1. Introduction

Diarrheal diseases (DDs) pose a significant challenge in developing nations and are responsible for the deaths of millions of people each year [

1]. Diarrhea can be described as a change in typical bowel movement and is attributed to an increase in water content, volume, or stool rate [

2]. The global population under the age of five is facing one in ten deaths, making up to approximately 8,00,000 deaths per year [

3]. There are 2.8 billion incidents of diarrhea in children (> 5 years of age), adults, and adolescents [

4]. Multiple influential factors are implicated in the pathophysiology of diarrhea, including poor intestinal absorption, gut motility, hypersensitivity of the stomach, susceptibility to microbial infection, metabolic insufficiency, genetic predisposition, irritation caused by chemicals, a weak immune system, and a plethora of secretory stimuli, such as bacterial enterotoxins, hormones, dihydroxy bile acids, hydroxylated fatty acids and inflammatory cytokines [

5]. Effective treatment strategies and preventive measures for treating diarrheal infections should include continuous breastfeeding, oral electrolyte rehydration therapy, maintenance of better hygiene, zinc supplementation, immunization programmes, and antibiotics [

6]. Plants are vital sources of new drug molecules. A myriad of plant species are still being investigated for constituents with medicinal activity. Therapeutic plants are an auspicious source of antidiarrheal drugs and molecules [

7]. Compounds such as 1,8-cineole, friedelin, stachysrosane (1), stachysrosane (2), and apigenin have potent antidiarrheal activity and are plant-derived compounds [

8]. For this reason, the World Health Organization (WHO) has encouraged studies relating to the remedy and preclusion of diarrheal diseases using traditional medical practices [

9,

10].

Plant-derived substances have long been used as reliable origins of various biologically active metabolites that are rich in numerous pharmacological agents. Nearly 80% of men, especially those from developing and underdeveloped countries, rely directly or indirectly on plant-based medications from traditional sources [

11,

12]. Natural substances from plant sources have advantages over synthetic molecules because of their better drug likeness and friendliness to the body’s biological system, allowing them to be better postulants for potential research and drug development [

13,

14].

Operculina turpethum (L.) belongs to the Convolvulaceae family and is a formidable therapeutic plant known for its use in both Unani and Ayurvedic practices. This indigenous Asian plant resides in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, China, Taiwan, and Myanmar [

15]. In traditional Unani practice,

O. turpethum roots are prescribed for conditions such as colic constipation paralysis, helminthiasis, gastropathy, ascites, leucoderma, pruritis, ulcers, and hemorrhoids [

16]. The

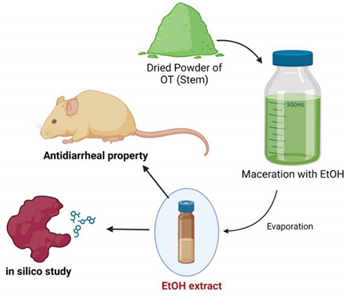

O. turpethum stem is rich in phenols, flavonoids, phytosterols, terpenoids, and cardiac glycosides [

17]. To date, four natural metabolites have been isolated from the chloroform extract of the stem of this plant, namely, β-sitosterol-β-D-glucoside, 22,23-dihydro-α-spinosterol-β-D-glucoside and salicylic acid [

18,

19] and 3-(4-hydroxy-phenyl)-2-(4-hydroxy phenyl)-ethyl]-acrylamide [

20] (

Figure 1). According to our literature search, no study has been conducted on the antidiarrheal activity of

O. turpethum stems until recently, providing the rationale

for conducting in vivo and

in silico assessments of the ethanolic extract of the stem.

2. Materials and Methods

Drugs and Chemicals

We acquired ethanol from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) and Tween 80 from BDH Chemicals Limited. The standard drug loperamide (produced by Square Pharmaceuticals Ltd.) was obtained from a local pharmacy. and castor oil was procured from a neighboring chemical market. All the chemicals and drugs employed in this study met the analytical standards.

