Submitted:

18 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

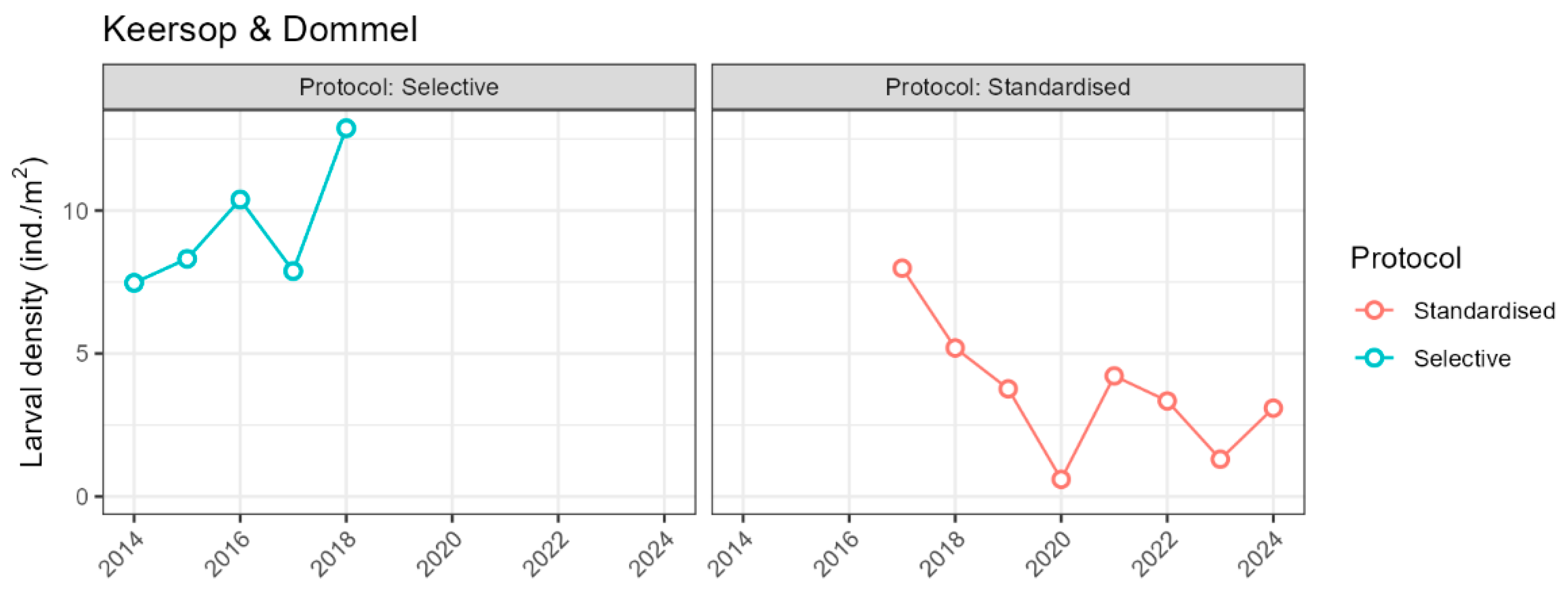

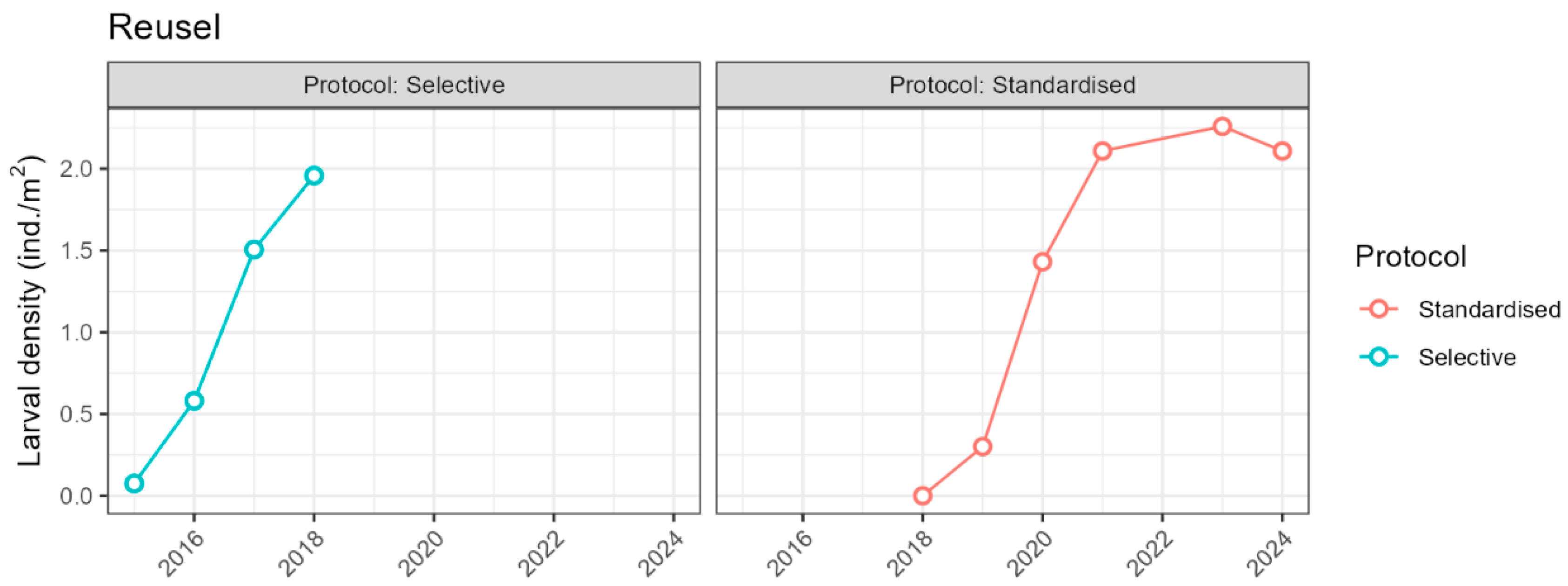

Brook lamprey (Lampetra planeri) became extinct in much of its former range in the south of the Netherlands. A reintroduction project from 2014 until 2018 aimed at the reestablishment of a population in the Reusel stream. Every year just over 1000 individuals (96% larvae, 4% adults) were translocated from the nearest population. Monitoring reveals that donor population was not jeopardized. The new population reproduces, larvae densities increased to >2 individuals per square meter in (sub) optimal habitat, larvae occur in different age groups and the distribution range expanded to 5 km. In 2024 the population is at the point of self-sustaining through natural reproduction. The new population judged by size, range and demographics is currently estimated to be ‘Vulnerable’, based on IUCN criteria. Due to a high probability of impact of droughts and therefore an increased extinction risk, the best available integrated estimate of population status would be ‘Endangered’. Monitoring remains essential to keep track of the development of the brook lamprey population and in steering ‘post reintroduction management’. The water system showed to be highly sensitive to progressive impacts from climate change and intensive land use. Further restoration of the watershed is extremely important to both nature and agriculture.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reintroduction Site Description

