Submitted:

18 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Medicinal plants have been used extensively as sources of a wide variety of biologically active compounds for many centuries and as crude materials or pure compounds for treating various disease conditions. The leaves of the plant have been applied in treating snakebite, stomach ache, cough and so on. The plant leaves were extracted with hexane and methanol using the soxhlet extraction process. In this study, leaf extracts of G. senegalensis were profiled and evaluated for their phospholipase A2 inhibitory potential via experimental and computational approaches. Characterization of the extracts was done using GC-MS analysis, Antisnake venom screening was conducted using PLA2 acidimetric assay while Insilco molecular docking studies was performed using AutoDock vina in PyRx and ADMET was predicted using swiiADME and protox-II online servers. GC-MS analysis revealed the presence of 50 compounds from which 14, 4, 15, 13 and 13 were for hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, butanol and aqueous fractions respectively. The PLA2 acidimetric assay was used to screen the fractions for inhibitory activity against N. nigricollis venom in vitro. The results showed that the aqueous fraction was the most active, with PLA2 inhibition ranging from 66.18 to 74.67% at 1.0 to 0.125 mg/cm3, respectively. The fractions inhibited the hydrolytic effects of the N. nigricollis PLA2 enzyme, exhibiting considerable (p<0.05) antisnake venom activity. In comparison to the standards, four compounds exhibited a higher docking score (-8.7 to -8.4 kcal/mol). Insilico ADME and Drug-likeness revealed the compounds have passed absorptivity test for oral medication as well as indicating lower likelihood of interacting with other drugs. The results also showed the compounds to be slightly toxic. The results of this study supported the use of G. senegalensis in traditional medicine by demonstrating that its leaves contains phytoconstituents with antisnake properties.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Identification