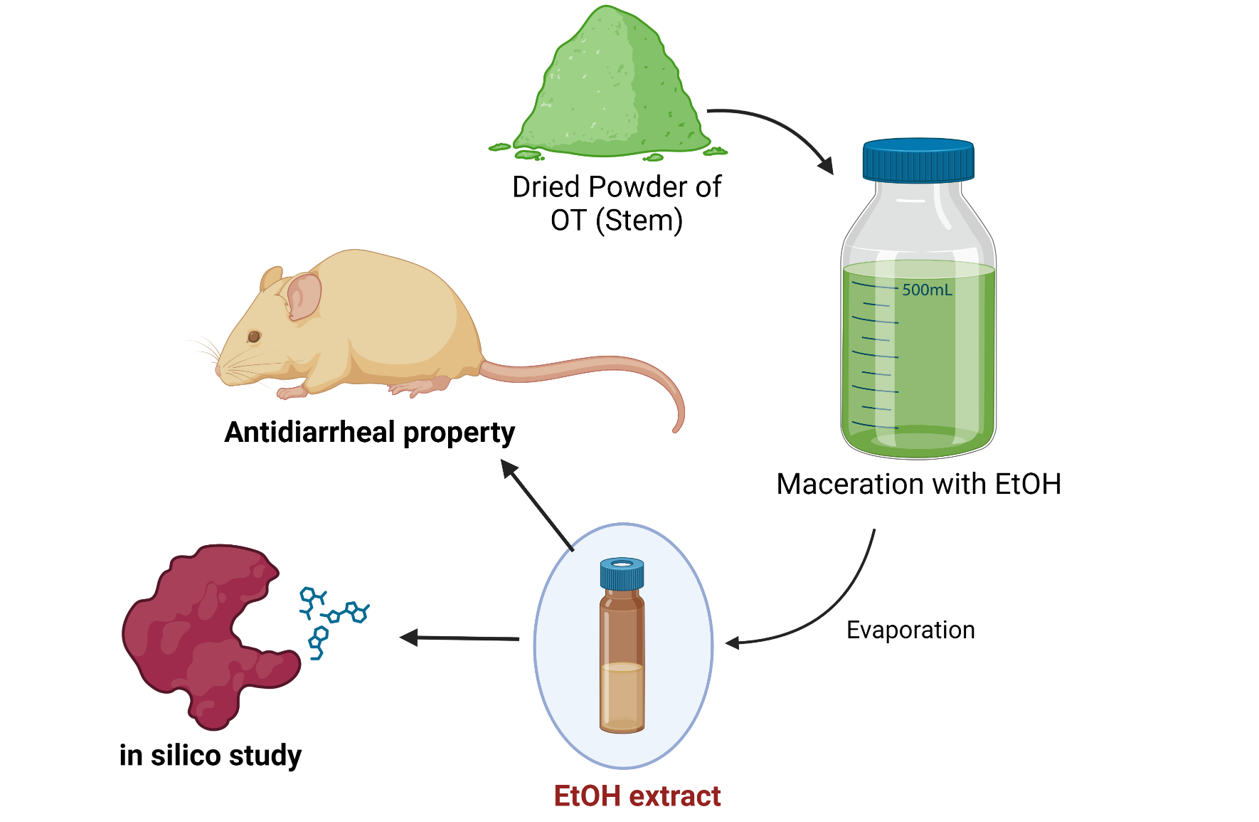

Plant Collection, Identification, and Preparation of the Ethanol Extract

For the present investigation, O. turpethum stems were collected from the campus of Khulna University and its surrounding area, and the plant was identified by experts at the Bangladesh National Herbarium, Mirpur, Dhaka, where a voucher specimen was submitted (voucher specimen no. 46484 DACB) for future reference. A total of 210 gm of ground dry powder of O. turpethum was taken into a flat-bottomed glass container, which was cleaned properly and submerged in 800 ml of 96% ethanol. The container was then corked, sealed appropriately and stored for 14 days. Occasional shaking and stirring were performed between these two periods. Coarse filtration of the whole mixture was performed by utilizing a piece of thoroughly cleaned cloth succeeded by filtration using Whatman no. 1 filter paper. Eventually, the filtrate was evaporated via a rotary evaporator to yield the ethanolic extract of the O. turpethum stem. The extract had a yield of 3.58% and was stored in a refrigerator at 4°C for further analysis.

Experimental Animals

To conduct the in vivo assessment, we used Swiss albino mice, which were aged approximately 4 –6 weeks and weighed approximately 22-28 gm. The mice were procured from the animal research branch of the International Centre for Diarrheal Disease and Research, Bangladesh (ICDDRB). Mice were kept under standard laboratory conditions for one week to ensure better adaptation. All the experimental animals were given standard laboratory food and clean tap water and were maintained within a natural day‒night cycle. The whole experiment was performed in the noiseless and isolated pharmacological laboratory of Pharmacy Discipline, Khulna University, Khulna-9208, Bangladesh. The experiment was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Khulna University [Ref: KUAEC-2018-01-08].

Antidiarrheal Activity Assessment in Patients with Castor Oil-Induced Diarrhea

A method previously described by [

1] was followed in this study. Initially, all the mice were monitored for diarrhea by administering 0.5 ml of castor oil. After administration, only the mice that exhibited diarrhea were considered for the final experiment. The four groups were as follows: control (1% Tween 80 in water, 10 mL/kg body weight oral dose), positive control (loperamide, 3 mg/kg body weight oral dose), test-I (OT, 250 mg/kg body weight oral dose), and test-II (OT, 500 mg/kg body weight oral dose). The mice were subsequently split according to the groups. All four groups contained five mice in each group. Each animal was kept in a separate cage, while the blotting paper was lined with the floor. After every hour, the floor lining was altered. Thirty minutes after the above treatments, diarrheal induction was conducted via oral administration of 0.5 ml of castor oil to each mouse. The mice were closely observed for 4 h. During this time, the total amount of fecal output and amount of diarrheal feces were recorded. The percentage inhibition of diarrhea (%) was calculated in comparison with that of the negative control group by manipulating the following equation: inhibition (%) = [(TD control – TD test groups)/TD control] × 100, where TD control represents the total number of diarrheal feces of the negative control group and TD test groups represents the total number of diarrheal feces of either the test groups or the standard drug.