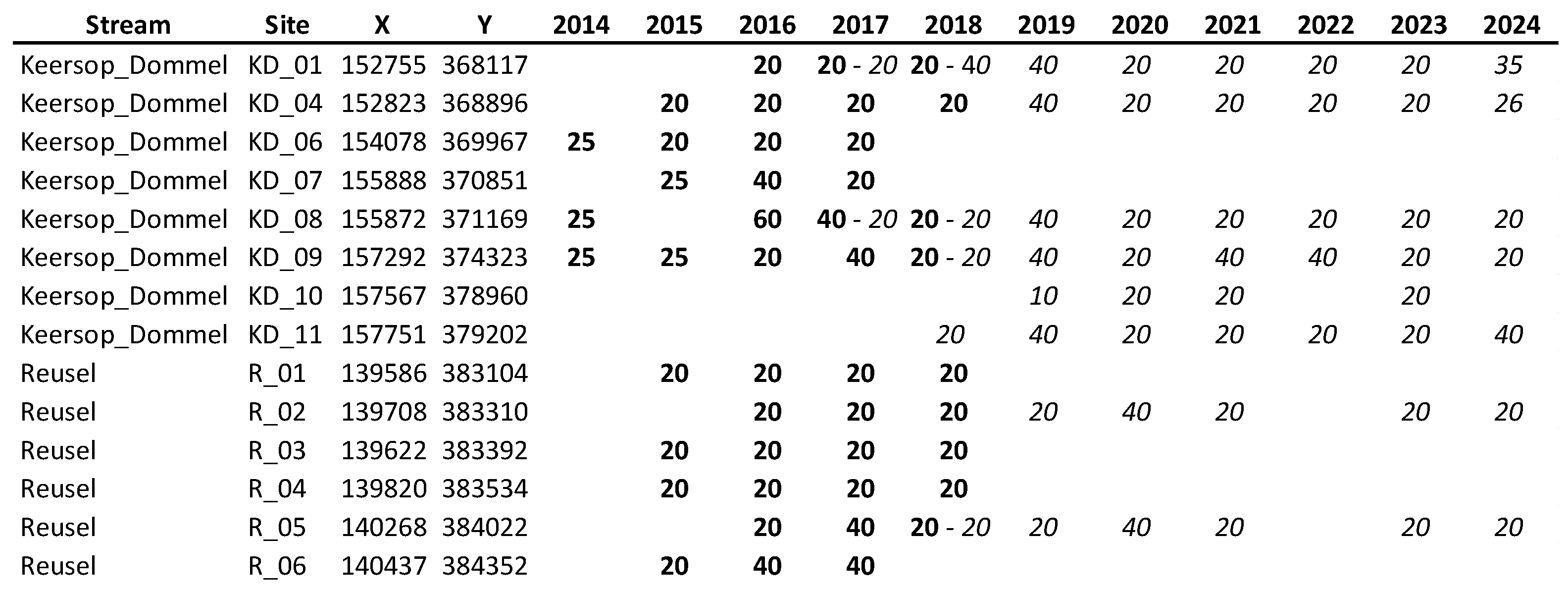

2.2. Reintroduction Protocol and Implementation

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Larvae Monitoring

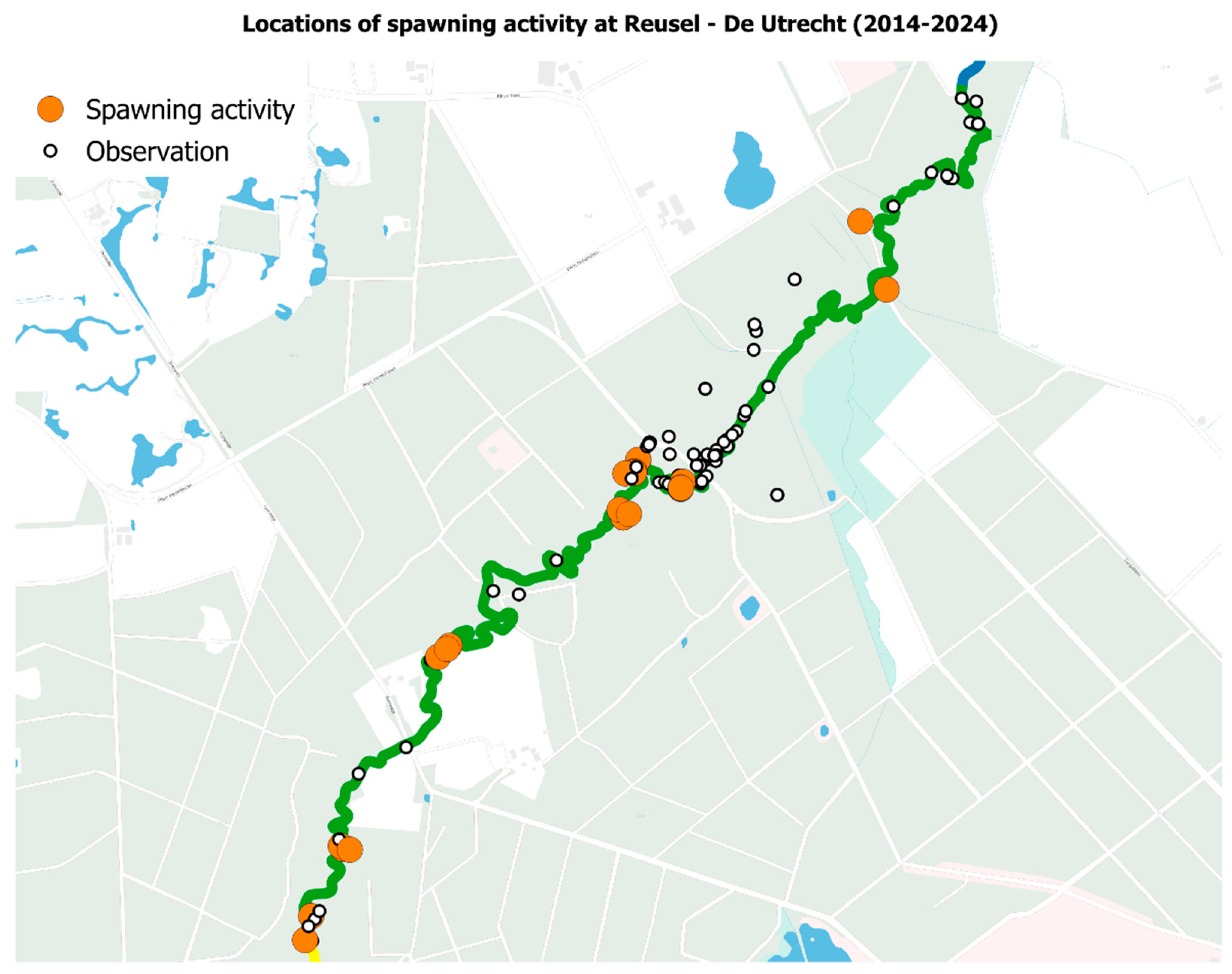

2.3.2. Spawning Surveys

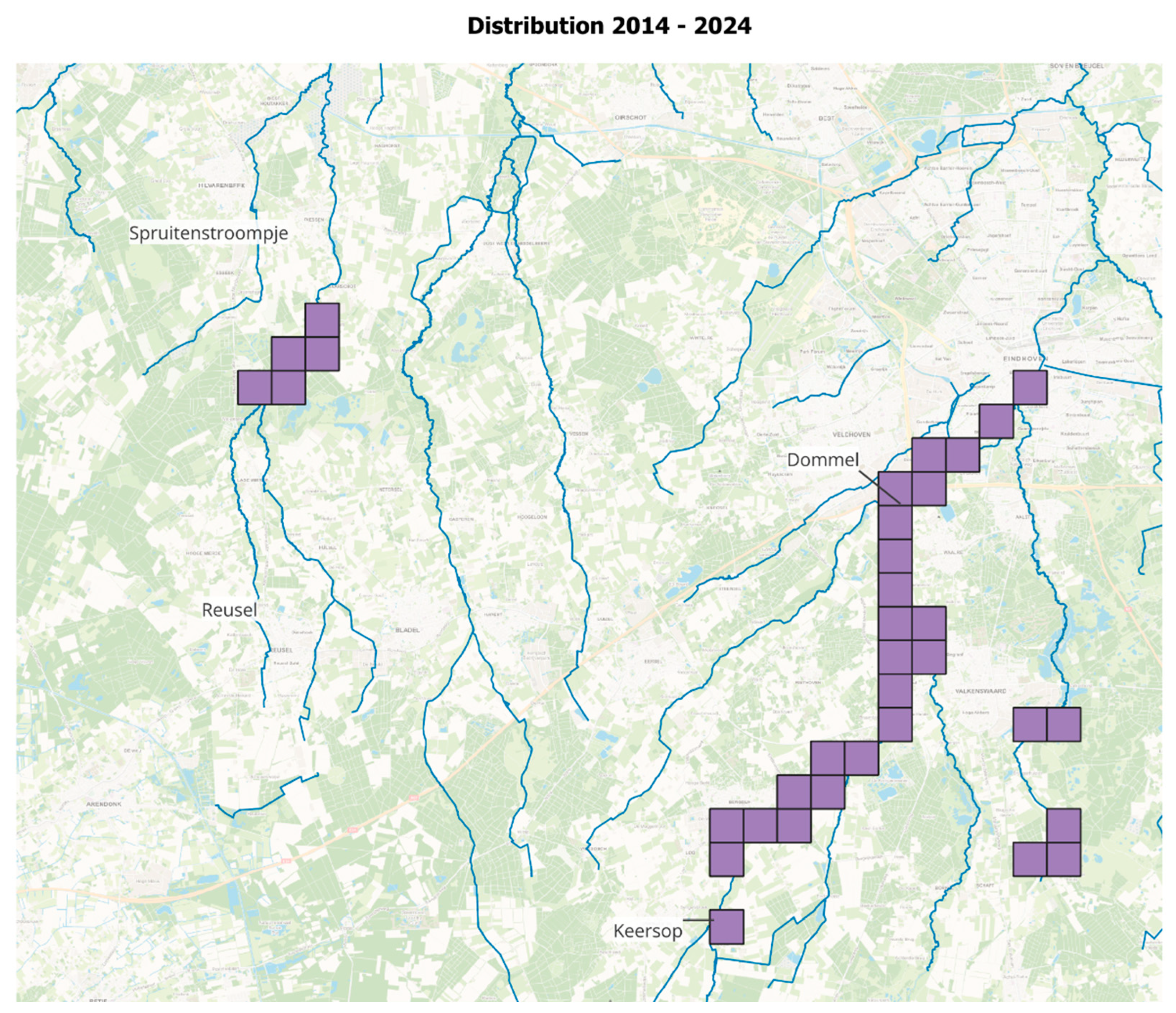

2.3.3. Observations on Distribution Range

