Submitted:

18 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Objective Function

2.2. Orbital Forecasting of Space Debris and Optimization of Orbital Information

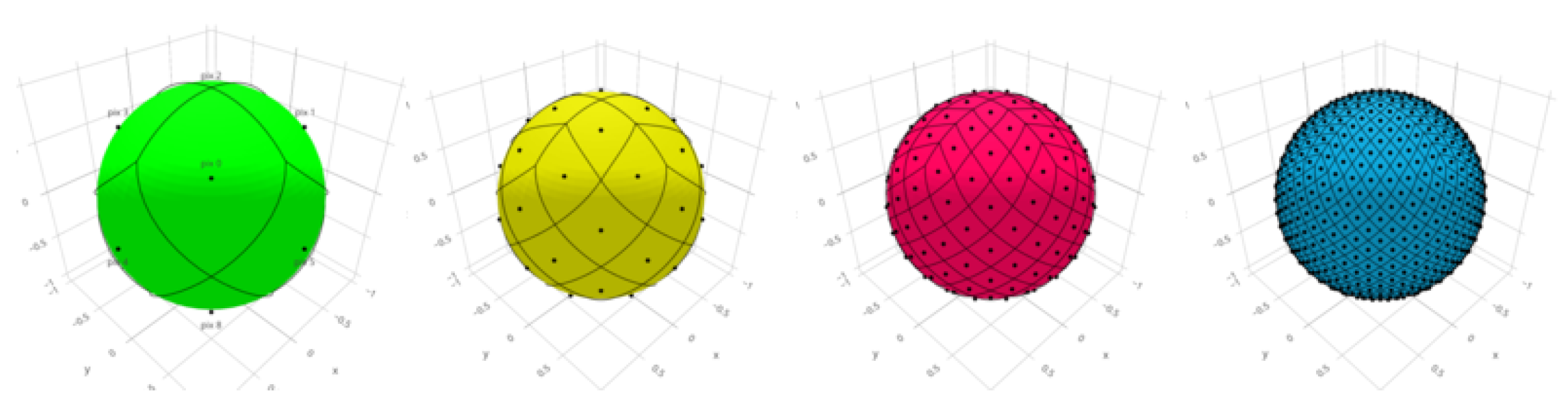

2.3. Spherical Pixelization Method Using HEALPix

2.4. Additive Sum Filtering and the Greedy Algorithm

3. Experiments and Results

3.1. Instrument Parameters

3.2. Experiment