2.2. Preparation of Plant Material

2.3. Extraction

2.4. The Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Analysis (GC-MS)

2.5. Snake Venom

2.6. Antisnake Venom (ASV)

2.7. Software Used

2.8. Phospholipase A2 (PLA2) Enzyme Assay

2.9. In Silico Molecular Docking Analysis

2.9.1. Ligands Preparation

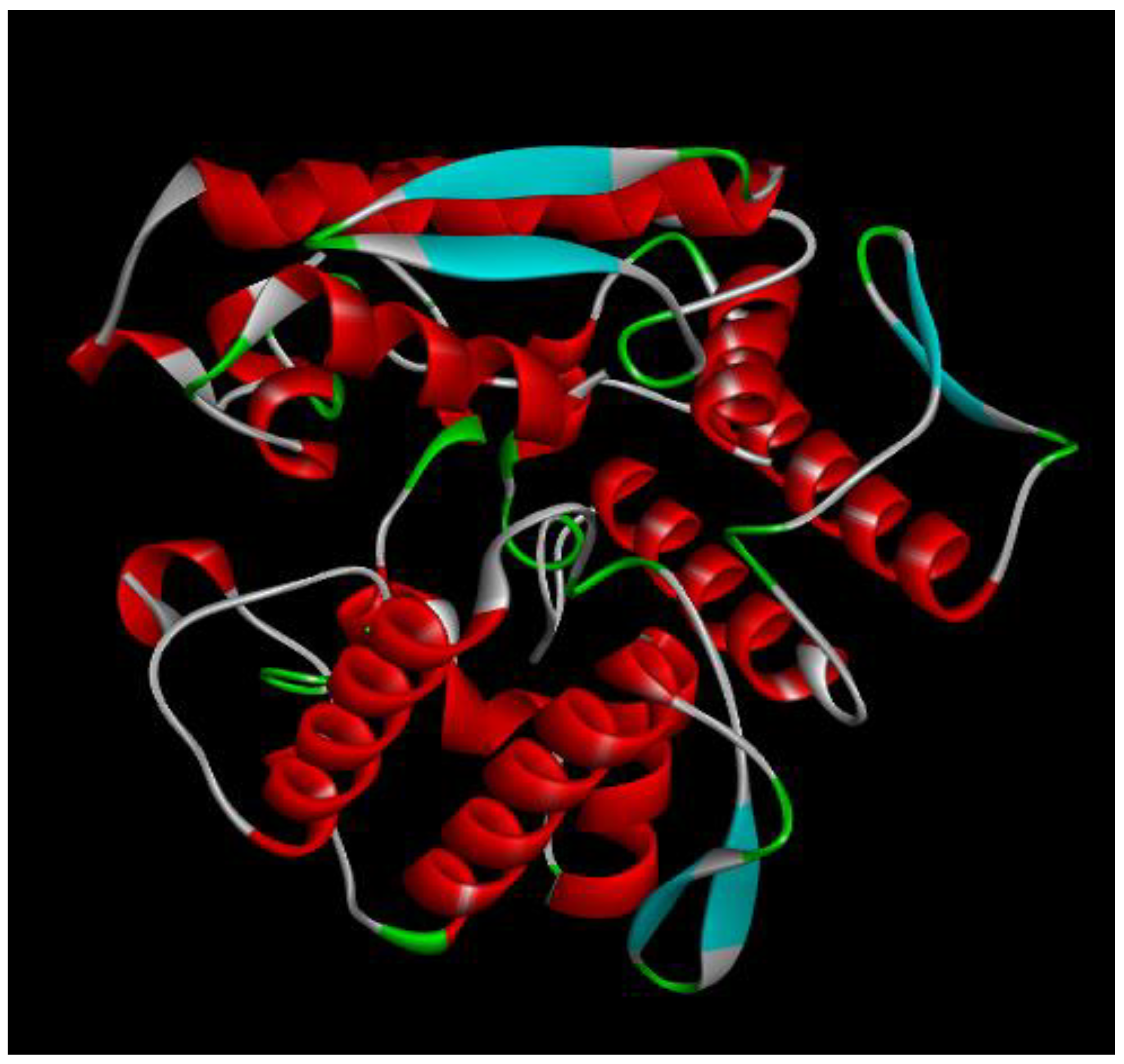

2.9.2. Protein preparation

2.9.3. In Silico ADMET and Drug-Likeness Prediction

3. Results

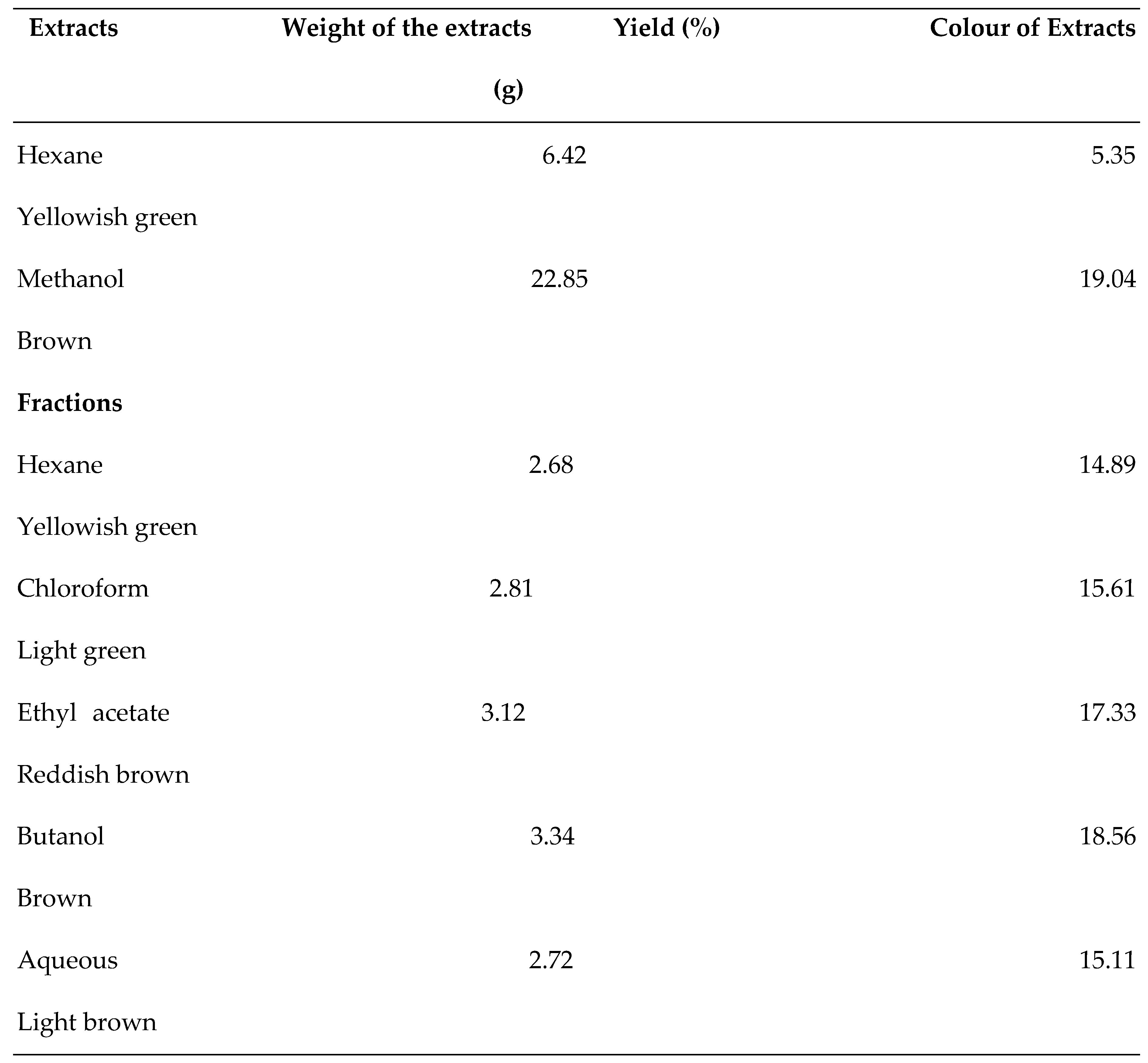

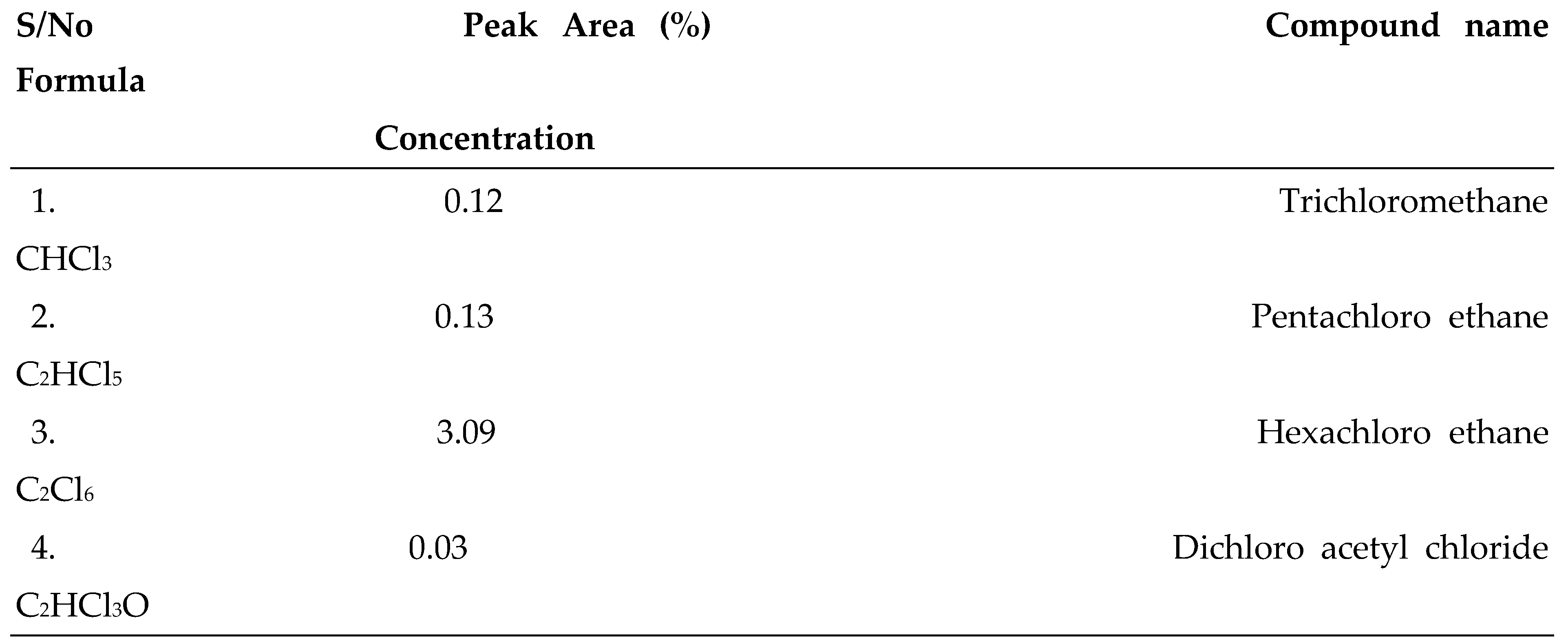

3.1. GC-MS Analysis

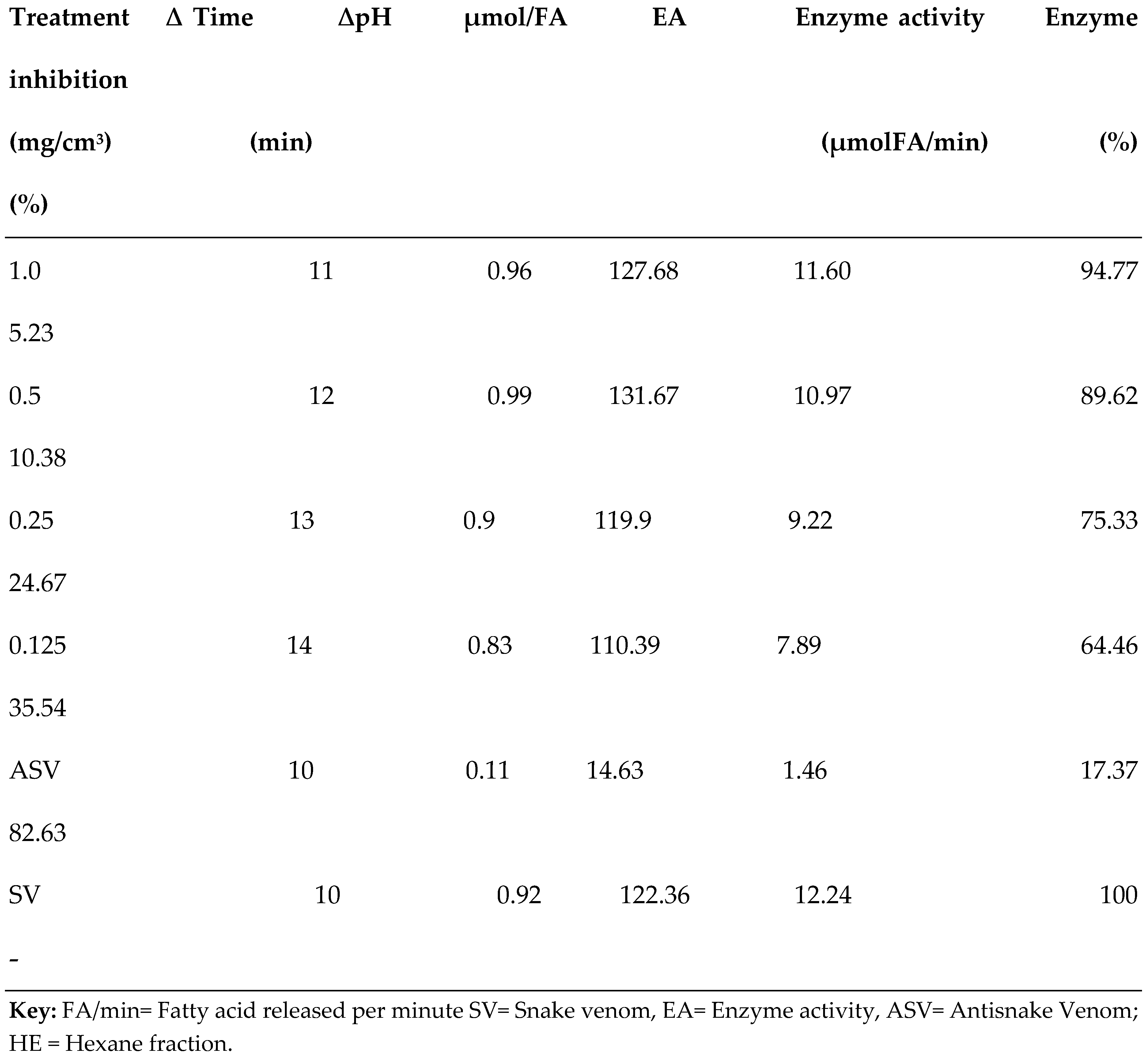

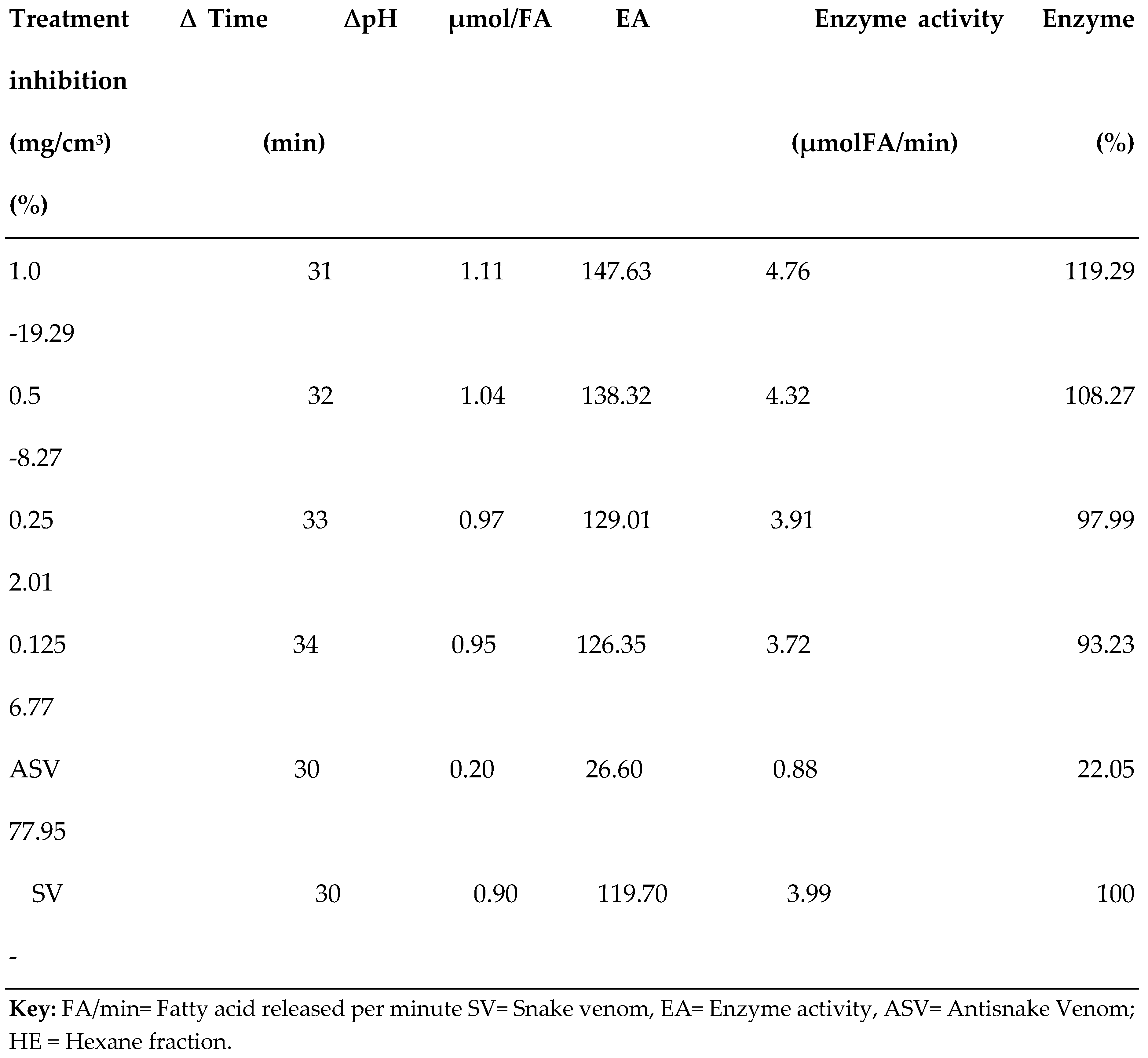

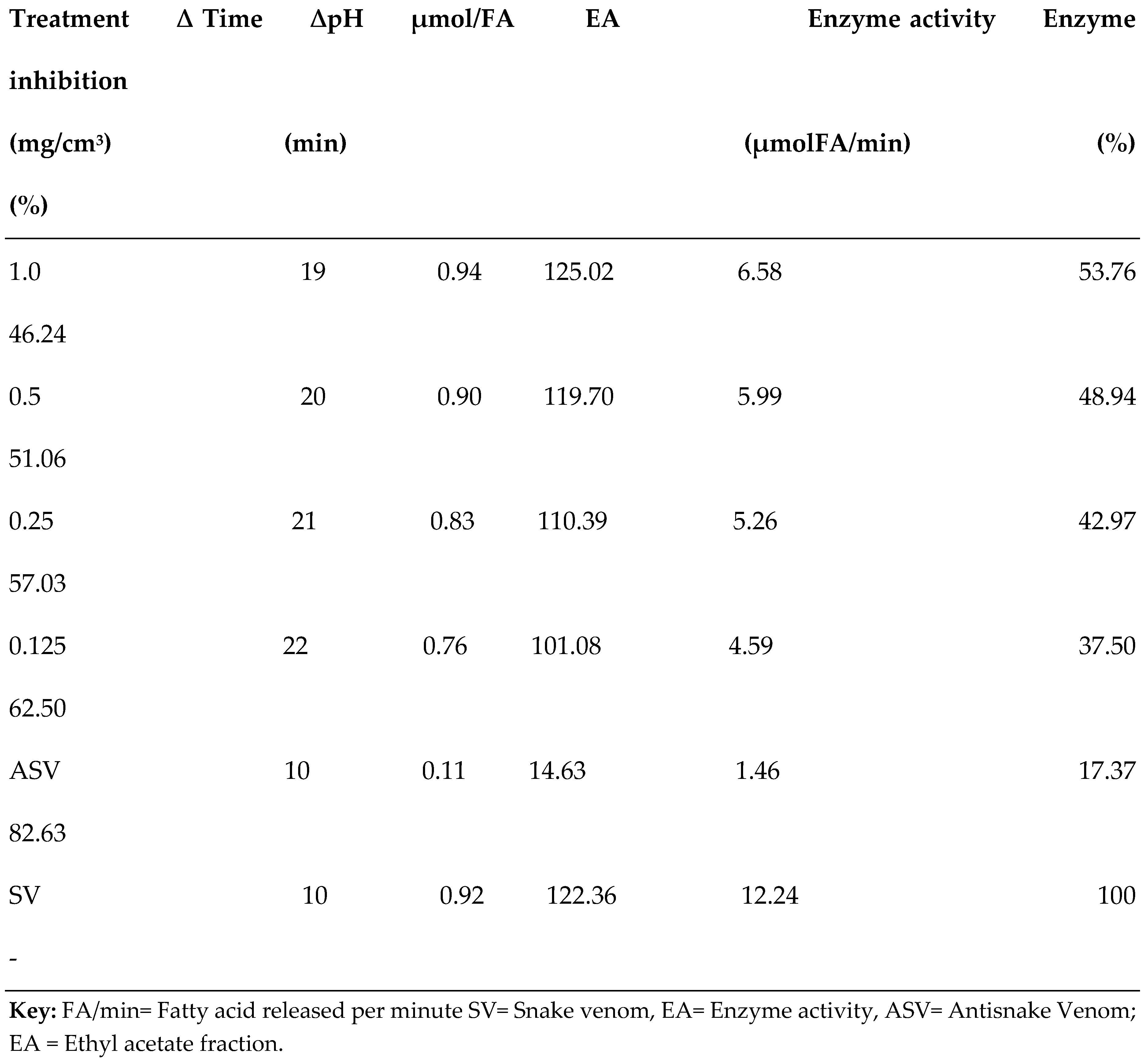

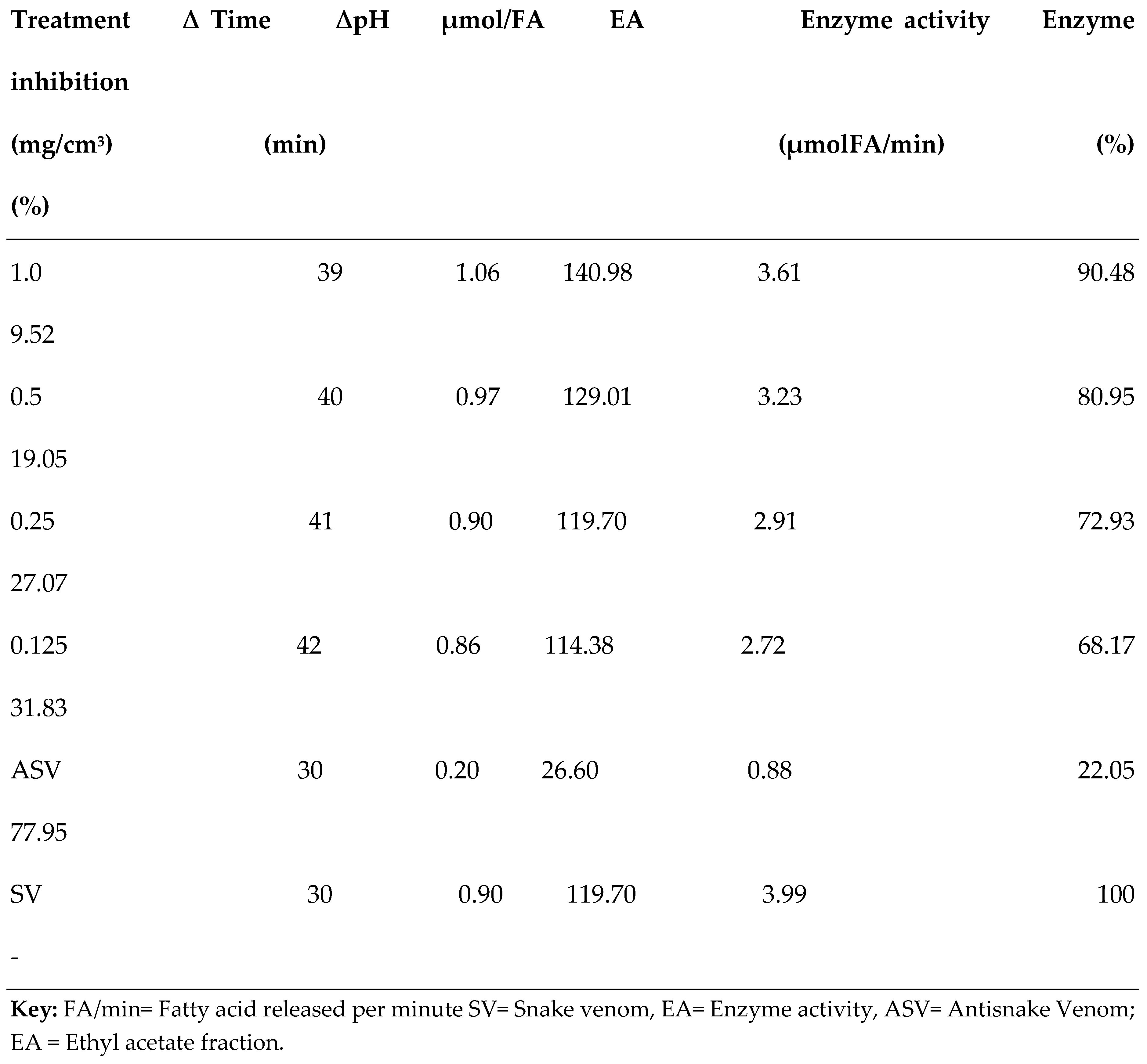

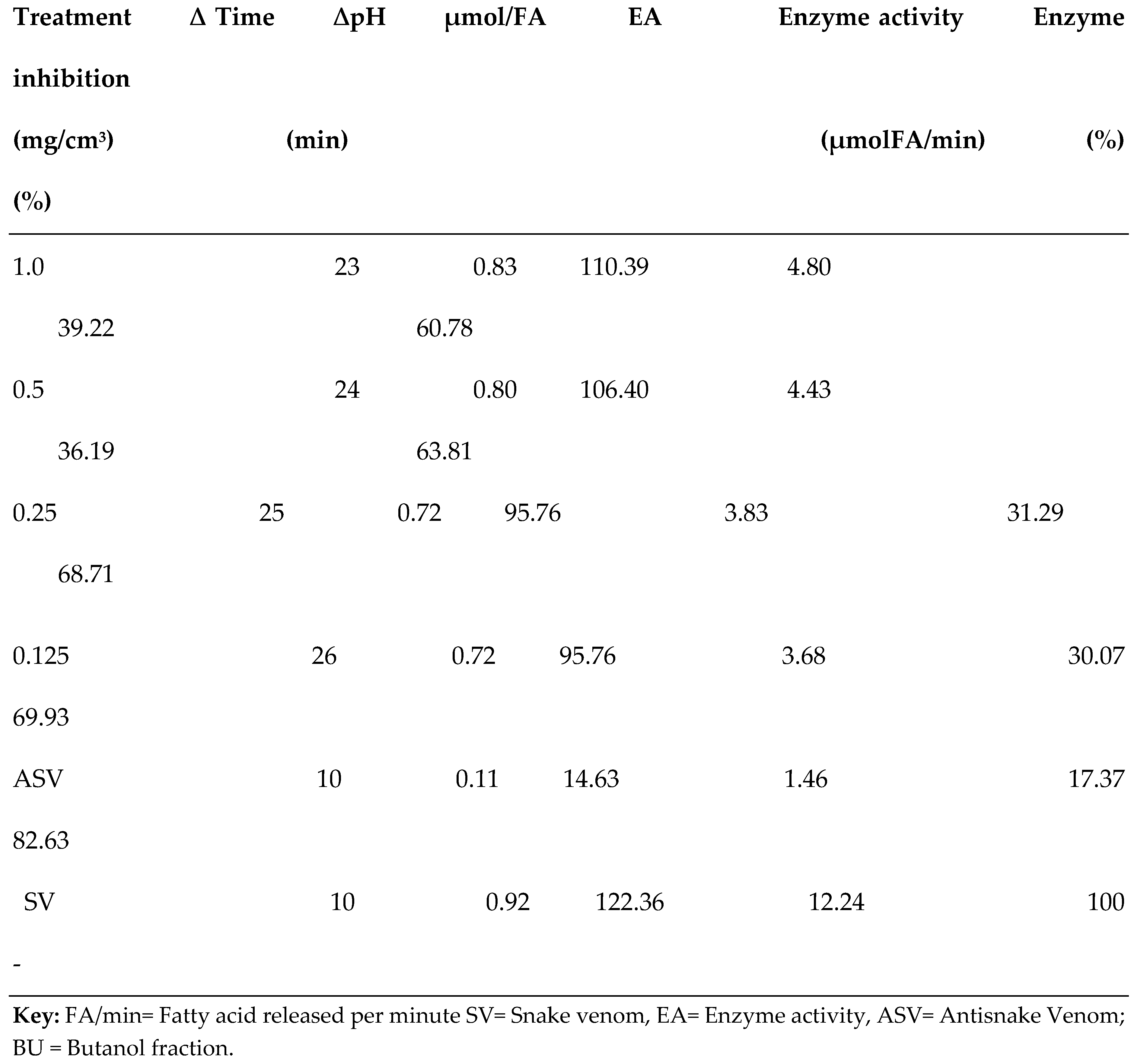

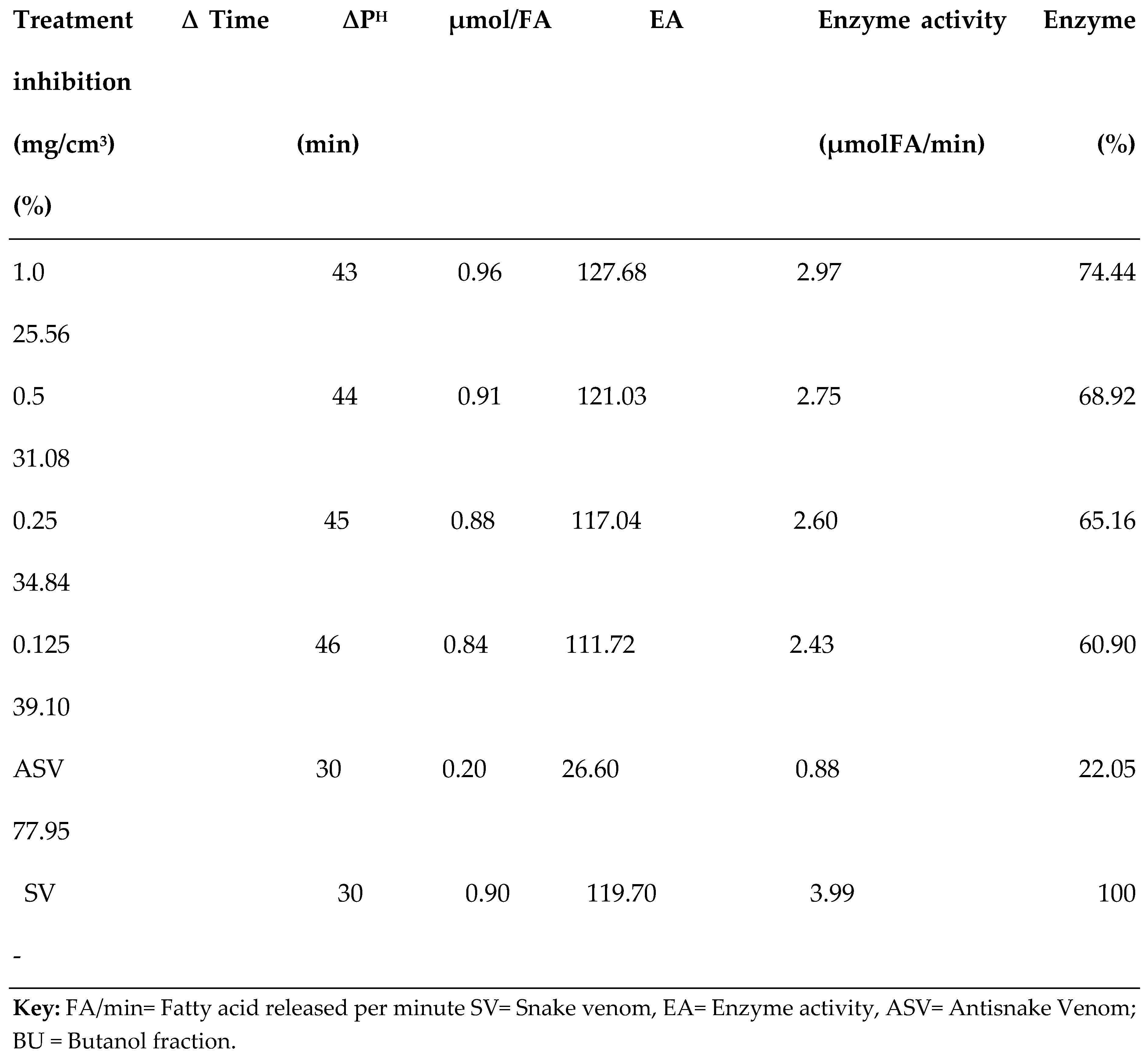

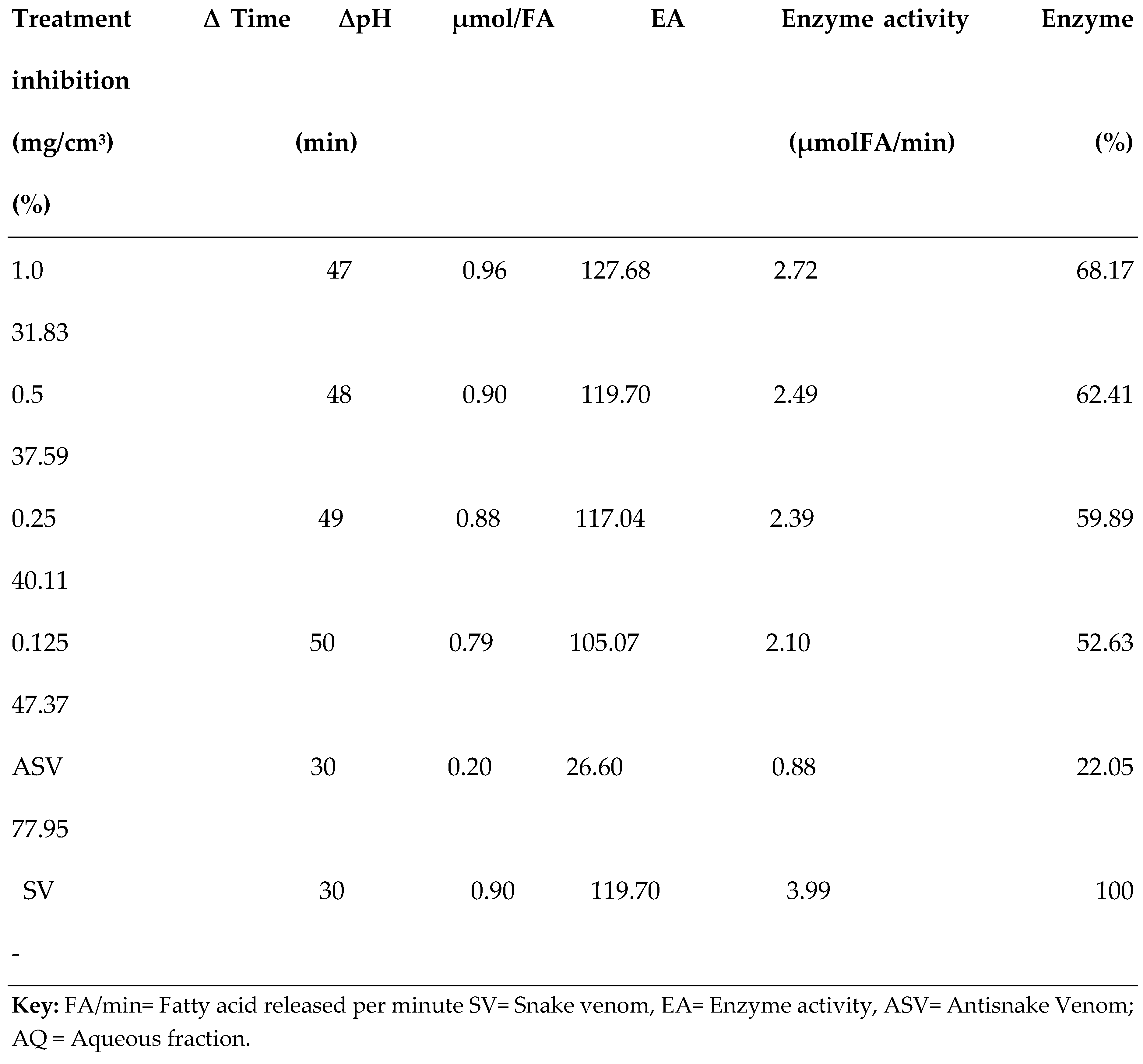

3.2. PLA2 Enzyme Assay

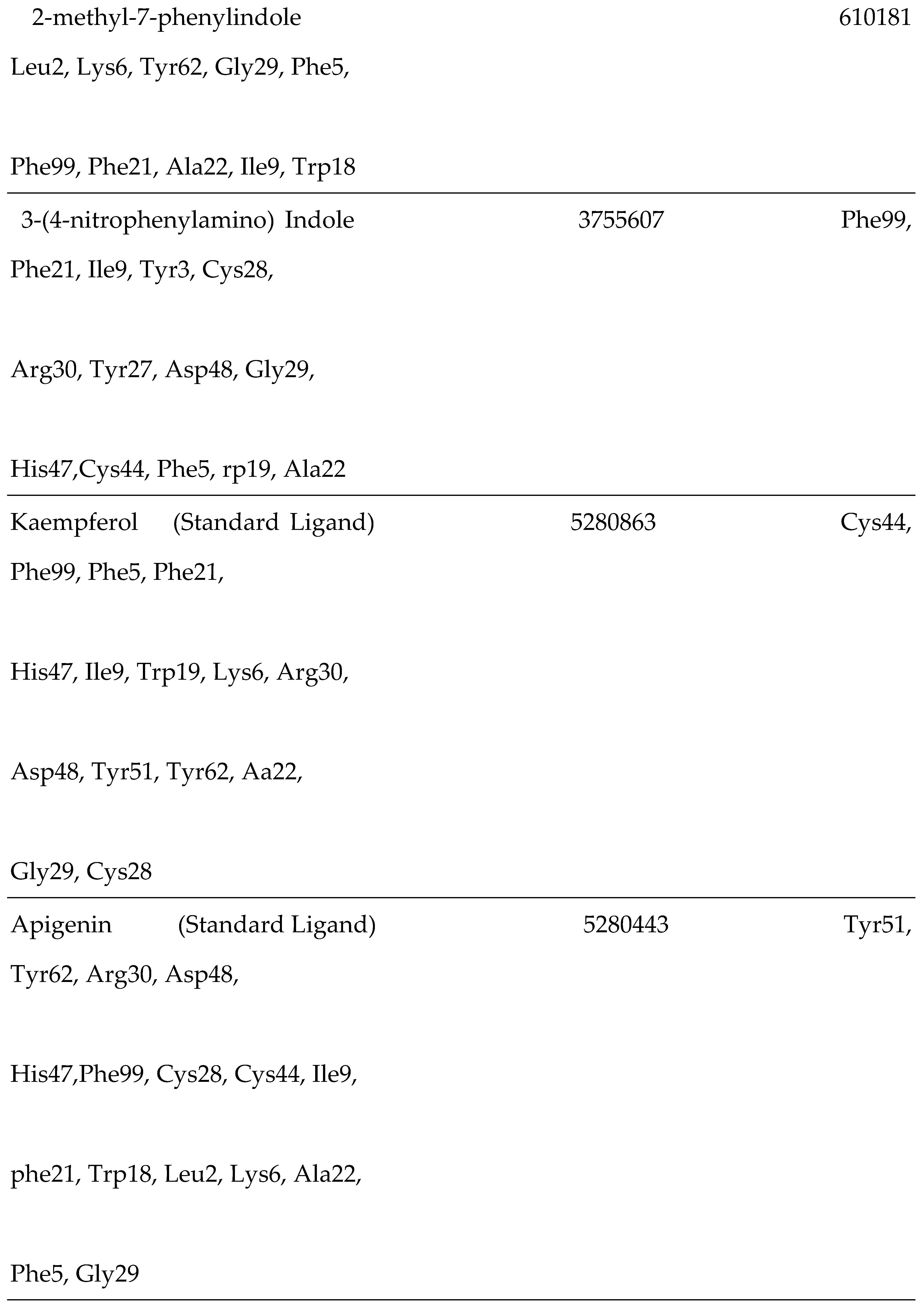

3.3. In Silico Studies

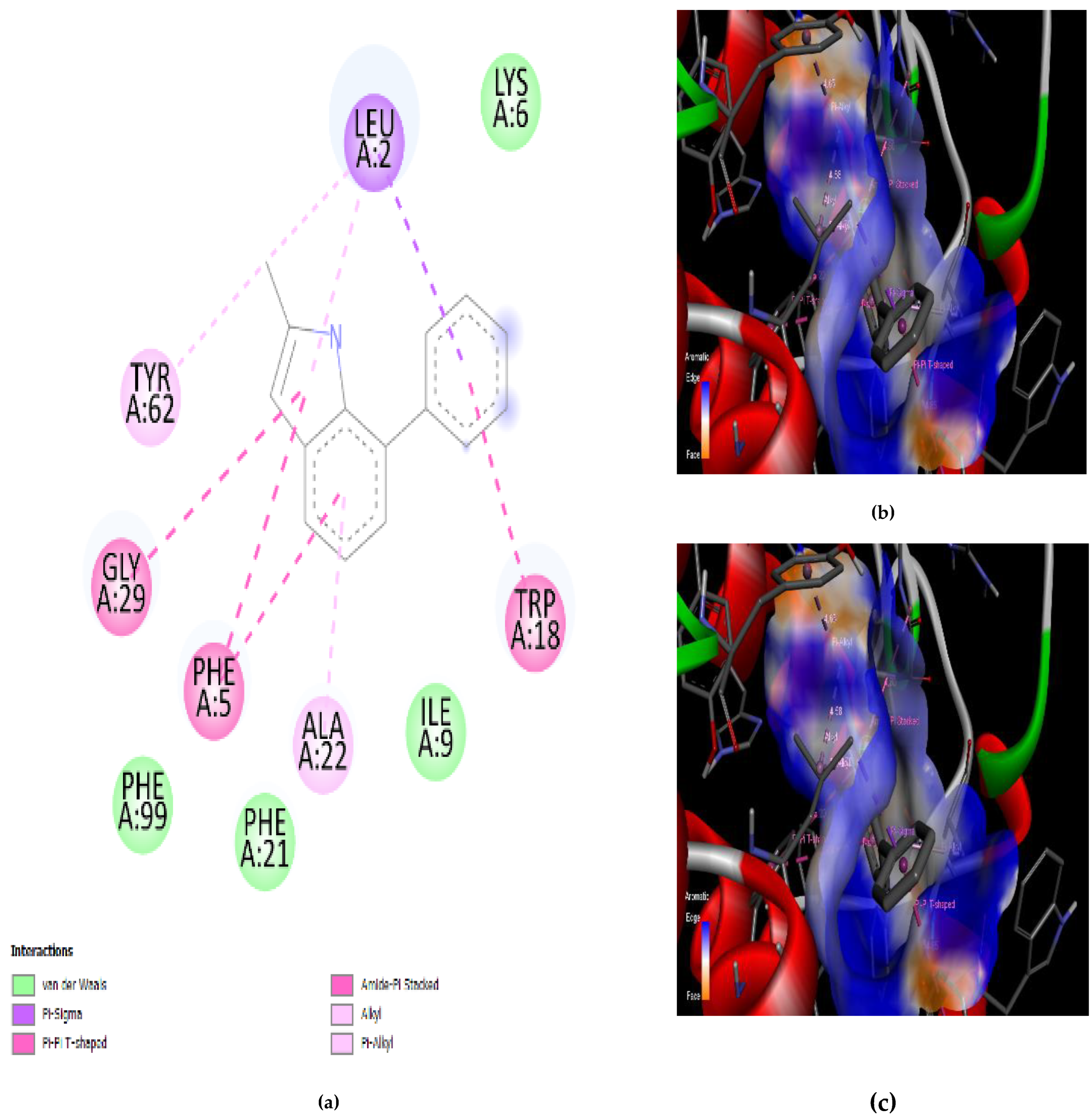

3.4. Interaction of the Compounds with PLA2 from G. senegalensis

