2.2. Research Methods

2.2.1. Design

This study employed an exploratory embedded single-case study design following Yin’s approach [

6]. This study design was used to address the research questions as the approach is suited to answering exploratory questions, such as the “how” and “why” a particular phenomenon occurs [

6]. In addition, an explanation construction method was used to analyze the data, aiming to construct an explanation of the case, including how care was implemented and its outcomes.

The explanation construction method analyzes case study data by constructing explanations of the case with the purpose of generating ideas for further research rather than drawing final conclusions.

Case studies allow for in-depth exploration and are often used in health policy analyses when the phenomenon is happening and not within the researchers’ control [

6].

A single-case study design was selected over a multiple-case study design, as this approach allows for a more extensive analysis of the embedded units, which yields greater insights into the case [

6]. A single case study allows the researcher to explore new theoretical relationships to develop a deeper understanding of these phenomena [

7]. Therefore, this study adopted a single-case rather than a multiple-case study design.

2.2.2. Defining the Case and Data Source

Within an embedded single-case study design, two or more embedded units of analysis are positioned within the case and context [

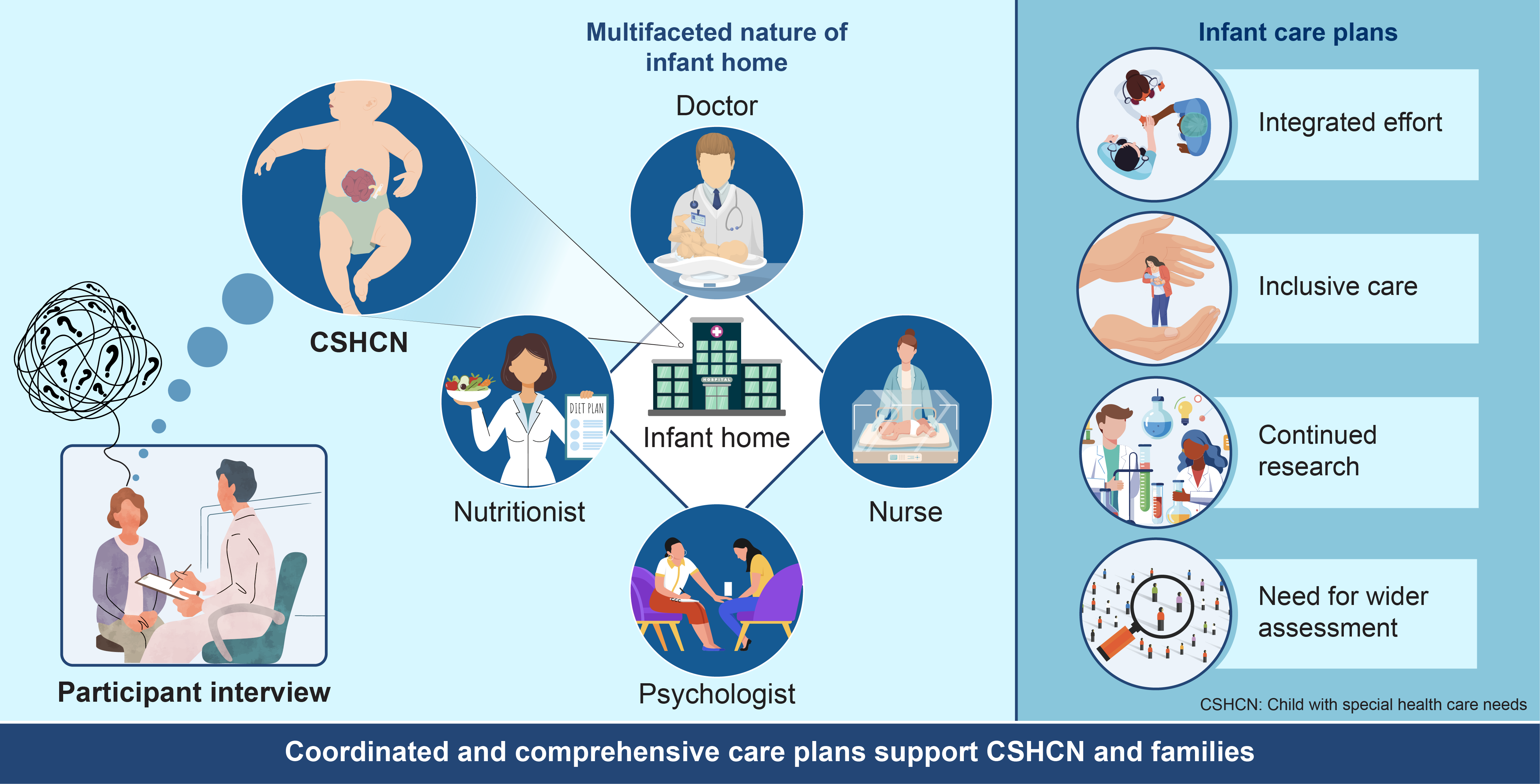

6]. The context of this study is the care system for CSHCN and their families in Japan, and the case is the care provided to the CSHCN and their families. The two units of analysis are the thoughts and practices of the staff at the infant home and the impact and changes experienced by the CSHCN and their families.