3.2.1. Randomized Observation Strategy

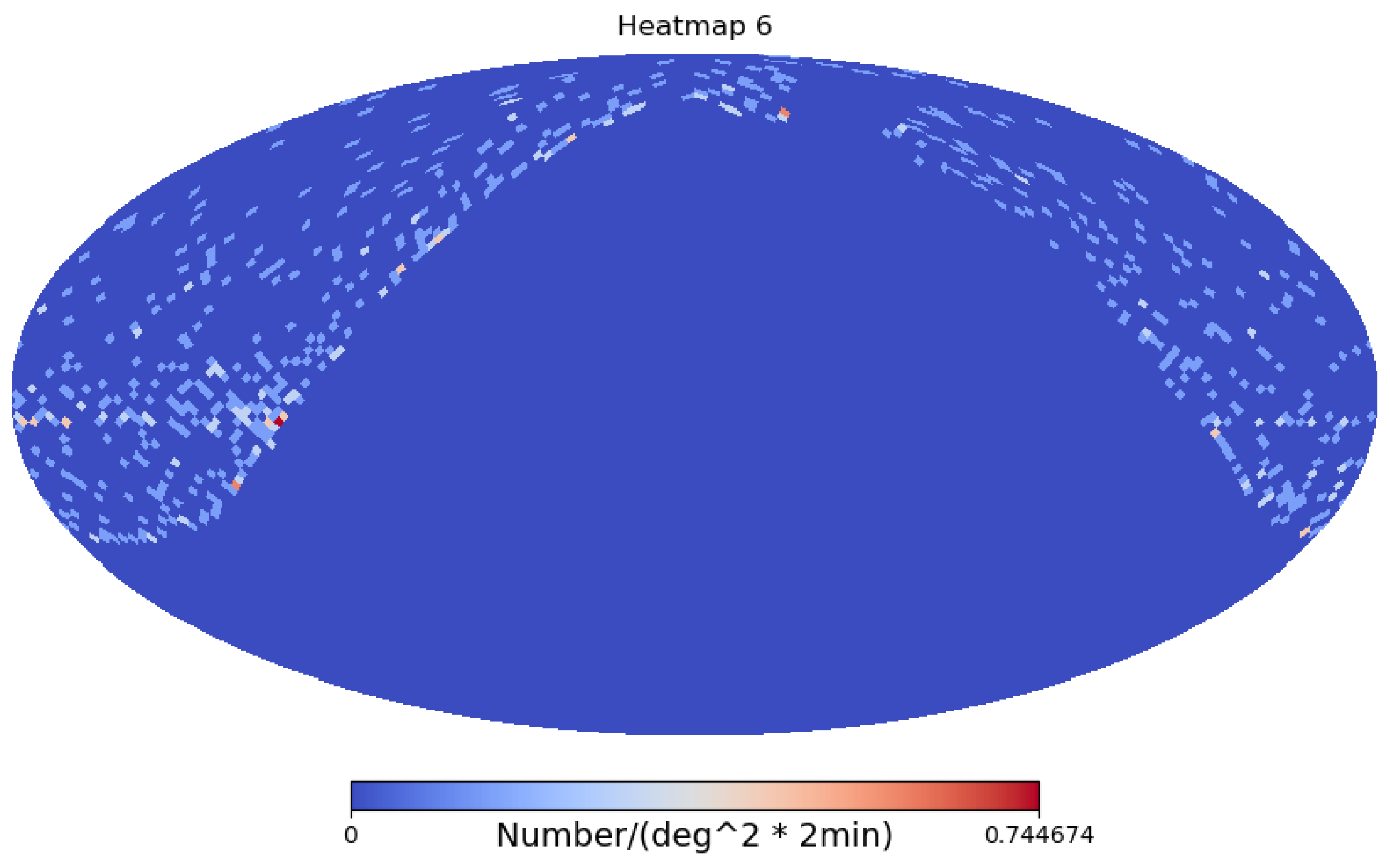

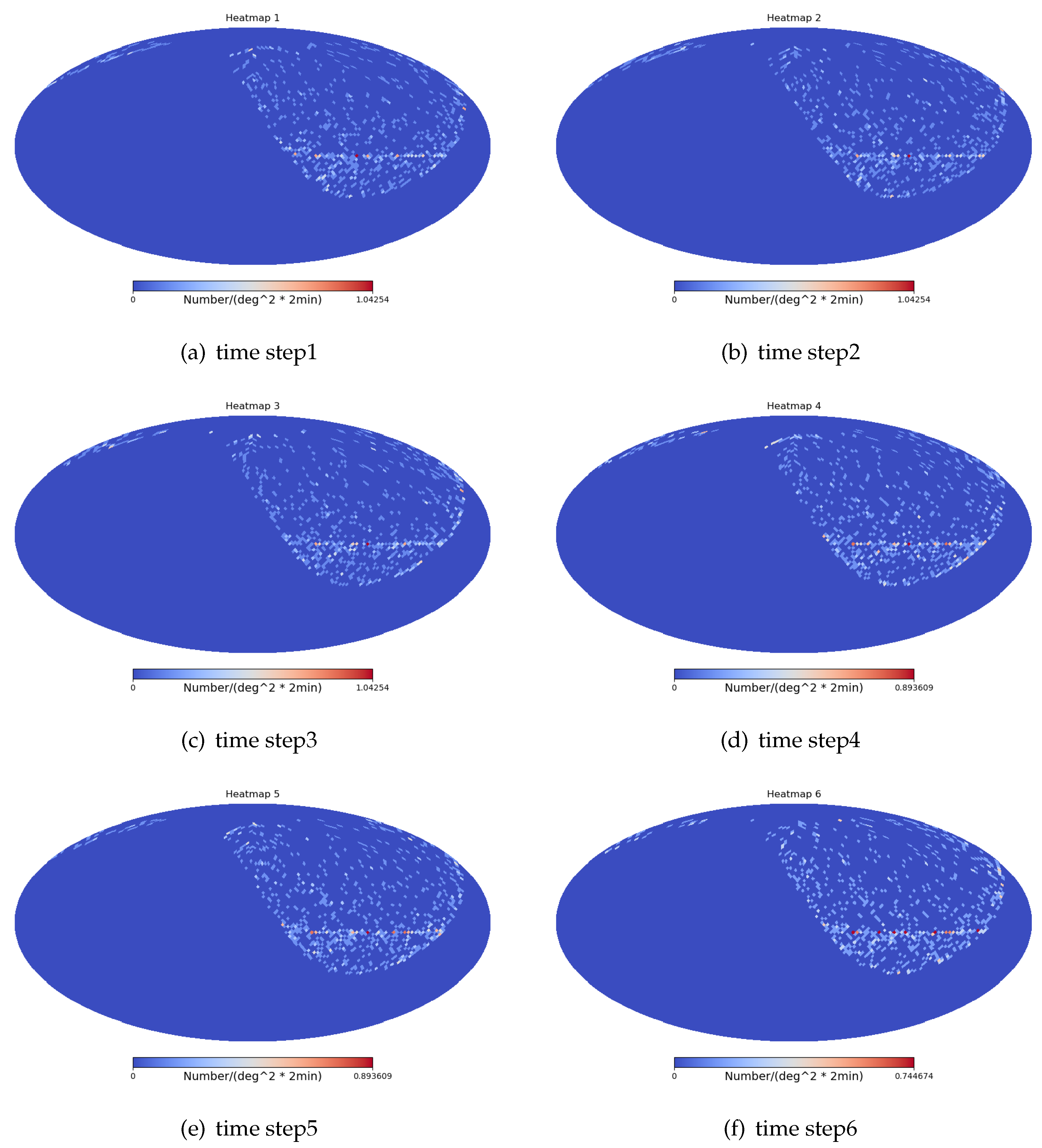

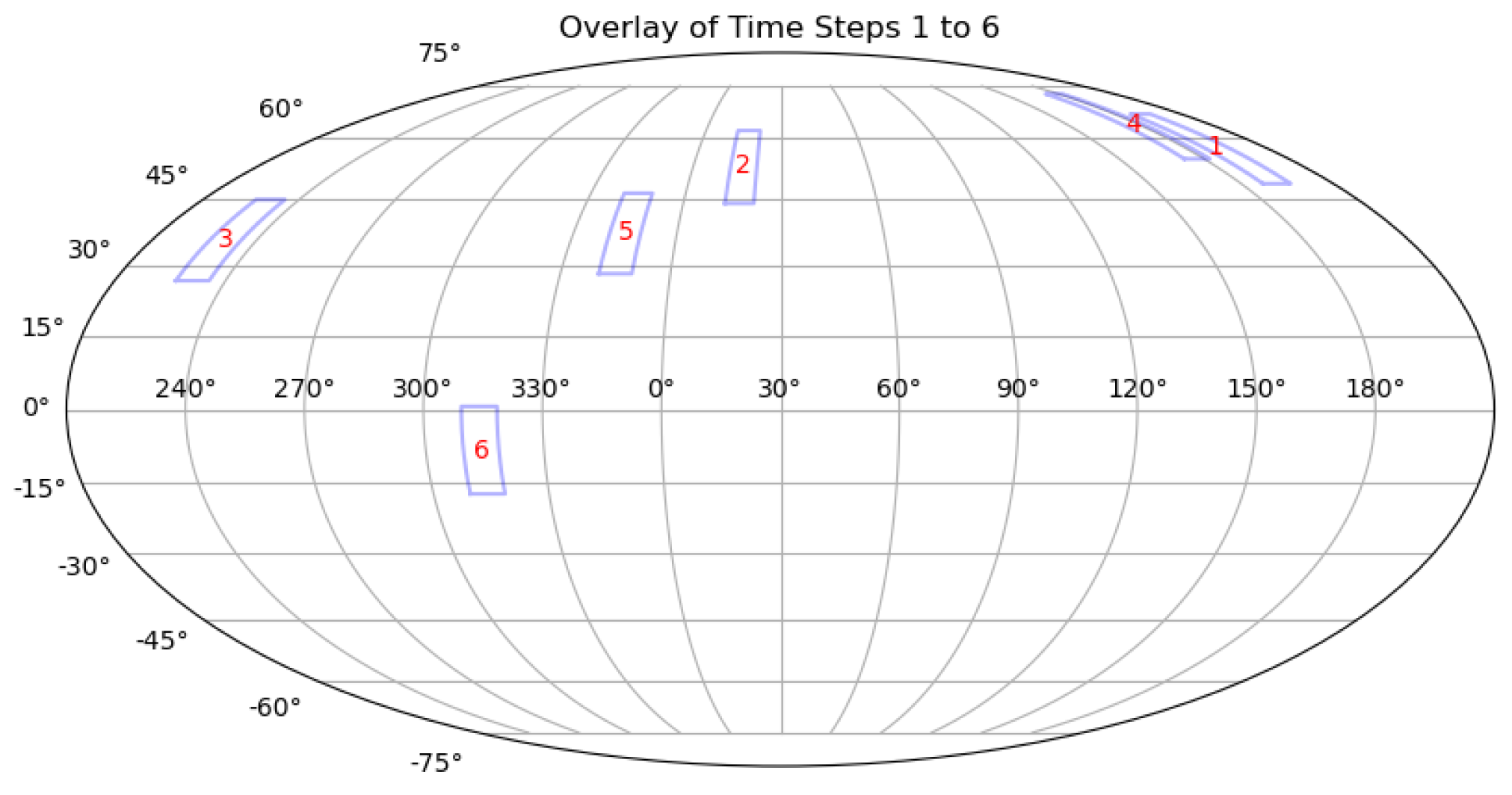

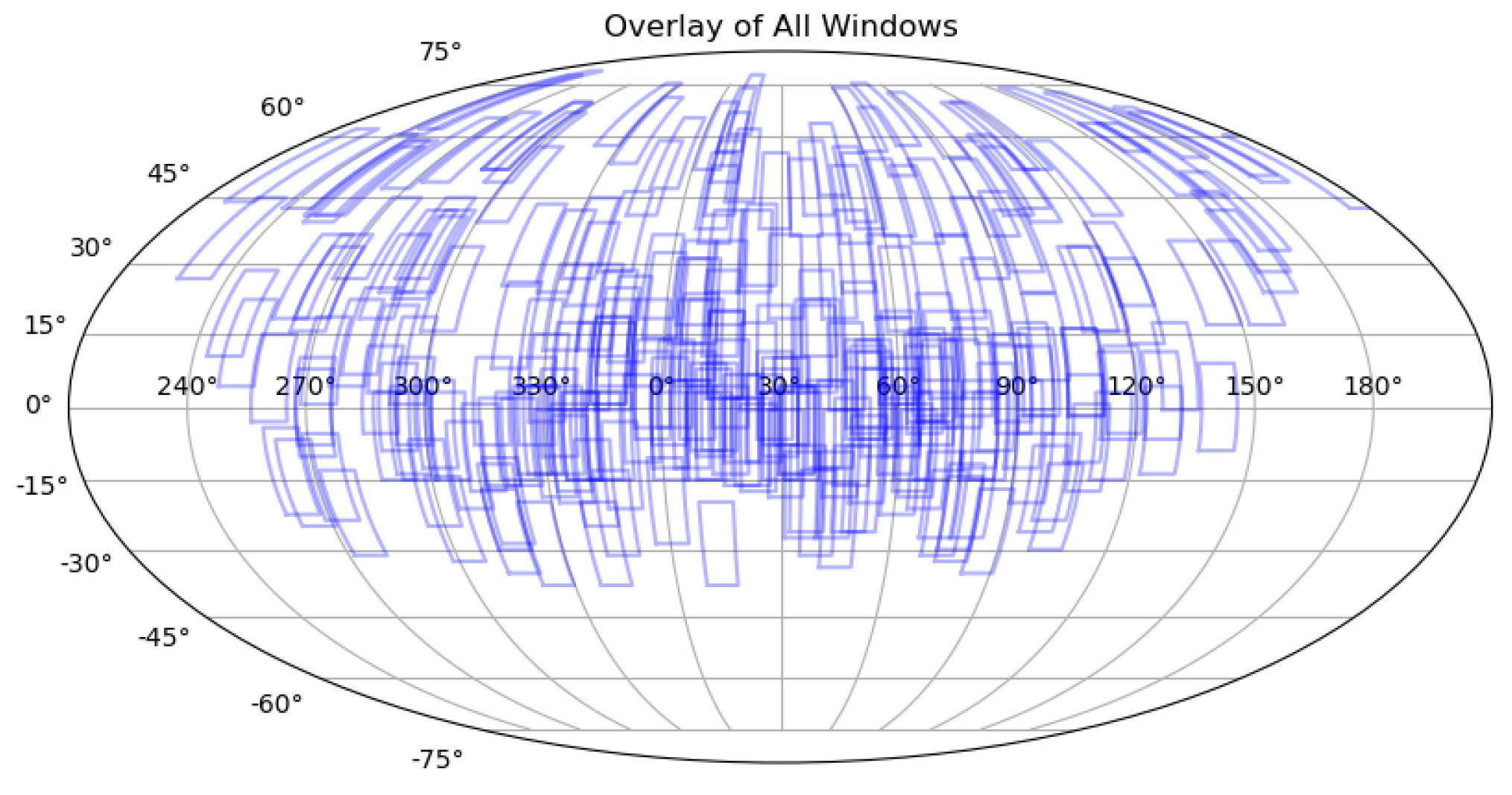

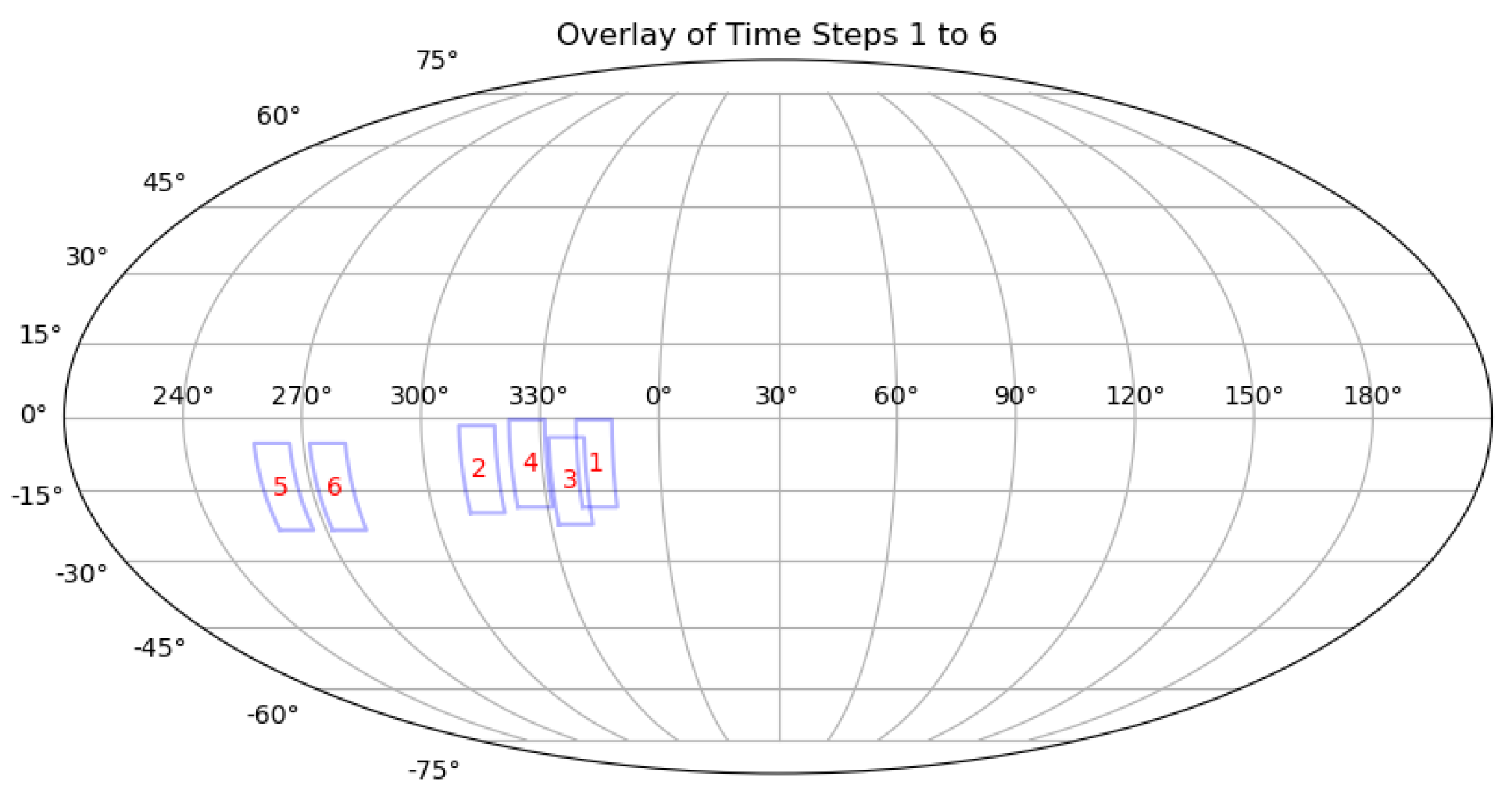

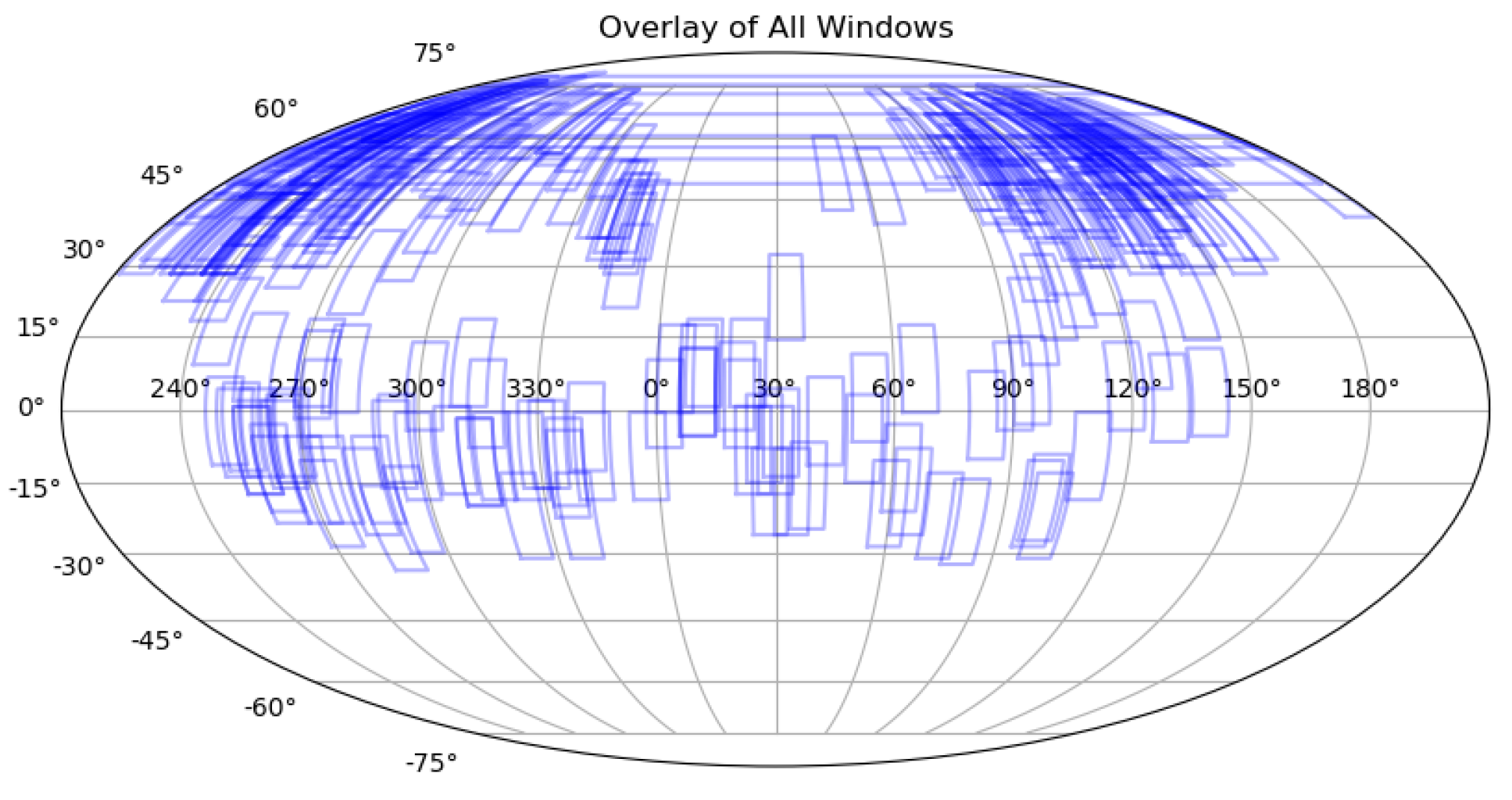

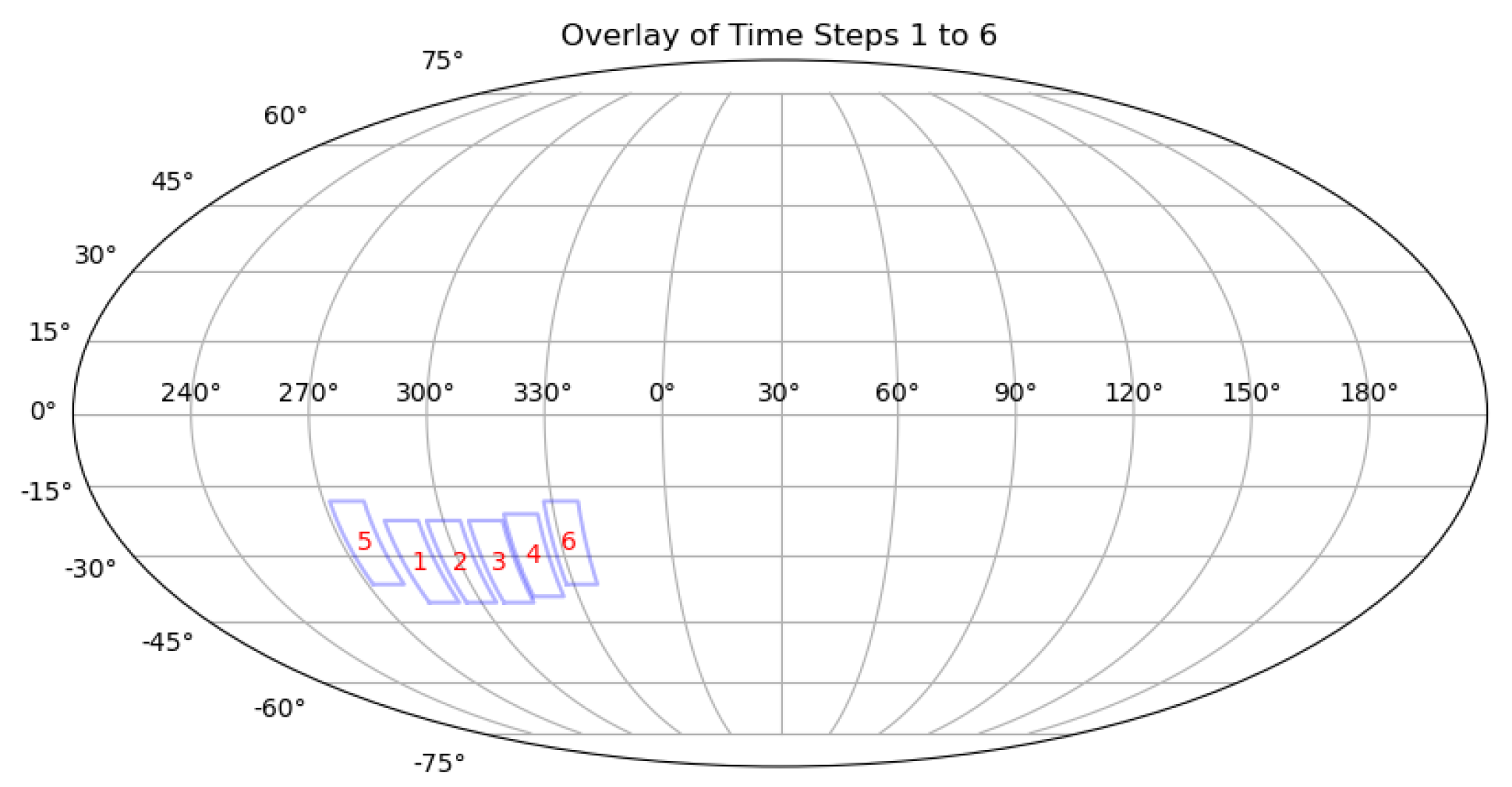

3.2.2. Observation Strategy for Greedy Algorithm