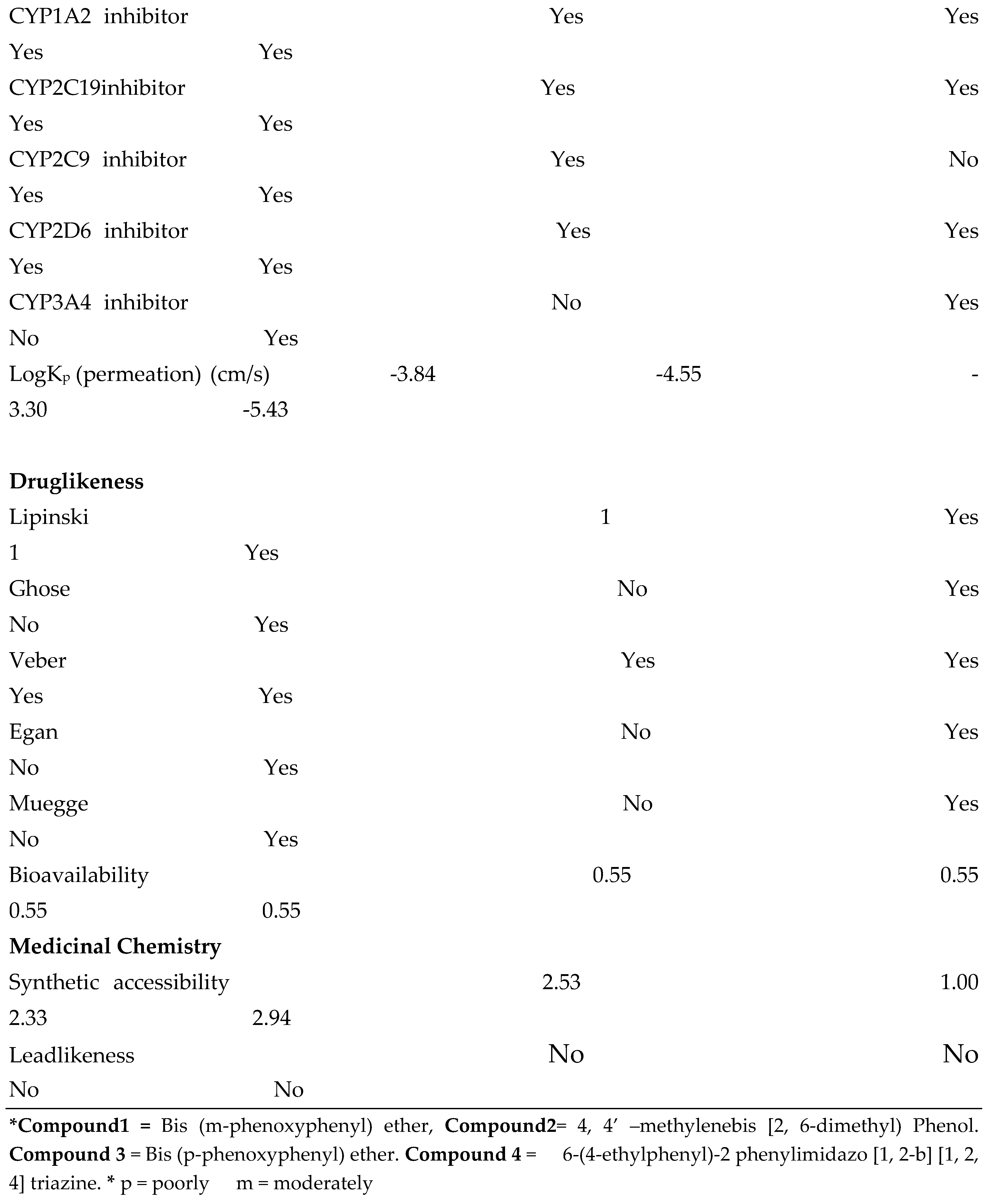

4.5. In Silico ADME and Drug-Likeness

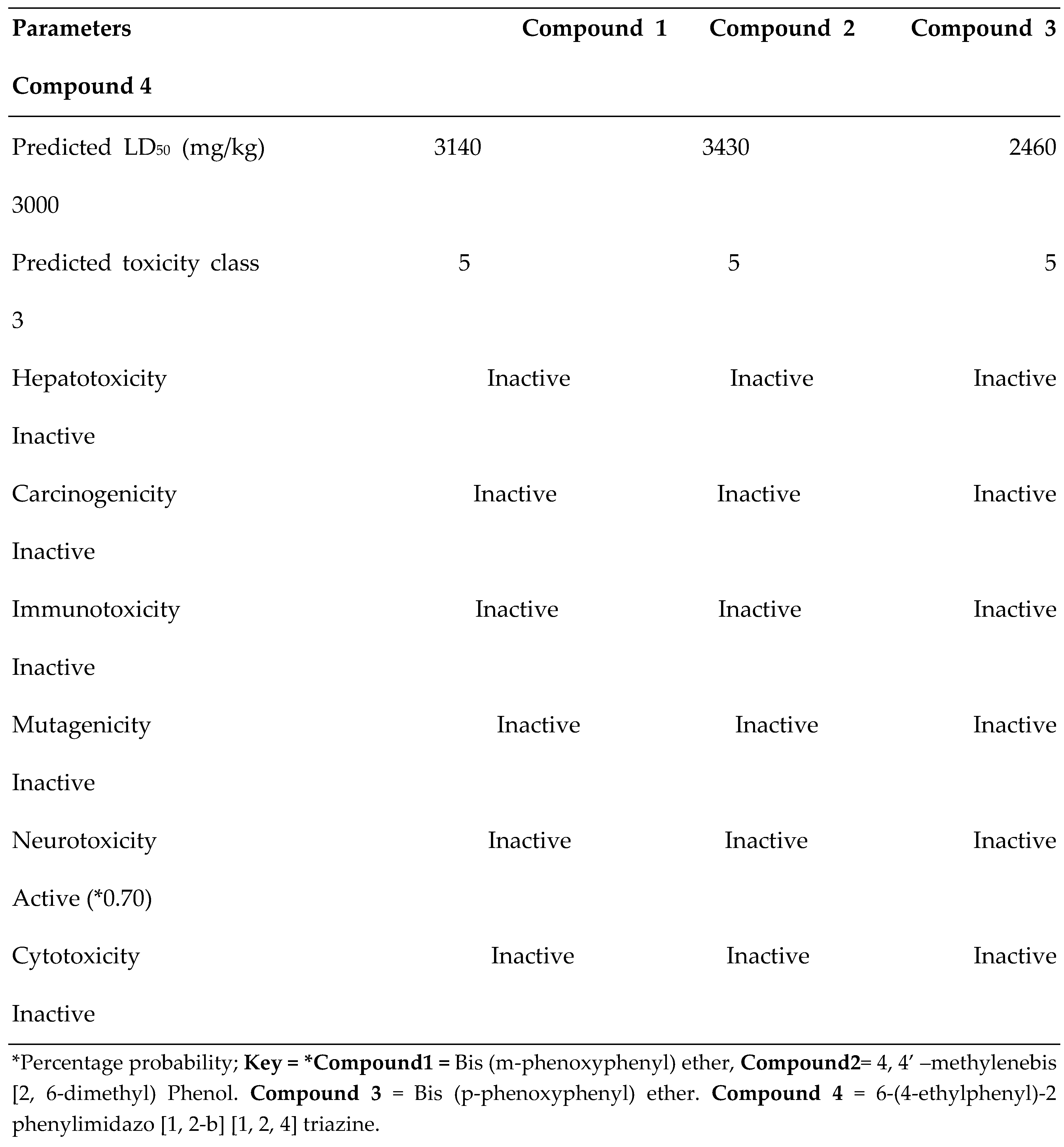

3.5. Toxicity Profile

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflict of Interest

References

- Abeer, F.A., Mohanad, J.K., Imad H, H., 2017. Phytochemical Profiles of Methanolic Seeds Extract of Cuminum cyminum using GC-MS Technique. International Journal of Current Pharmaceutical Review and Research; 8(2); 114-124.

- Abubakar, M., Sule, M., Pateh, U., Abdurahman, E., Haruna, A., 2000. In vitro snake venom detoxifying action of the leaf extract of Guiera senegalensis. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 3: 253-257. [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, M.S., Nok, A.J., Abdurahman, E.M., Haruna, A.K., Shok, M., 2003. Purification and activity of two phospholipase enzymes from Naja nigricolis nigricolis Reinhardt venom. Journal of Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology. [CrossRef]

