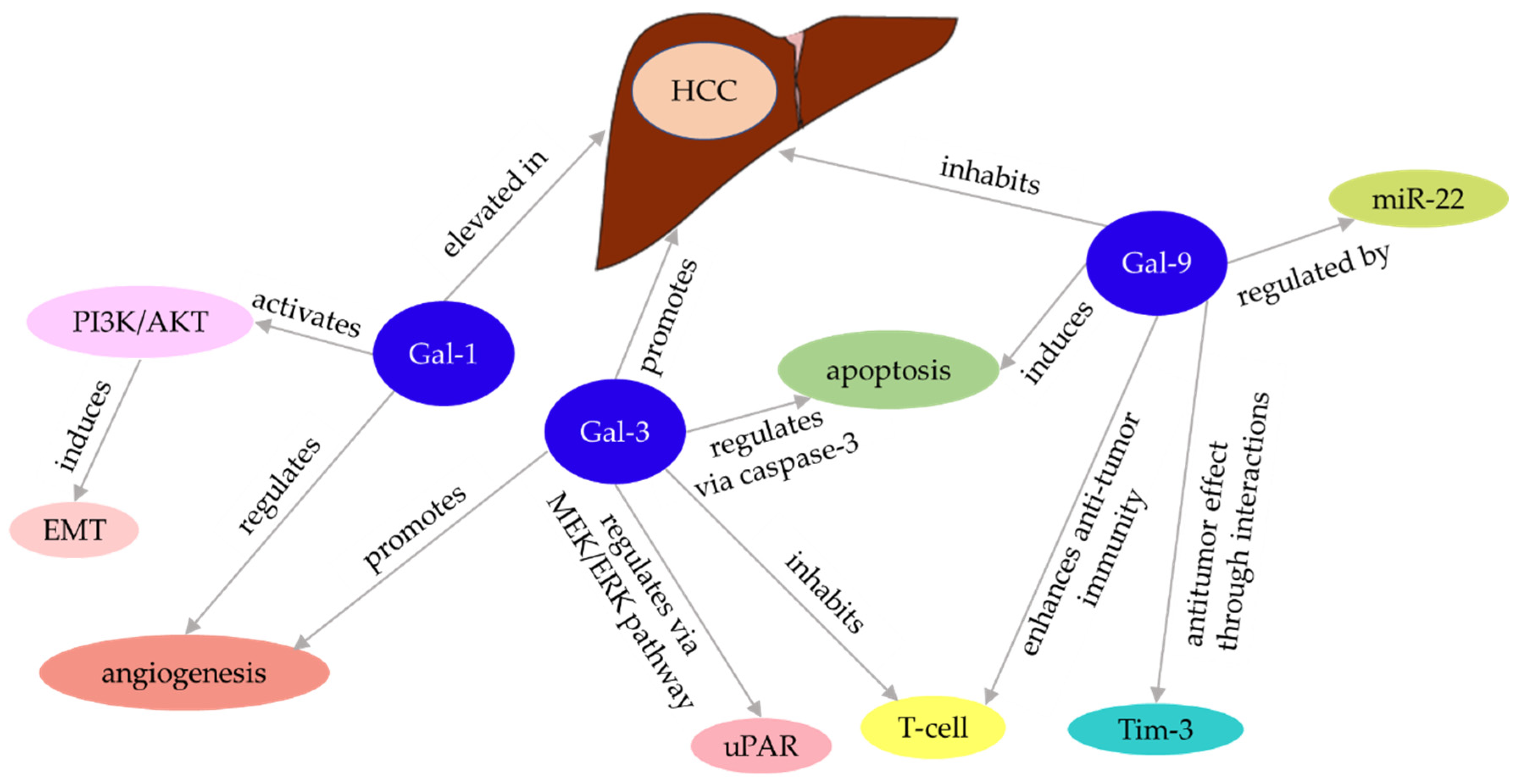

8.7. Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Galectins

9. Application to Liver Disease Diagnosis

9.1. Liver Fibrosis Screening

9.2. Early Detection and Prognosis of HCC

9.3. Early Diagnosis of Acute Liver Damage

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barondes, S.H.; Castronovo, V.; Cooper, D.N.W.; Cummings, R.D.; Drickamer, K.; Felzi, T.; Gitt, M.A.; Hirabayashi, J.; Hughes, C.; Kasai, K. ichi; et al. Galectins: A Family of Animal Beta-Galactoside-Binding Lectins. Cell 1994, 76, 597–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharon, N.; Lis, H. Lectins as Cell Recognition Molecules. Science 1989, 246, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, J.D.; Baum, L.G. Ah, Sweet Mystery of Death! Galectins and Control of Cell Fate. Glycobiology 2002, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuster, M.M.; Esko, J.D. The Sweet and Sour of Cancer: Glycans as Novel Therapeutic Targets. Nature Reviews Cancer 2005 5:7 2005, 5, 526–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolic, V.N.; Popadic, V.; Jankovic, S.M.; Govedarović, N.; Vujić, S.; Andjelković, J.; Stosic, L.S.; Stevanović, N.Č.; Zdravkovic, M.; Todorovic, Z. The Silent Predictors: Exploring Galectin-3 and Irisin’s Tale in Severe COVID-19. BMC Res Notes 2024, 17, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovich, G.A.; Croci, D.O. Regulatory Circuits Mediated by Lectin-Glycan Interactions in Autoimmunity and Cancer. Immunity 2012, 36, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijssen, V.L. Galectins in Endothelial Cell Biology and Angiogenesis: The Basics. Biomolecules 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, R.; Li, W.; Wang, J.; Xie, J.; Weng, X.; Yang, Y.; Shi, X. Association Between Serum Galectin-3 and Parkinson’s Disease: A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. Brain Behav 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishita, A.; Oura, K.; Tadokoro, T.; Shi, T.; Fujita, K.; Tani, J.; Atsukawa, M.; Masaki, T. Galectin-9 in Gastroenterological Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, R.; Gorek, L.S. Intracellular Galectin Interactions in Health and Disease. Semin Immunopathol 2024, 46, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, R.D.; Liu, F.-T.; Rabinovich, G.A.; Stowell, S.R.; Vasta, G.R. Galectins. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.N.W. Galectinomics: Finding Themes in Complexity. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 2002, 1572, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovich, G.A.; Toscano, M.A. Turning “sweet” on Immunity: Galectin–Glycan Interactions in Immune Tolerance and Inflammation. Nature Reviews Immunology 2009 9:5 2009, 9, 338–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sygitowicz, G.; Maciejak-Jastrzębska, A.; Sitkiewicz, D. The Diagnostic and Therapeutic Potential of Galectin-3 in Cardiovascular Diseases. Biomolecules 2022, Vol. 12, Page 46 2021, 12, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johannes, L.; Jacob, R.; Leffler, H. Galectins at a Glance. J Cell Sci 2018, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabi, I.R.; Shankar, J.; Dennis, J.W. The Galectin Lattice at a Glance. J Cell Sci 2015, 128, 2213–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthahar, N.; Meijers, W.C.; Silljé, H.H.W.; Ho, J.E.; Liu, F.T.; de Boer, R.A. Galectin-3 Activation and Inhibition in Heart Failure and Cardiovascular Disease: An Update. Theranostics 2018, 8, 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laaf, D.; Bojarová, P.; Elling, L.; Křen, V. Galectin-Carbohydrate Interactions in Biomedicine and Biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol 2019, 37, 402–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannes, L.; Jacob, R.; Leffler, H. Galectins at a Glance. J Cell Sci 2018, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.Y.; Rabinovich, G.A.; Liu, F.T. Galectins: Structure, Function and Therapeutic Potential. Expert Rev Mol Med 2008, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminker, J.D.; Timoshenko, A. V. Expression, Regulation, and Functions of the Galectin-16 Gene in Human Cells and Tissues. Biomolecules 2021, Vol. 11, Page 1909 2021, 11, 1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannes, L.; Jacob, R.; Leffler, H. Galectins at a Glance. J Cell Sci 2018, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabi, I.R.; Shankar, J.; Dennis, J.W. The Galectin Lattice at a Glance. J Cell Sci 2015, 128, 2213–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.Y.; Rabinovich, G.A.; Liu, F.T. Galectins: Structure, Function and Therapeutic Potential. Expert Rev Mol Med 2008, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.T.; Patterson, R.J.; Wang, J.L. Intracellular Functions of Galectins. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj 2002, 1572, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.Y.; Weng, I.C.; Hong, M.H.; Liu, F.T. Galectins as Bacterial Sensors in the Host Innate Response. Curr Opin Microbiol 2014, 17, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nio-Kobayashi, J. Tissue- and Cell-Specific Localization of Galectins, β-Galactose-Binding Animal Lectins, and Their Potential Functions in Health and Disease. Anat Sci Int 2017, 92, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.Q.; Guo, X.L. The Role of Galectin-4 in Physiology and Diseases. Protein Cell 2016, 7, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovich, G.A.; Baum, L.G.; Tinari, N.; Paganelli, R.; Natoli, C.; Liu, F.T.; Iacobelli, S. Galectins and Their Ligands: Amplifiers, Silencers or Tuners of the Inflammatory Response? Trends Immunol 2002, 23, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newlaczyl, A.U.; Yu, L.G. Galectin-3--a Jack-of-All-Trades in Cancer. Cancer Lett 2011, 313, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannes, L.; Jacob, R.; Leffler, H. Galectins at a Glance. J Cell Sci 2018, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, I.R.; Shankar, J.; Dennis, J.W. The Galectin Lattice at a Glance. J Cell Sci 2015, 128, 2213–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiemann, S.; Baum, L.G. Galectins and Immune Responses-Just How Do They Do Those Things They Do? Annu Rev Immunol 2016, 34, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasta, G.R.; Ahmed, H.; Nita-Lazar, M.; Banerjee, A.; Pasek, M.; Shridhar, S.; Guha, P.; Fernández-Robledo, J.A. Galectins as Self/Non-Self Recognition Receptors in Innate and Adaptive Immunity: An Unresolved Paradox. Front Immunol 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilarregui, J.M.; Croci, D.O.; Bianco, G.A.; Toscano, M.A.; Salatino, M.; Vermeulen, M.E.; Geffner, J.R.; Rabinovich, G.A. Tolerogenic Signals Delivered by Dendritic Cells to T Cells through a Galectin-1-Driven Immunoregulatory Circuit Involving Interleukin 27 and Interleukin 10. Nat Immunol 2009, 10, 981–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, N.I.; Baudou, F.G.; Scheidegger, M.A.; Dalotto-Moreno, T.; Rabinovich, G.A. Do Galectins Serve as Soluble Ligands for Immune Checkpoint Receptors? J Immunother Cancer 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrad, N.A.F.; Shaker, O.G.; Elbanna, R.M.H.; AbdelKawy, M. “Outcome of Non-Surgical Periodontal Treatment on Gal-1 and Gal-3 GCF Levels in Periodontitis Patients: A Case-Control Study. ” Clin Oral Investig 2024, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias-Baruffi, M.; Stowell, S.R.; Song, S.C.; Arthur, C.M.; Cho, M.; Rodrigues, L.C.; Montes, M.A.B.; Rossi, M.A.; James, J.A.; McEver, R.P.; et al. Differential Expression of Immunomodulatory Galectin-1 in Peripheral Leukocytes and Adult Tissues and Its Cytosolic Organization in Striated Muscle. Glycobiology 2010, 20, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.T.; Stowell, S.R. The Role of Galectins in Immunity and Infection. Nat Rev Immunol 2023, 23, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerliani, J.P.; Stowell, S.R.; Mascanfroni, I.D.; Arthur, C.M.; Cummings, R.D.; Rabinovich, G.A. Expanding the Universe of Cytokines and Pattern Recognition Receptors: Galectins and Glycans in Innate Immunity. J Clin Immunol 2011, 31, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akazawa, C.; Nakamura, Y.; Sango, K.; Horie, H.; Kohsaka, S. Distribution of the Galectin-1 MRNA in the Rat Nervous System: Its Transient Upregulation in Rat Facial Motor Neurons after Facial Nerve Axotomy. Neuroscience 2004, 125, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almkvist, J.; Karlsson, A. Galectins as Inflammatory Mediators. Glycoconj J 2002, 19, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, R.; Yang, M.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Yang, L.; Lei, B. The Protective Effects of VVN001 on LPS-Induced Inflammatory Responses in Human RPE Cells and in a Mouse Model of EIU. Inflammation 2021, 44, 780–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colnot, C.; Sidhu, S.S.; Balmain, N.; Poirier, F. Uncoupling of Chondrocyte Death and Vascular Invasion in Mouse Galectin 3 Null Mutant Bones. Dev Biol 2001, 229, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, Q.; Hughes, R.C. Galectin-3 Expression and Effects on Cyst Enlargement and Tubulogenesis in Kidney Epithelial MDCK Cells Cultured in Three-Dimensional Matrices in Vitro. J Cell Sci 1995, 108, 2791–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guévremont, M.; Martel-Pelletier, J.; Boileau, C.; Liu, F.T.; Richard, M.; Fernandes, J.C.; Pelletier, J.P.; Reboul, P. Galectin-3 Surface Expression on Human Adult Chondrocytes: A Potential Substrate for Collagenase-3. Ann Rheum Dis 2004, 63, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinchmann, M.F.; Patel, D.M.; Iversen, M.H. The Role of Galectins as Modulators of Metabolism and Inflammation. Mediators Inflamm 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes, M.B.; Molinero, L.L.; Toscano, M.A.; Ilarregui, J.M.; Rubinstein, N.; Fainboim, L.; Zwirner, N.W.; Rabinovich, G.A. Regulated Expression of Galectin-1 during T-Cell Activation Involves Lck and Fyn Kinases and Signaling through MEK1/ERK, P38 MAP Kinase and P70S6 Kinase. Mol Cell Biochem 2004, 267, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, M.A.; Bianco, G.A.; Ilarregui, J.M.; Croci, D.O.; Correale, J.; Hernandez, J.D.; Zwirner, N.W.; Poirier, F.; Riley, E.M.; Baum, L.G.; et al. Differential Glycosylation of TH1, TH2 and TH-17 Effector Cells Selectively Regulates Susceptibility to Cell Death. Nat Immunol 2007, 8, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiemann, S.; Baum, L.G. Galectins and Immune Responses-Just How Do They Do Those Things They Do? Annu Rev Immunol 2016, 34, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radosavljevic, G.; Volarevic, V.; Jovanovic, I.; Milovanovic, M.; Pejnovic, N.; Arsenijevic, N.; Hsu, D.K.; Lukic, M.L. The Roles of Galectin-3 in Autoimmunity and Tumor Progression. Immunol Res 2012, 52, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volarevic, V.; Milovanovic, M.; Ljujic, B.; Pejnovic, N.; Arsenijevic, N.; Nilsson, U.; Leffler, H.; Lukic, M.L. Galectin-3 Deficiency Prevents Concanavalin A-Induced Hepatitis in Mice. Hepatology 2012, 55, 1954–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breuilh, L.; Vanhoutte, F.; Fontaine, J.; Van Stijn, C.M.W.; Tillie-Leblond, I.; Capron, M.; Faveeuw, C.; Jouault, T.; Van Die, I.; Gosset, P.; et al. Galectin-3 Modulates Immune and Inflammatory Responses during Helminthic Infection: Impact of Galectin-3 Deficiency on the Functions of Dendritic Cells. Infect Immun 2007, 75, 5148–5157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, F.L.; Gatto, M.; Bassi, N.; Luisetto, R.; Ghirardello, A.; Punzi, L.; Doria, A. Galectin-3 in Autoimmunity and Autoimmune Diseases. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2015, 240, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srejovic, I.M.; Lukic, M.L. Galectin-3 in T Cell-Mediated Immunopathology and Autoimmunity. Immunol Lett 2021, 233, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhirapong, A.; Lleo, A.; Leung, P.; Gershwin, M.E.; Liu, F.T. The Immunological Potential of Galectin-1 and -3. Autoimmun Rev 2009, 8, 360–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, D.K.; Chernyavsky, A.I.; Chen, H.Y.; Yu, L.; Grando, S.A.; Liu, F.T. Endogenous Galectin-3 Is Localized in Membrane Lipid Rafts and Regulates Migration of Dendritic Cells. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2009, 129, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilson, R.C.; Gunasinghe, S.D.; Johannes, L.; Gaus, K. Galectin-3 Modulation of T-Cell Activation: Mechanisms of Membrane Remodelling. Prog Lipid Res 2019, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedeno-Laurent, F.; Barthel, S.R.; Opperman, M.J.; Lee, D.M.; Clark, R.A.; Dimitroff, C.J. Development of a Nascent Galectin-1 Chimeric Molecule for Studying the Role of Leukocyte Galectin-1 Ligands and Immune Disease Modulation. The Journal of Immunology 2010, 185, 4659–4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stowell, S.R.; Karmakar, S.; Stowell, C.J.; Dias-Baruffi, M.; McEver, R.P.; Cummings, R.D. Human Galectin-1, -2, and -4 Induce Surface Exposure of Phosphatidylserine in Activated Human Neutrophils but Not in Activated T Cells. Blood 2007, 109, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shil, R.K.; Mohammed, N.B.B.; Dimitroff, C.J. Galectin-9 - Ligand Axis: An Emerging Therapeutic Target for Multiple Myeloma. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1469794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.-Y.; Nakagawa, R.; Itoh, A.; Murakami, H.; Kashio, Y.; Abe, H.; Katoh, S.; Kontani, K.; Kihara, M.; Zhang, S.-L.; et al. Galectin-9 Induces Maturation of Human Monocyte-Derived Dendritic Cells. J Immunol 2005, 175, 2974–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, R.; Hirashima, M.; Kita, H.; Gleich, G.J. Biological Activities of Ecalectin: A Novel Eosinophil-Activating Factor. J Immunol 2002, 168, 1961–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, B.S.; Arthur, C.M.; Evavold, B.; Roback, E.; Kamili, N.A.; Stowell, C.S.; Vallecillo-Zúniga, M.L.; Van Ry, P.M.; Dias-Baruffi, M.; Cummings, R.D.; et al. The Sweet-Side of Leukocytes: Galectins as Master Regulators of Neutrophil Function. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuura, A.; Tsukada, J.; Mizobe, T.; Higashi, T.; Mouri, F.; Tanikawa, R.; Yamauchi, A.; Hirashima, M.; Tanaka, Y. Intracellular Galectin-9 Activates Inflammatory Cytokines in Monocytes. Genes Cells 2009, 14, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikawa, T.; Saita, N.; Oomizu, S.; Ueno, M.; Matsukawa, A.; Katoh, S.; Kojima, K.; Nagahara, K.; Miyake, M.; Yamauchi, A.; et al. Galectin-9 Expands Immunosuppressive Macrophages to Ameliorate T-Cell-Mediated Lung Inflammation. Eur J Immunol 2010, 40, 548–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shil, R.K.; Mohammed, N.B.B.; Dimitroff, C.J. Galectin-9 - Ligand Axis: An Emerging Therapeutic Target for Multiple Myeloma. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1469794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J.F.R.; Wyllie, A.H.; Currie, A.R. Apoptosis: A Basic Biological Phenomenon with Wide-Ranging Implications in Tissue Kinetics. Br J Cancer 1972, 26, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerasinghe, P.; Buja, L.M. Oncosis: An Important Non-Apoptotic Mode of Cell Death. Exp Mol Pathol 2012, 93, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzi, L.; Vitale, I.; Abrams, J.M.; Alnemri, E.S.; Baehrecke, E.H.; Blagosklonny, M. V.; Dawson, T.M.; Dawson, V.L.; El-Deiry, W.S.; Fulda, S.; et al. Molecular Definitions of Cell Death Subroutines: Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2012. Cell Death Differ 2012, 19, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.N.; Ha, S.G.; Greenberg, Y.G.; Rao, A.; Bastan, I.; Blidner, A.G.; Rao, S.P.; Rabinovich, G.A.; Sriramarao, P. Regulation of Eosinophilia and Allergic Airway Inflammation by the Glycan-Binding Protein Galectin-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, E4837–E4846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novák, J.; Kriston-Pál, É.; Czibula, Á.; Deák, M.; Kovács, L.; Monostori, É.; Fajka-Boja, R. GM1 Controlled Lateral Segregation of Tyrosine Kinase Lck Predispose T-Cells to Cell-Derived Galectin-1-Induced Apoptosis. Mol Immunol 2014, 57, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez-Huergo, S.P.; Blidner, A.G.; Rabinovich, G.A. Galectins: Emerging Regulatory Checkpoints Linking Tumor Immunity and Angiogenesis. Curr Opin Immunol 2017, 45, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez-Huergo, S.P.; Blidner, A.G.; Rabinovich, G.A. Galectins: Emerging Regulatory Checkpoints Linking Tumor Immunity and Angiogenesis. Curr Opin Immunol 2017, 45, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croci, D.O.; Cerliani, J.P.; Dalotto-Moreno, T.; Méndez-Huergo, S.P.; Mascanfroni, I.D.; Dergan-Dylon, S.; Toscano, M.A.; Caramelo, J.J.; García-Vallejo, J.J.; Ouyang, J.; et al. Glycosylation-Dependent Lectin-Receptor Interactions Preserve Angiogenesis in Anti-VEGF Refractory Tumors. Cell 2014, 156, 744–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowska, A.I.; Liu, F.T.; Panjwani, N. Galectin-3 Is an Important Mediator of VEGF- and BFGF-Mediated Angiogenic Response. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2010, 207, 1981–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, C.M. aria L.; Andrade, L.N. ogueira S.; Teixeira, V.R.; Costa, F.F.; Melo, C.M. orais; dos Santos, S.N. ascimento; Nonogaki, S.; Liu, F.T.; Bernardes, E.S. oares; Camargo, A.A. ranha; et al. Galectin-3 Disruption Impaired Tumoral Angiogenesis by Reducing VEGF Secretion from TGFβ1-Induced Macrophages. Cancer Med 2014, 3, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, V.M.C.; Nugnes, L.G.; Colombo, L.L.; Troncoso, M.F.; Fernández, M.M.; Malchiodi, E.L.; Frahm, I.; Croci, D.O.; Compagno, D.; Rabinovich, G.A.; et al. Modulation of Endothelial Cell Migration and Angiogenesis: A Novel Function for the “Tandem-Repeat” Lectin Galectin-8. The FASEB Journal 2011, 25, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, N.C.; Mackinnon, A.C.; Farnworth, S.L.; Poirier, F.; Russo, F.P.; Iredale, J.P.; Haslett, C.; Simpson, K.J.; Sethi, T. Galectin-3 Regulates Myofibroblast Activation and Hepatic Fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 5060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S.L. Molecular Regulation of Hepatic Fibrosis, an Integrated Cellular Response to Tissue Injury. J Biol Chem 2000, 275, 2247–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiariotti, L.; Salvatore, P.; Frunzio, R.; Bruni, C.B. Galectin Genes: Regulation of Expression. Glycoconj J 2002, 19, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayes-Genis, A.; De Antonio, M.; Vila, J.; Peñafiel, J.; Galán, A.; Barallat, J.; Zamora, E.; Urrutia, A.; Lupón, J. Head-to-Head Comparison of 2 Myocardial Fibrosis Biomarkers for Long-Term Heart Failure Risk Stratification: ST2 versus Galectin-3. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014, 63, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Boer, R.A.; Daniels, L.B.; Maisel, A.S.; Januzzi, J.L. State of the Art: Newer Biomarkers in Heart Failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2015, 17, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, R. V.; Januzzi, J.L. Soluble ST2 and Galectin-3 in Heart Failure. Clin Lab Med 2014, 34, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallick, A.; Januzzi, J.L. Biomarkers in Acute Heart Failure. Revista Española de Cardiología (English Edition) 2015, 68, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettersten, N.; Maisel, A.S. Biomarkers for Heart Failure: An Update for Practitioners of Internal Medicine. American Journal of Medicine 2016, 129, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepoi, M.-R.; Duca, S.T.; Chetran, A.; Costache, A.D.; Spiridon, M.R.; Afrăsânie, I.; Leancă, S.A.; Dmour, B.-A.; Matei, I.T.; Miftode, R.S.; et al. Chronic Kidney Disease Associated with Ischemic Heart Disease: To What Extent Do Biomarkers Help? Life (Basel) 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehlken, C.; Suthahar, N.; Meijers, W.C.; de Boer, R.A. Galectin-3 in Heart Failure: An Update of the Last 3 Years. Heart Fail Clin 2018, 14, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, M.L.; Ang, X.; Yap, K.Y.; Ng, J.J.; Goh, E.C.H.; Khoo, B.B.J.; Richards, A.M.; Drum, C.L. Novel Oxidative Stress Biomarkers with Risk Prognosis Values in Heart Failure. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Făgărășan, A.; Săsăran, M.; Gozar, L.; Crauciuc, A.; Bănescu, C. The Role of Galectin-3 in Predicting Congenital Heart Disease Outcome: A Review of the Literature. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, E.I.; Szymanski, J.J.; Hock, K.G.; Geltman, E.M.; Scott, M.G. Short- and Long-Term Biologic Variability of Galectin-3 and Other Cardiac Biomarkers in Patients with Stable Heart Failure and Healthy Adults. Clin Chem 2016, 62, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, I.S.; Rector, T.S.; Kuskowski, M.; Adourian, A.; Muntendam, P.; Cohn, J.N. Baseline and Serial Measurements of Galectin-3 in Patients with Heart Failure: Relationship to Prognosis and Effect of Treatment with Valsartan in the Val-HeFT. Eur J Heart Fail 2013, 15, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaborska, B.; Sikora-Frąc, M.; Smarż, K.; Pilichowska-Paszkiet, E.; Budaj, A.; Sitkiewicz, D.; Sygitowicz, G. The Role of Galectin-3 in Heart Failure-The Diagnostic, Prognostic and Therapeutic Potential-Where Do We Stand? Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, J.; Ota, K.; Kumar, A.; Wallner, E.I.; Kanwar, Y.S. Developmental Regulation, Expression, and Apoptotic Potential of Galectin-9, a Beta-Galactoside Binding Lectin. J Clin Invest 1997, 99, 2452–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rydlova, M.; Ludvikova, M.; Stankova, I. Potential Diagnostic Markers in Nodular Lesions of the Thyroid Gland: An Immunohistochemical Study. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 2008, 152, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balan, V.; Nangia-Makker, P.; Raz, A. Galectins as Cancer Biomarkers. Cancers (Basel) 2010, 2, 592–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, M.P.V.; Nangia-Makker, P.; Tait, L.; Miller, F.; Raz, A. Alterations in Galectin-3 Expression and Distribution Correlate with Breast Cancer Progression: Functional Analysis of Galectin-3 in Breast Epithelial-Endothelial Interactions. Am J Pathol 2004, 165, 1931–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nangia-Makker, P.; Hogan, V.; Raz, A. Galectin-3 and Cancer Stemness. Glycobiology 2018, 28, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Song, S.; Li, Y.; Dhar, S.S.; Jin, J.; Yoshimura, K.; Yao, X.; Wang, R.; Scott, A.W.; Pizzi, M.P.; et al. Galectin-3 Cooperates with CD47 to Suppress Phagocytosis and T-Cell Immunity in Gastric Cancer Peritoneal Metastases. Cancer Res 2023, 83, 3726–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çay, T. Immunhistochemical Expression of Galectin-3 in Cancer: A Review of the Literature. Turk Patoloji Dergisi/Turkish Journal of Pathology 2012, 28, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, V.G.; Mourad-Zeidan, A.A.; Melnikova, V.; Johnson, M.M.; Lopez, A.; Diwan, A.H.; Lazar, A.J.F.; Shen, S.S.; Zhang, P.S.; Reed, J.A.; et al. Galectin-3 Expression Is Associated with Tumor Progression and Pattern of Sun Exposure in Melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 2006, 12, 6709–6715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchida, A.; Hachisu, K.; Mizuno, M.; Takada, Y.; Ideo, H. High Expression of B3GALT5 Suppresses the Galectin-4-Mediated Peritoneal Dissemination of Poorly Differentiated Gastric Cancer Cells. Glycobiology 2024, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hachisu, K.; Tsuchida, A.; Takada, Y.; Mizuno, M.; Ideo, H. Galectin-4 Is Involved in the Structural Changes of Glycosphingolipid Glycans in Poorly Differentiated Gastric Cancer Cells with High Metastatic Potential. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 12305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ideo, H.; Tsuchida, A.; Takada, Y.; Kinoshita, J.; Inaki, N.; Minamoto, T. Suppression of Galectin-4 Attenuates Peritoneal Metastasis of Poorly Differentiated Gastric Cancer Cells. Gastric Cancer 2023, 26, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lișcu, H.D.; Verga, N.; Atasiei, D.I.; Badiu, D.C.; Dumitru, A.V.; Ultimescu, F.; Pavel, C.; Stefan, R.E.; Manole, D.C.; Ionescu, A.I. Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer: Actual and Future Perspectives. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, Vol. 25, Page 11535 2024, 25, 11535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çay, T. Immunhistochemical Expression of Galectin-3 in Cancer: A Review of the Literature. Turk Patoloji Dergisi/Turkish Journal of Pathology 2012, 28, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Tang, J. wu; Owusu, L.; Sun, M.Z.; Wu, J.; Zhang, J. Galectin-3 in Cancer. Clin Chim Acta 2014, 431, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laderach, D.J.; Compagno, D. Inhibition of Galectins in Cancer: Biological Challenges for Their Clinical Application. Front Immunol 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijssen, V.L.J.L. Vascular Galectins in Tumor Angiogenesis and Cancer Immunity. Semin Immunopathol 2024, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astorgues-Xerri, L.; Riveiro, M.E.; Tijeras-Raballand, A.; Serova, M.; Neuzillet, C.; Albert, S.; Raymond, E.; Faivre, S. Unraveling Galectin-1 as a Novel Therapeutic Target for Cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 2014, 40, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laderach, D.J.; Gentilini, L.D.; Giribaldi, L.; Delgado, V.C.; Nugnes, L.; Croci, D.O.; Al Nakouzi, N.; Sacca, P.; Casas, G.; Mazza, O.; et al. A Unique Galectin Signature in Human Prostate Cancer Progression Suggests Galectin-1 as a Key Target for Treatment of Advanced Disease. Cancer Res 2013, 73, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijssen, V.L.; Barkan, B.; Shoji, H.; Aries, I.M.; Mathieu, V.; Deltour, L.; Hackeng, T.M.; Kiss, R.; Kloog, Y.; Poirier, F.; et al. Tumor Cells Secrete Galectin-1 to Enhance Endothelial Cell Activity. Cancer Res 2010, 70, 6216–6224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thijssen, V.L.J.L.; Postel, R.; Brandwijk, R.J.M.G.E.; Dings, R.P.M.; Nesmelova, I.; Satijn, S.; Verhofstad, N.; Nakabeppu, Y.; Baum, L.G.; Bakkers, J.; et al. Galectin-1 Is Essential in Tumor Angiogenesis and Is a Target for Antiangiogenesis Therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 15975–15980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez-Huergo, S.P.; Blidner, A.G.; Rabinovich, G.A. Galectins: Emerging Regulatory Checkpoints Linking Tumor Immunity and Angiogenesis. Curr Opin Immunol 2017, 45, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerliani, J.P.; Dalotto-Moreno, T.; Compagno, D.; Dergan-Dylon, L.S.; Laderach, D.J.; Gentilini, L.; Croci, D.O.; Méndez-Huergo, S.P.; Toscano, M.A.; Salatino, M.; et al. Study of Galectins in Tumor Immunity: Strategies and Methods. Methods in Molecular Biology 2015, 1207, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovich, G.A.; Toscano, M.A. Turning “sweet” on Immunity: Galectin-Glycan Interactions in Immune Tolerance and Inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2009, 9, 338–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.H.; Chen, Y.L.; Lee, K.H.; Chang, C.C.; Cheng, T.M.; Wu, S.Y.; Tu, C.C.; Tsui, W.L. Glycosylation-Dependent Galectin-1/Neuropilin-1 Interactions Promote Liver Fibrosis through Activation of TGF-β- and PDGF-like Signals in Hepatic Stellate Cells. Scientific Reports 2017 7:1 2017, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potikha, T.; Ella, E.; Cerliani, J.P.; Mizrahi, L.; Pappo, O.; Rabinovich, G.A.; Galun, E.; Goldenberg, D.S. Galectin-1 Is Essential for Efficient Liver Regeneration Following Hepatectomy. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 31738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lv, F.; Dai, C.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, C.; Fang, M.; Xu, Y. Activation of Galectin-3 (LGALS3) Transcription by Injurious Stimuli in the Liver Is Commonly Mediated by BRG1. Front Cell Dev Biol 2019, 7, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, N.; Kawada, N.; Seki, S.; Arakawa, T.; Ikeda, K.; Iwao, H.; Okuyama, H.; Hirabayashi, J.; Kasai, K. ichi; Yoshizato, K. Stimulation of Proliferation of Rat Hepatic Stellate Cells by Galectin-1 and Galectin-3 through Different Intracellular Signaling Pathways. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 18938–18944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden-Mason, L.; Rosen, H.R. Galectin-9: Diverse Roles in Hepatic Immune Homeostasis and Inflammation. Hepatology 2017, 66, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J.; You, S.; Chen, W.; Yang, X.; Xv, Y.; Zhu, B. Galectin-9 as a New Biomarker of Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure. Scientific Reports 2024 14:1 2024, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengshol, J.A.; Golden-Mason, L.; Arikawa, T.; Smith, M.; Niki, T.; McWilliams, R.; Randall, J.A.; McMahan, R.; Zimmerman, M.A.; Rangachari, M.; et al. A Crucial Role for Kupffer Cell-Derived Galectin-9 in Regulation of T Cell Immunity in Hepatitis C Infection. PLoS One 2010, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.X.; Chen, X.; Hsu, D.K.; Baghy, K.; Serizawa, N.; Scott, F.; Takada, Y.; Takada, Y.; Fukada, H.; Chen, J.; et al. Galectin-3 Modulates Phagocytosis-Induced Stellate Cell Activation and Liver Fibrosis in Vivo. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2011, 302, G439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.X.; Chen, X.; Hsu, D.K.; Baghy, K.; Serizawa, N.; Scott, F.; Takada, Y.; Takada, Y.; Fukada, H.; Chen, J.; et al. Galectin-3 Modulates Phagocytosis-Induced Stellate Cell Activation and Liver Fibrosis in Vivo. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2011, 302, G439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, A.; Sayed, N.; Allawadhi, P.; Weiskirchen, R. It’s All about the Spaces between Cells: Role of Extracellular Matrix in Liver Fibrosis. Ann Transl Med 2021, 9, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundblad, V.; Quintar, A.A.; Morosi, L.G.; Niveloni, S.I.; Cabanne, A.; Smecuol, E.; Mauriño, E.; Mariño, K. V.; Bai, J.C.; Maldonado, C.A.; et al. Galectins in Intestinal Inflammation: Galectin-1 Expression Delineates Response to Treatment in Celiac Disease Patients. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 337126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A.M.; Khadka, S.; Sato, F.; Omura, S.; Fujita, M.; Hsu, D.K.; Liu, F.T.; Tsunoda, I. Galectin-3 as a Therapeutic Target for NSAID-Induced Intestinal Ulcers. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 550366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Muynck, K.; Vanderborght, B.; Van Vlierberghe, H.; Devisscher, L. The Gut–Liver Axis in Chronic Liver Disease: A Macrophage Perspective. Cells 2021, 10, 2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kram, M. Galectin-3 Inhibition as a Potential Therapeutic Target in Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis Liver Fibrosis. World J Hepatol 2023, 15, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, D.; Biswas, S.; Pal, S.; Nandi, S.; Khatun, N.; Jha, R.; Chakraborty, B.C.; Baidya, A.; Ghosh, R.; Banerjee, S.; et al. Monocyte-Derived Galectin-9 and PD-L1 Differentially Impair Adaptive and Innate Immune Response in Chronic HBV Infection and Their Expression Remain Unaltered after Antiviral Therapy. Front Immunol 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Jiao, D.; Yang, F.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Han, D.; Zhang, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Yang, A.G.; et al. Galectin-9 Expression Predicts Poor Prognosis in Hepatitis B Virus-Associated Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Aging 2022, 14, 1879–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mani, S.K.K.; Andrisani, O. Hepatitis B Virus-Associated Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Hepatic Cancer Stem Cells. Genes 2018, Vol. 9, Page 137 2018, 9, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagahara, K.; Arikawa, T.; Oomizu, S.; Kontani, K.; Nobumoto, A.; Tateno, H.; Watanabe, K.; Niki, T.; Katoh, S.; Miyake, M.; et al. Galectin-9 Increases Tim-3+ Dendritic Cells and CD8+ T Cells and Enhances Antitumor Immunity via Galectin-9-Tim-3 Interactions. J Immunol 2008, 181, 7660–7669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uluca, Ü.; Şen, V.; Ece, A.; Tan, İ.; Karabel, D.; Aktar, F.; Karabel, M.; Balık, H.; Güneş, A. Serum Galectin-3 Levels in Children with Chronic Hepatitis B Infection and Inactive Hepatitis B Carriers. Med Sci Monit 2015, 21, 1376–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, M.; Hao, X.; Wei, H.; Sun, R.; Tian, Z. Galectin-3-ITGB1 Signaling Mediates Interleukin 10 Production of Hepatic Conventional Natural Killer Cells in Hepatitis B Virus Transgenic Mice and Correlates with Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression in Patients. Viruses 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, X.; Tian, L.; Chen, Y. Cytokine-Mediated Immunopathogenesis of Hepatitis B Virus Infections. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2016, 50, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, A.C.; Sun, R.; Mishin, V.; Hall, L.R.B.; Laskin, J.D.; Laskin, D.L. Role of Galectin-3 in Acetaminophen-Induced Hepatotoxicity and Inflammatory Mediator Production. Toxicol Sci 2012, 127, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, G.; Furushima, D.; Niki, T.; Matsuba, T.; Maeda, Y.; Takahashi, A.; Hattori, T.; Ashino, Y. High Levels of the Cleaved Form of Galectin-9 and Osteopontin in the Plasma Are Associated with Inflammatory Markers That Reflect the Severity of COVID-19 Pneumonia. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.H.; Lin, C.Y.; Chang, M.R.; Urbina, A.N.; Assavalapsakul, W.; Thitithanyanont, A.; Chen, Y.H.; Liu, F.T.; Wang, S.F. The Role of Galectins in Virus Infection - A Systemic Literature Review. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection 2020, 53, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K.; Niki, T.; Nomura, T.; Oura, K.; Tadokoro, T.; Sakamoto, T.; Tani, J.; Yoneyama, H.; Morishita, A.; Kuroda, N.; et al. Correlation between Serum Galectin-9 Levels and Liver Fibrosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018, 33, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreca, A.P.; Gaetani, M.; Busà, R.; Francipane, M.G.; Gulotta, M.R.; Perricone, U.; Iannolo, G.; Russelli, G.; Carcione, C.; Conaldi, P.G.; et al. Galectin-9 and Interferon-Gamma Are Released by Natural Killer Cells upon Activation with Interferon-Alpha and Orchestrate the Suppression of Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamseddine, S.; Yavuz, B.G.; Mohamed, Y.I.; Lee, S.S.; Yao, J.C.; Hu, Z.I.; LaPelusa, M.; Xiao, L.; Sun, R.; Morris, J.S.; et al. Circulating Galectin-3: A Prognostic Biomarker in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Immunother Precis Oncol 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weigand, K.; Peschel, G.; Grimm, J.; Müller, M.; Buechler, C. Serum Galectin-3 in Hepatitis C Virus Infection Declines after Successful Virus Eradication by Direct-Acting Antiviral Therapy. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2022, 31, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Cao, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Cheng, X.; Tang, Y.; Xing, M.; Yao, P. Chronic High-Fat Diet Induces Galectin-3 and TLR4 to Activate NLRP3 Inflammasome in NASH. J Nutr Biochem 2023, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, M.; Seino, K.I.; Nakayama, T. The NKT Cell System: Bridging Innate and Acquired Immunity. Nat Immunol 2003, 4, 1164–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, M.; Seino, K.I.; Nakayama, T. The NKT Cell System: Bridging Innate and Acquired Immunity. Nat Immunol 2003, 4, 1164–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.-H.; Liang, S.; Potter, J.; Jiang, X.; Mao, H.-Q.; Li, Z. Tim-3/Galectin-9 Regulate the Homeostasis of Hepatic NKT Cells in a Murine Model of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. The Journal of Immunology Author Choice 2013, 190, 1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, A.; Palma, E.; Devshi, D.; Corrigall, D.; Adams, H.; Heaton, N.; Menon, K.; Preziosi, M.; Zamalloa, A.; Miquel, R.; et al. Soluble TIM3 and Its Ligands Galectin-9 and CEACAM1 Are in Disequilibrium During Alcohol-Related Liver Disease and Promote Impairment of Anti-Bacterial Immunity. Front Physiol 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhi, M.S.; Ma, Y.; Mieli-Vergani, G.; Vergani, D. Aetiopathogenesis of Autoimmune Hepatitis. J Autoimmun 2010, 34, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Bogdanos, D.P.; Hussain, M.J.; Underhill, J.; Bansal, S.; Longhi, M.S.; Cheeseman, P.; Mieli-Vergani, G.; Vergani, D. Polyclonal T-Cell Responses to Cytochrome P450IID6 Are Associated with Disease Activity in Autoimmune Hepatitis Type 2. Gastroenterology 2006, 130, 868–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberal, R.; Grant, C.R.; Holder, B.S.; Ma, Y.; Mieli-Vergani, G.; Vergani, D.; Longhi, M.S. The Impaired Immune Regulation of Autoimmune Hepatitis Is Linked to a Defective Galectin-9/Tim-3 Pathway. Hepatology 2012, 56, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschfield, G.M.; Gershwin, M.E. The Immunobiology and Pathophysiology of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Annu Rev Pathol 2013, 8, 303–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arsenijevic, A.; Stojanovic, B.; Milovanovic, J.; Arsenijevic, D.; Arsenijevic, N.; Milovanovic, M. Galectin-3 in Inflammasome Activation and Primary Biliary Cholangitis Development. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, F.; Jin, M.; Cao, D.; Jia, Z.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, J. Galectin-3 Not Galectin-9 as a Candidate Prognosis Marker for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. PeerJ 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.S.; Weng, D.S.; Wang, Q.J.; Pan, K.; Zhang, Y.J.; Li, Y.Q.; Li, J.J.; Zhao, J.J.; He, J.; Lv, L.; et al. Galectin-3 Is Associated with a Poor Prognosis in Primary Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Transl Med 2014, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Wang, H.Y.; Miyahara, Y.; Peng, G.; Wang, R.F. Tumor-Associated Galectin-3 Modulates the Function of Tumor-Reactive T Cells. Cancer Res 2008, 68, 7228–7236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lærum, O.D.; Ovrebo, K.; Skarstein, A.; Christensen, I.J.; Alpízar-Alpízar, W.; Helgeland, L.; Danø, K.; Nielsen, B.S.; Illemann, M. Prognosis in Adenocarcinomas of Lower Oesophagus, Gastro-Oesophageal Junction and Cardia Evaluated by UPAR-Immunohistochemistry. Int J Cancer 2012, 131, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Hu, Z.; He, F.; Gao, C.; Xu, L.; Zou, H.; Wu, Z.; Jiang, X.; Wang, J. Downregulation of Galectin-3 Causes a Decrease in UPAR Levels and Inhibits the Proliferation, Migration and Invasion of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Oncol Rep 2014, 32, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K.; Iwama, H.; Sakamoto, T.; Okura, R.; Kobayashi, K.; Takano, J.; Katsura, A.; Tatsuta, M.; Maeda, E.; Mimura, S.; et al. Galectin-9 Suppresses the Growth of Hepatocellular Carcinoma via Apoptosis in Vitro and in Vivo. Int J Oncol 2015, 46, 2419–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K.; Iwama, H.; Sakamoto, T.; Okura, R.; Kobayashi, K.; Takano, J.; Katsura, A.; Tatsuta, M.; Maeda, E.; Mimura, S.; et al. Galectin-9 Suppresses the Growth of Hepatocellular Carcinoma via Apoptosis in Vitro and in Vivo. Int J Oncol 2015, 46, 2419–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Pu, J.; Bai, J.; Yin, Y.; Wu, K.; Wang, J.; Shuai, X.; Gao, J.; Tao, K.; Wang, G.; et al. EZH2 Promotes Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression through Modulating MiR-22/Galectin-9 Axis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2018, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setayesh, T.; Hu, Y.; Vaziri, F.; Chen, X.; Lai, J.; Wei, D.; Yvonne Wan, Y.J. Targeting Stroma and Tumor, Silencing Galectin 1 Treats Orthotopic Mouse Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Acta Pharm Sin B 2024, 14, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Li, D.K.; Hu, X.; Cheng, C.; Zhang, Y. Galectin-1–RNA Interaction Map Reveals Potential Regulatory Roles in Angiogenesis. FEBS Lett 2021, 595, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacigalupo, M.L.; Manzi, M.; Espelt, M. V.; Gentilini, L.D.; Compagno, D.; Laderach, D.J.; Wolfenstein-Todel, C.; Rabinovich, G.A.; Troncoso, M.F. Galectin-1 Triggers Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. J Cell Physiol 2015, 230, 1298–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.F.; Li, K.S.; Shen, Y.H.; Gao, P.T.; Dong, Z.R.; Cai, J.B.; Zhang, C.; Huang, X.Y.; Tian, M.X.; Hu, Z.Q.; et al. Galectin-1 Induces Hepatocellular Carcinoma EMT and Sorafenib Resistance by Activating FAK/PI3K/AKT Signaling. Cell Death Dis 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Zhai, B.; Sun, W.; Hu, F.; Cheng, H.; Xu, J. Activation of Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/AKT/Snail Signaling Pathway Contributes to Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition-Induced Multi-Drug Resistance to Sorafenib in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. PLoS One 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K.; Niki, T.; Nomura, T.; Oura, K.; Tadokoro, T.; Sakamoto, T.; Tani, J.; Yoneyama, H.; Morishita, A.; Kuroda, N.; et al. Correlation between Serum Galectin-9 Levels and Liver Fibrosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018, 33, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.W.; Park, M.; Hur, M.; Kim, H.; Choe, W.H.; Yun, Y.M. Usefulness of Enhanced Liver Fibrosis, Glycosylation Isomer of Mac-2 Binding Protein, Galectin-3, and Soluble Suppression of Tumorigenicity 2 for Assessing Liver Fibrosis in Chronic Liver Diseases. Ann Lab Med 2018, 38, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, S.A.; De Freitas Souza, B.S.; Barreto, E.P.S.; Kaneto, C.M.; Neto, H.A.; Azevedo, C.M.H.; Guimarães, E.T.; De Freitas, L.A.R.; Ribeiro-Dos-Santos, R.; Soares, M.B.P. Reduction of Galectin-3 Expression and Liver Fibrosis after Cell Therapy in a Mouse Model of Cirrhosis. Cytotherapy 2012, 14, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Xu, S.; Liu, Y.; Xu, X.; Philips, C.A.; Chen, J.; Méndez-Sánchez, N.; Guo, X.; Qi, X. Role of Galectins in the Liver Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, M.; Kanbe, A.; Noguchi, K.; Niwa, A.; Imaizumi, Y.; Kuroda, T.; Ichihashi, K.; Okubo, T.; Mori, K.; Kanayama, T.; et al. Time-Course Analysis of Liver and Serum Galectin-3 in Acute Liver Injury after Alpha-Galactosylceramide Injection. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0298284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volarevic, V.; Markovic, B.S.; Bojic, S.; Stojanovic, M.; Nilsson, U.; Leffler, H.; Besra, G.S.; Arsenijevic, N.; Paunovic, V.; Trajkovic, V.; et al. Gal-3 Regulates the Capacity of Dendritic Cells to Promote NKT-Cell-Induced Liver Injury. Eur J Immunol 2015, 45, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Liver disease | Related galectins | Function and Clinical Significance | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic Hepatitis B | Gal-9 | PD-L1-induced attenuation of antiviral cytokine release severely impairs the host’s immune response | 118 |