Selection of Compounds for the Molecular Docking Study

β-Sitosterol-β-D-glucoside, 22,23-dihydro-α-spinosterol-β-D-glucoside, salicylic acid, and 3-(4-hydroxy-phenyl)-N-[2-(4-hydroxy phenyl)-ethyl]-acrylamide were selected for molecular docking studies [

18,

19,

21]. The chemical structures of the compounds were downloaded from the PubChem database.

Preparation of the Ligands

Of the five ligands, four, 3-(4-hydroxy-phenyl)-N-[2-(4-hydroxy phenyl)-ethyl]-acrylamide (PubChem CID: 5372945), loperamide (PubChem CID: 3955), salicylic acid (PubChem CID: 338) and β-sitosterol-β-D-glucoside (PubChem CID: 5742590), were downloaded from PubChem (

https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) [

22]. The 3D structure of 22,23-dihydro-a-spinosterol-ß-D-glucoside was drawn in Avogadro (Avogadro: an open-source molecular builder and visualization tool, Version 1.2.0

http://avogadro.cc/) due to unavailability of the mentioned structure. The drawn structure mimics the 2D structure depicted in other studies [

19]. After that, all the ligands were optimized using the same program, Avogadro, where the universal force field (UFF) was employed during the process. Finally, the ligands were saved in .pdb (Protein Data Bank) format and used for docking.

Preparation of the Protein

The M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (PDB ID: 4U14) [

23] was obtained from the ‘Protein Data Bank’ (

http://www.rcsb.org/) [

24]. The downloaded protein was cleaned with PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.0 Schrödinger, LLC) and then optimized with Swiss-PdbViewer (Swiss-PdbViewer/DeepView, v4.1 by Nicolas Guex, Alexandre Diemand, Manuel C. Peitsch, & Torsten Schwede).

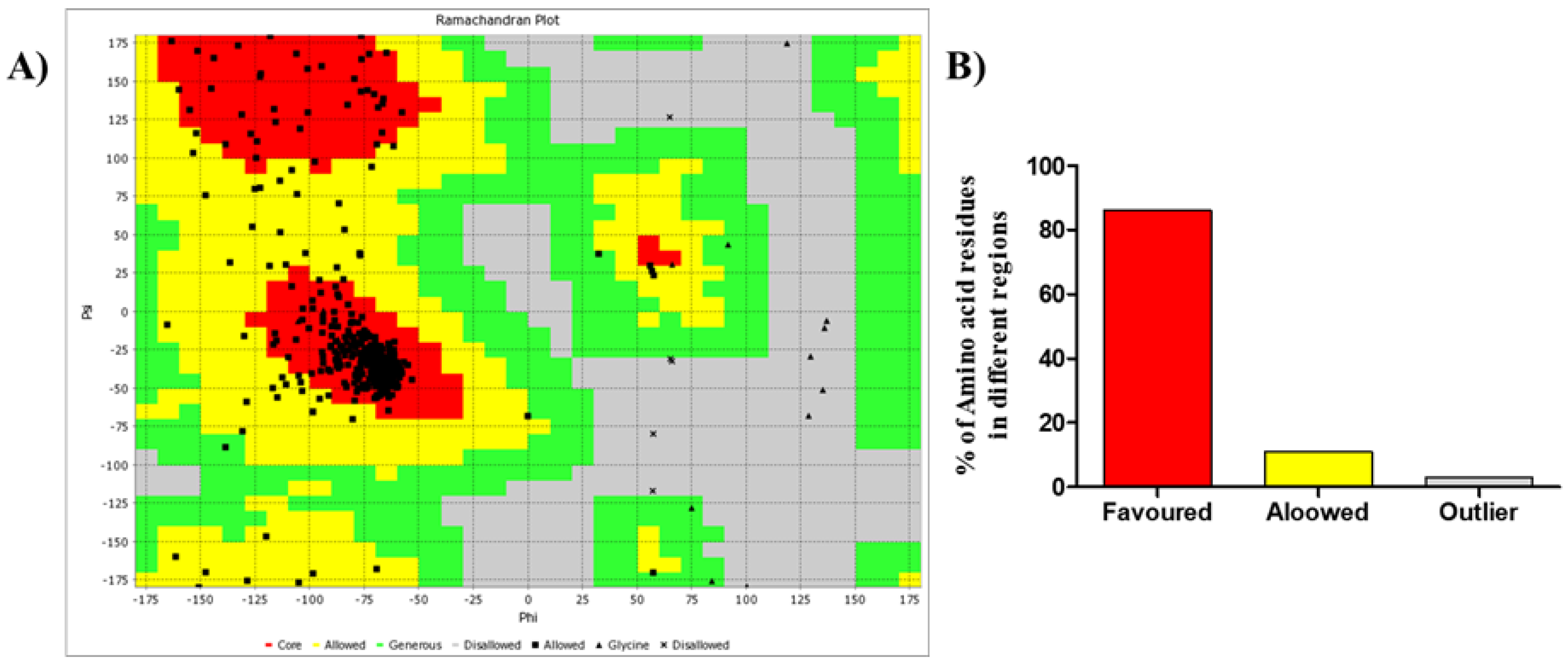

Validation of the Protein Structure

By using criteria such as preferred, allowed, and outside amino acid residue locations, Ramachandran plots were generated using the VADAR server to validate the predicted protein structures.