For the selected case, nurses, childcare workers, family support specialists, and parents who were the child’s primary caregivers during the child’s stay at the infant care center were interviewed. Documents were also used to corroborate the interview data and provide a detailed context for the case.

2.2.3. Case Selection Criteria

The following selection criteria were used.

1) Children admitted in 2018 or later were admitted to the facility for at least 1 year and discharged at the time the survey was conducted.

2) Cases where the child’s parents were in a position to be informed of the research, fully understand the content of the research and decide to cooperate in the research.

3) Cases considered to be CSHCN at the time of admission to the facility based on the CSHCN definition and CSHCN screener.

The CSHCN screener items were as follows

☑ Use of medications (other than vitamins) prescribed by a physician

☑ Access to medical, mental health, and educational services

☑ Limitation or inhibition of capacity

☑ Use of physical, occupational, speech, and other therapies

☑ Emotional, developmental, or behavioral issues

The question is whether the problem is due to a medical, behavioral, or health condition and lasts for > 12 months; if any one of these two criteria is met, the patient is classified as a CSHCN.

2.2.4. Data Collection

All interviews were conducted face-to-face in a mutually agreed-upon private location. Parental interviews were conducted with the mother; however, the child’s father was also present. One researcher (TN) conducted all interviews and reviewed all the documentation. An interview guide was used to explore how care was provided to the child and family and their perceptions of the outcomes, methods, and quality of care. Documentation was used to construct a description of care practices in alignment with the interview data, although this was not coded.

2.2.5. Data Analysis

The data sets obtained from the case studies (the four types of data sources recommended by Yin, documentation, archival records, interviews, and physical artifacts) were analyzed based on a strict explanation-building protocol that had been set in advance [

6]. The explanation-building analysis strategy was designed for case studies involving single-case sites and aimed to construct detailed explanations that are suited to each individual case. Yin states that this method is “similar to creating an overall explanation of the findings from multiple experiments in science” [

6].

Multiple members of the research team performed iterative analysis. In the first stage, the interview data was transcribed, and the content related to care, initiatives, and the impact on children and families was extracted. Furthermore, the extracted content was classified based on the similarity of the initiatives and their impact. At that time, data was searched for in data resources, such as records and documents, to show whether the content of care and initiatives actually had an impact on children and families, and the impact was corroborated. When interpreting the interview data, we repeatedly referred back to the written data sources and compared them with the interview data to confirm the details of the cases and corroborate the content of the interview data. In the second stage, we confirmed how care was implemented and what results were produced based on the interview data obtained from each participant and other data sources. In particular, the narratives of the children’s families were used to check for any discrepancies or agreement in terms of the expected impact of the care and initiatives and any content for which the impact or effectiveness was uncertain for the infant home staff.

In the third stage, the data on the initiatives and impacts that had been classified were arranged by time period, from before admission to after discharge, and descriptions based on data sources were combined and written to explain the actual care in several categories.

2.2.6. Reliability and Validity

Several methods have been used to ensure its reliability and validity. The researcher utilized a data analysis strategy for explanation building, as advocated by Yin [

6]. In view of this analysis, during the coding process, the researcher utilized observations and field notes to ensure the validity of the study.

Prior to the study, a list of interview questions and document types to be used as data sources was prepared. Additionally, to obtain diverse perspectives, participants included individuals from various occupations and positions as well as varied documentation sources. Although the staff of the infant care center and the child’s family provided narratives, the research team’s neutrality was established with the participants prior to the interviews. Nursing research experts reviewed the findings to ensure alignment with the actual case context.

Strategies such as credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability were used to ensure the trustworthiness of the data. Credibility was ensured through member checking and triangulation. Transferability was ensured by a detailed description of the research methods and contexts, as well as a detailed description of the participants and their experiences. Dependability was ensured through dense descriptions, peer examinations, and triangulation. Confirmability was ensured by the process of reflexivity, whereby the researcher’s own biases or assumptions were made apparent through a reflexive journal.