2.4. Data Analysis

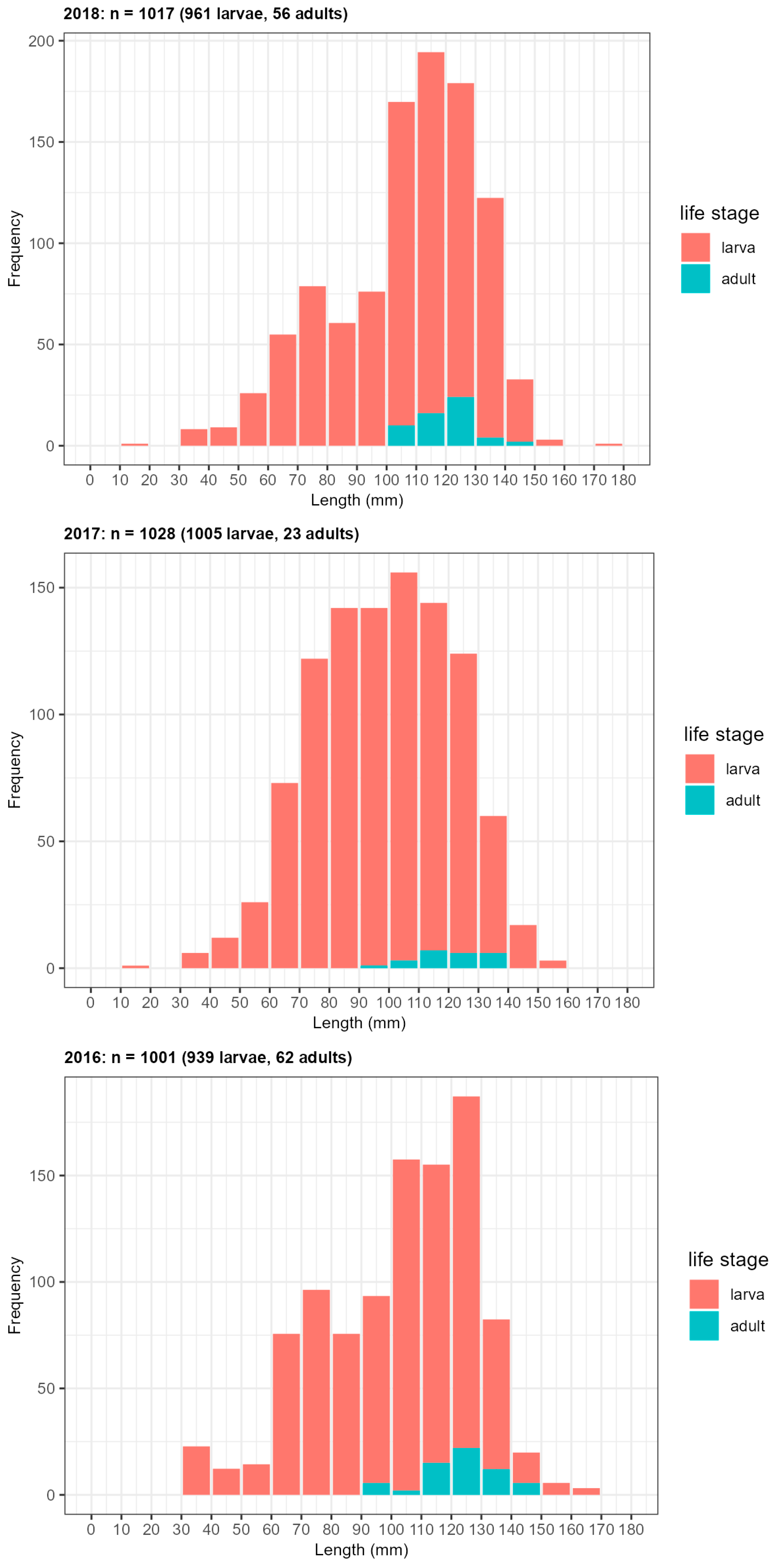

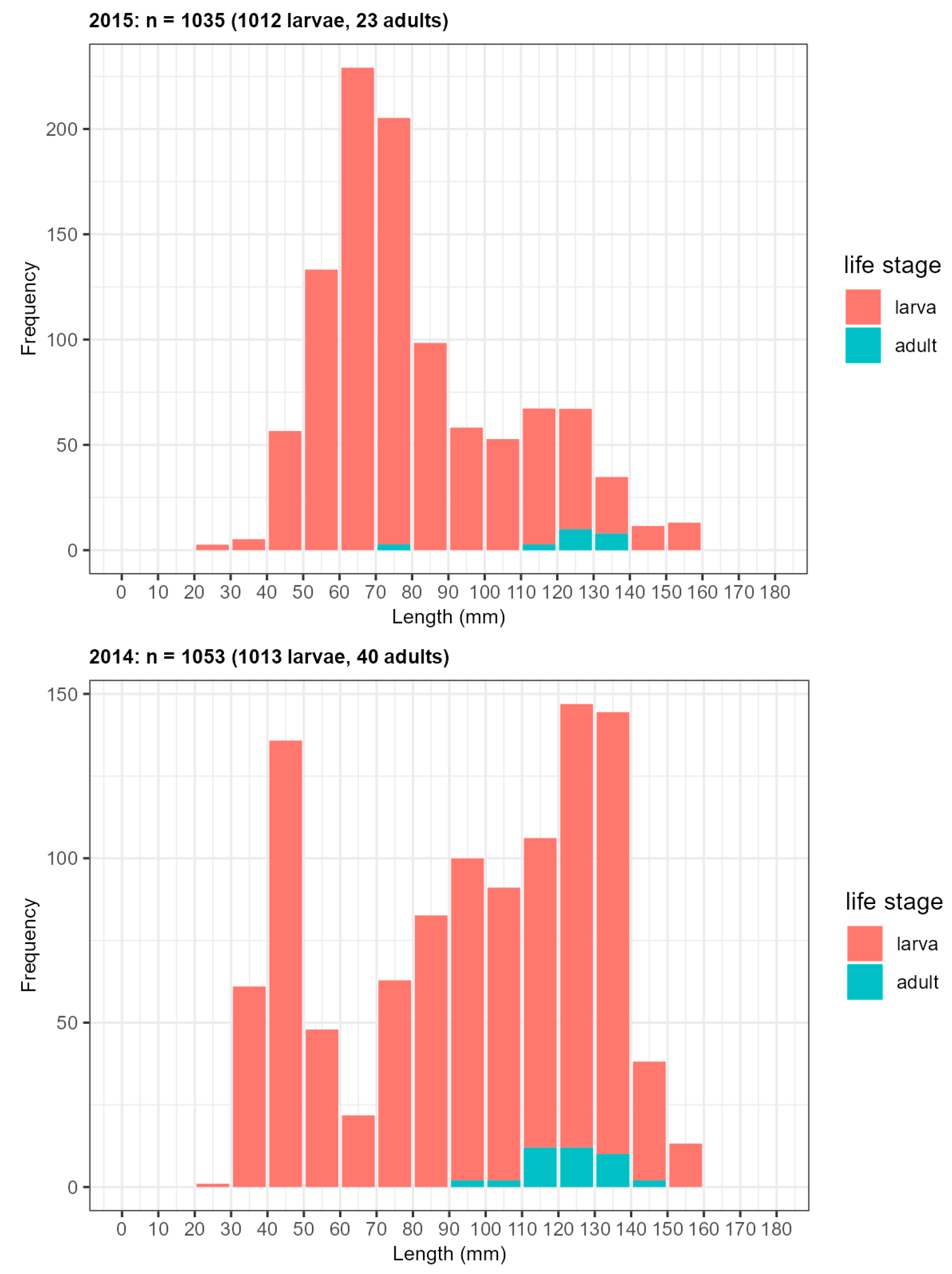

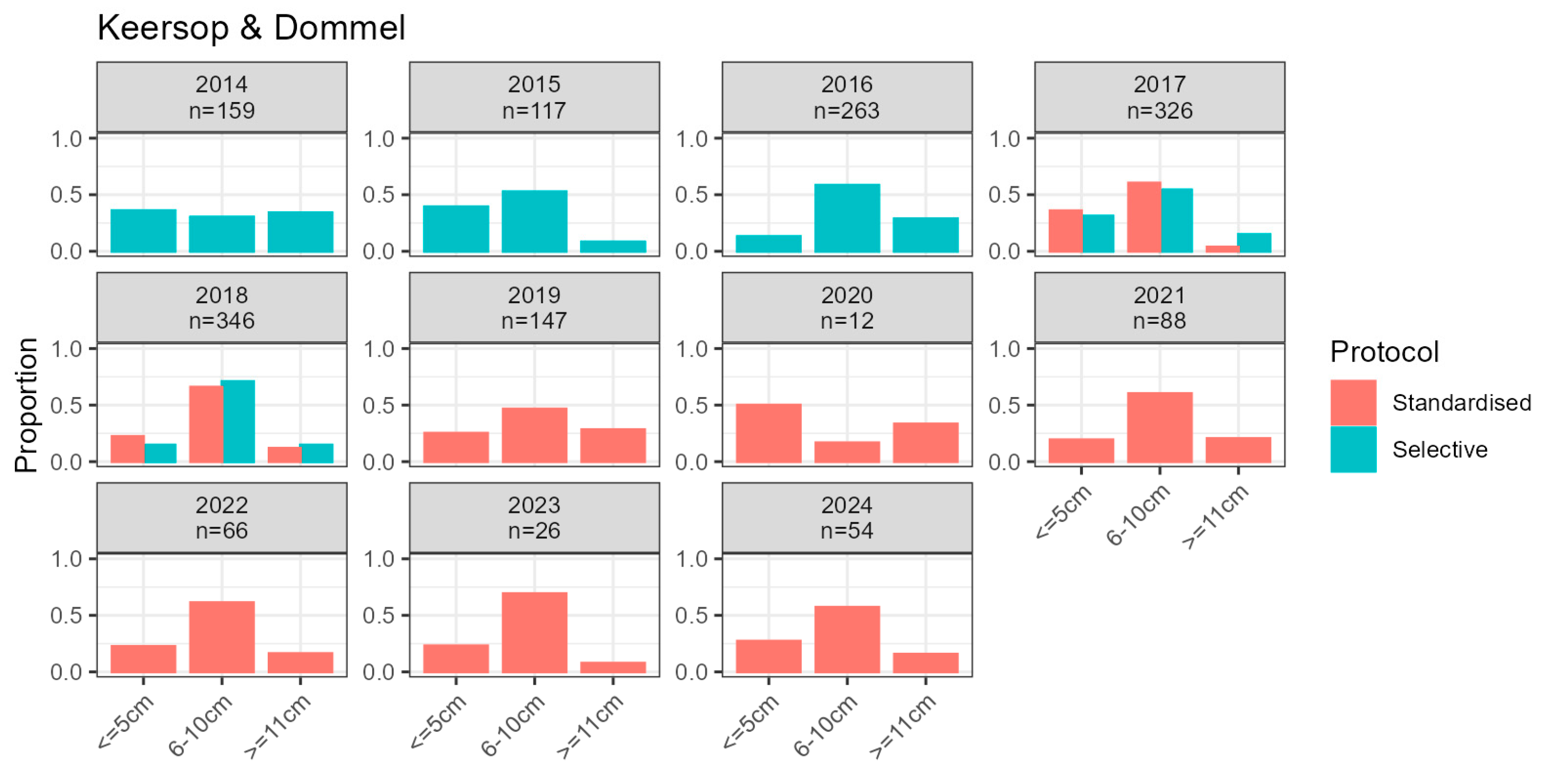

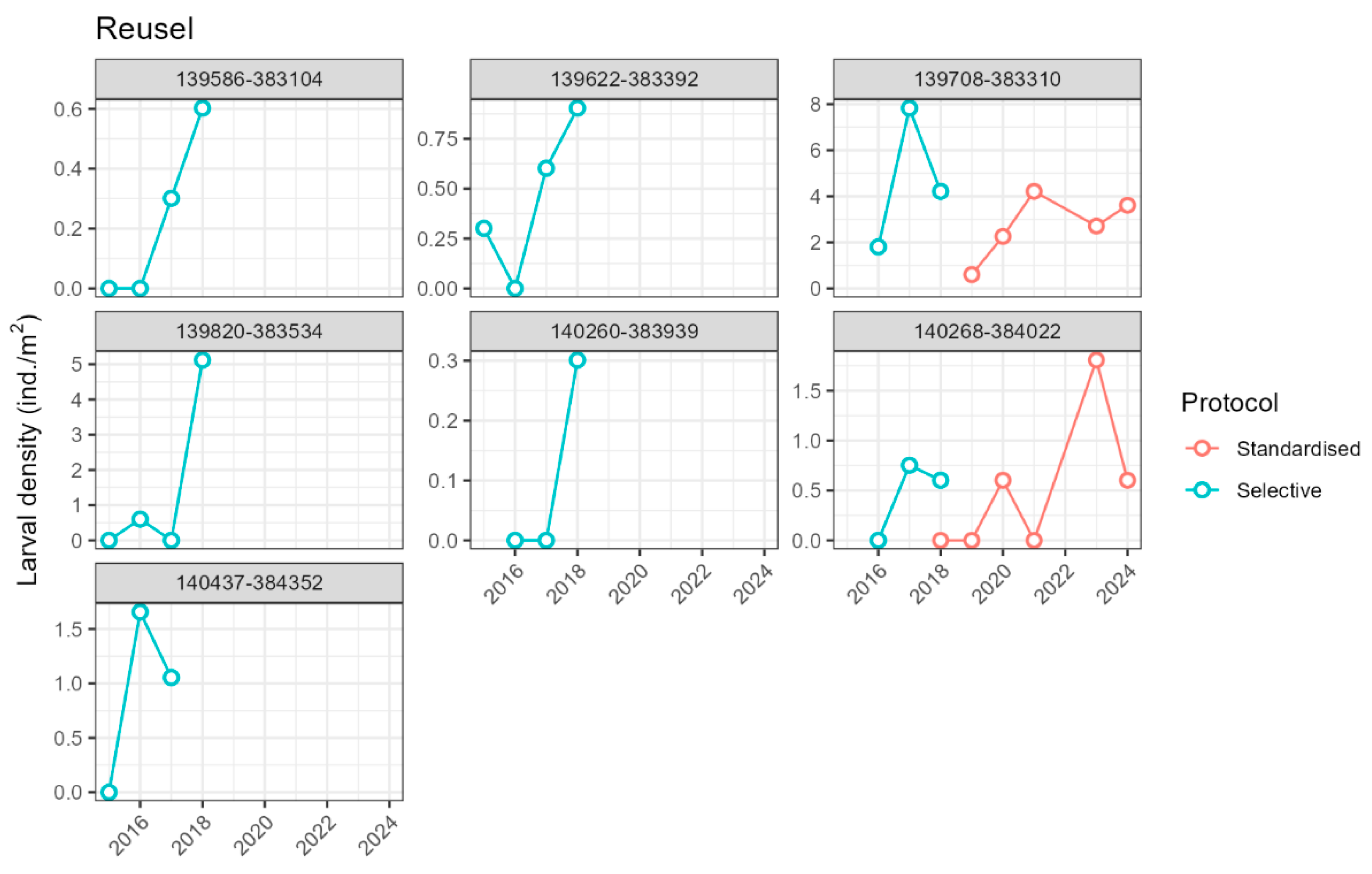

2.4.1. Larva Density and Demography

2.4.2. Population Size

2.5. Evaluation of Reintroduction Success