Molecular Docking and Visualization

Molecular docking between the receptor and the ligands (separately) was performed using the ‘Vina Wizard’ program in PyRx – Python Prescription 0.8 [

25]. The ligands (separately) and the receptor were loaded into the program with the proper declaration of the compound, i.e., ligand or macromolecule.

Afterward, the docked ligands (separately) and the receptor were combined with PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.0 Schrödinger, LLC). For visualization, each combined structure was opened with Discovery Studio (BIOVIA, Dassault Systèmes, Discovery Studio Visualizer, v4.5.0.15071, San Diego: Dassault Systèmes, ©2005-15). The ligand interactions were observed, and snapshots were taken of the best poses.

Pharmacokinetic Parameters

Basic pharmacokinetic parameters were analyzed with the SwissADME web server (

http://www.swissadme.ch/) to assess the probability of drug use [

26]. SMILES or structures were used as input, and the SwissADME program was used.

Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism software (version 8, USA) was used to analyze all the experimental data, and the data are presented as the mean ± SEM (standard error of the mean). Here, P values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

3. Results

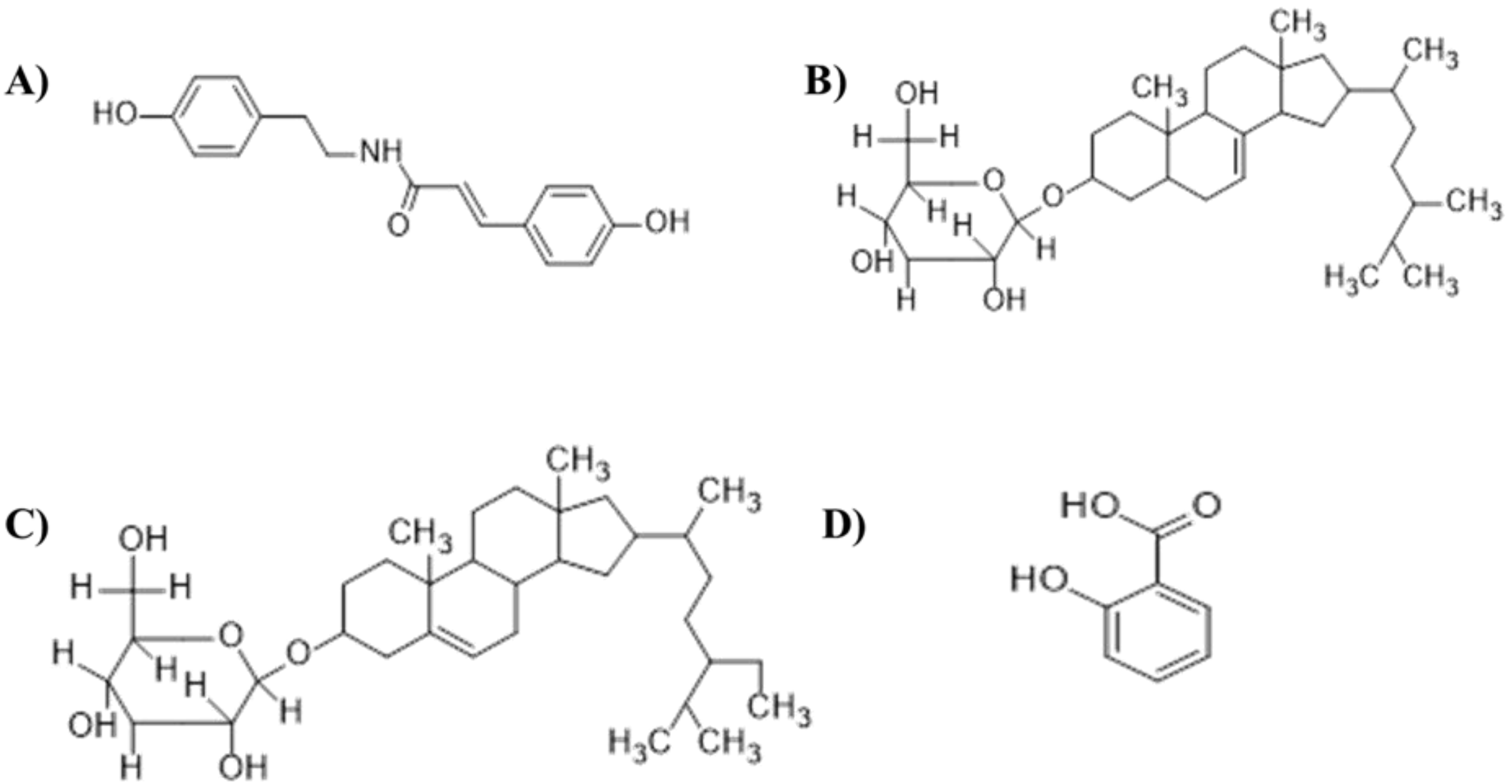

Castor Oil-Induced Diarrhea

The ethanolic OT stem extract dose-dependently demonstrated significant antidiarrheal activity, especially at a dose of 500 mg/kg (

Table 1). The inhibition of defecation was almost 51% (

Figure 2B) for the 500 mg/kg dose, for which the mean latency period was 134±3.7 min (

Figure 2A), which is comparable with that of the standard drug loperamide, which resulted in 89% inhibition of defecation, with a mean latency period of 153±3.11 min. Similarly, the inhibitory effect of the 250 mg/kg dose was approximately 31%, with a mean latency period of 80±2.07 min.