| Independent prognostic markers of HBV-associated HCC | 119,120 | ||

| Negatively regulates the immune response mediated by T helper cells | 121 | ||

| Gal-3 | Stimulates the production of cytokines and chemokines | 122 | |

| Stimulates fibrogenesis by reducing IL-10 production | 123,124,125 | ||

| Chronic Hepatitis C | Gal-9 | Expressed in hepatocytes and Kupffer cells | 127 |

| Positively correlated with persistence of infection and progression of chronic liver disease | 128 | ||

| Secretion is promoted by IFN-α and inhibits HCV infection | 129 | ||

| Gal-3 | Increased in HCV positive | 130 | |

| Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease/steatohepatitis (MASLD/MASH) | Gal-3 | Involved in the initiation of hepatic lipid imbalance and inflammation | 132 |

| Ga-9 | Activation-induced apoptosis and homeostasis of hepatic NKT cells | 135 | |

| Alcohol Associated Liver Disease | Gal-9 | Increase Tim-3 levels | 136 |

| Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) | Gal-9 | Inhibits T helper 1 immune responses by binding to Tim-3 on CD4 effector cells | 140 |

| Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) | Gal-3 | Induces the production of inflammatory cytokines and damages biliary epithelial cells | 142 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Gal-3 | Inhibits tumor-reactive T cells and promotes tumor growth | 143 |

| Promotes angiogenesis | 144 | ||

| Inhibits tumor-reactive T cells | 145 | ||

| Decreases urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) mRNA and protein levels and downstream signaling pathways of uPAR | 147, 149 | ||

| Gal-9 | Induces apoptosis | 148 | |

| Boosts anti-tumor immunity through interaction with mucin domain-containing -3 | 121 | ||

| Targets of microRNA 22 | 150 | ||

| Gal-1 | Interacts with mRNA that prefers binding to obstructive codons, thereby regulating angiogenesis | 152 | |

| Induction of epithelial mesenchymal transition | 153,154,155 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).