3.Results

3.3. Explanation of Care Practices for the Child and His/Her Family

(B, nurse in charge; C, family support specialist; D, childcare worker in charge; E, mother of the child)

3.3.1. Connect First with Families in Crisis and Begin Alternative Care (Birth of the Child to Admission)

(a) Connect first with families in crisis

The child was diagnosed with congenital disease after birth, accompanied by a chronic rash, joint pain throughout the body, and a weakened immune system, which left him vulnerable to severe illness and recurrent pneumonia. In addition to the child’s health sensitivity and difficulty with bedtime routines, his slow growth and developmental delays were evident, leading his parents to worry that these difficulties might persist indefinitely. The burden and anxiety stemming from the child’s unique needs placed the family in a state of crisis. In response, the hospital psychologist recognized the parents’ distress and, through the Child Guidance Center, arranged a temporary placement at an infant home as an alternative foster home. This intervention, along with the psychologist’s validation of their concerns, provided significant relief for the child’s parents. Despite this great burden, the mother made every effort to remain close and supportive of her child.

Living in Japan, there is a strong cultural belief that children should be raised by their parents. If support had not been provided, I think we would have pushed ourselves too hard and both of us would have broken down (E-5)

(b) Beginning alternative foster care despite hesitating to accept it

The infant home initially faced challenges regarding the child’s distinctive appearance and had concerns about his care needs. However, the staff did not place blame on the parents who were struggling with guilt about leaving their child at the facility. Instead, they were involved in building a relationship between trust and providing emotional support. The parents faced difficulties because they felt that children should be raised by their parents, and they had taken on the responsibility of raising the child. The family support counselor emphasized the significance of the infant home as a means of providing alternative childcare for families facing a crisis.

Sometimes, the most difficult temporary period can be saved by having someone else take over for you. The period immediately after birth is particularly difficult, and for infants, hospital visits are an additional burden. Infant care centers can provide support in transformative ways (C-26)

3.3.2. Responding to the Children’s Needs from All Aspects and Supporting Their Growth Through Trial and Error (During Admission)

(a) Trial and error in devising care in the face of difficulties

After the child’s admission, the infant care center had to devise various aspects to meet his unique needs. The staff paid careful attention to physical assessments, including monitoring of fever and respiratory status, and coordinated frequent hospital visits. From the time of admission, the staff collaborated closely with the commissioned physician and the child’s attending physician to establish standards for medications and hospital visits and ensure that all staff were informed of these protocols. In addition to establishing medical standards, the staff addressed specific challenges, such as managing walking distances due to shortness of breath and helping with sleep difficulties caused by irritability. The childcare team emphasized the importance of collaboration, drawing on the expertise of multiple professionals.

Saturation measurements and other measures were introduced and standards were established with commissioned physicians (B-11).

They, in turn, informed the other staff members of what they had confirmed with the physician (B-4).

The reason it takes a lot of work is not a personnel problem but the staff’s willingness to help each other (D-16)

(b) Support children’s growth by working with them regarding food, which is the foundation of their development and can be a great source of enjoyment.

Various efforts have been made from a wide range of perspectives, including attending to children’s growth and development, diet, physical activity, and emotional and spiritual involvement. In terms of food, milk was thickened appropriately for a child at high aspiration risk, and the timing and progress of weaning food were discussed in consultation with the child’s doctor, dietitian, and cook. The staff observed that food was a crucial part of the children’s upbringing. As children progressed to regular infant foods, parents’ attitudes shifted positively, witnessing their children’s development and prevention of aspiration risks. This dietary progression not only contributed to physical growth but also brought children daily enjoyment. Nurses remarked that mealtimes became a source of joy and an indication of children’s growth.

She started weaning herself on baby food after consulting with her doctor, and after she passed the middle to late stage of eating, she started eating crunchy foods, which she enjoyed very much, partly because her chewing and swallowing functions had improved (B-22).

(c) Carefully develop growth and development based on the child’s physical and emotional characteristics.

Regarding physical activities, staff repeatedly encouraged children to use their feet to reach the desired objects, celebrating each small success together. Through daily interactions, we attempted to help the children learn how to use their bodies independently by drawing out their gradual growth and joy. Instead of forcing them to accomplish a task, the staff perceived what children could do individually, praised them, and celebrated with them. In particular, regarding the emotional and mental development of children, for example, they did not restrain them from expressing their feelings, such as when they shouted but accepted them and then shared gentle and polite ways of expressing their feelings. As the children’s needs were met, they gradually began to show greater awareness of others, often imitating adults by caring for younger children. By spending time with adults who were receptive to their feelings, the children learned to interact calmly with others, which greatly contributed to their interactions with their families and changed how they felt about them.