Molecular Docking Study

Loperamide was used as the standard for this docking study. Ramachandran plot (

Figure 3A) of the M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (PDB ID. 4U14) contained 86% amino acids in the favored region, 11% in the allowed region, and 3% in the generously allowed or disallowed region (

Figure 3B). This finding suggested that the protein is favorable for molecular docking studies. The docking was then carried out with a maximized grid box dimension (

Table 2).

Upon completion of the process, the resulting data were obtained along with the docked structures.

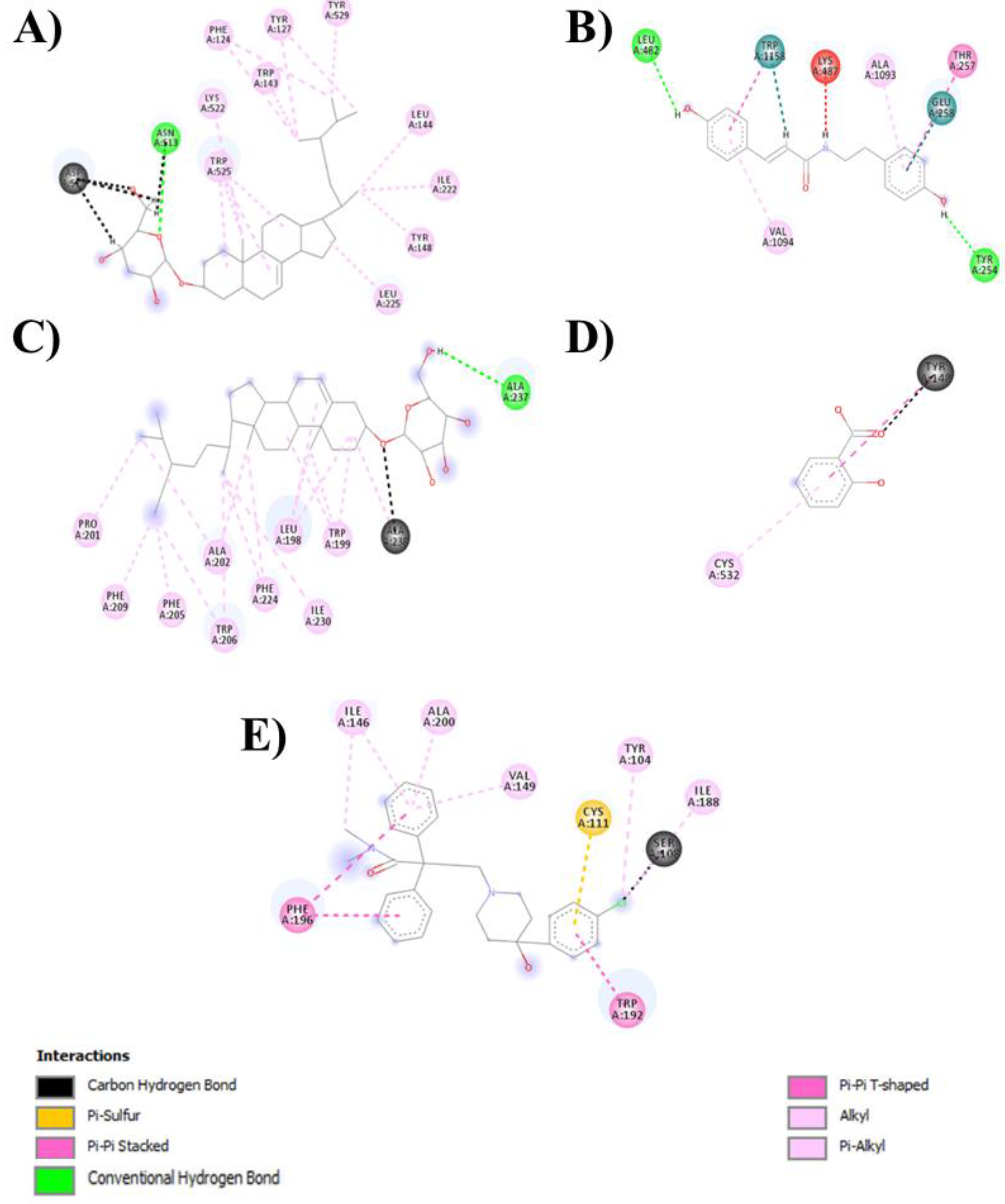

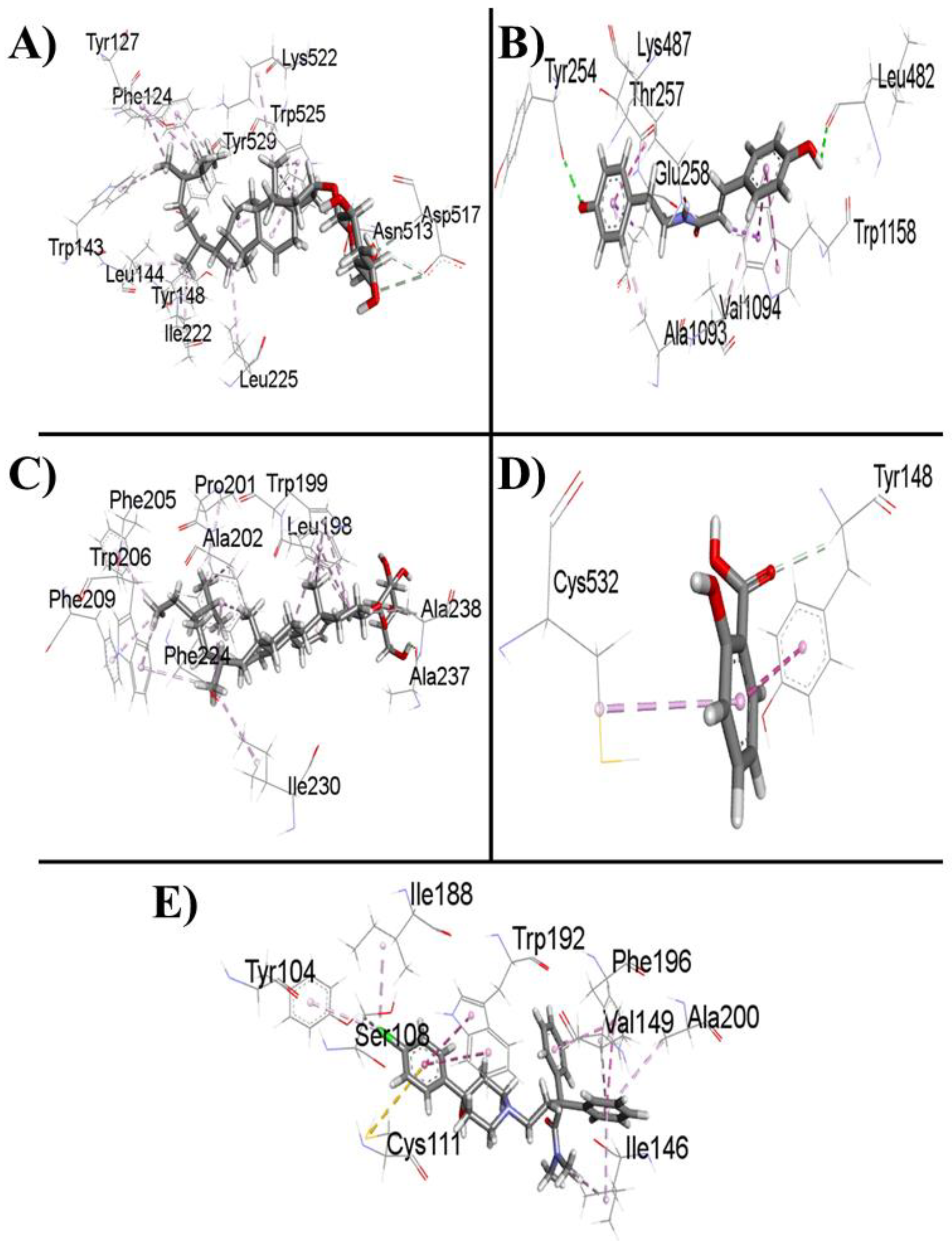

Table 3 shows the data for the docked complexes with the lowest binding energies with the corresponding amino acid of the receptor, revealing the best-docked complex for each ligand.

Loperamide binds to the M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor and has a binding energy of -8.3 kcal/mol. All the ligands except for salicylic acid showed satisfactory interactions with the receptor and thus inhibited M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor activity. If all the ligands are kept in descending order according to their success in binding with the receptor, 22,23-dihydro-α-spinosterol-ß-D-glucoside will be at the top, followed by 3-(4-hydroxy-phenyl)-N-[2-(4-hydroxy phenyl)-ethyl]-acrylamide, loperamide, β-sitosterol-β-D-glucoside, and salicylic acid respectively.

Thus, it can be conjectured that 22,23-dihydro-α-spinosterol-ß-D-glucoside is the best candidate among the four ligands. 3-(4-Hydroxy-phenyl)-N-[2-(4-hydroxy phenyl)-ethyl]-acrylamide performs slightly less than the former but outperforms the standard drug loperamide. β-Sitosterol-β-D-glucoside performed marginally less than the standard, although the binding affinities of both of the compounds were similar. In contrast, salicylic acid may not be a potential candidate for use as an antidiarrheal agent, as its binding affinity is considerably less than that of the standard.

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show the 2D and 3D interactions between the ligands and the protein, respectively.

4. Discussion

The ethanolic OT stem extract was verified for its possible antidiarrheal effect on mice, and the results showed that

O. turpethum significantly attenuated diarrhea induced by castor oil in comparison with the marketed drug loperamide. The phytochemicals that are present in

O. turpethum stems, i.e., phenols, flavonoids, phytosterols, terpenoids, and cardiac glycosides [

17], are well known to possess antidiarrheal properties [

27,

28]. Flavonoids, tannins [

29] and saponins [

30] have been implicated in the calcium channel blocking (CCB) effect. This might also explain its therapeutic use in treating diarrhea.