3. Results

3.1. Donor Population

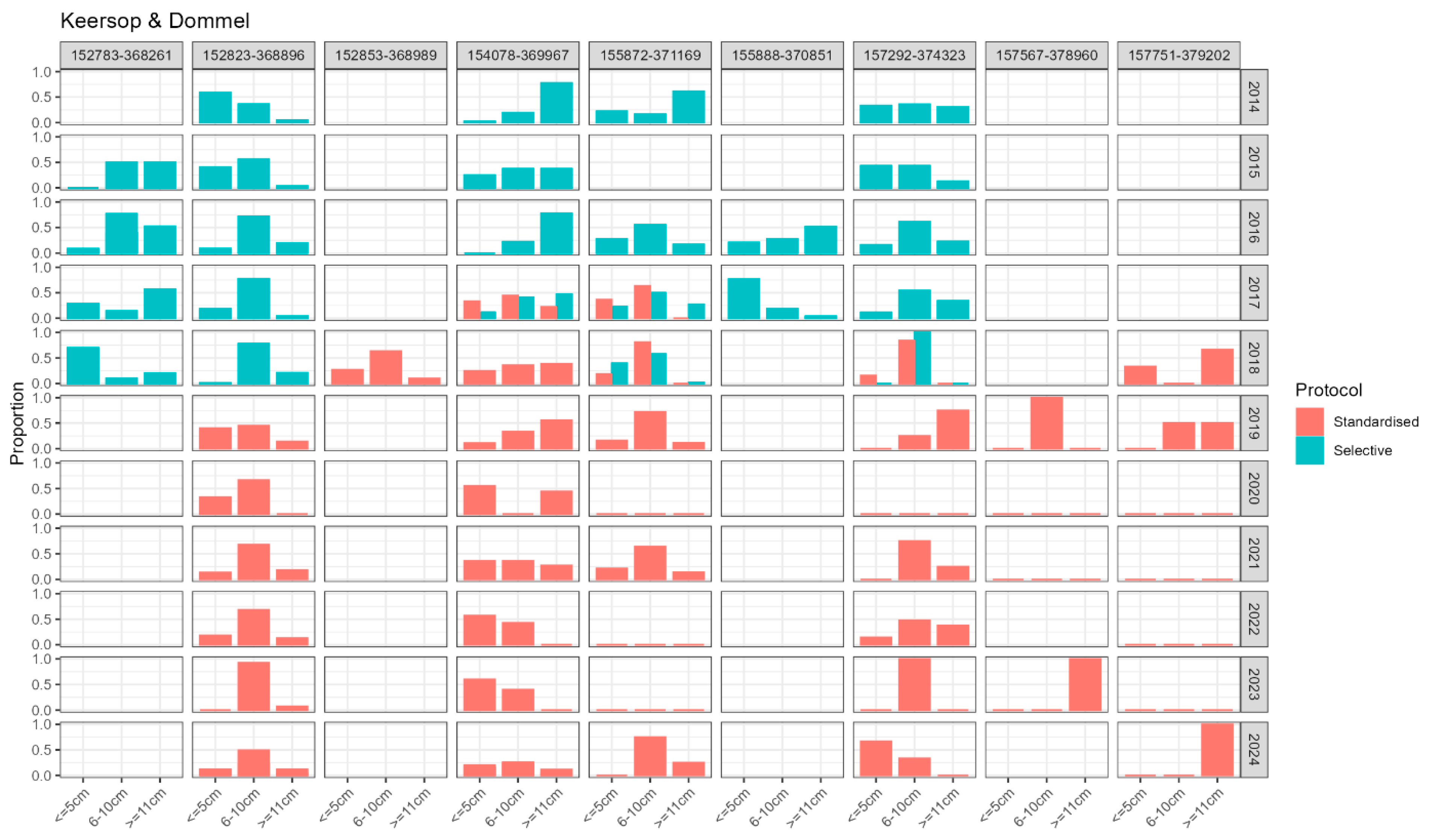

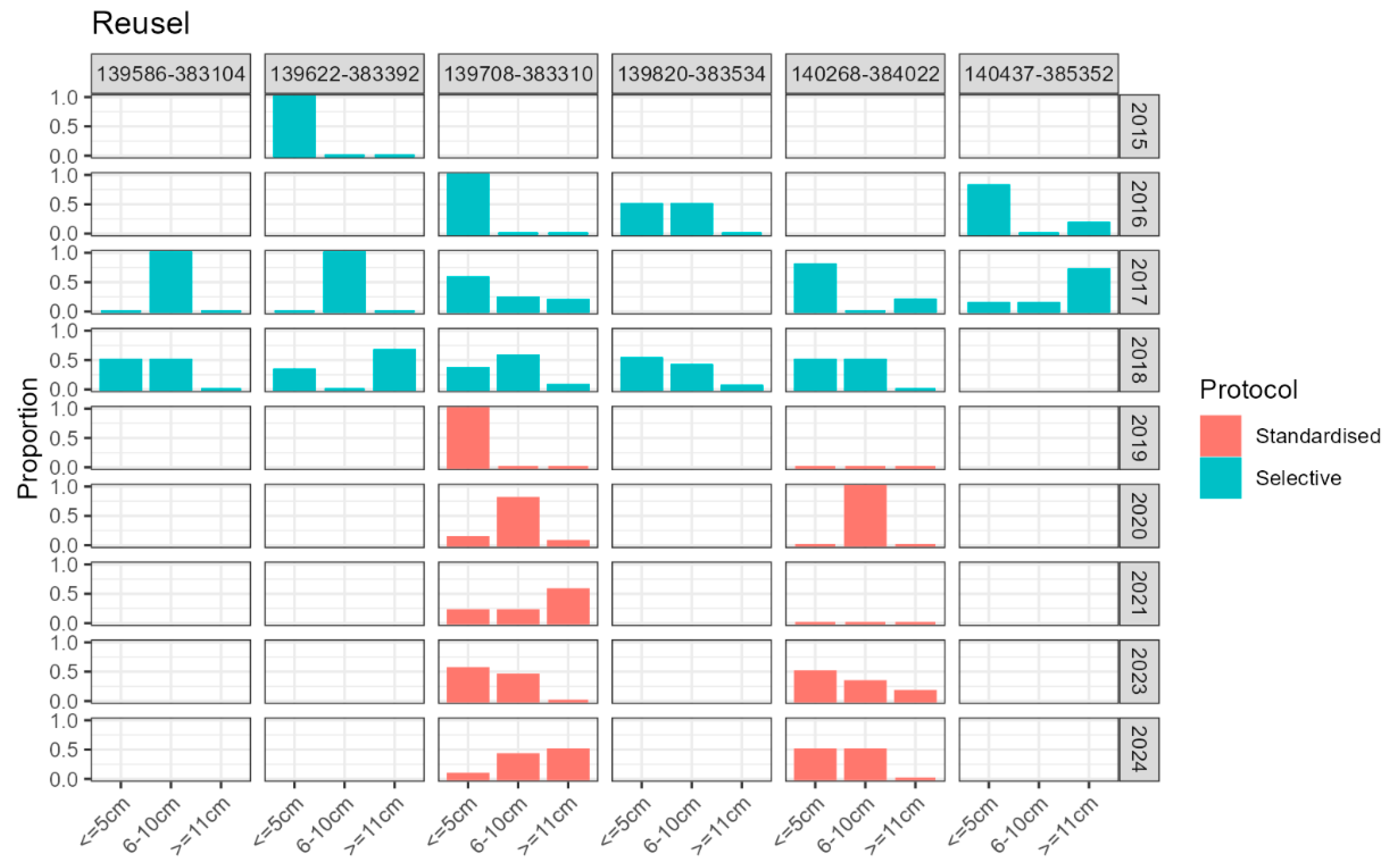

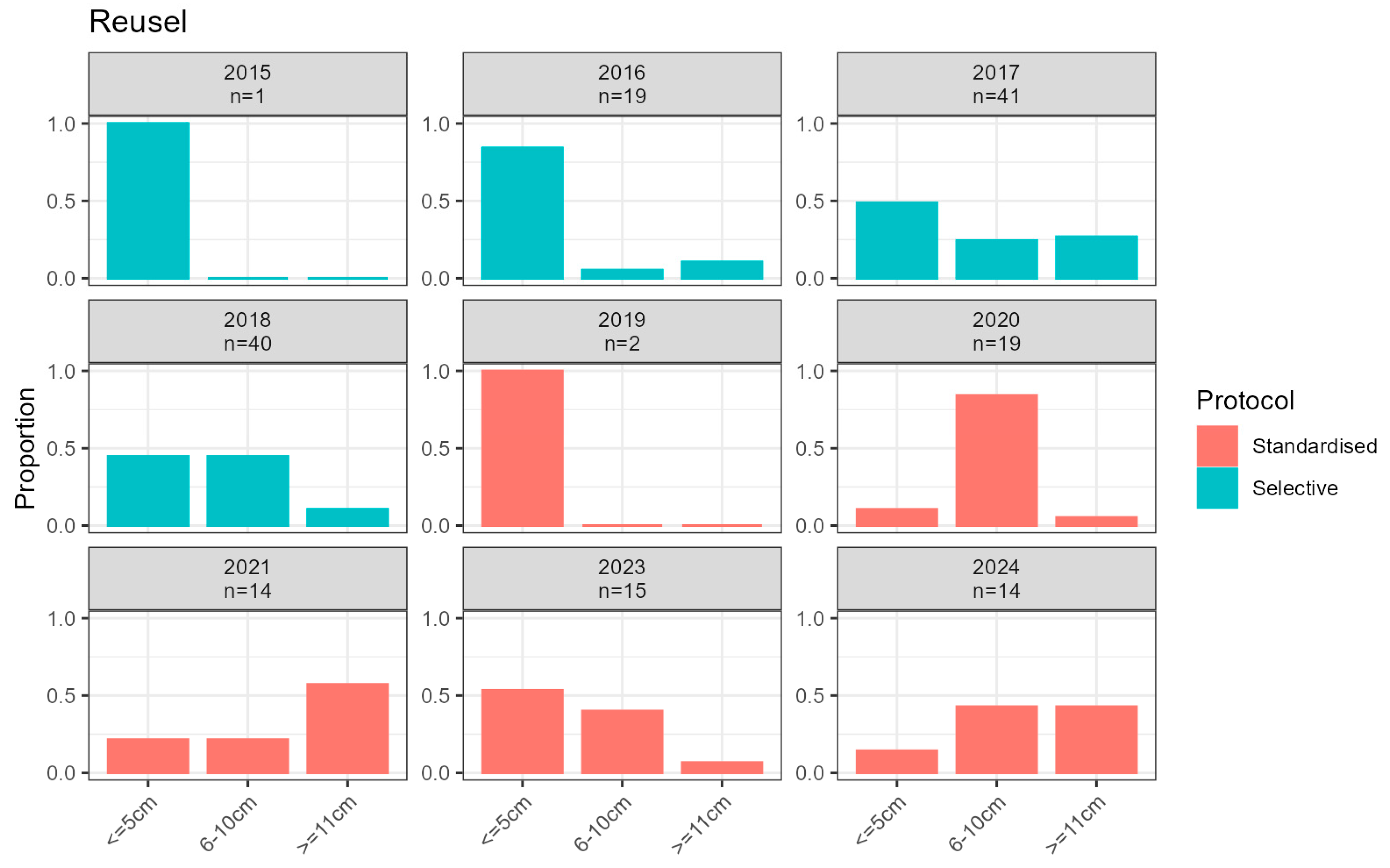

3.2. Introduced Population

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

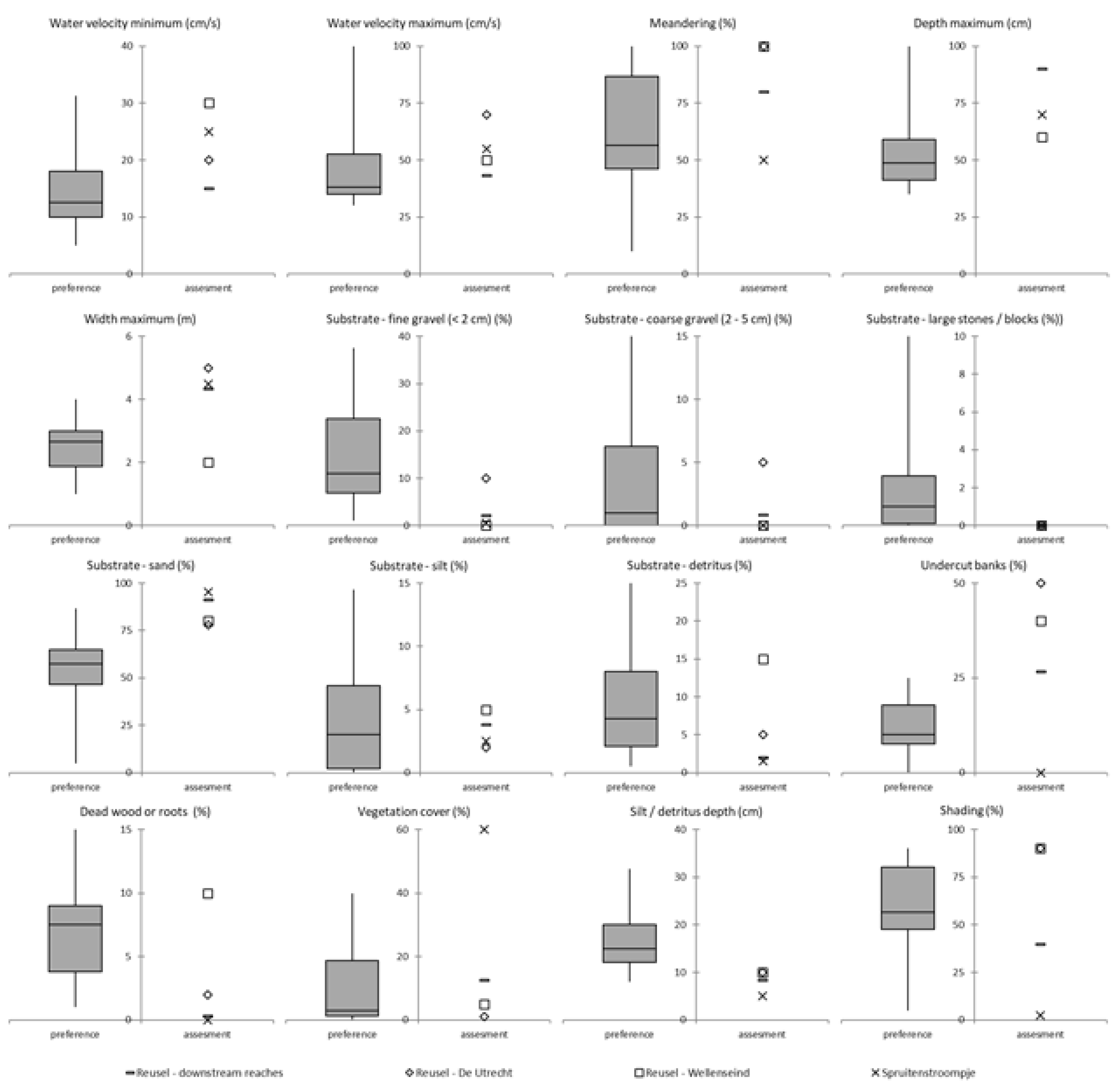

Appendix A: Habitat Reference Values for Brook Lamprey and Assessments

Appendix B: Visual Material of the Reusel

Appendix C: Specifications of Translocated Brook Lampreys

Appendix D: Specifications of Larval Monitoring Sites

|

Appendix C: Criteria for Evaluation of Lamprey Reintroduction

Appendix D: Average Larval Densities

Appendix E: Larval Demography Details per Monitoring Site

References

- Maitland, P. S.; Renaud, C. B.; Quintella, B. R.; Close, D. A.; Docker, M. F. Conservation of Native Lampreys. Lampreys: Biology, Conservation and Control: Volume 1 2015, 375–428.