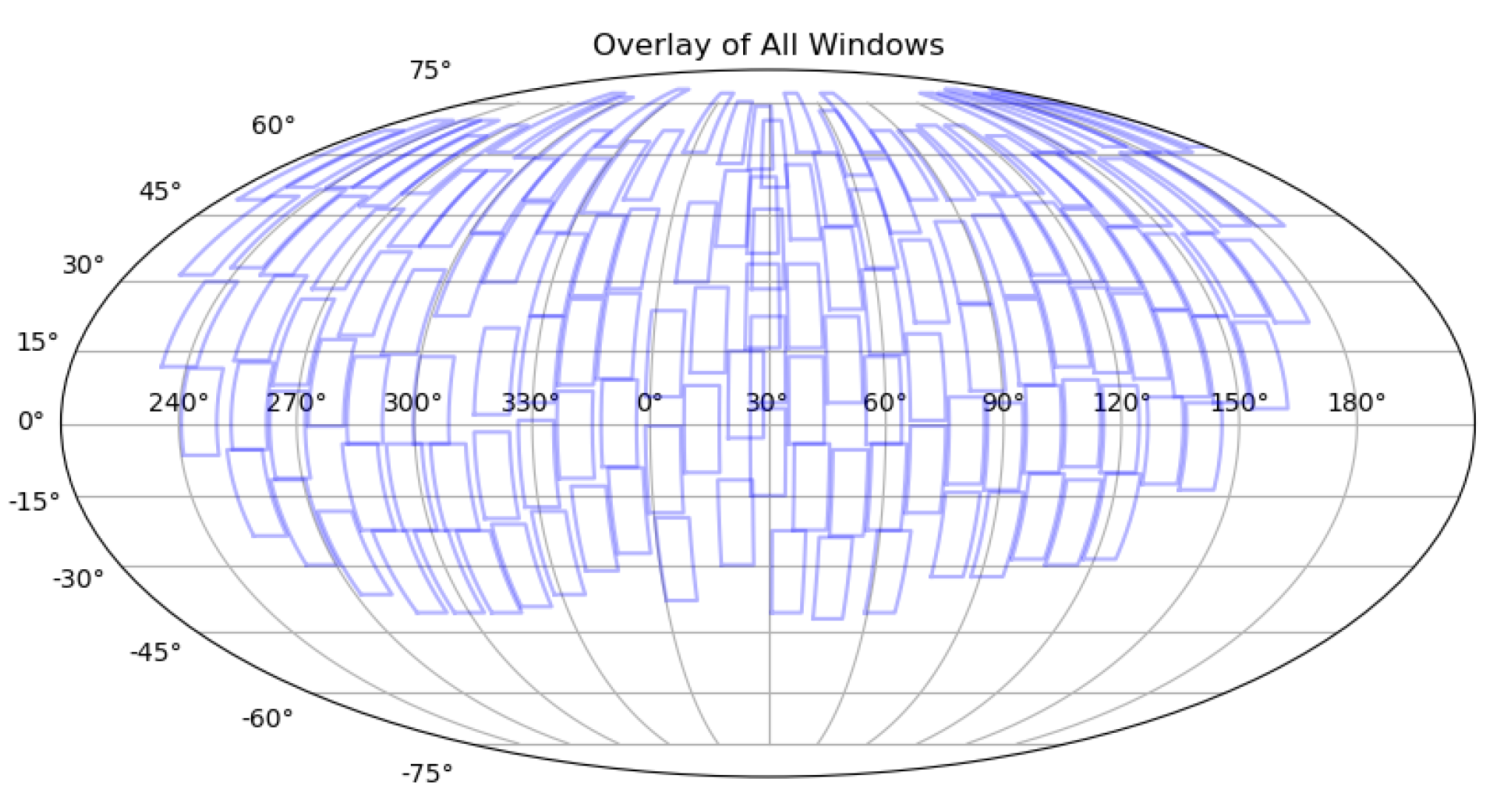

3.2.3. Observation Strategy for All-Sky Coverage

3.3. Result

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Solar, M.; Michelon, P.; Avarias, J.; Garcés, M. A scheduling model for astronomy. Astronomy and Computing 2016, 15, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonry, J.; Denneau, L.; Heinze, A.; Stalder, B.; Smith, K.; Smartt, S.; Stubbs, C.; Weiland, H.; Rest, A. ATLAS: a high-cadence all-sky survey system. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 2018, 130, 064505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, B.M.; Tollerud, E.; Sipocz, B.; Deil, C.; Douglas, S.T.; Medina, J.B.; Vyhmeister, K.; Smith, T.R.; Littlefair, S.; Price-Whelan, A.M.; others. Astroplan: an open source observation planning package in Python. The Astronomical Journal 2018, 155, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimwell, T.; Hardcastle, M.; Tasse, C.; Best, P.; Röttgering, H.; Williams, W.; Botteon, A.; Drabent, A.; Mechev, A.; Shulevski, A.; others. The LOFAR two-metre sky survey-V. Second data release. Astronomy & astrophysics 2022, 659, A1. [Google Scholar]

- Lacy, M.; Baum, S.; Chandler, C.; Chatterjee, S.; Clarke, T.; Deustua, S.; English, J.; Farnes, J.; Gaensler, B.; Gugliucci, N.; others. The Karl G. Jansky very large array sky survey (VLASS). Science case and survey design. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 2020, 132, 035001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellm, E.C.; Kulkarni, S.R.; Graham, M.J.; Dekany, R.; Smith, R.M.; Riddle, R.; Masci, F.J.; Helou, G.; Prince, T.A.; Adams, S.M.; et al. The Zwicky Transient Facility: System Overview, Performance, and First Results. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 2018, 131, 018002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampoudi, S.; Saunders, E.; Eastman, J. An Integer Linear Programming Solution to the Telescope Network Scheduling Problem. arXiv e-prints, arXiv:1503.07170.