Hydrolysis of castor oil results in the formation of ricinolic acid in the gastrointestinal tract, which in turn induces diarrhea in mice [

31], alters water and electrolyte transport, and causes a hypersecretory response and massive contraction of the intestine [

32]. Thus, phytochemicals present in EEOT may exert this particular effect by hindering gut motility as well as electrolyte outflux. Compared with that of loperamide, the effect of EEOT stem extract on diarrhea was quite acceptable (

Table 1), suggesting that EEOT has an inhibitory effect on gut motility or electrolyte outflux. To further confirm the possible inhibitory effect of OT on gut motility, we used four previously isolated compounds, namely, 22,23-dihydro-α-spinosterol-ß-D-glucoside, 3-(4-hydroxy-phenyl)-N-[2-(4-hydroxy phenyl)-ethyl]-acrylamide, β-sitosterol-β-D-glucoside, and salicylic acid, for

in silico studies.

A summary of the pathological process of diarrhea concerning gut motility has shown the association of the M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor [

33]. The autonomic parasympathetic nerves are responsible for controlling the activity of multiple organs in the body. Anticholinergic drugs relieve gastrointestinal and urinary tract troubles by decreasing intestinal and bladder muscle spasms [

34]. The M3 subtype of the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (MAChR) is competitively antagonized by anticholinergic drugs. The M3 MAChR is a member of the G protein-coupled receptor family that eases the response to acetylcholine [

35] and effectuates an increase in the intracellular calcium ion, which usually leads to shrinkage of smooth muscles [

36]. The contraction of smooth muscles is dependent upon an increase in cytoplasmic free calcium ions, which activate contractile elements [

37]. Therefore, an antagonist of this receptor decreases constriction and free calcium ion reflux to provide an antidiarrheal effect. These are the important considerations that we had to keep in mind when we chose this particular receptor to dock with our four ligands as well as the standard drug loperamide. Among the four compounds, 22,23-dihydro-α-spinosterol-ß-D-glucoside, 3-(4-hydroxy-phenyl)-N-[2-(4-hydroxy phenyl)-ethyl]-acrylamide, and β-sitosterol-β-D-glucoside exhibited excellent binding affinity with the M3 muscarinic receptor. Therefore, these compounds may exert significant antidiarrheal effects by inhibiting the M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (PDB ID: 4U14) and blocking free calcium ion reflux in the cytoplasm. Conversely, salicylic acid may not be a potential inhibitor of the M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor, but the presence of salicylic acid in the stem may play a synergistic role because it can competitively inhibit prostaglandin formation [

38]. Prostaglandins cause contractions in the intestines to produce a range of GI disorders, including diarrhea [

39].

We noticed from the ADME analysis of all four compounds that only 3-(4-hydroxy-phenyl)-N-[2-(4-hydroxy phenyl)-ethyl]-acrylamide satisfied Lipinski’s rule of five, the Ghose rule, the Veber rule, the Egan rule, and the Muegge rule and was considered a potential drug-like molecule. This compound is easier to synthesize than the other two molecules and has a good GI absorption rate.

Author Contributions

Md Abdullah Al Fahad: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Md. Fahim Hasan: Data curation, methodology, formal analysis. Md Arman Islam: Writing – review & editing. Nusrat Jahan: Writing – review & editing. Iqbal Ahmed: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, validation, Project administration, Conceptualization.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are provided within the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shoba, F.G. and M. Thomas, Study of antidiarrhoeal activity of four medicinal plants in castor-oil induced diarrhoea. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 2001. 76(1): p. 73-76. [CrossRef]

- Guerrant, R.L., et al., Practice guidelines for the management of infectious diarrhea. Clinical infectious diseases, 2001. 32(3): p. 331-351. [CrossRef]

- Kotloff, K.L., et al., Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. The Lancet, 2013. 382(9888): p. 209-222. [CrossRef]

- Walker, C.F. and R.E. Black, Diarrhoea morbidity and mortality in older children, adolescents, and adults. Epidemiology & Infection, 2010. 138(9): p. 1215-1226. [CrossRef]

- Bouma, G. and W. Strober, The immunological and genetic basis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature reviews immunology, 2003. 3(7): p. 521-533. [CrossRef]

- Shah, D., et al., Promoting appropriate management of diarrhea: a systematic review of literature for advocacy and action: UNICEF-PHFI series on newborn and child health, India. Indian pediatrics, 2012. 49(8): p. 627-649. [CrossRef]

- Maikere-Faniyo, R., et al., Study of Rwandese medicinal plants used in the treatment of diarrhoea I. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 1989. 26(2): p. 101-109. [CrossRef]

- Rawat, P., P.K. Singh, and V. Kumar, Evidence based traditional anti-diarrheal medicinal plants and their phytocompounds. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 2017. 96: p. 1453-1464. [CrossRef]

- Snyder, J.D. and M.H. Merson, The magnitude of the global problem of acute diarrhoeal disease: a review of active surveillance data. Bulletin of the world health organization, 1982. 60(4): p. 605.