- Evans, T. M.; Janvier, P.; Docker, M. F. The Evolution of Lamprey (Petromyzontida) Life History and the Origin of Metamorphosis. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2018, 28 (4), 825–838. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. J.; Michael Hudson, J.; Lassalle, G.; Whitesel, T. A. Impacts of a Changing Climate on Native Lamprey Species: From Physiology to Ecosystem Services. J. Great Lakes Res. 2021, 47, S186–S200. [CrossRef]

- Polyakova, N. V.; Kucheryavyy, A. V.; Genelt-Yanovskaya, A. S.; Yurchak, M. I.; Zvezdin, A. O.; Pavlov, D. S. Characteristics of Typical Habitats of River Lamprey Lampetra Fluviatilis Larvae (Petromyzontidae). Inland Water Biol. 2024, 17 (5), 783–796.

- De Cahsan, B.; Nagel, R.; Schedina, I.-M.; King, J. J.; Bianco, P. G.; Tiedemann, R.; Ketmaier, V. Phylogeography of the European Brook Lamprey (Lampetra Planeri) and the European River Lamprey (Lampetra Fluviatilis) Species Pair Based on Mitochondrial Data. J. Fish Biol. 2020, 96 (4), 905–912. [CrossRef]

- Hardisty, M. W. The Life History and Growth of the Brook Lamprey (Lampetra Planeri). J. Anim. Ecol. 1944, 13 (2), 110. [CrossRef]

- Malmqvist, B. Population Structure and Biometry of Lampetra Planeri (Bloch) from Three Different Watersheds in South Sweden. Archiv fur Hydrobiologie 1978, 84 (1), 65–86.

- Bird, D. J.; Potter, I. C. Metamorphosis in the Paired Species of Lampreys, Lampetra Fluviatilis (L.) and Lampetra Planeri (Bloch): 1. A Description of the Timing and Stages. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 1979, 65 (2), 127–143. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, F. L.; King, J. J. A Review of the Ecology and Distribution of Three Lamprey Species, Lampetra Fluviatilis (L.), Lampetra Planeri (Bloch) and Petromyzon Marinus (L.): A Context for Conservation and Biodiversity Considerations in Ireland; biology and environment: Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy; JSTOR, 2001.

- Moser, M.; Almeida, P.; Kemp, P.; Sorensen, P. Lamprey Spawning Migration. : Docker M. (eds) Lampreys: Biology, Conservation Control; 2015.

- Ford, M. Lampetra planeri. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2024. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/11213/135088684 (accessed 2024-11-23).

- Spikmans, F.; Kranenbarg, J. Nieuwe Rode Lijst Vissen Nederland. RAVON 2016, 18 (1), 9–12.

- Visatlas van Nederland; Kranenbarg, J., Herder, J., van Emmerik, W. A. M., Groen, M., Eds.; Noordboek Uitgeverij: Gorredijk, 2022.

- Bartholomeus, R. P.; Van Der Wiel, K.; Van Loon, A. F. Managing Water across Flood-Drought Spectrum: Experiences from Challenges in the Netherlands. Cambridge Prisms: Water 2023, 1. [CrossRef]

- Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the Conservation of Natural Habitats and of Wild Fauna and Flora (OJ L 206 22.07.1992 P. 7). In Documents in European Community Environmental Law; Sands, P., Galizzi, P., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2006; pp 568–583. [CrossRef]

- CLO. Migratiemogelijkheden Voor Trekvissen; indicator 1350, versie 10, 15 september 2022 www.clo.nl; Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (CBS), Den Haag; PBL Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving, Den Haag; RIVM Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu, Bilthoven; en Wageningen University and Research, Wageningen., 2022.

- Spikmans, F.; Schiphouwer, M.; Kranenbarg, J.; Breeuwer, H. Naar Duurzame Populaties Beekprik in Noord-Brabant. Voorbereidingsstudie Herintroductie; 2011-113; Stichting RAVON, Nijmegen & IBED – Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2013.

- Bezem, J. Forse Natuurschade Door Baggerwerkzaamheden. Land + water: magazine voor civiele en milieutechniek 2011, 51 (8), 8.

- Seddon, P. J. From Reintroduction to Assisted Colonization: Moving along the Conservation Translocation Spectrum. Restor. Ecol. 2010, 18 (6), 796–802.

- Kirchhofer, A. Biologie, Gefährdung Und Schutz Der Neunaugen in Der Schweiz; Mitteilungen zur Fischerei 56; Bundesamt für Umwelt, Wald und Landschaft, 1996.

- Krappe, M.; Lemcke, R.; Meyer, L.; Schubert, M. Fisch Des Jahres 2012 - Die Neunaugen; 2012.

- Ratschan, C.; Jung, M.; Riehl, B.; Zauner, G. Attempt to Reintroduce the Ukrainian Brook Lamprey (Eudontomyzon Mariae) to the Salzach River by Translocation from the Inn River. (Wiederansiedelungsversuch von Neunaugen (Eudontomyzon Mariae) an Der Salzach Durch Initialbesatz von Tieren Aus Dem Inn). Oesterr. Fisch. 2021, 74 (2/3), 51–69.

- Close, D. A.; Currens, K. P.; Jackson, A.; Wildbill, A. J.; Hansen, J.; Bronson, P.; Aronsuu, K. Lessons from the Reintroduction of a Noncharismatic, Migratory Fish: Pacific Lamprey in the Upper Umatilla River, Oregon; American Fisheries Society Symposium; Citeseer, 2009; Vol. 72.

- Ward, D. L.; Clemens, B. J.; Clugston, D.; Jackson, A. D.; Moser, M. L.; Peery, C.; Statler, D. P. Translocating Adult Pacific Lamprey within the Columbia River Basin: State of the Science. Fisheries 2012, 37 (8), 351–361.

- Clemens, B.; Reid, S.; Tinniswood, B.; Smith, T.; Smith, R.; Reid, O.; Ortega, J.; Ramirez, B. Miller Lake Lamprey 2021 Progress Report, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Number 2021-14; 2021.

- Medne, R.; Purvina, S.; Vjačeslavs, R.; Balodis, J.; Gurjeva, L. Handbook for River Lamprey Restocking Methods. Project: Cross-Boundary Evaluation and Management of Lamprey Stocks in Lithuania and Latvia LAMPREY LLI-310; Institute of Food Safety, Animal Health and Environment: Riga, 2020.

- Lampman, R. T.; Maine, A. N.; Moser, M. L.; Arakawa, H.; Neave, F. B. Lamprey Aquaculture Successes and Failures: A Path to Production for Control and Conservation. J. Great Lakes Res. 2021, 47, S201–S215. [CrossRef]

- Kujawa, R.; Fopp-Bayat, D.; Cejko, B. I.; Kucharczyk, D.; Glińska-Lewczuk, K.; Obolewski, K.; Biegaj, M. Rearing River Lamprey Lampetra Fluviatilis (L.) Larvae under Controlled Conditions as a Tool for Restitution of Endangered Populations. Aquac. Int. 2018, 26, 27–36.

- IUCN. Guidelines for Re-Introductions Prepared by the IUCN / SSC Re-Introduction Specialist Group; IUCN, Gland, Switzerland & Cambridge, UK, 1998.

- NDFF. National Databank on Flora and Fauna, 2024. https://ndff-ecogrid.nl/uitvoerportaal (accessed 2024-11-14).

- Moller Pillot, H. K. M. Faunistische Beoordeling van de Verontreiniging in Laaglandbeken; Pillot-Standaardboekhandel: Tilburg, 1971.