- Željko Ivezić; Kahn, S.M.; Tyson, J.A.; Abel, B.; Acosta, E.; Allsman, R.; Alonso, D.; AlSayyad, Y.; Anderson, S.F.; Andrew, J.; et al. LSST: From Science Drivers to Reference Design and Anticipated Data Products. The Astrophysical Journal 2019, 873, 111.

- Naghib, E.; Yoachim, P.; Vanderbei, R.J.; Connolly, A.J.; Jones, R.L. A Framework for Telescope Schedulers: With Applications to the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope. The Astronomical Journal 2018, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Liu, G.; Cai, Z.; Geng, J.; Fang, M.; He, H.; Jiang, J.a.; Jiang, N.; Kong, X.; Li, B.; others. Science with the 2.5-meter wide field survey telescope (wfst). Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy 2023, 66, 109512. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, M.; Adorf, H.M. Scheduling with neural networks—the case of the hubble space telescope. Computers & Operations Research 1992, 19, 209–240. [Google Scholar]

- Kubanek, P. Genetic algorithm for robotic telescope scheduling. arXiv e-prints, arXiv:1002.0108.

- Jia, Q.; Jia, P.; Liu, J. Optimal control of wide field small aperture telescope arrays with reinforcement learning. Observatory Operations: Strategies, Processes, and Systems IX. SPIE, 2022, Vol. 12186, pp. 205–212.

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, C.; Sun, C.; Shang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Zhi, H.; Yang, J.; Tang, S. A multilevel scheduling framework for distributed time-domain large-area sky survey telescope array. The Astronomical Journal 2023, 165, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, A.; Farnocchia, D.; Dimare, L.; Rossi, A.; Bernardi, F. Innovative observing strategy and orbit determination for Low Earth Orbit space debris. Planetary and Space Science 2012, 62, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.; Hussein, I.; Gerber, J.; Sivilli, R. Optimal SSN tasking to enhance real-time space situational awareness. Proceedings of the AMOS Technical Conference, 2016, pp. 20–23.

- Hinze, A.; Fiedler, H.; Schildknecht, T. Optimal scheduling for geosynchronous space object follow-up observations using a genetic algorithm. Advanced Maui Optical and Space Surveillance Technologies Conference (AMOS). Maui Economic Development Board Maui, HW, 2016.

- Frueh, C.; Fielder, H.; Herzog, J. Heuristic and optimized sensor tasking observation strategies with exemplification for geosynchronous objects. Journal of Guidance, Control, and Dynamics 2018, 41, 1036–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Yang, Y.; Gehly, S.; He, C.; Jah, M. Sensor tasking for search and catalog maintenance of geosynchronous space objects. Acta Astronautica 2020, 175, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Jia, Q.; Jiang, T.; Liu, J. Observation strategy optimization for distributed telescope arrays with deep reinforcement learning. The Astronomical Journal 2023, 165, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorski, K.M.; Hivon, E.; Banday, A.J.; Wandelt, B.D.; Hansen, F.K.; Reinecke, M.; Bartelmann, M. HEALPix: A framework for high-resolution discretization and fast analysis of data distributed on the sphere. The Astrophysical Journal 2005, 622, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zonca, A.; Singer, L.; Lenz, D.; Reinecke, M.; Rosset, C.; Hivon, E.; Gorski, K. healpy: equal area pixelization and spherical harmonics transforms for data on the sphere in Python. Journal of Open Source Software 2019, 4, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Hu, S.; Du, J.; Yang, X.; Chen, X.; Jiang, H.; Cao, H.; Feng, S. Detecting Moving Objects in Photometric Images Using 3D Hough Transform. PUBLICATIONS OF THE ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY OF THE PACIFIC 2024, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | |

| 2 |

| Telescope Survey Strategy | Observation Strategy for Greedy Algorithm(Arc Segments) | Randomized Observation Strategy(Arc Segments) | Observation Strategy for Greedy Algorithm(Space Debris) | Randomized Observation Strategy(Space Debris) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation results | 4579 | 3611 | 3080 | 1505 |

| Observation results | 3455 | 2674 | 331 | 175 |

| Telescope Survey Strategy | Observation Strategy for Greedy Algorithm(Arc Segments) | Observation Strategy for All-Sky Coverage(Arc Segments) | Observation Strategy for Greedy Algorithm(Space Debris) | Observation Strategy for All-Sky Coverage(Space Debris) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation results | 4087 | 1125 | 3166 | 904 |

| Observation results | 3058 | 855 | 346 | 94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).