- Al-Asmari, A.K., Albalawi, S.M., Athar, M.T., Khan, A.Q., Al-Shahrani, H., Islam, M., 2015. Moringa oleifera as an anti-cancer agent against breast and colorectal cancer cell lines. PLoSOne;10:e0135814. [CrossRef]

- Ameen, S.A., Salihu, T., Mbaoji, C.O., Anoruo-Dibia, C.A., Adedokun, R.M., 2015. Medicinal plants used to treat Snake bite by Fulani Herdsmen in Taraba State, Nigeria. Anim Sci.;1 1(1-2):10-21.

- Aparna, P., Divya, L., Bhadrayya, K., 2013. Formulation and in vitro evaluation of Carvedilol.

- Transdermal Delivery System. Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research; 12 (4): 461-467. [CrossRef]

- Bawaskar, H.S., 2004. Snake venoms and antivenoms: critical supply issues. Journal of the Association of Physicians of India. 52: 11–13.

- Belal, A., 2018. Drug likeness, targets, molecular docking and ADMET studies for some indolizine derivatives. Die Pharmazie-An International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 73(11), 635-642. [CrossRef]

- Brinkley, R.L., Gupta, R.B., 2001. Hydrogen bonding with aromatic rings. AIChE J. [CrossRef]

- Celestine, U.A., Christopher, G.B., Innocent, O.O., 2017. Phytochemical profile of stem bark extracts of Khaya senegalensis by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytotherapy. [CrossRef]

- C´esar, L.S.G., Leandro, S.M., Renata, S.F., T´assia, R.C., Lorane, I.S.H., Silvana, M., Bruna, M.A., 2014. Biodiversity as a source of bioactive compounds against snakebites, Curr. Med. Chem.1–24.

- Daina, A., Zoete, V.A., 2016. BOILED-Egg to predict gastrointestinal absorption and brain penetration of small molecules. ChemMedChem: 11(11):1117–1121. [CrossRef]

- Divya, J., Vibha, R., 2023. In Silico Studies of Phytoconstituents from Piper longum and Ocimum sanctum as ACE2 and TMRSS2 Inhibitors: Strategies to Combat COVID -19. [CrossRef]

- Eltoum, M.S.A., Adam, A.H., Mohamed, H.A., Abody, S.M., 2020. Identification of an Active Component in Guiera senegalensis Plant Used for Healing Diabetes Wounds. International Journal of Pharmacy and Chemistry, 6(1): 6-10. [CrossRef]