- Lutterodt, G.D., Inhibition of gastrointestinal release of acetylchoune byquercetin as a possible mode of action of Psidium guajava leaf extracts in the treatment of acute diarrhoeal disease. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 1989. 25(3): p. 235-247. [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.J., G.M. Cragg, and K.M. Snader, Natural products as sources of new drugs over the period 1981− 2002. Journal of natural products, 2003. 66(7): p. 1022-1037. [CrossRef]

- Goyal, B.R., R.K. Goyal, and A.A. Mehta, PHCOG REV.: Plant Review Phyto-pharmacology of Achyranthes aspera: A Review. Pharmacognosy Reviews, 2007. 1(1).

- Minhajur, R.M., et al., The antimicrobial activity and brine shrimp lethality bioassay of leaf extracts of Stephania japonica (akanadi). Bangladesh Journal of Microbiology, 2011. 28(2): p. 52-56. [CrossRef]

- Borris, R.P., Natural products research: perspectives from a major pharmaceutical company. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 1996. 51(1-3): p. 29-38. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T., et al., A Review on Operculina turpethum: A potent herb of Unani system of medicine. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry, 2017. 6(1): p. 23-26.

- Aswal, B., et al., Screening of Indian plants for biological activity: Part X. 1984.

- Anju, V. and P. Radhamany, Pharmacognostic and phytochemical studies on Operculina turpethum (L) Silva Manso stem. World Journal of Pharma and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 2015. 4(7): p. 1920-1927.

- Harun-or-Rashid, H., et al., Antibacterial and cytotoxic activities of extracts and isolated compounds of Ipomoea turpethum. Pak J Biol Sci, 2002. 5: p. 597-9.

- Gupta, S. and A. Ved, Operculina turpethum (Linn.) Silva Manso as a medicinal plant species: A review on bioactive components and pharmacological properties. Pharmacognosy reviews, 2017. 11(22): p. 158. [CrossRef]

- Rashid Phd, M., et al., Biological activities of a novel acrylamide derivative from Ipomoea turpethum. Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences, 2002. 5: p. 968-969.

- Harun-ur-Rashid, M., et al., Biological activities of a new acrylamide derivative from Ipomoea turpethum. Pak J Biol Sci, 2002. 5(9): p. 968.

- Kim, S., et al., PubChem 2019 update: improved access to chemical data. Nucleic Acids Research, 2018. 47(D1): p. D1102-D1109. [CrossRef]

- Thorsen, T.S., et al., Modified T4 lysozyme fusion proteins facilitate G protein-coupled receptor crystallogenesis. Structure, 2014. 22(11): p. 1657-1664. [CrossRef]

- Berman, H.M., et al., The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Research, 2000. 28(1): p. 235-242.

- Dallakyan, S. and A.J. Olson, Small-molecule library screening by docking with PyRx. Methods Mol Biol, 2015. 1263: p. 243-50.

- Daina, A., O. Michielin, and V. Zoete, SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Scientific reports, 2017. 7: p. 42717. [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, A.K., et al., Antidiarrheal activity and phytochemical analysis of carica papaya fruit extract. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, 2017. 9(7): p. 1151.

- Galvez, J., et al., Antidiarrhoeic activity of Euphorbia hirta extract and isolation of an active flavonoid constituent. Planta medica, 1993. 59(04): p. 333-336. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z., et al., Effects of Total Flavonoids ofHippophae Rhamnoides L. on intracellular free calcium in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells of spontaneously hypertensive rats and Wistar-Kyoto rats. Chinese journal of integrative medicine, 2005. 11(4): p. 287-292. [CrossRef]

- Kai, L., Z. Wang, and J. Xiao, L-type calcium channel blockade mechanisms of panaxadiol saponins against anoxic damage of cerebral cortical neurons isolated from rats. Zhongguo yao li xue bao= Acta pharmacologica Sinica, 1998. 19(5): p. 455-458.

- Croci, T., et al., Role of tachykinins in castor oil diarrhoea in rats. British journal of pharmacology, 1997. 121(3): p. 375-380. [CrossRef]

- NU, R., et al., Presence of laxative and antidiarrheal activities in Periploca aphylla: A Saudi medicinal plant. International Journal of Pharmacology, 2013. 9(3): p. 190.

- Grover, M. and M. Camilleri, Ramosetron in irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea: new hope or the same old story? Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 2014. 12(6): p. 960-962.

- Memon, A.H., et al., Toxicological, Antidiarrhoeal and Antispasmodic Activities of Syzygium myrtifolium. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia, 2020. 30(3): p. 397-405. [CrossRef]

- Billington, C.K. and R.B. Penn, m3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor regulation in the airway. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology, 2002. 26(3): p. 269-272. [CrossRef]

- Goodman, L.S., Goodman and Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. Vol. 1549. 1996: McGraw-Hill New York.

- Karaki, H. and G.B. Weiss, Calcium release in smooth muscle. Life sciences, 1988. 42(2): p. 111-122.

- Peterson, D.A., et al., Salicylic acid inhibition of the irreversible effect of acetylsalicylic acid on prostaglandin synthetase may be due to competition for the enzyme cationic binding site. Prostaglandins and medicine, 1981. 6(2): p. 161-164. [CrossRef]

- Robert, A., et al., Enteropooling assay: a test for diarrhea produced by prostaglandins. Prostaglandins, 1976. 11(5): p. 809-828. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).