The family appreciated having meaningful conversations with the child, such as discussing waiting here or waiting for you, which they felt may have sparked the hope that they could eventually raise the child at home (C-12)

He used to cry all the time and was irritable and grumpy, but we thought that being able to wait and move around on his own was a huge deal because we thought it would fulfill a need in him (E-9)

(d) Professionals should utilize their own strengths and complement each other to be involved with the characteristics of the child.

Professionals worked collaboratively to integrate the medical aspects of meeting children’s health needs with childcare aspects supporting their daily growth, leveraging each other’s strengths. Although each held a unique perspective on the child, the nurses provided repeated explanations and training to enhance disease understanding and develop care techniques while respecting the insights of childcare workers. Parents felt comfortable with the presence of nurses who could answer their questions and concerns while improving their knowledge and skills regarding the care of their children. The knowledge and skills of those providing daily care were vital, as nurses believed that a solid understanding of each child’s healthcare needs significantly influenced their daily interactions.

Understanding the disease and detecting abnormalities early enables us to see the child as who they truly are (B-31)

3.3.3. Support the Family While Sharing the Child’s Growth and Working with Multiple Agencies (During Admission)

(a) Remaining close to the family while monitoring the child’s growth

In addition to interprofessional collaboration within the infant care center, a multiagency and multiprofessional approach was adopted to support the child’s family beyond routine childcare. The frequency and timing of family visits were arranged using the Child Guidance Center to consider the mother’s psychological state, with the same staff members involved as often as possible. During visits, staff members shared updates on the child’s condition and humorous moments with the family and communicated the family’s reactions to other staff members. The staff members shared their reactions and observations with their family members. A system of cooperation with medical institutions was also in place to respond to the children’s needs. The mother also understood the importance of careful involvement.

I thought how grateful I was that he went to the hospital every day without a single look of disgust and kindly explained everything to me when I met him (E-18).

(b) Responding to conflicting feelings about inadequate understanding of other institutions

However, situations such as consultations with non-attending physicians often require staff or parents to repeatedly explain the child’s circumstances because of limited understanding from other institutions. The staff responded to this by providing supplementary explanations each time.

When visiting a doctor, the child’s background and the facility were unknown, and the situation often had to be explained first (B-16).

It would be beneficial if medical institutions, nursery schools, and educational institutions would quickly understand that the children are living in an infant care center because of something medical in terms of social participation of the children (E-19)

3.3.4. Continue to Explore Possibilities and Support for Family Childcare (Toward Leaving the Home)

(a) Explore all post-exit options

Through collaboration between multiple agencies and professionals, the infant home supported the child’s development while maintaining close communication with the family, leading to gradual progress in the child’s growth. However, in this case, the infant home was an institution that provided temporary alternative foster care, and there were many discussions about the child’s future. The parents discussed the difficulties with all options. They considered the possibility of returning the child to a specialized facility, such as a medical treatment and education center, foster care, or home. However, the parents, sensing the difficulty of all options, were concerned about their child’s future and gradually began to consider caring for their child at home.

I would be willing to consider consignment if there were foster parents who understood the child very well and who would remain connected and connected to the parents (D-23)

I kind of realized that there was no place for this child to go, and I thought that the situation would be more miserable elsewhere, so I started thinking about raising her at home (E-7)

(b) Attending to a child’s growth and development has a significant impact on the family

Considering the future course of the infant care center, the child’s remarkable growth greatly influenced the parents’ feelings. The staff made conscious efforts to move the child’s arms and legs and, in consultation with the doctor, introduced therapies, such as home-visit rehabilitation. For parents who had been burdened by merely observing their child’s struggles, these milestones provided a hopeful context for considering home-based care.

I was surprised at the amazing growth and thought I could manage to do it because I thought it would make a huge difference in my life and the amount of care I would receive (E-8)

(c) Work toward the child’s participation in society

In addition, the possibility of admission to a day care center when the child returned home was also significant for leaving the infant home. The staff worked with the Child Guidance Center and administrative agencies to provide after-school daycare services and nursery schools after the child was discharged from the infant home. The parents were anxious about their child’s eventual future, and being able to enroll their child in daycare meant the possibility of their child’s participation in the community. However, even in the process of considering the child’s future after leaving the daycare center, the parents took their time. They proceeded step-by-step, from visits to outings to overnight stays. When considering the family’s return home, the staff directly involved with the family shared their thoughts with other staff members so that they could understand how the child’s parents and siblings felt about the child. The family was hopeful about the possibility of their child participating in the community as steps were gradually taken.