- Fan, J., Fu, A., Zhang, L., 2019. Progress in molecular docking. Quantitative Biology, 7, 83-89. [CrossRef]

- Febri, O.N., Juminaa, D.S., Eti, N.S., 2016. Isolation and Antibacterial Activity Test of Lauric Acid from Crude Coconut Oil (Cocos nucifera L.). Procedia Chem: 18:132-40.

- Félix-Silva, J., Silva-Junior, A.A., Zucolotto, S.M., Fernandes- Pedrosa, M.D., 2017. Medicinal plants for the treatment of local tissue damage induced by snake venoms: an overview from traditional use to pharmacological evidence. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med: 2017:5748256. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A., Das, R., Sarkhel, S., Mishra, R., Mukherjee, S., Bhattacharya, S., 2010. Herbs and Herbal constituent active against snake bite. Indian journal of experimental biology. 48:865-878.

- Gong, J.X., He, Y., Cui, Z.H.L., Guo, Y.W., 2016. Synthesis, spectral characterization, and antituberculosis activity of thiazino[3,2-A]benzimidazole derivatives. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem: 191, 1036-41. [CrossRef]

- Guan, L., Yang, H., Cai, Y., Sun, L., Di, P., Li, W., Liu, G., Tang, Y., 2019. ADMET-score-a comprehensive scoring function for evaluation of chemical drug-likeness. MedChemComm. [CrossRef]

- Hamama, W.S., Waly, M.A., El-Hawary, I., Zoorob, H.H., 2016. Utilization of 2-Chloronicotinonitrile in the Syntheses of Novel Fused Bicyclic and Polynuclear Heterocycles of Anticipated Antitumor Activity. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 53, 953-957. [CrossRef]

- Han, X., Shen, T., Lou, H., 2007. Dietary polyphenols and their biological significance. Int J Mol Sci: 950-88. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, C.A., Lawson, K.R., Perkins, J., Urch, C.J., 2001. Aromatic interactions. Journal of the Chemical Society, Perkin Transactions 2. [CrossRef]

- Igwe, O.U., Okwu, D.E., 2013. GC-MS evaluation of bioactive compounds and antibacterial activity of the oil fraction from the stem bark of Brachystegia eurycoma Harms. Int J Chem Sci: 11:357-71.