- Terink, W.; Van Deijl, D.; Van den Eertwegh, G. Reusel Bovenstroom – Integrale Analyse van Hydrologie Watersysteem En Landgebruik Huidige Situatie En Effecten van Maatregelen Op Drogestofproductie, Natuur En Hydrologie Stroomgebied; Deelproject TKIKLIMA; KnowH2O, Berg en Dal, 2023.

- Spikmans, F.; Kranenbarg, J. Naar Duurzame Populaties Beekprik in Noord-Brabant. Plan van Aanpak Herintroductie 2013-2014; RAVON, Nijmegen, 2013.

- Hardisty, M. W. The Growth of Larval Lampreys. J. Anim. Ecol. 1961, 30 (2), 357. [CrossRef]

- Malmqvist, B. Habitat Selection of Larval Brook Lampreys (Lampetra Planeri, Bloch) in a South Swedish Stream. Oecologia 1980, 45 (1), 35–38. [CrossRef]

- Liedtke, T. L.; Harris, J. E.; Blanchard, M. R.; Skalicky, J. J.; Grote, A. B. Synthesis of Larval Lamprey Responses to Dewatering: State of the Science, Critical Uncertainties, and Management Implications. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J.; Cowx, I. Monitoring River, Brook Sea Lamprey, Lampetra Fluviatilis, L. Planeri Petromyzon Marinus. Conserving Natura 2000 Rivers; Monitoring Series no. 5.; Natural England, Peterborough, 2003.

- Steeves, T. B.; Slade, J. W.; Fodale, M. F.; Cuddy, D. W.; Jones, M. L. Effectiveness of Using Backpack Electrofishing Gear for Collecting Sea Lamprey (Petromyzon Marinus) Larvae in Great Lakes Tributaries. J. Great Lakes Res. 2003, 29, 161–173.

- Dunham, J. B.; Chelgren, N. D.; Heck, M. P.; Clark, S. M. Comparison of Electrofishing Techniques to Detect Larval Lampreys in Wadeable Streams in the Pacific Northwest. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2013, 33 (6), 1149–1155. [CrossRef]

- Harris, J. E.; Jolley, J. C.; Silver, G. S.; Yuen, H.; Whitesel, T. A. An Experimental Evaluation of Electrofishing Catchability and Catch Depletion Abundance Estimates of Larval Lampreys in a Wadeable Stream: Use of a Hierarchical Approach. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 2016, 145 (5), 1006–1017. [CrossRef]

- Smith, F.; Schiphouwer, M.; Spikmans, F.; Kranenbarg, J. Handleiding Aantalsmonitoring Beekprik: Methode En Invoer van Gegevens; 2018.025; Stichting RAVON, 2018.

- RAVON. Handleiding Voor Het Monitoren van Zoetwatervissen in Nederland, Eerste Druk; RAVON: Nijmegen, 2023.

- Ter Harmsel, R.; Kranenbarg, J.; Schippers, T. C. Handleiding Meetnet Amfibieën En Vissen in Natura 2000- Gebieden. Kamsalamander, Beekprik, Rivierdonderpad, Bittervoorn, Kleine Modderkruiper En Grote Modderkruiper; Versie 3.0; RAVON, Nijmegen, 2021.

- Shephard, S.; Gallagher, T.; Rooney, S. M.; O’Gorman, N.; Coghlan, B.; King, J. J. Length-based Assessment of Larval Lamprey Population Structure at Differing Spatial Scales. Aquat. Conserv. 2019, 29 (1), 39–46.

- Goodwin, C. E.; Dick, J. T. A.; Rogowski, D. L.; Elwood, R. W. Lamprey (Lampetra Fluviatilis and Lampetra Planeri) Ammocoete Habitat Associations at Regional, Catchment and Microhabitat Scales in Northern Ireland. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 2008, 17 (4), 542–553. [CrossRef]

- Caskenette, A. L. Recovery Potential Modelling of Northern Brook Lamprey (Ichthyomyzon Fossor) – Saskatchewan-Nelson River Populations; Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Res. Doc. 2024/022.; DFO, 2024. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2024/mpo-dfo/fs70-5/Fs70-5-2024-022-eng.pdf.

- Seddon, P. J. Persistence without Intervention: Assessing Success in Wildlife Reintroductions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1999, 14 (12), 503.

- Seddon, P. J. Using the IUCN Red List Criteria to Assess Reintroduction Success. Anim. Conserv. 2015, 18 (5), 407–408.

- Robert, A.; Colas, B.; Guigon, I.; Kerbiriou, C.; Mihoub, J.; Saint-Jalme, M.; Sarrazin, F. Defining Reintroduction Success Using IUCN Criteria for Threatened Species: A Demographic Assessment. Anim. Conserv. 2015, 18 (5), 397–406.

- Shier, D. M. Developing a Standard for Evaluating Reintroduction Success Using IUCN Red List Indices. Anim. Conserv. 2015, 18 (5), 411–412.

- Mace, G. M.; Collar, N. J.; Gaston, K. J.; Hilton-Taylor, C.; Akçakaya, H. R.; Leader-Williams, N.; Milner-Gulland, E. J.; Stuart, S. N. Quantification of Extinction Risk: IUCN’s System for Classifying Threatened Species. Conserv. Biol. 2008, 22 (6), 1424–1442.

- IUCN. Guidelines for Application of IUCN Red List Criteria at Regional and National Levels: Version 4.0; IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK, 2012.

- IUCN Standards and Petitions Committee. Guidelines for Using the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria. Version 16. https://www.iucnredlist.org/documents/RedListGuidelines.pdf (accessed 2024-09-23).

- IUCN. IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria: Version 3.1. Second Edition; iv; IUCN, Gland, Switzerland & Cambridge, UK, 2012.

- Schiphouwer, M.; Spikmans, F. Ze Paaien in de Reusel-Eerste Resultaten Beekprik Herintroductie Noord-Brabant Zijn Bemoedigend. Schubben & Slijm 2016, 8 (1), 21–21.

- RAVON Balans 2024; Herder, J., Van Delft, J., Joosten, K., Eds.; RAVON, Nijmegen, 2024.

- Lorenzen, K. Fish Population Regulation beyond “stock and Recruitment”: The Role of Density-Dependent Growth in the Recruited Stock. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2008, 83 (1), 181–196.

- COSEWIC. COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Northern Brook Lamprey Ichthyomyzon Fossor (Great Lakes - Upper St. Lawrence Populations and Saskatchewan - Nelson River Populations) and the Silver Lamprey Ichthyomyzon Unicuspis (Great Lakes - Upper St. Lawrence Populations, Saskatchewan - Nelson River Populations and Southern Hudson Bay - James Bay Populations) in Canada; xxiv; Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, Ottawa, 2020.

- Mignien, L.; Stoll, S. Effects of High and Low Flows on Abundances of Fish Species in Central European Headwater Streams: The Role of Ecological Species Traits. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 888 (163944), 163944. [CrossRef]

- Bogan, M. T.; Leidy, R. A.; Neuhaus, L.; Hernandez, C. J.; Carlson, S. M. Biodiversity Value of Remnant Pools in an Intermittent Stream during the Great California Drought. Aquat. Conserv. 2019, 29 (6), 976–989. [CrossRef]

- Potter, I. C.; Hill, B. J.; Gentleman, S. Survival and Behaviour of Ammocoetes at Low Oxygen Tensions. J. Exp. Biol. 1970, 53 (1), 59–73.

- Potter, I. C.; Beamish, F. W. H. Lethal Temperatures in Ammocoetes of Four Species of Lampreys. Acta Zool. 1975, 56 (1), 85–91.

- Rodríguez-Lozano, P.; Leidy, R. A.; Carlson, S. M. Brook Lamprey Survival in the Dry Riverbed of an Intermittent Stream. J. Arid Environ. 2019, 166, 83–85.

- Peeters, A.; Houbrechts, G.; de le Court, B.; Hallot, E.; Van Campenhout, J.; Petit, F. Suitability and Sustainability of Spawning Gravel Placement in Degraded River Reaches, Belgium. Catena 2021, 201 (105217), 1–16. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).