I thought daycare would be important; when I saw her starting to walk, I thought daycare might be possible, allowing her to be part of the community (E-14)

(d) Establish a support system after leaving the facility and inform the family.

When families were able to visualize what they would like after leaving the infant home, the most important factor for their return home was the support system after leaving the home. The staff did not underestimate the difficulties of living together and believed that it was important to have an environment in which they could always obtain advice. Parents were informed that, even if they returned home, they could be supported again if they had any concerns through functions such as short stays. With this attitude and the backup system at the infant care center, parents were able to consider raising their children at home. In addition to the short stay, the support of professionals who knew the child well after leaving the center, such as accompanying the child to the hospital, played a crucial role, and the child was able to return home. The mothers were keenly aware of the significance of the post-discharge support.

I really appreciated the short stays and escorting me to the hospital when my life was not yet settled, and I was very anxious (E-23)

(e) Consider expanding support after leaving the facility.

However, the need for more extensive post-discharge support functions was also discussed. In particular, the Family Support Specialist Consultant emphasized the need for more extensive post-discharge support beyond short stays.

I think I would have needed to return within a few months like if I could come back again. It is normal to be away from them for a long time. It would be good if I could stay with them longer and help them with their housework (C-28)

It would have been nice if we could have had mothers come to stay and spend time at the infant home while preparing for an earlier return home(C-30)

3.3.5. Continue Childcare Support and Expand Functions Further (at the Time of Leaving the Center—After Leaving the Center)

(a) Fulfill the unique role of an infant care center

In this case, the infant care center’s unique expertise in fostering multidisciplinary and multi-organizational collaboration accompanied the child’s growth. It was able to accompany child-rearing from the time of admission to after discharge, playing a major role in the child’s growth and development and returning home. Although the parents of the children felt the importance of a specialized support organization in a crisis situation, the staff perceived the burden on the children’s families and the role played by the unique functions of the infant care center. In addition, with regard to post-discharge support, there was an emphasis on the importance of not only the facility but also society as a whole to develop a better understanding of children’s transitions post-discharge, aiming to cultivate expertise in welcoming them back with support, reflected in sentiments like, “You have come a long way.”

I had an image that relatives would take care of the children, and I had a vague knowledge that the only place to receive support was daycare, so I had no choice but to snap when I found out I could not get support from my family (E-3)

I think it was a heavy burden for the mothers to be worried about their children’s illnesses while the fathers were working and the grandparents were not able to provide support. I think that only an infant care center can provide such a stimulating environment for the children, where they can be seen at a distance (B-35).

(b) Responding to the child’s needs and accompanying family

Although a family-like environment is ideal for childcare, infant care centers have established a unique system in which professionals with diverse expertise exchange views to deepen their understanding of each child’s unique needs. It is very difficult for parents to raise a child who needs to go to the hospital every week while also taking care of their siblings after leaving the facility. The fact that the infant home provides support during infancy, enabling the child to eat, improving their skin condition, reducing prescription drugs, and reducing hospitalization has helped families feel that they may be able to raise their children at home. Mothers felt that they could raise their children at home. The mothers also valued specialized support, considering it a positive experience for their families.

I was surprised that there was a very solid system in place, and they really did a great job in areas that needed special care (E-17)

(c) Continue to develop a more comprehensive follow-up system

Finally, the actual care provided by the infant care center in the present case illustrates issues related to the function of the infant care center. In terms of responding to unique healthcare needs, although being attached to a medical institution can reduce travel time, this alone does not guarantee peace of mind. In Japan, there is a prevailing belief that children should be raised by their parents, which can create a barrier to accessing infant care center support. Furthermore, intermediary support services that bridge medical institutions and home care are limited. After accepting a child with distinctive healthcare needs and accompanying him as he grew up, the staff was concerned about coordinating and collaborating with him about his future career path and continuing to provide aftercare after he left the center, hoping that this would lead to expanded support in the future and leave a record of his achievements. The mother of one of the children emphasized the importance of a flexible follow-up system for childcare, as in this case.

Medical care, education, and life have become disconnected in Japan, making integration difficult. A societal system where these areas intersect would be beneficial. For instance, if there’s a ’yellow light’ in a child’s progress, there should be follow-up support to help guide them back to ’green’ or advise when it’s better to stop at ’red.’ There should be a place that watches over and supports children without focusing solely on whether they have a disability or illness (E-26)