- Ismail, A.A., Hasni, A., Mohammed, R.S., 2019. Methyl Elaidate: A Major Compound of Potential Anticancer Extract of Moringa oleifera Seeds Binds with Bax and MDM2 (p53 Inhibitor) In silico. Integrative Medicine Cluster, Advanced Medical and Dental Institute, Universiti Sains Malaysia.

- Johnson, T.O., Adegboyega, A.E., Johnson, G.I., Umedum, N.L., Bamidele, O.D., Elekan, A.O., Tarkaa, C.T., Mahe, A., Abdulrahman, A., Adeyemi, O.E., Okafor, D., Yusuf, A.J., Atewolara-Odule, O.C., Ogunmoye, A.O., Ishaya, T., 2022a. Uncovering the inhibitory potentials of Phyllanthus nivosus leaf and its bioactive compounds against Plasmodium lactate dehydrogenase for malaria therapy. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 0 (0), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Krishnaiah, D., Sarbatly, R., Nithyanandam, R., 2011. A review of the antioxidant potential of medicinal plant species. Food and Bioproducts Processing, 89(3): 217-233. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., Bajwa, B.S., Singh, K., Kalia, A.N., 2013. Anti-inflammatory activity of herbal plants: A review. Int J Adv Pharm Biol Chem 2 (2):272-281.

- Kumar, P.P., Kumaravel, S., Lalitha, C., 2010. Screening of antioxidant activity, total phenolics and GC-MS study of Vitex negundo. Afr J Biochem Res; 4:191-5.

- LaFleur, M.D., Lucumi, E., Napper, A.D., Diamond, S.L., Lewis, K., 2011. Novel high-throughput screen against Candida albicans identifies antifungal potentiators and agents effective against biofilms. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66, 820-826. [CrossRef]

- Lalitharani, S., Mohan, V.R., Regini, G.S., Kalidass, C., 2009. GC-MS analysis of ethanolic extract of Pothos scandens L. leaf. J. Herb. Medi. Toxicology: 3: 159-160.

- Leyva-Peralta, M.A., Robles-Zepeda, R.E., Garibay-Escobar, A., Ruiz-Bustos, E., Alvarez-Berber, L.P., Galvez-Ruiz, J.C., 2015. In vitro anti-proliferative activity of Argemone gracilenta and identification of some active components. BMC Complement Altern Med; 15:13. [CrossRef]

- Liang, X., Zhang, L., Zhang, X., Dai, W., Li, H., Hu, L., Liu, H., Su, J., Zhang, W., 2010. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of traditional Chinese medicine Niu Huang Jie Du Pill using ultra performance liquid chromatography coupled with tunable UV detector and rapid resolution liquid chromatography coupled with time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis; 51(3):565–571. [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C.A., 2004. Lead- and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. In: Drug Discovery Today: Technologies. [CrossRef]

- Lokeswari, N., Peela, S., 2011. Isolation of Tannins from Caesalpinia Coriaria and Effect of Physical Parameters, International Research Journal of Pharmacy, 2(2) 146-152.

- Maruthupandian, A., Mohan, V.R., 2011. GC-MS analysis of ethanol extract of Wattakaka volubilis (L.f) Stapf. Leaf. Int. J. Phytomedicine; 3: 59-62.

- Meenatchisundaram, S., Parameswari, G., Subbraj, T. 2008. Anti-venom activity of medicinal.

- Plants - a mini review. National institute of health (NIH). www.researchgate.net.

- Mitra, S., Mukherjee, S.K., 2014. Some plants used as antidote to snake bite in West Bengal, India. Divers Conserv Plants Trad Knowledge: 487-506.

- Murakami, M., Kudo, I., 2002. Phospholipase A2. The journal of biochemistry, 131(3), 285-292.

- Ntie-Kang, F., 2013. An in silico evaluation of the ADMET profile of the StreptomeDB database. Springerplus, 2, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Rhinde, S.S., Rode, M.A., Karale, B.K., 2010. Indian J. Pharm.Sci:72, 231-235.

- Rita, P., Animesh, D.K., Aninda, M., Benoy, G.K., Sandip, H., Datta, K., 2011. Snake bite, snake venom, anti-venom and herbal antidote-a review. Int J Res Ayurveda Pharm; 2:1060-7.

- Sani, I., Umar, A.A., Jiga, S.A., Bello, F., Abdulhamid, A., Fakai, I.M., 2020. Isolation Purification and Partial Characterization of Antisnake Venom Plant Peptide (BRS-P19) from Bauhinia rufescens (LAM FAM) Seed as Potential Alternative to Serum-Based Antivenin. Journal of Biotechnology Research, 6(4), 18-26. [CrossRef]

- Sheela, D., Dhanalakshmi, J., Selvi, S., 2013. Antibacterial and antifungal activity of lectin from.

- seeds of Pongamia glabra. Int. J. Curr. Biotech., 1 (8): 10-14.

- Shou, W.Z., 2020. Current status and future directions of high-throughput ADME screening in drug discovery. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis. [CrossRef]

- Sombié, P., Konate, K., Youl, E., Coulibaly, A.Y., Kiendrébéogo, M., Muhammad, I., 2013. GC-MS analysis and antifungal activity from galls of Guiera senegalensis J.F Gmel (Combretaceae). Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Sciences, 3(12), 6–12.

- Tan, N.H., Tan, C.S., 1988. Acidimetric assay for phospholipase A using egg yolk suspension as substrate. Anal. Biochem. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.M., O’Connor, P.D., Marshall, A.J., Francisco, A.F., Kelly, J.M., Riley, J., Read, K.D., Perez, C.J., Cornwall, S., Thompson, R.C.A., Keenan, M., White, K.L., Charman, S.A., Zulfiqar, B., Sykes, M.L., Avery, V.M., Chatelain, E., Denny, W.A., 2020. Re-evaluating pretomanid analogues for Chagas disease: Hit-to-lead studies reveal both in vitro and in vivo trypanocidal efficacy. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 207. [CrossRef]

- Winston, J.C., 1999. Health-promoting properties of common herbs. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 70(3): 491-499.

- Yff, B.T., Lindsey, K.L., Taylor, M.B., Erasmus, D.G., Jäger, A.K., 2002. The pharmacological screening of Pentanisia prunelloides and the isolation of the antibacterial compound palmitic acid. J Ethnopharmacol; 79(1):101-7. PMID 11744302. [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, A.J., Abdullahi, M.I., Musa, A.M., Abubakar, H., Amali, A.M., Nasir, A.M., 2021. Potential Inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 from Neocarya macrophylla (Sabine) Prance ex F. White: Chemoinformatic and Molecular Modeling Studies for Three Key Targets. TurkJ Pharm Sci Vol. 19 (2), pp 202-212. 96.

- Yusuf, A.J., Abdullahi, M.I., Musa, A.M., Haruna, A.K., Mzozoyana, V., Biambo, A.A., Abubakar, H., 2020a. A bioactive flavan-3-ol from the stem bark of Neocarya macrophylla. Scientific African 7. [CrossRef]

- Yuriev, E., Ramsland, P.A., 2013. Latest developments in molecular docking: 2010- 2011, Journal of Molecular Recognition, 26, 215.

| S/N | Compound Name | Compound ID | Docking scores |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bis(m-phenoxyphenyl) ether | 69781 | -8.7 |

| 2 | Phenol, 4, 4’ –methylenebis[ 2,6-dimethyl- | 79345 | -8.6 |

| 3 | Bis(p-phenoxyphenyl) ether | 631944 | -8.4 |

| 4 | 6-(4-ethylphenyl)-2-phenylimidazo[1,2-b][1,2,4]triazine | 627189 | -8.4 |

| 5 | Kaempferol | 5280863 | -8.4 |

| 6 | Apigenin | 5280443 | -8.4 |

| 7 | 2-Methyl-7-phenylindole | 610181 | -8.2 |

| 8 | 3-(4-nitrophenylamino) Indole | 3755607 | -8.1 |

| 9 | 6-Chloro-4-phenyl-2-propylquinolin | 620147 | -7.8 |

| 10 | 6-Methyl-2-(3-nitrophenyl) imidazo [1, 2-a] pyridine | 620074 | -7.8 |

| 11 | Cyclohexyl Cyclooctane | 543869 | -7.5 |

| 12 | 2-Ethylacridine | 610161 | -7.4 |

| 13 | Cyclohexane | 143214 | -7.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).